cat's whisker detector on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A crystal detector is an obsolete

A crystal detector is an obsolete

part1part2part3part4

/ref> who discovered crystal rectification in 1902 and found hundreds of crystalline substances that could be used in forming rectifying junctions. The physical principles by which they worked were not understood at the time they were used, but subsequent research into these primitive point contact semiconductor junctions in the 1930s and 1940s led to the development of modern

During the first three decades of radio, from 1888 to 1918, called the ''

During the first three decades of radio, from 1888 to 1918, called the ''

IndianDefense

Sarkar, Tapan K.; Sengupta, Dipak L. "An appreciation of J. C. Bose's pioneering work in millimeter and microwaves" in Like other scientists since Hertz, Bose was investigating the similarity between radio waves and light by duplicating classic

/ref> For a receiver he first used a

Wellenempfindliche Kontaktstel

', filed: 18 February 1906, granted: 22 October 1906 In 1906 L. W. Austin invented a silicon–

/ref> He realized that amplifying crystals could be an alternative to the fragile, expensive, energy-wasting vacuum tube. He used biased negative resistance crystal junctions to build solid-state

"The Crystodyne Principle"

''Radio News'', September 1924, pages 294-295, 431. Later he even built a

/ref> In 1930 Bernhard Gudden and Wilson established that electrical conduction in semiconductors was due to trace impurities in the crystal. A "pure" semiconductor did not act as a semiconductor, but as an insulator (at low temperatures). The maddeningly variable activity of different pieces of crystal when used in a detector, and the presence of "active sites" on the surface, was due to natural variations in the concentration of these impurities throughout the crystal. Nobel Laureate

The development of

The development of

Crystal and Solid Contact Rectifiers

1909 publication describes experiments to determine the means of rectification (

Radio Detector Development

from 1917 '' The Electrical Experimenter''

The Crystal Experimenters Handbook

1922 London publication devoted to point-contact diode detectors (PDF file courtesy of Lorne Clark via earlywireless.com) * ;Patents * - ''Oscillation detector'' (multiple metallic sulfide detectors), Clifford D. Babcock, 1908 * - ''Oscillation detector and rectifier'' ("plated" silicon carbide detector with DC bias), G.W. Pickard, 1909 * - ''Oscillation receiver'' (fractured surface red zinc oxide (zincite) detector), G.W. Pickard, 1909 * - ''Oscillation device'' (iron pyrite detector), G.W. Pickard, 1909 * - ''Oscillation detectors'' (paired dissimilar minerals), G.W. Pickard, 1914 {{Authority control History of radio technology Radio electronics Diodes Detectors

A crystal detector is an obsolete

A crystal detector is an obsolete electronic component

An electronic component is any basic discrete electronic device or physical entity part of an electronic system used to affect electrons or their associated fields. Electronic components are mostly industrial products, available in a singula ...

used in some early 20th century radio receiver

In radio communications, a radio receiver, also known as a receiver, a wireless, or simply a radio, is an electronic device that receives radio waves and converts the information carried by them to a usable form. It is used with an antenna. ...

s. It consists of a piece of crystalline mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

that rectifies an alternating current

Alternating current (AC) is an electric current that periodically reverses direction and changes its magnitude continuously with time, in contrast to direct current (DC), which flows only in one direction. Alternating current is the form in w ...

radio signal. It was employed as a detector (demodulator

Demodulation is the process of extracting the original information-bearing signal from a carrier wave. A demodulator is an electronic circuit (or computer program in a software-defined radio) that is used to recover the information content from ...

) to extract the audio modulation signal from the modulated carrier, to produce the sound in the earphones. It was the first type of semiconductor diode, and one of the first semiconductor electronic devices. The most common type was the so-called cat's whisker detector, which consisted of a piece of crystalline mineral, usually galena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crysta ...

( lead sulfide), with a fine wire touching its surface. Greenleaf Whittier Pickard, ''Detector for Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony'', filed: 21 June 1911, granted: 21 July 1914

The "asymmetric conduction" of electric current across electrical contacts between a crystal and a metal was discovered in 1874 by Karl Ferdinand Braun. Crystals were first used as radio wave detectors in 1894 by Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose (; ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a polymath with interests in biology, physics and writing science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contributions ...

in his microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths shorter than other radio waves but longer than infrared waves. Its wavelength ranges from about one meter to one millimeter, corresponding to frequency, frequencies between 300&n ...

experiments. Bose first patented a crystal detector in 1901. Jagadis Chunder Bose, ''Detector for Electrical Disturbances'', filed: 30 September 1901, granted 29 March 1904 The crystal detector was developed into a practical radio component mainly by G. W. Pickard, Greenleaf Whittier Pickard, ''Means for Receiving Intelligence Communicated by Electric Waves'', filed: 30 August 1906, granted: 20 November 1906 archivedpart1

/ref> who discovered crystal rectification in 1902 and found hundreds of crystalline substances that could be used in forming rectifying junctions. The physical principles by which they worked were not understood at the time they were used, but subsequent research into these primitive point contact semiconductor junctions in the 1930s and 1940s led to the development of modern

semiconductor electronics

A semiconductor device is an electronic component that relies on the electronic properties of a semiconductor material (primarily silicon, germanium, and gallium arsenide, as well as organic semiconductors) for its function. Its conductivity l ...

.

The unamplified radio receivers that used crystal detectors are called crystal radios. The crystal radio was the first type of radio receiver that was used by the general public, and became the most widely used type of radio until the 1920s."...crystal detectors have been used n receiversin greater numbers than any other ype of detectorsince about 1907." It became obsolete with the development of vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, thermionic valve (British usage), or tube (North America) is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied. It ...

receivers around 1920, but continued to be used until World War II and remains a common educational project today thanks to its simple design.

Operation

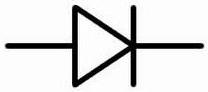

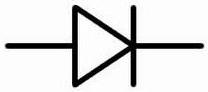

The contact between two dissimilar materials at the surface of the detector's semiconducting crystal forms a crude semiconductor diode, which acts as arectifier

A rectifier is an electrical device that converts alternating current (AC), which periodically reverses direction, to direct current (DC), which flows in only one direction.

The process is known as ''rectification'', since it "straightens" t ...

, conducting electric current

An electric current is a flow of charged particles, such as electrons or ions, moving through an electrical conductor or space. It is defined as the net rate of flow of electric charge through a surface. The moving particles are called charge c ...

well in only one direction and resisting current flowing in the other direction. In a crystal radio, it was connected between the tuned circuit

An LC circuit, also called a resonant circuit, tank circuit, or tuned circuit, is an electric circuit consisting of an inductor, represented by the letter L, and a capacitor, represented by the letter C, connected together. The circuit can act ...

, which passed on the oscillating current induced in the antenna from the desired radio station, and the earphone. Its function was to act as a demodulator

Demodulation is the process of extracting the original information-bearing signal from a carrier wave. A demodulator is an electronic circuit (or computer program in a software-defined radio) that is used to recover the information content from ...

, rectifying the radio signal, converting it from alternating current

Alternating current (AC) is an electric current that periodically reverses direction and changes its magnitude continuously with time, in contrast to direct current (DC), which flows only in one direction. Alternating current is the form in w ...

to a pulsing direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional electric current, flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor (material), conductor such as a wire, but can also flow throug ...

