Benjamin Baker (engineer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Benjamin Baker (31 March 1840 – 19 May 1907) was an English civil engineer who worked in mid to late

He published a timely book on Long Railway Bridges in the 1870s which advocated the introduction of steel, and showed that much longer spans were possible using this material. The book is remarkably prescient for the way the properties of steel could be exploited in structures.

He published a timely book on Long Railway Bridges in the 1870s which advocated the introduction of steel, and showed that much longer spans were possible using this material. The book is remarkably prescient for the way the properties of steel could be exploited in structures.

Baker said in his statement to the court that he had built over of railway viaduct, referring to his design of the elevated railroad in New York City in 1868, some of which still survives in

Baker said in his statement to the court that he had built over of railway viaduct, referring to his design of the elevated railroad in New York City in 1868, some of which still survives in

With Sir John Fowler, he designed and engineered the Forth Bridge after the Tay bridge collapse. It was a

With Sir John Fowler, he designed and engineered the Forth Bridge after the Tay bridge collapse. It was a

On the completion of this undertaking in 1890 he was appointed Knight Commander of the

On the completion of this undertaking in 1890 he was appointed Knight Commander of the

Benjamin Baker – Celebrating Frome's forgotten engineering hero

{{DEFAULTSORT:Baker, Benjamin 1840 births 1907 deaths People from Frome British railway pioneers People educated at Pate's Grammar School British bridge engineers British railway civil engineers Fellows of the Royal Society Presidents of the Institution of Civil Engineers Presidents of the Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers People associated with transport in London Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath People from Pangbourne Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 19th-century British businesspeople

Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

. He helped develop the early underground railways in London with Sir John Fowler, but he is best known for his work on the Forth Bridge. He made many other notable contributions to civil engineering, including his work as an expert witness

An expert witness, particularly in common law countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States, is a person whose opinion by virtue of education, training, certification, skills or experience, is accepted by the judge as ...

at the public inquiry into the Tay Bridge disaster. Later, he helped design and build the first Aswan Dam

The Aswan Dam, or Aswan High Dam, is one of the world's largest embankment dams, which was built across the Nile in Aswan, Egypt, between 1960 and 1970. When it was completed, it was the tallest earthen dam in the world, surpassing the Chatuge D ...

.

Early life and career

He was born in Keyford, which is now part of Frome, Somerset in 1840, the son of Benjamin Baker, principal assistant at Tondu Ironworks, and Sarah Hollis. There is a plaque on their house in Butts Hill. He was educated at Cheltenham Grammar School and, at the age of 16, became an apprentice at Messrs Price and Fox at the Neath Abbey Iron Works. After his apprenticeship he spent two years as an assistant to Mr. W.H. Wilson. Later, he became associated with Sir John Fowler in London. He took part in the construction of theMetropolitan Railway

The Metropolitan Railway (also known as the Met) was a passenger and goods railway that served London from 1863 to 1933, its main line heading north-west from the capital's financial heart in the City to what were to become the Middlesex su ...

(London). He was also a key expert witness

An expert witness, particularly in common law countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States, is a person whose opinion by virtue of education, training, certification, skills or experience, is accepted by the judge as ...

in the Tay Bridge disaster of 1879.

He designed the cylindrical vessel in which Cleopatra's Needle, now standing on the Thames Embankment

The Thames Embankment was built as part of the London Main Drainage (1859-1875) by the Metropolitan Board of Works, a pioneering Victorian civil engineering project which housed intercept sewers, roads and underground railways and embanked the ...

, London, was brought over from Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

to England in 1877–1878.

He obtained an extremely large professional practice, ranging over almost every branch of civil engineering, and was more or less directly concerned with most of the great engineering achievements of his day.

Bridges

Tay bridge disaster

In 1880, Baker was called as anexpert witness

An expert witness, particularly in common law countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States, is a person whose opinion by virtue of education, training, certification, skills or experience, is accepted by the judge as ...

to the inquiry into the Tay Bridge disaster, in which part of the bridge failed and collapsed into the water. Although he was acting on behalf of Thomas Bouch

Sir Thomas Bouch (; 22 February 1822 – 30 October 1880) was a British railway engineer. He was born in Thursby, near Carlisle, Cumbria, Carlisle, Cumberland, and lived in Edinburgh. As manager of the Edinburgh and Northern Railway he introduc ...

