Aristotle's Biology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aristotle's biology is the theory of

Aristotle's biology is the theory of

As analysed by the evolutionary biologist Armand Leroi, Aristotle's biology included five major interlocking processes:

# a

As analysed by the evolutionary biologist Armand Leroi, Aristotle's biology included five major interlocking processes:

# a

Aristotle was the first person to study biology systematically. He spent two years observing and describing the zoology of

Aristotle was the first person to study biology systematically. He spent two years observing and describing the zoology of

Aristotle stated in the ''History of Animals'' that all beings were arranged in a fixed scale of perfection, reflected in their form (''eidos''). They stretched from minerals to plants and animals, and on up to man, forming the '' ''scala naturae'' or great chain of being''. His system had eleven grades, arranged according to the potentiality of each being, expressed in their form at birth. The highest animals gave birth to warm and wet creatures alive, the lowest bore theirs cold, dry, and in thick eggs. The system was based on Aristotle's interpretation of the four elements in his '' On Generation and Corruption'':

Aristotle stated in the ''History of Animals'' that all beings were arranged in a fixed scale of perfection, reflected in their form (''eidos''). They stretched from minerals to plants and animals, and on up to man, forming the '' ''scala naturae'' or great chain of being''. His system had eleven grades, arranged according to the potentiality of each being, expressed in their form at birth. The highest animals gave birth to warm and wet creatures alive, the lowest bore theirs cold, dry, and in thick eggs. The system was based on Aristotle's interpretation of the four elements in his '' On Generation and Corruption'':

The book was mentioned by Al-Kindī (d. 850), and commented on by

The book was mentioned by Al-Kindī (d. 850), and commented on by

In the

In the

De Juventute et Senectute, De Vita et Morte, De Respiratione

Aristotle's biology is the theory of

Aristotle's biology is the theory of biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

, grounded in systematic observation and collection of data, mainly zoological

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

, embodied in Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's books on the science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

