Prime Ministers of Australia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The prime minister of Australia is the

The prime minister of Australia is appointed by the governor-general of Australia under Section 64 of the

The prime minister of Australia is appointed by the governor-general of Australia under Section 64 of the  According to convention, the prime minister is the leader of the majority party or largest party in a coalition of parties in the

According to convention, the prime minister is the leader of the majority party or largest party in a coalition of parties in the

File:The Lodge Canberra renovated.jpg, The Lodge

File:(1)Kirribilli House Kirribilli.jpg,

Official website of the prime minister of Australia

Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet

Australia's Prime Ministers

– National Archives of Australia reference site and research portal

Biographies of Australia's Prime Ministers

/ National Museum of Australia

Classroom resources on Australian Prime Ministers

Museum of Australian Democracy website about Australian prime ministers

{{DEFAULTSORT:Prime Minister of Australia Lists of government ministers of Australia 1901 establishments in Australia

head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

of the Commonwealth of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

. The prime minister heads the executive branch of the federal government

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governin ...

of Australia and is also accountable to federal parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the governor-gen ...

under the principles of responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive bran ...

. The current prime minister is Anthony Albanese

Anthony Norman Albanese ( or ; born 2 March 1963) is an Australian politician serving as the 31st and current prime minister of Australia since 2022. He has been leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) since 2019 and the member of parlia ...

of the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms the f ...

, who became prime minister on 23 May 2022.

Formally appointed by the governor-general

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

, the role and duties of the prime minister are not described by the Australian constitution

The Constitution of Australia (or Australian Constitution) is a constitutional document that is supreme law in Australia. It establishes Australia as a federation under a constitutional monarchy and outlines the structure and powers of the ...

but rather defined by constitutional convention deriving from the Westminster system. To become prime minister, a politician should be able to command the confidence of the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

. As such, the prime minister is typically the leader of the majority party

A party is a gathering of people who have been invited by a host for the purposes of socializing, conversation, recreation, or as part of a festival or other commemoration or celebration of a special occasion. A party will often feature f ...

or coalition

A coalition is a group formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political or economical spaces.

Formation

According to ''A Gui ...

. Prime ministers do not have a set duration or number of terms, but an individual's term generally ends when their political party loses a federal election, or they lose or relinquish the leadership of their party.

Executive power

The Executive, also referred as the Executive branch or Executive power, is the term commonly used to describe that part of government which enforces the law, and has overall responsibility for the governance of a state.

In political systems ba ...

is formally vested in the monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority ...

and exercised by the governor-general on advice from government ministers, who are nominated by the prime minister and form the Federal Executive Council. The most senior ministers form the federal cabinet, which the prime minister chairs. The prime minister also heads the National Cabinet

National Cabinet is the Australian intergovernmental decision-making forum composed of the Prime Minister of Australia, prime minister and Premiers and Chief Ministers of the Australian states and territories, state and territory premiers an ...

and the National Security Committee. Administrative support is provided by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The prime minister has two official residences: The Lodge in Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

and Kirribilli House

Kirribilli House is the secondary official residence of the Prime Minister of Australia. Located in the Sydney harbourside suburb of , New South Wales, the house is at the far eastern end of Kirribilli Avenue. It is one of two official Prime Min ...

in Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

, as well as an office at Parliament House.

