Ba'albek on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Baalbek (; ; ) is a city located east of the

After

After

Bk. V, Ch. 15, §22

. and on

In 1516, Baalbek was conquered with the rest of Syria by the Ottoman sultan

In 1516, Baalbek was conquered with the rest of Syria by the Ottoman sultan

Tradition holds that many Christians quit the Baalbek region in the eighteenth century for the newer, more secure town of

The Tell Baalbek temple complex, fortified as the town's citadel during the Middle Ages, was constructed from local stone, mostly white

The Tell Baalbek temple complex, fortified as the town's citadel during the Middle Ages, was constructed from local stone, mostly white  The Temple of Jupiter—once wrongly credited to

The Temple of Jupiter—once wrongly credited to

File:The Round Temple and the Temple of the Muses located outside the sanctuary complex, Heliopolis (Baalbek), Lebanon.jpg, The Round Temple and the Temple of the Muses located outside the sanctuary complex

File:Propylaea of Baalbek temples complex 16062.JPG, Remains of the Propylaeum, the eastern entrance to the site

File:Great Court of Temples Complex in Baalbek (49856240571).jpg, The Great Court of Temples Complex

File:Temple of Venus, Baalbek 14114.JPG, Temple of Venus

File:Baalbeck Temple.jpg, Massive columns of the Temple of Jupiter

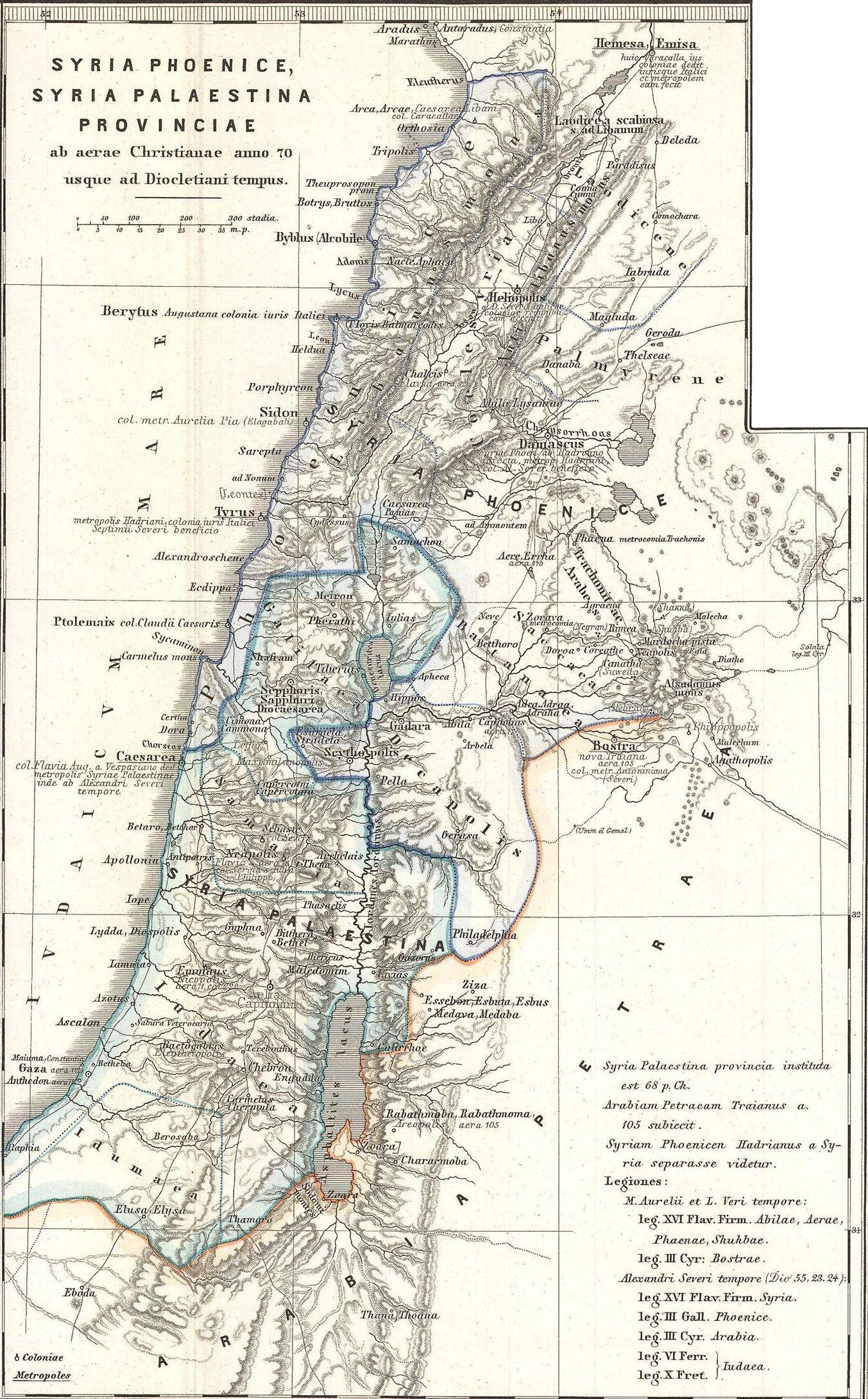

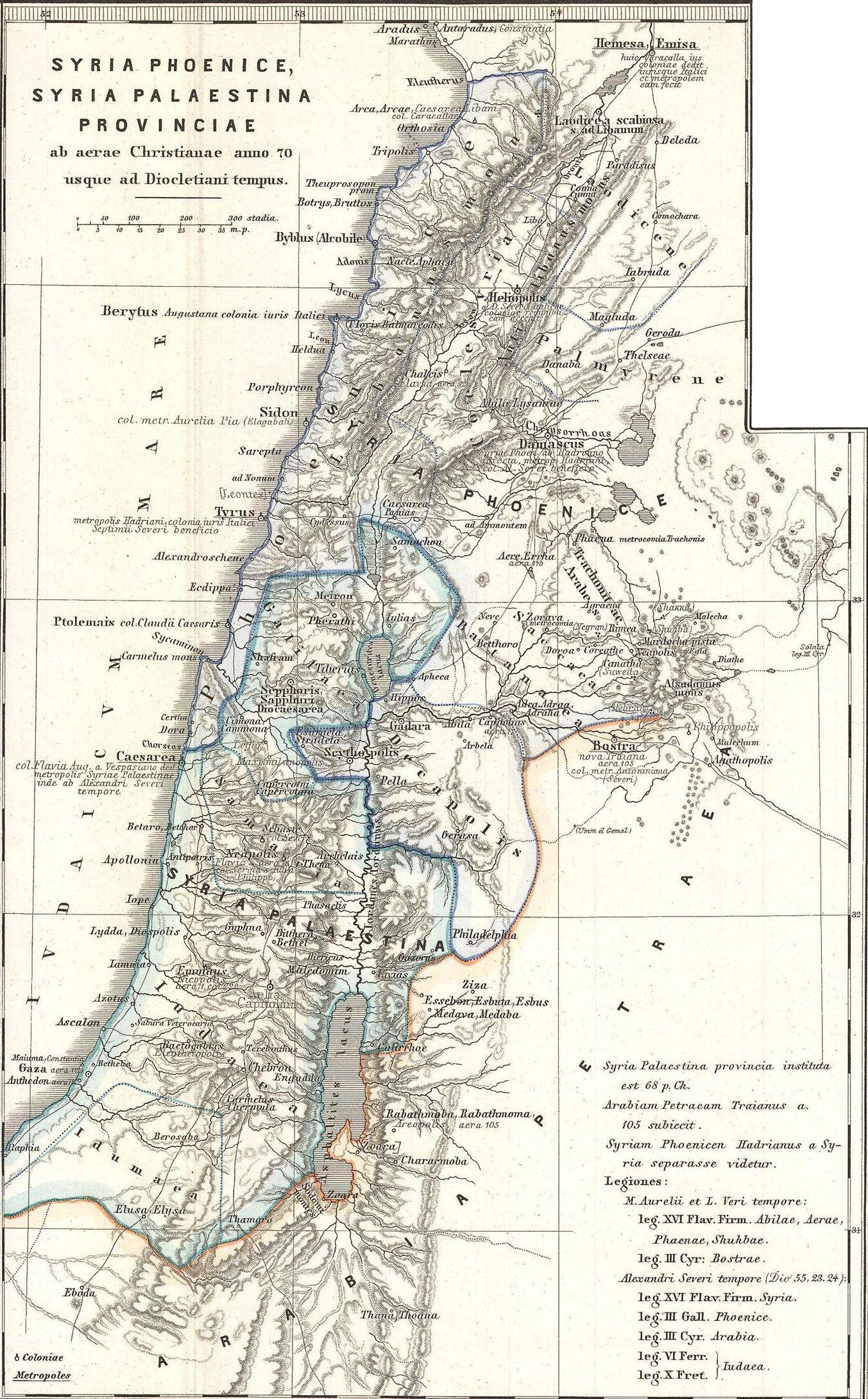

File:1873 Stieler Map of Asia Minor, Syria and Israel - Palestine (modern Turkey) - Geographicus - Klein-AsienSyrien-stieler-1873.jpg, An 1873 German map of Asia Minor & Syria, with relief illustrating the Beqaa (''El Bekaa'') valley

File:Baalbec. Panorama - Bonfils. LCCN93500455.jpg, Panorama, around 1870, by Félix Bonfils

File:Birdseye View of Baalbek and the Lebanons.jpg, Baalbek in 1910, after the arrival of rail

File:Baalbek. General view 04956r.jpg, The ruins of Baalbek facing west from the hexagonal forecourt in the 19th century

File:Colossal Hewn Block, Ancient Quarries Baalbek.jpg, The " Stone of the Pregnant Woman" in the early 20th century, the Temple of Jupiter in the background

volume I

volume II

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * & * * * * * * * * * * * Reprinted at Görlitz in 1591. * * * * * * *

Google Maps satellite view

* Panoramas of the temples a

an

Discover Lebanon

from the

GCatholic – Latin titular see

Baalbeck International Festival

(2006) at ''Al Mashriq'' {{Authority control Baalbek Tourist attractions in Lebanon World Heritage Sites in Lebanon Archaeological sites in Lebanon Great Rift Valley Phoenician sites in Lebanon Coloniae (Roman) Populated places established in the 7th millennium BC Roman sites in Lebanon Tourism in Lebanon Sunni Muslim communities in Lebanon Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Phoenician cities Roman towns and cities in Lebanon

Litani River

The Litani River (), the classical Leontes (), is an important water resource in southern Lebanon. The river rises in the fertile Beqaa Valley, west of Baalbek, and empties into the Mediterranean Sea north of Tyre. Exceeding in length, the ...

in Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

's Beqaa Valley

The Beqaa Valley (, ; Bekaa, Biqâ, Becaa) is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon and its most important farming region. Industry, especially the country's agricultural industry, also flourishes in Beqaa. The region broadly corresponds to th ...

, about northeast of Beirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

. It is the capital of Baalbek-Hermel Governorate. In 1998, the city had a population of 82,608. Most of the population consists of Shia Muslims

Shia Islam is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political Succession to Muhammad, successor (caliph) and as the spiritual le ...

