British Army during the Second World War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

At the start of 1939, the

The 1939 infantry division had a theoretical establishment of 13,863 men. By 1944, the strength had risen to 18,347 men.Brayley & Chappell (2001), p.17 This increase in manpower resulted mainly from the increased establishment of a division's subunits and formations; except for certain specialist supporting services, the overall structure remained substantially the same throughout the war. A 1944 division typically was made up of three infantry brigades; a Medium Machine Gun (MMG) battalion (with 36

The 1939 infantry division had a theoretical establishment of 13,863 men. By 1944, the strength had risen to 18,347 men.Brayley & Chappell (2001), p.17 This increase in manpower resulted mainly from the increased establishment of a division's subunits and formations; except for certain specialist supporting services, the overall structure remained substantially the same throughout the war. A 1944 division typically was made up of three infantry brigades; a Medium Machine Gun (MMG) battalion (with 36

At the start of the war, the British Army possessed only two armoured divisions: the Mobile Division, formed in Britain in October 1937, and the Mobile Division (Egypt), formed in the autumn of 1938 following the

At the start of the war, the British Army possessed only two armoured divisions: the Mobile Division, formed in Britain in October 1937, and the Mobile Division (Egypt), formed in the autumn of 1938 following the  In late 1940, following the campaign in France and Belgium in the spring, it was realised that there were insufficient infantry and support units, and mixing light and cruiser tanks in the same brigade had been a mistake. The armoured divisions' organisation was changed so that each armoured brigade now incorporated a motorised infantry battalion, and a third battalion was present within the Support Group.

In the winter of 1940–41, new armoured regiments were formed by converting the remaining mounted

In late 1940, following the campaign in France and Belgium in the spring, it was realised that there were insufficient infantry and support units, and mixing light and cruiser tanks in the same brigade had been a mistake. The armoured divisions' organisation was changed so that each armoured brigade now incorporated a motorised infantry battalion, and a third battalion was present within the Support Group.

In the winter of 1940–41, new armoured regiments were formed by converting the remaining mounted  In 1944, the division's armoured regiments comprised 78 tanks. The regimental headquarters was equipped with four medium tanks, an anti–aircraft troop with eight Crusader Anti–Aircraft tanks, and the regiment's reconnaissance troop with eleven Stuart tanks.Taylor, p.6 Each regiment also had three Sabre squadrons; generally comprising four

In 1944, the division's armoured regiments comprised 78 tanks. The regimental headquarters was equipped with four medium tanks, an anti–aircraft troop with eight Crusader Anti–Aircraft tanks, and the regiment's reconnaissance troop with eleven Stuart tanks.Taylor, p.6 Each regiment also had three Sabre squadrons; generally comprising four

The Royal Artillery was a large corps, responsible for the provision of field, medium, heavy, mountain, anti-tank and anti-aircraft units. (Some field regiments, particularly self-propelled regiments in the later part of the war, belonged to the prestigious

The Royal Artillery was a large corps, responsible for the provision of field, medium, heavy, mountain, anti-tank and anti-aircraft units. (Some field regiments, particularly self-propelled regiments in the later part of the war, belonged to the prestigious

The first raiding forces formed during the war were the ten

The first raiding forces formed during the war were the ten

The British tank force consisted of the slow and heavily armed

The British tank force consisted of the slow and heavily armed

In April, more reinforcements arrived of two further Territorial divisions. These were the 42nd (East Lancashire) and 44th (Home Counties) Infantry Divisions. A further three Territorial divisions, all 2nd Line and poorly trained and without their supporting artillery, engineer and signals units, arrived later in the same month. They were the 12th (Eastern), 23rd (Northumbrian) and 46th Infantry Divisions and had been sent to France on labour duties. In May, elements of the 1st Armoured Division also arrived.

The German Army invaded in the West on 10 May 1940, by that time BEF consisted of 10 divisions, a tank brigade and a detachment of 500 aircraft from the RAF. During the

In April, more reinforcements arrived of two further Territorial divisions. These were the 42nd (East Lancashire) and 44th (Home Counties) Infantry Divisions. A further three Territorial divisions, all 2nd Line and poorly trained and without their supporting artillery, engineer and signals units, arrived later in the same month. They were the 12th (Eastern), 23rd (Northumbrian) and 46th Infantry Divisions and had been sent to France on labour duties. In May, elements of the 1st Armoured Division also arrived.

The German Army invaded in the West on 10 May 1940, by that time BEF consisted of 10 divisions, a tank brigade and a detachment of 500 aircraft from the RAF. During the  In the North African Campaign, the Italian invasion of Egypt, started in September 1940.Taylor (1976), p.83 The

In the North African Campaign, the Italian invasion of Egypt, started in September 1940.Taylor (1976), p.83 The

Operation Compass was a success and the Western Desert Force advanced across

Operation Compass was a success and the Western Desert Force advanced across  The followup to Brevity was Operation Battleaxe, involving the 7th Armoured Division, 22nd Guards Brigade and 4th Indian Infantry Division from XIII Corps commanded by Lieutenant-General Noel Beresford-Peirse. Battleaxe was also a failure, and with the British forces defeated, Churchill wanted a change in command, so Wavell exchanged places with General Claude Auchinleck, as

The followup to Brevity was Operation Battleaxe, involving the 7th Armoured Division, 22nd Guards Brigade and 4th Indian Infantry Division from XIII Corps commanded by Lieutenant-General Noel Beresford-Peirse. Battleaxe was also a failure, and with the British forces defeated, Churchill wanted a change in command, so Wavell exchanged places with General Claude Auchinleck, as  The

The  The Syria-Lebanon Campaign was the invasion of Vichy France, Vichy French controlled Syria and Lebanon in June–July 1941. The British and Commonwealth forces involved were the 1st Cavalry Division (United Kingdom), British 1st Cavalry Division, British 6th Infantry Division, 7th Division (Australia), 7th Australian Division, 1st Free French Division and the 10th Indian Infantry Division.

The Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in August–September by British, Dominion and

The Syria-Lebanon Campaign was the invasion of Vichy France, Vichy French controlled Syria and Lebanon in June–July 1941. The British and Commonwealth forces involved were the 1st Cavalry Division (United Kingdom), British 1st Cavalry Division, British 6th Infantry Division, 7th Division (Australia), 7th Australian Division, 1st Free French Division and the 10th Indian Infantry Division.

The Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in August–September by British, Dominion and

In the Far East, Malaya Command defended stubbornly but was gradually pushed back, until the battle of Singapore, which Surrender (military), surrendered on 15 February 1942. About 100,000 British and Commonwealth troops became prisoners of war during the Malayan Campaign, Battle of Malaya.Hack & Blackburn (2004), p.92 Winston Churchill called the fall of Singapore the "worst disaster" and "largest capitulation" in British history. The Japanese conquest of Burma started in January. It was soon apparent that the British and Indian troops in the Burma Campaign were too few in number, wrongly equipped and inadequately trained for the terrain and conditions. The force of about 60,000 troops retreated , and reached Assam in British Raj, India in May.Taylor (1976), p.135 In spite of their difficulties, the British mounted a small scale offensive into the coastal Arakan State, Arakan region of Burma, in December.Taylor (1976), p.168 The offensive under General Noel Irwin was intended to reoccupy the Mayu peninsula and Akyab, Akyab Island. The 14th Indian Infantry Division had advanced to Donbaik, only a few miles from the end of the peninsula, when they were halted by a smaller Japanese force and the offensive was a total failure.

In the Far East, Malaya Command defended stubbornly but was gradually pushed back, until the battle of Singapore, which Surrender (military), surrendered on 15 February 1942. About 100,000 British and Commonwealth troops became prisoners of war during the Malayan Campaign, Battle of Malaya.Hack & Blackburn (2004), p.92 Winston Churchill called the fall of Singapore the "worst disaster" and "largest capitulation" in British history. The Japanese conquest of Burma started in January. It was soon apparent that the British and Indian troops in the Burma Campaign were too few in number, wrongly equipped and inadequately trained for the terrain and conditions. The force of about 60,000 troops retreated , and reached Assam in British Raj, India in May.Taylor (1976), p.135 In spite of their difficulties, the British mounted a small scale offensive into the coastal Arakan State, Arakan region of Burma, in December.Taylor (1976), p.168 The offensive under General Noel Irwin was intended to reoccupy the Mayu peninsula and Akyab, Akyab Island. The 14th Indian Infantry Division had advanced to Donbaik, only a few miles from the end of the peninsula, when they were halted by a smaller Japanese force and the offensive was a total failure.

