entomological warfare on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Entomological warfare (EW) is a type of biological warfare that uses

", ''

Using the flea as weapon

,

Web version

via ''

Warfare gets the creepy-crawlies

, ''

", (Press release), ''

The Role of Insects as a Biological Weapon

, Department of Entomology, ''

Bug Bomb

, ''

Google Books

, Harvard University Press, 2006, pp. 84-90, (). including entomological research.

Japan used entomological warfare on a large scale during World War II in

Japan used entomological warfare on a large scale during World War II in

Six-legged soldiers

, '' The Scientist'', October 24, 2008, accessed December 23, 2008.Novick, Lloyd and Marr, John S. ''Public Health Issues Disaster Preparedness'',

Google Books

, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2001, p. 87, (). An international symposium of historians declared in 2002 that Japanese entomological warfare in China was responsible for the deaths of 440,000.

Agricultural Biological Warfare: An Overview

", ''The Arena'', June 2000, Paper #9, Chemical and Biological Arms Control Institute, via

The United States seriously researched the potential of entomological warfare during the

The United States seriously researched the potential of entomological warfare during the

Wartime Lies?

, ''

Google Books

, Indiana University Press, 1998, pp. 75-77, (), links accessed December 24, 2008.

, ''

Unmasking an Old Lie

", '' U.S. News & World Report'', November 16, 1998, accessed December 24, 2008. During the 1950s the United States conducted a series of field tests using entomological weapons.

During the 1950s the United States conducted a series of field tests using entomological weapons.

Google Books

, ABC-CLIO, 2005, p. 304, (). Big Itch went awry when some of the fleas escaped into the plane and bit all three members of the air crew. In May 1955 over 300,000 uninfected mosquitoes (''

An Evaluation of Entomological Warfare as a Potential Danger to the United States and European NATO Nations

, U.S. Army Test and Evaluation Command, Dugway Proving Ground, March 1981, via '' thesmokinggun.com'', accessed December 25, 2008. At Kadena Air Force Base, an Entomology Branch of the U.S. Army Preventive Medicine Activity, U.S. Army Medical Center was used to grow "medically important" arthropods, including many strains of mosquitoes in a study of disease vector efficiency. The program reportedly supported a research program studying taxonomic and ecological data surveys for the

Commercial products, from insects

, (p. 6). In Resh, V.H. & Carde, R. eds. ''Encyclopedia of Insects'', Academic Press, San Diego, via ''

", Regulatory and Public Service Program, '' Clemson University'', 2001, accessed December 25, 2008. Because

Agricultural Bioterror Threat Requires Vigilance

", (Press release), Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resource, ''

Insects: Tougher than anthrax

, ''

Medfly Madness

, ''

'Maggot bombs' and malaria

, ''

Google Books

, McGraw-Hill Professional, 2006, p. 49, (). The group stated in a letter to then Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley that their goals were twofold. They sought to cause the medfly infestation to grow out of control which, in turn, would render the ongoing

", The Biological and Toxic Weapons Convention Website, accessed January 5, 2009. It would appear, due to the text of the BWC, that insect vectors as an aspect of entomological warfare are covered and outlawed by the Convention.Zanders, Jean Pascal.

Research Policies, BW Development & Disarmament

", Conference: "Ethical Implications of Scientific Research on Bioweapons and Prevention of Bioterrorism",

Google Books

, Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 45-50, ().

"Agricultural research, or a new bioweapon system?"

''Science'', Retrieved 20th May 2019

Google Books

, McClelland & Stewart, 1989, (). * Garrett, Benjamin C.

The Colorado Potato Beetle Goes to War

, ''Chemical Weapons Convention Bulletin'', Issue #33, September 1996, accessed January 3, 2009. * Hay, Alastair. "A Magic Sword or A Big Itch: An Historical Look at the United States Biological Weapon Programme",

Citation

, ''Medicine, Conflict, and Survival'', Vol. 15 July–September 1999, pp. 215–234). * Lockwood, Jeffrey A. "Entomological Warfare: History of the Use of Insects as Weapons of War"

Citation

''Bulletin of the Entomological Society of America'', Summer 1987, v. 33(2), pp. 76–82. * Lockwood, Jeffrey A.

