Political history of the world on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The political history of the

The first states of sorts were those of early dynastic Sumer and early dynastic Egypt, which arose from the

The first states of sorts were those of early dynastic Sumer and early dynastic Egypt, which arose from the

Built around the

Built around the

world

In its most general sense, the term "world" refers to the totality of entities, to the whole of reality or to everything that is. The nature of the world has been conceptualized differently in different fields. Some conceptions see the worl ...

is the history of the various political entities

A polity is an identifiable political entity – a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources. A polity can be any other group of p ...

created by the human race

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

throughout their existence and the way these states define their borders. Throughout history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

, political systems have expanded from basic systems of self-governance

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

and monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

to the complex democratic and totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and regul ...

systems that exist today. In parallel, political entities have expanded from vaguely defined frontier-type boundaries, to the national definite boundaries existing today.

Prehistoric era

The primate ancestors of human beings already had social and political skills. The first forms of humansocial organization

In sociology, a social organization is a pattern of relationships between and among individuals and social groups.

Characteristics of social organization can include qualities such as sexual composition, spatiotemporal cohesion, leadership, s ...

were families

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideall ...

living in band societies

A band society, sometimes called a camp, or in older usage, a horde, is the simplest form of human society. A band generally consists of a small kin group, no larger than an extended family or clan. The general consensus of modern anthropology ...

as hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

s.

After the invention of agriculture

The Neolithic Revolution, or the (First) Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period from a lifestyle of hunter-gatherer, hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and sedentism, ...

around the same time (7,000-8,000 BCE) across various parts of the world, human societies started transitioning to tribal

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to conflic ...

forms of organization.

There is evidence of diplomacy between different tribes, but also of endemic warfare

__NOTOC__

Ritual warfare (sometimes called endemic warfare) is a state of continual or frequent warfare, such as is found in some tribal societies (but is not limited to tribal societies).

Description

Ritual fighting (or ritual battle or ritual ...

. This could have been caused by theft of livestock or crops, abduction of women

''Raptio'' (in archaic or literary English rendered as ''rape'') is a Latin term for the large-scale abduction of women, i.e. kidnapping for marriage, concubinage or sexual slavery. The equivalent German term is ''Frauenraub'' (literally ''wif ...

, or resource and status competition.

The Three-age system

The three-age system is the periodization of human pre-history (with some overlap into the historical periods in a few regions) into three time-periods: the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age; although the concept may also refer to o ...

of periodization

In historiography, periodization is the process or study of categorizing the past into discrete, quantified, and named blocks of time for the purpose of study or analysis.Adam Rabinowitz. It's about time: historical periodization and Linked Ancie ...

of prehistory

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use of ...

was first introduced for Scandinavia by Christian Jürgensen Thomsen

Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (29 December 1788 – 21 May 1865) was a Danish antiquarian who developed early archaeological techniques and methods.

In 1816 he was appointed head of 'antiquarian' collections which later developed into the Nati ...

in the 1830s. By the 1860s, it was embraced as a useful division of the "earliest history of mankind" in general and began to be applied in Assyriology

Assyriology (from Greek , ''Assyriā''; and , '' -logia'') is the archaeological, anthropological, and linguistic study of Assyria and the rest of ancient Mesopotamia (a region that encompassed what is now modern Iraq, northeastern Syria, southea ...

. The development of the now-conventional periodization in the archaeology of the Ancient Near East was developed in the 1920s to 1930s.

Ancient history

The early distribution of political power was determined by the availability offresh water

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does include ...

, fertile soil

Soil fertility refers to the ability of soil to sustain agricultural plant growth, i.e. to provide plant habitat and result in sustained and consistent yields of high quality.

, and temperate climate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

of different locations. These were all necessary for the development of highly organized societies. The locations of these early societies were near, or benefiting from, the edges of tectonic plates

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large te ...

. the Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

was located next to the Himalayas (which were created by tectonic pressures) and the Indus and Ganges rivers, which deposit sediment from the mountains to produce fertile land. A similar dynamic existed in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, where the Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

and Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

did the same with the Zagros Mountains

The Zagros Mountains ( ar, جبال زاغروس, translit=Jibal Zaghrus; fa, کوههای زاگرس, Kuh hā-ye Zāgros; ku, چیاکانی زاگرۆس, translit=Çiyakani Zagros; Turkish: ''Zagros Dağları''; Luri: ''Kuh hā-ye Zāgro ...

. Ancient Egypt was helped by the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

depositing sediments from the East African highlands of its origins, while the Yellow River

The Yellow River or Huang He (Chinese: , Standard Beijing Mandarin, Mandarin: ''Huáng hé'' ) is the second-longest river in China, after the Yangtze River, and the List of rivers by length, sixth-longest river system in the world at th ...

and Yangtze

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

acted in the same way for Ancient China. Eurasia was advantaged in the development of agriculture by the natural occurrence of domesticable wild grass species and the east-west orientation of the landmass, allowing for the easy spread of domesticated crops. A similar advantage was given to it by half of the world's large mammal species living there, which could be domesticated.