, the builder of the first railway bridge across the Tay, he performed his role with independence and tenacity. His testified against the theory that the bridge was blown over by the wind that night. He made a meticulous survey of structures at or near the bridge, and concluded that wind speeds were not excessive on the night of the disaster. The official analysis of the failure suggested that a wind pressure of over 30 pounds per square foot was needed to cause toppling of the structure. Baker examined smaller structures in the vicinity of the bridge and concluded that the pressure could not have exceeded 15 pounds per square foot on the night of the bridge failure. Such smaller structures included walls, ballast on the track on the bridge, and both signal boxes either on or very near the bridge.

Baker said in his statement to the court that he had built over of railway viaduct, referring to his design of the elevated railroad in New York City in 1868, some of which still survives in

Baker said in his statement to the court that he had built over of railway viaduct, referring to his design of the elevated railroad in New York City in 1868, some of which still survives in Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

(unused).

By this time he had already become established as an authority on bridge construction. Shortly afterwards he was engaged on the work which made his reputation with the general public: the design and erection of the Forth Bridge (1890) in collaboration with Sir John Fowler and William Arrol. It was an almost unique design as a large cantilever bridge

A cantilever bridge is a bridge built using structures that project horizontally into space, supported on only one end (called cantilevers). For small footbridges, the cantilevers may be simple beam (structure), beams; however, large cantilever ...

