Money supply on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

In recent years, some academic economists renowned for their work on the implications of

In recent years, some academic economists renowned for their work on the implications of

:''See also

:''See also

Federal Reserve, November 10, 2005, revised March 9, 2006. However, there are still estimates produced by various private institutions. * MZM: Money with zero maturity. It measures the supply of financial assets redeemable at par on demand.

In 1967, when sterling was devalued, the

In 1967, when sterling was devalued, the

The Bank of Japan defines the monetary aggregates as:

* M1: cash currency in circulation, plus deposit money

* M2 + CDs: M1 plus

The Bank of Japan defines the monetary aggregates as:

* M1: cash currency in circulation, plus deposit money

* M2 + CDs: M1 plus

There are just two official UK measures. M0 is referred to as the "wide

There are just two official UK measures. M0 is referred to as the "wide

The

The

The United States

The United States

The

The

The

The

The

The

The monetary value of assets, goods, and services sold during the year could be grossly estimated using nominal

The monetary value of assets, goods, and services sold during the year could be grossly estimated using nominal

Speech, Bernanke – The Great Moderation

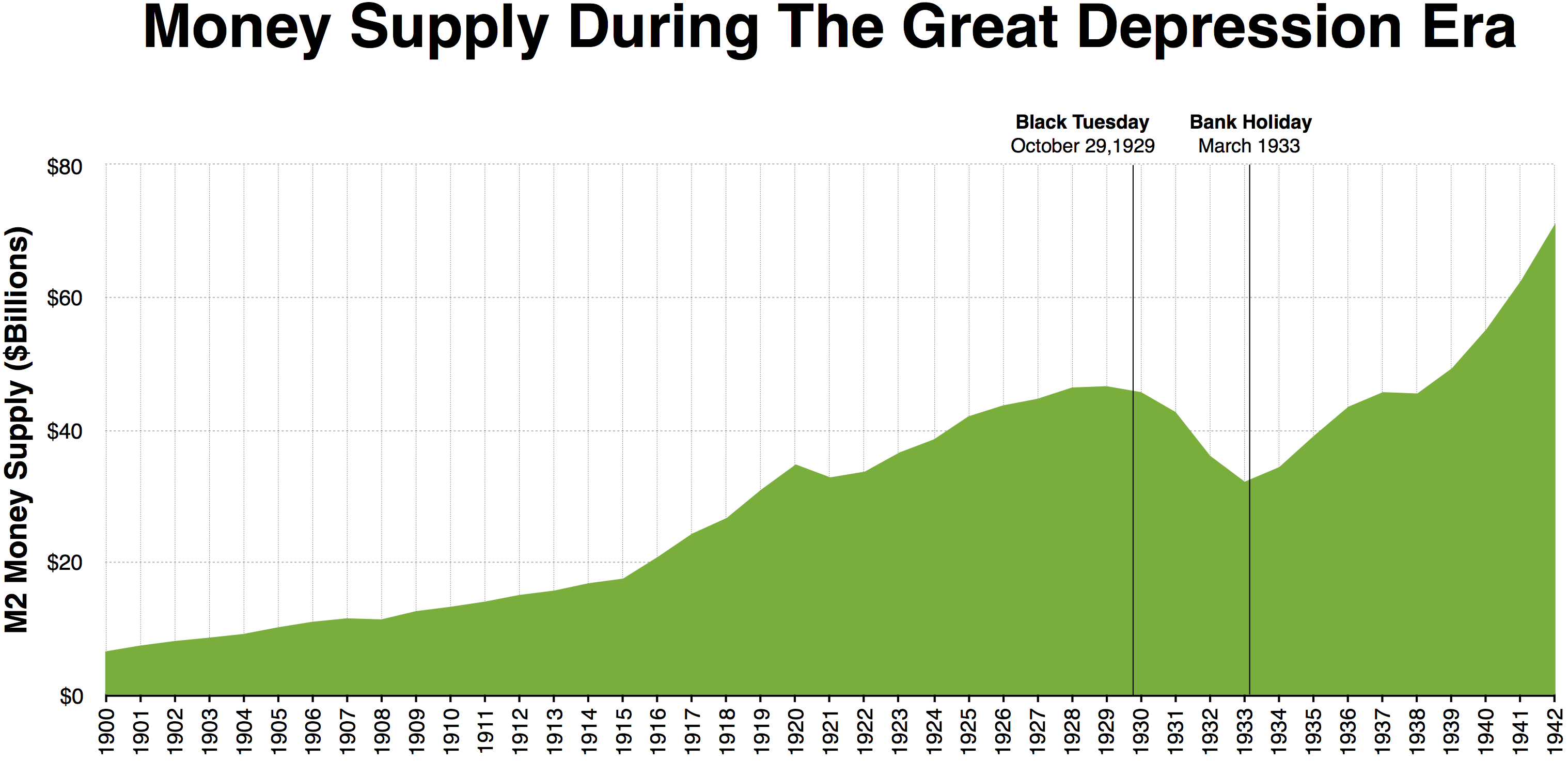

Federal Reserve Bank (February 20, 2004). This theory encountered criticism during the

Article in the New Palgrave on Money Supply

by

Do all banks hold reserves, and, if so, where do they hold them? (11/2001)

* ttp://research.stlouisfed.org/aggreg/ St. Louis Fed: Monetary Aggregates*

Discontinuance of M3 Publication

Investopedia: Money Zero Maturity (MZM)

* ttps://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/88 Historical H.3 releases

Money Stock Measures (H.6)

U.S. MZM magnitude

an

velocity

used as a predictor of

Data on Monetary Aggregates in Australia

Monetary Survey

from

In

In macroeconomics

Macroeconomics (from the Greek prefix ''makro-'' meaning "large" + ''economics'') is a branch of economics dealing with performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole.

For example, using interest rates, taxes, and ...

, the money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of currency held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include currency in circulation

In monetary economics, the currency in circulation in a country is the value of

currency or cash (banknotes and coins) that has ever been issued by the country’s monetary authority less the amount that has been removed. More broadly, money in ci ...

(i.e. physical cash) and demand deposits

Demand deposits or checkbook money are funds held in demand accounts in commercial banks. These account balances are usually considered money and form the greater part of the narrowly defined money supply of a country. Simply put, these are depo ...

