Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

from 1933 until

his suicide in 1945.

He rose to power as the leader of the

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

, becoming

the chancellor in 1933 and then taking the title of in 1934. His

invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

on 1 September 1939 marked the start of the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. He was closely involved in military operations throughout the war and was central to the perpetration of

the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

: the

genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

of

about six million Jews and millions of other victims.

Hitler was born in

Braunau am Inn in

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

and moved to

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

in 1913. He was decorated during his service in the German Army in the

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, receiving the

Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, the German Empire (1871–1918), and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). The design, a black cross pattée with a white or silver outline, was derived from the in ...

. In 1919 he joined the

German Workers' Party

The German Workers' Party (, DAP) was a short-lived far-right political party established in the Weimar Republic after World War I. It only lasted from 5 January 1919 until 24 February 1920. The DAP was the precursor of the National Socialist ...

(DAP), the precursor of the Nazi Party, and in 1921 was appointed the leader of the Nazi Party. In 1923 he attempted to seize governmental power in

a failed coup in Munich and was sentenced to five years in prison, serving just over a year. While there, he dictated the first volume of his autobiography and political manifesto ''

Mein Kampf

(; ) is a 1925 Autobiography, autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The book outlines many of Political views of Adolf Hitler, Hitler's political beliefs, his political ideology and future plans for Nazi Germany, Ge ...

'' (). After his early release in 1924, he gained popular support by attacking the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

and promoting

pan-Germanism

Pan-Germanism ( or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanism seeks to unify all ethnic Germans, German-speaking people, and possibly also non-German Germanic peoples – into a sin ...

,

antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

, and

anti-communism

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism, communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global ...

with

charismatic

Charisma () is a personal quality of magnetic charm, persuasion, or appeal.

In the fields of sociology and political science, psychology, and management, the term ''charismatic'' describes a type of leadership.

In Christian theology, the term ...

oratory and

Nazi propaganda

Propaganda was a tool of the Nazi Party in Germany from its earliest days to the end of the regime in May 1945 at the end of World War II. As the party gained power, the scope and efficacy of its propaganda grew and permeated an increasing amou ...

. He frequently denounced

communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

as being part of an

international Jewish conspiracy

The international Jewish conspiracy or the world Jewish conspiracy is an antisemitic trope that has been described as "one of the most widespread and long-running conspiracy theories". Although it typically claims that a malevolent, usually gl ...

. By November 1932 the Nazi Party held the most seats in the ''

Reichstag'', but not a majority. Former chancellor

Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and army officer. A national conservative, he served as Chancellor of Germany in 1932, and then as Vice-Chancell ...

and other conservative leaders convinced President

Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military and political leader who led the Imperial German Army during the First World War and later became President of Germany (1919� ...

to appoint Hitler as chancellor on 30 January 1933. Shortly thereafter, the ''Reichstag'' passed the

Enabling Act of 1933

The Enabling Act of 1933 ( German: ', officially titled ' ), was a law that gave the German Cabinet—most importantly, the chancellor, Adolf Hitler—the power to make and enforce laws without the involvement of the Reichstag or President Pa ...

, which began the process of transforming the

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

into Nazi Germany, a

one-party dictatorship based upon the

totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public sph ...

,

autocratic

Autocracy is a form of government in which absolute power is held by the head of state and Head of government, government, known as an autocrat. It includes some forms of monarchy and all forms of dictatorship, while it is contrasted with demo ...

, and

fascistic ideology of

Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

.

Upon Hindenburg's death on 2 August 1934, Hitler became simultaneously the head of state and government, with absolute power. Domestically, Hitler implemented numerous

racist policies and sought to deport or kill

German Jews

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321 CE, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (c. 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish commu ...

. His first six years in power resulted in rapid economic recovery from the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, the abrogation of restrictions imposed on Germany after the First World War, and the

annexation

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held t ...

of territories inhabited by millions of ethnic Germans, which initially gave him significant popular support. One of Hitler's key goals was () for the German people in Eastern Europe, and his aggressive,

expansionist

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who ...

foreign policy is considered the primary

cause of World War II in Europe. He directed large-scale rearmament and, on 1 September 1939, invaded Poland, causing Britain and

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

to

declare war on Germany. In June 1941 Hitler ordered

an invasion of the Soviet Union. In December 1941 he

declared war on the United States. By the end of 1941 German forces and the European

Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

occupied most of Europe and

North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

. These gains were gradually reversed after 1941, and in 1945 the

Allied armies defeated the German army. On 29 April 1945 he married his longtime partner,

Eva Braun, in the in Berlin. The couple committed suicide the next day to avoid capture by the Soviet

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

.

The historian and biographer

Ian Kershaw

Sir Ian Kershaw (born 29 April 1943) is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's foremost experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is ...

described Hitler as "the embodiment of modern political evil". Under Hitler's leadership and

racist ideology, the Nazi regime was responsible for the genocide of an estimated six million Jews and millions of other victims, whom he and his followers deemed () or socially undesirable. Hitler and the Nazi regime were also responsible for the deliberate killing of an estimated 19.3 million civilians and prisoners of war. In addition, 28.7 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of military action in the European

theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors to present experiences of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a Stage (theatre), stage. The performe ...

. The number of

civilians killed during World War II was unprecedented in warfare, and the casualties constitute the

deadliest conflict in history.

Ancestry

Hitler's father,

Alois Hitler, was the

illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce.

Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as ''b ...

child of

Maria Schicklgruber. The baptismal register did not show the name of his father, and Alois initially bore his mother's surname, "Schicklgruber". In 1842,

Johann Georg Hiedler married Alois's mother. Alois was brought up in the family of Hiedler's brother,

Johann Nepomuk Hiedler. Alois worked as a civil servant from 1855 until his retirement in 1895. In 1876, Alois was made legitimate and his baptismal record annotated by a priest to register Johann Georg Hiedler as Alois's father (recorded as "Georg Hitler"). Alois then assumed the surname "Hitler", also spelled , or . The name is probably based on the German word (), and has the meaning "one who lives in a hut".

The Nazi official

Hans Frank suggested that Alois's mother had been employed as a housekeeper by a Jewish family in

Graz

Graz () is the capital of the Austrian Federal states of Austria, federal state of Styria and the List of cities and towns in Austria, second-largest city in Austria, after Vienna. On 1 January 2025, Graz had a population of 306,068 (343,461 inc ...

, and that the family's 19-year-old son Leopold Frankenberger had fathered Alois, a claim that came to be known as the

Frankenberger thesis. No Frankenberger was registered in Graz during that period, and no record has been produced of a Leopold Frankenberger's existence, so historians dismiss the claim that Alois's father was Jewish.

Early life

Childhood and education

Adolf Hitler was born on 20 April 1889 in

Braunau am Inn, a town in

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

(present-day Austria), close to the border with the

German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

. He was the fourth of six children born to Alois Hitler and his third wife,

Klara Pölzl

Klara Hitler ( Pölzl; 12 August 1860 – 21 December 1907) was the mother of Adolf Hitler, dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. In 1934, Adolf Hitler honored his mother by naming a street in Passau after her.

Family background and marri ...