, followed by Sunni Muslims and Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

; in 2017, there was also a large presence of Syrian refugees.

Baalbek has a history that dates back at least 11,000 years, encompassing significant periods such as Prehistoric

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use o ...

, Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

ite, Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

, and Roman eras. After Alexander the Great conquered the city in 334 BCE, he renamed it Heliopolis (, Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

for "Sun City"). The city flourished under Roman rule. However, it underwent transformations during the Christianization period and the subsequent rise of Islam following the Arab conquest in the 7th century. In later periods, the city was sacked by the Mongols

Mongols are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, China ( Inner Mongolia and other 11 autonomous territories), as well as the republics of Buryatia and Kalmykia in Russia. The Mongols are the principal member of the large family o ...

and faced a series of earthquakes, resulting in a decline in importance during the Ottoman and modern periods.

In the modern era, Baalbek enjoys economic advantages as a sought-after tourist destination. It is known for the ruins of the Roman temple complex, which includes the Temple of Bacchus and the Temple of Jupiter, and was inscribed in 1984 as a UNESCO World Heritage

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an international treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between sovereign states and/or international organizations that is governed by int ...

site. Other tourist attractions are the ''Great Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a membe ...

Mosque'', the Baalbek International Festival, the mausoleum of Sit Khawla, and a Roman quarry site named ''Hajar al-Hibla''. Baalbek's tourism sector has encountered challenges due to conflicts in Lebanon, particularly the 1975–1990 civil war, the ongoing Syrian civil war since 2011, and the Israel–Hezbollah conflict (2023–present).

Baalbek is considered to be part of Hezbollah

Hezbollah ( ; , , ) is a Lebanese Shia Islamist political party and paramilitary group. Hezbollah's paramilitary wing is the Jihad Council, and its political wing is the Loyalty to the Resistance Bloc party in the Lebanese Parliament. I ...

group's heartland and is known to be their political stronghold. During the Israeli occupation of Southern Lebanon

The Israeli occupation of Southern Lebanon lasted for eighteen years, from 1982 until 2000. In June 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon in response to attacks from southern Lebanon by Palestinian militants. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) occupied the ...

(1982–2000), the group managed to overpower the Lebanese army in Baalbek and gain control of the city. The settlement was subsequently used as a base to recruit and train men for attacks against Israeli forces. Hezbollah continues to hold significant political influence and popular support in Baalbek. In the 2022 Lebanese general election the Amal-Hezbollah list won 9 out of 10 seats in the Baalbek-Hermel Governorate.

Israel has conducted numerous airstrikes and raids against military and civilian targets in the Baalbek area in the past decades. For instance, in 2006 during the Operation Sharp and Smooth, Israeli commandos raided a hospital and bombed multiple houses, killing two Hezbollah fighters and at least eleven civilians. In 2024, during the Israel–Hezbollah conflict, Israel sent forced displacement

Forced displacement (also forced migration or forced relocation) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of perse ...

calls for the entire city. Shortly after, Israeli airstrikes killed 19 people, including 8 women.

