Timeline of United States diplomatic history on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

* 1807 – US Navy humiliated by Royal Navy in ''Chesapeake–Leopard'' affair; demand for war; Jefferson responds with economic warfare using embargoes

* 1807–09 –

* 1807 – US Navy humiliated by Royal Navy in ''Chesapeake–Leopard'' affair; demand for war; Jefferson responds with economic warfare using embargoes

* 1807–09 –

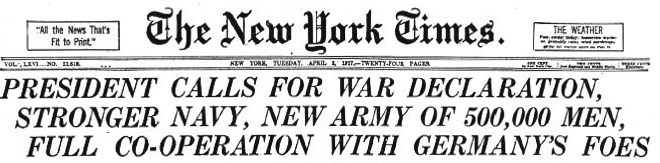

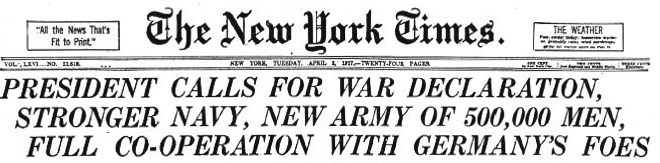

* 1917 – April. America declares war on Germany and later on Austria (but not

* 1917 – April. America declares war on Germany and later on Austria (but not

''The National Interest'' (Nov–Dec. 2017) Issue 152, pp 58–68

* 2009 – President

excerpt and text search

* Anderson, Frank Maloy and Amos Shartle Hershey, eds. ''Handbook For The Diplomatic History Of Europe, Asia, and Africa, 1870–1914'' (1918

online

* Bailey, Thomas A. ''A Diplomatic History of the American People'' (10th edition 1980

online free to borrow

* Beisner, Robert L. ed, ''American Foreign Relations since 1600: A Guide to the Literature'' (2003), 2 vol. 16,300 annotated entries evaluate every major book and scholarly article. * Bemis, Samuel Flagg. ''A Diplomatic History of the United States'' (2nd ed. 1942

online

old standard textbook * Bemis, Samuel Flagg and Grace Gardner Griffin. ''Guide to the Diplomatic History of the United States 1775–1921'' (1935) bibliographies; out of date and replaced by Beisner (2003) * Blume, Kenneth J. ''Historical Dictionary of U.S. Diplomacy from the Civil War to World War I'' (2005) * Brune, Lester H. ''Chronological History of U.S. Foreign Relations'' (2003), 1400 pages * Burns, Richard Dean, ed. ''Guide to American Foreign Relations since 1700'' (1983) highly detailed annotated bibliography * Deconde, Alexander, et al. eds. ''Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy'' 3 vol (2001), 2200 pages; 120 long articles by specialists. * DeConde, Alexander; ''A History of American Foreign Policy'' (1963)

online edition

* Ellis, Sylvia. ''Historical Dictionary of Anglo-American Relations'' (2009)

Excerpt and text search

* Findling, John, ed. ''Dictionary of American Diplomatic History'' 2nd ed. 1989. 700pp; 1200 short articles. * Folly, Martin and Niall Palmer. ''The A to Z of U.S. Diplomacy from World War I through World War II'' (2010

excerpt and text search

* Herring, George. ''From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776'' (Oxford History of the United States) (2008), 1056pp * Hahn, Peter L. ''Historical Dictionary of United States-Middle East Relations'' (2007

excerpt and text search

* Hogan, Michael J. ed. ''Paths to Power: The Historiography of American Foreign Relations to 1941'' (2000) essays on main topics * Hogan, Michael J., and Thomas G. Paterson, eds. ''Explaining the History of American Foreign Relations'' (1991) essays on historiography * Hollowell, Jonathan. ''Twentieth-Century Anglo-American Relations'' (2001) * Lafeber, Walter. '' The American Age: United States Foreign Policy at Home and Abroad, 1750 to Present'' (2nd ed 1994) university textbook; 884p

online edition

* Leffler, Melvyn P. ''Safeguarding Democratic Capitalism: U.S. Foreign Policy and National Security, 1920–2015'' (Princeton University Press, 2017) 348 pp. * Mauch, Peter, and Yoneyuki Sugita. ''Historical Dictionary of United States-Japan Relations'' (2007)

Excerpt and text search

* Paterson, Thomas, et al. ''American Foreign Relations: A History'' (7th ed. 2 vol. 2009), university textbook * Plummer, Brenda Gayle. “The Changing Face of Diplomatic History: A Literature Review.” ''History Teacher'' 38#3 (2005), pp. 385–400

online

* Saul, Norman E. ''Historical Dictionary of United States-Russian/Soviet Relations'' (2008

excerpt and text search

* Smith, Joseph. ''Historical Dictionary of United States-Latin American Relations'' (2006

excerpt and text search

* Sutter, Robert G. ''Historical Dictionary of United States-China Relations'' (2005

excerpt and text search

* Waters, Robert Anthony, Jr. ''Historical Dictionary of United States-Africa Relations'' (2009

Excerpt and text search

* Weatherbee, Donald E. ''Historical Dictionary of United States-Southeast Asia Relations'' (2008

Excerpt and text search

“U.S. Diplomatic History Resources Index"

sponsored by the

recommended by ''The Washington Post,'' Oct. 8, 1998

{{DEFAULTSORT:Timeline Of United States Diplomatic History History of the foreign relations of the United States

diplomatic history

Diplomatic history deals with the history of international relations between states. Diplomatic history can be different from international relations in that the former can concern itself with the foreign policy of one state while the latter deals ...

of the United States oscillated among three positions: isolation from diplomatic entanglements of other (typically European) nations (but with economic connections to the world); alliances with European and other military partners; and unilateralism

__NOTOC__

Unilateralism is any doctrine or agenda that supports one-sided action. Such action may be in disregard for other parties, or as an expression of a commitment toward a direction which other parties may find disagreeable. As a word, ''un ...