. Three of Hitler's siblings—Gustav, Ida, and Otto—died in infancy. Also living in the household were Alois's children from his second marriage: Alois Jr. (born 1882) and

Angela (born 1883). In 1892, the family moved to

Passau

Passau (; ) is a city in Lower Bavaria, Germany. It is also known as the ("City of Three Rivers"), as the river Danube is joined by the Inn (river), Inn from the south and the Ilz from the north.

Passau's population is about 50,000, of whom ...

, Germany, following Alois's promotion to the custom administration in Passau. Hitler was three at the time. Alois was promoted and transferred to

Linz

Linz (Pronunciation: , ; ) is the capital of Upper Austria and List of cities and towns in Austria, third-largest city in Austria. Located on the river Danube, the city is in the far north of Austria, south of the border with the Czech Repub ...

, Austria, on 1 April 1893, but the rest of the family remained in Passau. There Hitler acquired the distinctive

lower Bavarian dialect, rather than

Austrian German

Austrian German (), Austrian Standard German (ASG), Standard Austrian German (), Austrian High German (), or simply just Austrian (), is the variety of Standard German written and spoken in Austria and South Tyrol. It has the highest prestige ( ...

, which marked his speech throughout his life. The family returned to Austria and settled in

Leonding

Leonding () is a town southwest of Linz in the States of Austria, Austrian state of Upper Austria. It borders Puchenau and the river Danube in the north, Wilhering and Pasching in the west, Traun in the south and Linz in the east. Leonding is the ...

on 9 May 1894, and in June 1895 Alois retired to Hafeld, near

Lambach, where he farmed and kept bees. Hitler attended (a state-funded primary school) in nearby

Fischlham.

The move to Hafeld coincided with the onset of intense father–son conflicts caused by Hitler's refusal to conform to the strict discipline of his school. Alois tried to browbeat his son into obedience, while Adolf did his best to be the opposite of whatever his father wanted. Alois would also beat his son, although his mother tried to protect him from regular beatings.

Alois Hitler's farming efforts at Hafeld were unsuccessful, and in 1897 the family moved to Lambach. The eight-year-old Hitler took singing lessons, sang in the church choir, and even considered becoming a priest. In 1898, the family returned permanently to Leonding. Hitler was deeply affected by the death of his younger brother Edmund in 1900 from

measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

. Hitler changed from a confident, outgoing, conscientious student to a morose, detached boy who constantly fought with his father and teachers.

Paula Hitler recalled that Adolf was a teenage bully who would often slap her.

Alois had made a successful career in the customs bureau and wanted his son to follow in his footsteps. Hitler later dramatised an episode from this period when his father took him to visit a customs office, depicting it as an event that gave rise to an unforgiving antagonism between father and son, who were both strong-willed. Ignoring his son's desire to attend a classical high school and become an artist, Alois sent Hitler to the ''

Realschule

Real school (, ) is a type of secondary school in Germany, Switzerland and Liechtenstein. It has also existed in Croatia (''realna gimnazija''), the Austrian Empire, the German Empire, Denmark and Norway (''realskole''), Sweden (''realskola''), F ...

'' in Linz in September 1900. Hitler rebelled against this decision, and in states that he intentionally performed poorly in school, hoping that once his father saw "what little progress I was making at the technical school he would let me devote myself to my dream".

Like many Austrian Germans, Hitler began to develop

German nationalist

German nationalism () is an ideological notion that promotes the unity of Germans and of the Germanosphere into one unified nation-state. German nationalism also emphasizes and takes pride in the patriotism and national identity of Germans a ...

ideas from a young age. He expressed loyalty only to Germany, despising the declining

Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

and its rule over an ethnically diverse empire. Hitler and his friends used the greeting "Heil", and sang the "

Deutschlandlied

The "", officially titled "", is a German poem written by August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben . A popular song which was made for the cause of creating a unified German state, it was adopted in its entirety in 1922 by the Weimar Repub ...

" instead of the

Austrian Imperial anthem. After Alois's sudden death on 3 January 1903, Hitler's performance at school deteriorated and his mother allowed him to leave. He enrolled at the ''Realschule'' in

Steyr

Steyr (; ) is a statutory city (Austria), statutory city, located in the Austrian federal state of Upper Austria. It is the administrative capital, though not part of Steyr-Land District. Steyr is Austria's 12th most populated town and the 3rd lar ...

in September 1904, where his behaviour and performance improved. In 1905, after passing a repeat of the final exam, Hitler left the school without any ambitions for further education or clear plans for a career.

Early adulthood in Vienna and Munich

In 1907, Hitler left Linz to live and study fine art in

Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, financed by orphan's benefits and support from his mother. He applied for admission to the

Academy of Fine Arts Vienna but was rejected twice. The

director

Director may refer to:

Literature

* ''Director'' (magazine), a British magazine

* ''The Director'' (novel), a 1971 novel by Henry Denker

* ''The Director'' (play), a 2000 play by Nancy Hasty

Music

* Director (band), an Irish rock band

* ''D ...

suggested Hitler should apply to the School of Architecture, but he lacked the necessary academic credentials because he had not finished secondary school.

On 21 December 1907, his mother died of breast cancer at the age of 47; Hitler was 18 at the time. In 1909, Hitler ran out of money and was forced to live a

bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, originally practised by 19th–20th century European and American artists and writers.

* Bohemian style, a ...

