Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station is a United States scientific research station at the

For the International Geophysical Year, the United States and many other countries embarked on an international exploration of the South Pole. This led to the USA creating a series of stations for this project, and returning to the South Pole. After a few years the Antarctic treaty was established that provided an international framework for the exploration and study of Antarctica.

In October 1956, a U.S. Navy R4D-5L named ''Que Sera Sera'' (One of the many versions of the DC-3) landed at the South Pole in Antarctica. This was the first time humans had been at the pole since 1912 (see Robert F. Scott's British Antarctic Expedition).

South Pole station was one of seven bases that the United States built for the

For the International Geophysical Year, the United States and many other countries embarked on an international exploration of the South Pole. This led to the USA creating a series of stations for this project, and returning to the South Pole. After a few years the Antarctic treaty was established that provided an international framework for the exploration and study of Antarctica.

In October 1956, a U.S. Navy R4D-5L named ''Que Sera Sera'' (One of the many versions of the DC-3) landed at the South Pole in Antarctica. This was the first time humans had been at the pole since 1912 (see Robert F. Scott's British Antarctic Expedition).

South Pole station was one of seven bases that the United States built for the

The station was moved in 1975 to the newly constructed

The station was moved in 1975 to the newly constructed

File:Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station.jpg, The main entrance to the former

File:SPSM.05.jpg, An aerial view of the Amundsen–Scott Station in January 2005. The older domed station is visible on the right-hand side of this photo.

File:Amundsen-scott-south pole station 2007.jpg, The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station during the 2007–2008 summer season.

File:Amundsen-Scott marsstation ray h edit.jpg, A photo of the station at night. The new station can be seen in the far left, the

Data access to the station is provided by

Data access to the station is provided by

Cosmic Microwave Background Telescopes

* Python Telescope (1992–1997), used to observe temperature anisotropies in the

Cosmic Microwave Background Telescopes

* Python Telescope (1992–1997), used to observe temperature anisotropies in the

Science and life at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole station is documented in Dr. John Bird's award-winning book, ''One Day, One Night: Portraits of the South Pole'' which chronicles the South Pole Foucault Pendulum, the 300 Club, the first midwinter medevac, and science at the Pole including climate change and cosmology.

Science fiction author

Science and life at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole station is documented in Dr. John Bird's award-winning book, ''One Day, One Night: Portraits of the South Pole'' which chronicles the South Pole Foucault Pendulum, the 300 Club, the first midwinter medevac, and science at the Pole including climate change and cosmology.

Science fiction author

South Pole Station

by Ashley Shelby is set at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole station of 2002-2003, prior to the opening of the new facility. The 2019 film '' Where'd You Go, Bernadette'' features the station prominently and includes scenes of its construction at the closing credits, although the actual station depicted in the film is Halley VI British Antarctic Research Station.

South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is the point in the Southern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True South Pole to distinguish ...

of the Earth. It is the southernmost point under the jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' and 'speech' or 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, the concept of jurisdiction applies at multiple level ...

(not sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

) of the United States. The station is located on the high plateau

In geology and physical geography, a plateau (; ; : plateaus or plateaux), also called a high plain or a tableland, is an area of a highland consisting of flat terrain that is raised sharply above the surrounding area on at least one side. ...

of Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

at above sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an mean, average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal Body of water, bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical ...

. It is administered by the Office of Polar Programs of the National Science Foundation

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) is an Independent agencies of the United States government#Examples of independent agencies, independent agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government that su ...

, specifically the United States Antarctic Program

The United States Antarctic Program (or USAP; formerly known as the United States Antarctic Research Program or USARP and the United States Antarctic Service or USAS) is an organization of the United States government which has a presence in the ...

(USAP). It is named in honor of Norwegian Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegians, Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Am ...

and Briton Robert F. Scott, leaders of the competing first and second expeditions to reach the pole, in the summer of 1911–1912.

The original Amundsen–Scott Station was built by Navy Seabees for the federal government of the United States

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the Federation#Federal governments, national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct ...

during November 1956, as part of its commitment to the scientific

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

goals of the International Geophysical Year

The International Geophysical Year (IGY; ), also referred to as the third International Polar Year, was an international scientific project that lasted from 1 July 1957 to 31 December 1958. It marked the end of a long period during the Cold War w ...

, an effort lasting from January 1957 to June 1958 to study, among other things, the geophysics

Geophysics () is a subject of natural science concerned with the physical processes and Physical property, properties of Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis. Geophysicists conduct i ...

of the polar regions of Earth

The polar regions, also called the frigid zones or polar zones, of Earth are Earth's polar ice caps, the regions of the planet that surround its geographical poles (the North and South Poles), lying within the polar circles. These high latitud ...

.

Before November 1956, there was no permanent artificial structure at the pole, and practically no human presence in the interior of Antarctica. The few scientific stations in Antarctica were near its coast. The station has been continuously occupied since it was built and has been rebuilt, expanded, and upgraded several times.

The station is the only inhabited place on the surface of the Earth from which the Sun is continuously visible for six months; it is then continuously dark for the next six months, with approximately two days of averaged dark and light, twilight, namely the equinoxes. These are, in observational terms, called one extremely long "day" and one equally long "night". During the six-month "day", the angle of elevation of the Sun above the horizon

The horizon is the apparent curve that separates the surface of a celestial body from its sky when viewed from the perspective of an observer on or near the surface of the relevant body. This curve divides all viewing directions based on whethe ...

varies incrementally. The Sun reaches a rising position throughout the September equinox

The September equinox (or southward equinox) is the moment when the Sun appears to cross the celestial equator, heading southward. Because of differences between the calendar year and the tropical year, the September equinox may occur from ...

, and then it is apparent highest at the December solstice

The December solstice, also known as the southern solstice, is the solstice that occurs each December – typically on 21 December, but may vary by one day in either direction according to the Gregorian calendar. In the Northern Hemisphere, the ...

which is summer solstice

The summer solstice or estival solstice occurs when one of Earth's poles has its maximum tilt toward the Sun. It happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere ( Northern and Southern). The summer solstice is the day with the longest peri ...

for the south, setting on the March equinox

The March equinox or northward equinox is the equinox on the Earth when the subsolar point appears to leave the Southern Hemisphere and cross the celestial equator, heading northward as seen from Earth. The March equinox is known as the ver ...

.

During the six-month polar night, air temperatures can drop below and blizzard

A blizzard is a severe Winter storm, snowstorm characterized by strong sustained winds and low visibility, lasting for a prolonged period of time—typically at least three or four hours. A ground blizzard is a weather condition where snow th ...

s are more frequent. Between these storms, and regardless of the weather for wavelengths unaffected by drifting snow, the roughly months of ample darkness and dry atmosphere make the station an excellent site for astronomical observation

Observational astronomy is a division of astronomy that is concerned with recording data about the observable universe, in contrast with theoretical astronomy, which is mainly concerned with calculating the measurable implications of physical ...

s.