The development of agriculture allowed higher populations, with the newly dense and settled societies becoming hierarchical, with inequalities in wealth and freedom. As the cooling and drying of the climate by 3800 BCE caused drought in Mesopotamia, village farmers began co-operating and started creating larger settlements with irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow Crop, crops, Landscape plant, landscape plants, and Lawn, lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,00 ...

systems. This new water infrastructure in turn required centralised administration with complex social organisation. The first cities and systems of greater social organisation emerged in Mesopotamia, followed within a few centuries by ones at the Indus and Yellow River Valleys. In the cities, the workforce could specialise as the whole population did not have to work for food production, while stored food allowed for large armies to create empires. The first empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

s were those of Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

. Smaller kingdoms existed in North China Plain

The North China Plain or Huang-Huai-Hai Plain () is a large-scale downfaulted rift basin formed in the late Paleogene and Neogene and then modified by the deposits of the Yellow River. It is the largest alluvial plain of China. The plain is bord ...

, Indo-Gangetic Plain

The Indo-Gangetic Plain, also known as the North Indian River Plain, is a fertile plain encompassing northern regions of the Indian subcontinent, including most of northern and eastern India, around half of Pakistan, virtually all of Bangla ...

, Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

, Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, Eastern Mediterranean

Eastern Mediterranean is a loose definition of the eastern approximate half, or third, of the Mediterranean Sea, often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea.

It typically embraces all of that sea's coastal zones, referring to communi ...

, and Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

, while the rest of humanity continued to live in small tribes.

Middle East and the Mediterranean

The first states of sorts were those of early dynastic Sumer and early dynastic Egypt, which arose from the

The first states of sorts were those of early dynastic Sumer and early dynastic Egypt, which arose from the Uruk period

The Uruk period (ca. 4000 to 3100 BC; also known as Protoliterate period) existed from the protohistoric Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age period in the history of Mesopotamia, after the Ubaid period and before the Jemdet Nasr period. Named after ...

and Predynastic Egypt

Prehistoric Egypt and Predynastic Egypt span the period from the earliest human settlement to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period around 3100 BC, starting with the first Pharaoh, Narmer for some Egyptologists, Hor-Aha for others, with th ...

respectively at approximately 3000BCE. Early dynastic Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

was based around the Nile River

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest rive ...

in the north-east of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, the kingdom's boundaries being based around the Nile and stretching to areas where oases

In ecology, an oasis (; ) is a fertile area of a desert or semi-desert environment'ksar''with its surrounding feeding source, the palm grove, within a relational and circulatory nomadic system.”

The location of oases has been of critical imp ...

existed. Upper and Lower Egypt

Lower Egypt ( ar, مصر السفلى '; ) is the northernmost region of Egypt, which consists of the fertile Nile Delta between Upper Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea, from El Aiyat, south of modern-day Cairo, and Dahshur. Historically, ...

were unified around 3150 BCE by Pharaoh Menes

Menes (fl. c. 3200–3000 BC; ; egy, mnj, probably pronounced *; grc, Μήνης) was a pharaoh of the Early Dynastic Period of ancient Egypt credited by classical tradition with having united Upper and Lower Egypt and as the founder of the ...

. This process of consolidation was driven by the crowding of migrants from the expanding Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

in the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta ( ar, دلتا النيل, or simply , is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's largest river deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Po ...

. Nevertheless, political competition continued within the country between centers of power such as Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

and Thebes. The prevailing north-east trade winds made it easier to sail up the river, thereby helping the unification of the state. The geopolitical environment of the Egyptians had them surrounded by Nubia

Nubia () (Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), or ...

in the smaller southern oases of the Nile unreachable by boat, as well as by Libyan warlords operating from the oases around modern-day Benghazi

Benghazi () , ; it, Bengasi; tr, Bingazi; ber, Bernîk, script=Latn; also: ''Bengasi'', ''Benghasi'', ''Banghāzī'', ''Binghāzī'', ''Bengazi''; grc, Βερενίκη (''Berenice'') and ''Hesperides''., group=note (''lit. Son of he Ghazi ...

, and finally by raiders across the Sinai

Sinai commonly refers to:

* Sinai Peninsula, Egypt

* Mount Sinai, a mountain in the Sinai Peninsula, Egypt

* Biblical Mount Sinai, the site in the Bible where Moses received the Law of God

Sinai may also refer to:

* Sinai, South Dakota, a place ...

and the sea. The country was well defended by natural barriers formed by the Sahara on both sides, though this also limited its ability to expand into a larger empire, mostly remaining a regional power along the Nile (except for a conquest of the Levant in the second millennium BCE). The lack of timber also made it too expensive to build a large navy for power projection across the Mediterranean or Red Seas.

Mesopotamian dominance

Mesopotamia is situated between the major rivers ofTigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

and Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

, and the first political power in the region was the Akkadian Empire

The Akkadian Empire () was the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia after the long-lived civilization of Sumer. It was centered in the city of Akkad (city), Akkad () and its surrounding region. The empire united Akkadian language, Akkadian and ...

starting around 2300 BCE. They were preceded by Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of c ...

, and later followed by Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

, and Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

. They faced competition from the mountainous areas to the north, strategically positioned above the Mesopotamian plains, with kingdoms such as Mitanni

Mitanni (; Hittite cuneiform ; ''Mittani'' '), c. 1550–1260 BC, earlier called Ḫabigalbat in old Babylonian texts, c. 1600 BC; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat (''Hanikalbat'', ''Khanigalbat'', cuneiform ') in Assyrian records, or ''Naharin'' in ...

, Urartu

Urartu (; Assyrian: ',Eberhard Schrader, ''The Cuneiform inscriptions and the Old Testament'' (1885), p. 65. Babylonian: ''Urashtu'', he, אֲרָרָט ''Ararat'') is a geographical region and Iron Age kingdom also known as the Kingdom of Va ...

