The Hanno R. Ellenbogen Citizenship Award is given annually to honor individuals who have dedicated their lives to public service. It was established in 2000 by the

Prague Society for International Cooperation

The Prague Society for International Cooperation is a Prague-based non-governmental organization that originated in communist Central Europe, when political dissidents joined forces to oppose their respective regimes. Though several of its membe ...

and th

Global Panel Foundation It is named in honor of the Prague Society's President

Marc S. Ellenbogen's mother. The award comes with a 150,000 crown cash prize, which the award recipient passes on to a young person who is embarking on his/her career who has already contributed to the development of international relations. For instance when the

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

The Česká filharmonie (Czech Philharmonic) is a symphony orchestra based in Prague. The orchestra's principal concert venue is the Rudolfinum.

History

The name "Czech Philharmonic Orchestra" appeared for the first time in 1894, as the title ...

won the award in 2000 the cash prize was given to Lukas Vondracek, an aspiring musician at the time, who is now recognized worldwide.

Award recipients

First - Vladimir Ashkenazy and the Conducting Corp of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

Maestro

Vladimir Ashkenazy

Vladimir Davidovich Ashkenazy (russian: Влади́мир Дави́дович Ашкена́зи, ''Vladimir Davidovich Ashkenazi''; born 6 July 1937) is an internationally recognized solo pianist, chamber music performer, and conductor. He ...

(the Chief Conductor), and the Conducting Corp of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra (Include:

Vladimir Valek (the permanent conductor), Sir

Charles Mackerras

Mackerras in 2005

Sir Alan Charles MacLaurin Mackerras (; 1925 2010) was an Australian conductor. He was an authority on the operas of Janáček and Mozart, and the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan. He was long associated with the Engli ...

and

Ken-Ichiro Kobayashi (the principal guest conductors)). Askenazy devoted his first years as a musician to the piano. After winning first prizes in Brussels in 1956 and Moscow in 1962, he spent three decades touring the great musical centers of the world. From the 1970s, he became increasingly active as a conductor and held positions with the

Philharmonia Orchestra

The Philharmonia Orchestra is a British orchestra based in London. It was founded in 1945 by Walter Legge, a classical music record producer for EMI. Among the conductors who worked with the orchestra in its early years were Richard Strauss, ...

,

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London, that performs and produces primarily classic works.

The RPO was established by Thomas Beecham in 1946. In its early days, the orchestra secured profitable ...

,

Cleveland Orchestra

The Cleveland Orchestra, based in Cleveland, is one of the five American orchestras informally referred to as the " Big Five". Founded in 1918 by the pianist and impresario Adella Prentiss Hughes, the orchestra plays most of its concerts at Se ...

and

Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin

The Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin (DSO) is a German broadcast orchestra based in Berlin. The orchestra performs its concerts principally in the Philharmonie Berlin. The orchestra is administratively based at the ''Rundfunk Berlin-Branden ...

. From 1998 to 2003 Ashkenazy led the Conducting Corps of the

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

The Česká filharmonie (Czech Philharmonic) is a symphony orchestra based in Prague. The orchestra's principal concert venue is the Rudolfinum.

History

The name "Czech Philharmonic Orchestra" appeared for the first time in 1894, as the title ...

, with whom he undertook the major Prokofiev-Shostakovich series in 2003. Vladimir Valek has performed in many major cities around the world like Brussels, Cairo, Copenhagen, London, New York, Paris, Beijing, Tokyo, and Vienna. Sir Charles Mackerras (in memorium), born in Australia, had a passion for music his entire life and was honored with many awards throughout his life. Kobayashi was the first Asian Conductor to conduct at the

Prague Spring Music Festival in 2002.

Financial Part Donated to Lukáš Vondráček

Born in the Czech Republic in 1986 Lukáš Vondráček's musical ability was spotted at the age of two by his mother, herself a professional pianist. He gave his first concert at the age of 4 and now, by the age of 20, he visited 22 different countries giving in excess of 850 concerts. Vladimir Ashkenazy was the conductor when Lukáš made his debut with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra in May 2002 with concerts in Prague and Italy. Since then he has appeared frequently with the orchestra, including a major USA tour, and concerts in Cologne, Vienna, Lucerne, Bad Kissingen, and

Birmingham's Symphony Hall. In 2010, he won First Prize at the 10th

Hilton Head International Piano Competition The Hilton Head International Piano Competition is a piano competition held annually since 1996 at Hilton Head Island, South Carolina's First Presbyterian Church.

Selected list of jurors

* Joseph Banowetz

* José Feghali

* Peter Frankl

* K ...

in South Carolina, USA. Most recently, Lukas won First Prize, Grand Prize plus 4 special prizes at the 2012 UNISA Vodacom International Piano Competition in Pretoria, South Africa. In 2016

Lukas Vondráček won the

Queen Elisabeth Piano Competition in 2016.

Second - Madeleine Albright

Madeleine Albright

Madeleine Jana Korbel Albright (born Marie Jana Korbelová; May 15, 1937 – March 23, 2022) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 64th United States secretary of state from 1997 to 2001. A member of the Democrat ...

served as the

64th Secretary of State of the United States. She was the first woman Secretary of State and the highest-ranking woman in the history of the

US government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a feder ...

. As Secretary, Albright reinforced America's alliances, advocated democracy and human rights, and promoted American trade and business abroad. Serving as a member of the

President's Cabinet &

National Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a n ...

for 8 years, Albright was the US

Permanent Representative to the UN from 1993 to 1997. Albright is the first Michael & Virginia Mortara Endowed Professor in the Practice of Diplomacy at the

Georgetown School of Foreign Service

The Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service (SFS) is the school of international relations at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. It is considered to be one of the world's leading international affairs schools, granting degrees at both ...

. She is the Chairman of

The National Democratic Institute for International Affairs and founder of the

Albright Group

Dentons Global Advisors ASG, formerly Albright Stonebridge Group, is a global business strategy firm based in Washington, D.C., United States. It was created in 2009 through the merger of international consulting firms The Albright Group, found ...

, a global strategy firm delivering solutions and advice for businesses in a rapidly changing world.

Financial Part Donated to Petra Procházková

Madeleine Albright donated financial part to

Petra Procházková, a Czech journalist and humanitarian worker. She is best known as a war correspondent to the conflict areas of the

former Soviet Union

The post-Soviet states, also known as the former Soviet Union (FSU), the former Soviet Republics and in Russia as the near abroad (russian: links=no, ближнее зарубежье, blizhneye zarubezhye), are the 15 sovereign states that wer ...

. Procházková studied journalism at

Charles University

)

, image_name = Carolinum_Logo.svg

, image_size = 200px

, established =

, type = Public, Ancient

, budget = 8.9 billion CZK

, rector = Milena Králíčková

, faculty = 4,057

, administrative_staff = 4,026

, students = 51,438

, under ...

in Prague. In 1989 she started work at the newspaper

Lidové noviny

''Lidové noviny'' (''People's News'', or ''The People's Newspaper'', ) is a daily newspaper published in Prague, the Czech Republic. It is the oldest Czech daily still in print, and a newspaper of record.[Abkhazia

Abkhazia, ka, აფხაზეთი, tr, , xmf, აბჟუა, abzhua, or ( or ), officially the Republic of Abkhazia, is a partially recognised state in the South Caucasus, recognised by most countries as part of Georgia, which ...]

being the first. During the

Russian constitutional crisis of 1993

The 1993 Russian constitutional crisis, also known as the 1993 October Coup, Black October, the Shooting of the White House or Ukaz 1400, was a political stand-off and a constitutional crisis between the Russian president Boris Yeltsin and ...

she was the only journalist that stayed in the besieged Russian White House. In 1994, together with fellow journalist

Jaromír Štětina, Procházková founded the independent journalism agency Epicentrum dedicated to war reporting. In the following years she covered events in

Chechnya

Chechnya ( rus, Чечня́, Chechnyá, p=tɕɪtɕˈnʲa; ce, Нохчийчоь, Noxçiyçö), officially the Chechen Republic,; ce, Нохчийн Республика, Noxçiyn Respublika is a republic of Russia. It is situated in the ...

