Asymmetric induction on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Asymmetric induction describes the preferential formation in a

Various chiral ligands have been developed to prepare chiral allylmetals for the reaction with aldehydes. H. C. Brown was the first to report the chiral allylboron reagents for asymmetric allylation reactions with aldehydes. The chiral allylboron reagents were synthesized from the natural product (+)-a-pinene in two steps. The TADDOL ligands developed by

Various chiral ligands have been developed to prepare chiral allylmetals for the reaction with aldehydes. H. C. Brown was the first to report the chiral allylboron reagents for asymmetric allylation reactions with aldehydes. The chiral allylboron reagents were synthesized from the natural product (+)-a-pinene in two steps. The TADDOL ligands developed by

The Evolution of Models for Carbonyl Addition

Evans Group Afternoon Seminar Sarah Siska February 9, 2001 {{Chiral synthesis Stereochemistry Induct

chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemistry, chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. When chemical reactions occur, the atoms are rearranged and the reaction is accompanied by an Gibbs free energy, ...

of one enantiomer

In chemistry, an enantiomer (Help:IPA/English, /ɪˈnænti.əmər, ɛ-, -oʊ-/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''ih-NAN-tee-ə-mər''), also known as an optical isomer, antipode, or optical antipode, is one of a pair of molecular entities whi ...

(enantioinduction) or diastereoisomer

In stereochemistry, diastereomers (sometimes called diastereoisomers) are a type of stereoisomer. Diastereomers are defined as non-mirror image, non-identical stereoisomers. Hence, they occur when two or more stereoisomers of a compound have dif ...

(diastereoinduction) over the other as a result of the influence of a chiral

Chirality () is a property of asymmetry important in several branches of science. The word ''chirality'' is derived from the Greek language, Greek (''kheir''), "hand", a familiar chiral object.

An object or a system is ''chiral'' if it is dist ...

feature present in the substrate

Substrate may refer to:

Physical layers

*Substrate (biology), the natural environment in which an organism lives, or the surface or medium on which an organism grows or is attached

** Substrate (aquatic environment), the earthy material that exi ...

, reagent

In chemistry, a reagent ( ) or analytical reagent is a substance or compound added to a system to cause a chemical reaction, or test if one occurs. The terms ''reactant'' and ''reagent'' are often used interchangeably, but reactant specifies a ...

, catalyst

Catalysis () is the increase in rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quick ...

or environment. Asymmetric induction is a key element in asymmetric synthesis

Enantioselective synthesis, also called asymmetric synthesis, is a form of chemical synthesis. It is defined by IUPAC as "a chemical reaction (or reaction sequence) in which one or more new elements of chirality are formed in a substrate molecul ...

.

Asymmetric induction was introduced by Hermann Emil Fischer

Hermann Emil Louis Fischer (; 9 October 1852 – 15 July 1919) was a German chemist and List of Nobel laureates in Chemistry, 1902 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He discovered the Fischer esterification. He also developed the Fisch ...

based on his work on carbohydrate

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ...

s. Several types of induction exist.

Internal asymmetric induction makes use of a chiral center bound to the reactive center through a covalent bond

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atom ...

and remains so during the reaction. The starting material is often derived from chiral pool synthesis. In relayed asymmetric induction the chiral information is introduced in a separate step and removed again in a separate chemical reaction. Special synthons are called chiral auxiliaries. In external asymmetric induction chiral information is introduced in the transition state

In chemistry, the transition state of a chemical reaction is a particular configuration along the reaction coordinate. It is defined as the state corresponding to the highest potential energy along this reaction coordinate. It is often marked w ...

through a catalyst

Catalysis () is the increase in rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quick ...

of chiral ligand. This method of asymmetric synthesis

Enantioselective synthesis, also called asymmetric synthesis, is a form of chemical synthesis. It is defined by IUPAC as "a chemical reaction (or reaction sequence) in which one or more new elements of chirality are formed in a substrate molecul ...

is economically most desirable.

Carbonyl 1,2 asymmetric induction

Several models exist to describe chiral induction at carbonyl carbons during nucleophilic additions. These models are based on a combination of steric and electronic considerations and are often in conflict with each other. Models have been devised by Cram (1952), Cornforth (1959), Felkin (1969) and others.Cram's rule

The Cram's rule of asymmetric induction named afterDonald J. Cram

Donald James Cram (April 22, 1919 – June 17, 2001) was an American chemist who shared the 1987 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Jean-Marie Lehn and Charles J. Pedersen "for their development and use of molecules with structure-specific interacti ...

states ''In certain non-catalytic reactions that diastereomer will predominate, which could be formed by the approach of the entering group from the least hindered side when the rotational conformation of the C-C bond is such that the double bond is flanked by the two least bulky groups attached to the adjacent asymmetric center.'' The rule indicates that the presence of an asymmetric center in a molecule induces the formation of an asymmetric center adjacent to it based on steric hindrance

Steric effects arise from the spatial arrangement of atoms. When atoms come close together there is generally a rise in the energy of the molecule. Steric effects are nonbonding interactions that influence the shape ( conformation) and reactivi ...

