Albert Luthuli on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

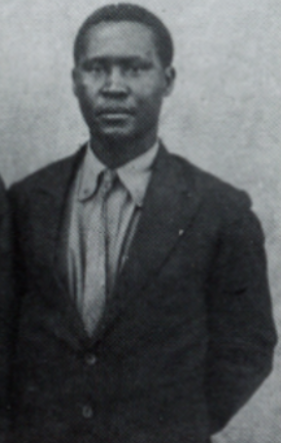

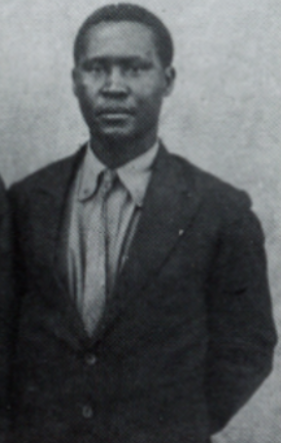

Albert John Luthuli ( – 21 July 1967) was a South African anti-apartheid activist,

Albert John Luthuli was born at the Solusi Mission Station, a

Albert John Luthuli was born at the Solusi Mission Station, a

Around 1908 or 1909, the Seventh-day Adventists expressed their interest in beginning missionary work in Natal and requested the services of Luthuli's brother, Alfred, to work as an interpreter. Luthuli and his mother followed, and departed Rhodesia to return to South Africa. Luthuli's family settled in the

Around 1908 or 1909, the Seventh-day Adventists expressed their interest in beginning missionary work in Natal and requested the services of Luthuli's brother, Alfred, to work as an interpreter. Luthuli and his mother followed, and departed Rhodesia to return to South Africa. Luthuli's family settled in the

Luthuli's mother, Mtonya, returned to Groutville and Luthuli returned to her care. They lived in a brand-new house built by his brother, Alfred, on the site where their grandfather, Ntaba, had once lived. In order to be able to send her son to boarding school, Mtonya worked long hours in the fields of the land she owned. She also took in laundry from European families in the township of Stanger to earn the necessary money for school. Luthuli was educated at a local ABM mission school until 1914, and then transferred to the Ohlange Institute.

Ohlange was founded by John Dube, who was the school principal at the time Luthuli attended. Dube was educated in America but returned to South Africa to open the Ohlange Institute to provide an education to black children. He was the first President-General of the South African Native National Congress and founded the first Zulu-language newspaper, Ilanga lase Natal. Luthuli joined the ANC in 1944, partially out of respect to his former school principal.

Luthuli describes his experience at the Ohlange Institute as "rough-and-tumble." The outbreak of

Luthuli's mother, Mtonya, returned to Groutville and Luthuli returned to her care. They lived in a brand-new house built by his brother, Alfred, on the site where their grandfather, Ntaba, had once lived. In order to be able to send her son to boarding school, Mtonya worked long hours in the fields of the land she owned. She also took in laundry from European families in the township of Stanger to earn the necessary money for school. Luthuli was educated at a local ABM mission school until 1914, and then transferred to the Ohlange Institute.

Ohlange was founded by John Dube, who was the school principal at the time Luthuli attended. Dube was educated in America but returned to South Africa to open the Ohlange Institute to provide an education to black children. He was the first President-General of the South African Native National Congress and founded the first Zulu-language newspaper, Ilanga lase Natal. Luthuli joined the ANC in 1944, partially out of respect to his former school principal.

Luthuli describes his experience at the Ohlange Institute as "rough-and-tumble." The outbreak of

Around the age of nineteen years old, Luthuli's first job after graduation came as a principal at a rural

Around the age of nineteen years old, Luthuli's first job after graduation came as a principal at a rural

Luthuli was elected as the secretary of the Natal Native Teachers' Association in 1928 and served under Z. K. Matthews' presidency. He became the president of the association in 1933. The association had three goals: improving working conditions for African teachers, motivating members to expand their skills, and encouraging members to participate in leisure activities such as

Luthuli was elected as the secretary of the Natal Native Teachers' Association in 1928 and served under Z. K. Matthews' presidency. He became the president of the association in 1933. The association had three goals: improving working conditions for African teachers, motivating members to expand their skills, and encouraging members to participate in leisure activities such as

In 1953, Z. K. Matthews proposed a large democratic convention, to be known as the Congress of the People, where all South Africans would be invited to create a

In 1953, Z. K. Matthews proposed a large democratic convention, to be known as the Congress of the People, where all South Africans would be invited to create a

After his second banning order expired in July 1956, he was arrested on 5 December and detained during the preliminary Treason Trial hearings in 1957. Luthuli was one of 156 leaders who were arrested on charges of

After his second banning order expired in July 1956, he was arrested on 5 December and detained during the preliminary Treason Trial hearings in 1957. Luthuli was one of 156 leaders who were arrested on charges of

In June 1961, during a National Executive Committee Working Group session, Mandela proposed that the ANC adopt a self-defense platform. With the government's bans on the ANC and nonviolent protests, Mandela believed waiting for revolutionary conditions to arise, which was favoured by communist members, was not an option. Instead, the ANC had to adapt to their new underground conditions and draw inspiration from successful uprisings in

In June 1961, during a National Executive Committee Working Group session, Mandela proposed that the ANC adopt a self-defense platform. With the government's bans on the ANC and nonviolent protests, Mandela believed waiting for revolutionary conditions to arise, which was favoured by communist members, was not an option. Instead, the ANC had to adapt to their new underground conditions and draw inspiration from successful uprisings in

In October 1961, during his most severe ban yet, Luthuli received the 1960

In October 1961, during his most severe ban yet, Luthuli received the 1960

Luthuli's adherence to nonviolence also had support from his friend and

Luthuli's adherence to nonviolence also had support from his friend and

traditional leader

A tradition is a system of beliefs or behaviors (folk custom) passed down within a group of people or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common examp ...

, and politician who served as the President-General of the African National Congress from 1952 until his death in 1967.

Luthuli was born to a Zulu family in 1898 at a Seventh-day Adventist

The Seventh-day Adventist Church (SDA) is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbat ...

mission in Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; ) is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council claimed it to be about ...

, Rhodesia

Rhodesia ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state, unrecognised state in Southern Africa that existed from 1965 to 1979. Rhodesia served as the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to the ...

