Al-Qarawiyyin University, Fes, Morocco - Var 132 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The University of al-Qarawiyyin (), also written Al-Karaouine or Al Quaraouiyine, is a university located in

Starting in the late 13th century, and especially in the 14th century, the Marinid dynasty was responsible for constructing a number of formal madrasas in the areas around al-Qarawiyyin's main building. The first of these was the

Starting in the late 13th century, and especially in the 14th century, the Marinid dynasty was responsible for constructing a number of formal madrasas in the areas around al-Qarawiyyin's main building. The first of these was the  Students were male, but traditionally it has been said that "facilities were at times provided for interested women to listen to the discourse while accommodated in a special gallery (''

Students were male, but traditionally it has been said that "facilities were at times provided for interested women to listen to the discourse while accommodated in a special gallery (''

In 1947, al-Qarawiyyin was integrated into the state educational system, and women were first admitted to study there during the 1940s. In 1963, after Moroccan independence, al-Qarawiyyin was officially transformed by

In 1947, al-Qarawiyyin was integrated into the state educational system, and women were first admitted to study there during the 1940s. In 1963, after Moroccan independence, al-Qarawiyyin was officially transformed by

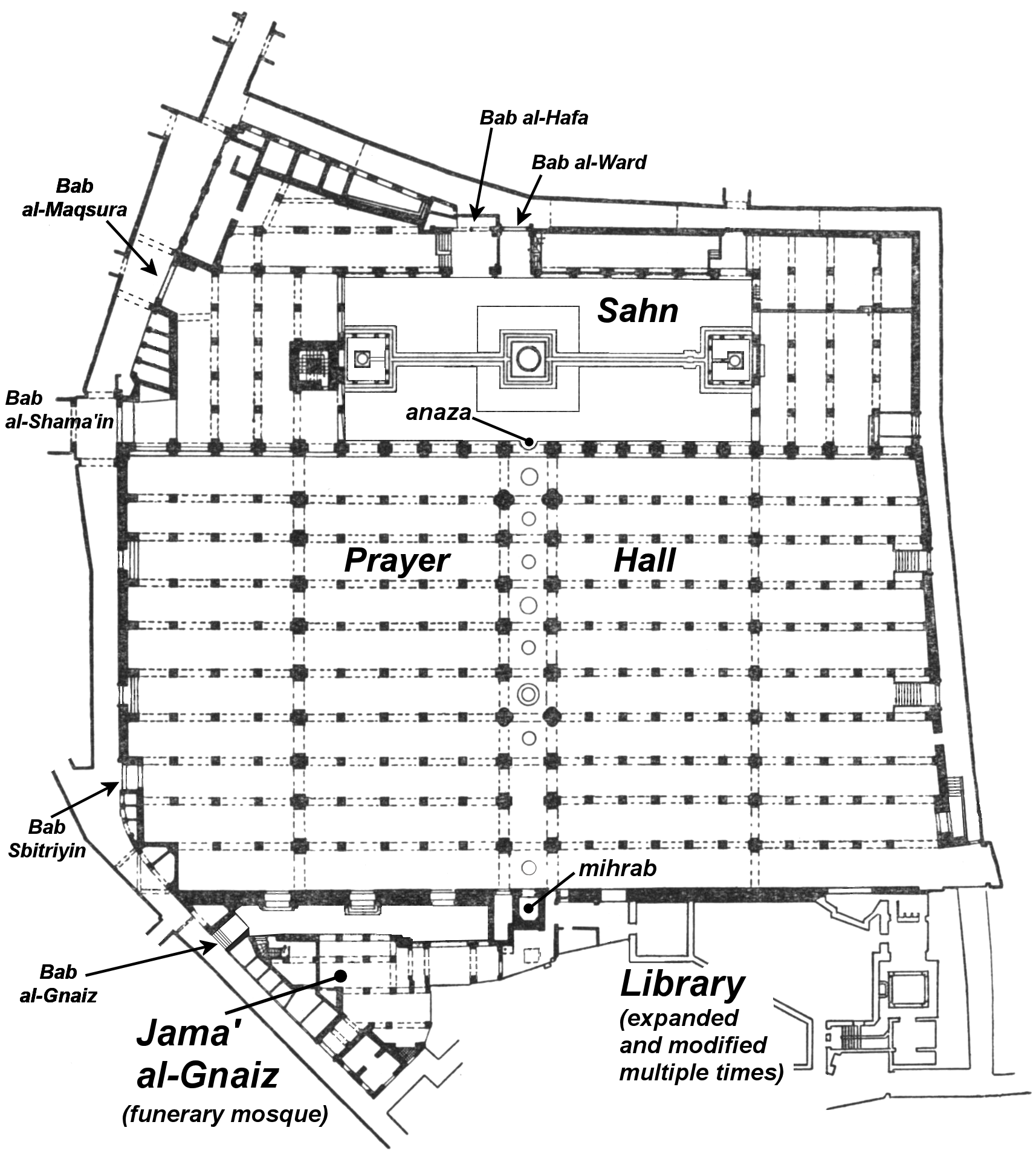

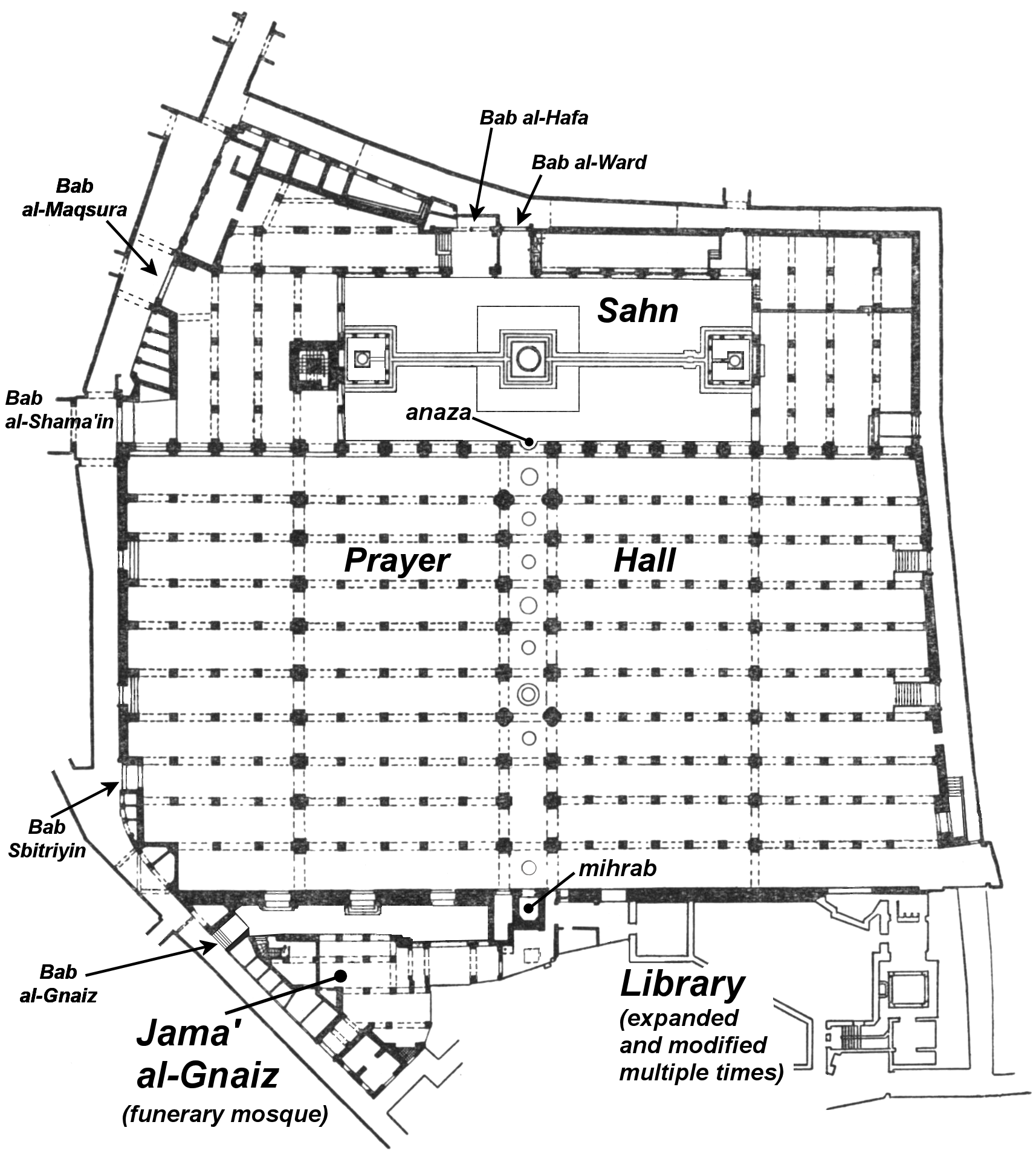

Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque was founded in the 9th century, but its present form is the result of a long historical evolution over the course of more than 1,000 years. Successive dynasties expanded the mosque until it became the largest in

Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque was founded in the 9th century, but its present form is the result of a long historical evolution over the course of more than 1,000 years. Successive dynasties expanded the mosque until it became the largest in

The new expansion of the mosque involved not only a new ''mihrab'' in the middle of the new southern wall, but also the reconstruction or embellishment of the prayer hall's central nave (the arches along its central axis, in a line perpendicular to the southern wall and to the other rows of arches) leading from the courtyard to the ''mihrab''. This involved not only embellishing some of the arches with new forms but also adding a series of highly elaborate cupola ceilings composed in ''

The new expansion of the mosque involved not only a new ''mihrab'' in the middle of the new southern wall, but also the reconstruction or embellishment of the prayer hall's central nave (the arches along its central axis, in a line perpendicular to the southern wall and to the other rows of arches) leading from the courtyard to the ''mihrab''. This involved not only embellishing some of the arches with new forms but also adding a series of highly elaborate cupola ceilings composed in ''

File:Dar al-Muwaqqit.jpg, View of the '' The galleries around the ''sahn'' were also rebuilt or repaired in 1283 and 1296–97, while at the entrance from the courtyard to the prayer hall (leading to the central nave of the mihrab), a decorative wooden screen, called the ''anaza,'' was installed in 1289 and acted as a symbolic "outdoor" or "summer" mihrab for prayers in the courtyard. The

File:Qarawiyyin Mosque Bab al-Ward vestibule dome DSCF2971 cropped.jpg, Marinid decoration in the cupola over the vestibule of ''Bab al-Ward'', the central northern gate of the mosque

File:Fes, fez, فاس (9284407750).jpg, Inner façade of ''Bab al-Ward'', with Marinid-era stucco embellishment

File:Al-Karaouine University (Al-Qarawiyyin) in the city of Fes, Morocco (Image 8 of 9).jpg, The wooden '' A number of ornate metal chandeliers hanging in the mosque's prayer hall date from the Marinid era. Three of them were made from church bells which Marinid craftsmen used as a base onto which they grafted ornate copper fittings. The largest of them, installed in the mosque in 1337, was a bell brought back from

The ''mihrab'', which dates from the Almoravid (12th-century) expansion, is decorated with carved and painted stucco, as well as several windows of coloured glass. The ''mihrab'' niche itself is a small alcove which is covered by a small dome of ''muqarnas'' (stalactite or honeycomb-like sculpting). On each side of the ''mihrab''

The ''mihrab'', which dates from the Almoravid (12th-century) expansion, is decorated with carved and painted stucco, as well as several windows of coloured glass. The ''mihrab'' niche itself is a small alcove which is covered by a small dome of ''muqarnas'' (stalactite or honeycomb-like sculpting). On each side of the ''mihrab''

The courtyard (''sahn'') is rectangular, surrounded by the prayer hall on three sides and by a gallery to the north. The floor is paved with typical Moroccan mosaic tiles (''

The courtyard (''sahn'') is rectangular, surrounded by the prayer hall on three sides and by a gallery to the north. The floor is paved with typical Moroccan mosaic tiles (''

"University"

2012, retrieved 26 July 2012 Other sources also refer to the historical or

Universite Quaraouiyine – Fes

(French)

Al Qaraouiyine Rehabilitation at ArchNet

(includes pictures of the interior, the minbar, and other architectural elements)

Manar al-Athar Digital Photo Archive

(includes pictures of the interior, including the mihrab area)

The minbar of the al-Qarawīyīn Mosque at Qantara-Med

(includes pictures of the minbar and the mihrab area)

360-degree view of the central nave of the mosque

in front of the mihrab, posted on Google Maps

Virtual tour of the Qarawiyyin Mosque

360-degree views of the mosque's interior {{DEFAULTSORT:Qarawiyyin, University of al University of al-Qarawiyyin, Buildings and structures completed in 1135 Madrasas in Fez, Morocco Universities in Morocco Islamic universities and colleges Educational institutions established in the 9th century 859 establishments, Madrasa of Al-Karaouine Mosques in Fez, Morocco 9th-century establishments in Morocco Almoravid architecture Marinid architecture Saadian architecture

Fez, Morocco

Fez () or Fes (; ) is a city in northern inland Morocco and the capital of the Fez-Meknes, Fez-Meknes administrative region. It is one of the List of cities in Morocco, largest cities in Morocco, with a population of 1.256 million, according to ...

. It was founded as a mosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

by Fatima al-Fihri

Fatima bint Muhammad al-Fihriya al-Qurashiyya (), known in shorter form as Fatima al-Fihriya or Fatima al-Fihri, was an Arab woman who is credited with founding the al-Qarawiyyin Mosque in 857–859 CE in Fez, Morocco. She is also known as (" ...

in 857–859 and subsequently became one of the leading spiritual and educational centers of the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of scientific, economic, and cultural flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century.

This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign o ...

. It was incorporated into Morocco's modern state university

A public university, state university, or public college is a university or college that is State ownership, owned by the state or receives significant funding from a government. Whether a national university is considered public varies from o ...

system in 1963 and officially renamed "University of Al Quaraouiyine" two years later. The mosque building itself is also a significant complex of historical Moroccan and Islamic architecture

Islamic architecture comprises the architectural styles of buildings associated with Islam. It encompasses both Secularity, secular and religious styles from the early history of Islam to the present day. The Muslim world, Islamic world encompasse ...

that features elements from many different periods of Moroccan history. Scholars consider al-Qarawiyyin to have been effectively run as a madrasa

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , ), sometimes Romanization of Arabic, romanized as madrasah or madrassa, is the Arabic word for any Educational institution, type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whet ...

until after World War II.Lulat, Y. G.-M.: ''A History Of African Higher Education From Antiquity To The Present: A Critical Synthesis Studies in Higher Education'', Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005, , p. 70: Shillington, Kevin: ''Encyclopedia of African History

The ''Encyclopedia of African History'' is a three-volume work dedicated to African history. It was edited by Kevin Shillington and published in New York City by Routledge in November 2004. The Library of Congress

The Library of Congress ...

'', Vol. 2, Fitzroy Dearborn, 2005, , p. 1025:

Many scholars distinguish this status from the status of "university", which they view as a distinctly Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

an invention.Makdisi, George: "Madrasa and University in the Middle Ages", ''Studia Islamica

''Studia Islamica'' is a biannual peer-reviewed academic journal covering Islamic studies focusing on the history, religion, law, literature, and language of the Muslim world, primarily of the Southwest Asian and Mediterranean regions. The editor- ...

'', No. 32 (1970), pp. 255–264 (255f.): They date al-Qarawiyyin's transformation from a madrasa into a university to its modern reorganization in 1963.Park, Thomas K.; Boum, Aomar: ''Historical Dictionary of Morocco'', 2nd ed., Scarecrow Press, 2006, , p. 348 UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

and the ''Guinness World Records

''Guinness World Records'', known from its inception in 1955 until 1999 as ''The Guinness Book of Records'' and in previous United States editions as ''The Guinness Book of World Records'', is a British reference book published annually, list ...

'', have cited al-Qarawiyyin as the oldest university or oldest continually operating higher learning

Tertiary education (higher education, or post-secondary education) is the educational level following the completion of secondary education.

The World Bank defines tertiary education as including universities, colleges, and vocational schools ...

institution in the world.

Education at the University of al-Qarawiyyin concentrates on the Islamic religious and legal sciences with a heavy emphasis on, and particular strengths in, Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic or Quranic Arabic () is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notably in Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphate, Abbasid literary texts such as poetry, e ...

grammar/linguistics and ''Maliki

The Maliki school or Malikism is one of the four major madhhab, schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas () in the 8th century. In contrast to the Ahl al-Hadith and Ahl al-Ra'y schools of thought, the ...

'' Sharia

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' ...