(depositors' easily accessed asset

In financial accountancy, financial accounting, an asset is any resource owned or controlled by a business or an economic entity. It is anything (tangible or intangible) that can be used to produce positive economic value. Assets represent value ...

s on the books of financial institution

Financial institutions, sometimes called banking institutions, are business entities that provide services as intermediaries for different types of financial monetary transactions. Broadly speaking, there are three major types of financial inst ...

s). The central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the currency and monetary policy of a country or monetary union,

and oversees their commercial banking system. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central ba ...

of a country may use a definition of what constitutes legal tender

Legal tender is a form of money that courts of law are required to recognize as satisfactory payment for any monetary debt. Each jurisdiction determines what is legal tender, but essentially it is anything which when offered ("tendered") in pa ...

for its purposes.

Money supply data is recorded and published, usually by a government agency or the central bank of the country. Public

In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociological concept of the ''Öffentlichkei ...

and private sector

The private sector is the part of the economy, sometimes referred to as the citizen sector, which is owned by private groups, usually as a means of establishment for profit or non profit, rather than being owned by the government.

Employment

The ...

analysts monitor changes in the money supply because of the belief that such changes affect the price level

The general price level is a hypothetical measure of overall prices for some set of goods and services (the consumer basket), in an economy or monetary union during a given interval (generally one day), normalized relative to some base set. ...

s of securities

A security is a tradable financial asset. The term commonly refers to any form of financial instrument, but its legal definition varies by jurisdiction. In some countries and languages people commonly use the term "security" to refer to any for ...

, inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reductio ...

, the exchange rate

In finance, an exchange rate is the rate at which one currency will be exchanged for another currency. Currencies are most commonly national currencies, but may be sub-national as in the case of Hong Kong or supra-national as in the case of ...

s, and the business cycle

Business cycles are intervals of Economic expansion, expansion followed by recession in economic activity. These changes have implications for the welfare of the broad population as well as for private institutions. Typically business cycles are ...

.

The relationship between money and prices has historically been associated with the quantity theory of money

In monetary economics, the quantity theory of money (often abbreviated QTM) is one of the directions of Western economic thought that emerged in the 16th-17th centuries. The QTM states that the general price level of goods and services is directly ...

. There is some empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

evidence of a direct relationship between the growth of the money supply and long-term price inflation, at least for rapid increases in the amount of money in the economy. For example, a country such as Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozam ...

which saw extremely rapid increases in its money supply also saw extremely rapid increases in prices (hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimize their holdings in that currency as t ...

). This is one reason for the reliance on monetary policy

Monetary policy is the policy adopted by the monetary authority of a nation to control either the interest rate payable for very short-term borrowing (borrowing by banks from each other to meet their short-term needs) or the money supply, often a ...

as a means of controlling inflation.

Money creation by commercial banks

Commercial banks play a role in the process of money creation, under thefractional-reserve banking

Fractional-reserve banking is the system of banking operating in almost all countries worldwide, under which banks that take deposits from the public are required to hold a proportion of their deposit liabilities in liquid assets as a reserve, ...

system used throughout the world. In this system, credit

Credit (from Latin verb ''credit'', meaning "one believes") is the trust which allows one party to provide money or resources to another party wherein the second party does not reimburse the first party immediately (thereby generating a debt) ...

is created whenever a bank gives out a new loan and destroyed when the borrower pays back the principal on the loan.

This new money, in net terms, makes up the non-M0 component in the M1-M3 statistics. In short, there are two types of money in a fractional-reserve banking system:

* central bank money — obligations of a central bank, including currency

A currency, "in circulation", from la, currens, -entis, literally meaning "running" or "traversing" is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins.

A more general def ...

and central bank depository accounts

* commercial bank money — obligations of commercial banks, including checking accounts and savings accounts.

In the money supply statistics, central bank money is MB while the commercial bank money is divided up into the M1-M3 components. Generally, the types of commercial bank money that tend to be valued at lower amounts are classified in the narrow category of M1 while the types of commercial bank money that tend to exist in larger amounts are categorized in M2 and M3, with M3 having the largest.

In the United States, a bank's reserves consist of U.S. currency held by the bank (also known as "vault cash") plus the bank's balances in Federal Reserve accounts. For this purpose, cash on hand and balances in Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States of America. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a ...

("Fed") accounts are interchangeable (both are obligations of the Fed). Reserves may come from any source, including the federal funds market, deposits by the public, and borrowing from the Fed itself.

Open market operations by central banks

Central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the currency and monetary policy of a country or monetary union,

and oversees their commercial banking system. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central ba ...

s can influence the money supply by open market operations. They can increase the money supply by purchasing government securities, such as government bond

A government bond or sovereign bond is a form of bond issued by a government to support public spending. It generally includes a commitment to pay periodic interest, called coupon payments'','' and to repay the face value on the maturity date ...

s or treasury bill

United States Treasury securities, also called Treasuries or Treasurys, are government debt instruments issued by the United States Department of the Treasury to finance government spending as an alternative to taxation. Since 2012, U.S. gov ...

s. This increases the liquidity in the banking system by converting the illiquid securities of commercial banks into liquid deposits at the central bank. This also causes the price of such securities to rise due to the increased demand, and interest rates to fall. These funds become available to commercial banks for lending, and by the multiplier effect

In macroeconomics, a multiplier is a factor of proportionality that measures how much an endogenous variable changes in response to a change in some exogenous variable.

For example, suppose variable ''x''

changes by ''k'' units, which causes an ...

from fractional-reserve banking

Fractional-reserve banking is the system of banking operating in almost all countries worldwide, under which banks that take deposits from the public are required to hold a proportion of their deposit liabilities in liquid assets as a reserve, ...

, loans and bank deposits go up by many times the initial injection of funds into the banking system.

In contrast, when the central bank "tightens" the money supply, it sells securities on the open market, drawing liquid funds out of the banking system. The prices of such securities fall as supply is increased, and interest rates rise. This also has a multiplier effect.

This kind of activity reduces or increases the supply of short term government debt in the hands of banks and the non-bank public, also lowering or raising interest rates. In parallel, it increases or reduces the supply of loanable funds (money) and thereby the ability of private banks to issue new money through issuing debt.

The simple connection between monetary policy and monetary aggregates such as M1 and M2 changed in the 1970s as the reserve requirements on deposits started to fall with the emergence of money fund

A money market fund (also called a money market mutual fund) is an open-ended mutual fund that invests in short-term debt securities such as US Treasury bills and commercial paper. Money market funds are managed with the goal of maintaining a ...

s, which require no reserves. At present, reserve requirements apply only to " transactions deposits" – essentially checking accounts

A transaction account, also called a checking account, chequing account, current account, demand deposit account, or share draft account at credit unions, is a deposit account held at a bank or other financial institution. It is available to the ...

