Epikleros on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An ''epikleros'' (; plural ''epikleroi'') was an heiress in ancient Athens and other ancient Greek city states, specifically a daughter of a man who had no sons. In

An ''epikleros'' (; plural ''epikleroi'') was an heiress in ancient Athens and other ancient Greek city states, specifically a daughter of a man who had no sons. In

A Glossary of Athenian Legal Terms

nbsp;– hosted by the Stoa Consortium at the

Women and Family in Athenian Law

nbsp;– hosted by the Stoa Consortium at the

Women and Property in Ancient Athens

nbsp;– by James C. Thompson

nbsp;– class notes by James P. Sickinger at

An ''epikleros'' (; plural ''epikleroi'') was an heiress in ancient Athens and other ancient Greek city states, specifically a daughter of a man who had no sons. In

An ''epikleros'' (; plural ''epikleroi'') was an heiress in ancient Athens and other ancient Greek city states, specifically a daughter of a man who had no sons. In Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

, they were called ''patrouchoi'' (), as they were in Gortyn

Gortyn, Gortys or Gortyna ( el, Γόρτυν, , or , ) is a municipality, and an archaeological site, on the Mediterranean island of Crete away from the island's capital, Heraklion. The seat of the municipality is the village Agioi Deka. Gorty ...

. Athenian women were not allowed to hold property in their own name; in order to keep her father's property in the family, an ''epikleros'' was required to marry her father's nearest male relative. Even if a woman was already married, evidence suggests that she was required to divorce her spouse to marry that relative. Spartan women were allowed to hold property in their own right, and so Spartan heiresses were subject to less restrictive rules. Evidence from other city-states is more fragmentary, mainly coming from the city-states of Gortyn and Rhegium

Reggio di Calabria ( scn, label= Southern Calabrian, Riggiu; el, label=Calabrian Greek, Ρήγι, Rìji), usually referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the largest city in Calabria. It has an estimated popul ...

.

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

wrote about ''epikleroi'' in his ''Laws'', offering idealized laws to govern their marriages. In mythology and history, a number of Greek women appear to have been ''epikleroi'', including Agariste of Sicyon Agariste (; grc, Ἀγαρίστη) (fl. 6th century BC, around 560 BC) was the daughter, and possibly the heiress, of the tyrant of Sicyon, Cleisthenes. Her father wanted to marry her to the "best of the Hellenes" and organized a competition whose ...

and Agiatis Agiatis ( grc, Ἀγιᾶτις) (died 224 BC), was a Spartan queen, married first to king Agis IV and secondly to king Cleomenes III of Sparta.

Life

She was the daughter of the rich Spartan citizen Gilippo.

Agiatis was described as a beautiful, ...

, the widow of the Spartan king Agis IV

Agis IV ( grc-gre, Ἄγις; c. 265 BC – 241 BC), the elder son of Eudamidas II, was the 25th king of the Eurypontid dynasty of Sparta. Posterity has reckoned him an idealistic but impractical monarch.

Family background and accession

A ...

. The status of ''epikleroi'' has often been used to explain the numbers of sons-in-law who inherited from their fathers-in-law in Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities o ...

. The Third Sacred War

The Third Sacred War (356–346 BC) was fought between the forces of the Delphic Amphictyonic League, principally represented by Thebes, and latterly by Philip II of Macedon, and the Phocians. The war was caused by a large fine imposed in ...

originated in a dispute over ''epikleroi''.

Etymology

The term ''epikleros'' (a feminine adjective acting as noun; from the proverb ὲπί, ''epí'', "on, upon", and the noun κλῆρος, ''klēros'', "lot, estate") was used inAncient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cu ...

to describe the daughter of a man who had died leaving no male heir. It translates to "attached to the family property",Grant ''Rise of the Greeks'' p. 31 or "upon, with the estate". In most ancient Greek city states, women could not own property, and so a system was devised to keep ownership within the male-defined family line. ''Epikleroi were required to marry the nearest relative on their father's side of the family, a system of inheritance known as the epiklerate.Pomeroy ''Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves'' pp. 60–62 Although ''epikleros'' is often mistranslated as "heiress",Cantarella "Gender, Sexuality, and Law" ''Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek Law'' pp. 248–249 strictly speaking the terms are not equivalent, as the woman never owned the property and so was unable to dispose of it.Lacey ''Family in Ancient Greece'' p. 24 Raphael Sealey

Raphael Sealey (14 August 1927, Middlesbrough, England – 29 November 2013, Berkeley, California) was a classical scholar and ancient historian.

Sealey studied at University College, Oxford in England under George Cawkwell, receiving an M.A. fr ...

argues that another translation could be "female orphan".Sealey ''Justice of the Greeks'' p. 17 The term was used interchangeably, both of the woman herself, and of the property that was the inherited estate.Gould "Law, Custom and Myth" ''Journal of Hellenic Studies'' p. 43 footnote 36 The entire system of the ''epiklerate'' was unique to Ancient Greece, and mainly an Athenian institution.

Athens

Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

is the city-state that is best documented, both in terms of ''epikleroi'' and in all aspects of legal history. Athenian law on ''epikleroi'' was attributed to Solon

Solon ( grc-gre, Σόλων; BC) was an Athenian statesman, constitutional lawmaker and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in Archaic Athens.Aristotle ''Politic ...