, though lessons on non-Islamic subjects are also offered to students. Teaching is still delivered in the traditional methods. The university is attended by students from all over Morocco and Muslim West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

, with some also coming from further abroad. Women were first admitted to the institution in the 1940s.

Name

TheArabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

name of the university means "University of the People from Kairouan

Kairouan (, ), also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan ( , ), is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by the Umayyads around 670, in the period of Caliph Mu'awiya (reigned 661� ...

". Factors such as the provenance of Fatima al-Fihri

Fatima bint Muhammad al-Fihriya al-Qurashiyya (), known in shorter form as Fatima al-Fihriya or Fatima al-Fihri, was an Arab woman who is credited with founding the al-Qarawiyyin Mosque in 857–859 CE in Fez, Morocco. She is also known as (" ...

ya's family in Tunisia, the presence of the letter ''Qāf

Qoph is the nineteenth Letter (alphabet), letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician alphabet, Phoenician ''qōp'' 𐤒, Hebrew alphabet, Hebrew ''qūp̄'' , Aramaic alphabet, Aramaic ''qop'' 𐡒, Syriac alphabet, Syriac ''qōp̄'' ܩ, ...

'' ( ق) – a voiceless uvular plosive

The voiceless uvular plosive or stop is a type of consonantal sound, used in some spoken languages. It is pronounced like a voiceless velar plosive , except that the tongue makes contact not on the soft palate but on the uvula. The symbol in the ...

which has no equivalent in European languages – the () triphthong

In phonetics, a triphthong ( , ) (from Greek , ) is a monosyllabic vowel combination involving a quick but smooth movement of the articulator from one vowel quality to another that passes over a third. While "pure" vowels, or monophthongs, are ...

in the university's name, and the French colonization

The French colonial empire () comprised the overseas colonies, protectorates, and mandate territories that came under French rule from the 16th century onward. A distinction is generally made between the "First French colonial empire", that ex ...

of Morocco have resulted in a number of different orthographies for the romanization

In linguistics, romanization is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Latin script, Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and tra ...

of the university's name, including ''al-Qarawiyyin'', a standard anglicization

Anglicisation or anglicization is a form of cultural assimilation whereby something non-English becomes assimilated into or influenced by the culture of England. It can be sociocultural, in which a non-English place adopts the English languag ...

; ''Al Quaraouiyine'', following French orthography

French orthography encompasses the spelling and punctuation of the French language. It is based on a combination of phonemic and historical principles. The spelling of words is largely based on the pronunciation of Old French –1200 AD, and has ...

; and ''Al-Karaouine'', another rendering using French orthography.

History

Foundation of the mosque

In the 9th century, Fez was the capital of theIdrisid dynasty

The Idrisid dynasty or Idrisids ( ') were an Arabs, Arab Muslims, Muslim dynasty from 788 to 974, ruling most of present-day Morocco and parts of present-day western Algeria. Named after the founder, Idris I of Morocco, Idris I, the Idrisids were ...

, considered to be the first Moroccan Islamic state. According to one of the major early sources on this period, the ''Rawd al-Qirtas

''Rawḍ al-Qirṭās'' () short for ''Kitāb al-ānīs al-muṭrib bi-rawḍ al-qirṭās fī ākhbār mulūk al-maghrab wa tārīkh madīnah Fās'' ('', The Entertaining Companion Book in the Gardens of Pages from the Chronicle of the Kings of ...

'' by Ibn Abi Zar

Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Abī Zarʿ al-Fāsī () (d. between 1310 and 1320) is the commonly presumed original author of the popular and influential medieval history of Morocco known as '' Rawd al-Qirtas'',''Encyclopedia of Arabic literature: A ...

, al-Qarawiyyin was founded as a mosque in 857 or 859 by Fatima al-Fihri

Fatima bint Muhammad al-Fihriya al-Qurashiyya (), known in shorter form as Fatima al-Fihriya or Fatima al-Fihri, was an Arab woman who is credited with founding the al-Qarawiyyin Mosque in 857–859 CE in Fez, Morocco. She is also known as (" ...

, the daughter of a wealthy merchant named Mohammed al-Fihri. Meri, Josef W. (ed.): '' Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia'', Vol. 1, A–K, Routledge, , p. 257 (entry "Fez") The al-Fihri family had migrated from Kairouan

Kairouan (, ), also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan ( , ), is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by the Umayyads around 670, in the period of Caliph Mu'awiya (reigned 661� ...

(hence the name of the mosque), Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

to Fez in the early 9th century, joining a community of other migrants from Kairouan who had settled in a western district of the city. Fatima and her sister Mariam, both of whom were well educated, inherited a large amount of money from their father. Fatima vowed to spend her entire inheritance to build a mosque suitable for her community. Similarly, her sister Mariam is also reputed to have founded al-Andalusiyyin Mosque

The Mosque of the Andalusians or Al-Andalusiyyin Mosque (), sometimes also called the Andalusian Mosque, is a major historic mosque in Fes el Bali, the old medina quarter of Fez, Morocco. The mosque was founded in 859–860, making it one of th ...

the same year.

This foundation narrative has been questioned by some modern historians who see the symmetry of two sisters founding the two most famous mosques of Fez as too convenient and likely originating from a legend. Ibn Abi Zar is also judged by contemporary historians to be a relatively unreliable source. One of the biggest challenges to this story is a foundation inscription that was rediscovered during renovations to the mosque in the 20th century, previously hidden under layers of plaster for centuries. This inscription, carved onto cedar wood panels and written in a Kufic script

The Kufic script () is a style of Arabic script, that gained prominence early on as a preferred script for Quran transcription and architectural decoration, and it has since become a reference and an archetype for a number of other Arabic scripts ...

very similar to foundation inscriptions in 9th-century Tunisia, was found on a wall above the probable site of the mosque's original ''mihrab

''Mihrab'' (, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the ''qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "''qibla'' wall".

...

'' (prior to the building's later expansions). The inscription, recorded and deciphered by Gaston Deverdun, proclaims the foundation of "this mosque" () by Dawud ibn Idris (a son of Idris II

Idrīs ibn Idrīs () known as Idris II () and Idrīs al-Azhar/al-Aṣghar () (August 791 – August 828), was the son of Idris I of Morocco, Idris I, the founder of the Idrisid dynasty in Morocco. He was born in Volubilis, Walīlī two months aft ...

who governed this region of Morocco at the time) in ''Dhu al-Qadah

Dhu al-Qa'dah (, ', ), also spelled Dhu al-Qi'dah or Zu al-Qa'dah, is the eleventh month in the Islamic calendar.

It could possibly mean "possessor or owner of the sitting and seating place" - the space occupied while sitting or the manner of t ...

'' 263 AH (July–August of 877 CE). Deverdun suggested the inscription may have come from another unidentified mosque and was moved here at a later period (probably 15th or 16th century) when the veneration of the Idrisids was resurgent in Fez, and such relics would have held enough religious significance to be reused in this way. However, Chafik Benchekroun argued more recently that a more likely explanation is that this inscription is the original foundation inscription of al-Qarawiyyin itself and that it might have been covered up in the 12th century just before the Almohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; or or from ) or Almohad Empire was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) and North Africa (the Maghreb).

The Almohad ...

' arrival in the city. Based on this evidence and on the many doubts about Ibn Abi Zar's narrative, he argues that Fatima al-Fihri is quite possibly a legendary figure rather than a historical one. Péter T. Nagy has also stated that the uncovered foundation inscription is more convincing evidence of the mosque's original foundation date than the traditional historiographical narrative.

Early history

Some scholars suggest that some teaching and instruction probably took place at al-Qarawiyyin Mosque from a very early period or from its beginning. Major mosques in the early Islamic period were typically multi-functional buildings where teaching and education took place alongside other religious and civic activities. The al-Andalusiyyin Mosque, in the district across theriver

A river is a natural stream of fresh water that flows on land or inside Subterranean river, caves towards another body of water at a lower elevation, such as an ocean, lake, or another river. A river may run dry before reaching the end of ...

, may have also served a similar role up until at least the Marinid

The Marinid dynasty ( ) was a Berber Muslim dynasty that controlled present-day Morocco from the mid-13th to the 15th century and intermittently controlled other parts of North Africa (Algeria and Tunisia) and of the southern Iberian Peninsula ...

period, though it never equaled the Qarawiyyin's later prestige. It is unclear at what time al-Qarawiyyin began to act more formally as an educational institution, partly because of the limited historical sources that pertain to its early period. The most relevant major historical texts like the ''Rawd al-Qirtas

''Rawḍ al-Qirṭās'' () short for ''Kitāb al-ānīs al-muṭrib bi-rawḍ al-qirṭās fī ākhbār mulūk al-maghrab wa tārīkh madīnah Fās'' ('', The Entertaining Companion Book in the Gardens of Pages from the Chronicle of the Kings of ...

