Madame Roland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Marie-Jeanne 'Manon' Roland de la Platière (

Marie-Jeanne Phlipon, known as Manon,According to some sources - and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France - her first name was Jeanne-Marie. The biographies written about her give Marie-Jeanne a first name. was the daughter of Pierre Gatien Phlipon, an engraver, and his wife Marguerite Bimont, daughter of a

Marie-Jeanne Phlipon, known as Manon,According to some sources - and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France - her first name was Jeanne-Marie. The biographies written about her give Marie-Jeanne a first name. was the daughter of Pierre Gatien Phlipon, an engraver, and his wife Marguerite Bimont, daughter of a

In 1776, Manon Phlipon met

In 1776, Manon Phlipon met

Madame Roland soon became a well-known figure in political circles in Paris, especially thanks to Brissot, who introduced her everywhere. As always, she worked alongside her husband, although the routine copying and editing work was now done by an assistant, Sophie Grandchamp. Madame Roland wrote most of her husbands official letters and regretted that she could not go to the new National Assembly herself to argue the case of Lyon: women were admitted only to the public gallery. When she observed the debates from the gallery, it annoyed her that the conservatives were so much better and more eloquent in the debates than the revolutionaries, who she considered ideologically superior. Outside the assembly she was active as a lobbyist. With Roland, she was a regular visitor at the

Madame Roland soon became a well-known figure in political circles in Paris, especially thanks to Brissot, who introduced her everywhere. As always, she worked alongside her husband, although the routine copying and editing work was now done by an assistant, Sophie Grandchamp. Madame Roland wrote most of her husbands official letters and regretted that she could not go to the new National Assembly herself to argue the case of Lyon: women were admitted only to the public gallery. When she observed the debates from the gallery, it annoyed her that the conservatives were so much better and more eloquent in the debates than the revolutionaries, who she considered ideologically superior. Outside the assembly she was active as a lobbyist. With Roland, she was a regular visitor at the

In the months immediately after her arrival in Paris, Madame Roland was not satisfied with the progress of social and political change in France, which she felt to be not fast and far-reaching enough. When King

In the months immediately after her arrival in Paris, Madame Roland was not satisfied with the progress of social and political change in France, which she felt to be not fast and far-reaching enough. When King

For her part, Madame Roland had no sympathy for 'hooligans' like the Jacobins and the Montagnards. Although in letters written during the early days of the revolution she had found the use of violence acceptable, she had a great aversion to brutal and uncivilized behavior. She also resented the uncouth Jacobin foreman Georges Danton, and did not respond to his overtures to cooperate with her. Some historians argue that her refusal to enter into an alliance with Danton ultimately contributed to the fall of the Girondins.

When on 6 and 7 September, hundreds of prisoners were massacred in Parisian prisons because they were suspected of anti-revolutionary sympathies, Madame Roland wrote to a friend that she was beginning to feel ashamed of the revolution. Determining who was responsible for this slaughter became another point of contention between the various factions. Madame Roland - and most of the other Girondins - pointed to Marat, Danton and Robespierre as the instigators of the violence. Political opponents of the Rolands pointed out that 'their' Ministry of the Interior was responsible for the prisons and had taken very little action to prevent or stop the violence.

During Roland's second term of office, Madame Roland again occupied an important position. It was common knowledge that she wrote most of her husband's political texts and that he fully relied on her judgment and ideas; both Danton and Marat publicly mocked him for it. She had her own office in the ministry and directed the work of the Bureau d'esprit public (the public opinion office), which aimed to spread the revolutionary ideals among the population. Opponents of the Rolands accused them of using the Office to issue state propaganda in support of the Girondine cause. Although there is no evidence that the Rolands were appropriating public money, it is certain that they were involved in attempts to blacken their political opponents. At least one of the secret agents run by the ministry reported directly to Madame Roland.

The private life of Madame Roland was turbulent during this period. A passionate but in her own words platonic romance had developed between her and the Girondin deputy

For her part, Madame Roland had no sympathy for 'hooligans' like the Jacobins and the Montagnards. Although in letters written during the early days of the revolution she had found the use of violence acceptable, she had a great aversion to brutal and uncivilized behavior. She also resented the uncouth Jacobin foreman Georges Danton, and did not respond to his overtures to cooperate with her. Some historians argue that her refusal to enter into an alliance with Danton ultimately contributed to the fall of the Girondins.

When on 6 and 7 September, hundreds of prisoners were massacred in Parisian prisons because they were suspected of anti-revolutionary sympathies, Madame Roland wrote to a friend that she was beginning to feel ashamed of the revolution. Determining who was responsible for this slaughter became another point of contention between the various factions. Madame Roland - and most of the other Girondins - pointed to Marat, Danton and Robespierre as the instigators of the violence. Political opponents of the Rolands pointed out that 'their' Ministry of the Interior was responsible for the prisons and had taken very little action to prevent or stop the violence.

During Roland's second term of office, Madame Roland again occupied an important position. It was common knowledge that she wrote most of her husband's political texts and that he fully relied on her judgment and ideas; both Danton and Marat publicly mocked him for it. She had her own office in the ministry and directed the work of the Bureau d'esprit public (the public opinion office), which aimed to spread the revolutionary ideals among the population. Opponents of the Rolands accused them of using the Office to issue state propaganda in support of the Girondine cause. Although there is no evidence that the Rolands were appropriating public money, it is certain that they were involved in attempts to blacken their political opponents. At least one of the secret agents run by the ministry reported directly to Madame Roland.

The private life of Madame Roland was turbulent during this period. A passionate but in her own words platonic romance had developed between her and the Girondin deputy

File:Jean-Paul Marat portre.jpg, Marat

File:Jacques René Hébert.JPG,

In December 1792, Madame Roland had to appear before the

On 24 June she was released unexpectedly because the legal basis for her arrest had been flawed, but was rearrested on a new

On 24 June she was released unexpectedly because the legal basis for her arrest had been flawed, but was rearrested on a new

On October 31, 1793, twenty-one Girondin politicians were executed after a short trial; most of them were known to Madame Roland and the group included her good friend Brissot.It is not clear whether Madame Roland was called as a witness during the trial against the Girondins. She was present in the building where the trial took place. However, the judge ruled at a certain point that the case had been going on long enough "because the accused had already been found guilty by the people." The next day she was transferred to the

On October 31, 1793, twenty-one Girondin politicians were executed after a short trial; most of them were known to Madame Roland and the group included her good friend Brissot.It is not clear whether Madame Roland was called as a witness during the trial against the Girondins. She was present in the building where the trial took place. However, the judge ruled at a certain point that the case had been going on long enough "because the accused had already been found guilty by the people." The next day she was transferred to the

Particularly in the ''Mémoires historiques'' she goes to a lot of effort to show that she had been "just the wife" and had always behaved in a way that was considered appropriate for a woman of her time. She is indignant that the Jacobin press compared her to the influential noble women from the ancien regime. At the same time, through her description of events she shows - consciously or unconsciously - how big her influence was within the Girondin circle, and how fundamentally important her contribution to Roland's ministry. She provides a fairly reliable and accurate account of events, although she sometimes leaves out things that do not show her in the most favourable light. She was certainly not neutral in her description of people she did not like.