The number of scientific researchers and members of the support staff housed at the Amundsen–Scott Station has always varied seasonally, with a peak population of around 150 in the summer operational season from October to February. In recent years, the wintertime population has been around 50 people. Supplies come seasonally, during the warm season by Air or by the South Pole Traverse after it is opened; this traverse links the station to Scott Base and McMurdo Station

McMurdo Station is an American Antarctic research station on the southern tip of Ross Island. It is operated by the United States through the United States Antarctic Program (USAP), a branch of the National Science Foundation. The station is ...

on Ross Island

Ross Island is an island in Antarctica lying on the east side of McMurdo Sound and extending from Cape Bird in the north to Cape Armitage in the south, and a similar distance from Cape Royds in the west to Cape Crozier in the east.

The isl ...

since 2005 and reduces the amount of flights in. Much of the logistical support for the South Pole Station flows through McMurdo which has the farthest south port, Winter's Bay.

Background

For the International Geophysical Year, the United States and many other countries embarked on an international exploration of the South Pole. This led to the USA creating a series of stations for this project, and returning to the South Pole. After a few years the Antarctic treaty was established that provided an international framework for the exploration and study of Antarctica.

In October 1956, a U.S. Navy R4D-5L named ''Que Sera Sera'' (One of the many versions of the DC-3) landed at the South Pole in Antarctica. This was the first time humans had been at the pole since 1912 (see Robert F. Scott's British Antarctic Expedition).

South Pole station was one of seven bases that the United States built for the

For the International Geophysical Year, the United States and many other countries embarked on an international exploration of the South Pole. This led to the USA creating a series of stations for this project, and returning to the South Pole. After a few years the Antarctic treaty was established that provided an international framework for the exploration and study of Antarctica.

In October 1956, a U.S. Navy R4D-5L named ''Que Sera Sera'' (One of the many versions of the DC-3) landed at the South Pole in Antarctica. This was the first time humans had been at the pole since 1912 (see Robert F. Scott's British Antarctic Expedition).

South Pole station was one of seven bases that the United States built for the International Geophysical Year

The International Geophysical Year (IGY; ), also referred to as the third International Polar Year, was an international scientific project that lasted from 1 July 1957 to 31 December 1958. It marked the end of a long period during the Cold War w ...

, which also included McMurdo, Hallett, Wilkes, Byrd Station

The Byrd Station is a former research station established by the United States during the International Geophysical Year by U.S. Navy Seabees during Operation Deep Freeze II in West Antarctica. It was a year-round base until 1972, and then se ...

, Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station (South Pole Station), Ellsworth, and Little America.

Operation Deep Freeze

Operation Deep Freeze is the code name for a series of United States missions to Antarctica, beginning with "Operation Deep Freeze I" in 1955–56, followed by "Operation Deep Freeze II", "Operation Deep Freeze III", and so on. (There was an init ...

missions support the construction and operation of the South Pole station, starting with Operation Deep Freeze 1955, and succeeded by "Operation Deep Freeze II", and so on. In 1960, the year of the fifth mission, codenames began to be based on the year (e.g., "Operation Deep Freeze 60").

Structures

Original station (1957–2010)

The original South Pole station is now referred to as "Old Pole". The station was constructed by U.S. NavySeabee

United States Naval Construction Battalions, better known as the Navy Seabees, form the U.S. Naval Construction Forces (NCF). The Seabee nickname is a heterograph of the initial letters "CB" from the words "Construction Battalion". Dependi ...

s led by LTJG Richard Bowers, the eight-man Advance Party being transported by the VX-6 Air Squadron in two R4Ds on November 20, 1956. The U.S. Eighteenth Air Force's C-124 Globemaster IIs airdrop

An airdrop is a type of airlift in which items including weapons, equipment, humanitarian aid or leaflets are delivered by military or civilian aircraft without their landing. Developed during World War II to resupply otherwise inaccessible tr ...

ped most of the equipment and building material. The buildings were constructed from prefabricated

Prefabrication is the practice of assembling components of a structure in a factory or other manufacturing site, and transporting complete assemblies or sub-assemblies to the construction site where the structure is to be located. Some research ...

four-by-eight-foot modular panels. Exterior surfaces were thick, with an aluminum interior surface, and a plywood exterior surface, sandwiching fiberglass

Fiberglass (American English) or fibreglass (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English) is a common type of fibre-reinforced plastic, fiber-reinforced plastic using glass fiber. The fibers may be randomly arranged, flattened i ...

. Skylights were the only windows in flat uniform roof levels, while buildings were connected by a burlap and chicken wire

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domesticated subspecies of the red junglefowl (''Gallus gallus''), originally native to Southeast Asia. It was first domesticated around 8,000 years ago and is now one of the most common and ...

covered tunnel system. The last of the construction crew departed on January 4, 1957. The first wintering-over party consisted of eight IGY scientists led by Paul Siple and eight Navy support men led by LTJG John Tuck. Key components of the camp included an astronomical observatory, a Rawin Tower, a weather balloon

A weather balloon, also known as a sounding balloon, is a balloon (specifically a type of high-altitude balloon) that carries instruments to the stratosphere to send back information on atmospheric pressure, temperature, humidity and wind spe ...

inflation shelter, and a snow tunnel with pits for a seismometer

A seismometer is an instrument that responds to ground displacement and shaking such as caused by quakes, volcanic eruptions, and explosions. They are usually combined with a timing device and a recording device to form a seismograph. The out ...

and magnetometer

A magnetometer is a device that measures magnetic field or magnetic dipole moment. Different types of magnetometers measure the direction, strength, or relative change of a magnetic field at a particular location. A compass is one such device, ...

. The lowest average temperatures recorded by the group were in the range to , though as Siple points out, "even at I had seen men spitting blood because the capillaries

A capillary is a small blood vessel, from 5 to 10 micrometres in diameter, and is part of the microcirculation system. Capillaries are microvessels and the smallest blood vessels in the body. They are composed of only the tunica intima (the in ...

of the bronchial

A bronchus ( ; : bronchi, ) is a passage or airway in the lower respiratory tract that conducts Atmosphere of Earth, air into the lungs. The first or primary bronchi to branch from the trachea at the Carina of trachea, carina are the right main b ...

tract frosted".

