Miles M.52 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Miles M.52 was a turbojet-powered supersonic research aircraft project designed in the United Kingdom in the mid-1940s. In October 1943,

''http://www.space.co.uk''. Retrieved: 12 October 2009. The

An initial version of the aircraft was to be test-flown using

An initial version of the aircraft was to be test-flown using

The fuselage of the M.52 was cylindrical and, like the rest of the aircraft, was constructed of high tensile steel with light-alloy covering.Wood 1975, p. 30. The fuselage had the minimum cross-section allowable around the centrifugal engine with fuel tanks in a

The fuselage of the M.52 was cylindrical and, like the rest of the aircraft, was constructed of high tensile steel with light-alloy covering.Wood 1975, p. 30. The fuselage had the minimum cross-section allowable around the centrifugal engine with fuel tanks in a

On 8 October 1947, the first launch of a test model occurred from high altitude; however, the rocket unintentionally exploded shortly following its release. Only days later, on 14 October, the Bell X-1 broke the sound barrier. There was a flurry of denunciation of the government's decision to cancel the project, with the '' Daily Express'' taking up the cause for the restoration of the M.52 programme, to no effect. On 10 October 1948, a second rocket was launched, and the speed of Mach 1.38 was obtained in stable level flight, a unique achievement at that time. By this point, the X-1 and Yeager had already reached M1.45 on 25 March of that year.Miller 2001, . Instead of diving into the sea as planned, the model failed to respond to radio commands and was last observed (on

On 8 October 1947, the first launch of a test model occurred from high altitude; however, the rocket unintentionally exploded shortly following its release. Only days later, on 14 October, the Bell X-1 broke the sound barrier. There was a flurry of denunciation of the government's decision to cancel the project, with the '' Daily Express'' taking up the cause for the restoration of the M.52 programme, to no effect. On 10 October 1948, a second rocket was launched, and the speed of Mach 1.38 was obtained in stable level flight, a unique achievement at that time. By this point, the X-1 and Yeager had already reached M1.45 on 25 March of that year.Miller 2001, . Instead of diving into the sea as planned, the model failed to respond to radio commands and was last observed (on

Faster than Sound – Nova documentary

A video of a modern radio controlled model replica of the M.52 flying

Eric "Winkle" Brown talks about the M.52 in 2008

"High Speed Research" (pdf download). ''The Aeroplane Spotter'', 19 October 1946.

* ttp://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1947/1947%20-%200487.html Supersonic Approach by H. F. King, M.B.E.''Flight'' 3 April 1947*

Ministry of Supply report "Flight Trials of a Rocket-propelled Transonic Research Model : The R.A.E.-Vickers Rocket Model"

a 1946 ''Flight'' article on the M.52-based Vickers test rocket. {{Authority control 1940s British experimental aircraft Cancelled aircraft projects M.52 Rocket-powered aircraft Military history of the United Kingdom during World War II History of science and technology in the United Kingdom

Miles Aircraft

Miles was the name used between 1943 and 1947 to market the aircraft of British engineer Frederick George Miles, who, with his wife – aviator and draughtswoman Maxine "Blossom" Miles (née Forbes-Robertson) – and his brother George Herbert ...

was issued with a contract to produce the aircraft in accordance with Air Ministry Specification E.24/43. The programme was highly ambitious for its time, aiming to produce an aircraft and engine capable of unheard-of speeds of at least during level flight, and involved a very high proportion of cutting-edge aerodynamic

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dyn ...

research and innovative design work.

Between 1942 and 1945, all work on the project was undertaken with a high level of secrecy. In February 1946, the programme was terminated by the new Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

government of Clement Attlee, seemingly due to budgetary reasons, as well as a disbelief held by some ministry officials concerning the viability of supersonic aircraft in general. In September 1946 the existence of the M.52 was revealed to the general public, leading to calls for official explanation as to why the project had been terminated and derision of the decision. The Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of State ...

controversially decided to revive the design, but as a series of unmanned rocket-powered 30 per cent scale models instead of the original manned full-scale aircraft that had been previously under development. These unmanned scale models were air-launched from a modified de Havilland Mosquito mother ship

A mother ship, mothership or mother-ship is a large vehicle that leads, serves, or carries other smaller vehicles. A mother ship may be a maritime ship, aircraft, or spacecraft.

Examples include bombers converted to carry experimental airc ...

.

During one successful test flight, Mach 1.38 was achieved by a scale model in normally controllable transonic

Transonic (or transsonic) flow is air flowing around an object at a speed that generates regions of both subsonic and supersonic airflow around that object. The exact range of speeds depends on the object's critical Mach number, but transoni ...

and supersonic level flight, a unique achievement at that time which validated the aerodynamics of the M.52. At that point, the ministry had cancelled that project and issued a new requirement, which would ultimately result in the English Electric Lightning

The English Electric Lightning is a British fighter aircraft that served as an interceptor during the 1960s, the 1970s and into the late 1980s. It was capable of a top speed of above Mach 2. The Lightning was designed, developed, and manufa ...

interceptor aircraft

An interceptor aircraft, or simply interceptor, is a type of fighter aircraft designed specifically for the defensive interception role against an attacking enemy aircraft, particularly bombers and reconnaissance aircraft. Aircraft that are c ...

. Work on the afterburning version of the Power Jets

Power Jets was a British company set up by Frank Whittle for the purpose of designing and manufacturing jet engines. The company was nationalised in 1944, and evolved into the National Gas Turbine Establishment.

History

Founded on 27 Januar ...

