Constitutional Reforms of Julius Caesar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The constitutional reforms of

When Caesar returned to Rome in 47 BC, the ranks of the senate had been severely depleted, and so he used his Censorial powers to appoint many new senators, which eventually raised the senate's membership to 900.Abbott, 137 All of these appointments were of his own partisans, which robbed the senatorial aristocracy of its prestige, and made the senate increasingly subservient to him.Abbott, 138 While the assemblies continued to meet, Caesar submitted all candidates to the assemblies for election, and all bills to the assemblies for enactment, which caused the assemblies to become powerless and unable to oppose him.Abbott, 138 To minimize the risk that another general might attempt to challenge him,Abbott, 136 Caesar passed a law which subjected governors to term limits: Governors of Praetorial provinces had to abdicate their office after one year, while governors of Consular provinces had to abdicate their office after two years.Abbott, 136 Near the end of his life, Caesar began to prepare for a war against the

When Caesar returned to Rome in 47 BC, the ranks of the senate had been severely depleted, and so he used his Censorial powers to appoint many new senators, which eventually raised the senate's membership to 900.Abbott, 137 All of these appointments were of his own partisans, which robbed the senatorial aristocracy of its prestige, and made the senate increasingly subservient to him.Abbott, 138 While the assemblies continued to meet, Caesar submitted all candidates to the assemblies for election, and all bills to the assemblies for enactment, which caused the assemblies to become powerless and unable to oppose him.Abbott, 138 To minimize the risk that another general might attempt to challenge him,Abbott, 136 Caesar passed a law which subjected governors to term limits: Governors of Praetorial provinces had to abdicate their office after one year, while governors of Consular provinces had to abdicate their office after two years.Abbott, 136 Near the end of his life, Caesar began to prepare for a war against the

Cicero's De Re Publica, Book Two

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20080829134354/http://www.uah.edu/student_life/organizations/SAL/texts/misc/romancon.html The Roman Constitution to the Time of Cicero

What a Terrorist Incident in Ancient Rome Can Teach Us

in 1 part

an

in 8 parts

{{Ancient Rome topics Julius Caesar Roman Republic Roman law 40s BC 1st century BC in the Roman Republic Reform in the Roman Republic

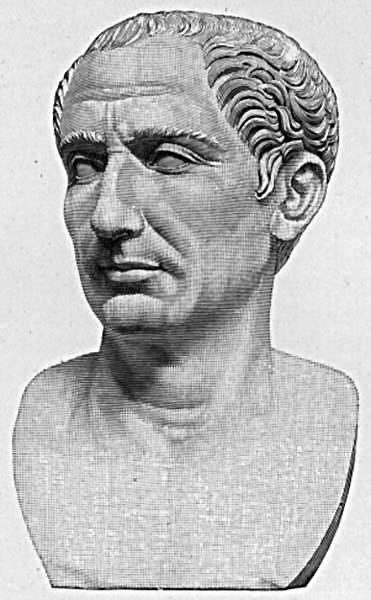

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, ...

were a series of laws to the Constitution of the Roman Republic

The constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of uncodified norms and customs which, together with various written laws, guided the procedural governance of the Roman Republic. The constitution emerged from that of the Roman kingdom, evolve ...

enacted between 49 and 44 BC, during Caesar's dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

. Caesar was murdered in 44 BC before the implications of his constitutional actions could be realized.

Julius Caesar's constitutional framework

During his early career, Caesar had seen how chaotic and dysfunctional the Roman Republic had become. The republican machinery had broken down under the weight of imperialism, the central government had become powerless, the provinces had been transformed into independent principalities under the absolute control of their governors, and the army had replaced the constitution as the means of accomplishing political goals. With a weak central government, political corruption had spiraled out of control, and the status quo had been maintained by a corrupt aristocracy, which saw no need to change a system which had made all of its members quite rich. Between his crossing of the Rubicon River in 49 BC, and his assassination in 44 BC, Caesar established a new constitution, which was intended to accomplish three separate goals.Abbott, 133 First, he wanted to suppress all armed resistance out in the provinces, and thus bring order back to the Republic. Second, he wanted to create a strong central government in Rome. And finally, he wanted to knit together the entire Republic into a single cohesive unit. The first goal was accomplished when Caesar defeated Pompey and his supporters. To accomplish the other two goals, he needed to ensure that his control over the government was undisputed,Abbott, 134 and so he assumed these powers by increasing his own authority, and by decreasing the authority of Rome's other political institutions. To increase his own powers, he assumed the important magistrates,Abbott, 134 and to weaken Rome's other political institutions, he instituted several additional reforms. He controlled the process by which candidates were nominated for magisterial elections, he appointed his own supporters to the senate, and he prevented hostile measures from being adopted by the assemblies.Abbott, 134Julius Caesar's reforms

Caesar held both theDictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

and the Tribunate

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs acted as a check on the ...