, Elam

Elam (; Linear Elamite: ''hatamti''; Cuneiform Elamite: ; Sumerian: ; Akkadian: ; he, עֵילָם ''ʿēlām''; peo, 𐎢𐎺𐎩 ''hūja'') was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretc ...

, and Medes

The Medes (Old Persian: ; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, the ...

. The Mesopotamians also innovated in governance by writing the first laws.

A dry climate in the Iron Age caused turmoil as movements of people put pressure on the existing states resulting in the Late Bronze Age collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse was a time of widespread societal collapse during the 12th century BC, between c. 1200 and 1150. The collapse affected a large area of the Eastern Mediterranean (North Africa and Southeast Europe) and the Near East ...

, with Cimmerians

The Cimmerians (Akkadian: , romanized: ; Hebrew: , romanized: ; Ancient Greek: , romanized: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic people originating in the Caspian steppe, part of whom subsequently migrated into West A ...

, Arameans

The Arameans ( oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; syc, ܐܪ̈ܡܝܐ, Ārāmāyē) were an ancient Semitic-speaking people in the Near East, first recorded in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. The Aramean ...

, Dorians

The Dorians (; el, Δωριεῖς, ''Dōrieîs'', singular , ''Dōrieús'') were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans, and Ionians) ...

, and the Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are a hypothesized seafaring confederation that attacked ancient Egypt and other regions in the East Mediterranean prior to and during the Late Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE).. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the Fren ...

migrating among others. Babylon never recovered following the death of Hammurabi

Hammurabi (Akkadian: ; ) was the sixth Amorite king of the Old Babylonian Empire, reigning from to BC. He was preceded by his father, Sin-Muballit, who abdicated due to failing health. During his reign, he conquered Elam and the city-states ...

in 1699 BCE. Following this, Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

grew in power under Adad-nirari II

Adad-nirari II (reigned from 911 to 891 BC) was the first King of Assyria in the Neo-Assyrian period.

Biography

Adad-nirari II's father was Ashur-dan II, whom he succeeded after a minor dynastic struggle. It is probable that the accession encour ...

. By the late ninth century BCE, the Assyrian Empire controlled almost all of Mesopotamia and much of the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

and Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. Meanwhile, Egypt was weakened, eventually breaking apart after the death of Osorkon II

Usermaatre Setepenamun Osorkon II was the fifth king of the Twenty-second Dynasty of Ancient Egypt and the son of King Takelot I and Queen Kapes. He ruled Egypt from approximately 872 BC to 837 BC from Tanis, the capital of that dynasty.

After ...

until 710 BCE. In 853, the Assyrians fought and won a battle against a coalition of Babylon, Egypt, Persia, Israel, Aram, and ten other nations, with over 60,000 troops taking part according to contemporary sources. However, the empire was weakened by internal struggles for power, and was plunged into a decade of turmoil beginning with a plague in 763 BCE. Following revolts by cities and lesser kingdoms against the empire, a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

was staged in 745 by Tiglath-Pileser III

Tiglath-Pileser III (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "my trust belongs to the son of Ešarra"), was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 745 BC to his death in 727. One of the most prominent and historically significant Assyrian kings, Tig ...

. He raised the army from 44,000 to 72,000, followed by his successor Sennacherib

Sennacherib (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynast ...

who raised it to 208,000, and finally by Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (Neo-Assyrian language, Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Ashur (god), Ashur is the creator of the heir") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BCE to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king o ...

who raised an army of over 300,000. This allowed the empire to spread over Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, the entire Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

, Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empires ...

, Urartu

Urartu (; Assyrian: ',Eberhard Schrader, ''The Cuneiform inscriptions and the Old Testament'' (1885), p. 65. Babylonian: ''Urashtu'', he, אֲרָרָט ''Ararat'') is a geographical region and Iron Age kingdom also known as the Kingdom of Va ...

, Cimmerians

The Cimmerians (Akkadian: , romanized: ; Hebrew: , romanized: ; Ancient Greek: , romanized: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic people originating in the Caspian steppe, part of whom subsequently migrated into West A ...

, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, Medes

The Medes (Old Persian: ; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, the ...

, Elam

Elam (; Linear Elamite: ''hatamti''; Cuneiform Elamite: ; Sumerian: ; Akkadian: ; he, עֵילָם ''ʿēlām''; peo, 𐎢𐎺𐎩 ''hūja'') was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretc ...

, and Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

.

Persian dominance

By 650, Assyria had started declining as a severe drought hit the Middle East and an alliance was formed against them. Eventually they were replaced by theMedian empire

The Medes (Old Persian: ; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, the ...

as the main power of the region following the Battle of Carchemish

The Battle of Carchemish was fought about 605 BC between the armies of Egypt allied with the remnants of the army of the former Assyrian Empire against the armies of Babylonia, allied with the Medes, Persians, and Scythians. This was while Nebuc ...

(605) and the Battle of the Eclipse

The Battle of the EclipseKevin Leloux: ''The Battle of the Eclipse (May 28, 585 BC): A Discussion of the Lydo-Median Treaty and the Halys Border.'' In: ''Polemos.'' Volume 19, no. 2, 2016, , pp. 31–54, in particular 37–39, 49online (or Battle ...