'' by Ibn Abi Zar

Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Abī Zarʿ al-Fāsī () (d. between 1310 and 1320) is the commonly presumed original author of the popular and influential medieval history of Morocco known as '' Rawd al-Qirtas'',''Encyclopedia of Arabic literature: A ...

and the ''Zahrat al-As'' by Abu al-Hasan Ali al-Jazna'i do not provide any clear details on the history of teaching at the mosque, though al-Jazna'i (who lived in the 14th century) mentions that teaching had taken place there before his time. Otherwise, the earliest mentions of ''halaqa

Halaqa () in Islamic terminology refers to a religious gathering or meeting for the study of Islam and the Quran. Generally, there are one or more primary speakers that present the designated topic(s) of the halaqa while others sit around them (i ...

'' (circles) for learning and teaching may not have been until the 10th or the 12th century. Historian Abdelhadi Tazi

Abdelhadi Tazi (June 15, 1921 – April 2, 2015) was a scholar, writer, historian and former Moroccan ambassador in various countries.

Early life

Tazi was born in Fes, Morocco, and attended primary and secondary studies in his hometown. Si ...

indicates the earliest clear evidence of teaching at al-Qarawiyyin in 1121. Moroccan historian Mohammed Al-Manouni believes that the mosque acquired its function as a teaching institution during the reign of the Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty () was a Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire that stretched over the western Maghreb and Al-Andalus, starting in the 1050s and lasting until its fall to the Almo ...

(1040–1147). Historian Évariste Lévi-Provençal

Évariste Lévi-Provençal (4 January 1894 – 27 March 1956) was a French medievalist, orientalist, Arabist, and historian of Islam.

The scholar who would take the name Lévi-Provençal was born 4 January 1894 in Constantine, French Algeria ...

dates the beginning of teaching to the Marinid period (1244–1465).

In the 10th century, the Idrisid dynasty fell from power and Fez was contested between the Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimid dynasty, Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa ...

and Córdoban Umayyad caliphates and their allies. During this period, the Qarawiyyin Mosque progressively grew in prestige. At some point the ''khutba

''Khutbah'' (, ''khuṭbah''; , ''khotbeh''; ) serves as the primary formal occasion for public preaching in the Islamic tradition.

Such sermons occur regularly, as prescribed by the teachings of all legal schools. The Islamic tradition can be ...

'' (Friday sermon) was transferred from the Shurafa Mosque of Idris II

Idrīs ibn Idrīs () known as Idris II () and Idrīs al-Azhar/al-Aṣghar () (August 791 – August 828), was the son of Idris I of Morocco, Idris I, the founder of the Idrisid dynasty in Morocco. He was born in Volubilis, Walīlī two months aft ...

(today the Zawiya of Moulay Idris II) to the Qarawiyyin Mosque, granting it the status of Friday mosque

A congregational mosque or Friday mosque (, ''masjid jāmi‘'', or simply: , ''jāmi‘''; ), or sometimes great mosque or grand mosque (, ''jāmi‘ kabir''; ), is a mosque for hosting the Friday noon prayers known as ''jumu'ah''.See:

*

*

*

*

...

(the community's main mosque). This transfer happened either in 919 or in 933, both dates that correspond to brief periods of Fatimid domination over the city, and suggests that the transfer may have occurred by Fatimid initiative. The mosque and its learning institution continued to enjoy the respect of political elites, with the mosque itself being significantly expanded by the Almoravids and repeatedly embellished under subsequent dynasties. Tradition was established that all the other mosques in Fez based the timing of their call to prayer (''adhan

The (, ) is the Islamic call to prayer, usually recited by a muezzin, traditionally from the minaret of a mosque, shortly before each of the five obligatory daily prayers. The adhan is also the first phrase said in the ear of a newborn baby, ...

'') according to that of al-Qarawiyyin.

Apogee during the Marinid period

Many scholars consider al-Qarawiyyin's high point as an intellectual and scholarly center to be in the 13th and 14th centuries, when the curriculum was at its broadest and its prestige had reached new heights after centuries of expansion and elite patronage. Among the subjects taught around this period or shortly after were traditional religious subjects such as theQuran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

and ''fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ) is the term for Islamic jurisprudence.Fiqh

Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

'' (Islamic jurisprudence), and other sciences like Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

grammar

In linguistics, grammar is the set of rules for how a natural language is structured, as demonstrated by its speakers or writers. Grammar rules may concern the use of clauses, phrases, and words. The term may also refer to the study of such rul ...

, rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

, logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

, medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

and geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

. By contrast, some subjects like alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

/chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

were never officially taught as they were considered too unorthodox. Starting in the late 13th century, and especially in the 14th century, the Marinid dynasty was responsible for constructing a number of formal madrasas in the areas around al-Qarawiyyin's main building. The first of these was the

Starting in the late 13th century, and especially in the 14th century, the Marinid dynasty was responsible for constructing a number of formal madrasas in the areas around al-Qarawiyyin's main building. The first of these was the Saffarin Madrasa

Saffarin Madrasa () is a madrasa in Fes el Bali, Fes el-Bali, the old medina quarter of Fez, Morocco, Fez, Morocco. It was built in 1271 Common Era, CE (670 Hijri year, AH) by the Marinid Sultanate, Marinid Sultan Abu Yaqub Yusuf an-Nasr, Abu Ya' ...

in 1271, followed by al-Attarine in 1323, and the Mesbahiya Madrasa in 1346. A larger but much later madrasa, the Cherratine Madrasa

Cherratine Madrasa () is an Islamic school or madrasa that was built in 1670 by the Alawi sultan Moulay al-Rashid. It is located in the city of Fez in Morocco. The madrasa is also called Er-Rachidia Madrasa or Ras al-Cherratine Madrasa.

His ...

, was also built nearby in 1670. These madrasas taught their own courses and sometimes became well-known institutions, but they usually had narrower curricula or specializations. One of their most important functions seems to have been to provide housing for students from other towns and cities – many of them poor – who needed a place to stay while studying at al-Qarawiyyin. Thus, these buildings acted as complimentary or auxiliary institutions to al-Qarawiyyin itself, which remained the center of intellectual life in the city.

Al-Qarawiyyin also compiled a large selection of manuscripts that were kept at a library founded by the Marinid sultan Abu Inan Faris

Abu Inan Faris (1329 – 10 January 1358) () was a Marinid ruler. He succeeded his father Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Othman in 1348. He extended his rule over Tlemcen and Ifriqiya, which covered the north of what is now Algeria and Tunisia, but wa ...

in 1349. The collection housed numerous works from the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ), also known as the Arab Maghreb () and Northwest Africa, is the western part of the Arab world. The region comprises western and central North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb al ...

, al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

, and the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

. Part of the collection was gathered decades earlier by Sultan Abu Yusuf Ya'qub (ruled 1258–1286), who persuaded Sancho IV of Castile

Sancho IV of Castile (12 May 1258 – 25 April 1295) called the Brave (''el Bravo''), was the king of Castile, León and Galicia (now parts of Spain) from 1284 to his death. Following his brother Ferdinand's death, he gained the s ...

to hand over a number of works from the libraries of Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

, Córdoba Córdoba most commonly refers to:

* Córdoba, Spain, a major city in southern Spain and formerly the imperial capital of Islamic Spain

* Córdoba, Argentina, the second largest city in Argentina and the capital of Córdoba Province

Córdoba or Cord ...

, Almeria, Granada

Granada ( ; ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada (Spain), Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence ...

, and Malaga in al-Andalus/Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

. Abu Yusuf initially housed these in the nearby Saffarin Madrasa (which he had recently built), but later moved them to al-Qarawiyyin. Among the most precious manuscripts currently housed in the library are volumes from the ''Al-Muwatta

''Al-Muwaṭṭaʾ'' (, 'the approved') or ''Muwatta Imam Malik'' () of Malik ibn Anas, Imam Malik (711–795) written in the 8th-century, is one of the earliest collections of hadith texts comprising the subjects of Sharia, Islamic law, compile ...