(now Zimbabwe). In 1908 he moved to Groutville

Groutville is a town in Ilembe District Municipality in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. Home of the late ANC leader, Chief Albert Luthuli and his wife Nokukhanya Bhengu, Home to RT Rev H. Mdelwa Hlongwane founder to The Bantu Metho ...

, where his parents and grandparents had lived, to attend school under the care of his uncle. After graduating from high school with a teaching degree, Luthuli became principal of a small school in Natal where he was the sole teacher. He accepted a government bursary to study for the Higher Teacher's Diploma at Adams College. After the completion of his studies in 1922, he accepted a teaching position at Adams College where he was one of the first African teachers. In 1928, he became the secretary of the Natal Native Teachers' Association, then its president in 1933.

Luthuli's entered South African politics and the anti-apartheid movement

The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) was a British organisation that was at the centre of the international movement opposing the South African apartheid system and supporting South Africa's non-white population who were oppressed by the policies ...

in 1935, when he was elected chief of the Umvoti River Reserve in Groutville. As chief, he was exposed to the injustices facing many Africans due to the South African government's increasingly segregationist policies. This segregation would later evolve into apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

, a form of institutionalized racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

, following the National Party's election victory in 1948. Luthuli joined the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

(ANC) in 1944 and was elected the provincial president of the Natal branch in 1951. A year later in 1952, Luthuli led the Defiance Campaign

The Defiance Campaign against Unjust Laws was presented by the African National Congress (ANC) at a conference held in Bloemfontein, South Africa, in December 1951 in South Africa, 1951. The Campaign had roots in events leading up the conferenc ...

to protest the pass laws

In South Africa under apartheid, and South West Africa (now Namibia), pass laws served as an internal passport system designed to racially segregate the population, restrict movement of individuals, and allocate low-wage migrant labor. Also ...

and other laws of apartheid. As a result, the government removed him from his chief position as he refused to choose between being a member of the ANC or a chief at Groutville. In the same year, he was elected President-General of the ANC. After the Sharpeville massacre, where sixty-nine Africans were killed, leaders within the ANC such as Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela ( , ; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa f ...

believed the organisation should take up armed resistance against the government. Luthuli was initially against the use of violence. He later gradually came to accept it, but stayed committed to nonviolence on a personal level. Following four banning orders, the imprisonment and exile of his political allies, and the banning of the ANC, Luthuli's power as President-General gradually waned. The subsequent creation of uMkhonto we Sizwe

uMkhonto weSizwe (; abbreviated MK; ) was the paramilitary wing of the African National Congress (ANC), founded by Nelson Mandela in the wake of the Sharpeville massacre. Its mission was to fight against the South African government to brin ...

, the ANC's paramilitary wing, marked the anti-apartheid movement's shift from nonviolence to an armed struggle.

Inspired by his Christian faith and the nonviolent

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

methods used by Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British ...

, Luthuli was praised for his dedication to nonviolent resistance

Nonviolent resistance, or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, construct ...

against apartheid as well as his vision of a non-racial South African society. In 1961, Luthuli was awarded the 1960 Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

for his role in leading the nonviolent anti-apartheid movement. Luthuli's supporters brand him as a global icon of peace similar to Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

, the latter of whom was a follower and admirer of Luthuli. He formed multi-racial alliances with the South African Indian Congress

The South African Indian Congress (SAIC) was an umbrella body founded in 1921 to coordinate between political organisations representing South African Indians, Indians in the various provinces of South Africa. Its members were the Natal Indian ...

and the white Congress of Democrats, frequently drawing a backlash from Africanists in the ANC. The Africanist bloc believed that Africans should not ally themselves with other races, since Africans were the most disadvantaged race under apartheid. This schism led to the creation of the Pan-Africanist Congress.

Early life

Albert John Luthuli was born at the Solusi Mission Station, a

Albert John Luthuli was born at the Solusi Mission Station, a Seventh-day Adventist

The Seventh-day Adventist Church (SDA) is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbat ...

missionary station, in 1898 to John and Mtonya Luthuli (née

The birth name is the name of the person given upon their birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name or to the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a births registe ...

Gumede) who had settled in the Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; ) is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council claimed it to be about ...

area of Rhodesia

Rhodesia ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state, unrecognised state in Southern Africa that existed from 1965 to 1979. Rhodesia served as the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to the ...

(now Zimbabwe

file:Zimbabwe, relief map.jpg, upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Bots ...

). He was the youngest of three children and had two brothers, Mpangwa, who died at birth, and Alfred Nsusana. Luthuli's father died when he was about six months old, and Luthuli had no recollection of him. His father's death led to him being mainly raised by his mother Mtonya, who had spent her childhood in the royal household of King Cetshwayo in Zululand.

Mtonya had converted to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

and lived with the American Board Mission prior to her marriage to John Luthuli. During her stay, she learned how to read and became a dedicated reader of the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

until her death. Despite being able to read, Mtonya never learned how to write. After their marriage, Luthuli's father left Natal and went to Rhodesia during the Second Matabele War

The Second Matabele War, also known as the First Chimurenga, was fought between 1896 and 1897 in the region that later became Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The conflict was initially between the British South Africa Company and the Mata ...

to serve with the Rhodesian forces. When the war ended, John stayed in Rhodesia with a Seventh-day Adventist mission near Bulawayo and worked as an interpreter

Interpreting is translation from a spoken or signed language into another language, usually in real time to facilitate live communication. It is distinguished from the translation of a written text, which can be more deliberative and make use o ...

and evangelist. Mtonya and Alfred then travelled to Rhodesia to reunite with John, and Luthuli was born there soon after.

Luthuli's paternal grandparents, Ntaba ka Madunjini and Titsi Mthethwa, were born in the early nineteenth century and had fought against potential annexation from Shaka's Zulu Kingdom. They were also among the first converts of Aldin Grout

Aldin Grout (September 2, 1803 - February 12, 1894) was an American missionary known for his missionary activities in Zulu Kingdom, Zululand. He married Hannah Davis in November 1834 and traveled to the Cape Colony of the American Board of Commiss ...

, a missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thoma ...

from the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was among the first American Christian mission, Christian missionary organizations. It was created in 1810 by recent graduates of Williams College. In the 19th century it was the l ...

(ABM), which was based near the Umvoti River north of Durban

Durban ( ; , from meaning "bay, lagoon") is the third-most populous city in South Africa, after Johannesburg and Cape Town, and the largest city in the Provinces of South Africa, province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Situated on the east coast of South ...

