Aleister Crowley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

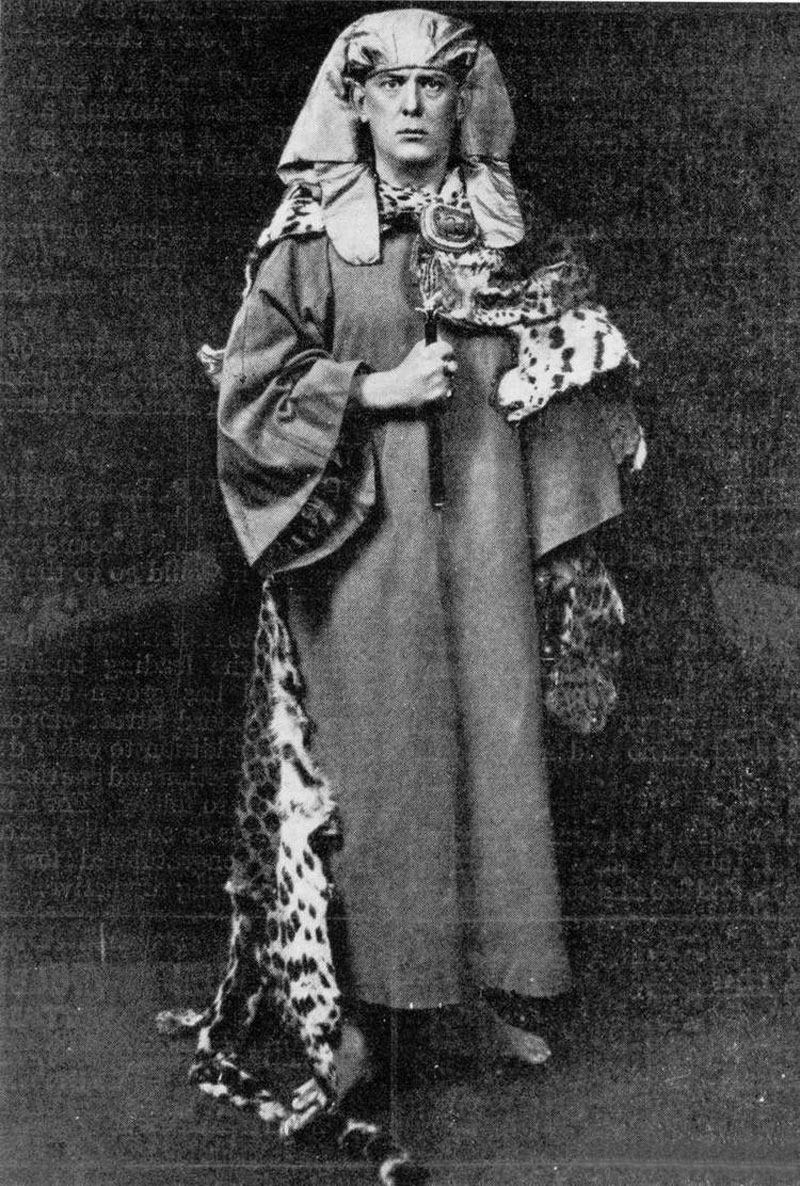

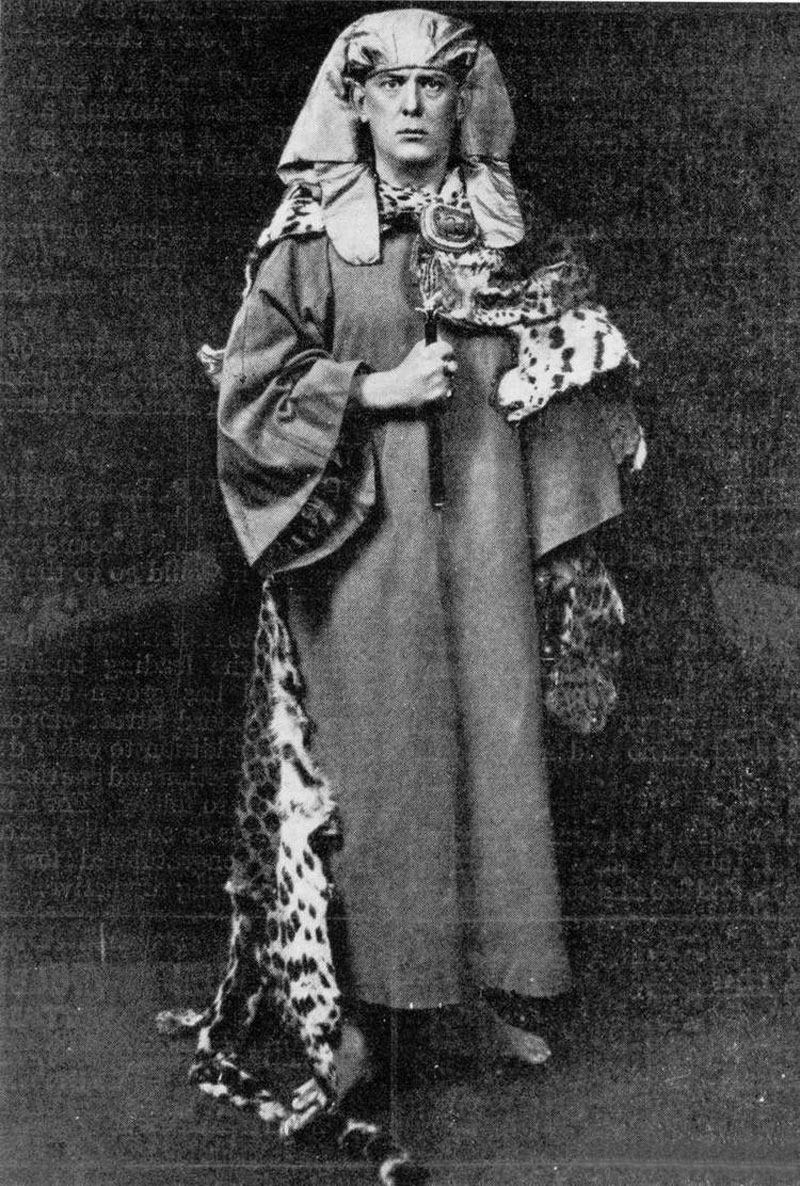

Aleister Crowley (; born Edward Alexander Crowley; 12 October 1875 – 1 December 1947) was an English

Crowley was born Edward Alexander Crowley at 30 Clarendon Square in Royal Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, on 12 October 1875. His father, Edward Crowley (1829–1887), was trained as an engineer, but his share in a lucrative family brewing business, Crowley's Alton Ales, had allowed him to retire before his son was born. His mother, Emily Bertha Bishop (1848–1917), came from a Devonshire-Somerset family and had a strained relationship with her son; she described him as "the Beast", a name that he revelled in. The couple had been married at London's Kensington Registry Office in November 1874, and were evangelical Christians. Crowley's father had been born a

Crowley was born Edward Alexander Crowley at 30 Clarendon Square in Royal Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, on 12 October 1875. His father, Edward Crowley (1829–1887), was trained as an engineer, but his share in a lucrative family brewing business, Crowley's Alton Ales, had allowed him to retire before his son was born. His mother, Emily Bertha Bishop (1848–1917), came from a Devonshire-Somerset family and had a strained relationship with her son; she described him as "the Beast", a name that he revelled in. The couple had been married at London's Kensington Registry Office in November 1874, and were evangelical Christians. Crowley's father had been born a

In August 1898, Crowley was in

In August 1898, Crowley was in

Briefly stopping in Japan and Hong Kong, Crowley reached Ceylon, where he met with Allan Bennett, who was there studying

Briefly stopping in Japan and Hong Kong, Crowley reached Ceylon, where he met with Allan Bennett, who was there studying

Crowley decided to climb Kanchenjunga in the Himalayas of Nepal, widely recognized as the world's most treacherous mountain. The collaboration between Jacot-Guillarmod, Charles Adolphe Reymond, Alexis Pache, and Alcesti C. Rigo de Righi,

Crowley decided to climb Kanchenjunga in the Himalayas of Nepal, widely recognized as the world's most treacherous mountain. The collaboration between Jacot-Guillarmod, Charles Adolphe Reymond, Alexis Pache, and Alcesti C. Rigo de Righi,

pp. 186–202

. During the trip he invoked the thirty aethyrs of Enochian magic, with Neuburg recording the results, later published in ''The Equinox'' as ''The Vision and the Voice''. Following a mountaintop sex magic ritual, Crowley also performed an evocation to the demon Choronzon involving

In early 1912, Crowley published ''

In early 1912, Crowley published ''

Professing to be of Irish ancestry and a supporter of Irish independence from Great Britain, Crowley began to espouse support for Germany in their war against Britain. He became involved in New York's pro-German movement, and in January 1915 German spy George Sylvester Viereck employed him as a writer for his propagandist paper, '' The Fatherland'', which was dedicated to keeping the US neutral in the conflict. In later years, detractors denounced Crowley as a traitor to Britain for this action.

