Yukio Mishima on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, born , was a Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor, model,

, later known as , was born in Nagazumi-cho, Yotsuya-ku of

, later known as , was born in Nagazumi-cho, Yotsuya-ku of

Mishima was enrolled at the age of six in the elite

Mishima was enrolled at the age of six in the elite  On 19 August, four days after Japan's surrender, Mishima's mentor Zenmei Hasuda, who had been drafted and deployed to the Malay peninsula, shot and killed a superior officer for criticizing the Emperor before turning his pistol on himself. Mishima learned of the incident a year later and contributed poetry in Hasuda's honor at a memorial service in November 1946. On 23 October 1945 (Showa 20), Mishima's beloved younger sister Mitsuko died suddenly at the age of 17 from

On 19 August, four days after Japan's surrender, Mishima's mentor Zenmei Hasuda, who had been drafted and deployed to the Malay peninsula, shot and killed a superior officer for criticizing the Emperor before turning his pistol on himself. Mishima learned of the incident a year later and contributed poetry in Hasuda's honor at a memorial service in November 1946. On 23 October 1945 (Showa 20), Mishima's beloved younger sister Mitsuko died suddenly at the age of 17 from

After Japan's defeat in World War II, the country was

After Japan's defeat in World War II, the country was  In 1946, Mishima began his first novel, , a story about two young members of the aristocracy drawn towards suicide. It was published in 1948, and placed Mishima in the ranks of the Second Generation of Postwar Writers. The following year, he published , a semi-autobiographical account of a young homosexual man who hides behind a mask to fit into society. The novel was extremely successful and made Mishima a celebrity at the age of 24. Around 1949, Mishima also published a literary essay about Kawabata, for whom he had always held a deep appreciation, in .

Mishima enjoyed international travel. In 1952, he took a world tour and published his travelogue as . He visited

In 1946, Mishima began his first novel, , a story about two young members of the aristocracy drawn towards suicide. It was published in 1948, and placed Mishima in the ranks of the Second Generation of Postwar Writers. The following year, he published , a semi-autobiographical account of a young homosexual man who hides behind a mask to fit into society. The novel was extremely successful and made Mishima a celebrity at the age of 24. Around 1949, Mishima also published a literary essay about Kawabata, for whom he had always held a deep appreciation, in .

Mishima enjoyed international travel. In 1952, he took a world tour and published his travelogue as . He visited  Mishima made use of contemporary events in many of his works. , published in 1956, is a fictionalization of the burning down of the

Mishima made use of contemporary events in many of his works. , published in 1956, is a fictionalization of the burning down of the

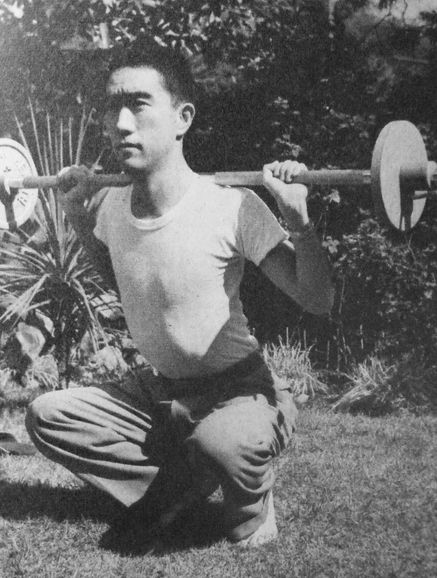

In 1955, Mishima took up

In 1955, Mishima took up

On 25 November 1970, Mishima and four members of the Tatenokai—, , , and —used a pretext to visit the commandant of :ja:防衛省市ヶ谷地区, Camp Ichigaya, a military base in central Tokyo and the headquarters of the Eastern Command of the

On 25 November 1970, Mishima and four members of the Tatenokai—, , , and —used a pretext to visit the commandant of :ja:防衛省市ヶ谷地区, Camp Ichigaya, a military base in central Tokyo and the headquarters of the Eastern Command of the

Much speculation has surrounded Mishima's suicide. At the time of his death he had just completed the final book in his ''The Sea of Fertility, Sea of Fertility'' tetralogy. He was recognized as one of the most important post-war stylists of the Japanese language. Mishima wrote 34 novels, about 50 plays, about 25 books of short stories, at least 35 books of essays, one libretto, and one film.

Much speculation has surrounded Mishima's suicide. At the time of his death he had just completed the final book in his ''The Sea of Fertility, Sea of Fertility'' tetralogy. He was recognized as one of the most important post-war stylists of the Japanese language. Mishima wrote 34 novels, about 50 plays, about 25 books of short stories, at least 35 books of essays, one libretto, and one film.

Mishima's grave is located at the Tama Cemetery in Fuchū, Tokyo. The Mishima Yukio Prize, Mishima Prize was established in 1988 to honor his life and works. On 3 July 1999, was opened in Yamanakako, Yamanashi, Yamanakako, Yamanashi Prefecture.

The Mishima Incident helped inspire the formation of New Right (:ja:新右翼, 新右翼, ''shin uyoku'') groups in Japan, such as the , founded by , who was Mishima's follower. Compared to older groups such as Bin Akao's Greater Japan Patriotic Party that took a pro-American, anti-communist stance, New Right groups such as the Issuikai tended to emphasize ethnic nationalism and anti-Americanism.

A memorial service Death anniversary, deathday for Mishima, called , is held every year in Japan on 25 November by the and former members of the . Apart from this, a memorial service is held every year by former Tatenokai members, which began in 1975, the year after Masahiro Ogawa, Masayoshi Koga, and Hiroyasu Koga were released on parole.

A variety of cenotaphs and memorial stones have been erected in honor of Mishima's memory in various places around Japan. For example, stones have been erected at Hachiman Shrine in Kakogawa, Hyōgo, Kakogawa City, Hyogo Prefecture, where his grandfather's permanent domicile was; in front of the 2nd company corps at JGSDF Camp Takigahara; and in one of Mishima's acquaintance's home garden. There is also a "Monument of Honor Yukio Mishima & Masakatsu Morita" in front of the Rissho University Shonan High school in Shimane Prefecture.

The Mishima Yukio Shinto shrine, Shrine was built in the suburb of Fujinomiya, Shizuoka, Fujinomiya, Shizuoka Prefecture, on 9 January 1983.

A 1985 biographical film by Paul Schrader titled ''Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters'' depicts his life and work; however, it has never been given a theatrical presentation in Japan. A 2012 Japanese film titled ''11:25 The Day He Chose His Own Fate'' also looks at Mishima's last day. The 1983 gay pornographic film ''Beautiful Mystery'' satirised the homosexual undertones of Mishima's career.

In 2014, Mishima was one of the inaugural honourees in the Rainbow Honor Walk, a List of halls and walks of fame, walk of fame in San Francisco's Castro neighbourhood noting LGBTQ people who have "made significant contributions in their fields".

David Bowie painted a large expressionist portrait of Mishima, which he hung at his Berlin residence.

Mishima's grave is located at the Tama Cemetery in Fuchū, Tokyo. The Mishima Yukio Prize, Mishima Prize was established in 1988 to honor his life and works. On 3 July 1999, was opened in Yamanakako, Yamanashi, Yamanakako, Yamanashi Prefecture.

The Mishima Incident helped inspire the formation of New Right (:ja:新右翼, 新右翼, ''shin uyoku'') groups in Japan, such as the , founded by , who was Mishima's follower. Compared to older groups such as Bin Akao's Greater Japan Patriotic Party that took a pro-American, anti-communist stance, New Right groups such as the Issuikai tended to emphasize ethnic nationalism and anti-Americanism.

