The story of

Dhul-Qarnayn

, ( ar, ذُو ٱلْقَرْنَيْن, Ḏū l-Qarnayn, ; "He of the Two Horns") appears in the Quran, Surah Al-Kahf (18), Ayahs 83–101 as one who travels to east and west and sets up a barrier between a certain people and Gog and Magog ...

(in

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

ذو القرنين, literally "The Two-Horned One"; also

transliterated

Transliteration is a type of conversion of a text from one script to another that involves swapping letters (thus '' trans-'' + '' liter-'') in predictable ways, such as Greek → , Cyrillic → , Greek → the digraph , Armenian → or ...

as Zul-Qarnain or Zulqarnain), is mentioned in the

Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

.

It has long been recognised in modern scholarship that the story of Dhul-Qarnayn has strong similarities with the Syriac Legend of

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

.

According to this legend, Alexander travelled to the ends of the world then built a

wall

A wall is a structure and a surface that defines an area; carries a load; provides security, shelter, or soundproofing; or, is decorative. There are many kinds of walls, including:

* Walls in buildings that form a fundamental part of the supe ...

in the

Caucasus mountains

The Caucasus Mountains,

: pronounced

* hy, Կովկասյան լեռներ,

: pronounced

* az, Qafqaz dağları, pronounced

* rus, Кавка́зские го́ры, Kavkázskiye góry, kɐfˈkasːkʲɪje ˈɡorɨ

* tr, Kafkas Dağla ...

to keep

Gog and Magog out of civilized lands (the latter element is found several centuries earlier in

Flavius Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

). Several argue that the form of this narrative in the Syriac ''Alexander Legend'' (known as the Neṣḥānā) dates to between 629 and 636 CE and so is not the source for the Qur'anic narrative based on the view held by many Western and Muslim scholars that Surah 18 belongs to the second Meccan Period (615–619). The Syriac Legend of Alexander has however received a range of dates by different scholars, from a latest date of 630

(close to

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

's death) to an earlier version inferred to have existed in the 6th century CE.

Sidney Griffith argues that the simple storyline found in the Syriac ''Alexander Legend'' (and the slightly later ''metrical homily'' or Alexander poem) "would most likely have been current orally well before the composition of either of the Syriac texts in writing" and it is possible that it was this orally circulating version of the account which was recollected in the Islamic milieu.

The majority of modern researchers of the Qur'an as well as Islamic commentators identify Dhul Qarnayn as Alexander the Great.

