tokamak on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

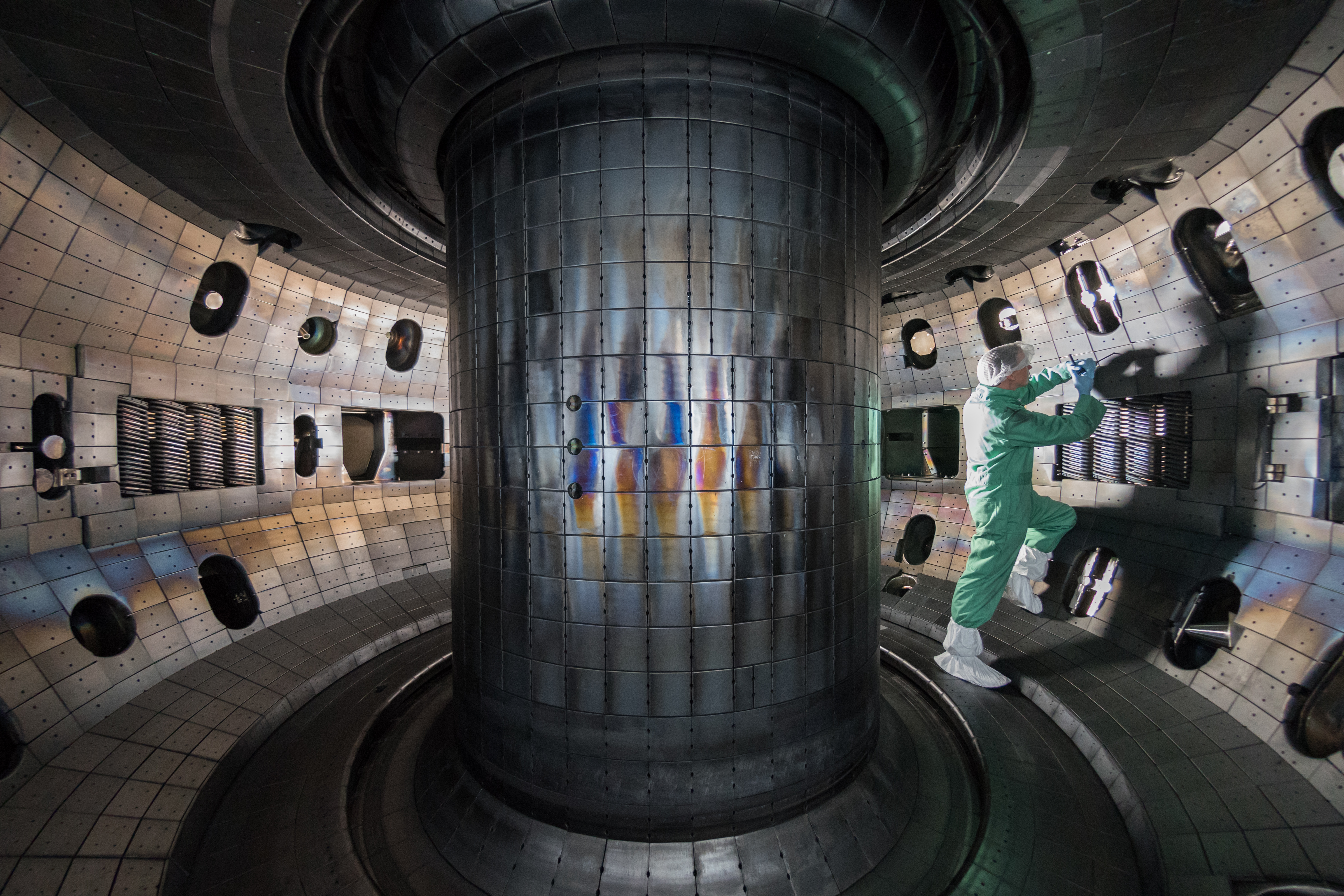

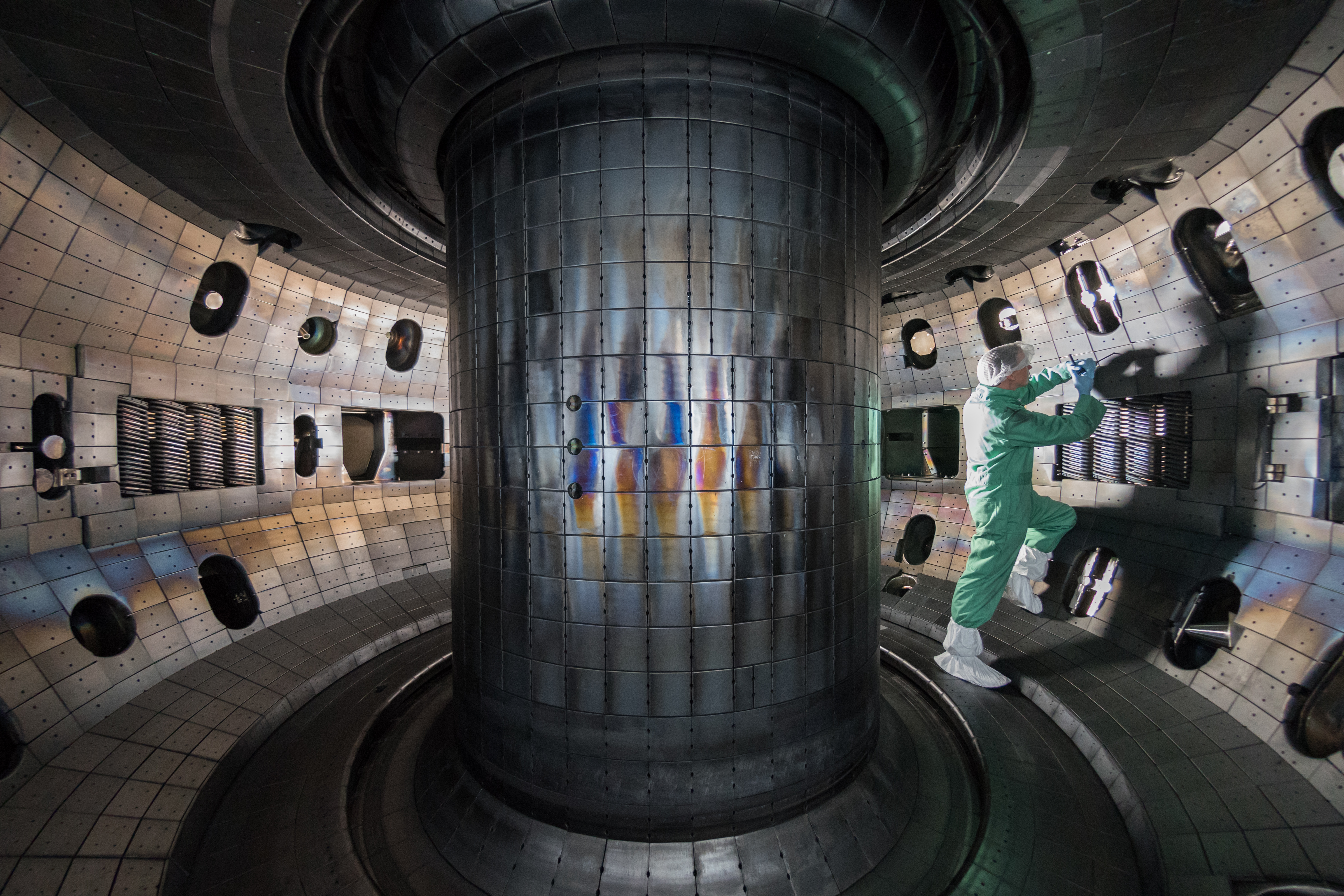

A tokamak (; russian: токамáк; otk, 𐱃𐰸𐰢𐰴, Toḳamaḳ) is a device which uses a powerful

A tokamak (; russian: токамáк; otk, 𐱃𐰸𐰢𐰴, Toḳamaḳ) is a device which uses a powerful

toḳımaḳ

ref name=toḳımaḳ> Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk 1073br>Turkish Etimology

/ref> (the beater used by the beaters) In addition, since it is used for forging iron in blacksmithing, it is technically reasonable to conside

this Turkish word

as appropriate. It is known that the oldest usage of the word Tokamak/Tokmak is in Göktürk Khanate

On 25 March 1951, Argentine President

On 25 March 1951, Argentine President

By October, Sakharov and Tamm had completed a much more detailed consideration of their original proposal, calling for a device with a major radius (of the torus as a whole) of and a minor radius (the interior of the cylinder) of . The proposal suggested the system could produce of

By October, Sakharov and Tamm had completed a much more detailed consideration of their original proposal, calling for a device with a major radius (of the torus as a whole) of and a minor radius (the interior of the cylinder) of . The proposal suggested the system could produce of

In 1955, with the linear approaches still subject to instability, the first toroidal device was built in the USSR. TMP was a classic pinch machine, similar to models in the UK and US of the same era. The vacuum chamber was made of ceramic, and the spectra of the discharges showed silica, meaning the plasma was not perfectly confined by magnetic field and hitting the walls of the chamber. Two smaller machines followed, using copper shells. The conductive shells were intended to help stabilize the plasma, but were not completely successful in any of the machines that tried it.

With progress apparently stalled, in 1955, Kurchatov called an All Union conference of Soviet researchers with the ultimate aim of opening up fusion research within the USSR. In April 1956, Kurchatov travelled to the UK as part of a widely publicized visit by

In 1955, with the linear approaches still subject to instability, the first toroidal device was built in the USSR. TMP was a classic pinch machine, similar to models in the UK and US of the same era. The vacuum chamber was made of ceramic, and the spectra of the discharges showed silica, meaning the plasma was not perfectly confined by magnetic field and hitting the walls of the chamber. Two smaller machines followed, using copper shells. The conductive shells were intended to help stabilize the plasma, but were not completely successful in any of the machines that tried it.

With progress apparently stalled, in 1955, Kurchatov called an All Union conference of Soviet researchers with the ultimate aim of opening up fusion research within the USSR. In April 1956, Kurchatov travelled to the UK as part of a widely publicized visit by

A tokamak (; russian: токамáк; otk, 𐱃𐰸𐰢𐰴, Toḳamaḳ) is a device which uses a powerful

A tokamak (; russian: токамáк; otk, 𐱃𐰸𐰢𐰴, Toḳamaḳ) is a device which uses a powerful magnetic field

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to ...

to confine plasma in the shape of a torus

In geometry, a torus (plural tori, colloquially donut or doughnut) is a surface of revolution generated by revolving a circle in three-dimensional space about an axis that is coplanar with the circle.