In the ''Mémoires particuliers'' she reports on her personal life in a way that was unusual for a woman of that time. She speaks of a sexual assault by a pupil of her father, her experiences during her wedding night and her problems with breastfeeding. In this she followed

Particularly in the ''Mémoires historiques'' she goes to a lot of effort to show that she had been "just the wife" and had always behaved in a way that was considered appropriate for a woman of her time. She is indignant that the Jacobin press compared her to the influential noble women from the ancien regime. At the same time, through her description of events she shows - consciously or unconsciously - how big her influence was within the Girondin circle, and how fundamentally important her contribution to Roland's ministry. She provides a fairly reliable and accurate account of events, although she sometimes leaves out things that do not show her in the most favourable light. She was certainly not neutral in her description of people she did not like.

In the ''Mémoires particuliers'' she reports on her personal life in a way that was unusual for a woman of that time. She speaks of a sexual assault by a pupil of her father, her experiences during her wedding night and her problems with breastfeeding. In this she followed

In the second half of the nineteenth century the first

In the second half of the nineteenth century the first

File:Etienne Charles Leguay - Buzot contemplating portrait of Madame Roland.jpg, Buzot contemplating a miniature portrait of Madame Roland, by Etienne Charles Leguay

File:François Masson - Portrait of Madame Roland, bust.jpg, Bust of Madame Roland by François Masson (1745–1807)

File:Le dernier Jour de Madame Roland, - Jules-Adolphe Goupil, 1880.jpg, Jules-Adolphe Goupil (1839–1883) Madame Roland's final day. 1880

File:DPJ 35-edit-a-thon Donner des Elles à l'UM - Madame Roland.jpg, Bust of Madame Roland in

Part 1Part 2

* ''Lettres de Madame Roland: 1767–1780''. (1913–1915)

Part 1Part 2

* ''Mémoires de madame Roland''. (1905)

Part 1Part 2

(Complete text) * The private memoirs of Madame Roland. 1901. (English translation of edited text)

''Life of Madame Roland''

Londen: Hutchinson & Co., 1911 {{DEFAULTSORT:Roland, Madame 1754 births 1793 deaths French people executed by guillotine during the French Revolution French salon-holders Executed French women 18th-century French women writers 18th-century French writers French women memoirists 18th-century letter writers 18th-century French memoirists Women in the French Revolution Girondins

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, March 17, 1754 – Paris, November 8, 1793), born Marie-Jeanne Phlipon, and best known under the name Madame Roland, was a French revolutionary, salonnière

A salon is a gathering of people held by an inspiring host. During the gathering they amuse one another and increase their knowledge through conversation. These gatherings often consciously followed Horace's definition of the aims of poetry, "ei ...

and writer.

Initially she led a quiet and unremarkable life as a provincial intellectual with her husband, the economist Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière

Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière (18 February 1734 – 10 November 1793) was a French inspector of manufactures in Lyon and became a leader of the Girondist faction in the French Revolution, largely influenced in this direction by his wife, Mar ...

. She became interested in politics only when the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

broke out in 1789. She spent the first years of the revolution in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

, where her husband was elected to the city council. During this period she developed a network of contacts with politicians and journalists; her reports on developments in Lyon were published in national revolutionary newspapers.

In 1791 the couple settled in Paris, where Madame Roland soon established herself as a leading figure within the political group the Girondins

The Girondins ( , ), or Girondists, were members of a loosely knit political faction during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnard ...

, one of the more moderate revolutionary factions. She was known for her intelligence, astute political analyses and her tenacity, and was a good lobbyist and negotiator. The salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon ( ...

she hosted in her home several times a week was an important meeting place for politicians. However, she was also convinced of her own intellectual and moral superiority and alienated important political leaders like Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

and Danton

Georges Jacques Danton (; 26 October 1759 – 5 April 1794) was a French lawyer and a leading figure in the French Revolution. He became a deputy to the Paris Commune, presided in the Cordeliers district, and visited the Jacobin club. In August ...

.

Unlike the feminist revolutionaries Olympe de Gouges

Olympe de Gouges (; born Marie Gouze; 7 May 17483 November 1793) was a French playwright and political activist whose writings on women's rights and abolitionism reached a large audience in various countries. She began her career as a playwright ...

and Etta Palm, Madame Roland was not an advocate for political rights for women. She believed that women should play a very modest role in public and political life. Already during her lifetime, many found this difficult to reconcile with her own active involvement in politics and her important role within the Girondins.

When her husband unexpectedly became Minister of the Interior in 1792, her political influence grew. She had control over the content of ministerial letters, memorandums and speeches, was involved in decisions about political appointments, and was in charge of a bureau set up to influence public opinion in France. She was both admired and reviled, and particularly hated by the sans-culottes

The (, 'without breeches') were the common people of the lower classes in late 18th-century France, a great many of whom became radical and militant partisans of the French Revolution in response to their poor quality of life under the . T ...

of Paris. The publicists Marat and Hébert

Hébert or Hebert may refer to:

People Surname

* Anne Hébert, Canadian author and poet

* Ashley Hebert, subject of ''The Bachelorette'' (season 7)

* Bobby Hebert, National Football League player

* Chantal Hébert, Canadian political commentato ...

conducted a smear campaign against Madame Roland as part of the power struggle between the Girondins and the more radical Jacobin

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = P ...

s and Montagnards

Montagnard (''of the mountain'' or ''mountain dweller'') may refer to:

*Montagnard (French Revolution), members of The Mountain (''La Montagne''), a political group during the French Revolution (1790s)

** Montagnard (1848 revolution), members of th ...

. In June 1793, she was the first Girondin to be arrested during the Terror and was guillotine

A guillotine is an apparatus designed for efficiently carrying out executions by beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secured with stocks at t ...

d a few months later.

Madame Roland wrote her memoirs while she was imprisoned in the months before her execution. They are – like her letters – a valuable source of information about the first years of the French Revolution.

Early years

Childhood

Marie-Jeanne Phlipon, known as Manon,According to some sources - and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France - her first name was Jeanne-Marie. The biographies written about her give Marie-Jeanne a first name. was the daughter of Pierre Gatien Phlipon, an engraver, and his wife Marguerite Bimont, daughter of a

Marie-Jeanne Phlipon, known as Manon,According to some sources - and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France - her first name was Jeanne-Marie. The biographies written about her give Marie-Jeanne a first name. was the daughter of Pierre Gatien Phlipon, an engraver, and his wife Marguerite Bimont, daughter of a haberdasher

In British English, a haberdasher is a business or person who sells small articles for sewing, dressmaking and knitting, such as buttons, ribbons, and zippers; in the United States, the term refers instead to a retailer who sells men's clothi ...

. Her father ran a successful business and the family lived in reasonable prosperity on the Quai de l'Horloge in Paris. She was the couple's only surviving child; six siblings died in infancy. The first two years of her life she lived with a wet nurse

A wet nurse is a woman who breastfeeds and cares for another's child. Wet nurses are employed if the mother dies, or if she is unable or chooses not to nurse the child herself. Wet-nursed children may be known as "milk-siblings", and in some cu ...

in Arpajon, a small town south-east of Paris.

