July 1963 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The following events occurred in July 1963:

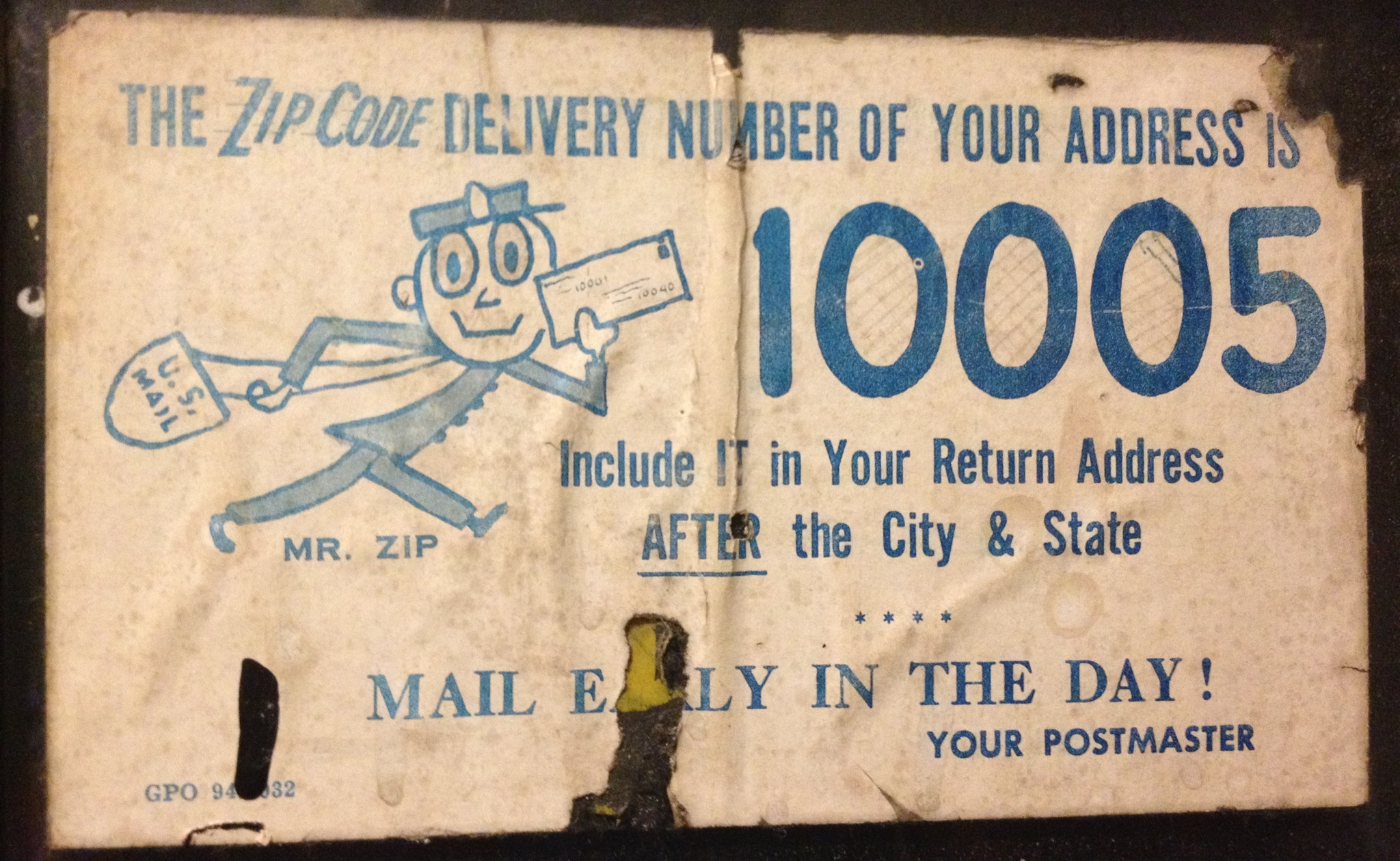

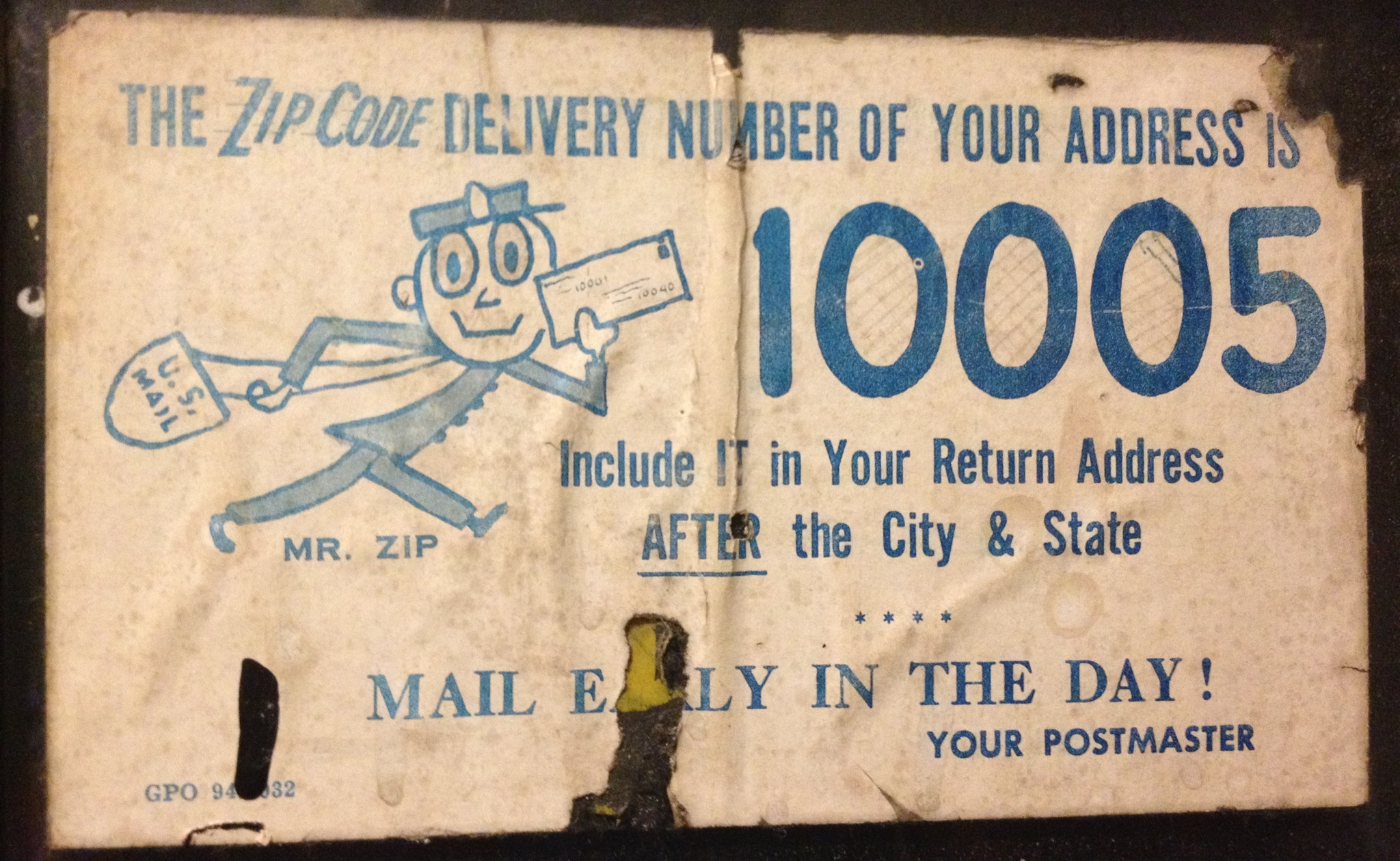

July 1, 1963 (Monday)

* ZIP Codes were introduced in the United States, as the U.S. Department of the Post Office kicked off a massive advertising campaign that included the cartoon character "Mr. ZIP", and the mailing that day of more than 72,000,000 postcards to every mailing address in the United States, in order to inform the addressees of their new five digit postal code. Postal zones had been used since 1943 in large cities, but the ZIP code was nationwide. Use became mandatory in 1967 for bulk mailers. *Kim Philby

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby (1 January 191211 May 1988) was a British intelligence officer and a double agent for the Soviet Union. In 1963 he was revealed to be a member of the Cambridge Five, a spy ring which had divulged British secr ...

was named by the Government of the United Kingdom

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_es ...

as the 'Third Man' in the Burgess __NOTOC__

Burgess may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Burgess (surname), a list of people and fictional characters

* Burgess (given name), a list of people

Places

* Burgess, Michigan, an unincorporated community

* Burgess, Missouri, U ...

and Maclean

MacLean, also spelt Maclean and McLean, is a Gaelic surname Mac Gille Eathain, or, Mac Giolla Eóin in Irish Gaelic), Eóin being a Gaelic form of Johannes (John). The clan surname is an Anglicisation of the Scottish Gaelic "Mac Gille Eathai ...