; women with no brothers had to marry their nearest male relative on their paternal

A father is the male parent of a child. Besides the paternal bonds of a father to his children, the father may have a parental, legal, and social relationship with the child that carries with it certain rights and obligations. An adoptive fathe ...

side of the family, starting with their father's brother and moving from there to the next nearest male relative on the paternal side.Grant ''Rise of the Greeks'' p. 49 The historian John Gould

John Gould (; 14 September 1804 – 3 February 1881) was an English ornithologist. He published a number of monographs on birds, illustrated by plates produced by his wife, Elizabeth Gould, and several other artists, including Edward Lear, ...

notes that the order of relatives that were required to marry the ''epikleros'' coincided with the relatives required to avenge a murder. This set of relatives was known as the '' anchisteia'' () in Athens.Gould "Law, Custom and Myth" ''Journal of Hellenic Studies'' pp. 43–44Schaps ''Economic Rights'' pp. 25–26 The ''anchisteia'' was also the group of relatives who would inherit property in the absence of legal heirs.Just ''Women in Athenian Law and Life'' p. 85 If there was more than one possible spouse in a set of relatives, the right to marry the ''epikleros'' went to the eldest one. The property that was inherited could also be in debt, which would not affect the ''epikleros status.

Definition of the term in Athens

Although ''epikleros'' was most often used in the case of a daughter who had no living brothers when her father died, the term was also used for other cases. The ''Suda

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; grc-x-medieval, Σοῦδα, Soûda; la, Suidae Lexicon) is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (Σούδας) or Souida ...

'', a 10th-century CE lexicon

A lexicon is the vocabulary of a language or branch of knowledge (such as nautical or medical). In linguistics, a lexicon is a language's inventory of lexemes. The word ''lexicon'' derives from Greek word (), neuter of () meaning 'of or fo ...

and encyclopedia,Browning "Suda" ''Oxford Classical Dictionary'' gives other definitions, including an heiress who was married at the time of her father's death and an unmarried daughter without brothers still living with her father. The ''Suda'' also stated that the term could be used of a daughter who had living sisters. Although the ''Suda'' indicates that in normal usage, the mother of the heiress was also dead, this is incorrect: whether or not the mother was alive had no bearing on the status of the ''epikleros''. Occasionally the term is also used as a feminine form of the Greek term ''orphanos'', or "orphan". Although a scholia

Scholia (singular scholium or scholion, from grc, σχόλιον, "comment, interpretation") are grammatical, critical, or explanatory comments – original or copied from prior commentaries – which are inserted in the margin of t ...

st of Aeschines

Aeschines (; Greek: , ''Aischínēs''; 389314 BC) was a Greek statesman and one of the ten Attic orators.

Biography

Although it is known he was born in Athens, the records regarding his parentage and early life are conflicting; but it seems ...

, or a later writer amending the text, stated that the term could also be used of a daughter who was given to a man in marriage on her father's deathbed, there is no extant use of the term in that sense in literature, and the scholiast has probably misunderstood a scenario from the comic playwright Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his ...

.

The term in Athens seems to have always been somewhat loosely used in legal proceedings. Apollodorus

Apollodorus (Greek: Ἀπολλόδωρος ''Apollodoros'') was a popular name in ancient Greece. It is the masculine gender of a noun compounded from Apollo, the deity, and doron, "gift"; that is, "Gift of Apollo." It may refer to:

:''Note: A f ...

, an Athenian politician and litigant from the 4th century BCE,Trevett "Apollodorus" ''Oxford Classical Dictionary'' in one of his speeches attempted to use an Athenian law about betrothal to make his mother an ''epikleros''. He claimed that the law defined an ''epikleros'' as a female without father, a brother who shared a father with her, or a paternal grandfather. His opponent, however, seems to have disputed this interpretation of the law. A speech by Isaeus Isaeus ( el, Ἰσαῖος ''Isaios''; fl. early 4th century BC) was one of the ten Attic orators according to the Alexandrian canon. He was a student of Isocrates in Athens, and later taught Demosthenes while working as a ''metic'' logographer (s ...

, a 4th-century BCE speechwriter,Davies "Isaeus" ''Oxford Classical Dictionary'' rests on the claim that the speaker's mother only became an ''epikleros'' after her young brother died following their father's death. Whether the legal authorities recognized the speaker's claim as valid is unknown. It appears, at least according to some plays, that a woman with a brother who died after their father was considered the ''epikleros'' of her brother, not her father.Macdowell "Love versus the Law" ''Greece & Rome'' p. 48

Development of the practice

It is unclear if there were laws dealing with ''epikleroi'' prior to Solon's legislative activity around 594 BCE. According to the 1st century CE writerPlutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, Solon authored legislation covering the ''epikleros''. Solon's laws attempted to prevent the combination of estates by the marriage of heiresses.Lacey ''Family in Classical Greece'' p. 89 Modern historians have seen this as part of an effort by Solon to maintain a stable number of households.Lape "Solon" ''Classical Journal'' p. 133 According to Plutarch, Solon also legislated that the husband of an ''epikleros'' must have sexual intercourse with her at least three times a month in order to provide her with children to inherit her father's property, but by the time of Pericles

Pericles (; grc-gre, Περικλῆς; c. 495 – 429 BC) was a Greek politician and general during the Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Athenian politics, particularly between the Greco-Persian Wars and the Pelo ...

(d. 429 BCE) this law is definitely attested.Schaps "What was Free?" ''Transactions of the American Philogical Association'' pp. 165–166 It is unclear whether or not the nearest relative had the power to dissolve an ''epikleros' '' previous marriage in order to marry her himself in all cases.Lacey ''Family in Ancient Greece'' pp. 139–145Carey "Apollodoros' Mother" ''Classical Quarterly'' p. 88 The historian Sarah Pomeroy states that most scholars lean towards the opinion that the nearest relative could only dissolve the previous marriage if the heiress had not yet given birth to a son, but Pomeroy also states that this opinion has not yet been definitely proven. Roger Just disagrees and has argued that even if the ''epikleros'' had a son she could still be forced to marry her nearest relative.Ormand "Marriage, Identity, and the Tale of Mestra" ''American Journal of Philology'' pp. 332–333 footnote 84 Athenian law also required that if the next of kin did not marry the heiress, he had to provide her with a dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment ...

