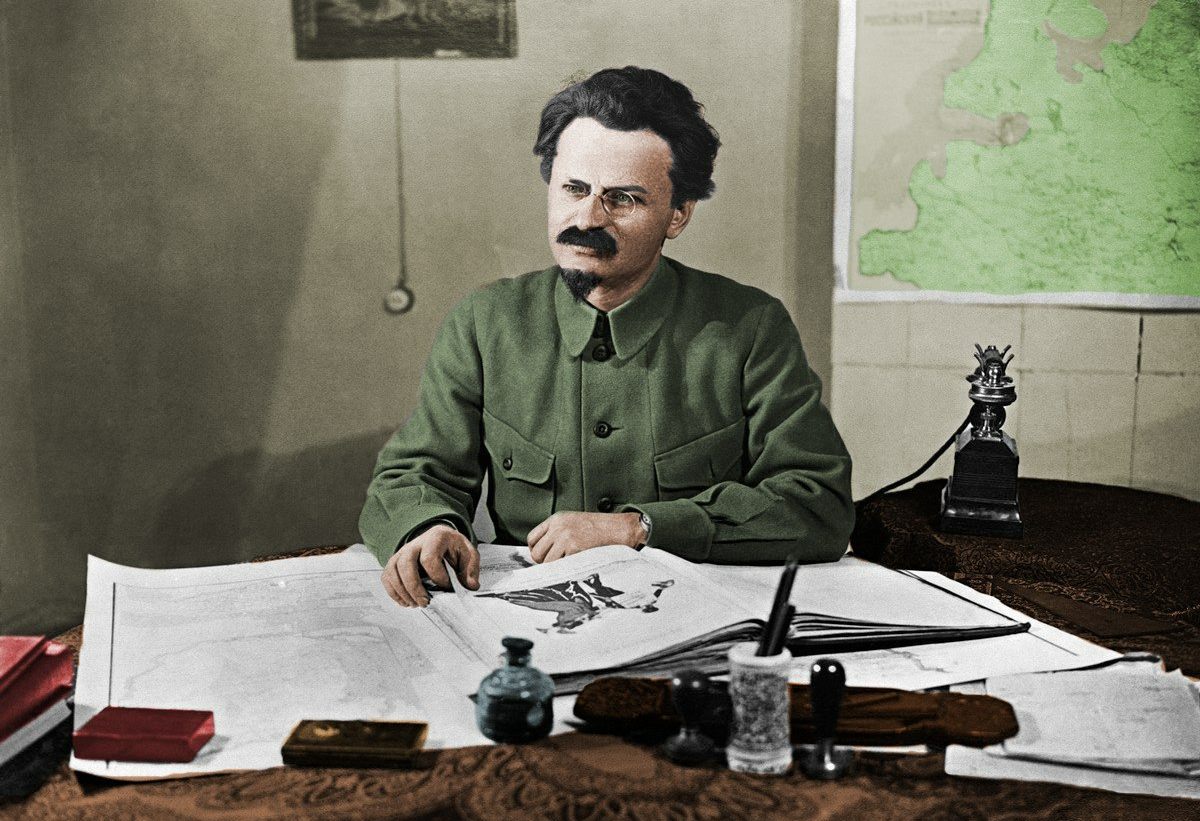

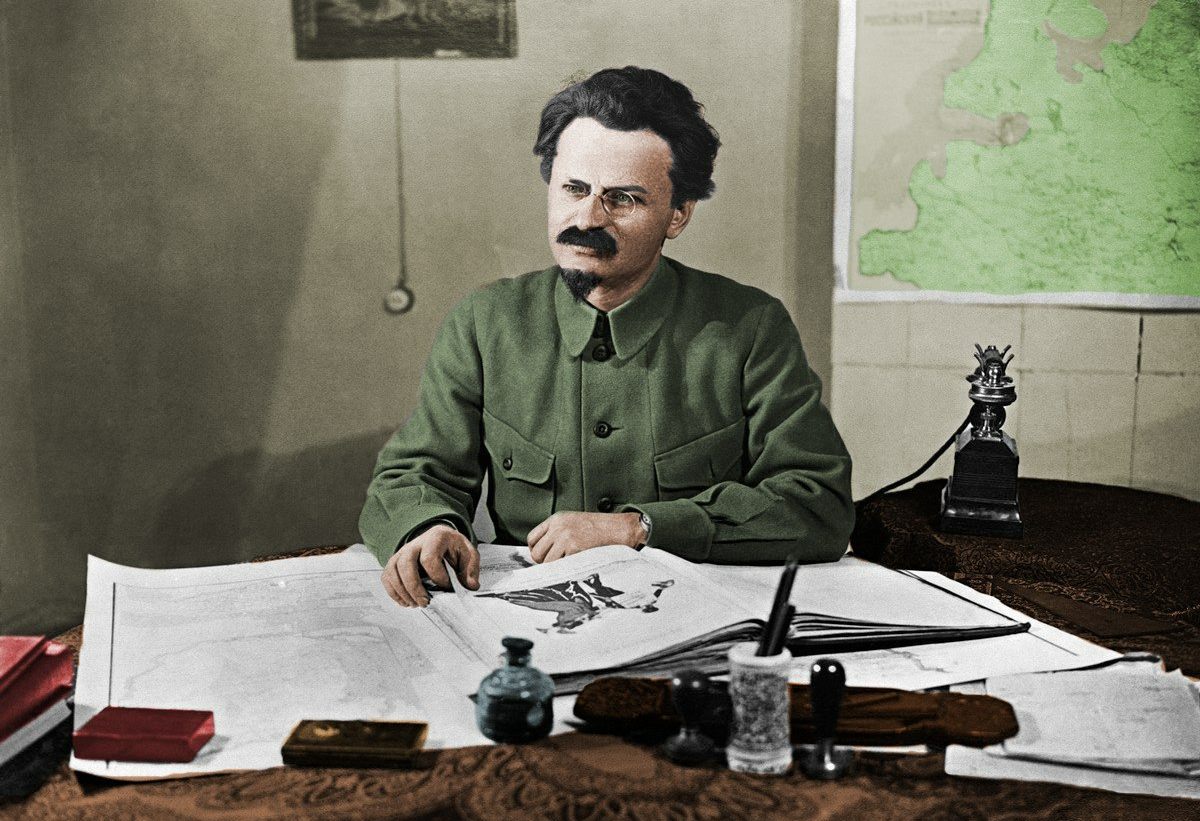

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( ‚Äď 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure in the

1905 Revolution,

October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

of 1917,

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, and the establishment of the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, from which he was exiled in 1929 before

his assassination in 1940. Trotsky and

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

were widely considered the two most prominent figures in the Soviet state from 1917 until

Lenin's death in 1924. Ideologically a

Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

and a

Leninist

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

, Trotsky's ideas inspired a school of Marxism known as

Trotskyism

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

.

Trotsky joined the

Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

in 1898, being arrested and exiled to

Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

for his activities. In 1902 he escaped to London, where he met Lenin. Trotsky initially sided with the

Mensheviks

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

against Lenin's

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

in the party's 1903 schism, but declared himself non-factional in 1904. During the 1905 Revolution, Trotsky was elected chairman of the

Saint Petersburg Soviet. He was again exiled to Siberia, but escaped in 1907 and lived abroad. After the

February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

of 1917, Trotsky joined the Bolsheviks and was elected chairman of the

Petrograd Soviet. He helped lead the October Revolution, and as the

People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs negotiated the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

, by which Russia withdrew from

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 ‚Äď 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. He served as

People's Commissar for Military Affairs from 1918 to 1925, during which he built the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

and led it to victory in the

civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. In 1922, Lenin formed a bloc with Trotsky against the growing

Soviet bureaucracy and proposed that he become a

deputy premier, but Trotsky declined. Beginning in 1923, Trotsky led the party's

Left Opposition

The Left Opposition () was a faction within the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) from 1923 to 1927 headed '' de facto'' by Leon Trotsky. It was formed by Trotsky to mount a struggle against the perceived bureaucratic degeneration within th ...

faction, which opposed the market concessions of the

New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

.