Soviet spy ring.

*The crash of a Varig

VARIG (acronym for Viação Aérea RIo-Grandense, ''Rio Grandean Airways'') was the first airline founded in Brazil, in 1927. From 1965 until 1990, it was Brazil's leading airline, and virtually its only international one. In 2005, Varig went ...

DC-3 airliner in Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

's Rio Grande do Sul state killed 15 of the 18 people on board. The flight was approaching the airport at Passo Fundo

Passo Fundo is a municipality in the north of the southern Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul. It is named after its river. It's the twelfth largest city in the state with an estimated population of 204,722 inhabitants living in a total municip ...

on the second-leg of a scheduled trip from Porto Alegre

Porto Alegre (, , Brazilian ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul. Its population of 1,488,252 inhabitants (2020) makes it the twelfth most populous city in the country and the center of Brazil's fif ...

when it impacted trees.

*Died: Abdullah bin Khalifa

Sir Abdullah bin Khalifa Al-Said, , (12 February 1910 – 1 July 1963) ( ar, عبد الله بن خليفة), was the 10th Sultan of Zanzibar after the death of his father, Sir Khalifa bin Harub, who died on 9 October 1960 at age eighty-on ...

, 53, Sultan of Zanzibar since 1960, died two days after undergoing emergency surgery. He was succeeded by his son, Jamshid bin Abdullah

Sultan Sir Jamshid bin Abdullah Al Said, ( ar, جمشيد بن عبد الله; born 16 September 1929), is a Zanzibari royal who was the last reigning Sultan of Zanzibar before being deposed in the 1964 Zanzibar Revolution.

Biography

Jamshid ...

, the last to hold the title.

July 2

Events Pre-1600

* 437 – Emperor Valentinian III begins his reign over the Western Roman Empire. His mother Galla Placidia ends her regency, but continues to exercise political influence at the court in Rome.

* 626 – Li Shimin, t ...

, 1963 (Tuesday)

*In a speech while visiting East Berlin, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

endorsed the idea for the first time of a treaty to ban atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons. Khrushchev criticized the idea of sending inspectors to verify compliance, but said that "Since the Western powers obstruct the conclusion of an agreement banning all nuclear tests, the Soviet Government expresses its willingness to conclude an agreement banning nuclear tests in the atmosphere, in outer space and under water."

*Mohawk Airlines Flight 121

Mohawk Airlines Flight 112 was a scheduled passenger flight from Rochester-Monroe Airport in Rochester, New York to Newark International Airport in Newark, New Jersey. On July 2, 1963, the aircraft operating the flight, a Martin 4-0-4 with a to ...

, a Martin 4-0-4

The Martin 4-0-4 was an American pressurized passenger airliner built by the Glenn L. Martin Company. In addition to airline use initially in the United States, it was used by the United States Coast Guard and United States Navy as the RM-1G ( ...

, crashed on takeoff at Rochester, New York

Rochester () is a city in the U.S. state of New York, the seat of Monroe County, and the fourth-most populous in the state after New York City, Buffalo, and Yonkers, with a population of 211,328 at the 2020 United States census. Located in W ...

, in the United States, killing 7 of the 43 people on board and injuring all 36 survivors. The plane was flying to White Plains, New York

(Always Faithful)

, image_seal = WhitePlainsSeal.png

, seal_link =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Country

, subdivision_name =

, subdivision_type1 = U.S. state, State

, su ...

and, according to a witness "just as the craft began roaring down the runway for a take-off torrents of rain and hail pummeled it."

*Brian Sternberg

Brian Sternberg (June 21, 1943 – May 23, 2013) was a world record holder in the men's pole vault who was paralyzed from the neck down after a trampoline accident in 1963.

Sternberg set one of his world records on May 25, 1963, in Modesto, Ca ...

, the world record holder for the pole vault, broke his neck after falling from a trampoline, and was left a quadriplegic

Tetraplegia, also known as quadriplegia, is defined as the dysfunction or loss of motor and/or sensory function in the cervical area of the spinal cord. A loss of motor function can present as either weakness or paralysis leading to partial or ...

.

*Baseball pitchers Juan Marichal

Juan Antonio Marichal Sánchez (born October 20, 1937), nicknamed "the Dominican Dandy", is a Dominican former right-handed pitcher in Major League Baseball who played for three teams from 1960 to 1975, almost entirely the San Francisco Giant ...

of the San Francisco Giants

The San Francisco Giants are an American professional baseball team based in San Francisco, California. The Giants compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) West division. Founded in 1883 as the New Y ...

, and Warren Spahn

Warren Edward Spahn (April 23, 1921 – November 24, 2003) was an American professional baseball pitcher who played 21 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB). A left-handed pitcher, Spahn played in 1942 and then from 1946 until 1965, most notabl ...

of the Milwaukee Braves faced off against each other in a National League baseball game that one author would later call "the greatest game ever pitched". Tied 0-0 after nine innings, the game was won in the 16th by the Giants on a home run by Willie Mays

Willie Howard Mays Jr. (born May 6, 1931), nicknamed "the Say Hey Kid" and "Buck", is a former center fielder in Major League Baseball (MLB). Regarded as one of the greatest players ever, Mays ranks second behind only Babe Ruth on most all-tim ...

.

*Liberace

Władziu Valentino Liberace (May 16, 1919 – February 4, 1987) was an American pianist, singer, and actor. A child prodigy born in Wisconsin to parents of Italian and Polish origin, he enjoyed a career spanning four decades of concerts, recordi ...

and Barbra Streisand

Barbara Joan "Barbra" Streisand (; born April 24, 1942) is an American singer, actress and director. With a career spanning over six decades, she has achieved success in multiple fields of entertainment, and is among the few performers awar ...

opened a run of shows at the Riviera

''Riviera'' () is an Italian word which means "coastline", ultimately derived from Latin , through Ligurian . It came to be applied as a proper name to the coast of Liguria, in the form ''Riviera ligure'', then shortened in English. The two areas ...

in Las Vegas

Las Vegas (; Spanish for "The Meadows"), often known simply as Vegas, is the 25th-most populous city in the United States, the most populous city in the state of Nevada, and the county seat of Clark County. The city anchors the Las Vegas ...

, Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a state in the Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the 7th-most extensive, ...

.

*The 13th Berlin International Film Festival

The 13th annual Berlin International Film Festival was held from 21 June to 2 July 1963. The Golden Bear was awarded ''ex aequo'' to the Italian film ''Il diavolo'' directed by Gian Luigi Polidoro and Japanese film '' Bushidô zankoku monogatari ...

concluded. The Golden Bear

The Golden Bear (german: Goldener Bär) is the highest prize awarded for the best film at the Berlin International Film Festival. The bear is the heraldic animal of Berlin, featured on both the coat of arms and flag of Berlin.

History

The win ...

was jointly awarded to '' Il diavolo'' by Gian Luigi Polidoro

Gian Luigi Polidoro (4 February 1927 – 7 September 2000) was an Italian film director and screenwriter. He directed 16 films between 1956 and 1998. His 1963 film '' Il diavolo'' won the Golden Bear at the 13th Berlin International Film F ...

and '' Bushidô zankoku monogatari'' by Tadashi Imai

was a Japanese film director known for social realist filmmaking informed by a left-wing perspective. His most noted films include ''An Inlet of Muddy Water'' (1953) and ''Bushido, Samurai Saga'' (1963).

Life

Although leaning towards left-wing p ...