, Abkhazia,

Ossetia

Ossetia ( , ; os, Ирыстон or , or ; russian: Осетия, Osetiya; ka, ოსეთი, translit. ''Oseti'') is an ethnolinguistic region located on both sides of the Greater Caucasus Mountains, largely inhabited by the Ossetians. ...

,

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

,

Tajikistan

Tajikistan (, ; tg, Тоҷикистон, Tojikiston; russian: Таджикистан, Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan ( tg, Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Centr ...

,

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

,

Nagorny Karabakh,

Kurdistan

Kurdistan ( ku, کوردستان ,Kurdistan ; lit. "land of the Kurds") or Greater Kurdistan is a roughly defined geo-cultural territory in Western Asia wherein the Kurds form a prominent majority population and the Kurdish culture, languag ...

,

Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

and

East Timor

East Timor (), also known as Timor-Leste (), officially the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, is an island country in Southeast Asia. It comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, the exclave of Oecusse on the island's north-w ...

.

Third - Václav Havel

Václav Havel

Václav Havel (; 5 October 193618 December 2011) was a Czech statesman, author, poet, playwright, and former dissident. Havel served as the last president of Czechoslovakia from 1989 until the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1992 and then ...

grew up in a circle which maintained Czechoslovakia's independent culture in defiance of the

Communist regime

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Cominte ...

of the time. Excluded from higher education, he made his name in the 1960s with satirical plays which contributed to the intellectual atmosphere of the

Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First ...

. During the normalisation period which followed the

Soviet invasion he took menial jobs whilst his work was published in

samizdat

Samizdat (russian: самиздат, lit=self-publishing, links=no) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the document ...

. He was one of the first three spokesmen for

Charter 77

Charter 77 (''Charta 77'' in Czech and Slovak) was an informal civic initiative in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic from 1976 to 1992, named after the document Charter 77 from January 1977. Founding members and architects were Jiří Něm ...

, and a member of the

Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted. He was sentenced to four and a half years hard labour, resulting in a breakdown in his health. After his release in 1983 he continued to be a leading member of the opposition movement which culminated in the

Velvet Revolution of 1989. He was elected the first President of a free Czechoslovakia and subsequently of the

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

.

Financial Part Donated to Andrej Dyńko

Václav Havel donated the financial part to

Andrej Dyńko

Andrej Dyńko ( be, Андрэй Дынько) (born 1974) is a Belarusian journalist. In 2000-2006 he served the chief editor of the oldest Belarusian weekly newspaper '' Naša Niva''. Later he headed magazines Nasha Historyja (''Наша гі� ...

, the editor-in-chief of the independent Belarusian newspaper

Nasha Niva

''Nasha Niva'' ( be, Наша Ніва, Naša Niva, lit. "Our field") is one of the oldest Belarusian weekly newspapers, founded in 1906 and re-established in 1991. ''Nasha Niva'' became a cultural symbol, due to the newspaper's importance as a ...

. Openly critical to

President Lukashenko's regime, and the only major newspaper written in Belarusian, Nasha Niva has become an important symbol of freedom and independence. Dynko is a Graduate from

Minsk State Linguistic University, and holds an MA in International Relations. Until August 2000, he also taught at his alma mater. From 2002, Dynko has been the Vice-President of the Belarusian

PEN Center.

Fourth - Lord Robertson of Port Ellen

Lord Robertson

Lord Robertson, born on the

Isle of Islay

Islay ( ; gd, Ìle, sco, Ila) is the southernmost island of the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Known as "The Queen of the Hebrides", it lies in Argyll just south west of Jura and around north of the Northern Irish coast. The island's capital i ...

in Scotland, was elected to the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

in 1978. After the

Labour Party won the elections in 1997,

Prime Minister Blair appointed him as the

Defence Secretary

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in so ...

of the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

. In August 1999 he was selected as the tenth

Secretary General of

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

, and the same month received a life peerage, taking the title Lord Robertson of Port Ellen. For 7 years he was on the

Council of the Royal Institute of International Affairs (Chatham House) where he now serves as Joint President. He has been awarded the Grand Cross of the German Order of Merit and the Grand Cross of the Order of the

Star of Romania

The Order of the Star of Romania (Romanian: ''Ordinul Steaua României'') is Romania's highest civil Order and second highest State decoration after the defunct Order of Michael the Brave. It is awarded by the President of Romania. It has five ra ...

and was named joint Parliamentarian of the Year in 1993 for his role during the

Maastricht Treaty

The Treaty on European Union, commonly known as the Maastricht Treaty, is the foundation treaty of the European Union (EU). Concluded in 1992 between the then-twelve member states of the European Communities, it announced "a new stage in the ...

ratification. He was appointed a member of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth's

Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

in May 1997.

Financial Part Donated to David Hodan

Lord Robertson donated the financial part to David Hodan, who first met Lord Robertson in May 2003. Encouraged by Ms

Bela Gran Jensen, founder of the "Centipede" movement, he wrote an essay named "What I would do if I were General Secretary of NATO". Lord Robertson read the essay and asked to meet David, saying that he especially liked the quotation from

Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is conside ...

which David used in the essay: "I am interested in my future because that is where I am going to spend the rest of my life." The meeting took place within sight of

Prague Castle

Prague Castle ( cs, Pražský hrad; ) is a castle complex in Prague 1 Municipality within Prague, Czech Republic, built in the 9th century. It is the official office of the President of the Czech Republic. The castle was a seat of power for king ...

– which David likes to call his "future seat". A student at the

Terezie Brzková

Terezie Brzková (11 January 1875 – 19 November 1966) was a Czechoslovak film actress. She appeared in 28 films between 1939 and 1959. She is buried at the Vyšehrad Cemetery in Prague.

Selected filmography

* '' The Magic House'' (1939)

* ...

33-35 school in

Pilsen (of which

Marc S. Ellenbogen is a Patron), his ambition is one day to become President of this country. As he says himself, he is an "ordinary boy" with the interests of a boy of his age – he reads a lot and works with computers, but he also has a special interest in current world events, politics and medicine. He is particularly concerned about parts of the world where children suffer as a result of military conflict. David is a boy with the courage to say what he thinks, and to have dreams which may come true.

Fifth - Miloš Forman

Miloš Forman

Jan Tomáš "Miloš" Forman (; ; 18 February 1932 – 13 April 2018) was a Czech and American film director, screenwriter, actor, and professor who rose to fame in his native Czechoslovakia before emigrating to the United States in 1968.

Forman ...

, born in

Čáslav

Čáslav (; german: Tschaslau) is a town in Kutná Hora District in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 10,000 inhabitants. The town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument zone.

Adminis ...

outside Prague, he lost both his parents in the

Nazi death camps. After studying in Prague he made his first feature film in 1963:

''Black Peter'', an autobiographical account of a teenager in a small Czech town. He gained international recognition with ''

Loves of a Blonde

''Loves of a Blonde'' ( cs, Lásky jedné plavovlásky), also known as ''A Blonde in Love'', is a 1965 Czechoslovak comedy-drama film directed by Miloš Forman that follows a young woman, Andula, who has a routine job in a shoe factory in provinci ...

''. Despite this, his next film, ''

The Firemen's Ball

''The Firemen's Ball'' (or ''The Fireman's Ball''; cs, Hoří, má panenko - "Fire, my lady") is a 1967 comedy film directed by Miloš Forman. It is set at the annual ball of a small town's volunteer fire department, and the plot portrays a se ...