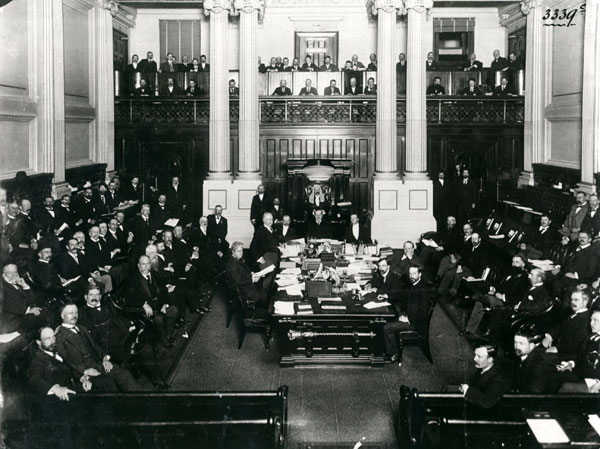

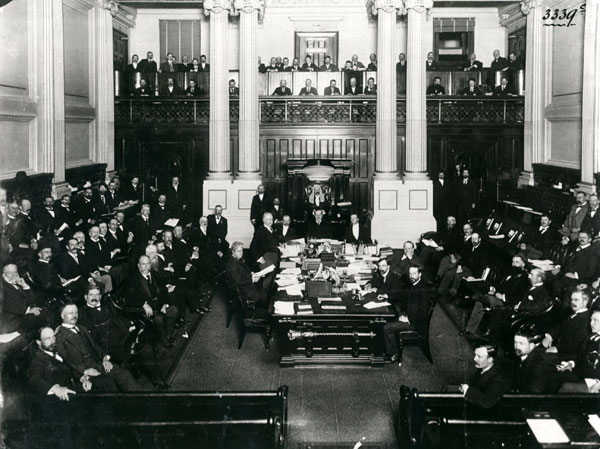

Thirty-one people have served as prime minister, the first of whom was Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund "Toby" Barton, (18 January 18497 January 1920) was an Australian politician and judge who served as the first prime minister of Australia from 1901 to 1903, holding office as the leader of the Protectionist Party. He resigned to ...

taking office on 1 January 1901 following federation of the British colonies in Australia. The longest-serving prime minister was Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

, who served over 18 years, and the shortest-serving was Frank Forde

Francis Michael Forde (18 July 189028 January 1983) was an Australian politician who served as prime minister of Australia from 6 to 13 July 1945. He was the deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1932 to 1946. He served as pri ...

, who served one week. There is no legislated line of succession

An order of succession or right of succession is the line of individuals necessitated to hold a high office when it becomes vacated such as head of state or an honour such as a title of nobility.deputy prime minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

on a caretaker

Caretaker may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''The Caretaker'' (film), a 1963 adaptation of the play ''The Caretaker''

* '' The Caretakers'', a 1963 American film set in a mental hospital

* Caretaker, a character in the 1974 film '' ...

basis in the event of a vacancy.

Constitutional basis and appointment

The prime minister of Australia is appointed by the governor-general of Australia under Section 64 of the

The prime minister of Australia is appointed by the governor-general of Australia under Section 64 of the Australian Constitution

The Constitution of Australia (or Australian Constitution) is a constitutional document that is supreme law in Australia. It establishes Australia as a federation under a constitutional monarchy and outlines the structure and powers of the ...

, which empowers the governor-general to appoint ministers of state (the office of prime minister is not mentioned) on the advice of the Federal Executive Council, and requires them to be members of the House of Representatives or the Senate, or become members within three months of the appointment. The prime minister and treasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury o ...

are traditionally members of the House, but the Constitution does not have such a requirement. Before being sworn in as a minister of state

Minister of State is a title borne by politicians in certain countries governed under a parliamentary system. In some countries a Minister of State is a Junior Minister of government, who is assigned to assist a specific Cabinet Minister. In o ...

, a person must first be sworn in as a member of the Federal Executive Council if they are not already a member. Membership of the Federal Executive Council entitles the member to the style of ''The Honourable'' (usually abbreviated to ''The Hon'') for life, barring exceptional circumstances. The senior members of the Executive Council constitute the Cabinet of Australia

The Cabinet of Australia (or Federal Cabinet) is the chief decision-making organ of the executive branch of the government of Australia. It is a council of senior government ministers, ultimately responsible to the Federal Parliament.

Minister ...

.

The prime minister is, like other ministers, normally sworn in by the governor-general and then presented with the commission (letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, titl ...

) of office. When defeated in an election, or on resigning, the prime minister is said to "hand in the commission" and actually does so by returning it to the governor-general. In the event of a prime minister dying in office, or becoming incapacitated, or for other reasons, the governor-general can terminate the commission. Ministers hold office "during the pleasure of the governor-general" (s. 64 of the Constitution of Australia), so in practice, the governor-general can dismiss a minister at any time, by notifying them in writing of the termination of their commission; however, their power to do so except on the advice of the prime minister is heavily circumscribed by convention.

According to convention, the prime minister is the leader of the majority party or largest party in a coalition of parties in the

According to convention, the prime minister is the leader of the majority party or largest party in a coalition of parties in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

which holds the confidence of the House. The governor-general may also dismiss a prime minister who is unable to pass the government's supply bill through both houses of parliament, including the Australian Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the Bicameralism, bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the House of Representatives (Australia), House of Representatives. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Chapter ...

, where the government doesn't normally command the majority, as happened in the 1975 constitutional crisis. Other commentators argue that the governor-general acted improperly in 1975 as Whitlam still retained the confidence of the House of Representatives, and there are no generally accepted conventions to guide the use of the governor-general's reserve powers in this circumstance. However, there is no constitutional requirement that the prime minister sit in the House of Representatives, or even be a member of the federal parliament (subject to a constitutionally prescribed limit of three months), though by convention this is always the case. The only case where a member of the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

was appointed prime minister was John Gorton

Sir John Grey Gorton (9 September 1911 – 19 May 2002) was an Australian politician who served as the nineteenth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1968 to 1971. He led the Liberal Party during that time, having previously been a l ...