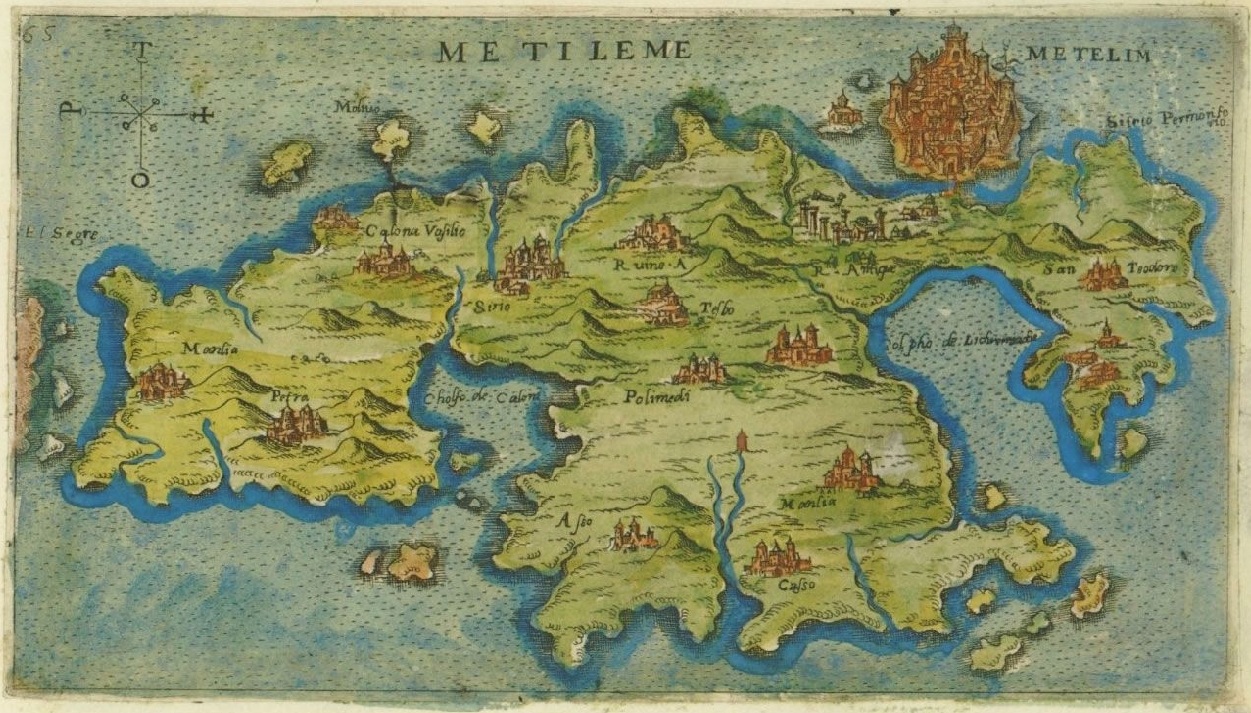

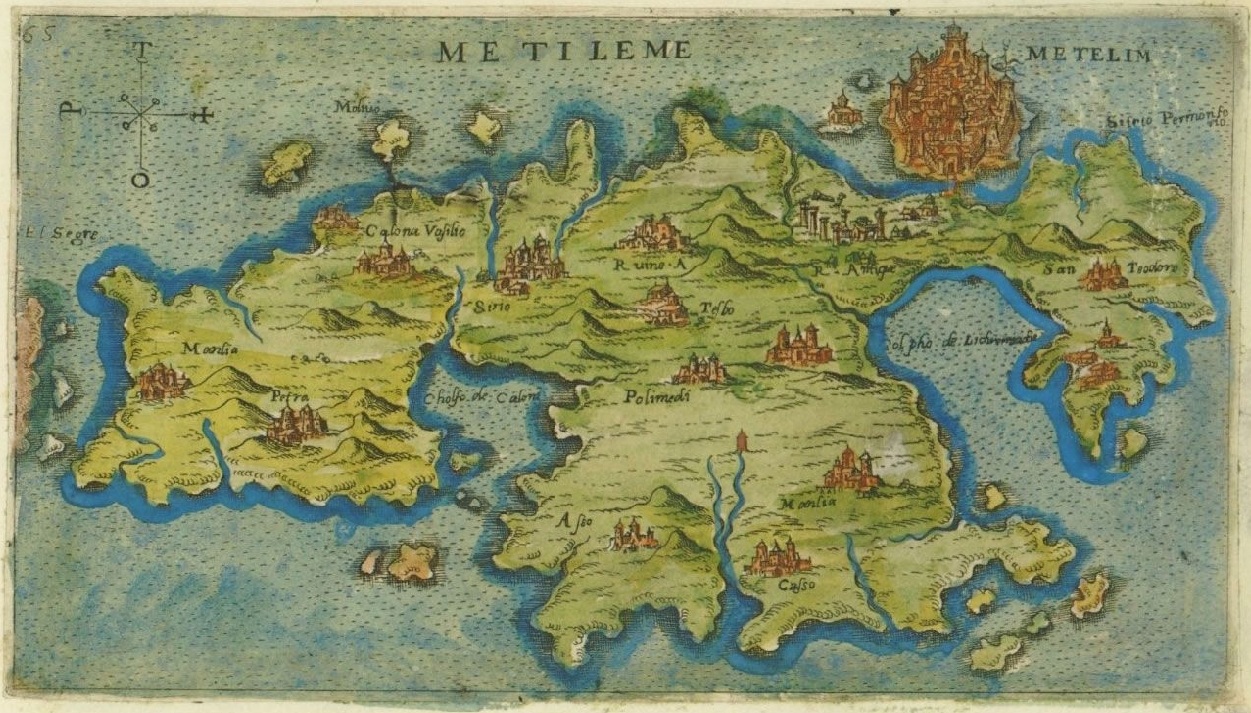

. Many of his observations were made during his stay on the island of Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

, including especially his descriptions of the marine biology

Marine biology is the scientific study of the biology of marine life, organisms that inhabit the sea. Given that in biology many scientific classification, phyla, family (biology), families and genera have some species that live in the sea and ...

of the Pyrrha lagoon, now the Gulf of Kalloni. His theory is based on his concept of form, which derives from but is markedly unlike Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

's theory of Forms

The Theory of Forms or Theory of Ideas, also known as Platonic idealism or Platonic realism, is a philosophical theory credited to the Classical Greek philosopher Plato.

A major concept in metaphysics, the theory suggests that the physical w ...

.

The theory describes five major biological processes, namely metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

, temperature regulation, information processing, embryogenesis

An embryo ( ) is the initial stage of development for a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male ...

, and inheritance

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Offi ...

. Each was defined in some detail, in some cases sufficient to enable modern biologists to create mathematical models of the mechanisms described. Aristotle's method, too, resembled the style of science used by modern biologists when exploring a new area, with systematic data collection, discovery of patterns, and inference of possible causal explanations from these. He did not perform experiments in the modern sense, but made observations of living animals and carried out dissections. He names some 500 species of bird, mammal, and fish; and he distinguishes dozens of insects and other invertebrates. He describes the internal anatomy of over a hundred animals, and dissected around 35 of these.

Aristotle's writings on biology, the first in the history of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient history, ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural science, natural, social science, social, and formal science, formal. Pr ...

, are scattered across several books, forming about a quarter of his writings that have survived. The main biology texts were the '' History of Animals'', ''Generation of Animals

The ''Generation of Animals'' (or ''On the Generation of Animals''; Greek: ''Περὶ ζῴων γενέσεως'' (''Peri Zoion Geneseos''); Latin: ''De Generatione Animalium'') is one of the biological works of the Corpus Aristotelicum, the col ...

'', ''Movement of Animals

''Movement of Animals'' (or ''On the Motion of Animals''; Greek Περὶ ζῴων κινήσεως; Latin ''De Motu Animalium'') is one of Aristotle's major texts on biology. It sets out the general principles of animal locomotion

In etho ...

'', '' Progression of Animals'', '' Parts of Animals'', and '' On the Soul'', as well as the lost drawings of ''The Anatomies'' which accompanied the ''History''.

Apart from his pupil, Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

, who wrote a matching '' Enquiry into Plants'', no research of comparable scope was carried out in ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

, though Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

medicine in Egypt continued Aristotle's inquiry into the mechanisms of the human body. Aristotle's biology was influential in the medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

Islamic world. Translation of Arabic versions and commentaries into Latin brought knowledge of Aristotle back into Western Europe, but the only biological work widely taught in medieval universities was ''On the Soul''. The association of his work with medieval scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

, as well as errors in his theories, caused Early Modern

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

scientists such as Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

and William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions to anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, pulmonary and systemic circulation ...

to reject Aristotle. Criticism of his errors and secondhand reports continued for centuries. He has found better acceptance among zoologists

This is a list of notable zoologists who have published names of new taxa under the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature.

A

* Abe – Tokiharu Abe (1911–1996)

* Abeille de Perrin, Ab. – Elzéar Abeille de Perrin (1843–1910)

* ...

, and some of his long-derided observations in marine biology

Marine biology is the scientific study of the biology of marine life, organisms that inhabit the sea. Given that in biology many scientific classification, phyla, family (biology), families and genera have some species that live in the sea and ...

have been found in modern times to be true.

Context

Aristotle's background

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

(384–322 BC) studied at Plato's Academy in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, remaining there for about 20 years. Like Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, he sought universals in his philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, but unlike Plato he backed up his views with detailed and systematic observation, notably of the natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

of the island of Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

, where he spent about two years, and the marine life

Marine life, sea life or ocean life is the collective ecological communities that encompass all aquatic animals, aquatic plant, plants, algae, marine fungi, fungi, marine protists, protists, single-celled marine microorganisms, microorganisms ...

in the seas around it, especially of the Pyrrha lagoon in the island's centre. This study made him the earliest scientist whose written work survives. No similarly detailed work on zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

was attempted until the sixteenth century; accordingly Aristotle remained highly influential for some two thousand years. He returned to Athens and founded his own school, the Lycaeum, where he taught for the last dozen years of his life. His writings on zoology form about a quarter of his surviving work. Aristotle's pupil Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

later wrote a similar book on botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

, ''Enquiry into Plants''.

Aristotelian forms

Aristotle's biology is constructed on the basis of his theory of form, which is derived from Plato'stheory of Forms

The Theory of Forms or Theory of Ideas, also known as Platonic idealism or Platonic realism, is a philosophical theory credited to the Classical Greek philosopher Plato.

A major concept in metaphysics, the theory suggests that the physical w ...

, but significantly different from it. Plato's Forms were eternal and fixed, being "blueprints in the mind of God". Real things in the world could, in Plato's view, at best be approximations to these perfect Forms. Aristotle heard Plato's view and developed it into a set of three biological concepts. He uses the same Greek word, (''eidos''), to mean first of all the set of visible features that uniquely characterised a kind of animal. Aristotle used the word γένος (génos) to mean a kind. For example, the kind of animal called a bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

has feathers, a beak, wings, a hard-shelled egg, and warm blood.