Etymology

A few kilometres from the swamp from which the Litani (the classical Leontes) and the Asi (the upper Orontes) flow, Baalbek may be the same as the ''manbaa al-nahrayn'' ("Source of the Two Rivers"), the abode of El in theUgaritic

Ugaritic () is an extinct Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language known through the Ugaritic texts discovered by French archaeology, archaeologists in 1928 at Ugarit, including several major literary texts, notably the Baal cycl ...

Baal Cycle discovered in the 1920s and a separate serpent incantation.

Baalbek was called ''Heliopolis'' during the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, a latinisation of the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

''Hēlioúpolis'' () used during the Hellenistic period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

, meaning "Sun City" in reference to the solar cult there. The name is attested under the Seleucids

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great, ...

and Ptolemies. However, Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus, occasionally anglicized as Ammian ( Greek: Αμμιανός Μαρκελλίνος; born , died 400), was a Greek and Roman soldier and historian who wrote the penultimate major historical account surviving from antiquit ...

notes that earlier Assyrian names of Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

ine towns continued to be used alongside the official Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

ones imposed by the Diadochi

The Diadochi were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The Wars of the Diadochi mark the beginning of the Hellenistic period from the Mediterran ...

, who were successors of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

. In Greek religion, Helios

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Helios (; ; Homeric Greek: ) is the god who personification, personifies the Sun. His name is also Latinized as Helius, and he is often given the epithets Hyperion ("the one above") an ...

was both the sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

in the sky and its personification

Personification is the representation of a thing or abstraction as a person, often as an embodiment or incarnation. In the arts, many things are commonly personified, including: places, especially cities, National personification, countries, an ...

as a god

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

. The local Semitic god Baʿal Haddu was more often equated with Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

or Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

or simply called the "Great God of Heliopolis", but the name may refer to the Egyptians' association of Baʿal with their great god Ra. It was sometimes described as or Coelesyria ( or ') to distinguish it from its namesake in Egypt. In Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, its titular see

A titular see in various churches is an episcopal see of a former diocese that no longer functions, sometimes called a "dead diocese". The ordinary or hierarch of such a see may be styled a "titular metropolitan" (highest rank), "titular archbi ...

is distinguished as , from its former Roman province

The Roman provinces (, pl. ) were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as Roman g ...

Phoenice

Phoenice or Phoenike () was an ancient Greek city in Epirus and capital of the Chaonians.: "To the north the Chaonians had expelled the Corcyraeans from their holdings on the mainland and built fortifications at Buthrotum, Kalivo and Kara-Ali- ...

. The importance of the solar cult is also attested in the name ''Biḳāʿ al-ʿAzīz'' borne by the plateau surrounding Baalbek, as it references an earlier solar deity named Aziz. In Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and Roman antiquity, it was known as ''Heliopolis''. Some of the best-preserved Roman ruins in Lebanon are located here, including one of the largest temples of the Roman empire. The gods worshipped there (Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

, Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is often called Earth's "twin" or "sister" planet for having almost the same size and mass, and the closest orbit to Earth's. While both are rocky planets, Venus has an atmosphere much thicker ...

, and Bacchus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; ) is the god of wine-making, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, festivity, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, and theatre. He was also known as Bacchus ( or ; ) by the Gre ...

) were equivalents of the Canaanite deities Hadad

Hadad (), Haddad, Adad ( Akkadian: 𒀭𒅎 '' DIM'', pronounced as ''Adād''), or Iškur ( Sumerian) was the storm- and rain-god in the Canaanite and ancient Mesopotamian religions.

He was attested in Ebla as "Hadda" in c. 2500 BCE. From ...

, Atargatis. Local influences are seen in the planning and layout of the temples, which differ from classic Roman design.

The name appears in the Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; , from the verb ''šānā'', "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first written collection of the Jewish oral traditions that are known as the Oral Torah. Having been collected in the 3rd century CE, it is ...

, a second-century rabbinic text, as a kind of garlic

Garlic (''Allium sativum'') is a species of bulbous flowering plants in the genus '' Allium''. Its close relatives include the onion, shallot, leek, chives, Welsh onion, and Chinese onion. Garlic is native to central and south Asia, str ...

, ''shum ba'albeki'' (שום בעלבכי). It appears in two early 5th-century Syriac manuscripts, a translation of Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (30 May AD 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist from the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima. ...

's '' Theophania'' and a life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

of Rabbula, bishop of Edessa

Below is a list of bishops of Edessa.

Early bishops

The following list is based on the records of the ''Chronicle of Edessa'' (to ''c''.540) and the ''Chronicle of Zuqnin''.

Jacobite (Syriac) bishops

These bishops belonged to the Syriac Orthodo ...

. It was pronounced as Baʿlabakk () in Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic or Quranic Arabic () is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notably in Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphate, Abbasid literary texts such as poetry, e ...

. In Modern Standard Arabic

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) or Modern Written Arabic (MWA) is the variety of Standard language, standardized, Literary language, literary Arabic that developed in the Arab world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and in some usages al ...

, its vowels are marked as ''Baʿlabak'' () or ''Baʿlabekk''. It is ''Bʿalbik'' (, is ) in Lebanese Arabic

Lebanese Arabic ( ; autonym: ), or simply Lebanese ( ; autonym: ), is a Varieties of Arabic, variety of Levantine Arabic, indigenous to and primarily Languages of Lebanon, spoken in Lebanon, with significant linguistic influences borrowed from ...

.

The etymology

Etymology ( ) is the study of the origin and evolution of words—including their constituent units of sound and meaning—across time. In the 21st century a subfield within linguistics, etymology has become a more rigorously scientific study. ...

of Baalbek has been debated since the 18th century. Cook took it to mean " Baʿal (Lord) of the Beka" and Donne as "City of the Sun". Lendering asserts that it is probably a contraction of ''Baʿal Nebeq'' ("Lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage o ...

of the Source" of the Litani River

The Litani River (), the classical Leontes (), is an important water resource in southern Lebanon. The river rises in the fertile Beqaa Valley, west of Baalbek, and empties into the Mediterranean Sea north of Tyre. Exceeding in length, the ...

). Steiner proposes a Semitic adaption of "Lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage o ...

Bacchus", from the classical temple complex.

Nineteenth-century Biblical archaeologists

Biblical archaeology is an academic school and a subset of Biblical studies and Levantine archaeology. Biblical archaeology studies archaeological sites from the Ancient Near East and especially the Holy Land (also known as Land of Israel and ...

proposed the association of Baalbek with the town of Baalgad in the Book of Joshua

The Book of Joshua is the sixth book in the Hebrew Bible and the Old Testament, and is the first book of the Deuteronomistic history, the story of Israel from the conquest of Canaan to the Babylonian captivity, Babylonian exile. It tells of the ...

; the town of Baalath, one of Solomon

Solomon (), also called Jedidiah, was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible. The successor of his father David, he is described as having been the penultimate ...