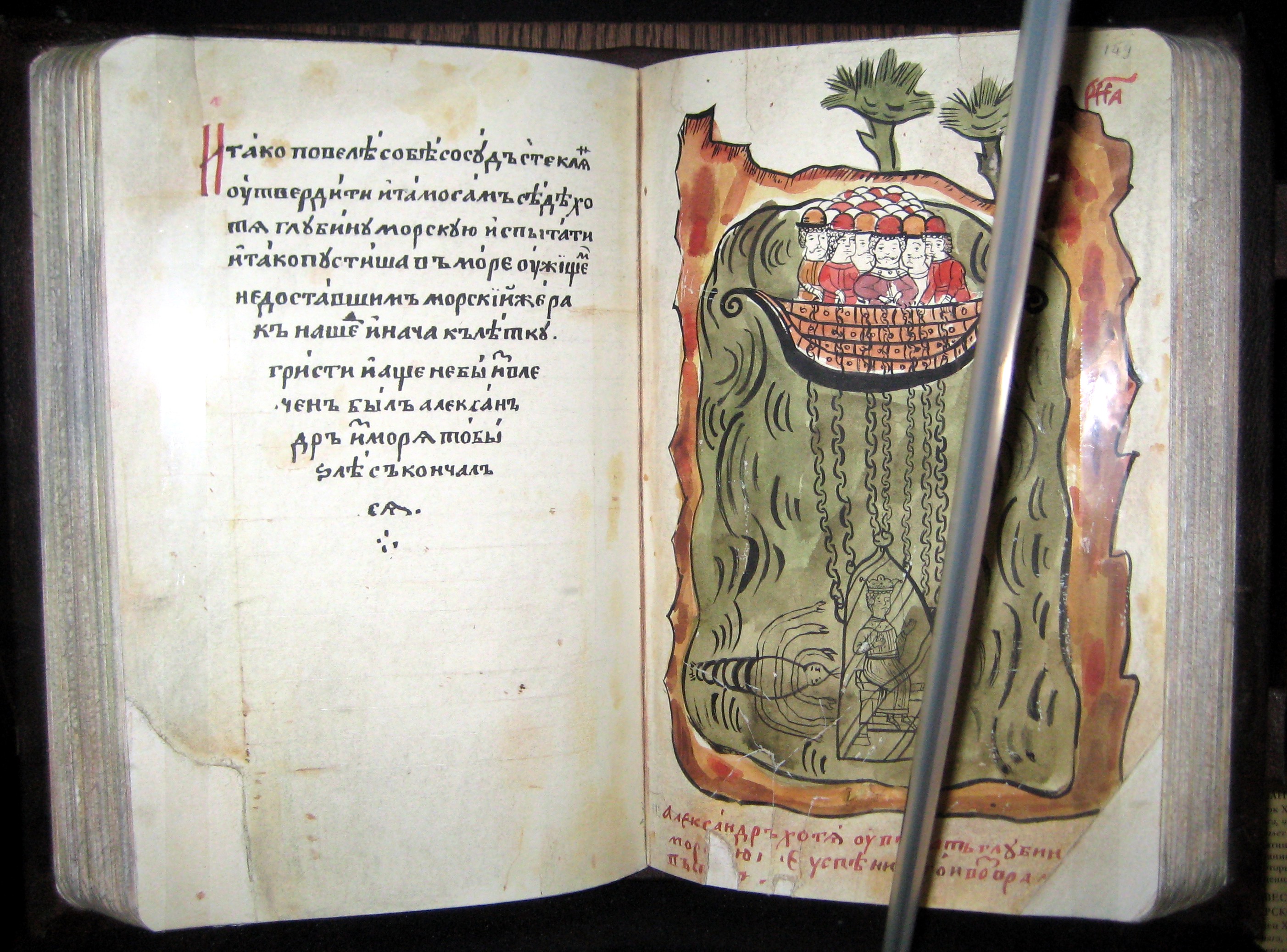

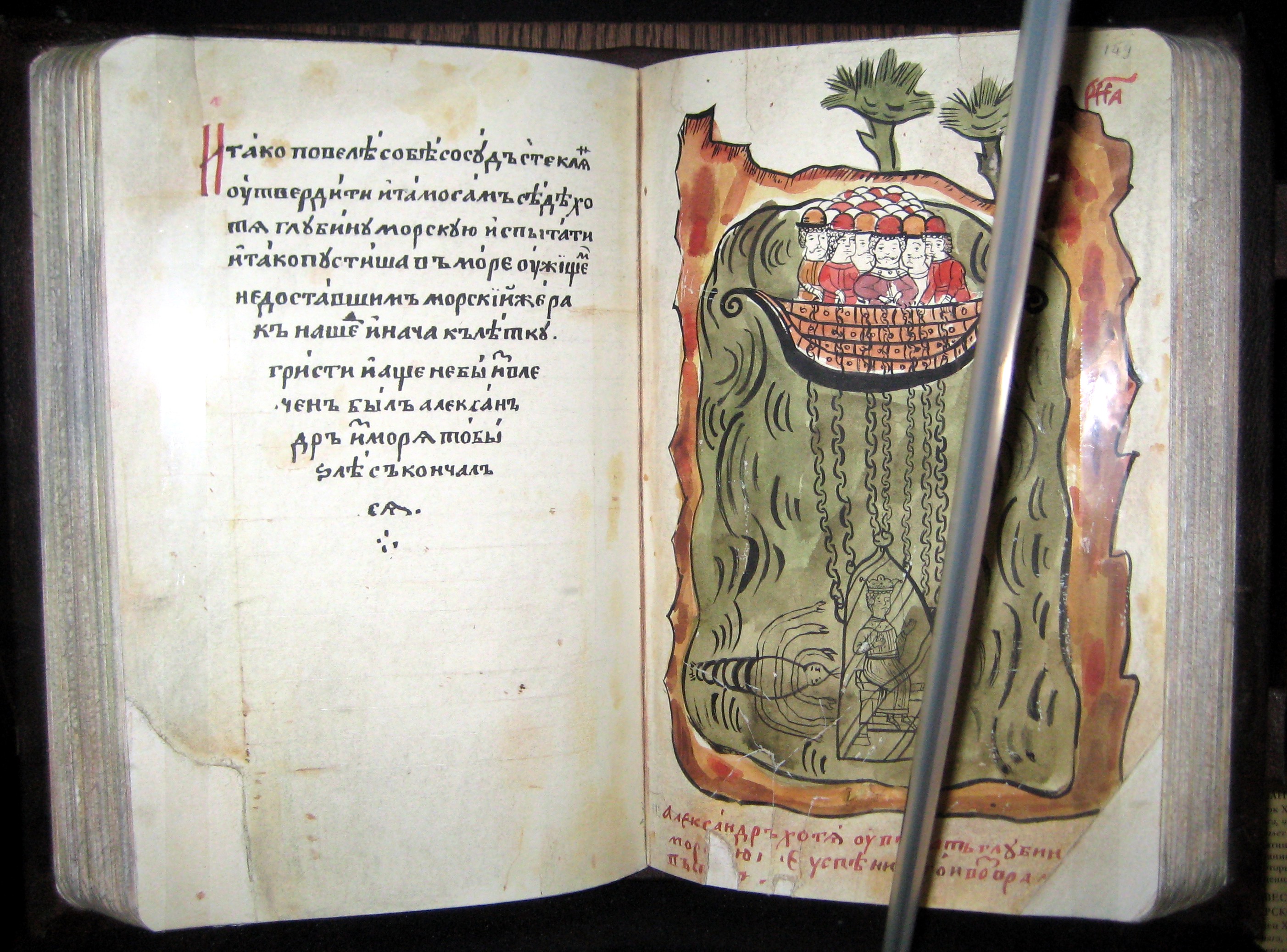

The legendary Alexander

Alexander in legend and romance

Alexander the Great was an immensely popular figure in the

classical and post-classical cultures of the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

and

Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

. Almost immediately after his death in 323 BC a body of legend began to accumulate about his exploits and life which, over the centuries, became increasingly fantastic as well as allegorical. Collectively this tradition is called the ''Alexander romance'' and some

recension Recension is the practice of editing or revising a text based on critical analysis. When referring to manuscripts, this may be a revision by another author. The term is derived from Latin ''recensio'' ("review, analysis").

In textual criticism (as ...

s feature such vivid episodes as Alexander ascending through the air to

Paradise

In religion, paradise is a place of exceptional happiness and delight. Paradisiacal notions are often laden with pastoral imagery, and may be cosmogonical or eschatological or both, often compared to the miseries of human civilization: in parad ...

, journeying to the bottom of the sea in a glass bubble, and journeying through the

Land of Darkness

The Land of Darkness (Arabic: دياري الظلمات romanized: ''Diyārī Zulūmāt'') was a mythical land supposedly enshrouded in perpetual darkness. It was usually said to be in Abkhazia, and was officially known as Hanyson or Hamson (or s ...

in search of the

Water of Life (Fountain of Youth).

The earliest

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

manuscripts of the ''Alexander romance'', as they have survived, indicate that it was composed at

Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

in the 3rd century. The original text was lost but was the source of some eighty different versions written in twenty-four different languages. As the ''Alexander romance'' persisted in popularity over the centuries, it was assumed by various neighbouring people. Of particular significance was its incorporation into Jewish and later Christian legendary traditions. In the Jewish tradition Alexander was initially a figure of

satire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming ...

, representing the vain or covetous ruler who is ignorant of larger spiritual truths. Yet their belief in a just, all-powerful God forced Jewish interpreters of the Alexander tradition to come to terms with Alexander's undeniable temporal success. Why would a just, all-powerful God show such favour to an unrighteous ruler? This

theological need, plus acculturation to

Hellenism, led to a more positive Jewish interpretation of the Alexander legacy. In its most neutral form this was typified by having Alexander show deference to either the Jewish people or the symbols of their faith. In having the great conqueror thus acknowledge the essential truth of the Jews' religious, intellectual, or ethical traditions, the prestige of Alexander was harnessed to the cause of Jewish

ethnocentrism. Eventually Jewish writers would almost completely co-opt Alexander, depicting him as a

righteous gentile or even a believing monotheist.

The Christianized peoples of the

Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

, inheritors of both the Hellenic as well as Judaic strands of the ''Alexander romance'', further theologized Alexander until in some stories he was depicted as a

saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

. The Christian legends turned the ancient Greek conqueror Alexander III into Alexander ''"the Believing King"'', implying that he was a believer in monotheism. Eventually elements of the ''Alexander romance'' were combined with

Biblical legends such as

Gog and Magog.

During the period of history during which the ''Alexander romance'' was written, little was known about the true

historical Alexander the Great as most of the history of his conquests had been preserved in the form of folklore and legends. It was not until the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

(1300–1600 AD) that the true history of Alexander III was rediscovered:

Since the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC there has been no age in history, whether in the West or in the East, in which his name and exploits have not been familiar. And yet not only have all contemporary records been lost but even the work based on those records though written some four and a half centuries after his death, the ''Anabasis

Anabasis (from Greek ''ana'' = "upward", ''bainein'' = "to step or march") is an expedition from a coastline into the interior of a country. Anabase and Anabasis may also refer to:

History

* ''Anabasis Alexandri'' (''Anabasis of Alexander''), a ...

'' of Arrian, was totally unknown to the writers of the Middle Ages and became available to Western scholarship only with the Revival of Learning he Renaissance The perpetuation of Alexander's fame through so many ages and amongst so many peoples is due in the main to the innumerable recensions and transmogrifications of a work known as the ''Alexander Romance'' or ''Pseudo-Callisthenes''.[ Boyle 1974.]

Dating and origins of the Alexander legends

The legendary Alexander material originated as early as the time of the

Ptolemaic dynasty (305 BC to 30 BC) and its unknown authors are sometimes referred to as the ''

Pseudo-Callisthenes'' (not to be confused with

Callisthenes of Olynthus, who was Alexander's official historian). The earliest surviving manuscript of the ''Alexander romance'', called the α (

alpha

Alpha (uppercase , lowercase ; grc, ἄλφα, ''álpha'', or ell, άλφα, álfa) is the first letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of one. Alpha is derived from the Phoenician letter aleph , whic ...

)

recension Recension is the practice of editing or revising a text based on critical analysis. When referring to manuscripts, this may be a revision by another author. The term is derived from Latin ''recensio'' ("review, analysis").

In textual criticism (as ...

, can be dated to the 3rd century AD and was written in

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

in

Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

:

There have been many theories regarding the date and sources of this curious work he ''Alexander romance'' According to the most recent authority, ... it was compiled by a Greco-Egyptian writing in Alexandria about A.D. 300. The sources on which the anonymous author drew were twofold. On the one hand he made use of a `romanticized history of Alexander of a highly rhetorical type depending on the Cleitarchus

Cleitarchus or Clitarchus ( el, Κλείταρχος) was one of the historians of Alexander the Great. Son of the historian Dinon of Colophon, he spent a considerable time at the court of Ptolemy Lagus. He was active in the mid to late 4th cent ...

tradition, and with this he amalgamated a collection of imaginary letters derived from an ''Epistolary Romance of Alexander'' written in the first century B.C. He also included two long letters from Alexander to his mother Olympias and his tutor Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

describing his marvellous adventures in India and at the end of the World. These are the literary expression of a living popular tradition and as such are the most remarkable and interesting part of the work.