A memorial service Death anniversary, deathday for Mishima, called , is held every year in Japan on 25 November by the and former members of the . Apart from this, a memorial service is held every year by former Tatenokai members, which began in 1975, the year after Masahiro Ogawa, Masayoshi Koga, and Hiroyasu Koga were released on parole.

A variety of cenotaphs and memorial stones have been erected in honor of Mishima's memory in various places around Japan. For example, stones have been erected at Hachiman Shrine in Kakogawa, Hyōgo, Kakogawa City, Hyogo Prefecture, where his grandfather's permanent domicile was; in front of the 2nd company corps at JGSDF Camp Takigahara; and in one of Mishima's acquaintance's home garden. There is also a "Monument of Honor Yukio Mishima & Masakatsu Morita" in front of the Rissho University Shonan High school in Shimane Prefecture.

The Mishima Yukio Shinto shrine, Shrine was built in the suburb of Fujinomiya, Shizuoka, Fujinomiya, Shizuoka Prefecture, on 9 January 1983.

A 1985 biographical film by Paul Schrader titled ''Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters'' depicts his life and work; however, it has never been given a theatrical presentation in Japan. A 2012 Japanese film titled ''11:25 The Day He Chose His Own Fate'' also looks at Mishima's last day. The 1983 gay pornographic film ''Beautiful Mystery'' satirised the homosexual undertones of Mishima's career.

In 2014, Mishima was one of the inaugural honourees in the Rainbow Honor Walk, a List of halls and walks of fame, walk of fame in San Francisco's Castro neighbourhood noting LGBTQ people who have "made significant contributions in their fields".

David Bowie painted a large expressionist portrait of Mishima, which he hung at his Berlin residence.

三島由紀夫文学館 The Mishima Yukio Literary Museum website

In Japanese only, with the exception of one page (see "English Guide" at top right)

山中湖文学の森公園「三島由紀夫文学館」Yamanakako Forest Park of Literature "Mishima Yukio Literary Museum"

* *

a ceremony commemorating his 70th birthday * , from a 1980s BBC documentary (9:02) * , from Canadian Television (3:59) * – Full NHK Interview in 1966 (9:21)

Yukio Mishima's attempt at personal branding comes to light in the rediscovered 'Star'

Nicolas Gattig, ''The Japan Times'' (27 April 2019) * {{DEFAULTSORT:Mishima, Yukio Yukio Mishima, 1925 births 1970 suicides 1970s coups d'état and coup attempts 20th-century essayists 20th-century Japanese dramatists and playwrights 20th-century Japanese male actors 20th-century Japanese novelists 20th-century Japanese short story writers 20th-century poets 20th-century pseudonymous writers Attempted coups in Japan Bisexual male actors Bisexual writers Conservatism in Japan Controversies in Japan Cultural critics Deaths by decapitation Far-right politics in Japan Film controversies in Japan Imperial Japanese Army personnel of World War II Imperial Japanese Army soldiers Japanese activists Japanese anti-communists Japanese bodybuilders Japanese essayists Japanese film directors Japanese government officials Japanese kendoka Japanese male karateka Japanese male models Japanese male short story writers Japanese nationalists Japanese poets Japanese psychological fiction writers Japanese social commentators Kabuki playwrights LGBT people from Japan LGBT film directors LGBT models LGBT writers from Japan LGBT-related suicides Male actors from Tokyo Noh playwrights Pantheists People from Shinjuku People of Shōwa-period Japan People of the Empire of Japan Seppuku from Meiji period to present Social critics University of Tokyo alumni Yomiuri Prize winners Writers from Tokyo

Shinto

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shintois ...

ist, nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

, and founder of the , an unarmed civilian militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

. Mishima is considered one of the most important Japanese authors of the 20th century. He was considered for the Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901

, ...

in 1968, but the award went to his countryman and benefactor Yasunari Kawabata

was a Japanese novelist and short story writer whose spare, lyrical, subtly shaded prose works won him the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1968, the first Japanese author to receive the award. His works have enjoyed broad international appeal a ...

. His works include the novels and , and the autobiographical essay . Mishima's work is characterized by "its luxurious vocabulary and decadent metaphors, its fusion of traditional Japanese and modern Western literary styles, and its obsessive assertions of the unity of beauty, eroticism

Eroticism () is a quality that causes sexual feelings, as well as a philosophical contemplation concerning the aesthetics of sexual desire, sensuality, and romantic love. That quality may be found in any form of artwork, including painting, sc ...

and death", according to author Andrew Rankin.

Mishima's political activities made him a controversial figure, which he remains in modern Japan. From his mid-30s, Mishima's right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, authorit ...

ideology was increasingly revealed. He was proud of the traditional culture and spirit of Japan, and opposed what he saw as western-style materialism, along with Japan's postwar democracy, globalism, and communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, worrying that by embracing these ideas the Japanese people would lose their "national essence" (''kokutai

is a concept in the Japanese language translatable as " system of government", "sovereignty", "national identity, essence and character", "national polity; body politic; national entity; basis for the Emperor's sovereignty; Japanese constitu ...

'') and their distinctive cultural heritage (Shinto

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shintois ...

and Yamato-damashii

or is a Japanese language term for the cultural values and characteristics of the Japanese people. The phrase was coined in the Heian period to describe the indigenous Japanese 'spirit' or cultural values as opposed to cultural values of foreign ...

) to become a "rootless" people. collected in collected in , Mishima formed the Tatenokai for the avowed purpose of restoring sacredness and dignity to the Emperor of Japan

The Emperor of Japan is the monarch and the head of the Imperial House of Japan, Imperial Family of Japan. Under the Constitution of Japan, he is defined as the symbol of the Japanese state and the unity of the Japanese people, and his positio ...

. On 25 November 1970, Mishima and four members of his militia entered a military base in central Tokyo, took its commandant hostage, and unsuccessfully tried to inspire the Japan Self-Defense Forces

The Japan Self-Defense Forces ( ja, 自衛隊, Jieitai; abbreviated JSDF), also informally known as the Japanese Armed Forces, are the unified ''de facto''Since Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution outlaws the formation of armed forces, the ...

to rise up and overthrow Japan's 1947 Constitution (which he called "a constitution of defeat"). After his speech and screaming of "Long live the Emperor!", he committed seppuku.

Life and work

Early life

, later known as , was born in Nagazumi-cho, Yotsuya-ku of

, later known as , was born in Nagazumi-cho, Yotsuya-ku of Tokyo City

was a municipality in Japan and part of Tokyo-fu which existed from 1 May 1889 until its merger with its prefecture on 1 July 1943. The historical boundaries of Tokyo City are now occupied by the Special Wards of Tokyo. The new merged gove ...

(now part of Yotsuya

is a neighborhood in Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan.

It is a former ward (四谷区 ''Yotsuya-ku'') in the now-defunct Tokyo City. In 1947, when the 35 wards of Tokyo were reorganized into 23, it was merged with Ushigome ward of Tokyo City and Yodo ...

, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo). He chose his pen name when he was 16. His father was , a government official in the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, and his mother, , was the daughter of the 5th principal of the Kaisei Academy

The Kaisei Academy (開成学園) is a preparatory private secondary school for boys located in the Arakawa ward of Tokyo, Japan. It was founded in 1871.

The Kaisei Academy has since educated notable figures across many different fields and i ...

. Shizue's father, , was a scholar of the Chinese classics

Chinese classic texts or canonical texts () or simply dianji (典籍) refers to the Chinese texts which originated before the imperial unification by the Qin dynasty in 221 BC, particularly the "Four Books and Five Classics" of the Neo-Confucian ...

