In

mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, the Pythagorean theorem or Pythagoras' theorem is a fundamental relation in

Euclidean geometry

Euclidean geometry is a mathematical system attributed to ancient Greek mathematics, Greek mathematician Euclid, which he described in his textbook on geometry, ''Euclid's Elements, Elements''. Euclid's approach consists in assuming a small set ...

between the three sides of a

right triangle

A right triangle or right-angled triangle, sometimes called an orthogonal triangle or rectangular triangle, is a triangle in which two sides are perpendicular, forming a right angle ( turn or 90 degrees).

The side opposite to the right angle i ...

. It states that the area of the

square

In geometry, a square is a regular polygon, regular quadrilateral. It has four straight sides of equal length and four equal angles. Squares are special cases of rectangles, which have four equal angles, and of rhombuses, which have four equal si ...

whose side is the

hypotenuse (the side opposite the

right angle

In geometry and trigonometry, a right angle is an angle of exactly 90 Degree (angle), degrees or radians corresponding to a quarter turn (geometry), turn. If a Line (mathematics)#Ray, ray is placed so that its endpoint is on a line and the ad ...

) is equal to the sum of the areas of the squares on the other two sides.

The

theorem

In mathematics and formal logic, a theorem is a statement (logic), statement that has been Mathematical proof, proven, or can be proven. The ''proof'' of a theorem is a logical argument that uses the inference rules of a deductive system to esta ...

can be written as an

equation

In mathematics, an equation is a mathematical formula that expresses the equality of two expressions, by connecting them with the equals sign . The word ''equation'' and its cognates in other languages may have subtly different meanings; for ...

relating the lengths of the sides , and the hypotenuse , sometimes called the Pythagorean equation:

:

The theorem is named for the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

philosopher

Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos (; BC) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher, polymath, and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of P ...

, born around 570 BC. The theorem has been

proved numerous times by many different methods – possibly the most for any mathematical theorem. The proofs are diverse, including both

geometric proofs and

algebraic proofs, with some dating back thousands of years.

When

Euclidean space

Euclidean space is the fundamental space of geometry, intended to represent physical space. Originally, in Euclid's ''Elements'', it was the three-dimensional space of Euclidean geometry, but in modern mathematics there are ''Euclidean spaces ...

is represented by a

Cartesian coordinate system

In geometry, a Cartesian coordinate system (, ) in a plane (geometry), plane is a coordinate system that specifies each point (geometry), point uniquely by a pair of real numbers called ''coordinates'', which are the positive and negative number ...

in

analytic geometry

In mathematics, analytic geometry, also known as coordinate geometry or Cartesian geometry, is the study of geometry using a coordinate system. This contrasts with synthetic geometry.

Analytic geometry is used in physics and engineering, and als ...

,

Euclidean distance

In mathematics, the Euclidean distance between two points in Euclidean space is the length of the line segment between them. It can be calculated from the Cartesian coordinates of the points using the Pythagorean theorem, and therefore is o ...

satisfies the Pythagorean relation: the squared distance between two points equals the sum of squares of the difference in each coordinate between the points.

The theorem can be

generalized in various ways: to

higher-dimensional space

In physics and mathematics, the dimension of a mathematical space (or object) is informally defined as the minimum number of coordinates needed to specify any point within it. Thus, a line has a dimension of one (1D) because only one coord ...

s, to

spaces that are not Euclidean, to objects that are not right triangles, and to objects that are not triangles at all but

-dimensional solids.

Proofs using constructed squares

Rearrangement proofs

In one rearrangement proof, two squares are used whose sides have a measure of

and which contain four right triangles whose sides are , and , with the hypotenuse being . In the square on the right side, the triangles are placed such that the corners of the square correspond to the corners of the right angle in the triangles, forming a square in the center whose sides are length . Each outer square has an area of

as well as

, with

representing the total area of the four triangles. Within the big square on the left side, the four triangles are moved to form two similar rectangles with sides of length and . These rectangles in their new position have now delineated two new squares, one having side length is formed in the bottom-left corner, and another square of side length formed in the top-right corner. In this new position, this left side now has a square of area

as well as

. Since both squares have the area of

it follows that the other measure of the square area also equal each other such that

=

. With the area of the four triangles removed from both side of the equation what remains is

In another proof rectangles in the second box can also be placed such that both have one corner that correspond to consecutive corners of the square. In this way they also form two boxes, this time in consecutive corners, with areas

and

which will again lead to a second square of with the area

.

English mathematician

Sir Thomas Heath gives this proof in his commentary on Proposition I.47 in

Euclid's ''

Elements'', and mentions the proposals of German mathematicians

Carl Anton Bretschneider and

Hermann Hankel

Hermann Hankel (14 February 1839 – 29 August 1873) was a German mathematician. Having worked on mathematical analysis during his career, he is best known for introducing the Hankel transform and the Hankel matrix.

Biography

Hankel was born on ...

that Pythagoras may have known this proof. Heath himself favors a different proposal for a Pythagorean proof, but acknowledges from the outset of his discussion "that the Greek literature which we possess belonging to the first five centuries after Pythagoras contains no statement specifying this or any other particular great geometric discovery to him." Recent scholarship has cast increasing doubt on any sort of role for Pythagoras as a creator of mathematics, although debate about this continues.

Algebraic proofs

The theorem can be proved algebraically using four copies of the same triangle arranged symmetrically around a square with side , as shown in the lower part of the diagram. This results in a larger square, with side and area . The four triangles and the square side must have the same area as the larger square,

:

giving

:

A similar proof uses four copies of a right triangle with sides , and , arranged inside a square with side as in the top half of the diagram.

[

] The triangles are similar with area

, while the small square has side and area . The area of the large square is therefore

:

But this is a square with side and area , so

:

:

Other proofs of the theorem

This theorem may have more known proofs than any other (the

law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

of

quadratic reciprocity

In number theory, the law of quadratic reciprocity is a theorem about modular arithmetic that gives conditions for the solvability of quadratic equations modulo prime numbers. Due to its subtlety, it has many formulations, but the most standard st ...

being another contender for that distinction); the book ''The Pythagorean Proposition'' contains 370 proofs.

Proof using similar triangles

This proof is based on the

proportionality of the sides of three

similar triangles, that is, upon the fact that the

ratio

In mathematics, a ratio () shows how many times one number contains another. For example, if there are eight oranges and six lemons in a bowl of fruit, then the ratio of oranges to lemons is eight to six (that is, 8:6, which is equivalent to the ...

of any two corresponding sides of similar triangles is the same regardless of the size of the triangles.

Let ''ABC'' represent a right triangle, with the

right angle

In geometry and trigonometry, a right angle is an angle of exactly 90 Degree (angle), degrees or radians corresponding to a quarter turn (geometry), turn. If a Line (mathematics)#Ray, ray is placed so that its endpoint is on a line and the ad ...

located at , as shown on the figure. Draw the

altitude

Altitude is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum (geodesy), datum and a point or object. The exact definition and reference datum varies according to the context (e.g., aviation, geometr ...

from point , and call its intersection with the side ''AB''. Point divides the length of the hypotenuse into parts and . The new triangle, ''ACH,'' is

similar to triangle ''ABC'', because they both have a right angle (by definition of the altitude), and they share the angle at , meaning that the third angle will be the same in both triangles as well, marked as in the figure. By a similar reasoning, the triangle ''CBH'' is also similar to ''ABC''. The proof of similarity of the triangles requires the

triangle postulate: The sum of the angles in a triangle is two right angles, and is equivalent to the

parallel postulate

In geometry, the parallel postulate is the fifth postulate in Euclid's ''Elements'' and a distinctive axiom in Euclidean geometry. It states that, in two-dimensional geometry:

If a line segment intersects two straight lines forming two interior ...

