Buttermilk Point on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

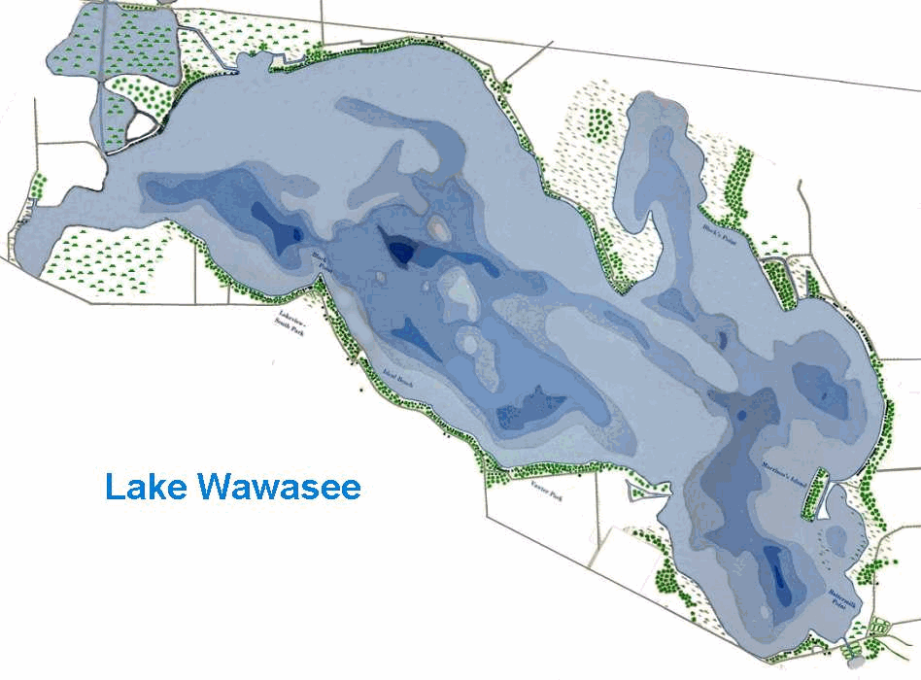

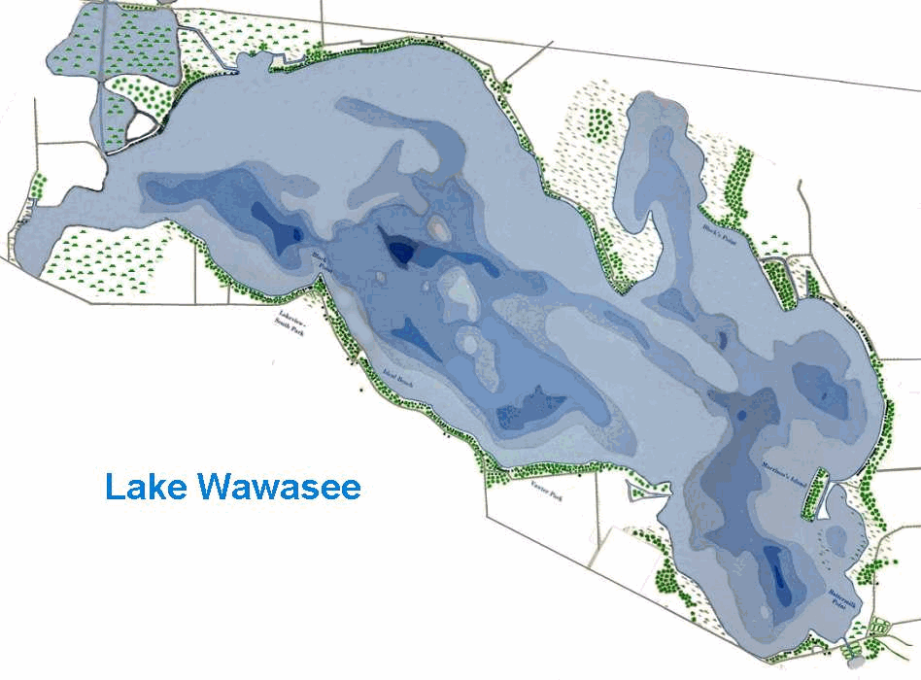

Lake Wawasee is a large, natural,

Lake Wawasee is a large, natural,

Waco (Wawasee Amusement Company) was an entertainment hall constructed about 1910 and originally planned as a floating pavilion but this idea was abandoned and it was built on land and located in the Lakeview-South Park area just west of Black Stump Point. Being low-lying land, sand fill was pumped in from the lake bottom. There were no sleeping quarters for the entertainment and