(585). The Medians served as the launching pad for the rise of the Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, wikt:𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎶, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an History of Iran#Classical antiquity, ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Bas ...

. After first serving as vassals, under the third Persian king Cambyses I

Cambyses I ( peo, 𐎣𐎲𐎢𐎪𐎡𐎹 ''Kabūjiya'') was king of Anshan (Persia), Anshan from c. 580 to 559 BC and the father of Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II), younger son of Cyrus I, and brother of Arukku. He should not be confus ...

their influence rose, and in 553 they rose against the Medians. By the death of Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

, the Persian Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

reached from Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

to Indus River

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

and Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

to Nubia

Nubia () (Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), or ...

. The empire was divided into provinces ruled by satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with consid ...

s, who collected taxes and were typically local power brokers. The empire controlled about a third of the world's farm land and a quarter of its population. In 522, after King Cambyses II's death, Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

took over power.

Greek dominance

As the population ofAncient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

grew, they began a colonization of the Mediterranean region. This encouraged trade, which in turn caused political changes in the city-states

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

with old elites being overthrown in Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part o ...

in 657 and in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

in 632, for example. There were many wars between the cities as well, including the Messenian Wars Messenian Wars refers to the wars between Messenia and Sparta in the 8th and 7th centuries BC as well as the 4th century BC.

*First Messenian War

*Second Messenian War

*Third Messenian War

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were ...

(743-742; 685-668), the Lelantine War

The Lelantine War was a military conflict between the two ancient Greek city states Chalcis and Eretria in Euboea which took place in the early Archaic period, between c. 710 and 650 BC. The reason for war was, according to tradition, the struggl ...

(710-650), and the First Sacred War

The First Sacred War, or Cirraean War, was fought between the Amphictyonic League of Delphi and the city of Kirrha. At the beginning of the 6th century BC the Pylaeo-Delphic Amphictyony, controlled by the Thessalians, attempted to take hold of the ...

(595-585). In the seventh and sixth centuries, Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part o ...

and Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

were the dominant powers of Greece. The former was eventually supplanted by Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

as the main sea power, while Sparta remained the dominant land-force. In 499, in the Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC. At the heart of the rebellion was the dissatisfac ...

Greek cities in Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

rebelled against the Persian Empire but were crushed in the Battle of Lade

The Battle of Lade ( grc, Ναυμαχία τῆς Λάδης, translit=Naumachia tēs Ladēs) was a naval battle which occurred during the Ionian Revolt, in 494 BC. It was fought between an alliance of the Ionian cities (joined by the Lesbi ...

. After this, the Persians invaded the Greek mainland

Greece is a country of the Balkans, in Southeastern Europe, bordered to the north by Albania, North Macedonia and Bulgaria; to the east by Turkey, and is surrounded to the east by the Aegean Sea, to the south by the Cretan and the Libyan Seas, an ...

in the Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

(499-449).

The Macedonian King Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

(350-336) conquered much of Greece. In 338, he formed the League of Corinth

The League of Corinth, also referred to as the Hellenic League (from Greek Ἑλληνικός ''Hellenikos'', "pertaining to Greece and Greeks"), was a confederation of Greek states created by Philip II in 338–337 BC. The League was created i ...

to liberate Greeks in Asia Minor from the Persians, with 10,000 troops invading in 336. After his murder, his son Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

took charge and crossed the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

in 334. After Asia Minor had been conquered, Alexander invaded Levant, Egypt, and Mesopotamia, defeating the Persians under Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

in the Battle of Gaugamela

The Battle of Gaugamela (; grc, Γαυγάμηλα, translit=Gaugámela), also called the Battle of Arbela ( grc, Ἄρβηλα, translit=Árbela), took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great a ...

in 331, and ending the last resistance by 328. After Alexander's death in Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

in 323, the Macedonian Empire

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by ...

had no designated successor. This led to its division into four: the Antigonid dynasty

The Antigonid dynasty (; grc-gre, Ἀντιγονίδαι) was a Hellenistic dynasty of Dorian Greek provenance, descended from Alexander the Great's general Antigonus I Monophthalmus ("the One-Eyed") that ruled mainly in Macedonia.

History

...

in Macedonia, the Attalid dynasty

The Kingdom of Pergamon or Attalid kingdom was a Ancient Greece, Greek state during the Hellenistic period that ruled much of the Western part of Anatolia, Asia Minor from its capital city of Pergamon. It was ruled by the Attalid dynasty (; g ...

in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, and the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

over Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

.

Roman dominance

TheRoman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

became dominant in the Mediterranean Basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and w ...

in the 3rd century BC after defeating the Samnites

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan-speaking people, who may have originated as an offshoot of the Sabines, they for ...

, the Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They s ...

and the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, rou ...

for control of the Italian Peninsula. In 264, it challenged its main rival Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

to a fight for Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, starting the Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars between 264 and 146BC fought between Roman Republic, Rome and Ancient Carthage, Carthage. Three conflicts between these states took place on both land and sea across the western Mediterranean region and i ...

. A truce was signed in 241, with Rome gaining Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

and Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

in addition to Sicily. In 218, the Carthaginian Army The term Carthaginian ( la, Carthaginiensis ) usually refers to a citizen of Ancient Carthage.