In North Africa the Axis forces attacked in May, defeating the Allies in the Battle of Gazala in June and capturing Tobruk and 35,000 prisoners. The Eighth Army retreated over the Egyptian border, where the German advance was stopped in the First Battle of El Alamein.

In North Africa the Axis forces attacked in May, defeating the Allies in the Battle of Gazala in June and capturing Tobruk and 35,000 prisoners. The Eighth Army retreated over the Egyptian border, where the German advance was stopped in the First Battle of El Alamein.  On 8 November in French North Africa, Operation Torch was launched.Taylor (1976), p.159 The British part of the Eastern Task force, landed at Algiers. The task force, commanded by Lieutenant-General Kenneth Anderson (British Army officer), Kenneth Anderson, consisted of two brigades from the 78th Infantry Division (United Kingdom), British 78th Infantry Division, the 34th Infantry Division (United States), U.S. 34th Infantry Division and the No. 1 Commando, 1st and No. 6 Commando, 6th Commando Battalions. The Tunisian Campaign started with the Eastern Task Force, now redesignated First Army, and composed of the British 78th Infantry Division, 6th Armoured Division (United Kingdom), 6th Armoured Division, 1st Parachute Brigade (United Kingdom), British 1st Parachute Brigade, No. 6 Commando and elements of the 1st Armored Division (United States), U.S. 1st Armored Division. However, the advance was stopped by the reinforced Axis forces, and forced back having failed in the Run for Tunis.

On 8 November in French North Africa, Operation Torch was launched.Taylor (1976), p.159 The British part of the Eastern Task force, landed at Algiers. The task force, commanded by Lieutenant-General Kenneth Anderson (British Army officer), Kenneth Anderson, consisted of two brigades from the 78th Infantry Division (United Kingdom), British 78th Infantry Division, the 34th Infantry Division (United States), U.S. 34th Infantry Division and the No. 1 Commando, 1st and No. 6 Commando, 6th Commando Battalions. The Tunisian Campaign started with the Eastern Task Force, now redesignated First Army, and composed of the British 78th Infantry Division, 6th Armoured Division (United Kingdom), 6th Armoured Division, 1st Parachute Brigade (United Kingdom), British 1st Parachute Brigade, No. 6 Commando and elements of the 1st Armored Division (United States), U.S. 1st Armored Division. However, the advance was stopped by the reinforced Axis forces, and forced back having failed in the Run for Tunis.

In May to prevent Japanese naval forces capturing Vichy French controlled Madagascar, the Battle of Madagascar was launched.

The 5th Infantry Division (United Kingdom), British 5th Infantry Division (minus the 15th Infantry Brigade), as well as the 29th Infantry Brigade (United Kingdom), 29th Independent Infantry Brigade Group, and commandos were landed at Courrier Bay and Ambararata Bay, west of the major port of Antsiranana, Diego Suarez, on the northern tip of Madagascar. The Allies eventually captured the capital, Tananarive, without much opposition, and then the town of Ambalavao. The last major action was at Andramanalina on 18 October, and the Vichy France, Vichy French forces surrendered near Ihosy on 8 November.

In May to prevent Japanese naval forces capturing Vichy French controlled Madagascar, the Battle of Madagascar was launched.

The 5th Infantry Division (United Kingdom), British 5th Infantry Division (minus the 15th Infantry Brigade), as well as the 29th Infantry Brigade (United Kingdom), 29th Independent Infantry Brigade Group, and commandos were landed at Courrier Bay and Ambararata Bay, west of the major port of Antsiranana, Diego Suarez, on the northern tip of Madagascar. The Allies eventually captured the capital, Tananarive, without much opposition, and then the town of Ambalavao. The last major action was at Andramanalina on 18 October, and the Vichy France, Vichy French forces surrendered near Ihosy on 8 November.

The First and the Eighth Armies attacked in March (Battle of the Mareth Line, Operation Pugilist) and April (Operation Vulcan). Hard fighting followed, and the Axis supply line was cut between Tunisia and Sicily. On 6 May, during Operation Vulcan, the British took Tunis, and American forces reached Bizerte. By 13 May the Axis forces in Tunisia had surrendered, leaving 230,000 prisoners behind.

The First and the Eighth Armies attacked in March (Battle of the Mareth Line, Operation Pugilist) and April (Operation Vulcan). Hard fighting followed, and the Axis supply line was cut between Tunisia and Sicily. On 6 May, during Operation Vulcan, the British took Tunis, and American forces reached Bizerte. By 13 May the Axis forces in Tunisia had surrendered, leaving 230,000 prisoners behind.

The Italian Campaign followed the Axis surrender in North Africa, first the Allied invasion of Sicily in July, followed by the

The Italian Campaign followed the Axis surrender in North Africa, first the Allied invasion of Sicily in July, followed by the  On 3 September Montgomery's Eighth Army Operation Baytown, landed on the toe of Italy directly opposite Messina, and Italy surrendered on 8 September. The main landing of Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark's United States Army North, U.S. Fifth Army, with the X Corps (United Kingdom), British X Corps under Lieutenant-General

On 3 September Montgomery's Eighth Army Operation Baytown, landed on the toe of Italy directly opposite Messina, and Italy surrendered on 8 September. The main landing of Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark's United States Army North, U.S. Fifth Army, with the X Corps (United Kingdom), British X Corps under Lieutenant-General  The Dodecanese Campaign was an attempt by the British to liberate the Italian held Dodecanese islands in the Aegean Sea following the surrender of Italy, and use them as bases against the German controlled Balkans. The effort failed, with the whole of the Dodecanese falling to the Germans within two months, and the Allies suffering heavy losses in men and ships.Zabecki (1999) pp.1452–1455 (see Battle of Kos and Battle of Leros for further details).

The Dodecanese Campaign was an attempt by the British to liberate the Italian held Dodecanese islands in the Aegean Sea following the surrender of Italy, and use them as bases against the German controlled Balkans. The effort failed, with the whole of the Dodecanese falling to the Germans within two months, and the Allies suffering heavy losses in men and ships.Zabecki (1999) pp.1452–1455 (see Battle of Kos and Battle of Leros for further details).

In Burma, Brigadier (United Kingdom), Brigadier Orde Wingate, and the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, or the Chindits as they were better known, infiltrated the Japanese lines in February, marched deep into Burma in Operation Longcloth. The initial aim was to cut the main North–South railway in Burma. Some 3,000 men entered Burma in columns and caused some damage Japanese communications, and cut the railway. But by the end of April, the surviving Chindits had crossed back over the Chindwin river, having marched between 750 and 1000 miles.Brayley (2002), p.19 Of the 3,000 men that had begun the operation, 818 men had been killed, taken prisoner or died of disease, and of the 2,182 men who returned, about 600 were too debilitated from their wounds or disease to return to active service.

In Burma, Brigadier (United Kingdom), Brigadier Orde Wingate, and the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, or the Chindits as they were better known, infiltrated the Japanese lines in February, marched deep into Burma in Operation Longcloth. The initial aim was to cut the main North–South railway in Burma. Some 3,000 men entered Burma in columns and caused some damage Japanese communications, and cut the railway. But by the end of April, the surviving Chindits had crossed back over the Chindwin river, having marched between 750 and 1000 miles.Brayley (2002), p.19 Of the 3,000 men that had begun the operation, 818 men had been killed, taken prisoner or died of disease, and of the 2,182 men who returned, about 600 were too debilitated from their wounds or disease to return to active service.