, or operating on its own sovereign policy decisions. The US always was large in terms of area, but its population was small, only 4 million in 1790. Population growth was rapid, reaching 7.2 million in 1810, 32 million in 1860, 76 million in 1900, 132 million in 1940, and 316 million in 2013. Economic growth in terms of overall GDP was even faster. However, the nation's military strength was quite limited in peacetime before 1940.

Brune (2003) and Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., ed. ''The Almanac of American History'' (1983) have specifics for many incidents.

18th century

* 1721 – Treaty with South Carolina established with theCherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

and the Province of South Carolina

Province of South Carolina, originally known as Clarendon Province, was a province of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the thirteen American colonies. The monar ...

which ceded land between the Santee, Saluda, and Edisto Rivers to the Province of South Carolina

Province of South Carolina, originally known as Clarendon Province, was a province of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the thirteen American colonies. The monar ...

.

* 1727 – Treaty of Nikwasi established a trade agreement between the Cherokee and the Province of North Carolina

Province of North Carolina was a province of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712(p. 80) to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the thirteen American colonies. The monarch of Great Britain was repre ...

*1754 – In response to disputes between the Province of New York

The Province of New York (1664–1776) was a British proprietary colony and later royal colony on the northeast coast of North America. As one of the Middle Colonies, New York achieved independence and worked with the others to found the U ...

and the Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

proposes the Albany Plan of Union

The Albany Plan of Union was a rejected plan to create a unified government for the Thirteen Colonies at the Albany Congress on July 10, 1754 in Albany, New York. The plan was suggested by Benjamin Franklin, then a senior leader (age 48) and a del ...

, which would establish a federal government

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government ( federalism). In a federation, the self-gover ...

for eleven of the colonies in British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

to adjudicate colonial territorial disputes and diplomatic policy towards Native Americans; it is rejected by most of the colonial governments.

*1761 – Treaty of Long-Island-on-the-Holston

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pe ...

established with the Cherokee and the Colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertGilbert (Saunders Family), Sir Humphrey" (histor ...

which ended the Anglo-Cherokee war

The Anglo-Cherokee War (1758–1761; in the Cherokee language: the ''"war with those in the red coats"'' or ''"War with the English"''), was also known from the Anglo-European perspective as the Cherokee War, the Cherokee Uprising, or the Cherok ...

with the colony.

* 1762 – Treaty of Charlestown

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

established with the Cherokee and the Province of South Carolina

Province of South Carolina, originally known as Clarendon Province, was a province of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the thirteen American colonies. The monar ...

which ended the Anglo-Cherokee war with the colony.

*1774 – The Thirteen Colonies convene the First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from 12 of the 13 British colonies that became the United States. It met from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, after the British Nav ...

and adopt a boycott of British goods and embargo on American exports in protest of the Intolerable Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measur ...

.

*1775 – Regular troops of the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

and minutemen

Minutemen were members of the organized New England colonial militia companies trained in weaponry, tactics, and military strategies during the American Revolutionary War. They were known for being ready at a minute's notice, hence the name. Mi ...

of colonial militias exchange fire at the Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, ...

, beginning the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

.

*1775 – The Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

sends the Olive Branch Petition

The Olive Branch Petition was adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 5, 1775, and signed on July 8 in a final attempt to avoid war between Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies in America. The Congress had already authorized the i ...

to King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

pleading their loyalty to the British Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

; it is ignored and the King issues the Proclamation of Rebellion

The Proclamation of Rebellion, officially titled A Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition, was the response of George III to the news of the Battle of Bunker Hill at the outset of the American Revolution. Issued on 23 August 1775, ...

.

* 1776 – Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centu ...

declared independence as the United States of America on July 2; Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

adopted on July 4

* 1776 – Three commissioners sent to Europe to negotiate treaties. The British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

bans trade with the Thirteen Colonies, and the Second Continental Congress responds by opening American ports to all foreign vessels except from Great Britain. The Second Continental Congress also adopts the Model Treaty as a template for any future trade agreements with European countries such as France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

.

* 1776 – Treaty of Watertown, the first treaty by the independent United States, is signed establishing a military alliance with the Miꞌkmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the n ...

.

* 1777 – European officers recruited to Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

, including Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

, Johann de Kalb

Johann von Robais, Baron de Kalb (June 19, 1721 – August 19, 1780), born Johann Kalb, was a Franconian-born French military officer who served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He was mortally ...

, Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben

Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand von Steuben (born Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Louis von Steuben; September 17, 1730 – November 28, 1794), also referred to as Baron von Steuben (), was a Prussian military officer who ...

, and Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko ( be, Andréj Tadévuš Banavientúra Kasciúška, en, Andrew Thaddeus Bonaventure Kosciuszko; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish military engineer, statesman, and military leader who ...

* 1777 – Treaty of Dewitt's Corner between the Overhill Cherokee

Overhill Cherokee was the term for the Cherokee people located in their historic settlements in what is now the U.S. state of Tennessee in the Southeastern United States, on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains. This name was used by 1 ...

and the State of South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

which ceded the lands of the Cherokee Lower Towns in the State of South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, except for a narrow strip of what is now Oconee County.