. Similarity of the triangles leads to the equality of ratios of corresponding sides:

:

The first result equates the

cosine

In mathematics, sine and cosine are trigonometric functions of an angle. The sine and cosine of an acute angle are defined in the context of a right triangle: for the specified angle, its sine is the ratio of the length of the side opposite that ...

s of the angles , whereas the second result equates their

sine

In mathematics, sine and cosine are trigonometric functions of an angle. The sine and cosine of an acute angle are defined in the context of a right triangle: for the specified angle, its sine is the ratio of the length of the side opposite th ...

s.

These ratios can be written as

:

Summing these two equalities results in

:

which, after simplification, demonstrates the Pythagorean theorem:

:

The role of this proof in history is the subject of much speculation. The underlying question is why Euclid did not use this proof, but invented another. One

conjecture

In mathematics, a conjecture is a conclusion or a proposition that is proffered on a tentative basis without proof. Some conjectures, such as the Riemann hypothesis or Fermat's conjecture (now a theorem, proven in 1995 by Andrew Wiles), ha ...

is that the proof by similar triangles involved a theory of proportions, a topic not discussed until later in the ''Elements'', and that the theory of proportions needed further development at that time.

Einstein's proof by dissection without rearrangement

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

gave a proof by dissection in which the pieces do not need to be moved. Instead of using a square on the hypotenuse and two squares on the legs, one can use any other shape that includes the hypotenuse, and two

similar shapes that each include one of two legs instead of the hypotenuse (see

Similar figures on the three sides). In Einstein's proof, the shape that includes the hypotenuse is the right triangle itself. The dissection consists of dropping a perpendicular from the vertex of the right angle of the triangle to the hypotenuse, thus splitting the whole triangle into two parts. Those two parts have the same shape as the original right triangle, and have the legs of the original triangle as their hypotenuses, and the sum of their areas is that of the original triangle. Because the ratio of the area of a right triangle to the square of its hypotenuse is the same for similar triangles, the relationship between the areas of the three triangles holds for the squares of the sides of the large triangle as well.

Euclid's proof

In outline, here is how the proof in

Euclid

Euclid (; ; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of geometry that largely domina ...

's ''

Elements'' proceeds. The large square is divided into a left and right rectangle. A triangle is constructed that has half the area of the left rectangle. Then another triangle is constructed that has half the area of the square on the left-most side. These two triangles are shown to be

congruent, proving this square has the same area as the left rectangle. This argument is followed by a similar version for the right rectangle and the remaining square. Putting the two rectangles together to reform the square on the hypotenuse, its area is the same as the sum of the area of the other two squares. The details follow.

Let , , be the

vertices of a right triangle, with a right angle at . Drop a perpendicular from to the side opposite the hypotenuse in the square on the hypotenuse. That line divides the square on the hypotenuse into two rectangles, each having the same area as one of the two squares on the legs.

For the formal proof, we require four elementary

lemmata:

# If two triangles have two sides of the one equal to two sides of the other, each to each, and the angles included by those sides equal, then the triangles are congruent (

side-angle-side).

# The area of a triangle is half the area of any parallelogram on the same base and having the same altitude.

# The area of a rectangle is equal to the product of two adjacent sides.

# The area of a square is equal to the product of two of its sides (follows from 3).

Next, each top square is related to a triangle congruent with another triangle related in turn to one of two rectangles making up the lower square.

The proof is as follows:

#Let ACB be a right-angled triangle with right angle CAB.

#On each of the sides BC, AB, and CA, squares are drawn, CBDE, BAGF, and ACIH, in that order. The construction of squares requires the immediately preceding theorems in Euclid, and depends upon the parallel postulate.

[

]

#From A, draw a line parallel to BD and CE. It will perpendicularly intersect BC and DE at K and L, respectively.

#Join CF and AD, to form the triangles BCF and BDA.

#Angles CAB and BAG are both right angles; therefore C, A, and G are

collinear

In geometry, collinearity of a set of Point (geometry), points is the property of their lying on a single Line (geometry), line. A set of points with this property is said to be collinear (sometimes spelled as colinear). In greater generality, t ...

.

#Angles CBD and FBA are both right angles; therefore angle ABD equals angle FBC, since both are the sum of a right angle and angle ABC.

#Since AB is equal to FB, BD is equal to BC and angle ABD equals angle FBC, triangle ABD must be congruent to triangle FBC.

#Since A-K-L is a straight line, parallel to BD, then rectangle BDLK has twice the area of triangle ABD because they share the base BD and have the same altitude BK, i.e., a line normal to their common base, connecting the parallel lines BD and AL. (lemma 2)

#Since C is collinear with A and G, and this line is parallel to FB, then square BAGF must be twice in area to triangle FBC.

#Therefore, rectangle BDLK must have the same area as square BAGF = AB

2.

#By applying steps 3 to 10 to the other side of the figure, it can be similarly shown that rectangle CKLE must have the same area as square ACIH = AC

2.

#Adding these two results, AB

2 + AC

2 = BD × BK + KL × KC

#Since BD = KL, BD × BK + KL × KC = BD(BK + KC) = BD × BC

#Therefore, AB

2 + AC

2 = BC

2, since CBDE is a square.

This proof, which appears in Euclid's ''Elements'' as that of Proposition 47 in Book 1, demonstrates that the area of the square on the hypotenuse is the sum of the areas of the other two squares.

This is quite distinct from the proof by similarity of triangles, which is conjectured to be the proof that Pythagoras used.

[

This proof first appeared after a computer program was set to check Euclidean proofs.][The proof by Pythagoras probably was not a general one, as the theory of proportions was developed only two centuries after Pythagoras; see ]

Proofs by dissection and rearrangement

Another by rearrangement is given by the middle animation. A large square is formed with area , from four identical right triangles with sides , and , fitted around a small central square. Then two rectangles are formed with sides and by moving the triangles. Combining the smaller square with these rectangles produces two squares of areas and , which must have the same area as the initial large square.

The third, rightmost image also gives a proof. The upper two squares are divided as shown by the blue and green shading, into pieces that when rearranged can be made to fit in the lower square on the hypotenuse – or conversely the large square can be divided as shown into pieces that fill the other two. This way of cutting one figure into pieces and rearranging them to get another figure is called

dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause of ...

. This shows the area of the large square equals that of the two smaller ones.

Proof by area-preserving shearing

As shown in the accompanying animation, area-preserving

shear mappings and translations can transform the squares on the sides adjacent to the right-angle onto the square on the hypotenuse, together covering it exactly. Each shear leaves the base and height unchanged, thus leaving the area unchanged too. The translations also leave the area unchanged, as they do not alter the shapes at all. Each square is first sheared into a parallelogram, and then into a rectangle which can be translated onto one section of the square on the hypotenuse.

Other algebraic proofs

A related

proof by U.S. President James A. Garfield was published before he was elected president; while he was a

U.S. Representative.

[

Published in a weekly mathematics column: as noted in and i]

A calendar of mathematical dates: April 1, 1876

by V. Frederick Rickey

Instead of a square it uses a

trapezoid

In geometry, a trapezoid () in North American English, or trapezium () in British English, is a quadrilateral that has at least one pair of parallel sides.

The parallel sides are called the ''bases'' of the trapezoid. The other two sides are ...

, which can be constructed from the square in the second of the above proofs by bisecting along a diagonal of the inner square, to give the trapezoid as shown in the diagram. The

area of the trapezoid can be calculated to be half the area of the square, that is

:

The inner square is similarly halved, and there are only two triangles so the proof proceeds as above except for a factor of

, which is removed by multiplying by two to give the result.

Proof using differentials

One can arrive at the Pythagorean theorem by studying how changes in a side produce a change in the hypotenuse and employing

calculus

Calculus is the mathematics, mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithmetic operations.

Originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the ...

.

[

][

]

The triangle ''ABC'' is a right triangle, as shown in the upper part of the diagram, with ''BC'' the hypotenuse. At the same time the triangle lengths are measured as shown, with the hypotenuse of length , the side ''AC'' of length and the side ''AB'' of length , as seen in the lower diagram part.

If is increased by a small amount ''dx'' by extending the side ''AC'' slightly to , then also increases by ''dy''. These form two sides of a triangle, ''CDE'', which (with chosen so ''CE'' is perpendicular to the hypotenuse) is a right triangle approximately similar to ''ABC''. Therefore, the ratios of their sides must be the same, that is:

:

This can be rewritten as

, which is a

differential equation that can be solved by direct integration:

:

giving

:

The constant can be deduced from , to give the equation

:

This is more of an intuitive proof than a formal one: it can be made more rigorous if proper limits are used in place of ''dx'' and ''dy''.

Converse

The

converse of the theorem is also true:

[

]

Given a triangle with sides of length , , and , if then the angle between sides and is a right angle

In geometry and trigonometry, a right angle is an angle of exactly 90 Degree (angle), degrees or radians corresponding to a quarter turn (geometry), turn. If a Line (mathematics)#Ray, ray is placed so that its endpoint is on a line and the ad ...

.

For any three positive

real numbers

In mathematics, a real number is a number that can be used to measurement, measure a continuous variable, continuous one-dimensional quantity such as a time, duration or temperature. Here, ''continuous'' means that pairs of values can have arbi ...

, , and such that , there exists a triangle with sides , and as a consequence of the

converse of the triangle inequality.

This converse appears in Euclid's ''Elements'' (Book I, Proposition 48): "If in a triangle the square on one of the sides equals the sum of the squares on the remaining two sides of the triangle, then the angle contained by the remaining two sides of the triangle is right."

It can be proved using the

law of cosines

In trigonometry, the law of cosines (also known as the cosine formula or cosine rule) relates the lengths of the sides of a triangle to the cosine of one of its angles. For a triangle with sides , , and , opposite respective angles , , and (see ...

or as follows:

Let ''ABC'' be a triangle with side lengths , , and , with Construct a second triangle with sides of length and containing a right angle. By the Pythagorean theorem, it follows that the hypotenuse of this triangle has length , the same as the hypotenuse of the first triangle. Since both triangles' sides are the same lengths , and , the triangles are

congruent and must have the same angles. Therefore, the angle between the side of lengths and in the original triangle is a right angle.

The above proof of the converse makes use of the Pythagorean theorem itself. The converse can also be proved without assuming the Pythagorean theorem.

A

corollary

In mathematics and logic, a corollary ( , ) is a theorem of less importance which can be readily deduced from a previous, more notable statement. A corollary could, for instance, be a proposition which is incidentally proved while proving another ...

of the Pythagorean theorem's converse is a simple means of determining whether a triangle is right, obtuse, or acute, as follows. Let be chosen to be the longest of the three sides and (otherwise there is no triangle according to the

triangle inequality

In mathematics, the triangle inequality states that for any triangle, the sum of the lengths of any two sides must be greater than or equal to the length of the remaining side.

This statement permits the inclusion of Degeneracy (mathematics)#T ...

). The following statements apply:

[

]

* If then the

triangle is right.

* If then the

triangle is acute.

* If then the

triangle is obtuse.

Edsger W. Dijkstra

Edsger Wybe Dijkstra ( ; ; 11 May 1930 – 6 August 2002) was a Dutch computer scientist, programmer, software engineer, mathematician, and science essayist.

Born in Rotterdam in the Netherlands, Dijkstra studied mathematics and physics and the ...

has stated this proposition about acute, right, and obtuse triangles in this language:

:

where is the angle opposite to side , is the angle opposite to side , is the angle opposite to side , and sgn is the

sign function

In mathematics, the sign function or signum function (from '' signum'', Latin for "sign") is a function that has the value , or according to whether the sign of a given real number is positive or negative, or the given number is itself zer ...

.

Consequences and uses of the theorem

Pythagorean triples

A Pythagorean triple has three positive integers , , and , such that In other words, a Pythagorean triple represents the lengths of the sides of a right triangle where all three sides have integer lengths.

[ Such a triple is commonly written Some well-known examples are and

A primitive Pythagorean triple is one in which , and are ]coprime

In number theory, two integers and are coprime, relatively prime or mutually prime if the only positive integer that is a divisor of both of them is 1. Consequently, any prime number that divides does not divide , and vice versa. This is equiv ...

(the greatest common divisor

In mathematics, the greatest common divisor (GCD), also known as greatest common factor (GCF), of two or more integers, which are not all zero, is the largest positive integer that divides each of the integers. For two integers , , the greatest co ...

of , and is 1).

The following is a list of primitive Pythagorean triples with values less than 100:

:(3, 4, 5), (5, 12, 13), (7, 24, 25), (8, 15, 17), (9, 40, 41), (11, 60, 61), (12, 35, 37), (13, 84, 85), (16, 63, 65), (20, 21, 29), (28, 45, 53), (33, 56, 65), (36, 77, 85), (39, 80, 89), (48, 55, 73), (65, 72, 97)

There are many formulas for generating Pythagorean triples. Of these, Euclid's formula is the most well-known: given arbitrary positive integers and , the formula states that the integers

:

forms a Pythagorean triple.

Inverse Pythagorean theorem

Given a right triangle

A right triangle or right-angled triangle, sometimes called an orthogonal triangle or rectangular triangle, is a triangle in which two sides are perpendicular, forming a right angle ( turn or 90 degrees).

The side opposite to the right angle i ...

with sides and altitude

Altitude is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum (geodesy), datum and a point or object. The exact definition and reference datum varies according to the context (e.g., aviation, geometr ...

(a line from the right angle and perpendicular to the hypotenuse ). The Pythagorean theorem has,

:

while the inverse Pythagorean theorem relates the two legs to the altitude ,

:

The equation can be transformed to,

:

where for any non-zero real . If the are to be integer

An integer is the number zero (0), a positive natural number (1, 2, 3, ...), or the negation of a positive natural number (−1, −2, −3, ...). The negations or additive inverses of the positive natural numbers are referred to as negative in ...

s, the smallest solution is then

:

using the smallest Pythagorean triple . The reciprocal Pythagorean theorem is a special case of the optic equation

In number theory, the optic equation is an equation that requires the sum of the multiplicative inverse, reciprocals of two positive integers and to equal the reciprocal of a third positive integer :Dickson, L. E., ''History of the Theory of N ...

:

where the denominators are squares and also for a heptagonal triangle whose sides are square numbers.

Incommensurable lengths

One of the consequences of the Pythagorean theorem is that line segments whose lengths are incommensurable (so the ratio of which is not a

One of the consequences of the Pythagorean theorem is that line segments whose lengths are incommensurable (so the ratio of which is not a rational number

In mathematics, a rational number is a number that can be expressed as the quotient or fraction of two integers, a numerator and a non-zero denominator . For example, is a rational number, as is every integer (for example,

The set of all ...

) can be constructed using a straightedge and compass

In geometry, straightedge-and-compass construction – also known as ruler-and-compass construction, Euclidean construction, or classical construction – is the construction of lengths, angles, and other geometric figures using only an ideali ...

. Pythagoras' theorem enables construction of incommensurable lengths because the hypotenuse of a triangle is related to the sides by the square root

In mathematics, a square root of a number is a number such that y^2 = x; in other words, a number whose ''square'' (the result of multiplying the number by itself, or y \cdot y) is . For example, 4 and −4 are square roots of 16 because 4 ...

operation.

