Monarchies in the Americas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

There are 12 monarchies in the Americas (

Canada's aboriginal peoples had systems of governance organised in a fashion similar to the Occidental concept of monarchy; European explorers often referred to hereditary leaders of tribes as kings. The present monarchy of Canada has its roots in the French and English monarchies, under the authority of which the area was colonised in the 16th–18th centuries, and later the British monarchy. The country became a self-governing confederation on 1 July 1867, recognised as a kingdom in its own right, but did not have full legislative autonomy from the British Crown until the passage of the Statute of Westminster on 11 December 1931, retaining the then-reigning monarch,

Canada's aboriginal peoples had systems of governance organised in a fashion similar to the Occidental concept of monarchy; European explorers often referred to hereditary leaders of tribes as kings. The present monarchy of Canada has its roots in the French and English monarchies, under the authority of which the area was colonised in the 16th–18th centuries, and later the British monarchy. The country became a self-governing confederation on 1 July 1867, recognised as a kingdom in its own right, but did not have full legislative autonomy from the British Crown until the passage of the Statute of Westminster on 11 December 1931, retaining the then-reigning monarch,

The monarchy of

The monarchy of

Most

Most

The

The

Brazil was created as a kingdom on 16 December 1815, when Prince João,

Brazil was created as a kingdom on 16 December 1815, when Prince João,

The

The

The

The

With the victory of the

With the victory of the

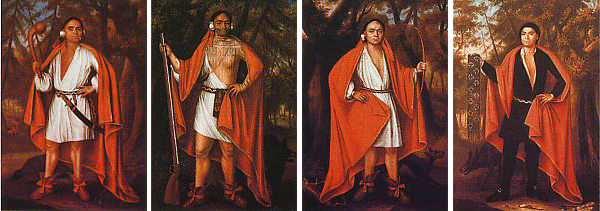

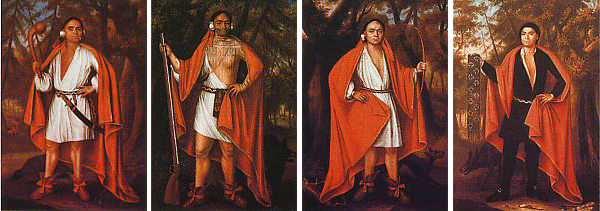

The Kingdom of Mosquitia controlled the Atlantic coasts of

The Kingdom of Mosquitia controlled the Atlantic coasts of  Contacts with pirates (French, Dutch and British) and Africans (seeking refuge to escape slavery) began in the 17th century. In 1629, English Puritans established on Providence Island, what they called New Westminster, the Providence Company. From dealing with British merchants and settlers, the Miskitu people obtain non-traditional products and firearms, which became a new cultural needs. This was also the time when the Kingdom start to gain its popularity.

The Kingdom of Mosquitia became a stronger force against the Spanish when the Miskitu King

Contacts with pirates (French, Dutch and British) and Africans (seeking refuge to escape slavery) began in the 17th century. In 1629, English Puritans established on Providence Island, what they called New Westminster, the Providence Company. From dealing with British merchants and settlers, the Miskitu people obtain non-traditional products and firearms, which became a new cultural needs. This was also the time when the Kingdom start to gain its popularity.

The Kingdom of Mosquitia became a stronger force against the Spanish when the Miskitu King  Through the act of what Great Britain called "

Through the act of what Great Britain called "

After a number of failed attempts at colonising

After a number of failed attempts at colonising

The United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves came into being in the wake of Portugal's war with Napoleonic France. The Portuguese Prince Regent, the future King John VI, with his incapacitated mother, Queen Maria I of Portugal and the Royal Court, Transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil, escaped to the colony of Brazil in 1808.

With the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, there were calls for the return of the Portuguese Monarch to Lisbon; the Portuguese Prince Regent enjoyed life in Rio de Janeiro, where the monarchy was at the time more popular and where he enjoyed more freedom, and he was thus unwilling to return to Europe. However, those advocating the return of the Court to Lisbon argued that Brazil was only a colony and that it was not right for Portugal to be governed from a colony. On the other hand, leading Brazilian courtiers pressed for the elevation of Brazil from the rank of a colony, so that they could enjoy the full status of being nationals of the mother-country. Brazilian nationalists also supported the move, because it indicated that Brazil would no longer be submissive to the interests of Portugal, but would be of equal status within a transatlantic monarchy.

The United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves came into being in the wake of Portugal's war with Napoleonic France. The Portuguese Prince Regent, the future King John VI, with his incapacitated mother, Queen Maria I of Portugal and the Royal Court, Transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil, escaped to the colony of Brazil in 1808.

With the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, there were calls for the return of the Portuguese Monarch to Lisbon; the Portuguese Prince Regent enjoyed life in Rio de Janeiro, where the monarchy was at the time more popular and where he enjoyed more freedom, and he was thus unwilling to return to Europe. However, those advocating the return of the Court to Lisbon argued that Brazil was only a colony and that it was not right for Portugal to be governed from a colony. On the other hand, leading Brazilian courtiers pressed for the elevation of Brazil from the rank of a colony, so that they could enjoy the full status of being nationals of the mother-country. Brazilian nationalists also supported the move, because it indicated that Brazil would no longer be submissive to the interests of Portugal, but would be of equal status within a transatlantic monarchy.