, but alternated between the Consulship

A consul held the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic ( to 27 BC), and ancient Romans considered the consulship the second-highest level of the ''cursus honorum'' (an ascending sequence of public offices to which politic ...

and the Proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military command, or ...

ship.Abbott, 134 His powers within the state seem to have rested upon these magistracies.Abbott, 134 He was first appointed Dictator in 49 BC by the Praetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected '' magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vari ...

(and future Triumvir

A triumvirate ( la, triumvirātus) or a triarchy is a political institution ruled or dominated by three individuals, known as triumvirs ( la, triumviri). The arrangement can be formal or informal. Though the three leaders in a triumvirate are ...

) Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, possibly in order to preside over elections, but resigned his Dictatorship within eleven days. In 48 BC, he was appointed Dictator again, only this time for an indefinite period, and in 46 BC, he was appointed Dictator for ten years. In February 44 BC, one month before his assassination, he was appointed Dictator for life. The Dictatorship of Caesar was fundamentally different from the Dictatorship of the early and middle republic, as he held the office for life, rather than for six months, and he also held certain judicial powers which the ordinary Dictators had not held.Abbott, 136 Under Caesar, a significant amount of authority had been vested in both the Master of the Horse

Master of the Horse is an official position in several European nations. It was more common when most countries in Europe were monarchies, and is of varying prominence today.

(Ancient Rome)

The original Master of the Horse ( la, Magister Equitu ...

, as well as in the Urban Prefect

The ''praefectus urbanus'', also called ''praefectus urbi'' or urban prefect in English, was prefect of the city of Rome, and later also of Constantinople. The office originated under the Roman kings, continued during the Republic and Empire, and ...

, which had not been the case under earlier Dictators.Abbott, 136 They held these additional powers under Caesar, however, because Caesar was frequently out of Italy.Abbott, 136 Earlier Dictators, in contrast, were almost never allowed to leave Italy.

In October 45 BC, Caesar resigned his position as sole Consul, and facilitated the election of two successors for the remainder of the year, which, in theory at least, restored the ordinary Consulship, since the constitution did not recognize a single Consul without a colleague.Abbott, 137 However, this also set a precedent which Caesar's imperial successors followed,Abbott, 137 since under the empire, Consuls served for several months, resigned, and then the emperor facilitated the election of successors for the remainder of that Consular term. Caesar's actions, therefore, further submitted the Consuls to the Dictatorial executive. In 48 BC, Caesar was given permanent tribunician powers,Abbott, 135 which made his person sacrosanct, allowed him to veto the senate, and allowed him to dominate the Plebeian Council. Since Tribunes were always elected by the Plebeian Council, Caesar had hoped to prevent the election of Tribunes who might oppose him,Abbott, 135 although on at least one occasion, Tribunes did attempt to obstruct him. The offending Tribunes in this case, C. Epidius Marullus and L. Caesetius Flavus, were brought before the senate and divested of their office, and as such, Caesar used the same theory of popular sovereignty that Tiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus ( 163 – 133 BC) was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also served in the Roma ...

had used against Marcus Octavius

Marcus Octavius (Latin: , lived during the 2nd century BC) was a Roman tribune in 133 BC and a major rival of Tiberius Gracchus. He was a son of Gnaeus Octavius, the consul in 165 BC, and a brother to another Gnaeus Octavius, the consul in 128 ...

in 133 BC.Abbott, 135 This was not the first time that Caesar had violated a Tribune's sacrosanctity, since after he had first marched on Rome in 49 BC, he forcibly opened the Treasury in spite of a seal placed on it by a Tribune. After the impeachment of the two obstructive Tribunes, Caesar, perhaps unsurprisingly, faced no further opposition from other members of the tribunician college.Abbott, 135

