Nucleophilic acyl substitution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nucleophilic acyl substitution describe a class of

This mechanism is supported by isotope labeling experiments. When ethyl propionate with an

This mechanism is supported by isotope labeling experiments. When ethyl propionate with an

A major factor in determining the reactivity of acyl derivatives is leaving group ability, which is related to acidity. Weak bases are better leaving groups than strong bases; a species with a strong

A major factor in determining the reactivity of acyl derivatives is leaving group ability, which is related to acidity. Weak bases are better leaving groups than strong bases; a species with a strong  Another factor that plays a role in determining the reactivity of acyl compounds is

Another factor that plays a role in determining the reactivity of acyl compounds is

Alcohols and

Alcohols and

Unlike most other carbon nucleophiles, lithium dialkylcuprates – often called

Unlike most other carbon nucleophiles, lithium dialkylcuprates – often called

First, DMAP (2) attacks the anhydride (1) to form a tetrahedral intermediate, which collapses to eliminate a carboxylate ion to give amide 3. This intermediate amide is more activated towards nucleophilic attack than the original anhydride, because dimethylaminopyridine is a better leaving group than a carboxylate. In the final set of steps, a nucleophile (Nuc) attacks 3 to give another tetrahedral intermediate. When this intermediate collapses to give the product 4, the pyridine group is eliminated and its aromaticity is restored – a powerful driving force, and the reason why the pyridine compound is a better leaving group than a carboxylate ion.

First, DMAP (2) attacks the anhydride (1) to form a tetrahedral intermediate, which collapses to eliminate a carboxylate ion to give amide 3. This intermediate amide is more activated towards nucleophilic attack than the original anhydride, because dimethylaminopyridine is a better leaving group than a carboxylate. In the final set of steps, a nucleophile (Nuc) attacks 3 to give another tetrahedral intermediate. When this intermediate collapses to give the product 4, the pyridine group is eliminated and its aromaticity is restored – a powerful driving force, and the reason why the pyridine compound is a better leaving group than a carboxylate ion.

Basic hydrolysis of esters, known as

Basic hydrolysis of esters, known as  Crossed Claisen condensations, in which the enolate and nucleophile are different esters, are also possible. An intramolecular Claisen condensation is called a

Crossed Claisen condensations, in which the enolate and nucleophile are different esters, are also possible. An intramolecular Claisen condensation is called a

Here, phenyllithium 1 attacks the carbonyl group of DMF 2, giving tetrahedral intermediate 3. Because the dimethylamide anion is a poor leaving group, the intermediate does not collapse and another nucleophilic addition does not occur. Upon acidic workup, the alkoxide is protonated to give 4, then the amine is protonated to give 5. Elimination of a neutral molecule of

Here, phenyllithium 1 attacks the carbonyl group of DMF 2, giving tetrahedral intermediate 3. Because the dimethylamide anion is a poor leaving group, the intermediate does not collapse and another nucleophilic addition does not occur. Upon acidic workup, the alkoxide is protonated to give 4, then the amine is protonated to give 5. Elimination of a neutral molecule of

Phosphorus(III) chloride (PCl3) and phosphorus(V) chloride (PCl5) will also convert carboxylic acids to acid chlorides, by a similar mechanism. One equivalent of PCl3 can react with three equivalents of acid, producing one equivalent of H3PO3, or phosphorus acid, in addition to the desired acid chloride. PCl5 reacts with carboxylic acids in a 1:1 ratio, and produces phosphorus(V) oxychloride (POCl3) and hydrogen chloride (HCl) as byproducts.

Carboxylic acids react with Grignard reagents and organolithiums to form ketones. The first equivalent of nucleophile acts as a base and deprotonates the acid. A second equivalent will attack the carbonyl group to create a

Phosphorus(III) chloride (PCl3) and phosphorus(V) chloride (PCl5) will also convert carboxylic acids to acid chlorides, by a similar mechanism. One equivalent of PCl3 can react with three equivalents of acid, producing one equivalent of H3PO3, or phosphorus acid, in addition to the desired acid chloride. PCl5 reacts with carboxylic acids in a 1:1 ratio, and produces phosphorus(V) oxychloride (POCl3) and hydrogen chloride (HCl) as byproducts.

Carboxylic acids react with Grignard reagents and organolithiums to form ketones. The first equivalent of nucleophile acts as a base and deprotonates the acid. A second equivalent will attack the carbonyl group to create a

Article

{{Reaction mechanisms Nucleophilic substitution reactions Reaction mechanisms

substitution reaction

A substitution reaction (also known as single displacement reaction or single substitution reaction) is a chemical reaction during which one functional group in a chemical compound is replaced by another functional group. Substitution reactions ar ...

s involving nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they ar ...

s and acyl

In chemistry, an acyl group is a moiety derived by the removal of one or more hydroxyl groups from an oxoacid, including inorganic acids. It contains a double-bonded oxygen atom and an alkyl group (). In organic chemistry, the acyl group (IUPAC ...

compounds. In this type of reaction, a nucleophile – such as an alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

, amine

In chemistry, amines (, ) are compounds and functional groups that contain a basic nitrogen atom with a lone pair. Amines are formally derivatives of ammonia (), wherein one or more hydrogen atoms have been replaced by a substituent ...

, or enolate

In organic chemistry, enolates are organic anions derived from the deprotonation of carbonyl () compounds. Rarely isolated, they are widely used as reagents in the synthesis of organic compounds.