The figure on the right shows how to construct line segments whose lengths are in the ratio of the square root of any positive integer.Quadratic irrational

In mathematics, a quadratic irrational number (also known as a quadratic irrational or quadratic surd) is an irrational number that is the solution to some quadratic equation with rational coefficients which is irreducible over the rational numb ...

.

Incommensurable lengths conflicted with the Pythagorean school's concept of numbers as only whole numbers. The Pythagorean school dealt with proportions by comparison of integer multiples of a common subunit.[

] According to one legend, Hippasus of Metapontum

Hippasus of Metapontum (; , ''Híppasos''; c. 530 – c. 450 BC) was a Greeks, Greek philosopher and early follower of Pythagoras. Little is known about his life or his beliefs, but he is sometimes credited with the discovery of the existence of ...

(''ca.'' 470 B.C.) was drowned at sea for making known the existence of the irrational or incommensurable.[

; Hippasus was on a voyage at the time, and his fellows cast him overboard. See

]

A careful discussion of Hippasus's contributions is found in Fritz

Fritz is a common German language, German male name. The name originated as a German diminutive of Friedrich (given name), Friedrich or Frederick (given name), Frederick (''Der Alte Fritz'', and ''Stary Fryc'' were common nicknames for King Fred ...

.[

]

Complex numbers

For any

For any complex number

In mathematics, a complex number is an element of a number system that extends the real numbers with a specific element denoted , called the imaginary unit and satisfying the equation i^= -1; every complex number can be expressed in the for ...

:

the absolute value

In mathematics, the absolute value or modulus of a real number x, is the non-negative value without regard to its sign. Namely, , x, =x if x is a positive number, and , x, =-x if x is negative (in which case negating x makes -x positive), ...

or modulus is given by

:

So the three quantities, , and are related by the Pythagorean equation,

:

Note that is defined to be a positive number or zero but and can be negative as well as positive. Geometrically is the distance of the from zero or the origin in the complex plane

In mathematics, the complex plane is the plane (geometry), plane formed by the complex numbers, with a Cartesian coordinate system such that the horizontal -axis, called the real axis, is formed by the real numbers, and the vertical -axis, call ...

.

This can be generalised to find the distance between two points, and say. The required distance is given by

:

so again they are related by a version of the Pythagorean equation,

:

Euclidean distance

The distance formula in Cartesian coordinates

In geometry, a Cartesian coordinate system (, ) in a plane is a coordinate system that specifies each point uniquely by a pair of real numbers called ''coordinates'', which are the signed distances to the point from two fixed perpendicular o ...

is derived from the Pythagorean theorem.Euclidean distance

In mathematics, the Euclidean distance between two points in Euclidean space is the length of the line segment between them. It can be calculated from the Cartesian coordinates of the points using the Pythagorean theorem, and therefore is o ...

, is given by

:

More generally, in Euclidean -space, the Euclidean distance between two points, and , is defined, by generalization of the Pythagorean theorem, as:

:

If instead of Euclidean distance, the square of this value (the squared Euclidean distance, or SED) is used, the resulting equation avoids square roots and is simply a sum of the SED of the coordinates:

:

The squared form is a smooth, convex function

In mathematics, a real-valued function is called convex if the line segment between any two distinct points on the graph of a function, graph of the function lies above or on the graph between the two points. Equivalently, a function is conve ...

of both points, and is widely used in optimization theory

Mathematical optimization (alternatively spelled ''optimisation'') or mathematical programming is the selection of a best element, with regard to some criteria, from some set of available alternatives. It is generally divided into two subfiel ...

and statistics

Statistics (from German language, German: ', "description of a State (polity), state, a country") is the discipline that concerns the collection, organization, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of data. In applying statistics to a s ...

, forming the basis of least squares

The method of least squares is a mathematical optimization technique that aims to determine the best fit function by minimizing the sum of the squares of the differences between the observed values and the predicted values of the model. The me ...

.

Euclidean distance in other coordinate systems

If Cartesian coordinates are not used, for example, if polar coordinates

In mathematics, the polar coordinate system specifies a given point (mathematics), point in a plane (mathematics), plane by using a distance and an angle as its two coordinate system, coordinates. These are

*the point's distance from a reference ...

are used in two dimensions or, in more general terms, if curvilinear coordinates

In geometry, curvilinear coordinates are a coordinate system for Euclidean space in which the coordinate lines may be curved. These coordinates may be derived from a set of Cartesian coordinates by using a transformation that is invertible, l ...

are used, the formulas expressing the Euclidean distance are more complicated than the Pythagorean theorem, but can be derived from it. A typical example where the straight-line distance between two points is converted to curvilinear coordinates can be found in the applications of Legendre polynomials in physics. The formulas can be discovered by using Pythagoras' theorem with the equations relating the curvilinear coordinates to Cartesian coordinates. For example, the polar coordinates can be introduced as:

:

Then two points with locations and are separated by a distance :

:

Performing the squares and combining terms, the Pythagorean formula for distance in Cartesian coordinates produces the separation in polar coordinates as:

:

using the trigonometric product-to-sum formulas. This formula is the law of cosines

In trigonometry, the law of cosines (also known as the cosine formula or cosine rule) relates the lengths of the sides of a triangle to the cosine of one of its angles. For a triangle with sides , , and , opposite respective angles , , and (see ...

, sometimes called the generalized Pythagorean theorem. From this result, for the case where the radii to the two locations are at right angles, the enclosed angle and the form corresponding to Pythagoras' theorem is regained: The Pythagorean theorem, valid for right triangles, therefore is a special case of the more general law of cosines, valid for arbitrary triangles.

Pythagorean trigonometric identity

In a right triangle with sides , and hypotenuse ,

In a right triangle with sides , and hypotenuse , trigonometry

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics concerned with relationships between angles and side lengths of triangles. In particular, the trigonometric functions relate the angles of a right triangle with ratios of its side lengths. The fiel ...

determines the sine

In mathematics, sine and cosine are trigonometric functions of an angle. The sine and cosine of an acute angle are defined in the context of a right triangle: for the specified angle, its sine is the ratio of the length of the side opposite th ...

and cosine

In mathematics, sine and cosine are trigonometric functions of an angle. The sine and cosine of an acute angle are defined in the context of a right triangle: for the specified angle, its sine is the ratio of the length of the side opposite that ...

of the angle between side and the hypotenuse as:

:

From that it follows:

:

where the last step applies Pythagoras' theorem. This relation between sine and cosine is sometimes called the fundamental Pythagorean trigonometric identity.[

] In similar triangles, the ratios of the sides are the same regardless of the size of the triangles, and depend upon the angles. Consequently, in the figure, the triangle with hypotenuse of unit size has opposite side of size and adjacent side of size in units of the hypotenuse.

Relation to the cross product

The Pythagorean theorem relates the

The Pythagorean theorem relates the cross product

In mathematics, the cross product or vector product (occasionally directed area product, to emphasize its geometric significance) is a binary operation on two vectors in a three-dimensional oriented Euclidean vector space (named here E), and ...

and dot product

In mathematics, the dot product or scalar productThe term ''scalar product'' means literally "product with a Scalar (mathematics), scalar as a result". It is also used for other symmetric bilinear forms, for example in a pseudo-Euclidean space. N ...

in a similar way:[

]

:

This can be seen from the definitions of the cross product and dot product, as

:

with n a unit vector

In mathematics, a unit vector in a normed vector space is a Vector (mathematics and physics), vector (often a vector (geometry), spatial vector) of Norm (mathematics), length 1. A unit vector is often denoted by a lowercase letter with a circumfle ...

normal to both a and b. The relationship follows from these definitions and the Pythagorean trigonometric identity.