If the axis of revolution does not tou ...

. The tokamak is one of several types of magnetic confinement

Magnetic confinement fusion is an approach to generate thermonuclear fusion power that uses magnetic fields to confine fusion fuel in the form of a plasma. Magnetic confinement is one of two major branches of fusion energy research, along with ...

devices being developed to produce controlled thermonuclear

Thermonuclear fusion is the process of atomic nuclei combining or “fusing” using high temperatures to drive them close enough together for this to become possible. There are two forms of thermonuclear fusion: ''uncontrolled'', in which the re ...

fusion power

Fusion power is a proposed form of power generation that would generate electricity by using heat from nuclear fusion reactions. In a fusion process, two lighter atomic nuclei combine to form a heavier nucleus, while releasing energy. Devices de ...

. , it was the leading candidate for a practical fusion reactor

Fusion power is a proposed form of power generation that would generate electricity by using heat from nuclear fusion reactions. In a fusion process, two lighter atomic nuclei combine to form a heavier nucleus, while releasing energy. Devices ...

.

Tokamaks were initially conceptualized in the 1950s by Soviet physicists Igor Tamm

Igor Yevgenyevich Tamm ( rus, И́горь Евге́ньевич Тамм , p=ˈiɡərʲ jɪvˈɡʲenʲjɪvitɕ ˈtam , a=Ru-Igor Yevgenyevich Tamm.ogg; 8 July 1895 – 12 April 1971) was a Soviet physicist who received the 1958 Nobel Prize in ...

and Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for n ...

, inspired by a letter by Oleg Lavrentiev. The first working tokamak was attributed to the work of Natan Yavlinsky

Natan Aronovich Yavlinsky (russian: Натан Аронович Явлинский; 13 February 191228 July 1962) was a Russian physicist in the former Soviet Union who invented and developed the first working tokamak.

Early life and career

Yav ...

on the T-1 in 1958. It had been demonstrated that a stable plasma equilibrium requires magnetic field line

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to ...

s that wind around the torus in a helix

A helix () is a shape like a corkscrew or spiral staircase. It is a type of smooth space curve with tangent lines at a constant angle to a fixed axis. Helices are important in biology, as the DNA molecule is formed as two intertwined helices, ...

. Devices like the z-pinch

In fusion power research, the Z-pinch (zeta pinch) is a type of plasma confinement system that uses an electric current in the plasma to generate a magnetic field that compresses it (see pinch). These systems were originally referred to simp ...

and stellarator

A stellarator is a plasma device that relies primarily on external magnets to confine a plasma. Scientists researching magnetic confinement fusion aim to use stellarator devices as a vessel for nuclear fusion reactions. The name refers to the ...

had attempted this, but demonstrated serious instabilities. It was the development of the concept now known as the safety factor

In engineering, a factor of safety (FoS), also known as (and used interchangeably with) safety factor (SF), expresses how much stronger a system is than it needs to be for an intended load. Safety factors are often calculated using detailed analy ...