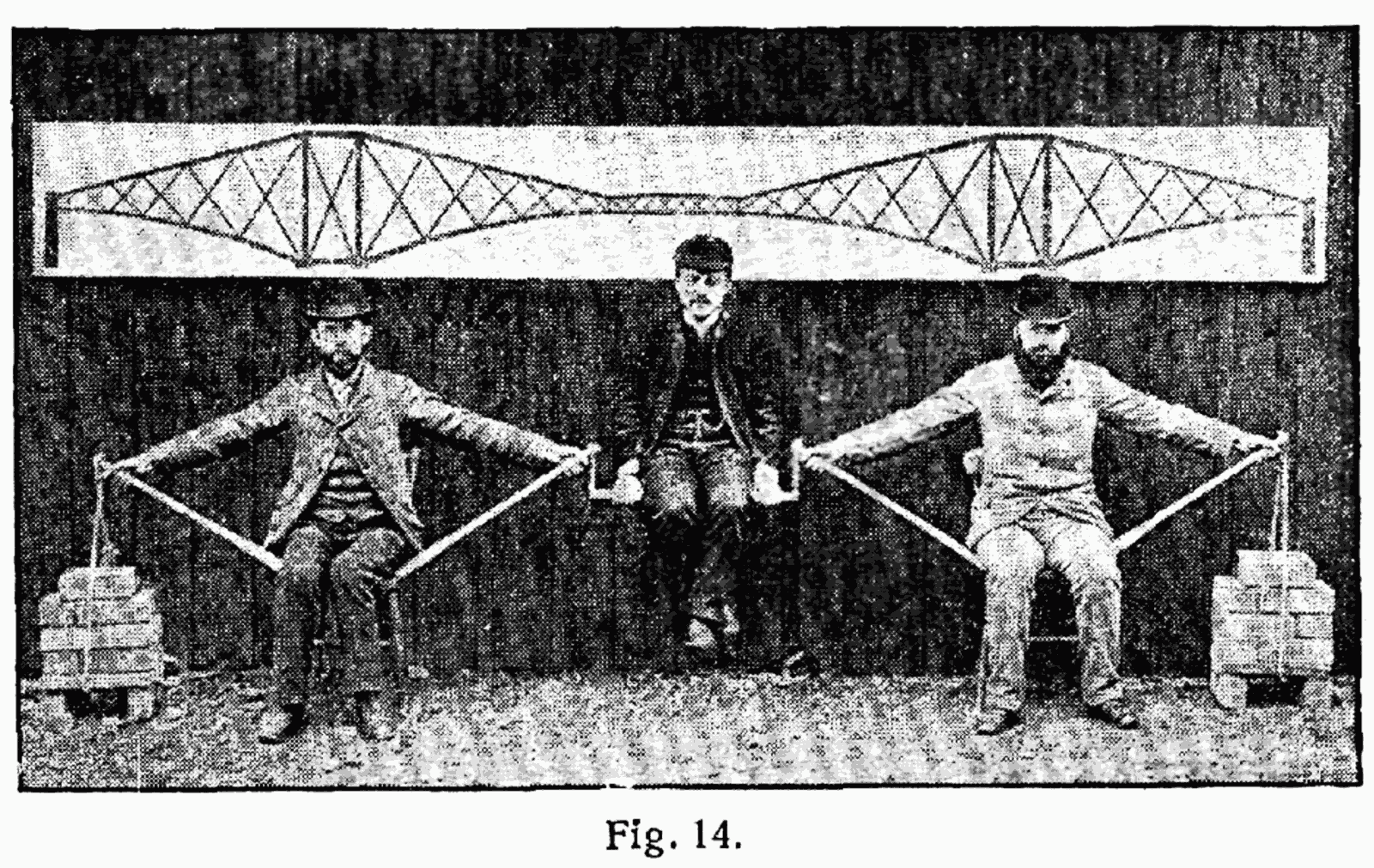

, and was built entirely in steel, another unprecedented development in bridge engineering. Stiffness was provided by hollow tubes which were riveted together so as to make sound joints. Baker promoted his design in numerous public lectures, and arranged demonstrations of the stability of the cantilever by using his assistants as stage props.

Forth Bridge

With Sir John Fowler, he designed and engineered the Forth Bridge after the Tay bridge collapse. It was a

With Sir John Fowler, he designed and engineered the Forth Bridge after the Tay bridge collapse. It was a cantilever bridge

A cantilever bridge is a bridge built using structures that project horizontally into space, supported on only one end (called cantilevers). For small footbridges, the cantilevers may be simple beam (structure), beams; however, large cantilever ...

and Baker gave numerous lectures on the principles which lay behind his design. Thomas Bouch

Sir Thomas Bouch (; 22 February 1822 – 30 October 1880) was a British railway engineer. He was born in Thursby, near Carlisle, Cumbria, Carlisle, Cumberland, and lived in Edinburgh. As manager of the Edinburgh and Northern Railway he introduc ...

had originally been awarded the contract but he lost it after the Tay Bridge Inquiry reported in June 1880. The bridge was built entirely in steel, much stronger than cast iron. He used hollow steel tubes to create the cantilever, and it was then the largest bridge of its kind in the world. The bridge is regarded as an engineering marvel. It is in length, and the double track is elevated above high tide. It consists of two main spans of , two side spans of , 15 approach spans of and five of ). Each main span comprises two 680 ft (210 m) cantilever arms supporting a central 350 ft (110 m) span girder bridge. The three great four-tower cantilever structures are 340 ft (104 m) tall, each 70 ft (21 m) diameter foot resting on a separate foundation. The southern group of foundations had to be constructed as caissons under compressed air, to a depth of 90 ft (27 m). At its peak, approximately 4,600 workers were employed in its construction. Initially, it was recorded that 57 lives were lost however after extensive research by local historians, the figure has been revised upwards to 98. Eight men who fell from the bridge were saved by boats positioned in the river under work areas. More than 55,000 tons of steel were used, as well as 18,122 m³ of granite and over eight million rivets. The bridge was opened on 4 March 1890 by the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, who drove home the last rivet, which was gold plated and suitably inscribed. A contemporary materials analysis of the bridge, c. 2002, found that the steel in the bridge is of good quality, with little variation.

The use of a cantilever in bridge design was not a new idea, but the scale of Baker's undertaking was a pioneering effort, later followed in different parts of the world. Much of the work done was without precedent, including calculations for incidence of erection stresses, provisions made for reducing future maintenance costs, calculations for wind pressures made evident by the Tay Bridge disaster, the effect of temperature stresses on the structure, and so on.

Where possible, the bridge used natural features such as Inchgarvie, an island, the promontories on either side of the firth at this point, and also the high banks on either side. The remains of Thomas Bouch

Sir Thomas Bouch (; 22 February 1822 – 30 October 1880) was a British railway engineer. He was born in Thursby, near Carlisle, Cumbria, Carlisle, Cumberland, and lived in Edinburgh. As manager of the Edinburgh and Northern Railway he introduc ...

's first attempts at his bridge can also be seen on the island.

The bridge has a speed limit of 50 mph (80 km/h) for passenger trains and 20 mph (32 km/h) for freight trains. The weight limit for any train on the bridge is 1,422 tonnes (1,442,000 kg) although this is waived for the frequent coal trains, provided two such trains do not simultaneously occupy the bridge. The route availability code is RA8, meaning any current UK locomotive can use the bridge, which was designed to accommodate heavier steam locomotives. Up to 190–200 trains per day crossed the bridge in 2006. A structure like the Forth Bridge needs constant maintenance and the ancillary works for the bridge included not only a maintenance workshop and yard but a railway "colony" of some fifty houses at Dalmeny Station.