The 21st Army Group, under

The 21st Army Group, under  On 17 September, Operation Market Garden began. XXX Corps (United Kingdom), British XXX Corps, under Lieutenant-General

On 17 September, Operation Market Garden began. XXX Corps (United Kingdom), British XXX Corps, under Lieutenant-General  In an effort to use the port of Antwerp, the Canadian First Army including Lieutenant-General

In an effort to use the port of Antwerp, the Canadian First Army including Lieutenant-General  During the Allied campaign in Italy, some of the hardest fighting of the entire war now took place. This was not helped by the withdrawal of forces for the Allied landings in Northern France.Taylor (1976), p.190 Operations carried out included: the long stalemate on the Winter Line (also known as the Gustav Line), and the hard-fought Battle of Monte Cassino. In January, the Battle of Anzio, Anzio landings, codenamed Operation Shingle, were an attempt to bypass the Gustav Line by sea. (see Anzio order of battle for British forces involved). Landing almost unopposed, with the road to the Italian capital of Rome open, the VI Corps (United States), U.S. VI Corps commander, Major general (United States), Major General John P. Lucas, felt that he needed to consolidate the beachhead before breaking out.Taylor (1976), p.191 This gave the Germans time to concentrate their forces against him. Another stalemate ensued, with the combined Anglo-American force facing stiff resistance, suffering severe losses and almost being driven back into the sea. When the stalemate was finally broken in the spring of 1944, with the launching of Operation Diadem, they advanced towards Rome, instead of heading north east to block the line of the German retreat from Cassino, thus prolonging the campaign in Italy. Progress was rapid, however, and, in August, the Allies came up against the Gothic Line and, by December, had reached Ravenna.

During the Allied campaign in Italy, some of the hardest fighting of the entire war now took place. This was not helped by the withdrawal of forces for the Allied landings in Northern France.Taylor (1976), p.190 Operations carried out included: the long stalemate on the Winter Line (also known as the Gustav Line), and the hard-fought Battle of Monte Cassino. In January, the Battle of Anzio, Anzio landings, codenamed Operation Shingle, were an attempt to bypass the Gustav Line by sea. (see Anzio order of battle for British forces involved). Landing almost unopposed, with the road to the Italian capital of Rome open, the VI Corps (United States), U.S. VI Corps commander, Major general (United States), Major General John P. Lucas, felt that he needed to consolidate the beachhead before breaking out.Taylor (1976), p.191 This gave the Germans time to concentrate their forces against him. Another stalemate ensued, with the combined Anglo-American force facing stiff resistance, suffering severe losses and almost being driven back into the sea. When the stalemate was finally broken in the spring of 1944, with the launching of Operation Diadem, they advanced towards Rome, instead of heading north east to block the line of the German retreat from Cassino, thus prolonging the campaign in Italy. Progress was rapid, however, and, in August, the Allies came up against the Gothic Line and, by December, had reached Ravenna.

The Burma Campaign 1944, 1944 campaign in Burma started with Chindits, Operation Thursday, a Chindit force now designated 3rd Indian Infantry Division, were tasked with disrupting the Japanese lines of supply to the northern front. Further South the Battle of the Admin Box started in February, in preparation for when the Japanese Operation U-Go offensive. Although total Allied casualties were higher than the Japanese, the Japanese were forced to abandon many of their wounded. This was the first time that British and Indian troops had held and defeated a major Japanese attack.Allen (1984), pp.187–188 This victory was repeated on a larger scale in the Battle of Imphal (March–July) and the Battle of Kohima (April–June), giving the Japanese their largest defeat on land during the war.Taylor (1976), p.210 From August to November, the Fourteenth Army, under Lieutenant-General William Slim, 1st Viscount Slim, William Slim, pushed the Japanese back to the Chindwin River.

The Burma Campaign 1944, 1944 campaign in Burma started with Chindits, Operation Thursday, a Chindit force now designated 3rd Indian Infantry Division, were tasked with disrupting the Japanese lines of supply to the northern front. Further South the Battle of the Admin Box started in February, in preparation for when the Japanese Operation U-Go offensive. Although total Allied casualties were higher than the Japanese, the Japanese were forced to abandon many of their wounded. This was the first time that British and Indian troops had held and defeated a major Japanese attack.Allen (1984), pp.187–188 This victory was repeated on a larger scale in the Battle of Imphal (March–July) and the Battle of Kohima (April–June), giving the Japanese their largest defeat on land during the war.Taylor (1976), p.210 From August to November, the Fourteenth Army, under Lieutenant-General William Slim, 1st Viscount Slim, William Slim, pushed the Japanese back to the Chindwin River.

In Germany the 21st Army Group offensive towards the Rhine began in February. The Second Army pinned down the Germans, while the Canadian First and the Ninth United States Army, U.S. Ninth Army made pincer movements piercing the Siegfried Line. On 23 March, the Second Army crossed the Rhine, supported by a large airborne assault (Operation Varsity) the following day. The British advanced onto the North German Plain, heading towards the Baltic sea. The Elbe was crossed by VIII Corps, under Lieutenant-General

In Germany the 21st Army Group offensive towards the Rhine began in February. The Second Army pinned down the Germans, while the Canadian First and the Ninth United States Army, U.S. Ninth Army made pincer movements piercing the Siegfried Line. On 23 March, the Second Army crossed the Rhine, supported by a large airborne assault (Operation Varsity) the following day. The British advanced onto the North German Plain, heading towards the Baltic sea. The Elbe was crossed by VIII Corps, under Lieutenant-General  In the Italian campaign, the poor winter weather and the massive losses in its ranks, sustained during the autumn fighting, halted any advance until the spring. The Spring 1945 offensive in Italy commenced after a heavy artillery bombardment on 9 April. By 18 April, the Eighth Army, now commanded by Lieutenant-General Richard McCreery, Sir Richard McCreery, had broken through the Argenta Gap and captured Bologna on 21 April. The 8th Infantry Division (India), 8th Indian Infantry Division, reached the Po (river), Po River on 23 April. The British V Corps, under Lieutenant-General Charles Keightley, traversed the Venetian Line and entered Padua in the early hours of 29 April, to find that partisans had locked up the German garrison of 5,000 men.Blaxland (1979), p.277 The Axis forces, retreating on all fronts and having lost most of its fighting power, was left with little option but surrender. General Heinrich von Vietinghoff, signed the surrender on behalf of the German armies in Italy on 29 April formally bringing hostilities to an end on 2 May 1945.

In the Italian campaign, the poor winter weather and the massive losses in its ranks, sustained during the autumn fighting, halted any advance until the spring. The Spring 1945 offensive in Italy commenced after a heavy artillery bombardment on 9 April. By 18 April, the Eighth Army, now commanded by Lieutenant-General Richard McCreery, Sir Richard McCreery, had broken through the Argenta Gap and captured Bologna on 21 April. The 8th Infantry Division (India), 8th Indian Infantry Division, reached the Po (river), Po River on 23 April. The British V Corps, under Lieutenant-General Charles Keightley, traversed the Venetian Line and entered Padua in the early hours of 29 April, to find that partisans had locked up the German garrison of 5,000 men.Blaxland (1979), p.277 The Axis forces, retreating on all fronts and having lost most of its fighting power, was left with little option but surrender. General Heinrich von Vietinghoff, signed the surrender on behalf of the German armies in Italy on 29 April formally bringing hostilities to an end on 2 May 1945.

In Burma the Battle of Meiktila and Mandalay started in January, despite logistical difficulties, the British were able to deploy large armoured forces in Central Burma. Most of the Japanese forces in Burma were destroyed during the battles, allowing the Allies to capture the capital, Rangoon on 2 May. The British Army fought its last pitched land battle of the war when the remaining Japanese Battle of the Sittang Bend, attempted to break out eastwards in July, to join other troops retreating from the British. The breakout however ending in early August, resulted with a crushing defeat for the Japanese, with some formations being wiped out. The Japanese were still in control of Malaya but they surrendered on 14 August along with Hong Kong.

In Burma the Battle of Meiktila and Mandalay started in January, despite logistical difficulties, the British were able to deploy large armoured forces in Central Burma. Most of the Japanese forces in Burma were destroyed during the battles, allowing the Allies to capture the capital, Rangoon on 2 May. The British Army fought its last pitched land battle of the war when the remaining Japanese Battle of the Sittang Bend, attempted to break out eastwards in July, to join other troops retreating from the British. The breakout however ending in early August, resulted with a crushing defeat for the Japanese, with some formations being wiped out. The Japanese were still in control of Malaya but they surrendered on 14 August along with Hong Kong.

