Erich Mühsam on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Erich Mühsam (6 April 1878 – 10 July 1934) was a German-Jewish

My hatred grows when I look back on it and visualise the unspeakable flailings which were supposed to beat out of me all my innate feelings."Erich Mühsam, ''Tagebücher: 1910–1924'' (trans. ''Diaries'') (Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1994)

Mühsam moved to Berlin in 1900, where he soon became involved in a group called ' (New Society) under the direction of

Mühsam moved to Berlin in 1900, where he soon became involved in a group called ' (New Society) under the direction of

When Erich Mühsam was released on 3 November 1918, he returned to

When Erich Mühsam was released on 3 November 1918, he returned to

An official Nazi report dated 11 July stated that Erich Mühsam committed suicide, hanging himself while in "protective custody" at Oranienburg. However, a report from

An official Nazi report dated 11 July stated that Erich Mühsam committed suicide, hanging himself while in "protective custody" at Oranienburg. However, a report from

Die Erich Mühsam Seite

(trans. The Erich Mühsam Site) — a selection of poems by Mühsam

at Daily Bleed's Anarchist Encyclopedia

Complete German texts of selected works by Mühsam

Guide to the Erich Muehsam Collection

Archival materials by and about Mühsam at the Leo Baeck Institute, New York

The Revolutioner

- English translation of poem "Der Revoluzzer" by Erich Mühsam * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Muhsam, Erich 1878 births 1934 deaths 20th-century German dramatists and playwrights 20th-century German poets Anarchist writers Bavarian Soviet Republic Jewish cabaret performers German anarchists German Jews who died in the Holocaust German male dramatists and playwrights German male journalists German male non-fiction writers German male poets German people who died in Nazi concentration camps German socialists Jewish anarchists Jewish anti-fascists Jewish German writers Jewish poets Jewish socialists Murdered anarchists People from Berlin executed in Nazi concentration camps People from the Province of Brandenburg People of the German Revolution of 1918–1919 People of the Weimar Republic Weimar culture Writers from Lübeck

antimilitarist

Antimilitarism (also spelt anti-militarism) is a doctrine that opposes war, relying heavily on a critical theory of imperialism and was an explicit goal of the First and Second International. Whereas pacifism is the doctrine that disputes (esp ...

anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessar ...

essay

An essay is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a letter, a paper, an article, a pamphlet, and a short story. Essays have been sub-classified as formal a ...

ist, poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral or w ...

and playwright

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays.

Etymology

The word "play" is from Middle English pleye, from Old English plæġ, pleġa, plæġa ("play, exercise; sport, game; drama, applause"). The word "wright" is an archaic English ...

. He emerged at the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

as one of the leading agitators for a federated Bavarian Soviet Republic, for which he served 5 years in prison.

Also a cabaret

Cabaret is a form of theatrical entertainment featuring music, song, dance, recitation, or drama. The performance venue might be a pub, a casino, a hotel, a restaurant, or a nightclub with a stage for performances. The audience, often dinin ...

performer, he achieved international prominence during the years of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

for works which, before Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

came to power in 1933, condemned Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

and satirized the future dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in time ...

. Mühsam was tortured and murdered in the Oranienburg concentration camp in 1934.

Biography

Early life: 1878–1900

The third child born to Siegfried Seligmann Mühsam, amiddle-class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Com ...

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

pharmacist

A pharmacist, also known as a chemist (Commonwealth English) or a druggist (North American and, archaically, Commonwealth English), is a healthcare professional who prepares, controls and distributes medicines and provides advice and instructi ...

, Erich Mühsam was born in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

on 6 April 1878. Soon after, the family moved to the city of Lübeck.

Mühsam was educated at the Katharineum- Gymnasium in Lübeck, a school known for its authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic vot ...

discipline and corporal punishment, which served as the model for several of the settings in Thomas Mann's novel '' Buddenbrooks'' (1901). The young student Erich, who was by nature rebellious and resisted the school's regimented programme, was often physically punished. It was in the spirit of this resistance that, in January 1896, Mühsam authored an anonymous submission to the ''Lübecker Volksboten'', denouncing one of the school's more unpleasant teachers, which caused a scandal. When his identity became known, Mühsam was expelled from the Katharineum-Gymnasium for sympathising and participating in socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

activities. He completed his education in Parchim.