On January 3, 1958, Sir Edmund Hillary

Sir Edmund Percival Hillary (20 July 1919 – 11 January 2008) was a New Zealand mountaineering, mountaineer, explorer, and philanthropist. On 29 May 1953, Hillary and Sherpa people, Sherpa mountaineer Tenzing Norgay became the Timeline of M ...

's team from New Zealand, part of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, reached the station over land from Scott Base, followed shortly by Sir Vivian Fuchs' British scientific component.

The buildings of Old Pole were assembled from prefabricated components delivered to the South Pole by air and airdropped. They were originally built on the surface, with covered wood-framed walkways connecting the buildings. Although snow accumulation in open areas at the South Pole is approximately per year, wind-blown snow accumulates much more quickly in the vicinity of raised structures. By 1960, three years after the construction of the station, it had already been buried by of snow.

The station was abandoned in 1975 and became deeply buried, with the pressure causing the mostly wooden roof to cave in. The station was demolished in December 2010, after an equipment operator fell through the structure doing snow stability testing for the National Science Foundation (NSF). The area was being vetted for use as a campground for NGO guests.

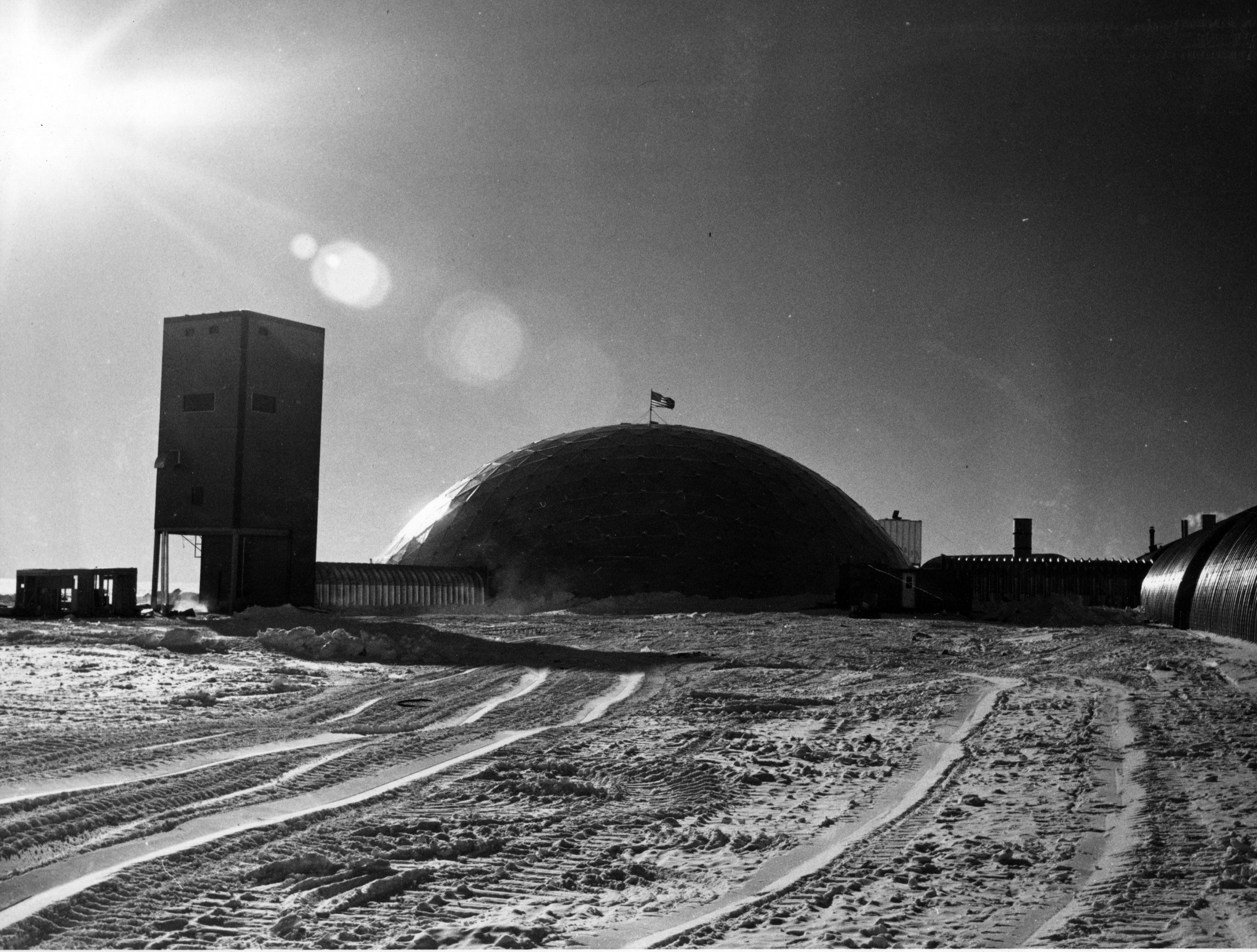

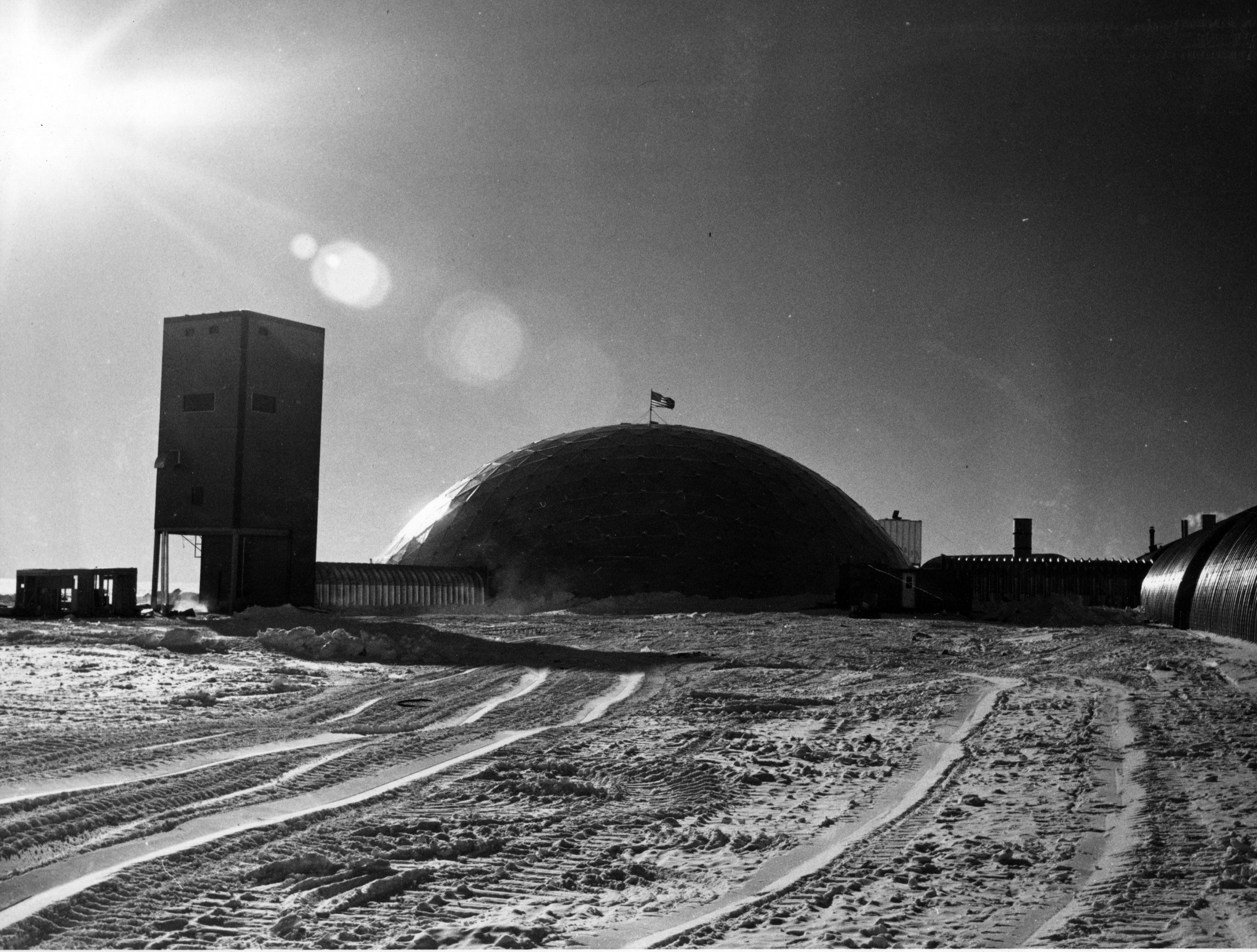

Dome (1975–2010)

The station was moved in 1975 to the newly constructed

The station was moved in 1975 to the newly constructed Buckminster Fuller

Richard Buckminster Fuller (; July 12, 1895 – July 1, 1983) was an American architect, systems theorist, writer, designer, inventor, philosopher, and futurist. He styled his name as R. Buckminster Fuller in his writings, publishing more t ...

geodesic dome

A geodesic dome is a hemispherical thin-shell structure (lattice-shell) based on a geodesic polyhedron. The rigid triangular elements of the dome distribute stress throughout the structure, making geodesic domes able to withstand very heavy ...

wide by high, with steel archways. One served as the entry to the dome and it had a transverse arch that contained modular building

A modular building is a prefabricated building that consists of repeated sections called modules. Modularity involves constructing sections away from the building site, then delivering them to the intended site. Installation of the prefabricate ...

s for the station's maintenance, fuel bladders, power plant, snow melter, equipment and vehicles. Individual buildings within the dome contained the dorms, galley, recreational center, post office and labs for monitoring the upper and lower atmosphere and numerous other complex projects in astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

and astrophysics

Astrophysics is a science that employs the methods and principles of physics and chemistry in the study of astronomical objects and phenomena. As one of the founders of the discipline, James Keeler, said, astrophysics "seeks to ascertain the ...

. The station also included the Skylab, a box-shaped tower slightly taller than the dome. Skylab was connected to the Dome by a tunnel. The Skylab housed atmospheric sensor equipment and later a music room.

During the 1970–1974 summers, the Seabees constructing the dome were housed in Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

era Jamesway huts. A hut consists of a wooden frame with a raised platform covered by canvas tarp. A double-doored vestibule was at each end. Although heated, the heat was not sufficient to keep them habitable during the winter. After several burned during the 1976–1977 summer, the construction camp was abandoned and later removed.