. The vast majority of funding sources used by private banks to create loans are not limited by bank reserves. Most commercial and industrial loans are financed by issuing large denomination CDs

The compact disc (CD) is a digital optical disc data storage format that was co-developed by Philips and Sony to store and play digital audio recordings. In August 1982, the first compact disc was manufactured. It was then released in Octo ...

. Money market

The money market is a component of the economy that provides short-term funds. The money market deals in short-term loans, generally for a period of a year or less.

As short-term securities became a commodity, the money market became a compon ...

deposits are largely used to lend to corporations who issue commercial paper

Commercial paper, in the global financial market, is an unsecured promissory note with a fixed maturity of rarely more than 270 days. In layperson terms, it is like an " IOU" but can be bought and sold because its buyers and sellers have some ...

. Consumer loans are also made using savings deposits

A savings account is a bank account at a retail bank. Common features include a limited number of withdrawals, a lack of cheque and linked debit card facilities, limited transfer options and the inability to be overdrawn. Traditionally, transac ...

, which are not subject to reserve requirements. This means that instead of the value of loans supplied responding passively to monetary policy, we often see it rising and falling with the demand for funds and the willingness of banks to lend.

Some economists argue that the money multiplier is a meaningless concept, because its relevance would require that the money supply be exogenous

In a variety of contexts, exogeny or exogeneity () is the fact of an action or object originating externally. It contrasts with endogeneity or endogeny, the fact of being influenced within a system.

Economics

In an economic model, an exogeno ...

, i.e. determined by the monetary authorities via open market operations. If central banks usually target the shortest-term interest rate (as their policy instrument) then this leads to the money supply being endogenous

Endogenous substances and processes are those that originate from within a living system such as an organism, tissue, or cell.

In contrast, exogenous substances and processes are those that originate from outside of an organism.

For example, es ...

.

Neither commercial nor consumer loans are any longer limited by bank reserves. Nor are they directly linked proportional to reserves. Between 1995 and 2008, the value of consumer loans has steadily increased out of proportion to bank reserves. Then, as part of the financial crisis, bank reserves rose dramatically as new loans shrank.

In recent years, some academic economists renowned for their work on the implications of

In recent years, some academic economists renowned for their work on the implications of rational expectations

In economics, "rational expectations" are model-consistent expectations, in that agents inside the model

A model is an informative representation of an object, person or system. The term originally denoted the plans of a building in late 16 ...

have argued that open market operations are irrelevant. These include Robert Lucas Jr., Thomas Sargent

Thomas John Sargent (born July 19, 1943) is an American economist and the W.R. Berkley Professor of Economics and Business at New York University. He specializes in the fields of macroeconomics, monetary economics, and time series econometric ...

, Neil Wallace

Neil Wallace (born 1939) is an American economist and professor of economics at Penn State University. He is considered one of the main proponents of new classical macroeconomics in the field of economics.

Education

Wallace earned his BA in e ...

, Finn E. Kydland

Finn Erling Kydland (born 1 December 1943) is a Norwegian economist known for his contributions to business cycle theory. He is the Henley Professor of Economics at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He also holds the Richard P. Simmons ...

, Edward C. Prescott

Edward Christian Prescott (December 26, 1940 – November 6, 2022) was an American economist. He received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics in 2004, sharing the award with Finn E. Kydland, "for their contributions to dynamic macroeconomics: ...

and Scott Freeman. Keynesian

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output an ...

economists point to the ineffectiveness of open market operations in 2008 in the United States, when short-term interest rates went as low as they could go in nominal terms, so that no more monetary stimulus could occur. This zero bound problem has been called the liquidity trap

A liquidity trap is a situation, described in Keynesian economics, in which, "after the rate of interest has fallen to a certain level, liquidity preference may become virtually absolute in the sense that almost everyone prefers holding cash rathe ...

or "pushing on a string

Pushing on a string is a figure of speech for influence that is more effective in moving things in one direction than another – you can ''pull,'' but not ''push.''

If something is connected to someone by a string, they can move it toward themse ...

" (the pusher being the central bank and the string being the real economy).

Empirical measures in the United States Federal Reserve System

:''See also

:''See also European Central Bank

The European Central Bank (ECB) is the prime component of the monetary Eurosystem and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) as well as one of seven institutions of the European Union. It is one of the world's Big Four (banking)#Intern ...

for other approaches and a more global perspective.''

Money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are as ...

is used as a medium of exchange

In economics, a medium of exchange is any item that is widely acceptable in exchange for goods and services. In modern economies, the most commonly used medium of exchange is currency.

The origin of "mediums of exchange" in human societies is ass ...

, as a unit of account

In economics, unit of account is one of the money functions. A unit of account is a standard numerical monetary unit of measurement of the market value of goods, services, and other transactions. Also known as a "measure" or "standard" of rela ...

, and as a ready store of value

A store of value is any commodity or asset that would normally retain purchasing power into the future and is the function of the asset that can be saved, retrieved and exchanged at a later time, and be predictably useful when retrieved.

The most ...

. These different functions are associated with different empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

measures of the money supply. There is no single "correct" measure of the money supply. Instead, there are several measures, classified along a spectrum or continuum between narrow and broad ''monetary aggregates''. Narrow measures include only the most liquid assets: those most easily used to spend (currency, checkable deposits). Broader measures add less liquid types of assets (certificates of deposit, etc.).

This continuum corresponds to the way that different types of money are more or less controlled by monetary policy. Narrow measures include those more directly affected and controlled by monetary policy, whereas broader measures are less closely related to monetary-policy actions. It is a matter of perennial debate as to whether narrower or broader versions of the money supply have a more predictable link to nominal GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a money, monetary Measurement in economics, measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjec ...

.

The different types of money are typically classified as "M"s. The "M"s usually range from M0 (narrowest) to M3 (broadest) but which "M"s are actually focused on in policy formulation depends on the country's central bank. The typical layout for each of the "M"s is as follows:

* : In some countries, such as the United Kingdom, M0 includes bank reserves, so M0 is referred to as the monetary base, or narrow money.

* MB: is referred to as the monetary base

In economics, the monetary base (also base money, money base, high-powered money, reserve money, outside money, central bank money or, in the UK, narrow money) in a country is the total amount of money created by the central bank. This include ...

or total currency. This is the base from which other forms of money (like checking deposits, listed below) are created and is traditionally the most liquid measure of the money supply.

* M1: Bank reserves are not included in M1.