Aristotle further noted that there are many bird forms within the bird kind – cranes, eagle

Eagle is the common name for the golden eagle, bald eagle, and other birds of prey in the family of the Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of Genus, genera, some of which are closely related. True eagles comprise the genus ''Aquila ( ...

s, crow

A crow is a bird of the genus ''Corvus'', or more broadly, a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not linked scientifically to any certain trait but is rathe ...

s, bustards, sparrows, and so on, just as there are many forms of fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

es within the fish kind. He sometimes called these ''atoma eidē'', indivisible forms. Human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

is one of these indivisible forms: Socrates and the rest of us are all different individually, but we all have human form. More recent studies have shown that Aristotle used the terms γένος (génos) and (''eidos'') in a relative way. A taxon that is considered an eidos in one context can be considered a ''génos'' (which includes various ''eide'') in another.

Finally, Aristotle observed that the child does not take just any form, but is given it by the parents' seeds, which combine. These seeds thus contain form, or in modern terms information. Aristotle makes clear that he sometimes intends this third sense by giving the analogy of a woodcarving. It takes its form from wood (its material cause); the tools and carving technique used to make it (its efficient cause); and the design laid out for it (its ''eidos'' or embedded information). Aristotle further emphasises the informational nature of form by arguing that a body is compounded of elements like earth and fire, just as a word is compounded of letters in a specific order.

System

Soul as system

As analysed by the evolutionary biologist Armand Leroi, Aristotle's biology included five major interlocking processes:

# a

As analysed by the evolutionary biologist Armand Leroi, Aristotle's biology included five major interlocking processes:

# a metabolic

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the ...

process, whereby animals take in matter, change its qualities, and distribute these to use to grow, live, and reproduce

# a cycle of temperature regulation, whereby animals maintain a steady state, but which progressively fails in old age

# an information processing model whereby animals receive sensory information, alter it in the seat of sensation, and use it to drive movements of the limbs. He thus separated sensation from thought, unlike all previous philosophers except Alcmaeon.

# the process of inheritance

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Offi ...

.

# the processes of embryonic development

In developmental biology, animal embryonic development, also known as animal embryogenesis, is the developmental stage of an animal embryo. Embryonic development starts with the fertilization of an egg cell (ovum) by a sperm, sperm cell (spermat ...

and of spontaneous generation

The five processes formed what Aristotle called the soul: it was not something extra, but the system consisting exactly of these mechanisms. The Aristotelian soul died with the animal and was thus purely biological. Different types of organism possessed different types of soul. Plants had a vegetative soul, responsible for reproduction and growth. Animals had both a vegetative and a sensitive soul, responsible for mobility and sensation. Humans, uniquely, had a vegetative, a sensitive, and a rational soul, capable of thought and reflection.

Processes

Metabolism

Aristotle's account of metabolism sought to explain how food was processed by the body to provide both heat and the materials for the body's construction and maintenance. The metabolic system for live-bearing tetrapods described in the ''Parts of Animals'' can be modelled as an open system, a branching tree of flows of material through the body. The system worked as follows. The incoming material, food, enters the body and is concocted into blood; waste is excreted as urine, bile, and faeces, and the element fire is released as heat. Blood is made into flesh, the rest forming other earthy tissues such as bones, teeth, cartilages and sinews. Leftover blood is made intofat

In nutrition science, nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such chemical compound, compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

The term often refers specif ...

, whether soft suet or hard lard. Some fat from all around the body is made into semen

Semen, also known as seminal fluid, is a bodily fluid that contains spermatozoon, spermatozoa which is secreted by the male gonads (sexual glands) and other sexual organs of male or hermaphrodite, hermaphroditic animals. In humans and placen ...

.

All the tissues are in Aristotle's view completely uniform parts with no internal structure of any kind; a cartilage for example was the same all the way through, not subdivided into atoms as Democritus

Democritus (, ; , ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, Thrace, Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an ...

(c. 460–c. 370 BC) had argued. The uniform parts can be arranged on a scale of Aristotelian qualities, from the coldest and driest, such as hair, to the hottest and wettest, such as milk.

At each stage of metabolism, residual materials are excreted as faeces, urine, and bile.

Temperature regulation

Aristotle's account of temperature regulation sought to explain how an animal maintained a steady temperature and the continued oscillation of the thorax needed for breathing. The system of regulation of temperature and breathing described in ''Youth and Old Age, Life and Death'' 26 is sufficiently detailed to permit modelling as anegative feedback

Negative feedback (or balancing feedback) occurs when some function (Mathematics), function of the output of a system, process, or mechanism is feedback, fed back in a manner that tends to reduce the fluctuations in the output, whether caused ...

control system

A control system manages, commands, directs, or regulates the behavior of other devices or systems using control loops. It can range from a single home heating controller using a thermostat controlling a domestic boiler to large industrial ...

(one that maintains a desired property by opposing disturbances to it), with a few assumptions such as a desired temperature to compare the actual temperature against.

The system worked as follows. Heat is constantly lost from the body. Food products reach the heart and are processed into new blood, releasing fire during metabolism, which raises the blood temperature too high. That raises the heart temperature, causing lung volume to increase, in turn raising the airflow at the mouth. The cool air brought in through the mouth reduces the heart temperature, so the lung volume accordingly decreases, restoring the temperature to normal.

The mechanism only works if the air is cooler than the reference temperature. If the air is hotter than that, the system becomes a positive feedback cycle, the body's fire is put out, and death follows. The system as described damps out fluctuations in temperature. Aristotle however predicted that his system would cause lung oscillation (breathing), which is possible given extra assumptions such as of delays or non-linear responses.

Information processing

Aristotle's information processing model has been named the "centralized incoming and outgoing motions model". It sought to explain how changes in the world led to appropriate behaviour in the animal. The system worked as follows. The animal's sense organ is altered when it detects an object. This causes a perceptual change in the animal's seat of sensation, which Aristotle believed was the heart ( cardiocentrism) rather than thebrain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

. This in turn causes a change in the heart's heat, which causes a quantitative change sufficient to make the heart transmit a mechanical impulse to a limb, which moves, moving the animal's body. The alteration in the heat of the heart also causes a change in the consistency of the joints, which helps the limb to move.

There is thus a causal chain which transmits information from a sense organ to an organ capable of making decisions, and onwards to a motor organ. In this respect, the model is analogous to a modern understanding of information processing such as in sensory-motor coupling

Sensory-motor coupling is the coupling or integration of the sensory system and motor system. For a given stimulus, there is no one single motor command. "Neural responses at almost every stage of a sensorimotor pathway are modified at short and l ...

.