, and the Hashi family had served the Maeda clan

was a Japanese samurai clan who occupied most of the Hokuriku region of central Honshū from the end of the Sengoku period through the Meiji restoration of 1868. The Maeda claimed descent from the Sugawara clan of Sugawara no Kiyotomo and Sugaw ...

for generations in Kaga Domain. Mishima's paternal grandparents were , the third Governor-General of Karafuto Prefecture

Karafuto Prefecture ( ja, 樺太庁, ''Karafuto-chō''; russian: Префектура Карафуто, Prefektura Karafuto), commonly known as South Sakhalin, was a prefecture of Japan located in Sakhalin from 1907 to 1949.

Karafuto became ter ...

, and . Mishima received his birth name Kimitake (公威, also read ''Kōi'' in on-yomi

are the logographic Chinese characters taken from the Chinese script and used in the writing of Japanese. They were made a major part of the Japanese writing system during the time of Old Japanese and are still used, along with the subsequent ...

) in honor of who was a benefactor of Sadatarō. He had a younger sister, , who died of typhus in 1945 at the age of 17, and a younger brother, .

Mishima's childhood home was a rented house, though a fairly large two-floor house that was the largest in the neighborhood. He lived with his parents, siblings and paternal grandparents, as well as six maids, a houseboy, and a manservant. His grandfather was in debt, so there were no remarkable household items left on the first floor.

Mishima's early childhood was dominated by the presence of his grandmother, Natsuko, who took the boy and separated him from his immediate family for several years. She was the granddaughter of , the ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji era, Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast, hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and n ...

'' of Shishido, which was a branch domain of Mito Domain

was a Japanese domain of the Edo period. It was associated with Hitachi Province in modern-day Ibaraki Prefecture.Hitachi Province

was an old provinces of Japan, old province of Japan in the area of Ibaraki Prefecture.Louis Frédéric, Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "''Hitachi fudoki''" in . It was sometimes called . Hitachi Province bordered on Shimōsa Province, S ...

; therefore, Mishima was a direct descendant of the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Tokugawa-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia ...

, , through his grandmother. Natsuko's father, , had been a Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

justice, and Iwanojō's adoptive father, , had been a bannerman of the Tokugawa House during the Bakumatsu

was the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate ended. Between 1853 and 1867, Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy known as and changed from a feudal Tokugawa shogunate to the modern empire of the Meiji government ...

. Natsuko had been raised in the household of Prince Arisugawa Taruhito

was a Japanese career officer in the Imperial Japanese Army, who became the 9th head of the line of '' shinnōke'' cadet branches of the Imperial Family of Japan on September 9, 1871.

Early life

Prince Arisugawa Taruhito was born in Kyoto in ...

, and she maintained considerable aristocratic pretensions even after marrying Sadatarō, a bureaucrat who had made his fortune in the newly opened colonial frontier in the north, and who eventually became Governor-General of Karafuto Prefecture on Sakhalin Island. Sadatarō's father, , and grandfather, , had been farmers. Natsuko was prone to violent outbursts, which are occasionally alluded to in Mishima's works, and to whom some biographers have traced Mishima's fascination with death. She did not allow Mishima to venture into the sunlight, engage in any kind of sport, or play with other boys. He spent much of his time either alone or with female cousins and their dolls., collected in

Mishima returned to his immediate family when he was 12. His father Azusa had a taste for military discipline, and worried Natsuko's style of childrearing was too soft. When Mishima was an infant, Azusa employed parenting tactics such as holding Mishima up to the side of a speeding train. He also raided his son's room for evidence of an "effeminate" interest in literature, and often ripped his son's manuscripts apart. Although Azusa forbade him to write any further stories, Mishima continued to write in secret, supported and protected by his mother, who was always the first to read a new story.

When Mishima was 13, Natsuko took him to see his first Kabuki

is a classical form of Japanese dance-drama. Kabuki theatre is known for its heavily-stylised performances, the often-glamorous costumes worn by performers, and for the elaborate make-up worn by some of its performers.

Kabuki is thought to ...

play: ''Kanadehon Chūshingura

is an 11-act bunraku puppet play composed in 1748. It is one of the most popular Japanese plays, ranked with Zeami's '' Matsukaze'', although the vivid action of Chūshingura differs dramatically from ''Matsukaze''.

Medium

During this portion o ...

,'' an allegory of the story of the 47 Rōnin. He was later taken to his first Noh

is a major form of classical Japanese dance-drama that has been performed since the 14th century. Developed by Kan'ami and his son Zeami, it is the oldest major theatre art that is still regularly performed today. Although the terms Noh and ' ...

play ('' Miwa'', a story featuring Amano-Iwato

is a cave in Japanese mythology. According to the ''Kojiki'' (''Records of Ancient Matters'') and the '' Nihon Shoki'', the bad behavior of Susano'o, the Japanese god of storms, drove his sister Amaterasu into the Ama-no-Iwato cave. The land wa ...

) by his maternal grandmother . From these early experiences, Mishima became addicted to Kabuki and Noh. He began attending performances every month and grew deeply interested in these traditional Japanese dramatic art forms., collected in

Schooling and early works

Mishima was enrolled at the age of six in the elite

Mishima was enrolled at the age of six in the elite Gakushūin

The or Peers School (Gakushūin School Corporation), initially known as Gakushūjo, is a Japanese educational institution in Tokyo, originally established to educate the children of Japan's nobility. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2002)"Gakushū- ...

, the Peers' School in Tokyo, which had been established in the Meiji period

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization ...

to educate the Imperial family and the descendants of the old feudal nobility. At 12, Mishima began to write his first stories. He read myth

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of Narrative, narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or Origin myth, origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not Objectivity (philosophy), ...

s (Kojiki

The , also sometimes read as or , is an early Japanese chronicle of myths, legends, hymns, genealogies, oral traditions, and semi-historical accounts down to 641 concerning the origin of the Japanese archipelago, the , and the Japanese imperia ...

, Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the Cosmogony, origin and Cosmology#Metaphysical co ...

, etc.) and the works of numerous classic Japanese authors as well as Raymond Radiguet

Raymond Radiguet (18 June 1903 – 12 December 1923) was a French novelist and poet whose two novels were noted for their explicit themes, and unique style and tone.

Early life

Radiguet was born in Saint-Maur, Val-de-Marne, close to Paris, th ...

, Jean Cocteau

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau (, , ; 5 July 1889 – 11 October 1963) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, designer, filmmaker, visual artist and critic. He was one of the foremost creatives of the su ...

, Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

, Rainer Maria Rilke

René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke (4 December 1875 – 29 December 1926), shortened to Rainer Maria Rilke (), was an Austrian poet and novelist. He has been acclaimed as an idiosyncratic and expressive poet, and is widely recogni ...

, Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novella ...

, Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

, Charles Baudelaire

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (, ; ; 9 April 1821 – 31 August 1867) was a French poetry, French poet who also produced notable work as an essayist and art critic. His poems exhibit mastery in the handling of rhyme and rhythm, contain an exoticis ...