It can also refer to:

* Carthaginian (ship), a three-masted schooner built in 1921

* Insurgent privateer

Insurgent privateers ( es, corsarios insurgen ...

general Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Puni ...

marched out of Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

towards Italy, crossing the Alps with his war elephant

A war elephant was an elephant that was trained and guided by humans for combat. The war elephant's main use was to charge the enemy, break their ranks and instill terror and fear. Elephantry is a term for specific military units using elephant ...

s. After 15 years of fighting, the Roman republican army

The Roman army of the mid-Republic, also called the manipular Roman army or the Polybian army, refers to the armed forces deployed by the mid-Roman Republic, from the end of the Samnite Wars (290 BC) to the end of the Social War (91–88 BC), Soc ...

beat him and then sent troops against Carthage itself, defeating it in 202. The Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

alone cost Rome 100,000 casualties. In 146, Carthage was finally destroyed completely at the end of the Third Punic War

The Third Punic War (149–146 BC) was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between Carthage and Rome. The war was fought entirely within Carthaginian territory, in modern northern Tunisia. When the Second Punic War ended in 201 ...

.

Rome suffered from various internal disturbances and instabilities. In 133, Tiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus ( 163 – 133 BC) was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian law, agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also serve ...

was killed alongside hundreds of supporters after trying to redistribute public land

In all modern states, a portion of land is held by central or local governments. This is called public land, state land, or Crown land (Australia, and Canada). The system of tenure of public land, and the terminology used, varies between countrie ...

to the poor under the lex agraria

The ''Lex Agraria'' can refer to a Roman law proposed in 133 BC during the tribunate of Tiberius Gracchus. The law involved the redistribution of public land, previously owned by the senatorial class, to the lower classes in ancient Rome, using mo ...

. The Social War (91-88) was caused by neighbouring cities trying to secure themselves the benefits of Roman citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome (Latin: ''civitas'') was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in Ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, t ...

. In 82, general Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He won the first large-scale civil war in Roman history and became the first man of the Republic to seize power through force.

Sulla had ...

captured power violently, ending the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

and becoming a dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in times ...

. Following his death new power struggles emerged, and in Caesar's Civil War

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BC) was one of the last politico-military conflicts of the Roman Republic before its reorganization into the Roman Empire. It began as a series of political and military confrontations between Gaius Julius Caesar and ...

(49-46), Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

and Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

fought over the empire, with the former winning. After the assassination of Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar, the Roman dictator, was assassinated by a group of senators on the Ides of March (15 March) of 44 BC during a meeting of the Senate at the Curia of Pompey of the Theatre of Pompey in Rome where the senators stabbed Caesar 23 ti ...

in 44, a second civil war broke out between his potential heirs, Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autoc ...

and Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

, the latter gaining the new title of Roman emperor. This then led to the ''Pax Romana

The Pax Romana (Latin for 'Roman peace') is a roughly 200-year-long timespan of Roman history which is periodization, identified as a period and as a golden age (metaphor), golden age of increased as well as sustained Imperial cult of ancient Rome ...

'', a long period of peace in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

. The quarrels between the Ptolemaic Kingdom, the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

, the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe in conque ...

and the Kingdom of Pontus

Pontus ( grc-gre, Πόντος ) was a Hellenistic kingdom centered in the historical region of Pontus and ruled by the Mithridatic dynasty (of Persian origin), which possibly may have been directly related to Darius the Great of the Achaemeni ...

in the Near East allowed the Romans to expand up to the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

. During Augustus' reign the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

, Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

, and the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

became the other borders of the empire. The population reached about 60 million.

Political instability in Rome grew. Emperor Caligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germanicu ...

(37-41) was murdered by the Praetorian Guard

The Praetorian Guard (Latin: ''cohortēs praetōriae'') was a unit of the Imperial Roman army that served as personal bodyguards and intelligence agents for the Roman emperors. During the Roman Republic, the Praetorian Guard were an escort fo ...

to replace him with Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusu ...

(41-53), while his successor Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

(54-68) was rumored to have burned Rome down. The average reign from his death to Philip the Arab

Philip the Arab ( la, Marcus Julius Philippus "Arabs"; 204 – September 249) was Roman emperor from 244 to 249. He was born in Aurantis, Arabia, in a city situated in modern-day Syria. After the death of Gordian III in February 244, Philip ...

(244-249) was six years. Nevertheless, external expansion continued, with Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

(98-117) invading Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It thus r ...

, Parthia

Parthia ( peo, 𐎱𐎼𐎰𐎺 ''Parθava''; xpr, 𐭐𐭓𐭕𐭅 ''Parθaw''; pal, 𐭯𐭫𐭮𐭥𐭡𐭥 ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Med ...

and Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

. Its only formidable enemy was the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe in conque ...

. Migrating peoples started exerting pressure on the borders of the empire in the Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roman ...

. The drying climate of Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

forced the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

to move, and in 370 they crossed Don

Don, don or DON and variants may refer to:

Places

*County Donegal, Ireland, Chapman code DON

*Don (river), a river in European Russia

*Don River (disambiguation), several other rivers with the name

*Don, Benin, a town in Benin

*Don, Dang, a vill ...

and soon after the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

, forcing the Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

on the move, which in turn caused other Germanic tribes

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

to overrun Roman borders. In 293, Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

(284-305) appointed three rulers for different parts of the empire. It was formally divided in 395 by Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

(379-395) into the Western Roman

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period fr ...

and Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

s. In 406 the northern border of the former was overrun by the Alemanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni, were a confederation of Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Caracalla of 213, the Alemanni captured the in 260, and later expanded into pres ...

, Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

and Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own names ...