, to extract the audio signal

An audio signal is a representation of sound, typically using either a changing level of electrical voltage for analog signals or a series of binary numbers for Digital signal (signal processing), digital signals. Audio signals have frequencies i ...

(modulation

Signal modulation is the process of varying one or more properties of a periodic waveform in electronics and telecommunication for the purpose of transmitting information.

The process encodes information in form of the modulation or message ...

) from the radio frequency

Radio frequency (RF) is the oscillation rate of an alternating electric current or voltage or of a magnetic, electric or electromagnetic field or mechanical system in the frequency range from around to around . This is roughly between the u ...

carrier wave

In telecommunications, a carrier wave, carrier signal, or just carrier, is a periodic waveform (usually sinusoidal) that conveys information through a process called ''modulation''. One or more of the wave's properties, such as amplitude or freq ...

. An AM demodulator which works in this way, by rectifying the modulated carrier, is called an envelope detector. The audio frequency

An audio frequency or audible frequency (AF) is a periodic vibration whose frequency is audible to the average human. The SI unit of frequency is the hertz (Hz). It is the property of sound that most determines pitch.

The generally accepted ...

current produced by the detector passed through the earphone

Headphones are a pair of small loudspeaker drivers worn on or around the head over a user's ears. They are electroacoustic transducers, which convert an electrical signal to a corresponding sound. Headphones let a single user listen to an a ...

causing the earphone's diaphragm to vibrate, pushing on the air to create sound wave

In physics, sound is a vibration that propagates as an acoustic wave through a transmission medium such as a gas, liquid or solid.

In human physiology and psychology, sound is the ''reception'' of such waves and their ''perception'' by the ...

s.

Crystal radios had no amplifying components to increase the loudness of the radio signal; the sound power produced by the earphone came solely from the radio waves of the radio station being received, intercepted by the antenna. Therefore, the sensitivity of the detector was a major factor determining the sensitivity and reception range of the receiver, motivating much research into finding sensitive detectors.

In addition to its main use in crystal radios, crystal detectors were also used as radio wave detectors in scientific experiments, in which the DC output current of the detector was registered by a sensitive galvanometer

A galvanometer is an electromechanical measuring instrument for electric current. Early galvanometers were uncalibrated, but improved versions, called ammeters, were calibrated and could measure the flow of current more precisely. Galvanomet ...

, and in test instruments such as wavemeter

An absorption wavemeter is a simple electronic instrument used to measure the frequency of radio waves. It is an older method of measuring frequency, widely used from the birth of radio in the early 20th century until the 1970s, when the develop ...

s used to calibrate the frequency of radio transmitter

In electronics and telecommunications, a radio transmitter or just transmitter (often abbreviated as XMTR or TX in technical documents) is an electronic device which produces radio waves with an antenna with the purpose of signal transmissio ...

s.

As shown in the diagram on the right, ' shows an amplitude modulated radio signal from the receiver's tuned circuit, which is applied as a voltage across the detector's contacts. The rapid oscillations are the radio frequency

Radio frequency (RF) is the oscillation rate of an alternating electric current or voltage or of a magnetic, electric or electromagnetic field or mechanical system in the frequency range from around to around . This is roughly between the u ...

carrier wave

In telecommunications, a carrier wave, carrier signal, or just carrier, is a periodic waveform (usually sinusoidal) that conveys information through a process called ''modulation''. One or more of the wave's properties, such as amplitude or freq ...

. The audio signal

An audio signal is a representation of sound, typically using either a changing level of electrical voltage for analog signals or a series of binary numbers for Digital signal (signal processing), digital signals. Audio signals have frequencies i ...

(the sound) is contained in the slow variations (modulation

Signal modulation is the process of varying one or more properties of a periodic waveform in electronics and telecommunication for the purpose of transmitting information.

The process encodes information in form of the modulation or message ...

) of the size of the waves. If this signal were applied directly to the earphone, it could not be converted to sound, because the audio excursions are the same on both sides of the axis, averaging out to zero, which would result in no net motion of the earphone's diaphragm. ' shows the current through the crystal detector which is applied to the earphone and bypass capacitor. The crystal conducts current in only one direction, stripping off the oscillations on one side of the signal, leaving a pulsing direct current whose amplitude does not average zero but varies with the audio signal. ' shows the current which passes through the earphone. A bypass capacitor

In electrical engineering, a capacitor is a device that stores electrical energy by accumulating electric charges on two closely spaced surfaces that are insulated from each other. The capacitor was originally known as the condenser, a term st ...

across the earphone terminals, in combination with the intrinsic forward resistance of the diode, creates a low-pass filter

A low-pass filter is a filter that passes signals with a frequency lower than a selected cutoff frequency and attenuates signals with frequencies higher than the cutoff frequency. The exact frequency response of the filter depends on the filt ...

that smooths the waveform by removing the radio frequency carrier pulses and leaving the audio signal. When this varying current passes through the earphone piezoelectric crystal, it causes the crystal to deform (flex), deflecting the earphone diaphragm; the varying deflections of the diaphragm cause it to vibrate and produce sound waves ( acoustic waves). If instead a voice-coil type headphone is used, the varying current from the low-pass filter flows through the voice coil, generating a varying magnetic field which pulls and pushes the earphone diaphragm, causing it to vibrate and produce sound.

Types

The crystal detector consisted of an electrical contact between the surface of a semiconductingcrystalline

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macrosc ...

mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

and either a metal or another crystal. Since at the time they were developed no one knew how they worked, crystal detectors evolved by trial and error. The construction of the detector depended on the type of crystal used, as it was found different minerals varied in how much contact area and pressure on the crystal surface was needed to make a sensitive rectifying contact. Crystals that required a light pressure like galena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crysta ...

were used with the wire cat whisker contact; silicon

Silicon is a chemical element; it has symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic lustre, and is a tetravalent metalloid (sometimes considered a non-metal) and semiconductor. It is a membe ...

was used with a heavier point contact, while silicon carbide

Silicon carbide (SiC), also known as carborundum (), is a hard chemical compound containing silicon and carbon. A wide bandgap semiconductor, it occurs in nature as the extremely rare mineral moissanite, but has been mass-produced as a powder a ...

(carborundum

Silicon carbide (SiC), also known as carborundum (), is a hard chemical compound containing silicon and carbon. A wide bandgap semiconductor, it occurs in nature as the extremely rare mineral moissanite, but has been mass-produced as a powder ...

) could tolerate the heaviest pressure. Another type used two crystals of different minerals with their surfaces touching, the most common being the "Perikon" detector. Since the detector would only function when the contact was made at certain spots on the crystal surface, the contact point was almost always made adjustable. Below are the major categories of crystal detectors used during the early 20th century:

Cat whisker detector

Patented by Karl Ferdinand Braun and Greenleaf Whittier Pickard in 1906, this was the most common type of crystal detector, mainly used withgalena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crysta ...

but also other crystals. It consisted of a pea-size piece of crystalline mineral in a metal holder, with its surface touched by a fine metal wire or needle (the "cat whisker"). The contact between the tip of the wire and the surface of the crystal formed a crude unstable point-contact metal–semiconductor junction, forming a Schottky barrier diode."''The cat’s-whisker detector is a primitive point-contact diode. A point-contact junction is the simplest implementation of a Schottky diode, which is a majority-carrier device formed by a metal-semiconductor junction.''" The wire whisker is the anode

An anode usually is an electrode of a polarized electrical device through which conventional current enters the device. This contrasts with a cathode, which is usually an electrode of the device through which conventional current leaves the devic ...