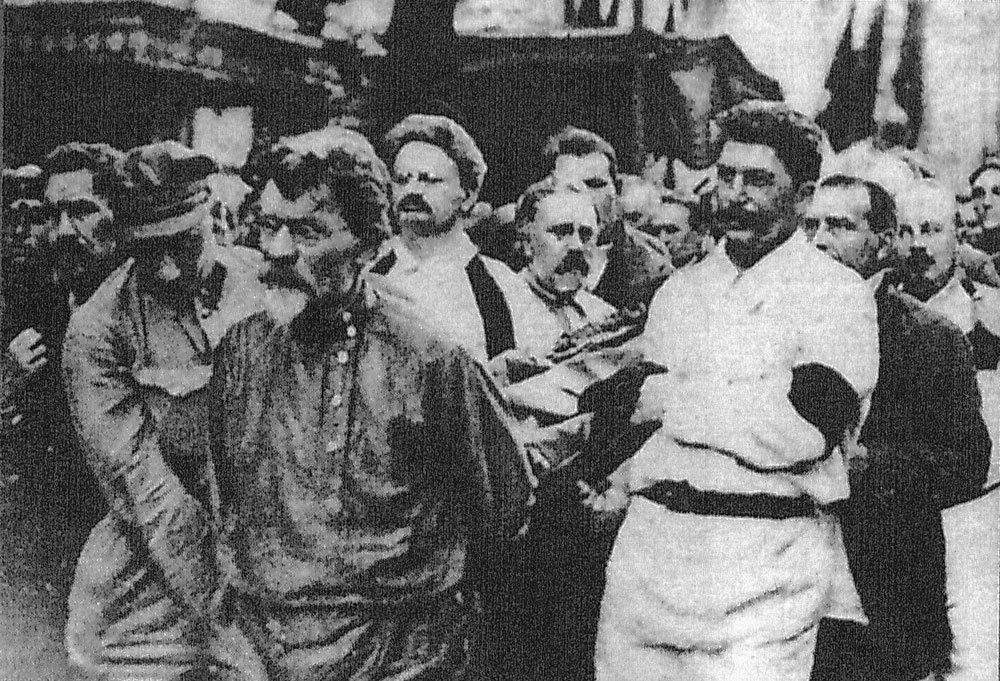

After Lenin's death in 1924, Trotsky emerged as a prominent critic of

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, who soon politically outmaneuvered him. Trotsky was expelled from the

Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

in 1926 and from the party in 1927, exiled to

Alma Ata in 1928, and deported in 1929. He lived in Turkey, France, and Norway before settling in Mexico in 1937. In exile, Trotsky wrote polemics against

Stalinism

Stalinism (, ) is the Totalitarianism, totalitarian means of governing and Marxism‚ÄďLeninism, Marxist‚ÄďLeninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from History of the Soviet Union (1927‚Äď1953), 1927 to 1953 by dictator Jose ...

, advocating

proletarian internationalism

Proletarian internationalism, sometimes referred to as international socialism, is the perception of all proletarian revolutions as being part of a single global class struggle rather than separate localized events. It is based on the theory th ...

against Stalin's theory of

socialism in one country. Trotsky's theory of

permanent revolution held that the revolution could only survive if spread to more advanced capitalist countries. In ''

The Revolution Betrayed

''The Revolution Betrayed: What is the Soviet Union and Where is it Going?'' () is a book published in 1936 by the former Soviet leader Leon Trotsky.

The book criticized the Soviet Union's actions and development following the death of Vladimir ...

'' (1936), he argued that the Soviet Union had become a "

degenerated workers' state", and in 1938 founded the

Fourth International

The Fourth International (FI) was a political international established in France in 1938 by Leon Trotsky and his supporters, having been expelled from the Soviet Union and the Communist International (also known as Comintern or the Third Inte ...

as an alternative to the

Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

. After being sentenced to death

in absentia

''In Absentia'' is the seventh studio album by British progressive rock band Porcupine Tree, first released on 24 September 2002. The album marked several changes for the band, with it being the first with new drummer Gavin Harrison and the f ...

at the

Moscow show trials in 1936, Trotsky

was assassinated in 1940 in Mexico City by Stalinist agent

Ramón Mercader.

Written out of official history under Stalin, Trotsky was one of the few of his rivals who was never

politically rehabilitated by later Soviet leaders. In the West, Trotsky emerged as a hero of the

anti-Stalinist left

The anti-Stalinist left encompasses various kinds of Left-wing politics, left-wing political movements that oppose Joseph Stalin, Stalinism, neo-Stalinism and the History of the Soviet Union (1927‚Äď1953), system of governance that Stalin impleme ...

for his defense of a more

democratic,

internationalist form of

socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

against Stalinist

totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public s ...

, and for his

intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

contributions to Marxism. While some of his wartime actions are controversial, such as his ideological defence of the

Red Terror

The Red Terror () was a campaign of political repression and Mass killing, executions in Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Russia which was carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police ...

and violent suppression of the

Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion () was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors, Marines, naval infantry, and civilians against the Bolsheviks, Bolshevik government in the Russian port city of Kronstadt. Located on Kotlin Island in the Gulf of Finland, ...

, scholarship ranks Trotsky's leadership of the Red Army highly among historical figures, and he is credited for his major involvement with the

military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

,

economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

,

cultural

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

and

political development of the Soviet Union.

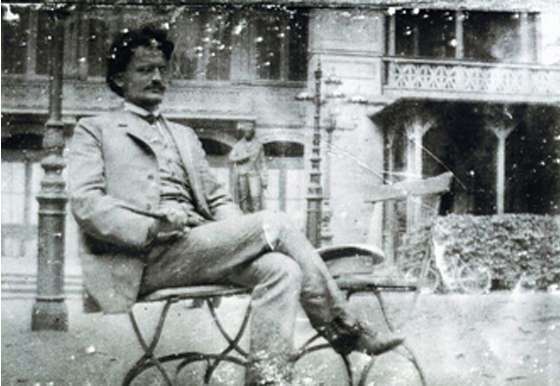

Childhood and family (1879‚Äď1895)

Lev Davidovich Bronstein was born on 7 November 1879 in Yanovka,

Kherson Governorate, Russian Empire (now

Bereslavka, Ukraine

Bereslavka (), formerly known as Yanovka () or Yanivka (), is a village in Kropyvnytskyi Raion, Kirovohrad Oblast, Ukraine. The village has a population of 139 (2001). Bereslavka was part of the Vasylivka village council and belongs to Ketrysani ...

), into a wealthy but illiterate

Jewish farming family.

He was the fifth child of David Leontyevich Bronstein (1847‚Äď1922), a Russified Jewish colonist, and Anna Lvovna (n√©e Zhivotovskaya, 1850‚Äď1910). Trotsky's younger sister,

Olga (1883‚Äď1941), also became a

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

and Soviet politician, and married fellow Bolshevik

Lev Kamenev

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. ( Rozenfeld; ‚Äď 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Kamenev was a leading figure in the early Soviet government and served as a Deputy Premier ...

.

Some authors, notably

Robert Service, claim Trotsky's childhood first name was the

Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

''Leiba''. However, Trotskyist writer

David North argues this is an assumption based on Trotsky's Jewish heritage, lacking documentary evidence, especially as Yiddish was not spoken by his family. Both North and historian

Walter Laqueur state Trotsky's childhood name was ''Lyova'', a standard Russian diminutive of ''Lev''. North likens the speculation to an undue emphasis on Trotsky's Jewish surname. The family spoke a mixture of Russian and Ukrainian (

Surzhyk), not Yiddish. Although Trotsky acquired good proficiency in French, English, and German, he stated in his autobiography ''

My Life'' that he was truly fluent only in Russian and Ukrainian.

Raymond Molinier noted Trotsky spoke French fluently.

When Trotsky was eight, his father sent him to

Odessa

ODESSA is an American codename (from the German language, German: ''Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen'', meaning: Organization of Former SS Members) coined in 1946 to cover Ratlines (World War II aftermath), Nazi underground escape-pl ...

for education. He enrolled in a Lutheran German-language school (St. Paul's Realschule), which admitted students of various faiths and became increasingly Russified during his time there due to the Imperial government's

Russification

Russification (), Russianisation or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians adopt Russian culture and Russian language either voluntarily or as a result of a deliberate state policy.

Russification was at times ...

policy.

Trotsky and his wife Natalia later registered their children as Lutheran, as Austrian law then required children to receive religious education "in the faith of their parents". Odessa, a bustling cosmopolitan port city, differed greatly from typical Russian cities and contributed to the development of young Trotsky's international outlook. He excelled academically, particularly in science and mathematics, and was a voracious reader, often disciplined for reading non-curriculum books during class.

Early political activities and life (1896‚Äď1917)

Revolutionary activity and imprisonment (1896‚Äď1898)

Trotsky became involved in revolutionary activities in 1896 after moving to the port town of

Nikolayev (now Mykolaiv) on the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

. Initially a ''

narodnik

The Narodniks were members of a movement of the Russian Empire intelligentsia in the 1860s and 1870s, some of whom became involved in revolutionary agitation against tsarism. Their ideology, known as Narodism, Narodnism or ,; , similar to the ...

'' (revolutionary

agrarian socialist populist

Populism is a contested concept used to refer to a variety of political stances that emphasize the idea of the " common people" and often position this group in opposition to a perceived elite. It is frequently associated with anti-establis ...

), he opposed

Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

but was converted by his future first wife,

Aleksandra Sokolovskaya. He graduated from high school with first-class honours the same year. His father had intended for him to become a

mechanical engineer

Mechanical may refer to:

Machine

* Machine (mechanical), a system of mechanisms that shape the actuator input to achieve a specific application of output forces and movement

* Mechanical calculator, a device used to perform the basic operations o ...

.

Trotsky briefly attended

Odessa University, studying

engineering

Engineering is the practice of using natural science, mathematics, and the engineering design process to Problem solving#Engineering, solve problems within technology, increase efficiency and productivity, and improve Systems engineering, s ...

and

mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

. A university colleague noted his exceptional mathematical talent. However, bored with his studies, he increasingly focused on

political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

and underground revolutionary activities. He dropped out in early 1897 to help organize the South Russian Workers' Union in Nikolayev. Using the name "Lvov",

[chapter XVII of his autobiography]

''My Life''

, Marxist Internet Archive he wrote and printed leaflets, distributed revolutionary pamphlets, and popularized socialist ideas among industrial workers and students.

