Islamic history of Yemen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Islam came to Yemen around 630 during

The

The

The Sulayhids, unlike the aforementioned regimes, were native Yemenis. The founder of the regime was Ali as-Sulayhi (d. 1067) who propagated Ismaili doctrines and established a state in the highlands in 1047. He took the Tihama lowland from the Najahids in 1060 and subjugated the important coastal entrepôt

The Sulayhids, unlike the aforementioned regimes, were native Yemenis. The founder of the regime was Ali as-Sulayhi (d. 1067) who propagated Ismaili doctrines and established a state in the highlands in 1047. He took the Tihama lowland from the Najahids in 1060 and subjugated the important coastal entrepôt

The

The

The imam

The imam

U.S. State Dept. Country Study

* (1): DAUM, W. (ed.): ''Yemen. 3000 years of art and civilisation in Arabia Felix''., Innsbruck / Frankfurt am Main / Amsterdam [1988]. pp. 53–4. *

A Dam at Marib

*

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

's lifetime and the rule of the Persian governor Badhan. Thereafter, Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

was ruled as part of Arab-Islamic caliphates, and became a province in the Islamic empire

This article includes a list of successive Islamic states and Muslim dynasties beginning with the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad (570–632 CE) and the early Muslim conquests that spread Islam outside of the Arabian Peninsula, and continuin ...

.

Regimes affiliated to the Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

ian Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dy ...

caliphs occupied much of northern and southern Yemen throughout the 11th century, including the Sulayhids and Zurayids

The Zurayids (بنو زريع, Banū Zuraiʿ), were a Yamite Hamdani dynasty based in Yemen in the time between 1083 and 1174. The centre of its power was Aden. The Zurayids suffered the same fate as the Hamdanid sultans, the Sulaymanids and ...

, but the country was rarely unified for any long period of time. Local control in the Middle Ages was exerted by a succession of families which included the Ziyadids

The Ziyadid dynasty () was a Muslim dynasty that ruled western Yemen from 819 until 1018 from the capital city of Zabid. It was the first dynastic regime to wield power over the Yemeni lowland after the introduction of Islam in about 630.

The e ...

(818–1018), the Najahids

Najahid dynasty ( ar, بنو نجاح; Banū Najāḥ) was a slave dynasty of Abyssinian origin founded in Zabid in the Tihama (lowlands) region of Yemen around 1050 AD.

They faced hostilities from the Highlands dynasties of the time, chiefly ...

(1022–1158), the Egyptian Ayyubids

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladin ...

(1174–1229) and the Turkoman Rasulid

The Rasulids ( ar, بنو رسول, Banū Rasūl) were a Sunni Muslim dynasty who ruled Yemen from 1229 to 1454.

History

Origin of the Rasulids

The Rasulids took their name from al-Amin's nickname "Rasul". The Zaidi Shi'i Imams of Yemen we ...

s (1229–1454). The most long-lived, and for the future most important polity, was founded in 897 by Yayha bin Husayn bin Qasim ar-Rassi. They were the Zaydis

Zaydism (''h'') is a unique branch of Shia Islam that emerged in the eighth century following Zayd ibn Ali‘s unsuccessful rebellion against the Umayyad Caliphate. In contrast to other Shia Muslims of Twelver Shi'ism and Isma'ilism, Zaydis, ...

of Sa'dah

Saada ( ar, صَعْدَة, translit=Ṣaʿda), a city and ancient capital in the northwest of Yemen, is the capital and largest city of the province of the same name, and the county seat of the county of the same name. The city is located in the ...

in the highlands of North Yemen

North Yemen may refer to:

* Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen (1918–1962)

* Yemen Arab Republic

The Yemen Arab Republic (YAR; ar, الجمهورية العربية اليمنية '), also known simply as North Yemen or Yemen (Sanaʽa), was a ...

, headed by imam

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, ser ...

s of various Sayyid

''Sayyid'' (, ; ar, سيد ; ; meaning 'sir', 'Lord', 'Master'; Arabic plural: ; feminine: ; ) is a surname of people descending from the Prophets in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad through his grandsons, Hasan ibn Ali and Husayn ibn Ali ...

lineages. As ruling Imams of Yemen

The Imams of Yemen, later also titled the Kings of Yemen, were religiously consecrated leaders belonging to the Zaidiyyah branch of Shia Islam. They established a blend of religious and temporal-political rule in parts of Yemen from 897. Their i ...

, they established a Shia

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that the Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad designated Ali, ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his S ...

theocratic

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fro ...

political structure that survived with some intervals until 1962.

After the introduction of coffee

Coffee is a drink prepared from roasted coffee beans. Darkly colored, bitter, and slightly acidic, coffee has a stimulant, stimulating effect on humans, primarily due to its caffeine content. It is the most popular hot drink in the world.

S ...

in the 16th century the town of al-Mukha (Mocha), on the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

coast, became the most important coffee port in the world. For a period after 1517, and again in the 19th century, Yemen was a nominal part of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, although on both occasions the Zaydi Imams contested the power of the Turks and eventually expelled them.

Final years of pre-Islamic Yemen and arrival of Islam

In the final pre-Islamic period, the Yemeni lands included the large tribal confederationsHimyar

The Himyarite Kingdom ( ar, مملكة حِمْيَر, Mamlakat Ḥimyar, he, ממלכת חִמְיָר), or Himyar ( ar, حِمْيَر, ''Ḥimyar'', / 𐩹𐩧𐩺𐩵𐩬) (fl. 110 BCE–520s CE), historically referred to as the Homerite ...

, Hamdan, Madh'hij

Madhḥij ( ar, مَذْحِج) is a large Qahtanite Arab tribal confederation. It is located in south and central Arabia. This confederation participated in the early Muslim conquests and was a major factor in the conquest of the Persian empire ...

, Kindah

Kinda or Kindah may refer to:

Politics and society

*Kinda (tribe), an ancient and medieval Arab tribe

*Kingdom of Kinda, a tribal kingdom in north and central Arabia in –

Places

* Kinda, Idlib, Syria

* Kinda Hundred, a hundred in Sweden

* Ki ...

, Hashid

The Hashid ( ar, حاشد; Musnad: 𐩢𐩦𐩵𐩣) is a tribal confederation in Yemen. It is the second or third largest – after Bakil and, depending on sources, Madh'hij

, Bakil

The Bakil ( ar, بكيل, Musnad: 𐩨𐩫𐩺𐩡) federation is the largest tribal federation in Yemen. The tribe consists of more than 10 million men and women they are the sister tribe of Hashid(4 million) whose leader was Abdullah Bin Hussein ...

, and Azd

The Azd ( ar, أَزْد), or ''Al-Azd'' ( ar, ٱلْأَزْد), are a Tribes of Arabia, tribe of Sabaeans, Sabaean Arabs.

In ancient times, the Sabaeans inhabited Ma'rib, capital city of the Sabaeans, Kingdom of Saba' in modern-day Yemen. Th ...

.

During the 6th century, the Yemen was involved in the power struggles between the Christian Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and the Zoroastrian Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

. Following persecutions of Christians by the Jewish Himyarites, in 525 the Christian Aksumite Empire

The Kingdom of Aksum ( gez, መንግሥተ አክሱም, ), also known as the Kingdom of Axum or the Aksumite Empire, was a kingdom centered in Northeast Africa and South Arabia from Classical antiquity to the Middle Ages. Based primarily in wh ...

, a Byzantine ally, occupied Yemen. In turn, local tribal leaders turned to the Sasanians for aid, who in 575, finally took over the region and converted it into a province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''Roman province, provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire ...

of the Sasanian Empire. The descendants of these Persian soldiers, known in Arabic as , dominated Sana'a

Sanaa ( ar, صَنْعَاء, ' , Yemeni Arabic: ; Old South Arabian: 𐩮𐩬𐩲𐩥 ''Ṣnʿw''), also spelled Sana'a or Sana, is the capital and largest city in Yemen and the centre of Sanaa Governorate. The city is not part of the Governo ...

, but the rest of the country remained divided in practice among a multitude of local rulers and tribal chiefs. After the dissolution of Persian rule in South Arabia, the turned to the emerging Islamic state in order to find support against local Arab rebels.

