Insects (from

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

') are

hexapod invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s of the

class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

Insecta. They are the largest group within the

arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

phylum

In biology, a phylum (; : phyla) is a level of classification, or taxonomic rank, that is below Kingdom (biology), kingdom and above Class (biology), class. Traditionally, in botany the term division (taxonomy), division has been used instead ...

. Insects have a

chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

ous

exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

, a three-part body (

head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

,

thorax

The thorax (: thoraces or thoraxes) or chest is a part of the anatomy of mammals and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen.

In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main di ...

and

abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the gut, belly, tummy, midriff, tucky, or stomach) is the front part of the torso between the thorax (chest) and pelvis in humans and in other vertebrates. The area occupied by the abdomen is called the abdominal ...

), three pairs of jointed

legs,

compound eye

A compound eye is a Eye, visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidium, ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens (anatomy), lens, and p ...

s, and a pair of

antennae. Insects are the most diverse group of animals, with more than a million described

species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

; they represent more than half of all animal species.

The insect

nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the complex system, highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its behavior, actions and sense, sensory information by transmitting action potential, signals to and from different parts of its body. Th ...

consists of a

brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

and a

ventral nerve cord

The ventral nerve cord is a major structure of the invertebrate central nervous system. It is the functional equivalent of the vertebrate spinal cord. The ventral nerve cord coordinates neural signaling from the brain to the body and vice ve ...

. Most insects reproduce

by laying eggs. Insects

breathe air through a system of

paired openings along their sides, connected to

small tubes that take air directly to the tissues. The blood therefore does not carry oxygen; it is only partly contained in vessels, and some circulates in an open

hemocoel. Insect vision is mainly through their

compound eye

A compound eye is a Eye, visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidium, ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens (anatomy), lens, and p ...

s, with additional small

ocelli. Many insects can hear, using

tympanal organs, which may be on the legs or other parts of the body. Their

sense of smell is via receptors, usually on the antennae and the mouthparts.

Nearly all insects hatch from

eggs. Insect growth is constrained by the inelastic exoskeleton, so development involves a series of

molts. The immature stages often differ from the adults in structure, habit, and habitat. Groups that undergo

four-stage metamorphosis often have a nearly immobile

pupa. Insects that undergo

three-stage metamorphosis lack a pupa, developing through a series of increasingly adult-like

nymphal stages. The higher level relationship of the

insects

Insects (from Latin ') are hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs of jointed ...

is unclear. Fossilized insects of enormous size have been found from the

Paleozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma a ...

Era, including

giant dragonfly-like insects with wingspans of . The most diverse insect groups appear to have

coevolved with

flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (). The term angiosperm is derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek words (; 'container, vessel') and (; 'seed'), meaning that the seeds are enclosed with ...

s.

Adult insects typically move about by walking and flying; some can swim. Insects are the only invertebrates that can achieve sustained powered flight;

insect flight

Insects are the only group of invertebrates that have evolved insect wing, wings and flight. Insects first flew in the Carboniferous, some 300 to 350 million years ago, making them the first animals to evolve flight. Wings may have evolved from ...

evolved just once. Many insects are at least partly

aquatic, and have

larva

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase ...

e with gills; in some species, the adults too are aquatic. Some species, such as

water striders, can walk on the surface of water. Insects are mostly solitary, but some, such as

bees,

ant

Ants are Eusociality, eusocial insects of the Family (biology), family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the Taxonomy (biology), order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from Vespoidea, vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cre ...

s and

termite

Termites are a group of detritivore, detritophagous Eusociality, eusocial cockroaches which consume a variety of Detritus, decaying plant material, generally in the form of wood, Plant litter, leaf litter, and Humus, soil humus. They are dist ...

s, are

social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives fro ...

and live in large, well-organized

colonies. Others, such as

earwigs, provide maternal care, guarding their eggs and young. Insects can communicate with each other in a variety of ways. Male

moth

Moths are a group of insects that includes all members of the order Lepidoptera that are not Butterfly, butterflies. They were previously classified as suborder Heterocera, but the group is Paraphyly, paraphyletic with respect to butterflies (s ...

s can sense the

pheromone

A pheromone () is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavio ...

s of female moths over great distances. Other species communicate with sounds:

crickets stridulate, or rub their wings together, to attract a mate and repel other males.

Lampyrid beetle

Beetles are insects that form the Taxonomic rank, order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Holometabola. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 40 ...

s communicate with light.

Humans regard many insects as

pests

PESTS was an anonymous American activist group formed in 1986 to critique racism, tokenism, and exclusion in the art world. PESTS produced newsletters, posters, and other print material highlighting examples of discrimination in gallery represent ...

, especially those that damage crops, and attempt to control them using

insecticide

Insecticides are pesticides used to kill insects. They include ovicides and larvicides used against insect eggs and larvae, respectively. The major use of insecticides is in agriculture, but they are also used in home and garden settings, i ...

s and other techniques. Others are

parasitic, and may act as

vectors of

diseases

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that are asso ...

. Insect

pollinators are essential to the reproduction of many flowering plants and so to their ecosystems. Many insects are ecologically beneficial as predators of pest insects, while a few provide direct economic benefit. Two species in particular are economically important and were domesticated many centuries ago:

silkworms for

silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

and

honey bee

A honey bee (also spelled honeybee) is a eusocial flying insect within the genus ''Apis'' of the bee clade, all native to mainland Afro-Eurasia. After bees spread naturally throughout Africa and Eurasia, humans became responsible for the ...

s for

honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several species of bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of pl ...

. Insects are consumed as food in 80% of the world's nations, by people in roughly 3,000 ethnic groups. Human activities are having serious effects on

insect biodiversity.

Etymology

The word ''insect'' comes from the

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

word from + , "cut up", as insects appear to be cut into three parts. The Latin word was introduced by

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

who

calque

In linguistics, a calque () or loan translation is a word or phrase borrowed from another language by literal word-for-word or root-for-root translation. When used as a verb, "to calque" means to borrow a word or phrase from another language ...

d the

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

word ''éntomon'' "insect" (as in

entomology

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In ...

) from ''éntomos'' "cut in pieces";

this was

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's term for this

class of life in his biology, also in reference to their notched bodies. The English word ''insect'' first appears in 1601 in

Philemon Holland's translation of Pliny.

Insects and other bugs

Distinguishing features

In common speech, insects and other terrestrial

arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s are often called bugs. Entomologists to some extent reserve the name "bugs" for a narrow category of "

true bugs

Hemiptera (; ) is an order (biology), order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising more than 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, Cimex, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They ...

", insects of the order

Hemiptera

Hemiptera (; ) is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising more than 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from ...