Inheritance

Aristotle's inheritance model sought to explain how the parents' characteristics are transmitted to the child, subject to influence from the environment. The system worked as follows. The father's semen and the mother's menses have movements that encode their parental characteristics. The model is partly asymmetric, as only the father's movements define the form or ''eidos'' of the species, while the movements of both the father's and the mother's uniform parts define features other than the form, such as the father's eye colour or the mother's nose shape. Aristotle's theory has some symmetry, as semen movements carry maleness while the menses carry femaleness. If the semen is hot enough to overpower the cold menses, the child will be a boy; but if it is too cold to do this, the child will be a girl. Inheritance is thus particulate (definitely one trait or another), as in Mendelian genetics, unlike the Hippocratic model which was continuous and blending. The child's sex can be influenced by factors that affect temperature, including the weather, the wind direction, diet, and the father's age. Features other than sex also depend on whether the semen overpowers the menses, so if a man has strong semen, he will have sons who resemble him, while if the semen is weak, he will have daughters who resemble their mother.Embryogenesis

Aristotle's model ofembryogenesis

An embryo ( ) is the initial stage of development for a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male ...

sought to explain how the inherited parental characteristics cause the formation and development of an embryo.

The system worked as follows. First, the father's semen curdles the mother's menses, which Aristotle compares with how rennet

Rennet () is a complex set of enzymes produced in the stomachs of ruminant mammals. Chymosin, its key component, is a protease, protease enzyme that curdling, curdles the casein in milk. In addition to chymosin, rennet contains other enzymes, su ...

(an enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

from a cow's stomach) curdles milk in cheesemaking. This forms the embryo; it is then developed by the action of the ''pneuma'' (literally, breath or spirit) in the semen. The ''pneuma'' first makes the heart appear; this is vital, as the heart nourishes all other organs. Aristotle observed that the heart is the first organ seen to be active (beating) in a hen's egg. The ''pneuma'' then makes the other organs develop.

Aristotle asserts in his ''Physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

'' that according to Empedocles

Empedocles (; ; , 444–443 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is known best for originating the Cosmogony, cosmogonic theory of the four cla ...

, order "spontaneously" appears in the developing embryo. In ''The Parts of Animals

''Parts of Animals'' (or ''On the Parts of Animals''; Ancient Greek, Greek Περὶ ζῴων μορίων; Latin ''De Partibus Animalium'') is one of Aristotle's major Aristotle's biology, texts on biology. It was written around 350 BC. The whole ...

'', he argues that what he describes as a theory of Empedocles, that the vertebral column

The spinal column, also known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone, is the core part of the axial skeleton in vertebrates. The vertebral column is the defining and eponymous characteristic of the vertebrate. The spinal column is a segmente ...

is divided into vertebrae because, as it happens, the embryo twists about and snaps the column into pieces, is wrong. Aristotle argues instead that the process has a predefined goal: that the "seed" that develops into the embryo began with an inbuilt "potential" to become specific body parts, such as vertebrae. Further, each sort of animal gives rise to animals of its own kind: humans only have human babies.

Method

Aristotle has been called unscientific by philosophers fromFrancis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

onwards for at least two reasons: his scientific style, and his use of explanation

An explanation is a set of statements usually constructed to describe a set of facts that clarifies the causes, context, and consequences of those facts. It may establish rules or laws, and clarifies the existing rules or laws in relation ...

. His explanations are in turn made cryptic by his complicated system of causes. However, these charges need to be considered in the light of what was known in his own time. His systematic gathering of data, too, is obscured by the lack of modern methods of presentation, such as tables of data: for example, the whole of '' History of Animals'' Book VI is taken up with a list of observations of the life histories of birds that "would now be summarized in a single table in ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'' – and in the Online Supplementary Information at that".

Scientific style

Aristotle did not doexperiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs whe ...

s in the modern sense. He used the ancient Greek term ''pepeiramenoi'' to mean observations, or at most investigative procedures, such as (in ''Generation of Animals'') finding a fertilised hen's egg of a suitable stage and opening it so as to be able to see the embryo's heart inside.

Instead, he practised a different style of science: systematically gathering data, discovering patterns common to whole groups of animals, and inferring possible causal explanations from these. This style is common in modern biology when large amounts of data become available in a new field, such as genomics

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of molecular biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, ...

. It does not result in the same certainty as experimental science, but it sets out testable hypotheses and constructs a narrative explanation of what is observed. In this sense, Aristotle's biology is scientific.

From the data he collected and documented, Aristotle inferred quite a number of rules

Rule or ruling may refer to:

Human activity

* The exercise of political or personal control by someone with authority or power

* Business rule, a rule pertaining to the structure or behavior internal to a business

* School rule, a rule tha ...

relating the life-history features of the live-bearing tetrapods (terrestrial placental mammals) that he studied. Among these correct predictions are the following. Brood size decreases with (adult) body mass, so that an elephant

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant ('' Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian elephant ('' Elephas maximus ...

has fewer young (usually just one) per brood than a mouse

A mouse (: mice) is a small rodent. Characteristically, mice are known to have a pointed snout, small rounded ears, a body-length scaly tail, and a high breeding rate. The best known mouse species is the common house mouse (''Mus musculus'' ...

. Lifespan increases with gestation period, and also with body mass, so that elephants live longer than mice, have a longer period of gestation, and are heavier. As a final example, fecundity

Fecundity is defined in two ways; in human demography, it is the potential for reproduction of a recorded population as opposed to a sole organism, while in population biology, it is considered similar to fertility, the capability to produc ...

decreases with lifespan, so long-lived kinds like elephants have fewer young in total than short-lived kinds like mice.

Mechanism and analogy

Aristotle's use of explanation has been considered "fundamentally unscientific". The French playwrightMolière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, ; ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the great writers in the French language and world liter ...

's 1673 play '' The Imaginary Invalid'' portrays the quack Aristotelian doctor Argan blandly explaining that opium causes sleep by virtue of its dormitive leep-makingprinciple, its ''virtus dormitiva''. Argan's explanation is at best empty (devoid of mechanism), at worst vitalist

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

. But the real Aristotle did provide biological mechanisms, in the form of the five processes of metabolism, temperature regulation, information processing, embryonic development, and inheritance that he developed. Further, he provided mechanical, non-vitalist analogies for these theories, mentioning bellows, toy carts, the movement of water through porous pots, and even automatic puppets.

Complex causality

Readers of Aristotle have found thefour causes

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelianism, Aristotelian thought, categories of questions that explain "the why's" of something that exists or changes in nature. The four causes are the: #Material, material cause, the #Formal, f ...

that he uses in his biological explanations opaque, something not helped by many centuries of confused exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Ancient Greek, Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation (philosophy), interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Bible, Biblical works. In modern us ...