The final Persian governor, Badhan, converted to Islam on 6 AH (628 CE), thus nominally submitting the entirety of Yemen to the new faith. The actual extent of conversion is not known, and the scarcity and lack of detail in the sources is exacerbated by the retroactive attempts, in later sources, by each group to provide an early conversion date for itself for reasons of prestige. In practice, the land remained much like it had been in pre-Islamic times, and the new religion became another factor in the internal conflicts that afflicted Yemeni society since old. A certain al-Aswad al-Ansi proclaimed himself prophet in 632 and found widespread support among the Yemenis, although the exact motivation of his uprising is unclear. He captured Sana'a, but was killed by the and defecting members of his own faction in the same year.

Yemen as a province of the early caliphates

Rashidun era (632–661)

The firstRashidun

, image = تخطيط كلمة الخلفاء الراشدون.png

, caption = Calligraphic representation of Rashidun Caliphs

, birth_place = Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia present-day Saudi Arabia

, known_for = Companions of t ...

caliph, Abu Bakr

Abu Bakr Abdallah ibn Uthman Abi Quhafa (; – 23 August 634) was the senior companion and was, through his daughter Aisha, a father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, as well as the first caliph of Islam. He is known with the honor ...

, sent troops from Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

into the region, and levied local forces to augment them. This allowed Muslim rule to survive the Wars of Apostasy that afflicted the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate ...

in 632–633 following the death of Muhammad. Many of the apostate leaders were pardoned and went on to play important roles in the early Muslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

.

Under the Rashidun caliphs, the first governors were sent to Yemen. The lists of governors are often unclear and contradictory, but represent almost the only information about the early history of Islamic Yemen. Governors are mentioned for the entirety of the Yemen, but also individually for Sana'a, al-Janad (based at Taiz

Taiz ( ar, تَعِزّ, Taʿizz) is a city in southwestern Yemen. It is located in the Yemeni Highlands, near the port city of Mocha, Yemen, Mocha on the Red Sea, at an elevation of about above sea level. It is the capital of Taiz Governorate. W ...

), and Hadramawt

Hadhramaut ( ar, حَضْرَمَوْتُ \ حَضْرَمُوتُ, Ḥaḍramawt / Ḥaḍramūt; Hadramautic: 𐩢𐩳𐩧𐩣𐩩, ''Ḥḍrmt'') is a region in South Arabia, comprising eastern Yemen, parts of western Oman and southern Saud ...

. The governor of Sana'a appears to have at times exercised some control over the others, but even so their authority was often limited to the cities they were based in, and most of the country remained outside effective control. The early governors were usually chosen from senior Companions of Muhammad

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregiv ...

. The last of them, Ya'la ibn Umayya, served for twenty years and was only dismissed by the fourth Rashidun caliph, Ali

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam ...

.

The Rashidun caliphs also paid some attention to the affairs of Yemen, especially the spread of Islam. Judges and Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing. ...

instructors were appointed, and the Christian tribes of Najran evicted under Caliph Umar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate o ...

, despite prior treaties with Muhammad and Abu Bakr guaranteeing their status. The Jewish population was allowed to remain against the payment of the jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent Kafir, non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Sharia, Islamic law. The jizya tax has been unde ...

(poll tax).

The main events of the First Muslim Civil War

The First Fitna ( ar, فتنة مقتل عثمان, fitnat maqtal ʻUthmān, strife/sedition of the killing of Uthman) was the first civil war in the Islamic community. It led to the overthrow of the Rashidun Caliphate and the establishment of t ...

(656-661) took place far from Yemen, but the country was nevertheless deeply affected. Yemenis were divided between the rival camps of Ali and Mu'awiya I

Mu'awiya I ( ar, معاوية بن أبي سفيان, Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān; –April 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the deat ...

, and both sides sent their own troops into the country. Ali's partisans initially prevailed, but one of Mu'awiya's generals captured Najran

Najran ( ar, نجران '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia near the border with Yemen. It is the capital of Najran Province. Designated as a new town, Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom; its population has risen fr ...

and Sana'a for his master in 660.

Umayyad era (661–750)

Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

, founded by Mu'awiya, shifted their base outside the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate ...

, but continued to pay great attention to Yemen. Governors were appointed directly by the caliph. During certain periods, Yemen was administratively grouped together with Hijaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provinc ...

and Yamama. Still, the caliphal governors' actual control barely extended to the wider country, where the pre-Islamic elites still retained their position.

During most of the Second Muslim Civil War

The Second Fitna was a period of general political and military disorder and civil war in the Islamic community during the early Umayyad Caliphate., meaning trial or temptation) occurs in the Qur'an in the sense of test of faith of the believer ...

(683–692), Yemen was nominally under the control of the Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red ...

-based anti-caliph, Abdallah ibn al-Zubayr

Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr ibn al-Awwam ( ar, عبد الله ابن الزبير ابن العوام, ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr ibn al-ʿAwwām; May 624 CE – October/November 692), was the leader of a caliphate based in Mecca that rivaled the ...

. However, his control over the country was tenuous, judging from the frequent alternation of governors during his rule. Ibn al-Zubayr's tenuous authority was not enough to protect Sana'a against the thret of the Kharijites

The Kharijites (, singular ), also called al-Shurat (), were an Islamic sect which emerged during the First Fitna (656–661). The first Kharijites were supporters of Ali who rebelled against his acceptance of arbitration talks to settle the ...

of Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of t ...

and Bahrayn

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ad ...

: in 686, the city had to bribe them not to attack, and in the next year, its inhabitants were forced to swear allegiance to the Kharijite leader, Najda ibn Amir

Najda ibn Amir al-Hanafi ( ar, نجدة بن عامر الحنفي, Najda ibn ʿĀmir al-Ḥanafī; ) was the head of a breakaway Khawarij, Kharijite state in central and eastern Arabia between 685 and his death at the hands of his own partisans. H ...

. Following the victory of the Marwanid branch of the Umayyads in the civil war, Sana'a surrendered to an Umayyad army without resistance.

The Marwanid caliphs made considerable investments in the country's infrastructure, leading to an upsurge in prosperity. As elsewhere in the Muslim world, Caliph Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz

Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz ( ar, عمر بن عبد العزيز, ʿUmar ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz; 2 November 680 – ), commonly known as Umar II (), was the eighth Umayyad caliph. He made various significant contributions and reforms to the society, and ...

gained a reputation for justice that carried over even into the local Shi'a traditions.

In spite of the tenuous caliphal authority, the Yemenis seldom rebelled against the Umayyads. A certain Abbad al-Ru'yani revolted in 725/6, but his motivation is unclear: according to some sources, he was a Himyarite self-proclaimed messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

, while others consider him a Kharijite. The most serious revolt occurred at the end of the dynasty, in 745–747, as Umayyad power was weakened during the Third Muslim Civil War

The Third Fitna ( ar, الفتنة الثاﻟﺜـة, al-Fitna al-thālitha), was a series of civil wars and uprisings against the Umayyad Caliphate beginning with the overthrow of Caliph al-Walid II in 744 and ending with the victory of Marwan ...

. It was headed by a Kindi tribesman, Abdallah ibn Yahya, who assumed the laqab

Arabic language names have historically been based on a long naming system. Many people from the Arabic-speaking and also Muslim countries have not had given/ middle/family names but rather a chain of names. This system remains in use throughout ...

of Talib al-Haqq Abdallah ibn Yahya, better known by his laqab of Talib al-Haqq (), was the leader of an Ibadi revolt against the Umayyad Caliphate in southern Arabia during the Third Fitna.

He was of Kinda (tribe), Kindaite origin, and had originally been appointe ...

(), and proclaimed himself caliph in the Hadramawt. With support from the Ibadi

The Ibadi movement or Ibadism ( ar, الإباضية, al-Ibāḍiyyah) is a school of Islam. The followers of Ibadism are known as the Ibadis.

Ibadism emerged around 60 years after the Islamic prophet Muhammad's death in 632 AD as a moderate sc ...

Kharijites of neighbouring Oman, he advanced onto Sana'a. His army occupied Mecca and Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

, and even Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is hand ...

for a while swore allegiance to him, before his uprising, as well as other tribal revolts of the Himyarites, were suppressed by the Umayyad general Abd al-Malik ibn Atiyya. However, the Ibadis of Hadramawt on that occasion obtained from Ibn al-Atiyya the right to choose their own governors, a privilege they kept for about a generation.

Abbasid era (750–847)

The Third Muslim Civil War fatally weakened the Umayyad regime, culminating in theAbbasid Revolution

The Abbasid Revolution, also called the Movement of the Men of the Black Raiment, was the overthrow of the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE), the second of the four major Caliphates in early History of Islam, Islamic history, by the third, the A ...