life in homeless shelters and the

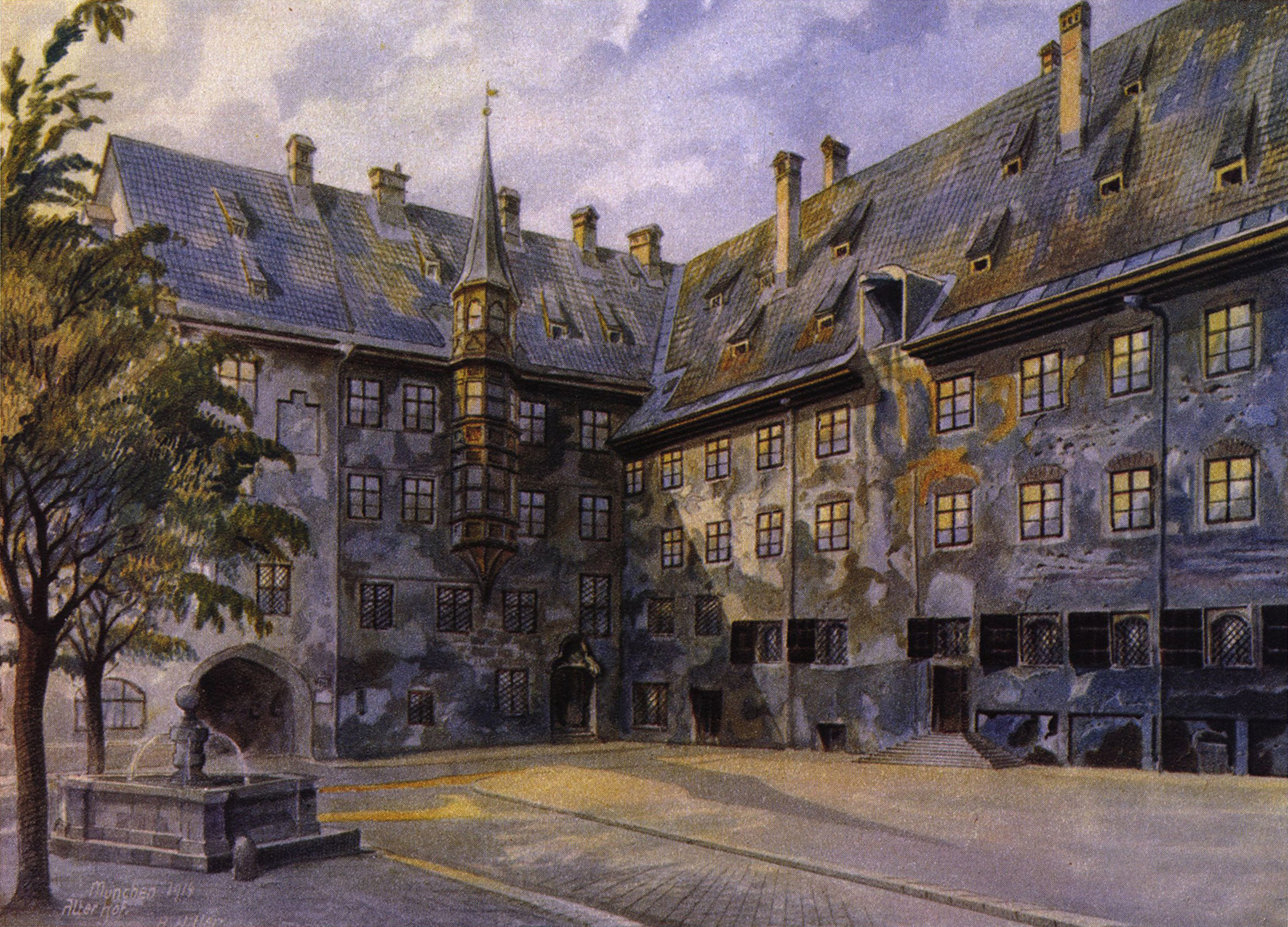

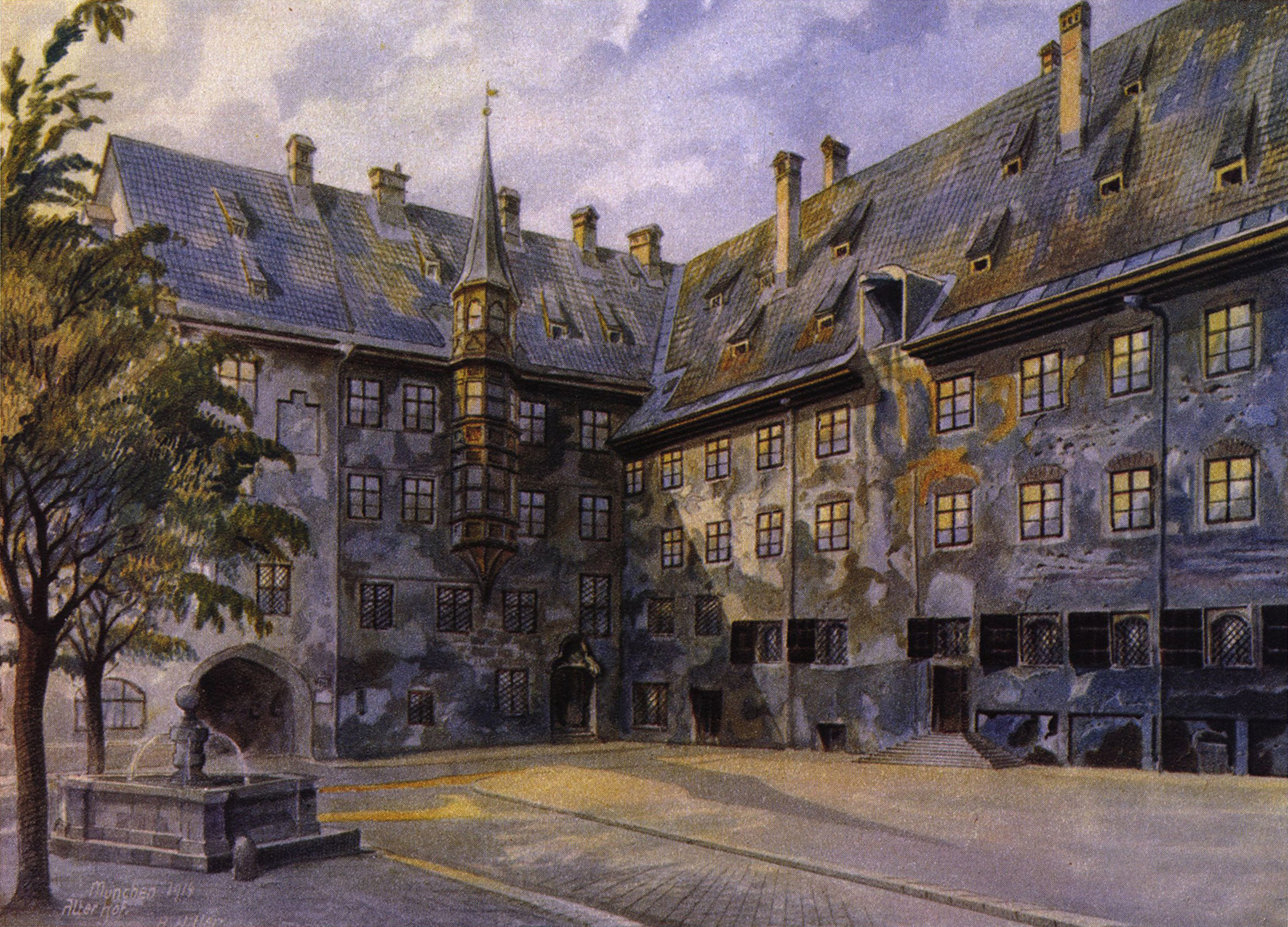

Meldemannstraße dormitory. He earned money as a casual labourer and by painting and selling

watercolours

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin 'water'), is a painting method"Watercolor may be as old as art itself, going back to the S ...

of Vienna's sights. During his time in Vienna, he pursued a growing passion for architecture and music, attending ten performances of , his favourite of

Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

's operas.

In Vienna, Hitler was first exposed to racist rhetoric.

Populists such as mayor

Karl Lueger exploited the city's prevalent

antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

sentiment, occasionally also espousing German nationalist notions for political benefit. German nationalism was even more widespread in the

Mariahilf

Mariahilf (; ; "Mary's help") is the 6th municipal district of Vienna, Austria (). It is near the center of Vienna and was established as a district in 1850. Mariahilf is a heavily populated urban area with many residential buildings.

Wien.gv.a ...

district, where Hitler then lived.

Georg Ritter von Schönerer became a major influence on Hitler, and he developed an admiration for

Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

. Hitler read local newspapers that promoted prejudice and used Christian fears of being swamped by an influx of Eastern European Jews as well as pamphlets that published the thoughts of philosophers and theoreticians such as

Houston Stewart Chamberlain

Houston Stewart Chamberlain (; 9 September 1855 – 9 January 1927) was a British-German-French philosopher who wrote works about political philosophy and natural science. His writing promoted German ethnonationalism, antisemitism, scientific r ...