(labelled ''q'' in mathematical notation) that guided tokamak development; by arranging the reactor so this critical factor ''q'' was always greater than 1, the tokamaks strongly suppressed the instabilities which plagued earlier designs.

By the mid-1960s, the tokamak designs began to show greatly improved performance. The initial results were released in 1965, but were ignored; Lyman Spitzer

Lyman Spitzer Jr. (June 26, 1914 – March 31, 1997) was an American theoretical physicist, astronomer and mountaineer. As a scientist, he carried out research into star formation, plasma physics, and in 1946, conceived the idea of telesco ...

dismissed them out of hand after noting potential problems in their system for measuring temperatures. A second set of results was published in 1968, this time claiming performance far in advance of any other machine. When these were also met skeptically, the Soviets invited a delegation from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

to make their own measurements. These confirmed the Soviet results, and their 1969 publication resulted in a stampede of tokamak construction.

By the mid-1970s, dozens of tokamaks were in use around the world. By the late 1970s, these machines had reached all of the conditions needed for practical fusion, although not at the same time nor in a single reactor. With the goal of breakeven (a fusion energy gain factor

A fusion energy gain factor, usually expressed with the symbol ''Q'', is the ratio of fusion power produced in a nuclear fusion reactor to the power required to maintain the plasma in steady state. The condition of ''Q'' = 1, when the power bei ...

equal to 1) now in sight, a new series of machines were designed that would run on a fusion fuel of deuterium

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two Stable isotope ratio, stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being Hydrogen atom, protium, or hydrogen-1). The atomic nucleus, nucleus of a deuterium ato ...

and tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus o ...

. These machines, notably the Joint European Torus

The Joint European Torus, or JET, is an operational Magnetic confinement fusion, magnetically confined Plasma (physics), plasma physics experiment, located at Culham Centre for Fusion Energy in Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, UK. Based on a tokamak ...

(JET), Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor

The Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor (TFTR) was an experimental tokamak built at Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) circa 1980 and entering service in 1982. TFTR was designed with the explicit goal of reaching scientific breakeven, the point w ...

(TFTR), had the explicit goal of reaching breakeven.

Instead, these machines demonstrated new problems that limited their performance. Solving these would require a much larger and more expensive machine, beyond the abilities of any one country. After an initial agreement between Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

and Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

in November 1985, the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor

ITER (initially the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, ''iter'' meaning "the way" or "the path" in Latin) is an international nuclear fusion research and engineering megaproject aimed at creating energy by replicating, on Earth ...

(ITER) effort emerged and remains the primary international effort to develop practical fusion power. Many smaller designs, and offshoots like the spherical tokamak

A spherical tokamak is a type of fusion power device based on the tokamak principle. It is notable for its very narrow profile, or '' aspect ratio''. A traditional tokamak has a toroidal confinement area that gives it an overall shape similar to ...

, continue to be used to investigate performance parameters and other issues. , JET remains the record holder for fusion output, reaching 16 MW of output for 24 MW of input heating power.

Etymology

The word ''tokamak'' is atransliteration

Transliteration is a type of conversion of a text from one writing system, script to another that involves swapping Letter (alphabet), letters (thus ''wikt:trans-#Prefix, trans-'' + ''wikt:littera#Latin, liter-'') in predictable ways, such as ...

of the Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

word , an acronym of either:

:

:

: toroidal chamber with magnetic coils;

or

:

:

: toroidal chamber with axial magnetic field.

The term was created in 1957 by Igor Golovin, the vice-director of the Laboratory of Measuring Apparatus of Academy of Science, today's Kurchatov Institute

The Kurchatov Institute (russian: Национальный исследовательский центр «Курчатовский Институт», 'National Research Centre "Kurchatov Institute) is Russia's leading research and developmen ...

. A similar term, ''tokomag'', was also proposed for a time.

Also considering the existence of many Turkic nations living in the Russian region, it can be thought that the etymological analogy is the origin of the word Turkish tokmak. Old Turkishtoḳımaḳ

ref name=toḳımaḳ> Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk 1073br>Turkish Etimology

/ref> (the beater used by the beaters) In addition, since it is used for forging iron in blacksmithing, it is technically reasonable to conside

this Turkish word

as appropriate. It is known that the oldest usage of the word Tokamak/Tokmak is in Göktürk Khanate

History

First steps

In 1934,Mark Oliphant

Sir Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant, (8 October 1901 – 14 July 2000) was an Australian physicist and humanitarian who played an important role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and in the development of nuclear weapon ...

, Paul Harteck

Paul Karl Maria Harteck (20 July 190222 January 1985) was an Austrian physical chemist. In 1945 under Operation Epsilon in "the big sweep" throughout Germany, Harteck was arrested by the allied British and American Armed Forces for suspicion of ...

and Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.

''Encyclopædia Britannica'' considers him to be the greatest ...

were the first to achieve fusion on Earth, using a particle accelerator

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel charged particles to very high speeds and energies, and to contain them in well-defined beams.

Large accelerators are used for fundamental research in particle ...

to shoot deuterium

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two Stable isotope ratio, stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being Hydrogen atom, protium, or hydrogen-1). The atomic nucleus, nucleus of a deuterium ato ...

nuclei into metal foil containing deuterium or other atoms. This allowed them to measure the nuclear cross section

The nuclear cross section of a nucleus is used to describe the probability that a nuclear reaction will occur. The concept of a nuclear cross section can be quantified physically in terms of "characteristic area" where a larger area means a large ...

of various fusion reactions, and determined that the deuterium–deuterium reaction occurred at a lower energy than other reactions, peaking at about 100,000 electronvolt

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV, also written electron-volt and electron volt) is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy

In physics, the kinetic energy of an object is the energy that it possesses due to its motion.

It is defi ...

s (100 keV).

Accelerator-based fusion is not practical because the reactor cross section

Cross section may refer to:

* Cross section (geometry)

** Cross-sectional views in architecture & engineering 3D

*Cross section (geology)

* Cross section (electronics)

* Radar cross section, measure of detectability

* Cross section (physics)

**Abs ...

is tiny; most of the particles in the accelerator will scatter off the fuel, not fuse with it. These scatterings cause the particles to lose energy to the point where they can no longer undergo fusion. The energy put into these particles is thus lost, and it is easy to demonstrate this is much more energy than the resulting fusion reactions can release.