Bonding and structure

Enolate anions are electr ...

– displaces the leaving group In chemistry, a leaving group is defined by the IUPAC as an atom or group of atoms that detaches from the main or residual part of a substrate during a reaction or elementary step of a reaction. However, in common usage, the term is often limited ...

of an acyl derivative – such as an acid halide, anhydride

An organic acid anhydride is an acid anhydride that is an organic compound. An acid anhydride is a compound that has two acyl groups bonded to the same oxygen atom. A common type of organic acid anhydride is a carboxylic anhydride, where the pa ...

, or ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an oxoacid (organic or inorganic) in which at least one hydroxyl group () is replaced by an alkoxy group (), as in the substitution reaction of a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Glycerides ...

. The resulting product is a carbonyl

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group composed of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom: C=O. It is common to several classes of organic compounds, as part of many larger functional groups. A compound containi ...

-containing compound in which the nucleophile has taken the place of the leaving group present in the original acyl derivative. Because acyl derivatives react with a wide variety of nucleophiles, and because the product can depend on the particular type of acyl derivative and nucleophile involved, nucleophilic acyl substitution reactions can be used to synthesize a variety of different products.

Reaction mechanism

Carbonyl compounds react with nucleophiles via an addition mechanism: the nucleophile attacks the carbonyl carbon, forming atetrahedral intermediate

A tetrahedral intermediate is a reaction intermediate in which the bond arrangement around an initially double-bonded carbon atom has been transformed from trigonal to tetrahedral. Tetrahedral intermediates result from nucleophilic addition to a ...

. This reaction can be accelerated by acid

In computer science, ACID ( atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps. In the context of databases, a se ...

ic conditions, which make the carbonyl more electrophilic

In chemistry, an electrophile is a chemical species that forms bonds with nucleophiles by accepting an electron pair. Because electrophiles accept electrons, they are Lewis acids. Most electrophiles are positively charged, have an atom that carr ...

, or basic

BASIC (Beginners' All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) is a family of general-purpose, high-level programming languages designed for ease of use. The original version was created by John G. Kemeny and Thomas E. Kurtz at Dartmouth College ...

conditions, which provide a more anion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conve ...

ic and therefore more reactive nucleophile. The tetrahedral intermediate itself can be an alcohol or alkoxide

In chemistry, an alkoxide is the conjugate base of an alcohol and therefore consists of an organic group bonded to a negatively charged oxygen atom. They are written as , where R is the organic substituent. Alkoxides are strong bases and, whe ...

, depending on the pH of the reaction.

The tetrahedral intermediate of an acyl

In chemistry, an acyl group is a moiety derived by the removal of one or more hydroxyl groups from an oxoacid, including inorganic acids. It contains a double-bonded oxygen atom and an alkyl group (). In organic chemistry, the acyl group (IUPAC ...

compound contains a substituent

A substituent is one or a group of atoms that replaces (one or more) atoms, thereby becoming a moiety in the resultant (new) molecule. (In organic chemistry and biochemistry, the terms ''substituent'' and ''functional group'', as well as '' side ...

attached to the central carbon that can act as a leaving group In chemistry, a leaving group is defined by the IUPAC as an atom or group of atoms that detaches from the main or residual part of a substrate during a reaction or elementary step of a reaction. However, in common usage, the term is often limited ...

. After the tetrahedral intermediate forms, it collapses, recreating the carbonyl C=O bond and ejecting the leaving group in an elimination reaction

An elimination reaction is a type of organic reaction in which two substituents are removed from a molecule in either a one- or two-step mechanism. The one-step mechanism is known as the E2 reaction, and the two-step mechanism is known as the E1 r ...

. As a result of this two-step addition/elimination process, the nucleophile takes the place of the leaving group on the carbonyl compound by way of an intermediate state that does not contain a carbonyl. Both steps are reversible and as a result, nucleophilic acyl substitution reactions are equilibrium processes. Because the equilibrium will favor the product containing the best nucleophile, the leaving group must be a comparatively poor nucleophile in order for a reaction to be practical.