Waco (Wawasee Amusement Company) was an entertainment hall constructed about 1910 and originally planned as a floating pavilion but this idea was abandoned and it was built on land and located in the Lakeview-South Park area just west of Black Stump Point. Being low-lying land, sand fill was pumped in from the lake bottom. There were no sleeping quarters for the entertainment and

Jan Garber

After Ross Franklin no longer associated with Waco, it deteriorated and became a

NOAA 1943 storm

/ref>

Lake Wawasee is a large, natural,

Lake Wawasee is a large, natural, freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does include ...

lake southeast of Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

*Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

*Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

**North Syracuse, New York

*Syracuse, Indiana

* Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, Miss ...

in Kosciusko County, Indiana

Kosciusko County ( ) is a county in the U.S. state of Indiana. At the 2020 United States Census, its population was 80,240. The county seat (and only incorporated city) is Warsaw.

The county was organized in 1836. It was named for the Polish gen ...

. It is the largest natural lake within Indiana's borders.

Prehistoric

Pre-glacial

Around 1 million years ago just prior to thePleistocene epoch

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in ...

, northern Indiana was covered by the Teays River

The Teays River

(pronounced taze) was a major preglacial river that drained much of the present Ohio River watershed, but took a more northerly downstream course. Traces of the Teays across northern Ohio and Indiana are represented by a network ...

system which flowed northwest out of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

, and Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

entering Indiana at Adams County and flowed about 45 miles (72 km) south of what is now Lake Wawassee.

Post-glacial

After the lastglaciation

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

period, the land was left with kettle hole

A kettle (also known as a kettle lake, kettle hole, or pothole) is a depression/hole in an outwash plain formed by retreating glaciers or draining floodwaters. The kettles are formed as a result of blocks of dead ice left behind by retreating gla ...

s and hilly moraine

A moraine is any accumulation of unconsolidated debris (regolith and rock), sometimes referred to as glacial till, that occurs in both currently and formerly glaciated regions, and that has been previously carried along by a glacier or ice shee ...

s. The land supported large vast ''Picea

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal (taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the subfami ...

'' evergreen forests, and balsam poplar

''Populus balsamifera'', commonly called balsam poplar, bam, bamtree, eastern balsam-poplar, hackmatack, tacamahac poplar, tacamahaca, is a tree species in the balsam poplar species group in the poplar genus, ''Populus.'' The genus name ''Populus ...

, which gave way to hardwoods of oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' (; Latin "oak tree") of the beech family, Fagaceae. There are approximately 500 extant species of oaks. The common name "oak" also appears in the names of species in related genera, notably ''L ...

, poplar and hickory

Hickory is a common name for trees composing the genus ''Carya'', which includes around 18 species. Five or six species are native to China, Indochina, and India (Assam), as many as twelve are native to the United States, four are found in Mexi ...

. Animal life consisted of saber-toothed cat

Machairodontinae is an extinct subfamily of carnivoran mammals of the family Felidae (true cats). They were found in Asia, Africa, North America, South America, and Europe from the Miocene to the Pleistocene, living from about 16 million until ...

, American mastodon

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

, short-faced bear

The Tremarctinae or short-faced bears is a subfamily of Ursidae that contains one living representative, the spectacled bear (''Tremarctos ornatus'') of South America, and several extinct species from four genera: the Florida spectacled bear ('' ...