'', attracted the attention of the Communist authorities and was banned. After the

Soviet invasion of 1968, Forman settled in America, winning international fame with ''

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest may refer to:

* ''One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest'' (novel), a 1962 novel by Ken Kesey

* ''One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest'' (play), a 1963 stage adaptation of the novel starring Kirk Douglas

* ''One Flew Over the ...

''. It swept the Academy Awards, winning all five major Oscars. From his earliest Czechoslovakian work through his American period to ''

Goya's Ghosts

''Goya's Ghosts'' is a 2006 biographical drama film, directed by Miloš Forman (his final directorial feature before his death in 2018), and written by him and Jean-Claude Carrière. The film stars Javier Bardem, Natalie Portman and Stellan Skarsg ...

'', Forman's directing remains close to the reality of life; its absurdity and transforming joys.

Financial Part Donated to the Film Academy of Miroslav Ondříček in Písek

Financial part was donated to the Film Academy of

Miroslav Ondříček

Miroslav Ondříček (4 November 1934 – 28 March 2015) was a Czech cinematographer who worked on over 40 films, including '' Amadeus'', ''Ragtime'' and '' If....''.

Life and career

Miroslav Ondříček was born in Prague, Czechoslovakia (now ...

in Písek. The Film Academy divided financial part into three parts of 50,000 crowns each to provide scholarships for students. The first recipient was the 27-year-old student of film, Martin Palouš, who received the Award from

Marc S. Ellenbogen on 11 October 2007 at the celebratory opening of the

Písek Film Festival.

Sixth - Romania's King Michael I

His Majesty King

Michael I of Romania

Michael I ( ro, Mihai I ; 25 October 1921 – 5 December 2017) was the last King of Romania, reigning from 20 July 1927 to 8 June 1930 and again from 6 September 1940 until his forced abdication on 30 December 1947.

Shortly after Michael's ...

(born 1922; died 2017) has twice been Head of State in Romania: from 1927 to 1930 and from 1940 to 1947, when he was deposed by the Communists, stripped of his citizenship, and banished from the country. Over the next fifty-five years he worked as a mechanic, commercial pilot and businessman and, with his wife Queen Anne, Princess of Bourbon-Parma, brought up their five daughters. In 1997 he said in an interview: "The King is head of state but he is also the first servant of the people. Never forget that."

Financial Part Donated to Petrisor Ostafie

A student of Medical Bio-engineering in

Iasi,

Petrisor Ostafie is an example of someone who, on receiving something, returns more than was given. He proved this by being first a volunteer and then a member of the Board of the Alaturi de Voi (Close to You) Romania Foundation. In addition, he exudes in speaking on numerous occasions about what it means to live with

HIV and has become an example for many young people in the same situation. Petrisor has spent over 4000 hours of voluntary work on programs developed by the Alaturi de Voi Romania Foundation and has brought hope to over 200 young people living with HIV.

Seventh - Alexander Milinkevich (Alaksandar Milinkievič)

Alaksandar Milinkievič

Alaksandar Uladzimyeravič Milinkyevič ( be, Аляксандар Уладзімеравіч Мілінкевіч, translit=Alyaksandar Uladzimyeravich Milinkyevich, russian: Александр Владимирович Милинкевич, trans ...

became involved in the local politics of his home city,

Hrodna

Grodno (russian: Гродно, pl, Grodno; lt, Gardinas) or Hrodna ( be, Гродна ), is a city in western Belarus. The city is located on the Neman River, 300 km (186 mi) from Minsk, about 15 km (9 mi) from the Polish b ...

, in the 1980s. Four years in

Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques d ...

setting up the Faculty of Physics at

Sétif University, had given him a wider experience of the world than his contemporaries. After the

fall of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

, he entered national politics, becoming Chief of Staff to one of the opposition leaders. In 2005 he was chosen by the

United Democratic Forces of Belarus

The United Democratic Forces of Belarus ( be, Аб'яднаныя дэмакратычныя сілы Беларусі; russian: Объединённые демократические силы) is a coalition of political parties that oppose t ...

as joint candidate of the opposition in the

presidential elections of 2006, to stand against the authoritarian

Alexander Lukashenko

Alexander Grigoryevich Lukashenko (as transliterated from Russian; also transliterated from Belarusian as Alyaksand(a)r Ryhoravich Lukashenka;, ; rus, Александр Григорьевич Лукашенко, Aleksandr Grigoryevich Luk ...

. He was held by the police before and after the elections on false charges of drunken driving, forgery, drug trafficking and leaving Belarus illegally.

Financial Part Donated to Pavel Sieviarynets

Paval Sieviaryniec

Paval Sieviaryniec ( be, Павал Севярынец, born December 30, 1976) is a Belarusian journalist and Christian democratic politician and youth leader and one of the founders of the Young Front.

Since June 7, 2020 he is under arrest. A ...

is a prominent young Belarusian politician leader of the

Christian Democratic Party

__NOTOC__

Christian democratic parties are political parties that seek to apply Christian principles to public policy. The underlying Christian democracy movement emerged in 19th-century Europe, largely under the influence of Catholic social tea ...

and founder of the

Young Front

Young Front ( be, Малады Фронт, malady front, МФ) is a Belarusian youth movement registered in the Czech Republic. It is the largest youth organisation of Belarus declaring democratic values. It is a member of the European Democra ...

that is one of the most persecuted political organisations in Belarus. He is also a talented publicist, author of a number of books and articles in which he presents his ideas and values, calling Belarusians to a national awakening and protest against autocratic rule.

Eighth - In honor of Desmond Mullan

In honor of

Desmond Mullan (in memoriam). Mullan, managing director of

Volvo

The Volvo Group ( sv, Volvokoncernen; legally Aktiebolaget Volvo, shortened to AB Volvo, stylized as VOLVO) is a Swedish multinational manufacturing corporation headquartered in Gothenburg. While its core activity is the production, distributio ...

Auto Czech 2000-2006, was one of the Prague Society's main supporters. He was involved in many fields during his time in the Czech Republic: Vice-Chairman of the

British Chamber of Commerce

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

, he was also well known for his support of the

International School of Prague

The International School of Prague (ISP) is an independent, English-speaking, non-profit, international school in Prague, Czech Republic.

Established in 1948, ISP is both the oldest and largest international school in the Czech Republic, with ...

, and an active member of the congregation of the Roman Catholic Church of

St Thomas in Mala Strana. Hundreds of friends attended his funeral in St Thomas's. For his warm heart, generosity, and for all the good deeds he and his wife Helen did while they lived in Prague, the Prague Society had the honor to make him a special recipient of the HRE Citizenship Award in memoriam. This was a special award with no secondary nominee.

Ninth - The 14th Dalai Lama

The

14th Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso, is both the head of state and the spiritual leader of

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

. In 1950 the Dalai Lama was called upon to assume full political power after

China's invasion of Tibet in 1949. In 1954, he went to Beijing for peace talks with

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

and other Chinese leaders, including

Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping (22 August 1904 – 19 February 1997) was a Chinese revolutionary leader, military commander and statesman who served as the paramount leader of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC) from December 1978 to November 1989. Aft ...

and

Chou Enlai. Since the Chinese invasion of Tibet, the Dalai Lama has appealed to the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

on the question of Tibet. The General Assembly adopted

three resolutions on Tibet in 1959, 1961 and 1965. In September 1987 the Dalai Lama proposed the Five Point Peace Plan for Tibet as the first step towards a peaceful solution to the worsening situation in Tibet. In 1989 he was awarded the

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolo ...

for his non-violent struggle for the liberation of Tibet. He has consistently advocated policies of non-violence, even in the face of extreme aggression. He also became the first Nobel Laureate to be recognized for his concern for global environmental problems.

Financial Part Donated to Dobrý Anjel

The 14th Dalai Lama donated the financial part to the Slovak charity "

Dobrý anjel

Dobrý anjel (translated from Slovak as ''Good Angel'') is a non-profit charitable organization founded by Igor Brossmann and Andrej Kiska in 2006. This organization tries to help families with children that are in a difficult financial situatio ...

