English devolution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the United Kingdom, devolution (historically called

In the United Kingdom, devolution (historically called

England is the only country of the United Kingdom to not have a devolved Parliament or Assembly and English affairs are decided by the UK Parliament.

England is the only country of the United Kingdom to not have a devolved Parliament or Assembly and English affairs are decided by the UK Parliament.

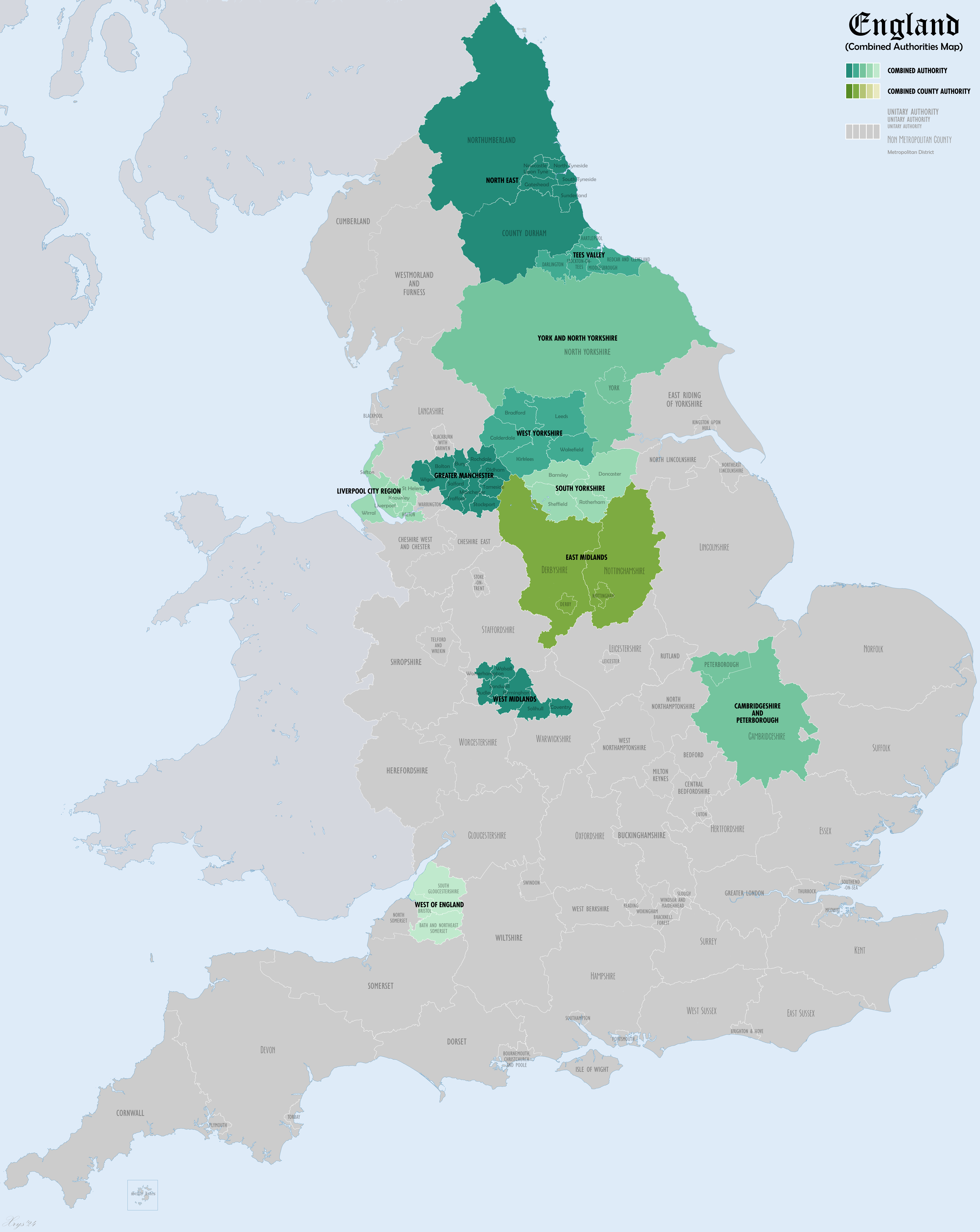

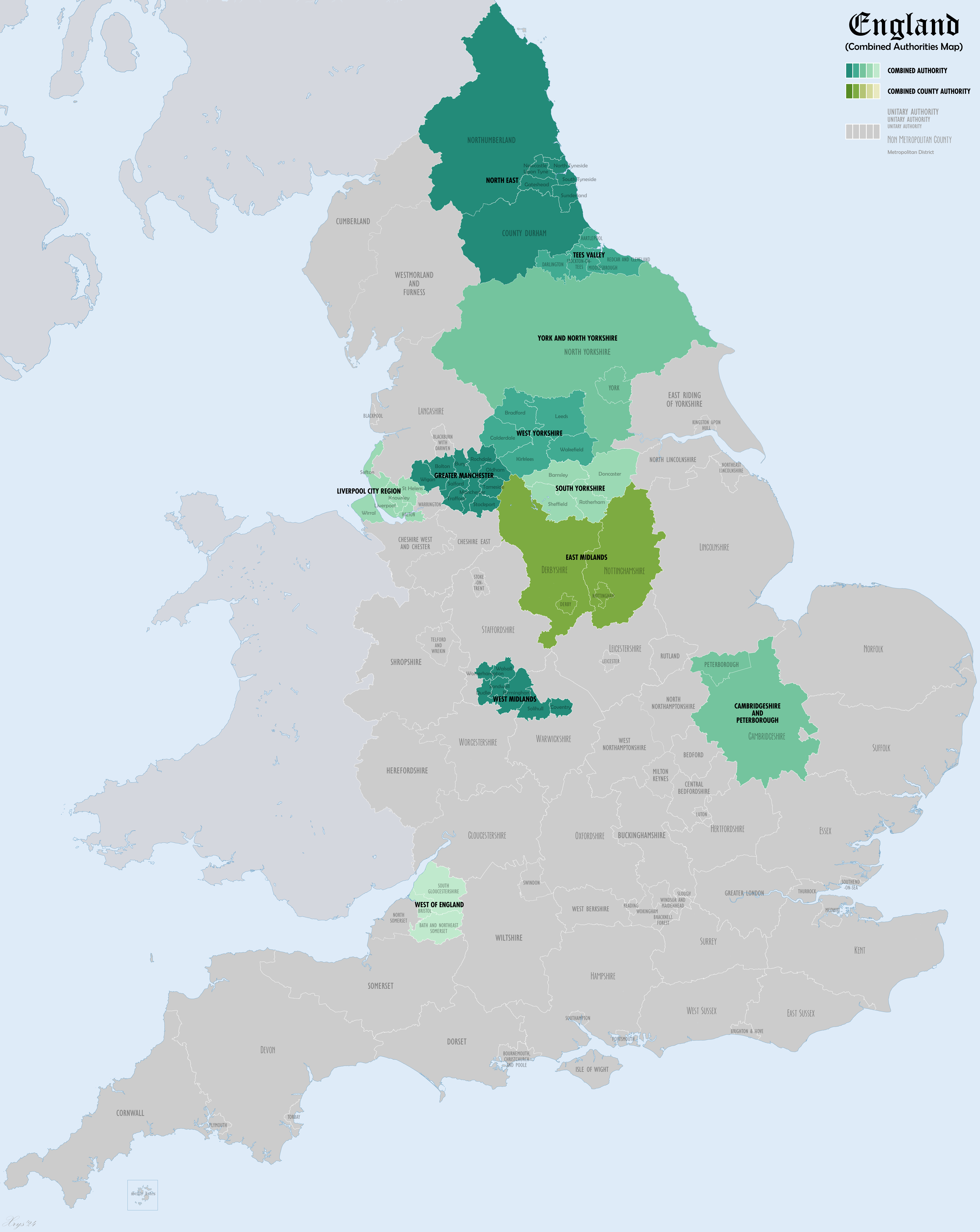

England has three distinct sub-national areas; the

England has three distinct sub-national areas; the

Devolution for England was proposed in 1912 by the Member of Parliament for Dundee,