Crowley entered into a relationship with Jeanne Robert Foster, with whom he toured the West Coast. In

Professing to be of Irish ancestry and a supporter of Irish independence from Great Britain, Crowley began to espouse support for Germany in their war against Britain. He became involved in New York's pro-German movement, and in January 1915 German spy George Sylvester Viereck employed him as a writer for his propagandist paper, '' The Fatherland'', which was dedicated to keeping the US neutral in the conflict. In later years, detractors denounced Crowley as a traitor to Britain for this action.

Crowley entered into a relationship with Jeanne Robert Foster, with whom he toured the West Coast. In  In December, he moved to

In December, he moved to

occultist

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism ...

, ceremonial magic

Ceremonial magic (ritual magic, high magic or learned magic) encompasses a wide variety of rituals of Magic (supernatural), magic. The works included are characterized by ceremony and numerous requisite accessories to aid the practitioner. I ...

ian, poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems ( oral or wr ...

, painter

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the "matrix" or "support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and ...

, novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living wage, living writing novels and other fiction, while othe ...

, and mountaineer

Mountaineering or alpinism, is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending tall mountains. Mountaineering-related activities include traditional outdoor climbing, skiing, and traversing via ferratas. Indoor climbing, sport climbing, an ...

. He founded the religion of Thelema

Thelema () is a Western esoteric and occult social or spiritual philosophy and new religious movement founded in the early 1900s by Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), an English writer, mystic, occultist, and ceremonial magician. The word ...

, identifying himself as the prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

entrusted with guiding humanity into the Æon of Horus in the early 20th century. A prolific writer, he published widely over the course of his life.

Born to a wealthy family in Royal Leamington Spa, Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon an ...

, Crowley rejected his parents' fundamentalist Christian Plymouth Brethren faith to pursue an interest in Western esotericism

Western esotericism, also known as esotericism, esoterism, and sometimes the Western mystery tradition, is a term scholars use to categorise a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas a ...

. He was educated at Trinity College at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, where he focused his attentions on mountaineering and poetry, resulting in several publications. Some biographers allege that here he was recruited into a British intelligence agency, further suggesting that he remained a spy throughout his life. In 1898, he joined the esoteric Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, where he was trained in ceremonial magic by Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers and Allan Bennett. He went mountaineering in Mexico with Oscar Eckenstein, before studying Hindu and Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

practices in India. In 1904 he married Rose Edith Kelly and they honeymooned in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo met ...

, Egypt, where Crowley claimed to have been contacted by a supernatural entity named Aiwass, who provided him with '' The Book of the Law'', a sacred text that served as the basis for Thelema. Announcing the start of the Æon of Horus, ''The Book'' declared that its followers should "Do what thou wilt" and seek to align themselves with their True Will through the practice of magick.

After the unsuccessful 1905 Kanchenjunga expedition and a visit to India and China, Crowley returned to Britain, where he attracted attention as a prolific author of poetry, novels, and occult literature. In 1907, he and George Cecil Jones co-founded an esoteric order, the A∴A∴, through which they propagated Thelema. After spending time in Algeria, in 1912 he was initiated into another esoteric order, the German-based Ordo Templi Orientis

Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.; ) is an occult Initiation, initiatory organization founded at the beginning of the 20th century. The origins of the O.T.O. can be traced back to the German-speaking occultists Carl Kellner (mystic), Carl Kellner, He ...

(O.T.O.), rising to become the leader of its British branch, which he reformulated in accordance with his Thelemite beliefs. Through the O.T.O., Thelemite groups were established in Britain, Australia, and North America. Crowley spent the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

in the United States, where he took up painting and campaigned for the German war effort against Britain, later revealing that he had infiltrated the pro-German movement to assist the British intelligence services. In 1920, he established the Abbey of Thelema

The Abbey of Thelema is a small house which was used as a temple and spiritual centre, founded by Aleister Crowley and Leah Hirsig in Cefalù (Sicily, Italy) in 1920.

The villa still stands today, but in poor condition. Filmmaker Kenneth Anger, ...

, a religious commune in Cefalù

Cefalù (), classically known as Cephaloedium (), is a city and comune in the Italian Metropolitan City of Palermo, located on the Tyrrhenian coast of Sicily about east of the provincial capital and west of Messina. The town, with its populati ...

, Sicily where he lived with various followers. His libertine lifestyle led to denunciations in the British press, and the Italian government evicted him in 1923. He divided the following two decades between France, Germany, and England, and continued to promote Thelema until his death.

Crowley gained widespread notoriety during his lifetime, being a recreational drug user, bisexual

Bisexuality is a romantic or sexual attraction or behavior toward both males and females, or to more than one gender. It may also be defined to include romantic or sexual attraction to people regardless of their sex or gender identity, wh ...

, and an individualist social critic

Social criticism is a form of academic or journalistic criticism focusing on social issues in contemporary society, in particular with respect to perceived injustices and power relations in general.

Social criticism of the Enlightenment

The or ...

. Crowley has remained a highly influential figure over Western esotericism and the counterculture of the 1960s, and continues to be considered a prophet in Thelema. He is the subject of various biographies and academic studies.

Early life

Youth

Crowley was born Edward Alexander Crowley at 30 Clarendon Square in Royal Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, on 12 October 1875. His father, Edward Crowley (1829–1887), was trained as an engineer, but his share in a lucrative family brewing business, Crowley's Alton Ales, had allowed him to retire before his son was born. His mother, Emily Bertha Bishop (1848–1917), came from a Devonshire-Somerset family and had a strained relationship with her son; she described him as "the Beast", a name that he revelled in. The couple had been married at London's Kensington Registry Office in November 1874, and were evangelical Christians. Crowley's father had been born a

Crowley was born Edward Alexander Crowley at 30 Clarendon Square in Royal Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, on 12 October 1875. His father, Edward Crowley (1829–1887), was trained as an engineer, but his share in a lucrative family brewing business, Crowley's Alton Ales, had allowed him to retire before his son was born. His mother, Emily Bertha Bishop (1848–1917), came from a Devonshire-Somerset family and had a strained relationship with her son; she described him as "the Beast", a name that he revelled in. The couple had been married at London's Kensington Registry Office in November 1874, and were evangelical Christians. Crowley's father had been born a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

, but had converted to the Exclusive Brethren, a faction of a Christian fundamentalist group known as the Plymouth Brethren; Emily likewise converted upon marriage. Crowley's father was particularly devout, spending his time as a travelling preacher for the sect and reading a chapter from the Bible to his wife and son after breakfast every day. Following the death of their baby daughter in 1880, in 1881 the Crowleys moved to Redhill, Surrey. At the age of 8, Crowley was sent to H.T. Habershon's evangelical Christian boarding school in Hastings

Hastings () is a large seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east to the county town of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to the north-west a ...

, and then to Ebor preparatory school in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge beca ...

, run by the Reverend Henry d'Arcy Champney, whom Crowley considered a sadist.