" (Good Angel) which helps families of children that suffer from cancer or other insidious diseases such as: cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, chronic renal failure, muscular dystrophy or down syndrome. Donations are made to families based on financial need. The charity was founded by Igor Brossmann and

Andrej Kiska

Andrej Kiska (; born 2 February 1963) is a Slovak politician, entrepreneur, writer and philanthropist who served as the fourth president of Slovakia from 2014 to 2019. He ran as an independent candidate in the 2014 presidential election in which ...

.

Tenth - Adam Michnik

Adam Michnik

Adam Michnik (; born 17 October 1946) is a Polish historian, essayist, former dissident, public intellectual, and editor-in-chief of the Polish newspaper, ''Gazeta Wyborcza''.

Reared in a family of committed communists, Michnik became an opponen ...

is the editor-in-chief of ''

Gazeta Wyborcza

''Gazeta Wyborcza'' (; ''The Electoral Gazette'' in English) is a Polish daily newspaper based in Warsaw, Poland. It is the first Polish daily newspaper after the era of " real socialism" and one of Poland's newspapers of record, covering the ...

'', the biggest daily in Poland and the first independent news daily after Communism. A historian and co-founder of KOR (Committee for the Defense of Workers) 1976, he was detained many times during 1965-1980 and was a prominent Solidarity activist during the 80s, and spent a total of six years in Polish prisons for activities opposing the

communist regime

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Cominte ...

. Member of the Round Table Talks in 1989; member of the first non-communist parliament 1989-1991. He is the Laureat of many prizes and titles:

Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award

The Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award, was created by the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial in 1984, now known as the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights to honour individuals around the world who have shown great courage and have made a significant contr ...

;

The Erasmus Prize; The Francisco Cerecedo Journalist Prize as a first non-Spanish author; Grand Prince Giedymin Order;

Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon B ...

; recipient of a

doctorate honoris causa from The

New School for Social Research in New York, from the

University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public land-grant research university in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. ...

,

University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

and from

Connecticut College

Connecticut College (Conn College or Conn) is a private liberal arts college in New London, Connecticut. It is a residential, four-year undergraduate institution with nearly all of its approximately 1,815 students living on campus. The college w ...

; honorary senator of the

University of Ljubljana

The University of Ljubljana ( sl, Univerza v Ljubljani, , la, Universitas Labacensis), often referred to as UL, is the oldest and largest university in Slovenia. It has approximately 39,000 enrolled students.

History Beginnings

Although certain ...

; and

honorary professor

Honorary titles (professor, reader, lecturer) in academia may be conferred on persons in recognition of contributions by a non-employee or by an employee beyond regular duties. This practice primarily exists in the UK and Germany, as well as in m ...

of the

Kyiv Mohyla Academy.

Financial Part Donated to Young Journalists

Michnik presented the financial portion of the award to two young journalists at the Polish daily ''

Gazeta Wyborcza

''Gazeta Wyborcza'' (; ''The Electoral Gazette'' in English) is a Polish daily newspaper based in Warsaw, Poland. It is the first Polish daily newspaper after the era of " real socialism" and one of Poland's newspapers of record, covering the ...

'',

Juliusz Kurkiewicz and

Aleksandra Klich-Siewiorek.