, who subsequently resigned his Senate position and was elected Elected may refer to:

* "Elected" (song), by Alice Cooper, 1973

* ''Elected'' (EP), by Ayreon, 2008

*The Elected, an American indie rock band

See also

*Election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population ...

as the member for Higgins in the House of Representatives.

Despite the importance of the office of prime minister, the Constitution does not mention the office by name. The conventions of the Westminster system were thought to be sufficiently entrenched in Australia by the authors of the Constitution that it was deemed unnecessary to detail these. Indeed, prior to Federation in 1901 the terms "premier" and "prime minister" were used interchangeably for the head of government in a colony.

If a government cannot get its appropriation (budget) legislation passed by the House of Representatives, or the House passes a vote of "no confidence" in the government, the prime minister is bound by convention to either resign or immediately advise the governor-general to dissolve the House of Representatives and hold a fresh election.

Following a resignation in other circumstances or the death of a prime minister, the governor-general generally appoints the deputy prime minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

as the new prime minister, until or if such time as the governing party or senior coalition party elects an alternative party leader. This has resulted in the party leaders from the Country Party (now named National Party) being appointed as prime minister, despite being the smaller party of their coalition. This occurred when Earle Page

Sir Earle Christmas Grafton Page (8 August 188020 December 1961) was an Australian surgeon and politician who served as the 11th Prime Minister of Australia, holding office for 19 days after the death of Joseph Lyons in 1939. He was the leade ...

became caretaker prime minister following the death of Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the List of prime ministers of Australia by time in office, 10th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1932 until his death in 1939. He ...

in 1939, and when John McEwen

Sir John McEwen, (29 March 1900 – 20 November 1980) was an Australian politician who served as the 18th prime minister of Australia, holding office from 1967 to 1968 in a caretaker capacity after the disappearance of Harold Holt. He was the ...

became caretaker prime minister following the disappearance of Harold Holt

On 17 December 1967, Harold Holt, the Prime Minister of Australia, disappeared while swimming in the sea near Portsea, Victoria. An enormous search operation was mounted in and around Cheviot Beach, but his body was never recovered. Holt was pr ...

in 1967. However, in 1941, Arthur Fadden

Sir Arthur William Fadden, (13 April 189421 April 1973) was an Australian politician who served as the 13th prime minister of Australia from 29 August to 7 October 1941. He was the leader of the Country Party from 1940 to 1958 and also served ...

became the leader of the Coalition and subsequently prime minister by the agreement of both coalition parties, despite being the leader of the smaller party in coalition, following the resignation of UAP leader Robert Menzies.

Excluding the brief transition periods during changes of government or leadership elections, there have only been a handful of cases where someone other than the leader of the majority party in the House of Representatives was prime minister:

* Federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governin ...

occurred on 1 January 1901, but elections for the first parliament were not scheduled until late March. In the interim, an unelected caretaker government

A caretaker government is a temporary ''ad hoc'' government that performs some governmental duties and functions in a country until a regular government is elected or formed. Depending on specific practice, it usually consists of either randomly se ...

was necessary. In what is now known as the Hopetoun Blunder

The Hopetoun Blunder was a political event immediately prior to the Federation of the British colonies in Australia.

Federation was scheduled to occur on 1 January 1901, but since the general election for the first Parliament of Australia was ...

, the governor-general, Lord Hopetoun

John Adrian Louis Hope, 1st Marquess of Linlithgow, 7th Earl of Hopetoun, (25 September 1860 – 29 February 1908) was a British aristocrat and statesman who served as the first governor-general of Australia, in office from 1901 to 1902. He wa ...

, invited Sir William Lyne

Sir William John Lyne KCMG (6 April 1844 – 3 August 1913) was an Australian politician who served as Premier of New South Wales from 1899 to 1901, and later as a federal cabinet minister under Edmund Barton and Alfred Deakin. He is best known ...

, the premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of governm ...

of the most populous state, New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, to form a government. Lyne was unable to do so and returned his commission in favour of Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund "Toby" Barton, (18 January 18497 January 1920) was an Australian politician and judge who served as the first prime minister of Australia from 1901 to 1903, holding office as the leader of the Protectionist Party. He resigned to ...

, who became the first prime minister and led the inaugural government into and beyond the election.

* During the second parliament, three parties (Free Trade, Protectionist and Labor) had roughly equal representation in the House of Representatives. The leaders of the three parties, Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

, George Reid

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth Prime Minister of Australia from 1904 to 1905, having previously been Premier of New South Wales f ...

and Chris Watson each served as prime minister before losing a vote of confidence.

* As a result of the Labor Party's split over conscription, Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

and his supporters were expelled from the Labor Party in November 1916. He subsequently continued on as prime minister at the head of the new National Labor Party

The National Labor Party was formed by Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes in 1916, following the 1916 Labor split on the issue of World War I conscription in Australia. Hughes had taken over as leader of the Australian Labor Party and Pr ...