In March 1887, when Crowley was 11, his father died of tongue cancer. Crowley described this as a turning point in his life, and he always maintained an admiration of his father, describing him as "my hero and my friend". Inheriting a third of his father's wealth, he began misbehaving at school and was harshly punished by Champney; Crowley's family removed him from the school when he developed albuminuria. He then attended Malvern College

Malvern College is an independent coeducational day and boarding school in Malvern, Worcestershire, England. It is a public school in the British sense of the term and is a member of the Rugby Group and of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' ...

and Tonbridge School, both of which he despised and left after a few terms. He became increasingly sceptical regarding Christianity, pointing out inconsistencies in the Bible to his religious teachers, and went against the Christian morality of his upbringing by smoking, masturbating, and having sex with prostitutes from whom he contracted gonorrhea. Sent to live with a Brethren tutor in Eastbourne

Eastbourne () is a town and seaside resort in East Sussex, on the south coast of England, east of Brighton and south of London. Eastbourne is immediately east of Beachy Head, the highest chalk sea cliff in Great Britain and part of the l ...

, he undertook chemistry courses at Eastbourne College

Eastbourne College is a co-educational independent school in the British public school tradition, for day and boarding pupils aged 13–18, in the town of Eastbourne on the south coast of England. The College's headmaster is Tom Lawson.

Overv ...

. Crowley developed interests in chess

Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to dist ...

, poetry, and mountain climbing, and in 1894 climbed Beachy Head

Beachy Head is a chalk headland in East Sussex, England. It is situated close to Eastbourne, immediately east of the Seven Sisters.

Beachy Head is located within the administrative area of Eastbourne Borough Council which owns the land, for ...

before visiting the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, ...

and joining the Scottish Mountaineering Club. The following year he returned to the Bernese Alps, climbing the Eiger, Trift, Jungfrau, Mönch, and Wetterhorn.

Cambridge University: 1895–1898

Having adopted the name of Aleister over Edward, in October 1895 Crowley began a three-year course atTrinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

, where he was entered for the Moral Science Tripos

At the University of Cambridge, a Tripos (, plural 'Triposes') is any of the examinations that qualify an undergraduate for a bachelor's degree or the courses taken by a student to prepare for these. For example, an undergraduate studying mathe ...

studying philosophy. With approval from his personal tutor, he changed to English literature, which was not then part of the curriculum offered. Crowley spent much of his time at university engaged in his pastimes, becoming president of the chess club and practising the game for two hours a day; he briefly considered a professional career as a chess player. Crowley also embraced his love of literature and poetry, particularly the works of Richard Francis Burton and Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his ach ...

. Many of his own poems appeared in student publications such as '' The Granta'', ''Cambridge Magazine'', and ''Cantab''. He continued his mountaineering, going on holiday to the Alps to climb every year from 1894 to 1898, often with his friend Oscar Eckenstein, and in 1897 he made the first ascent of the Mönch without a guide. These feats led to his recognition in the Alpine mountaineering community.

Crowley had his first significant mystical experience while on holiday in Stockholm in December 1896. Several biographers, including Lawrence Sutin, Richard Kaczynski, and Tobias Churton, believed that this was the result of Crowley's first same-sex sexual experience, which enabled him to recognize his bisexuality

Bisexuality is a romantic or sexual attraction or behavior toward both males and females, or to more than one gender. It may also be defined to include romantic or sexual attraction to people regardless of their sex or gender identity, wh ...

. At Cambridge, Crowley maintained a vigorous sex life with women—largely with female prostitutes, from one of whom he caught syphilis—but eventually he took part in same-sex activities, despite their illegality. In October 1897, Crowley met Herbert Charles Pollitt

Herbert Charles Pollitt (July 20, 1871 – 1942), also known as Jerome Pollitt, was a patron of the arts and on-stage female impersonator who performed as Diane de Rougy (an homage to Liane de Pougy). He became notorious as a Cambridge undergrad ...

, president of the Cambridge University Footlights Dramatic Club, and the two entered into a relationship. They broke apart because Pollitt did not share Crowley's increasing interest in Western esotericism, a break-up that Crowley would regret for many years.

In 1897, Crowley travelled to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

in Russia, later saying that he was trying to learn Russian as he was considering a future diplomatic career there. In October 1897, a brief illness triggered considerations of mortality and "the futility of all human endeavour", and Crowley abandoned all thoughts of a diplomatic career in favour of pursuing an interest in the occult.

In March 1898, he obtained A.E. Waite's ''The Book of Black Magic and of Pacts'', and then Karl von Eckartshausen's ''The Cloud Upon the Sanctuary'', furthering his occult interests. That same year, Crowley privately published 100 copies of his poem ''Aceldama: A Place to Bury Strangers In,'' but it was not a particular success. ''Aceldama'' was issued by Leonard Smithers

Leonard Charles Smithers (19 December 1861 – 19 December 1907) was a London bookseller and publisher associated with the Decadent movement.

Biography

Born in Sheffield, Smithers worked as a solicitor, qualifying in 1884,Jon R. Godsall, ''Th ...

.

That same year, Crowley published a string of other poems, including '' White Stains'', a Decadent collection of erotic poetry that was printed abroad lest its publication be prohibited by the British authorities. In July 1898, he left Cambridge, not having taken any degree at all despite a "first class" showing in his 1897 exams and consistent "second class honours" results before that.

The Golden Dawn: 1898–1899

In August 1898, Crowley was in

In August 1898, Crowley was in Zermatt

Zermatt () is a municipality in the district of Visp in the German-speaking section of the canton of Valais in Switzerland. It has a year-round population of about 5,800 and is classified as a town by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO ...

, Switzerland, where he met the chemist Julian L. Baker, and the two began discussing their common interest in alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world ...

. Back in London, Baker introduced Crowley to George Cecil Jones, Baker's brother-in-law and a fellow member of the occult society known as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which had been founded in 1888. Crowley was initiated into the Outer Order of the Golden Dawn on 18 November 1898 by the group's leader, Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers. The ceremony took place in the Golden Dawn's Isis-Urania Temple held at London's Mark Masons Hall, where Crowley took the magical motto and name "Frater Perdurabo", which he interpreted as "I shall endure to the end".

Crowley moved into his own luxury flat at 67–69 Chancery Lane and soon invited a senior Golden Dawn member, Allan Bennett, to live with him as his personal magical tutor. Bennett taught Crowley more about ceremonial magic and the ritual use of drugs, and together they performed the rituals of the '' Goetia'', until Bennett left for South Asia to study Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

. In November 1899, Crowley purchased Boleskine House in Foyers

A foyer is a type of room, typically an entrance.

Foyer or ''variation'', may refer to:

People

* Bob Foyers (1868–1942), UK soccer player

* Christine Foyer (born 1952), UK botanist

* Jean Foyer (1921–2008), French politician

* Lucien Le Fo ...

on the shore of Loch Ness in Scotland. He developed a love of Scottish culture, describing himself as the "Laird

Laird () is the owner of a large, long-established Scottish estate. In the traditional Scottish order of precedence, a laird ranked below a baron and above a gentleman. This rank was held only by those lairds holding official recognition in a ...

of Boleskine", and took to wearing traditional highland dress, even during visits to London. He continued writing poetry, publishing ''Jezebel and Other Tragic Poems'', ''Tales of Archais'', ''Songs of the Spirit'', ''Appeal to the American Republic'', and ''Jephthah'' in 1898–99; most gained mixed reviews from literary critics, although ''Jephthah'' was considered a particular critical success.

Crowley soon progressed through the lower grades of the Golden Dawn, and was ready to enter the group's inner Second Order. He was unpopular in the group; his bisexuality and libertine lifestyle had gained him a bad reputation, and he had developed feuds with some of the members, including W. B. Yeats. When the Golden Dawn's London lodge refused to initiate Crowley into the Second Order, he visited Mathers in Paris, who personally admitted him into the Adeptus Minor Grade. A schism had developed between Mathers and the London members of the Golden Dawn, who were unhappy with his autocratic rule. Acting under Mathers' orders, Crowley—with the help of his mistress and fellow initiate Elaine Simpson

Elaine may refer to:

* Elaine (legend), name shared by several different female characters in Arthurian legend, especially:

** Elaine of Astolat

** Elaine of Corbenic

* "Elaine" (short story), 1945 short story by J. D. Salinger

* Elaine (singe ...