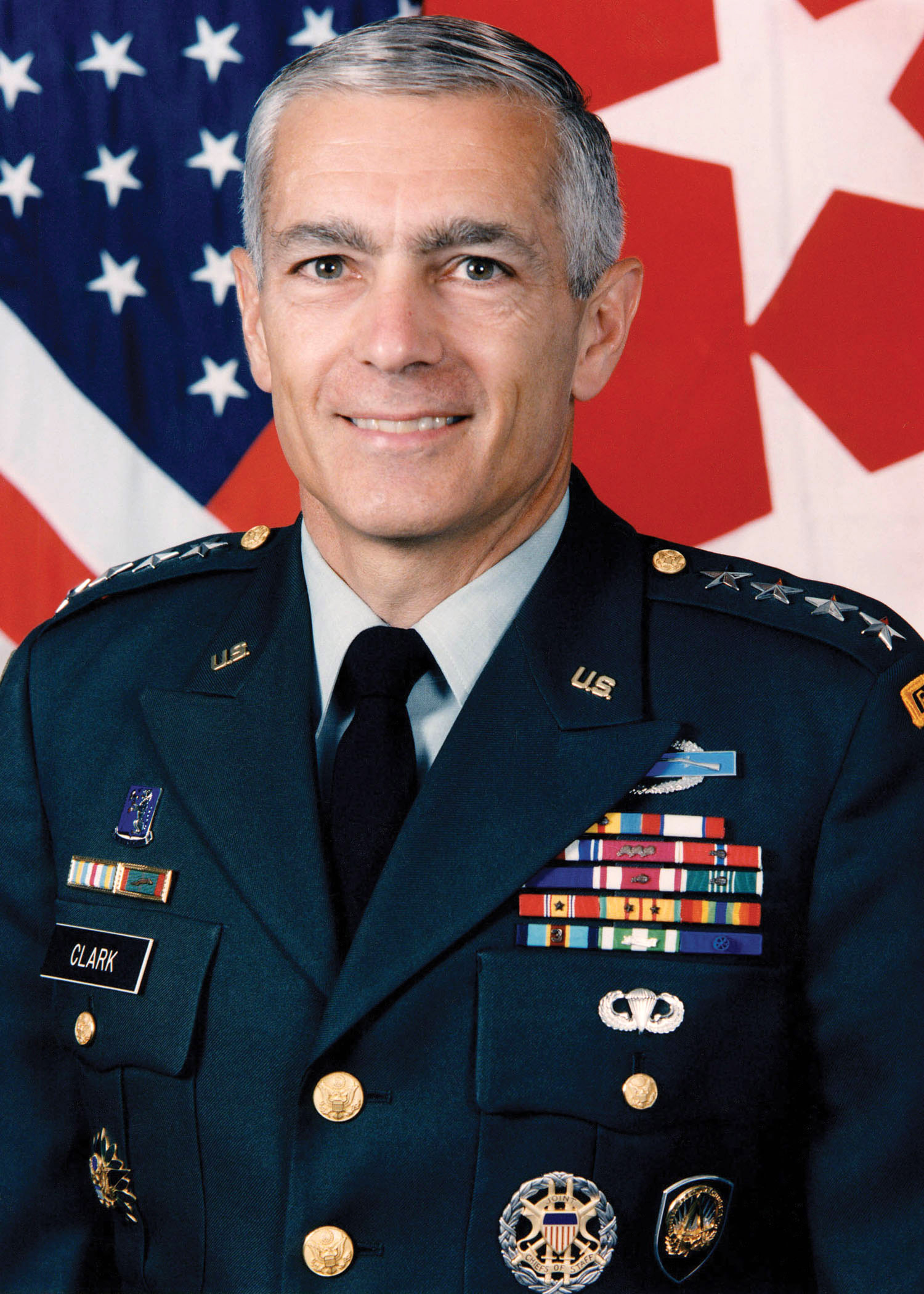

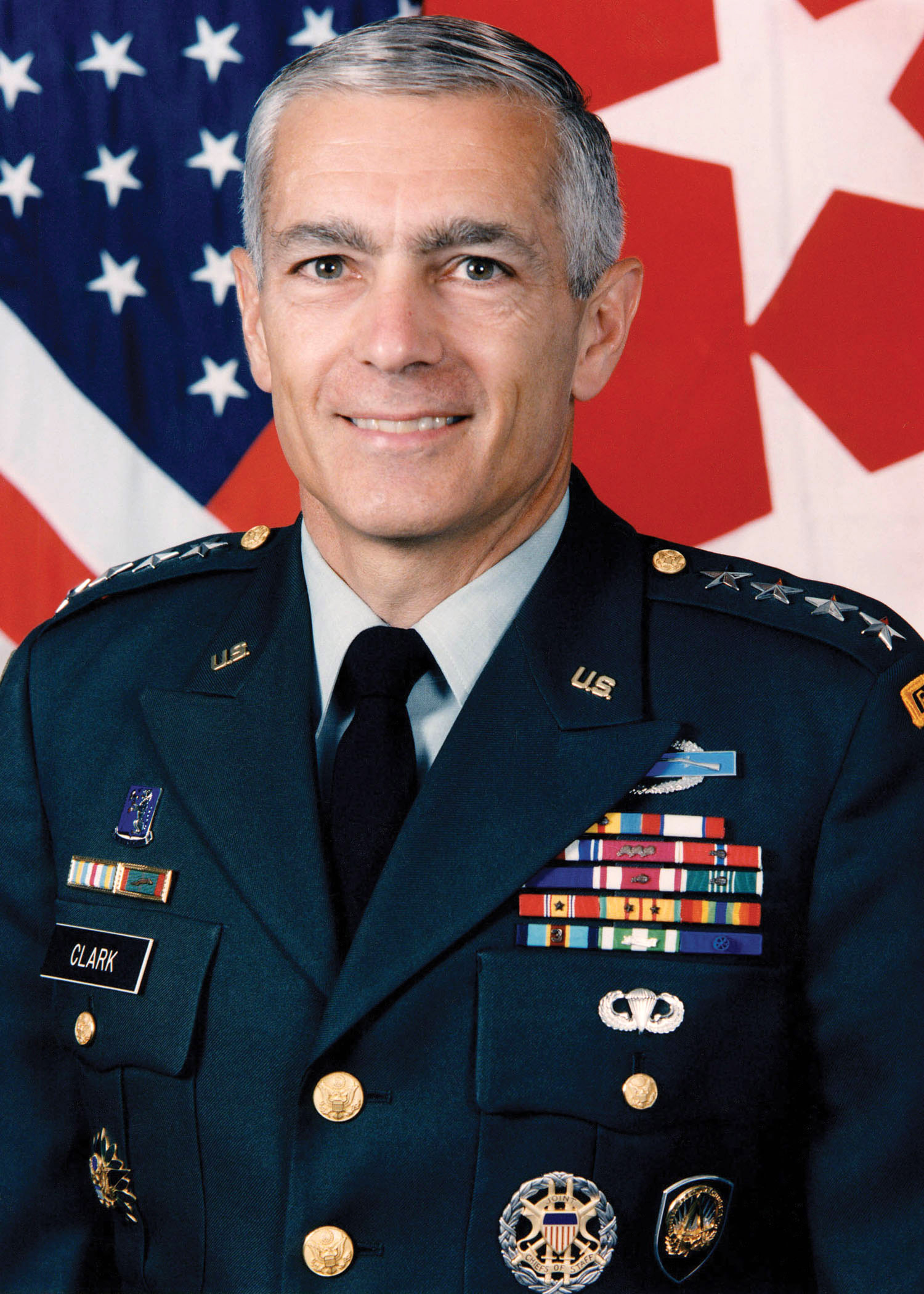

Eleventh - Wesley Clark, ''Jiří Dienstbier and Andrés Pastrana''

Wesley Clark

Wesley Kanne Clark (born December 23, 1944) is a retired United States Army officer. He graduated as valedictorian of the class of 1966 at West Point and was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship to the University of Oxford, where he obtained a degree ...

served the United States with honor for 34 years. He was the

Supreme Allied Commander

Supreme Allied Commander is the title held by the most senior commander within certain multinational military alliances. It originated as a term used by the Allies during World War I, and is currently used only within NATO for Supreme Allied Com ...

of NATO (

SACEUR

The Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) is the commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization's (NATO) Allied Command Operations (ACO) and head of ACO's headquarters, Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE). The commander is ...

) and a US presidential candidate in 2004. Almost immediately after becoming

SACEUR

The Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) is the commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization's (NATO) Allied Command Operations (ACO) and head of ACO's headquarters, Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE). The commander is ...

Clark started pushing for NATO membership for Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic. He became the first

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

commander to visit Prague after the fall of Communism. His legacy in the region is marked by these efforts and

Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a international recognition of Kosovo, partiall ...

.

Twelfth - ''Wesley Clark,'' Jiří Dienstbier ''and Andrés Pastrana''

As one of Czechoslovakia's most respected foreign correspondents,

Jiří Dienstbier

Jiří Dienstbier (20 April 1937 – 8 January 2011) was a Czech politician and journalist. Born in Kladno, he was one of Czechoslovakia's most respected foreign correspondents before being fired after the Prague Spring. Unable to have a livelih ...

lost his job after the end of

Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First ...

and had menial jobs for the following two decades. During this time he became a signatory of

Charta 77, helped to restart

Lidové Noviny

''Lidové noviny'' (''People's News'', or ''The People's Newspaper'', ) is a daily newspaper published in Prague, the Czech Republic. It is the oldest Czech daily still in print, and a newspaper of record.[Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution ( cs, Sametová revoluce) or Gentle Revolution ( sk, Nežná revolúcia) was a non-violent transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring from 17 November to 28 November 1989. Popular demonstrations agains ...]

, becoming the first

Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

of post-Communist Czechoslovakia in 1989.

Dienstbier became a hero to millions when, together with then German Foreign Minister

Hans-Dietrich Genscher

Hans-Dietrich Genscher (21 March 1927 – 31 March 2016) was a German statesman and a member of the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP), who served as Federal Minister of the Interior from 1969 to 1974, and as Federal Minister for Foreign Affa ...

and Austrian Foreign Minister

Alois Mock, he cut the "iron curtain." The images spread across the world.

As a politician he played a pre-eminent role in shaping post-Communist foreign policy in a democratic Czechoslovakia between 1989 and 1993 and from Central Europe to Asia to the Middle East. When the Czech Republic and Slovakia separated as states, he played a leading role as a commentator and thoughtful rebel. Finally he entered politics again in the 21st century as a Senator and Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Financial Part Donated To Jiřina Dienstbierová

The financial part of Jiří Dienstbier's award was donated to fund the design and publishing of a new book, "Jiří Dienstbier – rozhlasový zpravodaj."

Thirteenth - ''Wesley Clark, Jiří Dienstbier and'' Andrés Pastrana

Andrés Pastrana

Andres or Andrés may refer to:

*Andres, Illinois, an unincorporated community in Will County, Illinois, US

*Andres, Pas-de-Calais, a commune in Pas-de-Calais, France

*Andres (name)

*Hurricane Andres

* "Andres" (song), a 1994 song by L7

See also ...

was President of Colombia from 1998-2002. As a lawyer and journalist, Pastrana had been dedicated to fighting corruption and the

Colombian drug trade that lies at the root of his country's civil conflict already before he became president. As President he was determined to solve the armed conflict - through negotiation rather than force. While

Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the ...

has not found peace to this day, its army found itself in a much better position to face the major

guerrilla organizations after Pastrana's term. During his administration Colombia regained the support of the international community that previously had turned its back on it and the country gained economic support and military aid. At the same time he left Colombia's guerrilla organizations politically undermined with Colombians regarding them as terrorists rather than freedom fighters.

Fourteenth - Věra Čáslavská

Věra Čáslavská

en, the love of Tokyo ja, 「オリンピックの名花」 en, darling of the Olympic Games

, country = Czechoslovakia

, formercountry =

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Prague, Czechoslovakia ( occupied by Germany 1939– ...

won seven Olympic gold medals before she was forced into retirement and for many years was denied the right to travel, work and attend sporting events following her protest against the Soviet-led occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968. A signatory of

The Two Thousand Words manifesto, Čáslavská was known for her outspoken support of the Czechoslovak democratization movement. At the

1968 Olympics in Mexico City she quietly looked down and away while the Soviet national anthem was played during medal ceremonies. Her subtle but highly public and widely understood protest resulted in her becoming a persona non grata in the new regime.