. For a biological system, these are however straightforward enough. The material cause is simply what a system is constructed from. The goal (final cause

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelian thought, categories of questions that explain "the why's" of something that exists or changes in nature. The four causes are the: material cause, the formal cause, the efficient cause, ...

) and formal cause are what something is for, its function: to a modern biologist, such teleology describes adaptation

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the p ...

under the pressure of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

. The efficient cause is how a system develops and moves: to a modern biologist, those are explained by developmental biology

Developmental biology is the study of the process by which animals and plants grow and develop. Developmental biology also encompasses the biology of Regeneration (biology), regeneration, asexual reproduction, metamorphosis, and the growth and di ...

and physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

. Biologists continue to offer explanations of these same kinds.

Empirical research

Aristotle was the first person to study biology systematically. He spent two years observing and describing the zoology of

Aristotle was the first person to study biology systematically. He spent two years observing and describing the zoology of Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

and the surrounding seas, including in particular the Pyrrha

In Greek mythology, Pyrrha (; ) was the daughter of Epimetheus and Pandora and wife of Deucalion of whom she had three sons, Hellen, Amphictyon, Orestheus; and three daughters Protogeneia, Pandora and Thyia. According to some accounts, Hell ...

lagoon in the centre of Lesbos. His data are assembled from his own observations, statements given by people with specialised knowledge such as beekeeper

A beekeeper is a person who keeps honey bees, a profession known as beekeeping. The term beekeeper refers to a person who keeps honey bees in beehives, boxes, or other receptacles. The beekeeper does not control the creatures. The beekeeper ow ...

s and fishermen, and less accurate accounts provided by travellers from overseas.