, ''The New York Times'', April 18, 2009, accessed April 24, 2009. *

The Biological and Toxic Weapons Convention

official site, accessed January 5, 2009.

''

insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body ( head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

s to interrupt supply lines by damaging crops, or to directly harm enemy combatants and civilian populations. There have been several programs which have attempted to institute this methodology; however, there has been limited application of entomological warfare against military or civilian targets, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

being the only state known to have verifiably implemented the method against another state, namely the Chinese during World War II. However, EW was used more widely in antiquity, in order to repel sieges or cause economic harm to states. Research into EW was conducted during both World War II and the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

by numerous states such as the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, United States, Germany and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. There have also been suggestions that it could be implemented by non-state actors in a form of bioterrorism. Under the Biological and Toxic Weapons Convention of 1972, use of insects to administer agents or toxins for hostile purposes is deemed to be against international law.

Description

EW is a specific type of biological warfare (BW) that usesinsect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body ( head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

s in a direct attack or as vectors to deliver a biological agent

A biological agent (also called bio-agent, biological threat agent, biological warfare agent, biological weapon, or bioweapon) is a bacterium, virus, protozoan, parasite, fungus, or toxin that can be used purposefully as a weapon in bioterroris ...

, such as plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

or cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

. Essentially, EW exists in three varieties. One type of EW involves infecting insects with a pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

and then dispersing the insects over target areas.An Introduction to Biological Weapons, Their Prohibition, and the Relationship to Biosafety", ''

The Sunshine Project The Sunshine Project was an international NGO dedicated to upholding prohibitions against biological warfare and, particularly, to preventing military abuse of biotechnology. It was directed by Edward Hammond.

With offices in Austin, Texas, and H ...

'', April 2002, accessed December 25, 2008. The insects then act as a vector, infecting any person or animal they might bite. Another type of EW is a direct insect attack against crops; the insect may not be infected with any pathogen but instead represents a threat to agriculture. The final method of entomological warfare is to use uninfected insects, such as bees, to directly attack the enemy.Lockwood, Jeffrey A. '' Six-legged Soldiers: Using Insects as Weapons of War'', Oxford University Press, USA, 2008, pp. 9–26, ().

Early history

Entomological warfare is not a new concept; historians and writers have studied EW in connection to multiple historic events. A 14th-century plague epidemic in Asia Minor that eventually became known as theBlack Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

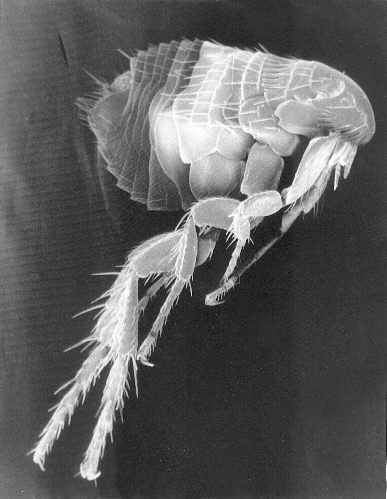

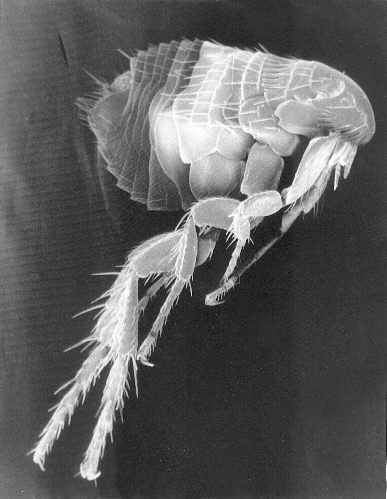

(carried by flea

Flea, the common name for the order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult fleas grow to about long, a ...

s) is one such event that has drawn attention from historians as a possible early incident of entomological warfare. That plague's spread over Europe may have been the result of a biological attack on the Crimean

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

city of Kaffa.Kirby, Reid.Using the flea as weapon

,

Web version

via ''

findarticles.com

''FindArticles'' was a website which provided access to articles previously published in over 3,000 magazines, newspapers, journals, business reports and other sources. The site offered free and paid content through the HighBeam Research database ...