Devolution for England was proposed in 1912 by the Member of Parliament for Dundee,

After the proposal of devolution to regions failed, the government pursued the concept of city regions. The 2009 Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act provided the means for the creation of

After the proposal of devolution to regions failed, the government pursued the concept of city regions. The 2009 Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act provided the means for the creation of

Cabinet Office: Devolution guidance

{{United Kingdom topics

home rule

Home rule is the government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governan ...

) is the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace ...

's statutory granting of a greater level of self-government

Self-governance, self-government, self-sovereignty or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any ...

to parts of the United Kingdom, such as to Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

and parts of England, specifically to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

and the combined authorities

A combined authority (CA) is a type of local government institution introduced in England outside Greater London by the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009. CAs are created voluntarily and allow a group of local aut ...

.

Statutory powers have been awarded to the Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament ( ; ) is the Devolution in the United Kingdom, devolved, unicameral legislature of Scotland. It is located in the Holyrood, Edinburgh, Holyrood area of Edinburgh, and is frequently referred to by the metonym 'Holyrood'. ...

, the Senedd

The Senedd ( ; ), officially known as the Welsh Parliament in English and () in Welsh, is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Wales. A democratically elected body, Its role is to scrutinise the Welsh Government and legislate on devolve ...

(Welsh Parliament), and the Northern Ireland Assembly

The Northern Ireland Assembly (; ), often referred to by the metonym ''Stormont'', is the devolved unicameral legislature of Northern Ireland. It has power to legislate in a wide range of areas that are not explicitly reserved to the Parliam ...

, with authority exercised by their associated executive bodies: the Scottish Government

The Scottish Government (, ) is the executive arm of the devolved government of Scotland. It was formed in 1999 as the Scottish Executive following the 1997 referendum on Scottish devolution, and is headquartered at St Andrew's House in ...

, Welsh Government

The Welsh Government ( ) is the Executive (government), executive arm of the Welsh devolution, devolved government of Wales. The government consists of Cabinet secretary, cabinet secretaries and Minister of State, ministers. It is led by the F ...

, and Northern Ireland Executive

The Northern Ireland Executive (Irish language, Irish: ''Feidhmeannas Thuaisceart Éireann'', Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster Scots: ''Norlin Airlan Executive'') is the devolution, devolved government of Northern Ireland, an administrative branc ...

respectively. While in England, oversight powers and general responsibility have also been given to the London Assembly

The London Assembly is a 25-member elected body, part of the Greater London Authority, that scrutinises the activities of the Mayor of London and has the power, with a two-thirds supermajority, to amend the Mayor's annual budget and to reject t ...

, which oversees the Greater London Authority

The Greater London Authority (GLA), colloquially known by the Metonymy, metonym City Hall, is the Devolution in the United Kingdom, devolved Regions of England, regional governance body of Greater London, England. It consists of two political ...

and Mayor of London

The mayor of London is the chief executive of the Greater London Authority. The role was created in 2000 after the Greater London devolution referendum in 1998, and was the first directly elected mayor in the United Kingdom.

The current ...

, and since 2011 various mayoral combined authorities throughout England. There have been further proposals for devolution in England, including national devolution, regional devolution (such as to northern England

Northern England, or the North of England, refers to the northern part of England and mainly corresponds to the Historic counties of England, historic counties of Cheshire, Cumberland, County Durham, Durham, Lancashire, Northumberland, Westmo ...

or Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

) or failed proposals for regional assemblies.

Devolution

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territori ...

differs from federalism

Federalism is a mode of government that combines a general level of government (a central or federal government) with a regional level of sub-unit governments (e.g., provinces, State (sub-national), states, Canton (administrative division), ca ...

in that the devolved powers of the subnational authority ultimately reside in central government, thus the state remains, ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

'', a unitary state

A unitary state is a (Sovereign state, sovereign) State (polity), state governed as a single entity in which the central government is the supreme authority. The central government may create or abolish administrative divisions (sub-national or ...

. Legislation creating devolved parliaments or assemblies can be repealed or amended by parliament in the same way as any statute. Although the parliaments and assemblies in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and London, as well as some mayors in England were supported via public referendums. Laws such as the Scotland Act 2016

The Scotland Act 2016 (c. 11) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It sets out amendments to the Scotland Act 1998 and devolves further powers to Scotland. The legislation is based on recommendations given by the report of the Smi ...

and Wales Act 2017

The Wales Act 2017 (c. 7) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It sets out amendments to the Government of Wales Act 2006 and devolves further powers to Wales. The legislation is based on the proposals of the St David's Day Comma ...

, affirmed the permanence of their devolved institutions, and any abolishment of such must be voted for in a referendum.

Legislation passed following the EU membership referendum, including the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020

The United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020 (c. 27) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed in December 2020. Its purpose is to prevent internal trade barriers within the UK, and to restrict the legislative powers of the d ...

, undermines and restricts the authority of the devolved legislatures in both Scotland and Wales.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland was the first constituent of the UK to have a devolved administration.Home Rule

Home rule is the government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governan ...

came into effect for Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

in 1921, under the Government of Ireland Act 1920

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 ( 10 & 11 Geo. 5. c. 67) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bi ...

("Fourth Home Rule Act"). The Parliament of Northern Ireland

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore ord ...

established under that act was prorogued (the session ended) on 30 March 1972 owing to the destabilisation of Northern Ireland upon the onset of the Troubles

The Troubles () were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted for about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it began in the late 1960s and is usually deemed t ...

in late 1960s. This followed escalating violence by state and paramilitary organisations following the suppression of civil rights demands by Northern Ireland Catholics.

The Northern Ireland Parliament

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore or ...

was abolished by the Northern Ireland Constitution Act 1973

The Northern Ireland Constitution Act 1973 (c. 36) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which received royal assent on 18 July 1973. The act abolished the suspended Parliament of Northern Ireland and the post of Governor and mad ...