. In 408 the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

invaded Italy and then sacked Rome in 410. The final collapse of the Western Empire came in 476 with the deposal of Romulus Augustulus

Romulus Augustus ( 465 – after 511), nicknamed Augustulus, was Roman emperor of the West from 31 October 475 until 4 September 476. Romulus was placed on the imperial throne by his father, the ''magister militum'' Orestes, and, at that time, ...

(475-476).

Indian subcontinent

Built around the

Built around the Indus River

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

, by 2500 BCE the Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

, located in modern-day India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, had formed. The civilization's boundaries extended to 600 km from the Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea ( ar, اَلْبَحرْ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Bahr al-ˁArabī) is a region of the northern Indian Ocean bounded on the north by Pakistan, Iran and the Gulf of Oman, on the west by the Gulf of Aden, Guardafui Channel ...

. After its cities Mohenjo-daro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a mode ...

were abandoned around 1900 BCE, no political power is known to have replaced it.

States began to form in 12th century BCE with the formation of Kuru Kingdom

Kuru (Sanskrit: ) was a Vedic Indo-Aryan peoples, Indo-Aryan tribal union in northern Iron Age India, Iron Age India, encompassing parts of the modern-day states of Haryana, Delhi, and some parts of western Uttar Pradesh, which appeared in the M ...

which was first state level administration in Indian subcontinent. In 6th century BCE with the emergence of Mahajanapadas

The Mahājanapadas ( sa, great realm, from ''maha'', "great", and '' janapada'' "foothold of a people") were sixteen kingdoms or oligarchic republics that existed in ancient India from the sixth to fourth centuries BCE during the second urban ...

. Out of sixteen such states, four strong ones emerged: Kosala

The Kingdom of Kosala (Sanskrit: ) was an ancient Indian kingdom with a rich culture, corresponding to the area within the region of Awadh in present-day Uttar Pradesh to Western Odisha. It emerged as a janapada, small state during the late Ve ...

, Magadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

, Vatsa

Vatsa or Vamsa (Pali and Ardhamagadhi: , literally "calf") was one of the sixteen Mahajanapadas (great kingdoms) of Uttarapatha of ancient India mentioned in the Aṅguttara Nikāya.

Location

The territory of Vatsa was located to the south of ...

, and Avanti, with Magadha dominating the rest by the mid-fifth century. The Magadha then transformed into the Nanda Empire

The Nanda dynasty ruled in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent during the fourth century BCE, and possibly during the fifth century BCE. The Nandas overthrew the Shaishunaga dynasty in the Magadha region of eastern India, and expanded ...

under Mahapadma Nanda

Mahapadma Nanda (IAST: ''Mahāpadmānanda''; c. mid 4th century BCE), according to the Puranas, was the first Emperor of the Nanda Empire of ancient India. The Puranas describe him as a son of the last Shaishunaga king Mahanandin and a Shudra w ...

(345-321), extending from the Gangetic plains

The Indo-Gangetic Plain, also known as the North Indian River Plain, is a fertile plain encompassing northern regions of the Indian subcontinent, including most of northern and eastern India, around half of Pakistan, virtually all of Ba ...

to the Hindu Kush

The Hindu Kush is an mountain range in Central and South Asia to the west of the Himalayas. It stretches from central and western Afghanistan, Quote: "The Hindu Kush mountains run along the Afghan border with the North-West Frontier Provinc ...

and the Deccan Plateau

The large Deccan Plateau in southern India is located between the Western Ghats and the Eastern Ghats, and is loosely defined as the peninsular region between these ranges that is south of the Narmada river. To the north, it is bounded by the ...

. The empire was, however, overtaken by Chandragupta Maurya

Chandragupta Maurya (350-295 BCE) was a ruler in Ancient India who expanded a geographically-extensive kingdom based in Magadha and founded the Maurya dynasty. He reigned from 320 BCE to 298 BCE. The Maurya kingdom expanded to become an empi ...

(324-298), turning it into the Maurya Empire

The Maurya Empire, or the Mauryan Empire, was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in the Indian subcontinent based in Magadha, having been founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until 1 ...

. He defended against Alexander's invasion from the West and received control of the Hindu Kush mountain passes in a peace treaty signed in 303. By the time of his grandson Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

's rule, the empire stretched from Zagros Mountains

The Zagros Mountains ( ar, جبال زاغروس, translit=Jibal Zaghrus; fa, کوههای زاگرس, Kuh hā-ye Zāgros; ku, چیاکانی زاگرۆس, translit=Çiyakani Zagros; Turkish: ''Zagros Dağları''; Luri: ''Kuh hā-ye Zāgro ...

to the Brahmaputra River

The Brahmaputra is a trans-boundary river which flows through Tibet, northeast India, and Bangladesh. It is also known as the Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibetan, the Siang/Dihang River in Arunachali, Luit in Assamese, and Jamuna River in Bangla. It ...

. The empire contained a population of 50 to 60 million, governed by a system of provinces ruled by governor-princes, with a capital in Pataliputra

Pataliputra (IAST: ), adjacent to modern-day Patna, was a city in ancient India, originally built by Magadha ruler Ajatashatru in 490 BCE as a small fort () near the Ganges river.. Udayin laid the foundation of the city of Pataliputra at the ...

.