, l'Isle-Adam, and other European authors in translation. He also studied German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

. After six years at school, he became the youngest member of the editorial board of its literary society. Mishima was attracted to the works of the Japanese poet , poet and novelist , and poet , who inspired Mishima's appreciation of classical Japanese ''waka

Waka may refer to:

Culture and language

* Waka (canoe), a Polynesian word for canoe; especially, canoes of the Māori of New Zealand

** Waka ama, a Polynesian outrigger canoe

** Waka hourua, a Polynesian ocean-going canoe

** Waka taua, a Māori w ...

'' poetry. Mishima's early contributions to the Gakushūin literary magazine included haiku

is a type of short form poetry originally from Japan. Traditional Japanese haiku consist of three phrases that contain a ''kireji'', or "cutting word", 17 '' on'' (phonetic units similar to syllables) in a 5, 7, 5 pattern, and a ''kigo'', or se ...

and waka

Waka may refer to:

Culture and language

* Waka (canoe), a Polynesian word for canoe; especially, canoes of the Māori of New Zealand

** Waka ama, a Polynesian outrigger canoe

** Waka hourua, a Polynesian ocean-going canoe

** Waka taua, a Māori w ...

poetry before he turned his attention to prose.

In 1941, at the age of 16, Mishima was invited to write a short story for the ''Hojinkai-zasshi'', and he submitted , a story in which the narrator describes the feeling that his ancestors somehow still live within him. The story uses the type of metaphors and aphorisms that became Mishima's trademarks. He mailed a copy of the manuscript to his Japanese teacher for constructive criticism. Shimizu was so impressed that he took the manuscript to a meeting of the editorial board of the prestigious literary magazine , of which he was a member. At the editorial board meeting, the other board members read the story and were very impressed; they congratulated themselves for discovering a genius and published it in the magazine. The story was later published as a limited book edition (4,000 copies) in 1944 due to a wartime paper shortage. Mishima had it published as a keepsake to remember him by, as he assumed that he would die in the war.

In order to protect him from potential backlash from Azusa, Shimizu and the other editorial board members coined the pen-name Yukio Mishima. collected in They took "Mishima" from Mishima Station

is a railway station in the city of Mishima, Shizuoka, Japan, operated by the Central Japan Railway Company (JR Central). It is also a union station with the Izuhakone Railway. The station was also a freight terminal of the Japan Freight Railwa ...

, which Shimizu and fellow ''Bungei Bunka'' board member Hasuda Zenmei passed through on their way to the editorial meeting, which was held in Izu, Shizuoka

is a city located in central Izu Peninsula in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 30,678 in 13,390 households, and a population density of 84 persons per km2. The total area of the city was .

Geography

Izu ...

. The name "Yukio" came from ''yuki'' (雪), the Japanese word for "snow," because of the snow they saw on Mount Fuji

, or Fugaku, located on the island of Honshū, is the highest mountain in Japan, with a summit elevation of . It is the second-highest volcano located on an island in Asia (after Mount Kerinci on the island of Sumatra), and seventh-highest p ...

as the train passed. In the magazine, Hasuda praised Mishima's genius as follows:This youthful author is a heaven-sent child of eternal Japanese history. He is much younger than we are, but has arrived on the scene already quite mature. collected inHasuda, who became something of a mentor to Mishima, was an ardent nationalist and a fan of

Motoori Norinaga

was a Japanese scholar of ''Kokugaku'' active during the Edo period. He is conventionally ranked as one of the Four Great Men of Kokugaku (nativist) studies.

Life

Norinaga was born in what is now Matsusaka in Ise Province (now part of Mie Pre ...

(1730–1801), a scholar of ''kokugaku

''Kokugaku'' ( ja, 國學, label=Kyūjitai, ja, 国学, label=Shinjitai; literally "national study") was an academic movement, a school of Japanese philology and philosophy originating during the Tokugawa period. Kokugaku scholars worked to refo ...

'' from the Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was characteriz ...

who preached Japanese traditional values and devotion to the Emperor. Hasuda had previously fought for the Imperial Japanese Army in China in 1938, and in 1943 he was recalled to active service for deployment as a first lieutenant in the Southeast Asian theater. At a farewell party thrown for Hasuda by the ''Bungei Bunka'' group, Hasuda offered the following parting words to Mishima: I have entrusted the future of Japan to you.According to Mishima, these words were deeply meaningful to him, and had a profound effect on the future course of his life. Later in 1941, Mishima wrote in his notebook an essay about his deep devotion to

Shintō

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shintoist ...

, titled . Mishima's story , published in 1946, describes a homosexual love he felt at school and being teased from members of the school's rugby union

Rugby union, commonly known simply as rugby, is a close-contact team sport that originated at Rugby School in the first half of the 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand. In its m ...

club because he belonged to the literary society. Another story from 1954, , was also based on Mishima's memories of his time at Gakushūin Junior High School.

On 9 September 1944, Mishima graduated Gakushūin High School at the top of the class, and became a graduate representative., collected in Emperor Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

was present at the graduation ceremony, and Mishima later received a silver watch from the Emperor at the Imperial Household Ministry.

On 27 April 1944, during the final years of World War II, Mishima received a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vessel ...

notice for the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor o ...

and barely passed his conscription examination on 16 May 1944, with a less desirable rating of "second class" conscript. He had a cold during his medical check on convocation day (10 February 1945), and the young army doctor misdiagnosed Mishima with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

, declared him unfit for service, and sent him home. collected in Scholars have argued that Mishima's failure to receive a "first class" rating on his conscription exam (reserved only for the most physically fit recruits), in combination with the illness which led him to be erroneously declared unfit for duty, contributed to an inferiority complex over his frail constitution that later led to his obsession with physical fitness and bodybuilding.

The day before his failed medical exam, Mishima wrote a farewell message to his family, ending with the words , and prepared clippings of his hair and nails to be kept as mementos by his parents.photograph of the will in The troops of the unit that Mishima was supposed to have joined were sent to the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, where most of them were killed. Mishima's parents were ecstatic that he did not have to go to war, but Mishima's mood was harder to read; Mishima's mother overheard him say he wished he could have joined a " Special Attack" ( 特攻, ''tokkō'') unit. Around that time, Mishima admired kamikaze pilots

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to ...

and other "special attack" units in letters to friends and private notes.

Mishima was deeply affected by Emperor Hirohito's radio broadcast announcing Japan's surrender on 15 August 1945, and vowed to protect Japanese cultural traditions and help rebuild Japanese culture after the destruction of the war.Mishima's letters to his friends(Makoto Mitani, Akira Kanzaki) and teacher Fumio Shimizu in August 1945, collected in He wrote in his diary: Only by preserving Japanese irrationality will we be able contribute to world culture 100 years from now.

On 19 August, four days after Japan's surrender, Mishima's mentor Zenmei Hasuda, who had been drafted and deployed to the Malay peninsula, shot and killed a superior officer for criticizing the Emperor before turning his pistol on himself. Mishima learned of the incident a year later and contributed poetry in Hasuda's honor at a memorial service in November 1946. On 23 October 1945 (Showa 20), Mishima's beloved younger sister Mitsuko died suddenly at the age of 17 from

On 19 August, four days after Japan's surrender, Mishima's mentor Zenmei Hasuda, who had been drafted and deployed to the Malay peninsula, shot and killed a superior officer for criticizing the Emperor before turning his pistol on himself. Mishima learned of the incident a year later and contributed poetry in Hasuda's honor at a memorial service in November 1946. On 23 October 1945 (Showa 20), Mishima's beloved younger sister Mitsuko died suddenly at the age of 17 from typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

by drinking untreated water. Around that same time he also learned that , a classmate's sister whom he had hoped to marry, was engaged to another man. These tragic incidents in 1945 became a powerful motive force in inspiring Mishima's future literary work., collected in

At the end of the war, his father Azusa "half-allowed" Mishima to become a novelist. He was worried that his son could actually become a professional novelist, and hoped instead that his son would be a bureaucrat like himself and Mishima's grandfather Sadatarō. He advised his son to enroll in the Faculty of Law instead of the literature department. Attending lectures during the day and writing at night, Mishima graduated from the University of Tokyo

, abbreviated as or UTokyo, is a public research university located in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Established in 1877, the university was the first Imperial University and is currently a Top Type university of the Top Global University Project by ...

in 1947. He obtained a position in the Ministry of the Treasury

The (lit. the department of the great treasury) was a division of the eighth-century Japanese government of the Imperial Court in Kyoto, instituted in the Asuka period and formalized during the Heian period. The Ministry was replaced in the Mei ...

and seemed set up for a promising career as a government bureaucrat. However, after just one year of employment Mishima had exhausted himself so much that his father agreed to allow him to resign from his post and devote himself to writing full time.