On 29 November 1945, the British Government stated that for the period of 3 September 1939 – 14 August 1945, the empire suffered a total of 1,246,025 casualties, with 755,257 of these casualties being from the United Kingdom. Of these, the British military suffered 244,723 killed, 53,039 reported missing, 277,090 wounded, and 180,405 men were taken as prisoners of war. This report included men from Newfoundland and Southern Rhodesia within the British figure, but did not break down the losses by service branch. In 1961, the House of Lords reported that the British Army (including men from Newfoundland and Southern Rhodesia) suffered a total of 569,501 casualties between 3 September 1939 and 14 August 1946, and as reported up to 28 February 1946. This figure included 144,079 killed, 33,771 missing, 239,575 wounded, and 152,076 captured.

On 29 November 1945, the British Government stated that for the period of 3 September 1939 – 14 August 1945, the empire suffered a total of 1,246,025 casualties, with 755,257 of these casualties being from the United Kingdom. Of these, the British military suffered 244,723 killed, 53,039 reported missing, 277,090 wounded, and 180,405 men were taken as prisoners of war. This report included men from Newfoundland and Southern Rhodesia within the British figure, but did not break down the losses by service branch. In 1961, the House of Lords reported that the British Army (including men from Newfoundland and Southern Rhodesia) suffered a total of 569,501 casualties between 3 September 1939 and 14 August 1946, and as reported up to 28 February 1946. This figure included 144,079 killed, 33,771 missing, 239,575 wounded, and 152,076 captured.

online

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Online free

* Snape, Michael. ''God and the British soldier: Religion and the British army in the First and Second World Wars'' (Routledge, 2007). * Vernon, P. and J. B. Parry. ''Personnel Selection in the British Forces'' (HMSO, 1949), official history. * Williams, Philip Hamlyn. ''War on Wheels: The Mechanisation of the British Army in the Second World War'' (2016). * Wylie, Neville. ''Barbed Wire Diplomacy: Britain, Germany, and the Politics of Prisoners of War 1939-1945'' (Oxford UP, 2010).

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

was, as it traditionally always had been, a small volunteer professional army. At the beginning of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

on 1 September 1939, the British Army was small in comparison with those of its enemies, as it had been at the beginning of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1914. It also quickly became evident that the initial structure and manpower of the British Army was woefully unprepared and ill-equipped for a war with multiple enemies on multiple fronts. During the early war years, mainly from 1940 to 1942, the British Army suffered defeat in almost every theatre of war

In warfare, a theater or theatre is an area in which important military events occur or are in progress. A theater can include the entirety of the airspace, land and sea area that is or that may potentially become involved in war operations.

T ...

in which it was deployed. But, from late 1942 onwards, starting with the Second Battle of El Alamein

The Second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 11 November 1942) was a battle of the Second World War that took place near the Egyptian Railway station, railway halt of El Alamein. The First Battle of El Alamein and the Battle of Alam el Halfa ...

, the British Army's fortunes changed and it rarely suffered another defeat.

While there are a number of reasons for this shift, not least the entrance of both the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

in 1941, as well as the cracking of the Enigma code that same year, an important factor was the stronger British Army. This included better equipment, leadership, training, better military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from a ...

and mass conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

that allowed the army to expand to form larger armies

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

and army group

An army group is a military organization consisting of several field armies, which is self-sufficient for indefinite periods. It is usually responsible for a particular geographic area. An army group is the largest field organization handled by ...

s, as well as create new specialist formations such as the Special Air Service

The Special Air Service (SAS) is a special forces unit of the British Army. It was founded as a regiment in 1941 by David Stirling and in 1950, it was reconstituted as a corps. The unit specialises in a number of roles including counter-terro ...

(SAS), Special Boat Service

The Special Boat Service (SBS) is the special forces unit of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy. The SBS can trace its origins back to the Second World War when the Army Special Boat Section was formed in 1940. After the Second World War, the Roya ...

(SBS), Commandos

Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin">40_Commando.html" ;"title="Royal Marines from 40 Commando">Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin area of Afghanistan are pictured

A commando is a combatant, or operativ ...

and the Parachute Regiment. During the course of the war, eight men would be promoted to the rank of Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

, the army's highest rank.

By the end of the Second World War in September 1945, over 3.5 million men and women had served in the British Army, which had suffered around 720,000 casualties throughout the conflict.

Background

The main British Army campaigns in the course of the Second World War

The British Army was called on to fight around the world, starting with campaigns in Europe in 1940. After theDunkirk evacuation

The Dunkirk evacuation, codenamed Operation Dynamo and also known as the Miracle of Dunkirk, or just Dunkirk, was the evacuation of more than 338,000 Allied soldiers during the Second World War from the beaches and harbour of Dunkirk, in the ...

of Allied Forces from France (May–June 1940), the army fought in the Mediterranean and Middle East theatres, and in the Burma Campaign. After a series of setbacks, retreats and evacuations, the British Army and its Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

eventually gained the upper hand. This began with victory in the Tunisian Campaign

The Tunisian campaign (also known as the Battle of Tunisia) was a series of battles that took place in Tunisia during the North African campaign of the Second World War, between Axis and Allied forces from 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943. The ...

in North Africa in May 1943, followed by Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

being forced to surrender after the invasions of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and the Italian mainland in 1943. In 1944 the British Army returned to France and with its Allies drove the German Army

The German Army (, "army") is the land component of the armed forces of Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German ''Bundeswehr'' together with the ''Marine'' (German Navy) and the ''Luftwaf ...

back into Germany. Meanwhile, in East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea and ...

the Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

Army were driven back by the Allies from the Indian border into eastern Burma. In 1945 both the German and Japanese Armies were defeated and surrendered within months of each other.

Impact of the First World War

High losses had been sustained by the British Army during theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and many soldiers returned embittered by their experiences. The British people had also suffered economic hardships after the war and with the onset of the Great Depression in the 1930s had contributed to a widespread antipathy to involvement in another war. One of the results was the adoption of a doctrine of casualty avoidance, as the British Army knew that British society, and the soldiers themselves, would never again allow them to recklessly throw away lives. The British Army had analysed the lessons of the First World War and developed them into an inter-war doctrine

Doctrine (from la, doctrina, meaning "teaching, instruction") is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a belief system ...

, at the same time trying to predict how advances in weapons and technology might affect any future war. Developments were constrained by the Treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or in p ...

. In 1919, the Ten Year Rule

The Ten Year Rule was a British government guideline, first adopted in August 1919, that the armed forces should draft their estimates "on the assumption that the British Empire would not be engaged in any great war during the next ten years".

The ...

was introduced, which stipulated that the British Armed Forces

The British Armed Forces, also known as His Majesty's Armed Forces, are the military forces responsible for the defence of the United Kingdom, its Overseas Territories and the Crown Dependencies. They also promote the UK's wider interests, s ...

should draft their estimates "on the assumption that the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

would not be engaged in any great war during the next ten years". In 1928, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, who was Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

from 6 November 1924 to 4 June 1929 (and who later became Prime Minister), successfully urged the British Government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_es ...

to make the Rule self-perpetuating so that it was in force unless specifically countermanded (Cabinet abandoned the rule in 1932)

In the 1920s, and much of the 1930s, the General Staff tried to establish a small mechanized professional army, using the Experimental Mechanized Force

The Experimental Mechanized Force (EMF) was a brigade-sized formation of the British Army. It was officially formed on 1 May 1927 to investigate and develop the techniques and equipment required for armoured warfare and was the first armoured fo ...

as a prototype. The structure of the British Army had been organized to sacrifice firepower for mobility and removed from its commanders the fire support weapons that were needed to advance over the battlefield.French (2000), p.12 The army had been equipped and trained to win quick victories using superior mechanised mobility and technology rather than manpower. It also adopted a conservative tendency to consolidate gains on the battlefield rather than aggressively exploiting successes. However, with the lack of any identified threat, the Army's main function was to garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mil ...

the British Empire.