, which received royal assent on 19 July 1973. A Northern Ireland Assembly

The Northern Ireland Assembly (; ), often referred to by the metonym ''Stormont'', is the devolved unicameral legislature of Northern Ireland. It has power to legislate in a wide range of areas that are not explicitly reserved to the Parliam ...

was elected on 28 June 1973 and following the Sunningdale Agreement

The Sunningdale Agreement was an attempt to establish a power-sharing Northern Ireland Executive and a cross-border Council of Ireland. The agreement was signed by the British and Irish government in Sunningdale, Berkshire, on 9 December 1 ...

, a power-sharing Northern Ireland Executive

The Northern Ireland Executive (Irish language, Irish: ''Feidhmeannas Thuaisceart Éireann'', Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster Scots: ''Norlin Airlan Executive'') is the devolution, devolved government of Northern Ireland, an administrative branc ...

was formed on 1 January 1974. This collapsed on 28 May 1974, due to the Ulster Workers' Council strike

The Ulster Workers' Council (UWC) strike was a general strike that took place in Northern Ireland between 15 May and 28 May 1974, during "the Troubles". The strike was called by Unionism in Ireland, unionists who were against the Sunningdale Ag ...

. The Troubles continued.

The Northern Ireland Constitutional Convention

The Northern Ireland Constitutional Convention (NICC) was an elected body set up in 1975 by the United Kingdom Labour Party (UK), Labour government of Harold Wilson as an attempt to deal with constitutional issues surrounding the status of N ...

(1975–1976) and second Northern Ireland Assembly

The Northern Ireland Assembly (; ), often referred to by the metonym ''Stormont'', is the devolved unicameral legislature of Northern Ireland. It has power to legislate in a wide range of areas that are not explicitly reserved to the Parliam ...

(1982–1986) were unsuccessful at restoring devolution. In the absence of devolution and power-sharing, the UK Government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

and Irish Government

The Government of Ireland () is the executive authority of Ireland, headed by the , the head of government. The government – also known as the cabinet – is composed of ministers, each of whom must be a member of the , which consists of ...

formally agreed to co-operate on security, justice and political progress in the Anglo-Irish Agreement

The Anglo-Irish Agreement was a 1985 treaty between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland which aimed to help bring an end to the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The treaty gave the Irish government an advisory role in Northern Irelan ...

, signed on 15 November 1985. More progress was made after the ceasefires by the Provisional IRA

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provisional IRA), officially known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA; ) and informally known as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary force that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland ...

in 1994 and 1997.

The 1998 Belfast Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA) or Belfast Agreement ( or ; or ) is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April (Good Friday) 1998 that ended most of the violence of the Troubles, an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland since the la ...

(also known as the Good Friday Agreement), resulted in the creation of a new Northern Ireland Assembly, intended to bring together the two communities (nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

and unionist) to govern Northern Ireland.Jackson, Alvin (2003) ''Home Rule, an Irish History 1800–2000'', . Additionally, renewed devolution in Northern Ireland was conditional on co-operation between the newly established Northern Ireland Executive

The Northern Ireland Executive (Irish language, Irish: ''Feidhmeannas Thuaisceart Éireann'', Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster Scots: ''Norlin Airlan Executive'') is the devolution, devolved government of Northern Ireland, an administrative branc ...

and the Government of Ireland

The Government of Ireland () is the executive (government), executive authority of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, headed by the , the head of government. The government – also known as the cabinet (government), cabinet – is composed of Mini ...

through a new all-Ireland body, the North/South Ministerial Council

The North/South Ministerial Council (NSMC) (, Ulster-Scots: ) is a body established under the Good Friday Agreement to co-ordinate activity and exercise certain governmental powers across the whole island of Ireland.

The Council takes the for ...

. A British–Irish Council

The British–Irish Council (BIC; ) is an intergovernmental organisation that aims to improve collaboration between its members in a number of areas including transport, the environment and energy. Its membership comprises Ireland, the United ...

covering the whole British Isles and a British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference

The British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference (BIIGC) is an intergovernmental organisation established by the Governments of Ireland and the United Kingdom under the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. It first met in London in 1999, and the la ...

(between the British and Irish Governments) were also established.

From 15 October 2002, the Northern Ireland Assembly was suspended due to a breakdown in the Northern Ireland peace process

The Northern Ireland peace process includes the events leading up to the 1994 Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) ceasefire, the end of most of the violence of the Troubles, the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and subsequent political develop ...

but, on 13 October 2006, the British and Irish governments announced the St Andrews Agreement

The St Andrews Agreement (; Ulster Scots: ''St Andra's 'Greement'', ''St Andrew's Greeance'' or ''St Andrae's Greeance'') is an agreement between the British and Irish governments and Northern Ireland's political parties in relation to the de ...

, a 'road map' to restore devolution to Northern Ireland.. On 26 March 2007, Democratic Unionist Party

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a Unionism in Ireland, unionist, Ulster loyalism, loyalist, British nationalist and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who ...

(DUP) leader Ian Paisley

Ian Richard Kyle Paisley, Baron Bannside, (6 April 1926 – 12 September 2014) was a loyalist politician and Protestant religious leader from Northern Ireland who served as leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) from 1971 to 2008 and ...

met Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

leader Gerry Adams

Gerard Adams (; born 6 October 1948) is a retired Irish Republican politician who was the president of Sinn Féin between 13 November 1983 and 10 February 2018, and served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for Louth from 2011 to 2020. From 1983 to 19 ...

for the first time and together announced that a devolved government would be returning to Northern Ireland. The Executive was restored on 8 May 2007. Several policing and justice powers were transferred to the Assembly on 12 April 2010.

The 2007–2011 Assembly (the third since the 1998 Agreement) was dissolved on 24 March 2011 in preparation for an election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

to be held on Thursday 5 May 2011, this being the first Assembly since the Good Friday Agreement to complete a full term. The fifth Assembly convened in May 2016. That assembly dissolved on 26 January 2017, and an election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

for a reduced Assembly was held on 2 March 2017 but this did not lead to formation of a new Executive due to the collapse of power-sharing. Power-sharing collapsed in Northern Ireland due to the Renewable Heat Incentive scandal

The Renewable Heat Incentive scandal (RHI scandal), also referred to as RHIgate and the Cash for Ash scandal, is a political scandal in Northern Ireland that centres on a failed renewable energy (wood pellet burning) incentive scheme that has be ...

. On 11 January 2020, after having been suspended for almost three years, the parties reconvened on the basis of an agreement proposed by the Irish and UK governments. Elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

were held for a seventh assembly in May 2022. Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

emerged as the largest party, followed by the Democratic Unionist Party

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a Unionism in Ireland, unionist, Ulster loyalism, loyalist, British nationalist and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who ...

. The newly elected assembly met for the first time on 13 May 2022 and again on 30 May. However, at both these meetings, the DUP refused to assent to the election of a speaker as part of a protest against the Northern Ireland Protocol

The Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland, commonly abbreviated to the Northern Ireland Protocol (NIP), is a protocol to the Brexit withdrawal agreement that sets out Northern Ireland’s post-Brexit relationship with both the EU and Great Bri ...

, which meant that the assembly could not continue other business, including the appointment of a new Executive. On 3 February 2024, a new executive was formed marking the return of devolved government to Northern Ireland.