(''scheme 1'').

:

The experiments involved two reactions. In experiment one ''2-phenylpropionaldehyde'' (1, racemic

In chemistry, a racemic mixture or racemate () is a mixture that has equal amounts (50:50) of left- and right-handed enantiomers of a chiral molecule or salt. Racemic mixtures are rare in nature, but many compounds are produced industrially as r ...

but (R)-enantiomer shown) was reacted with the Grignard reagent

Grignard reagents or Grignard compounds are chemical compounds with the general formula , where X is a halogen and R is an organic group, normally an alkyl or aryl. Two typical examples are methylmagnesium chloride and phenylmagnesium bromi ...

of bromobenzene

Bromobenzene is an aryl bromide and the simplest of the bromobenzenes, consisting of a benzene ring substituted with one bromine atom. Its chemical formula is . It is a colourless liquid although older samples can appear yellow. It is a reagent ...

to ''1,2-diphenyl-1-propanol'' (2) as a mixture of diastereomer

In stereochemistry, diastereomers (sometimes called diastereoisomers) are a type of stereoisomer. Diastereomers are defined as non-mirror image, non-identical stereoisomers. Hence, they occur when two or more stereoisomers of a compound have di ...

s, predominantly the threo isomer

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formula – that is, the same number of atoms of each element (chemistry), element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. ''Isomerism'' refers to the exi ...

(see for explanation the Fischer projection

In chemistry, the Fischer projection, devised by Emil Fischer in 1891, is a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional organic molecule by projection. Fischer projections were originally proposed for the depiction of carbohydrates a ...

).

The preference for the formation of the threo isomer can be explained by the rule stated above by having the active nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are ...

in this reaction attacking the carbonyl group

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group with the formula , composed of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom, and it is divalent at the C atom. It is common to several classes of organic compounds (such as aldehydes ...

from the least hindered side (see Newman projection

A Newman projection is a drawing that helps visualize the 3-dimensional structure of a molecule. This projection most commonly sights down a carbon-carbon bond, making it a very useful way to visualize the stereochemistry of alkanes. A Newman pro ...

A) when the carbonyl is positioned in a staggered formation with the methyl

In organic chemistry, a methyl group is an alkyl derived from methane, containing one carbon atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms, having chemical formula (whereas normal methane has the formula ). In formulas, the group is often abbreviated as ...

group and the hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

atom, which are the two smallest substituent

In organic chemistry, a substituent is one or a group of atoms that replaces (one or more) atoms, thereby becoming a moiety in the resultant (new) molecule.

The suffix ''-yl'' is used when naming organic compounds that contain a single bond r ...

s creating a minimum of steric hindrance

Steric effects arise from the spatial arrangement of atoms. When atoms come close together there is generally a rise in the energy of the molecule. Steric effects are nonbonding interactions that influence the shape ( conformation) and reactivi ...

, in a gauche orientation and phenyl

In organic chemistry, the phenyl group, or phenyl ring, is a cyclic group of atoms with the formula , and is often represented by the symbol Ph (archaically φ) or Ø. The phenyl group is closely related to benzene and can be viewed as a benzene ...

as the most bulky group in the anti conformation

In chemistry, rotamers are chemical species that differ from one another primarily due to rotations about one or more single bonds. Various arrangements of atoms in a molecule that differ by rotation about single bonds can also be referred to as ...

.

The second reaction is the organic reduction

Organic reductions or organic oxidations or organic redox reactions are redox reactions that take place with organic compounds. In organic chemistry oxidations and reductions are different from ordinary redox reactions, because many reactions car ...

of ''1,2-diphenyl-1-propanone'' 2 with lithium aluminium hydride

Lithium aluminium hydride, commonly abbreviated to LAH, is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula or . It is a white solid, discovered by Finholt, Bond and Schlesinger in 1947. This compound is used as a reducing agent in organic synthe ...

, which results in the same reaction product as above but now with preference for the erythro isomer (2a). Now a hydride

In chemistry, a hydride is formally the anion of hydrogen (H−), a hydrogen ion with two electrons. In modern usage, this is typically only used for ionic bonds, but it is sometimes (and has been more frequently in the past) applied to all che ...

anion (H−) is the nucleophile attacking from the least hindered side (imagine hydrogen entering from the paper plane).