.

*Died: Alicia Patterson

Alicia Patterson (October 15, 1906 – July 2, 1963) was an American journalist, the founder and editor of ''Newsday''. With Neysa McMein, she created the ''Deathless Deer'' comic strip in 1943.

Early life

Patterson was the middle daughter of Al ...

, 56, American editor and publisher who founded the newspaper '' Newsday'' in 1940 for New York's Long Island, died of complications following surgery for an ulcer.

July 3

Events Pre-1600

* 324 – Battle of Adrianople: Constantine I defeats Licinius, who flees to Byzantium.

* 987 – Hugh Capet is crowned King of France, the first of the Capetian dynasty that would rule France until the French Revolut ...

, 1963 (Wednesday)

* National Airways Corporation Flight 441, a Douglas DC-3C

The Douglas DC-3 is a propeller-driven airliner

manufactured by Douglas Aircraft Company, which had a lasting effect on the airline industry in the 1930s to 1940s and World War II.

It was developed as a larger, improved 14-bed sleeper version ...

, flew into a vertical rock face in New Zealand's Kaimai Ranges

The Kaimai Range (sometimes referred to as the ''Kaimai Ranges'') is a mountain range in the North Island of New Zealand. It is part of a series of ranges, with the Coromandel Range to the north and the Mamaku Ranges to the south. The Kaimai R ...

near Mount Ngatamahinerua, killing all 23 people on board.

*The 100th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

, turning point of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, was celebrated with a re-enactment of Pickett's charge.

*Died: Povl Baumann, 74, Danish architect

July 4

Events Pre-1600

*362 BC – Battle of Mantinea: The Thebans, led by Epaminondas, defeated the Spartans.

* 414 – Emperor Theodosius II, age 13, yields power to his older sister Aelia Pulcheria, who reigned as regent and proclaime ...

, 1963 (Thursday)

*The Constitution of Austria

The Constitution of Austria (german: Österreichische Bundesverfassung) is the body of all constitutional law of the Republic of Austria on the federal level. It is split up over many different acts. Its centerpiece is the Federal Constitutional ...

was amended to ease the 1919 act that had declared that "In the interest of the security of the Republic the former holders of the Crown and other members of the House of Habsburg-Lothringen

The House of Lorraine (german: link=no, Haus Lothringen) originated as a cadet branch of the House of Metz. It inherited the Duchy of Lorraine in 1473 after the death without a male heir of Nicholas I, Duke of Lorraine. By the marriage of Fran ...

are banished from the country", providing an exception for descendants of the former monarchs if they elected to "expressly renounce their membership of this House".

*Born:

** Christopher G. Kennedy, U.S. businessman; in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, to Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

and Ethel Skakel Kennedy, the eighth of their eleven children

**Ute Lemper

Ute Gertrud Lemper (; born 4 July 1963) is a German singer and actress. Her roles in musicals include playing Sally Bowles in the original Paris production of ''Cabaret'', for which she won the 1987 Molière Award for Best Newcomer, and Velm ...

, German singer and actress; in Münster

Münster (; nds, Mönster) is an independent city (''Kreisfreie Stadt'') in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state di ...

, West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

**Jan Mølby

Jan Mølby (; born 4 July 1963) is a Danish former professional footballer and manager. As a player, he was a midfielder from 1982 to 1998. After starting his career with Kolding, he moved on to Ajax before spending twelve years playing in Engl ...

, Danish footballer; in Kolding

Kolding () is a Danish seaport located at the head of Kolding Fjord in the Region of Southern Denmark. It is the seat of Kolding Municipality. It is a transportation, commercial, and manufacturing centre, and has numerous industrial companie ...

*Died: Bernard Freyberg, 74, Governor-General of New Zealand 1946–1952

July 5

Events Pre-1600

* 328 – The official opening of Constantine's Bridge built over the Danube between Sucidava (Corabia, Romania) and Oescus ( Gigen, Bulgaria) by the Roman architect Theophilus Patricius.

* 1316 – The Burgundian a ...

, 1963 (Friday)

*A delegation from the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, led by Prime Minister Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai (; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman and military officer who served as the first premier of the People's Republic of China from 1 October 1949 until his death on 8 January 1976. Zhou served under Chairman Ma ...

, departed from Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

on a train bound for Moscow, to attend talks in an effort to repair the poor relations between the Chinese Communists and Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The talks, intended to mend the Sino-Soviet split

The Sino-Soviet split was the breaking of political relations between the China, People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union caused by Doctrine, doctrinal divergences that arose from their different interpretations and practical applications ...

, would break down on July 14 when the Soviets published a rebuttal to Chinese charges that the Soviets had departed from the Communist ideology.

*Italian Prime Minister Giovanni Leone received a vote of confidence in the Italian Senate, 133–110.

*The U.S. Senate set a new record for briefest session by meeting at 9:00 am, and then adjourning three seconds later. There were only two Senators present for the meeting. The previous record for brevity had been a five-second meeting on September 4, 1951.

*McDonnell Aircraft Corporation

The McDonnell Aircraft Corporation was an American aerospace manufacturer based in St. Louis, Missouri. The company was founded on July 6, 1939, by James Smith McDonnell, and was best known for its military fighters, including the F-4 Phantom I ...

began the first phase of Spacecraft Systems Tests (SST) on the instrumentation pallets to be installed in Gemini spacecraft

Project Gemini () was NASA's second human spaceflight program. Conducted between projects Mercury and Apollo, Gemini started in 1961 and concluded in 1966. The Gemini spacecraft carried a two-astronaut crew. Ten Gemini crews and 16 individual ...

No. 1. The first engineering prototype Gemini inertial guidance system computer underwent integration and compatibility testing with a complete guidance and control system at McDonnell. All spacecraft

A spacecraft is a vehicle or machine designed to fly in outer space. A type of artificial satellite, spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including communications, Earth observation, meteorology, navigation, space colonization, p ...

wiring was found to be compatible with the computer, and the component operated with complete accuracy.

*The sale of liquor, by the drink, was legal in the U.S. state of Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to th ...

for the first time in more than 40 years, with "a restaurant in the lakes resort area in northwest Iowa" becoming the site of the first legal drink.

July 6

Events Pre-1600

* 371 BC – The Battle of Leuctra shatters Sparta's reputation of military invincibility.

* 640 – Battle of Heliopolis: The Muslim Arab army under 'Amr ibn al-'As defeat the Byzantine forces near Heliopolis (Egypt ...

, 1963 (Saturday)

*The Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

relaxed the ban on cremation

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre is ...

as a funeral practice, when Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his death in Augus ...

issued the Instruction that "the burning of the body, after all, has no effect on the soul, nor does it inhibit Almighty God from re-establishing the body", although the decision would not be revealed until May 2, 1964.

*The Vanoise National Park

Vanoise National Park (french: Parc national de la Vanoise) is a French national park between the Tarentaise and Maurienne valleys in the French Alps, containing the Vanoise massif. It was created in 1963 as the first national park in France.

...

, located in the department of Savoie

Savoie (; Arpitan: ''Savouè'' or ''Savouè-d'Avâl''; English: ''Savoy'' ) is a department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, Southeastern France. Located in the French Alps, its prefecture is Chambéry. In 2019, Savoie had a population ...

in the French Alps, was designated France's first National Park.

* Elections were held in Jordan for the 80 seats in the Chamber of Deputies of the National Assembly. All of the candidates were independent, in that political parties were banned at the time, and the results, as with most of the elections in Jordan to that time, were "poorly documented" and not officially published.

*A partial lunar eclipse

A lunar eclipse occurs when the Moon moves into the Earth's shadow. Such alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six months, during the full moon phase, when the Moon's orbital plane is closest to the plane of the Earth ...

took place.

*Died: George, Duke of Mecklenburg

George, Duke of Mecklenburg (german: Georg Herzog zu Mecklenburg; – 6 July 1963) was the head of the House of Mecklenburg-Strelitz from 1934 until his death. Through his father, he was a descendant of Emperor Paul I of Russia.

Early life

He wa ...

, 63, head of the House of Mecklenburg-Strelitz since 1934. He was succeeded by his son Georg Alexander

Georg Alexander (born Werner Ludwig Georg Lüddeckens; 3 April 1888 – 30 October 1945) was a German film actor who was a prolific presence in German cinema. He also directed a number of films during the silent era.