To maintain fusion and produce net energy output, the bulk of the fuel must be raised to high temperatures so its atoms are constantly colliding at high speed; this gives rise to the name ''thermonuclear'' due to the high temperatures needed to bring it about. In 1944, Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

calculated the reaction would be self-sustaining at about 50,000,000 K; at that temperature, the rate that energy is given off by the reactions is high enough that they heat the surrounding fuel rapidly enough to maintain the temperature against losses to the environment, continuing the reaction.

During the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, the first practical way to reach these temperatures was created, using an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

. In 1944, Fermi gave a talk on the physics of fusion in the context of a then-hypothetical hydrogen bomb. However, some thought had already been given to a ''controlled'' fusion device, and James L. Tuck

James Leslie Tuck Order of the British Empire, OBE, (9 January 1910 – 15 December 1980) was a British physicist. He was born in Manchester, England, and educated at the Victoria University of Manchester. Because of his involvement with the Manh ...

and Stanislaw Ulam had attempted such using shaped charge

A shaped charge is an explosive charge shaped to form an explosively formed penetrator (EFP) to focus the effect of the explosive's energy. Different types of shaped charges are used for various purposes such as cutting and forming metal, ini ...

s driving a metal foil infused with deuterium, although without success.

The first attempts to build a practical fusion machine took place in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, where George Paget Thomson

Sir George Paget Thomson, FRS (; 3 May 189210 September 1975) was a British physicist and Nobel laureate in physics recognized for his discovery of the wave properties of the electron by electron diffraction.

Education and early life

Thomso ...

had selected the pinch effect

A pinch (or: Bennett pinch (after Willard Harrison Bennett), electromagnetic pinch, magnetic pinch, pinch effect, or plasma pinch.) is the compression of an electrically conducting Electrical filament, filament by magnetic forces, or a device tha ...

as a promising technique in 1945. After several failed attempts to gain funding, he gave up and asked two graduate students, Stanley (Stan) W. Cousins and Alan Alfred Ware (1924–2010), to build a device out of surplus radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

equipment. This was successfully operated in 1948, but showed no clear evidence of fusion and failed to gain the interest of the Atomic Energy Research Establishment

The Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE) was the main Headquarters, centre for nuclear power, atomic energy research and development in the United Kingdom from 1946 to the 1990s. It was created, owned and funded by the British Governm ...

.

Lavrentiev's letter

In 1950, Oleg Lavrentiev, then aRed Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

sergeant stationed on Sakhalin

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, r=Sakhalín, p=səxɐˈlʲin; ja, 樺太 ''Karafuto''; zh, c=, p=Kùyèdǎo, s=库页岛, t=庫頁島; Manchu: ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ, ''Sahaliyan''; Orok: Бугата на̄, ''Bugata nā''; Nivkh: ...

, wrote a letter to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, – TsK KPSS was the executive leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, acting between sessions of Congress. According to party statutes, the committee direct ...

. The letter outlined the idea of using an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

to ignite a fusion fuel, and then went on to describe a system that used electrostatic

Electrostatics is a branch of physics that studies electric charges at rest (static electricity).

Since classical times, it has been known that some materials, such as amber, attract lightweight particles after rubbing. The Greek word for amber ...

fields to contain a hot plasma in a steady state for energy production.

The letter was sent to Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for n ...

for comment. Sakharov noted that "the author formulates a very important and not necessarily hopeless problem", and found his main concern in the arrangement was that the plasma would hit the electrode wires, and that "wide meshes and a thin current-carrying part which will have to reflect almost all incident nuclei back into the reactor. In all likelihood, this requirement is incompatible with the mechanical strength of the device."

Some indication of the importance given to Lavrentiev's letter can be seen in the speed with which it was processed; the letter was received by the Central Committee on 29 July, Sakharov sent his review in on 18 August, by October, Sakharov and Igor Tamm

Igor Yevgenyevich Tamm ( rus, И́горь Евге́ньевич Тамм , p=ˈiɡərʲ jɪvˈɡʲenʲjɪvitɕ ˈtam , a=Ru-Igor Yevgenyevich Tamm.ogg; 8 July 1895 – 12 April 1971) was a Soviet physicist who received the 1958 Nobel Prize in ...

had completed the first detailed study of a fusion reactor, and they had asked for funding to build it in January 1951.

Magnetic confinement

When heated to fusion temperatures, theelectron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no kn ...

s in atoms dissociate, resulting in a fluid of nuclei and electrons known as plasma. Unlike electrically neutral atoms, a plasma is electrically conductive, and can, therefore, be manipulated by electrical or magnetic fields.

Sakharov's concern about the electrodes led him to consider using magnetic confinement instead of electrostatic. In the case of a magnetic field, the particles will circle around the lines of force

A line of force in Faraday's extended sense is synonymous with Maxwell's line of induction. According to J.J. Thomson, Faraday usually discusses ''lines of force'' as chains of polarized particles in a dielectric, yet sometimes Faraday discusses ...

. As the particles are moving at high speed, their resulting paths look like a helix. If one arranges a magnetic field so lines of force are parallel and close together, the particles orbiting adjacent lines may collide, and fuse.

Such a field can be created in a solenoid

upright=1.20, An illustration of a solenoid

upright=1.20, Magnetic field created by a seven-loop solenoid (cross-sectional view) described using field lines

A solenoid () is a type of electromagnet formed by a helix, helical coil of wire whose ...

, a cylinder with magnets wrapped around the outside. The combined fields of the magnets create a set of parallel magnetic lines running down the length of the cylinder. This arrangement prevents the particles from moving sideways to the wall of the cylinder, but it does not prevent them from running out the end. The obvious solution to this problem is to bend the cylinder around into a donut shape, or torus, so that the lines form a series of continual rings. In this arrangement, the particles circle endlessly.

Sakharov discussed the concept with Igor Tamm

Igor Yevgenyevich Tamm ( rus, И́горь Евге́ньевич Тамм , p=ˈiɡərʲ jɪvˈɡʲenʲjɪvitɕ ˈtam , a=Ru-Igor Yevgenyevich Tamm.ogg; 8 July 1895 – 12 April 1971) was a Soviet physicist who received the 1958 Nobel Prize in ...

, and by the end of October 1950 the two had written a proposal and sent it to Igor Kurchatov

Igor Vasil'evich Kurchatov (russian: Игорь Васильевич Курчатов; 12 January 1903 – 7 February 1960), was a Soviet physicist who played a central role in organizing and directing the former Soviet program of nuclear weapo ...

, the director of the atomic bomb project within the USSR, and his deputy, Igor Golovin. However, this initial proposal ignored a fundamental problem; when arranged along a straight solenoid, the external magnets are evenly spaced, but when bent around into a torus, they are closer together on the inside of the ring than the outside. This leads to uneven forces that cause the particles to drift away from their magnetic lines.