—attempted to seize the Vault of the Adepts, a temple space at 36 Blythe Road in West Kensington, from the London lodge members. When the case was taken to court, the judge ruled in favour of the London lodge, as they had paid for the space's rent, leaving both Crowley and Mathers isolated from the group.

Mexico, India, Paris, and marriage: 1900–1903

In 1900, Crowley travelled to Mexico via the United States, settling inMexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley of ...

and starting a relationship with a local woman. Developing a love of the country, he continued experimenting with ceremonial magic, working with John Dee's Enochian invocations. He later claimed to have been initiated into Freemasonry

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

while there, and he wrote a play based on Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

's '' Tannhäuser'' as well as a series of poems, published as ''Oracles'' (1905). Eckenstein joined him later in 1900, and together they climbed several mountains, including Iztaccihuatl, Popocatepetl, and Colima, the latter of which they had to abandon owing to a volcanic eruption. Leaving Mexico, Crowley headed to San Francisco before sailing for Hawaii aboard the ''Nippon Maru''. On the ship, he had a brief affair with a married woman named Mary Alice Rogers; saying he had fallen in love with her, he wrote a series of poems about the romance, published as ''Alice: An Adultery'' (1903).

Briefly stopping in Japan and Hong Kong, Crowley reached Ceylon, where he met with Allan Bennett, who was there studying

Briefly stopping in Japan and Hong Kong, Crowley reached Ceylon, where he met with Allan Bennett, who was there studying Shaivism

Shaivism (; sa, शैवसम्प्रदायः, Śaivasampradāyaḥ) is one of the major Hindu traditions, which worships Shiva as the Supreme Being. One of the largest Hindu denominations, it incorporates many sub-traditions rangi ...

. The pair spent some time in Kandy

Kandy ( si, මහනුවර ''Mahanuwara'', ; ta, கண்டி Kandy, ) is a major city in Sri Lanka located in the Central Province. It was the last capital of the ancient kings' era of Sri Lanka. The city lies in the midst of hills ...

before Bennett decided to become a Buddhist monk in the Theravada

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

tradition, travelling to Burma to do so. Crowley decided to tour India, devoting himself to the Hindu practice of '' Rāja yoga'', from which he claimed to have achieved the spiritual state of ''dhyana

Dhyana may refer to:

Meditative practices in Indian religions

* Dhyana in Buddhism (Pāli: ''jhāna'')

* Dhyana in Hinduism

* Jain Dhyāna, see Jain meditation

Other

*''Dhyana'', a work by British composer John Tavener (1944-2013)

* ''Dhyan ...

''. He spent much of this time studying at the Meenakshi Temple in Madura. At this time he also wrote poetry which was published as ''The Sword of Song'' (1904). He contracted malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or deat ...

, and had to recuperate from the disease in Calcutta and Rangoon. In 1902, he was joined in India by Eckenstein and several other mountaineers: Guy Knowles, H. Pfannl, V. Wesseley, and Jules Jacot-Guillarmod. Together, the Eckenstein-Crowley expedition attempted K2, which had never been climbed. On the journey, Crowley was afflicted with influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

, malaria, and snow blindness

Photokeratitis or ultraviolet keratitis is a painful eye condition caused by exposure of insufficiently protected eyes to the ultraviolet (UV) rays from either natural (e.g. intense sunlight) or artificial (e.g. the electric arc during weldin ...

, and other expedition members were also struck with illness. They reached an altitude of before turning back.

Having arrived in Paris in November 1902, he socialized with his friend the painter Gerald Kelly, and through him became a fixture of the Parisian arts scene. Whilst there, Crowley wrote a series of poems on the work of an acquaintance, the sculptor Auguste Rodin. These poems were later published as ''Rodin in Rime'' (1907). One of those frequenting this milieu was W. Somerset Maugham, who after briefly meeting Crowley later used him as a model for the character of Oliver Haddo in his novel '' The Magician'' (1908). He returned to Boleskine in April 1903. In August, Crowley wed Gerald Kelly's sister Rose Edith Kelly in a "marriage of convenience" to prevent her from entering an arranged marriage

Arranged marriage is a type of marital union where the bride and groom are primarily selected by individuals other than the couple themselves, particularly by family members such as the parents. In some cultures a professional matchmaker may be us ...

; the marriage appalled the Kelly family and damaged his friendship with Gerald. Heading on a honeymoon to Paris, Cairo, and then Ceylon, Crowley fell in love with Rose and worked to prove his affections. While on his honeymoon, he wrote her a series of love poems, published as ''Rosa Mundi and other Love Songs'' (1906), as well as authoring the religious satire ''Why Jesus Wept'' (1904).

Developing Thelema

Egypt and ''The Book of the Law'': 1904

In February 1904, Crowley and Rose arrived inCairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo met ...

. Claiming to be a prince and princess, they rented an apartment in which Crowley set up a temple room and began invoking ancient Egyptian deities, while studying Islamic mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

. According to Crowley's later account, Rose regularly became delirious and informed him "they are waiting for you." On 18 March, she explained that "they" were the god Horus

Horus or Heru, Hor, Har in Ancient Egyptian, is one of the most significant ancient Egyptian deities who served many functions, most notably as god of kingship and the sky. He was worshipped from at least the late prehistoric Egypt until the P ...

, and on 20 March proclaimed that "the Equinox of the Gods has come". She led him to a nearby museum, where she showed him a seventh-century BCE mortuary stele known as the Stele of Ankh-ef-en-Khonsu; Crowley thought it important that the exhibit's number was 666, the Number of the Beast in Christian belief, and in later years termed the artefact the "Stele of Revealing."

According to Crowley's later statements, on 8 April he heard a disembodied voice claiming to be that of Aiwass, the messenger of Horus, or Hoor-Paar-Kraat. Crowley said that he wrote down everything the voice told him over the course of the next three days, and titled it ''Liber AL vel Legis'' or '' The Book of the Law''. The book proclaimed that humanity was entering a new Aeon, and that Crowley would serve as its prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

. It stated that a supreme moral law was to be introduced in this Aeon, "Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law," and that people should learn to live in tune with their Will. This book, and the philosophy that it espoused, became the cornerstone of Crowley's religion, Thelema

Thelema () is a Western esoteric and occult social or spiritual philosophy and new religious movement founded in the early 1900s by Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), an English writer, mystic, occultist, and ceremonial magician. The word ...

. Crowley said that at the time he had been unsure what to do with ''The Book of the Law''. Often resenting it, he said that he ignored the instructions which the text commanded him to perform, which included taking the Stele of Revealing from the museum, fortifying his own island, and translating the book into all the world's languages. According to his account, he instead sent typescripts of the work to several occultists he knew, putting the manuscript away and ignoring it.

Kanchenjunga and China: 1905–06

Returning to Boleskine, Crowley came to believe that Mathers had begun using magic against him, and the relationship between the two broke down. On 28 July 1905, Rose gave birth to Crowley's first child, a daughter named Lilith, with Crowley writing the pornographic '' Snowdrops from a Curate's Garden'' to entertain his recuperating wife. He also founded a publishing company through which to publish his poetry, naming it the Society for the Propagation of Religious Truth in parody of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Among its first publications were Crowley's ''Collected Works'', edited by Ivor Back, an old friend of Crowley's who was both a practicing surgeon and an enthusiast of literature. His poetry often received strong reviews (either positive or negative), but never sold well. In an attempt to gain more publicity, he issued a reward of £100 for the best essay on his work. The winner of this was J. F. C. Fuller, a British Army officer and military historian, whose essay, ''The Star in the West'' (1907), heralded Crowley's poetry as some of the greatest ever written. Crowley decided to climb Kanchenjunga in the Himalayas of Nepal, widely recognized as the world's most treacherous mountain. The collaboration between Jacot-Guillarmod, Charles Adolphe Reymond, Alexis Pache, and Alcesti C. Rigo de Righi,

Crowley decided to climb Kanchenjunga in the Himalayas of Nepal, widely recognized as the world's most treacherous mountain. The collaboration between Jacot-Guillarmod, Charles Adolphe Reymond, Alexis Pache, and Alcesti C. Rigo de Righi, the expedition

''The Expedition'' is the live album by the American metal band Kamelot, released in October 2000 through Noise Records. The last three tracks are rare studio recordings: "We Three Kings" (instrumental) and "One Day" are additional material fro ...

was marred by much argument between Crowley and the others, who thought that he was reckless. They eventually mutinied against Crowley's control, with the other climbers heading back down the mountain as nightfall approached despite Crowley's warnings that it was too dangerous. Subsequently, Pache and several porters were killed in an accident, something for which Crowley was widely blamed by the mountaineering community.