, such as

cicada

The cicadas () are a superfamily, the Cicadoidea, of insects in the order Hemiptera (true bugs). They are in the suborder Auchenorrhyncha, along with smaller jumping bugs such as leafhoppers and froghoppers. The superfamily is divided into two ...

s and

shield bugs.

Other terrestrial arthropods, such as

centipede

Centipedes (from Neo-Latin , "hundred", and Latin , "foot") are predatory arthropods belonging to the class Chilopoda (Ancient Greek , ''kheilos'', "lip", and Neo-Latin suffix , "foot", describing the forcipules) of the subphylum Myriapoda, ...

s,

millipede

Millipedes (originating from the Latin , "thousand", and , "foot") are a group of arthropods that are characterised by having two pairs of jointed legs on most body segments; they are known scientifically as the class Diplopoda, the name derive ...

s,

woodlice

Woodlice are terrestrial isopods in the suborder Oniscidea. Their name is derived from being often found in old wood, and from louse, a parasitic insect, although woodlice are neither parasitic nor insects.

Woodlice evolved from marine isopods ...

,

spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

s,

mite

Mites are small arachnids (eight-legged arthropods) of two large orders, the Acariformes and the Parasitiformes, which were historically grouped together in the subclass Acari. However, most recent genetic analyses do not recover the two as eac ...

s and

scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the Order (biology), order Scorpiones. They have eight legs and are easily recognized by a pair of Chela (organ), grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward cur ...

s, are sometimes confused with insects, since they have a jointed exoskeleton.

Adult insects are the only arthropods that ever have wings, with up to two pairs on the thorax. Whether winged or not, adult insects can be distinguished by their three-part body plan, with head, thorax, and abdomen; they have three pairs of legs on the thorax.

File:Gemeine Heidelibelle (Sympetrum vulgatum) 4 (cropped).jpg, Insect: Six legs, three-part body

(head, thorax, abdomen),

up to two pairs of wings

File:Wolfsspinne Trochosa Rose-20190905-RM-081613 (cropped).jpg, Spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

: eight legs,

two-part body

File:Armadillidium_vulgare_001.jpg, Woodlouse

Woodlice are terrestrial isopods in the suborder Oniscidea. Their name is derived from being often found in old wood, and from louse, a parasitic insect, although woodlice are neither parasitic nor insects.

Woodlice evolved from marine isopods ...

: seven pairs of legs, seven body segments (plus head and tail)

File:Scolopendra viridicornis nigra (cropped).jpg, Centipede

Centipedes (from Neo-Latin , "hundred", and Latin , "foot") are predatory arthropods belonging to the class Chilopoda (Ancient Greek , ''kheilos'', "lip", and Neo-Latin suffix , "foot", describing the forcipules) of the subphylum Myriapoda, ...

: many legs,

one pair per segment

File:Milli's on the back (cropped).jpg, Millipede

Millipedes (originating from the Latin , "thousand", and , "foot") are a group of arthropods that are characterised by having two pairs of jointed legs on most body segments; they are known scientifically as the class Diplopoda, the name derive ...

: many legs,

two pairs per segment

Diversity

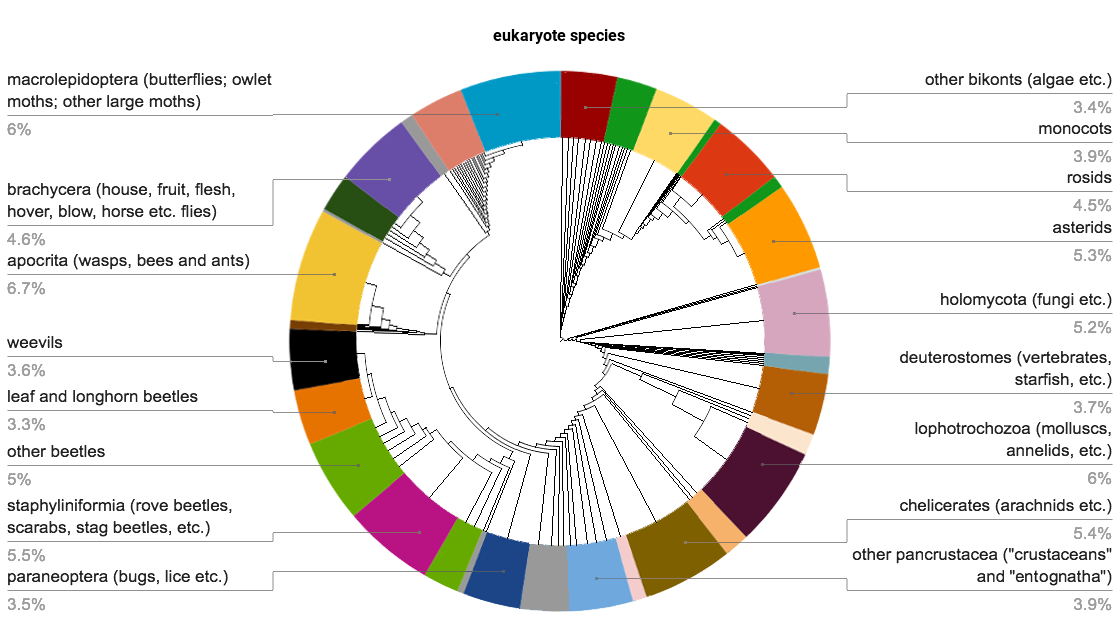

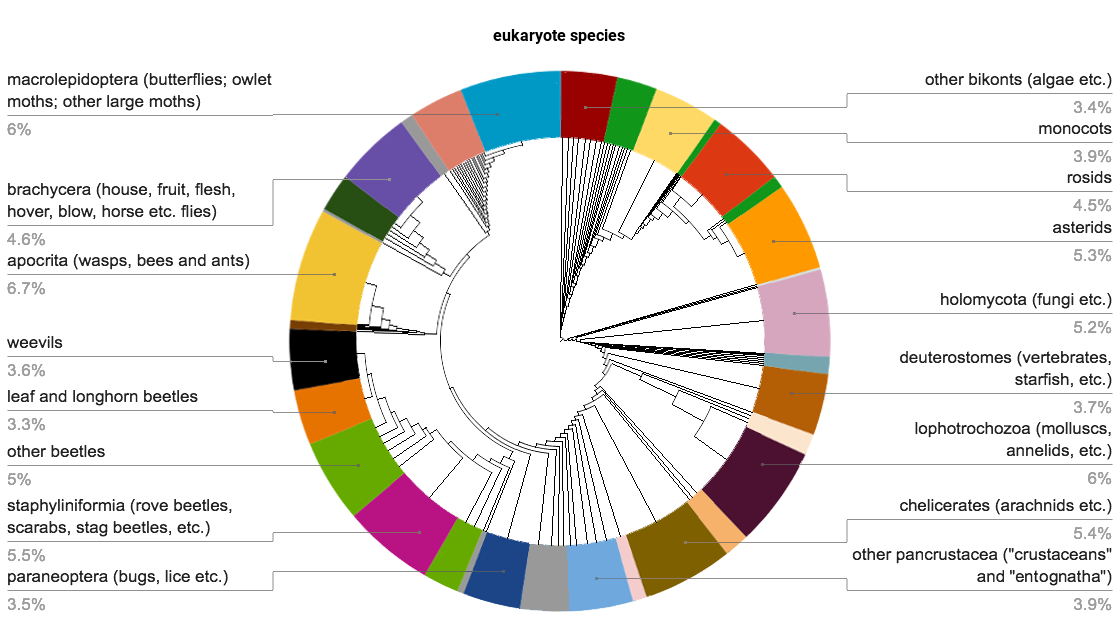

Estimates of the total number of insect species vary considerably, suggesting that there are perhaps some 5.5 million insect species in existence, of which about one million have been described and named.