Financial Part Donated to Primary School in Černošice

The financial part of Věra Čáslavská was donated to eight hundred children, and to support construction of a sports hall at Primary School in

Černošice.

Fifteenth - Iva Drápalová

'

Iva Drápalová'' refused to cooperate with the

StB, the Communist secret police, even when she and her family were threatened. In 1968 she started working for the

Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. new ...

bureau in Prague when, following the crushing of the

Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First ...

, nobody else wanted the job. Initially she only agreed to help out as a translator for one week. Two year's later she had become AP's Prague correspondent. After she retired in 1988 she was a translator at

Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution ( cs, Sametová revoluce) or Gentle Revolution ( sk, Nežná revolúcia) was a non-violent transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring from 17 November to 28 November 1989. Popular demonstrations agains ...

press conferences and later she worked as a consultant for the

L.A. Times.

Financial Part Donated to Štěpán Ripka

The financial part of Iva Drápalová was given to Štěpán Ripka as the recipient of the monetary part of her award. Štěpán Ripka is a social researcher and policy analyst who studies

Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

Places Australia

* Roma, Queensland, a town

** Roma Airport

** Roma Courthouse

** Electoral district of Roma, defunct

** Town of Roma, defunct town, now part of the Maranoa Regional Council

* Roma Street, Brisbane, a ...

communities, advises the

Open Society Institute

Open Society Foundations (OSF), formerly the Open Society Institute, is a grantmaking network founded and chaired by business magnate George Soros. Open Society Foundations financially supports civil society groups around the world, with a st ...

and the Czech Government he also chairs the Platform for Social Housing and pursues a PhD in social anthropology at

Charles University

)

, image_name = Carolinum_Logo.svg

, image_size = 200px

, established =

, type = Public, Ancient

, budget = 8.9 billion CZK

, rector = Milena Králíčková

, faculty = 4,057

, administrative_staff = 4,026

, students = 51,438

, under ...

in Prague.

Sixteenth - Tony Fitzjohn and Souad Mekhennet

Tony Fitzjohn is a legendary

conservationist who worked extensively with George Adamson (of "Born Free" fame) and currently runs a successful sanctuary for rhinos and African wild dogs in

Mkomazi National Park

Mkomazi National Park is located in northeastern Tanzania on the Kenyan border, in Kilimanjaro Region and Tanga Region. It was established as a game reserve in 1951 and upgraded to a national park in 2006.

The park covers over , and is dominat ...

in

Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands ...

. Fitzjohn left for Africa in his early twenties and immediately fell in love with the continent. He spent 18 years in Kora in northern

Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

releasing lions and other big cats back into the wild. In the late 1980s he was invited by Tanzanian government to help to establish a new national park in the area that was then Mkomazi Game Reserve. He led the building of the infrastructure and later established and stocked the first successful rhinoceros sanctuary in Tanzania for which he developed dedicated anti-poaching units. As he emphasizes close cooperation with neighboring communities, he developed special programmes that allow local children and students to visit Mkomazi National Park and a rhino sanctuary.

He provides local communities with clean water supplies, dispensary and Flying Doctor services - with a notable achievement of completing construction of a new secondary school for 400 children. In 2006, Tony Fitzjohn was recognized as an Officer of the

Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

for his life-time commitment to conservation.

Souad Mekhennet

Souad Mekhennet (born 1978 in Frankfurt am Main) is a German journalist and author who has written or worked for ''The New York Times'', ''Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung'', ''The Washington Post'', The Daily Beast and German television channel Z ...

has long been recognized for her coverage of the

Arabic-speaking world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western As ...

- especially women's issues. She was born in

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

- the daughter of a Turkish mother and Moroccan father. She studied international relations, political science, sociology, psychology and history at the

University of Frankfurt. She also attended the

Henri-Nannen School of Journalism in

Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

, later taking courses at the

City University of New York - School of Journalism. That led to her career as a reporter for the

New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

. Since shortly after September 11, she has been reporting about

radical Islamic movements. Her articles tell stories of hope, fear and the real life of Muslims throughout the world as Muslim countries undergo dramatic and traumatic changes. Currently she is a moderator and public speaker and works for the

Washington Post Newspaper, German TV channel

ZDF and

The Daily Beast

''The Daily Beast'' is an American news website focused on politics, media, and pop culture. It was founded in 2008.

It has been characterized as a "high-end tabloid" by Noah Shachtman, the site's editor-in-chief from 2018 to 2021. In a 20 ...

. Mekhennet has been interviewed for various TV and radio shows in the US and Europe. She is a visiting fellow at the

Weatherhead Centre at

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

, and at the

School for Advanced and International Studies (SAIS) at the Johns Hopkins University. Under great threat to herself, Mekhennet has continued to pursue the plight of peoples in conflict zones.

Financial Part Donated to Praunheimer Werkstätten and Arthur F. Sniegon

The financial parts were divided as Souad Mekhennet nominated organizations Praunheimer Werkstätten (working with challenged people) and Die Weisser Ring (Helping the victims of crimes), Tony Fitzjohn nominated Arthur F. Sniegon which is an aspiring conservationist from Czech Republic.

Seventeenth - Magda Vášáryová and Zdeněk Tůma

Magda Vášáryová

Magda Vášáryová born August 26 - of mixed German, Hungarian and Slovak origins - is known for being one of Czechoslovakia's great actresses. Vaclav Havel wanted her to become the Vice President of democratic Czechoslovakia after 1989 - but she declined. In 1999, she became the first female presidential candidate in

Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

. In 1971 she completed her studies at Bratislava's

Comenius University

Comenius University in Bratislava ( sk, Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave) is the largest university in Slovakia, with most of its faculties located in Bratislava. It was founded in 1919, shortly after the creation of Czechoslovakia. It is name ...

. Until 1989, she acted in several theaters including the

Slovak National Theatre

The Slovak National Theater ( sk, Slovenské národné divadlo, abbr. SND) is the oldest professional theatre in Slovakia, consisting of three ensembles: opera, ballet, and drama. Its history begins shortly after the establishment of the first ...

after a long movies career. She was the Ambassador of Czechoslovakia in Austria (1990– 1993). After the split of Czech and Slovakia, she became Ambassador to Poland (2000–2005). From February 2005 to July 2006 she held the position of State Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Slovakia. In the 2006 parliamentary elections, she was elected to the National Council of the Slovak Republic for Slovak Democratic and Christian Union - Democratic Party. She spent here entire career fighting Communism and corruption.

Zdeněk Tůma

Zdeněk Tůma (born 19 October 1960) is a Czech economist, who was the Governor of the Czech National Bank from 1 December 2000 to 30 June 2010. He had previously served as Vice Governor of the Bank from 13 February 1999 to 30 November 2000.

Car ...

(born České Budějovice, 1960) was Governor of the Czech Central Bank for 10 years. He graduated from the

University of Economics, Prague, later finishing his postgraduate studies at the

Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences

The Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (Czech: ''Československá akademie věd'', Slovak: ''Česko-slovenská akadémia vied'') was established in 1953 to be the scientific center for Czechoslovakia. It was succeeded by the Czech Academy of Scienc ...

. He was the Chief Economist at Patria Finance Investment Bank in the 90's. In 1998 he moved to the

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) is an international financial institution founded in 1991. As a multilateral developmental investment bank, the EBRD uses investment as a tool to build market economies. Initially fo ...

where he became a member of the Executive Board. In early 1999, Tuma was appointed Vice-Governor of the Czech National Bank. In December 2000, he was made Governor which he held until 2010. In this capacity he sat on the Boards of the

European Central Bank

The European Central Bank (ECB) is the prime component of the monetary Eurosystem and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) as well as one of seven institutions of the European Union. It is one of the world's most important centra ...