Felkin model

The Felkin model (1968) named after Hugh Felkin also predicts thestereochemistry

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, studies the spatial arrangement of atoms that form the structure of molecules and their manipulation. The study of stereochemistry focuses on the relationships between stereoisomers, which are defined ...

of nucleophilic addition

In organic chemistry, a nucleophilic addition (AN) reaction is an addition reaction where a chemical compound with an electrophilic double or triple bond reacts with a nucleophile, such that the double or triple bond is broken. Nucleophilic addit ...

reactions to carbonyl

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group with the formula , composed of a carbon atom double bond, double-bonded to an oxygen atom, and it is divalent at the C atom. It is common to several classes of organic compounds (such a ...

groups. Felkin argued that the Cram model suffered a major drawback: an eclipsed conformation in the transition state

In chemistry, the transition state of a chemical reaction is a particular configuration along the reaction coordinate. It is defined as the state corresponding to the highest potential energy along this reaction coordinate. It is often marked w ...

between the carbonyl substituent (the hydrogen atom in aldehydes) and the largest α-carbonyl substituent. He demonstrated that by increasing the steric bulk of the carbonyl substituent from methyl

In organic chemistry, a methyl group is an alkyl derived from methane, containing one carbon atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms, having chemical formula (whereas normal methane has the formula ). In formulas, the group is often abbreviated as ...

to ethyl to isopropyl

In organic chemistry, a propyl group is a three-carbon alkyl substituent with chemical formula for the linear form. This substituent form is obtained by removing one hydrogen atom attached to the terminal carbon of propane. A propyl substituent ...

to tert-butyl

In organic chemistry, butyl is a four-carbon alkyl radical or substituent group with general chemical formula , derived from either of the two isomers (''n''-butane and isobutane) of butane.

The isomer ''n''-butane can connect in two ways, giv ...

, the stereoselectivity

In chemistry, stereoselectivity is the property of a chemical reaction in which a single reactant forms an unequal mixture of stereoisomers during a non- stereospecific creation of a new stereocenter or during a non-stereospecific transformation ...

also increased, which is not predicted by Cram's rule:

:

The Felkin rules are:

* The transition state

In chemistry, the transition state of a chemical reaction is a particular configuration along the reaction coordinate. It is defined as the state corresponding to the highest potential energy along this reaction coordinate. It is often marked w ...

s are reactant-like.

* Torsional strain (Pitzer strain) involving partial bonds (in transition states) represents a substantial fraction of the strain between fully formed bonds, even when the degree of bonding is quite low. The conformation in the TS is staggered and not eclipsed with the substituent R skew with respect to two adjacent groups one of them the smallest in TS A.

:

: For comparison TS B is the Cram transition state.

* The main steric interactions involve those around R and the nucleophile but not the carbonyl oxygen atom.

* Attack of the nucleophile occurs according to the Dunitz angle (107 degrees), eclipsing the hydrogen, rather than perpendicular to the carbonyl.

* A polar effect or electronic effect stabilizes a transition state with maximum separation between the nucleophile and an electron-withdrawing group

An electron-withdrawing group (EWG) is a Functional group, group or atom that has the ability to draw electron density toward itself and away from other adjacent atoms. This electron density transfer is often achieved by resonance or inductive effe ...

. For instance haloketones do not obey Cram's rule, and, in the example above, replacing the electron-withdrawing phenyl

In organic chemistry, the phenyl group, or phenyl ring, is a cyclic group of atoms with the formula , and is often represented by the symbol Ph (archaically φ) or Ø. The phenyl group is closely related to benzene and can be viewed as a benzene ...

group by a cyclohexyl

Cyclohexane is a cycloalkane with the molecular formula . Cyclohexane is non-polar. Cyclohexane is a colourless, flammable liquid with a distinctive detergent-like odor, reminiscent of cleaning products (in which it is sometimes used). Cyclo ...

group reduces stereoselectivity considerably.

Felkin–Anh model

The Felkin–Anh model is an extension of the Felkin model that incorporates improvements suggested by Nguyễn Trọng Anh and Odile Eisenstein to correct for two key weaknesses in Felkin's model. The first weakness addressed was the statement by Felkin of a strong polar effect in nucleophilic addition transition states, which leads to the complete inversion of stereochemistry by SN2 reactions, without offering justifications as to why this phenomenon was observed. Anh's solution was to offer the antiperiplanar effect as a consequence of asymmetric induction being controlled by both substituent and orbital effects.Anh, N. T.; Eisenstein, ''O. Nouv. J. Chim.'' 1977, ''1'', 61. In this effect, the best nucleophile acceptor σ* orbital is aligned parallel to both the π and π* orbitals of the carbonyl, which provide stabilization of the incoming anion. The second weakness in the Felkin Model was the assumption of substituent minimization around the carbonyl R, which cannot be applied to aldehydes. Incorporation of Bürgi–Dunitz angle ideas allowed Anh to postulate a non-perpendicular attack by the nucleophile on the carbonyl center, anywhere from 95° to 105° relative to the oxygen-carbon double bond, favoring approach closer to the smaller substituent and thereby solve the problem of predictability for aldehydes.Anti–Felkin selectivity