" Painting the Forth Bridge" is a colloquial term for a never-ending task (a modern rendering of the myth of Sisyphus

In Greek mythology, Sisyphus or Sisyphos (; Ancient Greek: Σίσυφος ''Sísyphos'') was the founder and king of Ancient Corinth, Ephyra (now known as Corinth). He reveals Zeus's abduction of Aegina (mythology), Aegina to the river god As ...

), coined on the erroneous belief that, at one time in the history of the bridge, repainting was required and commenced immediately upon completion of the previous repaint. According to a 2004 '' New Civil Engineer'' report on contemporary maintenance, such a practice never existed, although under British Rail

British Railways (BR), which from 1965 traded as British Rail, was a state-owned company that operated most rail transport in Great Britain from 1948 to 1997. Originally a trading brand of the Railway Executive of the British Transport Comm ...

management, and before, the bridge had a permanent maintenance crew.

A contemporary repainting of the bridge commenced with a contract award in 2002, for a schedule of work expected to continue until March 2009, involving the application of 20,000 m2 of paint at an estimated cost of £13M a year. This new coat of paint is expected to have a life of at least 25 years. In 2008 the total cost was revised upwards to £180M, and projections for finishing the job to 2012. In a report produced by JE Jacobs, Grant Thornton and Faber Maunsell in 2007 which reviewed the alternative options for a second road crossing, it was stated that the estimated working life of the Forth Bridge was in excess of 100 years.

Honours and Old Aswan Dam

On the completion of this undertaking in 1890 he was appointed Knight Commander of the

On the completion of this undertaking in 1890 he was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince of Wales (the future King George IV), while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III ...

(KCMG), and in the same year the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

recognised his scientific attainments by electing him one of its fellows. In 1892 the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

recognised the work of Fowler and Baker by the joint award of the Poncelet Prize; Baker received 2000 francs because the prize money was doubled. Ten years later at the formal opening of the first Aswan Dam

The Aswan Dam, or Aswan High Dam, is one of the world's largest embankment dams, which was built across the Nile in Aswan, Egypt, between 1960 and 1970. When it was completed, it was the tallest earthen dam in the world, surpassing the Chatuge D ...

, for which he was consulting engineer, he was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

(KCB). He served as president of the Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a Charitable organization, charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters ar ...

between May 1895 and June 1896. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

in 1899 and an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was establis ...

in 1902.

Underground railways

Baker also played a large part in the introduction of the system widely adopted in London of constructing underground railways in deep tubular tunnels built up of cast iron segments. He was also involved in an unsuccessful scheme in 1899 proposed by the North West London Railway to build atube

Tube or tubes may refer to:

* ''Tube'' (2003 film), a 2003 Korean film

* "Tubes" (Peter Dale), performer on the Soccer AM television show

* Tube (band), a Japanese rock band

* Tube & Berger, the alias of dance/electronica producers Arndt Rör ...

line in north-west London.

Writing

Baker was also the author of many papers on engineering subjects. In 1872 Baker wrote a series of articles titled, "The Strength of Brickwork." In these articles Baker argued that the tensile strength of cement should not be neglected in calculating the strength of brickwork. He wrote that if the cement was neglected then several structures of his time should have collapsed.Death

He died at his home, Bowden Green, inPangbourne

Pangbourne is a village and civil parish on the River Thames in the West Berkshire unitary area of the county of Berkshire, England. Pangbourne has shops, churches, schools and a village hall. Outside its nucleated village, grouped developed are ...

, Berkshire where he lived in his later years and was buried in the village of Idbury in Oxfordshire, next to his mother. He is commemorated in a stained glass window on the northside of the nave at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

.'The Abbey Scientists' Hall, A.R. p45: London; Roger & Robert Nicholson; 1966

References

* * * * * * *External links

* * * *Benjamin Baker – Celebrating Frome's forgotten engineering hero

{{DEFAULTSORT:Baker, Benjamin 1840 births 1907 deaths People from Frome British railway pioneers People educated at Pate's Grammar School British bridge engineers British railway civil engineers Fellows of the Royal Society Presidents of the Institution of Civil Engineers Presidents of the Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers People associated with transport in London Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath People from Pangbourne Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 19th-century British businesspeople