W.B.2/700 turbojet was also cancelled and the Power Jets company was incorporated into the National Gas Turbine Establishment

The National Gas Turbine Establishment (NGTE Pyestock) in Farnborough, part of the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE), was the prime site in the UK for design and development of gas turbine and jet engines. It was created by merging the design te ...

. According to senior figures at Miles, the design and the research gained from the M.52 was shared with the American company Bell Aircraft

The Bell Aircraft Corporation was an American aircraft manufacturer, a builder of several types of fighter aircraft for World War II but most famous for the Bell X-1, the first supersonic aircraft, and for the development and production of man ...

, and that this was applied to their own Bell X-1, a ground-breaking high-speed experimental aircraft which broke the sound barrier.

Development

Background

Prior to theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, conventional wisdom throughout the majority of the aviation industry was that manned flight at supersonic speeds, those in excess of the sound barrier

The sound barrier or sonic barrier is the large increase in aerodynamic drag and other undesirable effects experienced by an aircraft or other object when it approaches the speed of sound. When aircraft first approached the speed of sound, th ...

, was next to impossible, mainly due to the apparently insurmountable issue of compressibility

In thermodynamics and fluid mechanics, the compressibility (also known as the coefficient of compressibility or, if the temperature is held constant, the isothermal compressibility) is a measure of the instantaneous relative volume change of a f ...

.Wood 1975, p. 27. During the 1930s, few researchers and aerospace engineers chose to explore the field of high-speed fluid dynamics; notable pioneers in this area were the German aerospace engineer Adolf Busemann, British physicist Sir Geoffrey Taylor, and British engine designer Sir Stanley Hooker.Wood 1975, pp. 27–28. While Germany gave considerable attention to exploring and implementing Busemann's theories on the swept wing and its role in drag-reduction during high-speed flight, both Britain and the United States overlooked this research on the whole. It was only by 1944 that information regarding the rocket-propelled Messerschmitt Me 163

The Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet is a rocket-powered interceptor aircraft primarily designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Messerschmitt. It is the only operational rocket-powered fighter aircraft in history as well as ...

or the jet-propelled Me 262

The Messerschmitt Me 262, nicknamed ''Schwalbe'' (German: "Swallow") in fighter versions, or ''Sturmvogel'' (German: "Storm Bird") in fighter-bomber versions, is a fighter aircraft and fighter-bomber that was designed and produced by the German ...

, both having been equipped with swept wings, did wider attitudes on its merits begin to change. Prior to this point, the British Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of State ...

had already launched a research programme of its own.Wood 1975, pp. 27–29.

In Autumn 1943, the Air Ministry issued a call for nothing less than a revolutionary aircraft in the form of Air Ministry Specification E.24/43.Wood 1975, pp. 28–29. The Specification sought to produce a jet-powered research aircraft for the ambitious purpose of being able to reach supersonic speeds, far faster than any aircraft had ever flown at that point. It called for an "aeroplane capable of flying over in level flight, over twice the existing speed record at that time, along with the ability to climb to in 1.5 minutes." The E.24/43 has been described as being "the most far-sighted official requirement ever to be issued by a Government department...a complete venture into the unknown with engine, airframe, and control techniques beyond anything remotely considered before". In fact, the specification had only been intended to produce a British aircraft that could match the supposed performance of an apparently existing German aircraft: the 1,000 ''mph'' (supersonic) requirement had resulted from the mistranslation of an intercepted communication which had reported that the maximum speed to have been 1,000 ''km/h'' ( subsonic). This report is believed to have been referring to either the Messerschmitt Me 163A or the Me 262. "UK Space Conference 2008: Test Pilot Discussion."''http://www.space.co.uk''. Retrieved: 12 October 2009. The

Miles Aircraft

Miles was the name used between 1943 and 1947 to market the aircraft of British engineer Frederick George Miles, who, with his wife – aviator and draughtswoman Maxine "Blossom" Miles (née Forbes-Robertson) – and his brother George Herbert ...

company had its beginnings in the 1920s and made a name for itself during the 1930s by producing affordable ranges of innovative light aircraft, perhaps the best known amongst these being the Miles Magister

The Miles M.14 Magister is a two-seat monoplane basic trainer aircraft designed and built by the British aircraft manufacturer Miles Aircraft. It was affectionately known as the ''Maggie''. It was authorised to perform aerobatics.

The Magister ...

and Miles Master

The Miles M.9 Master was a British two-seat monoplane advanced trainer designed and built by aviation company Miles Aircraft Ltd. It was inducted in large numbers into both the Royal Air Force (RAF) and Fleet Air Arm (FAA) during the Second W ...

trainers, large numbers of both types seeing heavy use by the RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

for fighter pilot training. Although the company's products were relatively low-technology trainers and light aircraft, and did not include any jet-propelled aircraft,Brown 1970. Miles had a good relationship with the Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of State ...

and the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE), and had submitted several proposals for advanced aircraft in response to ministry specifications. Miles was invited to undertake a top-secret project to meet the requirements of Specification E.24/43; thus began Miles' involvement in high-speed aviation.Wood 1975, p. 29. The decision to involve the company has been alleged to have been partially in order to resolve a dispute about a separated contract that allegedly had been mishandled by the Ministry of Aircraft Production; Wood states that the Minister of Aircraft Production

The Minister of Aircraft Production was, from 1940 to 1945, the British government minister at the Ministry of Aircraft Production, one of the specialised supply ministries set up by the British Government during World War II. It was responsible ...