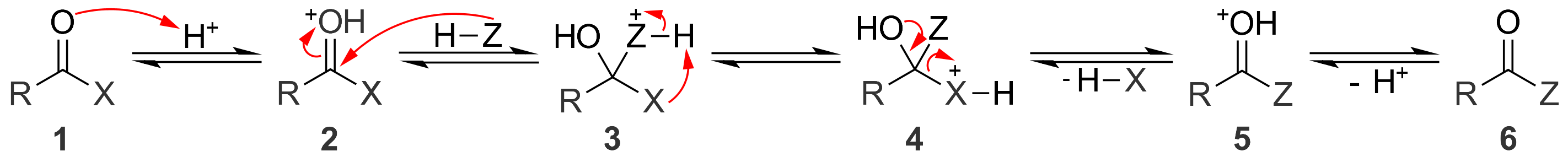

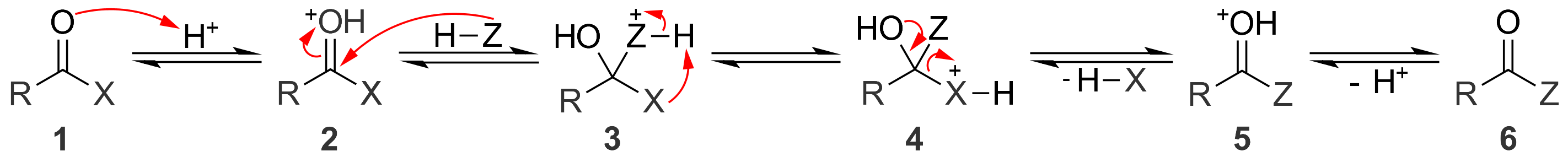

Acidic conditions

Under acidic conditions, the carbonyl group of the acyl compound 1 is protonated, which activates it towards nucleophilic attack. In the second step, the protonated carbonyl 2 is attacked by a nucleophile (H−Z) to give tetrahedral intermediate 3. Proton transfer from the nucleophile (Z) to the leaving group (X) gives 4, which then collapses to eject the protonated leaving group (H−X), giving protonated carbonyl compound 5. The loss of a proton gives the substitution product, 6. Because the last step involves the loss of a proton, nucleophilic acyl substitution reactions are considered catalytic in acid. Also note that under acidic conditions, a nucleophile will typically exist in its protonated form (i.e. H−Z instead of Z−).

Basic conditions

Underbasic

BASIC (Beginners' All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) is a family of general-purpose, high-level programming languages designed for ease of use. The original version was created by John G. Kemeny and Thomas E. Kurtz at Dartmouth College ...

conditions, a nucleophile (Nuc) attacks the carbonyl group of the acyl compound 1 to give tetrahedral alkoxide intermediate 2. The intermediate collapses and expels the leaving group (X) to give the substitution product 3. While nucleophilic acyl substitution reactions can be base-catalyzed, the reaction will not occur if the leaving group is a stronger base than the nucleophile (i.e. the leaving group must have a higher p''K''a than the nucleophile). Unlike acid-catalyzed processes, both the nucleophile and the leaving group exist as anions under basic conditions.

This mechanism is supported by isotope labeling experiments. When ethyl propionate with an

This mechanism is supported by isotope labeling experiments. When ethyl propionate with an oxygen-18

Oxygen-18 (, Ω) is a natural, stable isotope of oxygen and one of the environmental isotopes.

is an important precursor for the production of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) used in positron emission tomography (PET). Generally, in the radiopharmaceu ...

-labeled ethoxy group is treated with sodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula NaOH. It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly caustic base and al ...

(NaOH), the oxygen-18 label is completely absent from propionic acid

Propionic acid (, from the Greek words πρῶτος : ''prōtos'', meaning "first", and πίων : ''píōn'', meaning "fat"; also known as propanoic acid) is a naturally occurring carboxylic acid with chemical formula CH3CH2CO2H. It is a li ...

and is found exclusively in the ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl group linked to a ...

.

Reactivity trends

There are five main types of acyl derivatives. Acid halides are the most reactive towards nucleophiles, followed byanhydride

An organic acid anhydride is an acid anhydride that is an organic compound. An acid anhydride is a compound that has two acyl groups bonded to the same oxygen atom. A common type of organic acid anhydride is a carboxylic anhydride, where the pa ...

s, ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an oxoacid (organic or inorganic) in which at least one hydroxyl group () is replaced by an alkoxy group (), as in the substitution reaction of a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Glycerides ...

s, and amide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent organic groups or hydrogen atoms. The amide group is called a peptide bond when it i ...

s. Carboxylate

In organic chemistry, a carboxylate is the conjugate base of a carboxylic acid, (or ). It is an ion with negative charge.

Carboxylate salts are salts that have the general formula , where M is a metal and ''n'' is 1, 2,...; ''carboxylat ...

ions are essentially unreactive towards nucleophilic substitution, since they possess no leaving group. The reactivity of these five classes of compounds covers a broad range; the relative reaction rates of acid chlorides and amides differ by a factor of 1013.

A major factor in determining the reactivity of acyl derivatives is leaving group ability, which is related to acidity. Weak bases are better leaving groups than strong bases; a species with a strong

A major factor in determining the reactivity of acyl derivatives is leaving group ability, which is related to acidity. Weak bases are better leaving groups than strong bases; a species with a strong conjugate acid

A conjugate acid, within the Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, is a chemical compound formed when an acid donates a proton () to a base—in other words, it is a base with a hydrogen ion added to it, as in the reverse reaction it loses a ...

(e.g. hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride. It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid. It is a component of the gastric acid in the dige ...

) will be a better leaving group than a species with a weak conjugate acid (e.g. acetic acid

Acetic acid , systematically named ethanoic acid , is an acidic, colourless liquid and organic compound with the chemical formula (also written as , , or ). Vinegar is at least 4% acetic acid by volume, making acetic acid the main componen ...

). Thus, chloride

The chloride ion is the anion (negatively charged ion) Cl−. It is formed when the element chlorine (a halogen) gains an electron or when a compound such as hydrogen chloride is dissolved in water or other polar solvents. Chloride s ...

ion is a better leaving group than acetate ion

An acetate is a salt formed by the combination of acetic acid with a base (e.g. alkaline, earthy, metallic, nonmetallic or radical base). "Acetate" also describes the conjugate base or ion (specifically, the negatively charged ion called an ...

. The reactivity of acyl compounds towards nucleophiles decreases as the basicity of the leaving group increases, as the table shows.Wade 2010, pp. 998–999.