The

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

variants of the ''Alexander romance'' continued to evolve until, in the 4th century, the Greek legend was translated into

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

by

Julius Valerius Alexander Polemius Julius Valerius Alexander Polemius ( AD) was a translator of the Greek '' Alexander Romance'', a romantic history of Alexander the Great, into Latin under the title ''Res gestae Alexandri Macedonis''. The work is in three books on his birth, acts a ...

(where it is called the ''

Res gestae Alexandri Magni'') and from Latin it spread to all major

vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

languages of

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

in the Middle Ages. Around the same as its translation into Latin, the Greek text was also translated into the

Syriac language

The Syriac language (; syc, / '), also known as Syriac Aramaic (''Syrian Aramaic'', ''Syro-Aramaic'') and Classical Syriac ܠܫܢܐ ܥܬܝܩܐ (in its literary and liturgical form), is an Aramaic language, Aramaic dialect that emerged during ...

and from Syriac it spread to eastern cultures and languages as far afield as China and Southeast Asia. The Syriac legend was the source of an

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

variant called the ''Qisas Dhul-Qarnayn'' (''Tales of Dhul-Qarnayn'')

[ Zuwiyya 2001] and a

Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

variant called the (''Book of Alexander''), as well as

Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian Diaspora, Armenian communities across the ...

and

Ethiopic translations.

[ Zuwiyya 2009.]

The Syriac Legend

The version recorded in Syriac is of particular importance because it was current in the

Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

during the time of the Quran's writing and is regarded as being closely related to the

literary

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

and

linguistic

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

origins of the story of Dhul-Qarnayn in the Quran. The Syriac Alexander legend, as it has survived, consists of six distinct manuscripts, including a

Syriac Christian

Syriac Christianity ( syr, ܡܫܝܚܝܘܬܐ ܣܘܪܝܝܬܐ / ''Mšiḥoyuṯo Suryoyto'' or ''Mšiḥāyūṯā Suryāytā'') is a distinctive branch of Eastern Christianity, whose formative theological writings and traditional liturgies are expr ...

religious legend concerning Alexander in prose text called the Neṣḥānā d-Aleksandrōs, often referred to simply as the Syriac Legend or Syriac Christian Legend, and based on it, a sermon known as the metrical homily (mēmrā), or Alexander song or poem ascribed to the Syriac poet-theologian

Jacob of Serugh

Jacob of Sarug ( syr, ܝܥܩܘܒ ܣܪܘܓܝܐ, ''Yaʿquḇ Sruḡāyâ'', ; his toponym is also spelled ''Serug'' or ''Serugh''; la, Iacobus Sarugiensis; 451 – 29 November 521), also called Mar Jacob, was one of the foremost Syriac poet-the ...

(451–521 AD, also called Mar Jacob), which according to Reinink was actually composed around 629–636.

A key manuscript witness is British Library Add. 25875 (copied 1708–1709), which is the oldest of the five that were known to E.A.W. Budge and used as the base text for his English translation.

The Syriac Legend concentrates on Alexander's journey to the end of the World, where he constructs the ''

Gates of Alexander

The Gates of Alexander were a legendary barrier supposedly built by Alexander the Great in the Caucasus to keep the uncivilized barbarians of the north (typically associated with Gog and Magog in medieval Christian and Islamic writings) from inva ...

'' to enclose the evil nations of ''

Gog and Magog'', while the Metrical Homily describes his journey to the ''

Land of Darkness

The Land of Darkness (Arabic: دياري الظلمات romanized: ''Diyārī Zulūmāt'') was a mythical land supposedly enshrouded in perpetual darkness. It was usually said to be in Abkhazia, and was officially known as Hanyson or Hamson (or s ...

'' to discover the ''

Water of Life'' (Fountain of Youth), as well as his enclosure of Gog and Magog. These legends concerning Alexander are remarkably similar to the story of Dhul-Qarnayn found in the Quran.

[ Stoneman 2003]

The Syriac Legend has been generally dated to between 629 AD and 636 AD. There is evidence in the legend of "''

ex eventu'' knowledge of the

Khazar

The Khazars ; he, כּוּזָרִים, Kūzārīm; la, Gazari, or ; zh, 突厥曷薩 ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that in the late 6th-century CE established a major commercial empire coverin ...

invasion of

Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

in A.D. 629," which suggests that the legend must have been burdened with additions by a

redactor

Redaction is a form of editing in which multiple sources of texts are combined and altered slightly to make a single document. Often this is a method of collecting a series of writings on a similar theme and creating a definitive and coherent wo ...

sometime around 629 AD. The legend appears to have been composed as

propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

in support of Emperor

Heraclius (575–641 AD) shortly after he defeated the Persians in the

Byzantine-Sassanid War of 602–628. It is notable that this manuscript fails to mention the Islamic conquest of

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

in 636 AD by

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

's (570–632 AD) successor,

Caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

Umar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate ...

(590–644 AD). This fact means that the legend might have been recorded before the "cataclysmic event"` that was the

Muslim conquest of Syria

The Muslim conquest of the Levant ( ar, فَتْحُ الشَّام, translit=Feth eş-Şâm), also known as the Rashidun conquest of Syria, occurred in the first half of the 7th century, shortly after the rise of Islam."Syria." Encyclopædia Br ...

and the resulting

surrender of Jerusalem in November 636 AD. That the

Byzantine–Arab Wars would have been referenced in the legend, had it been written after 636 AD, is supported by the fact that in 692 AD a Syriac Christian adaption of the ''Alexander romance'' called the ''

Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius

Written in Syriac in the late seventh century, the ''Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius'' shaped and influenced Christian eschatological thinking in the Middle Ages.Griffith (2008), p. 34.Debié (2005) p. 228.Alexander (1985) p. 13.Jackson (2001) p. ...

'' was indeed written as a response to the Muslim invasions and was

falsely attributed to

St Methodius (?–311 AD); this ''Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius'' equated the evil nations of ''Gog and Magog'' with the Muslim invaders and shaped the

eschatological

Eschatology (; ) concerns expectations of the end of the present age, human history, or of the world itself. The end of the world or end times is predicted by several world religions (both Abrahamic and non-Abrahamic), which teach that nega ...

imagination of

Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

for centuries.

[ The Syriac Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius shows obvious borrowing from the Syriac Legend for its account concerning the barrier against Gog and Magog (especially its description of the Huns as chiefs of thirty escatalogical nations), while the Syriac Apocalypse of Pseudo-Ephrem (dated between 642 and 683 CE) shows borrowing from both the Syriac Legend and the Alexander Poem (i.e. the Metrical Homily).

The manuscripts also contain evidence of lost texts. For example, there is some evidence of a lost pre-Islamic ]Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

version of the translation that is thought to have been an intermediary between the Syriac Christian and the Ethiopic Christian translations. There is also evidence that the Syriac translation was not directly based on the Greek recensions but was based on a lost Pahlavi (Middle Persian

Middle Persian or Pahlavi, also known by its endonym Pārsīk or Pārsīg () in its later form, is a Western Middle Iranian language which became the literary language of the Sasanian Empire. For some time after the Sasanian collapse, Middle ...

) intermediary.[ Brock 1970.]

One scholar (Kevin van Bladel)[ van Bladel, "Alexander Legend in the Qur'an ", 2008: p.175-203] who finds striking similarities between the Quranic verses 18:83-102 and the Syriac legend in support of Emperor Heraclius, dates the work to 629-630 AD or before Muhammad's death, not 629-636 AD.[ The Syriac legend matches many details in the five parts of the verses (Alexander being the two horned one, journey to edge of the world, punishment of evil doers, Gog and Magog, etc.) and also "makes some sense of the cryptic Qur'anic story" being 21 pages (in one edition)][ van Bladel, "Alexander Legend in the Qur'an ", 2008: p.178-79] not 20 verses. (The sun sets in a fetid poisonous ocean—not spring—surrounding the earth, Gog and Magog are Huns, etc.) Van Bladel finds it more plausible that the Syriac legend is the source of the Quranic verses than vice versa, both for linguistic reasons as well as because the Syriac legend was written before the Arab conquests when the Hijazi Muslim community was still remote from and little known to the Mesopotamian site of the legend's creation, whereas Arabs worked as troops and scouts for during the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 and could have been exposed to the legend.[ van Bladel, "Alexander Legend in the Qur'an ", 2008: p.189-90]

Stephen Shoemaker, commenting on the views of Reinink, van Bladel, and Tesei, argues it more likely that most of the text of the current version of the legend existed in a sixth century version, given the stringent timings otherwise required for the legend to influence the Syriac metrical homily and Quranic versions, and the difficulty of otherwise explaining the presence of the first ex-eventu prophecy about the Sabir Hun invasion of 515 CE in the legend, which was already circulating as an apocalyptic revelation in John of Ephesus's ''Lives of the Eastern Saints'' in the sixth century CE.