's cities in the First Book of Kings; Baal-hamon, where Solomon had a vineyard

A vineyard ( , ) is a plantation of grape-bearing vines. Many vineyards exist for winemaking; others for the production of raisins, table grapes, and non-alcoholic grape juice. The science, practice and study of vineyard production is kno ...

; and the "Plain of Aven" in Book of Amos

The Book of Amos is the third of the Twelve Minor Prophets in the Christian Old Testament and Jewish Hebrew Bible, Tanakh and the second in the Greek Septuagint. The Book of Amos has nine chapters. According to the Bible, Amos (prophet), Amos was ...

.

History

Prehistory

The hilltop of Tell Baalbek, part of a valley to the east of the northernBeqaa Valley

The Beqaa Valley (, ; Bekaa, Biqâ, Becaa) is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon and its most important farming region. Industry, especially the country's agricultural industry, also flourishes in Beqaa. The region broadly corresponds to th ...

(), shows signs of almost continual habitation over the last 8–9000 years. It was well-watered both from a stream running from the ''Rās al-ʿAyn'' spring southwest of the citadel and, during the spring, from numerous rills formed by meltwater from the Anti-Lebanons. Macrobius

Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius, usually referred to as Macrobius (fl. AD 400), was a Roman provincial who lived during the early fifth century, during late antiquity, the period of time corresponding to the Later Roman Empire, and when Latin was ...

later credited the site's foundation to a colony of Egyptian

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of year ...

or Assyrian priests. The settlement's religious, commercial, and strategic importance was minor enough, however, that it is never mentioned in any known Assyrian or Egyptian

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of year ...

record, unless under another name. Its enviable position in a fertile valley, major watershed, and along the route from Tyre to Palmyra

Palmyra ( ; Palmyrene dialect, Palmyrene: (), romanized: ''Tadmor''; ) is an ancient city in central Syria. It is located in the eastern part of the Levant, and archaeological finds date back to the Neolithic period, and documents first menti ...

should have made it a wealthy and splendid site from an early age. During the Canaanite period, the local temples were primarily devoted to the Heliopolitan Triad: a male god ( Baʿal), his consort (Astarte

Astarte (; , ) is the Greek language, Hellenized form of the Religions of the ancient Near East, Ancient Near Eastern goddess ʿAṯtart. ʿAṯtart was the Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic equivalent of the East Semitic language ...

), and their son ( Adon). The site of the present Temple of Jupiter was probably the focus of earlier worship, as its altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religion, religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, Church (building), churches, and other places of worship. They are use ...

was located at the hill's precise summit and the rest of the sanctuary raised to its level.

In Islamic mythology

Islamic mythology is the body of myths associated with Islam and the Quran. Islam is a religion that is more concerned with social order and law than with religious rituals or myths. The primary focus of Islam is the practical and rational pra ...

, the temple complex was said to have been a palace of Solomon

Solomon (), also called Jedidiah, was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible. The successor of his father David, he is described as having been the penultimate ...

's which was put together by '' djinn'' and given as a wedding gift to the Queen of Sheba

The Queen of Sheba, also known as Bilqis in Arabic and as Makeda in Geʽez, is a figure first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. In the original story, she brings a caravan of valuable gifts for Solomon, the fourth King of Israel and Judah. This a ...

; its actual Roman origin remained obscured by the citadel's medieval fortifications as late as the 16th-century visit of the Polish prince Radziwiłł.

Antiquity

After

After Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

's conquest of Persia in the 330s BC, Baalbek (under its Hellenic name Heliopolis) formed part of the Diadochi

The Diadochi were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The Wars of the Diadochi mark the beginning of the Hellenistic period from the Mediterran ...

kingdoms of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

& Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

. It was annexed by the Romans during their eastern wars. The settlers of the Roman colony

A Roman (: ) was originally a settlement of Roman citizens, establishing a Roman outpost in federated or conquered territory, for the purpose of securing it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It ...

Colonia Julia Augusta Felix Heliopolitana may have arrived as early as the time of Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war. He ...

but were more probably the veterans

A veteran () is a person who has significant experience (and is usually adept and esteemed) and expertise in an job, occupation or Craft, field.

A military veteran is a person who is no longer serving in the military, armed forces.

A topic o ...

of the 5th and 8th Legions under Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

, during which time it hosted a Roman garrison. From 15 BC to AD 193, it formed part of the territory of Berytus

Berytus (; ; ; ; ), briefly known as Laodicea in Phoenicia (; ) or Laodicea in Canaan from the 2nd century to 64 BCE, was the ancient city of Beirut (in modern-day Lebanon) from the Roman Republic through the Roman Empire and late antiquity, Ear ...

. It is mentioned in Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

, Pliny, Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

, and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

, '' Geogr.''Bk. V, Ch. 15, §22

. and on

coins

A coin is a small object, usually round and flat, used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order to facilitate trade. They are most often issued by ...

of nearly every emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

from Nerva to Gallienus

Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus (; – September 268) was Roman emperor with his father Valerian from 253 to 260 and alone from 260 to 268. He ruled during the Crisis of the Third Century that nearly caused the collapse of the empire. He ...

. The 1st-century Pliny did not number it among the Decapolis, the "Ten Cities" of Coelesyria, while the 2nd-century Ptolemy did. The population likely varied seasonally with market fairs and the schedules of the Indian monsoon and caravans to the coast and interior.

During Classical Antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

, the city's temple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a place of worship, a building used for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. By convention, the specially built places of worship of some religions are commonly called "temples" in Engli ...

to Baʿal Haddu was conflated first with the worship of the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

sun god Helios

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Helios (; ; Homeric Greek: ) is the god who personification, personifies the Sun. His name is also Latinized as Helius, and he is often given the epithets Hyperion ("the one above") an ...

and then with the Greek and Roman sky god

The sky often has important religious significance. Many polytheism, polytheistic religions have deity, deities associated with the sky.

The daytime sky deities are typically distinct from the nighttime ones. Stith Thompson's ''Motif-Index o ...

under the name " Heliopolitan Zeus" or "Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

". The present Temple of Jupiter presumably replaced an earlier one using the same foundation; it was constructed during the mid- 1st century and probably completed around AD 60. His idol was a beardless golden god in the pose of a chariot

A chariot is a type of vehicle similar to a cart, driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid Propulsion, motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk O ...

eer, with a whip

A whip is a blunt weapon or implement used in a striking motion to create sound or pain. Whips can be used for flagellation against humans or animals to exert control through pain compliance or fear of pain, or be used as an audible cue thro ...

raised in his right hand and a thunderbolt and stalks of grain in his left; its image appeared on local coinage and it was borne through the streets during several festivals throughout the year. Macrobius

Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius, usually referred to as Macrobius (fl. AD 400), was a Roman provincial who lived during the early fifth century, during late antiquity, the period of time corresponding to the Later Roman Empire, and when Latin was ...

compared the rituals to those for Diva Fortuna at Antium

Antium was an Ancient history, ancient coastal town in Latium, south of Rome. An oppidum was founded by people of Latial culture (11th century BC or the beginning of the 1st millennium BC), then it was the main stronghold of the Volsci people unti ...

and says the bearers were the principal citizens of the town, who prepared for their role with abstinence, chastity, and shaved heads. In bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

statuary

A statue is a free-standing sculpture in which the realistic, full-length figures of persons or animals are carved or cast in a durable material such as wood, metal or stone. Typical statues are life-sized or close to life-size. A sculpture ...

attested from Byblos

Byblos ( ; ), also known as Jebeil, Jbeil or Jubayl (, Lebanese Arabic, locally ), is an ancient city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. The area is believed to have been first settled between 8800 and 7000BC and continuously inhabited ...

in Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

and Tortosa

Tortosa (, ) is the capital of the '' comarca'' of Baix Ebre, in Catalonia, Spain.