During this time, the army suffered from a lack of funding. The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, being the first line of defence, received the major proportion of the defence budget.Buell, Bradley, Dice & Griess (2002), p.42 Second priority was the creation of a bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching aerial torpedo, torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped ...

force for the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF) to retaliate against the expected attacks on British cities. The development of radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

in 1935, which had the ability to track enemy aircraft, resulted in additional funding being provided for the RAF to build a fighter aircraft force. The army's shortage of funds, and no requirement for large armoured forces to police the Empire, was reflected in the fact that no large-scale armoured formations were formed until 1938. The effectiveness of the British Army was also hampered by the doctrine of casualty avoidance.

Alan Brooke

Field Marshal Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke, (23 July 1883 – 17 June 1963), was a senior officer of the British Army. He was Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), the professional head of the British Army, during the Sec ...

the CIGS from November 1941 complained several times in the earlier entries in his private diary about the lack of suitable officers for command positions, which he puts down to high losses in the First World War

*It is lamentable how poor we are regards Army and Corps Commanders. We ought to remove several, but heaven knows where we shall find anything much better. Postwar addition: This shortage of real leaders was a constant source of anxiety to me during the war. I came to the conclusion that it was due to the cream of the manhood having been lost in the First World War. It was the real leaders, in the shape of platoon, company and battalion commanders, who were killed off. These were the men we were short of now. I found this shortage of leaders of quality applied to all three fighting services, and later I was able to observe that the same failing prevailed among politician and diplomats. (8 October 1941)

*Most of the morning was spent sorting out and adjusting senior officers .... There were at least 3 Corps Commanders that must be changed, and possibly 4! …. The dearth of suitable higher commanders is lamentable. I cannot quite make out to what it must be attributed. The only thing I feel can account for it is the fact that the flower of our manhood was wiped out some 20 years ago and it is just some of those that we lost then that we require now.(23 October 1941)

* Furthermore (the situation) is made worse by the lack of good military commanders. Half our Corps and Divisional Commanders are totally unfit for their appointments, and yet if I were to sack them I could find no better! They lack character, imagination, drive and power of leadership. The reason for this state of affairs is to be found in the losses we sustained in the last war of all our best officers, who should now be our senior commanders. I wonder if we shall muddle through this time .... (31 March 1942)

Organisation

Second World War

At the outbreak of the Second World War, only two armoured divisions (the 1st and7th

7 (seven) is the natural number following 6 and preceding 8. It is the only prime number preceding a cube (algebra), cube.

As an early prime number in the series of positive integers, the number seven has greatly symbolic associations in religion ...

) had been formed, in comparison to the seven armoured divisions of the German Army. In September 1939, the British Army had a total of 892,697 officers and men in both the full-time regular army and part-time Territorial Army (TA). The regular army could muster 224,000 men, who were supported by a reserve of 173,700 men. Of the regular army reservists, only 3,700 men were fully trained and the remainder had been in civilian life for up to 13 years. In April 1939, an additional 34,500 men had been conscripted into the regular army and had only completed their basic training on the eve of war.French (2000), p.64 The regular army was built around 30 cavalry or armoured regiments and 140 infantry battalions. The Territorial Army numbered 438,100, with a reserve of around 20,750 men. This force comprised 29 yeomanry

Yeomanry is a designation used by a number of units or sub-units of the British Army, British Army Reserve (United Kingdom), Army Reserve, descended from volunteer British Cavalry, cavalry regiments. Today, Yeomanry units serve in a variety of ...

regiments (eight of which were still to be fully mechanized), 12 tank and 232 infantry battalions.Perry (1988), p.49

In May 1939 the ''Military Training Act 1939

The Military Training Act 1939 was an Act of Parliament passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom on 26 May 1939, in a period of international tension that led to World War II. The Act applied to males aged 20 and 21 years old who were to be c ...

'' introduced limited conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

to meet the growing threat of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. The Act required all men aged between 20 and 22 years to do six months of military training. When the UK declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, the ''National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939

The National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939 was enacted by the Parliament of the United Kingdom on 3 September 1939, the day the United Kingdom declared war on Germany at the start of the Second World War. It superseded the Military Training Act ...

'' was rushed through Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

that required all fit men between the ages of 18 and 41 years to register for training (except for those in exempted industries and occupations).

By the end of 1939 the British Army's size had risen to 1.1 million men. By June 1940 it stood at 1.65 million men and had further increased to 2.2 million men by June 1941. The size of the British Army peaked in June 1945, at 2.9 million men. By the end of the Second World War some three million people had served.

In 1944, the United Kingdom was facing severe manpower shortages. By May 1944, it was estimated that the British Army's strength in December 1944 would be 100,000 less than it was at the end of 1943. Although casualties in the Normandy Campaign

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norma ...

, the main effort of the British Army in 1944, were actually lower than anticipated, losses from all causes were still higher than could be replaced. Two infantry divisions and a brigade ( 59th and 50th divisions and 70th Brigade) were disbanded to provide replacements for other British divisions in the 21st Army Group

The 21st Army Group was a British headquarters formation formed during the Second World War. It controlled two field armies and other supporting units, consisting primarily of the British Second Army and the First Canadian Army. Established in ...

and all men being called up to the Army were trained as infantrymen. Furthermore, 35,000 men from the RAF Regiment and the Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

were transferred to the infantry and were retrained as rifle infantrymen, where the majority of combat casualties fell. In addition, in the Eighth Army fighting in the Italian Campaign of the Mediterranean theatre several units, mainly infantry, were also disbanded to provide replacements, including the 1st Armoured Division and several other smaller units, such as the 168th Brigade, had to be reduced to cadre

Cadre may refer to:

*Cadre (military), a group of officers or NCOs around whom a unit is formed, or a training staff

*Cadre (politics), a politically controlled appointment to an institution in order to circumvent the state and bring control to th ...

, and several other units had to be amalgamated. For example, the 2nd and 6th battalions of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers

The Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers was an Irish line infantry regiment of the British Army in existence from 1881 until 1968. The regiment was formed in 1881 by the amalgamation of the 27th (Inniskilling) Regiment of Foot and the 108th Regiment o ...

were merged in August 1944. At the same time, most infantry battalions in Italy had to be reduced from four to three rifle companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared go ...

.

The pre-war army had allowed recruits to be assigned to the Corps of their wishes. This led to men being allocated to the wrong or unsuitable Corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was first named as such in 1805. The size of a corps varies great ...

. The Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

, Leslie Hore-Belisha

Leslie Hore-Belisha, 1st Baron Hore-Belisha, PC (; 7 September 1893 – 16 February 1957) was a British Liberal, then National Liberal Member of Parliament (MP) and Cabinet Minister. He later joined the Conservative Party. He proved highly su ...

attempted to address these problems, and the wider problems of the British Army.Crang (2000), p.5 The process of allocating men would remain ad hoc at the start of the war. The army would be without the quotas of men required from skilled professions and trades, which modern warfare demanded. With the British Army being the least popular service compared to the Royal Navy and RAF, a higher proportion of army recruits were said to be dull and backwards.

The following memorandum to the executive committee of the Army Council highlighted the growing concern.

"The British Army is wasting manpower in this war almost as badly as it did in the last war. A man is posted to a Corps almost entirely on the demand of the moment and without any effort at personal selection by proper tests."Only with the creation of the

Beveridge committee

The Beveridge Report, officially entitled ''Social Insurance and Allied Services'' (Command paper, Cmd. 6404), is a government report, published in November 1942, influential in the founding of the welfare state in the United Kingdom. It was draft ...

in 1941, and their subsequent findings in 1942, would the situation of skilled men not being assigned correctly be addressed. The findings led directly to the creation of the General Service Corps

The General Service Corps (GSC) is a corps of the British Army.

Role

The role of the corps is to provide specialists, who are usually on the Special List or General List. These lists were used in both World Wars for specialists and those not allo ...

that remains in place today.