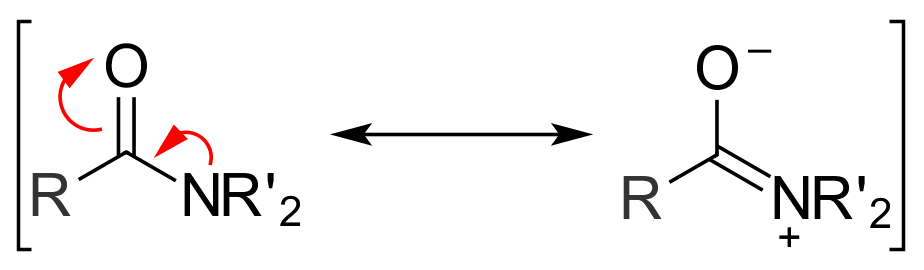

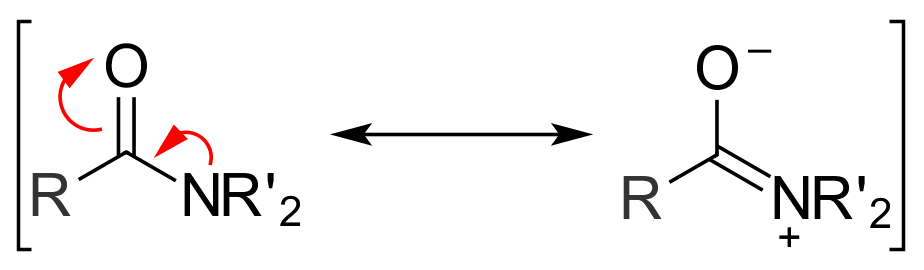

Another factor that plays a role in determining the reactivity of acyl compounds is

Another factor that plays a role in determining the reactivity of acyl compounds is resonance

Resonance describes the phenomenon of increased amplitude that occurs when the frequency of an applied periodic force (or a Fourier component of it) is equal or close to a natural frequency of the system on which it acts. When an oscil ...

. Amides exhibit two main resonance forms. Both are major contributors to the overall structure, so much so that the amide bond between the carbonyl carbon and the amide nitrogen has significant double bond

In chemistry, a double bond is a covalent bond between two atoms involving four bonding electrons as opposed to two in a single bond. Double bonds occur most commonly between two carbon atoms, for example in alkenes. Many double bonds exist betwee ...

character. The energy barrier

In chemistry and physics, activation energy is the minimum amount of energy that must be provided for compounds to result in a chemical reaction. The activation energy (''E''a) of a reaction is measured in joules per mole (J/mol), kilojoules pe ...

for rotation about an amide bond is 75–85 kJ/mol (18–20 kcal/mol), much larger than values observed for normal single bonds. For example, the C–C bond in ethane has an energy barrier of only 12 kJ/mol (3 kcal/mol). Once a nucleophile attacks and a tetrahedral intermediate is formed, the energetically favorable resonance effect is lost. This helps explain why amides are one of the least reactive acyl derivatives.

Esters exhibit less resonance stabilization than amides, so the formation of a tetrahedral intermediate and subsequent loss of resonance is not as energetically unfavorable. Anhydrides experience even weaker resonance stabilization, since the resonance is split between two carbonyl groups, and are more reactive than esters and amides. In acid halides, there is very little resonance, so the energetic penalty for forming a tetrahedral intermediate is small. This helps explain why acid halides are the most reactive acyl derivatives.

Reactions of acyl derivatives

Many nucleophilic acyl substitution reactions involve converting one acyl derivative into another. In general, conversions between acyl derivatives must proceed from a relatively reactive compound to a less reactive one to be practical; an acid chloride can easily be converted to an ester, but converting an ester directly to an acid chloride is essentially impossible. When converting between acyl derivatives, the product will always be more stable than the starting compound. Nucleophilic acyl substitution reactions that do not involve interconversion between acyl derivatives are also possible. For example, amides and carboxylic acids react withGrignard reagent

A Grignard reagent or Grignard compound is a chemical compound with the general formula , where X is a halogen and R is an organic group, normally an alkyl or aryl. Two typical examples are methylmagnesium chloride and phenylmagnesium bromide . ...

s to produce ketones. An overview of the reactions that each type of acyl derivative can participate in is presented here.

Acid halides

Acid halides are the most reactive acyl derivatives, and can easily be converted into any of the others. Acid halides will react with carboxylic acids to form anhydrides. If the structure of the acid and the acid chloride are different, the product is a mixed anhydride. First, the carboxylic acid attacks the acid chloride (1) to give tetrahedral intermediate 2. The tetrahedral intermediate collapses, ejecting chloride ion as the leaving group and forming oxonium species 3. Deprotonation gives the mixed anhydride, 4, and an equivalent of HCl. Alcohols and

Alcohols and amine

In chemistry, amines (, ) are compounds and functional groups that contain a basic nitrogen atom with a lone pair. Amines are formally derivatives of ammonia (), wherein one or more hydrogen atoms have been replaced by a substituent ...

s react with acid halides to produce ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an oxoacid (organic or inorganic) in which at least one hydroxyl group () is replaced by an alkoxy group (), as in the substitution reaction of a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Glycerides ...

s and amide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent organic groups or hydrogen atoms. The amide group is called a peptide bond when it i ...

s, respectively, in a reaction formally known as the Schotten-Baumann reaction. Acid halides hydrolyze in the presence of water to produce carboxylic acids, but this type of reaction is rarely useful, since carboxylic acids are typically used to synthesize acid halides. Most reactions with acid halides are carried out in the presence of a non-nucleophilic base, such as pyridine

Pyridine is a basic heterocyclic organic compound with the chemical formula . It is structurally related to benzene, with one methine group replaced by a nitrogen atom. It is a highly flammable, weakly alkaline, water-miscible liquid w ...