In January 1898, over 200 union members, including Trotsky, were arrested. He spent the next two years in prison awaiting trial, first in Nikolayev, then

Kherson

Kherson (Ukrainian language, Ukrainian and , , ) is a port city in southern Ukraine that serves as the administrative centre of Kherson Oblast. Located by the Black Sea and on the Dnieper, Dnieper River, Kherson is the home to a major ship-bui ...

, Odessa, and finally Moscow. In Moscow, he encountered other revolutionaries, learned of Lenin, and read Lenin's ''

The Development of Capitalism in Russia''. Two months into his imprisonment, the first Congress of the

Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

(RSDLP) was held (1‚Äď3 March 1898). From then on, Trotsky identified as an RSDLP member.

First marriage and Siberian exile (1899‚Äď1902)

While imprisoned in Moscow in the summer of 1899, Trotsky married Aleksandra Sokolovskaya (1872‚Äď1938), a fellow Marxist, in a ceremony performed by a Jewish chaplain. In 1900, he was sentenced to four years of exile in

Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

. Due to their marriage, Trotsky and his wife were exiled together to

Ust-Kut and Verkholensk in the

Baikal region. They had two daughters,

Zinaida (1901‚Äď1933) and Nina (1902‚Äď1928), both born in Siberia.

In Siberia, Trotsky studied

history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

,

philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

,

economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

,

sociology

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociol ...

, and the works of

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 ‚Äď 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

to solidify his political stance. He became aware of internal party differences, particularly the debate between "

economists

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this field there are ...

", who focused on workers' economic improvements, and those who prioritized overthrowing the monarchy through a disciplined revolutionary party. The latter position was advocated by the London-based newspaper ''

Iskra'' (''The Spark''), founded in 1900. Trotsky quickly sided with ''Iskra'' and began writing for it.

In the summer of 1902, urged by his wife, Trotsky escaped from Siberia hidden in a load of hay. Aleksandra later escaped with their daughters. Both daughters married and had children but died before their parents. Nina Nevelson died from

tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

in 1928. Zinaida Volkova, also suffering from tuberculosis and

depression, followed her father into exile in Berlin but committed suicide in 1933. Aleksandra disappeared in 1935 during Stalin's

Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

and was murdered by Soviet forces in 1938.

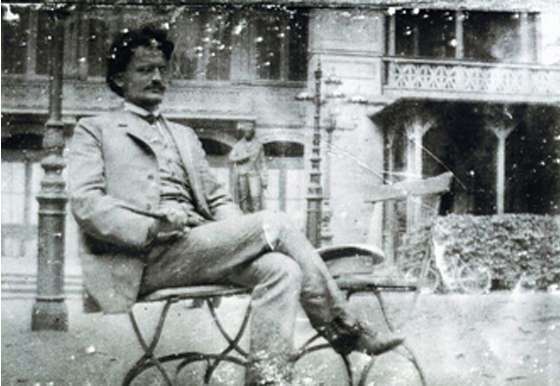

First emigration and second marriage (1902‚Äď1903)

Until this point, Trotsky had used his birth name, Lev (Leon) Bronstein. He adopted the surname "Trotsky"‚ÄĒreportedly the name of a jailer in the Odessa prison where he had been held‚ÄĒwhich he used for the rest of his life. This became his primary revolutionary pseudonym. After escaping Siberia, Trotsky moved to London, joining

Georgi Plekhanov

Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov ( rus, –ď–Ķ–ĺ—Ä–≥–ł–Ļ –í–į–Ľ–Ķ–Ĺ—ā–ł–Ĺ–ĺ–≤–ł—á –ü–Ľ–Ķ—Ö–į–Ĺ–ĺ–≤, p=…° ≤…™ňąor…° ≤…™j v…ôl ≤…™n ≤ňąt ≤in…ôv ≤…™t…ē pl ≤…™ňąxan…ôf, a=Ru-Georgi Plekhanov-JermyRei.ogg; ‚Äď 30 May 1918) was a Russian revolutionary, ...

, Vladimir Lenin,

Julius Martov, and other editors of ''Iskra''. Writing under the pen name ''Pero'' ("quill" or "pen"), Trotsky soon became one of the paper's leading writers.

The six editors of ''Iskra'' were split between an "old guard" led by Plekhanov and a "new guard" led by Lenin and Martov. Lenin, seeking a majority against Plekhanov, expected the 23-year-old Trotsky to side with the new guard. In March 1903, Lenin proposed Trotsky's co-option to the editorial board:

Due to Plekhanov's opposition, Trotsky did not become a full board member but participated in an advisory capacity, earning Plekhanov's animosity.

In late 1902, Trotsky met

Natalia Sedova (1882‚Äď1962), who soon became his companion. They married in 1903 and remained together until his death. They had two sons,

Lev Sedov (1906‚Äď1938) and

Sergei Sedov (1908‚Äď1937), both of whom predeceased their parents. Trotsky later explained that, for "citizenship" requirements after the 1917 revolution, he "took on the name of my wife" so his sons would not have to change their name. However, he never publicly or privately used the name "Sedov". Natalia Sedova sometimes signed her name "Sedova-Trotskaya".

Split with Lenin (1903‚Äď1904)

In August 1903, ''Iskra'' convened the RSDLP's

Second Congress in London. Trotsky attended with other ''Iskra'' editors. After defeating the "economist" delegates, the congress addressed the

Bund's desire for autonomy within the party.

[Trotsky, Leon. ''My life: an attempt at an autobiography''. Courier Corporation, 2007.]

Subsequently, the pro-Iskra delegates unexpectedly split. The initial dispute was organisational: Lenin and his supporters (the Bolsheviks) advocated for a smaller, highly organized party of committed members, while Martov and his supporters (the

Mensheviks

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

) favoured a larger, less disciplined party that included sympathizers. Trotsky and most ''Iskra'' editors supported Martov, while Plekhanov backed Lenin. During 1903‚Äď1904, allegiances shifted; Trotsky left the Mensheviks in September 1904, disagreeing with their insistence on an alliance with Russian liberals and their opposition to reconciliation with Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

From 1904 to 1917, Trotsky described himself as a "non-factional social democrat". He attempted to reconcile party factions, leading to clashes with Lenin and others. Trotsky later admitted he was wrong to oppose Lenin on party organization. During this period, he developed his theory of

permanent revolution and worked closely with

Alexander Parvus (1904‚Äď1907). During their split, Lenin referred to Trotsky as "Judas" (''Iudushka'', after a character in

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin's novel ''

The Golovlyov Family''), a "scoundrel", and a "swine".

1905 revolution and trial (1905‚Äď1906)

Anti-government unrest culminated in

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

on 3 January 1905 (O.S.), when a strike began at the

Putilov Works. This escalated into a general strike, with 140,000 strikers in Saint Petersburg by 7 January 1905.

On Sunday, 9 January 1905, Father

Georgi Gapon led a procession to the

Winter Palace

The Winter Palace is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the House of Romanov, previous emperors, from 1732 to 1917. The palace and its precincts now house the Hermitage Museum. The floor area is 233,345 square ...

, ostensibly to petition the Tsar. Accounts differ, but the Palace Guard fired on the demonstration, resulting in numerous deaths and injuries. This event, known as

Bloody Sunday, intensified revolutionary fervour. Gapon's own biography suggests a degree of provocation by radicals within the crowd, a claim later echoed by some police records.

Following Bloody Sunday, Trotsky secretly returned to Russia in February 1905 via

Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

. He wrote for an underground press in Kiev before moving to Saint Petersburg. There, he worked with Bolsheviks like

Leonid Krasin

Leonid Borisovich Krasin (; ‚Äď 24 November 1926) was a Russians, Russian Soviet Union, Soviet politician, engineer, social entrepreneur, Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet diplomat. In 1924 he became the first List of ambassadors of Russia to ...

and the local Menshevik committee, pushing the latter in a more radical direction. A police raid in May forced him to flee to rural

Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

, where he further developed his theory of permanent revolution.

On 19 September 1905, typesetters at

Ivan Sytin's Moscow printing house struck for shorter hours and higher pay. By 24 September, 50 other Moscow printing shops joined. On 2 October, Saint Petersburg typesetters struck in solidarity. On 7 October, railway workers of the

Moscow‚ÄďKazan Railway also struck. Amidst this turmoil, Trotsky returned to Saint Petersburg on 15 October. He addressed the Saint Petersburg Soviet (Council) of Workers' Deputies at the Technological Institute, with an estimated 200,000 people gathered outside‚ÄĒabout half the city's workers.

After his return, Trotsky and

Parvus took over the newspaper ''Russian Gazette,'' increasing its circulation to 500,000. Trotsky also co-founded "Nachalo" ("The Beginning") with Parvus, Julius Martov, and other Mensheviks, which became a successful newspaper during the 1905 revolutionary climate in Saint Petersburg.

Before Trotsky's return, Mensheviks had independently conceived of an elected, non-party revolutionary body representing the capital's workers: the first

Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. By Trotsky's arrival, the

Saint Petersburg Soviet was functioning, headed by

Khrustalyev-Nosar (Georgy Nosar, alias Pyotr Khrustalyov), a lawyer chosen as a compromise figure. Khrustalyev-Nosar became popular and was the Soviet's public face. Trotsky joined the Soviet as "Yanovsky" (after his birthplace) and was elected vice-chairman. He performed much of the practical work and, after Khrustalyev-Nosar's arrest on 26 November 1905, became its chairman. On 2 December, the Soviet issued a proclamation on Tsarist government debts:

The following day, 3 December 1905, government troops surrounded the Soviet, and its deputies were arrested. Trotsky and other leaders were tried in 1906 for supporting an armed rebellion. On 4 October 1906, he was convicted and sentenced to internal exile in Siberia.