These entities were never recognized ''de jure'' as legitimate governments, but still sometimes exercised a certain degree of local control or influence within their respective locations until the death of their "monarch":

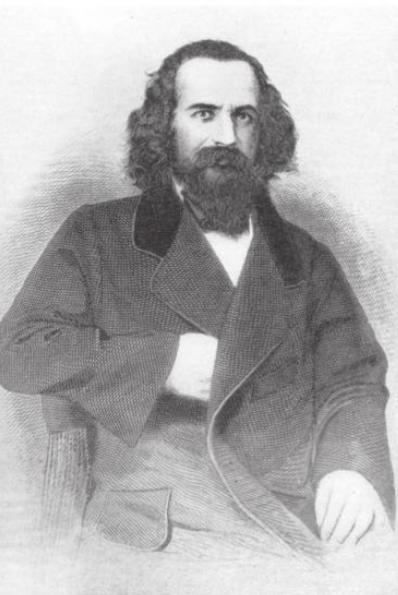

;James J. Strang

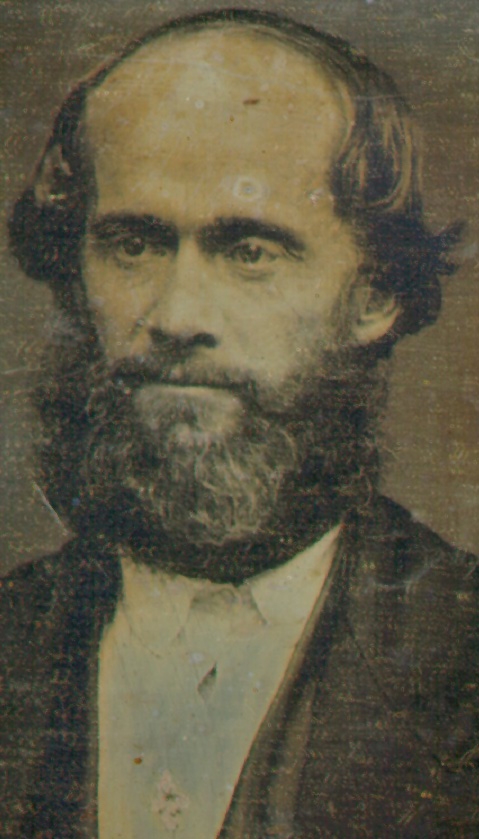

James Strang, a would-be successor to the Latter Day Saints, Mormon prophet Joseph Smith, Jr., proclaimed himself "king" over his Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Strangite), church in 1850, which was then concentrated mostly on Beaver Island (Lake Michigan), Beaver Island in Lake Michigan. On 8 July of that year, he was physically crowned in an elaborate coronation ceremony complete with crown, sceptre, throne, ermine robe and breastplate. Although he never claimed legal sovereignty over Beaver Island or any other geographical entity, Strang managed (as a member of the Michigan State Legislature) to have his "kingdom" constituted as a separate Manitou County, Michigan, county, where his followers held all county offices, and Strang's word was law. U.S. President Millard Fillmore ordered an investigation into Strang's colony, which resulted in Strang's trial in Detroit for treason, trespass, counterfeiting and other crimes, but the jury found the "king" innocent of all charges. Strang was eventually assassinated by two disgruntled followers in 1856, and his kingdom—together with his royal regalia—vanished.

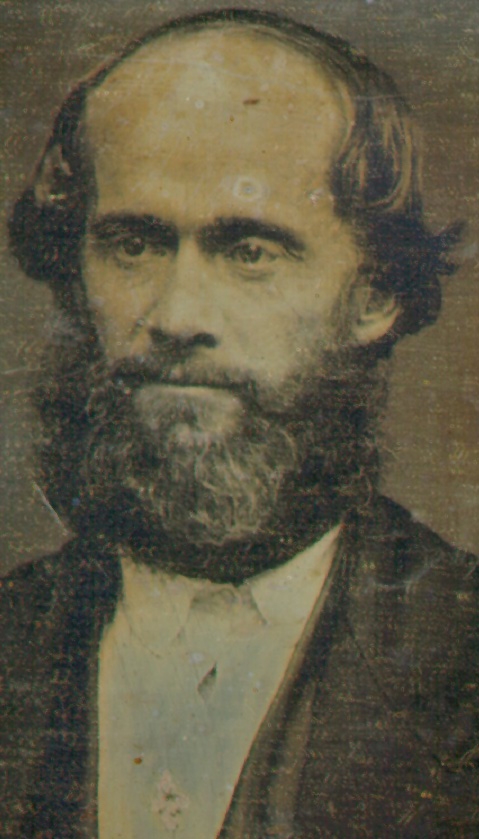

;Joshua Norton

Emperor Norton, Joshua Abraham Norton, an Englishman who emigrated to San Francisco, California in 1849, proclaimed himself "Emperor of These United States" in 1859, later adding the title "Protector of Mexico". Though never recognized by the U.S. or Mexican governments, he was accorded a certain degree of deference within San Francisco itself, including reserved balcony seats (for which he was never charged) at local theatres, and salutes by policemen who passed him on the street. He was active in various civic issues and advocated for the bridging of San Francisco Bay. Specially printed currency authorized by Norton was accepted as legal tender within several businesses in the city. When Norton died in 1880, he was given a lavish funeral attended by over 30,000 persons.

These entities were never recognized ''de jure'' as legitimate governments, but still sometimes exercised a certain degree of local control or influence within their respective locations until the death of their "monarch":

;James J. Strang

James Strang, a would-be successor to the Latter Day Saints, Mormon prophet Joseph Smith, Jr., proclaimed himself "king" over his Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Strangite), church in 1850, which was then concentrated mostly on Beaver Island (Lake Michigan), Beaver Island in Lake Michigan. On 8 July of that year, he was physically crowned in an elaborate coronation ceremony complete with crown, sceptre, throne, ermine robe and breastplate. Although he never claimed legal sovereignty over Beaver Island or any other geographical entity, Strang managed (as a member of the Michigan State Legislature) to have his "kingdom" constituted as a separate Manitou County, Michigan, county, where his followers held all county offices, and Strang's word was law. U.S. President Millard Fillmore ordered an investigation into Strang's colony, which resulted in Strang's trial in Detroit for treason, trespass, counterfeiting and other crimes, but the jury found the "king" innocent of all charges. Strang was eventually assassinated by two disgruntled followers in 1856, and his kingdom—together with his royal regalia—vanished.