, to neutralize the hydrohalic acid that is formed as a byproduct.

Acid halides will react with carbon nucleophiles, such as Grignards and enolate

In organic chemistry, enolates are organic anions derived from the deprotonation of carbonyl () compounds. Rarely isolated, they are widely used as reagents in the synthesis of organic compounds.

Bonding and structure

Enolate anions are electr ...

s, though mixtures of products can result. While a carbon nucleophile will react with the acid halide first to produce a ketone, the ketone is also susceptible to nucleophilic attack, and can be converted to a tertiary alcohol. For example, when benzoyl chloride (1) is treated with two equivalents of a Grignard reagent, such as methyl magnesium bromide (MeMgBr), 2-phenyl-2-propanol (3) is obtained in excellent yield. Although acetophenone

Acetophenone is the organic compound with the chemical formula, formula C6H5C(O)CH3. It is the simplest aromatic ketone. This colorless, viscous liquid is a precursor to useful resins and fragrances.

Production

Acetophenone is formed as a byprodu ...

(2) is an intermediate in this reaction, it is impossible to isolate because it reacts with a second equivalent of MeMgBr rapidly after being formed.

Gilman reagent

A Gilman reagent is a lithium and copper ( diorganocopper) reagent compound, R2CuLi, where R is an alkyl or aryl. These reagents are useful because, unlike related Grignard reagents and organolithium reagents, they react with organic halides to ...

s – can add to acid halides just once to give ketones. The reaction between an acid halide and a Gilman reagent is not a nucleophilic acyl substitution reaction, however, and is thought to proceed via a radical pathway. The Weinreb ketone synthesis

The Weinreb–Nahm ketone synthesis is a chemical reaction used in organic chemistry to make carbon–carbon bonds. It was discovered in 1981 by Steven M. Weinreb and Steven Nahm as a method to synthesize ketones. The original reaction involved ...

can also be used to convert acid halides to ketones. In this reaction, the acid halide is first converted to an N–methoxy–N–methylamide, known as a Weinreb amide. When a carbon nucleophile – such as a Grignard or organolithium

In organometallic chemistry, organolithium reagents are chemical compounds that contain carbon–lithium (C–Li) bonds. These reagents are important in organic synthesis, and are frequently used to transfer the organic group or the lithium atom ...

reagent – adds to a Weinreb amide, the metal is chelated

Chelation is a type of bonding of ions and molecules to metal ions. It involves the formation or presence of two or more separate coordinate bonds between a polydentate (multiple bonded) ligand and a single central metal atom. These ligands are ...

by the carbonyl and N–methoxy oxygens, preventing further nucleophilic additions.

In the Friedel–Crafts acylation, acid halides act as electrophiles for electrophilic aromatic substitution

Electrophilic aromatic substitution is an organic reaction in which an atom that is attached to an aromatic system (usually hydrogen) is replaced by an electrophile. Some of the most important electrophilic aromatic substitutions are aromatic n ...

. A Lewis acid

A Lewis acid (named for the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis) is a chemical species that contains an empty orbital which is capable of accepting an electron pair from a Lewis base to form a Lewis adduct. A Lewis base, then, is any sp ...

– such as zinc chloride

Zinc chloride is the name of inorganic chemical compounds with the formula ZnCl2 and its hydrates. Zinc chlorides, of which nine crystalline forms are known, are colorless or white, and are highly soluble in water. This salt is hygroscopic ...

(ZnCl2), iron(III) chloride

Iron(III) chloride is the inorganic compound with the formula . Also called ferric chloride, it is a common compound of iron in the +3 oxidation state. The anhydrous compound is a crystalline solid with a melting point of 307.6 °C. The col ...

(FeCl3), or aluminum chloride

Aluminium chloride, also known as aluminium trichloride, is an inorganic compound with the formula . It forms hexahydrate with the formula , containing six water molecules of hydration. Both are colourless crystals, but samples are often contam ...

(AlCl3) – coordinates to the halogen on the acid halide, activating the compound towards nucleophilic attack by an activated

"Activated" is a song by English singer Cher Lloyd. It was released on 22 July 2016 through Vixen Records. The song was made available to stream exclusively on ''Rolling Stone'' a day before to release (on 21 July 2016).

Background

In an inter ...

aromatic ring. For especially electron-rich aromatic rings, the reaction will proceed without a Lewis acid.Kürti and Czakó 2005, p. 176.

Thioesters

The chemistry of thioesters and acid halides is similar, the reactivity being reminiscent of, but milder, than acid chlorides.Anhydrides

The chemistry of acid halides and anhydrides is similar. While anhydrides cannot be converted to acid halides, they can be converted to the remaining acyl derivatives. Anhydrides also participate in Schotten–Baumann-type reactions to furnish esters and amides from alcohols and amines, and water can hydrolyze anhydrides to their corresponding acids. As with acid halides, anhydrides can also react with carbon nucleophiles to furnish ketones and/or tertiary alcohols, and can participate in both the Friedel–Crafts acylation and the Weinreb ketone synthesis. Unlike acid halides, however, anhydrides do not react with Gilman reagents. The reactivity of anhydrides can be increased by using a catalytic amount of N,N-dimethylaminopyridine, or DMAP.Pyridine

Pyridine is a basic heterocyclic organic compound with the chemical formula . It is structurally related to benzene, with one methine group replaced by a nitrogen atom. It is a highly flammable, weakly alkaline, water-miscible liquid w ...

can also be used for this purpose, and acts via a similar mechanism.