''), '' Army Chemical Review'', July 2005, accessed December 23, 2008.

According to Jeffrey Lockwood

Jeffrey Alan Lockwood (born 1960) is an author, entomologist, and University of Wyoming professor of Natural Sciences and Humanities. He writes both nonfiction science books, as well as meditations. Lockwood is the recipient of both the Pushcart P ...

, author of '' Six-Legged Soldiers'' (a book about EW), the earliest incident of entomological warfare was probably the use of bee

Bees are winged insects closely related to wasps and ants, known for their roles in pollination and, in the case of the best-known bee species, the western honey bee, for producing honey. Bees are a monophyly, monophyletic lineage within the ...

s by early humans.Baumann, Peter.Warfare gets the creepy-crawlies

, ''

Laramie Boomerang

The ''Laramie Boomerang'', formerly the ''Laramie Daily Boomerang'', is a newspaper in Laramie, Wyoming, USA.

History

The newspaper was established in March 1881 by American humorist Edgar Wilson ("Bill") Nye, who named the paper after his mule ...

'', October 18, 2008, accessed December 23, 2008. The bees or their nests were thrown into caves to force the enemy out and into the open. Lockwood theorizes that the Ark of the Covenant

The Ark of the Covenant,; Ge'ez: also known as the Ark of the Testimony or the Ark of God, is an alleged artifact believed to be the most sacred relic of the Israelites, which is described as a wooden chest, covered in pure gold, with an e ...

may have been deadly when opened because it contained deadly fleas.UW Professor Examines Biological Setting of Egyptian Plagues", (Press release), ''

University of Wyoming

The University of Wyoming (UW) is a public land-grant research university in Laramie, Wyoming. It was founded in March 1886, four years before the territory was admitted as the 44th state, and opened in September 1887. The University of Wyoming ...

'', December 12, 2005, accessed December 23, 2008.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

the Confederacy accused the Union of purposely introducing the harlequin bug in the South. These accusations were never proven, and modern research has shown it more likely that the insect arrived by other means. The world did not experience large-scale entomological warfare until World War II; Japanese attacks in China were the only verified instance of BW or EW during the war.Peterson, R.K.D.The Role of Insects as a Biological Weapon

, Department of Entomology, ''

Montana State University

Montana State University (MSU) is a Public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Bozeman, Montana. It is the state's largest university. MSU offers baccalaureate degrees in 60 fields, master's degrees in 6 ...

'', notes based on seminar, 1990, accessed December 25, 2008. During, and following, the war other nations began their own EW programs.

World War II

France

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

is known to have pursued entomological warfare programs during World War II. Like Germany, the nation suggested that the Colorado potato beetle, aimed at the enemy's food sources, would be an asset during the war.Lockwood, Jeffrey A.Bug Bomb

, ''

Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

'', October 21, 2007, accessed December 23, 2008. As early as 1939 biological warfare experts in France suggested that the beetle be used against German crops.

Germany

Germany is known to have pursued entomological warfare programs during World War II. The nation pursued the mass-production, and dispersion, of the Colorado potato beetle (''Lepinotarsa decemlineata''), aimed at the enemy's food sources. The beetle was first found in Germany in 1914, as an invasive species from North America. There are no records that indicate the beetle was ever employed as a weapon by Germany, or any other nation during the war.Heather, Neil W. and Hallman, Guy J. ''Pest Management and Phytosanitary Trade Barriers'' ( oogle Books, CABI, 2008, pp. 17–18, (). Regardless, the Germans had developed plans to drop the beetles on English crops. Germany carried out testing of its Colorado potato beetle weaponization program south ofFrankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

, where they released 54,000 of the beetles. In 1944, an infestation of Colorado potato beetles was reported in Germany. The source of the infestation is unknown, speculation has offered three alternative theories as to the origin of the infestation. One option is Allied action, an entomological attack, another is that it was the result of the German testing, and still another more likely explanation is that it was merely a natural occurrence.