. It may have been Solon who legislated that if the new spouse was unable to fulfill his thrice monthly duties to his wife, she was entitled to have sex with his next of kin so that she could produce an heir to her father's property. Alternatively, she might have been required to divorce and marry the next nearest relative.Carey "Shape of Athenian Laws" ''Classical Quarterly'' p. 104

Legal procedures

When a man died leaving an ''epikleros'', the heiress was felt to be ''epidikos'', or as it literally translates, "adjudicable". This made her available for the specialized procedure for thebetrothal

An engagement or betrothal is the period of time between the declaration of acceptance of a marriage proposal and the marriage itself (which is typically but not always commenced with a wedding). During this period, a couple is said to be ''fi ...

of an ''epikleros'', a type of court judgement called ''epidikasia''.Lacey ''Family in Classical Greece'' p. 106 The proceedings took place in the archon's court, for citizen ''epikleroi''. For the ''epikleroi'' of resident aliens in Athens, the ''metic

In ancient Greece, a metic (Ancient Greek: , : from , , indicating change, and , 'dwelling') was a foreign resident of Athens, one who did not have citizen rights in their Greek city-state (''polis'') of residence.

Origin

The history of foreign m ...

s'', the polemarch

A polemarch (, from , ''polemarchos'') was a senior military title in various ancient Greek city states (''poleis''). The title is derived from the words ''polemos'' (war) and ''archon'' (ruler, leader) and translates as "warleader" or "warlord" ...

was in charge of their affairs.Schaps ''Economic Rights'' pp. 33–35 It was also the case that if a man made a will, but did not give any of his daughters their legal rights as ''epikleroi'' in the will, then that will was held to be invalid.Lacey ''Family in Classical Greece'' p. 131 A young Athenian male, prior to coming of age and serving his time as an ''ephebe

''Ephebe'' (from the Greek ''ephebos'' ἔφηβος (plural: ''epheboi'' ἔφηβοι), anglicised as ephebe (plural: ephebes), or Latinate ''ephebus'' (plural: ''ephebi'') is the term for an adolescent male. In ancient Greek society and myth ...

'', or military trainee, was allowed to claim ''epikleroi'', the only legal right an ''ephebe'' was permitted in Aristotle's day, besides that of taking office as a priest in an hereditary priesthood.Patterson ''Family in Greek History'' p. 97 It is also unclear if a man who was eligible to marry an ''epikleros'' but was already married could keep his previous wife while also claiming the ''epikleros''. While all evidence points to the ancient Athenians being monogamous

Monogamy ( ) is a form of dyadic relationship in which an individual has only one partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time ( serial monogamy) — as compared to the various forms of non-monogamy (e.g., pol ...

, there are two speeches by Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; el, Δημοσθένης, translit=Dēmosthénēs; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual pr ...

implying that men did indeed have both a wife acquired through the normal betrothal procedure and another who was adjudicated to them through the ''epidikasia'' () procedure. The archon was also responsible for overseeing the treatment of ''epikleroi'', along with widows, orphans, widows who claimed to be pregnant and households that were empty.Roy "''Polis'' and ''Oikos'' in Classical Greece" ''Greece & Rome'' pp. 11–12

When sons of an ''epikleros'' came of age, they gained the ownership of the inheritance.Hodkinson "Land Tenure and Inheritance in Classical Sparta" ''Classical Quarterly'' p. 395 In Athens, this age was given in an extant law, and was two years past the age of puberty of the son. In Solon's laws, it appears that the eldest son of the ''epikleros'' was considered the heir of his maternal grandfather, with any further sons being considered part of their father's household. The son's inheritance of his maternal grandfather's property happened whether or not his father and mother were alive, unlike most other inheritances. And the son of an ''epikleros'' did not inherit anything from his father, and was named after his grandfather. The heir could further consolidate his position by being posthumously adopted by his maternal grandfather, but this was not required.Ashari "Laws of Inheritance" ''Historia: Zeitschrift'' pp. 16–17 By the 4th century BCE, legal practices had changed, and the son could also inherit from his father, as well as from his maternal grandfather. And if there was more than one son, they divided the estate passed by the ''epikleros'' between themselves. After the heir secured possession of his inheritance, the law specified that he was to support his mother. It is likely that the debts of the grandfather were also inherited along with any property.

Although the law did not rule on who exactly owned the property before the son took possession, it appears from other sources that it was not actually owned by the husband of the ''epikleros'', in contrast to the usual procedure in Athens where the husband owned any property of the wife and could do with it as he willed. A number of speeches imply that the property was considered to be owned by the ''epikleros'' herself, although she had little ability to dispose of it. The husband probably had day to day control of the property and administered it, but was responsible for the management to the ''epikleros' '' heirs when they came of age. The position of the husband of an ''epikleros'' was closest to that of an ''epitropos'', or the guardian of an orphan's property, who was likewise responsible to the orphan for his care of the property when the orphan came of age. Another parallel with the orphan was that an ''epikleros' '' property was exempt from liturgies

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

''(leitourgia)'', or the practice of requiring citizens to perform public tasks without compensation,Henrichs, et al "Liturgy" ''Oxford Classical Dictionary'' as was the orphan's.Schaps ''Economic Rights'' pp. 26–28

It may have been possible for the husband of an ''epikleros'' to allow the posthumous adoption of the son of an ''epikleros'' as the son of the ''epikleros' '' father. This would prevent the inheritance of the newly adopted son of any property from his natural father, but it had the advantage of preserving the adoptee's ''oikos

The ancient Greek word ''oikos'' (ancient Greek: , plural: ; English prefix: eco- for ecology and economics) refers to three related but distinct concepts: the family, the family's property, and the house. Its meaning shifts even within texts.

The ...