First, DMAP (2) attacks the anhydride (1) to form a tetrahedral intermediate, which collapses to eliminate a carboxylate ion to give amide 3. This intermediate amide is more activated towards nucleophilic attack than the original anhydride, because dimethylaminopyridine is a better leaving group than a carboxylate. In the final set of steps, a nucleophile (Nuc) attacks 3 to give another tetrahedral intermediate. When this intermediate collapses to give the product 4, the pyridine group is eliminated and its aromaticity is restored – a powerful driving force, and the reason why the pyridine compound is a better leaving group than a carboxylate ion.

First, DMAP (2) attacks the anhydride (1) to form a tetrahedral intermediate, which collapses to eliminate a carboxylate ion to give amide 3. This intermediate amide is more activated towards nucleophilic attack than the original anhydride, because dimethylaminopyridine is a better leaving group than a carboxylate. In the final set of steps, a nucleophile (Nuc) attacks 3 to give another tetrahedral intermediate. When this intermediate collapses to give the product 4, the pyridine group is eliminated and its aromaticity is restored – a powerful driving force, and the reason why the pyridine compound is a better leaving group than a carboxylate ion.

Esters

Esters are less reactive than acid halides and anhydrides. As with more reactive acyl derivatives, they can react withammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous ...

and primary and secondary amines to give amides, though this type of reaction is not often used, since acid halides give better yields. Esters can be converted to other esters in a process known as transesterification

In organic chemistry, transesterification is the process of exchanging the organic group R″ of an ester with the organic group R' of an alcohol. These reactions are often catalyzed by the addition of an acid or base catalyst. The reaction ca ...

. Transesterification can be either acid- or base-catalyzed, and involves the reaction of an ester with an alcohol. Unfortunately, because the leaving group is also an alcohol, the forward and reverse reactions will often occur at similar rates. Using a large excess of the reactant

In chemistry, a reagent ( ) or analytical reagent is a substance or compound added to a system to cause a chemical reaction, or test if one occurs. The terms ''reactant'' and ''reagent'' are often used interchangeably, but reactant specifies a ...

alcohol or removing the leaving group alcohol (e.g. via distillation

Distillation, or classical distillation, is the process of separating the components or substances from a liquid mixture by using selective boiling and condensation, usually inside an apparatus known as a still. Dry distillation is the he ...

) will drive the forward reaction towards completion, in accordance with Le Chatelier's principle

Le Chatelier's principle (pronounced or ), also called Chatelier's principle (or the Equilibrium Law), is a principle of chemistry used to predict the effect of a change in conditions on chemical equilibria. The principle is named after French ...

.Wade 2010, pp. 1005–1009.

Acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of esters is also an equilibrium process – essentially the reverse of the Fischer esterification

Fischer is a German occupational surname, meaning fisherman. The name Fischer is the fourth most common German surname. The English version is Fisher.

People with the surname A

* Abraham Fischer (1850–1913) South African public official

* ...

reaction. Because an alcohol (which acts as the leaving group) and water (which acts as the nucleophile) have similar p''K''a values, the forward and reverse reactions compete with each other. As in transesterification, using a large excess of reactant (water) or removing one of the products (the alcohol) can promote the forward reaction.

saponification

Saponification is a process of converting esters into soaps and alcohols by the action of aqueous alkali (for example, aqueous sodium hydroxide solutions). Soaps are salts of fatty acids, which in turn are carboxylic acids with long carbon chains. ...

, is not an equilibrium process; a full equivalent of base is consumed in the reaction, which produces one equivalent of alcohol and one equivalent of a carboxylate salt. The saponification of esters of fatty acid

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, f ...

s is an industrially important process, used in the production of soap.

Esters can undergo a variety of reactions with carbon nucleophiles. As with acid halides and anhyrides, they will react with an excess of a Grignard reagent to give tertiary alcohols. Esters also react readily with enolate

In organic chemistry, enolates are organic anions derived from the deprotonation of carbonyl () compounds. Rarely isolated, they are widely used as reagents in the synthesis of organic compounds.

Bonding and structure

Enolate anions are electr ...

s. In the Claisen condensation

The Claisen condensation is a carbon–carbon bond forming reaction that occurs between two esters or one ester and another carbonyl compound in the presence of a strong base, resulting in a β-keto ester or a β-diketone. It is named after Ra ...

, an enolate of one ester (1) will attack the carbonyl group of another ester (2) to give tetrahedral intermediate 3. The intermediate collapses, forcing out an alkoxide (R'O−) and producing β-keto ester 4.

Dieckmann condensation

The Dieckmann condensation is the intramolecular chemical reaction of diesters with base to give β-keto esters. It is named after the German chemist Walter Dieckmann (1869–1925). The equivalent intermolecular reaction is the Claisen condensat ...

or Dieckmann cyclization, since it can be used to form rings. Esters can also undergo condensations with ketone and aldehyde enolates to give β-dicarbonyl compounds. A specific example of this is the Baker–Venkataraman rearrangement The Baker–Venkataraman rearrangement is the chemical reaction of 2-acetoxyacetophenones with base to form 1,3-di ketones.