. The abasemakholweni, a converted Christian community within the Umvoti Mission Station, elected Ntaba as their chief in 1860. This marked the start of a family tradition, as Ntaba's brother, son Martin, and grandson Albert were also subsequently elected as chiefs.

Youth

Around 1908 or 1909, the Seventh-day Adventists expressed their interest in beginning missionary work in Natal and requested the services of Luthuli's brother, Alfred, to work as an interpreter. Luthuli and his mother followed, and departed Rhodesia to return to South Africa. Luthuli's family settled in the

Around 1908 or 1909, the Seventh-day Adventists expressed their interest in beginning missionary work in Natal and requested the services of Luthuli's brother, Alfred, to work as an interpreter. Luthuli and his mother followed, and departed Rhodesia to return to South Africa. Luthuli's family settled in the Vryheid

Vryheid (/Abaqulusi) is a coal mining and cattle ranching town in northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Vryheid is the Afrikaans word for "freedom", while its original name of Abaqulusi reflects the AbaQulusi (Zulu), abaQulusi clan based in the loc ...

district of Northern Natal, and resided on the farm of a Seventh-day Adventist. During this time, Luthuli was responsible for tending to the missionary's mules as educational opportunities were not available. Luthuli's mother recognised his need for a formal education and sent him to live in Groutville

Groutville is a town in Ilembe District Municipality in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. Home of the late ANC leader, Chief Albert Luthuli and his wife Nokukhanya Bhengu, Home to RT Rev H. Mdelwa Hlongwane founder to The Bantu Metho ...

under the care of his uncle. Groutville was a small village inhabited predominantly by poor Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

farmers who were affiliated with the nearby mission station run by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was among the first American Christian mission, Christian missionary organizations. It was created in 1810 by recent graduates of Williams College. In the 19th century it was the l ...

(ABM). The ABM, which commenced operations in Southern Africa in 1834, was a Congregationalist organisation responsible for setting up the Umvoti Mission Station. After the death of ABM missionary Aldin Grout

Aldin Grout (September 2, 1803 - February 12, 1894) was an American missionary known for his missionary activities in Zulu Kingdom, Zululand. He married Hannah Davis in November 1834 and traveled to the Cape Colony of the American Board of Commiss ...

in 1894, the town surrounding the mission station was renamed Groutville.

Luthuli resided in the home of his uncle, Chief Martin Luthuli, and his family. Martin was the first democratically elected chief of Groutville. In 1901, Martin founded the Natal Native Congress, which would later become the Natal branch of the African National Congress. Luthuli had a pleasant childhood as his uncle Martin was guardian over many children in Groutville, which led to Luthuli having many friends of his own age. In Martin's traditional Zulu household, Luthuli completed chores expected of a Zulu boy his age such as fetching water, herding, and building fires. Additionally, he attended school for the first time. Under Martin's care, Luthuli was also provided with an early knowledge of traditional African politics and affairs, which aided him in his future career as a traditional chief.

Education

Luthuli's mother, Mtonya, returned to Groutville and Luthuli returned to her care. They lived in a brand-new house built by his brother, Alfred, on the site where their grandfather, Ntaba, had once lived. In order to be able to send her son to boarding school, Mtonya worked long hours in the fields of the land she owned. She also took in laundry from European families in the township of Stanger to earn the necessary money for school. Luthuli was educated at a local ABM mission school until 1914, and then transferred to the Ohlange Institute.

Ohlange was founded by John Dube, who was the school principal at the time Luthuli attended. Dube was educated in America but returned to South Africa to open the Ohlange Institute to provide an education to black children. He was the first President-General of the South African Native National Congress and founded the first Zulu-language newspaper, Ilanga lase Natal. Luthuli joined the ANC in 1944, partially out of respect to his former school principal.

Luthuli describes his experience at the Ohlange Institute as "rough-and-tumble." The outbreak of

Luthuli's mother, Mtonya, returned to Groutville and Luthuli returned to her care. They lived in a brand-new house built by his brother, Alfred, on the site where their grandfather, Ntaba, had once lived. In order to be able to send her son to boarding school, Mtonya worked long hours in the fields of the land she owned. She also took in laundry from European families in the township of Stanger to earn the necessary money for school. Luthuli was educated at a local ABM mission school until 1914, and then transferred to the Ohlange Institute.

Ohlange was founded by John Dube, who was the school principal at the time Luthuli attended. Dube was educated in America but returned to South Africa to open the Ohlange Institute to provide an education to black children. He was the first President-General of the South African Native National Congress and founded the first Zulu-language newspaper, Ilanga lase Natal. Luthuli joined the ANC in 1944, partially out of respect to his former school principal.

Luthuli describes his experience at the Ohlange Institute as "rough-and-tumble." The outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

led to rationing

Rationing is the controlled distribution (marketing), distribution of scarcity, scarce resources, goods, services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration, which is one's allowed portion of the resourc ...

and a scarcity of food among the African population. After attending Ohlange for only two terms, Luthuli was transferred to Edendale, a Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

school near Pietermaritzburg

Pietermaritzburg (; ) is the capital and second-largest city in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa after Durban. It was named in 1838 and is currently governed by the Msunduzi Local Municipality. The town was named in Zulu after King ...

, the capital of Natal. It was at Edendale that Luthuli participated in his first act of civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active and professed refusal of a citizenship, citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders, or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be cal ...

. He joined a protest

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration, or remonstrance) is a public act of objection, disapproval or dissent against political advantage. Protests can be thought of as acts of cooperation in which numerous people cooperate ...

against a punishment

Punishment, commonly, is the imposition of an undesirable or unpleasant outcome upon an individual or group, meted out by an authority—in contexts ranging from child discipline to criminal law—as a deterrent to a particular action or beh ...

which made boys carry large stones long distances, damaging their uniforms

A uniform is a variety of costume worn by members of an organization while usually participating in that organization's activity. Modern uniforms are most often worn by armed forces and paramilitary organizations such as police, emergency ser ...

, and leaving many unable to afford replacements. The demonstration failed and Luthuli along with the rest of the strikers were punished by the school. At Edendale, Luthuli developed a passion for teaching and went on to graduate with a teaching degree in 1917.

Teaching

Around the age of nineteen years old, Luthuli's first job after graduation came as a principal at a rural

Around the age of nineteen years old, Luthuli's first job after graduation came as a principal at a rural intermediate school

Middle school, also known as intermediate school, junior high school, junior secondary school, or lower secondary school, is an educational stage between primary school and secondary school.