Scotland

TheActs of Union 1707

The Acts of Union refer to two acts of Parliament, one by the Parliament of Scotland in March 1707, followed shortly thereafter by an equivalent act of the Parliament of England. They put into effect the international Treaty of Union agree ...

merged the Parliament of Scotland

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

and the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the Great Council of England, great council of Lords Spi ...

into a single Parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in May 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union 1707, Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland. The Acts ratified the treaty of Union which created a ...

. Ever since, individuals and organisations advocated the return of a Scottish Parliament. The drive for home rule for Scotland first took concrete shape in the 19th century, as demands for home rule in Ireland were met with similar (although not as widespread) demands in Scotland. The National Association for the Vindication of Scottish Rights

The National Association for the Vindication of Scottish Rights was established in 1853. The first body to publicly articulate dissatisfaction with the Union since the Highland Potato Famine and the nationalist revolts in mainland Europe during ...

was established in 1853, a body close to the Scottish Unionist Party and motivated by a desire to secure more focus on Scottish problems in response to what they felt was undue attention being focused on Ireland by the then Liberal government. In 1871, William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

stated at a meeting held in Aberdeen

Aberdeen ( ; ; ) is a port city in North East Scotland, and is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, third most populous Cities of Scotland, Scottish city. Historically, Aberdeen was within the historic county of Aberdeensh ...

that if Ireland was to be granted home rule, then the same should apply to Scotland. A Scottish home rule bill was presented to the Westminster Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

in 1913 but the legislative process was interrupted by the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

The demands for political change in the way in which Scotland was run changed dramatically in the 1920s when Scottish nationalists started to form various organisations. The Scots National League

The Scots National League (SNL) was a political organisation which campaigned for Scottish independence in the 1920s. It amalgamated with other Scottish nationalism, Scottish nationalist bodies in 1928 to form the National Party of Scotland.

T ...

was formed in 1920 in favour of Scottish independence

Scottish independence (; ) is the idea of Scotland regaining its independence and once again becoming a sovereign state, independent from the United Kingdom. The term Scottish independence refers to the political movement that is campaignin ...

, and this movement was superseded in 1928 by the formation of the National Party of Scotland

The National Party of Scotland (NPS) was a centre-left political party in Scotland which was one of the predecessors of the current Scottish National Party (SNP). The NPS was the first Scottish nationalist political party, and the first which ...

, which became the Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party (SNP; ) is a Scottish nationalist and social democratic party. The party holds 61 of the 129 seats in the Scottish Parliament, and holds 9 out of the 57 Scottish seats in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, ...

(SNP) in 1934. At first the SNP sought only the establishment of a devolved Scottish assembly, but in 1942 they changed this to support all-out independence. This caused the resignation of John MacCormick

John MacDonald MacCormick (20 November 1904 – 13 October 1961) was a Scottish lawyer, Scottish nationalist politician and advocate of Home Rule in Scotland.

Early life

MacCormick was born in Pollokshields, Glasgow, in 1904. His father was D ...

from the SNP and he formed the Scottish Covenant Association

The Scottish Covenant Association was a non-partisan political organisation in Scotland in the 1940s and 1950s seeking to establish a devolved Scottish Assembly. It was formed by John MacCormick who had left the Scottish National Party in 1942 ...

. This body proved to be the biggest mover in favour of the formation of a Scottish assembly, collecting over two million signatures in the late 1940s and early 1950s and attracting support from across the political spectrum. However, without formal links to any of the political parties it withered, devolution and the establishment of an assembly were put on the political back burner.

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx (11 March 1916 – 23 May 1995) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1964 to 1970 and again from 197 ...

's Labour government set up a Royal Commission on the Constitution in 1969, which reported in 1973 to Edward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George Heath (9 July 1916 – 17 July 2005) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1970 to 1974 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1965 ...

's Conservative government. The Commission recommended the formation of a devolved Scottish assembly, but was not implemented. Support for the SNP reached 30% in the October 1974 general election, with 11 SNP MPs being elected. In 1978 the Labour government passed the Scotland Act which legislated for the establishment of a Scottish Assembly, provided the Scots voted for such in a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

. However, the Labour Party was bitterly divided on the subject of devolution. An amendment to the Scotland Act that had been proposed by Labour MP George Cunningham, who shortly afterwards defected to the newly formed Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Form ...

(SDP), required 40% of the total electorate to vote in favour of an assembly. Despite officially favouring it, considerable numbers of Labour members opposed the establishment of an assembly. This division contributed to only a narrow 'Yes' majority being obtained, and the failure to reach Cunningham's 40% threshold. The 18 years of Conservative government, under Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

and then John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British retired politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997. Following his defeat to Ton ...

, saw strong resistance to any proposal for devolution for Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, and for Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

.

In response to Conservative dominance, in 1989 the Scottish Constitutional Convention

The Scottish Constitutional Convention (SCC) was an association of Scottish political parties, churches and other civic groups, that developed a framework for Scottish devolution.

History

Campaign for a Scottish Assembly

The Conventi ...

was formed encompassing the Labour Party, Liberal Democrats and the Scottish Green Party

The Scottish Greens (also known as the Scottish Green Party; ) are a green party, green List of political parties in Scotland, political party in Scotland. The party has 7 MSPs of 129 in the Scottish Parliament, the party holds 35 of the 1226 ...

, local authorities

Local government is a generic term for the lowest tiers of governance or public administration within a particular sovereign state.

Local governments typically constitute a subdivision of a higher-level political or administrative unit, such a ...

, and sections of "civic Scotland" like Scottish Trades Union Congress

The Scottish Trades Union Congress (STUC) is the national trade union centre in Scotland. With 40 affiliated unions as of 2020, the STUC represents over 540,000 trade unionists.

The STUC is a separate organisation from the English and Welsh ...

, the Small Business Federation and Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

and the other major churches in Scotland. Its purpose was to devise a scheme for the formation of a devolution settlement for Scotland. The SNP decided to withdraw as independence was not a constitutional option countenanced by the convention. The convention produced its final report in 1995. In May 1997, the Labour government of Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He was Leader ...

was elected with a promise of creating devolved institutions in Scotland. In late 1997, a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

was held which resulted in a "yes" vote. The newly created Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament ( ; ) is the Devolution in the United Kingdom, devolved, unicameral legislature of Scotland. It is located in the Holyrood, Edinburgh, Holyrood area of Edinburgh, and is frequently referred to by the metonym 'Holyrood'. ...

(as a result of the Scotland Act 1998

The Scotland Act 1998 (c. 46) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which legislated for the establishment of the devolved Scottish Parliament with tax varying powers and the Scottish Government (then Scottish Executive). It was o ...

) has powers to make primary legislation

Legislation is the process or result of enrolling, enacting, or promulgating laws by a legislature, parliament, or analogous governing body. Before an item of legislation becomes law it may be known as a bill, and may be broadly referred ...

in all areas of policy which are not expressly 'reserved' for the UK Government and parliament such as national defence and international affairs. 76% of Scotland's revenue and 36% of its spending are 'reserved'. Devolution for Scotland was justified on the basis that it would make government more representative of the people of Scotland. It was argued that the population of Scotland felt detached from the Westminster government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

(largely because of the policies of the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

governments led by Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

and John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British retired politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997. Following his defeat to Ton ...