During visits to the Laboratory of Measuring Instruments of the USSR Academy of Sciences (LIPAN), the Soviet nuclear research centre, Sakharov suggested two possible solutions to this problem. One was to suspend a current-carrying ring in the centre of the torus. The current in the ring would produce a magnetic field that would mix with the one from the magnets on the outside. The resulting field would be twisted into a helix, so that any given particle would find itself repeatedly on the outside, then inside, of the torus. The drifts caused by the uneven fields are in opposite directions on the inside and outside, so over the course of multiple orbits around the long axis of the torus, the opposite drifts would cancel out. Alternately, he suggested using an external magnet to induce a current in the plasma itself, instead of a separate metal ring, which would have the same effect.

In January 1951, Kurchatov arranged a meeting at LIPAN to consider Sakharov's concepts. They found widespread interest and support, and in February a report on the topic was forwarded to Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolsheviks ...

, who oversaw the atomic efforts in the USSR. For a time, nothing was heard back.

Richter and the birth of fusion research

On 25 March 1951, Argentine President

On 25 March 1951, Argentine President Juan Perón

Juan Domingo Perón (, , ; 8 October 1895 – 1 July 1974) was an Argentine Army general and politician. After serving in several government positions, including Minister of Labour and Vice President of a military dictatorship, he was elected P ...

announced that a former German scientist, Ronald Richter

Ronald Richter (1909–1991) was an Austrian-born German, later Argentine citizen, scientist who became infamous in connection with the Argentine Huemul Project and the National Atomic Energy Commission (CNEA). The project was intended to generat ...

, had succeeded in producing fusion at a laboratory scale as part of what is now known as the Huemul Project

The Huemul Project ( es, Proyecto Huemul) was an early 1950s Argentine effort to develop a fusion power device known as the Thermotron. The concept was invented by Austrian scientist Ronald Richter, who claimed to have a design that would produc ...

. Scientists around the world were excited by the announcement, but soon concluded it was not true; simple calculations showed that his experimental setup could not produce enough energy to heat the fusion fuel to the needed temperatures.

Although dismissed by nuclear researchers, the widespread news coverage meant politicians were suddenly aware of, and receptive to, fusion research. In the UK, Thomson was suddenly granted considerable funding. Over the next months, two projects based on the pinch system were up and running. In the US, Lyman Spitzer

Lyman Spitzer Jr. (June 26, 1914 – March 31, 1997) was an American theoretical physicist, astronomer and mountaineer. As a scientist, he carried out research into star formation, plasma physics, and in 1946, conceived the idea of telesco ...

read the Huemul story, realized it was false, and set about designing a machine that would work. In May he was awarded $50,000 to begin research on his stellarator

A stellarator is a plasma device that relies primarily on external magnets to confine a plasma. Scientists researching magnetic confinement fusion aim to use stellarator devices as a vessel for nuclear fusion reactions. The name refers to the ...

concept. Jim Tuck had returned to the UK briefly and saw Thomson's pinch machines. When he returned to Los Alamos he also received $50,000 directly from the Los Alamos budget.

Similar events occurred in the USSR. In mid-April, Dmitri Efremov of the Scientific Research Institute of Electrophysical Apparatus stormed into Kurchatov's study with a magazine containing a story about Richter's work, demanding to know why they were beaten by the Argentines. Kurchatov immediately contacted Beria with a proposal to set up a separate fusion research laboratory with Lev Artsimovich

Lev Andreyevich Artsimovich ( Russian: Лев Андреевич Арцимович, February 25, 1909 – March 1, 1973), also transliterated Arzimowitsch, was a Soviet physicist who is regarded as the one of the founder of Tokamak— a device ...

as director. Only days later, on 5 May, the proposal had been signed by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

.

New ideas

By October, Sakharov and Tamm had completed a much more detailed consideration of their original proposal, calling for a device with a major radius (of the torus as a whole) of and a minor radius (the interior of the cylinder) of . The proposal suggested the system could produce of

By October, Sakharov and Tamm had completed a much more detailed consideration of their original proposal, calling for a device with a major radius (of the torus as a whole) of and a minor radius (the interior of the cylinder) of . The proposal suggested the system could produce of tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus o ...

a day, or breed of U233 a day.

As the idea was further developed, it was realized that a current in the plasma could create a field that was strong enough to confine the plasma as well, removing the need for the external magnets. At this point, the Soviet researchers had re-invented the pinch system being developed in the UK, although they had come to this design from a very different starting point.

Once the idea of using the pinch effect for confinement had been proposed, a much simpler solution became evident. Instead of a large toroid, one could simply induce the current into a linear tube, which could cause the plasma within to collapse down into a filament. This had a huge advantage; the current in the plasma would heat it through normal resistive heating

Joule heating, also known as resistive, resistance, or Ohmic heating, is the process by which the passage of an electric current through a conductor produces heat.

Joule's first law (also just Joule's law), also known in countries of former U ...

, but this would not heat the plasma to fusion temperatures. However, as the plasma collapsed, the adiabatic process

In thermodynamics, an adiabatic process (Greek: ''adiábatos'', "impassable") is a type of thermodynamic process that occurs without transferring heat or mass between the thermodynamic system and its environment. Unlike an isothermal process, ...

would result in the temperature rising dramatically, more than enough for fusion. With this development, only Golovin and Natan Yavlinsky

Natan Aronovich Yavlinsky (russian: Натан Аронович Явлинский; 13 February 191228 July 1962) was a Russian physicist in the former Soviet Union who invented and developed the first working tokamak.

Early life and career

Yav ...

continued considering the more static toroidal arrangement.

Instability

On 4 July 1952, Nikolai Filippov's group measuredneutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons beh ...

s being released from a linear pinch machine. Lev Artsimovich

Lev Andreyevich Artsimovich ( Russian: Лев Андреевич Арцимович, February 25, 1909 – March 1, 1973), also transliterated Arzimowitsch, was a Soviet physicist who is regarded as the one of the founder of Tokamak— a device ...

demanded that they check everything before concluding fusion had occurred, and during these checks, they found that the neutrons were not from fusion at all. This same linear arrangement had also occurred to researchers in the UK and US, and their machines showed the same behaviour. But the great secrecy surrounding the type of research meant that none of the groups were aware that others were also working on it, let alone having the identical problem.

After much study, it was found that some of the released neutrons were produced by instabilities in the plasma. There were two common types of instability, the ''sausage'' that was seen primarily in linear machines, and the ''kink'' which was most common in the toroidal machines. Groups in all three countries began studying the formation of these instabilities and potential ways to address them. Important contributions to the field were made by Martin David Kruskal

Martin David Kruskal (; September 28, 1925 – December 26, 2006) was an American mathematician and physicist. He made fundamental contributions in many areas of mathematics and science, ranging from plasma physics to general relativity and ...

and Martin Schwarzschild

Martin Schwarzschild (May 31, 1912 – April 10, 1997) was a German-American astrophysicist.