Manon taught herself to read as a five-year-old and during the catechism

A catechism (; from grc, κατηχέω, "to teach orally") is a summary or exposition of doctrine and serves as a learning introduction to the Sacraments traditionally used in catechesis, or Christian religious teaching of children and adul ...

lessons, the local priests also noticed she was very intelligent. Therefore, and because she was an only child, she received more education than was customary for a girl from her social background at that time; however, it still fell short of the level of schooling a boy would have received. Teachers came to the family home for subjects such as calligraphy

Calligraphy (from el, link=y, καλλιγραφία) is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instrument. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined ...

, history, geography and music. Her father taught her drawing and art history, an uncle who was a priest gave her some Latin lessons and her grandmother, who had been a governess, took care of spelling and grammar. In addition, she learned from her mother how to run a household.

As a child, she was very religious. At her own request, she lived in a convent for a year to prepare herself for her first communion

First Communion is a ceremony in some Christian traditions during which a person of the church first receives the Eucharist. It is most common in many parts of the Latin Church tradition of the Catholic Church, Lutheran Church and Anglican Commun ...

when she was eleven. Only a few years later she would begin to question the doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. Although she eventually turned away from the church, she continued to believe all her life in the existence of God, the immortality of the soul, and the moral obligation to do good. Her ideas are very close to deism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin ''deus'', meaning " god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation o ...

.

Studying and writing

After returning home from the convent, she received little additional formal education but continued to read and study; she was largely anautodidact

Autodidacticism (also autodidactism) or self-education (also self-learning and self-teaching) is education without the guidance of masters (such as teachers and professors) or institutions (such as schools). Generally, autodidacts are individu ...

. She read books on all subjects: history, mathematics, agriculture and law. She developed a passion for the classics; like many of her contemporaries, she was inspired by the biographies of famous Greeks and Romans in Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

's ''Vitae Parallelae (Parallel Lives

Plutarch's ''Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans'', commonly called ''Parallel Lives'' or ''Plutarch's Lives'', is a series of 48 biographies of famous men, arranged in pairs to illuminate their common moral virtues or failings, probably writt ...

''.

Manon Phlipon's ideas on social relations in France were shaped, among other things, by a visit to acquaintances of her grandmother at the court of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

. She was not impressed by the self-serving behavior of the aristocrats she met. She found it remarkable that people were given privileges because of their family of birth rather than on merit. She immersed herself in philosophy, particularly in the works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

; his democratic ideas strongly influenced her thinking about politics and social justice. Rousseau was also very important to her in other areas. She later said that his books had shown her how to lead a happy and fulfilled life. Throughout her life she would regularly reread Rousseau's ''Julie, ou La Nouvelle Héloïse

''Julie; or, The New Heloise'' (french: Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse), originally entitled ''Lettres de Deux Amans, Habitans d'une petite Ville au pied des Alpes'' ("Letters from two lovers, living in a small town at the foot of the Alps"), is ...

'', and use it as a source of inspiration.

She was dissatisfied with the opportunities available to her as a woman and wrote to friends that she would have preferred to have lived in Roman times. For a while, she seriously considered taking over her father's business. She corresponded with a number of erudite older men - mainly clients of her father's - who acted as intellectual mentors. She started writing philosophical essays herself which she circulated in manuscript among her friends under the title ''Oeuvre des loisirs'' ('work for relaxation'). In 1777 she took part in an essay

An essay is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a letter, a paper, an article, a pamphlet, and a short story. Essays have been sub-classified as formal a ...

competition on the theme 'How the education of women can help make men better.' Her essay did not receive a prize.

Before the revolution

Marriage

In the social milieu of the Phlipons, marriages were usually arranged; it was unusual for a young woman like Manon Phlipon, the only child of fairly prosperous parents, not to be married by the age of twenty. She received at least ten proposals of marriage, but rejected all of them. She had a brief romance with the writer Pahin de la Blancherie, which for her ended in a painful disappointment. A friend of her father, a widower of 56 with whom she corresponded about philosophical issues, asked her to come and live with him on his estate so that they could study philosophy together. She hinted to him that she might consider a platonic marriage, but nothing of the sort came about. In 1776, Manon Phlipon met

In 1776, Manon Phlipon met Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière

Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière (18 February 1734 – 10 November 1793) was a French inspector of manufactures in Lyon and became a leader of the Girondist faction in the French Revolution, largely influenced in this direction by his wife, Mar ...

, who was twenty years her senior.The family name was originally only 'Roland'. An ancestor had added 'de la Platière' as a reference to an estate owned by the family. Jean-Marie Roland used the noble-sounding version during the ancien régime, but abandoned it when noble titles were abolished during the revolution. (Reynolds, p.33) He was Inspector de Manufactures in Picardy

Picardy (; Picard and french: Picardie, , ) is a historical territory and a former administrative region of France. Since 1 January 2016, it has been part of the new region of Hauts-de-France. It is located in the northern part of France.

Hist ...

and as such charged with quality control of the products of local manufacturers and craftsmen. He was an expert in the field of production, trade and economic policy, especially of the textile industry

The textile industry is primarily concerned with the design, production and distribution of yarn, textile, cloth and clothing. The raw material may be Natural material, natural, or synthetic using products of the chemical industry.

Industry p ...

. He was intelligent, well-read and well-traveled, but he was also known as a difficult human being: reluctant to take into consideration any opinions but his own and easily irritated. Because of this, he often did not succeed in implementing the economic reforms he favoured, and his career was not as successful as he believed he deserved.

The Roland family had once belonged to the lower nobility, but by the end of the 18th century no longer held a title. There was a clear difference in social status compared to Manon Phlipon's family of artisans and shopkeepers. This was her reason for refusing Roland's first marriage proposal in 1778. A year later she did accept. The wedding plans were initially kept secret because Roland expected objections from his family. By the standards of that time, this was a 'mesalliance

Hypergamy (colloquially referred to as "marrying up") is a term used in social science for the act or practice of a person marrying a spouse of higher caste or social status than themselves.

The antonym "hypogamy" refers to the inverse: marr ...

': a marriage considered inappropriate due to the large difference in social status between the spouses.

They were married in February 1780 and initially lived in Paris, where Roland worked at the Ministry of the Interior. From the very first, Madame Roland helped her husband in his work, acting more or less as his secretary. In her spare time she attended lectures on natural history in the Jardin des Plantes, the botanical garden

A botanical garden or botanic gardenThe terms ''botanic'' and ''botanical'' and ''garden'' or ''gardens'' are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word ''botanic'' is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens, an ...

of Paris. Here she met Louis-Augustin Bosc d'Antic, a natural historian who remained a close friend until her death. Her friendship with François Xavier Lanthenas, later a parliamentarian, also dates from this time.