Though the Cram and Felkin–Anh models differ in theconformers

In chemistry, rotamers are chemical species that differ from one another primarily due to rotations about one or more single bonds. Various arrangements of atoms in a molecule that differ by rotation about single bonds can also be referred to as ...

considered and other assumptions, they both attempt to explain the same basic phenomenon: the preferential addition of a nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are ...

to the most sterically favored face of a carbonyl

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group with the formula , composed of a carbon atom double bond, double-bonded to an oxygen atom, and it is divalent at the C atom. It is common to several classes of organic compounds (such a ...

moiety. However, many examples exist of reactions that display stereoselectivity opposite of what is predicted by the basic tenets of the Cram and Felkin–Anh models. Although both of the models include attempts to explain these reversals, the products obtained are still referred to as "anti-Felkin" products. One of the most common examples of altered asymmetric induction selectivity requires an α-carbon substituted with a component with Lewis base

A Lewis acid (named for the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis) is a chemical species that contains an empty orbital which is capable of accepting an electron pair from a Lewis base to form a Lewis adduct. A Lewis base, then, is any sp ...

character (i.e. O, N, S, P substituents). In this situation, if a Lewis acid

A Lewis acid (named for the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis) is a chemical species that contains an empty orbital which is capable of accepting an electron pair from a Lewis base to form a Lewis adduct. A Lewis base, then, is any ...

such as Al-iPr2 or Zn2+ is introduced, a bidentate chelation

Chelation () is a type of bonding of ions and their molecules to metal ions. It involves the formation or presence of two or more separate coordinate bonds between a polydentate (multiple bonded) ligand and a single central metal atom. These l ...

effect can be observed. This locks the carbonyl

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group with the formula , composed of a carbon atom double bond, double-bonded to an oxygen atom, and it is divalent at the C atom. It is common to several classes of organic compounds (such a ...

and the Lewis base

A Lewis acid (named for the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis) is a chemical species that contains an empty orbital which is capable of accepting an electron pair from a Lewis base to form a Lewis adduct. A Lewis base, then, is any sp ...

substituent in an eclipsed conformation, and the nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are ...

will then attack from the side with the smallest free α-carbon substituent. If the chelating R group is identified as the largest, this will result in an "anti-Felkin" product.

This stereoselective control was recognized and discussed in the first paper establishing the Cram model, causing Cram to assert that his model requires non-chelating conditions. An example of chelation

Chelation () is a type of bonding of ions and their molecules to metal ions. It involves the formation or presence of two or more separate coordinate bonds between a polydentate (multiple bonded) ligand and a single central metal atom. These l ...

control of a reaction can be seen here, from a 1987 paper that was the first to directly observe such a "Cram-chelate" intermediate, vindicating the model:

Here, the methyl titanium chloride forms a Cram-chelate. The methyl group then dissociates from titanium

Titanium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ti and atomic number 22. Found in nature only as an oxide, it can be reduced to produce a lustrous transition metal with a silver color, low density, and high strength, resistant to corrosion in ...

and attacks the carbonyl, leading to the anti-Felkin diastereomer.

A non-chelating electron-withdrawing substituent effect can also result in anti-Felkin selectivity. If a substituent on the α-carbon is sufficiently electron withdrawing, the nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are ...

will add ''anti-'' relative to the electron withdrawing group

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up and down quarks.

E ...

, even if the substituent is not the largest of the 3 bonded to the α-carbon. Each model offers a slightly different explanation for this phenomenon. A polar effect was postulated by the Cornforth model and the original Felkin model, which placed the EWG substituent and incoming nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are ...

''anti''- to each other in order to most effectively cancel the dipole moment of the transition structure.

This Newman projection

A Newman projection is a drawing that helps visualize the 3-dimensional structure of a molecule. This projection most commonly sights down a carbon-carbon bond, making it a very useful way to visualize the stereochemistry of alkanes. A Newman pro ...

illustrates the Cornforth and Felkin transition state

In chemistry, the transition state of a chemical reaction is a particular configuration along the reaction coordinate. It is defined as the state corresponding to the highest potential energy along this reaction coordinate. It is often marked w ...

that places the EWG ''anti-'' to the incoming nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are ...