, dire wolf

The dire wolf (''Aenocyon dirus'' ) is an extinct canine. It is one of the most famous prehistoric carnivores in North America, along with its extinct competitor ''Smilodon''. The dire wolf lived in the Americas and eastern Asia during the Lat ...

, ground sloth

Ground sloths are a diverse group of extinct sloths in the mammalian superorder Xenarthra. The term is used to refer to all extinct sloths because of the large size of the earliest forms discovered, compared to existing tree sloths. The Caribbe ...

, giant beaver, peccary

A peccary (also javelina or skunk pig) is a medium-sized, pig-like hoofed mammal of the family Tayassuidae (New World pigs). They are found throughout Central and South America, Trinidad in the Caribbean, and in the southwestern area of North A ...

, stag-moose

''Cervalces scotti'', the elk moose or stag-moose, is an extinct species of large deer that lived in North America during the Late Pleistocene epoch. It had palmate antlers that were more complex than those of a moose and a muzzle more closely re ...

and ancient bison

''Bison antiquus'', the antique bison or ancient bison, is an extinct species of bison that lived in Late Pleistocene North America until around 10,000 years ago. It was one of the most common large herbivores on the North American continent dur ...

. Lakes would have sturgeon

Sturgeon is the common name for the 27 species of fish belonging to the family Acipenseridae. The earliest sturgeon fossils date to the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretace ...

, whitefish, pike

Pike, Pikes or The Pike may refer to:

Fish

* Blue pike or blue walleye, an extinct color morph of the yellow walleye ''Sander vitreus''

* Ctenoluciidae, the "pike characins", some species of which are commonly known as pikes

* ''Esox'', genus of ...

, pickerel, muskellunge

The muskellunge ''(Esox masquinongy)'', often shortened to muskie, musky or lunge is a species of large freshwater predatory fish native to North America. It is the largest member of the pike family, Esocidae.

Origin of name

The name "muskellun ...

as well as smaller fish such as bluegill

The bluegill (''Lepomis macrochirus''), sometimes referred to as "bream", "brim", "sunny", or "copper nose" as is common in Texas, is a species of North American freshwater fish, native to and commonly found in streams, rivers, lakes, ponds and ...

, redear sunfish

The redear sunfish (''Lepomis microlophus''), also known as the shellcracker, Georgia bream, cherry gill, chinquapin, improved bream, rouge ear sunfish and sun perch) is a freshwater fish in the family Centrarchidae and is native to the southeast ...

, black bass

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have of ...

, yellow perch

The yellow perch (''Perca flavescens''), commonly referred to as perch, striped perch, American perch, American river perch or preacher is a freshwater perciform fish native to much of North America. The yellow perch was described in 1814 by Samu ...

, and catfish

Catfish (or catfishes; order Siluriformes or Nematognathi) are a diverse group of ray-finned fish. Named for their prominent barbels, which resemble a cat's whiskers, catfish range in size and behavior from the three largest species alive, ...

.

Beach formations and peat

Peat (), also known as turf (), is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, moors, or muskegs. The peatland ecosystem covers and is the most efficien ...

beds indicate Wawasee was 7 to 8 feet (2.1 - 2.4 m) deeper than present. Continuing running water through the outlet to the north lowered the lake level 6 to . A dam built in 1834 consequently raised the level back to where it is today.

Recent history

The 1800s

Prior to Europeans coming to Turkey Lake, it was the tribal lands ofMiami Indian

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a coastal metropolis and the county seat of Miami-Dade County in South Florida, United States. With a population of 442,241 at the ...

chiefs Wawasee Wawasee or Wawaausee often contracted into Wawbee and known as ("Full Moon") was a Miami chief who lived in what is now Kosciusko County, Indiana, in the United States. He was brother to Miami chief Papakeecha.

Wawasee was a signatory to the Treaty ...

and Papakeecha Papakeecha or ''(Pa-hed-ke-teh-a)'' meaning "Flat Belly" was the most influential Miami chief in the region around Lake Wawasee, in what is now Kosciusko County, Indiana, United States leading his people from 1820 until 1837. Lake Papakeechie was na ...