Infantry division

During the war, the British Army raised 43 infantry divisions. Not all of these existed at the same time, and several were formed purely as training or administrative formations. Eight regular army divisions existed at the start of the war or were formed immediately afterwards from garrisons in the Middle East. The Territorial Army had 12 "first line" divisions (which had existed, generally, since the raising of the Territorial Force in the early 1900s), and raised a further 12 "second line" divisions from small cadres. Five other infantry divisions were created during the war, either converted from static "county" divisions or specially raised forOperation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

or the Burma Campaign.

The 1939 infantry division had a theoretical establishment of 13,863 men. By 1944, the strength had risen to 18,347 men.Brayley & Chappell (2001), p.17 This increase in manpower resulted mainly from the increased establishment of a division's subunits and formations; except for certain specialist supporting services, the overall structure remained substantially the same throughout the war. A 1944 division typically was made up of three infantry brigades; a Medium Machine Gun (MMG) battalion (with 36

The 1939 infantry division had a theoretical establishment of 13,863 men. By 1944, the strength had risen to 18,347 men.Brayley & Chappell (2001), p.17 This increase in manpower resulted mainly from the increased establishment of a division's subunits and formations; except for certain specialist supporting services, the overall structure remained substantially the same throughout the war. A 1944 division typically was made up of three infantry brigades; a Medium Machine Gun (MMG) battalion (with 36 Vickers machine gun

The Vickers machine gun or Vickers gun is a Water cooling, water-cooled .303 British (7.7 mm) machine gun produced by Vickers Limited, originally for the British Army. The gun was operated by a three-man crew but typically required more me ...

s, in three companies, and one company of 16 4.2-inch mortars); a reconnaissance regiment; a divisional artillery group, which consisted of three motorised field artillery regiments each with twenty-four 25-pounder guns, an anti-tank regiment with forty-eight anti-tank guns and a light anti-aircraft regiment with fifty-four Bofors 40 mm Bofors 40 mm gun is a name or designation given to two models of 40 mm calibre anti-aircraft guns designed and developed by the Swedish company Bofors:

*Bofors 40 mm L/60 gun - developed in the 1930s, widely used in World War II and into the 1990s

...

guns; three field companies and one field park company of the Royal Engineer

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is heade ...

s; three transport companies of the Royal Army Service Corps

The Royal Army Service Corps (RASC) was a corps of the British Army responsible for land, coastal and lake transport, air despatch, barracks administration, the Army Fire Service, staffing headquarters' units, supply of food, water, fuel and dom ...

; an ordnance field park company of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps

The Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) was a corps of the British Army. At its renaming as a Royal Corps in 1918 it was both a supply and repair corps. In the supply area it had responsibility for weapons, armoured vehicles and other military equip ...

; three field ambulances of the Royal Army Medical Corps

The Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) is a specialist corps in the British Army which provides medical services to all Army personnel and their families, in war and in peace. The RAMC, the Royal Army Veterinary Corps, the Royal Army Dental Corps a ...

, a signals unit of the Royal Corps of Signals

The Royal Corps of Signals (often simply known as the Royal Signals – abbreviated to R SIGNALS or R SIGS) is one of the combat support arms of the British Army. Signals units are among the first into action, providing the battlefield communi ...

; and a provost company of the Royal Military Police

The Royal Military Police (RMP) is the corps of the British Army responsible for the policing of army service personnel, and for providing a military police presence both in the UK and while service personnel are deployed overseas on operation ...

.Brayley & Chappell (2001), pp.17–18 During the war, the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers

The Corps of Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME ) is a corps of the British Army that maintains the equipment that the Army uses. The corps is described as the "British Army's Professional Engineers".

History

Prior to REME's for ...

was formed to take over the responsibility of recovering and repairing vehicles and other equipment. A division generally had three workshop companies, and a recovery company from the REME.

There were very few variations on this standard establishment. For example, the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division

The 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division was an infantry division of the British Army that was originally formed as the Lowland Division, in 1908 as part of the Territorial Force. It later became the 52nd (Lowland) Division in 1915. The 52nd (Lowland ...

was converted to a Mountain Division, with lighter equipment and transport. Other differences were generally the result of local exigencies. (A "Lower Establishment" existed for divisions stationed in Britain or inactive theatres, which were not intended to take part in active operations.)

With all cavalry and armoured regiments committed to armoured formations in the early part of the war, there were no units left for divisional reconnaissance, so the Reconnaissance Corps

The Reconnaissance Corps, or simply Recce Corps, was a corps of the British Army, formed during the Second World War whose units provided reconnaissance for infantry divisions. It was formed from infantry brigade reconnaissance groups on 14 Janu ...

was formed in January 1941. Ten infantry battalions were reformed as reconnaissance battalions.Perry (1988), p.57 The Reconnaissance Corps was merged into the Royal Armoured Corps

The Royal Armoured Corps is the component of the British Army, that together with the Household Cavalry provides its armour capability, with vehicles such as the Challenger 2 Tank and the Scimitar Reconnaissance Vehicle. It includes most of the A ...

in 1944.

The Infantry brigade typically had a HQ company and three infantry battalions. Fire support was provided by the allocation of an MMG company, anti tank battery, Royal Engineer company and/or field artillery regiment as required. Brigade Groups, which operated independently, had Royal Engineer, Royal Army Service Corps, Royal Army Medical Corps and Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers units permanently assigned. Brigade groups were also formed on an ''ad-hoc'' basis and were given whatever resources was needed to complete an objective. However, it was intended before the war that the division was the lowest formation at which support (particularly artillery fire) could be properly concentrated and coordinated. Lieutenant-General Montgomery reimposed and reinforced this principle when he assumed command of the Eighth Army in North Africa in 1942, halting a tendency to split divisions into uncoordinated brigades and "penny packets".

The infantry battalion consisted of the battalion Headquarters (HQ), HQ company (signals and administration platoons), four rifle companies (HQ and three rifle platoons), a support company with a carrier platoon, mortar platoon, anti tank platoon and pioneer platoon. The rifle platoon had a HQ, which included a 2-inch mortar

The Ordnance SBML two-inch mortar, or more commonly, just "two-inch mortar", was a British mortar issued to the British Army and the Commonwealth armies, that saw use during the Second World War and later.

It was more portable than larger mort ...

and an anti tank weapon team, and three rifle sections, each containing seven riflemen and a three-man Bren gun

The Bren gun was a series of light machine guns (LMG) made by Britain in the 1930s and used in various roles until 1992. While best known for its role as the British and Commonwealth forces' primary infantry LMG in World War II, it was also use ...

team.

Armoured division

At the start of the war, the British Army possessed only two armoured divisions: the Mobile Division, formed in Britain in October 1937, and the Mobile Division (Egypt), formed in the autumn of 1938 following the

At the start of the war, the British Army possessed only two armoured divisions: the Mobile Division, formed in Britain in October 1937, and the Mobile Division (Egypt), formed in the autumn of 1938 following the Munich Crisis

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

,Carter, p. 11Perry, p. 45Chappell (1987), pp. 12–15 These two divisions were later redesignated the 1st Armoured Division, in April 1939,French (2000), p. 42 and 7th Armoured Division, in January 1940, respectively.

During the war, the army raised a further nine armoured divisions, some of which were training formations and saw no action. Three were formed from first-line territorial or Yeomanry units. Six more were raised from various sources. As with the infantry divisions, not all existed at the same time, as several armoured divisions were disbanded or reduced to skeleton establishments during the course of the war, as a result of battle casualties or to provide reinforcements to bring other formations up to full strength.