Spending time in Moharbhanj, where he took part in big-game hunting and wrote the homoerotic work ''The Scented Garden'', Crowley met up with Rose and Lilith in Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, comm ...

before being forced to leave India after non-lethally shooting two men who tried to mug him. Briefly visiting Bennett in Burma, Crowley and his family decided to tour Southern China, hiring porters and a nanny for the purpose. Crowley smoked opium throughout the journey, which took the family from Tengyueh through to Yungchang, Tali, Yunnanfu

Kunming (; ), also known as Yunnan-Fu, is the capital and largest city of Yunnan province, China. It is the political, economic, communications and cultural centre of the province as well as the seat of the provincial government. The headquar ...

, and then Hanoi

Hanoi or Ha Noi ( or ; vi, Hà Nội ) is the capital and second-largest city of Vietnam. It covers an area of . It consists of 12 urban districts, one district-leveled town and 17 rural districts. Located within the Red River Delta, Hanoi i ...

. On the way, he spent much time on spiritual and magical work, reciting the "Bornless Ritual", an invocation to his Holy Guardian Angel, on a daily basis.

While Rose and Lilith returned to Europe, Crowley headed to Shanghai to meet old friend Elaine Simpson, who was fascinated by ''The Book of the Law''; together they performed rituals in an attempt to contact Aiwass. Crowley then sailed to Japan and Canada, before continuing to New York City, where he unsuccessfully solicited support for a second expedition up Kanchenjunga. Upon arrival in Britain, Crowley learned that his daughter Lilith had died of typhoid in Rangoon

Yangon ( my, ရန်ကုန်; ; ), formerly spelled as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar (also known as Burma). Yangon served as the capital of Myanmar until 2006, when the military governme ...

, something he later blamed on Rose's increasing alcoholism. Under emotional distress, his health began to suffer, and he underwent a series of surgical operations. He began short-lived romances with actress Vera "Lola" Neville (née Snepp) and author Ada Leverson, while Rose gave birth to Crowley's second daughter, Lola Zaza, in February 1907.

The A∴A∴ and The Holy Books of Thelema: 1907–1909

With his old mentor George Cecil Jones, Crowley continued performing the Abramelin rituals at the Ashdown Park Hotel in Coulsdon, Surrey. Crowley claimed that in doing so he attained '' samadhi'', or union with Godhead, thereby marking a turning point in his life. Making heavy use of hashish during these rituals, he wrote an essay on "The Psychology of Hashish" (1909) in which he championed the drug as an aid to mysticism. He also claimed to have been contacted once again by Aiwass in late October and November 1907, adding that Aiwass dictated two further texts to him, "Liber VII" and "Liber Cordis Cincti Serpente", both of which were later classified in the corpus of The Holy Books of Thelema. Crowley wrote down more Thelemic Holy Books during the last two months of the year, including "Liber LXVI", "Liber Arcanorum", "Liber Porta Lucis, Sub Figura X", "Liber Tau", "Liber Trigrammaton" and "Liber DCCCXIII vel Ararita", which he again claimed to have received from a preternatural source. Crowley stated that in June 1909, when the manuscript of ''The Book of the Law'' was rediscovered at Boleskine, he developed the opinion that Thelema represented objective truth. Crowley's inheritance was running out. Trying to earn money, he was hired by George Montagu Bennett, the Earl of Tankerville, to help protect him fromwitchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have u ...

; recognizing Bennett's paranoia as being based in his cocaine addiction, Crowley took him on holiday to France and Morocco to recuperate. In 1907, he also began taking in paying students, whom he instructed in occult and magical practice. Victor Neuburg, whom Crowley met in February 1907, became his sexual partner and closest disciple; in 1908 the pair toured northern Spain before heading to Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the ca ...

, Morocco. The following year Neuburg stayed at Boleskine, where he and Crowley engaged in sadomasochism. Crowley continued to write prolifically, producing such works of poetry as ''Ambergris'', ''Clouds Without Water'', and ''Konx Om Pax'', as well as his first attempt at an autobiography, ''The World's Tragedy''. Recognizing the popularity of short horror stories, Crowley wrote his own, some of which were published, and he also published several articles in '' Vanity Fair'', a magazine edited by his friend Frank Harris. He also wrote '' Liber 777'', a book of magical and Qabalistic correspondences that borrowed from Mathers and Bennett.

In November 1907, Crowley and Jones decided to found an occult order to act as a successor to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, being aided in doing so by Fuller. The result was the A∴A∴. The group's headquarters and temple were situated at 124 Victoria Street in central London, and their rites borrowed much from those of the Golden Dawn, but with an added Thelemic basis. Its earliest members included solicitor Richard Noel Warren, artist Austin Osman Spare, Horace Sheridan-Bickers, author George Raffalovich, Francis Henry Everard Joseph Feilding, engineer Herbert Edward Inman, Kenneth Ward, and Charles Stansfeld Jones. In March 1909, Crowley began production of a biannual periodical titled '' The Equinox''. He billed this periodical, which was to become the "Official Organ" of the A∴A∴, as "The Review of Scientific Illuminism".

Crowley had become increasingly frustrated with Rose's alcoholism, and in November 1909 he divorced her on the grounds of his own adultery. Lola was entrusted to Rose's care; the couple remained friends and Rose continued to live at Boleskine. Her alcoholism worsened, and as a result she was institutionalized in September 1911.

Algeria and the Rites of Eleusis: 1909–1911

In November 1909, Crowley and Neuburg travelled to Algeria, touring the desert from El Arba to Aumale, Bou Saâda, and then Dā'leh Addin, with Crowley reciting theQuran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

on a daily basis.Owen, A., "Aleister Crowley in the Desert", in ''The Place of Enchantment: British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern'' (Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press is the largest and one of the oldest university presses in the United States. It is operated by the University of Chicago and publishes a wide variety of academic titles, including '' The Chicago Manual of Style'' ...

, 2004)pp. 186–202

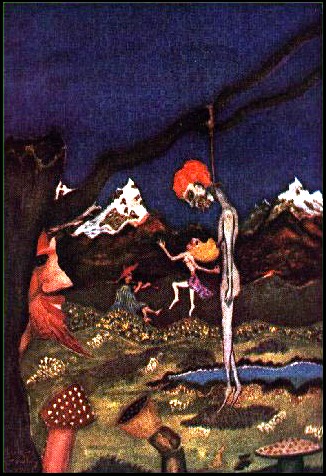

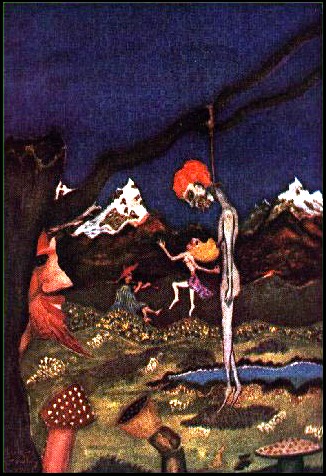

. During the trip he invoked the thirty aethyrs of Enochian magic, with Neuburg recording the results, later published in ''The Equinox'' as ''The Vision and the Voice''. Following a mountaintop sex magic ritual, Crowley also performed an evocation to the demon Choronzon involving

blood sacrifice

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly ex ...