Sir Stafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps (24 April 1889 – 21 April 1952) was a British Labour Party politician, barrister, and diplomat.

A wealthy lawyer by background, he first entered Parliament at a by-election in 1931, and was one of a handful of La ...

had been impressed by Miles' designs and development team and thus favoured it to meet the specification.

Fred Miles of Miles Aircraft was summoned to the Ministry of Aircraft to meet with researcher Ben Lockspeiser

Sir Ben Lockspeiser, KCB, FRS, MIMechE, FRAeS (9 March 1891 – 18 October 1990) was a British scientific administrator and the first President of CERN.

Early life and education

Lockspeiser was born at 7 President Street in the City of Lond ...

for the latter to outline the difficulties and challenges involved in developing such an aircraft. The project required the highest level of secrecy throughout, Miles being responsible for the development and manufacturing of the airframe while Frank Whittle

Air Commodore Sir Frank Whittle, (1 June 1907 – 8 August 1996) was an English engineer, inventor and Royal Air Force (RAF) air officer. He is credited with inventing the turbojet engine. A patent was submitted by Maxime Guillaume in 1921 fo ...

's Power Jets

Power Jets was a British company set up by Frank Whittle for the purpose of designing and manufacturing jet engines. The company was nationalised in 1944, and evolved into the National Gas Turbine Establishment.

History

Founded on 27 Januar ...

company developed and produced a suitable engine to equip the aircraft. For this project, Miles would cooperate with and receive assistance from the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) in Farnborough and the National Physical Laboratory. On 8 October 1943, Miles received the formal go-ahead to proceed from Air Marshal Ralph Sorley

Air Marshal Sir Ralph Squire Sorley, (9 January 1898 – 17 November 1974) was a senior commander in the Royal Air Force (RAF). He began was a pilot in the Royal Naval Air Service during the First World War, and rose to senior command in the Se ...

, and immediately set about establishing appropriate secure facilities for the project.

Early development

Faced with limited amounts of existing relevant information from available sources upon which to base the aircraft's design, Miles turned to the field of ballistics instead. He had reasoned that as it was widely known that bullets could attain supersonic speeds, aerodynamic properties that would enable an aircraft to be capable of becoming supersonic would likely to be present amongst such shapes. In particular, as a result of studying this design data, the emerging aircraft would feature both a conical nose and very thinelliptical

Elliptical may mean:

* having the shape of an ellipse, or more broadly, any oval shape

** in botany, having an elliptic leaf shape

** of aircraft wings, having an elliptical planform

* characterised by ellipsis (the omission of words), or by conc ...

wings complete with sharp leading edge

The leading edge of an airfoil surface such as a wing is its foremost edge and is therefore the part which first meets the oncoming air.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition'', page 305. Aviation Supplies & Academics, ...

s. This contrasted with many early jet aircraft, which had round noses, thick wings and hinged elevator

An elevator or lift is a cable-assisted, hydraulic cylinder-assisted, or roller-track assisted machine that vertically transports people or freight between floors, levels, or decks of a building, vessel, or other structure. They a ...

s, resulting in these aircraft having critical Mach number

In aerodynamics, the critical Mach number (Mcr or M*) of an aircraft is the lowest Mach number at which the airflow over some point of the aircraft reaches the speed of sound, but does not exceed it.Clancy, L.J. ''Aerodynamics'', Section 11.6 At t ...

s below the speed of sound; thus they were less suitable for research into high subsonic speeds (in dives) than the earlier Supermarine Spitfire with its thinner wings. In 1943, RAE tests conducted using Spitfires had proved that drag was the main factor that would need to be addressed by high-speed aircraft.

Another critical addition was the use of a power-operated stabilator, also known as the all-moving tail or flying tail

A stabilator is a fully movable aircraft horizontal stabilizer. It serves the usual functions of longitudinal stability, control and stick force requirements otherwise performed by the separate parts of a conventional horizontal stabilizer and el ...

, a key to supersonic flight control which contrasted with traditional elevators hinged to tailplane

A tailplane, also known as a horizontal stabiliser, is a small lifting surface located on the tail (empennage) behind the main lifting surfaces of a fixed-wing aircraft as well as other non-fixed-wing aircraft such as helicopters and gyropla ...

s (horizontal stabilizers). Conventional control surfaces became ineffective at the high subsonic speeds then being achieved by fighters in dives, due to the aerodynamic forces caused by the formation of shockwaves at the hinge and the rearward movement of the centre of pressure, which together could override the control forces that could be applied mechanically by the pilot, hindering recovery from the dive. A major impediment to early transonic flight was control reversal Control reversal is an adverse effect on the controllability of aircraft. The flight controls reverse themselves in a way that is not intuitive, so pilots may not be aware of the situation and therefore provide the wrong inputs; in order to roll to ...

, the phenomenon which caused flight inputs (stick, rudder) to switch direction at high speed; it was the cause of many accidents and near-accidents. An ''all-flying tail'' is considered to be a minimum condition of enabling aircraft to break the transonic barrier safely without a loss of pilot control. The M.52 was the first instance of this solution, which has since gone on to be universally applied upon high-speed aircraft.

An initial version of the aircraft was to be test-flown using

An initial version of the aircraft was to be test-flown using Frank Whittle

Air Commodore Sir Frank Whittle, (1 June 1907 – 8 August 1996) was an English engineer, inventor and Royal Air Force (RAF) air officer. He is credited with inventing the turbojet engine. A patent was submitted by Maxime Guillaume in 1921 fo ...