Biography

Schwarzschild was born in Potsdam into a distinguished German Jewish academic family. His father was the physicist Karl Schwarzschild and ...

in the US, and Shafranov in the USSR.

One idea that came from these studies became known as the "stabilized pinch". This concept added additional magnets to the outside of the chamber, which created a field that would be present in the plasma before the pinch discharge. In most concepts, the external field was relatively weak, and because a plasma is diamagnetic

Diamagnetic materials are repelled by a magnetic field; an applied magnetic field creates an induced magnetic field in them in the opposite direction, causing a repulsive force. In contrast, paramagnetic and ferromagnetic materials are attracted ...

, it penetrated only the outer areas of the plasma. When the pinch discharge occurred and the plasma quickly contracted, this field became "frozen in" to the resulting filament, creating a strong field in its outer layers. In the US, this was known as "giving the plasma a backbone."

Sakharov revisited his original toroidal concepts and came to a slightly different conclusion about how to stabilize the plasma. The layout would be the same as the stabilized pinch concept, but the role of the two fields would be reversed. Instead of weak external fields providing stabilization and a strong pinch current responsible for confinement, in the new layout, the external magnets would be much more powerful in order to provide the majority of confinement, while the current would be much smaller and responsible for the stabilizing effect.

Steps toward declassification

In 1955, with the linear approaches still subject to instability, the first toroidal device was built in the USSR. TMP was a classic pinch machine, similar to models in the UK and US of the same era. The vacuum chamber was made of ceramic, and the spectra of the discharges showed silica, meaning the plasma was not perfectly confined by magnetic field and hitting the walls of the chamber. Two smaller machines followed, using copper shells. The conductive shells were intended to help stabilize the plasma, but were not completely successful in any of the machines that tried it.

With progress apparently stalled, in 1955, Kurchatov called an All Union conference of Soviet researchers with the ultimate aim of opening up fusion research within the USSR. In April 1956, Kurchatov travelled to the UK as part of a widely publicized visit by

In 1955, with the linear approaches still subject to instability, the first toroidal device was built in the USSR. TMP was a classic pinch machine, similar to models in the UK and US of the same era. The vacuum chamber was made of ceramic, and the spectra of the discharges showed silica, meaning the plasma was not perfectly confined by magnetic field and hitting the walls of the chamber. Two smaller machines followed, using copper shells. The conductive shells were intended to help stabilize the plasma, but were not completely successful in any of the machines that tried it.

With progress apparently stalled, in 1955, Kurchatov called an All Union conference of Soviet researchers with the ultimate aim of opening up fusion research within the USSR. In April 1956, Kurchatov travelled to the UK as part of a widely publicized visit by Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

and Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Alexandrovich Bulganin (russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Булга́нин; – 24 February 1975) was a Soviet politician who served as Minister of Defense (1953–1955) and Premier of the Soviet Union (1955–19 ...

. He offered to give a talk at Atomic Energy Research Establishment, at the former RAF Harwell

Royal Air Force Harwell or more simply RAF Harwell is a former Royal Air Force station, near the village of Harwell, located south east of Wantage, Oxfordshire and north west of Reading, Berkshire, England.

The site is now the Harwell Sc ...

, where he shocked the hosts by presenting a detailed historical overview of the Soviet fusion efforts. He took time to note, in particular, the neutrons seen in early machines and warned that neutrons did not mean fusion.

Unknown to Kurchatov, the British ZETA

Zeta (, ; uppercase Ζ, lowercase ζ; grc, ζῆτα, el, ζήτα, label= Demotic Greek, classical or ''zē̂ta''; ''zíta'') is the sixth letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 7. It was derived f ...

stabilized pinch machine was being built at the far end of the former runway. ZETA was, by far, the largest and most powerful fusion machine to date. Supported by experiments on earlier designs that had been modified to include stabilization, ZETA intended to produce low levels of fusion reactions. This was apparently a great success, and in January 1958, they announced the fusion had been achieved in ZETA based on the release of neutrons and measurements of the plasma temperature.

Vitaly Shafranov

Vitaly Dmitrievich Shafranov (russian: Виталий Дмитриевич Шафранов; December 1, 1929 – June 9, 2014) was a Russian theoretical physicist and Academician who worked with plasma physics and thermonuclear fusion research.

...

and Stanislav Braginskii examined the news reports and attempted to figure out how it worked. One possibility they considered was the use of weak "frozen in" fields, but rejected this, believing the fields would not last long enough. They then concluded ZETA was essentially identical to the devices they had been studying, with strong external fields.

First tokamaks

By this time, Soviet researchers had decided to build a larger toroidal machine along the lines suggested by Sakharov. In particular, their design considered one important point found in Kruskal's and Shafranov's works; if the helical path of the particles made them circulate around the plasma's circumference more rapidly than they circulated the long axis of the torus, the kink instability would be strongly suppressed. Today this basic concept is known as the ''safety factor

In engineering, a factor of safety (FoS), also known as (and used interchangeably with) safety factor (SF), expresses how much stronger a system is than it needs to be for an intended load. Safety factors are often calculated using detailed analy ...

''. The ratio of the number of times the particle orbits the major axis compared to the minor axis is denoted ''q'', and the ''Kruskal-Shafranov Limit'' stated that the kink will be suppressed as long as ''q'' > 1. This path is controlled by the relative strengths of the external magnets compared to the field created by the internal current. To have ''q'' > 1, the external magnets must be much more powerful, or alternatively, the internal current has to be reduced.

Following this criterion, design began on a new reactor, T-1, which today is known as the first real tokamak. T-1 used both stronger external magnets and a reduced current compared to stabilized pinch machines like ZETA. The success of the T-1 resulted in its recognition as the first working tokamak.

For his work on "powerful impulse discharges in a gas, to obtain unusually high temperatures needed for thermonuclear processes", Yavlinskii was awarded the Lenin Prize and the Stalin Prize Stalin Prize may refer to:

* The State Stalin Prize in science and engineering and in arts, awarded 1941 to 1954, later known as the USSR State Prize

The USSR State Prize (russian: links=no, Государственная премия СССР, ...

in 1958. Yavlinskii was already preparing the design of an even larger model, later built as T-3. With the apparently successful ZETA announcement, Yavlinskii's concept was viewed very favourably.