These constitute around half of all

eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

species, including

animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

s,

plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s, and

fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

. The most diverse insect

orders are the Hemiptera (true bugs), Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), Diptera (true flies), Hymenoptera (wasps, ants, and bees), and Coleoptera (beetles), each with more than 100,000 described species.

(Hemiptera

Hemiptera (; ) is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising more than 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from ...

)

File:Peacock butterfly (Aglais io) 2.jpg, Butterflies and moths

(Lepidoptera

Lepidoptera ( ) or lepidopterans is an order (biology), order of winged insects which includes butterflies and moths. About 180,000 species of the Lepidoptera have been described, representing 10% of the total described species of living organ ...

)

File:Asilidae by kadavoor.jpg, Flies

( Diptera)

File:Specimen of Podalonia tydei (Le Guillou, 1841) (cropped).jpg, Wasps

( Hymenoptera)

File:7-Spotted-Ladybug-Coccinella-septempunctata-sq1.jpg, Beetles

( Coleoptera)

Distribution and habitats

File:Boreus hyemalis 5930585 (cropped).jpg, The snow scorpionfly '' Boreus hyemalis'' on snow

File:Dytiscus marginalis larva.jpg, The great diving beetle '' Dytiscus marginalis'' larva in a pond

File:Green Orchid Bee (Euglossa dilemma) (7406599274).jpg, The green orchid bee '' Euglossa dilemma'' of Central America

File:SGR laying (cropped).jpg, The desert locust '' Schistocerca gregaria'' laying eggs in sand

File:Halobates sp. (Heteroptera Gerridae), 20 August 2011, Castle Beach, Kailua (Oahu), Hawaii03 (cropped).jpg, Sea skater '' Halobates'' on a Hawaii beach

Insects are distributed over every continent and almost every terrestrial habitat. There are many more species in the

tropics

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the equator, where the sun may shine directly overhead. This contrasts with the temperate or polar regions of Earth, where the Sun can never be directly overhead. This is because of Earth's ax ...

, especially in

rainforests, than in temperate zones. The world's regions have received widely differing amounts of attention from entomologists. The British Isles have been thoroughly surveyed, so that Gullan and Cranston 2014 state that the total of around 22,500 species is probably within 5% of the actual number there; they comment that Canada's list of 30,000 described species is surely over half of the actual total. They add that the 3,000 species of the American Arctic must be broadly accurate. In contrast, a large majority of the insect species of the tropics and the

southern hemisphere are probably undescribed. Some 30–40,000 species

inhabit freshwater; very few insects, perhaps a hundred species, are marine.

Insects such as

snow scorpionflies flourish in cold habitats including the

Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

and at high altitude. Insects such as

desert locust

The desert locust (''Schistocerca gregaria'') is a species of locust, a periodically swarming, short-horned grasshopper in the family Acrididae. They are found primarily in the deserts and dry areas of northern and eastern Africa, Arabia, and ...

s, ants, beetles, and termites are adapted to some of the hottest and driest environments on earth, such as the

Sonoran Desert.

Phylogeny and evolution

External phylogeny

Insects form a

clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

, a natural group with a common ancestor, among the

arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s.

A

phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical dat ...

analysis by Kjer et al. (2016) places the insects among the

Hexapoda, six-legged animals with segmented bodies; their closest relatives are the

Diplura (bristletails).

Internal phylogeny

The internal phylogeny is based on the works of Wipfler et al. 2019 for the

Polyneoptera,

Johnson et al. 2018 for the

Paraneoptera,

and Kjer et al. 2016 for the

Holometabola

Holometabola (from Ancient Greek "complete" + "change"), also known as Endopterygota (from "inner" + "wing" + Neo-Latin "-having"), is a supra-order (biology), ordinal clade of insects within the infraclass Neoptera that go through distincti ...

.

The numbers of described

extant

Extant or Least-concern species, least concern is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Exta ...

species (boldface for groups with over 100,000 species) are from Stork 2018.

Taxonomy

Early

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

was the first to describe the insects as a distinct group. He placed them as the second-lowest level of animals on his ''

scala naturae'', above the

spontaneously generating sponges and worms, but below the hard-shelled marine snails. His classification remained in use for many centuries.

In 1758, in his ''

Systema Naturae

' (originally in Latin written ' with the Orthographic ligature, ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Sweden, Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the syste ...

'',

Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

divided the animal kingdom into six classes including

Insecta

Insects (from Latin ') are hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs of jointed leg ...

. He created seven orders of insect according to the structure of their wings. These were the wingless Aptera, the two-winged Diptera, and five four-winged orders: the Coleoptera with fully-hardened forewings; the Hemiptera with partly-hardened forewings; the Lepidoptera with scaly wings; the Neuroptera with membranous wings but no

sting; and the Hymenoptera, with membranous wings and a sting.

Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biologi ...

, in his 1809 ''

Philosophie Zoologique'', treated the insects as one of nine invertebrate

phyla

Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phy ...

.

In his 1817 ''

Le Règne Animal'',

Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

grouped all animals into four ''embranchements'' ("branches" with different body plans), one of which was the articulated animals, containing arthropods and annelids. This arrangement was followed by the embryologist

Karl Ernst von Baer in 1828, the zoologist

Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he recei ...

in 1857, and the comparative anatomist

Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

in 1860.

[ In 1874, ]Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, natural history, naturalist, eugenics, eugenicist, Philosophy, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biology, marine biologist and artist ...

divided the animal kingdom into two subkingdoms, one of which was Metazoa for the multicellular animals. It had five phyla, including the articulates.