* M2: Represents M1 and "close substitutes" for M1. M2 is a broader classification of money than M1. M2 is a key economic indicator used to forecast inflation.

* M3: M2 plus large and long-term deposits. Since 2006, M3 is no longer published by the US central bank.Discontinuance of M3Federal Reserve, November 10, 2005, revised March 9, 2006. However, there are still estimates produced by various private institutions. * MZM: Money with zero maturity. It measures the supply of financial assets redeemable at par on demand.

Velocity

Velocity is the directional speed of an object in motion as an indication of its rate of change in position as observed from a particular frame of reference and as measured by a particular standard of time (e.g. northbound). Velocity is a ...

of MZM is historically a relatively accurate predictor of inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reductio ...

.

The ratio of a pair of these measures, most often M2 / M0, is called the money multiplier.

Definitions of "money"

East Asia

Hong Kong SAR, China

Hong Kong dollar

The Hong Kong dollar (, currency symbol, sign: HK$; ISO 4217, code: HKD) is the official currency of the Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. It is subdivided into 100 cent (currency), cents or 1000 Mill (currency), mils. The H ...

's peg to the pound was increased from 1 shilling 3 pence (£1 = HK$16) to 1 shilling 4½ pence (£1 = HK$14.5455) although this did not entirely offset the devaluation of sterling relative to the US dollar (it went from US$1 = HK$5.71 to US$1 = HK$6.06). In 1972 the Hong Kong dollar was pegged to the US dollar at a rate of US$1 = HK$5.65. This was reduced to HK$5.085 in 1973. Between 1974 and 1983 the Hong Kong dollar floated. On October 17, 1983, the currency was pegged at a rate of US$1 = HK$7.80 through the currency board system.

As of May 18, 2005, in addition to the lower guaranteed limit, a new upper guaranteed limit was set for the ong Kong dollar at 7.75 to the American dollar. The lower limit was lowered from 7.80 to 7.85 (by 100 pips per week from May 23 to June 20, 2005). The Hong Kong Monetary Authority indicated that this move was to narrow the gap between the interest rates in Hong Kong and those of the United States. A further aim of allowing the Hong Kong dollar to trade in a range is to avoid the HK dollar being used as a proxy for speculative bets on a renminbi revaluation.

The Hong Kong Basic Law and the Sino-British Joint Declaration provides that Hong Kong retains full autonomy with respect to currency issuance. Currency in Hong Kong is issued by the government and three local banks under the supervision of the territory's ''de facto'' central bank, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority. Bank notes are printed by Hong Kong Note Printing

Hong Kong Note Printing Limited is a company which prints the bank notes of all the three note-issuing banks in Hong Kong. The banknote printing plant was founded in 1984 by Thomas De La Rue in Tai Po Industrial Estate. In April 1996, the Hong Ko ...

.

A bank can issue a Hong Kong dollar only if it has the equivalent exchange in US dollars on deposit. The currency board system ensures that Hong Kong's entire monetary base is backed with US dollars at the linked exchange rate. The resources for the backing are kept in Hong Kong's exchange fund, which is among the largest official reserves in the world. Hong Kong also has huge deposits of US dollars, with official foreign currency reserves of 331.3 billion USD .

Japan

The Bank of Japan defines the monetary aggregates as:

* M1: cash currency in circulation, plus deposit money

* M2 + CDs: M1 plus

The Bank of Japan defines the monetary aggregates as:

* M1: cash currency in circulation, plus deposit money

* M2 + CDs: M1 plus quasi-money

Near money or quasi-money consists of highly liquid assets which are not cash but can easily be converted into cash.

Examples of near money include:

* Savings accounts

* Money market funds

* Bank time deposits (certificates of deposit)

* Gov ...

and CDs

The compact disc (CD) is a digital optical disc data storage format that was co-developed by Philips and Sony to store and play digital audio recordings. In August 1982, the first compact disc was manufactured. It was then released in Octo ...

* M3 + CDs: M2 + CDs plus deposits of post offices; other savings and deposits with financial institutions; and money trusts

* Broadly defined liquidity: M3 and CDs, plus money market, pecuniary trusts other than money trusts, investment trusts, bank debentures, commercial paper issued by financial institutions, repurchase agreements and securities lending

In finance, securities lending or stock lending refers to the lending of securities by one party to another.

The terms of the loan will be governed by a "Securities Lending Agreement", which requires that the borrower provides the lender with c ...

with cash collateral, government bonds and foreign bonds

Europe

United Kingdom

monetary base

In economics, the monetary base (also base money, money base, high-powered money, reserve money, outside money, central bank money or, in the UK, narrow money) in a country is the total amount of money created by the central bank. This include ...

" or "narrow money" and M4 is referred to as " broad money" or simply "the money supply".

* M0: Notes and coin in circulation plus banks' reserve balance with Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government of ...

. (When the bank introduced Money Market Reform in May 2006, the bank ceased publication of M0 and instead began publishing series for reserve balances at the Bank of England to accompany notes and coin in circulation.)

* M4: Cash outside banks (i.e. in circulation with the public and non-bank firms) plus private-sector retail bank and building society deposits plus private-sector wholesale bank and building society deposits and certificates of deposit. In 2010 the total money supply (M4) measure in the UK was £2.2 trillion while the actual notes and coins in circulation totalled only £47 billion, 2.1% of the actual money supply.

There are several different definitions of money supply to reflect the differing stores of money. Owing to the nature of bank deposits, especially time-restricted savings account deposits, M4 represents the most illiquid

In business, economics or investment, market liquidity is a market's feature whereby an individual or firm can quickly purchase or sell an asset without causing a drastic change in the asset's price. Liquidity involves the trade-off between th ...

measure of money. M0, by contrast, is the most liquid measure of the money supply.

Eurozone

The

The European Central Bank

The European Central Bank (ECB) is the prime component of the monetary Eurosystem and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) as well as one of seven institutions of the European Union. It is one of the world's Big Four (banking)#Intern ...

's definition of euro area monetary aggregates:

* M1: Currency in circulation plus overnight deposits

* M2: M1 plus deposits with an agreed maturity up to two years plus deposits redeemable at a period of notice up to three months.