,

International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster glo ...

, and

Bank for International Settlement. He is currently a partner in

KPMG

KPMG International Limited (or simply KPMG) is a multinational professional services network, and one of the Big Four accounting organizations.

Headquartered in Amstelveen, Netherlands, although incorporated in London, England, KPMG is a net ...

Czech Republic. He is an external Lecturer at the Institute of Economic Studies of Charles University, where he covers monetary policy and financial regulation. He is a member of the Scientific Boards of the

Czech Technical University

Czech Technical University in Prague (CTU, cs, České vysoké učení technické v Praze, ČVUT) is one of the largest universities in the Czech Republic with 8 faculties, and is one of the oldest institutes of technology in Central Europe. I ...

(CVUT) and the

University of South Bohemia. He is on the Statutory Boards of the Prague-based

Academy of Performing Arts, the University of Economics and

CERGE-EI Foundation. He is on the Board of Governors of

English College and the Supervisory Board of Výbor dobré vůle – Foundation of Olga Havlová. He was the President of the Czech Economic Society from 1999 to 2001. During his tenure, Tuma was consistently recognized as one of the World's top-ten Central Bankers.

Financial Part Donated to Petr Koukal and Živena

The financial part was divided into 2 parts as Magda Vášáryova has chosen the oldest women organization in Europe -

Živenaand its activity towards females from the Roma community in Slovakia and Zdeněk Tuma has chosen

Petr Koukal (badminton)

Petr Koukal (; born 14 December 1985) is a Czech professional badminton player.

Biography

Koukal started playing badminton in 1993, at a club owned by his father in Hořovice, and made his debut in the international tournament in 2000. In 2003 h ...

, Czech Olympic winner and his foundation which is helping men with testicle cancer.

Eighteenth - The Santa Marta Group and its President, Cardinal Vincent Nichols

Th

Santa Marta Groupcombats

modern slavery

Contemporary slavery, also sometimes known as modern slavery or neo-slavery, refers to institutional slavery that continues to occur in present-day society. Estimates of the number of enslaved people today range from around 38 million to 46 mil ...

and

human trafficking

Human trafficking is the trade of humans for the purpose of forced labour, sexual slavery, or commercial sexual exploitation for the trafficker or others. This may encompass providing a spouse in the context of forced marriage, or the extr ...

globally. In particular it focuses on bringing together the heads of national and international police and law enforcement agencies along with international organisations to look at how they can work with the Catholic Church to help victims. The Santa Marta Group is named after the home of

Pope Francis

Pope Francis ( la, Franciscus; it, Francesco; es, link=, Francisco; born Jorge Mario Bergoglio, 17 December 1936) is the head of the Catholic Church. He has been the bishop of Rome and sovereign of the Vatican City State since 13 March 2013 ...

and was initiated by the

Catholic Bishops' Conference for England and Wales. It was established in Rome in 2014 when police chiefs and Catholic bishops came together in the presence of Pope Francis. Cardinal

Vincent Nichols

Vincent Gerard Nichols (born 8 November 1945) is an English cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church, Archbishop of Westminster and President of the Catholic Bishops' Conference of England and Wales. He previously served as Archbishop of Birmin ...

is the President of the Santa Marta Group,

Archbishop of Westminster

The Archbishop of Westminster heads the Roman Catholic Diocese of Westminster, in England. The incumbent is the metropolitan of the Province of Westminster, chief metropolitan of England and Wales and, as a matter of custom, is elected presid ...

and President of the Catholic Bishops' Conference of England and Wale. Modern slavery is one of the gravest criminal challenges confronting the international community. The scale of the problem is such that now, according to some studies, it ranks as the second most profitable worldwide criminal enterprise after the illegal arms trade. This exploitation can take many forms including forced labour, sexual exploitation, domestic servitude, forced criminality and organ harvesting. Both

Pope Benedict and Pope Francis continually drew the attention of the

Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* Chri ...

and wider world to the moral and human crisis evident in this widespread human exploit

Financial Part Donated to Caritas Bakhita House

Cardinal Vincent Nicols intends to donate the money from the award to Caritas Bakhita House in the Diocese of Westminster for their work to help victims of trafficking get back on their feet, whether they wish to return home or find suitability in this country.

"Special Commemorative Award" to Ján Kuciak & Martina Kušnírová (Slovakia) and Tom Nicholson (Canada)

Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová receive a Special Commemorative Award for their courageous commitment to Kuciak's work as an investigative reporter. The couple were murdered in their home in February 2018 in an attempt to silence them. Kuciak, in his work, focused on politically related fraud. At the time of his death he had been working on a story on the influence of the

Calabrian mafia, the 'Ndrangheta,' on business and politics in Slovakia.

The murders caused mass protests and a lasting political crisis in Slovakia. They led to the resignation of the prime minister and his cabinet, as well as the head of police. At the time of writing no one has been charged with the murders.

Tom Nicholson is an investigative journalist who has covered Slovakia for the past 20 years. He was editor-in-chief at the

Slovak Spectator and head of investigative reporting at the SME daily. Later he worked for the weekly

Trend

A fad or trend is any form of collective behavior that develops within a culture, a generation or social group in which a group of people enthusiastically follow an impulse for a short period.

Fads are objects or behaviors that achieve shor ...

.

He is best known for making public the '

Gorilla' scandal in Slovakia in 2012. 'Gorilla' is considered by many the biggest corruption story in Slovak history. It is named after a Slovak Secret Service wiretap file which alleges massive fraud at the highest level of Slovak politics and business. It exposed politicians, public officials and business representatives discussing kickbacks in return for procurement and privatization contracts and rocked the

Slovak political scene.

Nicholson lives in

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

and is finishing a book on ties between politics and organized crime.

Nineteenth - Ing. Ivan M. Havel and Ing. Ivan Chvatik

Born in 1938,

Ivan Havel was a dissident and one of the outstanding figures of the scientific community in the Czech Republic of the past decades. He dedicated his life to academics and research in the field of computer science. After leaving Czechoslovakia in 1969 for doctoral studies at the

University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant un ...

, not many believed that he would ever come back. Before the communist regime collapsed in 1989, he was engaged in semi-official scientific work and often hosted discussion groups inviting dissidents and academics in his apartment overlooking the

River Vltava in Prague. He also cooperated with

samizdat

Samizdat (russian: самиздат, lit=self-publishing, links=no) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the document ...

editions, for which he was harassed and briefly detained on several occasions by the

StB. After the

Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution ( cs, Sametová revoluce) or Gentle Revolution ( sk, Nežná revolúcia) was a non-violent transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring from 17 November to 28 November 1989. Popular demonstrations agains ...

he decided to distance himself from politics and turned his focus to science and academia. He later co-founded the Center of Theoretical Studies (jointly with Ivan Chvatik) in Prague and held the position of

Editor-in-Chief of the esteemed scientific journal

Vesmír for over two decades. He was a member of

Academia Europaea

The Academia Europaea is a pan-European Academy of Humanities, Letters, Law, and Sciences.

The Academia was founded in 1988 as a functioning Europe-wide Academy that encompasses all fields of scholarly inquiry. It acts as co-ordinator of Europea ...

and several other professional societies, and served on boards of various academic institutions and cultural foundations.

Ivan Chvatíkwas born in Olomouc on 15 September 1941. He graduated from nuclear physics at the

Czech Technical University in Prague

Czech Technical University in Prague (CTU, cs, České vysoké učení technické v Praze, ČVUT) is one of the largest universities in the Czech Republic with 8 faculties, and is one of the oldest institutes of technology in Central Europe. It ...