Tortosa is located at above sea level, by the Ebro river, protected on its northern side by the mountains of the Cardó Massif, of which Buinaca, one of the hi ...

in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, he was encased in a pillarlike term and surrounded (like the Greco- Persian Mithras

Mithraism, also known as the Mithraic mysteries or the Cult of Mithras, was a Roman Empire, Roman mystery religion focused on the god Mithras. Although inspired by Iranian peoples, Iranian worship of the Zoroastrian divinity (''yazata'') Mit ...

) by busts representing the sun, moon, and five known planets. In these statues, the bust of Mercury is made particularly prominent; a marble stela at Massilia in Transalpine Gaul

Gallia Narbonensis (Latin for "Gaul of Narbonne", from its chief settlement) was a Roman province located in Occitania (administrative region) , Occitania and Provence, in Southern France. It was also known as Provincia Nostra ("Our Prov ...

shows a similar arrangement but enlarges Mercury into a full figure. Local cults also revered the Baetylia, black conical stones considered sacred to Baʿal. One of these was taken to Rome by the emperor Elagabalus

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, 204 – 13 March 222), better known by his posthumous nicknames Elagabalus ( ) and Heliogabalus ( ), was Roman emperor from 218 to 222, while he was still a teenager. His short r ...

, a former priest "of the sun" at nearby Emesa, who erected a temple for it on the Palatine Hill

The Palatine Hill (; Classical Latin: ''Palatium''; Neo-Latin: ''Collis/Mons Palatinus''; ), which relative to the seven hills of Rome is the centremost, is one of the most ancient parts of the city; it has been called "the first nucleus of the ...

. Heliopolis was a noted oracle

An oracle is a person or thing considered to provide insight, wise counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. If done through occultic means, it is a form of divination.

Descript ...

and pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a travel, journey to a holy place, which can lead to a personal transformation, after which the pilgrim returns to their daily life. A pilgrim (from the Latin ''peregrinus'') is a traveler (literally one who has come from afar) w ...

site, whence the cult spread far afield, with inscriptions to the Heliopolitan god discovered in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a Roman province, province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, on the west by Noricum and upper Roman Italy, Italy, and on the southward by Dalmatia (Roman province), Dalmatia and upper Moesia. It ...

, Venetia, Gaul

Gaul () was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Roman people, Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of . Ac ...

, and near the Wall

A wall is a structure and a surface that defines an area; carries a load; provides security, shelter, or soundproofing; or serves a decorative purpose. There are various types of walls, including border barriers between countries, brick wal ...

in Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

. The Roman temple complex grew up from the early part of the reign of Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

in the late 1st century BC until the rise of Christianity in the 4th century. (The 6th-century chronicles of John Malalas of Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

, which claimed Baalbek as a " wonder of the world", credited most of the complex to the 2nd-century Antoninus Pius

Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius (; ; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from AD 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatorial family, Antoninus held var ...

, but it is uncertain how reliable his account is on the point.) By that time, the complex housed three temples on Tell Baalbek: one to Jupiter Heliopolitanus (Baʿal), one to Venus Heliopolitana (Ashtart), and a third to Bacchus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; ) is the god of wine-making, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, festivity, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, and theatre. He was also known as Bacchus ( or ; ) by the Gre ...

. On a nearby hill, a fourth temple was dedicated to the third figure of the Heliopolitan Triad, Mercury (Adon or Seimios). Ultimately, the site vied with Praeneste in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

as the two largest sanctuaries in the Western world.

The emperor Trajan

Trajan ( ; born Marcus Ulpius Traianus, 18 September 53) was a Roman emperor from AD 98 to 117, remembered as the second of the Five Good Emperors of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. He was a philanthropic ruler and a successful soldier ...

consulted the site's oracle

An oracle is a person or thing considered to provide insight, wise counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. If done through occultic means, it is a form of divination.

Descript ...

twice. The first time, he requested a written reply to his sealed and unopened question; he was favorably impressed by the god's blank reply as his own paper had been empty. He then inquired whether he would return alive from his wars against Parthia

Parthia ( ''Parθava''; ''Parθaw''; ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Medes during the 7th century BC, was incorporated into the subsequent Achaemeni ...

and received in reply a centurion

In the Roman army during classical antiquity, a centurion (; , . ; , or ), was a commander, nominally of a century (), a military unit originally consisting of 100 legionaries. The size of the century changed over time; from the 1st century BC ...

's vine staff, broken to pieces. In AD 193, Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; ; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through cursus honorum, the ...

granted the city ''ius Italicum

''Ius Italicum'' or ''ius italicum'' (Latin, Italian or Italic law) was a law in the early Roman Empire that allowed the emperors to grant cities outside Italy the legal fiction that they were on Italian soil. This meant that the city would be go ...

'' rights. His wife Julia Domna

Julia Domna (; – 217 AD) was Roman empress from 193 to 211 as the wife of Emperor Septimius Severus. She was the first empress of the Severan dynasty. Domna was born in Emesa (present-day Homs) in Roman Syria to an Arab family of priests ...

and son Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname Caracalla (; ), was Roman emperor from 198 to 217 AD, first serving as nominal co-emperor under his father and then r ...

toured Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

in AD 215; inscriptions in their honour at the site may date from that occasion; Julia was a Syrian native whose father had been an Emesan priest "of the sun" like Elagabalus

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, 204 – 13 March 222), better known by his posthumous nicknames Elagabalus ( ) and Heliogabalus ( ), was Roman emperor from 218 to 222, while he was still a teenager. His short r ...

.

The town became a battleground upon the rise of Christianity. Early Christian writers such as Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (30 May AD 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist from the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima. ...

(from nearby Caesarea) repeatedly execrated the practices of the local pagans in their worship of the Heliopolitan Venus. In AD 297, the actor Gelasinus converted in the middle of a scene mocking baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

; his public profession of faith provoked the audience to drag him from the theater and stone him to death. In the early 4th century, the deacon Cyril defaced many of the idols in Heliopolis; he was killed and (allegedly) cannibalised. Around the same time, Constantine, though not yet a Christian, demolished the goddess' temple, raised a basilica in its place, and outlawed the locals' ancient custom of prostituting women before marriage. Bar Hebraeus also credited him with ending the locals' continued practice of polygamy

Polygamy (from Late Greek , "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marriage, marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, it is called polygyny. When a woman is married to more tha ...