's latest engine, the Power Jets

Power Jets was a British company set up by Frank Whittle for the purpose of designing and manufacturing jet engines. The company was nationalised in 1944, and evolved into the National Gas Turbine Establishment.

History

Founded on 27 Januar ...

W.2/700. This engine, which was estimated to be capable of providing 2,000 lb of thrust, calculated to be capable of providing subsonic performance; when flown in a shallow dive, it would also be capable of transonic flight. Wood described the engine as being "remarkable as it incorporated ideas far ahead of its time". In order to get the M.52 to achieve supersonic speeds, the installation of projected further development of the W.2/700 engine would be necessary.

This further advanced model of the engine, intended to be a fully supersonic version of the aircraft, was partially achieved by the incorporation of a ''reheat jetpipe'' – also known as an afterburner

An afterburner (or reheat in British English) is an additional combustion component used on some jet engines, mostly those on military supersonic aircraft. Its purpose is to increase thrust, usually for supersonic flight, takeoff, and co ...

. Extra fuel was to be burned in the tailpipe to avoid overheating the turbine blades, making use of unused oxygen present in the exhaust. To supply more air to the afterburner than could move through the fairly small engine, an ''augmentor'' fan powered by the engine was to be fitted behind the engine to draw air around the engine via ducts. These changes were estimated to provide an additional 1,620 lb of thrust at 36,000 ft and 500 mph. Much greater thrust gains were believed to be available at speeds in excess of 500 mph.

The M.52's design underwent many changes during development due to the uncertain nature of the task. The overseeing committee was concerned that the biconvex wing would not give sufficient altitude for testing the aircraft in a dive. The thin wing could have been made thicker if required, or a section added to increase the wing span. As the project progressed, an increase in total weight led to concerns that power would be insufficient; thus, the adoption of rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

assistance or extra fuel tanks were considered. Another proposed measure was that the M.52 be adapted to become a parasite aircraft

A parasite aircraft is a component of a composite aircraft which is carried aloft and air launched by a larger carrier aircraft or mother ship to support the primary mission of the carrier. The carrier craft may or may not be able to later reco ...

, launching at high altitude from beneath a large bomber serving as a mother ship

A mother ship, mothership or mother-ship is a large vehicle that leads, serves, or carries other smaller vehicles. A mother ship may be a maritime ship, aircraft, or spacecraft.

Examples include bombers converted to carry experimental airc ...

.Wood 1975, p. 31. The calculated landing speed of (comparable with modern fighters but high for that time) combined with its relatively small undercarriage track was another concern; however, this arrangement was accepted.

Testing

During 1943, a single Miles M.3B Falcon Six light aircraft, which had been previously used for wing tests by the RAE, was provided to Miles for purpose of performing low-speed flight testing work on the project. A full size wooden model of the M.52 wing, test instrumentation, and a different undercarriage were fitted to this aircraft. Owing to the wing's thinness and sharp leading and trailing edges somewhat resembling arazor blade

A razor is a bladed tool primarily used in the removal of body hair through the act of shaving. Kinds of razors include straight razors, safety razors, disposable razors, and electric razors.

While the razor has been in existence since before ...

, the aircraft was nicknamed the "Gillette Falcon". On 11 August 1944, this low-speed demonstrator performed its maiden flight

The maiden flight, also known as first flight, of an aircraft is the first occasion on which it leaves the ground under its own power. The same term is also used for the first launch of rockets.

The maiden flight of a new aircraft type is alw ...

. These tests found the wing to present favourable aileron function, but also indicated that landing without flap

Flap may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Flap'' (film), a 1970 American film

* Flap, a boss character in the arcade game ''Gaiapolis''

* Flap, a minor character in the film '' Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland''

Biology and he ...

s to be more difficult than its contemporaries. Compared with a standard Falcon Six, wing area was reduced by about 12 per cent; it had the effect of increasing the landing speed by over 50 per cent from , higher than any prior aircraft.

For high-speed testing, the flying tail of the M.52 was fitted to the fastest aircraft then available, a Supermarine Spitfire. RAE test pilot Eric Brown stated that he tested this aircraft successfully during October and November 1944; on one such flight, he managed to attain a recorded speed of Mach 0.86 during a dive from high altitude. The flying tail was also fitted to the "Gillette Falcon", which proceeded to conduct a series of low speed flight tests at the RAE in April 1945.Brown 2006

Due to the limited capability of existing wind tunnel

Wind tunnels are large tubes with air blowing through them which are used to replicate the interaction between air and an object flying through the air or moving along the ground. Researchers use wind tunnels to learn more about how an aircraft ...

facilities in Britain, Miles elected to manufacture their own wind tunnel, which was used to conduct the first M.52 aerodynamic tests. This undertaking necessitated Miles to construct their own on-site small-scale foundry

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

, both due to secrecy requirements and to produce components of sufficient tolerance. By August 1945, the design of the M.52 had been firmly established and development had proceeded to an advanced stage. By early 1946, 90 per cent of the detailed design work had been finished, the component assembly programme was well underway, while the jig

The jig ( ga, port, gd, port-cruinn) is a form of lively folk dance in compound metre, as well as the accompanying dance tune. It is most associated with Irish music and dance. It first gained popularity in 16th-century Ireland and parts of ...

s and innovative augmentor fan had been manufactured; a maiden flight of the first M-52 prototype had been anticipated to occur that summer.

Design

The Miles M.52 was envisioned to be a supersonic research aircraft capable of achieving in level flight. In order to achieve what was at the time previously unachievable speeds, a very high number of advanced features were incorporated into the design of the M.52; many of which had been the product of detailed study and acquired knowledge of supersonicaerodynamics

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dy ...