, which had only 14 members out of a total of 75 in the House of Representatives. The Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Liberal Party was a parliamentary party in Australian federal politics between 1909 and 1917. The party was founded under Alfred Deakin's leadership as a merger of the Protectionist Party and Anti-Socialist Party, an event known as the Fu ...

– despite still forming the official Opposition – provided confidence and supply until February 1917, when the two parties agreed to merge and formed the Nationalist Party.

* During the 1975 constitutional crisis, on 11 November 1975, the governor-general, Sir John Kerr, dismissed the Labor Party's Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from 1972 to 1975. The longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1967 to 1977, he was notable for being the he ...

as prime minister. Despite Labor holding a majority in the House of Representatives, Kerr appointed the Leader of the Opposition, Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

leader Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983, holding office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Fraser was raised on hi ...

as caretaker prime minister, conditional on the passage of the Whitlam government's Supply

Supply may refer to:

*The amount of a resource that is available

**Supply (economics), the amount of a product which is available to customers

**Materiel, the goods and equipment for a military unit to fulfill its mission

*Supply, as in confidenc ...

bills through the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

and the calling of an election for both houses of parliament. Fraser accepted these terms and immediately advised a double dissolution

A double dissolution is a procedure permitted under the Australian Constitution to resolve deadlocks in the bicameral Parliament of Australia between the House of Representatives (lower house) and the Senate (upper house). A double dissolution ...

. An election was called for 13 December, which the Liberal Party won in its own right (although the Liberals governed in a coalition with the Country Party).

Compared to other Westminster systems such as those of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

's federal and provincial governments, the transition from an outgoing prime minister to an incoming prime minister has been brief in Australia since the 1970s. Prior to that, in accordance with longstanding Australian constitutional practice, convention held that an outgoing prime minister would stay on as a caretaker until the full election results were tallied. Starting with the 1972 Australian federal election

The 1972 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 2 December 1972. All 125 seats in the House of Representatives were up for election, as well as a single Senate seat in Queensland. The incumbent Liberal–Country coalition governme ...

on 2 December 1972, Gough Whitlam and his deputy were sworn in on 5 December 1972 to form an interim government for two weeks, as the vote was being finalized and the full ministry makeup was being determined. Recently Anthony Albanese

Anthony Norman Albanese ( or ; born 2 March 1963) is an Australian politician serving as the 31st and current prime minister of Australia since 2022. He has been leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) since 2019 and the member of parlia ...

became prime minister on 23 May 2022 which was two days after the 2022 Australian federal election

The 2022 Australian federal election was held on Saturday 21 May 2022 to elect members of the 47th Parliament of Australia. The incumbent Liberal/National Coalition government, led by Prime Minister Scott Morrison, sought to win a fourth conse ...

where his party won a decisive victory, with Albanese and four senior cabinet ministers received an interim swearing-in, while the entire ministry is to be set by 30 May 2022.

Powers and role

Most of the prime minister's power derives from being thehead of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

. In practice, the Federal Executive Council acts to ratify all executive decisions made by the government and requires the support of the prime minister. The powers of the prime minister are to direct the governor-general through advice to grant royal assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in other ...

to legislation, to dissolve and prorogue parliament, to call elections and to make government appointments, which the governor-general follows according to convention.

The Constitution divides power between the federal government and the states, and the prime minister is constrained by this.

The formal power to appoint the governor-general

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

lies with the king of Australia

The monarchy of Australia is Australia's form of government embodied by the Australian sovereign and head of state. The Australian monarchy is a constitutional monarchy, modelled on the Westminster system of parliamentary government, while i ...

, on the advice of the prime minister, whereby convention holds that the king is bound to follow the advice. The prime minister can also advise the monarch to dismiss the governor-general, though it remains unclear how quickly the monarch would act on such advice in a constitutional crisis. This uncertainty, and the possibility of a "race" between the governor-general and prime minister to dismiss the other, was a key question in the 1975 constitutional crisis. Prime ministers whose government loses a vote of no-confidence

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or mana ...

in the House of Representatives, are expected to advise the governor-general to dissolve parliament and hold an election, if an alternative government cannot be formed. If they fail to do this, the governor-general may by convention dissolve parliament or appoint an alternative government.

The prime minister is also the responsible minister for the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, which is tasked with supporting the policy agendas of the prime minister and Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

through policy advice and the coordination of the implementation of key government programs, to manage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

policy and programs and to promote reconciliation

Reconciliation or reconcile may refer to:

Accounting

* Reconciliation (accounting)

Arts, entertainment, and media Sculpture

* ''Reconciliation'' (Josefina de Vasconcellos sculpture), a sculpture by Josefina de Vasconcellos in Coventry Cathedra ...