However, in the 1981–1982 season, extra civilian seasonal personnel were housed in a group of Jamesways known as the "summer camp". Initially consisting of only two huts, the camp grew to 11 huts housing about 10 people each, plus two recreational huts with bathroom and gym facilities. In addition, a number of science and berthing structures, such as the hypertats and elevated dormitory, were added in the 1990s, particularly for astronomy and astrophysics.

During the period in which the dome served as the main station, many changes to United States South Pole operation took place. From the 1990s on, astrophysical research conducted at the South Pole took advantage of its favorable atmospheric conditions and began to produce important scientific results. Such experiments include the Python, Viper

Vipers are snakes in the family Viperidae, found in most parts of the world, except for Antarctica, Australia, Hawaii, Madagascar, New Zealand, Ireland, and various other isolated islands. They are venomous and have long (relative to non-vipe ...

, and DASI telescopes, as well as the South Pole Telescope. The DASI telescope has since been decommissioned and its mount used for the Keck Array

BICEP (Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization) and the Keck Array are a series of cosmic microwave background (CMB) experiments. They aim to measure the polarization of the CMB; in particular, measuring the ''B''-mode of the CMB ...

. The AMANDA / IceCube experiment makes use of the two-mile (3 km)-thick ice sheet to detect neutrino

A neutrino ( ; denoted by the Greek letter ) is an elementary particle that interacts via the weak interaction and gravity. The neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass is so small ('' -ino'') that i ...

s which have passed through the earth. An observatory building, the Martin A. Pomerantz Observatory (MAPO), was dedicated in 1995. The importance of these projects changed the priorities in station operation, increasing the status of scientific cargo and personnel.

The 1998–1999 summer season was the last year that VXE-6 with its Lockheed LC-130s serviced the U.S. Antarctic Program. Beginning in 1999–2000, the New York Air National Guard 109th Airlift Wing took responsibility for the daily cargo and passenger flights between McMurdo Station

McMurdo Station is an American Antarctic research station on the southern tip of Ross Island. It is operated by the United States through the United States Antarctic Program (USAP), a branch of the National Science Foundation. The station is ...

and the South Pole during the summer.

During the winter of 1988 a loud crack was heard in the dome. Upon investigation it was discovered that the foundation base ring beams were broken due to being overstressed.

The dome was dismantled in late 2009. It was crated and given to the Seabees. As of 2025, the dome pieces are stored at Port Hueneme, California. The center oculus is suspended in a display at the Seabee Museum there.

geodesic dome

A geodesic dome is a hemispherical thin-shell structure (lattice-shell) based on a geodesic polyhedron. The rigid triangular elements of the dome distribute stress throughout the structure, making geodesic domes able to withstand very heavy ...

ramped down from the surface level. The base of the dome was originally at the surface level of the ice cap, but the base had been slowly buried by snow and ice.