, regardless of its steric bulk relative to RS and RL.

The improved Felkin–Anh model, as discussed above, makes a more sophisticated assessment of the polar effect by considering molecular orbital

In chemistry, a molecular orbital is a mathematical function describing the location and wave-like behavior of an electron in a molecule. This function can be used to calculate chemical and physical properties such as the probability of finding ...

interactions in the stabilization of the preferred transition state. A typical reaction illustrating the potential anti-Felkin selectivity of this effect, along with its proposed transition structure, is pictured below:

Carbonyl 1,3 asymmetric induction

It has been observed that the stereoelectronic environment at the β-carbon of can also direct asymmetric induction. A number of predictive models have evolved over the years to define the stereoselectivity of such reactions.Chelation model

According to Reetz, the Cram-chelate model for 1,2-inductions can be extended to predict the chelated complex of a β-alkoxy aldehyde and metal. The nucleophile is seen to attack from the less sterically hindered side and ''anti-'' to the substituent Rβ, leading to the ''anti-''adduct as the major product. To make such chelates, the metal center must have at least two free coordination sites and the protecting ligands should form a bidentate complex with the Lewis acid.Non-chelation model

Cram–Reetz model

Cram and Reetz demonstrated that 1,3-stereocontrol is possible if the reaction proceeds through an acyclic transition state. The reaction of β-alkoxy aldehyde with allyltrimethylsilane showed good selectivity for the ''anti-''1,3-diol, which was explained by the Cram polar model. The polar benzyloxy group is oriented anti to the carbonyl to minimize dipole interactions and the nucleophile attacks ''anti-'' to the bulkier (RM) of the remaining two substituents.Evans model

More recently, Evans presented a different model for nonchelate 1,3-inductions. In the proposed transition state, the β-stereocenter is oriented ''anti-'' to the incoming nucleophile, as seen in the Felkin–Anh model. The polar X group at the β-stereocenter is placed ''anti-'' to the carbonyl to reduce dipole interactions, and Rβ is placed ''anti-'' to the aldehyde group to minimize the steric hindrance. Consequently, the 1,3-''anti''-diol would be predicted as the major product.Carbonyl 1,2 and 1,3 asymmetric induction

If the substrate has both an α- and β-stereocenter, the Felkin–Anh rule (1,2-induction) and the Evans model (1,3-induction) should considered at the same time. If these two stereocenters have an ''anti-'' relationship, both models predict the same diastereomer (the stereoreinforcing case). However, in the case of the syn-substrate, the Felkin–Anh and the Evans model predict different products (non-stereoreinforcing case). It has been found that the size of the incoming nucleophile determines the type of control exerted over the stereochemistry. In the case of a large nucleophile, the interaction of the α-stereocenter with the incoming nucleophile becomes dominant; therefore, the Felkin product is the major one. Smaller nucleophiles, on the other hand, result in 1,3 control determining the asymmetry.Acyclic alkenes asymmetric induction

Chiral acyclic alkenes also showdiastereoselectivity

In stereochemistry, diastereomers (sometimes called diastereoisomers) are a type of stereoisomer. Diastereomers are defined as non-mirror image, non-identical stereoisomers. Hence, they occur when two or more stereoisomers of a compound have d ...

upon reactions such as epoxidation

In organic chemistry, an epoxide is a cyclic ether, where the ether forms a three-atom ring: two atoms of carbon and one atom of oxygen. This triangular structure has substantial ring strain, making epoxides highly reactive, more so than other ...

and enolate alkylation. The substituents around the alkene can favour the approach of the electrophile

In chemistry, an electrophile is a chemical species that forms bonds with nucleophiles by accepting an electron pair. Because electrophiles accept electrons, they are Lewis acids. Most electrophiles are positively Electric charge, charged, have an ...

from one or the other face of the molecule. This is the basis of the Houk's model, based on theoretical work by Kendall Houk, which predicts that the selectivity is stronger for ''cis'' than for ''trans'' double bonds.

:

In the example shown, the ''cis'' alkene assumes the shown conformation to minimize steric clash between RS and the methyl group. The approach of the electrophile preferentially occurs from the same side of the medium group (RM) rather than the large group (RL), mainly producing the shown diastereoisomer. Since for a ''trans'' alkene the steric hindrance between RS and the H group is not as large as for the ''cis'' case, the selectivity is much lower.