Canada

Among the Allied Powers,Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

led the pioneering effort in vector-borne warfare. After Japan became intent on developing the plague flea as a weapon, Canada and the United States followed suit. Cooperating closely with the United States, Dr. G.B. Reed, chief of Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the five most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

's Queen's University Queen's or Queens University may refer to:

*Queen's University at Kingston, Ontario, Canada

*Queen's University Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK

**Queen's University of Belfast (UK Parliament constituency) (1918–1950)

**Queen's University of Belfast ...

's Defense Research Laboratory, focused his research efforts on mosquito vectors, biting flies, and plague infected fleas during World War II. Much of this research was shared with or conducted in concert with the United States.

Canada's entire bio-weapons program was ahead of the British and the Americans during the war. The Canadians tended to work in areas their allies ignored; entomological warfare was one of these areas. As the U.S. and British programs evolved, the Canadians worked closely with both nations. The Canadian BW work would continue well after the war,Wheelis, Mark, et al. ''Deadly Cultures: Biological Weapons Since 1945'',Google Books

, Harvard University Press, 2006, pp. 84-90, (). including entomological research.

Japan

Japan used entomological warfare on a large scale during World War II in

Japan used entomological warfare on a large scale during World War II in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

. Unit 731, Japan's biological warfare unit, led by Lt. General Shirō Ishii, used plague-infected flea

Flea, the common name for the order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult fleas grow to about long, a ...

s and flies covered with cholera to infect the population in China. Japanese Yagi bombs developed at Pingfan consisted of two compartments, one with houseflies and another with a bacterial slurry that coated the houseflies prior to release. The Japanese military dispersed them from low-flying airplanes; spraying the fleas from them and dropping the Yagi bombs filled with a mixture of insects and disease. Localized and deadly epidemics

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics of infectious d ...

resulted and nearly 500,000 Chinese died of disease.Lockwood, Jeffrey A.Six-legged soldiers

, '' The Scientist'', October 24, 2008, accessed December 23, 2008.Novick, Lloyd and Marr, John S. ''Public Health Issues Disaster Preparedness'',

Google Books

, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2001, p. 87, (). An international symposium of historians declared in 2002 that Japanese entomological warfare in China was responsible for the deaths of 440,000.

United Kingdom

A British scientist,J.B.S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (; 5 November 18921 December 1964), nicknamed "Jack" or "JBS", was a British-Indian scientist who worked in physiology, genetics, evolutionary biology, and mathematics. With innovative use of statistics in biolog ...

, suggested that Britain and Germany were both vulnerable to entomological attack via the Colorado potato beetle. In 1942 the United States shipped 15,000 Colorado potato beetles to Britain for study as a weapon.

Cold War

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union researched, developed and tested an entomological warfare program as a major part of an anti-crop and anti-animal BW program. The Soviets developed techniques for using insects to transmit animal pathogens, such as: foot and mouth disease—which they usedtick

Ticks (order Ixodida) are parasitic arachnids that are part of the mite superorder Parasitiformes. Adult ticks are approximately 3 to 5 mm in length depending on age, sex, species, and "fullness". Ticks are external parasites, living by ...

s to transmit; avian ticks to transmit ''Chlamydophila psittaci

''Chlamydia psittaci'' is a lethal intracellular parasite, intracellular bacterial species that may cause Endemism, endemic Bird, avian chlamydiosis, epizootic outbreaks in mammals, and respiratory psittacosis in humans. Potential hosts include ...

'' to chickens; and claimed to have developed an automated mass insect breeding facility, capable of outputting millions of parasitic insects per day.Ban, Jonathan.Agricultural Biological Warfare: An Overview

", ''The Arena'', June 2000, Paper #9, Chemical and Biological Arms Control Institute, via

Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism

The Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism (MIPT) is a non-profit organization founded in response to the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Supported by Department of Homeland Security and other government grant funds, it conducted research ...