* 1777 – France decides to recognize America in December after victory

The term victory (from Latin ''victoria'') originally applied to warfare, and denotes success achieved in personal combat, after military operations in general or, by extension, in any competition. Success in a military campaign constitutes ...

at Saratoga, New York

}

Saratoga is a town in Saratoga County, New York, United States. The population was 5,141 at the 2000 census. It is also the commonly used, but not official, name for the neighboring and much more populous city, Saratoga Springs. The major vill ...

* 1778 – Treaty of Alliance with France. Negotiated by Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

, the US and France agreed to a military alliance; France sends naval and land forces, and much-needed munitions.

* 1778 – Carlisle Peace Commission

The Carlisle Peace Commission was a group of British peace commissioners who were sent to North America in 1778 to negotiate terms with the rebellious Continental Congress during the American Revolutionary War. The commission carried an offer of ...

sent by Great Britain; offers Americans all the terms they sought in 1775, but not independence; rejected.

* 1779 – Spain enters the war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

as an ally of France (but not of America); John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the f ...

appointed minister to Spain; he obtains money but not recognition.

* 1779 – John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

sent to Paris, to negotiate peace terms with Great Britain

* 1780 – Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

proclaims "armed neutrality" which helps Allies

* 1780–81 – Russia and Austria propose peace terms; rejected by Adams.

* 1781 – Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

, Henry Laurens and Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

named to assist Adams in peace negotiations; the Congress of the Confederation

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America during the Confederation period, March 1, 1781 – Mar ...

insists on independence; all else is negotiable

:— Robert R. Livingston

Robert Robert Livingston (November 27, 1746 (Old Style November 16) – February 26, 1813) was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat from New York, as well as a Founding Father of the United States. He was known as "The Chancellor", afte ...

named first United States Secretary of Foreign Affairs

This is a list of secretaries of state of the United States.

Secretaries of foreign affairs (1781–1789)

On January 10, 1780, the Confederation Congress created the Department of Foreign Affairs.

On August 10, 1781, Congress selected Robert ...

:— Under French diplomatic pressure Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

ratifies the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

, creating the first federal government for the United States.

* 1782 – The Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

recognizes American independence and signs treaty of commerce and friendship; Dutch bankers loan US$2 million for war supplies

* 1783 – Treaty of Paris ends Revolutionary War; US boundaries confirmed as British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

(Canada) on north, Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

on west, Florida on south. Britain gives Florida to Spain.

* 1783 – A commercial treaty with Sweden

* 1784 – British allow trade with America but forbid some American food exports to West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

; British exports to America reach £3.7 million, imports only £750,000; imbalance causes shortage of gold in US.

:— May 7 Congress votes to begin negotiations with Morocco.Fremont-Barnes, Gregory ''The Wars of the Barbary Pirates'', London: Osprey, 2006 page 13

:— New York–based merchants open trade with China, followed by Salem, Boston and Philadelphia merchants.

:— October 11 Moroccan corsair seizes the American ship ''Betsey'' and enslaves the crew; the Moroccans demand that the US pay a ransom to release the crew and a treaty to pay tribute to avoid future such incidents.

* 1784 – Treaty of Fort Stanwix

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix was a treaty signed between representatives from the Iroquois and Great Britain (accompanied by negotiators from New Jersey, Virginia and Pennsylvania) in 1768 at Fort Stanwix. It was negotiated between Sir William ...

in which the Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

cedes all lands west of the Niagara River to the United States.

* 1785 – Treaty of Hopewell

* 1785 – Adams appointed first minister to Court of St James's

The Court of St James's is the royal court for the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. All ambassadors to the United Kingdom are formally received by the court. All ambassadors from the United Kingdom are formally accredited from the court – ...

(Great Britain); Jefferson replaces Franklin as minister to France.

:— March 11 Congress votes to appropriate $80,000 to pay in tribute to the Barbary states of Morocco, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli.

:— July 9 The Moroccans release the ''Betsy'' and her crew.

:— July 25 Algerine pirates seizes the American ship ''Maria'' off the coast of Portugal; Algiers declares war on the US, and the ''dey'' Muhammad V of Algiers demands that the US pay $1 million in tribute to end the war.

* 1785–86 – A commercial treaty with Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

* 1786 – Treaty of Coyatee

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

established between the Overhill Cherokee and the State of Franklin

The State of Franklin (also the Free Republic of Franklin or the State of Frankland)Landrum, refers to the proposed state as "the proposed republic of Franklin; while Wheeler has it as ''Frankland''." In ''That's Not in My American History Boo ...

. Signed at gunpoint, this treaty ceded the remaining Cherokee land north and east of the Little Tennessee River

The Little Tennessee River is a tributary of the Tennessee River that flows through the Blue Ridge Mountains from Georgia, into North Carolina, and then into Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. It drains portions of three national ...

to the ridge dividing it from Little River.

:— March 25 A team of American diplomats arrive in Algiers to begin talks on paying tribute and a ransom to free the enslaved American sailors.

:— June 23 Moroccan-American treaty is signed in the US agrees to pay tribute to Morocco in exchange for a promise that Moroccan corsairs will not attack American ships.

* 1789 – Jay–Gardoqui Treaty with Spain, gave Spain exclusive right to navigate Mississippi River for 25 years; not ratified due to western opposition

:— March 1 United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

succeeds Congress of the Confederation

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America during the Confederation period, March 1, 1781 – Mar ...

:— July 27 Department of Foreign Affairs signed into law

:— September, changed to Department of State; Jefferson appointed; John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the f ...

continues to act as foreign affairs secretary until Jefferson's return from France; from 1789 to 1883. Much of the routine overseas business is the responsibility of navy officers.