Substrate control: asymmetric induction by molecular framework in acyclic systems

Asymmetric induction by the molecular framework of an acyclic substrate is the idea that asymmetricsteric

Steric effects arise from the spatial arrangement of atoms. When atoms come close together there is generally a rise in the energy of the molecule. Steric effects are nonbonding interactions that influence the shape ( conformation) and reactivi ...

and electronic properties of a molecule may determine the chirality of subsequent chemical reactions on that molecule. This principal is used to design chemical syntheses where one stereocentre is in place and additional stereocentres are required.

When considering how two functional groups

In organic chemistry, a functional group is any substituent or moiety (chemistry), moiety in a molecule that causes the molecule's characteristic chemical reactions. The same functional group will undergo the same or similar chemical reactions r ...

or species react, the precise 3D configurations of the chemical entities involved will determine how they may approach one another. Any restrictions as to how these species may approach each other will determine the configuration of the product of the reaction. In the case of asymmetric induction, we are considering the effects of one asymmetric centre on a molecule on the reactivity of other functional groups on that molecule. The closer together these two sites are, the larger an influence is expected to be observed. A more holistic approach to evaluating these factors is by computational modelling, however, simple qualitative factors may also be used to explain the predominant trends seen for some synthetic steps. The ease and accuracy of this qualitative approach means it is more commonly applied in synthesis and substrate design. Examples of appropriate molecular frameworks are alpha chiral aldehydes and the use of chiral auxiliaries.

Asymmetric induction at alpha-chiral aldehydes

Possible reactivity at aldehydes includenucleophilic attack

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they a ...

and addition of allylmetals. The stereoselectivity of nucleophilic attack at alpha-chiral aldehydes may be described by the Felkin–Anh or polar Felkin Anh models and addition of achiral allylmetals may be described by Cram’s rule.

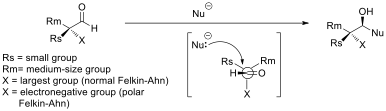

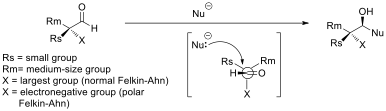

Felkin–Anh and polar Felkin–Anh model

Selectivity in nucleophilic additions to chiral aldehydes is often explained by the Felkin–Anh model (see figure). The nucleophile approaches the carbon of the carbonyl group at the Burgi-Dunitz angle. At this trajectory, attack from the bottom face is disfavored due to steric bulk of the adjacent, large, functional group. The polar Felkin–Anh model is applied in the scenario where X is an electronegative group. The polar Felkin–Anh model postulates that the observed stereochemistry arises due to hyperconjugative stabilization arising from the anti-periplanar interaction between the C-X antibonding σ* orbital and the forming bond. Improving Felkin–Anh selectivity for organometal additions to aldehydes can be achieved by using organo-aluminum nucleophiles instead of the corresponding Grignard or organolithium nucleophiles. Claude Spino and co-workers have demonstrated significant stereoselectivity improvements upon switching from vinylgrignard to vinylalane reagents with a number of chiral aldehydes.Cram’s rule

Addition of achiral allylmetals toaldehydes

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () (lat. ''al''cohol ''dehyd''rogenatum, dehydrogenated alcohol) is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred ...

forms a chiral alcohol, the stereochemical outcome of this reaction is determined by the chirality of the α-carbon

In the nomenclature of organic chemistry, a locant is a term to indicate the position of a functional group or substituent within a molecule.

Numeric locants

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) recommends the use of n ...

on the aldehyde substrate (Figure "Substrate control: addition of achiral allylmetals to α-chiral aldehydes"). The allylmetal reagents used include boron

Boron is a chemical element; it has symbol B and atomic number 5. In its crystalline form it is a brittle, dark, lustrous metalloid; in its amorphous form it is a brown powder. As the lightest element of the boron group it has three ...

, tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

and titanium

Titanium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ti and atomic number 22. Found in nature only as an oxide, it can be reduced to produce a lustrous transition metal with a silver color, low density, and high strength, resistant to corrosion in ...

.

Cram’s rule explains the stereoselectivity by considering the transition state depicted in figure 3. In the transition state the oxygen lone pair is able to interact with the boron centre whilst the allyl group is able to add to the carbon end of the carbonyl group. The steric demand of this transition state is minimized by the α-carbon configuration holding the largest group away from (trans to) the congested carbonyl group and the allylmetal group approaching past the smallest group on the α-carbon centre. In the example below (Figure "An example of substrate controlled addition of achiral allyl-boron to α-chiral aldehyde"), (R)-2-methylbutanal (1) reacts with the allylboron reagent (2) with two possible diastereomers of which the (R, R)-isomer is the major product. The Cram model of this reaction is shown with the carbonyl group placed trans to the ethyl group (the large group) and the allyl boron approaching past the hydrogen (the small group). The structure is shown in Newman projection

A Newman projection is a drawing that helps visualize the 3-dimensional structure of a molecule. This projection most commonly sights down a carbon-carbon bond, making it a very useful way to visualize the stereochemistry of alkanes. A Newman pro ...