, and the overthrow of the Umayyad Caliphate by the Abbasids

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

in 749–750.

The Abbasids continued the policy of the Umayyads with respect to Yemen. Frequently, members of the highest Abbasid aristocracy, including princes of the dynasty, served as governors. At other times, the province was attached to the Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provin ...

, whose governor sent a deputy to rule in his stead. In 759, the Abbasid governor, a Yemeni named Abdallah ibn Abd al-Madan, tried to secede from the Caliphate. His revolt was suppressed by the Abbasid general Ma'n ibn Za'ida al-Shaybani, who went on to serve as governor of Yemen until 768. During his tenure, he "pacified the country brutally but successfully", suppressing uprisings—mainly Ibadi-inspired—across the country.

Under Caliph Harun al-Rashid

Abu Ja'far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi ( ar

, أبو جعفر هارون ابن محمد المهدي) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (; or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid ( ar, هَارُون الرَشِيد, translit=Hārūn ...

(, Muhammad ibn Khalid ibn Barmak, one of the famous Barmakids

The Barmakids ( fa, برمکیان ''Barmakiyân''; ar, البرامكة ''al-Barāmikah''Harold Bailey, 1943. "Iranica" BSOAS 11: p. 2. India - Department of Archaeology, and V. S. Mirashi (ed.), ''Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era'' vol ...

, was governor of Yemen. His time is recorded as one of prosperity for Sana'a, but also of widespread poverty. In 800, the Himyarite chieftain al-Haysam ibn Abd al-Samad rose in revolt, but was defeated by Harun's governor Hammad al-Barbari. Hammad was successful in restoring tranquility to the region and securing the trade routes, but his harshness towards the local population led to his recall in 810.

During the civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

between al-Amin

Abu Musa Muhammad ibn Harun al-Rashid ( ar, أبو موسى محمد بن هارون الرشيد, Abū Mūsā Muḥammad ibn Hārūn al-Rashīd; April 787 – 24/25 September 813), better known by his laqab of Al-Amin ( ar, الأمين, al-Amī ...

and al-Ma'mun

Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid ( ar, أبو العباس عبد الله بن هارون الرشيد, Abū al-ʿAbbās ʿAbd Allāh ibn Hārūn ar-Rashīd; 14 September 786 – 9 August 833), better known by his regnal name Al-Ma'mu ...

, Yemen initially belonged to al-Amin's camp, but one of al-Ma'mun's agents, Yazid ibn Jarir, managed to win the country over to his master. In 815, Ibrahim ibn Musa al-Kazim, brother of the well-known Alid Ali al-Ridha

Ali ibn Musa al-Rida ( ar, عَلِيّ ٱبْن مُوسَىٰ ٱلرِّضَا, Alī ibn Mūsā al-Riḍā, 1 January 766 – 6 June 818), also known as Abū al-Ḥasan al-Thānī, was a descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and the e ...

, occupied Sana'a and the northern highlands and struck coins in his own name. He may even have briefly captured Mecca, but was defeated by Abbasid forces near Sana'a in the same year. Nevertheless, after the caliph had reached an understanding with the Alids and appointed Ali al-Ridha as his heir-apparent, the same Ibrahim ibn Musa was appointed governor of Mecca and Yemen in 820. This resulted in a revolt by the incumbent governor, Hamdawayh, who had to be subdued by yet another expedition. Ibrahim remained as governor of Yemen until 828.

Direct Abbasid authority in Yemen survived until 847, when the autonomous Yu'firid dynasty

The Yuʿfirids ( ar, بنو يعفر, Banū Yuʿfir) were an Islamic Hemyariite dynasty that held power in the highlands of Yemen from 847 to 997. The name of the family is often incorrectly rendered as "Yafurids". They nominally acknowledged the ...

defeated the Abbasid governor, Himyar ibn al-Harith, and captured Sana'a. Already during al-Ma'mun's time, however, local tribal or sectarian leaders began to rise and unite hitherto fragmented parts of the country under their authority, a process that would continue during the entire 9th century.

Yemeni textiles, long recognized for their fine quality, maintained their reputation and were exported for use by the Abbasid elite, including the caliphs themselves. The products of Sana'a and Aden

Aden ( ar, عدن ' Yemeni: ) is a city, and since 2015, the temporary capital of Yemen, near the eastern approach to the Red Sea (the Gulf of Aden), some east of the strait Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000 people. ...

have been particularly important in the East-West textile trade.

Collapse of Abbasid authority and rise of native dynasties

The first local dynasty to emerge in the 9th century were theZiyadids

The Ziyadid dynasty () was a Muslim dynasty that ruled western Yemen from 819 until 1018 from the capital city of Zabid. It was the first dynastic regime to wield power over the Yemeni lowland after the introduction of Islam in about 630.

The e ...

. The dynasty was established by Muhammad ibn Abdallah ibn Ziyad, a descendant of the Umayyad dynasty

Umayyad dynasty ( ar, بَنُو أُمَيَّةَ, Banū Umayya, Sons of Umayya) or Umayyads ( ar, الأمويون, al-Umawiyyūn) were the ruling family of the Caliphate between 661 and 750 and later of Al-Andalus between 756 and 1031. In the ...

, who was appointed by al-Ma'mun in 817 to suppress revolts in the western coastal plain of the Tihama

Tihamah or Tihama ( ar, تِهَامَةُ ') refers to the Red Sea coastal plain of the Arabian Peninsula from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Bab el Mandeb.

Etymology

Tihāmat is the Proto-Semitic language's term for 'sea'. Tiamat (or Tehom, in m ...

. In 819, Ibn Ziyad founded Zabid

Zabid ( ar, زَبِيد) (also spelled Zabīd, Zabeed and Zebid) is a town with an urban population of around 52,590 people on Yemen's western coastal plain. It is one of the oldest towns in Yemen, and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since ...

as his capital. At the height of the dynasty, its power extended along the coasts to Aden

Aden ( ar, عدن ' Yemeni: ) is a city, and since 2015, the temporary capital of Yemen, near the eastern approach to the Red Sea (the Gulf of Aden), some east of the strait Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000 people. ...

in the south and Mirbat

Mirbat ( ar, مرباط) is a coastal town in the Dhofar governorate, in southwestern Oman. It was the site of the 1972 Battle of Mirbat between Communist guerrillas on one side and the armed forces of the Sultan of Oman and their Special Air Se ...

in the west, and Zabid was so prosperous as to be known as 'Baghdad of the Yemen'. Unlike the rest of the country, where Shi'a

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that the Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad designated Ali, ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his S ...

sympathies were strong, the Tihama was solidly pro-Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

, and the Ziyadid dynasty remained aligned with the Sunni Abbasids against the Shi'a regimes that arose during the late 9th century.

Unlike the Ziyadids, who at least in the beginning ruled with the sanction of the Abbasids, in other parts of Yemen, local dynasties arose in opposition to Abbasid rule. In the south, the Himyarite Manakhi dynasty took control of the southern highlands in 829. At the same time, in the central highlands the Himyarite Yu'firid dynasty

The Yuʿfirids ( ar, بنو يعفر, Banū Yuʿfir) were an Islamic Hemyariite dynasty that held power in the highlands of Yemen from 847 to 997. The name of the family is often incorrectly rendered as "Yafurids". They nominally acknowledged the ...

took power, based at Shibam

Shibam Hadramawt ( ar, شِبَام حَضْرَمَوْت, Shibām Ḥaḍramawt) is a town in Yemen. With about 7,000 inhabitants, it is the seat of the District of Shibam in the Governorate of Hadhramaut. Known for its mudbrick-made high-r ...

, northwest of Sana'a. After twenty years of warfare its founder, Yu'fir ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Hiwali, captured Sana'a in 847. In the following years, their power extended into the northern highlands, to the south up to Janad, and east into Hadramawt. As Sunnis, their rule was recognized by the Abbasids in 870, although the Yu'firids were often tributary to their Ziyadid neighbours. Ziyadid power collapsed rapidly in 882, after the murder of Yu'fir's two sons in the mosque of Shibam provoked widespread rebellions against their rule. The Abbasids sent Ali ibn al-Husayn as governor, and his tenure in 892–895 managed to stabilise the situation around Sana'a.