This rearrangement reaction proceeds via enolate formation followed by acyl transfer. It is named after the scientists Wil ...

, in which an aromatic ''ortho''-acyloxy ketone undergoes an intramolecular nucleophilic acyl substitution and subsequent rearrangement to form an aromatic β-diketone. The Chan rearrangement The Chan rearrangement is a chemical reaction that involves rearranging an acyloxy acetate (1) in the presence of a strong base to a 2-hydroxy-3-keto-ester (2).

This procedure was employed in the Holton Taxol total synthesis.

Reaction mecha ...

is another example of a rearrangement resulting from an intramolecular nucleophilic acyl substitution reaction.

Amides

Because of their low reactivity,amide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent organic groups or hydrogen atoms. The amide group is called a peptide bond when it i ...

s do not participate in nearly as many nucleophilic substitution reactions as other acyl derivatives do. Amides are stable to water, and are roughly 100 times more stable towards hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water is the nucleophile.

Biological hydrolysi ...

than esters. Amides can, however, be hydrolyzed to carboxylic acids in the presence of acid or base. The stability of amide bonds

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 ( carbon number one) of one alpha-amino acid and N2 (nitrogen number two) of another, along a peptide or protein ...

has biological implications, since the amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ...

s that make up protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

s are linked with amide bonds. Amide bonds are resistant enough to hydrolysis to maintain protein structure in aqueous

An aqueous solution is a solution in which the solvent is water. It is mostly shown in chemical equations by appending (aq) to the relevant chemical formula. For example, a solution of table salt, or sodium chloride (NaCl), in water would be re ...

environments, but are susceptible enough that they can be broken when necessary.

Primary and secondary amides do not react favorably with carbon nucleophiles. Grignard reagent

A Grignard reagent or Grignard compound is a chemical compound with the general formula , where X is a halogen and R is an organic group, normally an alkyl or aryl. Two typical examples are methylmagnesium chloride and phenylmagnesium bromide . ...

s and organolithiums will act as bases rather than nucleophiles, and will simply deprotonate the amide. Tertiary amides do not experience this problem, and react with carbon nucleophiles to give ketone

In organic chemistry, a ketone is a functional group with the structure R–C(=O)–R', where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group –C(=O)– (which contains a carbon-oxygen double b ...

s; the amide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent organic groups or hydrogen atoms. The amide group is called a peptide bond when it i ...

anion (NR2−) is a very strong base and thus a very poor leaving group, so nucleophilic attack only occurs once. When reacted with carbon nucleophiles, ''N'',''N''-dimethylformamide (DMF) can be used to introduce a formyl group.

Here, phenyllithium 1 attacks the carbonyl group of DMF 2, giving tetrahedral intermediate 3. Because the dimethylamide anion is a poor leaving group, the intermediate does not collapse and another nucleophilic addition does not occur. Upon acidic workup, the alkoxide is protonated to give 4, then the amine is protonated to give 5. Elimination of a neutral molecule of

Here, phenyllithium 1 attacks the carbonyl group of DMF 2, giving tetrahedral intermediate 3. Because the dimethylamide anion is a poor leaving group, the intermediate does not collapse and another nucleophilic addition does not occur. Upon acidic workup, the alkoxide is protonated to give 4, then the amine is protonated to give 5. Elimination of a neutral molecule of dimethylamine

Dimethylamine is an organic compound with the formula (CH3)2NH. This secondary amine is a colorless, flammable gas with an ammonia-like odor. Dimethylamine is commonly encountered commercially as a solution in water at concentrations up to arou ...

and loss of a proton give benzaldehyde, 6.

Carboxylic acids

Carboxylic acid

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is or , with R referring to the alkyl, alkenyl, aryl, or other group. Carboxyli ...

s are not especially reactive towards nucleophilic substitution, though they can be converted to other acyl derivatives. Converting a carboxylic acid to an amide is possible, but not straightforward. Instead of acting as a nucleophile, an amine will react as a base in the presence of a carboxylic acid to give the ammonium carboxylate

In organic chemistry, a carboxylate is the conjugate base of a carboxylic acid, (or ). It is an ion with negative charge.

Carboxylate salts are salts that have the general formula , where M is a metal and ''n'' is 1, 2,...; ''carboxylat ...

salt. Heating the salt to above 100 °C will drive off water and lead to the formation of the amide. This method of synthesizing amides is industrially important, and has laboratory applications as well.Wade 2010, pp. 964–965. In the presence of a strong acid catalyst, carboxylic acids can condense

Condensation is the change of the state of matter from the gas phase into the liquid phase, and is the reverse of vaporization. The word most often refers to the water cycle. It can also be defined as the change in the state of water vapor to ...

to form acid anhydrides. The condensation produces water, however, which can hydrolyze the anhydride back to the starting carboxylic acids. Thus, the formation of the anhydride via condensation is an equilibrium process.

Under acid-catalyzed conditions, carboxylic acids will react with alcohols to form ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an oxoacid (organic or inorganic) in which at least one hydroxyl group () is replaced by an alkoxy group (), as in the substitution reaction of a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Glycerides ...

s via the Fischer esterification

Fischer is a German occupational surname, meaning fisherman. The name Fischer is the fourth most common German surname. The English version is Fisher.