. After being briefly employed at the Department of Logic at Aritma, he worked for more than twenty years as the head of the Technical Department of the Computer Centre of the Machine Technology Factories in Prague (1967-1989). He was in charge of the Swedish computer

Datasaab Datasaab was the computer division of, and later a separate company spun off from, aircraft manufacturer Saab in Linköping, Sweden. Its history dates back to December 1954, when Saab got a license to build its own copy of BESK, an early Swedish c ...

, which he mastered, allowing him to demand and receive flexible working hours. That gave him enough time to focus on philosophy, to which he was mainly introduced by

Jan Patočka

Jan Patočka (; 1 June 1907 – 13 March 1977) was a Czech philosopher. Having studied in Prague, Paris, Berlin, and Freiburg, he was one of the last pupils of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. In Freiburg he also developed a lifelong philos ...

. From autumn 1968 Chavtik attended Patočka’s lectures at the

Faculty of Arts of Charles University, and a year later he became Patočka’s external research candidate. When Patočka was forced to leave the faculty in 1972. After Patočka’s death in March 1977, he and his friends saved the philosophers writings, which they gradually worked on releasing in samizdat. They managed to publish 27 volumes in blue binding, now called the Archival Series of Jan Patočka’s Works, before the

Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution ( cs, Sametová revoluce) or Gentle Revolution ( sk, Nežná revolúcia) was a non-violent transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring from 17 November to 28 November 1989. Popular demonstrations agains ...

.

Twentieth - Hans-Dietrich Genscher and Markus Meckel

Born on 21 March 1927,

Hans-Dietrich Genscher

Hans-Dietrich Genscher (21 March 1927 – 31 March 2016) was a German statesman and a member of the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP), who served as Federal Minister of the Interior from 1969 to 1974, and as Federal Minister for Foreign Affa ...

was a German politician of the liberal

Free Democratic Party (FDP). He served as Foreign Minister and Vice Chancellor of Germany from 1974 to 1992, making him the longest-tenured holder of either post. Amongst many of his achievements, he is greatly respected for his significant efforts that helped spell the end of the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

in the late 1980s, when Communist eastern European governments toppled leading to

German reunification

German reunification (german: link=no, Deutsche Wiedervereinigung) was the process of re-establishing Germany as a united and fully sovereign state, which took place between 2 May 1989 and 15 March 1991. The day of 3 October 1990 when the Ge ...

. During his time in office, he focused on maintaining stability and balance between the West and the Soviet bloc. From the beginning, he argued that the West should seek cooperation with Communist governments rather than treat them as implacably hostile. In 1991, he played a pivotal role in international diplomacy surrounding the breakup of

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

by successfully pushing for international recognition of

Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = " Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capi ...

,

Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, and ...

and other republics declaring independence. After leaving office, he worked as a lawyer and international consultant. Genscher passed away at his home outside

Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ru ...

in Wachtberg on 31 March 2016, one week and three days after his 89th birthday. The HRE Award will be received by his widow Barbara Genscher.

Markus Meckel

Markus Meckel (born 18 August 1952) is a German theologian and politician. He was the penultimate foreign minister of the GDR and a member of the German Bundestag.

Early life

Markus Meckel was born on 18 August 1952 in Müncheberg, Brandenburg ...

is a theologian and politician who was involved with the opposition in the

German Democratic Republic (GDR) from the 1970s. During the last phase of the East-German state, he co-founded the

Social Democratic Party in the GDR

The Social Democratic Party in the GDR (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei in der DDR) was a reconstituted Social Democratic Party existing during the final phase of East Germany. Slightly less than a year after its creation it merged with its Wes ...

, which later transformed into the

Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been ...

, one of the two major parties in the country today. Just before the dissolution of the

GDR, he became its first democratically elected Foreign Minister. As member of the

German Bundestag

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

(1990-2009), he focused on European politics, security issues and

Eastern Partnership

The Eastern Partnership (EaP) is a joint initiative of the European External Action Service of the European Union (EU) together with the EU, its member states, and six Eastern European partners governing the EU's relationship with the post-Sovi ...

. He was Vice-Spokesman of the Social Democrats for foreign policy and Spokesman in two commissions dealing with the SED dictatorship and its consequences. Serving as President of the

German War Graves Commission

The German War Graves Commission ( in German) is responsible for the maintenance and upkeep of German war graves in Europe and North Africa. Its objectives are acquisition, maintenance and care of German war graves; tending to next of kin; youth ...

from 2013 to 2016, he has been an advocate for the remembrance of the casualties of war by conserving cemeteries and organizing international work camps for young people. Currently Mr. Meckel is chairman of the

Council of the Federal Foundation for the Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship, co-chairman of the Council of the Foundation for German-Polish Cooperation and member of the Advisory Board of

European Network Remembrance and Solidarity European Network Remembrance and Solidarity (ENRS) was created in 2005 as a joint initiative by German, Hungarian, Polish, and Slovak ministers of culture. In 2014 Romania joined the structure.

The purpose of the ENRS is to document and promo ...

.

References

{{Reflist

External links

* http://praguesociety.org/hanno-r-ellenbogen-citizenship-award/

Hanno R. Ellenboen Citizenship Award Page on Praguesociety.orgMilinkevich surrenders Hanno R. Ellenbogen Citizenship Award in favor of Pavel SevyarynetsMilos Forman fifth winner of Hanno R.Ellenbogen awardPrague Society for International Cooperation establishes Hanno R. Ellenbogen AwardAlbright to be granted Hanno R. Ellenbogen Citizenship AwardPrague Society honours former NATO Secretary General Lord Robertson - 09-12-2004 - Radio PragueWriter recalls Chechan warHavel Receives Ellenbogen Citizenship Award

* ttp://ajp.cuni.cz/index.php/Home The Jan Patočka Archive in Praguebr>

*https://www.memoryofnations.eu/en/chvatik-ivan-1941

*https://apnews.com/article/9af1460a1abf427eb9e3a983607046ee

Czech awards

Awards established in 2000

2000 establishments in the Czech Republic

The Hanno R. Ellenbogen Citizenship Award is given annually to honor individuals who have dedicated their lives to public service. It was established in 2000 by the

The Hanno R. Ellenbogen Citizenship Award is given annually to honor individuals who have dedicated their lives to public service. It was established in 2000 by the  Maestro

Maestro

Madeleine Albright donated financial part to Petra Procházková, a Czech journalist and humanitarian worker. She is best known as a war correspondent to the conflict areas of the

Madeleine Albright donated financial part to Petra Procházková, a Czech journalist and humanitarian worker. She is best known as a war correspondent to the conflict areas of the

Lord Robertson, born on the

Lord Robertson, born on the

His Majesty King

His Majesty King

The 14th Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso, is both the head of state and the spiritual leader of

The 14th Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso, is both the head of state and the spiritual leader of

As one of Czechoslovakia's most respected foreign correspondents,

As one of Czechoslovakia's most respected foreign correspondents,

'

'

Magda Vášáryová born August 26 - of mixed German, Hungarian and Slovak origins - is known for being one of Czechoslovakia's great actresses. Vaclav Havel wanted her to become the Vice President of democratic Czechoslovakia after 1989 - but she declined. In 1999, she became the first female presidential candidate in

Magda Vášáryová born August 26 - of mixed German, Hungarian and Slovak origins - is known for being one of Czechoslovakia's great actresses. Vaclav Havel wanted her to become the Vice President of democratic Czechoslovakia after 1989 - but she declined. In 1999, she became the first female presidential candidate in

Th

Th Financial Part Donated to Caritas Bakhita House

Cardinal Vincent Nicols intends to donate the money from the award to Caritas Bakhita House in the Diocese of Westminster for their work to help victims of trafficking get back on their feet, whether they wish to return home or find suitability in this country.

Financial Part Donated to Caritas Bakhita House

Cardinal Vincent Nicols intends to donate the money from the award to Caritas Bakhita House in the Diocese of Westminster for their work to help victims of trafficking get back on their feet, whether they wish to return home or find suitability in this country.