In 46 BC, Caesar gave himself the title of "Prefect of the Morals" (''praefectura morum''), which was an office that was new only in name, as its powers were identical to those of the Censorship.Abbott, 135 Thus, he could hold Censorial powers, while technically not subjecting himself to the same checks that the ordinary Censors were subject to, and he used these powers to fill the senate with his own partisans. He also set the precedent, which his imperial successors followed, of requiring the senate to bestow various titles and honors upon him. He was, for example, given the title of "Father of the Fatherland" ("''pater patriae''") and "'' imperator''" (an honorary title, not to be confused with the modern title of "emperor").Abbott, 136 Coins bore his likeness, and he was given the right to speak first during senate meetings.Abbott, 136 Caesar then increased the number of magistrates who were elected each year, which created a large pool of experienced magistrates, and allowed Caesar to reward his supporters. This also weakened the powers of the individual magistrates, and thus of the magisterial colleges.Abbott, 137 Caesar even took steps to transform Italy into a province, and to more tightly link the other provinces of the empire into a single cohesive unit. This addressed the underlying problem that had caused the Social War decades earlier, where individuals outside Rome, and certainly outside Italy, were not considered "Roman", and thus were not given full citizenship rights. This process, of ossifying the entire Roman Empire into a single unit, rather than maintaining it as a network of unequal principalities, would ultimately be completed by Caesar's successor, the emperor Augustus.

Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe in conque ...

. Since his absence from Rome might limit his ability to install his own Consuls, he passed a law which allowed him to appoint all magistrates in 43 BC, and all Consuls and Tribunes in 42 BC.Abbott, 137 This, in effect, transformed the magistrates from being representatives of the people to being representatives of the Dictator,Abbott, 137 while this conferred a significant amount of political influence on himself, Caesar saw this as necessary in order to contest the domineering influence of the Senate and Equestrians within the Plebeian councils.Abbott, 137

Caesar's assassination and the Second Triumvirate

Caesar was assassinated in March 44 BC. The motives of the conspirators were both personal and political. Many of Caesar's ultimate assassins were jealous of him, and unsatisfied as to the recognition that they had received from him. Most of the conspirators were senators, and many of them were angry about the fact that he had deprived the senate of much of its power and prestige. They were also angry that, while they had received few honors, Caesar had been given many honors. There were also rumors that he was going to make himself king. The grievances that they held against him were vague, and as such, their plan against him was vague. The fact that their motives were vague, and that they had no idea of what to do after his assassination, both were plainly obvious by the subsequent course of events. After Caesar's assassination,Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the au ...

, who at the time had been Caesar's fellow consul, eventually formed an alliance with Caesar's adopted son and great-nephew, Gaius Octavian. Along with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who was Caesar's magister equity (master of horse) at the time of his assassination, they constituted an alliance known as the Second Triumvirate. They held powers that were nearly identical to the powers that Caesar had held under his constitution, and as such, the senate and assemblies remained powerless. The conspirators were defeated at the Battle of Philippi

The Battle of Philippi was the final battle in the Wars of the Second Triumvirate between the forces of Mark Antony and Octavian (of the Second Triumvirate) and the leaders of Julius Caesar's assassination, Brutus and Cassius in 42 BC, at ...

in 42 BC. Lepidus became powerless, and Antony went to Egypt to seek glory in the east, while Octavian remained in Rome. Eventually, however, Antony and Octavian fought against each other in one last battle. Antony was defeated in the naval Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between a maritime fleet of Octavian led by Marcus Agrippa and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII Philopator. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, ...

in 31 BC, and committed suicide in 30 BC. In 29 BC, Octavian returned to Rome, as the unchallenged master of the state. In 27 BC, Octavian offered to give up the Dictatorial powers which he had held since 42 BC, but the senate refused, and thus ratified his status as master of the state. He became the first Roman Emperor, Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

, and the transition from Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

to Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

was complete.

See also

*Crisis of the Roman Republic

The crisis of the Roman Republic refers to an extended period of political instability and social unrest from about 134 BC to 44 BC that culminated in the demise of the Roman Republic and the advent of the Roman Empire.

The causes and attributes ...

* Constitutional reforms of Augustus

The Constitutional reforms of Augustus were a series of laws that were enacted by the Roman Emperor Augustus between 30 BC and 2 BC, which transformed the Constitution of the Roman Republic into the Constitution of the Roman Empire. The era du ...

* Roman Law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Ju ...

* Roman consul

A consul held the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic ( to 27 BC), and ancient Romans considered the consulship the second-highest level of the ''cursus honorum'' (an ascending sequence of public offices to which politic ...

* Curia

Curia (Latin plural curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally likely had wider powers, they came ...

* Praetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected '' magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vari ...

* Quaestor

* Aedile

''Aedile'' ( ; la, aedīlis , from , "temple edifice") was an elected office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings () and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to ...