,

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

,

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

,

Gustave Le Bon

Charles-Marie Gustave Le Bon (7 May 1841 – 13 December 1931) was a leading French polymath whose areas of interest included anthropology, psychology, sociology, medicine, invention, and physics. He is best known for his 1895 work '' The Crowd: ...

, and

Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the Phenomenon, phenomenal world as ...

. During his life in Vienna, Hitler also developed fervent

anti-Slavic sentiments.

The origin and development of Hitler's antisemitism remain a matter of debate. His friend

August Kubizek claimed that Hitler was a "confirmed antisemite" before he left Linz. However, the historian

Brigitte Hamann describes Kubizek's claim as "problematical". While Hitler states in that he first became an antisemite in Vienna,

Reinhold Hanisch, who helped him to sell his paintings, disagrees. Hitler had dealings with Jews while living in Vienna. The historian

Richard J. Evans states that "historians now generally agree that his notorious, murderous antisemitism emerged well after Germany's defeat

n World War I as a product of the paranoid

"stab-in-the-back" explanation for the catastrophe".

Hitler received the final part of his father's estate in May 1913 and moved to

Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

, Germany. When he was conscripted into the

Austro-Hungarian Army

The Austro-Hungarian Army, also known as the Imperial and Royal Army,; was the principal ground force of Austria-Hungary from 1867 to 1918. It consisted of three organisations: the Common Army (, recruited from all parts of Austria-Hungary), ...

, he journeyed to

Salzburg

Salzburg is the List of cities and towns in Austria, fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020 its population was 156,852. The city lies on the Salzach, Salzach River, near the border with Germany and at the foot of the Austrian Alps, Alps moun ...

on 5 February 1914 for medical assessment. After he was deemed unfit for service, he returned to Munich. Hitler later claimed that he did not wish to serve the

Habsburg Empire

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

because of the mixture of races in its army and his belief that the collapse of Austria-Hungary was imminent.

World War I

In August 1914, at the outbreak of

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Hitler was living in Munich and voluntarily enlisted in the

Bavarian Army

The Bavarian Army () was the army of the Electorate of Bavaria, Electorate (1682–1806) and then Kingdom of Bavaria, Kingdom (1806–1918) of Bavaria. It existed from 1682 as the standing army of Bavaria until the merger of the military sovereig ...

. According to a 1924 report by the Bavarian authorities, allowing Hitler to serve was most likely an administrative error, because as an Austrian citizen, he should have been returned to Austria. Posted to the

Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16 (1st Company of the List Regiment), he served as a dispatch

runner on the

Western Front in France and Belgium, spending nearly half his time at the regimental headquarters in

Fournes-en-Weppes, well behind the front lines. In 1914, he was present at the

First Battle of Ypres

The First Battle of Ypres (, , – was a battle of the First World War, fought on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front around Ypres, in West Flanders, Belgium. The battle was part of the First Battle of Flanders, in which German A ...

and in that year was decorated for bravery, receiving the

Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, the German Empire (1871–1918), and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). The design, a black cross pattée with a white or silver outline, was derived from the in ...

, Second Class. During the war, he was saved by his commanding officer,

Fritz Wiedemann, who pulled Hitler out of the rubble of a collapsed building while under heavy fire.

During his service at headquarters, Hitler pursued his artwork, drawing cartoons and instructions for an army newspaper. During the

Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme (; ), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and the French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place between 1 July and 18 Nove ...

in October 1916, he was wounded in the left thigh when a shell exploded in the dispatch runners' dugout. Hitler spent almost two months recovering in hospital at

Beelitz

Beelitz () is a historic town in Potsdam-Mittelmark district, in Brandenburg, Germany. It is chiefly known for its cultivation of white asparagus (''Beelitzer Spargel'').

Geography

Beelitz is situated about 18 km (11 mi) south of Potsda ...

, returning to his regiment on 5 March 1917. He was present at the

Battle of Arras of 1917 and the

Battle of Passchendaele

The Third Battle of Ypres (; ; ), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele ( ), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by the Allies of World War I, Allies against the German Empire. The battle took place on the Western Front (World Wa ...

. He received the

Black Wound Badge on 18 May 1918. Three months later, in August 1918, on a recommendation by Lieutenant

Hugo Gutmann, his Jewish superior, Hitler received the Iron Cross, First Class, a decoration rarely awarded at Hitler's rank. On 15 October 1918, he was temporarily blinded in a

mustard gas

Mustard gas or sulfur mustard are names commonly used for the organosulfur compound, organosulfur chemical compound bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide, which has the chemical structure S(CH2CH2Cl)2, as well as other Chemical species, species. In the wi ...

attack and was hospitalised in

Pasewalk

Pasewalk () is a town in the Vorpommern-Greifswald district, in the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in north-eastern Germany. Located on the Uecker river, it is the capital of the former Uecker-Randow district, and the seat of the Uecker-Randow-T ...

. While there, Hitler learned of Germany's defeat, and, by his own account, suffered a second bout of blindness after receiving this news.

Hitler described his role in World War I as "the greatest of all experiences", and was praised by his commanding officers for his bravery. His wartime experience reinforced his German patriotism, and he was shocked by Germany's capitulation in November 1918. His displeasure with the collapse of the war effort began to shape his ideology. Like other German nationalists, he believed the (

stab-in-the-back myth), which claimed that the German army, "undefeated in the field", had been "stabbed in the back" on the

home front

Home front is an English language term with analogues in other languages. It is commonly used to describe the civilian populace of the nation at war as an active support system for their military.

Civilians are traditionally uninvolved in com ...

by civilian leaders, Jews,

Marxists

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, and ...

, and those who signed the

armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

that ended the fighting—later dubbed the "November criminals".

The

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

stipulated that Germany had to relinquish several of its territories and

demilitarise the

Rhineland

The Rhineland ( ; ; ; ) is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly Middle Rhine, its middle section. It is the main industrial heartland of Germany because of its many factories, and it has historic ties to the Holy ...

. The treaty imposed economic sanctions and levied heavy reparations on the country. Many Germans saw the treaty as an unjust humiliation. They especially objected to

Article 231, which they interpreted as declaring Germany responsible for the war. The Versailles Treaty and the economic, social, and political conditions in Germany after the war were later exploited by Hitler for political gain.

Entry into politics

After the war, Hitler returned to Munich. Without formal education or career prospects, he remained in the Army. In July 1919, he was appointed (intelligence agent) of an (reconnaissance unit) of the , assigned to influence other soldiers and to infiltrate the

German Workers' Party

The German Workers' Party (, DAP) was a short-lived far-right political party established in the Weimar Republic after World War I. It only lasted from 5 January 1919 until 24 February 1920. The DAP was the precursor of the National Socialist ...