People with the surname A

* Abraham Fischer (1850–1913) South African public official

* ...

reaction, which is also an equilibrium process. Alternatively, diazomethane

Diazomethane is the chemical compound CH2N2, discovered by German chemist Hans von Pechmann in 1894. It is the simplest diazo compound. In the pure form at room temperature, it is an extremely sensitive explosive yellow gas; thus, it is almost ...

can be used to convert an acid to an ester. While esterification reactions with diazomethane often give quantitative yields, diazomethane is only useful for forming methyl esters.

Thionyl chloride

Thionyl chloride is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a moderately volatile, colourless liquid with an unpleasant acrid odour. Thionyl chloride is primarily used as a chlorinating reagent, with approximately per year bein ...

can be used to convert carboxylic acids to their corresponding acyl chlorides. First, carboxylic acid 1 attacks thionyl chloride, and chloride ion leaves. The resulting oxonium ion

In chemistry, an oxonium ion is any cation containing an oxygen atom that has three bonds and 1+ formal charge. The simplest oxonium ion is the hydronium ion ().

Alkyloxonium

Hydronium is one of a series of oxonium ions with the formula R''n'' ...

2 is activated towards nucleophilic attack and has a good leaving group, setting it apart from a normal carboxylic acid. In the next step, 2 is attacked by chloride ion to give tetrahedral intermediate 3, a chlorosulfite. The tetrahedral intermediate collapses with the loss of sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide (IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a toxic gas responsible for the odor of burnt matches. It is released naturally by volcanic a ...

and chloride ion, giving protonated acyl chloride 4. Chloride ion can remove the proton on the carbonyl group, giving the acyl chloride 5 with a loss of HCl HCL may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Hairy cell leukemia, an uncommon and slowly progressing B cell leukemia

* Harvard Cyclotron Laboratory, from 1961 to 2002, a proton accelerator used for research and development

* Hollow-cathode lamp, a s ...

.

Phosphorus(III) chloride (PCl3) and phosphorus(V) chloride (PCl5) will also convert carboxylic acids to acid chlorides, by a similar mechanism. One equivalent of PCl3 can react with three equivalents of acid, producing one equivalent of H3PO3, or phosphorus acid, in addition to the desired acid chloride. PCl5 reacts with carboxylic acids in a 1:1 ratio, and produces phosphorus(V) oxychloride (POCl3) and hydrogen chloride (HCl) as byproducts.

Carboxylic acids react with Grignard reagents and organolithiums to form ketones. The first equivalent of nucleophile acts as a base and deprotonates the acid. A second equivalent will attack the carbonyl group to create a

Phosphorus(III) chloride (PCl3) and phosphorus(V) chloride (PCl5) will also convert carboxylic acids to acid chlorides, by a similar mechanism. One equivalent of PCl3 can react with three equivalents of acid, producing one equivalent of H3PO3, or phosphorus acid, in addition to the desired acid chloride. PCl5 reacts with carboxylic acids in a 1:1 ratio, and produces phosphorus(V) oxychloride (POCl3) and hydrogen chloride (HCl) as byproducts.

Carboxylic acids react with Grignard reagents and organolithiums to form ketones. The first equivalent of nucleophile acts as a base and deprotonates the acid. A second equivalent will attack the carbonyl group to create a geminal

In chemistry, the descriptor geminal () refers to the relationship between two atoms or functional groups that are attached to the same atom. A geminal diol, for example, is a diol (a molecule that has two alcohol functional groups) attached t ...

alkoxide dianion, which is protonated upon workup to give the hydrate of a ketone. Because most ketone hydrates are unstable relative to their corresponding ketones, the equilibrium between the two is shifted heavily in favor of the ketone. For example, the equilibrium constant for the formation of acetone

Acetone (2-propanone or dimethyl ketone), is an organic compound with the formula . It is the simplest and smallest ketone (). It is a colorless, highly volatile and flammable liquid with a characteristic pungent odour.

Acetone is miscibl ...

hydrate from acetone is only 0.002. The carboxylic group is the most acidic in organic compounds.Wade 2010, p. 838.

See also

*Nucleophilic aliphatic substitution

In chemistry, a nucleophilic substitution is a class of chemical reactions in which an electron-rich chemical species (known as a nucleophile) replaces a functional group within another electron-deficient molecule (known as the electrophile). Th ...

*Nucleophilic aromatic substitution

A nucleophilic aromatic substitution is a substitution reaction in organic chemistry in which the nucleophile displaces a good leaving group, such as a halide, on an aromatic ring. Aromatic rings are usually nucleophilic, but some aromatic compou ...

* Nucleophilic abstraction

References

External links

* Reaction ofacetic anhydride

Acetic anhydride, or ethanoic anhydride, is the chemical compound with the formula (CH3CO)2O. Commonly abbreviated Ac2O, it is the simplest isolable anhydride of a carboxylic acid and is widely used as a reagent in organic synthesis. It is a co ...

with acetone

Acetone (2-propanone or dimethyl ketone), is an organic compound with the formula . It is the simplest and smallest ketone (). It is a colorless, highly volatile and flammable liquid with a characteristic pungent odour.

Acetone is miscibl ...

in Organic Syntheses

''Organic Syntheses'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal that was established in 1921. It publishes detailed and checked procedures for the synthesis of organic compounds. A unique feature of the review process is that all of the data and exp ...

Coll. Vol. 3, p. 16; Vol. 20, p. Article

{{Reaction mechanisms Nucleophilic substitution reactions Reaction mechanisms