). Critics however point out that the Scottish Parliament's power is on most measures surpassed by the parliaments of regions or provinces within federations, where regional and national parliaments are each sovereign within their spheres of jurisdiction.

A referendum on Scottish independence was held on 18 September 2014, with the referendum being defeated 55.3% (No) to 44.7% (Yes). In the 2015 general election the SNP won 56 of the 59 Scottish seats with 50% of all Scottish votes. This saw the SNP replace the Liberal Democrats as the third largest in the UK Parliament. In the 2016 Scottish Parliament election the SNP fell two seats short of an overall majority with 63 seats but remained in government for a third term. The proportional electoral system used for Holyrood elections makes it very difficult for any party to gain a majority. The Scottish Conservatives

The Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party (), known as Scottish Tories, is part of the UK Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party active in Scotland. It currently holds 5 of the 57 Scottish seats in the House of Commons of the United Ki ...

won 31 seats and became the second largest party for the first time. Scottish Labour

Scottish Labour (), is the part of the UK Labour Party (UK), Labour Party active in Scotland. Ideologically social democratic and Unionism in the United Kingdom, unionist, it holds 23 of 129 seats in the Scottish Parliament and 37 of 57 Sco ...

, down to 24 seats from 38, fell to third place. The Scottish Greens

The Scottish Greens (also known as the Scottish Green Party; ) are a green political party in Scotland. The party has 7 MSPs of 129 in the Scottish Parliament, the party holds 35 of the 1226 councillors at Scottish local Government level.

The ...

took 6 seats and overtook the Liberal Democrats who remained flat at 5 seats. Following the 2016 referendum on EU membership, where Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to Remain and England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

voted to Leave (leading to a 52% Leave vote nationwide), the Scottish Parliament voted for a second independence referendum to be held once conditions of the UK's EU exit are known.

The SNP had advocated for another independence referendum to be held in 2020. The SNP were widely expected to include a second independence referendum in their manifesto for the 2021 Scottish Parliament election

The 2021 Scottish Parliament election took place on 6 May 2021 under the provisions of the Scotland Act 1998. It was the sixth Scottish Parliament election since the parliament was re-established in 1999. 129 Member of the Scottish Parliament, ...

. Senior SNP figures have said that a second independence referendum would be inevitable, should an SNP majority be elected to the Scottish Parliament in 2021 and some claimed this was going to happen by the end of 2021, though that hasn't been the case.

The United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020

The United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020 (c. 27) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed in December 2020. Its purpose is to prevent internal trade barriers within the UK, and to restrict the legislative powers of the d ...

restricts and undermines the authority of the Scottish Parliament. Its primary purpose is to constrain the capacity of the devolved institutions to use their regulatory autonomy. It restricts the ability of the Scottish government to make different economic or social choices from those made in Westminster.

Wales

Following theLaws in Wales Acts 1535–1542

The Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 () or the Acts of Union (), were acts of the Parliament of England under King Henry VIII of England, causing Wales to be incorporated into the realm of the Kingdom of England.

The legal system of England ...

, Wales was treated in legal terms as part of England. However, during the later part of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century the notion of a distinctive Welsh polity

A polity is a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of political Institutionalisation, institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources.

A polity can be any group of people org ...

gained credence. In 1881 the Sunday Closing (Wales) Act 1881 was passed, the first such legislation exclusively concerned with Wales. The Central Welsh Board was established in 1896 to inspect the grammar schools set up under the Welsh Intermediate Education Act 1889

The Welsh Intermediate Education Act 1889 (52 & 53 Vict. c. 40) was an Act of Parliament, Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It made various reforms with the intention of expanding access to secondary education in Wales.

Background ...

, and a separate Welsh Department of the Board of Education was formed in 1907. The Agricultural Council for Wales was set up in 1912, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries had its own Welsh Office from 1919.

Despite the failure of popular political movements such as , a number of national institutions, such as the National Eisteddfod

The National Eisteddfod of Wales ( Welsh: ') is the largest of several eisteddfodau that are held annually, mostly in Wales. Its eight days of competitions and performances are considered the largest music and poetry festival in Europe. Competito ...

(1861), the Football Association of Wales

The Football Association of Wales (FAW; ) is the Governing bodies of sports in Wales, governing body of association football and futsal in Wales, and controls the Wales national football team, its Wales women's national football team, correspo ...

(1876), the Welsh Rugby Union

The Welsh Rugby Union (WRU; ) is the governing body of rugby union in the country of Wales, recognised by the sport's international governing body, World Rugby.

The WRU is responsible for the running of rugby in Wales, overseeing 320 member clu ...

(1881), the University of Wales

The University of Wales () is a confederal university based in Cardiff, Wales. Founded by royal charter in 1893 as a federal university with three constituent colleges – Aberystwyth, Bangor and Cardiff – the university was the first universit ...

(, 1893), the National Library of Wales

The National Library of Wales (, ) in Aberystwyth is the national legal deposit library of Wales and is one of the Welsh Government sponsored bodies. It is the biggest library in Wales, holding over 6.5 million books and periodicals, and the l ...

(, 1911) and the Welsh Guards

The Welsh Guards (WLSH GDS; ), part of the Guards and Parachute Division, Guards Division, is one of the Foot guards, Foot Guards regiments of the British Army. It was founded in 1915 as a single-battalion regiment, during the World War I, First ...

(, 1915) were created. The campaign for disestablishment of the Anglican Church in Wales, achieved by the passage of the Welsh Church Act 1914

The Welsh Church Act 1914 (4 & 5 Geo. 5. c. 91) is an act of Parliament (UK), act of Parliament under which the Church of England was separated and disestablishment, disestablished in Wales and Monmouthshire (historic), Monmouthshire, leading to ...

, was also significant in the development of Welsh political consciousness. Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru ( ; , ; officially Plaid Cymru – the Party of Wales, and often referred to simply as Plaid) is a centre-left, Welsh nationalist list of political parties in Wales, political party in Wales, committed to Welsh independence from th ...

was formed in 1925.

An appointed Council for Wales and Monmouthshire

The Council for Wales and Monmouthshire (), was an appointed advisory body announced in 1948 and established in 1949 by the UK government under Labour prime minister Clement Attlee, to advise the government on matters of Welsh interest. It w ...

was established in 1949 to "ensure the government is adequately informed of the impact of government activities on the general life of the people of Wales". The council had 27 members nominated by local authorities in Wales, the University of Wales

The University of Wales () is a confederal university based in Cardiff, Wales. Founded by royal charter in 1893 as a federal university with three constituent colleges – Aberystwyth, Bangor and Cardiff – the university was the first universit ...

, National Eisteddfod Council and the Welsh Tourist Board

Visit Wales () is the Welsh Government's tourism organisation. Its aim is to promote Welsh tourism and assist the tourism industry.

History

The Wales Tourist Board was established in 1969 as a result of the Development of Tourism Act 1969 a ...