(DAP). At a DAP meeting on 12 September 1919, Party chairman

Anton Drexler

Anton Drexler (13 June 1884 – 24 February 1942) was a German far-right political agitator for the ''Völkisch'' movement in the 1920s. He founded the German Workers' Party (DAP), the pan-German and anti-Semitic antecedent of the Nazi Part ...

was impressed by Hitler's oratorical skills. He gave him a copy of his pamphlet ''My Political Awakening'', which contained antisemitic, nationalist,

anti-capitalist

Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and Political movement, movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. Anti-capitalists seek to combat the worst effects of capitalism and to eventually replace capitalism ...

, and anti-Marxist ideas. On the orders of his army superiors, Hitler applied to join the party, and within a week was accepted as party member 555 (the party began counting membership at 500 to give the impression they were a much larger party).

Hitler made his earliest known written statement about the

Jewish question

The Jewish question was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century Europe that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other " national questions", dealt with the civil, legal, national, ...

in a 16 September 1919 letter to Adolf Gemlich (now known as the

Gemlich letter). In the letter, Hitler argues that the aim of the government "must unshakably be the removal of the Jews altogether". At the DAP, Hitler met

Dietrich Eckart

Dietrich Eckart (; 23 March 1868 – 26 December 1923) was a German '' völkisch'' poet, playwright, journalist, publicist, and political activist who was one of the founders of the German Workers' Party, the precursor of the Nazi Party. Eckart ...

, one of the party's founders and a member of the occult

Thule Society. Eckart became Hitler's mentor, exchanging ideas with him and introducing him to a wide range of Munich society. To increase its appeal, the DAP changed its name to the (

National Socialist German Workers' Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

(NSDAP), now known as the "Nazi Party"). Hitler designed the party's banner of a

swastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍, ) is a symbol used in various Eurasian religions and cultures, as well as a few Indigenous peoples of Africa, African and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, American cultures. In the Western world, it is widely rec ...

in a white circle on a red background.

Hitler was discharged from the Army on 31 March 1920 and began working full-time for the party. The party headquarters was in Munich, a centre for anti-government German nationalists determined to eliminate Marxism and undermine the

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

. In February 1921—already highly effective at

crowd manipulation

Crowd manipulation is the intentional or unwitting use of techniques based on the principles of crowd psychology to engage, control, or influence the desires of a crowd in order to direct its behavior toward a specific action.

Historical analy ...

—he spoke to a crowd of over 6,000. To publicise the meeting, two truckloads of party supporters drove around Munich waving swastika flags and distributing leaflets. Hitler soon gained notoriety for his rowdy

polemic

Polemic ( , ) is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called polemics, which are seen in arguments on controversial to ...

speeches against the Treaty of Versailles, rival politicians, and especially against Marxists and Jews.

In June 1921, while Hitler and Eckart were on a fundraising trip to

Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, a mutiny broke out within the Nazi Party in Munich. Members of its executive committee wanted to merge with the Nuremberg-based

German Socialist Party

The German Socialist Party (, abbreviated DSP) was a short-lived far-right and ''völkisch'' political party active in Germany during the early Weimar Republic. Founded in 1918, it aimed to combine radical nationalist ideology with a populist ap ...

(DSP). Hitler returned to Munich on 11 July and angrily tendered his resignation. The committee members realised that the resignation of their leading public figure and speaker would mean the end of the party. Hitler announced he would rejoin on the condition that he would replace Drexler as party chairman, and that the party headquarters would remain in Munich. The committee agreed, and he rejoined the party on 26 July as member 3,680. Hitler continued to face some opposition within the Nazi Party. Opponents of Hitler in the leadership had

Hermann Esser expelled from the party, and they printed 3,000 copies of a pamphlet attacking Hitler as a traitor to the party. In the following days, Hitler spoke to several large audiences and defended himself and Esser, to thunderous applause. His strategy proved successful, and at a special party congress on 29 July, he was granted absolute power as party chairman, succeeding Drexler, by a vote of 533 to 1.

Hitler's vitriolic beer hall speeches began attracting regular audiences. A

demagogue

A demagogue (; ; ), or rabble-rouser, is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, especially through oratory that whips up the passions of crowds, Appeal to emotion, appealing to emo ...

, he became adept at using populist themes, including the use of

scapegoat

In the Bible, a scapegoat is one of a pair of kid goats that is released into the wilderness, taking with it all sins and impurities, while the other is sacrificed. The concept first appears in the Book of Leviticus, in which a goat is designate ...

s, who were blamed for his listeners' economic hardships. Hitler used personal magnetism and an understanding of

crowd psychology

Crowd psychology (or mob psychology) is a subfield of social psychology which examines how the psychology of a group of people differs from the psychology of any one person within the group. The study of crowd psychology looks into the actions ...

to his advantage while engaged in public speaking. Historians have noted the hypnotic effect of his rhetoric on large audiences, and of his eyes in small groups.

Alfons Heck, a former member of the

Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth ( , often abbreviated as HJ, ) was the youth wing of the German Nazi Party. Its origins date back to 1922 and it received the name ("Hitler Youth, League of German Worker Youth") in July 1926. From 1936 until 1945, it was th ...

, recalled:

Early followers included

Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician, Nuremberg trials, convicted war criminal and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer ( ...

, the former air force ace

Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician, aviator, military leader, and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which gov ...

, and the army captain

Ernst Röhm

Ernst Julius Günther Röhm (; 28 November 1887 – 1 July 1934) was a German military officer, politician and a leading member of the Nazi Party. A close friend and early ally of Adolf Hitler, Röhm was the co-founder and leader of the (SA), t ...

. Röhm became head of the Nazis' paramilitary organisation, the (SA, "Stormtroopers"), which protected meetings and attacked political opponents. A critical influence on Hitler's thinking during this period was the , a conspiratorial group of

White Russian exiles and early Nazis. The group, financed with funds channelled from wealthy industrialists, introduced Hitler to the idea of a Jewish conspiracy, linking international finance with

Bolshevism

Bolshevism (derived from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Leninist and later Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined p ...

.

The programme of the Nazi Party was laid out in their

25-point programme on 24 February 1920. This did not represent a coherent ideology, but was a conglomeration of received ideas which had currency in the

pan-Germanic

Pan-Germanism ( or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalism, pan-nationalist political ideology, political idea. Pan-Germanism seeks to unify all ethnic Germans, German-speaking Europe, German-speaking people, and po ...

movement, such as

ultranationalism

Ultranationalism, or extreme nationalism, is an extremist form of nationalism in which a country asserts or maintains hegemony, supremacy, or other forms of control over other nations (usually through violent coercion) to pursue its specific i ...

, opposition to the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

, distrust of

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

, as well as some

socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

ideas. For Hitler, the most important aspect of it was its strong

antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

stance. He also perceived the programme as primarily a basis for propaganda and for attracting people to the party.

Beer Hall Putsch and Landsberg Prison

In 1923, Hitler enlisted the help of World War I General

Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (; 9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general and politician. He achieved fame during World War I (1914–1918) for his central role in the German victories at Battle of Liège, Liège and Battle ...

for an attempted coup known as the "

Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and other leaders i ...

". The Nazi Party used

Italian Fascism

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

as a model for their appearance and policies. Hitler wanted to emulate

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

's "

March on Rome

The March on Rome () was an organized mass demonstration in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (, PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 1922, Fascist Party leaders planned a march ...