Amiens and Lyon

After a year in Paris the couple moved toAmiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

. Their only child Eudora was born there in 1781. Unusual for that time - but entirely in line with Rousseau's theories - Madame Roland breastfed her daughter herself instead of hiring a wet nurse. She wrote a particularly detailed and candid report of the birth and the problems with breastfeeding, and is one of the first women of this time to write openly about such matters. The report was published after her death.

The couple lived a very quiet life in Amiens and had few social contacts. In Paris, Madame Roland had already supported her husband in his work and their cooperation now developed further. At first she was mainly involved in copying texts and assisting his research; her role was clearly subordinate. In her memoirs she looks back on this situation with some resentment, but her letters from that period do not show that she objected at the time. Her involvement gradually increased; she began to edit and modify text, and eventually wrote major sections herself. Her husband apparently initially did not realize that some texts were hers and not his own. Within a few years, she developed into the better writer, which was also acknowledged by Jean-Marie Roland. In the end he fully accepted her as his intellectual equal and there was an equal partnership.

In 1784, Madame Roland visited Paris for a few weeks to acquire a peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted noble ranks.

Peerages include:

Australia

* Australian peers

Belgium

* Be ...

for her husband. The financial privileges associated with a title would allow him to give up his job as an inspector and focus entirely on writing and research. She discovered that she had a talent for lobbying and negotiating. The peerage did not materialise: in the course of his professional life her husband had too often antagonised his superiors. She did manage to obtain an appointment for him in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

that was less demanding than his post in Amiens and better paid. Before the move to Lyon, the couple visited England, where Madame Roland attended a debate in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

between the legendary political opponents William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ir ...

and Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled '' The Honourable'' from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was the arch-ri ...

.

Although Lyon was Roland's official place of work the family usually lived in Villefranche-sur-Saône, about thirty kilometers north of Lyon. Madame Roland focused on the education of her daughter Eudora, who to her great disappointment turned out to be less interested in books and acquiring knowledge than she herself had been at that age. In the following years, she would occasionally in letters to friends (and in her memoirs) continue to call her daughter ’slow’ and lament that her child had such bad taste. Together with her husband she worked on the Encyclopédie méthodique - Dictionnaire des Arts and Métiers, a sequel to the Encyclopédie

''Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers'' (English: ''Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts''), better known as ''Encyclopédie'', was a general encyclopedia publis ...

of Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the '' Encyclopédie'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promi ...

and D'Alembert

Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert (; ; 16 November 1717 – 29 October 1783) was a French mathematician, mechanician, physicist, philosopher, and music theorist. Until 1759 he was, together with Denis Diderot, a co-editor of the '' Encyclopé ...

, which focussed on trade and industry. In 1787 the couple made a trip to Switzerland, where, at the request of Madame Roland, they also visited sites that had played a role in the life of Rousseau.

The Revolution

From a distance: 1789–1791

Throughout France, and especially in Paris, protests against the social, economic and political conditions were mounting. The Rolands were in many ways representative of the rising revolutionary elite. They had obtained their social position through work and not through birth, and resented the court in Versailles with its corruption and privileges. They deliberately chose a fairly sober, puritan lifestyle. They favoured a liberal economy and the abolition of old regulations, and advocated relief for the poor. When the French States General were convened in 1789, Madame Roland and her husband were involved in drawing up the local '' Cahier de Doléances'', the document in which the citizens of Lyon could express their grievances about the political and economic system. Politics had played no major role in Madame Roland's correspondence before 1789, but in the course of that year she became more and more fascinated by political developments. After thestorming of the Bastille

The Storming of the Bastille (french: Prise de la Bastille ) occurred in Paris, France, on 14 July 1789, when revolutionary insurgents stormed and seized control of the medieval armoury, fortress, and political prison known as the Bastille. At ...

on July 14, 1789, her thinking radicalised quickly and there was a complete change in the tone and content of her letters. She was no longer interested in societal reform, but advocated revolution. Institutions from the old regime were no longer acceptable to her; now that the people had taken over sovereignty, a completely new form of government had to be developed. Unlike many other revolutionaries, she was quick to argue for the establishment of a republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

. In her political thinking, Madame Roland was irreconcilably radical at this point in time. She was not inclined to compromise on anything; to achieve her revolutionary ideals she found the use of force, and even civil war, acceptable.

During the first eighteen months of the French Revolution the Rolands were based in Lyon, although they still lived in Villefranche part of the time. Madame Roland soon became convinced that a counter-revolution was being plotted. She tried to mobilize her friends through her letters, not hesitating to spread unfounded rumors about events and about people she did not agree with. Meanwhile, it had become common knowledge in Lyon that the Rolands sympathized with the revolutionaries and had supported the establishment of radical political clubs. They were hated by representatives of the old elite because of this. She was happy when, on February 7, 1790, an uprising broke out in Lyon that led to the ousting of the city council and an increase of the number of men eligible to vote.

Madame Roland did not publicly take part in political discussions, but still managed to gain political influence during this period. She corresponded with a network of publicists and politicians, including the Parisian journalist Jacques Pierre Brissot

Jacques Pierre Brissot (, 15 January 1754 – 31 October 1793), who assumed the name of de Warville (an English version of "d'Ouarville", a hamlet in the village of Lèves where his father owned property), was a leading member of the Girondins du ...

, the future leader of the Girondins

The Girondins ( , ), or Girondists, were members of a loosely knit political faction during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnard ...

, and the lawyer Jean-Henri Bancal d'Issarts. In her letters she described and analyzed the developments in Lyon. At least on five occasions Brissot published excerpts from her letters as articles in his newspaper '' Le Patriote Francaise'', so that her opinions were discussed outside Lyon. Luc-Antoine de Champagneux did the same in his newspaper '' Le courier de Lyon''. She was one of the few female correspondents in the revolutionary press. Because her contributions were not published under her own name, but anonymously or as 'a woman from the south,' it is impossible to determine with certainty how many articles written by Madame Roland appeared in the press.

Activist and salonniere

In 1790 Jean-Marie Roland was elected in the city council of Lyon where he advocated a moderate revolutionary administration. The Rolands now settled in Lyons but in order to get money for the revolutionary reform they left for Paris in 1791, for what should have been a short stay. Madame Roland soon became a well-known figure in political circles in Paris, especially thanks to Brissot, who introduced her everywhere. As always, she worked alongside her husband, although the routine copying and editing work was now done by an assistant, Sophie Grandchamp. Madame Roland wrote most of her husbands official letters and regretted that she could not go to the new National Assembly herself to argue the case of Lyon: women were admitted only to the public gallery. When she observed the debates from the gallery, it annoyed her that the conservatives were so much better and more eloquent in the debates than the revolutionaries, who she considered ideologically superior. Outside the assembly she was active as a lobbyist. With Roland, she was a regular visitor at the

Madame Roland soon became a well-known figure in political circles in Paris, especially thanks to Brissot, who introduced her everywhere. As always, she worked alongside her husband, although the routine copying and editing work was now done by an assistant, Sophie Grandchamp. Madame Roland wrote most of her husbands official letters and regretted that she could not go to the new National Assembly herself to argue the case of Lyon: women were admitted only to the public gallery. When she observed the debates from the gallery, it annoyed her that the conservatives were so much better and more eloquent in the debates than the revolutionaries, who she considered ideologically superior. Outside the assembly she was active as a lobbyist. With Roland, she was a regular visitor at the Jacobin club

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = P ...