;Joshua Norton

Emperor Norton, Joshua Abraham Norton, an Englishman who emigrated to San Francisco, California in 1849, proclaimed himself "Emperor of These United States" in 1859, later adding the title "Protector of Mexico". Though never recognized by the U.S. or Mexican governments, he was accorded a certain degree of deference within San Francisco itself, including reserved balcony seats (for which he was never charged) at local theatres, and salutes by policemen who passed him on the street. He was active in various civic issues and advocated for the bridging of San Francisco Bay. Specially printed currency authorized by Norton was accepted as legal tender within several businesses in the city. When Norton died in 1880, he was given a lavish funeral attended by over 30,000 persons.Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico

/ref> ;James Harden-Hickey James Harden-Hickey was a self-proclaimed prince, who attempted to establish the so-called Principality of Trinidad on Trindade Island, Trindade and the Martim Vaz Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean during the late 19th century. Although initially garnering some newspaper attention, Hickey's claims were ignored or ridiculed by other nations, and the islands eventually were occupied by military forces from nearby Brazil which remain there to the present day. ;Matthew Dowdy Shiell A self-proclaimed monarch of the so-called Kingdom of Redonda, an island in the Caribbean Sea. Whether M. P. Shiel ever actually claimed to be king of this tiny islet is open to debate; however, other individuals later claimed the title of "King of Redonda," without having apparently ever tried to physically establish themselves on the island itself.

self-governing

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

states and territories that have a monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority ...

as head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

). Each is a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, wherein the sovereign inherits his or her office, usually keeping it until death or abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

, and is bound by laws and customs in the exercise of their powers. Nine of these monarchies are independent states; they equally share King Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

, who resides primarily in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, as their respective sovereign, making them part of a global personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

known as the Commonwealth realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state in the Commonwealth of Nations whose monarch and head of state is shared among the other realms. Each realm functions as an independent state, equal with the other realms and nations of the Commonwealt ...

s. The others are dependencies of three European monarchies. As such, none of the monarchies in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

have a permanently residing monarch.

These crowns continue a history of monarchy in the Americas that reaches back to before European colonization

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turks, and the Arabs.

Colonialism in the modern sense began ...

. Both tribal and more complex pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era spans from the original settlement of North and South America in the Upper Paleolithic period through European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage of 1492. Usually, th ...

societies existed under monarchical forms of government, with some expanding to form vast empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

s under a central king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

figure, while others did the same with a decentralized collection of tribal regions under a hereditary chieftain

A tribal chief or chieftain is the leader of a tribe, tribal society or chiefdom.

Tribe

The concept of tribe is a broadly applied concept, based on tribal concepts of societies of western Afroeurasia.

Tribal societies are sometimes categori ...

. None of the contemporary monarchies, however, are descended from those pre-colonial royal systems, instead either having their historical roots in, or still being a part of, the current European monarchies

Monarchy was the prevalent form of government in the history of Europe throughout the Middle Ages, only occasionally competing with

communalism, notably in the case of the Maritime republics and the Swiss Confederacy.

Republicanism became more ...

that spread their reach across the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

, beginning in the mid 14th century.

From that date on, through the Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafarin ...

, European colonization brought extensive American territory under the control of Europe's monarchs, though the majority of these colonies subsequently gained independence from their rulers. Some did so via armed conflict with their mother countries, as in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

and the Latin American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

, usually severing all ties to the overseas monarchies in the process (today, none of the Latin American

Latin Americans ( es, Latinoamericanos; pt, Latino-americanos; ) are the citizens of Latin American countries (or people with cultural, ancestral or national origins in Latin America). Latin American countries and their diasporas are multi-eth ...

nations that were former Spanish colonies share a personal union with the Spanish monarchy

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

). Others gained full sovereignty by legislative paths, such as Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

's patriation

Patriation is the political process that led to full Canadian sovereignty, culminating with the Constitution Act, 1982. The process was necessary because under the Statute of Westminster 1931, with Canada's agreement at the time, the Parliament o ...

of its constitution from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

. A certain number of former colonies became republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

s immediately upon achieving self-governance. The remainder continued with endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

constitutional monarchies—in the cases of Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

, Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, and Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

—with their own resident monarch and, for places such as Canada and some island states in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

, sharing their monarch with their former metropole

A metropole (from the Greek ''metropolis'' for "mother city") is the homeland, central territory or the state exercising power over a colonial empire.

From the 19th century, the English term ''metropole'' was mainly used in the scope of ...

in a personal union, the most recently created being that of Saint Kitts and Nevis in 1983.

Current monarchies

American monarchies

While the incumbent of each of the American monarchies is the same person and resides predominantly in Europe, each of the states aresovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title which can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin , meaning 'above'.

The roles of a sovereign vary from monarch, ruler or ...

and thus have distinct local monarchies seated in their respective capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used f ...

s, with the monarch's day-to-day governmental and ceremonial duties generally carried out by an appointed local viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

.

Antigua and Barbuda

The monarchy ofAntigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda (, ) is a sovereign country in the West Indies. It lies at the juncture of the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean in the Leeward Islands part of the Lesser Antilles, at 17°N latitude. The country consists of two maj ...

has the roots in the Spanish monarchy

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

, under the authority of which the islands were first colonized in the late 15th century, and later the British monarchy

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiwi ...

, as a Crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Counci ...

. On 1 November 1981, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Antigua and Barbuda. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Antigua and Barbuda

The governor-general of Antigua and Barbuda is the representative of the monarch of Antigua and Barbuda, currently King Charles III. The official residence of the governor-general is Government House.

The position of governor-general was est ...

, Sir Rodney Williams.

Elizabeth and her royal consort, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 1921 – 9 April 2021) was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. As such, he served as the consort of the British monarch from El ...

, included Antigua and Barbuda in their 1966 Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

tour, and again in the Queen's Silver Jubilee tour of October 1977. Elizabeth returned once more in 1985. For the country's 25th anniversary of independence, on 30 October 2006, Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex

Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex and Forfar, (Edward Antony Richard Louis; born 10 March 1964) is a member of the British royal family. He is the youngest child of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and the youngest sibl ...

, opened Antigua and Barbuda's new parliament building, reading a message from his mother, the Queen. The Duke of York visited Antigua and Barbuda in January 2001.

The Bahamas

The monarchy ofThe Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

has its roots in the Spanish monarchy, under the authority of which the islands were first colonized in the late 15th century, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony, after 1717. On 10 July 1973, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly formed monarchy of The Bahamas. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of the Bahamas

The governor-general of the Bahamas is the vice-regal representative of the Bahamian monarch, currently King Charles III, in the Commonwealth of the Bahamas. The governor-general is appointed by the monarch on the recommendation of the prim ...