Modern

Traditional morphology-based systematics

Systematics is the study of the diversification of living forms, both past and present, and the relationships among living things through time. Relationships are visualized as evolutionary trees (synonyms: phylogenetic trees, phylogenies). Phy ...

have usually given the Hexapoda the rank of superclass, and identified four groups within it: insects (Ectognatha), Collembola, Protura, and Diplura, the latter three being grouped together as the Entognatha on the basis of internalized mouth parts.monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

, as Archaeognatha are sister to all other insects, based on the arrangement of their mandibles, while the Pterygota, the winged insects, emerged from within the Dicondylia, alongside the Zygentoma.Holometabola

Holometabola (from Ancient Greek "complete" + "change"), also known as Endopterygota (from "inner" + "wing" + Neo-Latin "-having"), is a supra-order (biology), ordinal clade of insects within the infraclass Neoptera that go through distincti ...

). The molecular finding that the traditional louse orders Mallophaga and Anoplura are within Psocoptera has led to the new taxon Psocodea. Phasmatodea and Embiidina have been suggested to form the Eukinolabia. Mantodea, Blattodea, and Isoptera form a monophyletic group, Dictyoptera. Fleas are now thought to be closely related to boreid mecopterans.

Evolutionary history

The oldest fossil that may be a primitive wingless insect is '' Leverhulmia'' from the Early Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

Windyfield chert. The oldest known flying insects are from the mid-Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

, around 328–324 million years ago. The group subsequently underwent a rapid explosive diversification. Claims that they originated substantially earlier, during the Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 23.5 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the third and shortest period of t ...

or Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

(some 400 million years ago) based on molecular clock estimates, are unlikely to be correct, given the fossil record.

Four large-scale radiations of insects have occurred: beetle

Beetles are insects that form the Taxonomic rank, order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Holometabola. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 40 ...

s (from about 300 million years ago), flies

Flies are insects of the Order (biology), order Diptera, the name being derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwin ...

(from about 250 million years ago), moth

Moths are a group of insects that includes all members of the order Lepidoptera that are not Butterfly, butterflies. They were previously classified as suborder Heterocera, but the group is Paraphyly, paraphyletic with respect to butterflies (s ...

s and wasp

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder ...

s (both from about 150 million years ago).Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

period, but achieved their wide diversity more recently in the Cenozoic era, which began 66 million years ago. Some highly successful insect groups evolved in conjunction with flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (). The term angiosperm is derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek words (; 'container, vessel') and (; 'seed'), meaning that the seeds are enclosed with ...

s, a powerful illustration of coevolution. Insects were among the earliest terrestrial herbivore

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically evolved to feed on plants, especially upon vascular tissues such as foliage, fruits or seeds, as the main component of its diet. These more broadly also encompass animals that eat ...

s and acted as major selection agents on plants.Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

, around 300 million years ago.

File:Moravocoleus permianus.jpg, Beetle

Beetles are insects that form the Taxonomic rank, order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Holometabola. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 40 ...

'' Moravocoleus permianus'', fossil and reconstruction, from the Early Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

File:Fossil Wasp ( Iberomaimetsha ).jpg, Hymenoptera such as this '' Iberomaimetsha'' from the Early Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

, around 100 million years ago.

Morphology and physiology

External

Three-part body

Insects have a segmented body supported by an exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

, the hard outer covering made mostly of chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

. The body is organized into three interconnected units: the head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

, thorax

The thorax (: thoraces or thoraxes) or chest is a part of the anatomy of mammals and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen.

In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main di ...

and abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the gut, belly, tummy, midriff, tucky, or stomach) is the front part of the torso between the thorax (chest) and pelvis in humans and in other vertebrates. The area occupied by the abdomen is called the abdominal ...

. The head supports a pair of sensory antennae, a pair of compound eye

A compound eye is a Eye, visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidium, ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens (anatomy), lens, and p ...

s, zero to three simple eyes (or ocelli) and three sets of variously modified appendages that form the mouthparts. The thorax carries the three pairs of legs and up to two pairs of wings. The abdomen contains most of the digestive, respiratory, excretory and reproductive structures.

Segmentation

The head is enclosed in a hard, heavily sclerotized, unsegmented head capsule, which contains most of the sensing organs, including the antennae, compound eyes, ocelli, and mouthparts. The thorax is composed of three sections named (from front to back) the prothorax, mesothorax and metathorax. The prothorax carries the first pair of legs. The mesothorax carries the second pair of legs and the front wings. The metathorax carries the third pair of legs and the hind wings. The abdomen is the largest part of the insect, typically with 11–12 segments, and is less strongly sclerotized than the head or thorax. Each segment of the abdomen has sclerotized upper and lower plates (the tergum and sternum), connected to adjacent sclerotized parts by membranes. Each segment carries a pair of spiracles.

Exoskeleton

The outer skeleton, the cuticle, is made up of two layers: the epicuticle, a thin and waxy water-resistant outer layer without chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

, and a lower layer, the thick chitinous procuticle. The procuticle has two layers: an outer exocuticle and an inner endocuticle. The tough and flexible endocuticle is built from numerous layers of fibrous chitin and proteins, criss-crossing each other in a sandwich pattern, while the exocuticle is rigid and sclerotized. As an adaptation to life on land, insects have an enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

that uses atmospheric oxygen to harden their cuticle, unlike crustaceans which use heavy calcium compounds for the same purpose. This makes the insect exoskeleton a lightweight material.

Internal systems

Nervous

The nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the complex system, highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its behavior, actions and sense, sensory information by transmitting action potential, signals to and from different parts of its body. Th ...

of an insect consists of a brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

and a ventral nerve cord

The ventral nerve cord is a major structure of the invertebrate central nervous system. It is the functional equivalent of the vertebrate spinal cord. The ventral nerve cord coordinates neural signaling from the brain to the body and vice ve ...

. The head capsule is made up of six fused segments, each with either a pair of ganglia

A ganglion (: ganglia) is a group of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. In the somatic nervous system, this includes dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia among a few others. In the autonomic nervous system, there a ...

, or a cluster of nerve cells outside of the brain. The first three pairs of ganglia are fused into the brain, while the three following pairs are fused into a structure of three pairs of ganglia under the insect's esophagus

The esophagus (American English), oesophagus (British English), or œsophagus (Œ, archaic spelling) (American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, see spelling difference) all ; : ((o)e)(œ)sophagi or ((o)e)(œ)sophaguses), c ...

, called the subesophageal ganglion. The thoracic segments have one ganglion on each side, connected into a pair per segment. This arrangement is also seen in the first eight segments of the abdomen. Many insects have fewer ganglia than this.

Digestive

An insect uses its digestive system to extract nutrients and other substances from the food it consumes.flies

Flies are insects of the Order (biology), order Diptera, the name being derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwin ...