Second emigration (1907‚Äď1914)

En route to exile in

Obdorsk, Siberia, in January 1907, Trotsky escaped at

Berezov and made his way to London. He attended the

5th Congress of the RSDLP. In October, he moved to

Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, Austria-Hungary. For the next seven years, he participated in the activities of the

Austrian Social Democratic Party and occasionally the

German Social Democratic Party.

In Vienna, he became close to

Adolph Joffe, his friend for the next 20 years, who introduced him to

psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek language, Greek: and is a set of theories and techniques of research to discover unconscious mind, unconscious processes and their influence on conscious mind, conscious thought, emotion and behaviour. Based on The Inte ...

.

In October 1908, Trotsky joined the editorial staff of ''

Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, –ü—Ä–į–≤–ī–į, p=ňąpravd…ô, a=Ru-–Ņ—Ä–į–≤–ī–į.ogg, 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most in ...

'' ("Truth"), a bi-weekly, Russian-language social democratic paper for Russian workers, co-editing it with Adolph Joffe and

Matvey Skobelev. It was smuggled into Russia. The paper appeared irregularly, with only five issues in its first year. Avoiding factional politics, it proved popular with Russian industrial workers. After the 1905‚Äď1907 revolution's failure, both Bolsheviks and Mensheviks experienced multiple splits. Funding for ''Pravda'' was scarce. Trotsky sought financial backing from the RSDLP

Central Committee throughout 1909.

In 1910, a Bolshevik majority controlled the Central Committee. Lenin agreed to finance ''Pravda'' but required a Bolshevik co-editor. When various factions tried to reunite at the January 1910 RSDLP Central Committee meeting in Paris (over Lenin's objections), Trotsky's ''Pravda'' was made a party-financed 'central organ'.

Lev Kamenev

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. ( Rozenfeld; ‚Äď 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Kamenev was a leading figure in the early Soviet government and served as a Deputy Premier ...

, Trotsky's brother-in-law, joined the editorial board from the Bolsheviks. However, unification attempts failed by August 1910. Kamenev resigned amid mutual recriminations. Trotsky continued publishing ''Pravda'' for another two years until it folded in April 1912.

The Bolsheviks launched a new workers' newspaper in Saint Petersburg on 22 April 1912, also named ''Pravda''. Trotsky, upset by what he saw as the usurpation of his newspaper's name, wrote a bitter letter to

Nikolay Chkheidze, a Menshevik leader, in April 1913, denouncing Lenin and the Bolsheviks. Though he quickly moved past the disagreement, the letter was intercepted by the

Okhrana

The Department for the Protection of Public Safety and Order (), usually called the Guard Department () and commonly abbreviated in modern English sources as the Okhrana ( rus , –ě—Ö—Ä–į–Ĺ–į, p=…źňąxran…ô, a=Ru-–ĺ—Ö—Ä–į–Ĺ–į.ogg, t= The Guard) w ...

(secret police) and archived. After Lenin's death in 1924, Trotsky's opponents within the Communist Party publicized the letter to portray him as Lenin's enemy.

The 1910s were a period of heightened tension within the RSDLP. A major disagreement between Trotsky and the Mensheviks on one side, and Lenin on the other, concerned "expropriations"‚ÄĒarmed robberies of banks and businesses by Bolshevik groups to fund the Party. These actions, banned by the 5th Congress, were continued by Bolsheviks.

In January 1912, most of the Bolshevik faction, led by Lenin, held a conference in

Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

, broke away from the RSDLP, and formed the

Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks). In response, Trotsky organized a "unification" conference of social democratic factions in Vienna in August 1912 (the "August Bloc") to reunite Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, but this attempt was largely unsuccessful.

In Vienna, Trotsky published articles in radical Russian and Ukrainian newspapers like ''Kievskaya Mysl,'' using pseudonyms such as "Antid Oto", a name chosen randomly from an Italian dictionary. Trotsky joked he "wanted to inject the Marxist antidote into the legitimate newspapers". In September 1912, ''Kievskaya Mysl'' sent him to the Balkans as its war correspondent, where he covered the two

Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Gl√ľcksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

for the next year. There, Trotsky chronicled

ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

carried out by the Serbian army

against Albanian civilians. He became a close friend of

Christian Rakovsky

Christian Georgiyevich Rakovsky ( ‚Äď September 11, 1941), Bulgarian name Krastyo Georgiev Rakovski, born Krastyo Georgiev Stanchov, was a Bulgarian-born socialist Professional revolutionaries, revolutionary, a Bolshevik politician and Soviet Un ...

, later a leading Soviet politician and Trotsky's ally. On 3 August 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, with

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

fighting the Russian Empire, Trotsky was forced to flee Vienna for neutral Switzerland to avoid arrest as a Russian

émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social exile or self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French verb ''émigrer'' meaning "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Hugueno ...

.

World War I (1914‚Äď1917)

World War I caused a sudden realignment within the RSDLP and other European social democratic parties over issues of war, revolution, pacifism, and internationalism. The RSDLP split into "defeatists" and "defencists". Lenin, Trotsky, and Martov advocated various internationalist anti-war positions, viewing defeat for their own country's ruling class as a "lesser evil" and opposing all imperialists in the war. "Defencists" like Plekhanov supported the Russian government to some extent. Trotsky's former colleague Parvus, now a defencist, sided so strongly against Russia that he wished for a German victory. In Switzerland, Trotsky briefly worked with the

Swiss Socialist Party, prompting it to adopt an internationalist resolution. He wrote ''The War and the International,'' opposing the war and the pro-war stance of European social democratic parties, especially the German party.

As a war correspondent for ''Kievskaya Mysl'', Trotsky moved to France on 19 November 1914. In January 1915 in Paris, he began editing ''

Nashe Slovo'' ("Our Word"), an internationalist socialist newspaper, initially with Martov (who soon resigned as the paper moved left). He adopted the slogan "peace without indemnities or annexations, peace without conquerors or conquered." Lenin advocated Russia's defeat and demanded a complete break with the

Second International

The Second International, also called the Socialist International, was a political international of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties and Trade union, trade unions which existed from 1889 to 1916. It included representatives from mo ...

.

Trotsky attended the

Zimmerwald Conference of anti-war socialists in September 1915, advocating a middle course between those like Martov, who would stay in the Second International, and those like Lenin, who would break from it and form a

Third International

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internation ...

. The conference adopted Trotsky's proposed middle line. Lenin, initially opposed, eventually voted for Trotsky's resolution to avoid a split among anti-war socialists.

In September 1916, Trotsky was deported from France to Spain for his anti-war activities. Spanish authorities, not wanting him, deported him to the United States on 25 December 1916. He arrived in New York City on 13 January 1917, staying for over two months at 1522 Vyse Avenue in

The Bronx

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

. In New York, he wrote articles for the local

Russian-language socialist newspaper ''

Novy Mir

''Novy Mir'' (, ) is a Russian-language monthly literary magazine.

History

''Novy Mir'' has been published in Moscow since January 1925. It was supposed to be modelled on the popular pre-Soviet literary magazine ''Mir Bozhy'' ("God's World"), w ...

'' and, in translation, for the Yiddish-language daily

''Der Forverts'' ("Forward"). He also gave speeches to Russian émigrés.

Trotsky was in New York City when the

February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

of 1917 led to the abdication of

Tsar Nicholas II. He left New York aboard SS ''Kristianiafjord'' on 27 March 1917, but his ship was intercepted by the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

at

Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and most populous municipality of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the most populous municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of 2024, it is estimated that the population of the H ...

. Trotsky was arrested and detained for a month at the

Amherst Internment Camp in

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

. In the camp, he befriended workers and sailors among his fellow inmates, describing his month there as "one continual mass meeting".

[''Leon Trotsky: My Life ‚Äď In a Concentration Camp''](_blank)

, ns1758.ca; accessed 31 January 2018. His speeches and agitation angered German inmates, who complained to the camp commander, Colonel Morris, about Trotsky's "anti-patriotic" attitude.

Morris subsequently forbade Trotsky from making public speeches, leading to 530 prisoners protesting and signing a petition against the decision.

In Russia, after initial hesitation and under pressure from workers' and peasants' Soviets, Foreign Minister

Pavel Milyukov demanded Trotsky's release as a Russian citizen. The British government freed him on 29 April 1917.

He reached Russia on 17 May 1917. Upon his return, Trotsky largely agreed with the Bolshevik position but did not immediately join them. Russian social democrats were split into at least six groups, and the Bolsheviks awaited the next party Congress to decide on mergers. Trotsky temporarily joined the

Mezhraiontsy, a regional social democratic organization in

Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

, becoming one of its leaders. At the First

Congress of Soviets

The Congress of Soviets was the supreme governing body of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and several other Soviet republics and national autonomies in the Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union from 1917 to 1936 and a somewhat simil ...

in June, he was elected a member of the first

All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK) from the Mezhraiontsy faction.