* 1789 – Treaty of Fort Harmar

The Treaty of Fort Harmar (1789) was an agreement between the United States government and numerous Native American tribes with claims to the Northwest Territory.

History

The Treaty of Fort Harmar was signed at Fort Harmar, near present-day ...

* 1791 – Treaty of Holston

The Treaty of Holston (or Treaty of the Holston) was a treaty between the United States government and the Cherokee signed on July 2, 1791, and proclaimed on February 7, 1792. It was negotiated and signed by William Blount, governor of the South ...

*1791 – In response to the beginning of the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt began on ...

, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

proposes limited aid to help suppress the revolt but also pressures the French government to reach a settlement with the Haitian revolutionaries.

* 1792

:— February 22 Congress votes to send another team of diplomats to Algiers to pay a ransom for the enslaved Americans and to negotiate a tribute treaty.

* 1793–1815 – Major worldwide war between Great Britain and France (and their allies); America neutral until 1812 and does business with both sides

* 1794 -:— March 20 Congress votes to establish a navy and to spend $1 million building six frigates. Birth of the United States Navy.

*1794 — The United States expels French Ambasssador Edmond-Charles Genêt

Edmond-Charles Genêt (January 8, 1763July 14, 1834), also known as Citizen Genêt, was the French envoy to the United States appointed by the Girondins during the French Revolution. His actions on arriving in the United States led to a major po ...

for his attempts to recruit privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s in violation of U.S. neutrality policy.

* 1795 –

:— June 24 Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

with Britain. Averts war, opens 10 years of peaceful trade with Britain, fails to settle neutrality issues; British eventually evacuate western forts; boundary lines and debts (in both directions) to be settled by arbitration. Barely approved by Senate (1795) after revision; intensely opposed, became major issue in the formation of First Party System

The First Party System is a model of American politics used in history and political science to periodize the political party system that existed in the United States between roughly 1792 and 1824. It featured two national parties competing for ...

.

:— September 5 United States signs a treaty agreeing to pay tribute to Algiers in exchange for which the ''dey'' Ali Hassan will free the 85 surviving American slaves. The treaty with Algiers is considered a national humiliation.

* 1796 – Treaty of Colerain

* 1796 – Treaty of Madrid established boundaries with the Spanish colonies of Florida and Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

and guaranteed navigation rights on the Mississippi River. It becomes law.

:— July 11 Algiers frees the 85 American slaves.

:— The pasha Yusuf Karamanli of Tripoli, hoping for a similar treaty that Algiers has achieved starts attacking and seizing American ships.

:— President George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

, preparing to leave office and troubled by the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Pruss ...

in Europe, issues his famous Farewell Address urging Americans to avoid involvement in foreign wars, beginning a century of isolationism

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entangl ...

as the predominant foreign policy of the United States.

* 1797 –

:— President Adams asks Congress to spend more money on the navy and to arm American merchantmen in response to the Barbary pirate attacks.

:— August 28 Treaty of Tripoli

The Treaty of Tripoli (''Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the United States of America and the Bey and Subjects of Tripoli of Barbary'') was signed in 1796. It was the first treaty between the United States and Tripoli (now Libya) to secur ...

; treaty with Barbary state of Tripoli approved unanimously by Senate and signed into law by President John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

on June 10; states "the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion."

* First Treaty of Tellico

The Treaty With The Cherokee, 1798, also known as the First Treaty of Tellico, was signed on October 2, 1798, in the Overhill Cherokee settlement of Great Tellico near Tellico Blockhouse in Tennessee. This treaty served as an addendum to the T ...

with the Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation ( Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. ...

* 1798 – XYZ Affair

The XYZ Affair was a political and diplomatic episode in 1797 and 1798, early in the presidency of John Adams, involving a confrontation between the United States and Republican France that led to the Quasi-War. The name derives from the subs ...

; humiliation by French diplomats; threat of war with France

* 1798–1800 – Quasi-War

The Quasi-War (french: Quasi-guerre) was an undeclared naval war fought from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States. The ability of Congress ...

; undeclared naval war with France.

* 1800 –

:— April Tripoli threatens war if the US does not pay more tribute.Fremont-Barnes, Gregory ''The Wars of the Barbary States'', London: Osprey, 2006 page 14.

:— July The Tripolitan warship ''Tripolino'' takes the American merchantman ''Catherine'' and enslaves the crew. Much outrage in the US

:— September 30 Convention of 1800 (Treaty of Mortefontaine)

The Convention of 1800, also known as the Treaty of Mortefontaine, was signed on September 30, 1800, by the United States of America and France. The difference in name was due to Congressional sensitivity at entering into treaties, due to dispute ...

with France ends the Quasi-War and ends alliance of 1778. The treaty frees up the US Navy for operations against the Barbary pirates.

19th century

* Early 19th century – The Barbary states ofAlgiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques d ...

, Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

, Tripoli, and Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

require America to pay protection money under the Barbary treaties.

* 1801–

The beginning of the First Barbary War. President Jefferson does not ask Congress for a declaration of war against Tripoli, but instead decides to begin military operations against Tripoli, arguing that the President has the right to begin military operations in self-defense without asking for permission from Congress.

:— July 24 An American naval squadron begins the blockade of Tripoli.

:— August 1 The U.S.S. ''Enterprise'' takes the Tripolitan ship ''Tripoli''.

1802 –

:— April 18 Second American naval squadron sent to the Mediterranean.

:— June 19 Morocco declares war on the United States.

* 1803 – Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or ap ...

from France for $15,000,000; financed by sale of American bonds in London, and shipment of gold from London to Paris.