* Roman Dictator

A Roman dictator was an extraordinary magistrate in the Roman Republic endowed with full authority to resolve some specific problem to which he had been assigned. He received the full powers of the state, subordinating the other magistrates, con ...

* Master of the Horse

Master of the Horse is an official position in several European nations. It was more common when most countries in Europe were monarchies, and is of varying prominence today.

(Ancient Rome)

The original Master of the Horse ( la, Magister Equitu ...

* Roman Senate

The Roman Senate ( la, Senātus Rōmānus) was a governing and advisory assembly in ancient Rome. It was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in ...

* Cursus honorum

The ''cursus honorum'' (; , or more colloquially 'ladder of offices') was the sequential order of public offices held by aspiring politicians in the Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire. It was designed for men of senatorial rank. The '' ...

* Interrex

The interrex (plural interreges) was literally a ruler "between kings" (Latin ''inter reges'') during the Roman Kingdom and the Roman Republic. He was in effect a short-term regent.

History

The office of ''interrex'' was supposedly created follow ...

* Promagistrate

In ancient Rome a promagistrate ( la, pro magistratu) was an ex-consul or ex- praetor whose '' imperium'' (the power to command an army) was extended at the end of his annual term of office or later. They were called proconsuls and propraetors. T ...

* Acta Senatus

References

* Abbott, Frank Frost (1901). ''A History and Description of Roman Political Institutions''. Elibron Classics (). * Byrd, Robert (1995). ''The Senate of the Roman Republic''. U.S. Government Printing Office, Senate Document 103-23. * Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1841). ''The Political Works of Marcus Tullius Cicero: Comprising his Treatise on the Commonwealth; and his Treatise on the Laws. Translated from the original, with Dissertations and Notes in Two Volumes''. By Francis Barham, Esq. London: Edmund Spettigue. Vol. 1. * Lintott, Andrew (1999). ''The Constitution of the Roman Republic''. Oxford University Press (). * Polybius (1823). ''The General History of Polybius: Translated from the Greek''. By James Hampton. Oxford: Printed by W. Baxter. Fifth Edition, Vol 2. * Taylor, Lily Ross (1966). ''Roman Voting Assemblies: From the Hannibalic War to the Dictatorship of Caesar''. The University of Michigan Press ().Notes

Further reading

* Cambridge Ancient History, Volumes 9–13. * Cameron, A. ''The Later Roman Empire'', (Fontana Press, 1993). * Crawford, M. ''The Roman Republic'', (Fontana Press, 1978). * Gruen, E. S. "The Last Generation of the Roman Republic" (U California Press, 1974) * Ihne, Wilhelm. ''Researches Into the History of the Roman Constitution''. William Pickering. 1853. * Johnston, Harold Whetstone. ''Orations and Letters of Cicero: With Historical Introduction, An Outline of the Roman Constitution, Notes, Vocabulary and Index''. Scott, Foresman and Company. 1891. * Lintott, A. "The Constitution of the Roman Republic" (Oxford University Press, 1999) * Millar, F. ''The Emperor in the Roman World'', (Duckworth, 1977, 1992). * Mommsen, Theodor. ''Roman Constitutional Law''. 1871-1888 * Parenti, Michael. " The Assassination of Julius Caesar: A People's History of Ancient Rome". The New Press, 2003. . * Tighe, Ambrose. ''The Development of the Roman Constitution''. D. Apple & Co. 1886. * Von Fritz, Kurt. ''The Theory of the Mixed Constitution in Antiquity''. Columbia University Press, New York. 1975. * Polybius. ''The Histories''.Primary sources

Cicero's De Re Publica, Book Two

Secondary source material

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20080829134354/http://www.uah.edu/student_life/organizations/SAL/texts/misc/romancon.html The Roman Constitution to the Time of Cicero

What a Terrorist Incident in Ancient Rome Can Teach Us

External links

*Videos of talks byMichael Parenti

Michael John Parenti (born September 30, 1933) is an American political scientist, academic historian and cultural critic who writes on scholarly and popular subjects. He has taught at universities as well as run for political office. Parenti i ...

, about his book " The Assassination of Julius Caesar: A People's History of Ancient Rome", which explains how wealthy and conservative elites killed Caesar to end his egalitarian reforms: 76 minute talin 1 part

an

in 8 parts

{{Ancient Rome topics Julius Caesar Roman Republic Roman law 40s BC 1st century BC in the Roman Republic Reform in the Roman Republic