This can also be used to define the cross product. By rearranging the following equation is obtained

:

This can be considered as a condition on the cross product and so part of its definition, for example in seven dimensions.[

][

]

As an axiom

If the first four of the Euclidean geometry axioms are assumed to be true then the Pythagorean theorem is equivalent to the fifth. That is, Euclid's fifth postulate implies the Pythagorean theorem and vice-versa.

Generalizations

Similar figures on the three sides

The Pythagorean theorem generalizes beyond the areas of squares on the three sides to any similar figures. This was known by Hippocrates of Chios

Hippocrates of Chios (; c. 470 – c. 421 BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician, geometer, and astronomer.

He was born on the isle of Chios, where he was originally a merchant. After some misadventures (he was robbed by either pirates or ...

in the 5th century BC, and was included by Euclid

Euclid (; ; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of geometry that largely domina ...

in his '' Elements'':[Euclid's ''Elements'': Book VI, Proposition VI 31: "In right-angled triangles the figure on the side subtending the right angle is equal to the similar and similarly described figures on the sides containing the right angle."]

If one erects similar figures (see Euclidean geometry

Euclidean geometry is a mathematical system attributed to ancient Greek mathematics, Greek mathematician Euclid, which he described in his textbook on geometry, ''Euclid's Elements, Elements''. Euclid's approach consists in assuming a small set ...

) with corresponding sides on the sides of a right triangle, then the sum of the areas of the ones on the two smaller sides equals the area of the one on the larger side.

This extension assumes that the sides of the original triangle are the corresponding sides of the three congruent figures (so the common ratios of sides between the similar figures are ''a:b:c'').[Putz, John F. and Sipka, Timothy A. "On generalizing the Pythagorean theorem", ''The College Mathematics Journal'' 34 (4), September 2003, pp. 291–295.] While Euclid's proof only applied to convex polygons, the theorem also applies to concave polygons and even to similar figures that have curved boundaries (but still with part of a figure's boundary being the side of the original triangle).[

The basic idea behind this generalization is that the area of a plane figure is proportional to the square of any linear dimension, and in particular is proportional to the square of the length of any side. Thus, if similar figures with areas , and are erected on sides with corresponding lengths , and then:

:

:

But, by the Pythagorean theorem, , so .

Conversely, if we can prove that for three similar figures without using the Pythagorean theorem, then we can work backwards to construct a proof of the theorem. For example, the starting center triangle can be replicated and used as a triangle on its hypotenuse, and two similar right triangles ( and ) constructed on the other two sides, formed by dividing the central triangle by its ]altitude

Altitude is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum (geodesy), datum and a point or object. The exact definition and reference datum varies according to the context (e.g., aviation, geometr ...

. The sum of the areas of the two smaller triangles therefore is that of the third, thus and reversing the above logic leads to the Pythagorean theorem . (''See also Einstein's proof by dissection without rearrangement'')

Law of cosines

The Pythagorean theorem is a special case of the more general theorem relating the lengths of sides in any triangle, the law of cosines, which states that

where is the angle between sides and .

The Pythagorean theorem is a special case of the more general theorem relating the lengths of sides in any triangle, the law of cosines, which states that

where is the angle between sides and .[

]

When is radians or 90°, then , and the formula reduces to the usual Pythagorean theorem.

Arbitrary triangle

At any selected angle of a general triangle of sides ''a, b, c'', inscribe an isosceles triangle such that the equal angles at its base θ are the same as the selected angle. Suppose the selected angle θ is opposite the side labeled . Inscribing the isosceles triangle forms triangle ''CAD'' with angle θ opposite side and with side along . A second triangle is formed with angle θ opposite side and a side with length along , as shown in the figure. Thābit ibn Qurra

Thābit ibn Qurra (full name: , , ; 826 or 836 – February 19, 901), was a scholar known for his work in mathematics, medicine, astronomy, and translation. He lived in Baghdad in the second half of the ninth century during the time of the Abba ...

stated that the sides of the three triangles were related as:[

][

]

:

As the angle θ approaches /2, the base of the isosceles triangle narrows, and lengths and overlap less and less. When , ''ADB'' becomes a right triangle, , and the original Pythagorean theorem is regained.

One proof observes that triangle ''ABC'' has the same angles as triangle ''CAD'', but in opposite order. (The two triangles share the angle at vertex A, both contain the angle θ, and so also have the same third angle by the triangle postulate.) Consequently, ''ABC'' is similar to the reflection of ''CAD'', the triangle ''DAC'' in the lower panel. Taking the ratio of sides opposite and adjacent to θ,

:

Likewise, for the reflection of the other triangle,

:

Clearing fractions and adding these two relations:

:

the required result.

The theorem remains valid if the angle is obtuse so the lengths and are non-overlapping.

General triangles using parallelograms

Pappus's area theorem is a further generalization, that applies to triangles that are not right triangles, using parallelograms on the three sides in place of squares (squares are a special case, of course). The upper figure shows that for a scalene triangle, the area of the parallelogram on the longest side is the sum of the areas of the parallelograms on the other two sides, provided the parallelogram on the long side is constructed as indicated (the dimensions labeled with arrows are the same, and determine the sides of the bottom parallelogram). This replacement of squares with parallelograms bears a clear resemblance to the original Pythagoras' theorem, and was considered a generalization by

Pappus's area theorem is a further generalization, that applies to triangles that are not right triangles, using parallelograms on the three sides in place of squares (squares are a special case, of course). The upper figure shows that for a scalene triangle, the area of the parallelogram on the longest side is the sum of the areas of the parallelograms on the other two sides, provided the parallelogram on the long side is constructed as indicated (the dimensions labeled with arrows are the same, and determine the sides of the bottom parallelogram). This replacement of squares with parallelograms bears a clear resemblance to the original Pythagoras' theorem, and was considered a generalization by Pappus of Alexandria

Pappus of Alexandria (; ; AD) was a Greek mathematics, Greek mathematician of late antiquity known for his ''Synagoge'' (Συναγωγή) or ''Collection'' (), and for Pappus's hexagon theorem in projective geometry. Almost nothing is known a ...

in 4 AD[For the details of such a construction, see ]

The lower figure shows the elements of the proof. Focus on the left side of the figure. The left green parallelogram has the same area as the left, blue portion of the bottom parallelogram because both have the same base and height . However, the left green parallelogram also has the same area as the left green parallelogram of the upper figure, because they have the same base (the upper left side of the triangle) and the same height normal to that side of the triangle. Repeating the argument for the right side of the figure, the bottom parallelogram has the same area as the sum of the two green parallelograms.

Solid geometry

In terms of

In terms of solid geometry

Solid geometry or stereometry is the geometry of Three-dimensional space, three-dimensional Euclidean space (3D space).

A solid figure is the region (mathematics), region of 3D space bounded by a two-dimensional closed surface; for example, a ...

, Pythagoras' theorem can be applied to three dimensions as follows. Consider the cuboid

In geometry, a cuboid is a hexahedron with quadrilateral faces, meaning it is a polyhedron with six Face (geometry), faces; it has eight Vertex (geometry), vertices and twelve Edge (geometry), edges. A ''rectangular cuboid'' (sometimes also calle ...

shown in the figure. The length of face diagonal ''AC'' is found from Pythagoras' theorem as:

:

where these three sides form a right triangle. Using diagonal ''AC'' and the horizontal edge ''CD'', the length of body diagonal ''AD'' then is found by a second application of Pythagoras' theorem as:

:

or, doing it all in one step:

:

This result is the three-dimensional expression for the magnitude of a vector v (the diagonal AD) in terms of its orthogonal components (the three mutually perpendicular sides):

:

This one-step formulation may be viewed as a generalization of Pythagoras' theorem to higher dimensions. However, this result is really just the repeated application of the original Pythagoras' theorem to a succession of right triangles in a sequence of orthogonal planes.