Rise of sectarian regimes

By the 890s, Yemen was politically divided between the three major local dynasties, the Ziyadids, and Yu'firids, and Manakhis, as well as a host of constantly quarreling minor tribal leaders, especially in the north. The lack of political unity, the remoteness of the province and its inaccessible terrain, along with deep-rooted Shi'a sympathies in the local population, made Yemen "manifestly fertile territory for any charismatic leader equipped with tenacity and political acumen to realise his ambitions". This was realized with the arrival of agents of two rival Shi'a sects, theZaydis

Zaydism (''h'') is a unique branch of Shia Islam that emerged in the eighth century following Zayd ibn Ali‘s unsuccessful rebellion against the Umayyad Caliphate. In contrast to other Shia Muslims of Twelver Shi'ism and Isma'ilism, Zaydis, ...

and the Isma'ilis

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor ( imām) to Ja'far al- ...

.

Early Isma'ili activity

Isma'ili activity in Yemen is first recorded around the mid-9th century, in the southern highlands aroundMudhaykhirah

Mudhaykhirah () is a village in southwestern Yemen. It is administratively a part of the Mudhaykhirah subdistrict in Mudhaykhirah District, Ibb Governorate. The village had a population of 1,245 according to the 2004 census.

History

Various accou ...

, the Manakhi capital. It was led by a certain al-Hadan ibn Faraj al-Sanadiqi, but the few details that are known derive from later sources and record simply that he "pretended to be a prophet, committed many atrocities, and was the cause of a massive emigration".

Far better known are the careers of the two Isma'ili missionaries (s), the Kufa

Kufa ( ar, الْكُوفَة ), also spelled Kufah, is a city in Iraq, about south of Baghdad, and northeast of Najaf. It is located on the banks of the Euphrates River. The estimated population in 2003 was 110,000. Currently, Kufa and Najaf ...

n Ibn Hawshab

Abu'l-Qāsim al-Ḥasan ibn Faraj ibn Ḥawshab ibn Zādān al-Najjār al-Kūfī ( ar, أبو القاسم الحسن ابن فرج بن حوشب زاذان النجار الكوفي ; died 31 December 914), better known simply as Ibn Ḥawshab, ...

, and the native Yemeni Ali ibn al-Fadl al-Jayshani

ʿAlī ibn al-Faḍl al-Jayshānī () was a senior Isma'ili missionary () from Yemen. In cooperation with Ibn Hawshab, he established the Isma'ili creed in his home country and conquered much of it in the 890s and 900s in the name of the hidden Is ...

, later in the century. Their propaganda activity () in Yemen began in 881, among the mountain tribes. Ibn Hawshab targeted the central highlands near Sana'a, while his colleague made Janad his base.

As in other areas of the Islamic world, the Isma'ili preaching of the imminent appearance of a messiah () from the line of the descendants of Muhammad's daughter Fatimah

Fāṭima bint Muḥammad ( ar, فَاطِمَة ٱبْنَت مُحَمَّد}, 605/15–632 CE), commonly known as Fāṭima al-Zahrāʾ (), was the daughter of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his wife Khadija. Fatima's husband was Ali, th ...

and Ali ibn Abi Talib

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam. ...

, proved popular. The widespread millennialist expectations of the period coincided with a prolonged crisis of the Abbasid Caliphate, and with dissatisfaction among many adherents of the more mainstream Twelver Shi'a, to enhance the appeal of the revolutionary Isma'ili message. The Isma'ili movement quickly expanded over much of the country, with Sana'a being captured in 905. Yemen also served as a major centre for the Isma'ili , with Ibn Hawshab sending missionaries to Oman, the Yamama and even Sindh

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

. Most notable among these missionaries was Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i

Al-Husayn ibn Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Zakariyya, better known as Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i ( ar, ابو عبد الله الشيعي, Abū ʿAbd Allāh ash-Shi'ī), was an Isma'ili missionary ('' dāʿī'') active in Yemen and North Africa, mainly amon ...

, a native of Sana'a. On Ibn Hawshab's instructions, in 893 he left for the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

, where he began proselytizing among the Kutama

The Kutama ( Berber: ''Ikutamen''; ar, كتامة) was a Berber tribe in northern Algeria classified among the Berber confederation of the Bavares. The Kutama are attested much earlier, in the form ''Koidamousii'' by the Greek geographer Ptolemy. ...

Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

. His mission was extremely successful. Backed by the Kutama, in 903 he was able to rise in revolt against the Aghlabid

The Aghlabids ( ar, الأغالبة) were an Arab dynasty of emirs from the Najdi tribe of Banu Tamim, who ruled Ifriqiya and parts of Southern Italy, Sicily, and possibly Sardinia, nominally on behalf of the Abbasid Caliph, for about a cen ...

emirs of Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya ( '), also known as al-Maghrib al-Adna ( ar, المغرب الأدنى), was a medieval historical region comprising today's Tunisia and eastern Algeria, and Tripolitania (today's western Libya). It included all of what had previously ...

, culminating in their overthrow and the establishment of the Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Isma'ilism, Ismaili Shia Islam, Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the ea ...

in 909.

Meanwhile, in Yemen, the Isma'ilis engaged in a series of back-and-forth contests with the Yu'firids and the newly established Zaydi imamate followed over control of Sana'a, but Ibn al-Fadl emerged victorious in 911. At that point, just as Isma'ilism was triumphant in Yemen and the Fatimid Caliphate had just been established under the supposed , Ibn al-Fadl broke with the Isma'ili cause and his colleague, Ibn Hawshab, and claimed to be the himself. Following the death of both Isma'ili leaders in 914–915, their regimes collapsed amidst internal squabbles and Yu'firid attacks. The Yu'firid ruler As'ad ibn Abi Ya'fur, a former vassal of Ibn al-Fadl, captured Mudhaykhirah in 917, and the Isma'ili movement in Yemen returned to being a secretive, underground affair for over a century, until the rise of the Sulayhid dynasty

The Sulayhid dynasty ( ar, بَنُو صُلَيْح, Banū Ṣulayḥ, lit=Children of Sulayh) was an Ismaili Shi'ite Arab dynasty established in 1047 by Ali ibn Muhammad al-Sulayhi that ruled most of historical Yemen at its peak. The Sulayh ...

.

Establishment of the first Zaydi imamate

While the two Isma'ili s extended their influence, another Shi'a leader arrived in Yemen: Yahya, a representative of the rival Zaydi sect. In Zaydi doctrine, the imam has to be a descendant of Fatimah and Ali, but the position is not hereditary or by appointment (), unlike in the Twelver and Isma'ili traditions of Shi'a Islam. Instead, it can be claimed by any qualified Fatimid who fulfills a number (usually 14) of stringent conditions (religious learning, piety, bravery, etc.), by 'rising' () and 'calling' () for the allegiance of the faithful. Zaydi doctrine emphasized that the imamate was not contingent on popular acclaim or election; the very act of denotes God's choice. On the other hand, if a more excellent candidate appears, the incumbent imam is obliged to acknowledge him. Previous Zaydi uprisings against the Abbasids in Iraq and theHejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provin ...

—the heartlands of the Islamic world—had failed, but had been successful in the Caliphate's peripheral areas: Idris ibn Abdallah

Idris (I) ibn Abd Allah ( ar, إدريس بن عبد الله, translit=Idrīs ibn ʿAbd Allāh), also known as Idris the Elder ( ar, إدريس الأكبر, translit=Idrīs al-Akbar), (d. 791) was an Arab Hasanid Sharif and the founder of the ...

had founded a Zaydi state in what is now Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

, while a distant relative of Yahya's, Hasan ibn Zayd

Abū Muḥammad al-Ḥasan ibn Zayd ibn Muḥammad ibn Ismaʿīl ibn al-Ḥasan ibn Zayd ( ar, الحسن بن زيد بن محمد; died 6 January 884), also known as ''al-Dāʿī al-Kabīr'' ( ar, الداعي الكبير, "the Great/Elder Mis ...

, had founded a Zaydi state in Tabaristan

Tabaristan or Tabarestan ( fa, طبرستان, Ṭabarestān, or mzn, تبرستون, Tabarestun, ultimately from Middle Persian: , ''Tapur(i)stān''), was the name applied to a mountainous region located on the Caspian coast of northern Iran. ...

, a mountainous region on the southern shores of the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central Asia ...