'' of Malik

Malik (; ; ; variously Romanized ''Mallik'', ''Melik'', ''Malka'', ''Malek'', ''Maleek'', ''Malick'', ''Mallick'', ''Melekh'') is the Semitic term translating to "king", recorded in East Semitic and Arabic, and as mlk in Northwest Semitic d ...

written on gazelle parchment

Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared Tanning (leather), untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves and goats. It has been used as a writing medium in West Asia and Europe for more than two millennia. By AD 400 ...

, a copy of the '' Sirat'' by Ibn Ishaq

Abu Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Ishaq ibn Yasar al-Muttalibi (; – , known simply as Ibn Ishaq, was an 8th-century Muslim historian and hagiographer who collected oral traditions that formed the basis of an important biography of the Islamic proph ...

, a 9th-century Quran manuscript (also written on gazelle parchment), a copy of the Quran given by Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur

Ahmad al-Mansur (; 1549 – 25 August 1603), also known by the nickname al-Dhahabī () was the Saadi Sultanate, Saadi Sultan of Morocco from 1578 to his death in 1603, the sixth and most famous of all rulers of the Saadis. Ahmad al-Mansur was an ...

in 1602, a copy of Ibn Rushd

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, math ...

's ''Al-Bayan Wa-al-Tahsil wa-al-Tawjih'' (a commentary on ''Maliki'' ''fiqh'') dating from 1320, and the original copy of Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732–808 Hijri year, AH) was an Arabs, Arab Islamic scholar, historian, philosopher and sociologist. He is widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest social scientists of the Middle Ages, and cons ...

's book ''Al-'Ibar'' (including the ''Muqaddimah

The ''Muqaddimah'' ( "Introduction"), also known as the ''Muqaddimah of Ibn Khaldun'' () or ''Ibn Khaldun's Introduction (writing), Prolegomena'' (), is a book written by the historian Ibn Khaldun in 1377 which presents a view of Universal histo ...

'') gifted by the author in 1396. Recently rediscovered in the library is an ''ijazah

An ''ijazah'' (, "permission", "authorization", "license"; plural: ''ijazahs'' or ''ijazat'') is a license authorizing its holder to transmit a certain text or subject, which is issued by someone already possessing such authority. It is particul ...

'' certificate, written on deer

A deer (: deer) or true deer is a hoofed ruminant ungulate of the family Cervidae (informally the deer family). Cervidae is divided into subfamilies Cervinae (which includes, among others, muntjac, elk (wapiti), red deer, and fallow deer) ...

parchment

Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared Tanning (leather), untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves and goats. It has been used as a writing medium in West Asia and Europe for more than two millennia. By AD 400 ...

, which some scholars claim to be the oldest surviving predecessor of a Medical Doctorate degree, issued to a man called Abdellah Ben Saleh Al Koutami in 1207 CE under the authority of three other doctors and in the presence of the chief ''qadi

A qadi (; ) is the magistrate or judge of a Sharia court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and minors, and supervision and auditing of public works.

History

The term '' was in use from ...

'' (judge) of the city and two other witnesses. The library was managed by a ''qayim'' or conservator, who oversaw the maintenance of the collection. By 1613 one conservator estimated the library's collection at 32,000 volumes.

Students were male, but traditionally it has been said that "facilities were at times provided for interested women to listen to the discourse while accommodated in a special gallery (''

Students were male, but traditionally it has been said that "facilities were at times provided for interested women to listen to the discourse while accommodated in a special gallery (''riwaq Riwaq may refer to:

*Riwaq (arcade) or rivaq, an arcade in Islamic architecture

*Riwaq (organization)

Riwaq () or Centre for Architectural Conservation is a center for the preservation of architectural heritage of rural Palestine. The organizatio ...

'') overlooking the scholars' circle". The 12th-century cartographer Mohammed al-Idrisi

Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Idrisi al-Qurtubi al-Hasani as-Sabti, or simply al-Idrisi (; ; 1100–1165), was an Arab Muslim geographer and cartographer who served in the court of King Roger II at Palermo, Sicily. Muhammad al-Idrisi was born in Ce ...

, whose maps aided European exploration during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, is said to have lived in Fez for some time, suggesting that he may have worked or studied at al-Qarawiyyin. The institution has produced numerous scholars who have strongly influenced the intellectual and academic history of the Muslim world. Among them are Ibn Rushayd al-Sabti (d. 1321), Mohammed Ibn al-Hajj al-Abdari al-Fasi (d. 1336), Abu Imran al-Fasi

Abū ʿImrān Mūsā ibn ʿĪsā ibn Abī 'l-Ḥājj (or Ḥajjāj) al-Fāsī () (also simply known as Abū ʿImrān al-Fāsī; born between 975 and 978, died 8 June 1039) was a Moroccan Maliki ''faqīh'' born at Fez to a Berber or Arab family wh ...

(d. 1015) – a leading theorist of the Maliki

The Maliki school or Malikism is one of the four major madhhab, schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas () in the 8th century. In contrast to the Ahl al-Hadith and Ahl al-Ra'y schools of thought, the ...

school of Islamic jurisprudence

''Fiqh'' (; ) is the term for Islamic jurisprudence.Fiqh

Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

, and Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

Leo Africanus

Johannes Leo Africanus (born al-Ḥasan ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Wazzān al-Zayyātī al-Fasī, ; – ) was an Andalusi diplomat and author who is best known for his 1526 book '' Cosmographia et geographia de Affrica'', later publish ...

. Pioneer scholars such as Muhammad al-Idrissi (d.1166 AD), Ibn al-Arabi Ibn al-ʿArabī may refer to:

*Ibn Arabi (1165–1240), Andalusi Muslim philosopher

*Abu Bakr ibn al-Arabi

Abu Bakr ibn al-Arabi (; –1148) was a Muslim judge and scholar of Maliki law from al-Andalus. Like Al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad, Ibn al-Arabi ...

(1165–1240 AD), Ibn Khaldun (1332–1395 AD), Ibn al-Khatib

Lisan ad-Din Ibn al-Khatib (; 16 November 1313 – 1374) was an Arab Andalusi polymath, poet, writer, historian, philosopher, physician and politician from Emirate of Granada. Being one of the most notable poets from Granada, his poems decorate ...

(d. 1374), Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji

Nūr al-Dīn ibn Isḥaq al-Biṭrūjī (, died c. 1204), known in the West by the Latinized name of Alpetragius, was an Arab astronomer and qadi in al-Andalus. Al-Biṭrūjī was the first astronomer to present the concentric spheres model as an ...

(Alpetragius) (d. 1294), and Ali ibn Hirzihim (d. 1163) were all connected with al-Qarawiyyin as either students or lecturers. Some Christian scholars visited al-Qarawiyyin, including Nicolas Cleynaerts

Nicolas Cleynaerts (Clenardus or Clenard) (5 December 1495 – 1542) was a Flanders, Flemish Philologist, grammarian and traveler. He was born in Diest, in the Duchy of Brabant.

Life

Cleynaerts was a follower of Jan Driedo. Educated at the Old U ...

(d. 1542) and the Jacobus Golius

Jacob Golius, born Jacob van Gool (1596 – September 28, 1667), was an Orientalist and mathematician based at the Leiden University in the Netherlands. He is primarily remembered as an Orientalist. He published Arabic texts in Arabic at Leiden, ...

(d. 1667). The 19th-century orientalist Jousé Ponteleimon Krestovitich also claimed that Gerbert d'Aurillac (later Pope Sylvester II

Pope Sylvester II (; – 12 May 1003), originally known as Gerbert of Aurillac, was a scholar and teacher who served as the bishop of Rome and ruled the Papal States from 999 to his death. He endorsed and promoted study of Science in the medieva ...

) studied at al-Qarawiyyin in the 10th century. Although this claim about Gerbert is sometimes repeated by modern authors, modern scholarship has not produced evidence to support this story.

Decline and reforms

Al-Qarawiyyin underwent a general decline in later centuries along with Fez. The strength of its teaching stagnated and its curriculum decreased in range and scope, becoming focused on traditionalIslamic sciences

The Islamic sciences () are a set of traditionally defined religious sciences practiced by Islamic scholars ( ), aimed at the construction and interpretation of Islamic religious knowledge.

Different sciences

These sciences include:

* : Islami ...

and Arabic linguistic studies. Even some traditional Islamic specializations like ''tafsir

Tafsir ( ; ) refers to an exegesis, or commentary, of the Quran. An author of a ''tafsir'' is a ' (; plural: ). A Quranic ''tafsir'' attempts to provide elucidation, explanation, interpretation, context or commentary for clear understanding ...