Afghanistan

In Afghanistan, middle school includes g ...

in Blaauwbosch, located in the Natal midlands. The school was small, and Luthuli was the sole teacher

A teacher, also called a schoolteacher or formally an educator, is a person who helps students to acquire knowledge, competence, or virtue, via the practice of teaching.

''Informally'' the role of teacher may be taken on by anyone (e.g. w ...

working there. While teaching at Blaauwbosch, Luthuli lived with a Methodist's family. As there were no Congregational churches

Congregationalism (also Congregational Churches or Congregationalist Churches) is a Reformed Christianity, Reformed Christian (Calvinist) tradition of Protestant Christianity in which churches practice Congregationalist polity, congregational ...

around him, he became the student of a local Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

minister, the Reverend

The Reverend (abbreviated as The Revd, The Rev'd or The Rev) is an honorific style (form of address), style given to certain (primarily Western Christian, Western) Christian clergy and Christian minister, ministers. There are sometimes differen ...

Mthembu. He was confirmed in the Methodist church and later became a lay preacher

A lay preacher is a preacher who is not ordained (i.e. a layperson) and who may not hold a formal university degree in theology. Lay preaching varies in importance between religions and their sects.

Overview

Some denominations specifically disco ...

.

Luthuli proved himself to be a good teacher and the Natal Department of Education offered him a bursary in 1920 to study for a Higher Teacher's Diploma at Adams College. Following the completion of his two years of study, he was offered another bursary, this time to study at the University of Fort Hare

The University of Fort Hare () is a public university in Alice, Eastern Cape, Alice, Eastern Cape, South Africa.

It was a key institution of higher education for Africans from 1916 to 1959 when it offered a Western-style academic education to ...

in the Eastern Cape

The Eastern Cape ( ; ) is one of the nine provinces of South Africa. Its capital is Bhisho, and its largest city is Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth). Due to its climate and nineteenth-century towns, it is a common location for tourists. It is also kno ...

. He refused, as he wanted to earn a salary to take care of his ageing mother. This led him to accept a teaching position at Adams College, where he and Z. K. Matthews were among the first African teachers at the school. Luthuli taught Zulu history, music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

, and literature, and during his time as a teacher, he met his future wife, Nokukhanya Bhengu. She was also a teacher at Adams and the granddaughter of a Zulu chief. Luthuli was committed to providing quality education to African children and led the Teachers' College at Adams where he trained aspiring teachers and travelled to different institutions to teach students.

Early political activity

Natal Native Teachers' Association

Luthuli was elected as the secretary of the Natal Native Teachers' Association in 1928 and served under Z. K. Matthews' presidency. He became the president of the association in 1933. The association had three goals: improving working conditions for African teachers, motivating members to expand their skills, and encouraging members to participate in leisure activities such as

Luthuli was elected as the secretary of the Natal Native Teachers' Association in 1928 and served under Z. K. Matthews' presidency. He became the president of the association in 1933. The association had three goals: improving working conditions for African teachers, motivating members to expand their skills, and encouraging members to participate in leisure activities such as sports

Sport is a physical activity or game, often competitive and organized, that maintains or improves physical ability and skills. Sport may provide enjoyment to participants and entertainment to spectators. The number of participants in ...

, music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

and social gatherings

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives fro ...

. Despite making little progress in achieving its stated goals, the association is remembered for its opposition to the Chief Inspector for Native Education in Natal, Charles Loram, and his proposal that Africans be educated in "practical functions" and left to "develop along their own lines". Loram's position would serve as the ideological basis for the National Party's Bantu Education policy.

The Zulu Language and Cultural Society

After becoming disappointed with the Natal Native Teachers' Association's slow progress, Luthuli shifted his attention to establishing a new branch of the Teachers' Association called the Zulu Language and Cultural Society in 1935. Dinizulu, the Zulu king, served as one of the society'spatrons

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

, and John Dube served as its inaugural president. Luthuli described the purpose of the society as the preservation of what is valuable to Zulu culture while removing the inappropriate practices and beliefs. Luthuli's involvement with the society was brief, as he assumed the role of chief in Groutville

Groutville is a town in Ilembe District Municipality in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. Home of the late ANC leader, Chief Albert Luthuli and his wife Nokukhanya Bhengu, Home to RT Rev H. Mdelwa Hlongwane founder to The Bantu Metho ...

and could not remain actively involved. As a result, the society's goals changed from its original purpose. According to historian Shula Marks, the primary goal of the Zulu Language and Cultural Society was to secure government recognition of the Zulu royal family as the official leaders of the Zulu people. The preservation of Zulu tradition and custom was a secondary goal. Grants and gifts from the South African Native Affairs Department as well as the society's involvement with the Zulu royal house led to its demise as it collapsed in 1946. Seeing no real progress being made by the Teachers' Association and Zulu Society, Luthuli felt compelled to reject the government as a potential collaborator.

Cane Growers' Association

The 1936 Sugar Act limited production ofsugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecul ...

in order to keep the price from falling. A quota system was implemented, and, for African cane growers, it was severely limiting. As a response Luthuli decided to revive the Groutville Cane Growers' Association of which he became chairman. The association was used to make collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and labour rights, rights for ...

and advocacy more effective. The association achieved a significant victory: an amendment was made to the Sugar Act that allowed African cane growers to have a comprehensive quota. This meant if some farmers were unable to meet their individual quotas, others could make up the difference, ensuring that all cane would be sold and not wasted in the farms.

Luthuli then founded the Natal and Zululand Bantu Cane Growers' Association, which he served as chairman. The association brought almost all African cane growers into a single union. It had very few achievements, but one of them was securing indirect representation on the central board through a non-white advisory board that was concerned with the production, processing, and marketing of sugar. The structural inequalities and discrimination present in South African society hindered the association's efforts to promote the interests of non-white canegrowers, and they proved to be little match for the white canegrowers' associations. As with the Teachers' Association, Luthuli was disappointed with the Growers' Association's few successes. He believed that whatever political role he took part in, the stubbornness and hostility of the government would prevent any significant progress from being made. Luthuli continued to support the interests of black cane growers, and was the only black representative on the central board until 1953.