, accessed December 25, 2008.

United States

The United States seriously researched the potential of entomological warfare during the

The United States seriously researched the potential of entomological warfare during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. The United States military

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

developed plans for an entomological warfare facility, designed to produce 100 million yellow fever-infected mosquitoes per month. A U.S. Army report titled "Entomological Warfare Target Analysis" listed vulnerable sites within the Soviet Union that the U.S. could attack using entomological vectors. The military also tested the mosquito biting capacity by dropping uninfected mosquitoes over U.S. cities.

North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

n and Chinese officials leveled accusations that during the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

the United States engaged in biological warfare, including EW, in North Korea. The claim is dated to the period of the war, and has been thoroughly denied by the U.S.Regis, Ed

Edward Regis, Jr (born 1944) — known as Ed Regis — is an American philosopher, educator and author. He specializes in books and articles about science, philosophy and intelligence. His topics have included nanotechnology, transhumanism and b ...

.Wartime Lies?

, ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', June 27, 1999, accessed December 24, 2008. In 1998, Stephen Endicott and Edward Hagerman claimed that the accusations were true in their book, ''The United States and Biological Warfare: Secrets from the Early Cold War and Korea''.Endicott, Stephen, and Hagerman, Edward. ''The United States and Biological Warfare: Secrets from the Early Cold War and Korea'',Google Books

, Indiana University Press, 1998, pp. 75-77, (), links accessed December 24, 2008.

, ''

York University

York University (french: Université York), also known as YorkU or simply YU, is a public university, public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It is Canada's fourth-largest university, and it has approximately 55,700 students, 7,0 ...

'', compiled book review excerpts, accessed December 24, 2008. Other historians have revived the claim in recent decades as well. The same year Endicott and Hagerman's book was published Kathryn Weathersby and Milton Leitenberg of the Cold War International History Project at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington released a cache of Soviet and Chinese documents which revealed the North Korean claim was an elaborate disinformation campaign.Auster, Bruce B.Unmasking an Old Lie

", '' U.S. News & World Report'', November 16, 1998, accessed December 24, 2008.

During the 1950s the United States conducted a series of field tests using entomological weapons.

During the 1950s the United States conducted a series of field tests using entomological weapons. Operation Big Itch Operation Big Itch was a U.S. entomological warfare field test using uninfected fleas to determine their coverage and survivability as a vector for biological agents. Bubonic plague is an infection of the lymphatic system, usually resulting from the ...

, in 1954, was designed to test munitions loaded with uninfected fleas ('' Xenopsylla cheopis'').Croddy, Eric and Wirtz, James J. ''Weapons of Mass Destruction: An Encyclopedia of Worldwide Policy, Technology, and History'',Google Books

, ABC-CLIO, 2005, p. 304, (). Big Itch went awry when some of the fleas escaped into the plane and bit all three members of the air crew. In May 1955 over 300,000 uninfected mosquitoes (''

Aedes aegypti

''Aedes aegypti'', the yellow fever mosquito, is a mosquito that can spread dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika fever, Mayaro and yellow fever viruses, and other disease agents. The mosquito can be recognized by black and white markings on its legs ...

'') were dropped over parts of the U.S. state of Georgia to determine if the air-dropped mosquitoes could survive to take meals from humans. The mosquito tests were known as Operation Big Buzz

Operation Big Buzz was a U.S. military entomological warfare field test conducted in the U.S. state of Georgia in 1955. The tests involved dispersing over 300,000 mosquitoes from aircraft and through ground dispersal methods.

Operation

Operation B ...

. Operation Magic Sword was a 1965 U.S. military operation designed to test the effectiveness of the sea-borne release of insect vectors for biological agents. The U.S. engaged in at least two other EW testing programs, Operation Drop Kick Operation Drop Kick was conducted between April and November 1956 by the US Army Chemical CorpsRose, William H.An Evaluation of Entomological Warfare as a Potential Danger to the United States and European NATO Nations, U.S. Army Test and Evaluation ...

and Operation May Day Operation May Day was a series of entomological warfare (EW) tests conducted by the U.S. military in Savannah, Georgia in 1956.