'', commonly translated as "household" but incorporating ideas of kinship and property also.Foxhall "Household, Greek" ''Oxford Classical Dictionary'' Although the preservation of the paternal ''oikos'' is usually felt to be the reason behind the whole practice of the ''epiklerate'', the historian David Schaps argues that in fact, this was not really the point of the practice. Instead, he argues, that it was the practice of adoption that allowed the preservation of an ''oikos''.Schaps ''Economic Rights'' pp. 32–33 Schaps feels that the reason the ''epiklerate'' evolved was to ensure that orphaned daughters were married.Schaps ''Economic Rights'' pp. 41–42 Other historians, including Sarah Pomeroy, feel that the children of an ''epikleros'' were considered to transmit the paternal grandfather's ''oikos''.Pomeroy ''Families in Classical and Hellenistic Greece'' p. 25 The historian Cynthia Patterson agrees, arguing that adoption may have seemed unnecessary, especially if the ''epikleros'' and her husband gave their son the name of the maternal grandfather. She argues that too much attention has been paid to the patrilineal aspects of the ''oikos'', and that there was probably less emphasis on this in actual Athenian practice and more on keeping a household together as a productive unit.Patterson ''Family in Greek History'' pp. 99–101

The historian Roger Just states the main principle of the ''epiklerate'' was that no man could become the guardian of the property without also becoming the husband of the ''epikleros''. Just uses this principle to claim that any man adopted by the father of an ''epikleros'' was required to marry the ''epikleros''. Just states that the forcible divorce and remarriage of an ''epikleros'' was based on this principle, arguing that if the father of the ''epikleros'' had not adopted the first husband, the husband was not really the heir. Just sees the development of the ''epiklerate'' as flowing from Solon's desire to keep the number of Athenian households constant. According to Just, before Solon's legislation, the ''epikleros'' was just treated as part of the property, but that Solon's reforms transformed the ''epikleros'' into a transmitter of the property and her son the automatic heir to her father's estate.Just ''Women in Athenian Law and Life'' pp. 95–98

Taking as a wife an ''epikleros'' who had little estate was considered a praiseworthy action, and was generally stressed in public speeches. Such an heiress was called an ''epikleros thessa''.Pomeroy ''Families in Classical and Hellenistic Greece'' p. 37 If the nearest male relative did not wish to marry an ''epikleros'' who belonged to the lowest income class in Athens, he was required to find her a husband and provide her with a dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment ...

on a graduated scale according to his own income class. This dowry was in addition to her own property and the requirement was designed to ensure that even poor heiresses found husbands.Macdowell "Love versus the Law" ''Greece & Rome'' p. 49 The law also did not stipulate what was to happen if the ''epikleros'' was still an infant or too young for consummation of the marriage when she was claimed.Scafuro ''Forensic Stage'' p. 288

Sequence of the ''anchisteia''

The first set of relatives that had claim to an ''epikleros'' were the paternal uncles and any heirs of the uncles. Next in line were any sons of the sisters of the father and any of their heirs. Third in line were the grandsons of the father's paternal uncles, and following them the grandsons of the paternal aunts of the father. After these paternal relatives were exhausted, then the half-brothers of the father by the same mother were in line, then sons of the maternal half-sisters of the father. Seventh in line were the grandsons of maternal uncles of the father and then grandsons of maternal aunts of the father.Patterson ''Family in Greek History'' p. 98 It appears that if there were two or more relatives that were related in the same degree, the eldest of the similarly-related relatives had priority in claiming the ''epikleros''.Macdowell "Love versus the Law" ''Greece & Rome'' p. 47Chances of becoming an ''epikleros''

Modern estimates of the odds of an Athenian woman becoming an ''epikleros'' say that roughly one out of seven fathers died without biological sons.Golden "''Donatus'' and Athenian Phratries" ''Classical Quarterly'' p. 10 However, Athenian law allowed for a man to adopt another male as a son in his will, so not all daughters without brothers would have become ''epikleroi''.Roy "''Polis'' and ''Oikos'' in Classical Athens" ''Greece & Rome'' p. 12 Most modern historians estimate that 20% of families would have had only daughters, and another 20% would have been childless.Patterson ''Family in Greek History'' p. 93 The modern historian Cynthia Patterson said of the ''epikleros'' that although "she was distinctive, she was not rare".Already married ''epikleroi''

Whether an ''epikleros'' who was married at the time of her father's death was required to divorce her current spouse and marry the ''anchisteia'' is unclear. Most modern historians have come to the conclusion that this was only required if the ''epikleros'' had not yet had a son that could inherit the grandfather's estate. The clearest evidence is from the Roman playwrightTerence

Publius Terentius Afer (; – ), better known in English as Terence (), was a Roman African playwright during the Roman Republic. His comedies were performed for the first time around 166–160 BC. Terentius Lucanus, a Roman senator, brought ...

, in his play '' Adelphoe'', which includes a plot element involving a claim that a girl is actually an ''epikleros''. Although the play was written in the 2nd century BCE, Terence adapted most of his plays from earlier Athenian comedies, which makes it slightly more reliable as a source. And common sense argues that if a son had already been born to an ''epikleros'', there was no need to parcel out the ''epikleros'' to a relative in order to provide a male heir to the grandfather's estate. Although the ''anchisteia'' had the right to marry the ''epikleros'', he was not required to do so, and could refuse the match or find another spouse for the heiress. It was also possible for the husband of an ''epikleros'', who was not her ''anchisteia'', to buy off the ''anchisteia'' in order to remain married to his wife. Such cases were alleged by the speaker of Isaeus' speech ''Isaeus 10'' as well as a character in Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, Μένανδρος ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His ...

's play ''Aspis

An aspis ( grc, ἀσπίς, plural ''aspides'', ), or porpax shield, sometimes mistakenly referred to as a hoplon ( el, ὅπλον) (a term actually referring to the whole equipment of a hoplite), was the heavy wooden shield used by the i ...