" of 1922 by staging his own coup in Bavaria, to be followed by a challenge to the government in Berlin. Hitler and Ludendorff sought the support of (State Commissioner)

Gustav Ritter von Kahr

Gustav Ritter von Kahr (; born Gustav Kahr; 29 November 1862 – 30 June 1934) was a German jurist and right-wing politician. During his career he was district president of Upper Bavaria, Bavarian minister president and, from September 1923 to ...

, Bavaria's ''de facto'' ruler. However, Kahr, along with Police Chief

Hans Ritter von Seisser

Colonel Hans Ritter von Seisser (German ''Seißer''; 9 December 1874 – 14 April 1973) was the head of the Bavarian State Police in 1923.

In September 1923, following a period of turmoil and political violence, Bavarian Prime Minister Eugen ...

and Reichswehr General

Otto von Lossow

Otto Hermann von Lossow (15 January 1868 – 25 November 1938) was a Bavarian Army and then German Army officer who played a prominent role in the events surrounding the attempted Beer Hall Putsch by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in November 19 ...

, wanted to install a nationalist dictatorship without Hitler.

On 8 November 1923, Hitler and the SA stormed a public meeting of 3,000 people organised by Kahr in the

Bürgerbräukeller, a beer hall in Munich. Interrupting Kahr's speech, he announced that the national revolution had begun and declared the formation of a new government with Ludendorff. Retiring to a back room, Hitler, with his pistol drawn, demanded and subsequently received the support of Kahr, Seisser, and Lossow. Hitler's forces initially succeeded in occupying the local Reichswehr and police headquarters, but Kahr and his cohorts quickly withdrew their support. Neither the Army nor the state police joined forces with Hitler. The next day, Hitler and his followers marched from the beer hall to the

Bavarian War Ministry

The Ministry of War () was a ministry for military affairs of the Kingdom of Bavaria, founded as ''Ministerium des Kriegswesens'' on October 1, 1808 by King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria. It was located on the Ludwigstraße (Munich), Ludwigstraß ...

to overthrow the Bavarian government, but police dispersed them. In the failed coup, 16 Nazi Party members and four police officers were killed.

Hitler fled to the home of

Ernst Hanfstaengl and by some accounts contemplated suicide. He was depressed but calm when arrested on 11 November 1923 for

high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its d ...

. His trial before the special

People's Court in Munich began in February 1924, and

Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head o ...

became temporary leader of the Nazi Party. On 1 April, Hitler was sentenced to five years' ('fortress confinement') at

Landsberg Prison

Landsberg Prison is a prison in the town of Landsberg am Lech in the southwest of the German state of Bavaria, about west-southwest of Munich and south of Augsburg. It is best known as the prison where Adolf Hitler was held in 1924, after the ...

. There, he received friendly treatment from the guards, and was allowed mail from supporters and regular visits by party comrades. Pardoned by the Bavarian Supreme Court, he was released from jail on 20 December 1924, against the state prosecutor's objections. Including time on remand, Hitler served just over one year in prison.

While at Landsberg, Hitler dictated most of the first volume of ''

Mein Kampf

(; ) is a 1925 Autobiography, autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The book outlines many of Political views of Adolf Hitler, Hitler's political beliefs, his political ideology and future plans for Nazi Germany, Ge ...

'' (; originally titled ''Four and a Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice'') at first to his chauffeur,

Emil Maurice, and then to his deputy,

Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician, Nuremberg trials, convicted war criminal and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer ( ...

. The book, dedicated to Thule Society member Dietrich Eckart, was an autobiography and exposition of his ideology. The book laid out Hitler's plans for territorial expansion as well as transforming German society into a dictatorship based on race. Throughout the book, Jews are equated with "germs" and presented as the "international poisoners" of society. According to Hitler's ideology, the only solution was their extermination. While Hitler did not describe exactly how this was to be accomplished, his "inherent genocidal thrust is undeniable", according to

Ian Kershaw

Sir Ian Kershaw (born 29 April 1943) is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's foremost experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is ...

.

Published in two volumes in 1925 and 1926, sold 228,000 copies between 1925 and 1932. One million copies were sold in 1933, Hitler's first year in office. Shortly before Hitler was eligible for parole, the Bavarian government attempted to have him deported to Austria. The Austrian federal chancellor rejected the request on the specious grounds that his service in the German Army made his Austrian citizenship void. In response, Hitler formally renounced his Austrian citizenship on 7 April 1925.

Rebuilding the Nazi Party

At the time of Hitler's release from prison, politics in Germany had become less combative and the economy had improved, limiting Hitler's opportunities for political agitation. As a result of the failed Beer Hall Putsch, the Nazi Party and its affiliated organisations were banned in Bavaria. In a meeting with the Prime Minister of Bavaria,

Heinrich Held

Heinrich Held (6 June 1868 – 4 August 1938) was a German Catholic politician and Minister President of Bavaria. He was forced out of office by the Nazi takeover in Germany in 1933.

Biography

Heinrich Held was born in Erbach in the Taunus, ...

, on 4 January 1925, Hitler agreed to respect the state's authority and promised that he would seek political power only through the democratic process. The meeting paved the way for the ban on the Nazi Party to be lifted on 16 February.

However, after an inflammatory speech he gave on 27 February, Hitler was barred from public speaking by the Bavarian authorities, a ban that remained in place until 1927. To advance his political ambitions in spite of the ban, Hitler appointed

Gregor Strasser,

Otto Strasser

Otto Johann Maximilian Strasser (also , see ß; 10 September 1897 – 27 August 1974) was a German politician and an early member of the Nazi Party. Otto Strasser, together with his brother Gregor Strasser, was a leading member of the party's ...

, and

Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and philologist who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief Propaganda in Nazi Germany, propagandist for the Nazi Party, and ...

to organise and enlarge the Nazi Party in northern Germany. Gregor Strasser steered a more independent political course, emphasising the socialist elements of the party's programme.

The stock market in the United States

crashed on 24 October 1929. The impact in Germany was dire: millions became unemployed and several major banks collapsed. Hitler and the Nazi Party prepared to take advantage of the emergency to gain support for their party. They promised to repudiate the Versailles Treaty, strengthen the economy, and provide jobs.

Rise to power

Brüning administration

The

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

provided a political opportunity for Hitler. Germans were ambivalent about the

parliamentary republic

A parliamentary republic is a republic that operates under a parliamentary system of government where the Executive (government), executive branch (the government) derives its legitimacy from and is accountable to the legislature (the parliament). ...

, which faced challenges from

right- and

left-wing extremists. The moderate political parties were increasingly unable to stem the tide of extremism, and the

German referendum of 1929 helped to elevate Nazi ideology. The elections of September 1930 resulted in the break-up of a

grand coalition

A grand coalition is an arrangement in a multi-party parliamentary system in which the two largest political party, political parties of opposing political spectrum, political ideologies unite in a coalition government.

Causes of a grand coali ...

and its replacement with a minority cabinet. Its leader, chancellor

Heinrich Brüning

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning (; 26 November 1885 – 30 March 1970) was a German Centre Party politician and academic, who served as the chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1930 to 1932.