After an unsuccessful pro-Bolshevik uprising in Petrograd in July (the

July Days), Trotsky was arrested on 7 August 1917. He was released 40 days later following the failed counter-revolutionary

uprising by Lavr Kornilov. After the Bolsheviks gained a majority in the

Petrograd Soviet, Trotsky was elected its chairman on .

He sided with Lenin against

Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev (born Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky; ‚Äď 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Zinoviev was a close associate of Vladimir Lenin prior to ...

and

Lev Kamenev

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. ( Rozenfeld; ‚Äď 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Kamenev was a leading figure in the early Soviet government and served as a Deputy Premier ...

when the Bolshevik Central Committee discussed staging an armed uprising, and he led the efforts to overthrow the

Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government was a provisional government of the Russian Empire and Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately after the abdication of Nicholas II on 2 March, O.S. New_Style.html" ;"title="5 ...

headed by socialist

Aleksandr Kerensky.

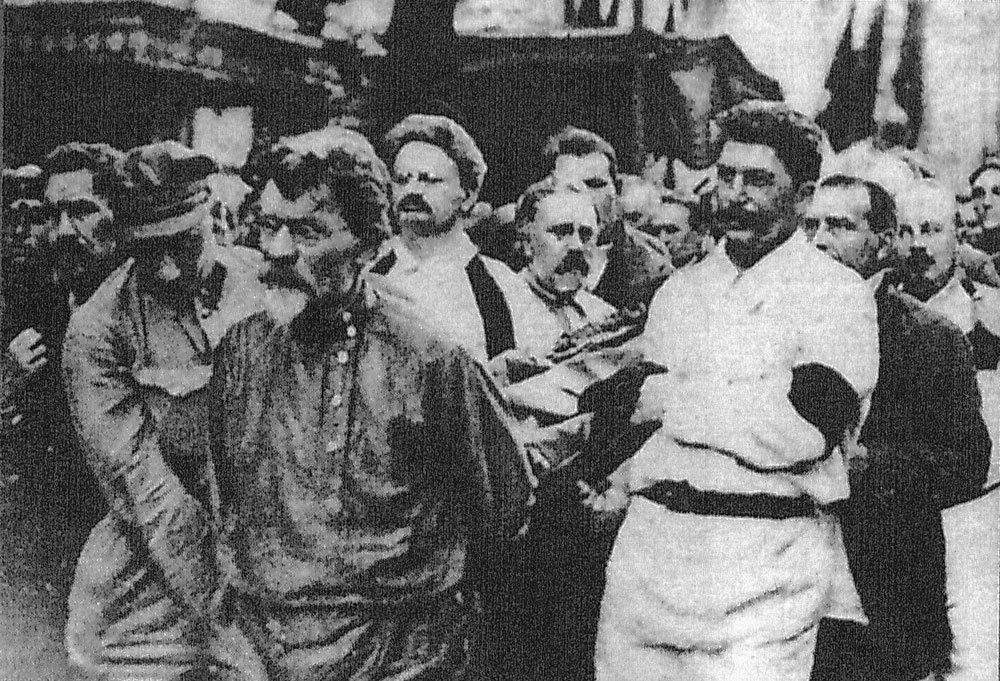

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

wrote the following summary of Trotsky's role in 1917 in ''Pravda'' on 6 November 1918:

[In One And The Same Issue](_blank)

New International, Vol. 2 No. 6, October 1935, p. 208.

Although this passage was quoted in Stalin's book ''The October Revolution'' (1934),

it was expunged from Stalin's ''Works'' (1949).

After the success of the

October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

on 7‚Äď8 November 1917, Trotsky led efforts to repel a

counter-attack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in " war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically seek ...

by

Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic‚ÄďCaspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

under General

Pyotr Krasnov and other troops loyal to the overthrown Provisional Government at

Gatchina. Allied with Lenin, he defeated attempts by other Bolshevik Central Committee members (Zinoviev, Kamenev,

Rykov, etc.) to share power with other moderate socialist parties. Trotsky advocated for a predominantly Bolshevik government and was reluctant to recall Mensheviks as partners after their voluntary withdrawal from the Congress of Soviets. However, he released several socialist ministers from prison. Neither Trotsky nor his colleagues in 1917 initially wished to suppress these parties entirely; the Bolsheviks reserved vacant seats in the Soviets and the

Central Executive Committee for these parties in proportion to their vote share at the Congress. Concurrently, prominent

Left Socialist Revolutionaries

The Party of Left Socialist-Revolutionaries-Internationalists () was a revolutionary socialist political party formed during the Russian Revolution.

In 1917, the Socialist Revolutionary Party split between those who supported the Russian Prov ...

assumed positions in Lenin's government, leading commissariats such as agriculture (

Andrei Kolegayev), property (

Vladimir Karelin), justice (

Isaac Steinberg), posts and telegraphs (

Prosh Proshian), and local government (Vladimir Trutovsky). According to Deutscher, Menshevik and Social Revolutionary demands for a coalition government included disarming Bolshevik detachments and excluding Lenin and Trotsky, which was unacceptable even to moderate Bolshevik negotiators like Kamenev and

Sokolnikov. By the end of 1917, Trotsky was unquestionably the second most powerful man in the Bolshevik Party after Lenin, overshadowing Zinoviev, who had been Lenin's top lieutenant for the previous decade.

Russian Revolution and aftermath

Commissar for Foreign Affairs and Brest-Litovsk (1917‚Äď1918)

After the Bolsheviks seized power, Trotsky became

People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs. He published the

secret treaties previously signed by the

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

, which detailed plans for post-war reallocation of colonies and redrawing state borders, including the

Sykes‚ÄďPicot Agreement

The Sykes‚ÄďPicot Agreement () was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from Russia and Italy, to define their mutually agreed spheres of influence and control in an eventual partition of the Ottoman Empire.

T ...

. This revelation on 23 November 1917 caused considerable embarrassment to Britain and France.

Brest-Litovsk

In preparation for peace talks with the Central Powers, Trotsky appointed his old friend Adolph Joffe to represent the Bolsheviks. When the Soviet delegation learned that Germany and Austria-Hungary planned to annex Polish territory, establish a rump Polish state, and turn the Baltic provinces into client states ruled by German princes, the talks were recessed for 12 days. The Soviets hoped that, given time, their allies would join the negotiations or that the Western European proletariat would revolt; thus, prolonging negotiations was their best strategy. As Trotsky wrote, "To delay negotiations, there must be someone to do the delaying". Consequently, Trotsky replaced Joffe as head of the Soviet delegation at

Brest-Litovsk from 22 December 1917 to 10 February 1918.

The Soviet government was divided.

Left Communists, led by

Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (; rus, –Ě–ł–ļ–ĺ–Ľ–į–Ļ –ė–≤–į–Ĺ–ĺ–≤–ł—á –Ď—É—Ö–į—Ä–ł–Ĺ, p=n ≤…™k…źňąlaj …™ňąvan…ôv ≤…™d Ď b äňąxar ≤…™n; ‚Äď 15 March 1938) was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and Marxist theorist. A prominent Bolshevik ...

, believed no peace was possible between a Soviet republic and a capitalist empire, advocating a revolutionary war for a pan-European Soviet republic.

They cited early Red Army successes against Polish forces,

White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

forces, and

Ukrainian forces as proof of its capability, especially with propaganda and

asymmetrical warfare

Asymmetric warfare (or asymmetric engagement) is a type of war between belligerents whose relative military power, strategy or tactics differ significantly. This type of warfare often, but not necessarily, involves Insurgency, insurgents, terro ...

.

They were willing to negotiate to expose German imperial ambitions but opposed signing any peace treaty, favouring a revolutionary war if faced with a German ultimatum. This view was shared by the

Left Socialist Revolutionaries

The Party of Left Socialist-Revolutionaries-Internationalists () was a revolutionary socialist political party formed during the Russian Revolution.

In 1917, the Socialist Revolutionary Party split between those who supported the Russian Prov ...

, then junior partners in the coalition government.

[Left Socialist-Revolutionaries (Left SRs)](_blank)

; Glossary of organizations on Marxists.org

Lenin, initially hopeful for a swift European revolution, concluded that the German Imperial government remained strong and that, without a robust Russian military, armed conflict would lead to the Soviet government's collapse. He agreed a pan-European revolution was the ultimate solution but prioritized Bolshevik survival. From January 1918, he advocated signing a separate peace treaty if faced with a German ultimatum. Trotsky's position was between these factions. He acknowledged the old Russian army's inability to fight:

However, he agreed with the Left Communists that a separate peace treaty would be a severe morale and material blow, negating recent successes, reviving suspicions of Bolshevik-German collusion, and fuelling internal resistance. He argued that a German ultimatum should be refused, which might trigger an uprising in Germany or inspire German soldiers to disobey orders if an offensive was a naked land grab. Trotsky wrote in 1925:

In a letter to Lenin before 18 January 1918, Trotsky outlined his "no war, no peace" policy: announce war termination and demobilization without signing a treaty, placing the fate of Poland, Lithuania, and Courland on the German working people. He believed Germany would find it difficult to attack due to internal conditions and opposition from various German political factions.

Lenin initially responded on 18 January: "Stalin has just arrived; we will look into the matter with him and let you have a joint answer right away," and "please adjourn proceedings and leave for Petrograd. Send a reply; I will wait. Lenin, Stalin." Trotsky, sensing disagreement, returned to Petrograd. During their debate, Lenin concluded: "In any case, I stand for the immediate signing of peace; it is safer."