'' (Quranic exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Ancient Greek, Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation (philosophy), interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Bible, Biblical works. In modern us ...

) were progressively neglected or abandoned. In 1788–89, the 'Alawi sultan Muhammad ibn Abdallah introduced reforms that regulated the institution's program, but also imposed stricter limits and excluded logic, philosophy, and the more radical Sufi

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

texts from the curriculum. Other subjects also disappeared over time, such as astronomy and medicine. In 1845 Sultan Abd al-Rahman

Abdelrahman or Abd al-Rahman or Abdul Rahman or Abdurrahman or Abdrrahman ( or occasionally ; DMG ''ʿAbd ar-Raḥman'') is a male Arabic Muslim given name, and in modern usage, surname. It is built from the Arabic words '' Abd'', ''al-'' and '' ...

carried out further reforms, but it is unclear if this had any significant long-term effects. Between 1830 and 1906 the number of faculty decreased from 425 to 266 (of which, among the latter, only 101 were still teaching).

By the 19th century, the mosque's library also suffered from decline and neglect. A significant portion of its collection was lost over time, most likely due to lax supervision and to books that were not returned. By the beginning of the 20th century, the collection had been reduced to around 1,600 manuscripts and 400 printed books, though many valuable historic items were retained.

By the late 19th century, Western scholars began to recognize al-Qarawiyyin as a "university", a description which would become more established during the French protectorate period in the 20th century.

20th century and transformation into state university

At the time Morocco became a French protectorate in 1912, al-Qarawiyyin worsened as a religious center of learning from its medieval prime,Lulat, Y. G.-M.: ''A History Of African Higher Education From Antiquity To The Present: A Critical Synthesis'', Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005, , pp. 154–157 though it retained some significance as an educational venue for the sultan's administration. The student body was rigidly divided along social strata: ethnicity (Arab orBerber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

), social status, personal wealth, and geographic background (rural or urban) determined the group membership of the students who were segregated by the teaching facility, as well as in their personal quarters.

The French administration implemented a number of structural reforms between 1914 and 1947, including the institution of calendars, appointment of teachers, salaries, schedules, general administration, and the replacement of the ''ijazah'' with the ''shahada alamiyha,'' but did not modernize the contents of teaching likewise which were still dominated by the traditional worldviews of the ''ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' ( ; also spelled ''ulema''; ; singular ; feminine singular , plural ) are scholars of Islamic doctrine and law. They are considered the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious knowledge in Islam.

"Ulama ...

''. At the same time, the student numbers at al-Qarawiyyin decreased to 300 in 1922 as the Moroccan elite sent their children to the newly founded Western-style colleges and institutes elsewhere in the country. Moroccan and French authorities began planning further reforms for al-Qarawiyyin in 1929. In 1931 and 1933, on the orders of Muhammad V, the institution's teaching was reorganized into elementary, secondary, and higher education.

Al-Qarawiyyin also played a role in the Moroccan nationalist movement and in protests against the French colonial regime. Many Moroccan nationalists had received their education here and some of their informal political networks were established due to the shared educational background. In July 1930, al-Qarawiyyin strongly participated in the propagation of ''Ya Latif'', a communal prayer recited in times of calamity, to raise awareness and opposition to the Berber Dahir The Berber Dahir (, , formally: ) is a ''dhahir'' (decree) that was created by the French protectorate in Morocco on May 16, 193The document changed the legal system in the parts of Morocco in which Berber languages were primarily spoken, and the ...

decreed by the French authorities two months earlier. In 1937 the mosque was one of the rallying points (along with the nearby R'cif mosque

The R'cif Mosque (; also transliterated as ''R'sif'', ''Ercif'', ''er-Rsif'', or ''Rasif'') is a Friday mosque in Fes el-Bali, the old city (medina) of Fez, Morocco. It has one of the tallest minarets in the city and overlooks Place R'cif in th ...

) for demonstrations in response to a violent crackdown on Moroccan protesters in Meknes

Meknes (, ) is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco, located in northern central Morocco and the sixth largest city by population in the kingdom. Founded in the 11th century by the Almoravid dynasty, Almoravids as a military settlement, Mekne ...

, which ended with French troops being deployed across Fes el-Bali

Fes el Bali () is the oldest part of Fez, Morocco. It is one of the three main districts of Fez, along with Fes Jdid and the French-created ''Ville Nouvelle (New City'). Together with Fes Jdid, it forms the medina (historic quarter) of Fez, signif ...

and at the mosques. In 1947, al-Qarawiyyin was integrated into the state educational system, and women were first admitted to study there during the 1940s. In 1963, after Moroccan independence, al-Qarawiyyin was officially transformed by

In 1947, al-Qarawiyyin was integrated into the state educational system, and women were first admitted to study there during the 1940s. In 1963, after Moroccan independence, al-Qarawiyyin was officially transformed by royal decree

A decree is a legal proclamation, usually issued by a head of state, judge, royal figure, or other relevant authorities, according to certain procedures. These procedures are usually defined by the constitution, Legislative laws, or customary l ...

into a university under the supervision of the ministry of education.Belhachmi, Zakia: "Gender, Education, and Feminist Knowledge in al-Maghrib (North Africa) – 1950–70", ''Journal of Middle Eastern and North African Intellectual and Cultural Studies, Vol. 2–3'', 2003, pp. 55–82 (65): Park, Thomas K.; Boum, Aomar: ''Historical Dictionary of Morocco'', 2nd ed., Scarecrow Press, 2006, , p. 348 Classes at the old mosque ceased and a new campus was established at a former French Army barracks. While the dean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

* Dean Sw ...

took his seat at Fez, four faculties

Faculty or faculties may refer to:

Academia

* Faculty (academic staff), professors, researchers, and teachers of a given university or college (North American usage)

* Faculty (division), a large department of a university by field of study (us ...

were founded in and outside the city: a faculty of Islamic law

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on scriptures of Islam, particularly the Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' refers to immutable, intan ...

in Fez, a faculty of Arab studies in Marrakech

Marrakesh or Marrakech (; , ) is the fourth-largest city in Morocco. It is one of the four imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakesh–Safi Regions of Morocco, region. The city lies west of the foothills of the Atlas Mounta ...

, and two faculties of theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

in Tétouan

Tétouan (, or ) is a city in northern Morocco. It lies along the Martil Valley and is one of the two major ports of Morocco on the Mediterranean Sea, a few miles south of the Strait of Gibraltar, and about E.S.E. of Tangier. In the 2014 Morocc ...

and near Agadir

Agadir (, ; ) is a major List of cities in Morocco, city in Morocco, on the shore of the Atlantic Ocean near the foot of the Atlas Mountains, just north of the point where the Sous River, Souss River flows into the ocean, and south of Casabla ...

. Modern curricula and textbooks were introduced and the professional training of the teachers improved.Park, Thomas K.; Boum, Aomar: ''Historical Dictionary of Morocco'', 2nd ed., Scarecrow Press, 2006, , p. 348 Following the reforms, al-Qarawiyyin was officially renamed "University of Al Quaraouiyine" in 1965.

In 1975, General Studies was transferred to the newly founded Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University

Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University (; ) is a university in Fez city, Morocco, which was founded in 1975. It is named for Mohammed ben Abdallah.

In 2022, the ''Times Higher Education World University Rankings'' rated Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah ...

; al-Qarawiyyin kept the Islamic and theological courses of studies. In 1973, Abdelhadi Tazi

Abdelhadi Tazi (June 15, 1921 – April 2, 2015) was a scholar, writer, historian and former Moroccan ambassador in various countries.

Early life

Tazi was born in Fes, Morocco, and attended primary and secondary studies in his hometown. Si ...

published a three-volume history of the establishment entitled (''The al-Qarawiyyin Mosque'').

In 1988, after a hiatus of almost three decades, the teaching of traditional Islamic education at al-Qarawiyyin was resumed by King Hassan II

Hassan, Hasan, Hassane, Haasana, Hassaan, Asan, Hassun, Hasun, Hassen, Hasson or Hasani may refer to:

People

*Hassan (given name), Arabic given name and a list of people with that given name

*Hassan (surname), Arabic, Jewish, Irish, and Scotti ...

in what has been interpreted as a move to bolster conservative support for the monarchy.