Search for the water of life

Besides the Dhul Qarnayn episode, Surah al-Kahf

Al-Kahf ( ar, الكهف, ; The Cave) is the List of chapters in the Quran, 18th chapter (sūrah) of the Quran with 110 verses (āyāt). Regarding the timing and contextual background of the revelation (''asbāb al-nuzūl''), it is an earli ...

contains another story which has been connected with legends in the Alexander romance tradition. Tommaso Tesei notes that the story of Alexander's search at the ends of the world for the water of life, featuring his cook and a fish, which appears in various forms in the Syriac metrical homily about Alexander mentioned above, recension β of the Alexander romance (4th/5th century) and in the Babylonian Talmud (Tamid 32a-32b), is "almost unanimously" considered by western scholars to be behind the story of Moses journeying to the junction of the two seas, his servant and the escaped fish earlier in Surah al-Kahf, verses 18:60–65. Besides the full English translation by E.A.W. Budge of both the Metrical Homily and the Syriac Legend,[ an English translation of the relevant part of the Metrical Homily is available in Gabriel Said Reynolds' commentary on the Quran.

]

Philological evidence

The two-horned one

File:Alexander-Coin.jpg, Silver tetradrachmon (ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

coin) issued in the name of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

, depicting Alexander with the horns of Ammon-Ra (242/241 BC, posthumous issue). Displayed at the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

.

The literal translation of the Arabic phrase ''"Dhul-Qarnayn,"'' as written in the Quran, is "the Two-Horned man." Alexander the Great was portrayed in his own time with horns following the iconography of the Egyptian god Ammon-Ra, who held the position of transcendental, self-created creator deity "par excellence".virility

Virility (from the Latin ''virilitas'', manhood or virility, derived from Latin ''vir'', man) refers to any of a wide range of masculine characteristics viewed positively. Virile means "marked by strength or force". Virility is commonly associ ...

due to their rutting behaviour; the horns of Ammon

The horns of Ammon were curling ram horns, used as a symbol of the Egyptian deity Ammon (also spelled Amun or Amon). Because of the visual similarity, they were also associated with the fossils shells of ancient snails and cephalopods, the latter ...

may have also represented the East and West of the Earth, and one of the titles of Ammon

Ammon ( Ammonite: 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''ʻAmān''; he, עַמּוֹן ''ʻAmmōn''; ar, عمّون, ʻAmmūn) was an ancient Semitic-speaking nation occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Arnon and Jabbok, in ...

was "the two-horned." Alexander was depicted with the horns of Ammon as a result of his conquest of ancient Egypt in 332 BC, where the priesthood received him as the son of the god Ammon, who was identified by the ancient Greeks with Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=Genitive case, genitive Aeolic Greek, Boeotian Aeolic and Doric Greek#Laconian, Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=Genitive case, genitive el, Δίας, ''D� ...

, the King of the Gods. The combined deity

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greate ...

Zeus-Ammon was a distinct figure in ancient Greek mythology. According to five historians of antiquity ( Arrian, Curtius, Diodorus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

, Justin

Justin may refer to: People

* Justin (name), including a list of persons with the given name Justin

* Justin (historian), a Latin historian who lived under the Roman Empire

* Justin I (c. 450–527), or ''Flavius Iustinius Augustus'', Eastern Rom ...

, and Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

), Alexander visited the Oracle of Ammon at Siwa in the Libyan

Demographics of Libya is the demography of Libya, specifically covering population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, and religious affiliations, as well as other aspects of the Libyan population. The ...

desert and rumours spread that the Oracle had revealed Alexander's father to be the deity

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greate ...

Ammon, rather than Philip.[Plutarch]

''Alexander'', 27

/ref> Alexander is said by some to have been convinced of his own divinity:

He seems to have become convinced of the reality of his own divinity

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.[divine< ...](_blank)

and to have required its acceptance by others ... The cities perforce complied, but often ironically: the Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

n decree read, '' 'Since Alexander wishes to be a god, let him be a god.' ''

Ancient Greek coins

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cove ...

, such as the coins minted by Alexander's successor Lysimachus (360–281 BC), depict the ruler with the distinctive horns of Ammon

Ammon ( Ammonite: 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''ʻAmān''; he, עַמּוֹן ''ʻAmmōn''; ar, عمّون, ʻAmmūn) was an ancient Semitic-speaking nation occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Arnon and Jabbok, in ...

on his head. Archaeologists have found a large number of different types of ancients coins depicting Alexander the Great with two horns.[ The 4th century BC silver '' tetradrachmon'' ("four '']drachma

The drachma ( el, δραχμή , ; pl. ''drachmae'' or ''drachmas'') was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:

# An ancient Greek currency unit issued by many Greek city states during a period of ten centuries, fr ...

''") coin, depicting a deified

Apotheosis (, ), also called divinization or deification (), is the glorification of a subject to divine levels and, commonly, the treatment of a human being, any other living thing, or an abstract idea in the likeness of a deity. The term has ...

Alexander with two horns, replaced the 5th century BC Athenian

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

silver ''tetradrachmon'' (which depicted the goddess Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarded as the patron and protectress of ...

) as the most widely used coin in the Greek world. After Alexander's conquests, the ''drachma'' was used in many of the Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

kingdoms in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, including the Ptolemaic Ptolemaic is the adjective formed from the name Ptolemy, and may refer to:

Pertaining to the Ptolemaic dynasty

* Ptolemaic dynasty, the Macedonian Greek dynasty that ruled Egypt founded in 305 BC by Ptolemy I Soter

* Ptolemaic Kingdom

Pertaining ...

kingdom in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

. The Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

unit of currency known as the '' dirham'', known from pre-Islamic times up to the present day, inherited its name from the ''drachma''. In the late 2nd century BC, silver coins depicting Alexander with ram

Ram, ram, or RAM may refer to:

Animals

* A male sheep

* Ram cichlid, a freshwater tropical fish

People

* Ram (given name)

* Ram (surname)

* Ram (director) (Ramsubramaniam), an Indian Tamil film director

* RAM (musician) (born 1974), Dutch

* ...

horns were used as a principal coinage in Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

and were issued by an Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

ruler by the name of Abi'el who ruled in the south-eastern region of the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate ...

.

File:Alexander-Heraclius_Stele.png, 7th century CE stele depicting Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

with horns discovered in 2018. Published by the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus.

In 2018, excavations led by Dr. Eleni Procopiou at Katalymata ton Plakoton, an Early Byzantine site within the Akrotiri Peninsula on Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, discovered a 7th Century CE depiction of Alexander the Great with horns. Known as the "Alexander-Heraclius Stele". Professor Sean Anthony regards it as significant, providing "seventh-century Byzantine iconography of Alexander with two horns that is contemporary with the Qurʾan"[Charles A. Stewart in "A Byzantine Image of Alexander: Literature in Stone," Report of the Department of Antiquities Cyprus 2017 (Nicosia 2018): 1-45 cited by Professor Shaun W. Anthony of Ohio State University on ]

In 1971, Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

archeologist B.M. Mozolevskii discovered an ancient Scythian

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

kurgan

A kurgan is a type of tumulus constructed over a grave, often characterized by containing a single human body along with grave vessels, weapons and horses. Originally in use on the Pontic–Caspian steppe, kurgans spread into much of Central As ...