Operation

Operation May Day involved a series of EW tests from April to November 1956. The tests were designed to reve ...

. A 1981 Army report outlined these tests as well as multiple cost-associated issues that occurred with EW. The report is partially declassified—some information is blacked out, including everything concerning "Drop Kick"—and included "cost per death" calculations. The cost per death, according to the report, for a vector-borne biological agent achieving a 50% mortality rate in an attack on a city was $0.29 in 1976 dollars (approximately $1.01 today). Such an attack was estimated to result in 625,000 deaths.Rose, William H.An Evaluation of Entomological Warfare as a Potential Danger to the United States and European NATO Nations

, U.S. Army Test and Evaluation Command, Dugway Proving Ground, March 1981, via '' thesmokinggun.com'', accessed December 25, 2008. At Kadena Air Force Base, an Entomology Branch of the U.S. Army Preventive Medicine Activity, U.S. Army Medical Center was used to grow "medically important" arthropods, including many strains of mosquitoes in a study of disease vector efficiency. The program reportedly supported a research program studying taxonomic and ecological data surveys for the

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

.

The Smithsonian Institution and The National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Natio ...

and National Research Council National Research Council may refer to:

* National Research Council (Canada), sponsoring research and development

* National Research Council (Italy), scientific and technological research, Rome

* National Research Council (United States), part of ...

administered special research projects in the Pacific. The Far East Section of the Office of the Foreign Secretary (the NAS Foreign Secretary, not the UK office) administered two such projects which focused "on the flora of Okinawa" and "trapping of airborne insects and arthropods for the study of the natural dispersal of insects and arthropods over the ocean." The motivation for civilian research programs of this nature was questioned when it was learned that such international research was in fact funded by and provided to the U.S. Army as part of the U.S. military's biological warfare research.

The United States has also applied entomological warfare research and tactics in non-combat situations. In 1990 the U.S. funded a $6.5 million program designed to research, breed and drop caterpillar

Caterpillars ( ) are the larval stage of members of the order Lepidoptera (the insect order comprising butterflies and moths).

As with most common names, the application of the word is arbitrary, since the larvae of sawflies (suborder Sym ...

s.Irwin, M.E. and G.E. Kampmeier.Commercial products, from insects

, (p. 6). In Resh, V.H. & Carde, R. eds. ''Encyclopedia of Insects'', Academic Press, San Diego, via ''

University of Illinois

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (U of I, Illinois, University of Illinois, or UIUC) is a public land-grant research university in Illinois in the twin cities of Champaign and Urbana. It is the flagship institution of the University ...

'' and Illinois Natural History Survey, accessed December 25, 2008. The caterpillars were to be dropped in Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

on coca fields as part of the American War on Drugs

The war on drugs is a Globalization, global campaign, led by the United States federal government, of prohibition of drugs, drug prohibition, military aid, and military intervention, with the aim of reducing the illegal drug trade in the Unite ...

. As recently as 2002 U.S. entomological anti-drug efforts at Fort Detrick

Fort Detrick () is a United States Army Futures Command installation located in Frederick, Maryland. Historically, Fort Detrick was the center of the U.S. biological weapons program from 1943 to 1969. Since the discontinuation of that program, i ...

were focused on finding an insect vector for a virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

that affects the opium poppy

''Papaver somniferum'', commonly known as the opium poppy or breadseed poppy, is a species of flowering plant in the family Papaveraceae. It is the species of plant from which both opium and poppy seeds are derived and is also a valuable ornamen ...

.