. Yahya himself spent some time in Tabaristan, before being invited to Yemen in 893/4 to settle tribal disputes in the north of the country. This first sojourn failed, and he had left, but in 897 he returned and quickly established a state based in Sa'ada, in the northern highlands, with himself as imam with the title (). Given the continued presence and importance of the Zaydi imamate in the subsequent Yemeni history, up to the dissolution of the Zaydi kingdom in 1962, this marks one of the most important turning points in Yemeni history.

Until Yahya's death in 911, the nascent Zaydi imamate rivalled with the Yu'firids and the Isma'ilis over control over Sana'a. His death left the new Zaydi regime ruderless. As the historian Ella Landau-Tasseron notes, the Zaydi imamate was not a state as such, as "there was no formal administrative apparatus and no fixed pattern of succession". Anyone of Alid descent could lay claim to the imamate, as long as he engaged in military activity to promote the Zaydi cause. This meant that the line of imams was often interrupted by interregna, or that multiple candidates for the imamate appeared at the same time. At the same time, the obligation to promote Zaydism by force meant that the imams were in constant conflict with non-Zaydis, as well as with their own followers when they refused to obey imam's authority; not even taking into account that the Zaydi imams in Yemen, being reliant on tribal backing, were themselves drawn into pre-existing tribal conflicts.

Nevertheless, the first Zaydi imamate founded by Yahya and his successors of the Rassid dynasty

The Imams of Yemen and later also the Kings of Yemen were religiously consecrated leaders belonging to the Zaidiyyah branch of Shia Islam. They established a blend of religious and political rule in parts of Yemen from 897. Their imamate endured u ...

survived in its core territories of Sa'ada and Najran until 1058, when, weakened by internal conflicts and sectarian disputes, the Sulayhid dynasty destroyed it.

Dynasties of the 11th–12th centuries

The death of the Isma'ili and Zaydi leaders in short succession allowed for a brief resurgence of Yu'firid power in and around Sana'a, but this did not outlast As'ad ibn Abi Ya'fur's death in 955. Weakened by internal quarrels, the Yu'firid dynasty ended in 997 with the death of the last ruler, Abdallah ibn Qahtan Abdallah, atIbb

Ibb ( ar, إِبّ, ʾIbb) is a city in Yemen, the capital of Ibb Governorate, located about northeast of Mocha and south of Sana'a.

A market town and administrative centre developed during the Ottoman Empire, it is one of the most important ...

. At the same time, the Ziydadid dynasty also declined, although little information survives: the last rulers of the dynasty are obscure, and after 981 and until the dynasty's ostensible end in 1018, not even their names are known.

Lowland dynasties: Najahids, Sulaymanids, and Mahdids

The Ziyadids were replaced in the Tihama lowlands by theNajahid dynasty

Najahid dynasty ( ar, بنو نجاح; Banū Najāḥ) was a slave dynasty of Abyssinian origin founded in Zabid in the Tihama (lowlands) region of Yemen around 1050 AD.

They faced hostilities from the Highlands dynasties of the time, chiefly ...

, established in 1022 by two Black African slave brothers, Najah and Nafis. Najah quickly sidelined his brother, and secured recognition from the Abbasid caliph. However, their territory was smaller than that of the Ziyadids, being limited to the Tihama, and their history was rather chequered. In 1060, the highland Sulayhid dynasty conquered their lands for twenty years, and it was only after a prolonged struggle that in 1089 that a new Najahid ruler, Jayyash, established his power firmly over Zabid and its territory. Jayyash founded the city of Hais

The Houston Academy for International Studies (HAIS) is a Houston Independent School District charter school in Midtown Houston, Texas, United States. It is located on the Houston Community College System's Central College campus. It opened in Aug ...

, which he settled with his kinsfolk from Abyssinia

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historica ...

.

In the late 12th century, another regional dynasty arose in the northern Tihama, the Sulaymanids

The Sulaymanids () were a sharif dynasty from the line of the Muhammad's grandson Hasan bin Ali which ruled around 1063–1174. Their centre of power lay in Jazan in currently Saudi Arabia, Southern Arabia back then since 1020 where

they soon a ...

. These were an otherwise obscure family of Hasanid

The Ḥasanids ( ar, بنو حسن, Banū Ḥasan or , ) are the descendants of Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī, brother of Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī and grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. They are a branch of the Alids (the descendants of ʿAlī ibn Ab� ...

descent, who took power in Harad

In J. R. R. Tolkien's high fantasy ''The Lord of the Rings'', Harad is the immense land south of Gondor and Mordor. Its main port is Umbar, the base of the Corsairs of Umbar whose ships serve as the Dark Lord Sauron's fleet. Its people are the ...

around 1069 (the date is hypothetical), and likely served as vassals of the Najahids.

After the death of Jayyash, power was held by a series of slave () viziers who served in the Najahid ruler's name until 1156, when the Mahdid dynasty replaced them. The Mahdid dynasty was founded by the religious preacher Ali ibn Mahdi, who claimed descent from the Himyarite kings. Although he enjoyed the favour of the Najahid queen Alam al-Malika Alam al-Malika () (died 1130), was the chief adviser and ''de facto'' prime minister of the Najahid dynasty of Zubayd in Yemen in 1111–1123, and its ruler in 1123–1130.

She was the slave singer, or ''jarya'', to King Mansur ibn Najah of Zubay ...

, after her death in 1150 he began a series of attacks on Zabid. These failed, but his intrigues with the Najahid viziers bore fruit: by 1159, Zabid was in his hands, but he died shortly thereafter. His son and successor, Abd al-Nabi, is portrayed in most historical sources as a dissolute, ambitious, and evil ruler, who aimed to conquer the world. Indeed he launched frequent and brutal raids against all his neighbours, killing the Sulaymanid ruler in 1164, capturing Taiz and Ibb in 1165, and beginning a seven-year-long siege of Aden

Aden ( ar, عدن ' Yemeni: ) is a city, and since 2015, the temporary capital of Yemen, near the eastern approach to the Red Sea (the Gulf of Aden), some east of the strait Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000 people. ...

that was only broken in 1173 when the Zurayids and Hamdanids allied against him. Shortly after, the Ayyubid prince Turan-Shah

Shams ad-Din Turanshah ibn Ayyub al-Malik al-Mu'azzam Shams ad-Dawla Fakhr ad-Din known simply as Turanshah ( ar, توران شاه بن أيوب) (died 27 June 1180) was the Ayyubid emir (prince) of Yemen (1174–1176), Damascus (1176–1179), ...

entered Yemen, invited by the Sulaymanids, and began its conquest by capturing Zabid and ending the Mahdid state.

In the highlands: the Sulayhids and their successors

The Sulayhids, unlike the aforementioned regimes, were native Yemenis. The founder of the regime was Ali as-Sulayhi (d. 1067) who propagated Ismaili doctrines and established a state in the highlands in 1047. He took the Tihama lowland from the Najahids in 1060 and subjugated the important coastal entrepôt

The Sulayhids, unlike the aforementioned regimes, were native Yemenis. The founder of the regime was Ali as-Sulayhi (d. 1067) who propagated Ismaili doctrines and established a state in the highlands in 1047. He took the Tihama lowland from the Najahids in 1060 and subjugated the important coastal entrepôt Aden

Aden ( ar, عدن ' Yemeni: ) is a city, and since 2015, the temporary capital of Yemen, near the eastern approach to the Red Sea (the Gulf of Aden), some east of the strait Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000 people. ...

. Ali as-Sulayhi formally ruled in the name of the Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dy ...

caliph in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

. He was murdered by the Najahids in 1067 or 1081, but his mission was continued by his son al-Mukarram Ahmad (d. 1091) and the latter's widow as-Sayyidah Arwa (d. 1138). Arwa is one of the few female rulers in the Islamic history of Arabia, and is praised in the sources for her piety, bravery, intelligence, and cultural interests. The dynasty ruled first from San'a and later Dhu Jibla

Jiblah ( ar, جِبْلَة) is a town in south-western Yemen, south, south-west of Ibb in the Ibb Governorate, governorate of the same name. It is located at the elevation of around , near Jabal At-Taʿkar (). The town and its surroundings we ...

. Sulayhid rule meant a nadir for the Zaydiyyah imamate, which did not bring forth any fully recognized imams from 1052 to 1138. The Sulayhids died out in 1138 with Queen Arwa. Their position in San'a was taken over for a while by the Hamdanid sultans

The Yemeni Hamdanids ( ar, الهمدانيون) was a series of three families descended from the Arab Banū Hamdān tribe, who ruled in northern Yemen between 1099 and 1174. They were expelled from power when the Ayyubids conquered Yemen in 117 ...