In 1945, Mishima began the short story and continued to work on it through the end of World War II. After the war, it was praised by Shizuo Itō whom Mishima respected.

Post-war literature

occupied

' (Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 October ...

by the U.S.-led Allied Powers. At the urging of the occupation authorities, many people who held important posts in various fields were purged from public office. The media and publishing industry were also censored, and were not allowed to engage in forms of expression reminiscent of wartime Japanese nationalism. In addition, literary figures, including many of those who had been close to Mishima before the end of the war, were branded "war criminal literary figures". Some people denounced them and converted to left-wing politics, whom Mishima criticized as "opportunists" in his letters to friends. Some prominent literary figures became leftists, and joined the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A ...

as a reaction against wartime militarism and writing socialist realist

Socialist realism is a style of idealized realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and was the official style in that country between 1932 and 1988, as well as in other socialist countries after World War II. Socialist realism is ...

literature that might support the cause of socialist revolution. Their influence had increased in the Japanese literary world following the end of the war, which Mishima found difficult to accept. Although Mishima was just 20 years old at this time, he worried that his type of literature, based on the 1930s , had already become obsolete.

Mishima had heard that famed writer Yasunari Kawabata

was a Japanese novelist and short story writer whose spare, lyrical, subtly shaded prose works won him the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1968, the first Japanese author to receive the award. His works have enjoyed broad international appeal a ...

had praised his work before the end of the war. Uncertain of who else to turn to, Mishima took the manuscripts for and with him, visited Kawabata in Kamakura

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

Kamakura has an estimated population of 172,929 (1 September 2020) and a population density of 4,359 persons per km² over the total area of . Kamakura was designated as a city on 3 November 1939.

Kamak ...

, and asked for his advice and assistance in January 1946. Kawabata was impressed, and in June 1946, following Kawabata's recommendation, "The Cigarette" was published in the new literary magazine , followed by "The Middle Ages" in December 1946. "The Middle Ages" is set in Japan's historical Muromachi Period

The is a division of Japanese history running from approximately 1336 to 1573. The period marks the governance of the Muromachi or Ashikaga shogunate (''Muromachi bakufu'' or ''Ashikaga bakufu''), which was officially established in 1338 by t ...

and explores the motif of '' shudō'' (衆道, man-boy love) against a backdrop of the death of the ninth Ashikaga Ashikaga (足利) may refer to:

* Ashikaga clan (足利氏 ''Ashikaga-shi''), a Japanese samurai clan descended from the Minamoto clan; and that formed the basis of the eponymous shogunate

** Ashikaga shogunate (足利幕府 ''Ashikaga bakufu''), a ...

shogun in battle at the age of 25, and his father 's resultant sadness. The story features the fictional character Kikuwaka, a beautiful teenage boy who was beloved by both Yoshihisa and Yoshimasa, who fails in an attempt to follow Yoshihisa in death by committing suicide. Thereafter, Kikuwaka devotes himself to spiritualism in an attempt to heal Yoshimasa's sadness by allowing Yoshihisa's ghost to possess his body, and eventually dies in a double-suicide with a ''miko

A , or shrine maiden,Groemer, 28. is a young priestess who works at a Shinto shrine. were once likely seen as shamans,Picken, 140. but are understood in modern Japanese culture to be an institutionalized role in daily life, trained to perform ...

'' ( 巫女, shrine maiden) who falls in love with him. Mishima wrote the story in an elegant style drawing upon medieval Japanese literature

Japan's medieval period (the Kamakura period, Kamakura, Nanbokuchō period, Nanbokuchō and Muromachi period, Muromachi periods, and sometimes the Azuchi–Momoyama period) was a transitional period for the nation's literature. Kyoto ceased being ...

and the ''Ryōjin Hishō

is an anthology of '' imayō'' 今様 songs. Originally it consisted of two collections joined together by Cloistered Emperor Go-Shirakawa: the ''Kashishū'' 歌詞集 and the ''Kudenshū'' 口伝集. The works were probably from the repertoire of ...

'', a collection of medieval ''imayō

Japanese poetry is poetry typical of Japan, or written, spoken, or chanted in the Japanese language, which includes Old Japanese, Early Middle Japanese, Late Middle Japanese, and Modern Japanese, as well as poetry in Japan which was written in th ...

'' songs. This elevated writing style and the homosexual motif suggest the germ of Mishima's later aesthetics. Later in 1948 Kawabata, who praised this work, published an autobiographical work describing his experience of falling in love for the first time with a boy two years his junior.

In 1946, Mishima began his first novel, , a story about two young members of the aristocracy drawn towards suicide. It was published in 1948, and placed Mishima in the ranks of the Second Generation of Postwar Writers. The following year, he published , a semi-autobiographical account of a young homosexual man who hides behind a mask to fit into society. The novel was extremely successful and made Mishima a celebrity at the age of 24. Around 1949, Mishima also published a literary essay about Kawabata, for whom he had always held a deep appreciation, in .

Mishima enjoyed international travel. In 1952, he took a world tour and published his travelogue as . He visited

In 1946, Mishima began his first novel, , a story about two young members of the aristocracy drawn towards suicide. It was published in 1948, and placed Mishima in the ranks of the Second Generation of Postwar Writers. The following year, he published , a semi-autobiographical account of a young homosexual man who hides behind a mask to fit into society. The novel was extremely successful and made Mishima a celebrity at the age of 24. Around 1949, Mishima also published a literary essay about Kawabata, for whom he had always held a deep appreciation, in .

Mishima enjoyed international travel. In 1952, he took a world tour and published his travelogue as . He visited Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

during his travels, a place which had fascinated him since childhood. His visit to Greece became the basis for his 1954 novel , which drew inspiration from the Greek legend

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the Cosmogony, origin and Cosmology#Metaphysical co ...

of Daphnis and Chloe

''Daphnis and Chloe'' ( el, Δάφνις καὶ Χλόη, ''Daphnis kai Chloē'') is an ancient Greek novel written in the Roman Empire, the only known work of the second-century AD Greek novelist and romance writer Longus.

Setting and style ...

.'' The Sound of Waves'', set on the small island of "Kami-shima

is an inhabited island located in Ise Bay off the east coast of central Honshu, Japan. It is administered as part of the city of Toba in Mie Prefecture.

The name of Kami-shima has alternatively been written with as or ; its present form of Kam ...

" where a traditional Japanese lifestyle continued to be practiced, depicts a pure, simple love between a fisherman and a . Although the novel became a best-seller, leftists criticized it for "glorifying old-fashioned Japanese values", and some people began calling Mishima a "fascist". Looking back on these attacks in later years, Mishima wrote, "The ancient community ethics portrayed in this novel were attacked by progressives at the time, but no matter how much the Japanese people changed, these ancient ethics lurk in the bottom of their hearts. We have gradually seen this proven to be the case."