, expel digestive enzymes onto their food to break it down, but most insects digest their food in the gut. The foregut

The foregut in humans is the anterior part of the alimentary canal, from the distal esophagus to the first half of the duodenum, at the entrance of the bile duct. Beyond the stomach, the foregut is attached to the abdominal walls by mesentery. ...

is lined with cuticule as protection from tough food. It includes the mouth

A mouth also referred to as the oral is the body orifice through which many animals ingest food and animal communication#Auditory, vocalize. The body cavity immediately behind the mouth opening, known as the oral cavity (or in Latin), is also t ...

, pharynx, and crop

A crop is a plant that can be grown and harvested extensively for profit or subsistence. In other words, a crop is a plant or plant product that is grown for a specific purpose such as food, Fiber, fibre, or fuel.

When plants of the same spe ...

which stores food. Digestion starts in the mouth with enzymes in the saliva. Strong muscles in the pharynx pump fluid into the mouth, lubricating the food, and enabling certain insects to feed on blood or from the xylem

Xylem is one of the two types of transport tissue (biology), tissue in vascular plants, the other being phloem; both of these are part of the vascular bundle. The basic function of the xylem is to transport water upward from the roots to parts o ...

and phloem transport vessels of plants. Once food leaves the crop, it passes to the midgut

The midgut is the portion of the human embryo from which almost all of the small intestine and approximately half of the large intestine develop. After it bends around the superior mesenteric artery, it is called the "midgut loop". It comprises ...

, where the majority of digestion takes place. Microscopic projections, microvilli, increase the surface area of the wall to absorb nutrients. In the hindgut, undigested food particles are joined by uric acid

Uric acid is a heterocyclic compound of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen with the Chemical formula, formula C5H4N4O3. It forms ions and salts known as urates and acid urates, such as ammonium acid urate. Uric acid is a product of the meta ...

to form fecal pellets; most of the water is absorbed, leaving a dry pellet to be eliminated. Insects may have one to hundreds of Malpighian tubules

The Malpighian tubule system is a type of excretory and osmoregulation, osmoregulatory system found in some insects, myriapods, arachnids and tardigrades. It has also been described in some crustacean species, and is likely the same organ as the ...

. These remove nitrogenous wastes from the hemolymph of the insect and regulate osmotic balance. Wastes and solutes are emptied directly into the alimentary canal, at the junction between the midgut and hindgut.

Reproductive

The reproductive system of female insects consist of a pair of ovaries

The ovary () is a gonad in the female reproductive system that produces ova; when released, an ovum travels through the fallopian tube/oviduct into the uterus. There is an ovary on the left and the right side of the body. The ovaries are endocr ...

, accessory glands, one or more spermatheca

The spermatheca (pronounced : spermathecae ), also called ''receptaculum seminis'' (: ''receptacula seminis''), is an organ of the female reproductive tract in insects, e.g. ants, bees, some molluscs, Oligochaeta worms and certain other in ...

e to store sperm, and ducts connecting these parts. The ovaries are made up of a variable number of egg tubes, ovarioles. Female insects make eggs, receive and store sperm, manipulate sperm from different males, and lay eggs. Accessory glands produce substances to maintain sperm and to protect the eggs. They can produce glue and protective substances for coating eggs, or tough coverings for a batch of eggs called oothecae.

For males, the reproductive system consists of one or two testes, suspended in the body cavity by tracheae. The testes contain sperm tubes or follicles in a membranous sac. These connect to a duct that leads to the outside. The terminal portion of the duct may be sclerotized to form the intromittent organ, the aedeagus.

Respiratory

Insect respiration is accomplished without

Insect respiration is accomplished without lung

The lungs are the primary Organ (biology), organs of the respiratory system in many animals, including humans. In mammals and most other tetrapods, two lungs are located near the Vertebral column, backbone on either side of the heart. Their ...

s. Instead, insects have a system of internal tubes and sacs through which gases either diffuse or are actively pumped, delivering oxygen directly to tissues that need it via their tracheae and tracheoles. In most insects, air is taken in through paired spiracles, openings on the sides of the abdomen and thorax. The respiratory system limits the size of insects. As insects get larger, gas exchange via spiracles becomes less efficient, and thus the heaviest insect currently weighs less than 100 g. However, with increased atmospheric oxygen levels, as were present in the late Paleozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma a ...

, larger insects were possible, such as dragonflies with wingspans of more than . Gas exchange patterns in insects range from continuous and diffusive ventilation, to discontinuous.

Circulatory

Because oxygen is delivered directly to tissues via tracheoles, the circulatory system is not used to carry oxygen, and is therefore greatly reduced. The insect circulatory system is open; it has no veins or arteries, and instead consists of little more than a single, perforated dorsal tube that pulses peristaltically. This dorsal blood vessel is divided into two sections: the heart and aorta. The dorsal blood vessel circulates the hemolymph, arthropods' fluid analog of blood, from the rear of the body cavity forward. Hemolymph is composed of plasma in which hemocytes are suspended. Nutrients, hormones, wastes, and other substances are transported throughout the insect body in the hemolymph. Hemocytes include many types of cells that are important for immune responses, wound healing, and other functions. Hemolymph pressure may be increased by muscle contractions or by swallowing air into the digestive system to aid in molting.

Sensory

Many insects possess numerous specialized sensory organs able to detect stimuli including limb position (

Many insects possess numerous specialized sensory organs able to detect stimuli including limb position (proprioception

Proprioception ( ) is the sense of self-movement, force, and body position.

Proprioception is mediated by proprioceptors, a type of sensory receptor, located within muscles, tendons, and joints. Most animals possess multiple subtypes of propri ...

) by campaniform sensilla, light, water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

, chemicals (senses of taste

The gustatory system or sense of taste is the sensory system that is partially responsible for the perception of taste. Taste is the perception stimulated when a substance in the mouth biochemistry, reacts chemically with taste receptor cells l ...

and smell), sound, and heat. Some insects such as bees can perceive ultraviolet

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of ...

wavelengths, or detect polarized light, while the antennae of male moths can detect the pheromone

A pheromone () is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavio ...

s of female moths over distances of over a kilometer. There is a trade-off between visual acuity and chemical or tactile acuity, such that most insects with well-developed eyes have reduced or simple antennae, and vice versa. Insects perceive sound by different mechanisms, such as thin vibrating membranes ( tympana). Insects were the earliest organisms to produce and sense sounds. Hearing has evolved independently at least 19 times in different insect groups.compound eye

A compound eye is a Eye, visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidium, ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens (anatomy), lens, and p ...

s. Many species can detect light in the infrared

Infrared (IR; sometimes called infrared light) is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than that of visible light but shorter than microwaves. The infrared spectral band begins with the waves that are just longer than those ...

, ultraviolet

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of ...

and visible light wavelengths, with color vision. Phylogenetic analysis suggests that UV-green-blue trichromacy existed from at least the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

period, some 400 million years ago.