''.Schaps ''Economic Rights'' pp. 28–31

Other city-states

Evidence for other ancient city states is more scattered and fragmentary.Sparta

In ancientSparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

, women had extensive rights, including the right to inherit property and to manage their own and their spouse's property.Grant ''Rise of the Greeks'' p. 98Cartledge "Spartan Wives" ''Classical Quarterly'' pp. 97–99 The comparable term to ''epikleros'' in Sparta was ''patrouchoi'', occasionally rendered as ''patrouchos''.Patterson ''Family in Greek History'' p. 92 In Sparta the law of ''epikleros'' only applied to unmarried girls, and the Spartan kings were responsible for finding spouses for ''epikleroi'' who had not been betrothed before their father's death.Lacey ''Family in Classical Greece'' pp. 202–203 Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

, in his list of Spartan royal prerogatives, said: "The kings are the sole judges of these cases only: concerning an unmarried heiress, to whom it pertains to have er if her father has not bethrothed her",Quoted in Hodkinson "Land Tenure and Inheritance in Classical Sparta" ''Classical Quarterly'' p. 394 but the exact meaning of this statement is debated. Some historians have interpreted this to mean that the kings had the right to give the heiress to anyone they chose, but others have suggested that the kings merely had the right to bestow the heiress on the nearest male relative, or to arbitrate between competing claims.Hodkinson "Land Tenure and Inheritance in Classical Sparta" ''Classical Quarterly'' pp. 394–396 Another suggestion is that the king's choice was restricted to citizens who had no land.Ashari "Laws of Inheritance" ''Historia: Zeitschrift'' p. 18 The name given to these heiresses in Sparta was ''patroiouchoi'', which literally translates as "holders of the patrimony." They inherited the land themselves, and retained the right to dispose of their inherited property. There were no restrictions on who they might marry.Cartledge ''Spartans'' p. 169

By the 4th century BCE Aristotle records that there were no restrictions on whom an heiress might marry. If she was not married during her father's lifetime or by directions in her father's will, her nearest next-of-kin was allowed to marry her wherever he chose.Ashari "Laws of Inheritance" ''Historia: Zeitschrift'' p. 19

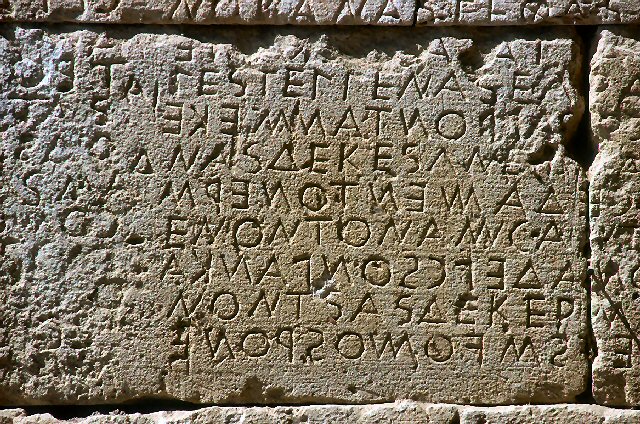

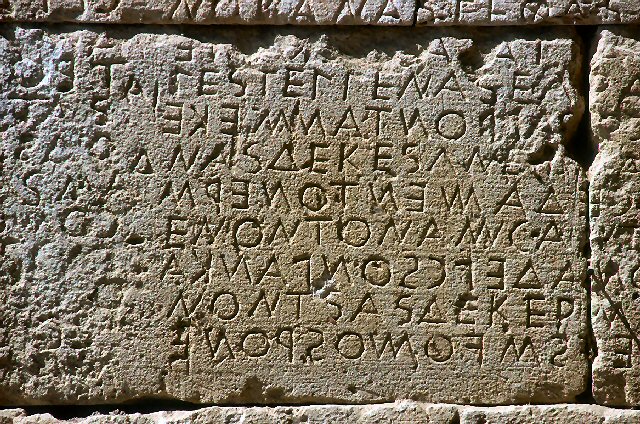

Gortyn

InGortyn

Gortyn, Gortys or Gortyna ( el, Γόρτυν, , or , ) is a municipality, and an archaeological site, on the Mediterranean island of Crete away from the island's capital, Heraklion. The seat of the municipality is the village Agioi Deka. Gorty ...

, ''epikleroi'' were also called ''patroiokos'', and they were more generously treated than in Athens.Pomeroy ''Families in Classical and Hellenistic Greece'' p. 53 footnote 87 The term ''patroiokos'' can be literally translated as "having the father's property", and was a description of the condition of the heiress. She was considered a ''patroiouchoi'' if she had no father or brother by her father living. The relative who had the right to marry her was called an ''epiballon'', and the list of who were eligible for that status was also limited to just her paternal uncles and the sons of those uncles. If there were no candidates fitting those conditions, the ''patroiouchoi'' was free to marry as she chose. If she wished, a ''patroiouchos'' could free herself from the obligation to marry her nearest relative by paying him part of her inheritance. If her nearest relative did not wish to marry her, she was free to find a spouse in her tribe, or if none was willing, then she could marry whomever she wished.Grant ''Rise of the Greeks'' p. 199Lacey ''Family in Classical Greece'' pp. 212–213 Gortyn may owe the liberality of its heiress laws to the fact that it was one of the few city-states known to have allowed daughters to inherit even if they had brothers; daughters in Gortyn received half the share of a son.Schaps "Women in Greek Inheritance Law" ''Classical Quarterly'' p. 55 To prevent the abuse of the system, there was a time limit on the right of the closest ''epiballon'' to marry her, and if the limit expired, the right passed to the next nearest ''epiballon'' until the ''patroiouchoi'' was either married or ran out of possible ''epiballontes''. There was a limit, however, that a man could only marry one heiress. Unlike in Athens, the heiress owned her inheritance and her son did not inherit until she died. Her son was also eligible to inherit from his father.

Others

Rhegium

Reggio di Calabria ( scn, label= Southern Calabrian, Riggiu; el, label=Calabrian Greek, Ρήγι, Rìji), usually referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the largest city in Calabria. It has an estimated popul ...

owed its laws on ''epikleroi'' to Androdamas of Rhegium, a law-giver whose views on this subject were especially esteemed, according to Aristotle.Grant ''Rise of the Greeks'' p. 260 In the city-state of Charondas

Charondas ( grc-gre, Χαρώνδας) was a celebrated lawgiver of Catania in Sicily. It is uncertain when he lived; some identify him as a pupil of Pythagoras (c. 580 – 504 BC), but all that can be said is that he lived earlier tha ...