Mishima made use of contemporary events in many of his works. , published in 1956, is a fictionalization of the burning down of the

Mishima made use of contemporary events in many of his works. , published in 1956, is a fictionalization of the burning down of the Kinkaku-ji

, officially named , is a Zen Buddhist temple in Kyoto, Japan. It is one of the most popular buildings in Kyoto, attracting many visitors annually.Bornoff, Nicholas (2000). ''The National Geographic Traveler: Japan''. National Geographic Socie ...

Buddhist temple in Kyoto

Kyoto (; Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan. Located in the Kansai region on the island of Honshu, Kyoto forms a part of the Keihanshin metropolitan area along with Osaka and Kobe. , the ci ...

in 1950 by a mentally disturbed monk.

In 1959, Mishima published the artistically ambitious novel . The novel tells the interconnected stories of four young men who represented four different facets of Mishima's personality. His athletic side appears as a boxer, his artistic side as a painter, his narcissistic, performative side as an actor, and his secretive, nihilistic side as a businessman who goes through the motions of living a normal life while practicing "absolute contempt for reality". According to Mishima, he was attempting to describe the time around 1955 in the novel, when Japan was entering into its era of high economic growth and the phrase "The postwar is over" was prevalent. Mishima explained, "''Kyōko no Ie'' is, so to speak, my research into the nihilism within me." Although the novel was well received by a small number of critics from the same generation as Mishima and sold 150,000 copies in a month, it was widely panned in broader literary circles, and was rapidly branded as Mishima's first "failed work". It was Mishima's first major setback as an author, and the book's disastrous reception came as a harsh psychological blow.

Many of Mishima's most famous and highly regarded works were written prior to 1960. However, until that year he had not written works that were seen as especially political. In the summer of 1960, Mishima became interested in the massive Anpo protests against an attempt by U.S.-backed Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi

was a Japanese bureaucrat and politician who was Prime Minister of Japan from 1957 to 1960.

Known for his exploitative rule of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in Northeast China in the 1930s, Kishi was nicknamed the "Monster of the Shō ...

to revise the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security Between the United States and Japan

The , more commonly known as the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty in English and as the or just in Japanese, is a treaty that permits the presence of U.S. military bases on Japanese soil, and commits the two nations to defend each other if one or th ...

(known as "Anpo

The , more commonly known as the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty in English and as the or just in Japanese, is a treaty that permits the presence of U.S. military bases on Japanese soil, and commits the two nations to defend each other if one or th ...

" in Japanese) in order to cement the U.S.–Japan military alliance into place. Although he did not directly participate in the protests, he often went out in the streets to observe the protestors in action and kept extensive newspaper clipping covering the protests. In June 1960, at the climax of the protest movement, Mishima wrote a commentary in the ''Mainichi Shinbun

The is one of the major newspapers in Japan, published by

In addition to the ''Mainichi Shimbun'', which is printed twice a day in several local editions, Mainichi also operates an English language news website called ''The Mainichi'' (prev ...

'' newspaper, entitled "A Political Opinion". In the critical essay, he argued that leftist groups such as the Zengakuren

Zengakuren is a league of university student associations founded in 1948 in Japan. The word is an abridgement of which literally means "All-Japan Federation of Student Self-Government Associations." Notable for organizing protests and marches, ...

student federation, the Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of th ...

, and the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A ...

were falsely wrapping themselves in the banner of "defending democracy" and using the protest movement to further their own ends. Mishima warned against the dangers of the Japanese people following ideologues who told lies with honeyed words. Although Mishima criticized Kishi as a "nihilist" who had subordinated himself to the United States, Mishima concluded that he would rather vote for a strong-willed realist "with neither dreams nor despair" than a mendacious but eloquent ideologue.

Shortly after the Anpo Protests ended, Mishima began writing one of his most famous short stories, , glorifying the actions of a young right-wing ultranationalist Japanese army officer who commits suicide after a failed revolt against the government during the February 26 Incident. The following year, he published the first two parts of his three-part play , which celebrates the actions of the 26 February revolutionaries.

Mishima's newfound interest in contemporary politics shaped his novel , also published in 1960, which so closely followed the events surrounding politician Hachirō Arita

was a Japanese politician and diplomat who served as the Minister for Foreign Affairs for three terms. He is believed to have originated the concept of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Biography

Arita was born on the island of Sado ...

's campaign to become governor of Tokyo that Mishima was sued for invasion of privacy

The right to privacy is an element of various legal traditions that intends to restrain governmental and private actions that threaten the privacy of individuals. Over 150 national constitutions mention the right to privacy. On 10 December 194 ...

. The next year, Mishima published , a parody of the classical Noh play ''Motomezuka

''Motomezuka'' () is a Noh play of the fourth category, written by Kan'ami and revised by Zeami. The name is either a corruption of, or a pun on, ''Otomezuka'' ("The Maiden's Grave"), the original story from episode 147 of ''Yamato Monogatari''. ...

'', written in the 14th-century playwright Kiyotsugu Kan'ami. In 1962, Mishima produced his most artistically avant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical ...

work , which at times comes close to science fiction. Although the novel received mixed reviews from the literary world, prominent critic Takeo Okuno singled it out for praise as part of a new breed of novels that was overthrowing longstanding literary conventions in the tumultuous aftermath of the Anpo Protests. Alongside Kōbō Abe

, pen name of , was a Japanese writer, playwright, musician, photographer, and inventor. He is best known for his 1962 novel '' The Woman in the Dunes'' that was made into an award-winning film by Hiroshi Teshigahara in 1964. Abe has often bee ...

's , published that same year, Okuno considered ''A Beautiful Star'' an "epoch-making work" which broke free of literary taboos and preexisting notions of what literature should be in order to explore the author's personal creativity.'

In 1965, Mishima wrote the play that explores the complex figure of the Marquis de Sade

Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade (; 2 June 1740 – 2 December 1814), was a French nobleman, revolutionary politician, philosopher and writer famous for his literary depictions of a libertine sexuality as well as numerous accusat ...

, traditionally upheld as an exemplar of vice, through a series of debates between six female characters, including the Marquis' wife, the Madame de Sade. At the end of the play, Mishima offers his own interpretation of what he considered to be one of the central mysteries of the de Sade story—the Madame de Sade's unstinting support for her husband while he was in prison and her sudden decision to renounce him upon his release. Mishima's play was inspired in part by his friend Tatsuhiko Shibusawa

was the pen name of Shibusawa Tatsuo, a novelist, art critic, and translator of French literature active during Shōwa period Japan. Shibusawa wrote many short stories and novels based on French literature and Japanese classics. His essays about ...

's 1960 Japanese translation of the Marquis de Sade's novel '' Juliette'' and a 1964 biography Shibusawa wrote of de Sade. Shibusawa's sexually explicit translation became the focus of a sensational obscenity trial remembered in Japan as the "Sade Case" (サド裁判, Sado saiban), which was ongoing as Mishima wrote the play. In 1994, ''Madame de Sade'' was evaluated as the "greatest drama in the history of postwar theater" by Japanese theater criticism magazine ''Theater Arts

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perform ...

''.

Mishima was considered for the Nobel Prize for Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901

, ...

in 1963, 1964, and 1965, and was a favorite of many foreign publications. However, in 1968 his early mentor Kawabata won the Nobel Prize and Mishima realized that the chances of it being given to another Japanese author in the near future were slim. In a work published in 1970, Mishima wrote that the writers he paid most attention to in modern western literature were Georges Bataille

Georges Albert Maurice Victor Bataille (; ; 10 September 1897 – 9 July 1962) was a French philosopher and intellectual working in philosophy, literature, sociology, anthropology, and history of art. His writing, which included essays, novels, ...