Bioterrorism

Clemson University's Regulatory and Public Service Program listed "diseases vectored by insects" among bioterrorism scenarios considered "most likely".Regulatory and Public Service Programs’ Strategy for the Prevention Of Bioterrorism in Areas Regulated", Regulatory and Public Service Program, '' Clemson University'', 2001, accessed December 25, 2008. Because

invasive species

An invasive species otherwise known as an alien is an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Although most introduced species are neutral or beneficial with respect to other species, invasive species ad ...

are already a problem worldwide one University of Nebraska

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, the ...

entomologist considered it likely that the source of any sudden appearance of a new agricultural pest would be difficult, if not impossible, to determine.Corley, Heather.Agricultural Bioterror Threat Requires Vigilance

", (Press release), Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resource, ''

University of Nebraska

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, the ...

'', November 12, 2001, accessed December 25, 2008. Lockwood considers insects a more effective means of transmitting biological agents for acts of bioterrorism than the actual agents. In his opinion insect vectors are easily gathered and their eggs easily transportable without detection. Isolating and delivering biological agents, on the other hand, is extremely challenging and hazardous.Lockwood, Jeffrey A.Insects: Tougher than anthrax

, ''

The Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

'', October 21, 2007, accessed December 25, 2008.

In one of the few suspected acts of entomological bioterrorism an eco-terror

Eco-terrorism is an act of violence which is committed in support of environmental causes, against people or property.

The United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) defines eco-terrorism as "...the use or threatened use of violence o ...

group known as The Breeders claimed to have released Mediterranean fruit flies (medflies) amidst an ongoing California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

infestation.Bonfante, Jordan.Medfly Madness

, ''

Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'', January 8, 1990, accessed December 25, 2008. Lockwood asserts that there is some evidence the group played a role in the event.Baker, Eric.'Maggot bombs' and malaria

, ''

Casper Star-Tribune

The ''Casper Star-Tribune'' is a newspaper published in Casper, Wyoming, with statewide influence and readership.

It is Wyoming's largest print newspaper, with a daily circulation of 23,760 and a Sunday circulation of 21,041. The ''Star-Tribune'' ...

'', via the ''Laramie Boomerang'', February 27, 2006, accessed December 25, 2008. The pest attacks a variety of crops and the state of California responded with a large-scale pesticide

Pesticides are substances that are meant to control pests. This includes herbicide, insecticide, nematicide, molluscicide, piscicide, avicide, rodenticide, bactericide, insect repellent, animal repellent, microbicide, fungicide, and lampri ...

spraying program. At least one source asserted that there is no doubt that an outside hand played a role in the dense 1989 infestation.Howard, Russell D. et al. ''Homeland Security and Terrorism: Readings and Interpretations'',Google Books

, McGraw-Hill Professional, 2006, p. 49, (). The group stated in a letter to then Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley that their goals were twofold. They sought to cause the medfly infestation to grow out of control which, in turn, would render the ongoing

malathion

Malathion is an organophosphate insecticide which acts as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. In the USSR, it was known as carbophos, in New Zealand and Australia as maldison and in South Africa as mercaptothion.

Pesticide use

Malathion is a pesti ...

spraying program financially infeasible.

Legal status

The Biological and Toxic Weapons Convention (BWC) of 1972 does not specifically mention insect vectors in its text. The language of the treaty, however, does cover vectors. Article I bans "Weapons, equipment or means of delivery designed to use such agents or toxins for hostile purposes or in armed conflict."Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction", The Biological and Toxic Weapons Convention Website, accessed January 5, 2009. It would appear, due to the text of the BWC, that insect vectors as an aspect of entomological warfare are covered and outlawed by the Convention.Zanders, Jean Pascal.

Research Policies, BW Development & Disarmament

", Conference: "Ethical Implications of Scientific Research on Bioweapons and Prevention of Bioterrorism",

European Commission

The European Commission (EC) is the executive of the European Union (EU). It operates as a cabinet government, with 27 members of the Commission (informally known as "Commissioners") headed by a President. It includes an administrative body o ...

, via ''BioWeapons Prevention Project'', February 4, 2004, accessed January 5, 2009. The issue is less clear when warfare with uninfected insects against crops is considered.Sims, Nicholas Roger Alan, (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) is an international institute based in Stockholm. It was founded in 1966 and provides data, analysis and recommendations for armed conflict, military expenditure and arms trade as well a ...