Reproduction and development

Life-cycles

The majority of insects hatch from eggs. The fertilization and development takes place inside the egg, enclosed by a shell ( chorion) that consists of maternal tissue. In contrast to eggs of other arthropods, most insect eggs are drought resistant. This is because inside the chorion two additional membranes develop from embryonic tissue, the amnion and the serosa. This serosa secretes a cuticle rich in

The majority of insects hatch from eggs. The fertilization and development takes place inside the egg, enclosed by a shell ( chorion) that consists of maternal tissue. In contrast to eggs of other arthropods, most insect eggs are drought resistant. This is because inside the chorion two additional membranes develop from embryonic tissue, the amnion and the serosa. This serosa secretes a cuticle rich in chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

that protects the embryo against desiccation. Some species of insects, like aphids and tsetse flies, are ovoviviparous: their eggs develop entirely inside the female, and then hatch immediately upon being laid.["insect physiology" ''McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology'', Ch. 9, p. 233, 2007] Some other species, such as in the cockroach genus '' Diploptera'', are viviparous, gestating inside the mother and born alive. Some insects, like parasitoid wasp

Parasitoid wasps are a large group of hymenopteran Superfamily (zoology), superfamilies, with all but the wood wasps (Orussoidea) being in the wasp-waisted Apocrita. As parasitoids, they lay their eggs on or in the bodies of other arthropods, ...

s, are polyembryonic, meaning that a single fertilized egg divides into many separate embryos. Insects may be univoltine, bivoltine or multivoltine, having one, two or many broods in a year. Other developmental and reproductive variations include haplodiploidy, polymorphism, paedomorphosis or

Other developmental and reproductive variations include haplodiploidy, polymorphism, paedomorphosis or peramorphosis

In evolutionary developmental biology, heterochrony is any genetically controlled difference in the timing, rate, or duration of a Developmental biology, developmental process in an organism compared to its ancestors or other organisms. This lea ...

, sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

, parthenogenesis, and more rarely hermaphroditism. In haplodiploidy, which is a type of sex-determination system

A sex-determination system is a biological system that determines the development of sexual characteristics in an organism. Most organisms that create their offspring using sexual reproduction have two common sexes, males and females, and in ...

, the offspring's sex is determined by the number of sets of chromosome

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most import ...

s an individual receives. This system is typical in bees and wasps.

Some insects are parthenogenetic

Parthenogenesis (; from the Greek + ) is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which the embryo develops directly from an egg without need for fertilization. In animals, parthenogenesis means the development of an embryo from an unfertiliz ...

, meaning that the female can reproduce and give birth without having the eggs fertilized by a male

Male (Planet symbols, symbol: ♂) is the sex of an organism that produces the gamete (sex cell) known as sperm, which fuses with the larger female gamete, or Egg cell, ovum, in the process of fertilisation. A male organism cannot sexual repro ...

. Many aphids undergo a cyclical form of parthenogenesis in which they alternate between one or many generations of asexual and sexual reproduction. In summer, aphids are generally female and parthenogenetic; in the autumn, males may be produced for sexual reproduction. Other insects produced by parthenogenesis are bees, wasps and ants; in their haplodiploid system, diploid females spawn many females and a few haploid males.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is a biological process by which an animal physically develops including birth transformation or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and different ...

in insects is the process of development that converts young to adults. There are two forms of metamorphosis: incomplete and complete.

Incomplete

Hemimetabolous insects, those with incomplete metamorphosis, change gradually after hatching from the egg by undergoing a series of molts through stages called instar

An instar (, from the Latin '' īnstar'' 'form, likeness') is a developmental stage of arthropods, such as insects, which occurs between each moult (''ecdysis'') until sexual maturity is reached. Arthropods must shed the exoskeleton in order to ...

s, until the final, adult, stage is reached. An insect molts when it outgrows its exoskeleton, which does not stretch and would otherwise restrict the insect's growth. The molting process begins as the insect's epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and Subcutaneous tissue, hypodermis. The epidermal layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the ...

secretes a new epicuticle inside the old one. After this new epicuticle is secreted, the epidermis releases a mixture of enzymes that digests the endocuticle and thus detaches the old cuticle. When this stage is complete, the insect makes its body swell by taking in a large quantity of water or air; this makes the old cuticle split along predefined weaknesses where it was thinnest.

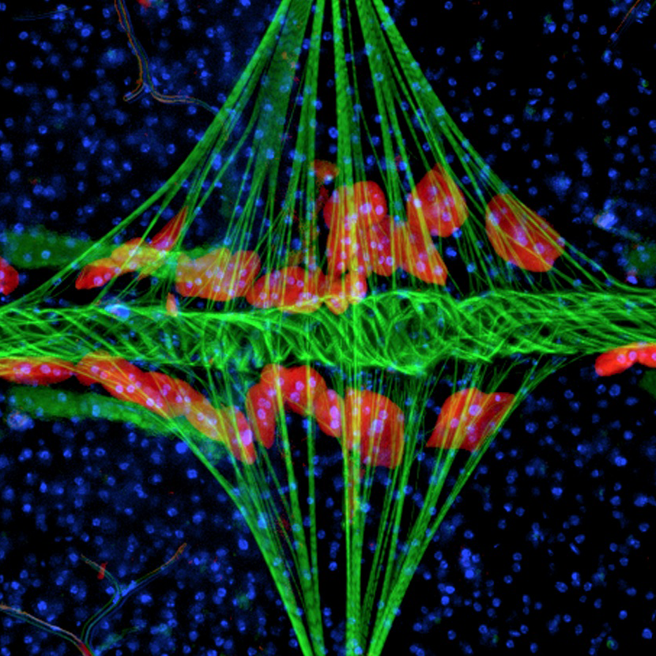

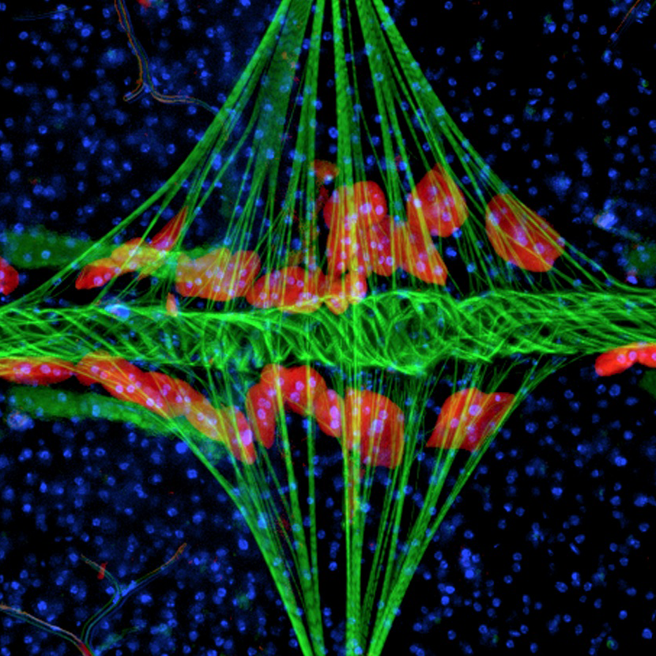

Complete

Holometabolism, or complete metamorphosis, is where the insect changes in four stages, an egg or embryo, a

Holometabolism, or complete metamorphosis, is where the insect changes in four stages, an egg or embryo, a larva

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase ...