Education and curriculum

Education at al-Qarawiyyin University concentrates on the Islamic religious and legal sciences with a heavy emphasis on, and particular strengths in,Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic or Quranic Arabic () is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notably in Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphate, Abbasid literary texts such as poetry, e ...

grammar/linguistics and Maliki

The Maliki school or Malikism is one of the four major madhhab, schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas () in the 8th century. In contrast to the Ahl al-Hadith and Ahl al-Ra'y schools of thought, the ...

law, though some lessons on other non-Islamic subjects such as French and English are also offered to students. Teaching is delivered with students seated in a semi-circle around a sheikh, who prompts them to read sections of a particular text; asks them questions on particular points of grammar, law, or interpretation; and explains difficult points. Students from Morocco and Islamic West Africa attend al-Qarawiyyin, though some come from Muslim Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

. Spanish Muslim converts frequently attend the institution, largely attracted by the fact that the sheikhs of al-Qarawiyyin, and Islamic scholarship in Morocco in general, are heirs to the rich, religious, and scholarly heritage of Muslim al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

.

Most students at al-Qarawiyyin range are between 13 and 30 years old, and study towards high school-level diplomas and university-level bachelor's degrees, although Muslims with a sufficiently high level of Arabic can attend lecture circles on an informal basis, given the traditional category of visitors "in search of eligious and legalknowledge". In addition to being Muslim, prospective students of al-Qarawiyyin are required to have fully memorized the Quran, as well as other shorter medieval Islamic texts on grammar and ''Maliki'' law, and to be proficient in classical Arabic.

Architecture of the mosque

Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque was founded in the 9th century, but its present form is the result of a long historical evolution over the course of more than 1,000 years. Successive dynasties expanded the mosque until it became the largest in

Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque was founded in the 9th century, but its present form is the result of a long historical evolution over the course of more than 1,000 years. Successive dynasties expanded the mosque until it became the largest in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, with a capacity of 22,000 worshipers. The present-day mosque covers an extensive area of about half a hectare

The hectare (; SI symbol: ha) is a non-SI metric unit of area equal to a square with 100-metre sides (1 hm2), that is, square metres (), and is primarily used in the measurement of land. There are 100 hectares in one square kilometre. ...

. Broadly speaking, it consists of a large hypostyle

In architecture, a hypostyle () hall has a roof which is supported by columns.

Etymology

The term ''hypostyle'' comes from the ancient Greek ὑπόστυλος ''hypóstȳlos'' meaning "under columns" (where ὑπό ''hypó'' means below or und ...

interior space for prayers (the prayer hall), a courtyard with fountains (the ''sahn

A ''sahn'' (, '), is a courtyard in Islamic architecture, especially the formal courtyard of a mosque. Most traditional mosques have a large central ''sahn'', which is surrounded by a ''Riwaq (arcade), riwaq'' or arcade (architecture), arcade on ...

''), a minaret

A minaret is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generally used to project the Muslim call to prayer (''adhan'') from a muezzin, but they also served as landmarks and symbols of Islam's presence. They can h ...

at the courtyard's western end, and a number of annexes around the mosque itself.

Historical evolution

Early history (9th–10th centuries)

The original mosque building was built in the 9th century. A major modern study of the mosque's structure, published by French archeologist and historianHenri Terrasse

Henri Terrasse (Vrigny-aux-Bois, 8 August 1895 – Grenoble, 11 October 1971) was a French historian, archeologist, and orientalist who specialized in the art and history of the Islamic world and of Morocco in particular.

Biography

Terrasse wa ...

in 1968, determined that traces of the original mosque could be found in the layout of the current building. This initial form of the mosque occupied a large space immediately to the south of the ''sahn'', in what is now the prayer hall. It had a rectangular floor plan measuring 36 by 32 meters, covering an area of 1520 square meter

The square metre ( international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures) or square meter (American spelling) is the unit of area in the International System of Units (SI) with symbol m2. It is the area of a square w ...

s, and was composed of a prayer hall with four transverse aisles running roughly east–west, parallel to the southern ''qibla

The qibla () is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Great Mosque of Mecca, Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the salah. In Islam, the Kaaba is believed to ...

'' wall. It probably also had a courtyard of relatively small size, and the first minaret, also of small size, reportedly stood on the location now occupied by the wooden ''anaza

Anaza'' or ''anaza'' (; sometimes also transliterated as anza'' or ''anza'') is a short spear or staff that held ritual importance in the early period of Islam. The term gained significance after the Islamic prophet Muhammad planted his spe ...

'' (at the central entrance to the prayer hall from the courtyard). Water for the mosque was initially provided by a well dug within the mosque's precinct.

As Fez grew and the mosque increased in prestige, the original building was insufficient for its religious and institutional needs. During the 10th century, the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba and the Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa and West Asia, i ...

constantly fought for control over Fez and Morocco, seen as a buffer zone between the two. Despite this uncertain period, the mosque received significant patronage and had its first expansions. The Zenata

The Zenata (; ) are a group of Berber tribes, historically one of the largest Berber confederations along with the Sanhaja and Masmuda. Their lifestyle was either nomadic or semi-nomadic.

Society

The 14th-century historiographer Ibn Khaldun repo ...

Berber emir

Emir (; ' (), also Romanization of Arabic, transliterated as amir, is a word of Arabic language, Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocratic, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person po ...

Ahmed ibn Abi Said, one of the rulers of Fez during this period who was aligned with the Umayyads, wrote to the caliph Abd al-Rahman III

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ḥakam al-Rabdī ibn Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil (; 890–961), or simply ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III, was the Umayyad Emir of Córdoba fr ...

in Córdoba for permission and funds to expand the mosque. The caliph approved, and the work was carried out or completed in 956. It expanded the mosque on three sides, encompassing the area of the present-day courtyard to the north and up to the current eastern and western boundaries of the building. It also replaced the original minaret with a new, larger minaret still standing today. Its overall form, with a square shaft, was indicative of the subsequent development of Maghrebi and Andalusian minarets.

The mosque was embellished when the Amirid ruler al-Muzaffar (son of al-Mansur

Abū Jaʿfar ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad al-Manṣūr (; ; 714 – 6 October 775) usually known simply as by his laqab al-Manṣūr () was the second Abbasid caliph, reigning from 754 to 775 succeeding his brother al-Saffah (). He is known ...

) led a military expedition to Fez in 998. The embellishments included a new ''minbar

A minbar (; sometimes romanized as ''mimber'') is a pulpit in a mosque where the imam (leader of prayers) stands to deliver sermons (, ''khutbah''). It is also used in other similar contexts, such as in a Hussainiya where the speaker sits and le ...

'' and a dome topped by talismans in the shape of a rat, a serpent, and a scorpion. Of these, only the dome itself, whose exterior is distinctively fluted

Fluting may refer to:

*Fluting (architecture)

*Fluting (firearms)

*Fluting (geology)

* Fluting (glacial)

*Fluting (paper)

*Playing a flute (musical instrument)

Arts, entertainment, and media

*Fluting on the Hump

''Fluting on the Hump'' is the ...

or grooved, survives today, located above the courtyard entrance to the prayer hall. A similar dome, located across the courtyard over the northern entrance of the mosque (''Bab al-Ward'' or "Gate of the Rose"), likely also dates from the same time.

Almoravid expansion (12th century)

One of the most significant expansions and renovations was carried out between 1134 and 1143 under the patronage of the Almoravid rulerAli ibn Yusuf

Ali ibn Yusuf (also known as "Ali Ben Youssef") () (c. 1084 – 28 January 1143) was the 5th Almoravid emir. He reigned from 1106 to 1143.

Early life

Ali ibn Yusuf was born in 1084–1085 (477 AH) in Ceuta. He was the son of Yusuf ibn Tashf ...

. The prayer hall was extended by dismantling the existing southern wall and adding three more transverse aisles for a total of ten, while replicating the format of the existing arches of the mosque. This expansion required the purchase and demolition of a number of neighboring houses and structures, including some that were apparently part of the nearby Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

neighbourhood (before the Mellah of Fez

The Mellah of Fez () is the historic Jewish quarter (''Mellah'') of Fez, Morocco. It is located in Fes el-Jdid, the part of Fez which contains the Royal Palace (Dar al-Makhzen), and is believed to date from the mid-15th century. While the distr ...

).