Chief of Groutville

In 1933, Luthuli was asked to succeed his uncle, Martin, as chief of the Umvoti River Reserve. He took two years to make his decision. His salary as a teacher was enough for him to send money home to support his family, but if he accepted the chieftainship he would earn less than one-fifth of his current salary. Furthermore, leaving a job at Adams College, where he worked with people of different ethnicities from all over South Africa, to become a Zulu chief appeared to be a move towards a more insular way of life. Luthuli opted for the role of chief and said he was not motivated by a desire for wealth, fame, or power. At the end of 1935, he was elected as chief and relocated toGroutville

Groutville is a town in Ilembe District Municipality in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. Home of the late ANC leader, Chief Albert Luthuli and his wife Nokukhanya Bhengu, Home to RT Rev H. Mdelwa Hlongwane founder to The Bantu Metho ...

. He commenced his duties in January 1936 and continued in the role until he was deposed by the South African government in 1952.

Some chiefs abused their power and used their close relationship with the government to act as dictators. They increased their wealth by claiming ownership of land that was not rightfully theirs, charged excessive fees for services, and accepted bribes to resolve disputes. Despite his reduced salary as a chief, Luthuli rejected corrupt practices. He embraced the concept of Ubuntu, which emphasized the humanity of all people, and governed with an inclusive and democratic approach. He believed that traditional Zulu governance was inherently democratic, with chiefs obligated to respond to the needs of their people. Luthuli was seen as a chief of his people: one community member remembered Luthuli as a "man of the people who had a very strong influence over the community. He was a people's chief." Luthuli involved women, who were considered socially inferior, in the decision-making process of his leadership. He also improved their economic status by allowing them to engage in activities such as beer brewing and running unlicensed bars, despite a government prohibition on these practices.

The position of Africans in the reserves continued to regress as a result of laws passed that controlled their social mobility. The Hertzog Bills were introduced a year after Luthuli was elected chief and were instrumental in the restriction and control of Africans. The first bill, the Natives Representation Bill, removed Africans from the voters' roll in the Cape

A cape is a clothing accessory or a sleeveless outer garment of any length that hangs loosely and connects either at the neck or shoulders. They usually cover the back, shoulders, and arms. They come in a variety of styles and have been used th ...

and created the Natives Representative Council (NRC). The second bill, the Natives Land and Trust Bill, restricted the land available to the African population of 12 million to less than 13 per cent. The remaining 87 per cent of land in South Africa was primarily reserved for the white population of approximately 3 million in 1936. Limited access to land and poor agricultural technology negatively affected the people of Groutville, and the government's policies led to a shortage of land, education, and job opportunities, which limited the potential achievements of the population. Luthuli viewed the conditions of Groutville as a microcosm that affected all black people in South Africa.

Natives Representative Council

The Natives Representative Council (NRC), an advisory body to the government, was established in 1936 with the purpose of compensating and appeasing the African population, who had lost their limited voting rights in theCape Province

The Province of the Cape of Good Hope (), commonly referred to as the Cape Province () and colloquially as The Cape (), was a province in the Union of South Africa and subsequently the Republic of South Africa. It encompassed the old Cape Co ...

due to the enactment of the Hertzog Bills.

In 1946, after John Dube's death, Luthuli became a member of the Natives Representative Council through a by-election. He brought his long-standing grievances about insufficient land for African people to the NRC meetings. In August 1946, Luthuli, along with other councilors, objected to the government's use of force to quell a large strike by African mineworkers. Luthuli accused the government of disregarding African complaints against their segregationist policies, and African councilors adjourned in protest. He would later describe the NRC as a "toy telephone" requiring him to "shout a little louder" even though no one was listening. The NRC reconvened later in 1946 but adjourned again indefinitely. Its members refused to co-operate with the government, which caused it to become ineffective. The NRC never met after that point and it was disbanded by the government in 1952.

Luthuli frequently addressed the criticism from black South Africans who believed that serving in the Native Representative Council would lead to nothing but talk, and that the NRC was a form of deceit served by the South African government

The Government of South Africa, or South African Government, is the national government of the Republic of South Africa, a parliamentary republic with a three-tier system of government and an independent judiciary, operating in a parliamentary ...

. He often agreed with these sentiments, but he and other contemporary African leaders believed that Africans should represent themselves in all structures created by the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

, even if only to change them. He was determined to take the demands and grievances of his people to the government. In the end, like others before him, Luthuli realized that his efforts were futile. In an interview with Drum Magazine

A drum magazine is a type of high-capacity magazine for firearms. Cylindrical in shape (similar to a drum), drum magazines store rounds in a spiral around the center of the magazine, facing the direction of the barrel. Drum magazines are contra ...

in May 1953, Luthuli said that joining the NRC gave White South Africans

White South Africans are South Africans of European descent. In linguistic, cultural, and historical terms, they are generally divided into the Afrikaans-speaking descendants of the Dutch East India Company's original colonists, known as Afr ...

"a last chance to prove their good faith" but they "had not done so".

President of the Natal ANC

After John Dube suffered a stroke in 1945, Allison Champion succeeded him as Natal president in 1945 after defeating conservative leader Reverend A. Mtimkulu. During the election meeting, Luthuli was unexpectedly appointed as acting chair. Serving on Champion's executive, Luthuli remained politically active. However, the Youth League's adoption of a more confrontational Programme of Action in 1949 led to growing dissatisfaction with Champion's leadership, as he prioritised Natal's separateness over the new strategy. Champion frequently failed to implement strategies and programmes set forth by the national ANC or Youth League, which made the Natal ANC lag behind. Members of the Youth League in Natal nominated Luthuli for Natal president in 1951 as they viewed him as a new brand of leadership. Luthuli and Champion were the two nominees for the election; Luthuli was elected president of the Natal ANC by a small majority. In Luthuli's first appearance as Natal ANC president at the ANC's national conference, he pleaded for more time to be given to the Natal ANC in preparation for the planned Defiance Campaign, a large act ofcivil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active and professed refusal of a citizenship, citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders, or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be cal ...

by non-white South Africans. Some members of the ANC did not support his request, and he was jeered at and labelled a coward. However, Luthuli had no prior knowledge of this planned campaign and only found out about it as he was travelling to Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein ( ; ), also known as Bloem, is the capital and the largest city of the Free State (province), Free State province in South Africa. It is often, and has been traditionally, referred to as the country's "judicial capital", alongsi ...

, where the ANC's national conference was held. Many of the details about the campaign were given to his predecessor, A.W.G Champion. The Natal ANC agreed to prepare for the Defiance Campaign, which was slated for the latter half of 1952, and participate as soon as they were ready.