, and the crystal is the cathode

A cathode is the electrode from which a conventional current leaves a polarized electrical device such as a lead-acid battery. This definition can be recalled by using the mnemonic ''CCD'' for ''Cathode Current Departs''. Conventional curren ...

; current can flow from the wire into the crystal but not in the other direction.

Only certain sites on the crystal surface functioned as rectifying junctions. The device was very sensitive to the exact geometry and pressure of contact between wire and crystal, and the contact could be disrupted by the slightest vibration. Therefore, a usable point of contact had to be found by trial and error before each use. The wire was suspended from a moveable arm and was dragged across the crystal face by the user until the device began functioning. In a crystal radio, the user would tune the radio to a strong local station if possible and then adjust the cat whisker until the station or radio noise

In radio reception, radio noise (commonly referred to as radio static) is unwanted random radio frequency electrical signals, fluctuating voltages, always present in a radio receiver in addition to the desired radio signal.

Radio noise is a comb ...

(a static hissing noise) was heard in the radio's earphones. This required some skill and a lot of patience. An alternative method of adjustment was to use a battery-operated electromechanical buzzer

A buzzer or beeper is an audio signaling device, which may be mechanical, electromechanical, or piezoelectric (''piezo'' for short). Typical uses of buzzers and beepers include alarm devices, timers, train and confirmation of user input such ...

connected to the radio's ground wire or inductively coupled to the tuning coil, to generate a test signal. The spark produced by the buzzer's contacts functioned as a weak radio transmitter

In electronics and telecommunications, a radio transmitter or just transmitter (often abbreviated as XMTR or TX in technical documents) is an electronic device which produces radio waves with an antenna with the purpose of signal transmissio ...

whose radio waves could be received by the detector, so when a rectifying spot had been found on the crystal the buzz could be heard in the earphones, at which time the buzzer was turned off.

The detector consisted of two parts mounted next to each other on a flat nonconductive base: a crystalline

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macrosc ...

mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

forming the semiconductor side of the junction, and a "cat whisker", a springy piece of thin metal wire, forming the metal side of the junction

Crystal

The most common crystal used wasgalena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crysta ...

( lead sulfide, PbS), a widely occurring ore of lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

. Varieties were sold under the names "Lenzite" and "Hertzite". Other crystalline minerals were also used, the more common ones being iron pyrite

The mineral pyrite ( ), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue ...

(iron sulfide, FeS2, "fool's gold", also sold under the trade names "Pyron", "Ferron", and "Radiocite") molybdenite

Molybdenite is a mineral of molybdenum disulfide, Mo S2. Similar in appearance and feel to graphite, molybdenite has a lubricating effect that is a consequence of its layered structure. The atomic structure consists of a sheet of molybdenum at ...

(molybdenum disulfide

Molybdenum disulfide (or moly) is an inorganic chemistry, inorganic compound composed of molybdenum and sulfur. Its chemical formula is .

The compound is classified as a transition metal dichalcogenide. It is a silvery black solid that occurs as ...

, MoS2), and cerussite

Cerussite (also known as lead carbonate or white lead ore) is a mineral consisting of lead carbonate with the chemical formula PbCO3, and is an important ore of lead. The name is from the Latin ''cerussa'', white lead. ''Cerussa nativa'' was ...

(lead carbonate

Lead(II) carbonate is the chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a white, toxic solid. It occurs naturally as the mineral cerussite.

Structure

Like all metal carbonates, lead(II) carbonate adopts a dense, highly crosslinked structure ...

, PbCO3) Not all specimens of a crystal would function in a detector. Often several crystal pieces had to be tried to find an active one. Galena with good detecting properties was rare and had no reliable visual characteristics distinguishing it.

A rough pebble of detecting mineral about the size of a pea was mounted in a metal cup, which formed one side of the circuit. The electrical contact between the cup and the crystal had to be good, because it was important for this contact ''not'' to act as a second rectifying junction, creating two back-to-back diodes which would prevent the device from conducting at all. To make good contact with the crystal, it was either clamped with setscrews or embedded in solder

Solder (; North American English, NA: ) is a fusible alloy, fusible metal alloy used to create a permanent bond between metal workpieces. Solder is melted in order to wet the parts of the joint, where it adheres to and connects the pieces aft ...

. Because the relatively high melting temperature of tin-lead solder

Solder (; North American English, NA: ) is a fusible alloy, fusible metal alloy used to create a permanent bond between metal workpieces. Solder is melted in order to wet the parts of the joint, where it adheres to and connects the pieces aft ...

could damage many crystals, a fusible alloy

A fusible alloy is a metal alloy capable of being easily fused, i.e. easily meltable, at relatively low temperatures. Fusible alloys are commonly, but not necessarily, eutectic alloys.

Sometimes the term "fusible alloy" is used to describe alloy ...

with a low melting point, well under , such as Wood's metal was used. One surface was left exposed to allow contact with the cat-whisker wire.

Cat whisker wire

Phosphor bronze

A phosphor is a substance that exhibits the optical phenomenon, phenomenon of luminescence; it emits light when exposed to some type of radiant energy. The term is used both for fluorescence, fluorescent or phosphorescence, phosphorescent sub ...

wire of about 30 AWG (0.25 mm) diameter was commonly used as a cat whisker because it had the right amount of springiness. It was mounted on an adjustable arm with an insulated handle so that the entire exposed surface of the crystal could be probed from many directions to find the most sensitive spot. Cat whiskers in homemade detectors usually had a simple curved shape, but most professional cat whiskers had a coiled section in the middle that served as a spring. The crystal required just the right gentle pressure by the wire; too much pressure caused the device to conduct in both directions. Precision detectors made for radiotelegraphy stations often used a metal needle instead of a "cat's whisker", mounted on a thumbscrew-operated leaf spring to adjust the pressure applied. Gold or silver needles were used with some crystals.

Carborundum detector

Invented in 1906 by Henry H. C. Dunwoody, Henry H. C. Dunwoody, ''Wireless Telegraph System'', filed: 23 March 1906, granted: 4 December 1906 this consisted of a piece ofsilicon carbide

Silicon carbide (SiC), also known as carborundum (), is a hard chemical compound containing silicon and carbon. A wide bandgap semiconductor, it occurs in nature as the extremely rare mineral moissanite, but has been mass-produced as a powder a ...

(SiC, then known by the trade name ''carborundum''), either clamped between two flat metal contacts, or mounted in fusible alloy

A fusible alloy is a metal alloy capable of being easily fused, i.e. easily meltable, at relatively low temperatures. Fusible alloys are commonly, but not necessarily, eutectic alloys.