From an early age, Mühsam displayed a talent for writing and desired to become a poet — a career aspiration his father sought to beat out of him.-- His juvenilia

Juvenilia are literary, musical or artistic works produced by authors during their youth. Written juvenilia, if published at all, usually appears as a retrospective publication, some time after the author has become well known for later works.

...

consisted of animal fables, and he was first published at the age of 16, earning small amounts of money for satirical poems based on local news and political happenings. However, at the insistence of his father, young Erich set out to study pharmacy

Pharmacy is the science and practice of discovering, producing, preparing, dispensing, reviewing and monitoring medications, aiming to ensure the safe, effective, and affordable use of medication, medicines. It is a miscellaneous science as it ...

, a profession which he quickly abandoned to return to his poetic and literary ambitions. Mühsam left Lübeck for Berlin to pursue a literary career, later writing of his youth that "Poet, writer and anarchist: 1900–1918

Mühsam moved to Berlin in 1900, where he soon became involved in a group called ' (New Society) under the direction of

Mühsam moved to Berlin in 1900, where he soon became involved in a group called ' (New Society) under the direction of Julius

The gens Julia (''gēns Iūlia'', ) was one of the most prominent patrician families in ancient Rome. Members of the gens attained the highest dignities of the state in the earliest times of the Republic. The first of the family to obtain the ...

and Heinrich Hart which combined socialist philosophy with theology and communal living in the hopes of becoming "a forerunner of a socially united great working commune of humanity." Within this group, Mühsam became acquainted with Gustav Landauer who encouraged his artistic growth and compelled the young Mühsam to develop his own activism based on a combination of communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

and anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessar ...

political philosophy that Landauer introduced to him. Desiring more political involvement, in 1904, Mühsam withdrew from ''Neue Gemeinschaft'' and relocated temporarily to an artists commune in Ascona

300px, Ascona

Ascona ( lmo, label= Ticinese, Scona ) is a municipality in the district of Locarno in the canton of Ticino in Switzerland.

It is located on the shore of Lake Maggiore.

The town is a popular tourist destination and holds the yea ...

, Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

where vegetarianism was mixed with communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

and socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

. It was here that he began writing plays, the first ''Die Hochstapler'' (''The Con Men''), juxtaposing new modern

Modern may refer to:

History

*Modern history

** Early Modern period

** Late Modern period

*** 18th century

*** 19th century

*** 20th century

** Contemporary history

* Moderns, a faction of Freemasonry that existed in the 18th century

Philosophy ...

political theory within traditional dramatic forms, which became a typical trademark of his dramatic work. During these years, Mühsam began contributing to and editing several anarchist journals. These writings made Mühsam the target of constant police surveillance and arrests as he was considered among the most dangerous anarchist agitators in Germany. The press seized the opportunity to portray him as a villain accused of anarchist conspiracies and petty crimes.

In 1908, Mühsam relocated to Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

, where he became heavily involved in cabaret

Cabaret is a form of theatrical entertainment featuring music, song, dance, recitation, or drama. The performance venue might be a pub, a casino, a hotel, a restaurant, or a nightclub with a stage for performances. The audience, often dinin ...

. While Mühsam did not particularly care for his work in writing cabaret songs, it would become among his most famous creations.

In 1911, Mühsam founded the newspaper, ''Kain'' (''Cain''), as a forum for anarcho-communist ideologies, stating that it would "be a personal organ for whatever the editor, as a poet, as a citizen of the world, and as a fellow man had on his mind." Mühsam used ''Kain'' to ridicule the German state and what he perceived as excesses and abuses of authority, standing out in favour of abolishing capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

, and opposing the government's attempt at censoring theatre, and offering prophetic and perceptive analysis of international affairs. For the duration of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, publication was suspended to avoid government-imposed censorship often enforced against private newspapers that disagreed with the imperial government and the war.

Mühsam married Kreszentia Elfinger (nickname Zenzl), the widowed daughter of a Bavarian farmer, in 1915.