). ''The Evolution of Biological Disarmament'',Google Books

, Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 45-50, ().

Genetically engineered insects

US intelligence officials have suggested that insects could be genetically engineered via technologies such asCRISPR

CRISPR () (an acronym for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) is a family of DNA sequences found in the genomes of prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria and archaea. These sequences are derived from DNA fragments of bacte ...

to create GMO

A genetically modified organism (GMO) is any organism whose genetic material has been altered using genetic engineering techniques. The exact definition of a genetically modified organism and what constitutes genetic engineering varies, with ...

"killer mosquitoes" or plagues that wipe out staple crops. There is research ongoing to genetically modify mosquitoes to curb the spread of diseases, such as Zika, and the West Nile virus

West Nile virus (WNV) is a single-stranded RNA virus that causes West Nile fever. It is a member of the family ''Flaviviridae'', from the genus ''Flavivirus'', which also contains the Zika virus, dengue virus, and yellow fever virus. The virus ...

by using mosquitoes modified using CRISPR to no longer carry the pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

. However this research also shows that it may also be possible to ''implant'' diseases or pathogens via genetic modification. It has been suggested by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology that current US research into genetically modified insects for crop protection via infectious diseases which spread genetic modifications to crops ''en masse'' could lead to the creation of genetically modified insects for use in warfare.R. G. Reeves, S. Voeneky, D. Caetano-Anollés, F. Beck, C. Boëte"Agricultural research, or a new bioweapon system?"

''Science'', Retrieved 20th May 2019

See also

*1989 California medfly attack

In 1989, a sudden invasion of Mediterranean fruit flies (''Ceratitis capitata'', " medflies") appeared in California and began devastating crops. Scientists were puzzled and said that the sudden appearance of the insects "defies logic", and some sp ...

* War against the potato beetle

The war against the potato beetle was a campaign launched in Warsaw Pact countries during the Cold War to eradicate the Colorado potato beetle (''Leptinotarsa decemlineata''). It was also a Eastern Bloc information dissemination, propaganda operat ...

* Agroterrorism

* Entomology

Entomology () is the science, scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such ...

* Military animal

Military animals are trained animals that are used in warfare and other combat related activities. As working animals, different military animals serve different functions. Horses, elephants, camels, and other animals have been used for both tran ...

*

*Genetically modified virus

A genetically modified virus is a virus that has been altered or generated using biotechnology methods, and remains capable of infection. Genetic modification involves the directed insertion, deletion, artificial synthesis or change of nucleo ...

* Insect Allies

References

Further reading

* Bryden, John. ''Deadly Allies: Canada's Secret War, 1937-1947'',Google Books

, McClelland & Stewart, 1989, (). * Garrett, Benjamin C.

The Colorado Potato Beetle Goes to War

, ''Chemical Weapons Convention Bulletin'', Issue #33, September 1996, accessed January 3, 2009. * Hay, Alastair. "A Magic Sword or A Big Itch: An Historical Look at the United States Biological Weapon Programme",

Citation

, ''Medicine, Conflict, and Survival'', Vol. 15 July–September 1999, pp. 215–234). * Lockwood, Jeffrey A. "Entomological Warfare: History of the Use of Insects as Weapons of War"

Citation

''Bulletin of the Entomological Society of America'', Summer 1987, v. 33(2), pp. 76–82. * Lockwood, Jeffrey A.

, ''The New York Times'', April 18, 2009, accessed April 24, 2009. *

External links

The Biological and Toxic Weapons Convention

official site, accessed January 5, 2009.

''

Oregon State University

Oregon State University (OSU) is a public land-grant, research university in Corvallis, Oregon. OSU offers more than 200 undergraduate-degree programs along with a variety of graduate and doctoral degrees. It has the 10th largest engineering co ...

'', Department of Entomology, accessed December 25, 2008.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Entomological Warfare

Military animals

Warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular ...

Insects in culture