Defiance Campaign

The preparations for theDefiance Campaign

The Defiance Campaign against Unjust Laws was presented by the African National Congress (ANC) at a conference held in Bloemfontein, South Africa, in December 1951 in South Africa, 1951. The Campaign had roots in events leading up the conferenc ...

began on 6 April 1952, while the campaign itself was scheduled for 26 June 1952. The preparation day served as a warm-up, with large demonstrations in cities such as Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, Port Elizabeth

Gqeberha ( , ), formerly named Port Elizabeth, and colloquially referred to as P.E., is a major seaport and the most populous city in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is the seat of the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipal ...

, East London

East London is the part of London, England, east of the ancient City of London and north of the River Thames as it begins to widen. East London developed as London Docklands, London's docklands and the primary industrial centre. The expansion of ...

, Pretoria

Pretoria ( ; ) is the Capital of South Africa, administrative capital of South Africa, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to the country.

Pretoria strad ...

, and Durban

Durban ( ; , from meaning "bay, lagoon") is the third-most populous city in South Africa, after Johannesburg and Cape Town, and the largest city in the Provinces of South Africa, province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Situated on the east coast of South ...

. Concurrently, many White South Africans observed the three-hundredth anniversary of Jan van Riebeeck's landing at the Cape

A cape is a clothing accessory or a sleeveless outer garment of any length that hangs loosely and connects either at the neck or shoulders. They usually cover the back, shoulders, and arms. They come in a variety of styles and have been used th ...

.

Beginning in June, around 8500 volunteers of the ANC and South African Indian Congress

The South African Indian Congress (SAIC) was an umbrella body founded in 1921 to coordinate between political organisations representing South African Indians, Indians in the various provinces of South Africa. Its members were the Natal Indian ...

, who were carefully selected to follow the method of nonviolent resistance

Nonviolent resistance, or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, construct ...

, deliberately set out to break the laws of apartheid. Using strategies inspired by Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British ...

, the Defiance Campaign required a strict adherence to a policy of nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

. Africans

The ethnic groups of Africa number in the thousands, with each ethnicity generally having their own language (or dialect of a language) and culture. The ethnolinguistic groups include various Afroasiatic, Khoisan, Niger-Congo, and Nilo-Sahara ...

, Indians, and Coloureds

Coloureds () are multiracial people in South Africa, Namibia and, to a smaller extent, Zimbabwe and Zambia. Their ancestry descends from the interracial mixing that occurred between Europeans, Africans and Asians. Interracial mixing in South ...

used amenities marked "Europeans Only"; they sat on benches and used reserved station platforms, carriages in trains, and post office counters. Until the end of October, the Defiance Campaign remained nonviolent and disciplined. As the movement gained momentum, violence suddenly flared. The outbreaks were not a planned part of the campaign, and many, including Luthuli, believe it to be the work of provocateur agents. The police

The police are Law enforcement organization, a constituted body of Law enforcement officer, people empowered by a State (polity), state with the aim of Law enforcement, enforcing the law and protecting the Public order policing, public order ...

, frustrated by the passive resistors, responded harshly when outbreaks of violence occurred, resulting in a chain reactions that caused dozens of Africans to be shot.

Despite the efforts of the Defiance Campaign, the government's attitude remained unchanged, and they viewed the event as " communist-inspired" and a threat to law and order. This perception led to increased security measures and tighter controls. The Criminal Law Amendment Act allowed for individuals to be banned without trial, and the Public Safety Act allowed the government to suspend rule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

. With more restrictions put in place, the ANC leaders decided to end the campaign in January 1953.

Prior to the campaign, the ANC's membership numbered 25,000 in 1951. After the conclusion of the Campaign in 1953, it had increased to 100,000. For the first time African, Indian, and Coloured communities across the country cooperated on a national scale. The Defiance Campaign was also praised for its absence of violence. Even though there were thousands of protesters and some incidents of violence occurred, the low level of violence overall was a notable accomplishment. Due to Luthuli's role in the Defiance Campaign as president of the Natal ANC, he was given an ultimatum by the government to choose between his work as a chief at Umvoti or his affiliation with the ANC. He refused to choose, and the government deposed him as chief in November 1952.

President-General of the ANC

In December 1952, Albert Luthuli was elected president general of the ANC with the support of theANC Youth League

The African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL) is the youth wing of the African National Congress (ANC). As set out in its constitution, the ANC Youth League is led by a National Executive Committee (NEC) and a National Working Committee (N ...

(ANCYL) and African communists. Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela ( , ; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa f ...

was elected as his deputy. The ANCYL's support for Luthuli reflected its desire for a leader who would enact its programmes and goals, and marked a pattern of younger, more militant members within the ANC ousting presidents they deemed inflexible. The ANCYL had previously succeeded in removing Xuma, Moroka, and Champion when they no longer met their expectations.

Luthuli led the ANC in its most difficult years; many of his executive members, such as Secretary-General Walter Sisulu

Walter Max Ulyate Sisulu (18 May 1912 – 5 May 2003) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and member of the African National Congress (ANC). Between terms as ANC Secretary-General (1949–1954) and ANC ...

, Moses Kotane, JB Marks, and David Bopape were either to be banned or imprisoned. The 1950s witnessed the erosion of black civil liberties, through the Treason Trial and the passage of the Suppression of Communism Act

The Suppression of Communism Act, 1950 (Act No. 44 of 1950), renamed the Internal Security Act in 1976, was legislation of the national government in apartheid South Africa which formally banned the South African Communist Party, Communist Party ...

, which gave the police power to suppress government critics.

First ban

On 30 May 1953, the government banned Luthuli for a year, prohibiting him from attending any political or public gatherings and from entering major cities. He was restricted to small towns and private meetings for the rest of 1953. The Riotous Assemblies Act and the Criminal Law Amendment Act provided the legal framework for the issuing of banning orders. It was the first of four banning orders that Luthuli would receive as President-General of the ANC. Following the expiration of his ban, Luthuli continued to attend and speak at anti-apartheid conferences.Second ban

In mid-1954, following the expiration of his ban, Luthuli was due to lead a protest in the Transvaal against the Western Areas Removals, a government scheme where close to 75,000 Africans were forced to move fromSophiatown

Sophiatown , also known as Sof'town or Kofifi, is a suburb of Johannesburg, South Africa. Sophiatown was a poor multi-racial area and a black cultural hub that was destroyed under apartheid. It produced some of South Africa's most famous writ ...

and other townships. As he stepped off his plane in Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and Xhosa language, Xhosa: eGoli ) (colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, Jo'burg or "The City of Gold") is the most populous city in South Africa. With 5,538,596 people in the City of Johannesburg alon ...