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

would see the international anarchist community starkly divided into pro-war and anti-war positions, some hyper-nationalistically supporting Germany, others desiring that Germany's enemies (the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, and later the United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

) would be victorious. Mühsam became extremely nationalistic and militant in his support of Germany in the war, writing in his diaries: "And I the anarchist, the anti-militarist, the enemy of national slogans, the anti-patriot and implacable critic of the armament furies, I discovered myself somehow possessed by the common intoxication, fired by an irate passion." His public support of the war was seized upon by the state-controlled press for the purposes of propaganda, and by fellow anarchists who felt betrayed. However, by the end of 1914, Mühsam, pressured by his anarchist acquaintances renounced his support of the war effort, stating that "I will probably have to bear the sin of betraying my ideals for the rest of my life" and appealing, "Those who comfortably acquiesce and say 'we cannot change things' shamefully desecrate human dignity and all the gifts of their own hearts and brain. For they renounce without a struggle every use of their ability to overthrow man-made institutions and governments and to replace them with new ones." For the rest of the war, Mühsam opposed the war through increased involvement in many direct action projects, including workers strikes, often collaborating with figures from other leftist political parties. As the strikes became increasingly successful and violent, the Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

n state government began mass arrests of anti-war agitators. Mühsam was among those arrested and incarcerated in April 1918. He would be detained until just before the war's end in November 1918.

Weimar years: 1918–1933

When Erich Mühsam was released on 3 November 1918, he returned to

When Erich Mühsam was released on 3 November 1918, he returned to Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

. Within days, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany abdicated as did King Ludwig III who had semi-autonomous rule in Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

, and Munich was in the throes of revolt. Kurt Eisner of the Independent Socialist Party declared Bavaria a socialist republic during the Red Bavaria Revolution. Eisner, in a gesture designed to bring the anarchists into the new government, offered a ministry position to Mühsam, who refused, preferring to fight along with Gustav Landauer, Ernst Toller, Ret Marut and other anarchists for the development of Worker's Councils (Soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in ...

) and communes.

However, after Eisner's assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

in 1919, the Bayerische Räterepublik (Bavarian Soviet Republic) was proclaimed, ruled by independent socialist Ernst Toller and anarchists Gustav Landauer and Erich Mühsam. This government was short-lived, lasting six days, being overthrown by communists led by Eugen Levine. However, during this time, the Bavarian Soviet Republic declared war on Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

. When the Weimar Republic's Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, rega ...

, a right-wing army commanded by Gustav Noske, crushed the rebellion and took possession of Munich, Gustav Landauer was killed and Mühsam arrested and sentenced to fifteen years in jail.

While in jail, Mühsam was very prolific with his writing, completing the play ''Judas'' (1920), and a large number of poems. In 1924, he was released from jail as the Weimar Republic granted a general amnesty for political prisoners. Also released in this amnesty was Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

, who had served eight months of a five-year sentence for leading the Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party ( or NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and othe ...

in 1923.

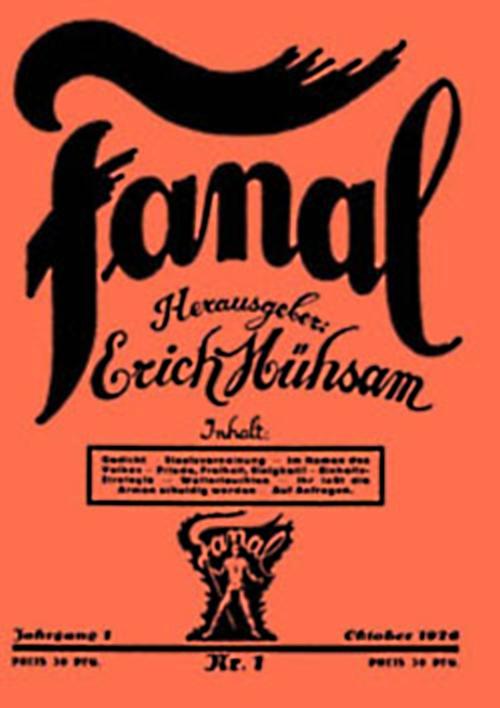

The Munich to which Mühsam returned was very different from the one he left after his arrest. The people were largely apathetic, in part because of the economic collapse of Germany under the pressure of reparations for World War I and hyperinflation. He had attempted to restart the journal ''Kain'' which failed after a few issues. In 1926, Mühsam founded a new journal which he called ''Fanal'' (''The Torch''), in which he openly and precariously criticized the communists and the far Right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this pos ...

conservative elements within the Weimar Republic. During these years, his writings and speeches took on a violent, revolutionary tone, and his active attempts to organize a united front to oppose the radical Right provoked intense hatred from conservatives and nationalists within the Republic.