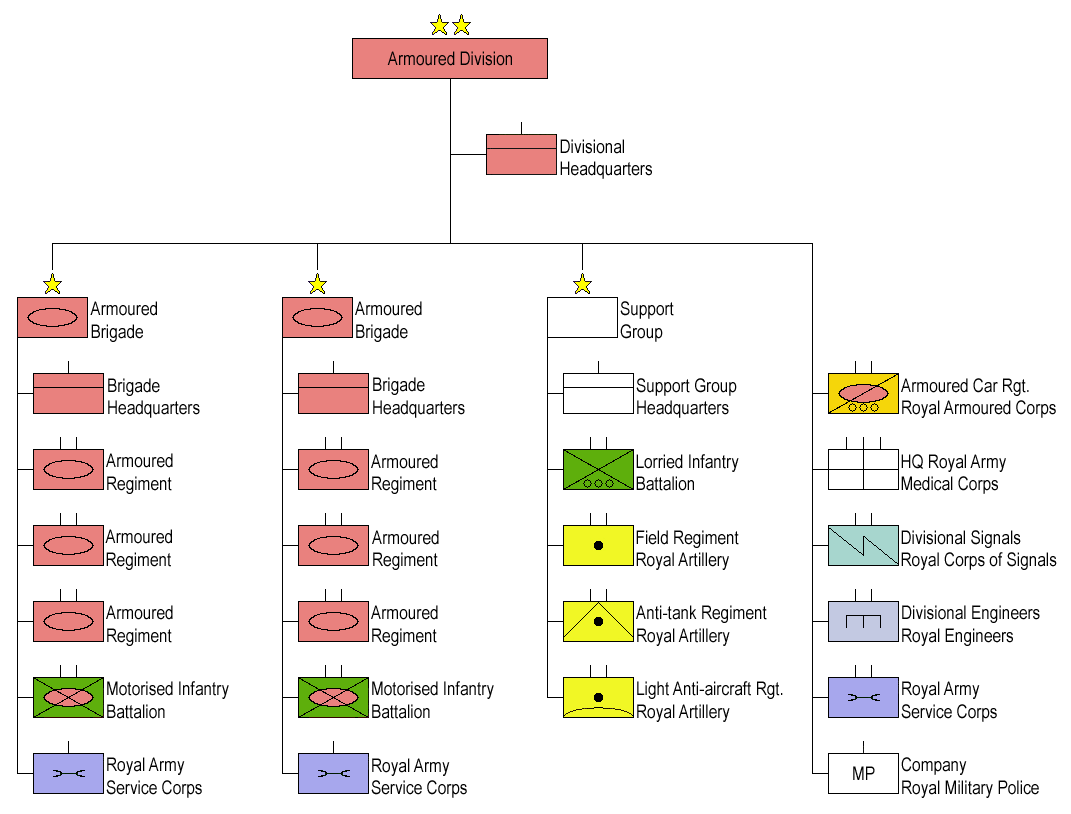

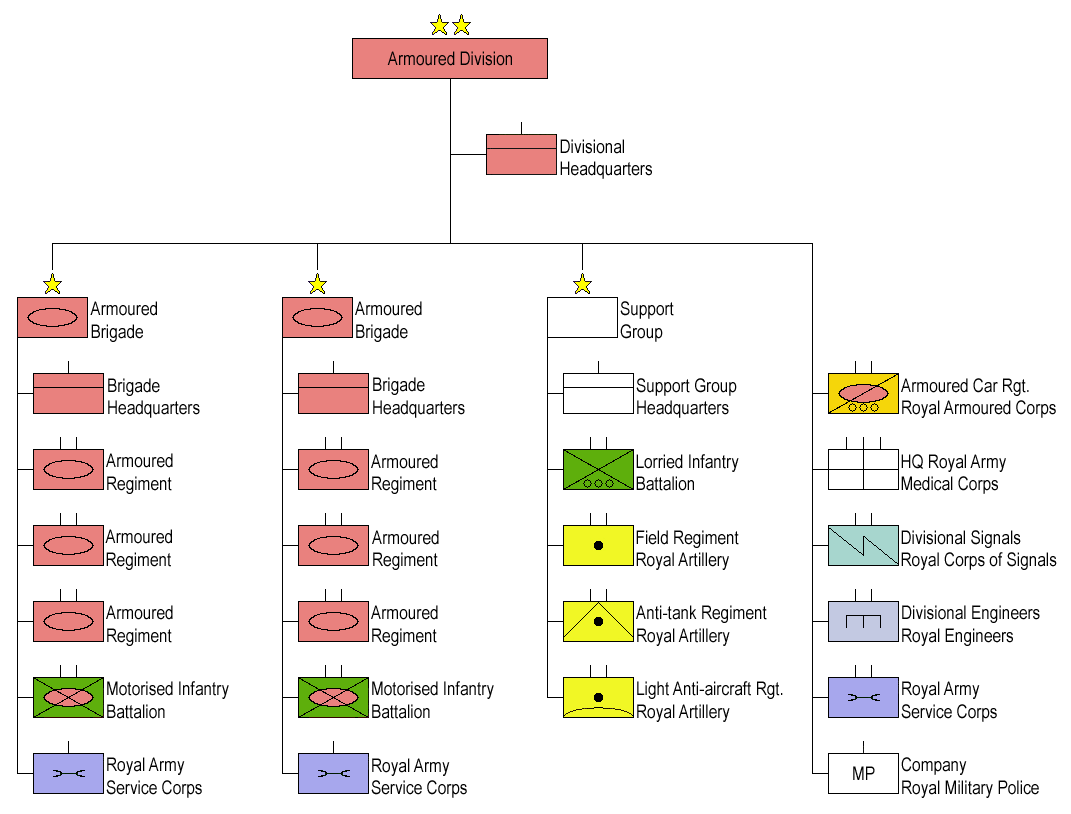

The structure of British armoured divisions changed several times before and during the war. In 1937, the Mobile Division had two cavalry brigades each with three light tank regiments, a tank brigade with three medium tank regiments, and a "Pivot Group" (later called the "Support Group") containing two motorised infantry battalions and two artillery regiments. The Mobile Division (Egypt) had a light armoured brigade, a cavalry brigade, a heavy armoured group of two regiments and a pivot group.

By 1939, the intention was for an Armoured Division to consist of two armoured brigades, a support group and divisional troops. The armoured brigades would each be composed of three armoured regiments with a mixture of light and medium tanks, with a total complement of 220 tanks, while the support group would be composed of two motorised infantry

Motorized infantry is infantry that is transported by trucks or other motor vehicles. It is distinguished from mechanized infantry, which is carried in armoured personnel carriers or infantry fighting vehicles, and from light infantry, which ...

battalions, two field artillery regiments, one anti–tank regiment and one light anti–aircraft regiment.

In late 1940, following the campaign in France and Belgium in the spring, it was realised that there were insufficient infantry and support units, and mixing light and cruiser tanks in the same brigade had been a mistake. The armoured divisions' organisation was changed so that each armoured brigade now incorporated a motorised infantry battalion, and a third battalion was present within the Support Group.

In the winter of 1940–41, new armoured regiments were formed by converting the remaining mounted

In late 1940, following the campaign in France and Belgium in the spring, it was realised that there were insufficient infantry and support units, and mixing light and cruiser tanks in the same brigade had been a mistake. The armoured divisions' organisation was changed so that each armoured brigade now incorporated a motorised infantry battalion, and a third battalion was present within the Support Group.

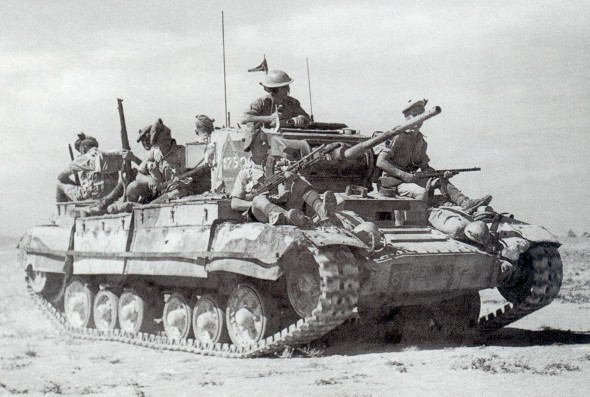

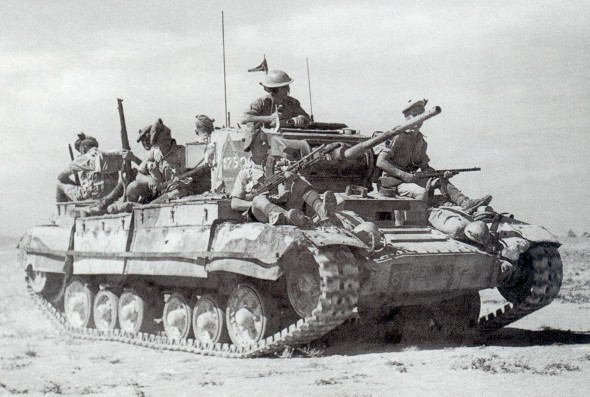

In the winter of 1940–41, new armoured regiments were formed by converting the remaining mounted cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

and yeomanry regiments. A year later, 33 infantry battalions were also converted to armoured regiments. By the Second Battle of El Alamein

The Second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 11 November 1942) was a battle of the Second World War that took place near the Egyptian Railway station, railway halt of El Alamein. The First Battle of El Alamein and the Battle of Alam el Halfa ...