. A cross-party Parliament for Wales campaign in the early 1950s was supported by a number of Labour MPs, mainly from the more Welsh-speaking areas, together with the Liberal Party and Plaid Cymru. A post of Minister of Welsh Affairs was created in 1951 and the post of Secretary of State for Wales

The secretary of state for Wales (), also referred to as the Welsh secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with responsibility for the Wales Office. The incumbent is a member of the Cabinet of the United Ki ...

and the Welsh Office

The Welsh Office () was a department in the Government of the United Kingdom with responsibilities for Wales. It was established in April 1965 to execute government policy in Wales, and was headed by the Secretary of State for Wales, a post wh ...

were established in 1964 leading to the abolition of the Council for Wales and Monmouthshire.

Labour's incremental embrace of a distinctive Welsh polity was arguably catalysed in 1966 when Plaid Cymru president Gwynfor Evans

Gwynfor Richard Evans (1 September 1912 – 21 April 2005) was a Welsh politician, lawyer and author. He was President of the Welsh political party Plaid Cymru for thirty-six years and was the first member of Parliament to represent it at West ...

won the Carmarthen by-election. In response to the emergence of Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party (SNP; ) is a Scottish nationalist and social democratic party. The party holds 61 of the 129 seats in the Scottish Parliament, and holds 9 out of the 57 Scottish seats in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, ...

(SNP) Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx (11 March 1916 – 23 May 1995) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1964 to 1970 and again from 197 ...

's Labour Government set up the Royal Commission on the Constitution (the Kilbrandon Commission) to investigate the UK's constitutional arrangements in 1969. The 1974–1979 Labour government proposed a Welsh Assembly

The Senedd ( ; ), officially known as the Welsh Parliament in English and () in Welsh, is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Wales. A democratically elected body, Its role is to scrutinise the Welsh Government and legislate on devolve ...

in parallel to its proposals for Scotland. These were rejected by voters in the 1979 referendum: 956,330 votes against, 243,048 for.

In May 1997, the Labour government of Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He was Leader ...

was elected with a promise of creating a devolved assembly in Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

; the referendum in 1997 resulted in a narrow "yes" vote. The turnout was 50.22% with 559,419 votes (50.3%) in favour and 552,698 (49.7%) against, a majority of 6,721 (0.6%). The National Assembly for Wales

The Senedd ( ; ), officially known as the Welsh Parliament in English and () in Welsh, is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Wales. A democratically elected body, Its role is to scrutinise the Welsh Government and legislate on devolve ...

, as a consequence of the Government of Wales Act 1998

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

, possesses the power to determine how the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

budget for Wales is spent and administered. The 1998 Act was followed by the Government of Wales Act 2006

The Government of Wales Act 2006 (c. 32) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed the then-National Assembly for Wales (now the Senedd) and allows further powers to be granted to it more easily. The Act creates a system ...

which created an executive body, the Welsh Government

The Welsh Government ( ) is the Executive (government), executive arm of the Welsh devolution, devolved government of Wales. The government consists of Cabinet secretary, cabinet secretaries and Minister of State, ministers. It is led by the F ...

, separate from the legislature, the National Assembly for Wales. It also conferred on the National Assembly some limited legislative powers.

The 1997 devolution referendum was only narrowly passed with the majority of voters in the former industrial areas of the South Wales Valleys

The South Wales Valleys () are a group of industrialised peri-urban valleys in South Wales. Most of the valleys run northsouth, roughly parallel to each other. Commonly referred to as "The Valleys" (), they stretch from Carmarthenshire in the ...

and the Welsh-speaking heartlands of West Wales

West Wales () is a region of Wales.

It has various definitions, either covering Pembrokeshire, Ceredigion and Carmarthenshire, which historically comprised the Welsh principality of ''Deheubarth'', and an alternative definition is to include Swa ...

and North Wales

North Wales ( ) is a Regions of Wales, region of Wales, encompassing its northernmost areas. It borders mid Wales to the south, England to the east, and the Irish Sea to the north and west. The area is highly mountainous and rural, with Snowdon ...

voting for devolution and the majority of voters in all the counties near England, plus Cardiff

Cardiff (; ) is the capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of Wales. Cardiff had a population of in and forms a Principal areas of Wales, principal area officially known as the City and County of Ca ...

and Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; ) is a Principal areas of Wales, county in the South West Wales, south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and otherwise by the sea. Haverfordwest is the largest town and ...

rejecting devolution. However, all recent opinion polls indicate an increasing level of support for further devolution, with support for some tax varying powers now commanding a majority, and diminishing support for the abolition of the Assembly.

The 2011 Welsh devolution referendum

A referendum on the powers of the National Assembly for Wales was held on 3 March 2011. Voters were asked whether the Assembly should have full law-making powers in the twenty subject areas where it has jurisdiction. The referendum asked the q ...

saw a majority of 21 local authority constituencies to 1 voting in favour of more legislative powers being transferred from the UK parliament in Westminster to the Welsh Assembly. The turnout in Wales was 35.4% with 517,132 votes (63.5%) in favour and 297,380 (36.5%) against increased legislative power.

A Commission on Devolution in Wales

In-Commission or commissioning may refer to:

Business and contracting

* Commission (remuneration), a form of payment to an agent for services rendered

** Commission (art), the purchase or the creation of a piece of art most often on behalf of anot ...

was set up in October 2011 to consider further devolution of powers from London. The commission issued a report on the devolution of fiscal powers in November 2012 and a report on the devolution of legislative powers in March 2014. The fiscal recommendations formed the basis of the Wales Act 2014

The Wales Act 2014legislation.gov.uk

Wales Act 2014 (c. 29) is an Wales Act 2017 The Wales Act 2017 (c. 7) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It sets out amendments to the Government of Wales Act 2006 and devolves further powers to Wales. The legislation is based on the proposals of the St David's Day Comma ...

.

On 6 May 2020, the National Assembly was renamed or ''the Welsh Parliament'' with the becoming its common name in both languages.

The devolved competence of the Welsh Government, as the Scottish Government, is restricted and undermined by the Wales Act 2014 (c. 29) is an Wales Act 2017 The Wales Act 2017 (c. 7) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It sets out amendments to the Government of Wales Act 2006 and devolves further powers to Wales. The legislation is based on the proposals of the St David's Day Comma ...

United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020

The United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020 (c. 27) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed in December 2020. Its purpose is to prevent internal trade barriers within the UK, and to restrict the legislative powers of the d ...

.

England

National

There have been proposals for the establishment of a singledevolved English parliament

A devolved English parliament is a proposed institution that would give separate decision-making powers to representatives for voters in England, similar to the representation given by the Senedd (Welsh Parliament), the Scottish Parliament and ...

to govern the affairs of England as a whole. This has been supported by groups such as English Commonwealth, the English Democrats

The English Democrats are a right-wing-to-far-right, English nationalist political party active in England. A minor party, it currently has no elected representatives at any level of government.

The English Democrats were established in 200 ...

, and Campaign for an English Parliament

The Campaign for an English Parliament (CEP) is a pressure group which seeks the establishment of a devolved English parliament. The CEP is the main organisation associated with an English Parliament. It was formed as a non-denominational lob ...