(here too women were only allowed access to the public gallery).

From April 1791 she hosted a salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon ( ...

in her home several times a week, attended by republicans from bourgeois circles. Among the visitors were Maximilien de Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Estat ...

and the American revolutionary Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

.

During these events, Madame Roland always sat at a table by the window, reading, writing letters or doing needlework

Needlework is decorative sewing and textile arts handicrafts. Anything that uses a needle for construction can be called needlework. Needlework may include related textile crafts such as crochet, worked with a hook, or tatting, worked wi ...

. She never involved herself in the conversations going on around her but listened carefully. Her considerable political influence was not exerted by participating in public debate (which she found unseemly for a woman), but through letters and personal conversations. She was known for her sharp political analyses and her ideological tenacity, and was widely recognized as one of the most important people in the group around Brissot. She was always asked for advice on political strategy and she contributed to the content of letters, parliamentary bills and speeches. She was described by contemporaries as a charming woman and a brilliant conversationalist.

Madame Roland's salon is one of the main reasons why she is remembered but it may not have been a salon in the usual sense of the term. The gatherings she hosted were strictly political and not social in character; hardly any food or drink was served. They took place in the few hours between the end of the debates in the assembly and the beginning of the meetings in the Jacobin Club. There were also - apart from Madame Roland herself- no women present. This distinguished them from the events hosted by Louise de Kéralio, Sophie de Condorcet

Sophie de Condorcet (1764 in Meulan – 8 September 1822 in Paris), also known as Sophie de Grouchy and best known as Madame de Condorcet, was a prominent French salon hostess from 1789 to the Reign of Terror, and again from 1799 until her death i ...

and Madame de Staël; although also attended by revolutionaries their gatherings were more like the aristocratic salons of the ancien regime, an impression that Madame Roland wanted to avoid at any cost.

Political ideas

The name of Madame Roland is inextricably linked to theGirondins

The Girondins ( , ), or Girondists, were members of a loosely knit political faction during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnard ...

. Both she and her husband were considered to be part of the leadership of this political faction, also called the Brissotins after their leader Jacques Pierre Brissot. Originally, the Girondins - and also the Rolands - were part of the wider Jacobin

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = P ...

movement. As the revolution progressed, they began to distance themselves from the Jacobins, who became dominated by radical Parisian leaders like Georges Danton

Georges Jacques Danton (; 26 October 1759 – 5 April 1794) was a French lawyer and a leading figure in the French Revolution. He became a deputy to the Paris Commune, presided in the Cordeliers district, and visited the Jacobin club. In Augu ...

and Jean-Paul Marat

Jean-Paul Marat (; born Mara; 24 May 1743 – 13 July 1793) was a French political theorist, physician, and scientist. A journalist and politician during the French Revolution, he was a vigorous defender of the '' sans-culottes'', a radica ...

. The Girondins opposed the influence Paris had on national politics in preference to federalism; many of the Girondins politicians came from outside the capital. They belonged to the bourgeoisie and positioned themselves as the guardians of the rule of law against the lawlessness of the masses. In this aspect too they differed fundamentally from the Jacobins, who saw themselves as the representatives of the sans-culottes

The (, 'without breeches') were the common people of the lower classes in late 18th-century France, a great many of whom became radical and militant partisans of the French Revolution in response to their poor quality of life under the . T ...

, the workers, and shopkeepers.

In power: the Ministry of the Interior

Revolution gathering speed

In the months immediately after her arrival in Paris, Madame Roland was not satisfied with the progress of social and political change in France, which she felt to be not fast and far-reaching enough. When King

In the months immediately after her arrival in Paris, Madame Roland was not satisfied with the progress of social and political change in France, which she felt to be not fast and far-reaching enough. When King Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

tried to flee the country with his family in June 1791, the revolution gained momentum. Madame Roland herself took to the streets to lobby for the introduction of a republic; she also became a member of a political club under her own name for the first time, despite her conviction that women should not have a role in public life.The society she joined would have been either the Societé fraternelle des deux sexes or the Societé fraternelle des amies de la vérité. (Reynolds, p 146) She felt that at that point in time there was so much at stake that everyone - man or woman - had to fully exert themselves to bring about change. In July of that year, a demonstration on the Champs de Mars led to a massacre

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

: the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

opened fire on demonstrators, killing possibly as many as 50 people. Many prominent revolutionaries feared for their lives and fled; the Rolands provided a temporary hiding place for Louise de Kéralio and her husband François Robert.

Soon divisions began to occur within the revolutionaries in the legislative assembly, particularly as to whether France should start a war against Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

. Brissot and most of the Girondins were in favour (they feared military support for the monarchy from Prussia and Austria), while Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

first wanted to put internal affairs in order. The political situation was so divided that it was next to impossible to form a stable government: there were no ministerial candidates that were acceptable to all parties (including the king and the court). The Girodins were given the opportunity to put their ideas into practice: King Louis XVI asked them to appoint three ministers. In March 1792 Roland was appointed Minister of the Interior. This appointment came so unexpectedly that the Rolands at first thought Brissot was joking. There is no indication that they were actively seeking a government post for Roland.In 1790 - 1792, the Rolands were exploring the idea to set up a community of friends living according to the ideal of the Revolution in a rural area in France, or possibly in America. This plan, which involved Brissot, Bancal d'Issarts and Lanthenas, is frequently mentioned in their letters; they did not discuss a political appointment. The couple moved into the Hôtel Pontchartran, the official residence of the minister, but kept on their small apartment in the city - just in case.

First term of office

The office of Minister of the Interior was difficult and the work load was extremely heavy. The ministry was responsible for elections, education, agriculture, industry, commerce, roads, public order, poor relief and the working of government. Madame Roland remained the driving force behind her husband's work. She commented on all documents, wrote letters and memorandums, and had a major say in appointments, for example that of Joseph Servan de Gerbey as minister of war. She was, as always, very firm in her views and convinced of her own infallibility. In April 1792, thewar

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

so fervently desired by the Girondins broke out. Madame Roland wrote a reproachful letter to Robespierre because he still opposed the idea. This led to the end of the friendly relations between Robespierre and the Rolands; eventually he would become a sworn enemy of the Girondins and of Madame Roland.

Madame Roland was able to convince her husband and the other ministers that the king was plotting to restore the ancien regime. It was her idea to establish an army camp near Paris with 20,000 soldiers from all over France; these should intervene in the event of a possible counter-revolution in the capital. When Louis XVI hesitated to sign this into law, Roland sent him a disrespectful protest letter and published it before the king could respond. Madame Roland is rather vague in her memoirs as to whether she was merely involved in editing the letter, or whether she wrote the whole text. The latter is considered most likely by her biographers. In any case, it was her idea to publish the letter to get more support in the assembly and in the population.