Personal life

He was married ...

.

July 7

Events Pre-1600

* 1124 – The city of Tyre falls to the Venetian Crusade after a siege of nineteen weeks.

* 1456 – A retrial verdict acquits Joan of Arc of heresy 25 years after her execution.

* 1520 – Spanish ''conquistad ...

, 1963 (Sunday)

*In the first round of Argentina's presidential election, Dr. Arturo Illia

Arturo Umberto Illia (; 4 August 1900 – 18 January 1983) was an Argentine politician and physician, who was President of Argentina from 12 October 1963, to 28 June 1966. He was a member of the centrist Radical Civic Union.

Illia reached t ...

won a 25 percent plurality of the popular votes (2,441,064) and 169 of the 476 Electoral College votes, seventy short of a majority. Another physician, Dr. Oscar Alende

Oscar Eduardo Alende (6 July 1909 – 22 December 1996) was an Argentine politician who founded the Intransigent Party.

Alende was born in Maipú, Buenos Aires Province. He studied medicine at the University of La Plata, where he led the ...

, finished with 16.4%, and former General Pedro Aramburu

Pedro Eugenio Aramburu Silveti (May 21, 1903 – June 1, 1970) was an Argentine Army general. He was a major figure behind the '' Revolución Libertadora'', the military coup against Juan Perón in 1955. He became dictator of Argentina, servin ...

was third. On July 31, electors for several of the other parties would vote for Illia, giving him 270 electoral votes. Dr. Illia's Radical Civic Union (UCR) Party (UCR) won only 72 of the 192 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, and Illia did not try to forge a coalition with the other parties.

*Seven people, including four children, were killed, and 17 injured, when a pilotless FJ-4 Fury jet fighter crashed into gatherers at a family reunion at the Green Hills Day Camp in Willow Grove, Pennsylvania

Willow Grove is a census-designated place (CDP) in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, United States. A community in Philadelphia's northern suburbs, the population was 15,726 at the 2010 census. It is located in Upper Dublin Township, Abington To ...

. The pilot had ejected after plane malfunctioned while he was attempting to land at the nearby Willow Grove Naval Air Station, and the jet crashed into a baseball field, killing one man, then skidded into a bathhouse where 50 people had been swimming or standing around the pool.

*In a fight between South Vietnamese government police and U.S. reporters, secret police loyal to Ngô Đình Nhu

Ngô Đình Nhu (; 7 October 19102 November 1963; baptismal name Jacob) was a Vietnamese archivist and politician. He was the younger brother and chief political advisor of South Vietnam's first president, Ngô Đình Diệm. Although he held n ...

, brother of President Ngô Đình Diệm, attacked American journalists including Peter Arnett

Peter Gregg Arnett (born 13 November 1934) is a New Zealand-born American journalist. He is known for his coverage of the Vietnam War and the Gulf War. He was awarded the 1966 Pulitzer Prize in International Reporting for his work in Vietn ...

and David Halberstam

David Halberstam (April 10, 1934 April 23, 2007) was an American writer, journalist, and historian, known for his work on the Vietnam War, politics, history, the Civil Rights Movement, business, media, American culture, Korean War, and late ...

at a demonstration during the Buddhist crisis

The Buddhist crisis ( vi, Biến cố Phật giáo) was a period of political and religious tension in South Vietnam between May and November 1963, characterized by a series of repressive acts by the South Vietnamese government and a campaign o ...

.

*Died: Frank P. Lahm

Frank Purdy Lahm (November 17, 1877 – July 7, 1963) was an American aviation pioneer, the "nation's first military aviator", and a general officer in the United States Army Air Corps and Army Air Forces.

Lahm developed an interest in flying f ...

, 85, U.S. aviation pioneer who became, in 1909, the first military aviator after being selected by the U.S. Army to receive instruction on the Wright Flyer

The ''Wright Flyer'' (also known as the ''Kitty Hawk'', ''Flyer'' I or the 1903 ''Flyer'') made the first sustained flight by a manned heavier-than-air powered and controlled aircraft—an airplane—on December 17, 1903. Invented and flown b ...

by Wilbur Wright

July 8, 1963 (Monday)

*Three crewmen of the British cargo ship ''Patrician'' were killed after it collided with the U.S. ship ''Santa Emilia'' and sank offGibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

. Thirty-four of the 37 crew were rescued by ''Santa Emilia''.

*The British comic strip '' Fred Basset'' was introduced, starting with its first appearance in the '' Daily Mail''. Created by Scottish cartoonist Alex Graham, the strip, about the adventures of a basset hound

The Basset Hound is a short-legged breed of dog in the hound family. The Basset is a scent hound that was originally bred for the purpose of hunting hare. Their sense of smell and ability to ''ground-scent'' is second only to the Bloodhound.Har ...

, is syndicated worldwide.

*Members of the 1963 American Everest Expedition team were awarded the Hubbard Medal

The Hubbard Medal is awarded by the National Geographic Society for distinction in exploration, discovery, and research. The medal is named for Gardiner Greene Hubbard

Gardiner Greene Hubbard (August 25, 1822 – December 11, 1897) was an A ...

by U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

for their achievement.

*McDonnell warned Gemini Project Office that the capacity of the Gemini Guidance Computer was in danger of being exceeded. The original function of the computer had been limited to providing rendezvous and reentry

Atmospheric entry is the movement of an object from outer space into and through the gases of an atmosphere of a planet, dwarf planet, or natural satellite. There are two main types of atmospheric entry: ''uncontrolled entry'', such as the ...

guidance. Other functions were subsequently added, and the computer's spare capacity no longer appeared adequate to handle all of them. McDonnell requested an immediate review of computer requirements. In the meantime, it advised International Business Machines to delete one of the added functions, orbital navigation, from computers for spacecraft Nos. 2 and 3.

July 9, 1963 (Tuesday)

*The "20-point agreement

The 20-point agreement, or the 20-point memorandum, is a list of 20 points drawn up by North Borneo, proposing terms for its incorporation into the new federation as the State of Sabah, during negotiations prior to the formation of Malaysia. In t ...

" to create the Federation of Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions: Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Malaysia ...

, effective September 16, was signed in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

by the UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and representatives of four of the five intended members of Malaysia: the Federation of Malaya, the Crown Colony of North Borneo

The Crown Colony of North Borneo was a British Crown colony on the island of Borneo established in 1946 shortly after the dissolution of the British Military Administration. The Crown Colony of Labuan joined the new Crown Colony during its f ...

(which became the state of Sabah

Sabah () is a state of Malaysia located in northern Borneo, in the region of East Malaysia. Sabah borders the Malaysian state of Sarawak to the southwest and the North Kalimantan province of Indonesia to the south. The Federal Territory o ...

), State of Sarawak and the state of Singapore. The fifth member, the British protectorate over the Sultanate of Brunei, declined to join the Federation. The state of Singapore would be expelled from the Federation of Malaysia on August 9, 1965 and would become an independent republic.

*Gemini astronaut candidates began testing of the " human centrifuge" equipped to simulate the command pilot's position in the spacecraft. The testing was for evaluation of pilot controls and displays required for launch and reentry of a Gemini mission, along with the seat and pressure suit

A pressure suit is a protective suit worn by high-altitude pilots who may fly at altitudes where the air pressure is too low for an unprotected person to survive, even breathing pure oxygen at positive pressure. Such suits may be either full-pr ...

operation under acceleration

In mechanics, acceleration is the rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Accelerations are vector quantities (in that they have magnitude and direction). The orientation of an object's acceleration is given by t ...

, and the restraint system. The participating astronauts were generally satisfied but recommended minor changes.

*The G2C Gemini pressure suit made by David Clark Company

David Clark Company, Inc. is an American manufacturing company. DCC designs and manufactures a wide variety of aerospace and industrial protective equipment, including pressure-space suit systems, anti-G suits, headsets, and several medical/safet ...

proved unsatisfactory because the torso could be stretched out of shape and a visor guard had made the helmet too large to wear during use of the escape hatch.

July 10

Events Pre-1600

* 138 – Emperor Hadrian of Rome dies of heart failure at his residence on the bay of Naples, Baiae; he is buried at Rome in the Tomb of Hadrian beside his late wife, Vibia Sabina.