A substantial generalization of the Pythagorean theorem to three dimensions is de Gua's theorem, named for Jean Paul de Gua de Malves: If a tetrahedron

In geometry, a tetrahedron (: tetrahedra or tetrahedrons), also known as a triangular pyramid, is a polyhedron composed of four triangular Face (geometry), faces, six straight Edge (geometry), edges, and four vertex (geometry), vertices. The tet ...

has a right angle corner (like a corner of a cube

A cube or regular hexahedron is a three-dimensional space, three-dimensional solid object in geometry, which is bounded by six congruent square (geometry), square faces, a type of polyhedron. It has twelve congruent edges and eight vertices. It i ...

), then the square of the area of the face opposite the right angle corner is the sum of the squares of the areas of the other three faces. This result can be generalized as in the "-dimensional Pythagorean theorem":[

]

This statement is illustrated in three dimensions by the tetrahedron in the figure. The "hypotenuse" is the base of the tetrahedron at the back of the figure, and the "legs" are the three sides emanating from the vertex in the foreground. As the depth of the base from the vertex increases, the area of the "legs" increases, while that of the base is fixed. The theorem suggests that when this depth is at the value creating a right vertex, the generalization of Pythagoras' theorem applies. In a different wording:[

For an extended discussion of this generalization, see, for example]

Willie W. Wong

2002, ''A generalized n-dimensional Pythagorean theorem''.

Inner product spaces

The Pythagorean theorem can be generalized to

The Pythagorean theorem can be generalized to inner product space

In mathematics, an inner product space (or, rarely, a Hausdorff pre-Hilbert space) is a real vector space or a complex vector space with an operation called an inner product. The inner product of two vectors in the space is a scalar, ofte ...

s,[

] which are generalizations of the familiar 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional Euclidean spaces. For example, a function may be considered as a vector

Vector most often refers to:

* Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

* Disease vector, an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematics a ...

with infinitely many components in an inner product space, as in functional analysis

Functional analysis is a branch of mathematical analysis, the core of which is formed by the study of vector spaces endowed with some kind of limit-related structure (for example, Inner product space#Definition, inner product, Norm (mathematics ...

.[

]

In an inner product space, the concept of perpendicular

In geometry, two geometric objects are perpendicular if they intersect at right angles, i.e. at an angle of 90 degrees or π/2 radians. The condition of perpendicularity may be represented graphically using the '' perpendicular symbol'', � ...

ity is replaced by the concept of orthogonal

In mathematics, orthogonality (mathematics), orthogonality is the generalization of the geometric notion of ''perpendicularity''. Although many authors use the two terms ''perpendicular'' and ''orthogonal'' interchangeably, the term ''perpendic ...

ity: two vectors v and w are orthogonal if their inner product is zero. The inner product

In mathematics, an inner product space (or, rarely, a Hausdorff pre-Hilbert space) is a real vector space or a complex vector space with an operation called an inner product. The inner product of two vectors in the space is a scalar, ofte ...

is a generalization of the dot product

In mathematics, the dot product or scalar productThe term ''scalar product'' means literally "product with a Scalar (mathematics), scalar as a result". It is also used for other symmetric bilinear forms, for example in a pseudo-Euclidean space. N ...

of vectors. The dot product is called the ''standard'' inner product or the ''Euclidean'' inner product. However, other inner products are possible.[

]

The concept of length is replaced by the concept of the norm ‖v‖ of a vector v, defined as:[

]

:

In an inner-product space, the Pythagorean theorem states that for any two orthogonal vectors v and w we have

:

Here the vectors v and w are akin to the sides of a right triangle with hypotenuse given by the vector sum v + w. This form of the Pythagorean theorem is a consequence of the properties of the inner product:

:

where because of orthogonality.

A further generalization of the Pythagorean theorem in an inner product space to non-orthogonal vectors is the ''parallelogram law

In mathematics, the simplest form of the parallelogram law (also called the parallelogram identity) belongs to elementary geometry. It states that the sum of the squares of the lengths of the four sides of a parallelogram equals the sum of the s ...

'':[

:

which says that twice the sum of the squares of the lengths of the sides of a parallelogram is the sum of the squares of the lengths of the diagonals. Any norm that satisfies this equality is '' ipso facto'' a norm corresponding to an inner product.][

The Pythagorean identity can be extended to sums of more than two orthogonal vectors. If v1, v2, ..., v are pairwise-orthogonal vectors in an inner-product space, then application of the Pythagorean theorem to successive pairs of these vectors (as described for 3-dimensions in the section on ]solid geometry

Solid geometry or stereometry is the geometry of Three-dimensional space, three-dimensional Euclidean space (3D space).

A solid figure is the region (mathematics), region of 3D space bounded by a two-dimensional closed surface; for example, a ...

) results in the equation

Sets of ''m''-dimensional objects in ''n''-dimensional space

Another generalization of the Pythagorean theorem applies to Lebesgue-measurable sets of objects in any number of dimensions. Specifically, the square of the measure of an -dimensional set of objects in one or more parallel -dimensional flats in -dimensional Euclidean space

Euclidean space is the fundamental space of geometry, intended to represent physical space. Originally, in Euclid's ''Elements'', it was the three-dimensional space of Euclidean geometry, but in modern mathematics there are ''Euclidean spaces ...

is equal to the sum of the squares of the measures of the orthogonal

In mathematics, orthogonality (mathematics), orthogonality is the generalization of the geometric notion of ''perpendicularity''. Although many authors use the two terms ''perpendicular'' and ''orthogonal'' interchangeably, the term ''perpendic ...

projections of the object(s) onto all -dimensional coordinate subspaces.[

]

In mathematical terms:

:

where:

* is a measure in -dimensions (a length in one dimension, an area in two dimensions, a volume in three dimensions, etc.).

* is a set of one or more non-overlapping -dimensional objects in one or more parallel -dimensional flats in -dimensional Euclidean space.

* is the total measure (sum) of the set of -dimensional objects.

* represents an -dimensional projection of the original set onto an orthogonal coordinate subspace.

* is the measure of the -dimensional set projection onto -dimensional coordinate subspace . Because object projections can overlap on a coordinate subspace, the measure of each object projection in the set must be calculated individually, then measures of all projections added together to provide the total measure for the set of projections on the given coordinate subspace.

* is the number of orthogonal, -dimensional coordinate subspaces in -dimensional space () onto which the -dimensional objects are projected :

Non-Euclidean geometry

The Pythagorean theorem is derived from the axioms

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or f ...

of Euclidean geometry

Euclidean geometry is a mathematical system attributed to ancient Greek mathematics, Greek mathematician Euclid, which he described in his textbook on geometry, ''Euclid's Elements, Elements''. Euclid's approach consists in assuming a small set ...

, and in fact, were the Pythagorean theorem to fail for some right triangle, then the plane in which this triangle is contained cannot be Euclidean. More precisely, the Pythagorean theorem implies, and is implied by, Euclid's Parallel (Fifth) Postulate.[

][

] Thus, right triangles in a non-Euclidean geometry

In mathematics, non-Euclidean geometry consists of two geometries based on axioms closely related to those that specify Euclidean geometry. As Euclidean geometry lies at the intersection of metric geometry and affine geometry, non-Euclidean ge ...

[

]

do not satisfy the Pythagorean theorem. For example, in spherical geometry

300px, A sphere with a spherical triangle on it.

Spherical geometry or spherics () is the geometry of the two-dimensional surface of a sphere or the -dimensional surface of higher dimensional spheres.

Long studied for its practical applicati ...

, all three sides of the right triangle (say , , and ) bounding an octant of the unit sphere have length equal to /2, and all its angles are right angles, which violates the Pythagorean theorem because

.