, the Special Branch

Special Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security and Intelligence (information gathering), intelligence in Policing in the United Kingdom, British, Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, ...

handed him new banning orders, not only prohibiting the attendance of meetings but confining him to the Groutville

Groutville is a town in Ilembe District Municipality in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. Home of the late ANC leader, Chief Albert Luthuli and his wife Nokukhanya Bhengu, Home to RT Rev H. Mdelwa Hlongwane founder to The Bantu Metho ...

area for two years until July 1956.

Congress of the People and Freedom Charter

In 1953, Z. K. Matthews proposed a large democratic convention, to be known as the Congress of the People, where all South Africans would be invited to create a

In 1953, Z. K. Matthews proposed a large democratic convention, to be known as the Congress of the People, where all South Africans would be invited to create a Freedom Charter

The Freedom Charter was the statement of core principles of the South African Congress Alliance, which consisted of the African National Congress (ANC) and its allies: the South African Indian Congress, the South African Congress of Democrats ...

. Despite complaints within the ANC from Africanists who believed the ANC should not work with other races, a multiracial organization, the Congress Alliance

The Congress Alliance was an anti-apartheid political coalition formed in South Africa in the 1950s. Led by the African National Congress, the CA was multi-racial in makeup and committed to the principle of majority rule.

Congress of the Peopl ...

, was created as part of the preparation for the Congress of the People. The alliance was led by the ANC and included the South African Indian Congress

The South African Indian Congress (SAIC) was an umbrella body founded in 1921 to coordinate between political organisations representing South African Indians, Indians in the various provinces of South Africa. Its members were the Natal Indian ...

, Coloured Peoples Conference, Federation of South African Women

The Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) was a political lobby group formed in 1954. At FEDSAW's inaugural conference, a Women's Charter was adopted. Its founding was spear-headed by Lillian Ngoyi.

Introduction

The Federation of South Afri ...

, Congress of Trade Unions, and the Congress of Democrats. Luthuli viewed the multiracial organisation as a way to bring freedom to South Africa. After convening a secret meeting in December 1954 due to Luthuli's ban, the Congress of the People took place in Kliptown, Johannesburg, in June 1955.

Inspired by the values held in the United States Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America in the original printing, is the founding document of the United States. On July 4, 1776, it was adopted unanimously by the Second Continen ...

and the UN Declaration of Human Rights, the Congress of the People developed the Freedom Charter

The Freedom Charter was the statement of core principles of the South African Congress Alliance, which consisted of the African National Congress (ANC) and its allies: the South African Indian Congress, the South African Congress of Democrats ...

, a list of demands for a democratic, multi-racial, and free South Africa. While well-received by the attendants of the Congress of the People, the Africanist bloc of the ANC rejected it. They opposed the multiracial nature of the charter and what they perceived as communist principles. Although Luthuli recognised the socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

clauses in the Freedom Charter, he rejected any comparison to the communist ideology of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. The ANC ratified the Charter at a conference one year after it was ratified by the Congress of the People.

Luthuli was not able to attend the Congress of the People or the framing of the Freedom Charter due to a stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

and heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

as well as the banning order that confined him to Groutville. In his absence, he was bestowed the honour of the Isitwalandwe, which is awarded to individuals who have made significant contributions in the fight for freedom in South Africa.

Treason Trial

After his second banning order expired in July 1956, he was arrested on 5 December and detained during the preliminary Treason Trial hearings in 1957. Luthuli was one of 156 leaders who were arrested on charges of

After his second banning order expired in July 1956, he was arrested on 5 December and detained during the preliminary Treason Trial hearings in 1957. Luthuli was one of 156 leaders who were arrested on charges of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its d ...

due to their opposition to apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

and the Nationalist Party government. High treason carried the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

. One of the main charges against the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

leaders were that they were involved in a communist conspiracy to overthrow the government. Anti-apartheid activists were often accused of being communists, and Luthuli was accustomed to such accusations and frequently dismissed them.

The charges brought against the accused covered the period from 1 October 1952 to 13 December 1956, which included events such as the Defiance Campaign

The Defiance Campaign against Unjust Laws was presented by the African National Congress (ANC) at a conference held in Bloemfontein, South Africa, in December 1951 in South Africa, 1951. The Campaign had roots in events leading up the conferenc ...

, Sophiatown

Sophiatown , also known as Sof'town or Kofifi, is a suburb of Johannesburg, South Africa. Sophiatown was a poor multi-racial area and a black cultural hub that was destroyed under apartheid. It produced some of South Africa's most famous writ ...

removals protest, and the Congress of the People. Following the preparatory examination period that began on 19 December 1956, all defendants were released on bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Court bail may be offered to secure the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when ...

. The pre-trial examination concluded in December 1957, resulting in charges being dropped against 65 of the accused, including Luthuli who was acquitted

In common law jurisdictions, an acquittal means that the criminal prosecution has failed to prove that the accused is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt of the charge presented. It certifies that the accused is free from the charge of an o ...

. The trial

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, w ...

for the remaining 91 accused individuals began in August 1958 as the Treason Trial commenced. By 1959, only thirty of the accused remained. The trial concluded on 29 March 1961 as all of the remaining defendants were found not guilty.

Many of the lawyers

A lawyer is a person who is qualified to offer advice about the law, draft legal documents, or represent individuals in legal matters.

The exact nature of a lawyer's work varies depending on the legal jurisdiction and the legal system, as wel ...

who defended the accused were drawn by Luthuli and Z. K. Matthews being on trial. Their involvement contributed to raising global awareness and support for the accused. The impression that Luthuli made on the foreigners who came to observe the trial led him to be suggested for the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

.