* 645 – Isshi Incident: Prin ...

, 1963 (Wednesday)

*Project Emily

Project Emily was the deployment of American-built Thor intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) in the United Kingdom between 1959 and 1963. Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command operated 60 Thor missiles, dispersed to 20 RAF air stations ...

, the deployment of American-built PGM-17 Thor Intermediate-range ballistic missiles in the United Kingdom, was disbanded.

*The brief partnership of "Rodgers and Lerner" was dissolved, and production of the first Rodgers-Lerner musical, ''I Picked a Daisy'', was halted permanently. Composer Richard Rodgers had successfully collaborated with lyricist Lorenz Hart (''Babes in Arms''), and then with lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II (''The Sound of Music''), while lyricist Alan Jay Lerner had a successful team with composer Frederick Loewe (''My Fair Lady''). The two were unable to work together successfully beyond "half a dozen" songs for ''Daisy''.

*The all-white University of South Carolina was ordered to admit its first African-American student, Henri Monteith, by order of U.S. District Judge J. Robert Martin. On the same day, Judge Martin ordered the desegregation of all 26 of South Carolina's state parks.

*A Vostok-2 rocket launched by the USSR failed shortly after take-off.

*Coordination between NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil List of government space agencies, space program ...

and the U.S. Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense (DoD, USDOD or DOD) is an executive branch department of the federal government charged with coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government directly related to national secur ...

(DOD) in crewed space station studies was reported by a panel to be inadequate, especially at the technical level.

July 11

Events Pre-1600

* 472 – After being besieged in Rome by his own generals, Western Roman Emperor Anthemius is captured in St. Peter's Basilica and put to death.

* 813 – Byzantine emperor Michael I, under threat by conspiracies, ...

, 1963 (Thursday)

*A military coup ousted Carlos Julio Arosemena Monroy, President of Ecuador, who was succeeded by naval commander Ramón Castro Jijón. After surrendering the presidential palace, Arosemena was placed on an Ecuadorian Air Force plane and flown to Panama. The "final straw" for the coup leaders had been a state dinner the night before, "when the obviously inebriated president made disparaging remarks about the United States" while talking to the American ambassador.

*The sinking of the Argentine ferry ''Ciudad de Asunción'' killed 53 of the 420 people on board after the boat caught fire and went down in the River Plate between Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

in Argentina and Montevideo in Uruguay.

*In South Africa, 19 ANC and MK leaders, including Arthur Goldreich

Arthur Goldreich (25 December 1929 – 24 May 2011) was a South African-Israeli abstract painter and a key figure in the anti-apartheid movement in the country of his birth and a critic of the form of Zionism practiced in Israel.

Early life

Gold ...

and Walter Sisulu

Walter Max Ulyate Sisulu (18 May 1912 – 5 May 2003) was a South African anti-apartheid activist and member of the African National Congress (ANC). Between terms as ANC Secretary-General (1949–1954) and ANC Deputy President (1991–1994), h ...

, were arrested at Liliesleaf Farm

Liliesleaf Farm is a location in northern Johannesburg, South Africa, which is most noted for its use as a safe house for African National Congress activists in the 1960s. In 1963, the South African police raided the farm, arresting more than a do ...

, Rivonia, the headquarters of Umkhonto we Sizwe.

*The Manned Spacecraft Center

The Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC) is NASA's center for human spaceflight (originally named the Manned Spacecraft Center), where human spaceflight training, research, and flight control are conducted. It was renamed in honor of the late U ...

(MSC) informed the Defense Department of unresolved range safety

In the field of rocketry, range safety may be assured by a system which is intended to protect people and assets on both the rocket range and downrange in cases when a launch vehicle might endanger them. For a rocket deemed to be ''off course' ...

problems concerning a catastrophic failure of the Gemini launch vehicle because of a tank rupture and recommended use of a hypergolic propellant rather than cryogenic fuel

Cryogenic fuels are fuels that require storage at extremely low temperatures in order to maintain them in a liquid state. These fuels are used in machinery that operates in space (e.g. rockets and satellites) where ordinary fuel cannot be used, d ...

.

*Born: Al MacInnis

Allan MacInnis (born July 11, 1963) is a Canadian former professional ice hockey defenceman who played 23 seasons in the National Hockey League (NHL) for the Calgary Flames (1981-1994) and St. Louis Blues (1994-2004). A first round selection of ...

, Canadian NHL and Olympic champion ice hockey defenceman who played in 1,416 games from 1982 to 2003; in Port Hood, Municipality of the County of Inverness

The Municipality of the County of Inverness is a county municipality on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. It provides local government to about 17,000 residents of the historical county of the same name, except for the incorporated tow ...

, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

July 12

Events Pre-1600

* 70 – The armies of Titus attack the walls of Jerusalem after a six-month siege. Three days later they breach the walls, which enables the army to destroy the Second Temple.

* 927 – King Constantine II o ...

, 1963 (Friday)

*The Congress of the Philippines approved a land reform program that had been proposed by President Diosdado Macapagal. Among other things, the law outlawed sharecropping

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

and provided for a means of large estates to be gradually turned over to the people who farmed them.

*Pauline Reade, 16, was abducted and murdered by Myra Hindley

The Moors murders were carried out by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley between July 1963 and October 1965, in and around Manchester, England. The victims were five children—Pauline Reade, John Kilbride, Keith Bennett, Lesley Ann Downey, and Edward E ...

and Ian Brady

The Moors murders were carried out by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley between July 1963 and October 1965, in and around Manchester, England. The victims were five children—Pauline Reade, John Kilbride, Keith Bennett, Lesley Ann Downey, and Edward E ...

in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

, England, in the first of the "Moors murders

The Moors murders were carried out by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley between July 1963 and October 1965, in and around Manchester, England. The victims were five children—Pauline Reade, John Kilbride, Keith Bennett, Lesley Ann Downey, and Edward E ...

". Reade's remains would not be discovered until July 1, 1987.

*The first "Gambit" military reconnaissance satellite was launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base Vandenberg may refer to:

* Vandenberg (surname), including a list of people with the name

* USNS ''General Hoyt S. Vandenberg'' (T-AGM-10), transport ship in the United States Navy, sank as an artificial reef in Key West, Florida

* Vandenberg Sp ...

in California at 1:44 p.m., and the film recovered proved it to be a major advancement in observation. The new system had "exceptional pointing accuracy" in aiming its cameras, and the pictures obtained had a resolution of .

*Gemini Project Office completed its high-gravity human centrifuge testing.

*NASA approved backing up the first Gemini flight payload with a boilerplate reentry module

A reentry capsule is the portion of a space capsule which returns to Earth following a spaceflight. The shape is determined partly by aerodynamics; a capsule is aerodynamically stable falling blunt end first, which allows only the blunt end to re ...

and a production adapter

An adapter or adaptor is a device that converts attributes of one electrical device or system to those of an otherwise incompatible device or system. Some modify power or signal attributes, while others merely adapt the physical form of one c ...

, at an additional cost of $1,500,000.

*Died: Slatan Dudow

Slatan Theodor Dudow ( bg, Златан Дудов, Zlatan Dudov) (30 January 1903 - 12 July 1963) was a Bulgarian born film director and screenwriter who made a number of films during the Weimar Republic and in East Germany.

Biography

Dudow wa ...

, 60, Bulgarian film director and screenwriter

July 13

Events Pre-1600

* 1174 – William I of Scotland, a key rebel in the Revolt of 1173–74, is captured at Alnwick by forces loyal to Henry II of England.

* 1249 – Coronation of Alexander III as King of Scots.

*1260 – The Livon ...

, 1963 (Saturday)

*The Legislative Assembly of the Cook Islands

)

, image_map = Cook Islands on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, capital = Avarua

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Avarua

, official_languages =

, lan ...

voted unanimously to reject an offer by New Zealand to be granted independence, and chose instead to become a self-governing Associated State with its residents to remain New Zealand citizens.