, and considered the results to be a watershed in his magical career. Returning to London in January 1910, Crowley found that Mathers was suing him for publishing Golden Dawn secrets in ''The Equinox''; the court found in favour of Crowley. The case was widely reported in the press, with Crowley gaining wider fame. Crowley enjoyed this, and played up to the sensationalist stereotype of being a Satanist and advocate of human sacrifice, despite being neither.

The publicity attracted new members to the A∴A∴, among them Frank Bennett, James Bayley, Herbert Close, and James Windram. The Australian violinist Leila Waddell soon became Crowley's lover. Deciding to expand his teachings to a wider audience, Crowley developed the Rites of Artemis, a public performance of magic and symbolism featuring A∴A∴ members personifying various deities. It was first performed at the A∴A∴ headquarters, with attendees given a fruit punch containing peyote

The peyote (; ''Lophophora williamsii'' ) is a small, spineless cactus which contains psychoactive alkaloids, particularly mescaline. ''Peyote'' is a Spanish word derived from the Nahuatl (), meaning "caterpillar cocoon", from a root , "to g ...

to enhance their experience. Various members of the press attended, and reported largely positively on it. In October and November 1910, Crowley decided to stage something similar, the Rites of Eleusis, at Caxton Hall, Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buck ...

; this time press reviews were mixed. Crowley came under particular criticism from West de Wend Fenton, editor of ''The Looking Glass'' newspaper, who called him "one of the most blasphemous and cold-blooded villains of modern times". Fenton's articles suggested that Crowley and Jones were involved in homosexual activity; Crowley did not mind, but Jones unsuccessfully sued for libel. Fuller broke off his friendship and involvement with Crowley over the scandal, and Crowley and Neuburg returned to Algeria for further magical workings.

''The Equinox'' continued publishing, and various books of literature and poetry were also published under its imprint, like Crowley's ''Ambergris'', ''The Winged Beetle'', and ''The Scented Garden'', as well as Neuburg's ''The Triumph of Pan'' and Ethel Archer's ''The Whirlpool''. In 1911, Crowley and Waddell holidayed in Montigny-sur-Loing, where he wrote prolifically, producing poems, short stories, plays, and 19 works on magic and mysticism, including the two final Holy Books of Thelema. In Paris, he met Mary Desti, who became his next "Scarlet Woman", with the two undertaking magical workings in St. Moritz

St. Moritz (also german: Sankt Moritz, rm, , it, San Maurizio, french: Saint-Moritz) is a high Alpine resort town in the Engadine in Switzerland, at an elevation of about above sea level. It is Upper Engadine's major town and a municipality in ...

; Crowley believed that one of the Secret Chiefs, Ab-ul-Diz, was speaking through her. Based on Desti's statements when in trance, Crowley wrote the two-volume '' Book 4'' (1912–13) and at the time developed the spelling "magick" in reference to the paranormal phenomenon

Paranormal events are purported phenomena described in popular culture, folk, and other non-scientific bodies of knowledge, whose existence within these contexts is described as being beyond the scope of normal scientific understanding. Nota ...

as a means of distinguishing it from the stage magic of illusionists.

Ordo Templi Orientis and the Paris Working: 1912–1914

In early 1912, Crowley published ''

In early 1912, Crowley published ''The Book of Lies

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in ...

'', a work of mysticism that biographer Lawrence Sutin described as "his greatest success in merging his talents as poet, scholar, and magus". The German occultist Theodor Reuss later accused him of publishing some of the secrets of his own occult order, the Ordo Templi Orientis

Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.; ) is an occult Initiation, initiatory organization founded at the beginning of the 20th century. The origins of the O.T.O. can be traced back to the German-speaking occultists Carl Kellner (mystic), Carl Kellner, He ...

(O.T.O.), within ''The Book''. Crowley convinced Reuss that the similarities were coincidental, and the two became friends. Reuss appointed Crowley as head of the O.T.O's British branch, the Mysteria Mystica Maxima (MMM), and at a ceremony in Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

Crowley adopted the magical name of Baphomet and was proclaimed "X° Supreme Rex and Sovereign Grand Master General of Ireland, Iona, and all the Britons". With Reuss' permission, Crowley set about advertising the MMM and re-writing many O.T.O. rituals, which were then based largely on Freemasonry

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

; his incorporation of Thelemite elements proved controversial in the group. Fascinated by the O.T.O's emphasis on sex magic, Crowley devised a magical working based on anal sex and incorporated it into the syllabus for those O.T.O. members who had been initiated into the eleventh degree.

In March 1913, Crowley acted as producer for ''The Ragged Ragtime Girls'', a group of female violinists led by Waddell, as they performed at London's Old Tivoli

The Old Tivoli in Aachen, Germany, was the stadium of Aachen's best known football team Alemannia Aachen until 2009.

Overview

In 1908, the city of Aachen leased the area of the old manor Tivoli to the club, named after the inn ''Gut Tivoli'' wh ...

theatre. They subsequently performed in Moscow for six weeks, where Crowley had a sadomasochistic relationship with the Hungarian Anny Ringler. In Moscow, Crowley continued to write plays and poetry, including "Hymn to Pan", and the Gnostic Mass, a Thelemic ritual that became a key part of O.T.O. liturgy. Churton suggested that Crowley had travelled to Moscow on the orders of British intelligence to spy on revolutionary elements in the city. In January 1914, Crowley and Neuburg settled into an apartment in Paris, where the former was involved in the controversy surrounding Jacob Epstein's new monument to Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

. Together Crowley and Neuburg performed the six-week "Paris Working", a period of intense ritual involving strong drug use in which they invoked the gods Mercury and Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandt ...

. As part of the ritual, the couple performed acts of sex magic together, at times being joined by journalist Walter Duranty. Inspired by the results of the Working, Crowley wrote ''Liber Agapé'', a treatise on sex magic. Following the Paris Working, Neuburg began to distance himself from Crowley, resulting in an argument in which Crowley curse

A curse (also called an imprecation, malediction, execration, malison, anathema, or commination) is any expressed wish that some form of adversity or misfortune will befall or attach to one or more persons, a place, or an object. In particular, ...

d him.

United States: 1914–1919

By 1914, Crowley was living a hand-to-mouth existence, relying largely on donations from A∴A∴ members and dues payments made to O.T.O. In May, he transferred ownership of Boleskine House to the MMM for financial reasons, and in July he went mountaineering in the Swiss Alps. During this time theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

broke out.

After recuperating from a bout of phlebitis, Crowley set sail for the United States aboard the RMS ''Lusitania'' in October 1914. Arriving in New York City, he moved into a hotel and began earning money writing for the American edition of '' Vanity Fair'' and undertaking freelance work for the famed astrologer Evangeline Adams. In the city, he continued experimenting with sex magic, through the use of masturbation, female prostitutes, and male clients of a Turkish bathhouse; all of these encounters were documented in his diaries.

Professing to be of Irish ancestry and a supporter of Irish independence from Great Britain, Crowley began to espouse support for Germany in their war against Britain. He became involved in New York's pro-German movement, and in January 1915 German spy George Sylvester Viereck employed him as a writer for his propagandist paper, '' The Fatherland'', which was dedicated to keeping the US neutral in the conflict. In later years, detractors denounced Crowley as a traitor to Britain for this action.

Crowley entered into a relationship with Jeanne Robert Foster, with whom he toured the West Coast. In

Professing to be of Irish ancestry and a supporter of Irish independence from Great Britain, Crowley began to espouse support for Germany in their war against Britain. He became involved in New York's pro-German movement, and in January 1915 German spy George Sylvester Viereck employed him as a writer for his propagandist paper, '' The Fatherland'', which was dedicated to keeping the US neutral in the conflict. In later years, detractors denounced Crowley as a traitor to Britain for this action.

Crowley entered into a relationship with Jeanne Robert Foster, with whom he toured the West Coast. In Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the city, up from 631,486 in 2016. Th ...