. In this case the nucleophilic addition

In organic chemistry, a nucleophilic addition (AN) reaction is an addition reaction where a chemical compound with an electrophilic double or triple bond reacts with a nucleophile, such that the double or triple bond is broken. Nucleophilic addit ...

reaction happens at the face where the hydrogen (the small group) is, producing the (R, R)-isomer as the major product.

Chiral auxiliaries

Asymmetric stereoinduction can be achieved with the use of chiral auxiliaries. Chiral auxiliaries may be reversibly attached to the substrate, inducing a diastereoselective reaction prior to cleavage, overall producing an enantioselective process. Examples of chiral auxiliaries include, Evans’ chiral oxazolidinone auxiliaries (for asymmetric aldol reactions) pseudoephedrine amides and tert-butanesulfinamide imines.Substrate control: asymmetric induction by molecular framework in cyclic systems

Cyclic molecule

A cyclic compound (or ring compound) is a term for a compound in the field of chemistry in which one or more series of atoms in the compound is connected to form a ring. Rings may vary in size from three to many atoms, and include examples where ...

s often exist in much more rigid conformations than their linear counterparts. Even very large macrocycle

Macrocycles are often described as molecules and ions containing a ring of twelve or more atoms. Classical examples include the crown ethers, calixarenes, porphyrins, and cyclodextrins. Macrocycles describe a large, mature area of chemistry. ...

s like erythromycin

Erythromycin is an antibiotic used for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. This includes respiratory tract infections, skin infections, chlamydia infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, and syphilis. It may also be used ...

exist in defined geometries despite having many degrees of freedom. Because of these properties, it is often easier to achieve asymmetric induction with macrocyclic substrates rather than linear ones. Early experiments performed by W. Clark Still and colleagues showed that medium- and large-ring organic molecules can provide striking levels of stereo induction as substrates in reactions such as kinetic enolate

In organic chemistry, enolates are organic anions derived from the deprotonation of carbonyl () compounds. Rarely isolated, they are widely used as reagents in the Organic synthesis, synthesis of organic compounds.

Bonding and structure

Enolate ...

alkylation Alkylation is a chemical reaction that entails transfer of an alkyl group. The alkyl group may be transferred as an alkyl carbocation, a free radical, a carbanion, or a carbene (or their equivalents). Alkylating agents are reagents for effecting al ...

, dimethylcuprate addition, and catalytic hydrogenation

Hydrogenation is a chemical reaction between molecular hydrogen (H2) and another compound or element, usually in the presence of a catalyst such as nickel, palladium or platinum. The process is commonly employed to redox, reduce or Saturated ...

. Even a single methyl group is often sufficient to bias the diastereomeric outcome of the reaction. These studies, among others, helped challenge the widely-held scientific belief that large rings are too floppy to provide any kind of stereochemical control.

A number of total syntheses have made use of macrocyclic stereocontrol to achieve desired reaction products. In the synthesis of (−)-cladiella-6,11-dien-3-ol, a strained trisubstituted olefin

In organic chemistry, an alkene, or olefin, is a hydrocarbon containing a carbon–carbon double bond. The double bond may be internal or at the terminal position. Terminal alkenes are also known as α-olefins.

The International Union of Pu ...

was dihydroxylated diasetereoselectively with ''N''-methylmorpholine ''N''-oxide (NMO) and osmium tetroxide

Osmium tetroxide (also osmium(VIII) oxide) is the chemical compound with the formula OsO4. The compound is noteworthy for its many uses, despite its toxicity and the rarity of osmium. It also has a number of unusual properties, one being that the ...

, in the presence of an unstrained olefin. En route to (±)-periplanone B, chemists achieved a facial selective epoxidation of an enone intermediate using tert-butyl hydroperoxide in the presence of two other alkenes. Sodium borohydride

Sodium borohydride, also known as sodium tetrahydridoborate and sodium tetrahydroborate, is an inorganic compound with the formula (sometimes written as ). It is a white crystalline solid, usually encountered as an aqueous basic solution. Sodi ...

reduction of a 10-membered ring enone intermediate en route to the sesquiterpene

Sesquiterpenes are a class of terpenes that consist of three isoprene units and often have the molecular formula C15H24. Like monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes may be cyclic or contain rings, including many combinations. Biochemical modifications s ...

eucannabinolide proceeded as predicted by molecular modelling calculations that accounted for the lowest energy macrocycle

Macrocycles are often described as molecules and ions containing a ring of twelve or more atoms. Classical examples include the crown ethers, calixarenes, porphyrins, and cyclodextrins. Macrocycles describe a large, mature area of chemistry. ...

conformation. Substrate-controlled synthetic schemes have many advantages, since they do not require the use of complex asymmetric reagents to achieve selective transformations.