. Wood summarises the qualities of the M.52's design as possessing "all the ingredients of a high-performance aircraft of the late fifties and even some of the early sixties".

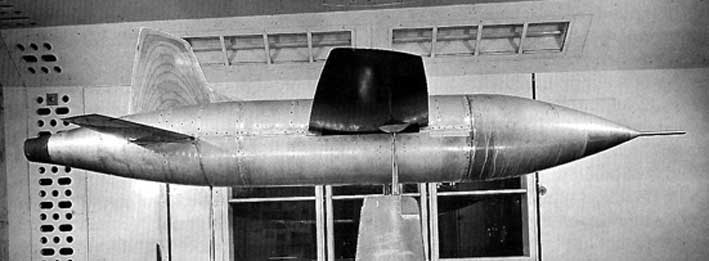

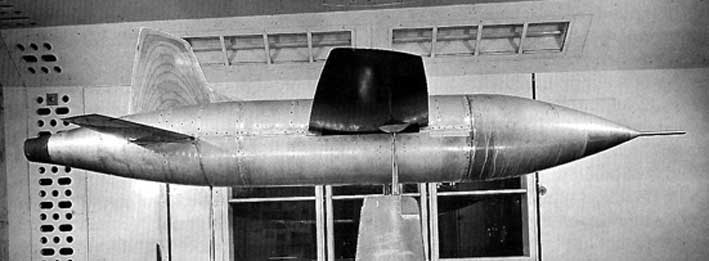

The fuselage of the M.52 was cylindrical and, like the rest of the aircraft, was constructed of high tensile steel with light-alloy covering.Wood 1975, p. 30. The fuselage had the minimum cross-section allowable around the centrifugal engine with fuel tanks in a

The fuselage of the M.52 was cylindrical and, like the rest of the aircraft, was constructed of high tensile steel with light-alloy covering.Wood 1975, p. 30. The fuselage had the minimum cross-section allowable around the centrifugal engine with fuel tanks in a saddle

The saddle is a supportive structure for a rider of an animal, fastened to an animal's back by a girth. The most common type is equestrian. However, specialized saddles have been created for oxen, camels and other animals. It is not k ...

-like arrangement placed over the upper area around it. The engine was positioned with its center of gravity

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force ma ...

coincident with that of the aircraft and the wings were attached to the main structure just aft of the engine. The use of a shock cone

Inlet cones (sometimes called shock cones or inlet centerbodies) are a component of some supersonic aircraft and missiles. They are primarily used on ramjets, such as the D-21 Tagboard and Lockheed X-7. Some turbojet aircraft including the Su-7 ...

in the nose was another key design choice; the inlet cone slowed incoming air to the subsonic speeds determined by the engine, but with lower losses than a subsonic aircraft pitot intake. A retractable tricycle undercarriage

Tricycle gear is a type of aircraft undercarriage, or ''landing gear'', arranged in a tricycle fashion. The tricycle arrangement has a single nose wheel in the front, and two or more main wheels slightly aft of the center of gravity. Tricycle g ...

was used. The nose wheel was positioned close to the pilot's feet and the main wheels were fitted onto the main fuselage, folding out under the wings when deployed.

The M.52 had very thin wings of biconvex section, which had been first proposed by Jakob Ackeret

Jakob Ackeret, FRAeS (17 March 1898 – 27 March 1981) was a Swiss aeronautical engineer. He is widely viewed as one of the foremost aeronautics experts of the 20th century.

Birth and education

Jakob Ackeret was born in 1898 in Switzerland. He ...

, as they gave a low level of drag. These wings were so thin that they were known to test pilots as ' Gillette' wings, named after the brand of razor

A razor is a bladed tool primarily used in the removal of body hair through the act of shaving. Kinds of razors include straight razors, safety razors, disposable razors, and electric razors.

While the razor has been in existence since bef ...

. The wing tips were "clipped" to keep them clear of the conical shock wave

In physics, a shock wave (also spelled shockwave), or shock, is a type of propagating disturbance that moves faster than the local speed of sound in the medium. Like an ordinary wave, a shock wave carries energy and can propagate through a me ...

that was generated by the nose of the aircraft. Both wide- chord ailerons and split-flap

Flap may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Flap'' (film), a 1970 American film

* Flap, a boss character in the arcade game ''Gaiapolis''

* Flap, a minor character in the film '' Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland''

Biology and he ...

s were fitted to the wings. As a high-speed wing of this shape and size had not been tested before, Miles produced a full-scale wooden model of the wing for aerodynamic testing purposes; other representative portions of the aircraft, such as the tailplane, would be similarly produced and underwent low-speed flight testing.Wood 1975, pp. 29–30.