File:pole-from-air.jpg, An aerial view of the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station taken in about 1983. The central dome is shown along with the arches, with various storage buildings, and other auxiliary buildings such as garages and hangars.

File:South Pole Dome From Station.JPG, The dome in January 2009, as seen from the new elevated station.

Image:Ceremonial South Pole.jpg, Ceremonial South Pole in 1999 (the dome in the background was dismantled in 2009–2010).

File:South pole dome deconstruction.jpeg, January 2010: The last section of the old dome, before it was removed the next day.

Elevated station (2008–present)

In 1992, the design of a new station began for an building with two floor levels that costUS$

The United States dollar (Currency symbol, symbol: Dollar sign, $; ISO 4217, currency code: USD) is the official currency of the United States and International use of the U.S. dollar, several other countries. The Coinage Act of 1792 introdu ...

150 million. Construction began in 1999, adjacent to the Dome. The facility was officially dedicated on January 12, 2008, with a ceremony that included the de-commissioning of the old Dome station. The ceremony was attended by a number of dignitaries flown in specifically for the day, including National Science Foundation

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) is an Independent agencies of the United States government#Examples of independent agencies, independent agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government that su ...

Director Arden Bement, scientist Susan Solomon and other government officials. The entirety of building materials to complete the build of the new South Pole Station were flown in from McMurdo Station by the LC-130 Hercules aircraft and the 139th Airlift Squadron Stratton Air National Guard Base, Scotia, New York. Each plane brought of cargo each flight with the total weight of the building material being .

The new station included a modular design, to accommodate rises in population, and an adjustable elevation

The elevation of a geographic location (geography), ''location'' is its height above or below a fixed reference point, most commonly a reference geoid, a mathematical model of the Earth's sea level as an equipotential gravitational equipotenti ...

to prevent it from being buried in snow. Since roughly of snow accumulates every year without ever thawing, the building's designers included rounded corners and edges around the structure to help reduce snow drifts. The building faces into the wind with a sloping lower portion of wall. The angled wall increases the wind speed as it flows under the buildings, and passes above the snow-pack, causing the snow to be scoured away. This prevents the building from being quickly buried. Wind tunnel tests show that scouring will continue to occur until the snow level reaches the second floor.

Because snow gradually settles over time under its own weight, the foundations of the building were designed to accommodate substantial differential settling over any one wing in any one line or any one column. If differential settling continues, the supported structure will need to be jacked up and re-leveled. The facility was designed with the primary support columns outboard of the exterior walls so that the entire building can be jacked up a full floor level. During this process, a new section of column will be added over the existing columns then the jacks pull the building up to the higher elevation.

electric power

Electric power is the rate of transfer of electrical energy within a electric circuit, circuit. Its SI unit is the watt, the general unit of power (physics), power, defined as one joule per second. Standard prefixes apply to watts as with oth ...

plant is in the center, and the old vehicle mechanic's garage in the lower right. The green light in the sky is part of the aurora australis.

Operation

During the summer the station population is typically around 150. Most personnel leave by the middle of February, leaving a few dozen (39 in 2021) "winter-overs", mostly support staff plus a few scientists, who keep the station functional through the months of Antarctic night. The winter personnel are isolated between mid-February and late October. Wintering-over presents notorious dangers and stresses, as the station population is almost totally isolated. The station is completely self-sufficient during the winter, and powered by three generators running onJP-8

JP-8, or JP8 (for "Jet Propellant 8"), is a jet fuel, specified and used widely by the US military. It is specified by MIL-DTL-83133 and British Defence Standard 91-87, and similar to commercial aviation's Jet A-1, but with the addition of corros ...

jet fuel. An annual tradition is a back-to-back-to-back viewing of ''The Thing from Another World'' (1951), ''The Thing'' (1982), and ''The Thing'' (2011) after the last flight has left for the winter.

Research at the station includes glaciology

Glaciology (; ) is the scientific study of glaciers, or, more generally, ice and natural phenomena that involve ice.

Glaciology is an interdisciplinary Earth science that integrates geophysics, geology, physical geography, geomorphology, clim ...

, geophysics

Geophysics () is a subject of natural science concerned with the physical processes and Physical property, properties of Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis. Geophysicists conduct i ...

, meteorology

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth's atmosphere and short-term atmospheric phenomena (i.e. weather), with a focus on weather forecasting. It has applications in the military, aviation, energy production, transport, agricultur ...

, upper atmosphere physics, astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, astrophysics

Astrophysics is a science that employs the methods and principles of physics and chemistry in the study of astronomical objects and phenomena. As one of the founders of the discipline, James Keeler, said, astrophysics "seeks to ascertain the ...

, and biomedical

Biomedicine (also referred to as Western medicine, mainstream medicine or conventional medicine)

studies. In recent years, most of the winter scientists have worked for the IceCube Neutrino Observatory

The IceCube Neutrino Observatory (or simply IceCube) is a neutrino observatory developed by the University of Wisconsin–Madison and constructed at the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica. The project is a recognized CERN experime ...

or for low-frequency astronomy experiments such as the South Pole Telescope and BICEP2. The low temperature and low moisture content of the polar air, combined with the altitude of over , causes the air to be far more transparent on some frequencies than is typical elsewhere, and the months of darkness permit sensitive equipment to run constantly.

There is a small greenhouse at the station. The variety of vegetables and herbs in the greenhouse, which range from fresh eggplant

Eggplant (American English, US, Canadian English, CA, Australian English, AU, Philippine English, PH), aubergine (British English, UK, Hiberno English, IE, New Zealand English, NZ), brinjal (Indian English, IN, Singapore English, SG, Malays ...

to jalapeños, are all produced hydroponically, using only water and nutrients and no soil. The greenhouse is the only source of fresh fruit and vegetables during the winter.

Transportation

The station has a runway for aircraft , long. Between October and February, there are several flights per day of U.S. Air Force ski-equipped Lockheed LC-130 Hercules aircraft from the New York Air National Guard, 109 AW, 139AS Stratton Air National Guard viaMcMurdo Station

McMurdo Station is an American Antarctic research station on the southern tip of Ross Island. It is operated by the United States through the United States Antarctic Program (USAP), a branch of the National Science Foundation. The station is ...

to supply the station. Resupply missions are collectively termed Operation Deep Freeze

Operation Deep Freeze is the code name for a series of United States missions to Antarctica, beginning with "Operation Deep Freeze I" in 1955–56, followed by "Operation Deep Freeze II", "Operation Deep Freeze III", and so on. (There was an init ...

.

There is a snow road over the ice sheet from McMurdo, the McMurdo-South Pole highway, which is long.