Details of ZETA became public in a series of articles in ''Nature'' later in January. To Shafranov's surprise, the system did use the "frozen in" field concept. He remained sceptical, but a team at the Ioffe Institute

The Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (for short, Ioffe Institute, russian: Физико-технический институт им. А. Ф. Иоффе) is one of Russia's largest research centers specialized ...

in St. Petersberg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

began plans to build a similar machine known as Alpha. Only a few months later, in May, the ZETA team issued a release stating they had not achieved fusion, and that they had been misled by erroneous measures of the plasma temperature.

T-1 began operation at the end of 1958. It demonstrated very high energy losses through radiation. This was traced to impurities in the plasma due to the vacuum system causing outgassing from the container materials. In order to explore solutions to this problem, another small device was constructed, T-2. This used an internal liner of corrugated metal that was baked at to cook off trapped gasses.

Atoms for Peace and the doldrums

As part of the secondAtoms for Peace

"Atoms for Peace" was the title of a speech delivered by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly in New York City on December 8, 1953.

The United States then launched an "Atoms for Peace" program that supplied equipment ...

meeting in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

in September 1958, the Soviet delegation released many papers covering their fusion research. Among them was a set of initial results on their toroidal machines, which at that point had shown nothing of note.

The "star" of the show was a large model of Spitzer's stellarator, which immediately caught the attention of the Soviets. In contrast to their designs, the stellarator produced the required twisted paths in the plasma without driving a current through it, using a series of magnets that could operate in the steady state rather than the pulses of the induction system. Kurchatov began asking Yavlinskii to change their T-3 design to a stellarator, but they convinced him that the current provided a useful second role in heating, something the stellarator lacked.

At the time of the show, the stellarator had suffered a long string of minor problems that were just being solved. Solving these revealed that the diffusion rate of the plasma was much faster than theory predicted. Similar problems were seen in all the contemporary designs, for one reason or another. The stellarator, various pinch concepts and the magnetic mirror

A magnetic mirror, known as a magnetic trap (магнитный захват) in Russia and briefly as a pyrotron in the US, is a type of magnetic confinement device used in fusion power to trap high temperature plasma using magnetic fields. T ...

machines in both the US and USSR all demonstrated problems that limited their confinement times.

From the first studies of controlled fusion, there was a problem lurking in the background. During the Manhattan Project, David Bohm

David Joseph Bohm (; 20 December 1917 – 27 October 1992) was an American-Brazilian-British scientist who has been described as one of the most significant theoretical physicists of the 20th centuryPeat 1997, pp. 316-317 and who contributed ...

had been part of the team working on isotopic separation of uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

. In the post-war era he continued working with plasmas in magnetic fields. Using basic theory, one would expect the plasma to diffuse across the lines of force at a rate inversely proportional to the square of the strength of the field, meaning that small increases in force would greatly improve confinement. But based on their experiments, Bohm developed an empirical formula, now known as Bohm diffusion The diffusion of plasma across a magnetic field was conjectured to follow the Bohm diffusion scaling as indicated from the early plasma experiments of very lossy machines. This predicted that the rate of diffusion was linear with temperature and ...

, that suggested the rate was linear with the magnetic force, not its square.

If Bohm's formula was correct, there was no hope one could build a fusion reactor based on magnetic confinement. To confine the plasma at the temperatures needed for fusion, the magnetic field would have to be orders of magnitude greater than any known magnet. Spitzer ascribed the difference between the Bohm and classical diffusion rates to turbulence in the plasma, and believed the steady fields of the stellarator would not suffer from this problem. Various experiments at that time suggested the Bohm rate did not apply, and that the classical formula was correct.

But by the early 1960s, with all of the various designs leaking plasma at a prodigious rate, Spitzer himself concluded that the Bohm scaling was an inherent quality of plasmas, and that magnetic confinement would not work. The entire field descended into what became known as "the doldrums", a period of intense pessimism.

Progress in the 1960s

In contrast to the other designs, the experimental tokamaks appeared to be progressing well, so well that a minor theoretical problem was now a real concern. In the presence of gravity, there is a small pressure gradient in the plasma, formerly small enough to ignore but now becoming something that had to be addressed. This led to the addition of yet another set of magnets in 1962, which produced a vertical field that offset these effects. These were a success, and by the mid-1960s the machines began to show signs that they were beating the Bohm limit. At the 1965 SecondInternational Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was established in 1957 ...

Conference on fusion at the UK's newly opened Culham Centre for Fusion Energy

The Culham Centre for Fusion Energy (CCFE) is the UK's national laboratory for fusion research. It is located at the Culham Science Centre, near Culham, Oxfordshire, and is the site of the Joint European Torus (JET), Mega Ampere Spherical Tokam ...

, Artsimovich reported that their systems were surpassing the Bohm limit by 10 times. Spitzer, reviewing the presentations, suggested that the Bohm limit may still apply; the results were within the range of experimental error of results seen on the stellarators, and the temperature measurements, based on the magnetic fields, were simply not trustworthy.

The next major international fusion meeting was held in August 1968 in Novosibirsk

Novosibirsk (, also ; rus, Новосиби́рск, p=nəvəsʲɪˈbʲirsk, a=ru-Новосибирск.ogg) is the largest city and administrative centre of Novosibirsk Oblast and Siberian Federal District in Russia. As of the Russian Census ...

. By this time two additional tokamak designs had been completed, TM-2 in 1965, and T-4 in 1968. Results from T-3 had continued to improve, and similar results were coming from early tests of the new reactors. At the meeting, the Soviet delegation announced that T-3 was producing electron temperatures of 1000 eV (equivalent to 10 million degrees Celsius) and that confinement time was at least 50 times the Bohm limit.

These results were at least 10 times that of any other machine. If correct, they represented an enormous leap for the fusion community. Spitzer remained sceptical, noting that the temperature measurements were still based on the indirect calculations from the magnetic properties of the plasma. Many concluded they were due to an effect known as runaway electrons The term runaway electrons (RE) is used to denote electrons that undergo free fall acceleration into the realm of relativistic particles. REs may be classified as thermal (lower energy) or relativistic. The study of runaway electrons is thought to ...

, and that the Soviets were measuring only those extremely energetic electrons and not the bulk temperature. The Soviets countered with several arguments suggesting the temperature they were measuring was Maxwellian, and the debate raged.

Culham Five

In the aftermath of ZETA, the UK teams began the development of new plasma diagnostic tools to provide more accurate measurements. Among these was the use of alaser

A laser is a device that emits light through a process of optical amplification based on the stimulated emission of electromagnetic radiation. The word "laser" is an acronym for "light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation". The fir ...

to directly measure the temperature of the bulk electrons using Thomson scattering

Thomson scattering is the elastic scattering of electromagnetic radiation by a free charged particle, as described by classical electromagnetism. It is the low-energy limit of Compton scattering: the particle's kinetic energy and photon frequen ...