A political scientis ...

of the

Centre Party, governed through

emergency decrees from President

Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military and political leader who led the Imperial German Army during the First World War and later became President of Germany (1919� ...

. Governance by decree became the new norm and paved the way for authoritarian forms of government. The Nazi Party rose from obscurity to win 18.3 per cent of the vote and 107 parliamentary seats in the 1930 election, becoming the second-largest party in parliament.

Hitler made a prominent appearance at the trial of two Reichswehr officers, Lieutenants Richard Scheringer and

Hanns Ludin, in late 1930. Both were charged with membership in the Nazi Party, at that time illegal for Reichswehr personnel. The prosecution argued that the Nazi Party was an extremist party, prompting defence lawyer Hans Frank to call on Hitler to testify. On 25 September 1930, Hitler testified that his party would pursue political power solely through democratic elections, which won him many supporters in the officer corps.

Brüning's austerity measures brought little economic improvement and were extremely unpopular. Hitler exploited this by targeting his political messages specifically at people who had been affected by the inflation of the 1920s and the Depression, such as farmers, war veterans, and the middle class.

Although Hitler had terminated his Austrian citizenship in 1925, he did not acquire German citizenship for almost seven years. This meant that he was

stateless, legally unable to run for public office, and still faced the risk of deportation. On 25 February 1932, the interior minister of

Brunswick,

Dietrich Klagges, who was a member of the Nazi Party, appointed Hitler as administrator for the state's delegation to the

Reichsrat in Berlin, making Hitler a citizen of Brunswick, and thus of Germany.

Hitler ran against Hindenburg in

the 1932 presidential election. A speech to the Industry Club in

Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in the state after Cologne and the List of cities in Germany with more than 100,000 inhabitants, seventh-largest city ...

on 27 January 1932 won him support from many of Germany's most powerful industrialists. Hindenburg had support from various nationalist, monarchist, Catholic, and

republican parties, and some

Social Democrats

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

. Hitler used the campaign slogan "" ("Hitler over Germany"), a reference to his political ambitions and his campaigning by aircraft. He was one of the first politicians to use aircraft travel for campaigning and used it effectively. Hitler came in second in both rounds of the election, garnering more than 35 per cent of the vote in the final election. Although he lost to Hindenburg, this election established Hitler as a strong force in German politics.

Appointment as chancellor

The absence of an effective government prompted two influential politicians,

Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and army officer. A national conservative, he served as Chancellor of Germany in 1932, and then as Vice-Chancell ...

and

Alfred Hugenberg

Alfred Ernst Christian Alexander Hugenberg (19 June 1865 – 12 March 1951) was an influential German businessman and politician. An important figure in nationalist politics in Germany during the first three decades of the twentieth century, ...

, along with several other industrialists and businessmen, to write a letter to Hindenburg. The signers urged Hindenburg to appoint Hitler as leader of a government "independent from parliamentary parties", which could turn into a movement that would "enrapture millions of people".

Hindenburg reluctantly agreed to appoint Hitler as chancellor after two further parliamentary elections—in July and November 1932—had not resulted in the formation of a majority government. Hitler headed a short-lived coalition government formed by the Nazi Party (which had the most seats in the Reichstag) and Hugenberg's party, the

German National People's Party

The German National People's Party (, DNVP) was a national-conservative and German monarchy, monarchist political party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major nationalist party in Weimar German ...

(DNVP). On 30 January 1933, the new cabinet was sworn in during a brief ceremony in Hindenburg's office. The Nazi Party gained three posts: Hitler was named chancellor,

Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a German prominent politician of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and convicted war criminal who served as Minister of the Interior in Adolf Hitler's cabinet from 1933 to 1943 and as the last governor ...

Minister of the Interior, and Hermann Göring Minister of the Interior for Prussia. Hitler had insisted on the ministerial positions as a way to gain control over the police in much of Germany.

Reichstag fire and March elections

As chancellor, Hitler worked against attempts by the Nazi Party's opponents to build a majority government. Because of the political stalemate, he asked Hindenburg to again dissolve the Reichstag, and elections were scheduled for early March. On 27 February 1933, the

Reichstag building was set on fire. Göring blamed a communist plot, as the Dutch communist

Marinus van der Lubbe

Marinus van der Lubbe (; 13 January 1909 – 10 January 1934) was a Dutch communist who was tried, convicted, and executed by the government of Nazi Germany for setting fire to the Reichstag building—the national parliament of Germany—on ...

was found in incriminating circumstances inside the burning building. Until the 1960s, some historians, including

William L. Shirer and

Alan Bullock

Alan Louis Charles Bullock, Baron Bullock (13 December 1914 – 2 February 2004) was a British historian. He is best known for his book ''Hitler: A Study in Tyranny'' (1952), the first comprehensive biography of Adolf Hitler, which influenced m ...

, thought the Nazi Party was responsible; now the view of most historians is van der Lubbe started the fire alone.

At Hitler's urging, Hindenburg responded by signing the

Reichstag Fire Decree

The Reichstag Fire Decree () is the common name of the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State () issued by German President Paul von Hindenburg on the advice of Chancellor Adolf Hitler on 28 February 1933 in immed ...

of 28 February, drafted by the Nazis, which suspended basic rights and allowed detention without trial. The decree was permitted under

Article 48

Article 48 of the Weimar constitution, constitution of the Weimar Republic of Germany (1919–1933) allowed the President of Germany (1919–1945), Reich president, under certain circumstances, to take emergency measures without the prior consen ...

of the Weimar Constitution, which gave the president the power to take emergency measures to protect public safety and order. Activities of the

German Communist Party (KPD) were suppressed, and 4,000 KPD members were arrested.

In addition to political campaigning, the Nazi Party engaged in paramilitary violence and the spread of anti-communist propaganda, in the days preceding

the election. On election day, 6 March 1933, the Nazi's share of the vote increased to 44%, and the party acquired the largest number of seats in parliament. Hitler's party failed to secure an absolute majority, necessitating another coalition with the DNVP.

Day of Potsdam and the Enabling Act

On 21 March 1933, the new ''Reichstag'' was constituted with an opening ceremony at the

Garrison Church in

Potsdam

Potsdam () is the capital and largest city of the Germany, German States of Germany, state of Brandenburg. It is part of the Berlin/Brandenburg Metropolitan Region. Potsdam sits on the Havel, River Havel, a tributary of the Elbe, downstream of B ...

. This "Day of Potsdam" was held to demonstrate unity between the Nazi movement and the old

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

n elite and military. Hitler appeared in a

morning coat

A tailcoat is a knee-length coat characterised by a rear section of the skirt (known as the ''tails''), with the front of the skirt cut away.

The tailcoat shares its historical origins in clothes cut for convenient horse-riding in the Early ...

and humbly greeted Hindenburg.

To achieve full political control despite not having an absolute majority in parliament, Hitler's government brought the (Enabling Act) to a vote in the newly elected ''Reichstag''. The Act—officially titled the ("Law to Remedy the Distress of People and Reich")—gave Hitler's cabinet the power to enact laws without the consent of the Reichstag for four years. These laws could (with certain exceptions) deviate from the constitution.