Sometimes the term "fusible alloy" is used to describe alloy ...

in a metal cup with a contact consisting of a hardened steel point pressed firmly against it with a spring. Carborundum, an artificial product of electric furnaces produced in 1893, required a heavier pressure than the cat whisker contact. The carborundum detector was popular because its sturdy contact did not require readjustment each time it was used, like the delicate cat whisker devices. Some carborundum detectors were adjusted at the factory and then sealed and did not require adjustment by the user. It was not sensitive to vibration and so was used in shipboard wireless stations where the ship was rocked by waves, and military stations where vibration from gunfire could be expected. Another advantage was that it was tolerant of high currents, and could not be "burned out" by atmospheric electricity from the antenna. Therefore, it was the most common type used in commercial radiotelegraphy stations.

Silicon carbide is a semiconductor with a wide band gap

In solid-state physics and solid-state chemistry, a band gap, also called a bandgap or energy gap, is an energy range in a solid where no electronic states exist. In graphs of the electronic band structure of solids, the band gap refers to t ...

of 3 eV, so to make the detector more sensitive a forward bias

Bias is a disproportionate weight ''in favor of'' or ''against'' an idea or thing, usually in a way that is inaccurate, closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair. Biases can be innate or learned. People may develop biases for or against an individ ...

voltage of several volts was usually applied across the junction by a battery and potentiometer

A potentiometer is a three- terminal resistor with a sliding or rotating contact that forms an adjustable voltage divider. If only two terminals are used, one end and the wiper, it acts as a variable resistor or rheostat.

The measuring instrum ...

. The voltage was adjusted with the potentiometer until the sound was loudest in the earphone. The bias moved the operating point

The operating point is a specific point within the operation Receiver operating characteristic, characteristic of a technical device. This point will be engaged because of the properties of the system and the outside influences and parameters. In ...

to the curved "knee" of the device's current–voltage curve, which produced the largest rectified current.

Silicon detector

Patented and first manufactured in 1906 by Pickard, this was the first type of crystal detector to be commercially produced. Silicon required more pressure than the cat whisker contact, although not as much as carborundum. A flat piece ofsilicon

Silicon is a chemical element; it has symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic lustre, and is a tetravalent metalloid (sometimes considered a non-metal) and semiconductor. It is a membe ...

was embedded in fusible alloy

A fusible alloy is a metal alloy capable of being easily fused, i.e. easily meltable, at relatively low temperatures. Fusible alloys are commonly, but not necessarily, eutectic alloys.

Sometimes the term "fusible alloy" is used to describe alloy ...

in a metal cup, and a metal point, usually brass

Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, in proportions which can be varied to achieve different colours and mechanical, electrical, acoustic and chemical properties, but copper typically has the larger proportion, generally copper and zinc. I ...

or gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

, was pressed against it with a spring. The surface of the silicon was usually ground flat and polished. Silicon was also used with antimony

Antimony is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Sb () and atomic number 51. A lustrous grey metal or metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient t ...

and arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol As and atomic number 33. It is a metalloid and one of the pnictogens, and therefore shares many properties with its group 15 neighbors phosphorus and antimony. Arsenic is not ...

contacts. The silicon detector was popular because it had much the same advantages as carborundum; its firm contact could not be jarred loose by vibration and it did not require a bias battery, so it saw wide use in commercial and military radiotelegraphy stations.

Crystal-to-crystal detectors

Another category was detectors which used two different crystals with their surfaces touching, forming a crystal-to-crystal contact. The "Perikon" detector, invented 1908 by Pickard Greenleaf Whittier Pickard, ''Oscillation receiver'', filed: 15 September 1908, granted: 16 February 1909 was the most common. ''Perikon'' stood for "PERfect pIcKard cONtact". It consisted of two crystals in metal holders, mounted face to face. One crystal was zincite (zinc oxide

Zinc oxide is an inorganic compound with the Chemical formula, formula . It is a white powder which is insoluble in water. ZnO is used as an additive in numerous materials and products including cosmetics, Zinc metabolism, food supplements, rubbe ...

, ZnO), the other was a copper iron sulfide, either bornite (Cu5FeS4) or chalcopyrite

Chalcopyrite ( ) is a copper iron sulfide mineral and the most abundant copper ore mineral. It has the chemical formula CuFeS2 and crystallizes in the tetragonal system. It has a brassy to golden yellow color and a Mohs scale, hardness of 3.5 to 4 ...

(CuFeS2). In Pickard's commercial detector ''(see picture)'', multiple zincite crystals were mounted in a fusible alloy in a round cup ''(on right)'', while the chalcopyrite crystal was mounted in a cup on an adjustable arm facing it ''(on left)''. The chalcopyrite crystal was moved forward until it touched the surface of one of the zincite crystals. When a sensitive spot was located, the arm was locked in place with the setscrew. Multiple zincite pieces were provided because the fragile zincite crystal could be damaged by excessive currents and tended to "burn out" due to atmospheric electricity from the wire antenna or currents leaking into the receiver from the powerful spark transmitters used at the time. This detector was also sometimes used with a small forward bias voltage of around 0.2V from a battery to make it more sensitive.

Although the zincite-chalcopyrite "Perikon" was the most widely used crystal-to-crystal detector, other crystal pairs were also used. Zincite was used with carbon, galena, and tellurium

Tellurium is a chemical element; it has symbol Te and atomic number 52. It is a brittle, mildly toxic, rare, silver-white metalloid. Tellurium is chemically related to selenium and sulfur, all three of which are chalcogens. It is occasionally fou ...

. Silicon was used with arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol As and atomic number 33. It is a metalloid and one of the pnictogens, and therefore shares many properties with its group 15 neighbors phosphorus and antimony. Arsenic is not ...

, antimony

Antimony is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Sb () and atomic number 51. A lustrous grey metal or metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient t ...

and tellurium

Tellurium is a chemical element; it has symbol Te and atomic number 52. It is a brittle, mildly toxic, rare, silver-white metalloid. Tellurium is chemically related to selenium and sulfur, all three of which are chalcogens. It is occasionally fou ...

crystals.

History

During the first three decades of radio, from 1888 to 1918, called the ''

During the first three decades of radio, from 1888 to 1918, called the ''wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is the transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using electrical cable, cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimenta ...

'' or "spark" era, primitive radio transmitter

In electronics and telecommunications, a radio transmitter or just transmitter (often abbreviated as XMTR or TX in technical documents) is an electronic device which produces radio waves with an antenna with the purpose of signal transmissio ...

s called spark gap transmitter

A spark-gap transmitter is an obsolete type of radio transmitter which generates radio waves by means of an electric spark."Radio Transmitters, Early" in Spark-gap transmitters were the first type of radio transmitter, and were the main type use ...

s were used, which generated radio waves by an electric spark

An electric spark is an abrupt electrical discharge that occurs when a sufficiently high electric field creates an Ionization, ionized, Electric current, electrically conductive channel through a normally-insulating medium, often air or other ga ...

. These transmitters were unable to produce the continuous sinusoidal waves which are used to transmit audio

Audio most commonly refers to sound, as it is transmitted in signal form. It may also refer to:

Sound

*Audio signal, an electrical representation of sound

*Audio frequency, a frequency in the audio spectrum

*Digital audio, representation of sound ...