The Power Jets W.2/700 turbojet

The turbojet is an airbreathing jet engine which is typically used in aircraft. It consists of a gas turbine with a propelling nozzle. The gas turbine has an air inlet which includes inlet guide vanes, a compressor, a combustion chamber, an ...

engine was intended to be the first powerplant for the M.52. Initial aircraft would have been powered by a less-capable 'interim' model of the W.2/700 and thus be limited to subsonic speeds only; it did not feature either the afterburner

An afterburner (or reheat in British English) is an additional combustion component used on some jet engines, mostly those on military supersonic aircraft. Its purpose is to increase thrust, usually for supersonic flight, takeoff, and co ...

or the additional aft fan that were to be present on the projected more advanced version with which later-built M.52s would have been equipped.Wood 1975, pp. 30–31. In addition to the W.2/700 engine, a centrifugal-flow jet engine, designs were prepared for the M.52 to be fitted with a variety of different engines and types of propulsion, including what would become the newer Rolls-Royce Avon

The Rolls-Royce Avon was the first axial flow jet engine designed and produced by Rolls-Royce. Introduced in 1950, the engine went on to become one of their most successful post-World War II engine designs. It was used in a wide variety of ...

axial-flow

An axial compressor is a gas compressor that can continuously pressurize gases. It is a rotating, airfoil-based compressor in which the gas or working fluid principally flows parallel to the axis of rotation, or axially. This differs from other ...

jet engine, and a liquid-fuel rocket motor

A rocket engine uses stored rocket propellants as the reaction mass for forming a high-speed propulsive jet of fluid, usually high-temperature gas. Rocket engines are reaction engines, producing thrust by ejecting mass rearward, in accordan ...

s.

The M.52's single pilot, who, for the intended first flight, would have been test pilot Eric Brown, would have flown the aircraft from a small cockpit which was set inside the shock cone at the nose of the aircraft. The pressurised cockpit, in which the pilot would have had to fly the aircraft in a semi-prone

Prone position () is a body position in which the person lies flat with the chest down and the back up. In anatomical terms of location, the dorsal side is up, and the ventral side is down. The supine position is the 180° contrast.

Etymolog ...

position, was complete with a curved windscreen that was aligned with the contours of the bullet-shaped nose. In the event of an emergency, the entire section could be jettisoned, the separation from the rest of aircraft being initiated via multiple cordite

Cordite is a family of smokeless propellants developed and produced in the United Kingdom since 1889 to replace black powder as a military propellant. Like modern gunpowder, cordite is classified as a low explosive because of its slow burn ...

-based explosive bolt

A pyrotechnic fastener (also called an explosive bolt, or pyro, within context) is a fastener, usually a nut or bolt, that incorporates a pyrotechnic charge that can be initiated remotely. One or more explosive charges embedded within the bolt a ...

s. Air pressure would force the detached capsule off the fuselage while a parachute would slow its descent; during the capsule's descent, the pilot would bail out at a lower altitude and then parachute to safety. In order to serve its role as a research aircraft, the M.52 was to be equipped with comprehensive flight instrumentation, including automated instrument recorders and strain gauging throughout the structure connected to an oscilloscope.

Operational history

Prototypes

In 1944, design work was considered 90 per cent complete and Miles was told to proceed with the construction of a total of three prototype M.52s. Later that year, the Air Ministry signed an agreement with theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

to exchange high-speed research and data. Miles Chief Aerodynamicist Dennis Bancroft stated that the Bell Aircraft

The Bell Aircraft Corporation was an American aircraft manufacturer, a builder of several types of fighter aircraft for World War II but most famous for the Bell X-1, the first supersonic aircraft, and for the development and production of man ...

company was given access to the drawings and research on the M.52;Wood 1975, p. 36. however, the U.S. reneged on the agreement and no data was forthcoming in return. Unknown to Miles, Bell had already started construction of a rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

-powered supersonic design of their own but, having adopted a conventional tail for their aircraft, were battling the problem of control. A variable-incidence tail appeared to be the most promising solution; the Miles and RAE tests supported this conclusion.Brown 1980, p. 42. Later, following the conversion of the aircraft's tail, pilot Chuck Yeager

Brigadier General Charles Elwood Yeager ( , February 13, 1923December 7, 2020) was a United States Air Force officer, flying ace, and record-setting test pilot who in October 1947 became the first pilot in history confirmed to have exceeded the ...

practically verified these results during his test flights, and all subsequent supersonic aircraft would either have an all-moving tailplane or a delta wing.

Cancellation

In February 1946, Miles was informed by Lockspeiser of the immediate discontinuation of the project and to cease work on the M.52. Frank Miles later stated of this decision: "I did not know what to say or think when this extraordinary decision was sprung upon me, without warning of any kind. At our last official design meeting all members, including the Ministry and Power Jets' representatives, had been cheerful and optimistic". According to Frank Miles, when he approached Lockspeiser for reasons behind the cancellation, he was informed that it was due to economic reasons; Lockspeiser also stated his belief that aeroplanes would not fly supersonically for many years and may not ever do so.Wood 1975, pp. 31–32. By this point, the postwarLabour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

government, headed by Clement Attlee, had implemented dramatic budget cuts in various areas, which may have provided an inducement for the cancellation of the M.52, which was projected to involve considerable cost.Wood 1975, pp. 34–35. According to Wood, "the decision not to go ahead was purely a political one made by the Attlee Government".Wood 1975, p. 34.

In February 1946, around the same time as the termination of the M.52's development, Frank Whittle

Air Commodore Sir Frank Whittle, (1 June 1907 – 8 August 1996) was an English engineer, inventor and Royal Air Force (RAF) air officer. He is credited with inventing the turbojet engine. A patent was submitted by Maxime Guillaume in 1921 fo ...

resigned from Power Jets, stating that this was due to his disagreement with official policy.Wood 1975, p. 32. At the point of cancellation, the first of the three M.52s had been 82 per cent completed and it had been scheduled to commence the first test flights within only a few months. The test programme would have involved the progressive testing and development of the M.52 by the RAE, initially without reheat installed. The ultimate aim of the tests would have been to have achieved Mach 1.07 by the end of 1946.