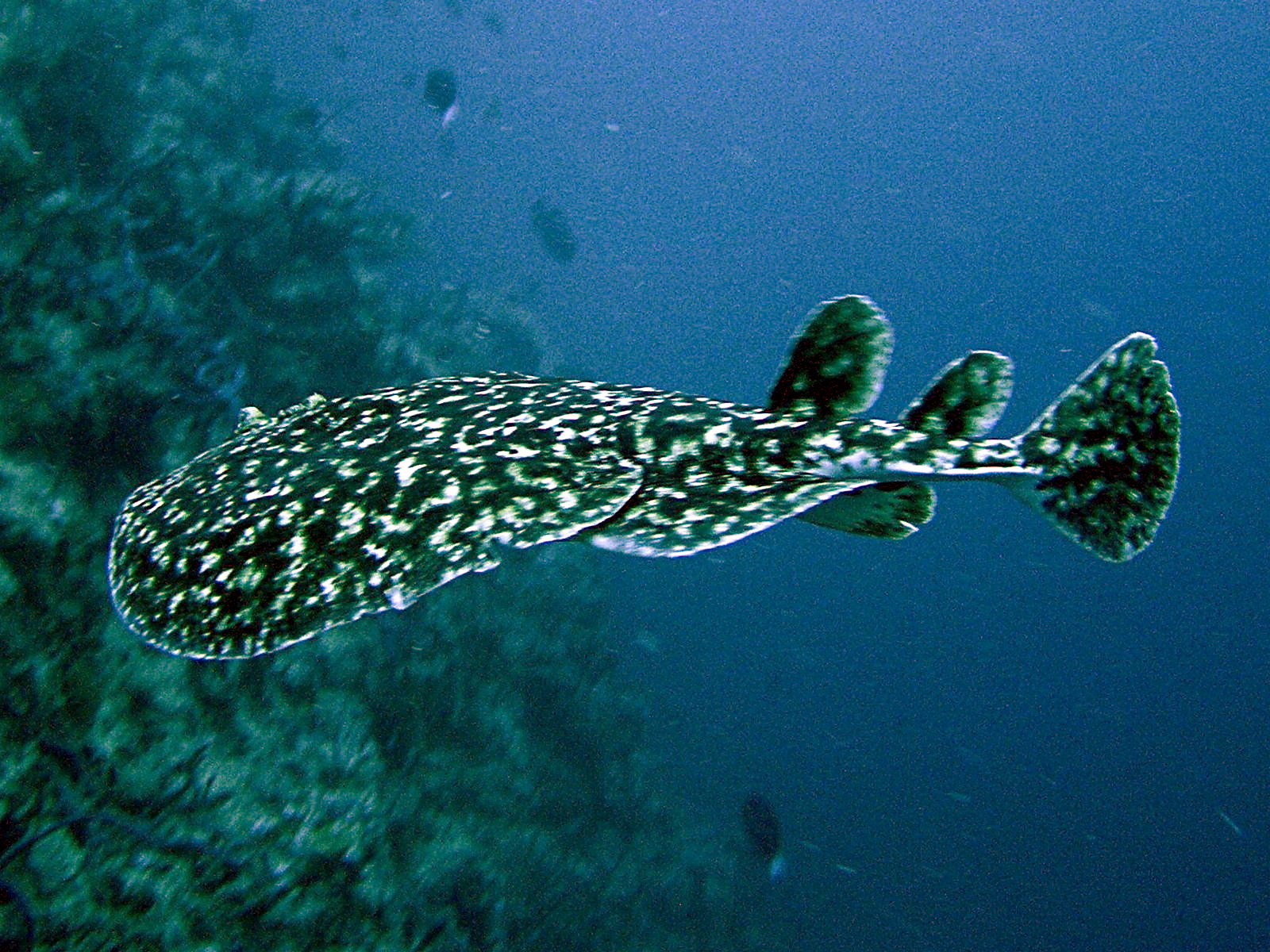

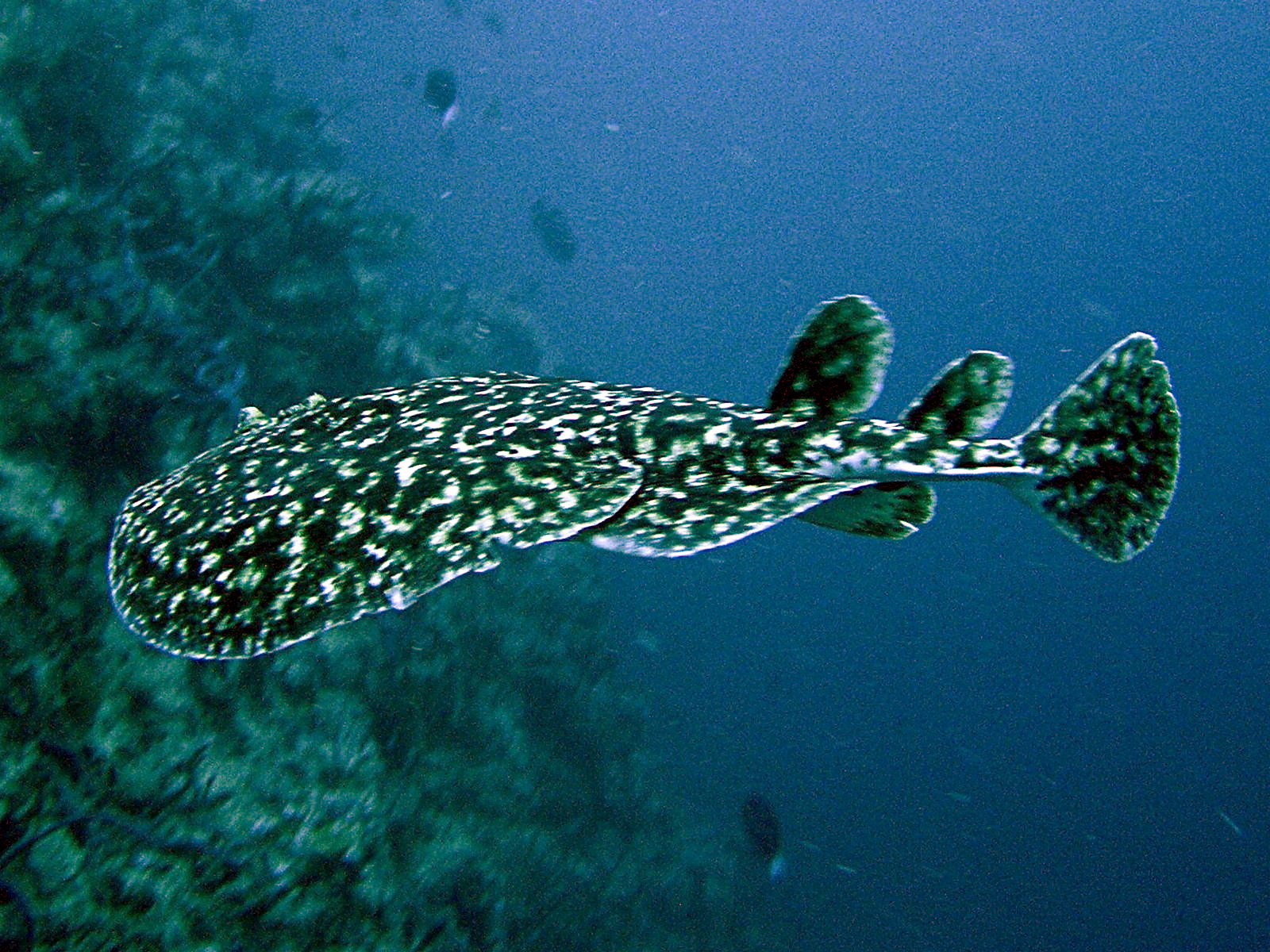

His observations on catfish

Catfish (or catfishes; order (biology), order Siluriformes or Nematognathi) are a diverse group of ray-finned fish. Catfish are common name, named for their prominent barbel (anatomy), barbels, which resemble a cat's whiskers, though not ...

, electric fish (''Torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

'') and angler fish are detailed, as is his writing on cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

s including the octopus

An octopus (: octopuses or octopodes) is a soft-bodied, eight-limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttlefish, and nautiloids. Like oth ...

, cuttlefish

Cuttlefish, or cuttles, are Marine (ocean), marine Mollusca, molluscs of the order (biology), suborder Sepiina. They belong to the class (biology), class Cephalopoda which also includes squid, octopuses, and nautiluses. Cuttlefish have a unique ...

and paper nautilus. He reported that fishermen had asserted that the octopus’s hectocotyl arm was used in sexual reproduction. He admitted its use in mating 'only for the sake of attachment', but rejected the idea that it was useful for generation, since "it is outside the passage and indeed outside the body". In the 19th century, biologists found that the reported function was correct. He separated the aquatic mammals from fish, and knew that shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch cartilaginous fish characterized by a ribless endoskeleton, dermal denticles, five to seven gill slits on each side, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the ...

s and rays were part of the group he called ''Selachē'' (roughly, the modern zoologist's selachians).

Among many other things, he gave accurate descriptions of the four-chambered stomachs of ruminant

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microb ...

s, and of the ovoviviparous embryological development of the dogfish. His accounts of about 35 animals are sufficiently detailed to convince biologists that he dissected those species, indeed vivisecting some; he mentions the internal anatomy of roughly 110 animals in total.

Classification

Aristotle distinguished about 500 species of birds, mammals, actinopterygians and selachians in ''History of Animals'' and '' Parts of Animals''. Aristotle distinguished animals with blood, ''Enhaima'' (the modern zoologist'svertebrates

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

) and animals without blood, ''Anhaima'' (invertebrates

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordate subphylum ...

).

Animals with blood included live-bearing tetrapods, ''Zōiotoka tetrapoda'' (roughly, the mammals

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three middle e ...

), being warm, having four legs, and giving birth to their young.

The cetacea

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

ns, ''Kētōdē'', also had blood and gave birth to live young, but did not have legs, and therefore formed a separate group (''megista genē'', defined by a set of functioning "parts").

The birds, ''Ornithes'' had blood and laid eggs, but had only 2 legs and were a distinct form (''eidos'') with feathers and beaks instead of teeth, so they too formed a distinct group, of over 50 kinds.

The egg-bearing tetrapods, ''Ōiotoka tetrapoda'' (reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

s and amphibians

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

) had blood and four legs, but were cold and laid eggs, so were a distinct group.

The snake

Snakes are elongated limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales much like other members of the group. Many species of snakes have s ...

s, ''Opheis'', similarly had blood, but no legs, and laid dry eggs, so were a separate group.

The fishes

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fins and a hard skull, but lacking limbs with digits. Fish can be grouped into the more basal jawless fish and the more common jawed ...

, ''Ikhthyes'', had blood but no legs, and laid wet eggs, forming a definite group. Among them, the selachians ''Selakhē'' (sharks and rays), had cartilage

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. Semi-transparent and non-porous, it is usually covered by a tough and fibrous membrane called perichondrium. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints ...

s instead of bones and were viviparous (Aristotle did not know that some selachians are oviparous).

Animals without blood were divided into soft-shelled ''Malakostraka'' ( crabs, lobsters, and shrimps); hard-shelled ''Ostrakoderma'' (gastropods

Gastropods (), commonly known as slugs and snails, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, freshwater, and from the land. Ther ...

and bivalves); soft-bodied ''Malakia'' (cephalopods

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

); and divisible animals ''Entoma'' (insects

Insects (from Latin ') are hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs of jointed ...