, a pupa and the adult or imago. In these species, an egg hatches to produce a larva, which is generally worm-like in form. This can be eruciform (caterpillar-like), scarabaeiform (grub-like), campodeiform (elongated, flattened and active), elateriform (wireworm-like) or vermiform (maggot-like). The larva grows and eventually becomes a pupa, a stage marked by reduced movement. There are three types of pupae: obtect, exarate or coarctate. Obtect pupae are compact, with the legs and other appendages enclosed. Exarate pupae have their legs and other appendages free and extended. Coarctate pupae develop inside the larval skin. Insects undergo considerable change in form during the pupal stage, and emerge as adults. Butterflies are well-known for undergoing complete metamorphosis; most insects use this life cycle. Some insects have evolved this system to hypermetamorphosis. Complete metamorphosis is a trait of the most diverse insect group, the Endopterygota.

Communication

Insects that produce sound can generally hear it. Most insects can hear only a narrow range of frequencies related to the frequency of the sounds they can produce. Mosquitoes can hear up to 2 kilohertz

The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), often described as being equivalent to one event (or cycle) per second. The hertz is an SI derived unit whose formal expression in terms of SI base ...

. Certain predatory and parasitic insects can detect the characteristic sounds made by their prey or hosts, respectively. Likewise, some nocturnal moths can perceive the ultrasonic emissions of bats, which helps them avoid predation.

Light production

A few insects, such as Mycetophilidae (Diptera) and the beetle families Lampyridae, Phengodidae, Elateridae and Staphylinidae are bioluminescent. The most familiar group are the fireflies, beetles of the family Lampyridae. Some species are able to control this light generation to produce flashes. The function varies with some species using them to attract mates, while others use them to lure prey. Cave dwelling larvae of ''Arachnocampa

''Arachnocampa'' is a genus of nine fungus gnat species which have a bioluminescent larval stage, akin to the larval stage of glowworm beetles. The species of ''Arachnocampa'' are endemic to Australia and New Zealand, dwelling in caves and grotto ...

'' (Mycetophilidae, fungus gnats) glow to lure small flying insects into sticky strands of silk. Some fireflies of the genus '' Photuris'' mimic

In evolutionary biology, mimicry is an evolved resemblance between an organism and another object, often an organism of another species. Mimicry may evolve between different species, or between individuals of the same species. In the simples ...

the flashing of female '' Photinus'' species to attract males of that species, which are then captured and devoured. The colors of emitted light vary from dull blue (''Orfelia fultoni'', Mycetophilidae) to the familiar greens and the rare reds (''Phrixothrix tiemanni'', Phengodidae).

Sound production

Insects make sounds mostly by mechanical action of appendages. In grasshoppers and crickets, this is achieved by stridulation. Cicada

The cicadas () are a superfamily, the Cicadoidea, of insects in the order Hemiptera (true bugs). They are in the suborder Auchenorrhyncha, along with smaller jumping bugs such as leafhoppers and froghoppers. The superfamily is divided into two ...

s make the loudest sounds among the insects by producing and amplifying sounds with special modifications to their body to form tymbals and associated musculature. The African cicada

The cicadas () are a superfamily, the Cicadoidea, of insects in the order Hemiptera (true bugs). They are in the suborder Auchenorrhyncha, along with smaller jumping bugs such as leafhoppers and froghoppers. The superfamily is divided into two ...

'' Brevisana brevis'' has been measured at 106.7 decibel

The decibel (symbol: dB) is a relative unit of measurement equal to one tenth of a bel (B). It expresses the ratio of two values of a Power, root-power, and field quantities, power or root-power quantity on a logarithmic scale. Two signals whos ...

s at a distance of .ultrasound

Ultrasound is sound with frequency, frequencies greater than 20 Hertz, kilohertz. This frequency is the approximate upper audible hearing range, limit of human hearing in healthy young adults. The physical principles of acoustic waves apply ...

and take evasive action when they sense that they have been detected by bats. Some moths produce ultrasonic clicks that warn predatory bats of their unpalatability (acoustic aposematism

Aposematism is the Advertising in biology, advertising by an animal, whether terrestrial or marine, to potential predation, predators that it is not worth attacking or eating. This unprofitability may consist of any defenses which make the pr ...

), while some palatable moths have evolved to mimic these calls (acoustic Batesian mimicry). The claim that some moths can jam bat sonar has been revisited. Ultrasonic recording and high-speed infrared videography of bat-moth interactions suggest the palatable tiger moth really does defend against attacking big brown bats using ultrasonic clicks that jam bat sonar.

Very low sounds are produced in various species of Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera

Lepidoptera ( ) or lepidopterans is an order (biology), order of winged insects which includes butterflies and moths. About 180,000 species of the Lepidoptera have been described, representing 10% of the total described species of living organ ...

, Mantodea and Neuroptera. These low sounds are produced by the insect's movement, amplified by stridulatory structures on the insect's muscles and joints; these sounds can be used to warn or communicate with other insects. Most sound-making insects also have tympanal organs that can perceive airborne sounds. Some hemiptera

Hemiptera (; ) is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising more than 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from ...

ns, such as the water boatmen, communicate via underwater sounds.

Communication using surface-borne vibrational signals is more widespread among insects because of size constraints in producing air-borne sounds. Insects cannot effectively produce low-frequency sounds, and high-frequency sounds tend to disperse more in a dense environment (such as foliage

A leaf (: leaves) is a principal appendage of the stem of a vascular plant, usually borne laterally above ground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, stem, f ...

), so insects living in such environments communicate primarily using substrate-borne vibrations.

Some species use vibrations for communicating, such as to attract mates as in the songs of the shield bug '' Nezara viridula''. Vibrations can also be used to communicate between species; lycaenid caterpillars, which form a mutualistic association with ants communicate with ants in this way. The Madagascar hissing cockroach has the ability to press air through its spiracles to make a hissing noise as a sign of aggression; the death's-head hawkmoth makes a squeaking noise by forcing air out of their pharynx when agitated, which may also reduce aggressive worker honey bee behavior when the two are close.

Chemical communication

Many insects have evolved chemical means for communication. These semiochemicals are often derived from plant metabolites including those meant to attract, repel and provide other kinds of information.