(until 1174). The dynasty ended with Arwa al-Sulayhi

)

, name = Arwā bint Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Jaʿfar ibn Mūsā Aṣ-Ṣulayḥī

, other_names = ''As-Sayyidah Al-Ḥurrah'' () ''Al-Malikah Al-Ḥurrah'' ( ar, ٱلْمَلِكَة ٱلْحُرَّة or ...

affiliating to the Taiyabi

Tayyibi Isma'ilism is the only surviving sect of the Musta'li branch of Isma'ilism, the other being the extinct Hafizi branch. Followers of Tayyibi Isma'ilism are found in various Bohra communities: Dawoodi, Sulaymani, and Alavi.

The Tayyibi ...

Ismaili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sa ...

sect as opposed to the Hafizi

Hafizi Isma'ilism ( ar, حافظية, Ḥāfiẓiyya or , ) was a branch of Musta'li Isma'ilism that emerged as a result of a split in 1132. The Hafizis accepted the Fatimid caliph Abd al-Majid al-Hafiz li-Din Allah () and his successors as imams ...

Ismaili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sa ...

sect that the other Ismaili dynasties such as the Zurayids

The Zurayids (بنو زريع, Banū Zuraiʿ), were a Yamite Hamdani dynasty based in Yemen in the time between 1083 and 1174. The centre of its power was Aden. The Zurayids suffered the same fate as the Hamdanid sultans, the Sulaymanids and ...

and the Hamdanids (Yemen)

The Yemeni Hamdanids ( ar, الهمدانيون) was a series of three families descended from the Arab Banū Hamdān tribe, who ruled in northern Yemen between 1099 and 1174. They were expelled from power when the Ayyubids conquered Yemen in 117 ...

adhered to.

Zurayids (1083–1174)

Al-Abbas and al-Mas'ūd, sons of Karam Al-Yami from the Hamdan tribe, started ruling Aden on behalf of the Sulayhids. When Al-Abbas died in 1083, his son Zuray, who gave the dynasty its name, proceeded to rule together with his uncle al-Mas'ūd. They took part in the Sulayhid leader al-Mufaddal's campaign against the Najahid capitalZabid

Zabid ( ar, زَبِيد) (also spelled Zabīd, Zabeed and Zebid) is a town with an urban population of around 52,590 people on Yemen's western coastal plain. It is one of the oldest towns in Yemen, and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since ...

and were both killed during the siege (1110). Their respective sons ceased to pay tribute to the Sulayhid queen Arwa al-Sulayhi

)

, name = Arwā bint Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Jaʿfar ibn Mūsā Aṣ-Ṣulayḥī

, other_names = ''As-Sayyidah Al-Ḥurrah'' () ''Al-Malikah Al-Ḥurrah'' ( ar, ٱلْمَلِكَة ٱلْحُرَّة or ...

. They were worsted by a Sulayhid expedition but queen Arwa agreed to reduce the tribute by half, to 50,000 dinars per year. The Zurayids again failed to pay and were once again forced to yield to the might of the Sulayhids, but this time the annual tribute from the incomes of Aden was reduced to 25,000. Later on they ceased to pay even that since Sulayhid power was on the wane. After 1110 the Zurayids thus led a more than 60 years long independent rule in the city, bolstered by the international trade. The chronicles mention luxury goods such as textiles, perfume and porcelain, coming from places like North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of t ...

, Kirman Kerman is the capital city of Kerman Province, Iran.

Kerman or Kirman may also refer to:

Places

*Kirman (Sasanian province), province of the Sasanian Empire

* Kerman Province, province of Iran

** Kerman County

*Kerman, California

People

* Jo ...

and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

. After the demise of queen Arwa al-Sulayhi in 1138, the Fatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Isma'ilism, Ismaili Shia Islam, Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the ea ...

in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

kept a representation in Aden, adding further prestige to the Zurayids. The Zurayids were sacked by the Ayyubids in 1174 AD. They were a Shia

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that the Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad designated Ali, ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his S ...

Ismaili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sa ...

dynasty that followed the Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dy ...

Caliphs

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

based in Egypt. They were also Hafizi

Hafizi Isma'ilism ( ar, حافظية, Ḥāfiẓiyya or , ) was a branch of Musta'li Isma'ilism that emerged as a result of a split in 1132. The Hafizis accepted the Fatimid caliph Abd al-Majid al-Hafiz li-Din Allah () and his successors as imams ...

Ismaili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sa ...

as opposed to the Taiyabi

Tayyibi Isma'ilism is the only surviving sect of the Musta'li branch of Isma'ilism, the other being the extinct Hafizi branch. Followers of Tayyibi Isma'ilism are found in various Bohra communities: Dawoodi, Sulaymani, and Alavi.

The Tayyibi ...

Ismaili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sa ...

.

Hamdanids (1099-1174)

The YemeniHamdanids

The Hamdanid dynasty ( ar, الحمدانيون, al-Ḥamdāniyyūn) was a Twelver Shia Arab dynasty of Northern Mesopotamia and Syria (890–1004). They descended from the ancient Banu Taghlib Christian tribe of Mesopotamia and Eastern A ...

were a series of three families descended from the Arab Banū Hamdān tribe, who ruled in northern Yemen between 1099 and 1174. They must not be confused with the Hamdanids who ruled in al-Jazira and northern Syria in 906-1004. They were expelled from power when the Ayyubids conquered Yemen in 1174. They were a Shia

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that the Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad designated Ali, ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his S ...

Ismaili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sa ...

dynasty that followed the Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dy ...

Caliphs

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

based in Egypt. They were also Hafizi

Hafizi Isma'ilism ( ar, حافظية, Ḥāfiẓiyya or , ) was a branch of Musta'li Isma'ilism that emerged as a result of a split in 1132. The Hafizis accepted the Fatimid caliph Abd al-Majid al-Hafiz li-Din Allah () and his successors as imams ...

Ismaili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sa ...

as opposed to the Taiyabi

Tayyibi Isma'ilism is the only surviving sect of the Musta'li branch of Isma'ilism, the other being the extinct Hafizi branch. Followers of Tayyibi Isma'ilism are found in various Bohra communities: Dawoodi, Sulaymani, and Alavi.

The Tayyibi ...

Ismaili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sa ...

.

Ayyubid era (1174–1229)

The importance of Yemen as a station in the trade between Egypt and theIndian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by th ...

area, and its strategical value, motivated the Ayyubid invasion in 1174. The Ayyubid forces were led by Turanshah, a brother of Sultan Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

. The enterprise was entirely successful: the various local Yemeni dynasties, mainly the Zurayids

The Zurayids (بنو زريع, Banū Zuraiʿ), were a Yamite Hamdani dynasty based in Yemen in the time between 1083 and 1174. The centre of its power was Aden. The Zurayids suffered the same fate as the Hamdanid sultans, the Sulaymanids and ...

were defeated or submitted, thus bringing an end to the fragmented political landscape. The efficient military might of the Ayyubids meant that they were not seriously threatened by local regimes during 55 years in power. The only disturbing element was the Zaydi imam who was active for part of the period. After 1217 the imamate was split, however. Members of the Ayyubid Dynasty were appointed to rule Yemen up to 1229, but they were often absent from the country, a factor that finally led to them being superseded by the following regime, the Rasulids

The Rasulids ( ar, بنو رسول, Banū Rasūl) were a Sunni Muslim dynasty who ruled Yemen from 1229 to 1454.

History

Origin of the Rasulids

The Rasulids took their name from al-Amin's nickname "Rasul". The Zaidi Shi'i Imams of Yemen were ...

. On the positive side, the Ayyubids united the bulk of Yemen in a way that had hardly been achieved before. The system of fiefs used in the Ayyubid core area was introduced to Yemen. The policies of the Ayyubids led to a bipartition that has lasted ever since: the coast and southern highlands dominated by Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

and adhering to the Shafi'i

The Shafii ( ar, شَافِعِي, translit=Shāfiʿī, also spelled Shafei) school, also known as Madhhab al-Shāfiʿī, is one of the four major traditional schools of religious law (madhhab) in the Sunnī branch of Islam. It was founded by ...

school of law; and the upper highlands with a population mainly adhering to the Zaydiyyah. Ayyubid rule was therefore an important stepping-stone for the next dynastic regime.