, spiders, scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the Order (biology), order Scorpiones. They have eight legs and are easily recognized by a pair of Chela (organ), grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward cur ...

s, ticks). Other animals without blood included fish lice, hermit crabs, red coral, sea anemone

Sea anemones ( ) are a group of predation, predatory marine invertebrates constituting the order (biology), order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the ''Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemone ...

s, sponges

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and ar ...

, starfish

Starfish or sea stars are Star polygon, star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class (biology), class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to brittle star, ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to ...

and various worms: Aristotle did not classify these into groups, although Aristotle mentioned that the sea anemone

Sea anemones ( ) are a group of predation, predatory marine invertebrates constituting the order (biology), order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the ''Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemone ...

was in its "own group".

Scale of being

Aristotle stated in the ''History of Animals'' that all beings were arranged in a fixed scale of perfection, reflected in their form (''eidos''). They stretched from minerals to plants and animals, and on up to man, forming the '' ''scala naturae'' or great chain of being''. His system had eleven grades, arranged according to the potentiality of each being, expressed in their form at birth. The highest animals gave birth to warm and wet creatures alive, the lowest bore theirs cold, dry, and in thick eggs. The system was based on Aristotle's interpretation of the four elements in his '' On Generation and Corruption'':

Aristotle stated in the ''History of Animals'' that all beings were arranged in a fixed scale of perfection, reflected in their form (''eidos''). They stretched from minerals to plants and animals, and on up to man, forming the '' ''scala naturae'' or great chain of being''. His system had eleven grades, arranged according to the potentiality of each being, expressed in their form at birth. The highest animals gave birth to warm and wet creatures alive, the lowest bore theirs cold, dry, and in thick eggs. The system was based on Aristotle's interpretation of the four elements in his '' On Generation and Corruption'': Fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a fuel in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction Product (chemistry), products.

Flames, the most visible portion of the fire, are produced in the combustion re ...

(hot and dry); Air

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

(hot and wet); Water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

(cold and wet); and Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

(cold and dry). These are arranged from the most energetic to the least, so the warm, wet young raised in a womb with a placenta

The placenta (: placentas or placentae) is a temporary embryonic and later fetal organ that begins developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrient, gas, and waste exchange between ...

were higher on the scale than the cold, dry, nearly mineral eggs of birds. However, Aristotle is careful never to insist that a group fits perfectly in the scale; he knows animals have many combinations of attributes, and that placements are approximate.

Influence

On Theophrastus

Aristotle's pupil and successor at theLyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

, Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

, wrote the '' History of Plants'', the first classical book of botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

. It has an Aristotelian structure, but rather than focus on formal causes, as Aristotle did, Theophrastus described how plants functioned. Where Aristotle expanded on grand theories, Theophrastus was quietly empirical. Where Aristotle insisted that species have a fixed place on the ''scala naturae'', Theophrastus suggests that one kind of plant can transform into another, as when a field sown to wheat

Wheat is a group of wild and crop domestication, domesticated Poaceae, grasses of the genus ''Triticum'' (). They are Agriculture, cultivated for their cereal grains, which are staple foods around the world. Well-known Taxonomy of wheat, whe ...

turns to the weed darnel.

On Hellenistic medicine

After Theophrastus, though interest in Aristotle's ideas survived, they were generally taken unquestioningly.Annas, "Classical Greek Philosophy", 2001, p. 252. In Boardman, John; Griffin, Jasper; Murray, Oswyn (ed.) ''The Oxford History of the Classical World''.Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

. It is not until the age of Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

under the Ptolemies that advances in biology resumed. The first medical teacher at Alexandria, Herophilus of Chalcedon, corrected Aristotle, placing intelligence in the brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

, and connected the nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the complex system, highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its behavior, actions and sense, sensory information by transmitting action potential, signals to and from different parts of its body. Th ...

to motion and sensation. Herophilus also distinguished between vein

Veins () are blood vessels in the circulatory system of humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are those of the pulmonary and feta ...

s and arteries

An artery () is a blood vessel in humans and most other animals that takes oxygenated blood away from the heart in the systemic circulation to one or more parts of the body. Exceptions that carry deoxygenated blood are the pulmonary arteries in ...

, noting that the latter pulse while the former do not.

On Islamic zoology

Many classical works including those of Aristotle were transmitted from Greek to Syriac, then to Arabic, then to Latin in the Middle Ages. Aristotle remained the principal authority in biology for the next two thousand years. The '' Kitāb al-Hayawān'' (كتاب الحيوان, ''Book of Animals'') is a 9th-centuryArabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

translation of ''History of Animals'': 1–10, ''On the Parts of Animals'': 11–14, and ''Generation of Animals'': 15–19.

The book was mentioned by Al-Kindī (d. 850), and commented on by

The book was mentioned by Al-Kindī (d. 850), and commented on by Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

(Ibn Sīnā) in his '' Kitāb al-Šifā'' (کتاب الشفاء, ''The Book of Healing''). Avempace (Ibn Bājja) and Averroes

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinization of names, Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and Faqīh, jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astron ...

(Ibn Rushd) commented on ''On the Parts of Animals'' and ''Generation of Animals'', Averroes criticising Avempace's interpretations.

On medieval science

When the Christian king Alfonso VI of Castile conquered Toledo from the Moors in 1085, an Arabic translation of Aristotle's works, with commentaries byAvicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

and Averroes

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinization of names, Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and Faqīh, jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astron ...

emerged into European medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

scholarship. Michael Scot translated much of Aristotle's biology into Latin, c. 1225, along with many of Averroes's commentaries. Albertus Magnus commented extensively on Aristotle, but added his own zoological observations and an encyclopedia of animals based on Thomas of Cantimpré. Later in the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

merged Aristotle's metaphysics with Christian theology. Whereas Albert had treated Aristotle's biology as science, writing that experiment was the only safe guide and joining in with the types of observation that Aristotle had made, Aquinas saw Aristotle purely as theory, and Aristotelian thought became associated with scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

. The scholastic natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

curriculum omitted most of Aristotle's biology, but included ''On the Soul''.

On Renaissance science

Renaissance zoologists made use of Aristotle's zoology in two ways. Especially in Italy, scholars such as Pietro Pomponazzi and Agostino Nifo lectured and wrote commentaries on Aristotle. Elsewhere, authors used Aristotle as one of their sources, alongside their own and their colleagues' observations, to create new encyclopedias such as Konrad Gessner's 1551 '' Historia Animalium''. The title and the philosophical approach were Aristotelian, but the work was largely new. Edward Wotton similarly helped to found modern zoology by arranging the animals according to Aristotle's theories, separating out folklore from his 1552 ''De differentiis animalium''. Aristotle's system of classification had thus remained influential for many centuries.Early Modern rejection

In the

In the Early Modern

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

period, Aristotle came to represent all that was obsolete, scholastic, and wrong, not helped by his association with medieval theology. In 1632, Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

represented Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by Prior Analytics, deductive logic and an Posterior Analytics, analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics ...

in his '' Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo'' (Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems) by the strawman Simplicio ("Simpleton"). That same year, William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions to anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, pulmonary and systemic circulation ...

proved Aristotle wrong by demonstrating that blood circulates.