(sound) in modern AM or FM radio transmission.

Instead spark gap transmitters transmitted information by wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is the transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using electrical cable, cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimenta ...

; the user turned the transmitter on and off rapidly by tapping on a telegraph key

A telegraph key, clacker, tapper or morse key is a specialized electrical switch used by a trained operator to transmit text messages in Morse code in a telegraphy system. Keys are used in all forms of electrical telegraph systems, includ ...

, producing pulses of radio waves which spelled out text messages in Morse code

Morse code is a telecommunications method which Character encoding, encodes Written language, text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code i ...

. Therefore, the radio receiver

In radio communications, a radio receiver, also known as a receiver, a wireless, or simply a radio, is an electronic device that receives radio waves and converts the information carried by them to a usable form. It is used with an antenna. ...

s of this era did not have to demodulate the radio wave, extract an audio signal

An audio signal is a representation of sound, typically using either a changing level of electrical voltage for analog signals or a series of binary numbers for Digital signal (signal processing), digital signals. Audio signals have frequencies i ...

from it as modern receivers do, they merely had to detect the presence or absence of the radio waves, to make a sound in the earphone when the radio wave was present to represent the "dots" and "dashes" of Morse code. The device which did this was called a '' detector''. The crystal detector was the most successful of many detector devices invented during this era.

The crystal detector evolved from an earlier device,

the first primitive radio wave detector, called a ''coherer

The coherer was a primitive form of radio signal detector used in the first radio receivers during the wireless telegraphy era at the beginning of the 20th century. Its use in radio was based on the 1890 findings of French physicist Édouard Bra ...

'', developed in 1890 by Édouard Branly

Édouard Eugène Désiré Branly (, ; ; 23 October 1844 – 24 March 1940) was a French physicist and inventor known for his early involvement in wireless telegraphy and his invention of the coherer in 1890.

Biography

He was born on 23 October 1 ...

and used in the first radio receivers in 1894–96 by Marconi and Oliver Lodge

Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge (12 June 1851 – 22 August 1940) was an English physicist whose investigations into electromagnetic radiation contributed to the development of Radio, radio communication. He identified electromagnetic radiation indepe ...

.

Made in many forms, the coherer consisted of a high resistance electrical contact, composed of conductors touching with a thin resistive surface film, usually oxidation, between them. Radio waves changed the resistance of the contact, causing it to conduct a DC current. The most common form consisted of a glass tube with electrodes at each end, containing loose metal filings in contact with the electrodes. Before a radio wave was applied, this device had a high electrical resistance

The electrical resistance of an object is a measure of its opposition to the flow of electric current. Its reciprocal quantity is , measuring the ease with which an electric current passes. Electrical resistance shares some conceptual paral ...

, in the megohm range. When a radio wave from the antenna was applied across the electrodes it caused the filings to "cohere" or clump together and the coherer's resistance fell, causing a DC current from a battery to pass through it, which rang a bell or produced a mark on a paper tape representing the "dots" and "dashes" of Morse code. Most coherers had to be tapped mechanically between each pulse of radio waves to return them to a nonconductive state.

The coherer was a very poor detector, motivating much research to find better detectors. It worked by complicated thin film surface effects, so scientists of the time did not understand how it worked, except for a vague idea that radio wave detection depended on some mysterious property of "imperfect" electrical contacts. Researchers investigating the effect of radio waves on various types of "imperfect" contacts to develop better coherers, invented crystal detectors.

Braun's experiments

The "unilateral conduction" of crystals was discovered by Karl Ferdinand Braun, a German physicist, in 1874 at theUniversity of Würzburg

The Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg (also referred to as the University of Würzburg, in German ''Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg'') is a public research university in Würzburg, Germany. Founded in 1402, it is one of the ol ...

. He studied copper pyrite (Cu5FeS4), iron pyrite

The mineral pyrite ( ), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue ...

(iron sulfide, FeS2), galena (PbS) and copper antimony sulfide (Cu3SbS4).

This was before radio waves had been discovered, and Braun did not apply these devices practically but was interested in the nonlinear

In mathematics and science, a nonlinear system (or a non-linear system) is a system in which the change of the output is not proportional to the change of the input. Nonlinear problems are of interest to engineers, biologists, physicists, mathe ...

current–voltage characteristic

A current–voltage characteristic or I–V curve (current–voltage curve) is a relationship, typically represented as a chart or graph, between the electric current through a circuit, device, or material, and the corresponding voltage, or p ...

that these sulfides exhibited. Braun's method of making contact with the crystal may have been crucial to his results: he placed the sample on a circle of wire, then touched it with the end of a slender silver wire, a "cat's whisker" contact. Graphing the current as a function of voltage across a contact, he found the result was a line that was flat for current in one direction but curved upward for current in the other direction, instead of a straight line, showing that these substances did not obey Ohm's law

Ohm's law states that the electric current through a Electrical conductor, conductor between two Node (circuits), points is directly Proportionality (mathematics), proportional to the voltage across the two points. Introducing the constant of ...

. Due to this characteristic, some crystals had up to twice as much resistance to current in one direction as they did to current in the other. In 1877 and 1878 he reported further experiments with psilomelane

Psilomelane is a group name for hard black manganese oxides including hollandite and romanechite. Psilomelane consists of hydrous manganese oxide with variable amounts of barium and potassium. Psilomelane is erroneously, and uncommonly, known as ...

, . Braun did investigations which ruled out several possible causes of asymmetric conduction, such as electrolytic action and some types of thermoelectric effects.

Thirty years after these discoveries, in 1899 Braun began experimenting with his crystalline contacts as radio wave detectors. However they were not usable because crystal detectors were not compatible with the paper tape recorder ( siphon recorder), the standard output device used by coherer receivers at the time.

Bose's experiments

Jagadish Chandra Bose first used crystals for radio wave detection in his 60 GHzmicrowave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths shorter than other radio waves but longer than infrared waves. Its wavelength ranges from about one meter to one millimeter, corresponding to frequency, frequencies between 300&n ...

optics experiments at the University of Calcutta

The University of Calcutta, informally known as Calcutta University (), is a Public university, public State university (India), state university located in Kolkata, Calcutta (Kolkata), West Bengal, India. It has 151 affiliated undergraduate c ...

from 1894 to 1900. also reprinted oIndianDefense

Sarkar, Tapan K.; Sengupta, Dipak L. "An appreciation of J. C. Bose's pioneering work in millimeter and microwaves" in Like other scientists since Hertz, Bose was investigating the similarity between radio waves and light by duplicating classic

optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

experiments with radio waves. Sarkar, et al (2006) ''History of Wireless'', pp. 477–483/ref> For a receiver he first used a

coherer

The coherer was a primitive form of radio signal detector used in the first radio receivers during the wireless telegraphy era at the beginning of the 20th century. Its use in radio was based on the 1890 findings of French physicist Édouard Bra ...

consisting of a steel spring pressing against a metal surface with a current passing through it. Dissatisfied with this detector, around 1897 Bose measured the change in resistivity of dozens of metals and metal compounds exposed to microwaves.

He experimented with many substances as contact detectors, focusing on galena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crysta ...

.