, to provide leadership for the Australian Public Service

The Australian Public Service (APS) is the federal civil service of the Commonwealth of Australia responsible for the public administration, public policy, and public services of the departments and executive and statutory agencies of the G ...

alongside the Australian Public Service Commission

The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) is a statutory agency of the Australian Government, within the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, that acts to ensure the organisational and workforce capability to meet future needs a ...

, to oversee the honours

Honour (British English) or honor (American English; see spelling differences) is the idea of a bond between an individual and a society as a quality of a person that is both of social teaching and of personal ethos, that manifests itself as a ...

and symbols

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

of the Commonwealth, to provide support to ceremonies and official visits, to set whole of government service delivery policy, and to coordinate national security, cyber, counter-terrorism

Counterterrorism (also spelled counter-terrorism), also known as anti-terrorism, incorporates the practices, military tactics, techniques, and strategies that governments, law enforcement, business, and intelligence agencies use to combat or el ...

, regulatory reform, cities, population, data, and women's policy. Since 1992, the prime minister also acts as the chair of the Council of Australian Governments

The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) was the primary intergovernmental forum in Australia from 1992 to 2020. Comprising the federal government, the governments of the six states and two mainland territories and the Australian Local G ...

(COAG), an intergovernmental forum between the federal government and the state governments in which the prime minister, the state premiers and chief ministers, and a representative of local governments meet annually.

Amenities of office

Salary

Australia's prime minister is paid a total salary of . This is made up of the 'base salary' received by all Members of Parliament () plus a 160 percent 'additional salary' for the role of prime minister. Increases in the base salary of MPs and senators are determined annually by the independent Remuneration Tribunal.Residences and transport

While in office, the prime minister has two official residences. The primary official residence is The Lodge inCanberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

. Most prime ministers have chosen The Lodge as their primary residence because of its security facilities and close proximity to Parliament House. There have been some exceptions, however. James Scullin

James Henry Scullin (18 September 1876 – 28 January 1953) was an Australian Labor Party politician and the ninth Prime Minister of Australia. Scullin led Labor to government at the 1929 Australian federal election. He was the first Catho ...

preferred to live at the Hotel Canberra

The Hotel Canberra, also known as Hyatt Hotel Canberra, is a major hotel in the Australian national capital, Canberra. It is located in the suburb of Yarralumla, near Lake Burley Griffin and Parliament House. It was built to house politici ...

(now the Hyatt Hotel) and Ben Chifley

Joseph Benedict Chifley (; 22 September 1885 – 13 June 1951) was an Australian politician who served as the 16th prime minister of Australia from 1945 to 1949. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1945, follow ...

lived in the Hotel Kurrajong

Hotel Kurrajong Canberra is a heritage-listed hotel located in the Canberra suburb of Barton, Australian Capital Territory, close to Parliament House and national institutions within the Parliamentary Triangle precinct. The Hotel has a strong ...

. More recently, John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007, holding office as leader of the Liberal Party. His eleven-year tenure as prime minister is the s ...

used the Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

prime ministerial residence, Kirribilli House

Kirribilli House is the secondary official residence of the Prime Minister of Australia. Located in the Sydney harbourside suburb of , New South Wales, the house is at the far eastern end of Kirribilli Avenue. It is one of two official Prime Min ...

, as his primary accommodation. On her appointment on 24 June 2010, Julia Gillard

Julia Eileen Gillard (born 29 September 1961) is an Australian former politician who served as the 27th prime minister of Australia from 2010 to 2013, holding office as leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP). She is the first and only ...

said she would not be living in The Lodge until such time as she was returned to office by popular vote at the next general election, as she became prime minister by replacing an incumbent during a parliamentary term. Tony Abbott

Anthony John Abbott (; born 4 November 1957) is a former Australian politician who served as the 28th prime minister of Australia from 2013 to 2015. He held office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Abbott was born in Londo ...

was never able to occupy The Lodge during his term (2013–15) because it was undergoing extensive renovations, which continued into the early part of his successor Malcolm Turnbull

Malcolm Bligh Turnbull (born 24 October 1954) is an Australian former politician and businessman who served as the 29th prime minister of Australia from 2015 to 2018. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Turnbull grad ...

's term. Instead, Abbott resided in dedicated rooms at the Australian Federal Police College when in Canberra.

During his first term, Rudd had a staff at The Lodge consisting of a senior chef and an assistant chef, a child carer, one senior house attendant, and two junior house attendants. At Kirribilli House

Kirribilli House is the secondary official residence of the Prime Minister of Australia. Located in the Sydney harbourside suburb of , New South Wales, the house is at the far eastern end of Kirribilli Avenue. It is one of two official Prime Min ...

in Sydney, there are a full-time chef and a full-time house attendant.