(burial mound) containing many treasures. The burial site was constructed in the 4th century BC near the city of Pokrov and is given the name '' Tovsta Mohyla'' (another name is ''Babyna Mogila''). Amongst the artifacts excavated at this site were four silver gilded phalera (ancient Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

military medals). Two of the four medals are identical and depict the head of a bearded man with two horns, while the other two medals are also identical and depict the head of a clean-shaven man with two horns. According to a recent theory, the bearded figure with horns is actually Zeus-Ammon and the clean-shaved figure is none other than Alexander the Great.

Alexander has also been identified, since ancient times, with the horned figure in the Old Testament in the prophecy of Daniel 8

Daniel 8 is the eighth chapter of the Book of Daniel. It tells of Daniel's vision of a two-horned ram destroyed by a one-horned goat, followed by the history of the "little horn", which is Daniel's code-word for the Greek king Antiochus IV Epiph ...

who overthrows the kings of Media and Persia. In the prophecy, Daniel

Daniel is a masculine given name and a surname of Hebrew origin. It means "God is my judge"Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 68. (cf. Gabriel—"God is my strength" ...

has a vision of a ram with two long horns and verse 20 explains that ''"The ram which thou sawest having two horns is the kings of Media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Media (communication), tools used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Broadcast media, communications delivered over mass e ...

and Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

."'':

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

7–100 AD in his '' Antiquities of the Jews'' xi, 8, 5 tells of a visit that Alexander is purported to have made to Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, where he met the high priest Jaddua and the assembled Jews, and was shown the book of Daniel in which it was prophesied that some one of the Greeks would overthrow the empire of Persia. Alexander believed himself to be the one indicated, and was pleased. The pertinent passage in Daniel would seem to be VIII. 3–8 which tells of the overthrow of the two-horned ram by the one-horned goat, the one horn of the goat being broken in the encounter ...The interpretation of this is given further ... "The ram which thou sawest that had the two horns, they are the kings of Media and Persia. And the rough he-goat is the king of Greece." This identification is accepted by the church fathers ...

The Christian Syriac Syriac may refer to:

*Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages a ...

version of the ''Alexander romance,'' in the sermon by Jacob of Serugh

Jacob of Sarug ( syr, ܝܥܩܘܒ ܣܪܘܓܝܐ, ''Yaʿquḇ Sruḡāyâ'', ; his toponym is also spelled ''Serug'' or ''Serugh''; la, Iacobus Sarugiensis; 451 – 29 November 521), also called Mar Jacob, was one of the foremost Syriac poet-the ...

, describes Alexander as having been given horns of iron by God. The legend describes Alexander (as a Christian king) bowing himself in prayer, saying:

O God ... I know in my mind that thou hast exalted me above all kings, and ''thou hast made me horns upon my head, wherewith I might thrust down the kingdoms of the world''...I will magnify thy name, O Lord, forever ... And if the Messiah, who is the Son of God esus

Esus, Hesus, or Aisus was a Brittonic and Gaulish god known from two monumental statues and a line in Lucan's '' Bellum civile''.

Name

T. F. O'Rahilly derives the theonym ''Esus'', as well as ''Aoibheall'', ''Éibhleann'', ''Aoife'', and ...

comes in my days, I and my troops will worship Him...

While the ''Syriac Legend'' references the horns of Alexander, it consistently refers to the hero by his Greek name, not using a variant epithet. The use of the Islamic epithet "Dhu al-Qarnayn", the "two-horned", first occurred in the Quran.

In Christian Alexander legends written in Ethiopic (an ancient South Semitic

South Semitic is a putative branch of the Semitic languages, which form a branch of the larger Afro-Asiatic language family, found in (North and East) Africa and Western Asia.

History

The "homeland" of the South Semitic languages is widely ...

language) between the 14th and the 16th century, Alexander the Great is always explicitly referred to using the epithet

An epithet (, ), also byname, is a descriptive term (word or phrase) known for accompanying or occurring in place of a name and having entered common usage. It has various shades of meaning when applied to seemingly real or fictitious people, di ...

the "Two Horned." A passage from the Ethiopic Christian legend describes the Angel of the Lord

The (or an) angel of the ( he, מַלְאַךְ יְהוָה '' mal’āḵ YHWH'' "messenger of Yahweh") is an entity appearing repeatedly in the Tanakh (Old Testament) on behalf of the God of Israel.

The guessed term ''YHWH'', which occurs ...

calling Alexander by this name:

Then God, may He be blessed and exalted! put it into the heart of the Angel to call ''Alexander 'Two-horned,' '' ... And Alexander said unto him, ' ''Thou didst call me by the name Two-horned,'' but my name is Alexander ... and I thought that thou hadst cursed me by calling me by this name.' The angel spake unto him, saying, 'O man, I did not curse thee by ''the name by which thou and the works that thou doest are known.'' Thou hast come unto me, and I praise thee because, from the east to the west, the whole earth hath been given unto thee ...'

References to Alexander's supposed horns are found in literature ranging many different languages, regions and centuries:

The horns of Alexander ... have had a varied symbolism. They represent him as a god, as a son of a god, as a prophet and propagandist of the Most High, as something approaching the role of a messiah, and also as the champion of Allah. They represent him as a world conqueror, who subjugated the two horns or ends of the world, the lands of the rising and of the setting sun ...

For these reasons, among others, the Quran's Arabic epithet "Dhul-Qarnayn," literally meaning "the two-horned one," is interpreted as a reference to Alexander the Great.