On 10 February 1918, Trotsky and the Russian delegation withdrew from peace talks, declaring an end to the war on Russia's side without signing a peace treaty. Privately, Trotsky had expressed willingness to relent to peace terms if Germany resumed its offensive, albeit with moral dissent. Germany resumed

military operations on 18 February. The Red Army detachments proved no match for the German army. On the evening of 18 February, Trotsky and his supporters abstained in a Central Committee vote, and Lenin's proposal to accept German terms was approved 7‚Äď4. The Soviet government sent a

radiogram accepting the final Brest-Litovsk terms.

Germany did not respond for three days, continuing its offensive. The response on 21 February contained such harsh terms that even Lenin briefly considered fighting. However, the Central Committee again voted 7‚Äď4 on 23 February to accept. The

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

was signed on 3 March and ratified on 15 March 1918. Closely associated with the previous "no war, no peace" policy, Trotsky resigned as Commissar for Foreign Affairs.

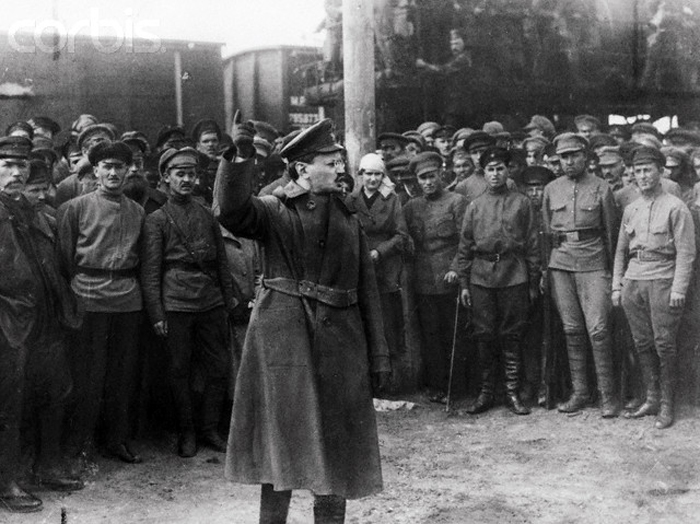

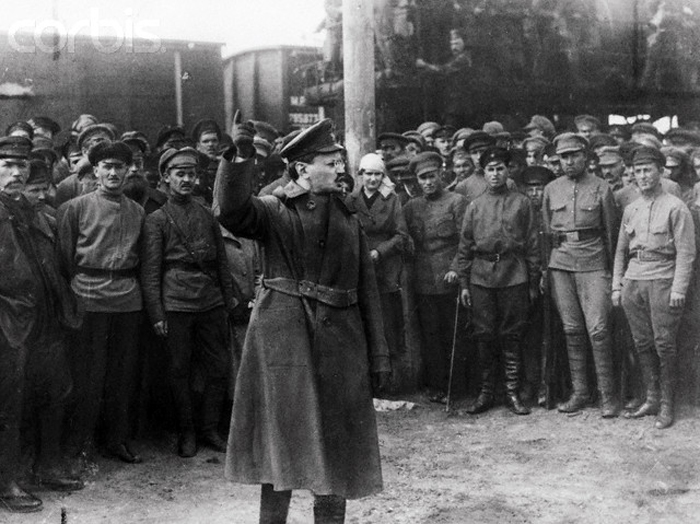

Head of the Red Army (spring 1918)

On 13 March 1918, Trotsky's resignation as Foreign Affairs Commissar was accepted. He was appointed People's Commissar of Army and Navy Affairs, replacing Podvoisky, and chairman of the Supreme Military Council. The post of commander-in-chief was abolished, giving Trotsky full control of the Red Army, responsible only to the Communist Party leadership, whose Left Socialist Revolutionary allies had left the government over the treaty.

The entire Bolshevik Red Army leadership, including former Defence Commissar

Nikolai Podvoisky and commander-in-chief

Nikolai Krylenko

Nikolai Vasilyevich Krylenko (, ; 2 May 1885 – 29 July 1938) was an Old Bolshevik and Soviet politician, military commander, and jurist. Krylenko served in a variety of posts in the Soviet law, Soviet legal system, rising to become Minis ...

, vigorously protested Trotsky's appointment and eventually resigned. They believed the Red Army should consist only of dedicated revolutionaries, rely on propaganda and force, and have elected officers. They viewed former imperial officers as potential traitors. Their views remained popular, and their supporters, including Podvoisky (who became one of Trotsky's deputies), were a constant source of opposition. Discontent with Trotsky's policies of strict discipline,

conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

, and reliance on supervised non-Communist military experts led to the

Military Opposition, active within the Party in late 1918‚Äď1919.

Civil War (1918‚Äď1920)

1918

The military situation tested Trotsky's organizational skills. In May‚ÄďJune 1918, the

Czechoslovak Legions revolted, leading to the loss of most of Russia's territory, increasingly organized resistance from anti-Communist forces (the

White Army), and widespread defections by military experts Trotsky relied on.

Trotsky and the government responded with a full

mobilization

Mobilization (alternatively spelled as mobilisation) is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the ...

, increasing the Red Army from under 300,000 in May 1918 to one million by October, and introducing

political commissars to ensure loyalty of military experts (mostly former Imperial officers) and co-sign their orders. Trotsky viewed the Red Army's organization as built on October Revolution ideals. He later wrote:

A controversial measure was hostage-taking of relatives of ex-Tsarist officials in the Red Army to prevent

defection

In politics, a defector is a person who gives up allegiance to one state in exchange for allegiance to another, changing sides in a way which is considered illegitimate by the first state. More broadly, defection involves abandoning a person, ca ...

or betrayal. Service noted this practice was used by both Red and White armies. Trotsky later defended this, arguing no families of betraying ex-officials were executed and that such draconian measures, if adopted earlier, would have reduced overall casualties. Deutscher highlights Trotsky's preference for exchanging hostages over execution, recounting General

Pyotr Krasnov's release on parole in 1918, only for Krasnov to take up arms again shortly thereafter.

= Red Terror

=

The

Red Terror

The Red Terror () was a campaign of political repression and Mass killing, executions in Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Russia which was carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police ...

was enacted following

assassination attempts on Lenin and Trotsky, and the assassinations of Petrograd

Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, –í—Ā–Ķ—Ä–ĺ—Ā—Ā–ł–Ļ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź —á—Ä–Ķ–∑–≤—č—á–į–Ļ–Ĺ–į—Ź –ļ–ĺ–ľ–ł—Ā—Ā–ł—Ź, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fs ≤…™r…źňąs ≤ijsk…ôj…ô t…ēr ≤…™zv…®ňąt…ē√¶jn…ôj…ô k…źňąm ≤is ≤…™j…ô, links=yes), ...

leader

Moisei Uritsky and party editor

V. Volodarsky.

The French

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the French First Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and Capital punishment in France, nu ...

is seen as an influence.

[Wilde, Robert. 2019 February 20.]

The Red Terror

" ''ThoughtCo''. Retrieved 24 March 2021. The decision was also driven by early

White Army massacres of "Red" prisoners in 1917,

Allied intervention, and massacres of Reds during the

Finnish Civil War

The Finnish Civil War was a civil war in Finland in 1918 fought for the leadership and control of the country between Whites (Finland), White Finland and the Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic (Red Finland) during the country's transition fr ...

(10,000‚Äď20,000 workers killed by

Finnish Whites)."

In ''

Terrorism and Communism'', Trotsky argued the terror in Russia began with the

White Terror under White Guard forces, to which the Bolsheviks responded with the Red Terror.

Felix Dzerzhinsky, director of the

Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, –í—Ā–Ķ—Ä–ĺ—Ā—Ā–ł–Ļ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź —á—Ä–Ķ–∑–≤—č—á–į–Ļ–Ĺ–į—Ź –ļ–ĺ–ľ–ł—Ā—Ā–ł—Ź, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fs ≤…™r…źňąs ≤ijsk…ôj…ô t…ēr ≤…™zv…®ňąt…ē√¶jn…ôj…ô k…źňąm ≤is ≤…™j…ô, links=yes), ...

(predecessor to the KGB), was tasked with rooting out

counter-revolutionary

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution has occurred, in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "c ...

threats.

From early 1918, Bolsheviks began eliminating opposition, including

anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

s.

On 11 August 1918, Lenin

telegraphed orders "to introduce mass terror" in

Nizhny Novgorod

Nizhny Novgorod ( ; rus, links=no, –Ě–ł–∂–Ĺ–ł–Ļ –Ě–ĺ–≤–≥–ĺ—Ä–ĺ–ī, a=Ru-Nizhny Novgorod.ogg, p=ňąn ≤i źn ≤…™j ňąnov…°…ôr…ôt, t=Lower Newtown; colloquially shortened to Nizhny) is a city and the administrative centre of Nizhny Novgorod Oblast an ...

and to "crush" landowners resisting grain requisitioning.

[ ¬ę–ö—Ä–į—Ā–Ĺ—č–Ļ –ł –Ď–Ķ–Ľ—č–Ļ —ā–Ķ—Ä—Ä–ĺ—Ä –≤ –†–ĺ—Ā—Ā–ł–ł –≤ 1917‚ÄĒ1922 –≥–ĺ–ī–į—Ö¬Ľ .]