On June 10, 1792, Louis XVI sacked Jean-Marie Roland and the two other Girondin ministers. After this, radical Jacobins and Montagnards

Montagnard (''of the mountain'' or ''mountain dweller'') may refer to:

*Montagnard (French Revolution), members of The Mountain (''La Montagne''), a political group during the French Revolution (1790s)

** Montagnard (1848 revolution), members of th ...

took the political initiative, which eventually led to the end of the monarchy on 10 August. Roland was then reappointed as minister.

Second term of office

The king's fall heralded the start of the Terror, a period in which radical groups with great bloodshed got rid of their opponents. In radical circles the position of the Rolands was controversial. The Jacobins, the Montagnards and theParis Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defende ...

viewed them with suspicion: that Roland had served as minister under Louis XVI was seen as collaborating with the ancien regime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word fo ...

. His dismissal by the king had only led to a temporary restoration of their reputation.

For her part, Madame Roland had no sympathy for 'hooligans' like the Jacobins and the Montagnards. Although in letters written during the early days of the revolution she had found the use of violence acceptable, she had a great aversion to brutal and uncivilized behavior. She also resented the uncouth Jacobin foreman Georges Danton, and did not respond to his overtures to cooperate with her. Some historians argue that her refusal to enter into an alliance with Danton ultimately contributed to the fall of the Girondins.

When on 6 and 7 September, hundreds of prisoners were massacred in Parisian prisons because they were suspected of anti-revolutionary sympathies, Madame Roland wrote to a friend that she was beginning to feel ashamed of the revolution. Determining who was responsible for this slaughter became another point of contention between the various factions. Madame Roland - and most of the other Girondins - pointed to Marat, Danton and Robespierre as the instigators of the violence. Political opponents of the Rolands pointed out that 'their' Ministry of the Interior was responsible for the prisons and had taken very little action to prevent or stop the violence.

During Roland's second term of office, Madame Roland again occupied an important position. It was common knowledge that she wrote most of her husband's political texts and that he fully relied on her judgment and ideas; both Danton and Marat publicly mocked him for it. She had her own office in the ministry and directed the work of the Bureau d'esprit public (the public opinion office), which aimed to spread the revolutionary ideals among the population. Opponents of the Rolands accused them of using the Office to issue state propaganda in support of the Girondine cause. Although there is no evidence that the Rolands were appropriating public money, it is certain that they were involved in attempts to blacken their political opponents. At least one of the secret agents run by the ministry reported directly to Madame Roland.

The private life of Madame Roland was turbulent during this period. A passionate but in her own words platonic romance had developed between her and the Girondin deputy

For her part, Madame Roland had no sympathy for 'hooligans' like the Jacobins and the Montagnards. Although in letters written during the early days of the revolution she had found the use of violence acceptable, she had a great aversion to brutal and uncivilized behavior. She also resented the uncouth Jacobin foreman Georges Danton, and did not respond to his overtures to cooperate with her. Some historians argue that her refusal to enter into an alliance with Danton ultimately contributed to the fall of the Girondins.

When on 6 and 7 September, hundreds of prisoners were massacred in Parisian prisons because they were suspected of anti-revolutionary sympathies, Madame Roland wrote to a friend that she was beginning to feel ashamed of the revolution. Determining who was responsible for this slaughter became another point of contention between the various factions. Madame Roland - and most of the other Girondins - pointed to Marat, Danton and Robespierre as the instigators of the violence. Political opponents of the Rolands pointed out that 'their' Ministry of the Interior was responsible for the prisons and had taken very little action to prevent or stop the violence.

During Roland's second term of office, Madame Roland again occupied an important position. It was common knowledge that she wrote most of her husband's political texts and that he fully relied on her judgment and ideas; both Danton and Marat publicly mocked him for it. She had her own office in the ministry and directed the work of the Bureau d'esprit public (the public opinion office), which aimed to spread the revolutionary ideals among the population. Opponents of the Rolands accused them of using the Office to issue state propaganda in support of the Girondine cause. Although there is no evidence that the Rolands were appropriating public money, it is certain that they were involved in attempts to blacken their political opponents. At least one of the secret agents run by the ministry reported directly to Madame Roland.

The private life of Madame Roland was turbulent during this period. A passionate but in her own words platonic romance had developed between her and the Girondin deputy François Buzot

François Nicolas Léonard Buzot (1 March 176018 June 1794) was a French politician and leader of the French Revolution.

Biography

Early life

Born at Évreux, Eure, he studied Law, and, at the outbreak of the Revolution was a lawyer in his hom ...

, who she had first met as a visitor to her salon. This affected her relationship with her husband, who found the idea that his wife was in love with another man hard to bear. The romance with Buzot was possibly also one of the factors contributing to the break with a political ally; her old friend Lanthenas, now a parliamentarian, had for years been in love with her himself, and now distanced himself from the circle around Madame Roland - and from the Girondins.

Downfall

Fall of the Girondins

Radical newspapers and pamphlets began to spread more and more rumors about anti-revolutionary conspiracies that supposedly were forged at the Rolands' home. The rather sober dinners that Madame Roland gave twice a week (successors of the 'salon' she hosted before Jean-Marie Roland became minister) were depicted as decadent events where politicians were seduced to join the 'Roland clique'. Jean-Paul Marat, Jacques-René Hébert andCamille Desmoulins

Lucie-Simplice-Camille-Benoît Desmoulins (; 2 March 17605 April 1794) was a French journalist and politician who played an important role in the French Revolution. Desmoulins was tried and executed alongside Georges Danton when the Committee ...

depicted Madame Roland as a manipulative courtesan

Courtesan, in modern usage, is a euphemism for a "kept" mistress or prostitute, particularly one with wealthy, powerful, or influential clients. The term historically referred to a courtier, a person who attended the court of a monarch or othe ...

who deceived the virtuous Roland; in their articles and pamphlets they compared her to Madame Du Barry

Jeanne Bécu, Comtesse du Barry (19 August 1743 – 8 December 1793) was the last '' maîtresse-en-titre'' of King Louis XV of France. She was executed, by guillotine, during the French Revolution due to accounts of treason—particularly bei ...

and Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

. Although Danton and Robespierre also attacked her in their writings, they presented her as a dangerous political opponent and not as a wicked female.Hébert

Hébert or Hebert may refer to:

People Surname

* Anne Hébert, Canadian author and poet

* Ashley Hebert, subject of ''The Bachelorette'' (season 7)

* Bobby Hebert, National Football League player

* Chantal Hébert, Canadian political commentato ...

File:Rouillard - Camille Desmoulins.jpg, Desmoulins

File:Georges Danton.jpg, Danton

Georges Jacques Danton (; 26 October 1759 – 5 April 1794) was a French lawyer and a leading figure in the French Revolution. He became a deputy to the Paris Commune, presided in the Cordeliers district, and visited the Jacobin club. In August ...

File:Robespierre.jpg, Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year Nation ...