, headquarters of the North American O.T.O., he met with Charles Stansfeld Jones and Wilfred Talbot Smith to discuss the propagation of Thelema on the continent. In Detroit he experimented with Peyote

The peyote (; ''Lophophora williamsii'' ) is a small, spineless cactus which contains psychoactive alkaloids, particularly mescaline. ''Peyote'' is a Spanish word derived from the Nahuatl (), meaning "caterpillar cocoon", from a root , "to g ...

at Parke-Davis, then visited Seattle, San Francisco, Santa Cruz, Los Angeles, San Diego, Tijuana

Tijuana ( ,"Tijuana"

(US) and < ...

, and the (US) and < ...

Grand Canyon

The Grand Canyon (, yuf-x-yav, Wi:kaʼi:la, , Southern Paiute language: Paxa’uipi, ) is a steep-sided canyon carved by the Colorado River in Arizona, United States. The Grand Canyon is long, up to wide and attains a depth of over a ...

, before returning to New York. There he befriended Ananda Coomaraswamy and his wife Alice Richardson; Crowley and Richardson performed sex magic in April 1916, following which she became pregnant and then miscarried. Later that year he took a "magical retirement" to a cabin by Lake Pasquaney owned by Evangeline Adams. There, he made heavy use of drugs and undertook a ritual after which he proclaimed himself "Master Therion". He also wrote several short stories based on J.G. Frazer

Sir James George Frazer (; 1 January 1854 – 7 May 1941) was a Scottish social anthropologist and folklorist influential in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology and comparative religion.

Personal life

He was born on 1 Janua ...

's '' The Golden Bough'' and a work of literary criticism, ''The Gospel According to Bernard Shaw''.

In December, he moved to

In December, he moved to New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Titusville, Florida. Returning to New York City, he moved in with artist and A∴A∴ member Leon Engers Kennedy in May, learning of his mother's death. After the collapse of ''The Fatherland'', Crowley continued his association with Viereck, who appointed him contributing editor of arts journal ''The International''. Crowley used it to promote Thelema, but it soon ceased publication. He then moved to the studio apartment of Roddie Minor, who became his partner and Scarlet Woman. Through their rituals, which Crowley called "The Amalantrah Workings", he believed that they were contacted by a preternatural entity named Lam. The relationship soon ended.

In 1918, Crowley went on a magical retreat in the wilderness of

Moving to the commune with Hirsig, Shumway, and their children Hansi, Howard, and Poupée, Crowley described the scenario as "perfectly happy ... my idea of heaven." They wore robes, and performed rituals to the sun god Ra at set times during the day, also occasionally performing the Gnostic Mass; the rest of the day they were left to follow their own interests. Undertaking widespread correspondences, Crowley continued to paint, wrote a commentary on ''The Book of the Law'', and revised the third part of ''Book 4''. He offered a libertine education for the children, allowing them to play all day and witness acts of sex magic. He occasionally travelled to

Moving to the commune with Hirsig, Shumway, and their children Hansi, Howard, and Poupée, Crowley described the scenario as "perfectly happy ... my idea of heaven." They wore robes, and performed rituals to the sun god Ra at set times during the day, also occasionally performing the Gnostic Mass; the rest of the day they were left to follow their own interests. Undertaking widespread correspondences, Crowley continued to paint, wrote a commentary on ''The Book of the Law'', and revised the third part of ''Book 4''. He offered a libertine education for the children, allowing them to play all day and witness acts of sex magic. He occasionally travelled to

When the

When the

Esopus Island

Esopus Island is an uninhabited island in the Hudson River. It is part of Margaret Lewis Norrie State Park, located in the town of Hyde Park in Dutchess County, in the state of New York.

Geography

The island is located to the east of the center ...

on the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

. Here, he began a translation of the ''Tao Te Ching

The ''Tao Te Ching'' (, ; ) is a Chinese classic text written around 400 BC and traditionally credited to the sage Laozi, though the text's authorship, date of composition and date of compilation are debated. The oldest excavated portion d ...

'', painted Thelemic slogans on the riverside cliffs, and—he later claimed—experienced past life memories of being Ge Xuan

Ge Xuan (164–244), courtesy name Xiaoxian, was a Chinese Taoist practitioner who lived in the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220) and Three Kingdoms period (220–280) of China. He was the ancestor of Ge Hong and a resident of Danyang Commander ...

, Pope Alexander VI, Alessandro Cagliostro, and Eliphas Levi. Back in New York City, he moved to Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

, where he took Leah Hirsig as his lover and next Scarlet Woman. He took up painting as a hobby, exhibiting his work at the Greenwich Village Liberal Club and attracting the attention of the '' New York Evening World''. With the financial assistance of sympathetic Freemasons, Crowley revived ''The Equinox'' with the first issue of volume III, known as ''The Blue Equinox''. He spent mid-1919 on a climbing holiday in Montauk before returning to London in December.

Abbey of Thelema: 1920–1923

Now destitute and back in London, Crowley came under attack from the tabloid '' John Bull'', which labelled him traitorous "scum" for his work with the German war effort; several friends aware of his intelligence work urged him to sue, but he decided not to. When he was suffering from asthma, a doctor prescribed him heroin, to which he soon became addicted. In January 1920, he moved to Paris, renting a house in Fontainebleau with Leah Hirsig; they were soon joined in a ''ménage à trois'' by Ninette Shumway, and also (in living arrangement) by Leah's newborn daughter Anne "Poupée" Leah. Crowley had ideas of forming a community of Thelemites, which he called theAbbey of Thelema

The Abbey of Thelema is a small house which was used as a temple and spiritual centre, founded by Aleister Crowley and Leah Hirsig in Cefalù (Sicily, Italy) in 1920.

The villa still stands today, but in poor condition. Filmmaker Kenneth Anger, ...

after the Abbaye de Thélème in François Rabelais' satire '' Gargantua and Pantagruel''. After consulting the '' I Ching'', he chose Cefalù

Cefalù (), classically known as Cephaloedium (), is a city and comune in the Italian Metropolitan City of Palermo, located on the Tyrrhenian coast of Sicily about east of the provincial capital and west of Messina. The town, with its populati ...

(on Sicily, Italy) as a location, and after arriving there, began renting the old Villa Santa Barbara as his Abbey on 2 April.

Moving to the commune with Hirsig, Shumway, and their children Hansi, Howard, and Poupée, Crowley described the scenario as "perfectly happy ... my idea of heaven." They wore robes, and performed rituals to the sun god Ra at set times during the day, also occasionally performing the Gnostic Mass; the rest of the day they were left to follow their own interests. Undertaking widespread correspondences, Crowley continued to paint, wrote a commentary on ''The Book of the Law'', and revised the third part of ''Book 4''. He offered a libertine education for the children, allowing them to play all day and witness acts of sex magic. He occasionally travelled to

Moving to the commune with Hirsig, Shumway, and their children Hansi, Howard, and Poupée, Crowley described the scenario as "perfectly happy ... my idea of heaven." They wore robes, and performed rituals to the sun god Ra at set times during the day, also occasionally performing the Gnostic Mass; the rest of the day they were left to follow their own interests. Undertaking widespread correspondences, Crowley continued to paint, wrote a commentary on ''The Book of the Law'', and revised the third part of ''Book 4''. He offered a libertine education for the children, allowing them to play all day and witness acts of sex magic. He occasionally travelled to Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The city is noted for it ...

to visit rent boys and buy supplies, including drugs; his heroin addiction came to dominate his life, and cocaine began to erode his nasal cavity. There was no cleaning rota, and wild dogs and cats wandered throughout the building, which soon became unsanitary. Poupée died in October 1920, and Ninette gave birth to a daughter, Astarte Lulu Panthea, soon afterwards.