, Sir Cornelius A. Smith

Sir Cornelius Alvin Smith (born 7 April 1937) is a Bahamian politician and diplomat.

Smith became the 11th Governor-General of the Bahamas on 28 June 2019.

Biography

Smith was one of the first members of the Free National Movement upon it ...

.

Belize

Belize was, until the 15th century, a part of the Mayan Empire, containing smaller states headed by a hereditary ruler known as an ''ajaw

Ajaw or Ahau ('Lord') is a pre-Columbian Maya political title attested from epigraphic inscriptions. It is also the name of the 20th day of the ''tzolkʼin'', the Maya divinatory calendar, on which a ruler's ''kʼatun''-ending rituals would fal ...

'' (later ''k’uhul ajaw''). The present monarchy of Belize has its roots in the Spanish monarchy, under the authority of which the area was first colonised in the 16th century, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 21 September 1981, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly formed monarchy of Belize. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Belize

The governor-general of Belize is the vice-regal representative of the Belizean monarch, currently King Charles III, in Belize. The governor-general is appointed by the monarch on the recommendation of the prime minister of Belize. The function ...

, Her Excellency Froyla Tzalam

Dame Froyla Tzalam, , is a Belizean Mopan Maya anthropologist and community leader, who has served as the Governor-General of Belize since 27 May 2021.

She is the first indigenous person of Maya descent to serve as governor-general of any cou ...

.

Canada

Canada's aboriginal peoples had systems of governance organised in a fashion similar to the Occidental concept of monarchy; European explorers often referred to hereditary leaders of tribes as kings. The present monarchy of Canada has its roots in the French and English monarchies, under the authority of which the area was colonised in the 16th–18th centuries, and later the British monarchy. The country became a self-governing confederation on 1 July 1867, recognised as a kingdom in its own right, but did not have full legislative autonomy from the British Crown until the passage of the Statute of Westminster on 11 December 1931, retaining the then-reigning monarch,

Canada's aboriginal peoples had systems of governance organised in a fashion similar to the Occidental concept of monarchy; European explorers often referred to hereditary leaders of tribes as kings. The present monarchy of Canada has its roots in the French and English monarchies, under the authority of which the area was colonised in the 16th–18th centuries, and later the British monarchy. The country became a self-governing confederation on 1 July 1867, recognised as a kingdom in its own right, but did not have full legislative autonomy from the British Crown until the passage of the Statute of Westminster on 11 December 1931, retaining the then-reigning monarch, George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

, as monarch of the newly formed monarchy of Canada. The monarch is represented in the country by the governor general of Canada

The governor general of Canada (french: gouverneure générale du Canada) is the federal viceregal representative of the . The is head of state of Canada and the 14 other Commonwealth realms, but resides in oldest and most populous realm, t ...

(Currently, Dame Mary Simon

Mary Jeannie May Simon (in Inuktitut syllabics: ᒥᐊᓕ ᓴᐃᒪᓐ, iu, script=Latn, Ningiukudluk; born August 21, 1947) is a Canadian civil servant, diplomat, and former broadcaster who has served as the 30th governor general of Canada ...

) and in each of the provinces by a lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

.

Grenada

The monarchy ofGrenada

Grenada ( ; Grenadian Creole French: ) is an island country in the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea at the southern end of the Grenadines island chain. Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Pe ...

has its roots in the French monarchy, under the authority of which the islands were first colonised in the mid 17th century, and later the English and then British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 7 February 1974, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Grenada. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Grenada

The governor-general of Grenada is the vice-regal representative of the Grenadian monarch, currently King Charles III, in Grenada. The governor-general is appointed by the monarch on the recommendation of the prime minister of Grenada. The fun ...

, currently Dame Cécile La Grenade

Dame Cécile Ellen Fleurette La Grenade, (born 30 December 1952) is a Grenadian food scientist who has served as Governor-General of Grenada since 7 May 2013.

Early life

La Grenade was born in La Borie, located in Saint George Parish, Grena ...

.

Jamaica

The monarchy of

The monarchy of Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

has its roots in the Spanish monarchy, under the authority of which the islands were first colonised in the late 16th century, and later the English and then British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 6 August 1962, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Jamaica. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Jamaica

The governor-general of Jamaica is the viceregal representative of the Jamaican monarch, King Charles III, in Jamaica.

The monarch, on the advice of the prime minister, appoints a governor-general as his or her representative in Jamaica. Bot ...

, Sir Patrick Allen

John Keith Patrick Allen (17 March 1927 – 28 July 2006) was a British actor.

Life and career

Allen was born in Nyasaland (now Malawi), where his father was a tobacco farmer. After his parents returned to Britain, he was evacuated to Canada ...

.

Former Prime Minister of Jamaica

The prime minister of Jamaica is Jamaica's head of government, currently Andrew Holness. Holness, as leader of the governing Jamaica Labour Party (JLP), was sworn in as prime minister on 7 September 2020, having been re-elected as a result of ...

Portia Simpson-Miller

Portia Lucretia Simpson-Miller (born 12 December 1945) is a Jamaican politician. She served as Prime Minister of Jamaica from March 2006 to September 2007 and again from 5 January 2012 to 3 March 2016. She was the leader of the People's Nationa ...

had expressed an intention to oversee the process required to change Jamaica to a republic by 2012; she originally stated this would be complete by August of that year. In 2003, former Prime Minister P.J. Patterson

Percival Noel James Patterson, popularly known as P.J. Patterson (born 10 April 1935), is a Jamaican former politician who served as the sixth Prime Minister of Jamaica from 1992 to 2006. He served in office for 14 years, making him the longe ...

, advocated making Jamaica into a republic by 2007.