Communication

Data access to the station is provided by

Data access to the station is provided by NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

's TDRS-4 (non operational), 5 (not radio link to 90°), and 6 (not radio link to 90°) satellites: the DOD DSCS-3 satellite, and the commercial Iridium satellite constellation

The Iridium satellite constellation provides L band voice and data information Pass (spaceflight), coverage to satellite phones, satellite messenger communication devices and integrated transceivers. Iridium Communications owns and operates the ...

. For the 2007–2008 season, the TDRS relay (named South Pole TDRSS Relay or SPTR) was upgraded to support a data return rate of 50 Mbit/s

In telecommunications, data transfer rate is the average number of bits (bitrate), characters or symbols (baudrate), or data blocks per unit time passing through a communication link in a data-transmission system. Common data rate units are multi ...

, which comprises over 90% of the data return capability. The TDRS-1 satellite formerly provided services to the station, but it failed in October 2009 and was subsequently decommissioned. Marisat

Marisat satellites were the first mobile telecommunications satellites and were designed to provide dependable telecommunications for commercial shipping and the U.S. Navy from stable geosynchronous orbital locations over the three major ocean r ...

and LES9 were also formerly used. In July 2016, the GOES-3 satellite was decommissioned due to it nearing the end of its supply of propellant and was replaced by the use of the DSCS-3 satellite, a military communications satellite. DSCS-3 can provide a 30 MB/s data rate compared to GOES-3's 1.5 MB/s. DSCS-3 and TDRS-4, 5, and 6 are used together to provide the main communications capability for the station. These satellites provide the data uplink for the station's scientific data as well as provide broadband internet and telecommunications access. Only during the main satellite events is the station's telephone system able to dial out. The commercial Iridium satellite is used when the TDRS and DSCS satellites are all out of range to give the station limited communications capability during those times. During those times, telephone calls may only be made on several Iridium satellite telephone sets owned by the station. The station's IT system also has a limited data uplink over the Iridium network, which allows emails less than 100 KB to be sent and received at all times and small critical data files to be transmitted. This uplink works by bonding the data stream over 12 voice channels. Non-commercial and non-military communication has been provided by amateur ham radio

Amateur radio, also known as ham radio, is the use of the radio frequency spectrum for purposes of non-commercial exchange of messages, wireless experimentation, self-training, private recreation, radiosport, contesting, and emergency communi ...

using primarily HF SSB links today but Morse code

Morse code is a telecommunications method which Character encoding, encodes Written language, text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code i ...

and other modes have been used, partly in experiments and mainly in bolstering esprit de corps

Morale ( , ) is the capacity of a group's members to maintain belief in an institution or goal, particularly in the face of opposition or hardship. Morale is often referenced by authority figures as a generic value judgment of the willpower ...

and hobby-type uses. The USA sector has the amateur radio call sign prefix run of KC4 and AT; whereas Soviet/Russian stations are known to use 4K1 and others. The popularity of the hobby during the 1950-80s era saw many ham exchanges between South Polar ham stations and enthusiastic ham operators contacting there from world-wide locations. Over the years, ham radio has established needed emergency communication to Polar base personnel as well as recreational uses.

Astrophysics experiments at the station

Cosmic Microwave Background Telescopes

* Python Telescope (1992–1997), used to observe temperature anisotropies in the

Cosmic Microwave Background Telescopes

* Python Telescope (1992–1997), used to observe temperature anisotropies in the cosmic microwave background

The cosmic microwave background (CMB, CMBR), or relic radiation, is microwave radiation that fills all space in the observable universe. With a standard optical telescope, the background space between stars and galaxies is almost completely dar ...

(CMB).

* Viper telescope (1997–2000), used to observe temperature anisotropies in the CMB. Was refitted with the ACBAR bolometer (2000-2008).

* DASI (1999–2000), used to measure the temperature and power spectrum of the CMB.

* The QUaD

QUaD, an acronym for QUEST at DASI, was a ground-based cosmic microwave background (CMB) polarization experiment at the South Pole. QUEST (Q and U Extragalactic Sub-mm Telescope) was the original name attributed to the bolometer detector instrume ...

(2004–2009), used the DASI mount, used to make detailed observations of CMB polarization.

* The BICEP1 (2006–2008) and BICEP2 (2010–2012) instruments were also used to observe polarization anisotropies in the CMB. BICEP3 was installed in 2015.

* South Pole Telescope (2007–present), used to survey the CMB to look for distant galaxy cluster

A galaxy cluster, or a cluster of galaxies, is a structure that consists of anywhere from hundreds to thousands of galaxies that are bound together by gravity, with typical masses ranging from 1014 to 1015 solar masses. Clusters consist of galax ...

s.

* The Keck Array

BICEP (Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization) and the Keck Array are a series of cosmic microwave background (CMB) experiments. They aim to measure the polarization of the CMB; in particular, measuring the ''B''-mode of the CMB ...

(2010–present), using the DASI mount, is now used to continue work on the polarization anisotropies of the CMB.

Neutrino Experiments

* AMANDA (1997–2009) was an experiment to detect neutrinos.

* IceCube (2010–present) is an experiment to detect neutrinos.

* Radio Ice Cherenkov Experiment or RICE (1999–2012), an experiment to detect ultra high energy (UHE) neutrinos.

* Neutrino Array Radio Calibration or NARC (2008–2012), an upgrade of the RICE experiment.

* Askaryan Radio Array or ARA (2011–present), a successor of RICE, currently (as of 2022) under construction.

Climate

Typical of inland Antarctica, Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station experiences anice cap climate

An ice cap climate is a polar climate where no mean monthly temperature exceeds . The climate generally covers areas at high altitudes and Polar regions of Earth, polar regions (60–90° north and south latitude), such as Antarctica and some of ...

('' EF'') with BWk precipitation patterns. The peak season of summer lasts from December to mid February.

At the Amundsen–Scott the average annual precipitation is approximately 50 millimeters (2 inches), primarily falling as snow. This low level of precipitation is characteristic of the Antarctic interior, where the combination of extremely low temperatures and limited moisture in the atmosphere results in an extremely arid climate with minimal snowfall.

Media and events

In 1991,Michael Palin

Sir Michael Edward Palin (; born 5 May 1943) is an English actor, comedian, writer, and television presenter. He was a member of the Monty Python comedy group. He received the BAFTA Academy Fellowship Award, BAFTA Fellowship in 2013 and was knig ...

visited the base on the eighth and final episode of his BBC Television documentary, '' Pole to Pole''.

On January 10, 1995, NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

, PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

, and NSF collaborated for the first live television broadcast from the South Pole, titled ''Spaceship South Pole''. During this interactive broadcast, students from several schools in the United States asked the scientists at the station questions about their work and conditions at the pole.