* M3: M2 plus repurchase agreements plus money market fund (MMF) shares/units, plus debt securities up to two years

North America

United States

The United States

The United States Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States of America. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a ...

published data on three monetary aggregates until 2006, when it ceased publication of M3 data and only published data on M1 and M2. M1 consists of money commonly used for payment, basically currency in circulation

In monetary economics, the currency in circulation in a country is the value of

currency or cash (banknotes and coins) that has ever been issued by the country’s monetary authority less the amount that has been removed. More broadly, money in ci ...

and checking account

A transaction account, also called a checking account, chequing account, current account, demand deposit account, or share draft account at credit unions, is a deposit account held at a bank or other financial institution. It is available to the ...

balances; and M2 includes M1 plus balances that generally are similar to transaction accounts and that, for the most part, can be converted fairly readily to M1 with little or no loss of principal. The M2 measure is thought to be held primarily by households. Prior to its discontinuation, M3 comprised M2 plus certain accounts that are held by entities other than individuals and are issued by banks and thrift institutions to augment M2-type balances in meeting credit demands, as well as balances in money market mutual funds held by institutional investors. The aggregates have had different roles in monetary policy as their reliability as guides has changed. The principal components are:

* M0: The total of all physical currency including coinage. M0 = Federal Reserve Note

Federal Reserve Notes, also United States banknotes, are the currently issued banknotes of the United States dollar. The United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing produces the notes under the authority of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 ...

s + US Notes + Coins

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order to ...

. It is not relevant whether the currency is held inside or outside of the private banking system as reserves.

* MB: The total of all physical currency plus Federal Reserve Deposits (special deposits that only banks can have at the Fed). MB = Coins

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order to ...

+ US Notes + Federal Reserve Note

Federal Reserve Notes, also United States banknotes, are the currently issued banknotes of the United States dollar. The United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing produces the notes under the authority of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 ...

s + Federal Reserve Deposits

* M1: The total amount of M0 (cash/coin) outside of the private banking system plus the amount of demand deposit

Demand deposits or checkbook money are funds held in demand accounts in commercial banks. These account balances are usually considered money and form the greater part of the narrowly defined money supply of a country. Simply put, these are depo ...

s, travelers checks and other checkable deposits + most savings account

A savings account is a bank account at a retail bank. Common features include a limited number of withdrawals, a lack of cheque and linked debit card facilities, limited transfer options and the inability to be overdrawn. Traditionally, transa ...

s.

* M2: M1 + money market accounts, retail money market mutual funds, and small denomination time deposits (certificates of deposit

A certificate of deposit (CD) is a time deposit, a financial product commonly sold by banks, thrift institutions, and credit unions in the United States. CDs differ from savings accounts in that the CD has a specific, fixed term (often one, t ...

of under $100,000).

* MZM: 'Money Zero Maturity' is one of the most popular aggregates in use by the Fed because its velocity

Velocity is the directional speed of an object in motion as an indication of its rate of change in position as observed from a particular frame of reference and as measured by a particular standard of time (e.g. northbound). Velocity is a ...

has historically been the most accurate predictor of inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reductio ...

. It is M2 – time deposits + money market funds

* M3: M2 + all other CDs

The compact disc (CD) is a digital optical disc data storage format that was co-developed by Philips and Sony to store and play digital audio recordings. In August 1982, the first compact disc was manufactured. It was then released in Octo ...

(large time deposits, institutional money market mutual fund balances), deposits of eurodollar

Eurodollars are U.S. dollars held in time deposit accounts in banks outside the United States, which thus are not subject to the legal jurisdiction of the U.S. Federal Reserve. Consequently, such deposits are subject to much less regulation than ...

s and repurchase agreement

A repurchase agreement, also known as a repo, RP, or sale and repurchase agreement, is a form of short-term borrowing, mainly in government securities. The dealer sells the underlying security to investors and, by agreement between the two par ...

s.

* M4-: M3 + Commercial Paper

Commercial paper, in the global financial market, is an unsecured promissory note with a fixed maturity of rarely more than 270 days. In layperson terms, it is like an " IOU" but can be bought and sold because its buyers and sellers have some ...

* M4: M4- + T-Bills

United States Treasury securities, also called Treasuries or Treasurys, are government debt instruments issued by the United States Department of the Treasury to finance government spending as an alternative to taxation. Since 2012, U.S. gov ...

(or M3 + Commercial Paper + T-Bills

United States Treasury securities, also called Treasuries or Treasurys, are government debt instruments issued by the United States Department of the Treasury to finance government spending as an alternative to taxation. Since 2012, U.S. gov ...

)

* L: The broadest measure of liquidity, that the Federal Reserve no longer tracks. L is very close to M4 + Bankers' Acceptance

A banker's acceptance is a commitment by a bank to make a requested future payment. The request will typically specify the payee, the amount, and the date on which it is eligible for payment. After acceptance, the request becomes an unconditional ...

* Money Multiplier: M1 / MB. As of December 3, 2015, it was 0.756. While a multiplier under one is historically an oddity, this is a reflection of the popularity of M2 over M1 and the massive amount of MB the government has created since 2008.

Prior to 2020, savings accounts were counted as M2 and not part of M1 as they were not considered "transaction accounts" by the Fed. (There was a limit of six transactions per cycle that could be carried out in a savings account without incurring a penalty.) On March 15, 2020, the Federal Reserve eliminated reserve requirements for all depository institutions and rendered the regulatory distinction between reservable "transaction accounts" and nonreservable "savings deposits" unnecessary. On April 24, 2020, the Board removed this regulatory distinction by deleting the six-per-month transfer limit on savings deposits. From this point on, savings account deposits were included in M1.

Although the Treasury can and does hold cash and a special deposit account at the Fed (TGA account), these assets do not count in any of the aggregates. So in essence, money paid in taxes paid to the Federal Government (Treasury) is excluded from the money supply. To counter this, the government created the Treasury Tax and Loan (TT&L) program in which any receipts above a certain threshold are redeposited in private banks. The idea is that tax receipts won't decrease the amount of reserves in the banking system. The TT&L accounts, while demand deposits, do not count toward M1 or any other aggregate either.

When the Federal Reserve announced in 2005 that they would cease publishing M3 statistics in March 2006, they explained that M3 did not convey any additional information about economic activity compared to M2, and thus, "has not played a role in the monetary policy process for many years." Therefore, the costs to collect M3 data outweighed the benefits the data provided. Some politicians have spoken out against the Federal Reserve's decision to cease publishing M3 statistics and have urged the U.S. Congress to take steps requiring the Federal Reserve to do so. Congressman Ron Paul (R-TX) claimed that "M3 is the best description of how quickly the Fed is creating new money and credit. Common sense tells us that a government central bank creating new money out of thin air depreciates the value of each dollar in circulation." Modern Monetary Theory

Modern Monetary Theory or Modern Money Theory (MMT) is a heterodox

*

*

*

*

*

* macroeconomic theory that describes currency as a public monopoly and unemployment as evidence that a currency monopolist is overly restricting the supply of t ...

disagrees. It holds that money creation in a free-floating fiat currency regime such as the U.S. will not lead to significant inflation unless the economy is approaching full employment and full capacity. Some of the data used to calculate M3 are still collected and published on a regular basis. Current alternate sources of M3 data are available from the private sector.