After Ashoka's death, the empire had begun to decline, with Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

in the north, Shunga

is a type of Japanese erotic art typically executed as a kind of ukiyo-e, often in woodblock print format. While rare, there are also extant erotic painted handscrolls which predate ukiyo-e. Translated literally, the Japanese word ''shunga' ...

and Satavahana

The Satavahanas (''Sādavāhana'' or ''Sātavāhana'', IAST: ), also referred to as the Andhras in the Puranas, were an ancient Indian dynasty based in the Deccan region. Most modern scholars believe that the Satavahana rule began in the late ...

in the centre, and Kalinga Kalinga may refer to:

Geography, linguistics and/or ethnology

* Kalinga (historical region), a historical region of India

** Kalinga (Mahabharata), an apocryphal kingdom mentioned in classical Indian literature

** Kalinga script, an ancient writ ...

as well as Pandya in the south becoming independent. In to this power vacuum

In political science and political history, the term power vacuum, also known as a power void, is an analogy between a physical vacuum to the political condition "when someone in a place of power, has lost control of something and no one has repla ...

, the Yuezhi

The Yuezhi (;) were an ancient people first described in Chinese histories as nomadic pastoralists living in an arid grassland area in the western part of the modern Chinese province of Gansu, during the 1st millennium BC. After a major defeat ...

were able to establish the new Kushan Empire

The Kushan Empire ( grc, Βασιλεία Κοσσανῶν; xbc, Κυϸανο, ; sa, कुषाण वंश; Brahmi: , '; BHS: ; xpr, 𐭊𐭅𐭔𐭍 𐭇𐭔𐭕𐭓, ; zh, 貴霜 ) was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi, i ...

in 30 CE. The Gupta Empire

The Gupta Empire was an ancient Indian empire which existed from the early 4th century CE to late 6th century CE. At its zenith, from approximately 319 to 467 CE, it covered much of the Indian subcontinent. This period is considered as the Gol ...

was founded by Chandragupta I

Chandragupta I ( Gupta script: ''Cha-ndra-gu-pta'', r. c. 319–335 or 319–350 CE) was a king of the Gupta Empire, who ruled in northern and central India. His title ''Maharajadhiraja'' ("great king of kings") suggests that he was the firs ...

(320-335), which in sixty years expanded from the Ganges

The Ganges ( ) (in India: Ganga ( ); in Bangladesh: Padma ( )). "The Ganges Basin, known in India as the Ganga and in Bangladesh as the Padma, is an international river to which India, Bangladesh, Nepal and China are the riparian states." is ...

to the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, bounded on the west and northwest by India, on the north by Bangladesh, and on the east by Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India. Its southern limit is a line between ...

and the Indus River

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

following the downfall of the Kushan Empire. Gupta governance was similar to that of the Maurya. Following wars with the Hephthalites

The Hephthalites ( xbc, ηβοδαλο, translit= Ebodalo), sometimes called the White Huns (also known as the White Hunas, in Iranian as the ''Spet Xyon'' and in Sanskrit as the ''Sveta-huna''), were a people who lived in Central Asia during th ...

and other problems, the empire fell by 550.

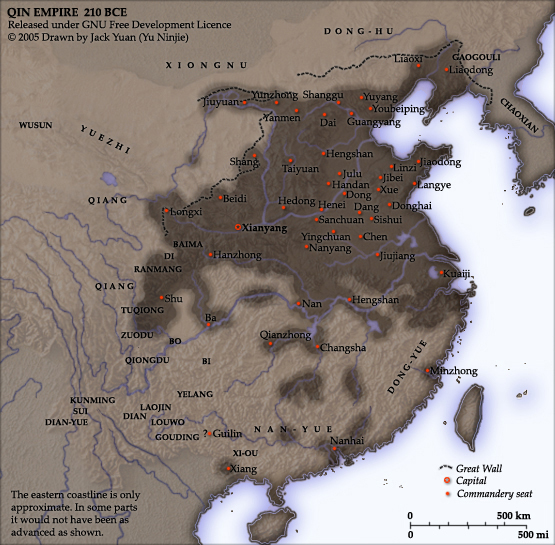

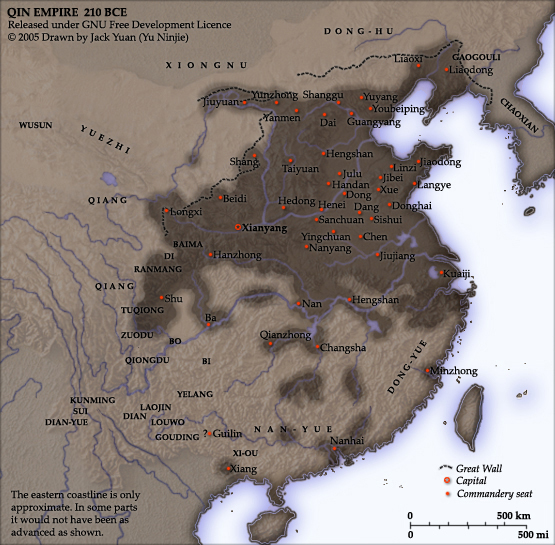

China

In theNorth China Plain

The North China Plain or Huang-Huai-Hai Plain () is a large-scale downfaulted rift basin formed in the late Paleogene and Neogene and then modified by the deposits of the Yellow River. It is the largest alluvial plain of China. The plain is bord ...