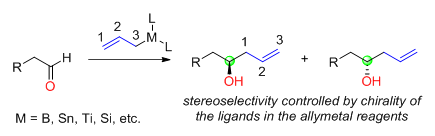

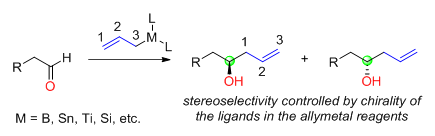

Reagent control: addition of chiral allylmetals to achiral aldehydes

Inorganic synthesis

Organic synthesis is a branch of chemical synthesis concerned with the construction of organic compounds. Organic compounds are molecules consisting of combinations of covalently-linked hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen atoms. Within the gen ...

, reagent control is an approach to selectively forming one stereoisomer

In stereochemistry, stereoisomerism, or spatial isomerism, is a form of isomerism in which molecules have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms in ...

out of many, the stereoselectivity

In chemistry, stereoselectivity is the property of a chemical reaction in which a single reactant forms an unequal mixture of stereoisomers during a non- stereospecific creation of a new stereocenter or during a non-stereospecific transformation ...

is determined by the structure and chirality

Chirality () is a property of asymmetry important in several branches of science. The word ''chirality'' is derived from the Greek (''kheir''), "hand", a familiar chiral object.

An object or a system is ''chiral'' if it is distinguishable fro ...

of the reagent used. When chiral allylmetals are used for nucleophilic addition

In organic chemistry, a nucleophilic addition (AN) reaction is an addition reaction where a chemical compound with an electrophilic double or triple bond reacts with a nucleophile, such that the double or triple bond is broken. Nucleophilic addit ...

reaction to achiral aldehydes

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () (lat. ''al''cohol ''dehyd''rogenatum, dehydrogenated alcohol) is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred ...

, the chirality

Chirality () is a property of asymmetry important in several branches of science. The word ''chirality'' is derived from the Greek (''kheir''), "hand", a familiar chiral object.

An object or a system is ''chiral'' if it is distinguishable fro ...

of the newly generated alcohol carbon is determined by the chirality of the allymetal reagents (Figure 1). The chirality of the allymetals usually comes from the asymmetric ligands used. The metals in the allylmetal reagents include boron

Boron is a chemical element; it has symbol B and atomic number 5. In its crystalline form it is a brittle, dark, lustrous metalloid; in its amorphous form it is a brown powder. As the lightest element of the boron group it has three ...

, tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

, titanium

Titanium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ti and atomic number 22. Found in nature only as an oxide, it can be reduced to produce a lustrous transition metal with a silver color, low density, and high strength, resistant to corrosion in ...

, silicon

Silicon is a chemical element; it has symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic lustre, and is a tetravalent metalloid (sometimes considered a non-metal) and semiconductor. It is a membe ...

, etc.

Various chiral ligands have been developed to prepare chiral allylmetals for the reaction with aldehydes. H. C. Brown was the first to report the chiral allylboron reagents for asymmetric allylation reactions with aldehydes. The chiral allylboron reagents were synthesized from the natural product (+)-a-pinene in two steps. The TADDOL ligands developed by

Various chiral ligands have been developed to prepare chiral allylmetals for the reaction with aldehydes. H. C. Brown was the first to report the chiral allylboron reagents for asymmetric allylation reactions with aldehydes. The chiral allylboron reagents were synthesized from the natural product (+)-a-pinene in two steps. The TADDOL ligands developed by Dieter Seebach

Dieter Seebach is a German chemist known for his synthesis of biopolymers and dendrimers, and for his contributions to stereochemistry. He was born on 31 October 1937 in Karlsruhe. He studied chemistry at the University of Karlsruhe (TH) under t ...

has been used to prepare chiral allyltitanium compounds for asymmetric allylation with aldehydes. Jim Leighton has developed chiral allysilicon compounds in which the release of ring strain facilitated the stereoselective allylation reaction, 95% to 98% enantiomeric excess could be achieved for a range of achiral aldehydes.Kinnaird, J. W. A.; Ng, P. Y.; Kubota, K.; Wang, X.; Leighton, J. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 7920.

See also

* Macrocyclic stereocontrol * Cieplak effectReferences

External links

The Evolution of Models for Carbonyl Addition

Evans Group Afternoon Seminar Sarah Siska February 9, 2001 {{Chiral synthesis Stereochemistry Induct