The official residences are fully staffed and catered for both the prime minister and their family. In addition, both have extensive security facilities. These residences are regularly used for official entertaining, such as receptions for Australian of the Year finalists.

The prime minister receives a number of transport amenities for official business. The Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

's Airbus A330 MRTT, or KC30-A, transports the prime minister within Australia and overseas. The call-sign for the aircraft is "Envoy". For ground travel, the prime minister is transported in an armoured BMW 7 Series model. It is referred to as "C-1", or Commonwealth One, because of its number plate. It is escorted by police vehicles from state and federal authorities.

Kirribilli House

Kirribilli House is the secondary official residence of the Prime Minister of Australia. Located in the Sydney harbourside suburb of , New South Wales, the house is at the far eastern end of Kirribilli Avenue. It is one of two official Prime Min ...

File:BMW 7er M-Sportpaket (F01) – Frontansicht, 7. Mai 2011, Düsseldorf.jpg, Prime Ministerial Limousine

File:RAAF Boeing 737-7DT(BBJ) CBR Gilbert-1.jpg, Official aircraft

After office

Politicians, including prime ministers, are usually granted certain privileges after leaving office, such as office accommodation, staff assistance, and a Life Gold Pass which entitles the holder to travel within Australia for "non-commercial" purposes at government expense. In 2017, then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull said the pass should be available only to former prime ministers, though he would not use it when he was no longer PM. Only one prime minister who had left the Federal Parliament ever returned.Stanley Bruce

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, (15 April 1883 – 25 August 1967) was an Australian politician who served as the eighth prime minister of Australia from 1923 to 1929, as leader of the Nationalist Party.

Born ...

was defeated in his own seat in 1929

This year marked the end of a period known in American history as the Roaring Twenties after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 ushered in a worldwide Great Depression. In the Americas, an agreement was brokered to end the Cristero War, a Catholic ...

while prime minister but was re-elected to parliament in 1931

Events

January

* January 2 – South Dakota native Ernest Lawrence invents the cyclotron, used to accelerate particles to study nuclear physics.

* January 4 – German pilot Elly Beinhorn begins her flight to Africa.

* January 22 – Sir I ...

. Other prime ministers were elected to parliaments other than the Australian federal parliament: Sir George Reid

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth Prime Minister of Australia from 1904 to 1905, having previously been Premier of New South Wales f ...

was elected to the UK House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 mem ...

(after his term as High Commissioner to the UK), and Frank Forde

Francis Michael Forde (18 July 189028 January 1983) was an Australian politician who served as prime minister of Australia from 6 to 13 July 1945. He was the deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1932 to 1946. He served as pri ...

was re-elected to the Queensland Parliament (after his term as High Commissioner to Canada, and a failed attempt to re-enter the Federal Parliament).

Acting prime ministers and succession

Thedeputy prime minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

becomes acting prime minister

An acting prime minister is a cabinet member (often in Westminster system countries) who is serving in the role of prime minister, whilst the individual who normally holds the position is unable to do so. The role is often performed by the deputy ...

if the prime minister is unable to undertake the role for a short time, for example if they are ill, overseas or on leave (and if both are unavailable, then another senior minister takes on this role). The ''Acts Interpretation Act 1901'' confers upon acting ministers "the same power and authority with respect to the absent Minister's statutory responsibilities".

If the prime minister were to die, then the deputy prime minister would be appointed prime minister by the governor-general until the government votes for another member to be its leader. This happened when Harold Holt disappeared in 1967, when John McEwen

Sir John McEwen, (29 March 1900 – 20 November 1980) was an Australian politician who served as the 18th prime minister of Australia, holding office from 1967 to 1968 in a caretaker capacity after the disappearance of Harold Holt. He was the ...

was appointed prime minister. On the other two occasions that the prime minister has died in office, in 1939

This year also marks the start of the Second World War, the largest and deadliest conflict in human history.

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

January

* January 1

** Third Reich

*** Jews are forbidden to ...

and 1945

1945 marked the end of World War II and the fall of Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan. It is also the only year in which nuclear weapons have been used in combat.

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

Januar ...

, Earle Page

Sir Earle Christmas Grafton Page (8 August 188020 December 1961) was an Australian surgeon and politician who served as the 11th Prime Minister of Australia, holding office for 19 days after the death of Joseph Lyons in 1939. He was the leade ...

and Frank Forde

Francis Michael Forde (18 July 189028 January 1983) was an Australian politician who served as prime minister of Australia from 6 to 13 July 1945. He was the deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1932 to 1946. He served as pri ...

, respectively, were appointed prime minister.