, Pierre Klossowski

Pierre Klossowski (; ; 9 August 1905 – 12 August 2001) was a French writer, translator and artist. He was the eldest son of the artists Erich Klossowski and Baladine Klossowska, and his younger brother was the painter Balthus.

Life

Born in Par ...

, and Witold Gombrowicz

Witold Marian Gombrowicz (August 4, 1904 – July 24, 1969) was a Polish writer and playwright. His works are characterised by deep psychological analysis, a certain sense of paradox and absurd, anti-nationalist flavor. In 1937 he published his f ...

.

Acting and modelling

Mishima was also an actor, and starred inYasuzo Masumura

was a Japanese film director.

Biography

Masumura was born in Kōfu, Yamanashi. After dropping out of a law course at the University of Tokyo he worked as an assistant director at the Daiei Film studio, later returning to university to study ph ...

's 1960 film, , for which he also sang the theme song (lyrics by himself; music by Shichirō Fukazawa

was a Japanese author and guitarist whose 1960 short story ''Fūryū mutan'' ("Tale of an Elegant Dream") caused a nationwide uproar and led to an attempt by an ultranationalist to assassinate the president of the magazine that published it.

B ...

). He performed in films like , and .

Mishima was featured as the photo model in photographer Eikoh Hosoe

is a Japanese photographer and filmmaker who emerged in the experimental arts movement of post-World War II Japan. Hosoe is best known for his dark, high contrast, black and white photographs of human bodies. His images are often psychologicall ...

's book , as well as in Tamotsu Yatō

was a Japanese photographer and occasional actor responsible for pioneering Japanese homoerotic photography and creating iconic black-and-white images of the Japanese male.

Biography

Yato was born in Nishinomiya in 1928 as Tamotsu Takeda. He wa ...

's photobooks and . American author Donald Richie

Donald Richie (17 April 1924 – 19 February 2013) was an American-born author who wrote about the Japanese people, the culture of Japan, and especially Japanese cinema. Although he considered himself primarily a film historian, Richie also dir ...

gave an eyewitness account of seeing Mishima, dressed in a loincloth and armed with a sword, posing in the snow for one of Tamotsu Yatō's photoshoots.

In the men's magazine '' Heibon Punch'', to which Mishima had contributed various essays and criticisms, he won first place in the "Mr. Dandy" reader popularity poll in 1967 with 19,590 votes, beating second place Toshiro Mifune

was a Japanese actor who appeared in over 150 feature films. He is best known for his 16-film collaboration (1948–1965) with Akira Kurosawa in such works as ''Rashomon'', ''Seven Samurai'', ''The Hidden Fortress'', ''Throne of Blood'', and '' ...

by 720 votes.

In the next reader popularity poll, "Mr. International", Mishima ranked second behind French President Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

. At that time in the late 1960s, Mishima was the first celebrity to be described as a "superstar" (''sūpāsutā'') by the Japanese media.

Private life

weight training

Weight training is a common type of strength training for developing the strength, size of skeletal muscles and maintenance of strength.Keogh, Justin W, and Paul W Winwood. “Report for: The Epidemiology of Injuries Across the Weight-Traini ...

to overcome an inferiority complex about his weak constitution, and his strictly observed workout regimen of three sessions per week was not disrupted for the final 15 years of his life. In his 1968 essay , Mishima deplored the emphasis given by intellectuals to the mind over the body. He later became very skilled ( 5th Dan) at kendo

is a modern Japanese martial art, descended from kenjutsu (one of the old Japanese martial arts, swordsmanship), that uses bamboo swords (shinai) as well as protective armor (bōgu). Today, it is widely practiced within Japan and has spread ...

(traditional Japanese swordsmanship), and became 2nd Dan in battōjutsu

("the craft of drawing out the sword") is an old term for iaijutsu (居合術). Battōjutsu is often used interchangeably with the terms ''iaijutsu'' and ''battō'' (抜刀).Armstrong, Hunter B. (1995) "The Koryu Bujutsu Experience" in ''Koryu B ...

, and 1st Dan in karate

(; ; Okinawan language, Okinawan pronunciation: ) is a martial arts, martial art developed in the Ryukyu Kingdom. It developed from the Okinawan martial arts, indigenous Ryukyuan martial arts (called , "hand"; ''tii'' in Okinawan) under the ...

. In 1956, he tried boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

for a short period of time. In the same year, he developed an interest in UFO

An unidentified flying object (UFO), more recently renamed by US officials as a UAP (unidentified aerial phenomenon), is any perceived aerial phenomenon that cannot be immediately identified or explained. On investigation, most UFOs are id ...

s and became a member of the . In 1954, he fell in love with , who became the model for main characters in and . Mishima hoped to marry her, but they broke up in 1957.

After briefly considering marriage with , who later married Crown Prince Akihito

is a member of the Imperial House of Japan who reigned as the 125th emperor of Japan from 7 January 1989 until his abdication on 30 April 2019. He presided over the Heisei era, ''Heisei'' being an expression of achieving peace worldwide.

Bor ...

and became Empress Michiko, Mishima married , the daughter of Japanese-style painter , on 1 June 1958. The couple had two children: a daughter named (born 2 June 1959) and a son named (born 2 May 1962). Noriko eventually married the diplomat .

While working on his novel , Mishima visited gay bars in Japan. Mishima's sexual orientation was an issue that bothered his wife, and she always denied his homosexuality after his death. In 1998, the writer published an account of his relationship with Mishima in 1951, including fifteen letters (not love letters) from the famed novelist. Mishima's children successfully sued Fukushima and the publisher for copyright violation over the use of Mishima's letters. Publisher ''Bungeishunjū

is a Japanese publishing company known for its leading monthly magazine ''Bungeishunjū''. The company was founded by Kan Kikuchi in 1923. It grants the annual Akutagawa Prize, one of the most prestigious literary awards in Japan, as well as th ...

'' had argued that the contents of the letters were "practical correspondence" rather than copyrighted works. However, the ruling for the plaintiffs declared, "In addition to clerical content, these letters describe the Mishima's own feelings, his aspirations, and his views on life, in different words from those in his literary works."

In February 1961, Mishima became embroiled in the aftermath of the . In 1960, the author had published the satirical short story in the mainstream magazine ''Chūō Kōron

is a monthly Japanese literary magazine (), first established during the Meiji period and continuing to this day. It is published by its namesake-bearing Chūōkōron Shinsha (formerly Chūōkōron-sha). The headquarters is in Tokyo.

''Chūō ...

''. It contained a dream sequence (in which the Emperor and Empress are beheaded by a guillotine) that led to outrage from right-wing ultra-nationalist groups, and numerous death threats against Fukazawa, any writers believed to have been associated with him, and ''Chūō Kōron'' magazine itself. On 1 February 1961, , a seventeen-year-old rightist, broke into the home of , the president of ''Chūō Kōron'', killed his maid with a knife and severely wounded his wife. In the aftermath, Fukazawa went into hiding, and dozens of writers and literary critics, including Mishima, were provided with round-the-clock police protection for several months; Mishima was included because a rumor that Mishima had personally recommended "The Tale of an Elegant Dream" for publication became widespread, and even though he repeatedly denied the claim, he received hundreds of death threats. In later years, Mishima harshly criticized Komori, arguing that those who harm women and children are neither patriots nor traditional right-wingers, and that an assassination attempt should be a one-on-one confrontation with the victim at the risk of the assassin's life. Mishima also argued that it was the custom of traditional Japanese patriots to immediately commit suicide after committing an assassination. collected in

In 1963, the ''Harp of Joy Incident'' occurred within the theatrical troupe , to which Mishima belonged. He wrote a play titled , but star actress and other Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A ...