' laws, an ''epikleros'' had to be given a dowry if her nearest kin did not wish to marry her.Lacey ''Family in Classical Greece'' p. 225 During the time of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, Tegea

Tegea (; el, Τεγέα) was a settlement in ancient Arcadia, and it is also a former municipality in Arcadia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the Tripoli municipality, of which it is a municipal un ...

n law deals with the inheritance of returning exiles, limiting them to inheriting only their paternal estate or an estate of their mother if she had become an ''epikleros'' while in exile. The city-states of Naupactus

Nafpaktos ( el, Ναύπακτος) is a town and a former municipality in Aetolia-Acarnania, West Greece, situated on a bay on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth, west of the mouth of the river Mornos.

It is named for Naupaktos (, Lati ...

and Thermus

''Thermus'' is a genus of thermophilic bacteria. It is one of several bacteria belonging to the '' Deinococcota'' phylum. ''Thermus'' species can be distinguished from other genera in the family ''Thermaceae'' as well as all other bacteria by ...

allowed women to inherit property, but whether or not the daughters were considered ''epikleroi'' is unknown from the surviving fragments of the laws from those cities.Schaps ''Economic Rights'' pp. 42–47

Plato

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, in his ''Laws

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vari ...

'', set forth rules that governed not the ideal state, which he described in '' The Republic'', but what he felt might be obtainable in the real world. Included amongst them were some dealing with inheritance and heiresses. In general outline, they conformed to Athenian practice, with the daughter of a man who died without male heirs becoming an ''epikleros''. Plato gave rules governing who the husband of the ''epikleros'' might be, and said that the inherited plot might not be divided or added to another plot. The main departure from Athenian law came if there was no direct heir, and the inheritance go to collateral relations. In that case, Plato assigned the inheritance not to one person, but to a pair, one male and one female, and ordered that they must marry and provide an heir to the estate, much like the ''epikleros''.Schaps "Women in Greek Inheritance Law" ''Classical Quarterly'' p. 56

Later history

In 318 BCE,Cassander

Cassander ( el, Κάσσανδρος ; c. 355 BC – 297 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia from 305 BC until 297 BC, and ''de facto'' ruler of southern Greece from 317 BC until his death.

A son of Antipater and a conte ...

appointed Demetrius Phalereus

Demetrius of Phalerum (also Demetrius of Phaleron or Demetrius Phalereus; grc-gre, Δημήτριος ὁ Φαληρεύς; c. 350 – c. 280 BC) was an Athenian orator originally from Phalerum, an ancient port of Athens. A student of Theophrast ...

to govern the city-state of Athens. Demetrius issued a set of laws that are known from later literary works. Although knowledge of these laws is fragmentary, it does not appear that Demetrius legislated anything on the subject of ''epikleroi''. This is in striking contrast to Solon's legislation, which was concerned with the internal affairs of the family and its external manifestations in public life.Patterson ''Family in Greek History'' pp. 188–191 By the 4th century BCE, the practice of the ''epiklerate'' was falling into disuse, and it disappeared during the Hellenistic Period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

, although it continued to appear in New Comedy

Ancient Greek comedy was one of the final three principal dramatic forms in the theatre of classical Greece (the others being tragedy and the satyr play). Athenian comedy is conventionally divided into three periods: Old Comedy, Middle Comedy, an ...

and scattered inscriptions from the 3rd century BCE, if dated correctly, refer to occasional ''epikleroi''.Scafuro ''Forensic Stage'' pp. 281–282 and footnote 2 One method that developed to avoid the ''epiklerate'' was through the adoption of a son by the father of a possible ''epikleros''.Sealey ''Justice of the Greeks'' p. 18

Noted ''epikleroi''

In mythology

In the tales of heroic Greece, royal succession often passed from father-in-law to son-in-law, and some historians have seen in this an early example of the ''epikleros'' pattern. Some examples includePelops

In Greek mythology, Pelops (; ) was king of Pisa in the Peloponnesus region (, lit. "Pelops' Island"). He was the son of Tantalus and the father of Atreus.

He was venerated at Olympia, where his cult developed into the founding myth of the O ...

, Bellerophon

Bellerophon (; Ancient Greek: Βελλεροφῶν) or Bellerophontes (), born as Hipponous, was a hero of Greek mythology. He was "the greatest hero and slayer of monsters, alongside Cadmus and Perseus, before the days of Heracles", and h ...

, Melampus

In Greek mythology, Melampus (; grc, Μελάμπους, ''Melampous'') was a legendary soothsayer and healer, originally of Pylos, who ruled at Argos. He was the introducer of the worship of Dionysus, according to Herodotus, who asserted tha ...

, Peleus

In Greek mythology, Peleus (; Ancient Greek: Πηλεύς ''Pēleus'') was a hero, king of Phthia, husband of Thetis and the father of their son Achilles. This myth was already known to the hearers of Homer in the late 8th century BC.

Bi ...

, Telamon

In Greek mythology, Telamon (; Ancient Greek: Τελαμών, ''Telamōn'' means "broad strap") was the son of King Aeacus of Aegina, and Endeïs, a mountain nymph. The elder brother of Peleus, Telamon sailed alongside Jason as one of his Argo ...

, and Diomedes

Diomedes (Jones, Daniel; Roach, Peter, James Hartman and Jane Setter, eds. ''Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary''. 17th edition. Cambridge UP, 2006.) or Diomede (; grc-gre, Διομήδης, Diomēdēs, "god-like cunning" or "advised by ...