Miles made a last ditch attempt to revive the project, submitting a proposal for a single near-complete M.52 prototype to be outfitted with a captured German rocket engine and automated controls, eliminating the requirement for a pilot to be on board. However, this proposal was rejected. Due to the project falling under the Official Secrets Act, the existence of the M.52 was unknown to the wider British public; thus, neither the nation nor the world knew that a supersonic aircraft had nearly been built, nor of its unceremonious termination. The Ministry repeatedly refused to allow Miles to hold press conferences on the M.52 and, while conducting its own press conference on the topic of high-speed flight on 18 July 1946, the Ministry made no mention of the project at all. It wasn't until September 1946 that the Ministry allowed Miles to announce the existence of the M.52 and its cancellation.

Upon the announcement of the M.52's existence, there was a huge amount of press interest in the story, who pressured the government to provide more detail on the cancellation. A spokesman for the Ministry of Supply eventually commented on the topic, suggesting that other approaches had been suggested by later research that were being pursued in place of the M.52. According to Wood, the response from the Ministry was "a complete smokescreen...it was unthinkable to admit that supersonic expertise was non-existent."Wood 1975, pp. 32–33. Lockspeiser's role in cancelling the M.52 became public knowledge, leading to his decision being derided in the press as "Ben's blunder".Wood 1975, p. 33.

It was not until February 1955 that another official reason for the M.52's cancellation emerged; a white paper

A white paper is a report or guide that informs readers concisely about a complex issue and presents the issuing body's philosophy on the matter. It is meant to help readers understand an issue, solve a problem, or make a decision. A white pape ...

issued that month stated that "the decision was also taken in 1946 that, in light of the limited knowledge then available, the risk of attempting supersonic flight in manned aircraft was unacceptably high and that our research into the problems involved should be conducted in the first place by means of air launched models."Wood 1975, pp. 38–39. This same paper acknowledged that the termination decision had seriously delayed the advancement of aeronautical progress by Britain.Wood 1975, p. 39. It has since been widely recognised that the cancellation of the M.52 was a major setback in British progress in the field of supersonic design.

In 1947, Miles Aircraft Ltd entered receivership

In law, receivership is a situation in which an institution or enterprise is held by a receiver—a person "placed in the custodial responsibility for the property of others, including tangible and intangible assets and rights"—especially in c ...

and the company was subsequently re-structured; its aircraft assets including the design data for the M.52 were acquired by Handley Page.

Subsequent work

Instead of a revival of the full-scale M.52, the government decided to institute a new programme involving expendable, pilotless, rocket-propelled missiles; it was envisioned that a total of 24 flights would be performed by these models, which would explore six different wing and control surface configurations, including alternative straight wing and swept wing arrangements.Wood 1975, pp. 34–37. Wood referred to the failure to revive the full-scale aircraft as "at one stroke Britain had opted out of the supersonic manned aircraft race".Wood 1975, p. 36. The contract for the expendable missiles was not issued to Miles but toVickers-Armstrongs

Vickers-Armstrongs Limited was a British engineering conglomerate formed by the merger of the assets of Vickers Limited and Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Company in 1927. The majority of the company was nationalised in the 1960s and 1970s, w ...

, whose design team was led by noted British engineer and inventor Barnes Wallis.Wood 1975, p. 37. While the base design work was conducted by Wallis' team, engine development was performed by the RAE itself. The product of these efforts was a 30 per cent scale radio-controlled model of the original M.52 design, powered by a single Armstrong Siddeley Beta

Armstrong Siddeley Beta was an early rocket engine, intended for use in supersonic aircraft.

The Miles M.52, the intended British contender for supersonic flight, had been cancelled in 1946 due to uncertainty concerning its turbojet engine's th ...

rocket engine, fuelled by a mix of high-test peroxide.

In total, there had been an overall interval of 15 months between the termination of the manned M.52 and the emergence of the first flight-ready rocket-powered test model. As envisioned, the test model would be launched from altitude via a flying mother ship

A mother ship, mothership or mother-ship is a large vehicle that leads, serves, or carries other smaller vehicles. A mother ship may be a maritime ship, aircraft, or spacecraft.

Examples include bombers converted to carry experimental airc ...

in the form of a modified de Havilland Mosquito; it was installed upon a purpose-built rack installed in between the aircraft's bomb bay doors. Shortly after launch, its onboard autopilot

An autopilot is a system used to control the path of an aircraft, marine craft or spacecraft without requiring constant manual control by a human operator. Autopilots do not replace human operators. Instead, the autopilot assists the operator' ...

was to level the model out prior to the rocket motor being started. Within 70 seconds of being released, the model was envisioned to be capable of achieving a speed of Mach 1.3 (880 mph); it was then to descend into the ocean below without any chance of recovery. The acquired data on each flight was to be provided via transmitted radio telemetry

Telemetry is the in situ collection of measurements or other data at remote points and their automatic transmission to receiving equipment (telecommunication) for monitoring. The word is derived from the Greek roots ''tele'', "remote", an ...

, which was received by a ground station based on the Scilly Isles

The Isles of Scilly (; kw, Syllan, ', or ) is an archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England. One of the islands, St Agnes, is the most southerly point in Britain, being over further south than the most southerly point of the ...

.