. The enraged locals responded by raping and torturing Christian virgins. They reacted violently again under the freedom permitted to them by Julian the Apostate

Julian (; ; 331 – 26 June 363) was the Caesar of the West from 355 to 360 and Roman emperor from 361 to 363, as well as a notable philosopher and author in Greek. His rejection of Christianity, and his promotion of Neoplatonic Hellenism ...

. The city was so noted for its hostility to the Christians that Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

ns were banished to it as a special punishment. The Temple of Jupiter, already greatly damaged by earthquakes, was demolished under Theodosius in 379 and replaced by another basilica (now lost), using stones scavenged from the pagan complex. The '' Easter Chronicle'' states he was also responsible for destroying all the lesser temples and shrines of the city. Around the year 400, Rabbula, the future bishop of Edessa

Below is a list of bishops of Edessa.

Early bishops

The following list is based on the records of the ''Chronicle of Edessa'' (to ''c''.540) and the ''Chronicle of Zuqnin''.

Jacobite (Syriac) bishops

These bishops belonged to the Syriac Orthodo ...

, attempted to have himself martyred by disrupting the pagans of Baalbek but was only thrown down the temple stairs along with his companion. It became the seat of its own bishop as well. Under the reign of Justinian

Justinian I (, ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign was marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovatio imperii'', or "restoration of the Empire". This ambition was ...

, eight of the complex's Corinthian columns were disassembled and shipped to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

for incorporation in the rebuilt Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia (; ; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque (; ), is a mosque and former Church (building), church serving as a major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The last of three church buildings to be successively ...

sometime between 532 and 537. Michael the Syrian claimed the golden idol of Heliopolitan Jupiter was still to be seen during the reign of Justin II (560s & 570s), and, up to the time of its conquest by the Muslims, it was renowned for its palaces, monuments, and gardens.

Middle Ages and early modernity

Baalbek was occupied by the Muslim army in AD 634 ( 13), in 636, or under Abu ʿUbaidah following theByzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

defeat at Yarmouk in 637 ( 16), either peacefully and by agreement or following a heroic defense and yielding of gold, of silver, 2000 silk vests, and 1000 swords. The ruined temple complex was fortified under the name ( " The Fortress") but was sacked with great violence by the Damascene caliph Marwan II in 748, at which time it was dismantled and largely depopulated. It formed part of the district of Damascus under the Umayyads and Abbasids

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 CE), from whom the dynasty takes i ...

before being conquered by Fatimid Egypt

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa and West Asia, it ...

in 942. In the mid-10th century, it was said to have "gates of palaces sculptured in marble and lofty columns also of marble" and that it was the most "stupendous" and "considerable" location in the whole of Syria. It was sacked and razed by the Byzantines under John I in 974, raided by Basil II in 1000, and occupied by Salih ibn Mirdas, emir

Emir (; ' (), also Romanization of Arabic, transliterated as amir, is a word of Arabic language, Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocratic, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person po ...

of Aleppo

Aleppo is a city in Syria, which serves as the capital of the Aleppo Governorate, the most populous Governorates of Syria, governorate of Syria. With an estimated population of 2,098,000 residents it is Syria's largest city by urban area, and ...

, in 1025.

In 1075, it was finally lost to the Fatimids on its conquest by Tutush I, Seljuk emir of Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

. It was briefly held by Muslim ibn Quraysh, emir of Aleppo

Aleppo is a city in Syria, which serves as the capital of the Aleppo Governorate, the most populous Governorates of Syria, governorate of Syria. With an estimated population of 2,098,000 residents it is Syria's largest city by urban area, and ...

, in 1083; after its recovery, it was ruled in the Seljuks' name by the eunuch Gümüshtegin until he was deposed for conspiring against the usurper Toghtekin

Zahir al-Din Toghtekin or Tughtekin (Modern ; Arabicised epithet: ''Zahir ad-Din Tughtikin''; died February 12, 1128), also spelled Tughtegin, was a Turkoman military leader, who was ''emir'' of Damascus from 1104 to 1128. He was the founder ...

in 1110. Toghtekin then gave the town to his son Buri. Upon Buri's succession to Damascus on his father's death in 1128, he granted the area to his son Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

. After Buri's murder, Muhammad successfully defended himself against the attacks of his brothers Ismaʿil and Mahmud and gave Baalbek to his vizier

A vizier (; ; ) is a high-ranking political advisor or Minister (government), minister in the Near East. The Abbasids, Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called ''katib'' (secretary), who was at first merely a help ...

Unur. In July 1139, Zengi, atabeg of Aleppo

Aleppo is a city in Syria, which serves as the capital of the Aleppo Governorate, the most populous Governorates of Syria, governorate of Syria. With an estimated population of 2,098,000 residents it is Syria's largest city by urban area, and ...

and stepfather of Mahmud, besieged Baalbek with 14 catapults. The outer city held until 10 October and the citadel until the 21st, when Unur surrendered upon a promise of safe passage. In December, Zengi negotiated with Muhammad, offering to trade Baalbek or Homs

Homs ( ; ), known in pre-Islamic times as Emesa ( ; ), is a city in western Syria and the capital of the Homs Governorate. It is Metres above sea level, above sea level and is located north of Damascus. Located on the Orontes River, Homs is ...

for Damascus, but Unur convinced the atabeg to refuse. Zengi strengthened its fortifications and bestowed the territory on his lieutenant Ayyub, father of Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

. Upon Zengi's assassination in 1146, Ayyub surrendered the territory to Unur, who was acting as regent for Muhammad's son Abaq. It was granted to the eunuch Ata al-Khadim, who also served as viceroy of Damascus.

In December 1151, it was raided by the garrison of Banyas as a reprisal for its role in a Turcoman raid on Banyas. Following Ata's murder, his nephew Dahhak, emir of the Wadi al-Taym, ruled Baalbek. He was forced to relinquish it to Nur ad-Din in 1154 after Ayyub had successfully intrigued against Abaq from his estates near Baalbek. Ayyub then administered the area from Damascus on Nur ad-Din's behalf. In the mid-12th century, Idrisi mentioned Baalbek's two temples and the legend of their origin under Solomon; it was visited by the Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

traveler Benjamin of Tudela

Benjamin of Tudela (), also known as Benjamin ben Jonah, was a medieval Jewish traveler who visited Europe, Asia, and Africa in the twelfth century. His vivid descriptions of western Asia preceded those of Marco Polo by a hundred years. With his ...

in 1170.

Baalbek's citadel served as a jail for Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding ...

taken by the Zengids as prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

. In 1171, these captives successfully overpowered their guards and took possession of the castle from its garrison. Muslims from the surrounding area gathered, however, and entered the castle through a secret passageway shown to them by a local. The Crusaders were then massacred.