, as well as the Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party (SNP; ) is a Scottish nationalist and social democratic party. The party holds 61 of the 129 seats in the Scottish Parliament, and holds 9 out of the 57 Scottish seats in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, ...

and Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru ( ; , ; officially Plaid Cymru – the Party of Wales, and often referred to simply as Plaid) is a centre-left, Welsh nationalist list of political parties in Wales, political party in Wales, committed to Welsh independence from th ...

who have both expressed support for greater autonomy for all four nations while ultimately striving for a dissolution of the Union. Without its own devolved Parliament, England continues to be governed and legislated for by the UK Government and UK Parliament, which gives rise to the West Lothian question

The West Lothian question, also known as the English question, is a political issue in the United Kingdom. It concerns the question of whether members of Parliament (MPs) from Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales who sit in the House of Commo ...

. The question concerns the fact that, on devolved matters, Scottish MPs continue to help make laws that apply to England alone, although no English MPs can make laws on those same matters for Scotland. Since the 2014 Scottish independence referendum

A independence referendum, referendum on Scottish independence from the United Kingdom was held in Scotland on 18 September 2014. The referendum question was "Should Scotland be an independent country?", which voters answered with "Yes" or ...

, there has been a wider debate about the UK adopting a federal system

Federalism is a mode of government that combines a general level of government (a central or federal government) with a regional level of sub-unit governments (e.g., provinces, states, cantons, territories, etc.), while dividing the powers o ...

with each of the four Home Nations having its own, equal devolved legislatures and law-making powers.

In the first five years of devolution for Scotland and Wales, support in England for the establishment of an English parliament was low at between 16 and 19 per cent. While a 2007 opinion poll found that 61 per cent would support such a parliament being established, a report based on the British Social Attitudes Survey

The British Social Attitudes Survey (BSA) is an annual statistical survey conducted in Great Britain by National Centre for Social Research since 1983. The BSA involves in-depth interviews with over 3,300 respondents, selected using Survey samplin ...

published in December 2010 suggests that only 29 per cent of people in England support the establishment of an English parliament, though this figure has risen from 17 per cent in 2007. John Curtice

Sir John Kevin Curtice (born 10 December 1953) is a British political scientist and professor of politics at the University of Strathclyde and senior research fellow at the National Centre for Social Research. He is particularly interested in ...

argues that tentative signs of increased support for an English parliament might represent "a form of English nationalism ... beginning to emerge among the general public". Krishan Kumar, however, notes that support for measures to ensure that only English MPs can vote on legislation that applies only to England is generally higher than that for the establishment of an English parliament, although support for both varies depending on the timing of the opinion poll and the wording of the question.

In September 2011 it was announced that the British government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

was to set up a commission to examine the West Lothian question. In January 2012 it was announced that this six-member commission would be named the Commission on the consequences of devolution for the House of Commons

The Commission on the consequences of devolution for the House of Commons, also known as the McKay Commission, was an independent commission established in the United Kingdom to consider issues arising from devolution in the United Kingdom and t ...

, would be chaired by former Clerk of the House of Commons

The clerk of the House of Commons is the chief executive of the House of Commons in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, and before 1707 in the House of Commons of England.

The formal name for the position held by the Clerk of the House of Co ...

, Sir William McKay, and would have one member from each of the devolved countries. The McKay Commission reported in March 2013.

English votes for English laws

On 22 October 2015 The House of Commons voted in favour of implementing a system of " English votes for English laws" by 312 votes to 270 after four hours of intense debate. Amendments to the proposed standing orders put forward by both Labour and The Liberal Democrats were defeated. Scottish National Party MPs criticized the measures stating that the bill would render Scottish MPs as "second class citizens". Under the new procedures, if theSpeaker of The House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hung ...

determines if a proposed bill or statutory instrument exclusively affects England, England and Wales or England, Wales and Northern Ireland, then legislative consent should be obtained via a Legislative Grand Committee

The legislative grand committees were committees of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. They were established in 2015 and abolished in July 2021.

There were three legislative grand committees:

* ''Legislative Grand Committee (England)'', mad ...

. This process was performed at the second reading of a bill or instrument as an attempt at answering the West Lothian question

The West Lothian question, also known as the English question, is a political issue in the United Kingdom. It concerns the question of whether members of Parliament (MPs) from Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales who sit in the House of Commo ...

. English votes for English laws was suspended in April 2020, and in July 2021 the House of Commons abolished it, returning to the previous system with no special mechanism for English laws.

Sub-national

north

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

, the midlands

The Midlands is the central region of England, to the south of Northern England, to the north of southern England, to the east of Wales, and to the west of the North Sea. The Midlands comprises the ceremonial counties of Derbyshire, Herefor ...

and the south

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

.

Regional

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, as part of the debate on Home Rule for Ireland

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the end of ...

. In a speech in Dundee

Dundee (; ; or , ) is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, fourth-largest city in Scotland. The mid-year population estimate for the locality was . It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firt ...

on 12 September, Churchill proposed that the government of England should be divided up among regional parliaments, with power devolved to areas such as Lancashire, Yorkshire, the Midlands and London as part of a federal system of government.

The division of England into provinces or regions was explored by several post-Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

royal commissions. The Redcliffe-Maud Report

The Redcliffe-Maud Report (Cmnd.4040) was a 1969 command paper report from the Royal Commission on Local Government in England, under the chairmanship of Lord Redcliffe-Maud. The commission was formed in 1966 to examine the structure of local go ...

of 1969 proposed devolving power from central government to eight provinces in England. In 1973 the Royal Commission on the Constitution proposed the creation of eight English appointed regional assemblies with an advisory role; although the report stopped short of recommending legislative devolution to England, a minority of signatories wrote a memorandum of dissent which put forward proposals for devolving power to elected assemblies for Scotland and Wales, and five regional assemblies in England.

The 1966–1969 Redcliffe-Maud Report

The Redcliffe-Maud Report (Cmnd.4040) was a 1969 command paper report from the Royal Commission on Local Government in England, under the chairmanship of Lord Redcliffe-Maud. The commission was formed in 1966 to examine the structure of local go ...

recommended the abolition of all existing two-tier councils and council areas in England and replacing them with 58 new unitary authorities

A unitary authority is a type of local government, local authority in New Zealand and the United Kingdom. Unitary authorities are responsible for all local government functions within its area or performing additional functions that elsewhere are ...

alongside three metropolitan areas

A metropolitan area or metro is a region consisting of a densely populated urban agglomeration and its surrounding territories which share industries, commercial areas, transport network, infrastructures and housing. A metropolitan area usually ...

(Merseyside

Merseyside ( ) is a ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial and metropolitan county in North West England. It borders Lancashire to the north, Greater Manchester to the east, Cheshire to the south, the Wales, Welsh county of Flintshire across ...

, ' Selnec', and the West Midlands). These would have been grouped into eight provinces with a provincial council each. The report was initially accepted "in principle" by the government.

In April 1994, the Government of John Major created a set of ten Government Office

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a mea ...