Saint Kitts and Nevis

The monarchy ofSaint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Kitts and Nevis (), officially the Federation of Saint Christopher and Nevis, is an island country and microstate consisting of the two islands of Saint Kitts and Nevis, both located in the West Indies, in the Leeward Islands chain of ...

has its roots in the English and French monarchies, under the authority of which the islands were first colonised in the early 17th century, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 19 September 1983, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Saint Kitts and Nevis. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Saint Kitts and Nevis

The governor-general of Saint Kitts and Nevis is the representative of the monarch of Saint Kitts and Nevis, currently King Charles III. The appointed Governor-General, currently Sir Tapley Seaton, lives in Government House, Basseterre, which s ...

, currently Sir Tapley Seaton

Sir Samuel Weymouth Tapley Seaton, (born 28 July 1950) is the fourth and current governor-general of Saint Kitts and Nevis. He was born on Saint Kitts, the son of William A. Seaton and his wife, Pearl A. Seaton, nee Godwin. He came to the posi ...

.

Saint Lucia

TheCaribs

“Carib” may refer to:

People and languages

*Kalina people, or Caribs, an indigenous people of South America

**Carib language, also known as Kalina, the language of the South American Caribs

*Kalinago people, or Island Caribs, an indigenous pe ...

who occupied the island of Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Amerindian ...

in pre-Columbian times had a complex society, with hereditary kings and shamans. The present monarchy has its roots in the Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, French, and English monarchies, under the authority of which the island was first colonised in 1605, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 22 February 1979, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Saint Lucia. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Saint Lucia

The governor-general of Saint Lucia is the representative of the Saint Lucian monarch, currently Charles III. The official residence of the governor-general is Government House.

The position of governor-general was established when Saint Luci ...

, currently Sir Errol Charles

Cyril Errol Melchiades Charles (born 10 December 1942) is a Saint Lucian politician, who has served as the acting governor-general of Saint Lucia since 11 November 2021, following the resignation of Sir Neville Cenac.

Early life and education ...

.

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

The present monarchy ofSaint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines () is an island country in the Caribbean. It is located in the southeast Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles, which lie in the West Indies at the southern end of the eastern border of the Caribbean Sea wh ...

has its roots in the French monarchy, under the authority of which the island was first colonised in 1719, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 27 October 1979, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Vincent and the Grenadines, currently Dame Susan Dougan

Dame Susan Dilys Dougan ( Ryan; born 3 March 1955) is the Governor-General of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines since 1 August 2019. She is the first woman to hold the office.

She was appointed Dame Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and ...

.

Settled monarchies

Denmark

Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

is one of the three constituent countries of the Kingdom of Denmark

The Danish Realm ( da, Danmarks Rige; fo, Danmarkar Ríki; kl, Danmarkip Naalagaaffik), officially the Kingdom of Denmark (; ; ), is a sovereign state located in Northern Europe and Northern North America. It consists of Denmark, metropolitan ...

, with Queen Margrethe II

Margrethe II (; Margrethe Alexandrine Þórhildur Ingrid, born 16 April 1940) is Queen of Denmark. Having reigned as Denmark's monarch for over 50 years, she is Europe's longest-serving current head of state and the world's only incumbent femal ...

as the reigning sovereign. The territory first came under monarchical rule in 1261, when the populace accepted the overlordship of the King of Norway

The Norwegian monarch is the head of state of Norway, which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system. The Norwegian monarchy can trace its line back to the reign of Harald Fairhair and the previous petty kingdoms ...

; by 1380, Norway had entered into a personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

with the Kingdom of Denmark, which became more entrenched with the union of the kingdoms into Denmark–Norway

Denmark–Norway (Danish and Norwegian: ) was an early modern multi-national and multi-lingual real unionFeldbæk 1998:11 consisting of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Kingdom of Norway (including the then Norwegian overseas possessions: the Faroe I ...

in 1536. After the dissolution of this arrangement in 1814, Greenland remained as a Danish colony, and, after its role in World War II, was granted its special status within the Kingdom of Denmark in 1953. The monarch is represented in the territory by the '' Rigsombudsmand'' ( High Commissioner), Mikaela Engell

Mikaela Engell (born 4 October 1956) is a Danish civil servant who served as High Commissioner of Greenland, a post she has held from 2011 to 2022. She had previously worked in the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, first as a Permanent Secreta ...

.

Netherlands

Aruba

Aruba ( , , ), officially the Country of Aruba ( nl, Land Aruba; pap, Pais Aruba) is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands physically located in the mid-south of the Caribbean Sea, about north of the Venezuela peninsula of ...

, Curaçao

Curaçao ( ; ; pap, Kòrsou, ), officially the Country of Curaçao ( nl, Land Curaçao; pap, Pais Kòrsou), is a Lesser Antilles island country in the southern Caribbean Sea and the Dutch Caribbean region, about north of the Venezuela coast ...

and Sint Maarten

Sint Maarten () is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Caribbean. With a population of 41,486 as of January 2019 on an area of , it encompasses the southern 44% of the divided island of Saint Martin, while the north ...

are constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands

, national_anthem = )

, image_map = Kingdom of the Netherlands (orthographic projection).svg

, map_width = 250px

, image_map2 = File:KonDerNed-10-10-10.png

, map_caption2 = Map of the four constituent countries shown to scale

, capital = ...

and thus have King Willem-Alexander

Willem-Alexander (; Willem-Alexander Claus George Ferdinand; born ) is King of the Netherlands, having acceded to the throne following his mother's abdication in 2013.

Willem-Alexander was born in Utrecht as the oldest child of Princess Beatr ...

as their sovereign, as do the islands of the Caribbean Netherlands

)

, image_map = BES islands location map.svg

, map_caption = Location of the Caribbean Netherlands (green and circled). From left to right: Bonaire, Saba, and Sint Eustatius

, elevation_max_m = 887

, elevation_max_footnotes =

, demographics ...