Many insects have evolved chemical means for communication. These semiochemicals are often derived from plant metabolites including those meant to attract, repel and provide other kinds of information. Pheromone

A pheromone () is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavio ...

s are used for attracting mates of the opposite sex, for aggregating conspecific individuals of both sexes, for deterring other individuals from approaching, to mark a trail, and to trigger aggression in nearby individuals. Allomones benefit their producer by the effect they have upon the receiver. Kairomones benefit their receiver instead of their producer. Synomones benefit the producer and the receiver. While some chemicals are targeted at individuals of the same species, others are used for communication across species. The use of scents is especially well-developed in social insects. are nonstructural materials produced and secreted to the cuticle surface to fight desiccation

Desiccation is the state of extreme dryness, or the process of extreme drying. A desiccant is a hygroscopic (attracts and holds water) substance that induces or sustains such a state in its local vicinity in a moderately sealed container. The ...

and pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a Germ theory of d ...

s. They are important, too, as pheromones, especially in social insects.

Social behavior

Social insect

Eusociality (Ancient Greek, Greek 'good' and social) is the highest level of organization of sociality. It is defined by the following characteristics: cooperative Offspring, brood care (including care of offspring from other individuals), ove ...

s, such as termite

Termites are a group of detritivore, detritophagous Eusociality, eusocial cockroaches which consume a variety of Detritus, decaying plant material, generally in the form of wood, Plant litter, leaf litter, and Humus, soil humus. They are dist ...

s, ant

Ants are Eusociality, eusocial insects of the Family (biology), family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the Taxonomy (biology), order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from Vespoidea, vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cre ...

s and many bees and wasp

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder ...

s, are eusocial. They live together in such large well-organized colonies of genetically similar individuals that they are sometimes considered superorganisms. In particular, reproduction is largely limited to a queen caste; other females are workers, prevented from reproducing by worker policing. Honey bee

A honey bee (also spelled honeybee) is a eusocial flying insect within the genus ''Apis'' of the bee clade, all native to mainland Afro-Eurasia. After bees spread naturally throughout Africa and Eurasia, humans became responsible for the ...

s have evolved a system of abstract symbolic communication where a behavior is used to represent and convey specific information about the environment. In this communication system, called dance language, the angle at which a bee dances represents a direction relative to the sun, and the length of the dance represents the distance to be flown. Bumblebee

A bumblebee (or bumble bee, bumble-bee, or humble-bee) is any of over 250 species in the genus ''Bombus'', part of Apidae, one of the bee families. This genus is the only Extant taxon, extant group in the tribe Bombini, though a few extinct r ...

s too have some social communication behaviors. '' Bombus terrestris'', for example, more rapidly learns about visiting unfamiliar, yet rewarding flowers, when they can see a conspecific foraging on the same species.

Only insects that live in nests or colonies possess fine-scale spatial orientation. Some can navigate unerringly to a single hole a few millimeters in diameter among thousands of similar holes, after a trip of several kilometers. In philopatry

Philopatry is the tendency of an organism to stay in or habitually return to a particular area. The causes of philopatry are numerous, but natal philopatry, where animals return to their birthplace to breed, may be the most common. The term derives ...

, insects that hibernate are able to recall a specific location up to a year after last viewing the area of interest. A few insects seasonally migrate large distances between different geographic regions, as in the continent-wide monarch butterfly migration.

Care of young

Eusocial insects build nests, guard eggs, and provide food for offspring full-time. Most insects, however, lead short lives as adults, and rarely interact with one another except to mate or compete for mates. A small number provide parental care, where they at least guard their eggs, and sometimes guard their offspring until adulthood, possibly even feeding them. Many wasps and bees construct a nest or burrow, store provisions in it, and lay an egg upon those provisions, providing no further care.

Locomotion

Flight

Insects are the only group of invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s to have developed flight. The ancient groups of insects in the Palaeoptera, the dragonflies, damselflies and mayflies, operate their wings directly by paired muscles attached to points on each wing base that raise and lower them. This can only be done at a relatively slow rate. All other insects, the Neoptera, have indirect flight, in which the flight muscles cause rapid oscillation of the thorax: there can be more wingbeats than nerve impulses commanding the muscles. One pair of flight muscles is aligned vertically, contracting to pull the top of the thorax down, and the wings up. The other pair runs longitudinally, contracting to force the top of the thorax up and the wings down.insect wing

Insect wings are adult outgrowths of the insect exoskeleton that enable insect flight, insects to fly. They are found on the second and third Thorax (insect anatomy), thoracic segments (the mesothorax and metathorax), and the two pairs are often ...

s has been a subject of debate; it has been suggested they came from modified gills, flaps on the spiracles, or an appendage, the epicoxa, at the base of the legs. More recently, entomologists have favored evolution of wings from lobes of the notum, of the pleuron, or more likely both.

In the Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

age, the dragonfly-like '' Meganeura'' had as much as a wide wingspan. The appearance of gigantic insects is consistent with high atmospheric oxygen at that time, as the respiratory system of insects constrains their size. The largest flying insects today are much smaller, with the largest wingspan belonging to the white witch moth ('' Thysania agrippina''), at approximately .bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s, small insects are swept along by the prevailing winds although many larger insects migrate. Aphid

Aphids are small sap-sucking insects in the Taxonomic rank, family Aphididae. Common names include greenfly and blackfly, although individuals within a species can vary widely in color. The group includes the fluffy white Eriosomatinae, woolly ...

s are transported long distances by low-level jet stream

Jet streams are fast flowing, narrow thermal wind, air currents in the Earth's Atmosphere of Earth, atmosphere.

The main jet streams are located near the altitude of the tropopause and are westerly winds, flowing west to east around the gl ...

s.

Walking

Many adult insects use six legs for walking, with an alternating tripod gait. This allows for rapid walking with a stable stance; it has been studied extensively in cockroach

Cockroaches (or roaches) are insects belonging to the Order (biology), order Blattodea (Blattaria). About 30 cockroach species out of 4,600 are associated with human habitats. Some species are well-known Pest (organism), pests.

Modern cockro ...

es and ant

Ants are Eusociality, eusocial insects of the Family (biology), family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the Taxonomy (biology), order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from Vespoidea, vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cre ...

s. For the first step, the middle right leg and the front and rear left legs are in contact with the ground and move the insect forward, while the front and rear right leg and the middle left leg are lifted and moved forward to a new position. When they touch the ground to form a new stable triangle, the other legs can be lifted and brought forward in turn.camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

d stick insects ( Phasmatodea). A small number of species such as Water striders can move on the surface of water; their claws are recessed in a special groove, preventing the claws from piercing the water's surface film.

Swimming

A large number of insects live either part or the whole of their lives underwater. In many of the more primitive orders of insect, the immature stages are aquatic. In some groups, such as water beetles, the adults too are aquatic.