. Wawasee was a signatory to the Treaty of Mississinewas

The Treaty of Mississinewas or the Treaty of Mississinewa also called Treaty of the Wabash is an 1826 treaty between the United States and the Miami and Potawatomi Tribes regarding purchase of Indian lands in Indiana and Michigan. The signing was ...

and in 1828 was allotted a small village approximately two and one-half miles southeast of Milford Milford may refer to:

Place names Canada

* Milford (Annapolis), Nova Scotia

* Milford (Halifax), Nova Scotia

* Milford, Ontario

England

* Milford, Derbyshire

* Milford, Devon, a place in Devon

* Milford on Sea, Hampshire

* Milford, Shro ...

and northeast of Waubee Lake

Waubee Lake (also incorrectly Wabee) is a small freshwater lake situated 2 miles (3 km) southeast of Milford, Kosciusko County, Indiana, United States.

Waubee is typical in structure of natural lakes of the glaciated portions of the upper Mid ...

where the town of Syracuse is located. It also included the eastern shores of Turkey Lake ''(Lake Wawasee)'' effectively bisecting the lake in half with the southern half going to his brother.

Early settlers were homesteaders

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than of public land, or nearly 10 percent of th ...

who earned their livelihoods by hunting, fishing, and trapping

Animal trapping, or simply trapping or gin, is the use of a device to remotely catch an animal. Animals may be trapped for a variety of purposes, including food, the fur trade, hunting, pest control, and wildlife management.

History

Neolithic ...

; with a little farming.

White men began coming into the area in the early 1830s and called the lake "Turkey Lake". In 1834 the U.S. government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

deeded the land to the Wabash and Erie Canal

The Wabash and Erie Canal was a shipping canal that linked the Great Lakes to the Ohio River via an artificial waterway. The canal provided traders with access from the Great Lakes all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. Over 460 miles long, it was th ...

; who, in 1875, sold it to Charles R. Ogden. Ownership was passed on to "Uncle" Billy Moore in 1877.

Wawasee geographical places

Cedar Point

Cedar Point is on Wawasee's eastern shore and is aglacial

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

kame

A kame, or ''knob'', is a glacial landform, an irregularly shaped hill or mound composed of sand, gravel and till that accumulates in a depression on a retreating glacier, and is then deposited on the land surface with further melting of the g ...

formed by a subglacial stream Subglacial streams are conduits of glacial meltwater that flow at the base of glaciers and ice caps.

Hooke, Roger LeB. ...

. This ground was inhabited by the Archaic period in the Americas, Glacial Kame Culture that resided here from 8000 BC to 1000 BC. Indications of trade with tribes in the southern United States is evidenced by shells found from the Hooke, Roger LeB. ...

Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

cut and sized to look like the sole of a shoe and circular disks 3 inches (7.6 cm) to 5 inches (12 cm) worn around the neck. Human bones were found protruding from holes in the rock face in the 1880s and often later development unearthed artifacts and skeltel material. In the 1870s or 1880s Cedar Point was inhabited by a single recluse. From the 1940s through 1950s ancient fireplace

A fireplace or hearth is a structure made of brick, stone or metal designed to contain a fire. Fireplaces are used for the relaxing ambiance they create and for heating a room. Modern fireplaces vary in heat efficiency, depending on the design.

...

s made of groupings of burned and cracked stones were found on the top of Cedar Point.

Cedar Point was the best authenticated site of Paleoindians' existence along Wawasee's shore. During the early 20th century the ground was leveled off to use for fill disturbing the natural look of Cedar Point. Today it is home to many summer homes and year-round residents.