. Aruba was first settled under the authority of the Spanish Crown circa 1499, but was acquired by the Dutch in 1634, under whose control the island has remained, save for an interval between 1805 and 1816, when Aruba was captured by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

of King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

. The former Netherlands Antilles

nl, In vrijheid verenigd"Unified by freedom"

, national_anthem =

, common_languages = Dutch English Papiamento

, demonym = Netherlands Antillean

, capital = Willemstad

, year_start = 1954

, year_end = 2010

, date_start = 15 December

, ...

were originally discovered by explorers sent in the 1490s by the King of Spain, but were eventually conquered by the Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company ( nl, Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie, ''WIC'' or ''GWC''; ; en, Chartered West India Company) was a chartered company of Dutch merchants as well as foreign investors. Among its founders was Willem Usselincx ( ...

in the 17th century, whereafter the islands remained under the control of the Dutch Crown as colonial territories. The Netherlands Antilles achieved the status of an autonomous country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1954, from which Aruba was split in 1986 as a separate constituent country of the larger kingdom. The former Netherlands Antilles was dissolved in 2010; two of its islands became constituent countries in their own right (Curaçao

Curaçao ( ; ; pap, Kòrsou, ), officially the Country of Curaçao ( nl, Land Curaçao; pap, Pais Kòrsou), is a Lesser Antilles island country in the southern Caribbean Sea and the Dutch Caribbean region, about north of the Venezuela coast ...

and Sint Maarten

Sint Maarten () is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Caribbean. With a population of 41,486 as of January 2019 on an area of , it encompasses the southern 44% of the divided island of Saint Martin, while the north ...

), while the other three became integral parts of the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

(i.e., the Caribbean Netherlands). The monarch is represented in the constituent countries by the Governor of Aruba

The governor of Aruba is the representative on Aruba of the Dutch monarch. The governor's duties are twofold; he represents and guards the general interests of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and is head of the Aruban government. He is accountab ...

, Alfonso Boekhoudt

Juan Alfonso Boekhoudt (born 27 January 1965) is an Aruban politician serving as the governor of Aruba since 1 January 2017. He previously served as minister plenipotentiary from 14 November 2013 to 17 November 2016.

Life

Boekhoudt was born on Ar ...

, the Governor of Curaçao

The governor of Curaçao ( nl, gouverneur van Curaçao; pap, gobernador di Kòrsou) is the representative on Curaçao of the Dutch head of state (King Willem-Alexander). The governor's duties are twofold: representing and guarding the general in ...

, Frits Goedgedrag

Frits M. de los Santos Goedgedrag (born 1 November 1951 in Aruba) is a Dutch Antillean politician who was the first governor of Curaçao following the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles. During his tenure, he oversaw the dissolution of the Ne ...

, and the Governor of Sint Maarten

The governor of Sint Maarten is the representative on Sint Maarten of the Dutch head of state (King Willem-Alexander). The governor's duties are twofold: he represents and guards the general interests of the kingdom and is head of the governmen ...

, Eugene Holiday

Eugene Bernard Holiday (born 14 December 1962) is a Sint Maarten politician and the first governor of Sint Maarten, which became a country ( nl, land) within the Kingdom of the Netherlands on 10 October 2010. He was installed by the Council of Min ...

.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom possesses a number ofoverseas territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or an ...

in the Americas, for whom King Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

is monarch. In North America are Anguilla

Anguilla ( ) is a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is one of the most northerly of the Leeward Islands in the Lesser Antilles, lying east of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands and directly north of Saint Martin. The territo ...

, Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

, the British Virgin Islands

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = Territorial song

, song = "Oh, Beautiful Virgin Islands"

, image_map = File:British Virgin Islands on the globe (Americas centered).svg

, map_caption =

, mapsize = 290px

, image_map2 = Brit ...

, the Cayman Islands

The Cayman Islands () is a self-governing British Overseas Territory—the largest by population in the western Caribbean Sea. The territory comprises the three islands of Grand Cayman, Cayman Brac and Little Cayman, which are located to the ...

, Montserrat

Montserrat ( ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is part of the Leeward Islands, the northern portion of the Lesser Antilles chain of the West Indies. Montserrat is about long and wide, with r ...

, and the Turks and Caicos Islands

The Turks and Caicos Islands (abbreviated TCI; and ) are a British Overseas Territory consisting of the larger Caicos Islands and smaller Turks Islands, two groups of tropical islands in the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean and n ...

, while the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouzet ...

, and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type =

, song =

, image_map = South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in United Kingdom.svg

, map_caption = Location of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in the southern Atlantic Oce ...

are located in South America. The Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

islands were colonised under the authority or the direct instruction of a number of European monarchs, mostly English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

, Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, or Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

, throughout the first half of the 17th century. By 1681, however, when the Turks and Caicos Islands were settled by Britons, all of the above-mentioned islands were under the control of Charles II of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Colonies were merged and split through various reorganizations of the Crown's Caribbean regions, until 19 December 1980, the date that Anguilla became a British Crown territory in its own right. The monarch is represented in these jurisdictions by: the Governor of Anguilla

The Governor of Anguilla is the representative of the monarch in the British Overseas Territory of Anguilla. The Governor is appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British government. The Governor is the highest authority on Anguill ...

, Dileeni Daniel-Selvaratnam

Dileeni Daniel-Selvaratnam is a British lawyer and civil servant who has served as Governor of Anguilla since 18 January 2021. She is the second female holder of the position after Christina Scott.

On 15 December 2022, the Foreign, Commonweal ...

; the Governor of Bermuda, Rena Lalgie

Rena Lalgie is a British civil servant serving as Governor of Bermuda since 2020.

She is the first woman, and the first person of African-Caribbean heritage, to be appointed governor of Bermuda.Governor of the British Virgin Islands

The Governor of the Virgin Islands is the representative of the British monarch in the United Kingdom's overseas territory of the British Virgin Islands. The governor is appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British government. The ...

, John Rankin; the Governor of the Cayman Islands

The Governor of the Cayman Islands is the representative of the British monarch in the United Kingdom's overseas territory of the Cayman Islands. The Governor, a civil servant who has in modern times typically been a British subject normally res ...

, Martyn Roper

Martyn Keith Roper (born 8 June 1965) is a British diplomat and civil servant who has been Governor of the Cayman Islands since 29 October 2018.

Roper was the List of ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Algeria, British Ambassador to Algeria ...

; the Governor of Montserrat

The Governor of Montserrat is the representative of the British monarch in the United Kingdom's overseas territory of Montserrat. The Governor is appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British government. The main role of the Governor ...