His detectors consisted of a small galena crystal with a metal point contact pressed against it with a thumbscrew, mounted inside a closed waveguide

A waveguide is a structure that guides waves by restricting the transmission of energy to one direction. Common types of waveguides include acoustic waveguides which direct sound, optical waveguides which direct light, and radio-frequency w ...

ending in a horn antenna

A horn antenna or microwave horn is an antenna (radio), antenna that consists of a flaring metal waveguide shaped like a horn (acoustic), horn to direct radio waves in a beam. Horns are widely used as antennas at Ultrahigh frequency, UHF and m ...

to collect the microwaves. Bose passed a current from a battery through the crystal, and used a galvanometer

A galvanometer is an electromechanical measuring instrument for electric current. Early galvanometers were uncalibrated, but improved versions, called ammeters, were calibrated and could measure the flow of current more precisely. Galvanomet ...

to measure it. When microwaves struck the crystal the galvanometer registered a drop in resistance of the detector. Thomas Lee has pointed out that this detector did not function as a rectifier like later crystal detectors, but as a thermal detector called a bolometer

A bolometer is a device for measuring radiant heat by means of a material having a temperature-dependent electrical resistance. It was invented in 1878 by the American astronomer Samuel Pierpont Langley.

Principle of operation

A bolometer ...

. At the time scientists thought that radio wave detectors functioned by some mechanism analogous to the way the eye detected light, and Bose found his detector was also sensitive to visible light and ultraviolet, leading him to call it an ''artificial retina''. He patented the detector 30 September 1901. This is often considered the first patent on a semiconductor device.

Pickard: Discovery of rectification

Greenleaf Whittier Pickard, an engineer with the American Wireless Telephone and Telegraph Co. invented the rectifying contact detector, discovering rectification of radio waves in 1902 while experimenting with acoherer

The coherer was a primitive form of radio signal detector used in the first radio receivers during the wireless telegraphy era at the beginning of the 20th century. Its use in radio was based on the 1890 findings of French physicist Édouard Bra ...

detector consisting of a steel needle resting across two carbon blocks. On 29 May 1902 he was operating this device, listening to a radiotelegraphy station. Coherers required an external current source to operate, so he had the coherer and telephone earphone connected in series with a 3 cell battery to provide power to operate the earphone. Annoyed by background "frying" noise caused by the current through the carbon, he reached over to cut two of the battery cells out of the circuit to reduce the current

The generation of an audio signal without a DC bias battery made Pickard realize the device was acting as a rectifier. Pickard began to experiment and found an oxidized steel surface worked better, so he tried magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula . It is one of the iron oxide, oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetism, ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetization, magnetized to become a ...

(Fe3O4). On 16 October 1902 he received a radio station using magnetite touched by a copper wire, the first reception by a crystal detector.

During the next seven years, Pickard conducted an exhaustive search to find which substances formed the most sensitive detecting contacts, eventually testing thousands of minerals, and discovered about 250 rectifying crystals. In 1906 he obtained a sample of fused silicon

Silicon is a chemical element; it has symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic lustre, and is a tetravalent metalloid (sometimes considered a non-metal) and semiconductor. It is a membe ...

, an artificial product recently synthesized in electric furnaces, and it outperformed all other substances. He patented the silicon detector 30 August 1906. In 1907 he formed a company to manufacture his detectors, Wireless Specialty Products Co., and the silicon detector was the first crystal detector to be sold commercially. Pickard went on to produce other detectors using the crystals he had discovered; the more popular being the iron pyrite

The mineral pyrite ( ), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue ...

"Pyron" detector and the zincite–chalcopyrite

Chalcopyrite ( ) is a copper iron sulfide mineral and the most abundant copper ore mineral. It has the chemical formula CuFeS2 and crystallizes in the tetragonal system. It has a brassy to golden yellow color and a Mohs scale, hardness of 3.5 to 4 ...

crystal-to-crystal "Perikon" detector in 1908, which stood for "PERfect pIcKard cONtact".

Crystal detectors become popular

Around 1906 it was recognised that mineral crystals could be a better detector than the coherer, crystal radios began to be made, and many new crystal detectors were invented. In 23 March 1906 Henry Harrison Chase Dunwoody, a retired general in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, patented thesilicon carbide

Silicon carbide (SiC), also known as carborundum (), is a hard chemical compound containing silicon and carbon. A wide bandgap semiconductor, it occurs in nature as the extremely rare mineral moissanite, but has been mass-produced as a powder a ...

(carborundum

Silicon carbide (SiC), also known as carborundum (), is a hard chemical compound containing silicon and carbon. A wide bandgap semiconductor, it occurs in nature as the extremely rare mineral moissanite, but has been mass-produced as a powder ...

) detector, Henry H. C. Dunwoody, ''Wireless Telegraph System'', filed: 23 March 1906, granted: 4 December 1906 using another recent product of electric furnaces. The semiconductor silicon carbide has a wide band gap

In solid-state physics and solid-state chemistry, a band gap, also called a bandgap or energy gap, is an energy range in a solid where no electronic states exist. In graphs of the electronic band structure of solids, the band gap refers to t ...

and Pickard discovered the detector's sensitivity could be increased by applying a forward bias, a DC potential of around a volt from a battery and potentiometer, to it.

Braun began to experiment with crystals as radio detectors in 1899 and in 1906 patented a galena cat whisker detector in Germany.

German patent 178871 Karl Ferdinand Braun, Wellenempfindliche Kontaktstel

', filed: 18 February 1906, granted: 22 October 1906 In 1906 L. W. Austin invented a silicon–

tellurium

Tellurium is a chemical element; it has symbol Te and atomic number 52. It is a brittle, mildly toxic, rare, silver-white metalloid. Tellurium is chemically related to selenium and sulfur, all three of which are chalcogens. It is occasionally fou ...

detector, Louis W. Austin, "Receiver", filed: 27 October 1906, granted: 5 March 1907 in 1907 Pickard invented the molybdenite

Molybdenite is a mineral of molybdenum disulfide, Mo S2. Similar in appearance and feel to graphite, molybdenite has a lubricating effect that is a consequence of its layered structure. The atomic structure consists of a sheet of molybdenum at ...

detector, Greenleaf Whittier Pickard, "Oscillation-detecting means for receiving intelligence communicated by electric waves", filed: 11 March 1907, granted: 17 November 1908 and in 1911 Thompson H. Lyon invented the cerussite

Cerussite (also known as lead carbonate or white lead ore) is a mineral consisting of lead carbonate with the chemical formula PbCO3, and is an important ore of lead. The name is from the Latin ''cerussa'', white lead. ''Cerussa nativa'' was ...

detector. Thompson Harris Lyon, "Wave-detector", filed: 12 October 1911, granted: 14 November 1911 In Germany a tellurium-carbon detector became popular, called "the Bronc cell". In 1908 Wichi Torikata at Tokyo Imperial University investigated 200 minerals and found cassiterite

Cassiterite is a tin oxide mineral, SnO2. It is generally opaque, but it is translucent in thin crystals. Its luster and multiple crystal faces produce a desirable gem. Cassiterite was the chief tin ore throughout ancient history and remains ...