In the early 20th century, overseas travel generally required long journeys by ship. As a result, some held the position of acting prime minister for significant periods of time, including William Watt (16 months, 1918–1919), George Pearce

Sir George Foster Pearce KCVO (14 January 1870 – 24 June 1952) was an Australian politician who served as a Senator for Western Australia from 1901 to 1938. He began his career in the Labor Party but later joined the National Labor Party, t ...

(7 months, 1916), Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

(6 months, 1902), Joseph Cook (5 months, 1921), James Fenton

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

(19 weeks, 1930–1931), John Forrest

Sir John Forrest (22 August 1847 – 2 SeptemberSome sources give the date as 3 September 1918 1918) was an Australian explorer and politician. He was the first premier of Western Australia (1890–1901) and a long-serving cabinet minister i ...

(4 months, 1907), and Arthur Fadden

Sir Arthur William Fadden, (13 April 189421 April 1973) was an Australian politician who served as the 13th prime minister of Australia from 29 August to 7 October 1941. He was the leader of the Country Party from 1940 to 1958 and also served ...

(4 months, 1941). Fadden was acting prime minister for a cumulative total of 676 days (over 22 months) between 1941 and 1958.

Honours

Prime ministers have been granted numerous honours, typically after their period as prime minister has concluded, with a few exceptions. Nine former prime ministers were awarded knighthoods: Barton (GCMG

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

, 1902), Reid (GCMG, 1911), Cook (GCMG, 1918), Page (GCMG, 1938), Menzies ( KT, 1963), Fadden (KCMG, 1951), McEwen (GCMG, 1971), Gorton (GCMG, 1977), and McMahon (GCMG, 1977). Of those awarded, Barton and Menzies were knighted while still serving as prime minister, with Page awarded his before becoming prime minister, and the remainder awarded after leaving office. Reid ( GCB, 1916), Menzies ( AK, 1976) and Fadden (GCMG, 1958) were awarded a second knighthood after leaving office.

Non-titular honours were also bestowed on former prime ministers, usually the Order of the Companions of Honour

The Order of the Companions of Honour is an order of the Commonwealth realms. It was founded on 4 June 1917 by King George V as a reward for outstanding achievements. Founded on the same date as the Order of the British Empire, it is sometimes ...

. This honour was awarded to Bruce (1927), Lyons (1936), Hughes (1941), Page (1942), Menzies (1951), Holt (1967), McEwen (1969), Gorton (1971), McMahon (1972), and Fraser (1977), mostly during office as prime minister.

In almost all occasions these honours were only accepted by non-Labor/conservative prime ministers. However, appointment to the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises senior politicians who are current or former members of e ...

was accepted by all prime ministers until 1983 (with the exception of Alfred Deakin, Chris Watson and Gough Whitlam), with Malcolm Fraser being the last prime ministerial appointee.

Since its introduction in 1975, former prime ministers of Australia have been appointed to the Order of Australia and to its highest level – Companion: Whitlam (1978), Fraser (1988), Gorton (1988), Howard (2008), Gillard (2017), Rudd (2019), Abbott (2020), and Turnbull (2021). Keating refused appointment in the 1997 Australia Day Honours, saying that he had long believed honours should be reserved for those whose work in the community went unrecognised and that having been Prime Minister was sufficient public recognition. Bob Hawke was appointed a Companion in 1979, for service to trade unionism and industrial relations, before becoming prime minister in 1983. Menzies was appointed to the higher grade of Knight of the Order, which is no longer awarded, in 1976.

John Howard was also appointed to the Order of Merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by K ...

, whose appointments are within the personal gift of the Queen, in 2012.

In addition to these honours, all deceased former prime ministers of Australia currently have federal electorates named after them, with the exception of Joseph Cook (a Division of Cook

The Division of Cook is an Australian electoral division in the State of New South Wales.

History

Cook was created in 1969, mostly out of the Liberal-leaning areas of neighbouring Hughes. It was thus a natural choice for that seat's one-ter ...

does exist, but it is named after explorer James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

). The most recently created of these electorates is the Division of Hawke

The Division of Hawke is an Australian electoral division in the state of Victoria, which was contested for the first time at the 2022 Australian federal election. The electorate is centred on the localities of Bacchus Marsh, Ballan, Melton ...

, named in honour of the recently deceased Bob Hawke in 2021.

Lists relating to the prime ministers of Australia

The longest-serving prime minister wasRobert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

, who served in office twice: from 26 April 1939 to 28 August 1941, and again from 19 December 1949 to 26 January 1966. In total Robert Menzies spent 18 years, 5 months and 12 days in office. He served under the United Australia Party and the Liberal Party respectively.