, Sarah Tucker; and the Governor of the Turks and Caicos Islands

The Governor of the Turks and Caicos Islands is the representative of the British monarch in the United Kingdom's British Overseas Territory of Turks and Caicos Islands. The Governor is appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British g ...

, Nigel Dakin

Nigel John Dakin (born 28 February 1964) is a British diplomat currently serving as Governor of the Turks and Caicos Islands. He assumed office on 15 July 2019 in a swearing-in ceremony before the territory's House of Assembly.

On 15 December 2 ...

.

The Falkland Islands, off the south coast of Argentina, were simultaneously claimed for Louis XV of France

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

, in 1764, and George III of the United Kingdom

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until Acts of Union 1800, the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was ...

, in 1765, though the French colony was ceded to Charles III of Spain

it, Carlo Sebastiano di Borbone e Farnese

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Philip V of Spain

, mother = Elisabeth Farnese

, birth_date = 20 January 1716

, birth_place = Royal Alcazar of Madrid, Spain

, death_d ...

in 1767. By 1833, however, the islands were under full British control. The South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands were discovered by Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

for George III in January 1775, and from 1843 were governed by the British Crown-in-Council through the Falkland Islands, an arrangement that stood until the South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands were incorporated as a distinct British overseas territory in 1985. The monarch is represented in these regions by Nigel Phillips

Air Commodore Nigel James Phillips, (born 10 May 1963) is a British diplomat, former Royal Air Force officer and former Governor of the Falkland Islands and Commissioner of the South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. He has served as Gov ...

, who is both the Governor of the Falkland Islands

The governor of the Falkland Islands is the representative of the British Crown in the Falkland Islands, acting "in His Majesty's name and on His Majesty's behalf" as the islands' ''de facto'' head of state in the absence of the British monarch ...

and the Commissioner for South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

The Commissioner for South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands is the representative of the British monarch in the United Kingdom's overseas territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. The post is held in conjunction with the ...

.

Succession laws

Before 28 October 2011, thesuccession order

An order of succession or right of succession is the line of individuals necessitated to hold a high office when it becomes vacated such as head of state or an honour such as a title of nobility.male-preference cognatic primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

, by which succession passed first to an individual's sons, in order of birth, and subsequently to daughters, again in order of birth. However, following the legislative changes giving effect to the Perth Agreement

The Perth Agreement was made in Australia in 2011 by the prime ministers of the sixteen states known as Commonwealth realms, which at the time all recognised Elizabeth II as their head of state. The document agreed that the governments of the re ...

, succession is by absolute primogeniture for those born after 28 October 2011, whereby the eldest child inherits the throne regardless of gender. As these states share the person of their monarch with other countries, all with legislative independence, the change was implemented only once the necessary legal processes were completed in each realm. Those possessions under the Danish and Dutch crowns already adhere to absolute primogeniture.

Former monarchies

Most

Most pre-Columbian cultures

This list of pre-Columbian cultures includes those civilizations and cultures of the Americas which flourished prior to the European colonization of the Americas.

Cultural characteristics

Many pre-Columbian civilizations established permanent o ...

of the Americas developed and flourished for centuries under monarchical systems of government. By the time Europeans arrived on the continents in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, however, many of these civilizations had ceased to function, due to various natural and artificial causes. Those that remained up to that period were eventually defeated by the agents of European monarchical powers, who, while they remained on the European continent, thereafter established new American administrations overseen by delegated viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

s. Some of these colonies were, in turn, replaced by either republican states or locally founded monarchies, ultimately overtaking the entire American holdings of some European monarchs; those crowns that once held or claim territory in the Americas include the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

, Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

, French, Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

, and Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

, and even Baltic Courland, Holy Roman, Prussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

and Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

. Certain of the locally established monarchies were themselves also overthrown through revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

, leaving five current pretenders to American thrones.

Barbados

The monarchy of Barbados had its roots in the English monarchy, under the authority of which the island was claimed in 1625 and first colonized in 1627, and later the British monarchy. By the 18th century, Barbados became one of the main seats of the British Crown's authority in theBritish West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were colonized British territories in the West Indies: Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grena ...

, and then, after an attempt in 1958 at a federation with other West Indian colonies, continued as a self-governing colony

In the British Empire, a self-governing colony was a colony with an elected government in which elected rulers were able to make most decisions without referring to the colonial power with nominal control of the colony. This was in contrast to a ...

until, on 30 November 1966, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly formed monarchy of Barbados. The monarch was represented in the country by the Governor-General of Barbados

The governor-general of Barbados was the representative of the Barbadian monarch from independence in 1966 until the establishment of a republic in 2021. Under the government's Table of Precedence for Barbados, the governor-general of Barbados ...

.

In 1966, Elizabeth's cousin, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, (Edward George Nicholas Paul Patrick; born 9 October 1935) is a member of the British royal family. Queen Elizabeth II and Edward were first cousins through their fathers, King George VI, and Prince George, Duk ...

, opened the second session of the first parliament of the newly established country, before the Queen herself, along with Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, toured Barbados. Elizabeth returned for her Silver Jubilee in 1977, and again in 1989, to mark the 350th anniversary of the establishment of the Barbadian parliament.

Former Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Owen Arthur

Owen Seymour Arthur, PC (17 October 194927 July 2020) was a Barbadian politician who served as the fifth prime minister of Barbados from 6 September 1994 to 15 January 2008. He is the longest-serving Barbadian prime minister to date. He also ...

called for a referendum on Barbados becoming a republic to be held in 2005, though the vote was then pushed back to "at least 2006" in order to speed up Barbados' integration in the CARICOM Single Market and Economy

The CARICOM Single Market and Economy, also known as the Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME), is an integrated development strategy envisioned at the 10th Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM ...

. It was announced on 26 November 2007 that the referendum would be held in 2008, together with the general election that year. The vote was, however, postponed again to a later point, due to administrative concerns. On 20 September 2021, just over a full year after the announcement for the transition was made, the Constitution (Amendment) (No. 2) Bill, 2021 was introduced to the Parliament of Barbados. Passed on 6 October, the Bill made amendments to the Constitution of Barbados, introducing the office of the President to replace the Barbadian monarch as head of state. The next week on 12 October 2021, incumbent Governor-General of Barbados

The governor-general of Barbados was the representative of the Barbadian monarch from independence in 1966 until the establishment of a republic in 2021. Under the government's Table of Precedence for Barbados, the governor-general of Barbados ...