As of April 2013, the monetary base

In economics, the monetary base (also base money, money base, high-powered money, reserve money, outside money, central bank money or, in the UK, narrow money) in a country is the total amount of money created by the central bank. This include ...

was $3 trillion and M2, the broadest measure of money supply, was $10.5 trillion.

Oceania

Australia

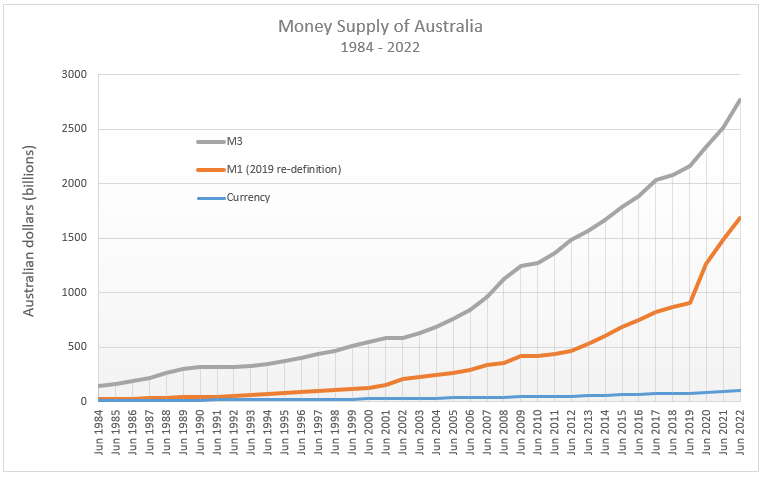

Reserve Bank of Australia

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) is Australia's central bank and banknote issuing authority. It has had this role since 14 January 1960, when the ''Reserve Bank Act 1959'' removed the central banking functions from the Commonwealth Bank.

Th ...

defines the monetary aggregates as:

* M1: currency in circulation

In monetary economics, the currency in circulation in a country is the value of

currency or cash (banknotes and coins) that has ever been issued by the country’s monetary authority less the amount that has been removed. More broadly, money in ci ...

plus bank current deposits from the private non-bank sector

* M3: M1 plus all other bank deposits from the private non-bank sector, plus bank certificate of deposits, less inter-bank deposits

* Broad money: M3 plus borrowings from the private sector by NBFIs, less the latter's holdings of currency and bank deposits

* Money base: holdings of notes and coins by the private sector plus deposits of banks with the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and other RBA liabilities to the private non-bank sector.

New Zealand

The

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ, mi, Te Pūtea Matua) is the central bank of New Zealand. It was established in 1934 and is constituted under the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act 1989. The governor of the Reserve Bank is responsible for N ...

defines the monetary aggregates as:

* M1: notes and coins held by the public plus chequeable deposits, minus inter-institutional chequeable deposits, and minus central government deposits

* M2: M1 + all non-M1 call funding (call funding includes overnight money and funding on terms that can of right be broken without break penalties) minus inter-institutional non-M1 call funding

* M3: the broadest monetary aggregate. It represents all New Zealand dollar funding of M3 institutions and any Reserve Bank repos with non-M3 institutions. M3 consists of notes & coin held by the public plus NZ dollar funding minus inter-M3 institutional claims and minus central government deposits

South Asia

India

The

The Reserve Bank of India

The Reserve Bank of India, chiefly known as RBI, is India's central bank and regulatory body responsible for regulation of the Indian banking system. It is under the ownership of Ministry of Finance, Government of India. It is responsible for ...

defines the monetary aggregates as:

* Reserve money (M0): Currency in circulation, plus bankers' deposits with the RBI and 'other' deposits with the RBI. Calculated from net RBI credit to the government plus RBI credit to the commercial sector, plus RBI's claims on banks and net foreign assets plus the government's currency liabilities to the public, less the RBI's net non-monetary liabilities. M0 outstanding was 30.297 trillion as on March 31, 2020.

* M1: Currency with the public plus deposit money of the public (demand deposits with the banking system and 'other' deposits with the RBI). M1 was 184 per cent of M0 in August 2017.

* M2: M1 plus savings deposits with post office savings banks. M2 was 879 per cent of M0 in August 2017.

* M3 (the broad concept of money supply): M1 plus time deposits with the banking system, made up of net bank credit to the government plus bank credit to the commercial sector, plus the net foreign exchange assets of the banking sector and the government's currency liabilities to the public, less the net non-monetary liabilities of the banking sector (other than time deposits). M3 was 555 per cent of M0 as on March 31, 2020(i.e. 167.99 trillion.)

* M4: M3 plus all deposits with post office savings banks (excluding National Savings Certificates).

Link with inflation

Monetary exchange equation

The money supply is important because it is linked to inflation by theequation of exchange In monetary economics, the equation of exchange is the relation:

:M\cdot V = P\cdot Q

where, for a given period,

:M\, is the total money supply in circulation on average in an economy.

:V\, is the velocity of money, that is the average frequency w ...

in an equation proposed by Irving Fisher

Irving Fisher (February 27, 1867 – April 29, 1947) was an American economist, statistician, inventor, eugenicist and progressive social campaigner. He was one of the earliest American neoclassical economists, though his later work on debt def ...

in 1911:

:

where

* is the total dollars in the nation's money supply,

* is the number of times per year each dollar is spent (velocity of money

image:M3 Velocity in the US.png, 300px, Similar chart showing the logged velocity (green) of a broader measure of money M3 that covers M2 plus large institutional deposits. The US no longer publishes official M3 measures, so the chart only runs thr ...

),

* is the average price of all the goods and services sold during the year,

* is the quantity of assets, goods and services sold during the year.

In mathematical terms, this equation is an identity

Identity may refer to:

* Identity document

* Identity (philosophy)

* Identity (social science)

* Identity (mathematics)

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Identity'' (1987 film), an Iranian film

* ''Identity'' (2003 film), ...

which is true by definition rather than describing economic behavior. That is, velocity is defined by the values of the other three variables. Unlike the other terms, the velocity of money has no independent measure and can only be estimated by dividing by . Some adherents of the quantity theory of money assume that the velocity of money is stable and predictable, being determined mostly by financial institutions. If that assumption is valid then changes in can be used to predict changes in . If not, then a model of is required in order for the equation of exchange to be useful as a macroeconomics model or as a predictor of prices.