-affiliated actors refused to perform because the protagonist held anti-communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

views and mentioned criticism about a conspiracy of world communism

World communism, also known as global communism, is the ultimate form of communism which of necessity has a universal or global scope. The long-term goal of world communism is an unlimited worldwide communist society that is classless (lacking ...

in his lines. As a result of this ideological conflict, Mishima quit ''Bungakuza'' and later formed the troupe with playwrights and actors who had quit Bungakuza along with him, including , , and . When ''Neo Littérature Théâtre'' experienced a schism in 1968, Mishima formed another troupe, the , and worked with Matsuura and Nakamura again.

During the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, Mishima interviewed various athletes every day and wrote articles as a newspaper correspondent. He had eagerly anticipated the long-awaited return of the Olympics to Japan after the 1940 Tokyo Olympics were cancelled due to Japan's war in China. Mishima expressed his excitement in his report on the opening ceremonies: "It can be said that ever since Lafcadio Hearn

, born Patrick Lafcadio Hearn (; el, Πατρίκιος Λευκάδιος Χέρν, Patríkios Lefkádios Chérn, Irish language, Irish: Pádraig Lafcadio O'hEarain), was an Irish people, Irish-Greeks, Greek-Japanese people, Japanese writer, t ...

called the Japanese "the Greeks of the Orient," the Olympics were destined to be hosted by Japan someday."

Mishima hated Ryokichi Minobe

was a Japanese politician who served as Governor of Tokyo from 1967 to 1979. He is one of the best known socialist figures in modern Japanese history.

Early life

Minobe was born in Tokyo. His father, Tatsukichi Minobe, was a noted constitutional ...

, who was a communist and the governor of Tokyo beginning in 1967. Influential persons in the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), including Takeo Fukuda

was a Japanese politician who was Prime Minister of Japan from 1976 to 1978.

Early life and education

Fukuda was born in Gunma, capital of the Gunma Prefecture on 14 January 1905. He hailed from a former samurai family and his father was mayor ...

and Kiichi Aichi

was a Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture ...

, had been Mishima's superiors during his time at the Ministry of the Treasury

The (lit. the department of the great treasury) was a division of the eighth-century Japanese government of the Imperial Court in Kyoto, instituted in the Asuka period and formalized during the Heian period. The Ministry was replaced in the Mei ...

, and Prime Minister Eisaku Satō

was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister from 1964 to 1972. He is the third-longest serving Prime Minister, and ranks second in longest uninterrupted service as Prime Minister.

Satō entered the National Diet in 1949 as a membe ...

came to know Mishima because his wife, Hiroko, was a fan of Mishima's work. Based on these connections LDP officials solicited Mishima to run for the LDP as governor of Tokyo against Minobe, but Mishima had no intention of becoming a politician.

Mishima was fond of manga

Manga (Japanese: 漫画 ) are comics or graphic novels originating from Japan. Most manga conform to a style developed in Japan in the late 19th century, and the form has a long prehistory in earlier Japanese art. The term ''manga'' is u ...

and gekiga

, literally "dramatic pictures", is a style of Japanese comics aimed at adult audiences and marked by a more cinematic art style and more mature themes. ''Gekiga'' was the predominant style of adult comics in Japan in the 1960s and 1970s. It is ...

, especially the drawing style of , a mangaka

A is a comic artist who writes and/or illustrates manga. As of 2006, about 3,000 professional manga artists were working in Japan.

Most manga artists study at an art college or manga school or take on an apprenticeship with another artist bef ...

best known for his samurai gekiga; the slapstick, absurdist comedy in Fujio Akatsuka

was a pioneer Japanese artist of comical manga known as the Gag Manga King. His name at birth is 赤塚 藤雄, whose Japanese pronunciation is the same as 赤塚 不二夫.

He was born in Rehe, Manchuria, the son of a Japanese military pol ...

's , and the imaginativeness of Shigeru Mizuki

was a Japanese manga artist and historian, best known for his manga series ''GeGeGe no Kitarō''. Born in a hospital in Osaka and raised in the city of Sakaiminato, Tottori, he later moved to Chōfu, Tokyo where he remained until his death. ...

's . collected in collected in Mishima especially loved reading the boxing manga in ''Weekly Shōnen Magazine

is a weekly ''shōnen'' manga anthology published on Wednesdays in Japan by Kodansha, first published on March 17, 1959. The magazine is mainly read by an older audience, with a significant portion of its readership falling under the male high ...

'' every week. ''Ultraman

''Ultraman'', also known as the , is the collective name for all media produced by Tsuburaya Productions featuring Ultraman, his many brethren, and the myriad monsters. Debuting with ''Ultra Q'' and then ''Ultraman'' in 1966, the series is one ...

'' and ''Godzilla

is a fictional monster, or '' kaiju'', originating from a series of Japanese films. The character first appeared in the 1954 film ''Godzilla'' and became a worldwide pop culture icon, appearing in various media, including 32 films produc ...

'' were his favorite kaiju

is a Japanese media genre that focuses on stories involving giant monsters. The word ''kaiju'' can also refer to the giant monsters themselves, which are usually depicted attacking major cities and battling either the military or other monster ...

fantasies, and he once compared himself to "Godzilla's egg" in 1955. On the other hand, he disliked story manga

Osamu Tezuka (, born , ''Tezuka Osamu''; – 9 February 1989) was a Japanese manga artist, cartoonist, and animator. Born in Osaka Prefecture, his prolific output, pioneering techniques, and innovative redefinitions of genres earned him such ...

with humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humani ...

or cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan may refer to:

Food and drink

* Cosmopolitan (cocktail), also known as a "Cosmo"

History

* Rootless cosmopolitan, a Soviet derogatory epithet during Joseph Stalin's anti-Semitic campaign of 1949–1953

Hotels and resorts

* Cosmopoli ...

themes, such as Osamu Tezuka

Osamu Tezuka (, born , ''Tezuka Osamu''; – 9 February 1989) was a Japanese manga artist, cartoonist, and animator. Born in Osaka Prefecture, his prolific output, pioneering techniques, and innovative redefinitions of genres earned him such ...

's .

Mishima was a fan of science fiction, contending that "science fiction will be the first literature to completely overcome modern humanism". He praised Arthur C. Clarke's ''Childhood's End

''Childhood's End'' is a 1953 science fiction novel by the British author Arthur C. Clarke. The story follows the peaceful alien invasionBooker & Thomas 2009, pp. 31–32. of Earth by the mysterious Overlords, whose arrival begins decade ...

'' in particular. While acknowledging "inexpressible unpleasant and uncomfortable feelings after reading it," he declared, "I'm not afraid to call it a masterpiece."

Mishima traveled to Shimoda on the Izu Peninsula

The is a large mountainous peninsula with a deeply indented coastline to the west of Tokyo on the Pacific coast of the island of Honshu, Japan. Formerly known as Izu Province, Izu peninsula is now a part of Shizuoka Prefecture. The peninsul ...

with his wife and children every summer from 1964 onwards. In Shimoda, Mishima often enjoyed eating local seafood with his friend Henry Scott-Stokes

Henry Scott-Stokes (15 June 1938 – 19 April 2022) was a British journalist who was the Tokyo bureau chief for ''Financial Times, The Financial Times'' (1964–67), ''The Times'' (1967-1970s?), and ''The New York Times'' (1978–83).

He w ...