*The Pulau Senang prison riot

Pulau Senang is an coral-formed island in the Republic of Singapore, located about off the southern coast of the main island of Singapore. Along with Pulau Pawai to the northwest and Pulau Sudong further behind Pulau Pawai, it is used as a mi ...

took place at the experimental offshore penal colony in Singapore. Superintendent Daniel Dutton and several prison officers were murdered by inmates and the prison was burned to the ground.

*In the Soviet Union, 33 of the 35 persons on Aeroflot Flight 012 were killed when the plane crashed as it was approaching a landing at the Irkutsk Airport in Siberia. The Tupolev Tu-104 had departed Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

in China, bound for Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

, with one scheduled stop in Irkutsk.

* Bob Charles defeated Phil Rodgers

Phil Rodgers (April 3, 1938 – June 26, 2018) was an American professional golfer.

Life

Rodgers was born in San Diego, California. He won the 1958 NCAA Division I Championship while playing at the University of Houston. Immediately afte ...

in a 36-hole playoff to win the British Open

The Open Championship, often referred to as The Open or the British Open, is the oldest golf tournament in the world, and one of the most prestigious. Founded in 1860, it was originally held annually at Prestwick Golf Club in Scotland. Later th ...

. Charles became the first left-handed golfer to win one of golf's major championships.

*The Roman Catholic Diocese of Santiago de Veraguas

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Santiago de Veraguas (erected 13 July 1963) is a suffragan diocese of the Archdiocese of Panamá. Appointed in April 2013, the current bishop is Audilio Aguilar Aguilar.

Current bishop Appointment

On Tuesday, April ...

was erected.

*Died: Blessed Carlos Manuel Rodríguez Santiago

Carlos Manuel Cecilio Rodríguez Santiago, also known as "Blessed Charlie" (22 November 22, 1918 – July 13, 1963), was a Catholic catechist and liturgist who was beatified by Pope John Paul II on April 29, 2001. He is the first Puerto Rican an ...

, 44, first layperson in the history of the United States to be beatified. (cancer)

July 14

Events Pre-1600

* 982 – King Otto II and his Frankish army are defeated by the Muslim army of al-Qasim at Cape Colonna, Southern Italy.

* 1223 – Louis VIII becomes King of France upon the death of his father, Philip II.

* 142 ...

, 1963 (Sunday)

*U.S. Undersecretary of State W. Averell Harriman arrived in Moscow in order to negotiate the nuclear test ban treaty, and brought with him three tons of American telephone and telex equipment to set up the Moscow–Washington hotline

The Moscow–Washington hotline (formally known in the United States as the Washington–Moscow Direct Communications Link; rus, Горячая линия Вашингтон — Москва, r=Goryachaya liniya Vashington–Moskva) is a system t ...

agreed upon by the Americans and Soviets on June 20.

*France's Jacques Anquetil

Jacques Anquetil (; 8 January 1934 – 18 November 1987) was a French road racing cyclist and the first cyclist to win the Tour de France five times, in 1957 and from 1961 to 1964.

He stated before the 1961 Tour that he would gain the ye ...

won the 50th Tour de France.

*Died: Sivananda Saraswati

Sivananda Saraswati (or Swami Sivananda; 8 September 1887 – 14 July 1963) was a yoga guru, a Hindu spiritual teacher, and a proponent of Vedanta. Sivananda was born Kuppuswami in Pattamadai, in the Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu. He stu ...

, 75, Hindu spiritual leader

July 15

Events Pre-1600

*484 BC – Dedication of the Temple of Castor and Pollux in ancient Rome

* 70 – First Jewish–Roman War: Titus and his armies breach the walls of Jerusalem. ( 17th of Tammuz in the Hebrew calendar).

* 756 – ...

, 1963 (Monday)

*The Kingdom of Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

issued the first round postage stamps

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail), who then affix the stamp to the f ...

in history. The stamps (which were also the first to be made of gold foil

Gold leaf is gold that has been hammered into thin sheets (usually around 0.1 µm thick) by goldbeating and is often used for gilding. Gold leaf is available in a wide variety of karats and shades. The most commonly used gold is 22-kara ...

rather than paper) were designed to commemorate the first gold coins in Polynesia.

*Born: Brigitte Nielsen

Brigitte Nielsen (; born Gitte Nielsen; 15 July 1963) is a Danish actress, model, and singer. She began her career modelling for Greg Gorman and Helmut Newton. She subsequently acted in the 1985 films ''Red Sonja'' and ''Rocky IV'', later retu ...

, Danish model and actress, known for ''Rocky IV'' and ''Beverly Hills Cop II''; in Rødovre

Rødovre is a town in eastern Denmark, seat of the Rødovre Municipality, in the Region Hovedstaden. The town's population 1 January 2019 was 39,907, and in addition 145 persons had no fixed address, which made up a total of 40,052 in the munic ...

*Died: Rear Admiral Gilbert Jonathan Rowcliff, 81, U.S. Navy officer and former Judge Advocate General of the Navy

The Judge Advocate General of the Navy (JAG) is the highest-ranking uniformed lawyer in the United States Department of the Navy. The Judge Advocate General is the principal advisor to the Secretary of the Navy and the Chief of Naval Operations o ...

July 16

Events Pre-1600

* 622 – The beginning of the Islamic calendar.

* 997 – Battle of Spercheios: Bulgarian forces of Tsar Samuel are defeated by a Byzantine army under general Nikephoros Ouranos at the Spercheios River in Greece.

* 1 ...

, 1963 (Tuesday)

*The Peerage Act 1963

The Peerage Act 1963 (c. 48) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that permits women peeresses and all Scottish hereditary peers to sit in the House of Lords and allows newly inherited hereditary peerages to be disclaimed.

Backgro ...

was approved by the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

, 105 to 25. The change of rules, which received royal assent on July 31, cleared the way for hereditary peers within the House of Lords to disclaim their peerages in order to be allowed to run for and take a seat in the elected House of Commons. Tony Benn

Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn (3 April 1925 – 14 March 2014), known between 1960 and 1963 as Viscount Stansgate, was a British politician, writer and diarist who served as a Cabinet minister in the 1960s and 1970s. A member of the Labour Party, ...

, who lost his seat in Commons in 1960 when he inherited the title of Viscount Stansgate and automatically became a member of the House of Lords, disqualified himself under the new law and successfully ran for office under in a by-election.

*At Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

, five men began a 30-day engineering test of life support systems for a crewed space station in The Boeing Company

The Boeing Company () is an American multinational corporation that designs, manufactures, and sells airplanes, rotorcraft, rockets, satellites, telecommunications equipment, and missiles worldwide. The company also provides leasing and product ...

space chamber. Designed and built for NASA's Office of Advanced Research and Technology, the chamber was first in the U.S. to include all life-support equipment for a multi-person, long-duration space mission (including environmental control, waste disposal, and crew hygiene and food techniques). In addition to the life support equipment, a number of crew tests simulated specific problems of spaceflight

Spaceflight (or space flight) is an application of astronautics to fly spacecraft into or through outer space, either with or without humans on board. Most spaceflight is uncrewed and conducted mainly with spacecraft such as satellites in o ...

. Five days into the 30-day test, however, the simulated mission was halted because of a faulty reactor tank.

*Born:

**Phoebe Cates

Phoebe Belle Cates Kline (born July 16, 1963) is an American former actress, known primarily for her roles in films such as ''Fast Times at Ridgemont High'' (1982), ''Gremlins'' (1984) and ''Drop Dead Fred'' (1991).

Early life

Cates was born ...

, American actress; in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

** Fatboy Slim (stage name for Norman Quentin Cook), English musician and record producer; in Bromley

Bromley is a large town in Greater London, England, within the London Borough of Bromley. It is south-east of Charing Cross, and had an estimated population of 87,889 as of 2011.

Originally part of Kent, Bromley became a market town, c ...

, Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

**Paul Hipp

Paul Hipp (born July 16, 1963) is an American actor, singer, songwriter and filmmaker.

Early life

Paul Hipp was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and grew up in Warminster. He left Pennsylvania for New York City immediately after high school, st ...

, American actor and musician; in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

** Srečko Katanec, Slovenian soccer football midfielder with 31 games for the Yugoslav national team, later manager who coached the national teams of five different countries (Slovenia, Macedonia, the United Arab Emirates, Iraq and Uzbekistan); in Ljubljana

Ljubljana (also known by other historical names) is the capital and largest city of Slovenia. It is the country's cultural, educational, economic, political and administrative center.