Since it would affect the constitution, the Enabling Act required a two-thirds majority to pass. Leaving nothing to chance, the Nazis used the provisions of the Reichstag Fire Decree to arrest all 81 Communist deputies (in spite of their virulent campaign against the party, the Nazis had allowed the KPD to contest the election) and prevent several Social Democrats from attending.

On 23 March 1933, the ''Reichstag'' assembled at the

Kroll Opera House

The Kroll Opera House () in Berlin, Germany, was in the Tiergarten district on the western edge of the '' Königsplatz'' square (today ''Platz der Republik''), facing the Reichstag building. It was built in 1844 as an entertainment venue for th ...

under turbulent circumstances. Ranks of SA men served as guards inside the building, while large groups outside opposing the proposed legislation shouted slogans and threats towards the arriving members of parliament. After Hitler verbally promised Centre party leader

Ludwig Kaas

Ludwig Kaas (23 May 1881 – 15 April 1952) was a German Roman Catholic priest and politician of the Centre Party during the Weimar Republic. He was instrumental in brokering the Reichskonkordat between the Holy See and the German Reich.

...

that Hindenburg would retain his power of veto, Kaas announced the Centre Party would support the Enabling Act. The Act passed by a vote of 444–94, with all parties except the Social Democrats voting in favour. The Enabling Act, along with the Reichstag Fire Decree, transformed Hitler's government into a ''de facto'' legal dictatorship.

Dictatorship

Having achieved full control over the legislative and executive branches of government, Hitler and his allies began to suppress the remaining opposition. The Social Democratic Party was made illegal, and its assets were seized. While many

trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

delegates were in Berlin for May Day activities, SA stormtroopers occupied union offices around the country. On 2 May 1933, all trade unions were forced to dissolve, and their leaders were arrested. Some were sent to

concentration camps

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploit ...

. The

German Labour Front

The German Labour Front (, ; DAF) was the national labour organization of the Nazi Party, which replaced the various independent trade unions in Germany during the process of ''Gleichschaltung'' or Nazification.

History

As early as March 1933, ...

was formed as an umbrella organisation to represent all workers, administrators, and company owners, thus reflecting the concept of Nazism in the spirit of Hitler's ("people's community").

By the end of June, the other parties had been intimidated into disbanding. This included the Nazis' nominal coalition partner, the DNVP; with the SA's help, Hitler forced its leader, Hugenberg, to resign on 29 June. On 14 July 1933, the Nazi Party was declared the only legal political party in Germany. The demands of the SA for more political and military power caused anxiety among military, industrial, and political leaders. In response, Hitler purged the entire SA leadership in the

Night of the Long Knives

The Night of the Long Knives (, ), also called the Röhm purge or Operation Hummingbird (), was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Chancellor Adolf Hitler, urged on by Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler, ord ...

, which took place from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Hitler targeted Ernst Röhm and other SA leaders who, along with a number of Hitler's political adversaries (such as Gregor Strasser and former chancellor

Kurt von Schleicher

Kurt Ferdinand Friedrich Hermann von Schleicher (; 7 April 1882 – 30 June 1934) was a German military officer and the penultimate Chancellor of Germany#First German Republic (Weimar Republic, 1919–1933), chancellor of Germany during the Weim ...

), were rounded up, arrested, and shot. While the international community and some Germans were shocked by the killings, many in Germany believed Hitler was restoring order.

Hindenburg died on 2 August 1934. On the previous day, the cabinet had enacted the

Law Concerning the Head of State of the German Reich. This law stated that upon Hindenburg's death, the office of president would be abolished, and its powers merged with those of the chancellor. Hitler thus became head of state as well as head of government and was formally named as (Leader and Chancellor of the Reich), although was eventually dropped. With this action, Hitler eliminated the last legal remedy by which he could be removed from office.

As head of state, Hitler became commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Immediately after Hindenburg's death, at the instigation of the leadership of the , the traditional loyalty oath of soldiers was altered to

affirm loyalty to Hitler personally, by name, rather than to the office of commander-in-chief (which was later renamed to supreme commander) or to Germany. On 19 August, the merger of the presidency with the chancellorship was approved by 88 per cent of the electorate voting in a

plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

.

In early 1938, Hitler used blackmail to consolidate his hold over the military by instigating the

Blomberg–Fritsch affair

The Blomberg–Fritsch affair, also known as the Blomberg–Fritsch crisis ( German: ''Blomberg–Fritsch–Krise''), was the name given to two related scandals that occurred in the ''Wehrmacht'' of Nazi Germany in early 1938.

Adolf Hitler had be ...

. Hitler forced his War Minister, Field Marshal

Werner von Blomberg

Werner Eduard Fritz von Blomberg (2 September 1878 – 13 March 1946) was a German general and politician who served as the first Minister of War in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1938. Blomberg had served as Chief of the ''Truppenamt'', equivalent ...

, to resign by using a police dossier that showed that Blomberg's new wife had a record for prostitution. Army commander Colonel-General

Werner von Fritsch

Thomas Ludwig Werner Freiherr von Fritsch (4 August 1880 – 22 September 1939) was a German ''Generaloberst'' (Full General, full general) who served as Oberkommando des Heeres, Commander-in-Chief of the German Army (Wehrmacht), German Army fro ...

was removed after the (SS) produced allegations that he had engaged in a homosexual relationship. Both men had fallen into disfavour because they objected to Hitler's demand to make the ready for war as early as 1938. Hitler assumed Blomberg's title of Commander-in-Chief, thus taking personal command of the armed forces. He replaced the Ministry of War with the (OKW), headed by General

Wilhelm Keitel

Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel (; 22 September 188216 October 1946) was a German field marshal who held office as chief of the (OKW), the high command of Nazi Germany's armed forces, during World War II. He signed a number of criminal ...

. On the same day, 16 generals were stripped of their commands and 44 more were transferred; all were suspected of not being sufficiently pro-Nazi. By early February 1938, 12 more generals had been removed.

Hitler took care to give his dictatorship the appearance of legality. Many of his decrees were explicitly based on the Reichstag Fire Decree and hence on Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution. The ''Reichstag'' renewed the Enabling Act twice, each time for a four-year period. While elections to the ''Reichstag'' were still held (in 1933, 1936, and 1938), voters were presented with a single list of Nazis and pro-Nazi "guests" which received well over 90 per cent of the vote. These sham elections were held in far-from-secret conditions; the Nazis threatened severe reprisals against anyone who did not vote or who voted against.

Nazi Germany

Economy and culture

In August 1934, Hitler appointed President

Hjalmar Schacht

Horace Greeley Hjalmar Schacht (); 22 January 1877 – 3 June 1970) was a German economist, banker, politician, and co-founder of the German Democratic Party. He served as the Currency Commissioner and President of the Reichsbank during the ...

as Minister of Economics, and in the following year, as Plenipotentiary for War Economy in charge of preparing the economy for war. Reconstruction and rearmament were financed through

Mefo bills

A Mefo bill (sometimes written as MEFO bill) was a six-month promissory note, drawn upon the dummy company MEFO, Metallurgische Forschungsgesellschaft (Metallurgical Research Corporation), devised by the Reichsbank, German Central Bank President, ...

, printing money, and seizing the assets of people arrested as