Third ban and banning of the ANC

On 25 May 1959, the government served Luthuli his third banning order, which lasted for five years. This ban prevented Luthuli from attending any meeting held within South Africa and confined him to his home district. Luthuli's democratic values had been recognised by many white South Africans, and he had gained a minor celebrity status among some white people, which caused the government to view him with more contempt. When news of his ban spread, supporters of all races gathered to bid farewell to Luthuli. While Luthuli was still under a banning order, the ANC, led by Luthuli, announced an anti-pass campaign starting at the end of March 1960. The recently created Pan-Africanist Congress, who split from the ANC because of their opposition to the ANC's multi-racial alliances, decided to jump ahead of the ANC's planned protest by ten days. On 21 March the PAC called for all African men to go to police stations and hand over their passbooks. The peaceful march inSharpeville

Sharpeville (also spelled Sharpville) is a township situated between two large industrial cities, Vanderbijlpark and Vereeniging, in southern Gauteng, South Africa. Sharpeville is one of the oldest of six townships in the Vaal Triangle. It was ...

resulted in sixty-nine people killed by police fire. Additionally, three people were also killed in Langa. Luthuli and several other ANC leaders ceremonially burned their passbooks in protest against the Sharpeville massacre. Following a state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state before, during, o ...

and the passing of the Unlawful Organisations Act, the government banned the PAC and the ANC. Luthuli and other political leaders were arrested and found guilty of burning their passbooks. In August, Luthuli was fined 100 pounds and initially sentenced to six months in jail

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol, penitentiary, detention center, correction center, correctional facility, or remand center, is a facility where people are imprisoned under the authority of the state, usually as punishment for various cr ...

. However, in September, this was later reduced to a three year suspended sentence

A suspended sentence is a sentence on conviction for a criminal offence, the serving of which the court orders to be deferred in order to allow the defendant to perform a period of probation. If the defendant does not break the law during that ...

on the condition that he would not be found guilty of a similar offense during that time.

Following his return from prison to Groutville

Groutville is a town in Ilembe District Municipality in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. Home of the late ANC leader, Chief Albert Luthuli and his wife Nokukhanya Bhengu, Home to RT Rev H. Mdelwa Hlongwane founder to The Bantu Metho ...

, Luthuli's power began to wane due to the banning of the ANC and the banning and imprisonment of supporting leaders, a decline in his health since his stroke and heart attack, and the rise of members in the ANC advocating for an armed struggle. Duma Nokwe, Walter Sisulu

Walter Max Ulyate Sisulu (18 May 1912 – 5 May 2003) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and member of the African National Congress (ANC). Between terms as ANC Secretary-General (1949–1954) and ANC ...

, and Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela ( , ; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa f ...

, who had provided leadership for the ANC during South Africa's state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state before, during, o ...

, were determined to steer the ANC in a new direction. In May 1961, following a strike

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

* Hobart Huson, author of several drug related books

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

* Airstrike, ...

, they believed that " traditional weapons of protest… were no longer appropriate." They constantly evaluated whether the conditions were favourable to launch an armed resistance.

uMkhonto we Sizwe

In June 1961, during a National Executive Committee Working Group session, Mandela proposed that the ANC adopt a self-defense platform. With the government's bans on the ANC and nonviolent protests, Mandela believed waiting for revolutionary conditions to arise, which was favoured by communist members, was not an option. Instead, the ANC had to adapt to their new underground conditions and draw inspiration from successful uprisings in

In June 1961, during a National Executive Committee Working Group session, Mandela proposed that the ANC adopt a self-defense platform. With the government's bans on the ANC and nonviolent protests, Mandela believed waiting for revolutionary conditions to arise, which was favoured by communist members, was not an option. Instead, the ANC had to adapt to their new underground conditions and draw inspiration from successful uprisings in Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

, and Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

. Mandela argued that the ANC was the only anti-apartheid organisation that had the capacity to adopt an armed struggle and if they didn't take the lead, they would fall behind in their own movement.

In July 1961, the ANC and Congress Alliance met to hold debates during an ANC NEC meeting surrounding the feasibility of Nelson Mandela's proposal of armed self-defence. Luthuli did not support an armed struggle as he believed the ANC members were ill-prepared without modern firearms and battlefield experience. In a following meeting a day later, a contentious back-and-forth arose. Supporters of armed defence believed the ANC was afraid and running from a physical fight while others believed counter-violence would provoke the government into arresting and killing them.

While Luthuli did not support an armed struggle, he also did not oppose it. According to Mandela, Luthuli suggested "two separate streams of the struggle": the ANC, which would remain nonviolent, and a "military movement hat

A hat is a Headgear, head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorpor ...

should be a separate and independent organ, linked to the ANC and under the overall control of the ANC, but fundamentally autonomous". The formation of uMkhonto we Sizwe

uMkhonto weSizwe (; abbreviated MK; ) was the paramilitary wing of the African National Congress (ANC), founded by Nelson Mandela in the wake of the Sharpeville massacre. Its mission was to fight against the South African government to brin ...

was part of a larger shift towards armed resistance in southern Africa. Other militant organisations were created in South West Africa

South West Africa was a territory under Union of South Africa, South African administration from 1915 to 1990. Renamed ''Namibia'' by the United Nations in 1968, Independence of Namibia, it became independent under this name on 21 March 1990. ...

, Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

, and Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing British Crown colony in Southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally known as South ...

in the early 1960s. The stated goal of uMkhonto we Sizwe was to cripple South Africa's economy without bloodshed and force the government into negotiating. Mandela explained to Luthuli that only attacks against military installations, transportation links, and power plants would be carried out, which eased Luthuli's fears of the potential of loss of life.

Nobel Peace Prize

In October 1961, during his most severe ban yet, Luthuli received the 1960

In October 1961, during his most severe ban yet, Luthuli received the 1960 Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

, becoming the first African person to win the award. He was awarded the prize for his use of nonviolent methods in his fight against racial discrimination. His nomination was put forward by Andrew Vance McCracken, the editor of ''Advance'', a Congregational Church

Congregationalism (also Congregational Churches or Congregationalist Churches) is a Reformed Christian (Calvinist) tradition of Protestant Christianity in which churches practice congregational government. Each congregation independently a ...

magazine

A magazine is a periodical literature, periodical publication, print or digital, produced on a regular schedule, that contains any of a variety of subject-oriented textual and visual content (media), content forms. Magazines are generally fin ...

. His name was supported by Norwegian Socialist MPs who nominated him in February 1961. He travelled to Oslo

Oslo ( or ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of 1,064,235 in 2022 ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

, to receive the award with his wife and his secretary, Massabalala Yengwa.

The Nobel Prize transformed Luthuli from being relatively unknown to a global celebrity. He received congratulatory letters from leaders of 25 countries, including U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

John F. Kennedy. In Groutville