Mühsam specifically targeted his writings to satirize the growing phenomenon of Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

, which later raised the ire of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

and Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the '' Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to ...

. ''Die Affenschande'' (1923), a short story, ridiculed the racial doctrines of the Nazi party, while the poem ''Republikanische Nationalhymne'' (1924) attacked the German judiciary for its disproportionate punishment of leftists while barely punishing the right wing participants in the Putsch.

In 1928, Erwin Piscator

Erwin Friedrich Maximilian Piscator (17 December 1893 – 30 March 1966) was a German theatre director and producer. Along with Bertolt Brecht, he was the foremost exponent of epic theatre, a form that emphasizes the socio-political content o ...

produced Mühsam's third play, ''Staatsräson'' (''For reasons of State''), based upon the controversial conviction and execution of Nicola Sacco

Nicola Sacco (; April 22, 1891 – August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (; June 11, 1888 – August 23, 1927) were Italian immigrant anarchists who were controversially accused of murdering Alessandro Berardelli and Frederick Parmenter, a ...

and Bartolomeo Vanzetti

Nicola Sacco (; April 22, 1891 – August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (; June 11, 1888 – August 23, 1927) were Italian immigrant anarchists who were controversially accused of murdering Alessandro Berardelli and Frederick Parmenter, a ...

in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

.

In 1930, Mühsam completed his last play ''Alle Wetter'' (''All Hang''), which sought mass revolution as the only way to prevent a radical Right-wing seizure of power. This play, never performed in public, was directed exclusively at criticizing the Nazis who were on the rise politically in Germany.

Arrest and death

Mühsam was arrested on charges unknown in the early morning hours of 28 February 1933, within a few hours after the Reichstag fire in Berlin.Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the '' Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to ...

, the Nazi propaganda minister, labelled him as one of "those Jewish subversives." It is alleged that Mühsam was planning to flee to Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

within the next day. Over the next seventeen months, he would be imprisoned in the concentration camps at Sonnenburg, Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 squ ...

and finally, Oranienburg.

Marinus van der Lubbe, an alleged Communist agitator, was arrested and blamed for the fire, and his association with Communist organizations led Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

to declare a state of emergency, encouraging aging president Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

to sign the Reichstag Fire Decree, abolishing most of the human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

provisions of the Weimar Republic's constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

(1919). Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

used the state of emergency to justify the arrests of large numbers of German intellectuals labelled as communists, socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the econ ...

, and anarchists in both retaliation for the attack and to silence opposition for his increasing suppression of civil liberties.

After breaking his teeth with musket blows; stamping a swastika on his scalp with a red-hot brand; subjecting him to tortures which caused him to be taken into a hospital, even now the fascist hyenas of the Sonninburg concentration camp continue their beastly attacks upon this defenseless man. The last news are really atrocious: the Nazi forced our comrade to dig his own grave and then with a simulated execution made him go through the agony of a doomed man. Although his body has been reduced to a mass of bleeding and tumefied flesh, his spirit is still very high: when his traducers tried to force him to sing the Horst-Wessel-Lied (the Nazi's anthem) he defied their anger by singing the Internationale.On 2 February 1934, Mühsam was transferred. The beatings and torture continued, until finally on the night of 9 July 1934, Mühsam was tortured and murdered by the guards, his battered corpse found hanging in a latrine the next morning.

An official Nazi report dated 11 July stated that Erich Mühsam committed suicide, hanging himself while in "protective custody" at Oranienburg. However, a report from

An official Nazi report dated 11 July stated that Erich Mühsam committed suicide, hanging himself while in "protective custody" at Oranienburg. However, a report from Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

on 20 July 1934 in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' stated otherwise

His widow declared this evening that, when she was first allowed to visit her husband after his arrest, his face was so swollen by beating that she could not recognise him. He was assigned to the task of cleaning toilets and staircases and Storm Troopers amused themselves by spitting in his face, she added. On 8 July she saw him for the last time alive. Despite the tortures he had undergone for fifteen months, she declared, he was cheerful, and she knew at once when his "suicide" was reported to her three days later that it was untrue. When she told the police that they had "murdered" him, she asserted they shrugged their shoulders and laughed. A post mortem examination was refused, according to Frau Mühsam, but Storm Troopers, incensed with their new commanders, showed her the body which bore unmistakable signs of strangulation, with the back of the skull shattered as if Herr Mühsam had been dragged across the parade ground.After the death, publications would accuse

Theodor Eicke

Theodor Eicke (17 October 1892 – 26 February 1943) was a senior SS functionary and Waffen SS divisional commander during the Nazi era. He was one of the key figures in the development of Nazi concentration camps. Eicke served as the sec ...