Most macroeconomists replace the equation of exchange with equations for the demand for money

In monetary economics, the demand for money is the desired holding of financial assets in the form of money: that is, cash or bank deposits rather than investments. It can refer to the demand for money narrowly defined as M1 (directly spendable ...

which describe more regular and predictable economic behavior. However, predictability (or the lack thereof) of the velocity of money is equivalent to predictability (or the lack thereof) of the demand for money (since in equilibrium real money demand is simply ). Either way, this unpredictability made policy-makers at the Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States of America. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a ...

rely less on the money supply in steering the U.S. economy. Instead, the policy focus has shifted to interest rate

An interest rate is the amount of interest due per period, as a proportion of the amount lent, deposited, or borrowed (called the principal sum). The total interest on an amount lent or borrowed depends on the principal sum, the interest rate, th ...

s such as the fed funds rate

In the United States, the federal funds rate is the interest rate at which depository institutions (banks and credit unions) lend reserve balances to other depository institutions overnight on an uncollateralized basis. Reserve balances ...

.

In practice, macroeconomists almost always use real GDP to define , omitting the role of all transactions except for those involving newly produced goods and services (i.e., consumption goods, investment goods, government-purchased goods, and exports). But the original quantity theory of money did not follow this practice: was the monetary value of all new transactions, whether of real goods and services or of paper assets.

GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjective nature this measure is ofte ...

back in the 1960s. This is not the case anymore because of the dramatic rise of the number of financial transactions relative to that of real transactions up until 2008. That is, the total value of transactions (including purchases of paper assets) rose relative to nominal GDP (which excludes those purchases).

Ignoring the effects of monetary growth on real purchases and velocity, this suggests that the growth of the money supply may cause different kinds of inflation at different times. For example, rises in the U.S. money supplies between the 1970s and the present encouraged first a rise in the inflation rate for newly-produced goods and services ("inflation" as usually defined) in the 1970s and then asset-price inflation in later decades: it may have encouraged a stock market boom in the 1980s and 1990s and then, after 2001, a rise in home prices, i.e., the famous housing bubble

A housing bubble (or a housing price bubble) is one of several types of asset price bubbles which periodically occur in the market. The basic concept of a housing bubble is the same as for other asset bubbles, consisting of two main phases. Firs ...

. This story, of course, assumes that the amounts of money were the causes of these different types of inflation rather than being endogenous results of the economy's dynamics.

When home prices went down, the Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States of America. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a ...

kept its loose monetary policy and lowered interest rates; the attempt to slow price declines in one asset class, e.g. real estate, may well have caused prices in other asset classes to rise, e.g. commodities.

Rates of growth

In terms of percentage changes (to a close approximation, under low growth rates), the percentage change in a product, say , is equal to the sum of the percentage changes ). So, denoting all percentage changes as per unit of time, : This equation rearranged gives the basic inflation identity: : Inflation (%ΔP) is equal to the rate of money growth (%Δ), plus the change in velocity (%Δ), minus the rate of output growth (%Δ). So if in the long run the growth rate of velocity and the growth rate of real GDP areexogenous

In a variety of contexts, exogeny or exogeneity () is the fact of an action or object originating externally. It contrasts with endogeneity or endogeny, the fact of being influenced within a system.

Economics

In an economic model, an exogeno ...

constants (the former being dictated by changes in payment institutions and the latter dictated by the growth in the economy’s productive capacity), then the monetary growth rate and the inflation rate differ from each other by a fixed constant.

As before, this equation is only useful if %Δ follows regular behavior. It also loses usefulness if the central bank lacks control over %Δ.

Arguments

Historically, in Europe, the main function of thecentral bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the currency and monetary policy of a country or monetary union,

and oversees their commercial banking system. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central ba ...

is to maintain low inflation. In the USA the focus is on both inflation and unemployment. These goals are sometimes in conflict (according to the Phillips curve

The Phillips curve is an economic model, named after William Phillips hypothesizing a correlation between reduction in unemployment and increased rates of wage rises within an economy. While Phillips himself did not state a linked relationship ...

). A central bank may attempt to do this by artificially influencing the demand for goods by increasing or decreasing the nation's money supply (relative to trend), which lowers or raises interest rates, which stimulates or restrains spending on goods and services.

An important debate among economists in the second half of the 20th century concerned the central bank's ability to predict how much money should be in circulation, given current employment rates and inflation rates. Economists such as Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

believed that the central bank would always get it wrong, leading to wider swings in the economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the ...

than if it were just left alone. This is why they advocated a non-interventionist approach: one of targeting a pre-specified path for the money supply independent of current economic conditions, even though in practice this might involve regular intervention with open market operations

In macroeconomics, an open market operation (OMO) is an activity by a central bank to give (or take) liquidity in its currency to (or from) a bank or a group of banks. The central bank can either buy or sell government bonds (or other financial as ...

(or other monetary-policy tools) to keep the money supply on target.

The former Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke

Ben Shalom Bernanke ( ; born December 13, 1953) is an American economist who served as the 14th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 2006 to 2014. After leaving the Fed, he was appointed a distinguished fellow at the Brookings Institution. Durin ...

, suggested in 2004 that over the preceding 10 to 15 years, many modern central banks became relatively adept at manipulation of the money supply, leading to a smoother business cycle, with recessions tending to be smaller and less frequent than in earlier decades, a phenomenon termed "The Great Moderation

The Great Moderation is a period in the United States of America starting from the mid-1980s until at least 2007 characterized by the reduction in the volatility of business cycle fluctuations in developed nations compared with the decades befor ...

"Federal Reserve Bank (February 20, 2004). This theory encountered criticism during the

global financial crisis of 2008–2009

Global means of or referring to a globe and may also refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Global'' (Paul van Dyk album), 2003

* ''Global'' (Bunji Garlin album), 2007

* ''Global'' (Humanoid album), 1989

* ''Global'' (Todd Rundgren album), 2015

* Bruno ...

. Furthermore, it may be that the functions of the central bank need to encompass more than the shifting up or down of interest rates or bank reserves: these tools, although valuable, may not in fact moderate the volatility of money supply (or its velocity).

Impact of digital currencies and possible transition to a cashless society

See also

* ''A Program for Monetary Reform

The Chicago plan was a monetary and banking reform program suggested in the wake of the Great Depression by a group of University of Chicago economists including Henry Simons, Garfield Cox, Aaron Director, Paul Douglas, Albert G. Hart, Frank ...