New followers continued to arrive at the Abbey to be taught by Crowley. Among them was film star Jane Wolfe, who arrived in July 1920, where she was initiated into the A∴A∴ and became Crowley's secretary. Another was Cecil Frederick Russell, who often argued with Crowley, disliking the same-sex sexual magic that he was required to perform, and left after a year. More conducive was the Australian Thelemite Frank Bennett, who also spent several months at the Abbey. In February 1922, Crowley returned to Paris for a retreat in an unsuccessful attempt to kick his heroin addiction. He then went to London in search of money, where he published articles in '' The English Review'' criticising the Dangerous Drugs Act 1920 and wrote a novel, ''Diary of a Drug Fiend

''The Diary of a Drug Fiend'', published in 1922, was occult writer and mystic Aleister Crowley's first published novel, and is also reportedly the earliest known reference to the Abbey of Thelema in Sicily.

Synopsis

The story is widely though ...

'', completed in July. On publication, it received mixed reviews; he was lambasted by the ''Sunday Express

The ''Daily Express'' is a national daily United Kingdom middle-market newspaper printed in tabloid format. Published in London, it is the flagship of Express Newspapers, owned by publisher Reach plc. It was first published as a broadsheet ...

'', which called for its burning and used its influence to prevent further reprints.

Subsequently, a young Thelemite named Raoul Loveday moved to the Abbey with his wife Betty May; while Loveday was devoted to Crowley, May detested him and life at the commune. She later said that Loveday was made to drink the blood of a sacrificed cat, and that they were required to cut themselves with razors every time they used the pronoun "I". Loveday drank from a local polluted stream, soon developing a liver infection resulting in his death in February 1923. Returning to London, May told her story to the press. ''John Bull'' proclaimed Crowley "the wickedest man in the world" and "a man we'd like to hang", and although Crowley deemed many of their accusations against him to be slanderous, he was unable to afford the legal fees to sue them. As a result, ''John Bull'' continued its attack, with its stories being repeated in newspapers throughout Europe and in North America. The Fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

government of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

learned of Crowley's activities, and in April 1923 he was given a deportation notice forcing him to leave Italy; without him, the Abbey closed.

Later life

Tunisia, Paris, and London: 1923–1929

Crowley and Hirsig went toTunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

, where, dogged by continuing poor health, he unsuccessfully tried again to give up heroin, and began writing what he termed his " autohagiography", ''The Confessions of Aleister Crowley

''The Confessions of Aleister Crowley: An Autohagiography'' is a partial autobiography by the poet and occultist Aleister Crowley. It covers the early years of his life up until the mid-late 1920s but does not include the latter part of Crowle ...

''. They were joined in Tunis by the Thelemite Norman Mudd, who became Crowley's public relations consultant. Employing a local boy, Mohammad ben Brahim, as his servant, Crowley went with him on a retreat to Nefta, where they performed sex magic together. In January 1924, Crowley travelled to Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative c ...

, France, where he met with Frank Harris, underwent a series of nasal operations, and visited the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man

The Fourth Way is an approach to self-development developed by George Gurdjieff over years of travel in the East (c. 1890 – 1912). It combines and harmonizes what he saw as three established traditional "ways" or "schools": those of the body ...

and had a positive opinion of its founder, George Gurdjieff. Destitute, he took on a wealthy student, Alexander Zu Zolar, before taking on another American follower, Dorothy Olsen. Crowley took Olsen back to Tunisia for a magical retreat in Nefta, where he also wrote ''To Man'' (1924), a declaration of his own status as a prophet entrusted with bringing Thelema to humanity. After spending the winter in Paris, in early 1925 Crowley and Olsen returned to Tunis, where he wrote ''The Heart of the Master'' (1938) as an account of a vision he experienced in a trance. In March Olsen became pregnant, and Hirsig was called to take care of her; she miscarried, following which Crowley took Olsen back to France. Hirsig later distanced herself from Crowley, who then denounced her.

According to Crowley, Reuss had named him head of the O.T.O. upon his death, but this was challenged by a leader of the German O.T.O., Heinrich Tränker. Tränker called the Hohenleuben Conference in Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Thüringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and lar ...

, Germany, which Crowley attended. There, prominent members like Karl Germer and Martha Küntzel championed Crowley's leadership, but other key figures like Albin Grau, Oskar Hopfer, and Henri Birven backed Tränker by opposing it, resulting in a split in the O.T.O. Moving to Paris, where he broke with Olsen in 1926, Crowley went through a large number of lovers over the following years, with whom he experimented in sex magic. Throughout, he was dogged by poor health, largely caused by his heroin and cocaine addictions. In 1928, Crowley was introduced to young Englishman Israel Regardie, who embraced Thelema and became Crowley's secretary for the next three years. That year, Crowley also met Gerald Yorke, who began organising Crowley's finances but never became a Thelemite. He also befriended the journalist Tom Driberg; Driberg did not accept Thelema either. It was here that Crowley also published one of his most significant works, ''Magick in Theory and Practice

''Magick, Liber ABA, Book 4'' is widely considered to be the ''magnum opus'' of 20th-century occultist Aleister Crowley, the founder of Thelema. It is a lengthy treatise on magick, his system of Western occult practice, synthesised from many ...

'', which received little attention at the time.

In December 1928 Crowley met the Nicaraguan Maria Teresa Sanchez. Crowley was deported from France by the authorities, who disliked his reputation and feared that he was a German agent. So that she could join him in Britain, Crowley married Sanchez in August 1929. Now based in London, Mandrake Press agreed to publish his autobiography in a limited edition six-volume set, also publishing his novel ''Moonchild'' and book of short stories ''The Stratagem''. Mandrake went into liquidation in November 1930, before the entirety of Crowley's ''Confessions'' could be published. Mandrake's owner P.R. Stephenson

Percy Reginald Stephensen (20 November 1901 – 28 May 1965) was an Australian writer, publisher and political activist, first aligned with communism and later shifting support towards far-right politics. He was the co-founder of the fascist A ...

meanwhile wrote ''The Legend of Aleister Crowley'', an analysis of the media coverage surrounding him.

Berlin and London: 1930–1938

In April 1930, Crowley moved toBerlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

, where he took Hanni Jaegar as his magical partner; the relationship was troubled. In September he went to Lisbon in Portugal to meet the poet Fernando Pessoa

Fernando António Nogueira Pessoa (; 13 June 1888 – 30 November 1935) was a Portuguese poet, writer, literary critic, translator, publisher, and philosopher, described as one of the most significant literary figures of the 20th century an ...

. There, he decided to fake his own death, doing so with Pessoa's help at the Boca do Inferno

Boca do Inferno ( Portuguese for Hell's Mouth) is a chasm located in the seaside cliffs close to the Portuguese city of Cascais, in the District of Lisbon

Lisbon District ( pt, Distrito de Lisboa, ) is a district located along the western co ...

rock formation. He then returned to Berlin, where he reappeared three weeks later at the opening of his art exhibition at the Gallery Neumann-Nierendorf. Crowley's paintings fitted with the fashion for German Expressionism; few of them sold, but the press reports were largely favourable. In August 1931, he took Bertha Busch as his new lover; they had a violent relationship, and often physically assaulted one another. He continued to have affairs with both men and women while in the city, and met with famous people like Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxle ...

and Alfred Adler. After befriending him, in January 1932 he took the communist Gerald Hamilton as a lodger, through whom he was introduced to many figures within the Berlin far left; it is possible that he was operating as a spy for British intelligence at this time, monitoring the communist movement.

Crowley left Busch and returned to London, where he took Pearl Brooksmith as his new Scarlet Woman. Undergoing further nasal surgery, it was here in 1932 that he was invited to be guest of honour at Foyles' Literary Luncheon, also being invited by Harry Price to speak at the National Laboratory of Psychical Research

The National Laboratory of Psychical Research was established in 1926 by Harry Price, at 16 Queensberry Place, London. Its aim was "to investigate in a dispassionate manner and by purely scientific means every phase of psychic or alleged psychic ...

. In need of money, he launched a series of court cases against people whom he believed had libelled him, some of which proved successful. He gained much publicity for his lawsuit against Constable and Co for publishing Nina Hamnett's ''Laughing Torso'' (1932)—a book he claimed libelled him by referring to his occult practice as black magic—but lost the case. The court case added to Crowley's financial problems, and in February 1935 he was declared bankrupt. During the hearing, it was revealed that Crowley had been spending three times his income for several years.