(the new Legislative Assembly) on charges of corresponding with aristocrats who had fled to England. She defended herself so well that the deputies applauded - the public gallery remained silent. Her reputation among the people of Paris was poor and there were fears of an assassination attempt; for her own safety she no longer went out into the streets. She slept with a loaded gun within reach; in case of an attack she wanted to be able to end her life, so as not to fall into the hands of the sans-culottes

The (, 'without breeches') were the common people of the lower classes in late 18th-century France, a great many of whom became radical and militant partisans of the French Revolution in response to their poor quality of life under the . T ...

alive.

Political relations were strained further because of the trial of the king and disagreements about the punishment that should be imposed on him. Most Girondin deputies voted against the death penalty, or at least against an immediate execution of the king. Madame Roland's letters indicate that she too was against the death sentence. After the execution of Louis XVI

The execution of Louis XVI by guillotine, a major event of the French Revolution, took place publicly on 21 January 1793 at the ''Place de la Révolution'' ("Revolution Square", formerly ''Place Louis XV'', and renamed ''Place de la Concorde'' in ...

on January 21, 1793, Jean-Marie Roland resigned as minister. The reasons are not entirely clear - possibly he resigned in protest against the execution, but possibly also because the work load, the ongoing personal and political attacks by the radicals, and the marital problems had become too much for him. Almost immediately, his papers were confiscated and an investigation was started into his actions as minister. The Rolands were also forbidden to leave Paris.Possibly this was a reprisal by his political opponents. A few months earlier, Roland had opened a strongbox with confidential documents of Louis XVI. He had handed this over to the Convention with the announcement that several delegates (none of them Girondins) appeared to have conspired with the king. He was accused of having destroyed papers that could have incriminated the Girondins.

In April of that year, Robespierre openly accused the Girondins of betraying the Revolution. A few weeks later, on 31 May, a 'revolutionary committee' (possibly set up by the Paris Commune) made an attempt to arrest Roland. He managed to escape. After hiding with the Rolands' friend the naturalist Bosc d'Antic in a former priory in the forest of Montmorency, he fled to Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

and from there to Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

. Madame Roland refused to flee or go into hiding; she even went to the Convention to personally protest against the attempted arrest of her husband. In her memoires she does not fully explain why she acted the way she did. Possibly she was convinced that there was no legal basis to arrest her, but in the early morning of June 1, 1793 she was arrested at her home and transferred to the prison in the abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christian monks and nuns.

The conc ...

. She was the first prominent Girondin to be incarcerated. A wave of arrests followed. A number of Girondin politicians, including Buzot, managed to escape from Paris.

Imprisonment

In prison, Madame Roland was allowed to receive visitors. Her assistant Sophie Grandchamp came every other day; Bosc d'Antic brought her flowers from the botanical garden on his regular visits. They smuggled out her letters to Buzot and presumably also to her husband (any letters to Roland have been lost). She studied English and even had a piano in her cell for a while. On 24 June she was released unexpectedly because the legal basis for her arrest had been flawed, but was rearrested on a new

On 24 June she was released unexpectedly because the legal basis for her arrest had been flawed, but was rearrested on a new indictment

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use the felonies concept often use that ...

the very moment she wanted to enter her home. She spent the rest of her imprisonment in the harsher prison of Sainte Pelagie. She was very concerned about the fate of Buzot, more than about Jean-Marie Roland. She was hurt and angry that in his memoires her husband planned to hold Buzot responsible for the crisis in their marriage. With some difficulty she managed to convince him to destroy the manuscript. She was convinced that she would eventually be put to death but refused to cooperate with an escape plan organized by Roland which involved exchanging clothes with a visitor; she thought this too risky for the visitor.

Outside of Paris, in the summer of 1793 resistance grew against the events in the capital. A revolt broke out in Lyon, and there were centres of resistance in Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

and Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

. In the provinces some Girondins argued in favour of a federal republic or even secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

from 'Paris'. Madame Roland implored her friends not to put themselves at risk but Buzot, who reportedly always carried a miniature

A miniature is a small-scale reproduction, or a small version. It may refer to:

* Portrait miniature, a miniature portrait painting

* Miniature art, miniature painting, engraving and sculpture

* Miniature (chess), a masterful chess game or proble ...

of Madame Roland and a lock of her hair with him, was involved in attempts to organise a revolt in Caen

Caen (, ; nrf, Kaem) is a commune in northwestern France. It is the prefecture of the department of Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inhabitants (), while its functional urban area has 470,000,Charlotte Corday

Marie-Anne Charlotte de Corday d'Armont (27 July 1768 – 17 July 1793), known as Charlotte Corday (), was a figure of the French Revolution. In 1793, she was executed by guillotine for the assassination of Jacobin leader Jean-Paul Marat, who ...

, a Girondin sympathizer from Caen, assassinated the popular Marat in Paris.

When Madame Roland heard in October that Buzot too was in danger of being arrested, she tried to end her life by refusing food. Bosc d'Antic and Sophie Grandchamp were able to convince her that it would be better to stand trial, because that way she would be able to answer her accusers and save her reputation.