Three major earthquakes occurred in the 12th century, in 1139, 1157, and 1170. The one in 1170 ruined Baalbek's walls and, though Nur ad-Din repaired them, his young heir Ismaʿil was made to yield it to Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

by a 4-month siege in 1174. Having taken control of Damascus on the invitation of its governor Ibn al-Muqaddam, Saladin rewarded him with the following the Ayyubid victory at the Horns of Hama in 1175. Baldwin, the young leper king of Jerusalem

The king or queen of Jerusalem was the supreme ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, a Crusader state founded in Jerusalem by the Latin Church, Latin Catholic leaders of the First Crusade, when the city was Siege of Jerusalem (1099), conquered in ...

, came of age the next year, ending the Crusaders' treaty with Saladin. His former regent, Raymond of Tripoli, raided the Beqaa Valley

The Beqaa Valley (, ; Bekaa, Biqâ, Becaa) is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon and its most important farming region. Industry, especially the country's agricultural industry, also flourishes in Beqaa. The region broadly corresponds to th ...

from the west in the summer, suffering a slight defeat at Ibn al-Muqaddam's hands. He was then joined by the main army, riding north under Baldwin and Humphrey of Toron; they defeated Saladin's elder brother Turan Shah in August at Ayn al-Jarr and plundered Baalbek. Upon the deposition of Turan Shah for neglecting his duties in Damascus, however, he demanded his childhood home of Baalbek as compensation. Ibn al-Muqaddam did not consent and Saladin opted to invest the city in late 1178 to maintain peace within his own family. An attempt to pledge fealty to the Christians at Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

was ignored on behalf of an existing treaty with Saladin. The siege was maintained peacefully through the snows of winter, with Saladin waiting for the "foolish" commander and his garrison of "ignorant scum" to come to terms. Sometime in spring, Ibn al-Muqaddam yielded and Saladin accepted his terms, granting him Baʿrin, Kafr Tab, and al-Maʿarra. The generosity quieted unrest among Saladin's vassals through the rest of his reign but led his enemies to attempt to take advantage of his presumed weakness. He did not permit Turan Shah to retain Baalbek very long, though, instructing him to lead the Egyptian troops returning home in 1179 and appointing him to a sinecure in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

. Baalbek was then granted to his nephew Farrukh Shah

Al-Malik al-Mansur Izz ad-Din Abu Sa'id Farrukhshah Dawud was the Kurds, Kurdish List of Ayyubid rulers#Emirs of Ba'albek, Ayyubid Emir of Baalbek between 1179 and 1182 and ''Na'ib'' (Viceroy) of Damascus.

Biography

Farrukh Shah was the son of ...

, whose family ruled it for the next half-century. When Farrukh Shah died three years later, his son Bahram Shah was only a child but he was permitted his inheritance and ruled til 1230. He was followed by al-Ashraf Musa, who was succeeded by his brother as-Salih Ismail, who received it in 1237 as compensation for being deprived of Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

by their brother al-Kamil

Al-Malik al-Kamil Nasir ad-Din Muhammad (; – 6 March 1238), titled Abu al-Maali (), was an Egyptian ruler and the fourth Ayyubid sultan of Egypt. During his tenure as sultan, the Ayyubids defeated the Fifth Crusade. He was known to the Franki ...

. It was seized in 1246 after a year of assaults by as-Salih Ayyub, who bestowed it upon Saʿd al-Din al-Humaidi. When as-Salih Ayyub's successor Turan Shah was murdered in 1250, al-Nasir Yusuf, the sultan of Aleppo, seized Damascus and demanded Baalbek's surrender. Instead, its emir did homage and agreed to regular payments of tribute.

The Mongolian general Kitbuqa took Baalbek in 1260 and dismantled its fortifications. Later in the same year, however, Qutuz, the sultan of Egypt

Sultan of Egypt was the status held by the rulers of Egypt after the establishment of the Ayyubid dynasty of Saladin in 1174 until the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517. Though the extent of the Egyptian Sultanate ebbed and flowed, it generally ...

, defeated the Mongols and placed Baalbek under the rule of their emir in Damascus. Most of the city's still-extant fine mosque and fortress architecture dates to the reign of the sultan Qalawun in the 1280s. By the early 14th century, Abulfeda the Hama

Hama ( ', ) is a city on the banks of the Orontes River in west-central Syria. It is located north of Damascus and north of Homs. It is the provincial capital of the Hama Governorate. With a population of 996,000 (2023 census), Hama is one o ...

thite was describing the city's "large and strong fortress". The revived settlement was again destroyed by a flood on 10 May 1318, when water from the east and northeast made holes wide in walls thick. 194 people were killed and 1500 houses, 131 shops, 44 orchards, 17 ovens, 11 mills, and 4 aqueducts were ruined, along with the town's mosque and 13 other religious and educational buildings. In 1400, Timur

Timur, also known as Tamerlane (1320s17/18 February 1405), was a Turco-Mongol conqueror who founded the Timurid Empire in and around modern-day Afghanistan, Iran, and Central Asia, becoming the first ruler of the Timurid dynasty. An undefeat ...

pillaged the town, and there was further destruction from a 1459 earthquake.

Early modernity

In 1516, Baalbek was conquered with the rest of Syria by the Ottoman sultan

In 1516, Baalbek was conquered with the rest of Syria by the Ottoman sultan Selim the Grim

Selim I (; ; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute (), was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite lasting only eight years, his reign is notable for the enormous expansion of ...

. In recognition of their prominence among the Shiites of the Beqaa Valley

The Beqaa Valley (, ; Bekaa, Biqâ, Becaa) is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon and its most important farming region. Industry, especially the country's agricultural industry, also flourishes in Beqaa. The region broadly corresponds to th ...

, the Ottomans awarded the sanjak of Homs and local ''iltizam

An iltizam () was a form of tax farm that appeared in the 15th century in the Ottoman Empire. The system began under Mehmed the Conqueror and was abolished during the Tanzimat reforms in 1856.

Iltizams were sold off by the government to wealthy n ...

'' concessions to Baalbek's Harfush family. Like the Hamadas, the Harfush emirs were involved on more than one occasion in the selection of Church officials and the running of local monasteries.Tradition holds that many Christians quit the Baalbek region in the eighteenth century for the newer, more secure town of

Zahlé

Zahlé () is a city in eastern Lebanon, and the capital and largest city of Beqaa Governorate, Lebanon. With around 150,000 inhabitants, it is the third-largest city in Lebanon after Beirut and Tripoli, Lebanon, Tripoli and the fourth-largest ...

on account of the Harfushes' oppression and rapacity, but more critical studies have questioned this interpretation, pointing out that the Harfushes were closely allied to the Orthodox Ma'luf family of Zahlé (where indeed Mustafa Harfush took refuge some years later) and showing that depredations from various quarters as well as Zahlé's growing commercial attractiveness accounted for Baalbek's decline in the eighteenth century. What repression there was did not always target the Christian community per se. The Shiite 'Usayran family, for example, is also said to have left Baalbek in this period to avoid expropriation by the Harfushes, establishing itself as one of the premier commercial households of Sidon

Sidon ( ) or better known as Saida ( ; ) is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located on the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coast in the South Governorate, Lebanon, South Governorate, of which it is the capital. Tyre, Lebanon, Tyre, t ...

and later even serving as consuls of Iran.