The shortest-serving prime minister was Frank Forde

Francis Michael Forde (18 July 189028 January 1983) was an Australian politician who served as prime minister of Australia from 6 to 13 July 1945. He was the deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1932 to 1946. He served as pri ...

, who was appointed to the position on 6 July 1945 after the death of John Curtin

John Curtin (8 January 1885 – 5 July 1945) was an Australian politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Australia from 1941 until his death in 1945. He led the country for the majority of World War II, including all but the last few ...

, and served until 13 July 1945 when Ben Chifley

Joseph Benedict Chifley (; 22 September 1885 – 13 June 1951) was an Australian politician who served as the 16th prime minister of Australia from 1945 to 1949. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1945, follow ...

was elected leader of the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms the f ...

.

The most recent prime minister to serve out a full government term in the office was Scott Morrison

Scott John Morrison (; born 13 May 1968) is an Australian politician. He served as the 30th prime minister of Australia and as Leader of the Liberal Party of Australia from 2018 to 2022, and is currently the member of parliament (MP) for t ...

, who won the 2019 election and led his party to the 2022 election, but lost.

Lists of the 31 people who have so far held the premiership:

* List of prime ministers of Australia

* List of prime ministers of Australia by birthplace

* List of prime ministers of Australia by time in office

This is a list of prime ministers of Australia by time in office. The basis of the list is the inclusive number of days from being sworn in until leaving office, if counted by number of calendar days all the figures would be one greater.

Rank by ...

See also

*Historical rankings of prime ministers of Australia

Several surveys of academics and the general public have been conducted to evaluate and rank the performance of the prime ministers of Australia.

According to Paul Strangio of Monash University, there has been little academic interest in rankin ...

* List of Commonwealth heads of government

The Commonwealth Heads of Government (CHOG) is the collective name for the government leaders of the nations with membership in the Commonwealth of Nations. They are invited to attend Commonwealth Heads of Government Meetings every two years, ...

* List of prime ministers of Australia by time in office

This is a list of prime ministers of Australia by time in office. The basis of the list is the inclusive number of days from being sworn in until leaving office, if counted by number of calendar days all the figures would be one greater.

Rank by ...

* List of prime ministers of Elizabeth II

From becoming queen on 6 February 1952, Elizabeth II was head of state of 32 States headed by Elizabeth II, independent states; at the time of her death, there were 15 states, called Commonwealth realms. Within the Westminster system in each r ...

* Prime Ministers Avenue

The Prime Ministers Avenue is a collection of busts of the prime ministers of Australia, located at the Ballarat Botanical Gardens in Ballarat, Victoria. The busts are displayed as bronze portraits mounted on polished granite pedestals. It a ...

in Horse Chestnut Avenue in the Ballarat Botanical Gardens

The Ballarat Botanical Gardens Reserve, located on the western shore of picturesque Lake Wendouree, in Ballarat, Victoria, Australia, covers an area of 40 hectares which is divided into three distinct zones. The central Botanical Gardens reserve ...

contains a collection of bronze busts of former Australian prime ministers.

* Prime Ministers' Corridor of Oaks

The Prime Ministers' Corridor of Oaks is located at Faulconbridge, New South Wales, 75 km from Sydney and 20 minutes from Katoomba. It is near the Great Western Highway and Main Western railway line. It is also near the grave of Sir Henr ...

in Faulconbridge, New South Wales

Faulconbridge is a village located in the Blue Mountains 77 km west of Sydney, New South Wales and is 450 metres above sea level. At the 2016 census, Faulconbridge had a population of 4,025 people.

History and description

The Faulconbridg ...

contains a corridor of oaks of former Australian prime ministers.

* Prime Minister's XI

The Prime Minister's XI or PM's XI (formerly Australian Prime Minister's Invitation XI) is an invitational cricket team picked by the Prime Minister of Australia for an annual match held at the Manuka Oval in Canberra against an overseas touring ...

* Spouse of the prime minister of Australia

The spouse of the prime minister of Australia, or partner of the prime minister of Australia, is generally a high-profile individual who assists the Prime Minister of Australia, prime minister with ceremonial duties as well as performing variou ...

* Leader of the Opposition (Australia)

In Australian federal politics, the Leader of the Opposition is an elected member of parliament (MP) in the Australian House of Representatives who leads the opposition. The Leader of the Opposition, by convention, is the leader of the large ...

References

Further reading

* * * * * * *External links

Official website of the prime minister of Australia

Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet

Australia's Prime Ministers

– National Archives of Australia reference site and research portal

Biographies of Australia's Prime Ministers

/ National Museum of Australia

Classroom resources on Australian Prime Ministers

Museum of Australian Democracy website about Australian prime ministers

{{DEFAULTSORT:Prime Minister of Australia Lists of government ministers of Australia 1901 establishments in Australia