. This technique was well known and respected in the fusion community; Artsimovich had publicly called it "brilliant". Artsimovich invited Bas Pease

Rendel Sebastian "Bas" Pease FRS (2 November 1922 – 17 October 2004) was a British physicist who strongly opposed nuclear weapons while advocating the use of nuclear fusion as a clean source of power.

Biography

Pease was born at 9 Brunswick ...

, the head of Culham, to use their devices on the Soviet reactors. At the height of the cold war

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, in what is still considered a major political manoeuvre on Artsimovich's part, British physicists were allowed to visit the Kurchatov Institute, the heart of the Soviet nuclear bomb effort.

The British team, nicknamed "The Culham Five", arrived late in 1968. After a lengthy installation and calibration process, the team measured the temperatures over a period of many experimental runs. Initial results were available by August 1969; the Soviets were correct, their results were accurate. The team phoned the results home to Culham, who then passed them along in a confidential phone call to Washington. The final results were published in ''Nature'' in November 1969. The results of this announcement have been described as a "veritable stampede" of tokamak construction around the world.

One serious problem remained. Because the electrical current in the plasma was much lower and produced much less compression than a pinch machine, this meant the temperature of the plasma was limited to the resistive heating rate of the current. First proposed in 1950, Spitzer resistivity The Spitzer resistivity (or plasma resistivity) is an expression describing the electrical resistance in a plasma, which was first formulated by Lyman Spitzer in 1950. The Spitzer resistivity of a plasma decreases in proportion to the electron temp ...

stated that the electrical resistance

The electrical resistance of an object is a measure of its opposition to the flow of electric current. Its reciprocal quantity is , measuring the ease with which an electric current passes. Electrical resistance shares some conceptual parallels ...

of a plasma was reduced as the temperature increased, meaning the heating rate of the plasma would slow as the devices improved and temperatures were pressed higher. Calculations demonstrated that the resulting maximum temperatures while staying within ''q'' > 1 would be limited to the low millions of degrees. Artsimovich had been quick to point this out in Novosibirsk, stating that future progress would require new heating methods to be developed.

US turmoil

One of the people attending the Novosibirsk meeting in 1968 wasAmasa Stone Bishop

Amasa Stone Bishop (1921 – May 21, 1997) was an American nuclear physicist specializing in fusion physics. He received his B.S. in physics from the California Institute of Technology in 1943. From 1943 to 1946 he was a member of the staff of R ...

, one of the leaders of the US fusion program. One of the few other devices to show clear evidence of beating the Bohm limit at that time was the multipole

A multipole expansion is a Series (mathematics), mathematical series representing a Function (mathematics), function that depends on angles—usually the two angles used in the spherical coordinate system (the polar and Azimuth, azimuthal angles) f ...

concept. Both Lawrence Livermore and the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory

Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory for plasma physics and nuclear fusion science. Its primary mission is research into and development of fusion as an energy source. It is known ...

(PPPL), home of Spitzer's stellarator, were building variations on the multipole design. While moderately successful on their own, T-3 greatly outperformed either machine. Bishop was concerned that the multipoles were redundant and thought the US should consider a tokamak of its own.

When he raised the issue at a December 1968 meeting, directors of the labs refused to consider it. Melvin B. Gottlieb

Melvin Burt Gottlieb (May 25, 1917 in Chicago, Illinois – December 1, 2000 in Haverford Township, Pennsylvania) was a high-energy physicist and director of the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (1961–1980). With James Van Allen, Van Allen he ...

of Princeton was exasperated, asking "Do you think that this committee can out-think the scientists?" With the major labs demanding they control their own research, one lab found itself left out. Oak Ridge had originally entered the fusion field with studies for reactor fueling systems, but branched out into a mirror program of their own. By the mid-1960s, their DCX designs were running out of ideas, offering nothing that the similar program at the more prestigious and politically powerful Livermore didn't. This made them highly receptive to new concepts.

After a considerable internal debate, Herman Postma formed a small group in early 1969 to consider the tokamak. They came up with a new design, later christened Ormak, that had several novel features. Primary among them was the way the external field was created in a single large copper block, fed power from a large transformer

A transformer is a passive component that transfers electrical energy from one electrical circuit to another circuit, or multiple circuits. A varying current in any coil of the transformer produces a varying magnetic flux in the transformer' ...

below the torus. This was as opposed to traditional designs that used magnet windings on the outside. They felt the single block would produce a much more uniform field. It would also have the advantage of allowing the torus to have a smaller major radius, lacking the need to route cables through the donut hole, leading to a lower '' aspect ratio'', which the Soviets had already suggested would produce better results.

Tokamak race in the US

In early 1969, Artsimovich visitedMIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the m ...

, where he was hounded by those interested in fusion. He finally agreed to give several lectures in April and then allowed lengthy question-and-answer sessions. As these went on, MIT itself grew interested in the tokamak, having previously stayed out of the fusion field for a variety of reasons. Bruno Coppi

Bruno Coppi (born 19 November 1935 in Gonzaga, Lombardy, Italy) is an Italian-American physicist specializing in plasma physics.

In 1959, Coppi attained an Italian doctoral degree at Polytechnic University of Milan and was subsequently a docent ...

was at MIT at the time, and following the same concepts as Postma's team, came up with his own low-aspect-ratio concept, Alcator

Alcator C-Mod was a tokamak (a type of magnetically confined fusion device) that operated between 1991 and 2016 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Plasma Science and Fusion Center (PSFC). Notable for its high toroidal magnetic ...

. Instead of Ormak's toroidal transformer, Alcator used traditional ring-shaped magnets but required them to be much smaller than existing designs. MIT's Francis Bitter Magnet Laboratory

The MIT School of Science is one of the five schools of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. The School is composed of 6 academic departments who grant SB, SM, and PhD or ScD degrees; as ...

was the world leader in magnet design and they were confident they could build them.

During 1969, two additional groups entered the field. At General Atomics

General Atomics is an American energy and defense corporation headquartered in San Diego, California, specializing in research and technology development. This includes physics research in support of nuclear fission and nuclear fusion energy. The ...

, Tihiro Ohkawa

was a Japanese physicist whose field of work was in plasma physics and fusion power. He was a pioneer in developing ways to generate electricity by nuclear fusion when he worked at General Atomics. Ohkawa died September 27, 2014 in La Jolla, Cal ...

had been developing multipole reactors, and submitted a concept based on these ideas. This was a tokamak that would have a non-circular plasma cross-section; the same math that suggested a lower aspect-ratio would improve performance also suggested that a C or D-shaped plasma would do the same. He called the new design Doublet

Doublet is a word derived from the Latin ''duplus'', "twofold, twice as much",