. Not all such heroic era royal successions followed the ''epikleros'' pattern however, as in the case of Menelaus

In Greek mythology, Menelaus (; grc-gre, Μενέλαος , 'wrath of the people', ) was a king of Mycenaean (pre- Dorian) Sparta. According to the ''Iliad'', Menelaus was a central figure in the Trojan War, leading the Spartan contingent of ...

, who married Helen of Troy

Helen of Troy, Helen, Helena, (Ancient Greek: Ἑλένη ''Helénē'', ) also known as beautiful Helen, Helen of Argos, or Helen of Sparta, was a figure in Greek mythology said to have been the most beautiful woman in the world. She was believe ...

and succeeded Helen's father Tyndareus

In Greek mythology, Tyndareus (; Ancient Greek: Τυνδάρεος, ''Tundáreos''; Attic: Τυνδάρεως, ''Tundáreōs''; ) was a Spartan king.

Family

Tyndareus was the son of Oebalus (or Perieres) and Gorgophone (or Bateia). He married ...

, even though Tyndareus had living sons, Kastor and Polydeukes.Finkelberg "Royal Succession in Heroic Greece" ''Classical Quarterly'' p. 305 Another example is Arete

''Arete'' (Greek: ) is a concept in ancient Greek thought that, in its most basic sense, refers to 'excellence' of any kind Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. '' A Greek–English Lexicon'', 9th ed. (Oxford, 1940), s.v.br>—especially a person or thi ...

of Phaeacia

Scheria or Scherie (; grc, Σχερία or ), also known as Phaeacia () or Faiakia was a region in Greek mythology, first mentioned in Homer's '' Odyssey'' as the home of the Phaeacians and the last destination of Odysseus in his 10-year journ ...

in the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Iliad'', ...

'', who was an heiress married to her father's brother Alcinous

In Greek mythology, Alcinous (; Ancient Greek: Ἀλκίνους or Ἀλκίνοος ''Alkínoös'' means "mighty mind") was a son of Nausithous and brother of Rhexenor. After the latter's death, he married his brother's daughter Arete who ...

.Patterson ''Family in Greek History'' p. 91

Historical examples

Aristotle related that the revolt of Mytilene against Athens in 428 BCE originated in a dispute over ''epikleroi''. The Sacred War of 356–346, between Thebes andPhocis

Phocis ( el, Φωκίδα ; grc, Φωκίς) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the administrative region of Central Greece. It stretches from the western mountainsides of Parnassus on the east to the mountain range of Var ...

, was also started by a disagreement over ''epikleroi''.Lacey ''Family in Classical Greece'' pp. 229–230 It is likely that Agariste, the daughter of Cleisthenes of Sicyon

Cleisthenes ( ; grc-gre, Κλεισθένης) was the tyrant of Sicyon from c. 600–560 BC, who aided in the First Sacred War against Kirrha that destroyed that city in 595 BC. He was also said to have organized a successful war against Argos ...

who married Megacles

Megacles or Megakles ( grc, Μεγακλῆς) was the name of several notable men of ancient Athens, as well as an officer of Pyrrhus of Epirus.

First archon

The first Megacles was possibly a legendary archon of Athens from 922 BC to 892 BC.

A ...

of Athens, was an ''epikleros''.Lacey ''Family in Classical Greece'' p. 276 note 29 Likewise, the widow of the Spartan king Agis IV

Agis IV ( grc-gre, Ἄγις; c. 265 BC – 241 BC), the elder son of Eudamidas II, was the 25th king of the Eurypontid dynasty of Sparta. Posterity has reckoned him an idealistic but impractical monarch.

Family background and accession

A ...

, Agiatis, was forced to marry Cleomenes, the son of the man who had executed Agis, King Leonidas II

Leonidas II (; grc, Λεωνίδας Β΄, ''Leōnídas B, "Lion's son, Lion-like") was the 28th Agiad King of Sparta from 254 to 242 BC and from 241 to 235 BC.

Biography

Leonidas was the son of Cleonymus and grandson of king Cleomenes II (), ...

. Plutarch stated that the reason Leonidas married Agiatis to Kleomenes was that Agiatis was a ''patrouchos'' from her father, Gylippos.Hodkinson "Land Tenure and Inheritance in Classical Sparta" ''Classical Quarterly'' p. 398 Another Spartan example may have been Gorgo, the only daughter of King Cleomenes I

Cleomenes I (; Greek Κλεομένης; died c. 490 BC) was Agiad King of Sparta from c. 524 to c. 490 BC. One of the most important Spartan kings, Cleomenes was instrumental in organising the Greek resistance against the Persian Empire of Dariu ...

, who was married to Cleomenes' brother Leonidas I

Leonidas I (; grc-gre, Λεωνίδας; died 19 September 480 BC) was a king of the Greek city-state of Sparta, and the 17th of the Agiad line, a dynasty which claimed descent from the mythological demigod Heracles. Leonidas I was son of Kin ...

.

Kallisto, the granddaughter of the Athenian orator Lykourgos was an ''epikleros'' after the deaths of her grandfather, paternal uncles Habron and Lykourgos, and father Lykophron. She was married and had a son, whom her father adopted and renamed Lykophron. After her father's adoption of her son, Kallisto's husband, son and father all died, leaving her father's household in danger of extinction. Her second marriage, however, produced a son who continued the household.Blok and Lambert "Appointment of Priests" ''Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik'' pp. 102–103 Demosthenes' mother Cleoboule was the ''epikleros'' of Gylon

Gylon ( grc, Γύλων), also known as Gylon of Cerameis, was a Greek military official and the maternal grandfather of Demosthenes. He is known for his role in the capture and ultimately turning over of Nymphaeum to the Bosporans, for which he ...

.Hunter "Policing Public Debtors" ''Phoenix'' p. 30

Other possible ''epikleroi'' include the daughters of Polyeuctus, who managed to remain married to their spouses even after becoming ''epikleroi''. Meidylides' daughter was an heiress, and her father tried to marry her to her ''anchisteia'', but the prospective husband refused the match and the daughter was married to a non-relative instead.