(tin oxide), pyrolusite

Pyrolusite is a mineral consisting essentially of manganese dioxide ( Mn O2) and is important as an ore of manganese.. It is a black, amorphous appearing mineral, often with a granular, fibrous, or columnar structure, sometimes forming reniform ...

(manganese dioxide), zincite, galena, and pyrite were sensitive, and subsequently tested all the mineral samples at the Mineral College and found 34 rectifying minerals. He patented a mineral detector in 1908.Japanese patent 15345, Wichi Torikata, "The koseki (or mineral detector)", filed: 12 August 1908, granted: 8 December 1908 Lee De Forest #REDIRECT Lee de Forest

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from other capitalisation ...

, George Washington Pierce, and William Henry Eccles also studied mineral detectors.

The fine wire catwhisker contact invented early in the detector's history wasn't patented until 1911 by Pickard Greenleaf Whittier Pickard, "Detector for wireless telegraphy and telephony", filed: 21 June 1911, granted: 21 July 1914

Use during the wireless telegraphy era

Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquess of Marconi ( ; ; 25 April 1874 – 20 July 1937) was an Italian electrical engineer, inventor, and politician known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based Wireless telegraphy, wireless tel ...

developed the first practical wireless telegraphy transmitters and receivers in 1896, and radio began to be used for communication around 1899. The coherer was used as detector for the first 10 years, until around 1906. During the wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is the transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using electrical cable, cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimenta ...

era prior to 1920, there was virtually no broadcasting

Broadcasting is the data distribution, distribution of sound, audio audiovisual content to dispersed audiences via a electronic medium (communication), mass communications medium, typically one using the electromagnetic spectrum (radio waves), ...

; radio served as a point-to-point text messaging service. Until the triode

A triode is an electronic amplifier, amplifying vacuum tube (or ''thermionic valve'' in British English) consisting of three electrodes inside an evacuated glass envelope: a heated Electrical filament, filament or cathode, a control grid, grid ...

vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, thermionic valve (British usage), or tube (North America) is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied. It ...

began to be used around World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, radio receivers had no amplification and were powered only by the radio waves picked up by their antennae. Long distance radio communication depended on high power transmitters (up to 1 megawatt), huge wire antennas, and a receiver with a sensitive detector.

Around 1907 crystal detectors replaced the coherer

The coherer was a primitive form of radio signal detector used in the first radio receivers during the wireless telegraphy era at the beginning of the 20th century. Its use in radio was based on the 1890 findings of French physicist Édouard Bra ...

and electrolytic detector to become the most widely used form of radio detector.The 1911 edition of the US Navy's manual of radio stated: "''There are but two types of detectors now in use: crystal or rectifying detectors and the electrolytic. Coherers and microphones '' nother type of coherer detector' are practically obsolete, and comparatively few of the magnetic and Audion or valve '' riode' detectors have been installed.''" Until the triode vacuum tube began to be used during World War I, crystals were the best radio reception technology, used in sophisticated receivers in wireless telegraphy stations, as well as in homemade crystal radios.The 1913 edition of the US Navy's manual of radio stated: "''Only one type of detector is now in use: the crystal. Coherers and microphones are practically obsolete, and comparatively few magnetic and Audion or valve '' riode' detectors have been installed.''" In transoceanic radiotelegraphy stations elaborate inductively coupled crystal receivers fed by mile long wire antennas were used to receive transatlantic telegram traffic.Marconi used carborundum detectors beginning around 1907 in his first commercial transatlantic wireless link between Newfoundland, Canada and Clifton, Ireland.

Much research went into finding better detectors and many types of crystals were tried.

The goal of researchers was to find rectifying crystals that were less fragile and sensitive to vibration than galena and pyrite. Another desired property was tolerance of high currents; many crystals would become insensitive when subjected to discharges of atmospheric electricity from the outdoor wire antenna, or current from the powerful spark transmitter leaking into the receiver. Carborundum proved to be the best of these; it could rectify when clamped firmly between flat contacts. Therefore, carborundum detectors were used in shipboard wireless stations where waves caused the floor to rock, and military stations where gunfire was expected.

In 1907–1909, George Washington Pierce at Harvard conducted research into how crystal detectors worked. Using an oscilloscope

An oscilloscope (formerly known as an oscillograph, informally scope or O-scope) is a type of electronic test instrument that graphically displays varying voltages of one or more signals as a function of time. Their main purpose is capturing i ...

made with Braun's new cathode ray tube

A cathode-ray tube (CRT) is a vacuum tube containing one or more electron guns, which emit electron beams that are manipulated to display images on a phosphorescent screen. The images may represent electrical waveforms on an oscilloscope, a ...

, he produced the first pictures of the waveforms in a working detector, proving that it did rectify the radio wave. During this era, before modern solid-state physics

Solid-state physics is the study of rigid matter, or solids, through methods such as solid-state chemistry, quantum mechanics, crystallography, electromagnetism, and metallurgy. It is the largest branch of condensed matter physics. Solid-state phy ...

, most scientists believed that crystal detectors operated by some thermoelectric effect. Although Pierce did not discover the mechanism by which it worked, he did prove that the existing theories were wrong; his oscilloscope waveforms showed there was no phase delay between the voltage and current in the detector, ruling out thermal mechanisms. Pierce originated the name ''crystal rectifier''.

Between about 1905 and 1915 new types of radio transmitters were developed which produced continuous sinusoidal waves: the arc converter

The arc converter, sometimes called the arc transmitter, or Poulsen arc after Danish engineer Valdemar Poulsen who invented it in 1903, was a variety of spark transmitter used in early wireless telegraphy. The arc converter used an electric arc ...

(Poulsen arc) and the Alexanderson alternator

An Alexanderson alternator is a rotating machine, developed by Ernst Alexanderson beginning in 1904, for the generation of high-frequency alternating current for use as a radio transmitter. It was one of the first devices capable of generating th ...

. These slowly replaced the old damped wave spark transmitters. Besides having a longer transmission range, these transmitters could be modulated

Signal modulation is the process of varying one or more properties of a periodic waveform in electronics and telecommunication for the purpose of transmitting information.

The process encodes information in form of the modulation or message ...

with an audio signal

An audio signal is a representation of sound, typically using either a changing level of electrical voltage for analog signals or a series of binary numbers for Digital signal (signal processing), digital signals. Audio signals have frequencies i ...

to transmit sound by amplitude modulation

Amplitude modulation (AM) is a signal modulation technique used in electronic communication, most commonly for transmitting messages with a radio wave. In amplitude modulation, the instantaneous amplitude of the wave is varied in proportion t ...

(AM). It was found that, unlike the coherer, the rectifying action of the crystal detector allowed it to demodulate an AM radio signal, producing audio (sound). Although other detectors used at the time, the electrolytic detector, Fleming valve

The Fleming valve, also called the Fleming oscillation valve, was a thermionic valve or vacuum tube invented in 1904 by English physicist John Ambrose Fleming as a detector for early radio receivers used in electromagnetic wireless telegrap ...

and the triode could also rectify AM signals, crystals were the simplest, cheapest AM detector. As more and more radio stations began experimenting with transmitting sound after World War I, a growing community of radio listeners built or bought crystal radios to listen to them.

Use continued to grow until the 1920s when vacuum tube radios replaced them.