Aristotle still represented the enemy of true science into the 20th century. Leroi noted that in 1985, Peter Medawar stated in "pure seventeenth century" tones that Aristotle had assembled "a strange and generally speaking rather tiresome farrago of hearsay

Hearsay, in a legal forum, is an out-of-court statement which is being offered in court for the truth of what was asserted. In most courts, hearsay evidence is Inadmissible evidence, inadmissible (the "hearsay evidence rule") unless an exception ...

, imperfect observation, wishful thinking and credulity amounting to downright gullibility".

19th century revival

Zoologists working in the 19th century, includingGeorges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

, Johannes Peter Müller

Johannes Peter Müller (14 July 1801 – 28 April 1858) was a German physiologist, comparative anatomist, ichthyologist, and herpetologist, known not only for his discoveries but also for his ability to synthesize knowledge. The paramesonephri ...

, and Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he recei ...

admired Aristotle's biology and investigated some of his observations. D'Arcy Thompson translated ''History of Animals'' in 1910, making a classically educated zoologist's informed attempt to identify the animals that Aristotle names, and to interpret and diagram his anatomical descriptions.

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

quoted a passage from Aristotle's ''Physics'' II 8 in '' The Origin of Species'', which entertains the possibility of a selection process following the random combination of body parts. Darwin comments that "We here see the principle of natural selection shadowed forth". However, two things mitigate against this interpretation. Firstly, Aristotle immediately rejected the possibility of such a process of assembling body parts. Secondly, according to Leroi, Aristotle was in any case discussing ontogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the ovum, egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to t ...

, the Empedoclean coming into being of an individual from component parts, not phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or Taxon, taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, M ...

and natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

. Darwin considered Aristotle the most important early contributor to biological thought; in an 1882 letter he wrote that "Linnaeus and Cuvier have been my two gods, though in very different ways, but they were mere schoolboys to old Aristotle."

20th and 21st century interest

Zoologists have frequently mocked Aristotle for errors and unverified secondhand reports. However, modern observation has confirmed one after another of his more surprising claims, including theactive camouflage

Active camouflage or adaptive camouflage is camouflage that adapts, often rapidly, to the surroundings of an object such as an animal or military vehicle. In theory, active camouflage could provide perfect concealment from visual detection.

Acti ...

of the octopus and the ability of elephants to snorkel with their trunks while swimming.

Aristotle remains largely unknown to modern scientists, though zoologists are perhaps most likely to mention him as "the father of biology"; the MarineBio Conservation Society notes that he identified "crustaceans

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of Arthropod, arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquat ...

, echinoderms

An echinoderm () is any animal of the phylum Echinodermata (), which includes starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars and sea cucumbers, as well as the sessile sea lilies or "stone lilies". While bilaterally symmetrical as larv ...

, mollusks, and fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

", that cetaceans

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

are mammals

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three middle e ...

, and that marine vertebrates could be either oviparous

Oviparous animals are animals that reproduce by depositing fertilized zygotes outside the body (i.e., by laying or spawning) in metabolically independent incubation organs known as eggs, which nurture the embryo into moving offsprings kno ...

or viviparous, so he "is often referred to as the father of marine biology

Marine biology is the scientific study of the biology of marine life, organisms that inhabit the sea. Given that in biology many scientific classification, phyla, family (biology), families and genera have some species that live in the sea and ...

".

Few practicing zoologists explicitly adhere to Aristotle's great chain of being, but its influence is still perceptible in the use of the terms "lower" and "upper" to designate taxa such as groups of plants.

The evolutionary zoologist Armand Leroi has taken an interest in Aristotle's biology. The concept of homology began with Aristotle, and the evolutionary developmental biologist Lewis I. Held commented that

Works

Aristotle did not write anything that resembles a modern, unified textbook of biology. Instead, he wrote a large number of "books" which, taken together, give an idea of his approach to the science. Some of these interlock, referring to each other, while others, such as the drawings of ''The Anatomies'' are lost, but referred to in the ''History of Animals'', where the reader is instructed to look at the diagrams to understand how the animal parts described are arranged, and it has even been possible to reconstruct (admittedly with much associated uncertainty) what some of these illustrations may have looked like, from Aristotle's descriptions. Aristotle's main biological works are the five books sometimes grouped as ''On Animals'' (De Animalibus), namely, with the conventional abbreviations shown in parentheses: * ''History of Animals'', or ''Inquiries into Animals'' (Historia Animalium) (HA) * ''Generation of Animals

The ''Generation of Animals'' (or ''On the Generation of Animals''; Greek: ''Περὶ ζῴων γενέσεως'' (''Peri Zoion Geneseos''); Latin: ''De Generatione Animalium'') is one of the biological works of the Corpus Aristotelicum, the col ...

'' (De Generatione Animalium) (GA)

* ''Movement of Animals

''Movement of Animals'' (or ''On the Motion of Animals''; Greek Περὶ ζῴων κινήσεως; Latin ''De Motu Animalium'') is one of Aristotle's major texts on biology. It sets out the general principles of animal locomotion

In etho ...

'' (De Motu Animalium) (DM)

* '' Parts of Animals'' (De Partibus Animalium) (PA)

* ''Progression of Animals'' or ''On the Gait of Animals'' (De Incessu Animalium) (IA)

together with '' On the Soul'' (De Anima) (DA).

In addition, a group of seven short works, conventionally forming the '' Parva Naturalia'' ("Short treatises on Nature"), is also mainly biological:

* '' Sense and Sensibilia'' (Sense)

* '' On Memory''

* '' On Sleep''

* '' On Dreams''

* '' On Divination in Sleep''

* '' On Length and Shortness of Life''

* ''On Youth, Old Age, Life and Death, and Respiration

''On Youth, Old Age, Life and Death, and Respiration'' ( Greek: ; ) is one of the short treatises that make up Aristotle's '' Parva Naturalia''.

Structure and contents Place in the ''Parva Naturalia''

In comparison to the first five treatises of t ...

''Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * {{Use dmy dates, date=April 2017 History of biology Biology History of zoology Ancient Greek science