During antiquity, a Roman city called Emona stood in the are ...

, SR Slovenia, Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

July 17

Events Pre-1600

* 180 – Twelve inhabitants of Scillium (near Kasserine, modern-day Tunisia) in North Africa are executed for being Christians. This is the earliest record of Christianity in that part of the world.

*1048 – Damasu ...

, 1963 (Wednesday)

*For the first time in history, a U.S. federal court issued ordered a change in the size of the legislature of a U.S. state, decreasing the number of seats in the Oklahoma House of Representatives from 120 to 100. The court also ordered a reapportionment of both the House and the state Senate on a strict population basis. The decision was the first to rely on the U.S. Supreme Court case of ''Baker v. Carr

''Baker v. Carr'', 369 U.S. 186 (1962), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that redistricting qualifies as a justiciable question under the Fourteenth Amendment, thus enabling federal courts to hear Fourteen ...

'', decided on March 26, 1962, holding that federal courts could review state legislative apportionment.

*Born: King Letsie III of Lesotho

Letsie III (born Seeiso Bereng; 17 July 1963) is King of Lesotho. He succeeded his father, Moshoeshoe II, who was forced into exile in 1990. His father was briefly restored in 1995 but died in a car crash in early 1996, and Letsie became king ag ...

; as David Mohato Bereng Seeiso in Morija

Morija is a town in western Lesotho, located 35 kilometres south of the capital, Maseru. Morija is one of Lesotho's most important historical and cultural sites, known as the Selibeng sa Thuto— the Well-Spring of Learning. It was the site of the ...

, Basutoland colony

July 18

Events Pre-1600

* 477 BC – Battle of the Cremera as part of the Roman–Etruscan Wars. Veii ambushes and defeats the Roman army.

* 387 BC – Roman- Gaulish Wars: Battle of the Allia: A Roman army is defeated by raiding Gauls, l ...

, 1963 (Thursday)

*Colonel Jassem Alwan

Jassem Alwan ( ar, جاسم علوان, ''Jāsim ʿAlwān'') (born 4 July 1928 – died 3 January 2018 in Cairo) was a prominent colonel in the Syrian Army, particularly during the period of the United Arab Republic (UAR) (1958–1961) when he serv ...

of the Syrian army, backed by financing from President Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

, led an attempt to overthrow the government of Syria in order to establish a pro-Nasser government that would reunite with the United Arab Republic. The coup attempt came only 30 minutes after President Lu'ay al-Atassi

Lu'ay al-Atassi ( ar, لؤي الأتاسي, Luʾay al-ʾAtāsī; 1926 − 24 November 2003) was a senior commander in the Syrian Army and later the President of Syria between 9 March and 27 July 1963.

Early life and career

Atassi was born in H ...

had departed from Damascus on an invitation from President Nasser for a meeting in Egypt. After Alwan seized the Damascus radio station and the Syrian Army headquarters, Interior Minister Amin al-Hafiz

Amin al-Hafiz ( ar, أمين الحافظ, Amīn al-Ḥāfiẓ12 November 1921 – 17 December 2009), also known as Amin Hafez was a Syrian politician, general, and member of the Ba'ath Party who served as the President of Syria from 27 July ...

, "sub-machinegun in hand", directed the Ba'ath Party National Guard on a counterattack and regained control. Hundreds of people were killed in the battle; Alwan was able to escape, but 27 officers who had participated in the coup were executed by firing squad, marking an end of "the time-honoured tradition whereby losers were banished to embassies abroad". President Atassi would resign on July 27 in protest over the brutal treatment of the coup leaders.

*Olympiacos F.C.

Olympiacos Club of Fans of Piraeus ( el, Ολυμπιακός Σ.Φ.Π. ), known simply as Olympiacos or Olympiacos Piraeus, is a Greek professional football club based in Piraeus, Attica. Part of the major multi-sport club Olympiacos CFP ('' ...

won the final of the Greek Cup

The Greek Football Cup ( el, Κύπελλο Ελλάδος Ποδοσφαίρου), commonly known as the Greek Cup or Kypello Elladas is a Greek football competition, run by the Hellenic Football Federation.

The Greek Cup is the second most ...

football competition, 3 to 0 over Pierikos.

*Born: Marc Girardelli

Marc Girardelli (born 18 July 1963) is an Austrian and Luxembourgish former alpine ski racer, a five-time World Cup overall champion who excelled in all five alpine disciplines.

Biography

Born in Lustenau, Austria, Girardelli started skiing at ...

, Austrian Olympic alpine ski racer; in Lustenau

Lustenau (; gsw, Luschnou) is a town in the westernmost Austrian state of Vorarlberg in the district of Dornbirn. It lies on the river Rhine, which forms the border with Switzerland. Lustenau is Vorarlberg's fourth largest town.

Geography

Lust ...

July 19

Events Pre-1600

*AD 64 – The Great Fire of Rome causes widespread devastation and rages on for six days, destroying half of the city.

* 484 – Leontius, Roman usurper, is crowned Eastern emperor at Tarsus (modern Turkey). He is ...

, 1963 (Friday)

*American test pilot

A test pilot is an aircraft pilot with additional training to fly and evaluate experimental, newly produced and modified aircraft with specific maneuvers, known as flight test techniques.Stinton, Darrol. ''Flying Qualities and Flight Testin ...

Joseph A. Walker, flying the X-15

The North American X-15 is a hypersonic rocket-powered aircraft. It was operated by the United States Air Force and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration as part of the X-plane series of experimental aircraft. The X-15 set spee ...

, reached an altitude of , achieving a sub-orbital spaceflight by recognized international standards (which define outer space as beginning above the Earth).

*An artificial heart

An artificial heart is a device that replaces the heart. Artificial hearts are typically used to bridge the time to heart transplantation, or to permanently replace the heart in the case that a heart transplant (from a deceased human or, exper ...

pump was placed inside a human being for the first time, at the Methodist Hospital in Houston, Texas University of Houston by a team led by Dr. Michael E. DeBakey. The unidentified patient survived for four days before dying of complications from pneumonia.

*A bomb was dropped on downtown San Francisco, inadvertently, by a U.S. Navy Reserve

The United States Navy Reserve (USNR), known as the United States Naval Reserve from 1915 to 2005, is the Reserve components of the United States Armed Forces, Reserve Component (RC) of the United States Navy. Members of the Navy Reserve, called R ...

pilot on a routine exercise flight. The unarmed bomb fell at the intersection of Market Street and Front Street, bounced over the eight-story tall IBM building and damaged another building three blocks away, but nobody was injured.

*Died: Guy Scholefield

Guy Hardy Scholefield (17 June 1877 – 19 July 1963) was a New Zealand journalist, historian, archivist, librarian and editor, known primarily as the compiler of the 1940 version of the '' Dictionary of New Zealand Biography''.

Early life

Sc ...

, 86, New Zealand archivist who compiled the ''Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

The ''Dictionary of New Zealand Biography'' (DNZB) is an encyclopedia or biographical dictionary containing biographies of over 3,000 deceased New Zealanders. It was first published as a series of print volumes from 1990 to 2000, went online ...

''

July 20

Events Pre-1600

* 70 – Siege of Jerusalem: Titus, son of emperor Vespasian, storms the Fortress of Antonia north of the Temple Mount. The Roman army is drawn into street fights with the Zealots.

* 792 – Kardam of Bulgaria defea ...

, 1963 (Saturday)

*An attempt to reconcile the differences between the Soviet Communist Party and the Chinese Communist Party ended in failure, after more than a week of conferences in Moscow.

*The first Yaoundé Convention was signed in the capital of Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

by 18 African nations that had gained independence relatively recently. It would take effect on June 1, 1964, and be operative for five years. Parties to the agreement were Burundi, Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

, the Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR; ; , RCA; , or , ) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the DR Congo to the south, the Republic of th ...

, Chad, the Republic of the Congo (Brazzaville), the Republic of the Congo (Leopoldville)

The Republic of the Congo (french: République du Congo, ln, Republíki ya Kongó), also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply either Congo or the Congo, is a country located in the western coast of Central Africa to the w ...

, Dahomey, Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the nort ...

, the Ivory Coast, the Malagasy Republic, Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mal ...