On 30 August,

Fanny Kaplan, a

Socialist Revolutionary, unsuccessfully

attempted to assassinate Lenin.

In September, Trotsky rushed from the eastern front to Moscow; Stalin remained in

Tsaritsyn. Kaplan cited growing Bolshevik authoritarianism. These events persuaded the government to heed Dzerzhinsky's calls for greater terror. The Red Terror officially began thereafter, between 17 and 30 August 1918.

Trotsky wrote:

= Desertions

=

Trotsky appealed politically to

deserters

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or Military base, post without permission (a Pass (military), pass, Shore leave, liberty or Leave (U.S. military), leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with u ...

, arousing them with revolutionary ideas.

The Red Army first used punitive

barrier troops in summer/autumn 1918 on the

Eastern Front. Trotsky authorized

Mikhail Tukhachevsky

Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky ( rus, –ú–ł—Ö–į–ł–Ľ –Ě–ł–ļ–ĺ–Ľ–į–Ķ–≤–ł—á –Ę—É—Ö–į—á–Ķ–≤—Ā–ļ–ł–Ļ, Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevskiy, p=t äx…źňąt…ēefsk ≤…™j; ‚Äď 12 June 1937), nicknamed the Red Napoleon, was a Soviet general who was prominen ...

, commander of the

1st Army, to station blocking detachments behind unreliable infantry regiments, with orders to shoot if front-line troops deserted or retreated without permission. These troops comprised personnel from

Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, –í—Ā–Ķ—Ä–ĺ—Ā—Ā–ł–Ļ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź —á—Ä–Ķ–∑–≤—č—á–į–Ļ–Ĺ–į—Ź –ļ–ĺ–ľ–ł—Ā—Ā–ł—Ź, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fs ≤…™r…źňąs ≤ijsk…ôj…ô t…ēr ≤…™zv…®ňąt…ē√¶jn…ôj…ô k…źňąm ≤is ≤…™j…ô, links=yes), ...

punitive detachments or regular infantry regiments. In December 1918, Trotsky ordered more barrier troops raised for each infantry formation. Barrier troops were also used to enforce Bolshevik control over food supplies, earning civilian hatred.

Given manpower shortages and 16 opposing foreign armies, Trotsky insisted on using former Tsarist officers as military specialists, combined with Bolshevik political commissars. Lenin commented:

In September 1918, facing military difficulties, the Bolshevik government declared martial law and reorganized the Red Army. The Supreme Military Council was abolished, and the position of commander-in-chief restored, filled by

Jukums VńĀcietis

Jukums VńĀcietis (; ‚Äď 28 July 1938) was a Latvian and Soviet military commander. He was a rare example of a notable Soviet leader who was not a member of the Communist Party (or of any other political party), until his demise during the Great ...

, commander of the

Latvian Riflemen. VńĀcietis handled day-to-day operations. Trotsky became chairman of the new Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic, retaining overall military control. Despite earlier clashes with VńĀcietis, Trotsky established a working relationship. This reorganization caused another conflict between Trotsky and Stalin in late September. Trotsky appointed former imperial general

Pavel Sytin to command the Southern Front, but Stalin refused to accept him in early October, and Sytin was recalled. Lenin and

Yakov Sverdlov

Yakov Mikhailovich Sverdlov ( ‚Äď 16 March 1919) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A key Bolshevik organizer of the October Revolution of 1917, Sverdlov served as chairman of the Secretariat of the Russian Communist Party from ...

tried to reconcile Trotsky and Stalin, but their meeting failed.

In 1919, 612 "hardcore" deserters out of 837,000 draft dodgers and deserters were executed under Trotsky's draconian measures. According to

Orlando Figes, most "deserters...were handed back to the military authorities, and formed into units for transfer to one of the rear armies or directly to the front". Even "malicious" deserters were returned to the ranks when reinforcements were desperate. Figes noted the Red Army instituted

amnesty

Amnesty () is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power officially forgiving certain classes of people who are subject to trial but have not yet be ...

weeks, prohibiting punitive measures against desertion, which encouraged the voluntary return of 98,000‚Äď132,000 deserters.

1919

Throughout late 1918 and early 1919, Trotsky's leadership faced attacks, including veiled accusations in Stalin-inspired newspaper articles and a direct attack by the Military Opposition at the

VIIIth Party Congress in March 1919. He weathered them, being elected one of five full members of the first

Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

after the Congress. But he later wrote:

In mid-1919, the Red Army had grown from 800,000 to 3,000,000 and fought on sixteen fronts, providing an opportunity for challenges to Trotsky's leadership. At the 3‚Äď4 July Central Committee meeting, after a heated exchange, the majority supported Kamenev and

Smilga against VńĀcietis and Trotsky. Trotsky's plan was rejected, and he was criticized for alleged leadership shortcomings, many personal. Stalin used this to pressure Lenin

[Chapter XXXVII o]

''My Life''

to dismiss Trotsky.

Significant changes were made to Red Army leadership. Trotsky was temporarily sent to the Southern Front, while Smilga informally coordinated work in Moscow. Most non-day-to-day Revolutionary Military Council members were relieved of duties on 8 July, and new members, including Smilga, were added. The same day, VńĀcietis was arrested by the Cheka on suspicion of an anti-Soviet plot and replaced by

Sergey Kamenev. After weeks in the south, Trotsky returned to Moscow and resumed control. A year later, Smilga and

Tukhachevsky

Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky ( rus, –ú–ł—Ö–į–ł–Ľ –Ě–ł–ļ–ĺ–Ľ–į–Ķ–≤–ł—á –Ę—É—Ö–į—á–Ķ–≤—Ā–ļ–ł–Ļ, Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevskiy, p=t äx…źňąt…ēefsk ≤…™j; ‚Äď 12 June 1937), nicknamed the Red Napoleon, was a Soviet general who was prominen ...

were defeated at the

Battle of Warsaw, but Trotsky's refusal to retaliate against Smilga earned his friendship and later support during 1920s intra-Party battles.

By October 1919, the government faced its worst crisis: Denikin's troops approached

Tula and Moscow from the south, and General

Nikolay Yudenich's troops approached Petrograd from the west. Lenin decided Petrograd had to be abandoned to defend Moscow. Trotsky argued Petrograd needed to be defended, partly to prevent

Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

and Finland from intervening. In a rare reversal, Trotsky, supported by Stalin and Zinoviev, prevailed against Lenin in the Central Committee.

1920

With Denikin and Yudenich defeated in late 1919, government emphasis shifted to the economy. Trotsky spent winter 1919‚Äď1920 in the Urals region restarting its economy. A false rumour of his assassination circulated internationally on New Year's Day 1920. Based on his experiences, he proposed abandoning

War Communism

War communism or military communism (, ''Vojenn√Ĺ kommunizm'') was the economic and political system that existed in Soviet Russia during the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1921. War communism began in June 1918, enforced by the Supreme Economi ...

policies, including grain confiscation, and partially restoring the grain market. Lenin, still committed to War Communism, rejected his proposal.