In 1999, CBS News correspondent Jerry Bowen reported on camera in a talkback with anchors from the Saturday edition of ''CBS This Morning''.

In 1999, the winter-over physician, Jerri Nielsen, found that she had breast cancer

Breast cancer is a cancer that develops from breast tissue. Signs of breast cancer may include a Breast lump, lump in the breast, a change in breast shape, dimpling of the skin, Milk-rejection sign, milk rejection, fluid coming from the nipp ...

. She had to rely on self-administered chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (often abbreviated chemo, sometimes CTX and CTx) is the type of cancer treatment that uses one or more anti-cancer drugs (list of chemotherapeutic agents, chemotherapeutic agents or alkylating agents) in a standard chemotherapy re ...

, using supplies from a daring July cargo drop, then was picked up in an equally dangerous mid-October landing.

On May 11, 2000, astrophysicist Rodney Marks became ill while walking between the remote observatory and the base. He became increasingly sick over 36 hours, three times returning increasingly distressed to the station's doctor. Advice was sought by satellite, but Marks died on May 12, 2000, with his condition undiagnosed. The National Science Foundation issued a statement that Rodney Marks had "apparently died of natural causes, but the specific cause of death had yet to be determined". The exact cause of Marks' death could not be determined until his body was removed from Amundsen–Scott Station and flown off Antarctica for an autopsy

An autopsy (also referred to as post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of deat ...

. Marks' death was due to methanol

Methanol (also called methyl alcohol and wood spirit, amongst other names) is an organic chemical compound and the simplest aliphatic Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol, with the chemical formula (a methyl group linked to a hydroxyl group, often ab ...

poisoning, and the case received media attention as the "first South Pole murder", although there is no evidence that Marks died as the result of the act of another person.

On 26 April 2001, Kenn Borek Air used a DHC-6 Twin Otter aircraft to rescue Dr. Ronald Shemenski from Amundsen–Scott. This was the first ever rescue from the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is the point in the Southern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True South Pole to distinguish ...

during polar winter. To achieve the range necessary for this flight, the Twin Otter was equipped with a special ferry tank.

In January 2007, the station was visited by a group of high-level Russian officials, including FSB chiefs Nikolai Patrushev and Vladimir Pronichev. The expedition, led by polar explorer Artur Chilingarov

Artur Nikolaevich Chilingarov (; 25 September 1939 – 1 June 2024) was an Armenian-Russian polar explorer, a corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. He was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union in 1986 and the title of ...

, started from Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

on two Mi-8 helicopters and landed at the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is the point in the Southern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True South Pole to distinguish ...

.

On September 6, 2007, The National Geographic Channel

National Geographic (formerly National Geographic Channel; abbreviated and trademarked as Nat Geo or Nat Geo TV) is an American pay television network and flagship channel owned by the National Geographic Global Networks unit of Disney Enter ...

's television show ''Man Made'' aired an episode on the construction of their new facility.

On November 9, 2007, edition of NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a subsidiary of Comcast. It is one of NBCUniversal's ...

's ''Today

Today (archaically to-day) may refer to:

* The current day and calendar date

** Today is between and , subject to the local time zone

* Now, the time that is perceived directly, present

* The current, present era

Arts, entertainment and m ...

'', show co-anchor Ann Curry

Ann Curry (born November 19, 1956) is an American journalist, who has been a reporter for more than 45 years, focused on human suffering in war zones and natural disasters. Curry has reported from the wars in Kosovo, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Palest ...

made a satellite telephone call which was broadcast live from the South Pole.

On Christmas 2007, two employees at the base got into a fight and had to be evacuated.

On July 11, 2011, the winter-over communications technician fell ill and was diagnosed with appendicitis

Appendicitis is inflammation of the Appendix (anatomy), appendix. Symptoms commonly include right lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever and anorexia (symptom), decreased appetite. However, approximately 40% of people do not have these t ...

. An emergency open appendectomy

An appendectomy (American English) or appendicectomy (British English) is a Surgery, surgical operation in which the vermiform appendix (a portion of the intestine) is removed. Appendectomy is normally performed as an urgent or emergency procedur ...

was performed by the station doctors with several winter-overs assisting during the surgery.

The 2011 BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

TV programme '' Frozen Planet'' discusses the base and shows footage of the inside and outside of the elevated station in the "Last Frontier Episode".

During the 2011 winter-over season, station manager Renee-Nicole Douceur experienced a stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

on August 27, resulting in loss of vision and cognitive function. Because the Amundsen–Scott base lacks diagnostic medical equipment such as an MRI or CT scan machine, station doctors were unable to fully evaluate the damage done by the stroke or the chance of recurrence. Physicians on site recommended a medevac flight as soon as possible for Douceur, but offsite doctors hired by Raytheon Polar Services (the company contracted to run the base) and the National Science Foundation disagreed with the severity of the situation. The National Science Foundation, which is the final authority on all flights and assumes all financial responsibility for the flights, denied the request for medevac, saying the weather was still too hazardous. Plans were made to evacuate Douceur on the first flight available. Douceur and her niece, believing Douceur's condition to be grave and believing an earlier medevac flight possible, contacted Senator Jeanne Shaheen

Cynthia Jeanne Shaheen ( ; née Bowers, born January 28, 1947) is an American politician and former educator serving since 2009 as the Seniority in the United States Senate, senior United States Senate, United States senator from New Hampshire. A ...

for assistance; as the NSF continued to state Douceur's condition did not qualify for a medevac attempt and conditions at the base would not permit an earlier flight, Douceur and her supporters brought the situation to media attention. Douceur was evacuated, along with a doctor and an escort, on an October 17 cargo flight. This was the first flight available when the weather window opened up on October 16. This first flight is usually solely for supply and refueling of the station, and does not customarily accept passengers, as the plane's cabin is unpressurized. The evacuation was successful, and Douceur arrived in Christchurch

Christchurch (; ) is the largest city in the South Island and the List of cities in New Zealand, second-largest city by urban area population in New Zealand. Christchurch has an urban population of , and a metropolitan population of over hal ...

, New Zealand, at 10:55 p.m. She ultimately made a full recovery.

In March 2014, BICEP2 announced that they had detected B-modes from gravitational wave

Gravitational waves are oscillations of the gravitational field that Wave propagation, travel through space at the speed of light; they are generated by the relative motion of gravity, gravitating masses. They were proposed by Oliver Heaviside i ...

s generated in the early universe, supporting the inflation theory of cosmology. Later analysis showed that BICEP only saw polarized dust signal in the galaxy and not primordial B-modes.

On 20 June 2016, there was another medical evacuation of two personnel around midwinter day, again involving Kenn Borek Air and DHC-6 Twin Otter aircraft.