, the former commander of the concentration camp at Dachau, as the murderer, aided by two Sturmabteilung (Storm Troopers) officers identified as Ehrath and Konstantin Werner. It was alleged that he was tortured and beaten until he lost consciousness, followed by an injection that killed him, and that Mühsam's body was taken to a latrine in the rear of the building and hung on a rafter so as to create the impression that Mühsam had committed suicide.

Bibliography

Books

* ''Die Homosexualität. Ein Beitrag zur Sittengeschichte unserer Zeit'' (1903) * ''Räterepublik'' (1929) * ''Die Befreiung der Gesellschaft vom Staat'' (1932) * ''Unpolitische Erinnerungen'' (trans. ''Unpolitical Remembrances'') (1931) – an autobiography * ''Liberating Society from the State and Other Writings'' (2011) - comprehensive selection of Mühsam texts in English, edited and translated by Gabriel KuhnPlays

* ''Die Hochstapler'' (''The Con Men'') (1904) * ''Im Nachthemd durchs Leben'' (1914) * ''Die Freivermählten'' (1914) * ''Judas'' (1920) * ''Staatsräson'' (''Reasons of State'') (1928) * ''Alle Wetter'' (''All Hang'') (1930)Poetry

* ''Der wahre Jacob'' (1901) * ''Die Wüste'' (1904) * ''Der Revoluzzer'' (1908) * ''Der Krater'' (1909) * ''Wüste-Krater-Wolken'' (1914) * ''Brennende Erde'' (1920) * ''Republikanische Nationalhymne'' (1924) * ''Revolution. Kampf-, Marsch- und Spottlieder'' (1925)Journals and periodicals

* ''Kain: Zeitschrift für Menschlichkeit'' (''Cain: Magazine for Humanity'') 1911–1914, 1918–1919, 1924 (brief) * ''Fanal'' (''The Torch'') 1926–1933 * Contributed to anarchist journals ''Der Freie Arbeiter'' (''The Free Worker''), ''Der Weckruf'' (''The Alarm Call''), ''Der Anarchist'' (''The Anarchist''), ''Neue Gemeinschaft'' (''New Community'') and ''Kampf'' (''Struggle'') and edited ''Der Arme Teufel'' (''The Poor Devil'') under the pseudonym "Nolo."See also

*Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

* Weimar culture

References

Background information

* Lawrence Baron. ''The Eclectic Anarchism of Erich Mühsam''. New York: Revisionist Press, 1976. (Part of the series "Men and Movements in the History and Philosophy of Anarchism") * David Shepard. ''From Bohemia to the Barricades: Erich Mühsam and the Development of Revolutionary Drama''. (New York: Peter Lang, 1993). * Diana Köhnen. ''Das literarische Werk Erich Mühsams: Kritik und utopische Antizipation'' (The Literary Oeuvre of Erich Mühsam: Critique and Utopian Anticipation). Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 1988. * Rolf Kauffeldt. ''Erich Mühsam: Literatur und Anarchie'' (Erich Mühsam: Literature and Anarchy). Munich: W. Fink, 1983.External links

Die Erich Mühsam Seite

(trans. The Erich Mühsam Site) — a selection of poems by Mühsam

at Daily Bleed's Anarchist Encyclopedia

Complete German texts of selected works by Mühsam

Guide to the Erich Muehsam Collection

Archival materials by and about Mühsam at the Leo Baeck Institute, New York

The Revolutioner

- English translation of poem "Der Revoluzzer" by Erich Mühsam * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Muhsam, Erich 1878 births 1934 deaths 20th-century German dramatists and playwrights 20th-century German poets Anarchist writers Bavarian Soviet Republic Jewish cabaret performers German anarchists German Jews who died in the Holocaust German male dramatists and playwrights German male journalists German male non-fiction writers German male poets German people who died in Nazi concentration camps German socialists Jewish anarchists Jewish anti-fascists Jewish German writers Jewish poets Jewish socialists Murdered anarchists People from Berlin executed in Nazi concentration camps People from the Province of Brandenburg People of the German Revolution of 1918–1919 People of the Weimar Republic Weimar culture Writers from Lübeck