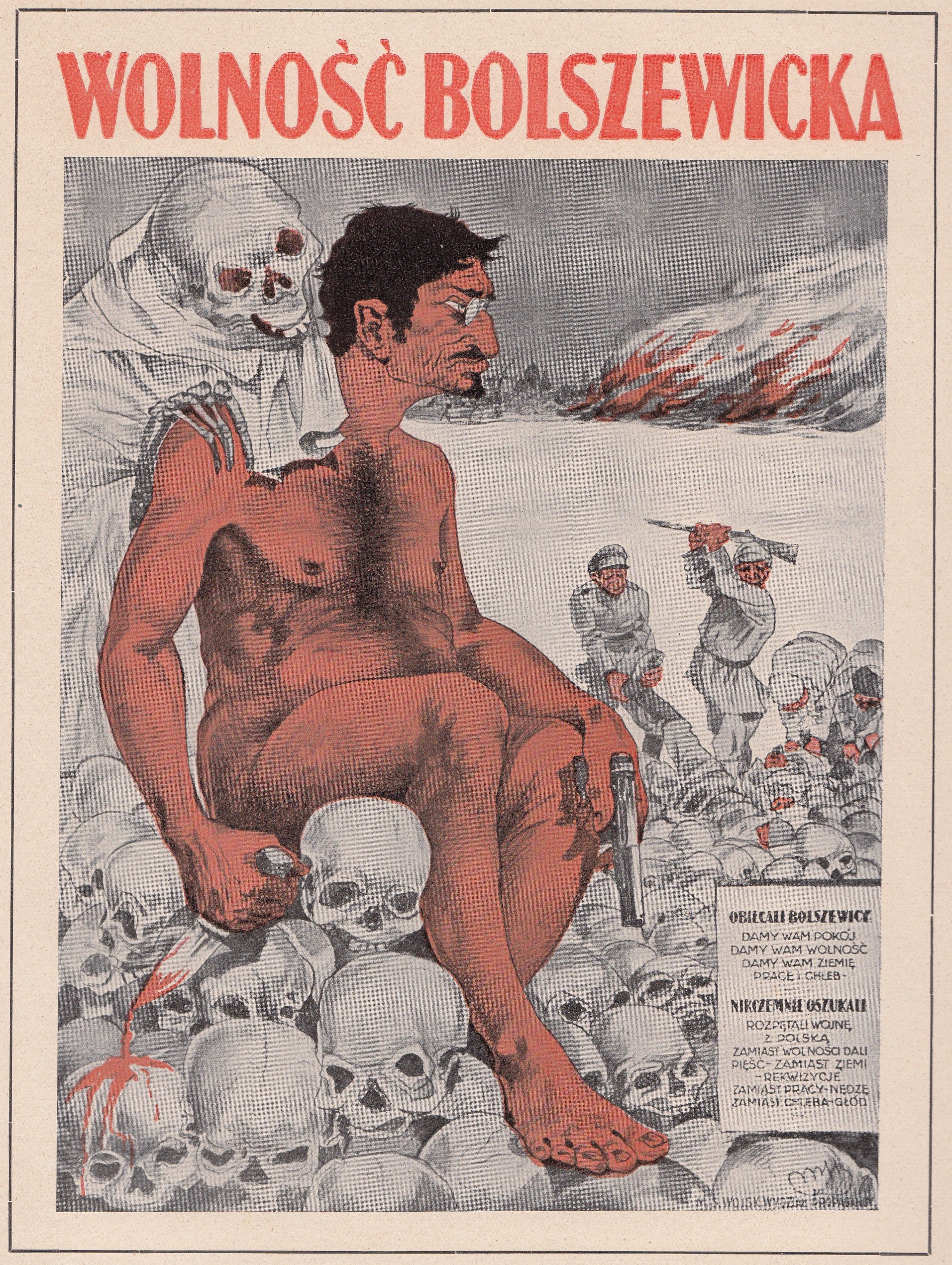

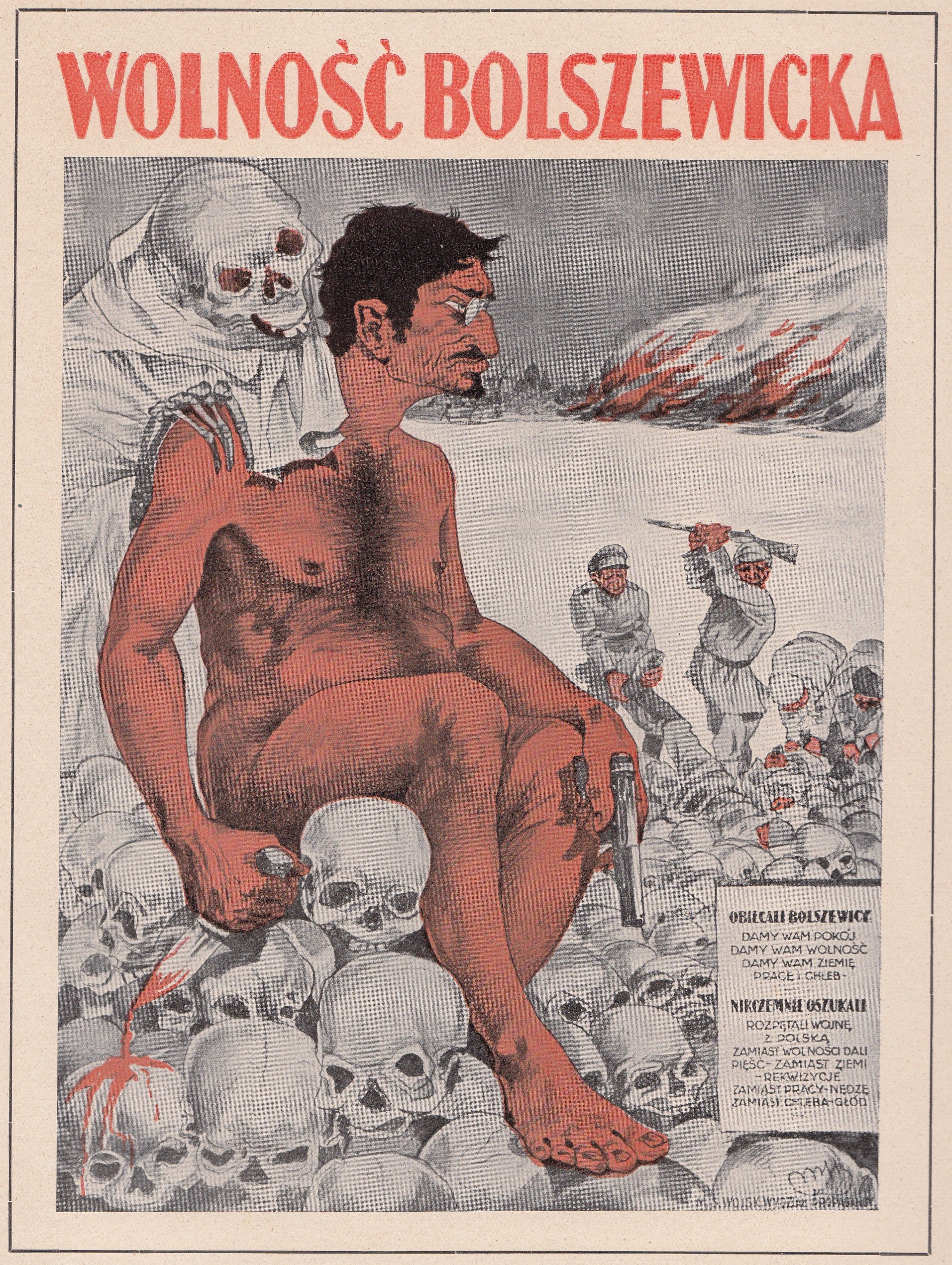

In early 1920, Soviet‚ÄďPolish tensions led to the

Polish‚ÄďSoviet War

The Polish‚ÄďSoviet War (14 February 1919 ‚Äď 18 March 1921) was fought primarily between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, following World War I and the Russian Revolution.

After the collapse ...

. Trotsky argued

the Red Army was exhausted and the government should sign a peace treaty with Poland quickly, not believing the Red Army would find much support in Poland. Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders believed Red Army successes meant "The defensive period of the war with worldwide imperialism was over, and we could, and had the obligation to, exploit the military situation to launch an offensive war." Poland defeated the Red Army, turning back the offensive at the

Battle of Warsaw in August 1920. Back in Moscow, Trotsky again argued for peace, and this time prevailed.

Trade union debate (1920‚Äď1921)

During the 1920‚Äď1921 trade union debate, Trotsky argued that trade unions should be integrated directly into the state apparatus, advocating for a "militarization of labour" to rebuild the Soviet economy. He believed that in a workers' state, the state should control unions, with workers treated as "soldiers of labour" under strict discipline.

This position was sharply criticized by

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, who argued unions should retain some independence and act as "schools of communism" rather than state instruments. Lenin's view prevailed at the

10th Congress in 1921. Several of Trotsky's supporters, including

Nikolay Krestinsky, lost leadership positions.

Kronstadt rebellion

In March 1921, during the Kronstadt Rebellion, sailors and soldiers at the

Kronstadt

Kronstadt (, ) is a Russian administrative divisions of Saint Petersburg, port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal cities of Russia, federal city of Saint Petersburg, located on Kotlin Island, west of Saint Petersburg, near the head ...

naval base revolted against the Bolshevik government, demanding greater freedom for workers and peasants, an end to one-party rule, and restoration of civil rights. The rebellion, occurring simultaneously with the 10th Party Congress, further destabilized the fragile political situation.

Trotsky, as Commissar of War, was instrumental in ordering the rebellion's suppression. On 18 March 1921, after failed negotiations, the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

stormed the island, resulting in thousands of Kronstadt sailors' deaths. Trotsky justified the action by presenting evidence of foreign backing, a claim contested by several historians. His role has been criticized, with anarchists like

Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 ‚Äď May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born Anarchism, anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europ ...

accusing him of betraying the revolution's democratic ideals.

Trotsky's contribution to the Russian Revolution

Historian Vladimir Cherniaev sums up Trotsky's main contributions:

Historian Geoffrey Swain argues:

Lenin said in 1921 that Trotsky was "in love with organisation," but in working politics, "he has not got a clue." Swain explains this by arguing Trotsky was not good at teamwork, being a loner who had mostly worked as a journalist, not a professional revolutionary like others.

Lenin's illness (1922‚Äď1923)

In late 1921, Lenin's health deteriorated. He suffered three strokes between 25 May 1922 and 9 March 1923, causing paralysis, loss of speech, and eventual death on 21 January 1924. With Lenin increasingly sidelined, Stalin was elevated to the new position of Central Committee

General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, Power (social and political), power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the org ...

in April 1922. Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev formed a

triumvirate

A triumvirate () or a triarchy is a political institution ruled or dominated by three individuals, known as triumvirs (). The arrangement can be formal or informal. Though the three leaders in a triumvirate are notionally equal, the actual distr ...

(''

troika'') with Stalin to prevent Trotsky, publicly number two and Lenin's

heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of a person with a better claim to the position in question. This is in contrast to an heir app ...

, from succeeding Lenin.

The rest of the expanded Politburo (Rykov,

Mikhail Tomsky, Bukharin) initially remained uncommitted but eventually joined the ''troika''. Stalin's patronage power as General Secretary played a role, but Trotsky and his supporters later concluded a more fundamental reason was the slow bureaucratisation of the Soviet regime after the Civil War. Much of the Bolshevik elite desired 'normality,' while Trotsky personified a turbulent revolutionary period they wished to leave behind.