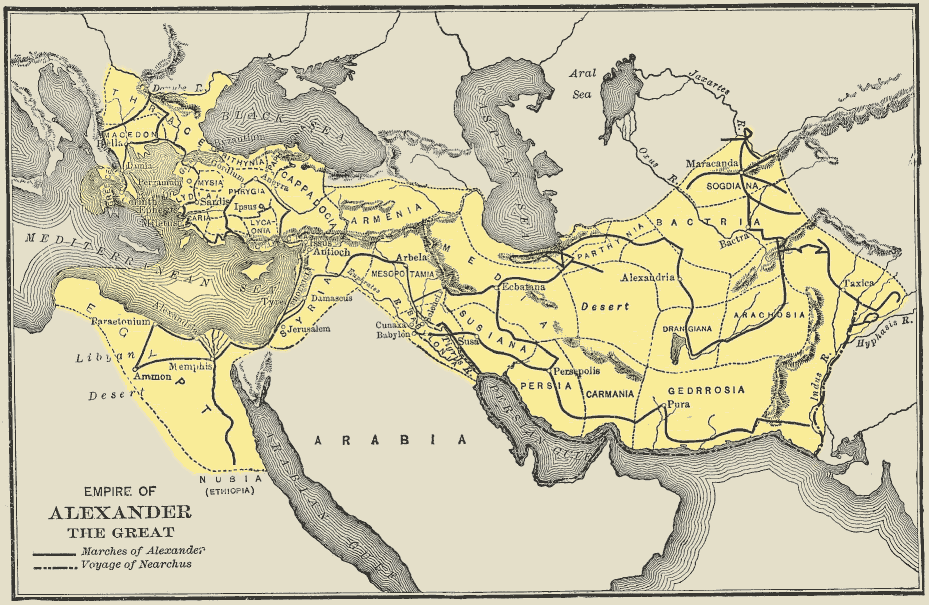

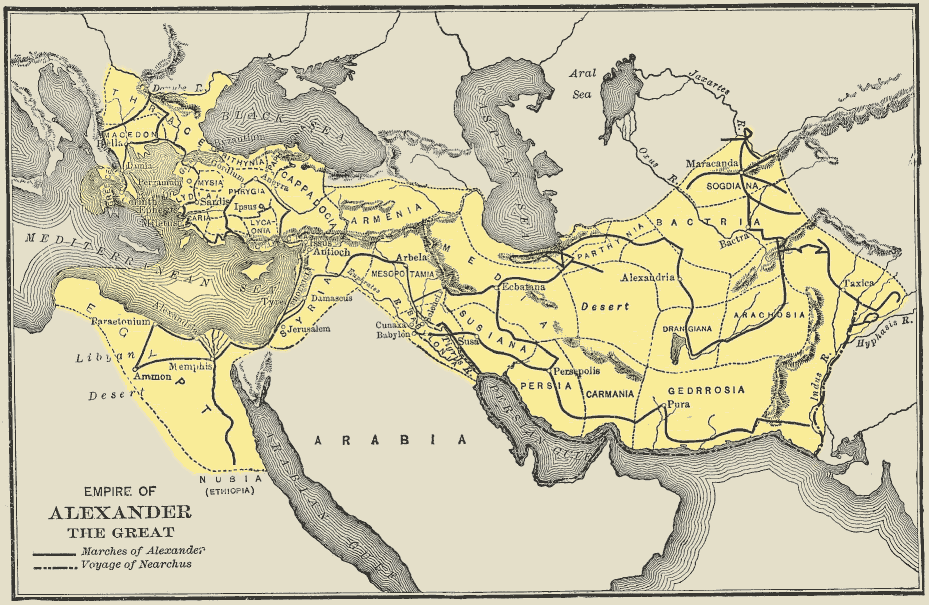

Alexander's Wall

Early accounts of Alexander's Wall

The building of gates in the Caucasus Mountains

The Caucasus Mountains,

: pronounced

* hy, Կովկասյան լեռներ,

: pronounced

* az, Qafqaz dağları, pronounced

* rus, Кавка́зские го́ры, Kavkázskiye góry, kɐfˈkasːkʲɪje ˈɡorɨ

* tr, Kafkas Dağla ...

by Alexander to repel the barbarian peoples identified with Gog and Magog has ancient provenance and the wall is known as the Gates of Alexander

The Gates of Alexander were a legendary barrier supposedly built by Alexander the Great in the Caucasus to keep the uncivilized barbarians of the north (typically associated with Gog and Magog in medieval Christian and Islamic writings) from inva ...

or the Caspian Gates

The Gates of Alexander were a legendary barrier supposedly built by Alexander the Great in the Caucasus to keep the uncivilized barbarians of the north (typically associated with Gog and Magog in medieval Christian and Islamic writings) from i ...

. The name Caspian Gates originally applied to the narrow region at the southeast corner of the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central Asia ...

, through which Alexander actually marched in the pursuit of Bessus in 329 BC, although he did not stop to fortify it. It was transferred to the passes through the Caucasus, on the other side of the Caspian, by the more fanciful historians of Alexander. The Jewish historian Flavius Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

(37–100 AD) mentions that:

...a nation of the Alans, whom we have previously mentioned elsewhere as being Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

... travelled through a passage which King Alexander he Great

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

shut up with iron gates.

Josephus also records that the people of Magog, the Magogites, were synonymous with the Scythians. According to Andrew Runni Anderson, this merely indicates that the main elements of the story were already in place six centuries before the Quran's revelation, not that the story itself was known in the cohesive form apparent in the Quranic account. Similarly, St. Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian priest, confessor, theologian, and historian; he is com ...

(347–420 AD), in his ''Letter 77'', mentions that,

The hordes of the Huns had poured forth all the way from Maeotis

The Sea of Azov ( Crimean Tatar: ''Azaq deñizi''; russian: Азовское море, Azovskoye more; uk, Азовське море, Azovs'ke more) is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, ...

(they had their haunts between the icy Tanais

Tanais ( el, Τάναϊς ''Tánaïs''; russian: Танаис) was an ancient Greek city in the Don river delta, called the Maeotian marshes in classical antiquity. It was a bishopric as Tana and remains a Latin Catholic titular see as Tana ...

and the rude Massagetae

The Massagetae or Massageteans (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ), also known as Sakā tigraxaudā (Old Persian: , "wearer of pointed caps") or Orthocorybantians (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ),: As for the term “Orthocorybantii”, this is a translati ...

, ''where the gates of Alexander

The Gates of Alexander were a legendary barrier supposedly built by Alexander the Great in the Caucasus to keep the uncivilized barbarians of the north (typically associated with Gog and Magog in medieval Christian and Islamic writings) from inva ...

keep back the wild peoples behind the Caucasus'').

In his Commentary on Ezekiel (38:2), Jerome identifies the nations located beyond the Caucasus mountains

The Caucasus Mountains,

: pronounced

* hy, Կովկասյան լեռներ,

: pronounced

* az, Qafqaz dağları, pronounced

* rus, Кавка́зские го́ры, Kavkázskiye góry, kɐfˈkasːkʲɪje ˈɡorɨ

* tr, Kafkas Dağla ...

and near Lake Maeotis

The Sea of Azov ( Crimean Tatar: ''Azaq deñizi''; russian: Азовское море, Azovskoye more; uk, Азовське море, Azovs'ke more) is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, ...

as Gog and Magog. Thus the Gates of Alexander

The Gates of Alexander were a legendary barrier supposedly built by Alexander the Great in the Caucasus to keep the uncivilized barbarians of the north (typically associated with Gog and Magog in medieval Christian and Islamic writings) from inva ...

legend was combined with the legend of Gog and Magog from the Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament (and consequently the final book of the Christian Bible). Its title is derived from the first word of the Koine Greek text: , meaning "unveiling" or "revelation". The Book of R ...

. It has been suggested that the incorporation of the Gog and Magog legend into the ''Alexander romance'' was prompted by the invasion of the Huns across the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

mountains in 395 AD into Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

.

Alexander's Wall in Christian legends

Christian legends speak of the Caspian Gates (Gates of Alexander), also known as Alexander's wall, built by Alexander the Great in the Caucasus mountains

The Caucasus Mountains,

: pronounced

* hy, Կովկասյան լեռներ,

: pronounced

* az, Qafqaz dağları, pronounced

* rus, Кавка́зские го́ры, Kavkázskiye góry, kɐfˈkasːkʲɪje ˈɡorɨ

* tr, Kafkas Dağla ...

. Several variations of the legend can be found. In the story, Alexander the Great built a gate of iron between two mountains, at the end of the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

, to prevent the armies of Gog and Magog from ravaging the plains. The Christian legend was written in Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

shortly before the Quran's writing and closely parallels the story of Dhul-Qarnayn. The legend describes an apocryphal letter from Alexander to his mother, wherein he writes:

I petitioned the exalted Deity, and he heard my prayer. And the exalted Deity commanded the two mountains and they moved and approached each other to a distance of twelve ells, and there I made ... copper gates 12 ells broad, and 60 ells high, and smeared them over within and without with copper ... so that neither fire nor iron, nor any other means should be able to loosen the copper; ... Within these gates, I made another construction of stones ... And having done this I finished the construction by putting mixed tin and lead over the stones, and smearing .... over the whole, so that no one might be able to do anything against the gates. I called them the Caspian Gates. Twenty and two Kings did I shut up therein.

These pseudepigraphic

Pseudepigrapha (also anglicized as "pseudepigraph" or "pseudepigraphs") are falsely attributed works, texts whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past.Bauckham, Richard; "Pseu ...

letters from Alexander to his mother Olympias and his tutor Aristotle, describing his marvellous adventures at the end of the World, date back to the original Greek recension α written in the 4th century in Alexandria. The letters are "the literary expression of a living popular tradition" that had been evolving for at least three centuries before the Quran was written.

Medieval accounts of Alexander's Wall

Several historical figures, both Muslim and Christian, searched for Alexander's Gate and several different identifications were made with actual walls. During the

Several historical figures, both Muslim and Christian, searched for Alexander's Gate and several different identifications were made with actual walls. During the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, the Gates of Alexander story was included in travel literature such as the ''Travels of Marco Polo

''Book of the Marvels of the World'' (Italian: , lit. 'The Million', deriving from Polo's nickname "Emilione"), in English commonly called ''The Travels of Marco Polo'', is a 13th-century travelogue written down by Rustichello da Pisa from sto ...

'' (1254–1324 AD) and the ''Travels of Sir John Mandeville

Sir John Mandeville is the supposed author of ''The Travels of Sir John Mandeville'', a travel memoir which first circulated between 1357 and 1371. The earliest-surviving text is in French.