Literary examples

In literature,Antigone

In Greek mythology, Antigone ( ; Ancient Greek: Ἀντιγόνη) is the daughter of Oedipus and either his mother Jocasta or, in another variation of the myth, Euryganeia. She is a sister of Polynices, Eteocles, and Ismene.Roman, L., ...

, the daughter of Oedipus

Oedipus (, ; grc-gre, Οἰδίπους "swollen foot") was a mythical Greek king of Thebes. A tragic hero in Greek mythology, Oedipus accidentally fulfilled a prophecy that he would end up killing his father and marrying his mother, thereby ...

, would be considered an ''epikleros'', and her uncle Creon would have been responsible for her marriage as well as that of her sister Ismene

In Greek mythology, Ismene (; grc, Ἰσμήνη, ''Ismēnē'') is the daughter and half-sister of Oedipus, daughter and granddaughter of Jocasta, and sister of Antigone, Eteocles, and Polynices. She appears in several plays of Sophocles: at ...

.Patterson ''Family in Greek History'' p. 113 The marriage of an ''epikleros'' also is part of the plot for Menander's play ''Aspis

An aspis ( grc, ἀσπίς, plural ''aspides'', ), or porpax shield, sometimes mistakenly referred to as a hoplon ( el, ὅπλον) (a term actually referring to the whole equipment of a hoplite), was the heavy wooden shield used by the i ...

''.Brown "Menander's Dramatic Technique" ''Classical Quarterly'' p. 413 In Euripides' play '' Ion'', Erechtheus

Erechtheus (; grc, Ἐρεχθεύς) in Greek mythology was the name of an archaic king of Athens, the founder of the ''polis'' and, in his role as god, attached to Poseidon, as "Poseidon Erechtheus". The mythic Erechtheus and the historical Ere ...

's daughter Creusa

In Greek mythology, Creusa (; grc, Κρέουσα ''Kreousa'' "princess") may refer to the following figures:

* Creusa, a naiad daughter of Gaia.

* Creusa, daughter of Erechtheus, King of Athens and his wife, Praxithea.

* Creusa, also known ...

is an ''epikleros'' whose status allows her son Ion to become a citizen of Athens.Hoffer "Violence, Culture, and the Workings of Ideology" ''Classical Antiquity'' p. 304 Alexis Alexis may refer to:

People Mononym

* Alexis (poet) ( – ), a Greek comic poet

* Alexis (sculptor), an ancient Greek artist who lived around the 3rd or 4th century BC

* Alexis (singer) (born 1968), German pop singer

* Alexis (comics) (1946–1977 ...

, Antiphanes, Diodorus, Diphilus

Diphilus ( Greek: Δίφιλος), of Sinope, was a poet of the new Attic comedy and a contemporary of Menander (342–291 BC). He is frequently listed together with Menander and Philemon, considered the three greatest poets of New Comedy. He w ...

, Euetes, and Heniokhos all wrote comedies titled ''Epikleros'', although none are extant.Scafuro ''Forensic Stage'' p. 293 and footnote 33 Three more comedies were titled ''Epidikazmenos'', or "the man to whom an estate is adjudged" - these were by Diphilus, Philemon and Apollodorus of Carystus Apollodorus of Carystus ( el, Ἀπολλόδωρος ὁ Καρύστιος) in Euboea, was one of the most important writers of the Attic New Comedy, who flourished in Athens between 300 and 260 B.C. He is to be distinguished from the older Apol ...

.Scafuro ''Forensic Stage'' p. 293 and footnote 32 Two Latin comedies survive which were based on Greek plays dealing with heiresses: the '' Phormio'', which is based on Apollodorus' ''Epidikazmenos''; and the ''Adelphoe'', which is based on Menander's play ''Adelphoi''.Scafuro ''Forensic Stage'' p. 294

A speech of Andocides

Andocides (; grc-gre, Ἀνδοκίδης, ''Andokides''; c. 440 – c. 390 BC) was a logographer (speech writer) in Ancient Greece. He was one of the ten Attic orators included in the "Alexandrian Canon" compiled by Aristophanes of Byzantium an ...

indirectly concerns ''epikleroi'', as the orator claimed that the real origin of the dispute between himself and his cousin Leagros was over which of them would claim an heiress that both were related to.Scafuro ''Forensic Stage'' pp. 69–71 Demosthenes' speech ''Against Macartatus'' includes a description of Sositheos' claiming of the ''epikleros'' Phulomakhe.Scafuro ''Forensic Stage'' pp. 285–286

See also

*Endogamy

Endogamy is the practice of marrying within a specific social group, religious denomination, caste, or ethnic group, rejecting those from others as unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relationships.

Endogamy is common in many cultu ...

*Exogamy

Exogamy is the social norm of marrying outside one's social group. The group defines the scope and extent of exogamy, and the rules and enforcement mechanisms that ensure its continuity. One form of exogamy is dual exogamy, in which two groups c ...

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

A Glossary of Athenian Legal Terms

nbsp;– hosted by the Stoa Consortium at the

University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky (UK, UKY, or U of K) is a public land-grant research university in Lexington, Kentucky. Founded in 1865 by John Bryan Bowman as the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Kentucky, the university is one of the state ...

Women and Family in Athenian Law

nbsp;– hosted by the Stoa Consortium at the

University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky (UK, UKY, or U of K) is a public land-grant research university in Lexington, Kentucky. Founded in 1865 by John Bryan Bowman as the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Kentucky, the university is one of the state ...

Women and Property in Ancient Athens

nbsp;– by James C. Thompson

nbsp;– class notes by James P. Sickinger at

Florida State University

Florida State University (FSU) is a public university, public research university in Tallahassee, Florida. It is a senior member of the State University System of Florida. Founded in 1851, it is located on the oldest continuous site of higher e ...

{{Authority control

Society of ancient Greece

Ancient Greek law

Ancient Athens