:— June 2 Captain David Porter leads raid into Tripoli; first American amphibious landing in the Old World.

* 1805

:— February 23 The American diplomat William Eaton William Eaton or Bill Eaton may refer to:

* William Eaton (soldier) (1764–1811), United States Army soldier during the Barbary Wars

* William Eaton (athlete) (1909–1938), British long-distance runner

* William Eaton (guitarist), American luth ...

meets with Hamet Karanmanli, the exiled brother of the pasha Yusuf Karamanli of Tripoli in Egypt and agrees that the US will depose Yusuf and put Hamet on the throne; the first American effort at "regime change".

:— March 8 A force of American sailors, marines, Tripolian exiles and Egyptian mercenaries under the leadership of Eaton leaves Alexandria with the aim of deposing pasha Yusuf of Tripoli.

:— April 28 Eaton's force takes Derna, the road is wide open to Tripoli.Fremont-Barnes, Gregory ''The Wars of the Barbary States'', London: Osprey, 2006 page 15.

:— June 4 Tripoli and the US sign a peace treaty.

* 1806 – Essex Case; British reverse policy and seize American ships trading with French colonies; America responds with Non-Importation Act stopping imports of some items from Great Britain

* 1806 – Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

issues Berlin Decree

The Berlin Decree was issued in Berlin by Napoleon on November 21, 1806, after the French success against Prussia at the Battle of Jena, which led to the Fall of Berlin (1806), Fall of Berlin. The decree was issued in response to the British Order- ...

, a paper blockade of Great Britain

* 1806 – diplomats negotiate treaty with Britain to extend the expiring Jay Treaty; rejected by Jefferson and never in effect as relations deteriorate

* 1807 – US Navy humiliated by Royal Navy in ''Chesapeake–Leopard'' affair; demand for war; Jefferson responds with economic warfare using embargoes

* 1807–09 –

* 1807 – US Navy humiliated by Royal Navy in ''Chesapeake–Leopard'' affair; demand for war; Jefferson responds with economic warfare using embargoes

* 1807–09 – Embargo Act

The Embargo Act of 1807 was a general trade embargo on all foreign nations that was enacted by the United States Congress. As a successor or replacement law for the 1806 Non-importation Act and passed as the Napoleonic Wars continued, it repr ...

, against Great Britain and France during their wars

* 1807–12 – Impressment of 6,000 sailors from American ships with US citizenship into the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

; Great Britain ignores vehement American protests

* 1812 – America declares war on Great Britain, beginning the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

.

* 1812 – US forces invade Canada to gain a bargaining chip; they are repeatedly repulsed; The US Army at Detroit surrenders without a fight.

* 1813 – US wins control of Lake Erie and what is now Western Ontario; British and Indians defeated and Tecumseh killed; end of Indian threats to American settlement

* 1814 – Treaty of Fort Jackson

The Treaty of Fort Jackson (also known as the Treaty with the Creeks, 1814) was signed on August 9, 1814 at Fort Jackson near Wetumpka, Alabama following the defeat of the Red Stick (Upper Creek) resistance by United States allied forces at ...

* 1814 – British raid and Burn Washington; are repulsed at Baltimore

* 1814 – British invasion of northern New York defeated

* 1814 – December 24: Treaty of Ghent signed; providing status ''quo ante bellum'' (no change in boundaries); Great Britain no longer needs impressment and stops.

* 1815 – British invasion army decisively defeated at the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

:— Treaty of Ghent goes in effect in February; opens long era of friendly trade and peaceful settlement of boundary issues.

:— March 2 The US declares war on Algiers. The beginning of the Second Barbary War

The Second Barbary War (1815) or the U.S.–Algerian War was fought between the United States and the North African Barbary Coast states of Tripoli, Tunis, and Algiers. The war ended when the United States Senate ratified Commodore Stephen ...

.

:— June 28 Commodore Stephen Decatur

Stephen Decatur Jr. (; January 5, 1779 – March 22, 1820) was an American naval officer and commodore. He was born on the eastern shore of Maryland in Worcester County. His father, Stephen Decatur Sr., was a commodore in the Unit ...

arrives off Algiers, after threatening bombardment, the ''dey'' agrees to a peace treaty two days later in which he releases the American slaves and agrees to the end of the United States's tributary status.

* 1815 – Treaties of Portage des Sioux

The Treaties of Portage des Sioux were a series of treaties at Portage des Sioux, Missouri in 1815 that officially were supposed to mark the end of conflicts between the United States and Native Americans at the conclusion of the War of 1812.

...

* 1818 – London Convention of 1818, between the US and Great Britain

* 1819 – Adams-Onís Treaty: Spain cedes Florida to America for $5,000,000; America agrees to assume claims against Spain, America gives up claims to Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

.

* 1823 – Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

. British propose America join in stating that European powers will not be permitted further American colonization. President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

states it on December 2 as independent American policy.

* 1826 – Treaty of Mississinewas

The Treaty of Mississinewas or the Treaty of Mississinewa also called Treaty of the Wabash is an 1826 treaty between the United States and the Miami and Potawatomi Tribes regarding purchase of Indian lands in Indiana and Michigan. The signing was ...

* 1831 – Treaty of Wapakoneta {{Short description, 1831 land cession by the Shawnee tribe to the US in present-day Wapakoneta, Ohio

The Treaty of Wapakoneta was signed on August 8, 1831. Remnants of the Shawnee Native American tribe in Wapakoneta were forced to relinquish clai ...