, the Yellow River

The Yellow River or Huang He (Chinese: , Standard Beijing Mandarin, Mandarin: ''Huáng hé'' ) is the second-longest river in China, after the Yangtze River, and the List of rivers by length, sixth-longest river system in the world at th ...

allowed the rise of states such as Wei and Qi. This area was first unified by the Shang dynasty

The Shang dynasty (), also known as the Yin dynasty (), was a Chinese royal dynasty founded by Tang of Shang (Cheng Tang) that ruled in the Yellow River valley in the second millennium BC, traditionally succeeding the Xia dynasty and ...

around 1600 BCE, and replaced by the Zhou dynasty

The Zhou dynasty ( ; Old Chinese ( B&S): *''tiw'') was a royal dynasty of China that followed the Shang dynasty. Having lasted 789 years, the Zhou dynasty was the longest dynastic regime in Chinese history. The military control of China by th ...

in the Battle of Muye

The Battle of Muye () or Battle of the Mu was a battle fought in ancient China between the rebel Zhou state and the reigning Shang dynasty. The Zhou army, led by Wu of Zhou, defeated the defending army of King Di Xin of Shang at Muye and capt ...

in 1046 BCE, with reportedly millions taking part in the fighting. The victors were however hit by internal unrest soon after. The main rivals of the Zhou were the Dongyi

The Dongyi or Eastern Yi () was a collective term for ancient peoples found in Chinese records. The definition of Dongyi varied across the ages, but in most cases referred to inhabitants of eastern China, then later, the Korean peninsula, and Ja ...

in Shandong

Shandong ( , ; ; alternately romanized as Shantung) is a coastal province of the People's Republic of China and is part of the East China region.

Shandong has played a major role in Chinese history since the beginning of Chinese civilizati ...

, the Xianyun

The Xianyun (; Old Chinese: ( ZS) *''g.ramʔ-lunʔ''; (Schuessler) *''hɨamᴮ-juinᴮ'' < *''hŋamʔ-junʔ'') was an ancient nomadic tribe that invaded the in

When

When

In 711, the

In 711, the

The gunpowder empires were the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman, Safavid Iran, Safavid, and Mughal Empire, Mughal empires as they flourished from the 16th century to the 18th century. These three empires were among the strongest and most stable economies of the early modern period, leading to commercial expansion, and greater patronage of culture, while their political and legal institutions were consolidated with an increasing degree of centralisation. The empires underwent a significant increase in per capita income and population, and a sustained pace of technological innovation. They stretched from Central Europe and North Africa in the west to between today's modern Bangladesh and Myanmar in the east.

Under Sultan Selim I (1512–1520), the Ottomans defeated the Safavids in the Battle of Chaldiran (1514). His successor, Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–1566), the Ottoman Empire marked the peak of its power and prosperity as well as the highest development of its government, social, and economic systems. Already controlling the Balkans, it was able to invade Hungary and win in the Battle of Mohács (1526). However, further advancement failed after the Siege of Vienna (1529). Following naval victories in the Battle of Preveza (1538) and the Battle of Djerba (1560), the Ottomans also emerged as the dominant maritime power in the Mediterranean. A sailing voyage even reached the Aceh Sultanate in 1565. At the beginning of the 17th century, the empire contained Provinces of the Ottoman Empire, 32 provinces and numerous Vassal and tributary states of the Ottoman Empire, vassal states. Some of these were later absorbed into the Ottoman Empire, while others were granted various types of autonomy over the course of centuries.The empire also temporarily gained authority over distant overseas lands through declarations of allegiance to the Ottoman dynasty, Ottoman Sultan and Caliph, such as the Ottoman expedition to Aceh, declaration by the Sultan of Aceh in 1565, or through temporary acquisitions of islands such as Lanzarote in the Atlantic Ocean in 1585

The gunpowder empires were the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman, Safavid Iran, Safavid, and Mughal Empire, Mughal empires as they flourished from the 16th century to the 18th century. These three empires were among the strongest and most stable economies of the early modern period, leading to commercial expansion, and greater patronage of culture, while their political and legal institutions were consolidated with an increasing degree of centralisation. The empires underwent a significant increase in per capita income and population, and a sustained pace of technological innovation. They stretched from Central Europe and North Africa in the west to between today's modern Bangladesh and Myanmar in the east.

Under Sultan Selim I (1512–1520), the Ottomans defeated the Safavids in the Battle of Chaldiran (1514). His successor, Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–1566), the Ottoman Empire marked the peak of its power and prosperity as well as the highest development of its government, social, and economic systems. Already controlling the Balkans, it was able to invade Hungary and win in the Battle of Mohács (1526). However, further advancement failed after the Siege of Vienna (1529). Following naval victories in the Battle of Preveza (1538) and the Battle of Djerba (1560), the Ottomans also emerged as the dominant maritime power in the Mediterranean. A sailing voyage even reached the Aceh Sultanate in 1565. At the beginning of the 17th century, the empire contained Provinces of the Ottoman Empire, 32 provinces and numerous Vassal and tributary states of the Ottoman Empire, vassal states. Some of these were later absorbed into the Ottoman Empire, while others were granted various types of autonomy over the course of centuries.The empire also temporarily gained authority over distant overseas lands through declarations of allegiance to the Ottoman dynasty, Ottoman Sultan and Caliph, such as the Ottoman expedition to Aceh, declaration by the Sultan of Aceh in 1565, or through temporary acquisitions of islands such as Lanzarote in the Atlantic Ocean in 1585