On 8 October 1947, the first launch of a test model occurred from high altitude; however, the rocket unintentionally exploded shortly following its release. Only days later, on 14 October, the Bell X-1 broke the sound barrier. There was a flurry of denunciation of the government's decision to cancel the project, with the '' Daily Express'' taking up the cause for the restoration of the M.52 programme, to no effect. On 10 October 1948, a second rocket was launched, and the speed of Mach 1.38 was obtained in stable level flight, a unique achievement at that time. By this point, the X-1 and Yeager had already reached M1.45 on 25 March of that year.Miller 2001, . Instead of diving into the sea as planned, the model failed to respond to radio commands and was last observed (on

On 8 October 1947, the first launch of a test model occurred from high altitude; however, the rocket unintentionally exploded shortly following its release. Only days later, on 14 October, the Bell X-1 broke the sound barrier. There was a flurry of denunciation of the government's decision to cancel the project, with the '' Daily Express'' taking up the cause for the restoration of the M.52 programme, to no effect. On 10 October 1948, a second rocket was launched, and the speed of Mach 1.38 was obtained in stable level flight, a unique achievement at that time. By this point, the X-1 and Yeager had already reached M1.45 on 25 March of that year.Miller 2001, . Instead of diving into the sea as planned, the model failed to respond to radio commands and was last observed (on radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, we ...

) heading out into the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

. Following that successful supersonic test flight, further work on this project was cancelled, being followed up immediately by the issue of Ministry of Supply Experimental Requirement ER.103.

One of the official reasons given for the cancellation was "the high cost for little return".Wood 1975, pp. 37–38. Wood commented of the model programme: "with the money thus wasted the piloted M.52 could have been completed and flown and a great store of invaluable information obtained...the pilot was shown to be essential for any worthwhile development process and a well designed test-bed aircraft to be a ''sine qua non'' for full-scale knowledge".Wood 1975, p. 38.

Many important design principles that were incorporated in the M.52 did not reappear until the mid- to late 1950s, with the development of truly supersonic aircraft such as the Fairey Delta 2

The Fairey Delta 2 or FD2 (internal designation Type V within Fairey) is a British supersonic research aircraft that was produced by the Fairey Aviation Company in response to a specification from the Ministry of Supply for a specialised aircra ...

, and the English Electric P.1

The English Electric Lightning is a British fighter aircraft that served as an interceptor during the 1960s, the 1970s and into the late 1980s. It was capable of a top speed of above Mach 2. The Lightning was designed, developed, and manufac ...

which became the highly regarded English Electric Lightning. And the X-1, D-558-2, F-100, F-101, F-102, F-104, Mig-19 etc. in the 40s and early 50s. The wing design of the M.52 was similar to the supersonic Wasserfall

The ''Wasserfall Ferngelenkte FlaRakete'' (Waterfall Remote-Controlled A-A Rocket) was a German guided supersonic surface-to-air missile project of World War II. Development was not completed before the end of the war and it was not used operati ...

German rocket. Both of those aircraft were developed in response (initially) to requirement ER.103 of 1947, informed by the knowledge gained from the M.52 aircraft and missile research projects together with German experimental data.

Specifications (M.52)

See also

References

Notes

Bibliography

* Amos, Peter. ''Miles Aircraft – The Early Years: The Story of F G Miles and his Aeroplanes, 1925–1939''. Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air-Britain (Historians) Ltd, 2009. . * Brown, Don Lambert. ''Miles Aircraft Since 1925''. London: Putnam & Company, 1970. . * Brown, Eric. "Miles M.52: The Supersonic Dream." ''Air Enthusiast Thirteen,'' August–November 1980. pp. 35–42 . * Brown, Eric. ''The Miles M.52: Gateway to Supersonic Flight''. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: The History Press, 2012. . * Brown, Eric. ''Wings on my Sleeve''. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2006. . * ''Breaking Sound Barrier''. Secret History (Channel 4) documentary, first broadcast 7 July 1997. Heavily re-edited as ''Faster than Sound''. NOVA (PBS) documentary, first broadcast 14 October 1997. * Buttler, Tony. "Miles M.52: Britain's Top Secret Supersonic Research Aircraft". Crécy Publishing Ltd, Manchester, 2016. . * McDonnell, Patrick. "Beaten to the Barrier." ''Aeroplane Monthly'' Volume 26, No. 1, Issue 297, January 1998. * Miller, Jay. ''The X-planes: X-1 to X-45.'' Midland Publishing, 2001. . * Pisano, Dominick A., R. Robert van der Linden and Frank H. Winter. ''Chuck Yeager and the Bell X-1: Breaking the Sound Barrier''. Washington, DC: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (in association with Abrams, New York), 2006. . * Temple, Julian C. ''Wings Over Woodley – The Story of Miles Aircraft and the Adwest Group''. Bourne End, Bucks, UK: Aston Publications, 1987. . * Wood, Derek. ''Project Cancelled''. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company Inc., 1975. . * Yeager, Chuck et al. ''The Quest for Mach One: A First-Person Account of Breaking the Sound Barrier''. New York: Penguin Studio, 1997. .External links

Faster than Sound – Nova documentary

A video of a modern radio controlled model replica of the M.52 flying

Eric "Winkle" Brown talks about the M.52 in 2008

"High Speed Research" (pdf download). ''The Aeroplane Spotter'', 19 October 1946.

* ttp://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1947/1947%20-%200487.html Supersonic Approach by H. F. King, M.B.E.''Flight'' 3 April 1947*

Ministry of Supply report "Flight Trials of a Rocket-propelled Transonic Research Model : The R.A.E.-Vickers Rocket Model"

a 1946 ''Flight'' article on the M.52-based Vickers test rocket. {{Authority control 1940s British experimental aircraft Cancelled aircraft projects M.52 Rocket-powered aircraft Military history of the United Kingdom during World War II History of science and technology in the United Kingdom