The new expansion of the mosque involved not only a new ''mihrab'' in the middle of the new southern wall, but also the reconstruction or embellishment of the prayer hall's central nave (the arches along its central axis, in a line perpendicular to the southern wall and to the other rows of arches) leading from the courtyard to the ''mihrab''. This involved not only embellishing some of the arches with new forms but also adding a series of highly elaborate cupola ceilings composed in ''

The new expansion of the mosque involved not only a new ''mihrab'' in the middle of the new southern wall, but also the reconstruction or embellishment of the prayer hall's central nave (the arches along its central axis, in a line perpendicular to the southern wall and to the other rows of arches) leading from the courtyard to the ''mihrab''. This involved not only embellishing some of the arches with new forms but also adding a series of highly elaborate cupola ceilings composed in ''muqarnas

Muqarnas (), also known in Iberian architecture as Mocárabe (from ), is a form of three-dimensional decoration in Islamic architecture in which rows or tiers of niche-like elements are projected over others below. It is an archetypal form of I ...

'' (honeycomb or stalactite-like) sculpting and further decorated with intricate relief

Relief is a sculpture, sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''wikt:relief, relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give ...

s of arabesque

The arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "surface decorations based on rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines, often combined with other elements. Another definition is "Foliate ...

s and Kufic

The Kufic script () is a style of Arabic script, that gained prominence early on as a preferred script for Quran transcription and architectural decoration, and it has since become a reference and an archetype for a number of other Arabic scripts ...

letters. The craftsmen who worked on this expansion are mostly anonymous, except for two names that are carved on the bases of two of the cupolas: Ibrāhīm and Salāma ibn Mufarrij, who may have been of Andalusi origin. Lastly, a new ''minbar'' in similar style and of similar artistic provenance as the ''minbar'' of the Koutoubia Mosque was completed and installed in 1144. It is made of wood in an elaborate work of marquetry

Marquetry (also spelled as marqueterie; from the French ''marqueter'', to variegate) is the art and craft of applying pieces of wood veneer, veneer to a structure to form decorative patterns or designs. The technique may be applied to case furn ...

, and decorated with inlaid materials and intricately carved arabesque reliefs. Its style was emulated for later Moroccan minbars.

Elsewhere, many of the mosque's main entrances were given doors made of wood overlaid with ornate bronze fittings, which today count among the oldest surviving bronze artworks in Moroccan architecture

Moroccan architecture reflects Morocco's diverse geography and long history, marked by successive waves of settlers through both migration and military conquest. This architectural heritage includes ancient Roman sites, historic Islamic architec ...

. Another interesting element added to the mosque was a small secondary oratory, known as the ''Jama' al-Gnaiz'' ("Funeral Mosque" or "Mosque of the Dead"), which was separated from the main prayer hall and dedicated to providing funerary rites

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect t ...

for the deceased before their burial. The annex is also decorated with a ''muqarnas'' cupola and ornate archways and windows.

Almohad period (12th–13th centuries)

Later dynasties continued to embellish the mosque or gift it with new furnishings, though no works as radical as the Almoravid expansion were undertaken again. TheAlmohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; or or from ) or Almohad Empire was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) and North Africa (the Maghreb).

The Almohad ...

(later 12th century and 13th century) conquered Fez after a long siege in 1145–1146. Historical sources (particularly the ''Rawd al-Qirtas

''Rawḍ al-Qirṭās'' () short for ''Kitāb al-ānīs al-muṭrib bi-rawḍ al-qirṭās fī ākhbār mulūk al-maghrab wa tārīkh madīnah Fās'' ('', The Entertaining Companion Book in the Gardens of Pages from the Chronicle of the Kings of ...

'') report a story claiming that the inhabitants of Fez, fearful that the "puritan" Almohads would resent the lavish decoration placed inside the mosque, used whitewash to cover up the most ornate decorations from Ibn Yusuf's expansion near the ''mihrab.'' Terrasse suggests this operation may have actually been carried out a few years later by the Almohad authorities themselves. The Almoravid ornamentation was only fully uncovered again during renovations in the early 20th century. The plaster used to cover the Almoravid decoration seems to have been prepared too quickly and did not fully bond with the existing surface. This ended up making its removal easier during modern restorations and has helped to preserve much of the original Almoravid decoration now visible again today.

Under the reign of Muhammad al-Nasir

Muhammad al-Nasir (,'' Muḥammad an-Nāṣir'', – 1213) was the fourth Almohad Caliph from 1199 until his death. Évariste Lévi-Provençalal-Nāṣir Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill Online, 2013. Reference. 9 January 2013. Co ...

(r. 1199–1213), the Almohads added and upgraded a number of elements in the mosque, some of which were nonetheless marked with strong decorative flourishes. The ablutions facilities in the courtyard were upgraded, a separate ablutions room was added to the north, and a new underground storage room was created. They also replaced the mosque's grand chandelier with one made of bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

, which Terrasse described as "the largest and most beautiful chandelier in the Islamic world," and which hangs in the central nave of the mosque today. It was commissioned by Abu Muhammad 'Abd Allah ibn Musa, the ''khatib

In Islam, a khatib or khateeb ( ''khaṭīb'') is a person who delivers the sermon (''khuṭbah'') (literally "narration"), during the Friday prayer and Eid prayers.

The ''khateeb'' is usually the prayer leader (''imam''), but the two roles can ...

'' of the mosque during the years 1202 to 1219. The chandelier has the shape of a 12-sided cupola surmounted by a large cone, around which are nine levels that hold candlesticks. It could originally hold 520 oil candles; the cost of providing the oil was so significant that it was only lit on special occasions, such as on the nights of Ramadan

Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar. It is observed by Muslims worldwide as a month of fasting (''Fasting in Islam, sawm''), communal prayer (salah), reflection, and community. It is also the month in which the Quran is believed ...

. The Marinid sultan Abu Ya'qub Yusuf (r. 1286–1307), upon seeing the cost, ordered that it only be lit for the last day of Ramadan. The visible surfaces of the chandelier are carved and pierced with intricate floral arabesque motifs as well as Kufic Arabic inscriptions. The chandelier is the oldest surviving chandelier in the western Islamic world, and it likely served as a model for the Marinid chandelier in the Great Mosque of Taza

The Great Mosque of Taza () is the most important religious building in the historic medina of Taza, Morocco. Founded in the 12th century by the Almohad caliph Abd al-Mu'min, it is the oldest surviving example of Almohad architecture. It was ex ...

.

Marinid period (13th–14th centuries)

The Marinids, who were responsible for building many of the madrasas around Fez, made various contributions to the mosque. In 1286 they restored and protected the 10th-century minaret, which had been made from deteriorating poor-quality stone withwhitewash

Whitewash, calcimine, kalsomine, calsomine, asbestis or lime paint is a type of paint made from slaked lime ( calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)2) or chalk (calcium carbonate, CaCO3), sometimes known as "whiting". Various other additives are sometimes ...

. At its southern foot, they also built the ''Dar al-Muwaqqit

A Dar al-Muwaqqit (), or muvakkithane in Turkish, is a room or structure accompanying a mosque which was used by the ''muwaqqit'' or timekeeper, an officer charged with maintaining the correct times of prayer and communicating them to the muezzin ...

'', a chamber for the timekeeper (''muwaqqit

In the history of Islam, a ''muwaqqit'' (, more rarely ''mīqātī''; ) was an astronomer tasked with the timekeeping and the regulation of prayer times in an Islamic institution like a mosque or a madrasa. Unlike the muezzin (reciter of the ...

'') of the mosque who was responsible for determining the precise times of prayer. The chamber was equipped with astrolabe

An astrolabe (; ; ) is an astronomy, astronomical list of astronomical instruments, instrument dating to ancient times. It serves as a star chart and Model#Physical model, physical model of the visible celestial sphere, half-dome of the sky. It ...

s and other scientific equipment of the era in order to aid in this task. Several water clock

A water clock, or clepsydra (; ; ), is a timepiece by which time is measured by the regulated flow of liquid into (inflow type) or out from (outflow type) a vessel, and where the amount of liquid can then be measured.

Water clocks are some of ...

s were built for it in this period. The first two do not exist anymore, but are described by al-Jazna'i in the ''Zahrat al-As''. The first was commissioned by Abu Yusuf Ya'qub in the 13th century and designed by Muhammad ibn al-Habbak, a '' faqih'' and ''muwaqqit''. The second was built in 1317 or 1318 (717 AH), under the reign of Abu Sa'id

Abu or ABU may refer to:

Aviation

* Airman Battle Uniform, a utility uniform of the United States Air Force

* IATA airport code for A. A. Bere Tallo Airport in Atambua, Province of East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia

People

* Abu (Arabic term), a kun ...