* 1832 – First Sumatran expedition

The First Sumatran expedition, which featured the Battle of Quallah Battoo (Aceh: Kuala Batèë, Indonesian: Kuala Batu) in 1832, was a punitive expedition by the United States Navy against the village of Kuala Batee, presently a subdistrict i ...

, in retaliation for the seizing of American ship ''Friendship

Friendship is a relationship of mutual affection between people. It is a stronger form of interpersonal bond than an "acquaintance" or an "association", such as a classmate, neighbor, coworker, or colleague.

In some cultures, the concept of ...

'' of Salem while engaged in the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

pepper trade.

* 1832 – Treaty of Cusseta

The Treaty of Cusseta was a treaty between the government of the United States and the Creek Nation signed March 24, 1832 (). The treaty ceded all Creek claims east of the Mississippi River to the United States.

Origins

The Treaty of Cusseta ...

* 1832 – Treaty of Tippecanoe

The Treaty of Tippecanoe was an agreement between the United States government and Native American Potawatomi tribes in Indiana on October 26, 1832.

Treaty

On October 26, 1832, the United States government entered negotiations with the Native ...

* 1833 – Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

. US Navy shells the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

, at the time under Argentine control, in retaliation for the seizing of American ships fishing in Argentine waters.

:— Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

. Roberts Treaty of 1833; stipulates free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

with few limitations, most favored nation status, and relief for US citizens in cases of shipwreck, piracy, or bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debto ...

.

* 1837 – Caroline affair; Canadian military enters US territory to burn a ship used by Canadian rebels.

* 1838 – Aroostook War

The Aroostook War (sometimes called the Pork and Beans WarLe Duc, Thomas (1947). The Maine Frontier and the Northeastern Boundary Controversy. ''The American Historical Review'' Vol. 53, No. 1 (Oct., 1947), pp. 30–41), or the Madawaska War, wa ...

re: Maine-New Brunswick; no combat

:— Second Sumatran expedition

The Second Sumatran expedition was a punitive expedition by the United States Navy against inhabitants of the island of Sumatra. After Malay warriors or pirates had massacred the crew of the American merchant ship ''Eclipse'', an expedition of ...

, in retaliation for the massacre of the crew of an American merchant ship.

* 1842 – Webster–Ashburton Treaty

The Webster–Ashburton Treaty, signed August 9, 1842, was a treaty that resolved several border issues between the United States and the British North American colonies (the region that became Canada). Signed under John Tyler's presidency, it r ...

-settles US-Canada border, settling Aroostook War and Caroline affair.

* 1843 – Treaty of Bird's Fort

The Treaty of Bird's Fort, or Bird's Fort Treaty was a peace treaty between the Republic of Texas and some of the Indian tribes of Texas and Oklahoma, signed on September 29, 1843. The treaty was intended to end years of hostilities and warfare be ...

* 1844 – Oregon Question

The Oregon boundary dispute or the Oregon Question was a 19th-century territorial dispute over the political division of the Pacific Northwest of North America between several nations that had competing territorial and commercial aspirations in t ...

; America and Great Britain at sword's point; "54–40 or fight" is American slogan

* 1844 – Treaty of Wanghia

The Treaty of Wanghia (also known as the Treaty of Wangxia; Treaty of peace, amity, and commerce, between the United States of America and the Chinese Empire; ) was the first of the unequal treaties imposed by the United States on China. As p ...

.

* 1845 – Annexation of Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas ( es, República de Tejas) was a sovereign state in North America that existed from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846, that bordered Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande in 1840 (another breakaway republic from Me ...

; Mexico breaks relations in retaliation

* 1845 – Slidell Mission fails to avert war with Mexico

* 1846 – Oregon crisis ended by compromise that splits the region, with British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

to Great Britain, and Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Monta ...

, and Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

to America.

* 1846 – Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

begins; Oregon settlement with Britain.

* 1848 – Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

; settled Mexican–American War, Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( and ), known in Mexico as the Río Bravo del Norte or simply the Río Bravo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the southwestern United States and in northern Mexico.

The length of the Rio G ...

as US border; territory of New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

rest of west

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

ceded to America, especially California. US pays Mexico $15,000,000 and assumes $3,250,000 liability against Mexico.

* 1849 – Hawaiian–American Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation signed with the Kingdom of Hawaii

The Hawaiian Kingdom, or Kingdom of Hawaiʻi ( Hawaiian: ''Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina''), was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands. The country was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the independent islan ...

* 1850 – Clayton–Bulwer Treaty

The Clayton–Bulwer Treaty was a treaty signed in 1850 between the United States and the United Kingdom. The treaty was negotiated by John M. Clayton and Sir Henry Bulwer, amidst growing tensions between the two nations over Central America, a ...

. America and Great Britain agreed that both nations were not to colonize

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

or control any Central American republic, neither nation would seek exclusive control of Isthmian canal, if canal built protected by both nations for neutrality and security. Any canal built open to all nations on equal terms.

* 1851 – Treaty of Mendota

The Treaty of Mendota was signed in Mendota, Minnesota on August 5, 1851 between the United States federal government and the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute Dakota people of Minnesota.

The agreement was signed near Pilot Knob on the south bank of the M ...

* 1853 – Gadsden Purchase

The Gadsden Purchase ( es, region=MX, la Venta de La Mesilla "The Sale of La Mesilla") is a region of present-day southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico that the United States acquired from Mexico by the Treaty of Mesilla, which took effe ...

: purchase of 30,000 square miles (78,700 km2) in southern Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

for $10,000,000 for purpose of railroad connections

* 1854 – Kanagawa Treaty; Matthew Perry

Matthew Langford Perry (born August 19, 1969) is an American-Canadian actor. He is best known for his role as Chandler Bing on the NBC television sitcom ''Friends'' (1994–2004).