, Mauritania, Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagesRwanda,

Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

, Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

, Togo

Togo (), officially the Togolese Republic (french: République togolaise), is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north. It extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its c ...

, and Upper Volta. After the expiration on May 31, 1969, a new convention would be signed at Yaoundé

Yaoundé (; , ) is the capital of Cameroon and, with a population of more than 2.8 million, the second-largest city in the country after the port city Douala. It lies in the Centre Region of the nation at an elevation of about 750 metres (2,50 ...

on July 29 of that year.

*For the first time since June 30, 1954, a total solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of the Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six month ...

was visible from North America and was "the most scientifically observed eclipse in history" up to that time. A chartered DC-8 jet airplane flew a group of astronomers along the path of the eclipse so that the totality could be observed for 44 seconds longer than for people on the ground. The point of greatest eclipse was in Canada's Northwest Territory, near its border with Alberta.

*The sinking of the British ore carrier freighter ''Tritonica'' killed 33 of its 42-member crew after it collided with another British ship, the ''Roonagh Head'', and went down within four minutes in the St Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

in Canada near Petite-Rivière-Saint-François

Petite-Rivière-Saint-François is a municipality in Quebec, Canada, along the Saint Lawrence River. It is considered the gateway to the Charlevoix region.

It is named after the Petite rivière Saint-François, and home to Le Massif ski resort. ...

, Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

. Most of the ''Tritonica'' crew had been sleeping when the ships collided at 3:00 in the morning and were unable to escape in time.

* Mary Mills won the 1963 U.S. Women's Open in golf.

*Su Mac Lad won the International Trot

The International Trot is a harness racing event held in the New York City area that aimed to appeal to a mix of United States and international entrants. The inaugural event was held at Roosevelt Raceway in Westbury, New York in 1959, and was he ...

harness racing event on Long Island, bringing his career winnings to $687,549, the most of any pacer or trotter as of that date.

July 21

Events Pre-1600

* 356 BC – The Temple of Artemis in Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, is destroyed by arson.

* 230 – Pope Pontian succeeds Urban I as the eighteenth pope. After being exiled to Sardinia, he became t ...

, 1963 (Sunday)

* Jack Nicklaus, 23, described in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' as "a young man who has achieved more in 13 months than most golfers do in a life-time", won the Professional Golf Association championship. In the 72-hole tournament, held in Dallas

Dallas () is the List of municipalities in Texas, third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of metropolitan statistical areas, fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 ...

and one of the professional golf major competitions, Nicklaus had a score of 279, two strokes ahead of runner-up Dave Ragan, who finished at 281. Nicklaus had won the 1962 U.S. Open on June 17, 1962, in only his 17th game on the PGA Tour, and the 1963 Masters Tournament

The 1963 Masters Tournament was the 27th Masters Tournament, held April 4–7 at Augusta National Golf Club in Augusta, Georgia. 84 players entered the tournament and 50 made the cut at eight-over-par (152).

Jack Nicklaus, 23, won the first of h ...

on April 7.

*NASA announced that Dr. George Mueller would succeed D. Brainerd Holmes as the head of the Apollo program.

*Died: Ray Platte, 37, American stock car driver, died of a skull fracture sustained the previous day during a 100-lap NASCAR race at the speedway

Speedway may refer to:

Racing Race tracks

*Edmonton International Speedway, also known as Speedway Park, a former motor raceway in Edmonton, Alberta

*Indianapolis Motor Speedway, a motor raceway in Speedway, Indiana

Types of races and race cours ...

in South Boston, Virginia

South Boston, formerly Boyd's Ferry, is a town in Halifax County, Virginia, United States. The population was 8,142 at the 2010 census, down from 8,491 at the 2000 census. It is the most populous town in Halifax County.

History

On December ...

.

July 22

Events Pre-1600

* 838 – Battle of Anzen: The Byzantine emperor Theophilos suffers a heavy defeat by the Abbasids.

*1099 – First Crusade: Godfrey of Bouillon is elected the first Defender of the Holy Sepulchre of The Kingdom of J ...

, 1963 (Monday)

*Sarawak

Sarawak (; ) is a state of Malaysia. The largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia, Sarawak is located in northwest Borneo Island, and is bordered by the Malaysian state of Sabah to the northeast, ...

was granted conditional independence from the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

pending the establishment of the Federation of Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federation, federal constitutional monarchy consists of States and federal territories of Malaysia, thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two r ...

.

*World heavyweight boxing champion Sonny Liston retained his title in a rematch fight against former champion Floyd Patterson

Floyd Patterson (January 4, 1935 – May 11, 2006) was an American professional boxer who competed from 1952 to 1972, and twice reigned as the world heavyweight champion between 1956 and 1962. At the age of 21, he became the youngest boxer in hi ...

, whom he had defeated ten months earlier, on September 20, 1962. In the first bout, he knocked out Patterson in the first round in two minutes, six seconds. In the rematch at Las Vegas

Las Vegas (; Spanish for "The Meadows"), often known simply as Vegas, is the 25th-most populous city in the United States, the most populous city in the state of Nevada, and the county seat of Clark County. The city anchors the Las Vegas ...

, Liston took four seconds longer.

*''Please Please Me

''Please Please Me'' is the debut studio album by the English rock band the Beatles. Produced by George Martin, it was released on EMI's Parlophone label on 22 March 1963 in the United Kingdom, following the success of the band's first two s ...

'' became the first record album by The Beatles

The Beatles were an English rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the most influential band of all time and were integral to the developmen ...

to be released in the United States. Vee Jay Records deleted two of the songs that had appeared on the British version introduced on March 22

Events Pre-1600

* 106 – Start of the Bostran era, the calendar of the province of Arabia Petraea.

* 235 – Roman emperor Severus Alexander is murdered, marking the start of the Crisis of the Third Century.

* 871 – Æthelr ...

, including the title song, "Please Please Me".

July 23

Events Pre-1600

* 811 – Byzantine emperor Nikephoros I plunders the Bulgarian capital of Pliska and captures Khan Krum's treasury.

*1319 – A Knights Hospitaller fleet scores a crushing victory over an Aydinid fleet off Chios. 1 ...

, 1963 (Tuesday)

* The Supreme Court of East Germany

The Supreme Court of the German Democratic Republic (german: Oberstes Gericht der DDR) was the highest judicial organ of the GDR. It was set up in 1949 and was housed on Scharnhorststraße 6 in Berlin. The building now houses the district cour ...

sentenced Hans Globke

Hans Josef Maria Globke (10 September 1898 – 13 February 1973) was a German administrative lawyer, who worked in the Prussian and Reich Ministry of the Interior in the Reich, during the Weimar Republic and the time of National Socialism and wa ...

''in absentia

is Latin for absence. , a legal term, is Latin for "in the absence" or "while absent".

may also refer to:

* Award in absentia

* Declared death in absentia, or simply, death in absentia, legally declared death without a body

* Election in ab ...

'' to life imprisonment "for continued war crimes committed with complicity and crimes against humanity in partial combination with murder".

* A modified prototype Super Frelon helicopter broke the FAI absolute helicopter world speed record, attaining a maximum speed of during the flight.

July 24

Events Pre-1600

*1132 – Battle of Nocera between Ranulf II of Alife and Roger II of Sicily.

* 1148 – Louis VII of France lays siege to Damascus during the Second Crusade.

*1304 – Wars of Scottish Independence: Fall of Stirl ...

, 1963 (Wednesday)

*John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, the 35th U.S. President, hosted a group of American high school students who were part of the Boys Nation event sponsored by the American Legion, including 16-year-old Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

, who would become the 42nd U.S. President in 1993. Clinton would later use a film clip of him shaking hands with Kennedy as part of his 1992 campaign.

*Victor Marijnen

Victor Gerard Marie Marijnen (21 February 1917 – 5 April 1975) was a Dutch politician of the defunct Catholic People's Party (KVP) now the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) party and jurist who served as Prime Minister of the Netherlands from 2 ...

became the new Prime Minister of the Netherlands

The prime minister of the Netherlands ( nl, Minister-president van Nederland) is the head of the executive branch of the Government of the Netherlands. Although the monarch is the ''de jure'' head of government, the prime minister ''de facto'' ...