Regions for England to coordinate central government departments at a provincial level. Regional Development Agencies

In the United Kingdom, regional development agencies (RDAs) were nine non-departmental public bodies established for the purpose of development, primarily economic, of England's Government Office regions between 1998 and 2010. There was one RD ...

were set up in 1998 under the Government of Tony Blair to foster economic growth around England. These Agencies were supported by a set of eight newly created Regional Assemblies, or Chambers. These bodies were not directly elected but members were appointed by local government and local interest groups.

In a white paper published in 2002, the government proposed decentralisation of power across England similar to that done for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland in 1998. Regional Assemblies were abolished between 2008 and 2010, but the Regions of England

The regions of England, formerly known as the government office regions, are the highest tier of sub-national division in England. They were established in 1994 and follow the 1974–96 county borders. They are a continuation of the former 194 ...

continue to be used in certain governmental administrative functions.

Greater London

Following a referendum in 1998, a directly elected administrative body was created for Greater London, theGreater London Authority

The Greater London Authority (GLA), colloquially known by the Metonymy, metonym City Hall, is the Devolution in the United Kingdom, devolved Regions of England, regional governance body of Greater London, England. It consists of two political ...

which has "accrued significantly more power than were originally envisaged."

Within the Greater London Authority (GLA) are the elected Mayor of London

The mayor of London is the chief executive of the Greater London Authority. The role was created in 2000 after the Greater London devolution referendum in 1998, and was the first directly elected mayor in the United Kingdom.

The current ...

and London Assembly

The London Assembly is a 25-member elected body, part of the Greater London Authority, that scrutinises the activities of the Mayor of London and has the power, with a two-thirds supermajority, to amend the Mayor's annual budget and to reject t ...

. The GLA is colloquially referred to as the City Hall and their powers include overseeing Transport for London

Transport for London (TfL) is a local government body responsible for most of the transport network in London, United Kingdom.

TfL is the successor organization of the London Passenger Transport Board, which was established in 1933, and His ...

, work of the Metropolitan Police, London Fire and Emergency Planning Authority

The London Fire and Emergency Planning Authority (LFEPA) was a functional body of the Greater London Authority (GLA) from 2000 to 2018. It was established with the Greater London Authority by the Greater London Authority Act 1999. It replaced the ...

, various redevelopment corporations, and the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park is a sporting complex and public park in Stratford, Hackney Wick, Leyton and Bow, in east London. It was purpose-built for the 2012 Summer Olympics and Paralympics, situated adjacent to the Stratford City devel ...

. In 2013, the GLA established the Devolution Working Group to oversee and further devolution in London. In 2017 the work of these authorities along with Public Health England

Public Health England (PHE) was an executive agency of the Department of Health and Social Care in England which began operating on 1 April 2013 to protect and improve health and wellbeing and reduce health inequalities. Its formation came as a ...

achieved a devolution agreement with the national government in regard to some healthcare services.

North

Northern England has a statutory transport body,Transport for the North

Transport for the North (TfN) is the first statutory sub-national transport body in the United Kingdom. It was formed in 2018 to make the case for strategic transport improvements across the North of England. Creating this body represented ...

. Multiple bodies are or have advocated for further devolution to Northern England. The Northern Powerhouse Partnership is one of these, made up of businesses and civil leaders.

In May 2025 the mayors of combined authorities across the North of England

Northern England, or the North of England, refers to the northern part of England and mainly corresponds to the historic counties of Cheshire, Cumberland, Durham, Lancashire, Northumberland, Westmorland and Yorkshire. Officially, it is a gr ...

(Greater Manchester, Hull and East Yorkshire, Liverpool City Region, North East, South Yorkshire, Tees Valley, West Yorkshire, York and North Yorkshire) launched a partnership known as The Great North

{{Infobox television

, image = The Great North Title Card.png

, genre = Animated sitcom

, creator = Lizzie Molyneux-Logelin & Wendy Molyneux & Minty Lewis

, voices = {{Plainlist,

* Ni ...

. The partnership, whose brand is based on the Great North Run

The Great North Run (branded the AJ Bell Great North Run for sponsorship purposes) is the largest half marathon in the world, taking place annually in North East England each September. Participants run between Newcastle upon Tyne and South Shie ...

, will lead trade missions and focus on pan-North investment propositions including hosting a Northern investment summit.

The Northern Party

The Northern Party was a Regionalism (politics), regionalist political party in Northern England, founded by leader Michael Dawson and former Blackpool MP; Harold Elletson, in March 2015 to contest five marginal seats in Lancashire at the 2015 Un ...

was a political party established to campaign for Devolution to the North of England

Northern England devolution is the broad term used to describe the wish for devolved governmental powers that would give more autonomy to the Northern England, Northern Counties of England, Counties (those northern parts of England in the North� ...

through the creation of a Regional Government over covering the six historic counties of the region. The Campaign aimed to create a Northern Government with tax-raising powers and responsibility for policy areas including economic development, education, health, policing and emergency services.

The Northern Independence Party is a sepretist, democratic socialist

Democratic socialism is a left-wing economic and political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self-mana ...

party founded in 2020, in response to the perceived growth of the North–South divide in England

In England, the term North–South divide refers to the cultural, economic, and social differences between Southern England and Northern England:

*Southern England usually refers to South East England, South West England and in some definition ...

, aiming for the formation of an independent country in the north of England under the name of Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

, after the early medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the same name. The party currently has no elected representatives in parliament.

North East England

A proposal to devolve political power to a fully elected Regional Assembly was put to public vote in the2004 North East England devolution referendum

The 2004 North East England devolution referendum was an all postal ballot referendum that took place on 4 November 2004 throughout North East England on whether or not to establish an elected assembly for the region. Devolution referendums i ...

. This, however, was defeated 78% to 22%, resulting in the cancellation of subsequent referendums planned in North West England

North West England is one of nine official regions of England and consists of the ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial counties of Cheshire, Cumbria, Greater Manchester, Lancashire and Merseyside. The North West had a population of 7,4 ...

and Yorkshire and the Humber

Yorkshire and the Humber is one of the nine official regions of England at the first level of ITL for statistical purposes. It is one of the three regions covering Northern England, alongside the North West England and North East England regio ...

, with the government abandoning its plans of regional devolution altogether. As well as facilitating an elected assembly, the proposal would also have reorganised local government in the area. However, the North East Combined Authority, covering much of the region, is to be formed in 2024.

Yorkshire

Arguments for devolution to Yorkshire, which has a population of 5.4 million – similar to Scotland – and whose economy is roughly twice as large as that of Wales, include focus on the area as acultural region

In anthropology and geography, a cultural area, cultural region, cultural sphere, or culture area refers to a geography with one relatively homogeneous human activity or complex of activities (culture). Such activities are often associa ...

or even a nation

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective Identity (social science), identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, t ...

separate from England, whose inhabitants share common features.

This cause has also been supported by the cross-party One Yorkshire group of 18 local authorities (out of 20) in Yorkshire. One Yorkshire has sought the creation of a directly elected mayor of Yorkshire, devolution of decision-making to Yorkshire, and giving the county access to funding and benefits similar to combined authorities. Various proposals differ between establishing this devolved unit in Yorkshire and the Humber (which excludes parts of Yorkshire and includes parts of Lincolnshire), in the county of Yorkshire as a whole, or in parts of Yorkshire, with Sheffield