As well as starring in the short-lived television series '' St ...

to Tokyo in 1853; returning 1854 with seven warships; treaty opened two Japanese ports and guaranteeing the safety of shipwrecked American seamen.

* 1855 – Quinault Treaty

The Quinault Treaty (also known as the Quinault River Treaty and the Treaty of Olympia) was a treaty agreement between the United States and the Native American Quinault and Quileute tribes located in the western Olympic Peninsula north of Gra ...

* 1856 – Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

. Harris Treaty of 1856; adds extraterritoriality

In international law, extraterritoriality is the state of being exempted from the jurisdiction of local law, usually as the result of diplomatic negotiations.

Historically, this primarily applied to individuals, as jurisdiction was usually cl ...

status for US citizens to provisions of Roberts Treaty of 1833, and appointment of a US consul (representative)

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

.

* 1857 – Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the coun ...

; US Navy forces the surrender of filibusterer William Walker, who had tried to seize control of the country.

* 1858 – Modern–era Japan. Harris Treaty of 1858.

* 1858 – Yankton Treaty

The Yankton Treaty was a treaty signed in 1858 between the United States government and the Yankton Sioux (Nakota) Native American tribe, ceding most of eastern South Dakota (11 million acres) to the United States government. The treaty was signe ...

* 1858 – Outrages at Jaffa

On January 11, 1858, the Jaffa Colonists – part of the American Agricultural Mission to assist local residents in agricultural endeavors in Ottoman Palestine – were brutally attacked, creating an international incident at the beginnings of U. ...

resulted in significant US efforts to coordinate with and pressure Ottoman officials, growing US influence and strength in the region.

* 1859 – Pig War: tense confrontation over the boundary between the US and British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

, settled by arbitration, the pig the only casualty

* 1861 – President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

proclaims blockade of Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

, giving it some legitimacy

* 1861–65 – Lincoln threatens war against any country that recognizes the Confederacy; no country does so

* 1864–65 – Maximilian Affair: In defiance of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

, French Emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A neph ...

placed Archduke Maximilian on Mexican throne, America warns France against intervention, with 50,000 combat troops being sent to the Mexican border by President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

; Maximilian overthrown

* 1867 – Alaska Purchase

The Alaska Purchase (russian: Продажа Аляски, Prodazha Alyaski, Sale of Alaska) was the United States' acquisition of Alaska from the Russian Empire. Alaska was formally transferred to the United States on October 18, 1867, through a ...

: America purchases Alaska from Russia for $7,200,000.

* 1864 – Treaty on Naturalization with North German Confederation

The North German Confederation (german: Norddeutscher Bund) was initially a German military alliance established in August 1866 under the leadership of the Kingdom of Prussia, which was transformed in the subsequent year into a confederated st ...

marked first recognition by a European power of the right of its subjects to become naturalized US citizens.

* 1868 – Burlingame Treaty

The Burlingame Treaty (), also known as the Burlingame–Seward Treaty of 1868, was a landmark treaty between the United States and Qing China, amending the Treaty of Tientsin, to establish formal friendly relations between the two nations, with ...

established formal friendly relations with China and placed them on most favored nation status, Chinese immigration encouraged; reversed in 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplo ...

.

* 1871 – Alabama Claims

The ''Alabama'' Claims were a series of demands for damages sought by the government of the United States from the United Kingdom in 1869, for the attacks upon Union merchant ships by Confederate Navy commerce raiders built in British shipyard ...

. During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

raider built in Great Rice, America claimed direct and collateral damage against Great Britain, awarded $15,500,000 by international tribunal.

* 1875 – Reciprocity Treaty of 1875

The Treaty of reciprocity between the United States of America and the Hawaiian Kingdom ( Hawaiian: ''Kuʻikahi Pānaʻi Like'') was a free trade agreement signed and ratified in 1875 that is generally known as the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875.

T ...

with the Kingdom of Hawaii

The Hawaiian Kingdom, or Kingdom of Hawaiʻi ( Hawaiian: ''Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina''), was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands. The country was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the independent islan ...

established free access to American markets for Hawaiian sugar and other products, and also ceded Puʻu Loa, which became Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

* 1891 – ''Baltimore'' crisis, minor scuffle with Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

over treatment of soldiers.

* 1893 – Hawaii; January 16 to April 1. American businessmen unhappy with Queen Liliuokalani attempt to set up absolute monarchy; overthrows their dog with no violence and proclaims provisional government; US Marines

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through comb ...

landed to protect American lives; Hawaii and President Harrison agree to annexation but treaty withdrawn (1893) by President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

who rejects annexation

* 1895 – Venezuela Crisis of 1895

The Venezuelan crisis of 1895 occurred over Venezuela's longstanding dispute with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland about the territory of Essequibo and Guayana Esequiba, which Britain claimed as part of British Guiana and Venezue ...

is a dispute with Britain over the boundary of Venezuela and a British colony; it is finally settled by arbitration.

* 1897 – The Olney-Pauncefote Treaty of 1897 is a proposed treaty with Britain in 1897 that required arbitration of major disputes. Despite wide public and elite support, the treaty was rejected by the US Senate, which was jealous of its prerogatives, and never went into effect.

* 1897–98 – American public opinion is outraged by news of Spanish atrocities in Cuba. President McKinley demands reforms.