''

* American Monetary Institute

{{Notability, date=April 2022

The American Monetary Institute is a non-profit charitable trust established by Stephen Zarlenga in 1996 for the "independent study of monetary history, theory and reform."

Aims

The institute is dedicated to moneta ...

* Bank regulation

Bank regulation is a form of government regulation which subjects banks to certain requirements, restrictions and guidelines, designed to create market transparency between banking institutions and the individuals and corporations with whom they ...

* Capital requirement

A capital requirement (also known as regulatory capital, capital adequacy or capital base) is the amount of capital a bank or other financial institution has to have as required by its financial regulator. This is usually expressed as a capital ad ...

* Central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the currency and monetary policy of a country or monetary union,

and oversees their commercial banking system. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central ba ...

* Chartalism

In macroeconomics, chartalism is a heterodox theory of money that argues that money originated historically with states' attempts to direct economic activity rather than as a spontaneous solution to the problems with barter or as a means with whi ...

* Chicago plan

The Chicago plan was a monetary and banking reform program suggested in the wake of the Great Depression by a group of University of Chicago economists including Henry Simons, Garfield Cox, Aaron Director, Paul Douglas, Albert G. Hart, Fra ...

* The Chicago Plan Revisited

The Chicago plan was a monetary and banking reform program suggested in the wake of the Great Depression by a group of University of Chicago economists including Henry Simons, Garfield Cox, Aaron Director, Paul Douglas, Albert G. Hart, Frank ...

* Committee on Monetary and Economic Reform The Committee on Monetary and Economic Reform (COMER) is an economics-oriented publishing and education centre based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Organization

COMER was co-founded by William Krehm and John Hotson in the 1980s as a think tank out ...

* Core inflation

Core inflation represents the long run trend in the price level. In measuring long run inflation, transitory price changes should be excluded. One way of accomplishing this is by excluding items frequently subject to volatile prices, like foo ...

* Debt levels and flows

* Economics terminology that differs from common usage

In any technical subject, words commonly used in everyday life acquire very specific technical meanings, and confusion can arise when someone is uncertain of the intended meaning of a word. This article explains the differences in meaning between ...

* Fiat currency

* Financial capital

Financial capital (also simply known as capital or equity in finance, accounting and economics) is any economic resource measured in terms of money used by entrepreneurs and businesses to buy what they need to make their products or to provide ...

* Float

Float may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music Albums

* ''Float'' (Aesop Rock album), 2000

* ''Float'' (Flogging Molly album), 2008

* ''Float'' (Styles P album), 2013

Songs

* "Float" (Tim and the Glory Boys song), 2022

* "Float", by Bush ...

* Fractional-reserve banking

Fractional-reserve banking is the system of banking operating in almost all countries worldwide, under which banks that take deposits from the public are required to hold a proportion of their deposit liabilities in liquid assets as a reserve, ...

* FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data)

Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) is a database maintained by the Research division of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis that has more than 816,000 economic time series from various sources. They cover banking, business/fiscal, consumer p ...

* Full reserve banking

Full-reserve banking (also known as 100% reserve banking, narrow banking, or sovereign money system) is a system of banking where banks do not lend demand deposits and instead, only lend from time deposits. It differs from fractional-reserve ban ...

* Great Contraction

The Great Contraction is the recessionary period from 1929 until 1933, i.e., the early years of the Great Depression, as characterized by economist Milton Friedman. The phrase was the title of a chapter in the landmark 1963 book '' A Monetary Hist ...

* Index of Leading Indicators

The Conference Board Leading Economic Index is an American economic leading indicator intended to forecast future economic activity. It is calculated by The Conference Board, a non-governmental organization, which determines the value of the index ...

– money supply is a component

* Inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reductio ...

* Monetarism

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. Monetarist theory asserts that variations in the money supply have major influences on nation ...

* Monetary base

In economics, the monetary base (also base money, money base, high-powered money, reserve money, outside money, central bank money or, in the UK, narrow money) in a country is the total amount of money created by the central bank. This include ...

* Monetary economics

Monetary economics is the branch of economics that studies the different competing theories of money: it provides a framework for analyzing money and considers its functions (such as medium of exchange, store of value and unit of account), and it ...

* Monetary reform

Monetary reform is any movement or theory that proposes a system of supplying money and financing the economy that is different from the current system.

Monetary reformers may advocate any of the following, among other proposals:

* A return t ...

* Money circulation

In monetary economics, the currency in circulation in a country is the value of

currency or cash (banknotes and coins) that has ever been issued by the country’s monetary authority less the amount that has been removed. More broadly, money in ci ...

* Money creation

* Money market

The money market is a component of the economy that provides short-term funds. The money market deals in short-term loans, generally for a period of a year or less.

As short-term securities became a commodity, the money market became a compon ...

* Money demand

In monetary economics, the demand for money is the desired holding of financial assets in the form of money: that is, cash or bank deposits rather than investments. It can refer to the demand for money narrowly defined as M1 (directly spendable ...

* Liquidity preference

__NOTOC__

In macroeconomic theory, liquidity preference is the demand for money, considered as liquidity. The concept was first developed by John Maynard Keynes in his book '' The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money'' (1936) to e ...

* Seigniorage

Seigniorage , also spelled seignorage or seigneurage (from the Old French ''seigneuriage'', "right of the lord (''seigneur'') to mint money"), is the difference between the value of money and the cost to produce and distribute it. The term can be ...

* Stagflation

In economics, stagflation or recession-inflation is a situation in which the inflation rate is high or increasing, the economic growth rate slows, and unemployment remains steadily high. It presents a dilemma for economic policy, since action ...

References

Further reading

Article in the New Palgrave on Money Supply

by

Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

Do all banks hold reserves, and, if so, where do they hold them? (11/2001)

* ttp://research.stlouisfed.org/aggreg/ St. Louis Fed: Monetary Aggregates*

Discontinuance of M3 Publication

Investopedia: Money Zero Maturity (MZM)

External links

* ttps://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/88 Historical H.3 releases

Money Stock Measures (H.6)

U.S. MZM magnitude

an

velocity

used as a predictor of

inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reductio ...

Data on Monetary Aggregates in Australia

Monetary Survey

from

People's Bank of China

The People's Bank of China (officially PBC or informally PBOC; ) is the central bank of the People's Republic of China, responsible for carrying out monetary policy and regulation of financial institutions in mainland China, as determined by ...

{{Authority control

Monetary policy

Inflation