From the 16th century, European tourists began to visit the colossal and picturesque ruins. Donne hyperbolised "No ruins of antiquity have attracted more attention than those of Heliopolis, or been more frequently or accurately measured and described." Misunderstanding the temple of Bacchus as the "Temple of the Sun", they considered it the best-preserved Roman temple

Ancient Roman temples were among the most important buildings in culture of ancient Rome, Roman culture, and some of the richest buildings in Architecture of ancient Rome, Roman architecture, though only a few survive in any sort of complete ...

in the world. The Englishman Robert Wood's 1757 ''Ruins of Balbec'' included carefully measured engravings that proved influential on British and Continental Neoclassical architects. For example, details of the Temple of Bacchus's ceiling inspired a bed and ceiling by Robert Adam

Robert Adam (3 July 17283 March 1792) was a British neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer. He was the son of William Adam (architect), William Adam (1689–1748), Scotland's foremost architect of the time, and train ...

and its portico inspired that of St George's in Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London, part of the London Borough of Camden in England. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural institution, cultural, intellectual, and educational ...

.

During the 18th century, the western approaches were covered with attractive groves of walnut tree

Walnut trees are any species of tree in the plant genus ''Juglans'', the type genus of the family (biology), family Juglandaceae, the seeds of which are referred to as walnuts. All species are deciduous trees, tall, with pinnate leaves , with ...

s, but the town itself suffered badly during the 1759 earthquakes, after which it was held by the Metawali, who again feuded with other Lebanese tribes. Their power was broken by Jezzar Pasha, the rebel governor of Acre

The acre ( ) is a Unit of measurement, unit of land area used in the Imperial units, British imperial and the United States customary units#Area, United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one Chain (unit), ch ...

, in the last half of the 18th century. All the same, Baalbek remained no destination for a traveller unaccompanied by an armed guard. Upon the pasha's death in 1804, chaos ensued until Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt occupied the area in 1831, after which it again passed into the hands of the Harfushes. In 1835, the town's population was barely 200 people. In 1850, the Ottomans finally began direct administration of the area, making Baalbek a kaza

A kaza (, "judgment" or "jurisdiction") was an administrative divisions of the Ottoman Empire, administrative division of the Ottoman Empire. It is also discussed in English under the names district, subdistrict, and juridical district. Kazas co ...

under the Damascus Eyalet

Damascus Eyalet (; ) was an eyalet of the Ottoman Empire. Its reported area in the 19th century was . It became an eyalet after the Ottomans took it from the Mamluks following the 1516–1517 Ottoman–Mamluk War. By Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Alan ...

and its governor a kaymakam

Kaymakam, also known by #Names, many other romanizations, was a title used by various officials of the Ottoman Empire, including acting grand viziers, governors of provincial sanjaks, and administrators of district kazas. The title has been reta ...

.

Excavations

Emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

Wilhelm II of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and his wife passed through Baalbek on 1 November 1898, on their way to Jerusalem. He noted both the magnificence of the Roman remains and the drab condition of the modern settlement. It was expected at the time that natural disasters, winter frosts, and the raiding of building materials by the city's residents would shortly ruin the remaining ruins. The archaeological team he dispatched began work within a month. Despite finding nothing they could date prior to Baalbek's Roman occupation, Otto Puchstein and his associates worked until 1904 and produced a meticulously researched and thoroughly illustrated series of volumes. Later excavations under the Roman flagstones in the Great Court unearthed three skeletons and a fragment of Persian pottery dated to the 6th–4th centuries BC. The sherd

This page is a glossary of archaeology, the study of the human past from material remains.

A

B

C

D

E

F

...

featured cuneiform

Cuneiform is a Logogram, logo-Syllabary, syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform script ...

letters.

In 1977, Jean-Pierre Adam made a brief study suggesting most of the large blocks could have been moved on rollers with machine

A machine is a physical system that uses power to apply forces and control movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to natural biological macromol ...

s using capstans and pulley

Sheave without a rope

A pulley is a wheel on an axle or shaft enabling a taut cable or belt passing over the wheel to move and change direction, or transfer power between itself and a shaft.

A pulley may have a groove or grooves between flan ...

blocks, a process which he theorised could use 512 workers to move a block. "Baalbek, with its colossal structures, is one of the finest examples of Imperial Roman architecture at its apogee", UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

reported in making Baalbek a World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

in 1984. When the committee inscribed the site, it expressed the wish that the protected area include the entire town within the Arab walls, as well as the southwestern extramural quarter between Bastan-al-Khan, the Roman site and the Mameluk mosque of Ras-al-Ain. Lebanon's representative gave assurances that the committee's wish would be honoured. Recent cleaning operations at the Temple of Jupiter discovered the deep trench at its edge, whose study pushed back the date of Tell Baalbek's settlement to the PPNB Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

. Finds included pottery sherd

This page is a glossary of archaeology, the study of the human past from material remains.

A

B

C

D

E

F

...

s including a spout dating to the early Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

. In the summer of 2014, a team from the German Archaeological Institute

The German Archaeological Institute (, ''DAI'') is a research institute in the field of archaeology (and other related fields). The DAI is a "federal agency" under the Federal Foreign Office, Federal Foreign Office of Germany.

Status, tasks and ...

led by Jeanine Abdul Massih of the Lebanese University discovered a sixth, much larger stone suggested to be the world's largest ancient block. The stone was found underneath and next to the Stone of the Pregnant Woman ("Hajjar al-Hibla") and measures around . It is estimated to weigh .

Modern history

Baalbek was connected to the DHP, the French-owned railway concession inOttoman Syria

Ottoman Syria () is a historiographical term used to describe the group of divisions of the Ottoman Empire within the region of the Levant, usually defined as being east of the Mediterranean Sea, west of the Euphrates River, north of the Ara ...

, on 19 June 1902. It formed a station on the standard-gauge line between Riyaq to its south and Aleppo

Aleppo is a city in Syria, which serves as the capital of the Aleppo Governorate, the most populous Governorates of Syria, governorate of Syria. With an estimated population of 2,098,000 residents it is Syria's largest city by urban area, and ...

(now in Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

) to its north. This Aleppo Railway connected to the Beirut–Damascus Railway but—because that line was built to a 1.05-meter gauge—all traffic had to be unloaded and reloaded at Riyaq. Just before the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the population was still around 5000, about 2000 each of Sunnis and Shia

Shia Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political successor (caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community (imam). However, his right is understood ...

Mutawalis and 1000 Orthodox and Maronites

Maronites (; ) are a Syriac Christian ethnoreligious group native to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant (particularly Lebanon) whose members belong to the Maronite Church. The largest concentration has traditionally resided near Mount ...

. The French general Georges Catroux proclaimed the independence of Lebanon in 1941 but colonial rule continued until 1943. Baalbek still has its railway station but service has been discontinued since the 1970s, originally owing to the Lebanese Civil War