Dame Sandra Mason

Dame Sandra Prunella Mason (born 17 January 1949) is a Barbadian politician, lawyer, and diplomat who is serving as the first president of Barbados since 2021. She was previously the eighth and final governor-general of Barbados from 2018 to 20 ...

was jointly nominated by the prime minister and leader of the opposition as candidate for the first president of Barbados, and was subsequently elected Elected may refer to:

* "Elected" (song), by Alice Cooper, 1973

* ''Elected'' (EP), by Ayreon, 2008

*The Elected, an American indie rock band

See also

*Election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population ...

on 20 October. Mason took office on 30 November 2021.

Endemic monarchies

Araucania and Patagonia

Kingdom of Araucania and Patagonia

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

was a short-lived attempt at establishing a constitutional monarchy, founded by French lawyer and adventurer Orelie-Antoine de Tounens in 1860. Nominally, the "kingdom" encompassed the present-day Argentine

Argentines (mistakenly translated Argentineans in the past; in Spanish (masculine) or (feminine)) are people identified with the country of Argentina. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Argentines, s ...

part of Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and gl ...

and a small segment of Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, where Mapuche

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who sha ...

peoples were fighting to maintain their sovereignty against the advancing Chilean and Argentine armed forces. However, Orélie-Antoine never exercised sovereignty over the claimed territory, and his ''de facto'' control was limited to nearly fourteen months and to a small territory around a town called Perquenco (at the time mainly a Mapuche tent village), which was also the declared capital of his ''kingdom''.

Orélie-Antoine felt that the indigenous peoples would be better served in negotiations with the surrounding powers by a European leader, and was accordingly elected by a group of Mapuche ''loncos'' (chieftains) to be their king. He made efforts to gain international recognition

Diplomatic recognition in international law is a unilateral declarative political act of a state that acknowledges an act or status of another state or government in control of a state (may be also a recognized state). Recognition can be accord ...

, and attempted to involve the French government in his project, but these efforts proved unsuccessful: the French consul concluded that Tounens was insane, and Araucania and Patagonia was never recognized by any country. The Chileans primarily ignored Orélie-Antoine and his kingdom, at least initially, and simply went on with the occupation of the Araucanía

Occupation commonly refers to:

*Occupation (human activity), or job, one's role in society, often a regular activity performed for payment

*Occupation (protest), political demonstration by holding public or symbolic spaces

*Military occupation, th ...

, a historical process which concluded in 1883 with Chile establishing control over the region. In the process, Orélie-Antoine was captured in 1862, and imprisoned in an insane asylum in Chile. After several fruitless attempts to return to his kingdom (thwarted by Chilean and Argentine authorities), Tounens died penniless in 1878 in Tourtoirac

Tourtoirac (; oc, Tortoirac) is a Communes of France, commune in the Dordogne Departments of France, department in Nouvelle-Aquitaine in southwestern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Dordogne department

References

Comm ...

, France. A recent pretender, Prince Antoine IV, lived in France until 2017. The previous pretender renounced his claims to the Patagonian throne, even though a few Mapuches continue to recognise the Araucanian monarchy.

Aztec

TheAztec

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those g ...

Empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

existed in the central Mexican region between c. 1325 and 1521, and was formed by the triple alliance of the ''tlatoque

''Tlatoani'' ( , "one who speaks, ruler"; plural ' or tlatoque) is the Classical Nahuatl term for the ruler of an , a pre-Hispanic state. It is the noun form of the verb "tlahtoa" meaning "speak, command, rule". As a result, it has been variousl ...

'' (the Nahuatl

Nahuatl (; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller ...

term for "speaker", also translated in English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

as "king") of three city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s: Tlacopan

Tlacopan, also called Tacuba, was a Tepanec / Mexica altepetl on the western shore of Lake Texcoco. The site is today the neighborhood of Tacuba, in Mexico City.

Etymology

The name comes from Classical Nahuatl ''tlacōtl'', "stem" or "rod" and ...

, Texcoco, and the capital of the empire, Tenochtitlan

, ; es, Tenochtitlan also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, ; es, México-Tenochtitlan was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear. The date 13 March 1325 was ...

. While the lineage of Tenochtitlan's kings continued after the city's fall to the Spanish on 13 August 1521, they reigned as puppet rulers of the King of Spain

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

until the death of the last dynastic ''tlatoani'', Luis de Santa María Nanacacipactzin, on 27 December 1565.

Brazil

Brazil was created as a kingdom on 16 December 1815, when Prince João,

Brazil was created as a kingdom on 16 December 1815, when Prince João, Prince of Brazil

Prince of Brazil ( pt, Príncipe do Brasil) was the title held by the heir-apparent to the Kingdom of Portugal, from 1645 to 1815. Tied with the title of Prince of Brazil was the title Duke of Braganza and the various subsidiary titles of the ...

, who was then acting as regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

for his ailing mother, Queen Maria, elevated the colony to a constituent country of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves

The United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves was a pluricontinental monarchy formed by the elevation of the Portuguese colony named State of Brazil to the status of a kingdom and by the simultaneous union of that Kingdom of Brazil w ...

. While the royal court was still based in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

, João ascended as king of the united kingdom the following year, and returned to Portugal in 1821, leaving his son, Prince Pedro, Prince Royal, as his regent in the Kingdom of Brazil

The Kingdom of Brazil ( pt, Reino do Brasil) was a constituent kingdom of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil, and the Algarves.

Creation

The legal entity of the Kingdom of Brazil was created by a law issued by Prince Regent John of Portu ...

. In September of that same year, the Portuguese parliament threatened to diminish Brazil back to the status of a colony, dismantle all the royal agencies in Rio de Janeiro, and demanded Pedro return to Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

. The Prince, however, feared these moves would trigger separatist movements and refused to comply; instead, at the urging of his father, he declared Brazil an independent Nation on 7 September 1822, leading to the formation of the Empire of Brazil