* 1898 – De Lôme Letter: Spanish minister to Washington writes disparagingly of President McKinley, casting doubt on Spain's promises to reform its role in Cuba

:— Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

; "splendid little war" with American quick victory

:— Treaty of Paris; US gains Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico; pays Spain for claims; Cuba comes under temporary US control

:— Hawaii seeks to join US; with votes lacking for 2/3 approval of a treaty on July 7. The Newlands Resolution

The Newlands Resolution was a joint resolution passed on July 7, 1898, by the United States Congress to annex the independent Republic of Hawaii. In 1900, Congress created the Territory of Hawaii.

The resolution was drafted by Representative Fr ...

in Congress annexes the Republic of Hawaii

The Republic of Hawaii ( Hawaiian: ''Lepupalika o Hawaii'') was a short-lived one-party state in Hawaii between July 4, 1894, when the Provisional Government of Hawaii had ended, and August 12, 1898, when it became annexed by the United State ...

, with full US citizenship for Hawaiian citizens regardless of race

* 1899–1901 – Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War or Filipino–American War ( es, Guerra filipina-estadounidense, tl, Digmaang Pilipino–Amerikano), previously referred to as the Philippine Insurrection or the Tagalog Insurgency by the United States, was an arm ...

, commonly known as the "Philippine Insurrection".

* 1899 – Open Door Policy

The Open Door Policy () is the United States diplomatic policy established in the late 19th and early 20th century that called for a system of equal trade and investment and to guarantee the territorial integrity of Qing China. The policy wa ...

for equal trading rights inside China; accepted by Great Britain, Germany, France, Italy, Russia and Japan

* 1900 – US forces participate in international rescue in Peking

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

, in Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an Xenophobia, anti-foreign, anti-colonialism, anti-colonial, and Persecution of Christians#China, anti-Christian uprising in China ...

1900–1939

* 1901 – Hay–Pauncefote Treaty. American agreement with Great Britain nullifyingClayton–Bulwer Treaty

The Clayton–Bulwer Treaty was a treaty signed in 1850 between the United States and the United Kingdom. The treaty was negotiated by John M. Clayton and Sir Henry Bulwer, amidst growing tensions between the two nations over Central America, a ...

of 1850; guarantee of open passage for any nation through proposed Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

.

* 1901 – Platt Amendment

On March 2, 1901, the Platt Amendment was passed as part of the 1901 Army Appropriations Bill.Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

's independence from foreign intervention. The amendment effectively makes Cuba a US protectorate and allowed for American intervention in Cuban affairs in 1906, 1912, 1917, and 1920. It also permitted America to lease Guantanamo Bay Naval Base

Guantanamo Bay Naval Base ( es, Base Naval de la Bahía de Guantánamo), officially known as Naval Station Guantanamo Bay or NSGB, (also called GTMO, pronounced Gitmo as jargon by members of the U.S. military) is a United States military bas ...

. Rising Cuban nationalism and widespread criticism led to its abrogation in 1934 by the Ramón Grau

Ramón Grau San Martín (13 September 1881 in La Palma, Pinar del Río Province, Spanish Cuba – 28 July 1969 in Havana, Cuba) was a Cuban physician who served as President of Cuba from 1933 to 1934 and from 1944 to 1948. He was the last pre ...

administration.

* 1902 – Drago Doctrine

The Drago Doctrine was announced in 1902 by Argentine Minister of Foreign Affairs Luis María Drago in a diplomatic note to the United States.

Perceiving a conflict between the Monroe Doctrine and the influence of European imperial powers, and ra ...

. Foreign Minister Luis María Drago

Luis María Drago ( - ) was an Argentine politician.

Born into a distinguished Argentine family in Buenos Aires, Drago began his career as a newspaper editor. Later, he served as a minister of foreign affairs (1902). At that time, when the UK, ...

of Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

announced policy that no European power could use force against any American nation to collect debt, supplanted in 1904 by Roosevelt Corollary

In the history of United States foreign policy, the Roosevelt Corollary was an addition to the Monroe Doctrine articulated by President Theodore Roosevelt in his State of the Union address in 1904 after the Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903. ...

to Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

.

* 1903 – Big Stick diplomacy: Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

refers to US policy as "speaking softly and carrying a big stick", applied the same year by assisting Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

's independence movement from Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the ...

. US forces sought to protect American interests and lives during and following the Panamanian revolution over construction of the Isthmian Canal. US Marines were stationed on the isthmus (1903–1914)

* 1903 – Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty

The Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty ( es, Tratado Hay-Bunau Varilla) was a treaty signed on November 18, 1903, by the United States and Panama, which established the Panama Canal Zone and the subsequent construction of the Panama Canal. It was named ...

with Panama; leased strip of land increased to 10 miles (16 km) wide.

* 1903 – Alaska boundary treaty resolved the Alaska boundary dispute

The Alaska boundary dispute was a territorial dispute between the United States and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, which then controlled Canada's foreign relations. It was resolved by arbitration in 1903. The dispute had existed ...

between the United States and Canada in favor of US; Canada angry at Britain.

* 1906 – Algeciras Conference

The Algeciras Conference of 1906 took place in Algeciras, Spain, and lasted from 16 January to 7 April. The purpose of the conference was to find a solution to the First Moroccan Crisis of 1905 between France and Germany, which arose as German ...

. Roosevelt mediated the First Moroccan Crisis between France and Germany, essentially in French favor.

* 1908–09 – America negotiates arbitration treaties with 25 countries (not Germany)

* 1911 – Reciprocity treaty with Canada fails on surge of Canadian nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

led by Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

.

* 1911–20 – Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution ( es, Revolución Mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from approximately 1910 to 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction ...

; hundreds of thousands of refugees flee to America; President William Howard Taft