In December 2016, Buzz Aldrin

Buzz Aldrin ( ; born Edwin Eugene Aldrin Jr.; January 20, 1930) is an American former astronaut, engineer and fighter pilot. He made three extravehicular activity, spacewalks as pilot of the 1966 Gemini 12 mission, and was the Lunar Module Eag ...

was visiting the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station, Antarctica, as part of a tourist group, when he fell ill and was evacuated, first to McMurdo Station and from there to Christchurch, New Zealand, where he was reported to be in stable condition. Aldrin's visit at age 86 makes him the oldest person to ever reach the South Pole.

In the summer of 2016–17, Anthony Bourdain

Anthony Michael Bourdain ( ; June 25, 1956 – June 8, 2018) was an American celebrity chef, author and Travel documentary, travel documentarian. He starred in programs focusing on the exploration of international culture, cuisine, and the huma ...

filmed part of an episode of his television show '' Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown'' at the station.

In popular culture

Science and life at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole station is documented in Dr. John Bird's award-winning book, ''One Day, One Night: Portraits of the South Pole'' which chronicles the South Pole Foucault Pendulum, the 300 Club, the first midwinter medevac, and science at the Pole including climate change and cosmology.

Science fiction author

Science and life at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole station is documented in Dr. John Bird's award-winning book, ''One Day, One Night: Portraits of the South Pole'' which chronicles the South Pole Foucault Pendulum, the 300 Club, the first midwinter medevac, and science at the Pole including climate change and cosmology.

Science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson

Kim Stanley Robinson (born March 23, 1952) is an American science fiction writer best known for his ''Mars'' trilogy. Many of his novels and stories have ecological, cultural, and political themes and feature scientists as heroes. Robinson has ...

's book ''Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

'' features a fictionalized account of the culture at Amundsen–Scott and McMurdo, set in the near future.

The station is featured prominently in the 1998 ''The X-Files

''The X-Files'' is an American science fiction on television, science fiction drama (film and television), drama television series created by Chris Carter (screenwriter), Chris Carter. The original series aired from September 10, 1993, to Ma ...

'' film '' Fight the Future''.

The 2009 film '' Whiteout'' is mainly set at the Amundsen–Scott base, although the building layouts are completely different.

The turn-based strategy

Strategy video game is a major video game genre that focuses on analyzing and strategizing over direct quick reaction in order to secure success.

Although many types of video games can contain strategic elements, the strategy genre is most commo ...

game

A game is a structured type of play usually undertaken for entertainment or fun, and sometimes used as an educational tool. Many games are also considered to be work (such as professional players of spectator sports or video games) or art ...

''Civilization VI

''Sid Meier's Civilization VI'' is a 2016 4X turn-based strategy video game developed by Firaxis Games and published by 2K (company), 2K. The mobile and Nintendo Switch ports were published by Aspyr Media. It is the sequel to ''Civilization V'' ...

'', in its expansion '' Rise and Fall'', included the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station as a Wonder.

The anime

is a Traditional animation, hand-drawn and computer animation, computer-generated animation originating from Japan. Outside Japan and in English, ''anime'' refers specifically to animation produced in Japan. However, , in Japan and in Ja ...

OVA '' Mobile Suit Gundam: The Origin'' features a large city in Antarctica called Scott City under a Geodesic dome

A geodesic dome is a hemispherical thin-shell structure (lattice-shell) based on a geodesic polyhedron. The rigid triangular elements of the dome distribute stress throughout the structure, making geodesic domes able to withstand very heavy ...

not unlike the 1975 dome as the location of a major peace conference between the human space colonies controlled by Zeon and the Earth Federation.

The 2017 noveSouth Pole Station

by Ashley Shelby is set at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole station of 2002-2003, prior to the opening of the new facility. The 2019 film '' Where'd You Go, Bernadette'' features the station prominently and includes scenes of its construction at the closing credits, although the actual station depicted in the film is Halley VI British Antarctic Research Station.

Time zone

The South Pole sees the Sun rise andset

Set, The Set, SET or SETS may refer to:

Science, technology, and mathematics Mathematics

*Set (mathematics), a collection of elements

*Category of sets, the category whose objects and morphisms are sets and total functions, respectively

Electro ...

only once a year. Due to atmospheric refraction

Atmospheric refraction is the deviation of light or other electromagnetic wave from a straight line as it passes through the atmosphere due to the variation in air density as a function of height. This refraction is due to the velocity of light ...

, these do not occur exactly on the September equinox

The September equinox (or southward equinox) is the moment when the Sun appears to cross the celestial equator, heading southward. Because of differences between the calendar year and the tropical year, the September equinox may occur from ...

and the March equinox

The March equinox or northward equinox is the equinox on the Earth when the subsolar point appears to leave the Southern Hemisphere and cross the celestial equator, heading northward as seen from Earth. The March equinox is known as the ver ...

, respectively: the Sun is above the horizon for four days longer at each equinox. The place has no solar time

Solar time is a calculation of the passage of time based on the position of the Sun in the sky. The fundamental unit of solar time is the day, based on the synodic rotation period. Traditionally, there are three types of time reckoning based ...

; there is no daily maximum or minimum solar height above the horizon. The station uses New Zealand time (UTC+12 during standard time and UTC+13 during daylight saving time

Daylight saving time (DST), also referred to as daylight savings time, daylight time (Daylight saving time in the United States, United States and Daylight saving time in Canada, Canada), or summer time (British Summer Time, United Kingdom, ...

) since all flights to McMurdo station depart from Christchurch

Christchurch (; ) is the largest city in the South Island and the List of cities in New Zealand, second-largest city by urban area population in New Zealand. Christchurch has an urban population of , and a metropolitan population of over hal ...

and, therefore, all official travel from the pole goes through New Zealand.

The zone identifier in the IANA time zone database

The tz database is a collaborative compilation of information about the world's time zones and rules for observing daylight saving time, primarily intended for use with computer programs and operating systems. Paul Eggert has been its editor an ...

was the deprecated Antarctica/South_Pole. It now uses the Pacific/Auckland timezone.

See also

* Concordia Station * Kunlun Station *List of Antarctic field camps

Many research stations in Antarctica support satellite field camps which are, in general, seasonal camps. The type of field camp can vary – some are permanent structures used during the annual Antarctic summer, whereas others are little more tha ...

* List of Antarctic research stations

* Paul Siple

* Polheim, Amundsen's name for the first South Pole camp.

* Scott Base

* Vostok Station

References

External links

* * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station 1956 establishments in Antarctica Outposts of Antarctica United States Antarctic Program Antarctic Specially Managed Areas South Pole Amundsen's South Pole expedition Robert Falcon Scott