Rasulid era (1229–1454)

The

The Rasulid dynasty

The Rasulids ( ar, بنو رسول, Banū Rasūl) were a Sunni Muslim dynasty who ruled Yemen from 1229 to 1454.

History

Origin of the Rasulids

The Rasulids took their name from al-Amin's nickname "Rasul". The Zaidi Shi'i Imams of Yemen wer ...

, or Bani Rasul, were soldiers of Turkoman origins who served the Ayyubids. When the last Ayyubid ruler left Yemen in 1229 he appointed a member of Bani Rasul, Nur ad-Din Umar, as his deputy. He was later able to secure an independent position in Yemen and was recognized as sultan in his own right by the Abbasid Caliph in 1235. He and his descendants drew their methods of governance from the structures set up by the Ayyubids. Their capitals were Zabid

Zabid ( ar, زَبِيد) (also spelled Zabīd, Zabeed and Zebid) is a town with an urban population of around 52,590 people on Yemen's western coastal plain. It is one of the oldest towns in Yemen, and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since ...

and Ta'izz

Taiz ( ar, تَعِزّ, Taʿizz) is a city in southwestern Yemen. It is located in the Yemeni Highlands, near the port city of Mocha on the Red Sea, at an elevation of about above sea level. It is the capital of Taiz Governorate. With a populat ...

. For the first time, most of Yemen became a strong and independent political, economic, and cultural unit. The state was even able to contend with the Ayyubids and later the Mamluks

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') i ...

over influence in Hijaz. The south Arabian coast was subdued in 1278–79. The Rasulids in fact created the strongest Yemeni state during the medieval Islamic era. Among the numerous medieval polities it was the one that endured for the longest period, and enjoyed the widest influence. Its impact in terms of administration and culture was stronger than the preceding regimes, and the interests of the Rasulid rulers covered all the affairs prevalent in those times.

Some of the sultans had strong scientific interests and were skilled in astrology, medicine, agriculture, linguistics, legislation, etc. They built mosques, houses and citadels, roads and water channels. Rasulid projects extended as far as Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red ...

. The Sunnization of the land was intensified and madrasa

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , pl. , ) is the Arabic word for any type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whether for elementary instruction or higher learning. The word is variously transliterated '' ...

s were built everywhere. The flourishing trade gave the sultans great incomes which bolstered their regime. In the highlands the Zaydiyyah were initially pushed back by the Rasulid might. Nevertheless, after the late 13th century a succession of imams were able to build up a strong position and expand their influence. As for the Rasulid regime it was upheld by a long series of very gifted sultans. However, the polity began to decline in the 14th century, and especially after 1424. From 1442 to 1454 a number of rival claimants competed for the throne, which led to the downfall of the dynasty in the latter year.

Tahirids (1454–1517)

The Bani Tahir was a powerful native Yemeni family which took advantage of the weakness of the Rasulids and finally gained power in 1454 as the Tahirids. In many respects the new regime tried to imitate the Bani Rasul whose institutions they took over. Thus they built schools, mosques and irrigation channels as well as water cisterns and bridges inZabid

Zabid ( ar, زَبِيد) (also spelled Zabīd, Zabeed and Zebid) is a town with an urban population of around 52,590 people on Yemen's western coastal plain. It is one of the oldest towns in Yemen, and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since ...

, Aden, Yafrus, Rada

The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA; ) is a drama school in London, England, that provides vocational conservatoire training for theatre, film, television, and radio. It is based in the Bloomsbury area of Central London, close to the Senat ...

, Juban, etc. Politically the Tahirids did not have ambitions to expand beyond Yemen itself. The sultans fought the Zaydi imams for periods, with varying success. They were never able to occupy the highlands entirely. The Mamluk regime in Egypt began to dispatch seaborne expeditions towards the south after 1507, since the presence of the Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

constituted a threat in the southern Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

region. At first the Tahirid sultan Amir II supported the Mamluks, but later refused to assist them. As a consequence he was attacked and killed by a Mamluk force in 1517. Tahirid resistance leaders continued to disturb the Mamluk occupiers until 1538. As it turned out, the Tahirids were the last Sunni dynasty to rule in Yemen.

First Ottoman period (1538–1635)

Now, the coast and southern highlands were suddenly left without a central government for the first time in almost 350 years. Shortly after the Mamluk conquest in 1517, Egypt itself was conquered by the Ottoman sultanSelim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite last ...

. The Egyptian garrison in Yemen was cornered in a minor part of the Tihama, and the Zaydi imam expanded his territory. The Mamluk militaries formally recognized the Ottomans until 1538, when regular Turkish forces arrived. At this time the Ottomans began to worry about the Portuguese who occupied Socotra

Socotra or Soqotra (; ar, سُقُطْرَىٰ ; so, Suqadara) is an island of the Republic of Yemen in the Indian Ocean, under the ''de facto'' control of the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council, a secessionist participant in Yemen’s ...

Island. The Ottomans eliminated the last Tahirid lord in Aden and the Mamluk military leadership, and set up an administration based in Zabid. Yemen was made a province ( Beylerbeylik). The Portuguese blockade of the Red Sea was broken. A number of campaigns against the Zaydis were fought in 1539-56, and Sana'a

Sanaa ( ar, صَنْعَاء, ' , Yemeni Arabic: ; Old South Arabian: 𐩮𐩬𐩲𐩥 ''Ṣnʿw''), also spelled Sana'a or Sana, is the capital and largest city in Yemen and the centre of Sanaa Governorate. The city is not part of the Governo ...

was taken in 1547. Turkish misrule led to a large rebellion in 1568. The Zaydi imam put up a stubborn fight against the invaders who were almost expelled from Yemeni soil. Resistance was overcome in a new campaign in 1569–1571. After the death of imam al-Mutahhar

Al-Mutahhar bin Yahya Sharaf ad-Din (January 3, 1503 – November 9, 1572) was an imam of the Zaidi state of Yemen who ruled from 1547 to 1572. His era marked the temporary end of an autonomous Yemeni polity in the highlands.

The coming of th ...

in 1572, the highlands were occupied by the Turkish troops. The first Turkish occupation lasted until 1635. The new lords promoted Sufis

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

and Ismailis as a counterweight to the Zaydiyyah. However, Yemen was too far removed to be managed efficaciously. Over-taxation and unjust and cruel practices caused deep popular antipathy against foreign rule. The Zaydis accused the Ottomans of being "infidels of interpretation" and appointed a new imam in 1597, al-Mansur al-Qasim

Al-Mansur al-Qasim (November 13, 1559 – February 19, 1620), with the cognomen ''al-Kabir'' (the Great), was an Imam of Yemen, who commenced the struggle to liberate Yemen from the Ottoman occupiers. He was the founder of a Zaidi kingdom that e ...

. In accordance with the doctrine that an imam must make a summons to allegiance (da'wa

Dawah ( ar, دعوة, lit=invitation, ) is the act of inviting or calling people to embrace Islam. The plural is ''da‘wāt'' (دَعْوات) or ''da‘awāt'' (دَعَوات).

Etymology

The English term ''Dawah'' derives from the Arabic ...

) and rebel against illegitimate rulers, Imam al-Mansur and his successor expanded their territory at the expense of the Turks who eventually had to leave their last possessions in 1635.