Here two cases of non-Euclidean geometry are considered—spherical geometry

300px, A sphere with a spherical triangle on it.

Spherical geometry or spherics () is the geometry of the two-dimensional surface of a sphere or the -dimensional surface of higher dimensional spheres.

Long studied for its practical applicati ...

and hyperbolic plane geometry; in each case, as in the Euclidean case for non-right triangles, the result replacing the Pythagorean theorem follows from the appropriate law of cosines.

However, the Pythagorean theorem remains true in hyperbolic geometry and elliptic geometry if the condition that the triangle be right is replaced with the condition that two of the angles sum to the third, say . The sides are then related as follows: the sum of the areas of the circles with diameters and equals the area of the circle with diameter .

Spherical geometry

For any right triangle on a sphere of radius (for example, if in the figure is a right angle), with sides the relation between the sides takes the form:asymptotic expansion

In mathematics, an asymptotic expansion, asymptotic series or Poincaré expansion (after Henri Poincaré) is a formal series of functions which has the property that truncating the series after a finite number of terms provides an approximation ...

.

The Maclaurin series

Maclaurin or MacLaurin is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Colin Maclaurin (1698–1746), Scottish mathematician

* Normand MacLaurin (1835–1914), Australian politician and university administrator

* Henry Normand MacLaurin ...

for the cosine function can be written as with the remainder term in big O notation

Big ''O'' notation is a mathematical notation that describes the asymptotic analysis, limiting behavior of a function (mathematics), function when the Argument of a function, argument tends towards a particular value or infinity. Big O is a memb ...

. Letting be a side of the triangle, and treating the expression as an asymptotic expansion in terms of for a fixed ,

:

and likewise for and . Substituting the asymptotic expansion for each of the cosines into the spherical relation for a right triangle yields

:

Subtracting 1 and then negating each side,

:

Multiplying through by the asymptotic expansion for in terms of fixed and variable is

:

The Euclidean Pythagorean relationship is recovered in the limit, as the remainder vanishes when the radius approaches infinity.

For practical computation in spherical trigonometry with small right triangles, cosines can be replaced with sines using the double-angle identity to avoid loss of significance. Then the spherical Pythagorean theorem can alternately be written as

:

Hyperbolic geometry

In a

In a hyperbolic

Hyperbolic may refer to:

* of or pertaining to a hyperbola, a type of smooth curve lying in a plane in mathematics

** Hyperbolic geometry, a non-Euclidean geometry

** Hyperbolic functions, analogues of ordinary trigonometric functions, defined u ...

space with uniform Gaussian curvature

In differential geometry, the Gaussian curvature or Gauss curvature of a smooth Surface (topology), surface in three-dimensional space at a point is the product of the principal curvatures, and , at the given point:

K = \kappa_1 \kappa_2.

For ...

, for a right triangle

A triangle is a polygon with three corners and three sides, one of the basic shapes in geometry. The corners, also called ''vertices'', are zero-dimensional points while the sides connecting them, also called ''edges'', are one-dimension ...

with legs , , and hypotenuse , the relation between the sides takes the form:[

]

:

where cosh is the hyperbolic cosine. This formula is a special form of the hyperbolic law of cosines that applies to all hyperbolic triangles:[

]

:

with γ the angle at the vertex opposite the side .

By using the Maclaurin series

Maclaurin or MacLaurin is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Colin Maclaurin (1698–1746), Scottish mathematician

* Normand MacLaurin (1835–1914), Australian politician and university administrator

* Henry Normand MacLaurin ...

for the hyperbolic cosine, , it can be shown that as a hyperbolic triangle becomes very small (that is, as , , and all approach zero), the hyperbolic relation for a right triangle approaches the form of Pythagoras' theorem.

For small right triangles , the hyperbolic cosines can be eliminated to avoid loss of significance, giving

:

Very small triangles

For any uniform curvature (positive, zero, or negative), in very small right triangles (, ''K'', ''a''2, , ''K'', ''b''2 << 1) with hypotenuse , it can be shown that

:

Differential geometry

The Pythagorean theorem applies to

The Pythagorean theorem applies to infinitesimal

In mathematics, an infinitesimal number is a non-zero quantity that is closer to 0 than any non-zero real number is. The word ''infinitesimal'' comes from a 17th-century Modern Latin coinage ''infinitesimus'', which originally referred to the " ...

triangles seen in differential geometry

Differential geometry is a Mathematics, mathematical discipline that studies the geometry of smooth shapes and smooth spaces, otherwise known as smooth manifolds. It uses the techniques of Calculus, single variable calculus, vector calculus, lin ...

. In three dimensional space, the distance between two infinitesimally separated points satisfies

:

with ''ds'' the element of distance and (''dx'', ''dy'', ''dz'') the components of the vector separating the two points. Such a space is called a Euclidean space

Euclidean space is the fundamental space of geometry, intended to represent physical space. Originally, in Euclid's ''Elements'', it was the three-dimensional space of Euclidean geometry, but in modern mathematics there are ''Euclidean spaces ...

. However, in Riemannian geometry

Riemannian geometry is the branch of differential geometry that studies Riemannian manifolds, defined as manifold, smooth manifolds with a ''Riemannian metric'' (an inner product on the tangent space at each point that varies smooth function, smo ...

, a generalization of this expression useful for general coordinates (not just Cartesian) and general spaces (not just Euclidean) takes the form:metric tensor

In the mathematical field of differential geometry, a metric tensor (or simply metric) is an additional structure on a manifold (such as a surface) that allows defining distances and angles, just as the inner product on a Euclidean space allows ...

. (Sometimes, by abuse of language, the same term is applied to the set of coefficients .) It may be a function of position, and often describes curved space

Curved space often refers to a spatial geometry which is not "flat", where a '' flat space'' has zero curvature, as described by Euclidean geometry. Curved spaces can generally be described by Riemannian geometry, though some simple cases can be ...

. A simple example is Euclidean (flat) space expressed in curvilinear coordinates

In geometry, curvilinear coordinates are a coordinate system for Euclidean space in which the coordinate lines may be curved. These coordinates may be derived from a set of Cartesian coordinates by using a transformation that is invertible, l ...

. For example, in polar coordinates

In mathematics, the polar coordinate system specifies a given point (mathematics), point in a plane (mathematics), plane by using a distance and an angle as its two coordinate system, coordinates. These are

*the point's distance from a reference ...

:

:

History

There is debate whether the Pythagorean theorem was discovered once, or many times in many places, and the date of first discovery is uncertain, as is the date of the first proof. Historians of

There is debate whether the Pythagorean theorem was discovered once, or many times in many places, and the date of first discovery is uncertain, as is the date of the first proof. Historians of Mesopotamian

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary o ...

mathematics have concluded that the Pythagorean rule was in widespread use during the Old Babylonian period (20th to 16th centuries BC), over a thousand years before Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos (; BC) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher, polymath, and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of P ...

was born. The history of the theorem can be divided into four parts: knowledge of Pythagorean triples, knowledge of the relationship among the sides of a right triangle, knowledge of the relationships among adjacent angles, and proofs of the theorem within some deductive system

A formal system is an abstract structure and formalization of an axiomatic system used for deducing, using rules of inference, theorems from axioms.

In 1921, David Hilbert proposed to use formal systems as the foundation of knowledge in math ...

.

Written 1800BC, the Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

ian Middle Kingdom ''Berlin Papyrus 6619

The Berlin Papyrus 6619, simply called the Berlin Papyrus when the context makes it clear, is one of the primary sources of ancient Egyptian mathematics. One of the two mathematics problems on the Papyrus may suggest that the ancient Egyptians k ...