By aid of translations into many other languages, the ...

''. The ''Alexander romance'' identified the Gates of Alexander, variously, with the Pass of Dariel, the Pass of Derbent, the Great Wall of Gorgan

The Great Wall of Gorgan is a Sasanian-era defense system located near modern Gorgan in the Golestān Province of northeastern Iran, at the southeastern corner of the Caspian Sea. The western, Caspian Sea, end of the wall is near the remains ...

and even the Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand ''li'' wall") is a series of fortifications that were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against various nomadic gro ...

. In the legend's original form, Alexander's Gates are located at the Pass of Dariel. In later versions of the Christian legends, dated to around the time of Emperor Heraclius (575–641 AD), the Gates are instead located in Derbent

Derbent (russian: Дербе́нт; lez, Кьвевар, Цал; az, Дәрбәнд, italic=no, Dərbənd; av, Дербенд; fa, دربند), formerly romanized as Derbend, is a city in Dagestan, Russia, located on the Caspian Sea. It i ...

, a city situated on a narrow strip of land between the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus mountains, where an ancient Sassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

fortification was mistakenly identified with the wall built by Alexander. In the ''Travels of Marco Polo

''Book of the Marvels of the World'' (Italian: , lit. 'The Million', deriving from Polo's nickname "Emilione"), in English commonly called ''The Travels of Marco Polo'', is a 13th-century travelogue written down by Rustichello da Pisa from sto ...

'', the wall in Derbent is identified with the Gates of Alexander. The Gates of Alexander

The Gates of Alexander were a legendary barrier supposedly built by Alexander the Great in the Caucasus to keep the uncivilized barbarians of the north (typically associated with Gog and Magog in medieval Christian and Islamic writings) from inva ...

are most commonly identified with the Caspian Gates of Derbent whose thirty north-looking towers used to stretch for forty kilometres between the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central Asia ...

and the Caucasus Mountains

The Caucasus Mountains,

: pronounced

* hy, Կովկասյան լեռներ,

: pronounced

* az, Qafqaz dağları, pronounced

* rus, Кавка́зские го́ры, Kavkázskiye góry, kɐfˈkasːkʲɪje ˈɡorɨ

* tr, Kafkas Dağla ...

, effectively blocking the passage across the Caucasus.[ Bretschneider 1876.] Later historians would regard these legends as false:

The gate itself had wandered from the Caspian Gates to the pass of Dariel, from the pass of Dariel to the pass of Derbend erbent

Erbent (also known as Yerbent or Ýerbent) is a village in Ahal Province in central Turkmenistan. The village is located in the Karakum Desert. It is the largest settlement on the road between Ashgabat and Daşoguz, which are located near the so ...

as well as to the far north; nay, it had travelled even as far as remote eastern or north-eastern Asia, gathering in strength and increasing in size as it went, and actually carrying the mountains of Caspia with it. Then, as the full light of modern day come on, the ''Alexander Romance'' ceased to be regarded as history, and with it Alexander's Gate passed into the realm of fairyland.[

]

In the Muslim world, several expeditions were undertaken to try to find and study Alexanders's wall, specifically the Caspian Gates of Derbent. An early expedition to Derbent was ordered by the Caliph Umar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate ...

(586–644 AD) himself, during the Arab conquest of Armenia

The Muslim conquest of parts of Armenia and Anatolia was a part of the Muslim conquests after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad in 632 CE.

Persarmenia had fallen to the Arab Rashidun Caliphate by 645 CE. Byzantine Armenia was alrea ...

where they heard about Alexander's Wall in Derbent from the conquered Christian Armenians. Umar's expedition was recorded by the renowned exegetes of the Quran, Al-Tabarani

Abū al-Qāsim Sulaymān ibn Aḥmad ibn Ayyūb ibn Muṭayyir al-Lakhmī al-Shāmī al-Ṭabarānī (Arabic: أبو القاسم سليمان بن أحمد بن أيوب بن مطير اللَّخمي الشامي الطبراني) (AH 260/c. 87 ...

(873–970 AD) and Ibn Kathir (1301–1373 AD), and by the Muslim geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi

Yāqūt Shihāb al-Dīn ibn-ʿAbdullāh al-Rūmī al-Ḥamawī (1179–1229) ( ar, ياقوت الحموي الرومي) was a Muslim scholar of Byzantine Greek ancestry active during the late Abbasid period (12th-13th centuries). He is known for ...

(1179–1229 AD):

... Umar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate ...

sent ... in 22 A.H. 43 AD... an expedition to Derbent ussia... `Abdur Rahman bin Rabi`ah as appointedas the chief of his vanguard. When 'Abdur Rehman entered Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

, the ruler Shehrbaz surrendered without fighting. Then when `Abdur Rehman wanted to advance towards Derbent, Shehrbaz uler of Armeniainformed him that he had already gathered full information about the wall built by Dhul-Qarnain, through a man, who could supply all the necessary details ...Tafsir al-Tabari

''Jāmiʿ al-bayān ʿan taʾwīl āy al-Qurʾān'' (, also written with ''fī'' in place of ''ʿan''), popularly ''Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī'' ( ar, تفسير الطبري), is a Sunni ''tafsir'' by the Persian scholar Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (8 ...

, Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, Vol. III, pp. 235–239

Two hundred years later, the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

Caliph Al-Wathiq

Abū Jaʿfar Hārūn ibn Muḥammad ( ar, أبو جعفر هارون بن محمد المعتصم; 17 April 812 – 10 August 847), better known by his regnal name al-Wāthiq bi’llāh (, ), was an Abbasid caliph who reigned from 842 until 84 ...

(?–847 AD) dispatched an expedition to study the wall of Dhul-Qarnain in Derbent, Russia. The expedition was led by Sallam-ul-Tarjuman, whose observations were recorded by Yaqut al-Hamawi

Yāqūt Shihāb al-Dīn ibn-ʿAbdullāh al-Rūmī al-Ḥamawī (1179–1229) ( ar, ياقوت الحموي الرومي) was a Muslim scholar of Byzantine Greek ancestry active during the late Abbasid period (12th-13th centuries). He is known for ...

and by Ibn Kathir:

...this expedition reached ... the Caspian territory. From there they arrived at Derbent and saw the wall f Dhul-Qarnayn[Mu'jam-ul-Buldan, Yaqut al-Hamawi]

The Muslim geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi

Yāqūt Shihāb al-Dīn ibn-ʿAbdullāh al-Rūmī al-Ḥamawī (1179–1229) ( ar, ياقوت الحموي الرومي) was a Muslim scholar of Byzantine Greek ancestry active during the late Abbasid period (12th-13th centuries). He is known for ...

further confirmed the same view in a number of places in his book on geography; for instance under the heading "Khazar" (Caspian) he writes:

This territory adjoins the Wall of Dhul-Qarnain just behind Bab-ul-Abwab, which is also called Derbent.

The Caliph Harun al-Rashid

Abu Ja'far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi ( ar

, أبو جعفر هارون ابن محمد المهدي) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (; or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid ( ar, هَارُون الرَشِيد, translit=Hārūn ...

(763 – 809 AD) even spent some time living in Derbent. Not all Muslim travellers and scholars, however, associated Dhul-Qarnayn's wall with the Caspian Gates of Derbent. For example, the Muslim explorer Ibn Battuta (1304–1369 AD) travelled to China on order of the Sultan of Delhi

The following list of Indian monarchs is one of several lists of incumbents. It includes those said to have ruled a portion of the Indian subcontinent, including Sri Lanka.

The earliest Indian rulers are known from epigraphical sources fou ...