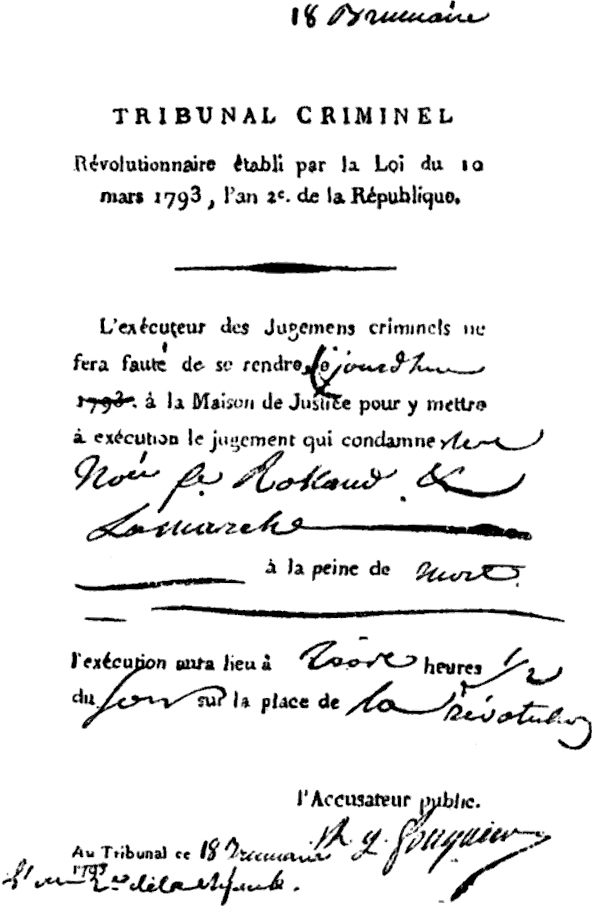

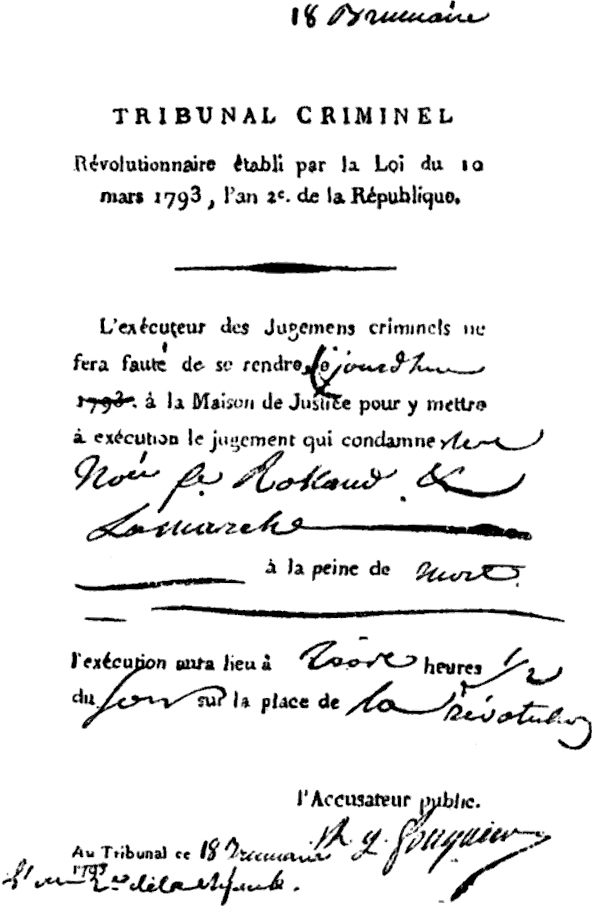

Trial and execution

On October 31, 1793, twenty-one Girondin politicians were executed after a short trial; most of them were known to Madame Roland and the group included her good friend Brissot.It is not clear whether Madame Roland was called as a witness during the trial against the Girondins. She was present in the building where the trial took place. However, the judge ruled at a certain point that the case had been going on long enough "because the accused had already been found guilty by the people." The next day she was transferred to the

On October 31, 1793, twenty-one Girondin politicians were executed after a short trial; most of them were known to Madame Roland and the group included her good friend Brissot.It is not clear whether Madame Roland was called as a witness during the trial against the Girondins. She was present in the building where the trial took place. However, the judge ruled at a certain point that the case had been going on long enough "because the accused had already been found guilty by the people." The next day she was transferred to the Conciergerie

The Conciergerie () ( en, Lodge) is a former courthouse and prison in Paris, France, located on the west of the Île de la Cité, below the Palais de Justice. It was originally part of the former royal palace, the Palais de la Cité, which also ...

, the prison known as the last stop on the way to the guillotine

A guillotine is an apparatus designed for efficiently carrying out executions by beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secured with stocks at t ...

; immediately upon arrival she was questioned by the prosecutor for two days. She defended herself in her customary self-assured, (according to the newspaper ''Le Moniteur Universel

was a French newspaper founded in Paris on November 24, 1789 under the title by Charles-Joseph Panckoucke, and which ceased publication on December 31, 1868. It was the main French newspaper during the French Revolution and was for a long tim ...

'') even haughty manner against the accusations, but also argued in her defense that she was 'only a wife' and therefore could not be held responsible for the political actions of her husband. According to eyewitnesses like her fellow prisoner and political adversary Jacques Claude Beugnot

Jacques Claude, comte Beugnot (25 July 1761 – 24 June 1835) was a French politician before, during, and after the French Revolution. His son Auguste Arthur Beugnot was an historian and scholar.

Biography

Revolution

Born at Bar-sur-Aube (A ...

she remained calm and courageous during her stay in the Conciergerie. On 8 November she appeared before the Revolutionary Tribunal

The Revolutionary Tribunal (french: Tribunal révolutionnaire; unofficially Popular Tribunal) was a court instituted by the National Convention during the French Revolution for the trial of political offenders. It eventually became one of the ...

. She had no doubt that she would be sentenced to death and dressed that day in the 'toilette de mort' she had selected some time before: a simple dress of white-yellow muslin with a black belt. After a short trial she was found guilty of conspiracy against the revolution and the death sentence was pronounced; the judge did not allow her to read a statement she had prepared.

The sentence was carried out the same day. Sophie Grandchamp and the historian Pierre François Tissot

Pierre François Tissot (20 March 1768 – 7 April 1854) was a French man of letters and politician.

Biography

Early years

Tissot was born in Versailles to a native of Savoy, who was a perfumer appointed by royal warrant to the court. At the ag ...

saw her pass on her way to the scaffold and reported that she appeared very calm. There are two versions handed down concerning her last words at the foot of the guillotine: 'Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

and the feminist Olympe de Gouges

Olympe de Gouges (; born Marie Gouze; 7 May 17483 November 1793) was a French playwright and political activist whose writings on women's rights and abolitionism reached a large audience in various countries. She began her career as a playwright ...

, she had been put to death because she had crossed the "boundaries of female virtue."

When a few days later Jean-Marie Roland heard in his hiding place in Rouen that his wife had been executed, he committed suicide. Her beloved Buzot lived as a fugitive for several months and then also ended his own life. After the death of her parents, daughter Eudora came under the guardianship of Bosc d'Antic and later married a son of the journalist Luc-Antoine de Champagneux.

Legacy

Memoirs and letters

During the five months she was imprisoned, Madame Roland wrote her memoirs entitled ''Appel à l'impartiale postérité'' (''Appeal to the impartial posterity''). These consist of three parts: * ''Mémoires historiques (historical memories)'', a defense of her political actions in the years 1791 - 1793, * ''Mémoires particuliers (personal memories)'', in which she describes her childhood and upbringing, * ''Mes dernières pensées (my last thoughts)'', an epilogue she wrote when she decided in early October 1793 to end her life by a hunger strike. Particularly in the ''Mémoires historiques'' she goes to a lot of effort to show that she had been "just the wife" and had always behaved in a way that was considered appropriate for a woman of her time. She is indignant that the Jacobin press compared her to the influential noble women from the ancien regime. At the same time, through her description of events she shows - consciously or unconsciously - how big her influence was within the Girondin circle, and how fundamentally important her contribution to Roland's ministry. She provides a fairly reliable and accurate account of events, although she sometimes leaves out things that do not show her in the most favourable light. She was certainly not neutral in her description of people she did not like.

In the ''Mémoires particuliers'' she reports on her personal life in a way that was unusual for a woman of that time. She speaks of a sexual assault by a pupil of her father, her experiences during her wedding night and her problems with breastfeeding. In this she followed

Particularly in the ''Mémoires historiques'' she goes to a lot of effort to show that she had been "just the wife" and had always behaved in a way that was considered appropriate for a woman of her time. She is indignant that the Jacobin press compared her to the influential noble women from the ancien regime. At the same time, through her description of events she shows - consciously or unconsciously - how big her influence was within the Girondin circle, and how fundamentally important her contribution to Roland's ministry. She provides a fairly reliable and accurate account of events, although she sometimes leaves out things that do not show her in the most favourable light. She was certainly not neutral in her description of people she did not like.

In the ''Mémoires particuliers'' she reports on her personal life in a way that was unusual for a woman of that time. She speaks of a sexual assault by a pupil of her father, her experiences during her wedding night and her problems with breastfeeding. In this she followed Rousseau