Qasimids (1597–1872)

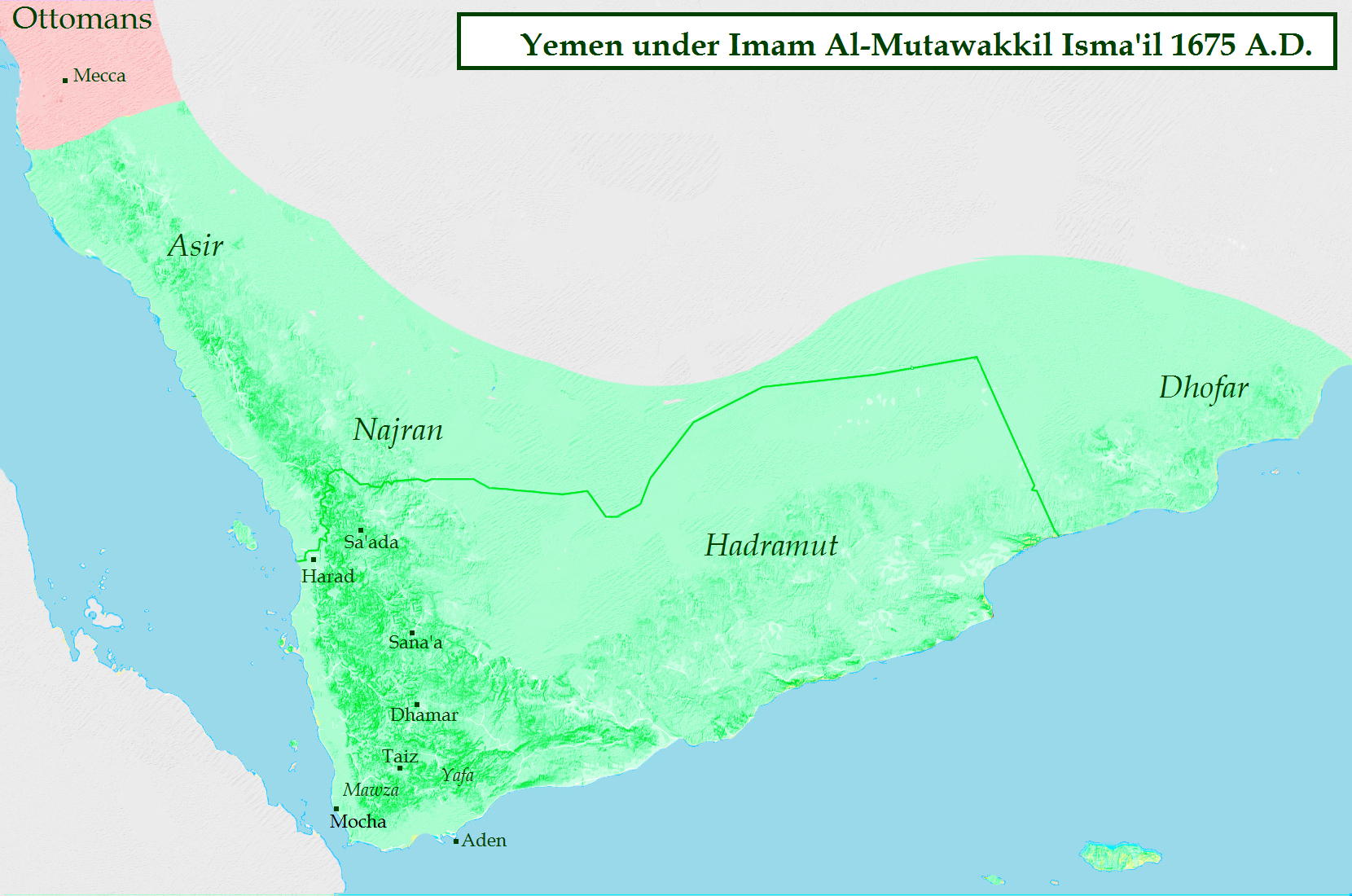

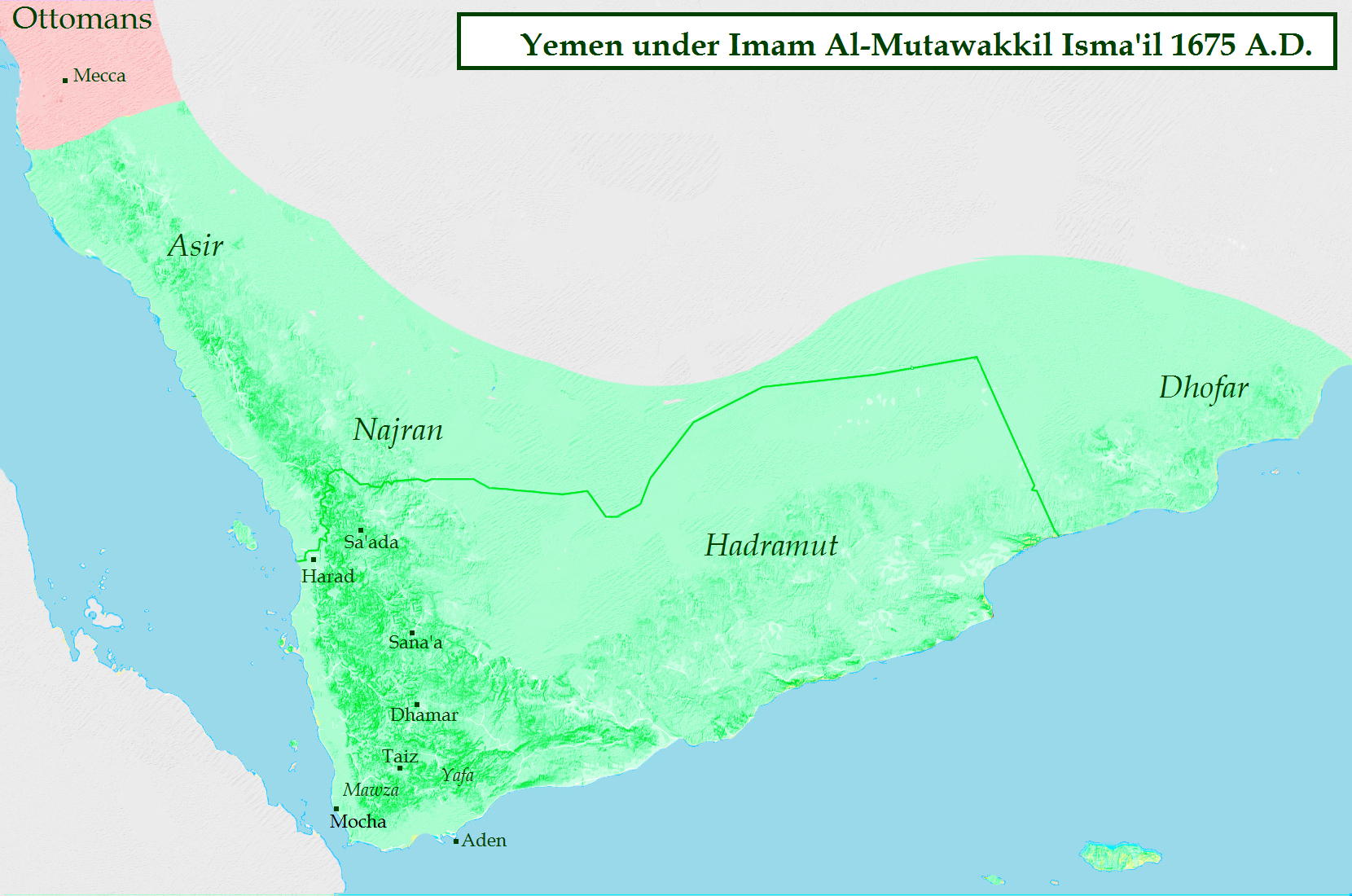

The imam

The imam al-Mansur al-Qasim

Al-Mansur al-Qasim (November 13, 1559 – February 19, 1620), with the cognomen ''al-Kabir'' (the Great), was an Imam of Yemen, who commenced the struggle to liberate Yemen from the Ottoman occupiers. He was the founder of a Zaidi kingdom that e ...

(r. 1597–1620) belonged to one of the branches of the Rassid (descendants of the first imam or his close family). The new line became known as the Qasimids after its founder. Al-Mansur's son al-Mu'ayyad Muhammad

Al-Mu'ayyad Muhammad (1582 – September 1644) was an Imam of Yemen (1620–1644), son of Al-Mansur al-Qasim. He managed to expel the Ottoman Turks entirely from the Yemenite lands, thus confirming an independent Zaidi state.

Succeeding to the ...

(r. 1620–1644) managed to gather Yemen under his authority, expel the Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

, and established an independent political entity. His successor al-Mutawakkil Isma'il

Al-Mutawakkil Isma'il (c. 1610 – 15 August 1676) was an Imam of Yemen who ruled the country from 1644 until 1676. He was a son of Al-Mansur al-Qasim. His rule saw the biggest territorial expansion of the Zaidiyyah imamate in Greater Yemen.

E ...

(r. 1644–1676) subdued Hadramawt and entertained diplomatic contacts with the negus

Negus (Negeuce, Negoose) ( gez, ንጉሥ, ' ; cf. ti, ነጋሲ ' ) is a title in the Ethiopian Semitic languages. It denotes a monarch,

of Ethiopia and the Mughal emperor Aurangzib. He also reinstated the common annual pilgrimage caravans to Mecca