'' includes a problem whose solution is the Pythagorean triple 6:8:10, but the problem does not mention a triangle. The Mesopotamian tablet '' Plimpton 322'', written near Larsa

Larsa (, read ''Larsamki''), also referred to as Larancha/Laranchon (Gk. Λαραγχων) by Berossus, Berossos and connected with the biblical Arioch, Ellasar, was an important city-state of ancient Sumer, the center of the Cult (religious pra ...

also 1800BC, contains many entries closely related to Pythagorean triples.

In India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, the ''Baudhayana

The (Sanskrit: बौधायन सूत्रस् ) are a group of Vedic Sanskrit texts which cover dharma, daily ritual, mathematics and is one of the oldest Dharma-related texts of Hinduism that have survived into the modern age from th ...

Shulba Sutra'', the dates of which are given variously as between the 8th and 5th century BC, contains a list of Pythagorean triples and a statement of the Pythagorean theorem, both in the special case of the isosceles

In geometry, an isosceles triangle () is a triangle that has two sides of equal length and two angles of equal measure. Sometimes it is specified as having ''exactly'' two sides of equal length, and sometimes as having ''at least'' two sides ...

right triangle

A right triangle or right-angled triangle, sometimes called an orthogonal triangle or rectangular triangle, is a triangle in which two sides are perpendicular, forming a right angle ( turn or 90 degrees).

The side opposite to the right angle i ...

and in the general case, as does the '' Apastamba Shulba Sutra'' ().

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

Neoplatonic

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

philosopher and mathematician Proclus

Proclus Lycius (; 8 February 412 – 17 April 485), called Proclus the Successor (, ''Próklos ho Diádokhos''), was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, one of the last major classical philosophers of late antiquity. He set forth one of th ...

, writing in the fifth century AD, states two arithmetic rules, "one of them attributed to Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, the other to Pythagoras", for generating special Pythagorean triples. The rule attributed to Pythagoras () starts from an odd number

In mathematics, parity is the property of an integer of whether it is even or odd. An integer is even if it is divisible by 2, and odd if it is not.. For example, −4, 0, and 82 are even numbers, while −3, 5, 23, and 69 are odd numbers.

The ...

and produces a triple with leg and hypotenuse differing by one unit; the rule attributed to Plato (428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) starts from an even number and produces a triple with leg and hypotenuse differing by two units. According to Thomas L. Heath (1861–1940), no specific attribution of the theorem to Pythagoras exists in the surviving Greek literature from the five centuries after Pythagoras lived.Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

and Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

attributed the theorem to Pythagoras, they did so in a way which suggests that the attribution was widely known and undoubted.[: "Though this is the proposition universally associated by tradition with the name of Pythagoras, no really trustworthy evidence exists that it was actually discovered by him. The comparatively late writers who attribute it to him add the story that he sacrificed an ox to celebrate his discovery."][

An extensive discussion of the historical evidence is provided in]

page=351

/ref> Classicist

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

Kurt von Fritz

Karl Albert Kurt von Fritz (25 August 1900 in Metz – 16 July 1985 in Feldafing) was a German classical philologist.

Appointed to an extraordinary professorship for Greek at the University of Rostock in 1933, he was one of only two German prof ...

wrote, "Whether this formula is rightly attributed to Pythagoras personally ... one can safely assume that it belongs to the very oldest period of Pythagorean mathematics."[ Around 300 BC, in Euclid's ''Elements'', the oldest extant axiomatic proof of the theorem is presented.][

]

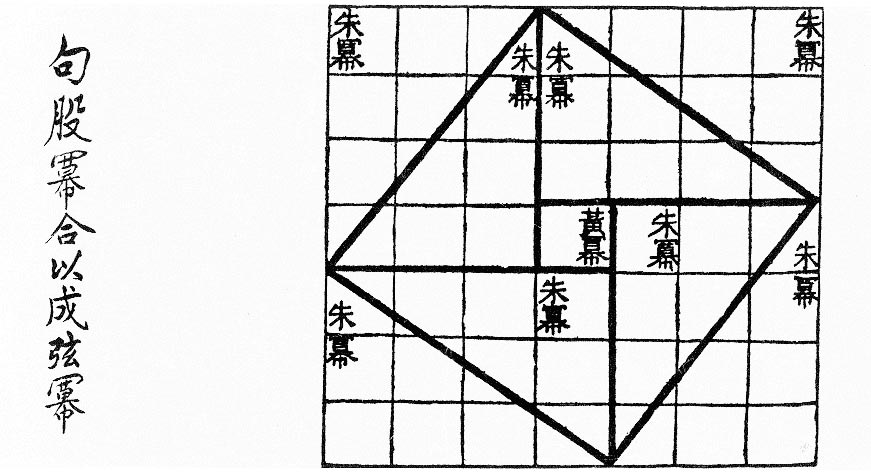

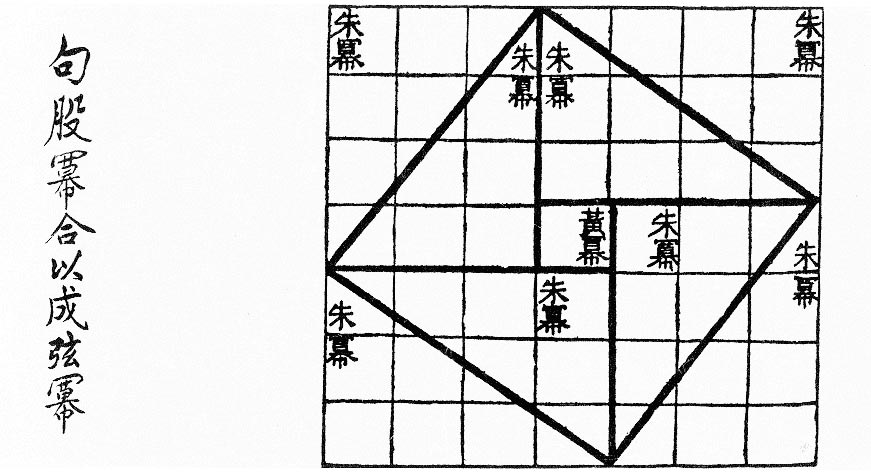

With contents known much earlier, but in surviving texts dating from roughly the 1st century BC, the Chinese text ''

With contents known much earlier, but in surviving texts dating from roughly the 1st century BC, the Chinese text ''Zhoubi Suanjing

The ''Zhoubi Suanjing'', also known by many other names, is an ancient Chinese astronomical and mathematical work. The ''Zhoubi'' is most famous for its presentation of Chinese cosmology and a form of the Pythagorean theorem. It claims to pr ...

'' (周髀算经), (''The Arithmetical Classic of the Gnomon and the Circular Paths of Heaven'') gives a reasoning for the Pythagorean theorem for the (3, 4, 5) triangle — in China it is called the "Gougu theorem" (勾股定理).[

][A rather extensive discussion of the origins of the various texts in the Zhou Bi is provided by ] During the Han Dynasty

The Han dynasty was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC9 AD, 25–220 AD) established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC ...

(202 BC to 220 AD), Pythagorean triples appear in ''The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art

''The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art'' is a Chinese mathematics book, composed by several generations of scholars from the 10th–2nd century BCE, its latest stage being from the 1st century CE. This book is one of the earliest surviving ...

'',[

This work is a compilation of 246 problems, some of which survived the book burning of 213 BC, and was put in final form before 100 AD. It was extensively commented upon by Liu Hui in 263 AD. See particularly §3: ''Nine chapters on the mathematical art'', pp. 71 ''ff''.

] together with a mention of right triangles.[

] Some believe the theorem arose first in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

in the 11th century BC,[

In particular, Li Jimin; see

] where it is alternatively known as the "Shang Gao theorem" (商高定理),[