Crystodyne: negative resistance diodes

Some semiconductor diodes have a property called '' negative resistance'' which means the current through them decreases as the voltage increases over a part of their I–V curve. This allows a diode, normally apassive

Passive may refer to:

* Passive voice, a grammatical voice common in many languages, see also Pseudopassive

* Passive language, a language from which an interpreter works

* Passivity (behavior), the condition of submitting to the influence of ...

device, to function as an amplifier

An amplifier, electronic amplifier or (informally) amp is an electronic device that can increase the magnitude of a signal (a time-varying voltage or current). It is a two-port electronic circuit that uses electric power from a power su ...

or oscillator

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulum ...

. For example, when connected to a resonant circuit and biased with a DC voltage, the negative resistance of the diode can cancel the positive resistance of the circuit, creating a circuit with zero AC resistance, in which spontaneous oscillating currents arise. This property was first observed in crystal detectors around 1909 by William Henry Eccles

and Pickard.

They noticed that when their detectors were biased with a DC voltage to improve their sensitivity, they would sometimes break into spontaneous oscillations. However these researchers just published brief accounts and did not pursue the effect.

The first person to exploit negative resistance practically was self-taught Russian physicist Oleg Losev, who devoted his career to the study of crystal detectors. In 1922 working at the new Nizhny Novgorod Radio Laboratory he discovered negative resistance in biased zincite (zinc oxide

Zinc oxide is an inorganic compound with the Chemical formula, formula . It is a white powder which is insoluble in water. ZnO is used as an additive in numerous materials and products including cosmetics, Zinc metabolism, food supplements, rubbe ...

) point contact junctions.

Lee, Thomas H. (2004) The Design of CMOS Radio-Frequency Integrated Circuits, 2nd Ed., p. 20/ref> He realized that amplifying crystals could be an alternative to the fragile, expensive, energy-wasting vacuum tube. He used biased negative resistance crystal junctions to build solid-state

amplifier

An amplifier, electronic amplifier or (informally) amp is an electronic device that can increase the magnitude of a signal (a time-varying voltage or current). It is a two-port electronic circuit that uses electric power from a power su ...

s, oscillator

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulum ...

s, and amplifying and regenerative radio receiver

In radio communications, a radio receiver, also known as a receiver, a wireless, or simply a radio, is an electronic device that receives radio waves and converts the information carried by them to a usable form. It is used with an antenna. ...

s, 25 years before the invention of the transistor.

an"The Crystodyne Principle"

''Radio News'', September 1924, pages 294-295, 431. Later he even built a

superheterodyne receiver

A superheterodyne receiver, often shortened to superhet, is a type of radio receiver that uses frequency mixing to convert a received signal to a fixed intermediate frequency (IF) which can be more conveniently processed than the original car ...

. However his achievements were overlooked because of the success of vacuum tubes. His technology was dubbed "Crystodyne" by science publisher Hugo Gernsback

Hugo Gernsback (; born Hugo Gernsbacher, August 16, 1884 – August 19, 1967) was a Luxembourgish American editor and magazine publisher whose publications included the first science fiction magazine, ''Amazing Stories''. His contributions to ...

one of the few people in the West who paid attention to it. After ten years he abandoned research into this technology and it was forgotten.

The negative resistance diode was rediscovered with the invention of the tunnel diode

A tunnel diode or Esaki diode is a type of semiconductor diode that has effectively " negative resistance" due to the quantum mechanical effect called tunneling. It was invented in August 1957 by Leo Esaki and Yuriko Kurose when working ...

in 1957, for which Leo Esaki won the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

. Today, negative resistance diodes such as the Gunn diode and IMPATT diode are widely used as microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths shorter than other radio waves but longer than infrared waves. Its wavelength ranges from about one meter to one millimeter, corresponding to frequency, frequencies between 300&n ...

oscillators in such devices as radar speed gun

A radar speed gun, also known as a radar gun, speed gun, or speed trap gun, is a device used to measure the speed of moving objects. It is commonly used by police to check the speed of moving vehicles while conducting traffic enforcement, and i ...

s and garage door opener

A garage door opener is a motorized device that opens and closes a garage door controlled by switches on the garage wall. Most also include a handheld radio remote control carried by the owner, which can be used to open and close the door from ...

s.

Discovery of the light emitting diode (LED)

In 1907 British Marconi engineer Henry Joseph Round noticed that when direct current was passed through asilicon carbide

Silicon carbide (SiC), also known as carborundum (), is a hard chemical compound containing silicon and carbon. A wide bandgap semiconductor, it occurs in nature as the extremely rare mineral moissanite, but has been mass-produced as a powder a ...

(carborundum) point contact junction, a spot of greenish, bluish, or yellowish light was given off at the contact point. Round had constructed a light emitting diode (LED). However he just published a brief two paragraph note about it and did no further research.

While investigating crystal detectors in the mid-1920s at Nizhny Novgorod, Oleg Losev independently discovered that biased carborundum and zincite junctions emitted light.

Losev was the first to analyze this device, investigate the source of the light, propose a theory of how it worked, and envision practical applications. He published his experiments in 1927 in a Russian journal,

English version published as

and the 16 papers he published on LEDs between 1924 and 1930 constitute a comprehensive study of this device. Losev did extensive research into the mechanism of light emission.

He measured rates of evaporation of benzine from the crystal surface and found it was not accelerated when light was emitted, concluding that the luminescence was a "cold" light not caused by thermal effects. He theorized correctly that the explanation of the light emission was in the new science of quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

, speculating that it was the inverse of the photoelectric effect

The photoelectric effect is the emission of electrons from a material caused by electromagnetic radiation such as ultraviolet light. Electrons emitted in this manner are called photoelectrons. The phenomenon is studied in condensed matter physi ...

discovered by Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

in 1905.

He wrote to Einstein about it, but did not receive a reply. Losev designed practical carborundum electroluminescent lights, but found no one interested in commercially producing these weak light sources.

Losev died in World War II. Due partly to the fact that his papers were published in Russian and German, and partly to his lack of reputation (his upper class birth barred him from a college education or career advancement in Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

society, so he never held an official position higher than technician) his work is not well known in the West.

Use during the broadcast era

In the 1920s, the amplifyingtriode

A triode is an electronic amplifier, amplifying vacuum tube (or ''thermionic valve'' in British English) consisting of three electrodes inside an evacuated glass envelope: a heated Electrical filament, filament or cathode, a control grid, grid ...

vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, thermionic valve (British usage), or tube (North America) is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied. It ...

, invented in 1907 by Lee De Forest #REDIRECT Lee de Forest

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from other capitalisation ...

, replaced earlier technology in both radio transmitters and receivers.The 1918 edition of the US Navy's manual of radio stated: "''There are two types of detectors now in use: the Audion '' riode' and the crystal or rectifying detector. Coherers and microphones '' nother type of coherer detector' are practically obsolete... but the use of Audions...is increasing.''"

AM radio broadcasting

Radio broadcasting is the broadcasting of audio signal, audio (sound), sometimes with related metadata, by radio waves to radio receivers belonging to a public audience. In terrestrial radio broadcasting the radio waves are broadcast by a lan ...