, Muhammad bin Tughluq

Muhammad bin Tughluq (1290 – 20 March 1351) was the eighteenth Sultan of Delhi. He reigned from February 1325 until his death in 1351. The sultan was the eldest son of Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq, founder of the Tughlaq dynasty. In 1321, the youn ...

and he comments in his travel log that "Between it Zaitun_in_Fujian.html"_;"title="Quanzhou.html"_;"title="he_city_of_Quanzhou">Zaitun_in_Fujian">Quanzhou.html"_;"title="he_city_of_Quanzhou">Zaitun_in_Fujian.html" ;"title="Quanzhou">Zaitun_in_Fujian.html" ;"title="Quanzhou.html" ;"title="he city of Quanzhou">Zaitun in Fujian">Quanzhou.html" ;"title="he city of Quanzhou">Zaitun in Fujian">Quanzhou">Zaitun_in_Fujian.html" ;"title="Quanzhou.html" ;"title="he city of Quanzhou">Zaitun in Fujian">Quanzhou.html" ;"title="he city of Quanzhou">Zaitun in Fujianand the rampart of Yajuj and Majuj og and Magogis sixty days' travel."[Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb, H. A. R. Gibb and C. F. Beckingham, trans. ''The Travels of Ibn Battuta, A.D. 1325–1354'' (Vol. IV). London: Hakluyt Society, 1994 (), p. 896] The translator of the travel log notes that Ibn Battuta confused the Great Wall of China with that supposedly built by Dhul-Qarnayn.[Gibb, p. 896, footnote #30]

Gog and Magog

In the Quran, it is none other than the Gog and Magog people whom Dhul-Qarnayn has enclosed behind a wall, preventing them from invading the Earth. In Islamic eschatology

Eschatology (; ) concerns expectations of the end of the present age, human history, or of the world itself. The end of the world or end times is predicted by several world religions (both Abrahamic and non-Abrahamic), which teach that nega ...

, before the Day of Judgement Gog and Magog will destroy this gate, allowing them to ravage the Earth, as it is described in the Quran:

:Until, when Gog and Magog are let loose rom their barrier and they swiftly swarm from every mound. And the true promise ay of Resurrectionshall draw near f fulfilment Then hen mankind is resurrected from their graves you shall see the eyes of the disbelievers fixedly stare in horror. hey will say,‘Woe to us! We were indeed heedless of this; nay, but we were wrongdoers.’ (Quran 21:96–97. Note that the phrases in square brackets are not in the Arabic original.)

Gog and Magog in Christian legends

In the Syriac Christian legends, Alexander the Great encloses the Gog and Magog horde behind a mighty gate between two mountains, preventing Gog and Magog from invading the Earth. In addition, it is written in the Christian legend that in the

In the Syriac Christian legends, Alexander the Great encloses the Gog and Magog horde behind a mighty gate between two mountains, preventing Gog and Magog from invading the Earth. In addition, it is written in the Christian legend that in the end times

Eschatology (; ) concerns expectations of the end of the present age, human history, or of the world itself. The end of the world or end times is predicted by several world religions (both Abrahamic and non-Abrahamic), which teach that nega ...

God will cause the Gate of Gog and Magog to be destroyed, allowing the Gog and Magog horde to ravage the Earth;

The Lord spake by the hand of the angel, aying...The gate of the north shall be opened on the day of the end of the world, and on that day shall evil go forth on the wicked ... The earth shall quake and this door ate

Ate or ATE may refer to:

Organizations

* Active Training and Education Trust, a not-for-profit organization providing "Superweeks", holidays for children in the United Kingdom

* Association of Technical Employees, a trade union, now called the Nat ...

which thou lexanderhast made be opened ... and anger with fierce wrath shall rise up on mankind and the earth ... shall be laid waste ... And the nations that is within this gate shall be roused up, and also the host of Agog and the peoples of Magog og and Magogshall be gathered together. These peoples, the fiercest of all creatures.

The Christian Syriac legend describes a flat Earth

The flat-Earth model is an archaic and scientifically disproven conception of Earth's shape as a plane or disk. Many ancient cultures subscribed to a flat-Earth cosmography, including Greece until the classical period (5th century BC), t ...

orbited by the sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

and surrounded by the Paropamisadae

Paropamisadae or Parapamisadae (Greek: Παροπαμισάδαι) was a satrapy of the Alexandrian Empire in modern Afghanistan and Pakistan, which largely coincided with the Achaemenid province of Parupraesanna. It consisted of the districts ...

(Hindu Kush) mountains. The Paropamisadae mountains are in turn surrounded by a narrow tract of land which is followed by a treacherous Ocean sea called Okeyanos. It is within this tract of land between the Paropamisadae

Paropamisadae or Parapamisadae (Greek: Παροπαμισάδαι) was a satrapy of the Alexandrian Empire in modern Afghanistan and Pakistan, which largely coincided with the Achaemenid province of Parupraesanna. It consisted of the districts ...

mountains and Okeyanos that Alexander encloses Gog and Magog, so that they could not cross the mountains and invade the Earth. The legend describes "the old wise men" explaining this geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

and cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

of the Earth to Alexander, and then Alexander setting out to enclose Gog and Magog behind a mighty gate between a narrow passage at the end of the flat Earth:

The old men say, "Look, my lord the king, and see a wonder, this mountain which God has set as a great boundary." King Alexander the son of Philip said, "How far is the extent of this mountain?" The old men say, "Beyond India it extends in its appearance." The king said, "How far does this side come?" The old men say, "Unto all the end of the earth." And wonder seized the great king at the council of the old men ... And he had it in his mind to make there a great gate. His mind was full of spiritual thoughts, while taking advice from the old men, the dwellers in the land. He looked at the mountain which encircled the whole world ... The king said, "Where have the hosts f Gog and Magogcome forth to plunder the land and all the world from of old?" They show him a place in the middle of the mountains, a narrow pass which had been constructed by God ...

Flat Earth beliefs in the Early Christian Church varied and the Fathers of the Church shared different approaches. Those of them who were more close to Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

and Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

's visions, like Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an Early Christianity, early Christian scholar, ...

, shared peacefully the belief in a spherical Earth

Spherical Earth or Earth's curvature refers to the approximation of figure of the Earth as a sphere.

The earliest documented mention of the concept dates from around the 5th century BC, when it appears in the writings of Greek philosophers. ...

. A second tradition, including St Basil

Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great ( grc, Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας, ''Hágios Basíleios ho Mégas''; cop, Ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲃⲁⲥⲓⲗⲓⲟⲥ; 330 – January 1 or 2, 379), was a bishop of Cae ...

and St Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

, accepted the idea of the round Earth and the radial gravity, but in a critical way. In particular they pointed out a number of doubts about the antipodes and the physical reasons of the radial gravity. However, a flat Earth approach was more or less shared by all the Fathers coming from the Syriac area, who were more inclined to follow the letter of the Old Testament. Diodore of Tarsus

Diodore of Tarsus (Greek Διόδωρος ὁ Ταρσεύς; died c. 390) was a Christian bishop, a monastic reformer, and a theologian. A strong supporter of the orthodoxy of Nicaea, Diodore played a pivotal role in the Council of Constantin ...

(?–390 AD), Cosmas Indicopleustes

Cosmas Indicopleustes ( grc-x-koine, Κοσμᾶς Ἰνδικοπλεύστης, lit=Cosmas who sailed to India; also known as Cosmas the Monk) was a Greek merchant and later hermit from Alexandria of Egypt. He was a 6th-century traveller who ma ...

(6th century), and Chrysostom (347–407 AD) belonged to this flat Earth tradition.

Prophecy about the Sabir Huns invasion (514 CE)

The first ex-eventu prophecy about Gog and Magog in the Syriac Christian Legend relates to the invasion of the Sabir Huns in 514-15 CE (immediately before the second ex-eventu prophecy about the Khazars discussed below). In a paper supporting van Bladel's thesis on the direct dependency of the Dhu'l Qarnayn story on the Syriac Legend, Tommaso Tesei nevertheless highlights Károly Czeglédy's identification that this first prophecy already had a 6th-century CE existence as an apocalytic revelation involving the arrival of the Huns in a passage of the Lives of the Eastern Saints by John of Ephesus (d. 586 ca.).

Prophecy about the Khazars invasion (627 CE)

In the Christian ''Alexander romance'' literature, Gog and Magog were sometimes associated with the Khazars