, in late 1942, the British Army had realised that an entire infantry brigade was needed within each division, but until mid 1944, the idea that the armoured and motorised infantry brigades should fight separate albeit coordinated battles persisted. By the Battle of Normandy in 1944, the divisions consisted of an armoured brigade of three armoured regiments and a motorised infantry battalion, and an infantry brigade containing three motorised infantry battalions. The division's support troops included an armoured car regiment, an armoured reconnaissance regiment, two field artillery regiments (one of which was equipped with 24 Sexton self-propelled 25-pounder guns), one anti–tank regiment (with one or more batteries equipped with Archer

Archery is the sport, practice, or skill of using a bow to shoot arrows.Paterson ''Encyclopaedia of Archery'' p. 17 The word comes from the Latin ''arcus'', meaning bow. Historically, archery has been used for hunting and combat. In mo ...

or Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus ( grc-gre, Ἀχιλλεύς) was a hero of the Trojan War, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and the central character of Homer's ''Iliad''. He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Peleus, k ...

tank destroyers in place of towed anti–tank guns) and one light anti–aircraft regiment, with the usual assortment of engineers, mechanics, signals, transport, medical, and other support services.Brayley & Chappell (2001), p.19

The armoured reconnaissance regiment was equipped with medium tanks, bringing the armoured divisions to a strength of 246 medium tanksReynolds, p.31 (roughly 340 tanks in total) and by the end of the Battle of Normandy the divisions started to operate as two brigade groups, each of two combined arms

Combined arms is an approach to warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme vio ...

teams, each in turn of one tank regiment and one infantry battalion (The armoured reconnaissance regiment was matched with the armoured brigade's motor battalion to provide the fourth group).

In 1944, the division's armoured regiments comprised 78 tanks. The regimental headquarters was equipped with four medium tanks, an anti–aircraft troop with eight Crusader Anti–Aircraft tanks, and the regiment's reconnaissance troop with eleven Stuart tanks.Taylor, p.6 Each regiment also had three Sabre squadrons; generally comprising four

In 1944, the division's armoured regiments comprised 78 tanks. The regimental headquarters was equipped with four medium tanks, an anti–aircraft troop with eight Crusader Anti–Aircraft tanks, and the regiment's reconnaissance troop with eleven Stuart tanks.Taylor, p.6 Each regiment also had three Sabre squadrons; generally comprising four troop

A troop is a military sub-subunit, originally a small formation of cavalry, subordinate to a squadron. In many armies a troop is the equivalent element to the infantry section or platoon. Exceptions are the US Cavalry and the King's Troop Ro ...

s each of four tanks, and a squadron headquarters of three tanks. The Sabre Squadrons contained three close support tanks, 12 medium tanks, and four Sherman Firefly

The Sherman Firefly was a tank used by the United Kingdom and some armoured formations of other Allies in the Second World War. It was based on the US M4 Sherman, but was fitted with the more powerful 3-inch (76.2 mm) calibre British 17- ...

s. Additionally, 18 tanks were allocated to the armoured brigade's headquarters and a further ten to the division's headquarters.

Artillery

The Royal Artillery was a large corps, responsible for the provision of field, medium, heavy, mountain, anti-tank and anti-aircraft units. (Some field regiments, particularly self-propelled regiments in the later part of the war, belonged to the prestigious

The Royal Artillery was a large corps, responsible for the provision of field, medium, heavy, mountain, anti-tank and anti-aircraft units. (Some field regiments, particularly self-propelled regiments in the later part of the war, belonged to the prestigious Royal Horse Artillery

The Royal Horse Artillery (RHA) was formed in 1793 as a distinct arm of the Royal Regiment of Artillery (commonly termed Royal Artillery) to provide horse artillery support to the cavalry units of the British Army. (Although the cavalry link ...

, but were organised similarly to those of the RA.)

The main field artillery weapon throughout the war was the 25-pounder, with a range of for the Mk II model, Employed in a direct fire

Direct fire or line-of-sight fire refers to firing of a ranged weapon whose projectile is launched directly at a target within the line-of-sight of the user. The firing weapon must have a sighting device and an unobstructed view to the target, w ...

role it was also the most effective anti–tank weapon until the 6-Pounder anti–tank gun became available. One shortcoming of using the 25-pounder in this role was it effectiveness above was limited and it deprived the army of indirect fire

Indirect fire is aiming and firing a projectile without relying on a direct line of sight between the gun and its target, as in the case of direct fire. Aiming is performed by calculating azimuth and inclination, and may include correcting aim by ...

support. Only 78 25-pounders had been delivered when the war began, so old 18-pounders, many of which had been converted to using 25-pounder ammunition as 18/25-pounders, were also employed.

Each field artillery regiment was originally organised as two batteries, each of two troops of six guns. This was changed late in 1940 to three batteries each of eight guns. Perhaps the most important element of a battery was the Forward Observation Officer

An artillery observer, artillery spotter or forward observer (FO) is responsible for directing artillery and mortar (weapon), mortar shooting, fire onto a target. It may be a ''forward air controller'' (FAC) for close air support (CAS) and spo ...

(FOO), who directed fire. Unlike most armies of the period, in which artillery observers could only request fire support, a British Army FOO (who was supposedly a captain but could even be a subaltern) could demand it, not merely from his own battery, but from the full regiment, or even the entire field artillery of a division if required. The artillery's organisation became very flexible and effective at rapidly providing and switching fire.

The medium artillery relied on the First World War vintage guns until the arrival, in 1941, of the 4.5-inch Medium gun, which had a range of for a shell. This was followed in 1942 by the 5.5-inch Medium gun, which had a range of for an shell.Moreman (2007), p.52 The heavy artillery was equipped with the 7.2-inch Howitzer, a modified First World War weapon that nevertheless remained effective. During the war, brigade–sized formations of artillery, referred to as Army Group Royal Artillery

An Army Group Royal Artillery (AGRA) was a British Commonwealth military formation during the Second World War and shortly thereafter. Generally assigned to Army corps, an AGRA provided the medium and heavy artillery to higher formations within the ...

(AGRA), were formed. These allowed control of medium and heavy artillery to be centralised. Each AGRA was normally allocated to provide support to a corps, but could be assigned as needed by an Army HQ.

Although infantry units each had an anti-tank platoon, divisions also had a Royal Artillery anti-tank regiment. This had four batteries, each of twelve guns. At the start of the war, they were equipped with the 2-pounder. Although this was perhaps the most effective weapon of its type at the time, it soon became obsolete as tanks became heavier with thicker armour. Its replacement, the 6-pounder, nevertheless did not enter service until early 1942. Even before the 6-pounder was introduced, it was felt that even heavier weapons would be needed, so the 17-pounder was designed, first seeing service in the North African Campaign in late 1942.

Each division also had a light anti-aircraft regiment. Initially, batteries were organised in troops of four guns, but combat experience showed that a three-gun troop was as effective, shooting in a triangular formation, so the batteries were reorganised as four troops of three guns. The troops were subsequently increased in size to six guns, so the regiment then had three batteries each with eighteen Bofors 40 mm guns. This equipment and organisation remained unchanged throughout the war.

The Royal Artillery also formed twelve Anti–aircraft divisions, equipped with heavier weapons. These were mainly the 3-inch and 3.7-inch anti–aircraft guns, but also the 4.5-inch and 5.25-inch guns where convenient. These divisions were organised into Anti-Aircraft Command