Conkling Hill

Conkling Hill was named after a William Conking, a settler and possible sailor during theWar of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

who came to the area in the 1830s with his wife. In 1844 a visitor by the name of P.M. Henkle visited for a day or two of fishing recounted a small cabin with one bed. Conkling Hill was acquired by a church group in 1894 and became Oakwood Park. Today it is a religious retreat called Oakwood Foundation.''(Lilly, Eli)''

Morrison's Island

Morrison's Island was originally Eagle Island when the first white settlers arrived because of thebald eagle

The bald eagle (''Haliaeetus leucocephalus'') is a bird of prey found in North America. A sea eagle, it has two known subspecies and forms a species pair with the white-tailed eagle (''Haliaeetus albicilla''), which occupies the same niche as ...

s nesting there. Eagle Island was also heavily forested with a variety of trees. Morrison's Island is located on Wawasee's south-southeast end overlooking Buttermilk Bay to the south and Johnson's Bay to the north. It was named after William T. Morrison, a Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

soldier who served with an Ohio regiment of the Union army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

. Morrison moved to the area and applied for a position at the old frame schoolhouse once located at Washington Street and Harrison Street.

Morrison built a cabin on Eagle Island where he and his family lived until the 1890s. The house was eventually destroyed by fire. An unsubstantiated story says he took the insurance money and purchased a new shotgun

A shotgun (also known as a scattergun, or historically as a fowling piece) is a long gun, long-barreled firearm designed to shoot a straight-walled cartridge (firearms), cartridge known as a shotshell, which usually discharges numerous small p ...

and melodeon

Melodeon may refer to:

* Melodeon (accordion), a type of button accordion

*Melodeon (organ), a type of 19th-century reed organ

*Melodeon (Boston, Massachusetts), a concert hall in 19th-century Boston

* Melodeon Records, a U.S. record label in the ...

and moved into their barn

A barn is an agricultural building usually on farms and used for various purposes. In North America, a barn refers to structures that house livestock, including cattle and horses, as well as equipment and fodder, and often grain.Allen G. ...

. In the 20th century Morrison sold his island property for a good sum and moved to Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

and in a short time was back in Indiana living very well in Ligonier on his increasing pension and proceeds

from his sale. Elwood George would successfully develop the island.

Kale Island

In 1862 or 1863 Kale Island was settled by two brothers by the name of Thomas and Kale Oram. They made their livelihoods catching fish by net for sale in Goshen and cleared some of land. Trees were floated through the main channel to a saw mill on Turkey Creek or one just south of Vawter Park. The poplar trees going to homes in Syracuse and oak made intobarrel

A barrel or cask is a hollow cylindrical container with a bulging center, longer than it is wide. They are traditionally made of wooden staves and bound by wooden or metal hoops. The word vat is often used for large containers for liquids, ...

staves and firewood. The Oram brothers planted the area with Concord

Concord may refer to:

Meaning "agreement"

* Pact or treaty, frequently between nations (indicating a condition of harmony)

* Harmony, in music

* Agreement (linguistics), a change in the form of a word depending on grammatical features of other ...

and Delaware grape

The Delaware grape is a cultivar derived from the grape species ''Vitis labrusca'' or 'Fox grape' which is used for the table and wine production.

The skin of the Delaware grape when ripened has a pale red, almost pinkish colour, a tender skin, ...

s. During the Civil War, Thomas Oram joined the Union army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

and later moved to Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

. Kale later married a woman named "Mam" who lived with her son Bill in a lowly cabin on Syracuse Lake

Syracuse Lake is a natural lake bordering Syracuse in Kosciusko County, Indiana, United States.

Location

Syracuse Lake is bordered on the west by N. Front Street, Pickwick Road and the B&O Railroad on the south. On the east it is bordered by E. ...

. They lived on Kale Island until 1874 when the land was purchased by Mart Hillabold during the building of the B&O Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

. Kale, Mam and her son moved to her cabin on Syracuse Lake.

In 1873 or 1874, John Wysong and March McCory built Island House on Kale Island, Lake Wawasee's first summer hotel. Badly built, it declined in popularity becoming a poker

Poker is a family of comparing card games in which players wager over which hand is best according to that specific game's rules. It is played worldwide, however in some places the rules may vary. While the earliest known form of the game w ...

and boozing hang-out and eventually burned down. Kale Island was finally acquired by George W. Miles who had it developed into an upscale area for homes.

Dog Creek Dam

Dog Creek Dam and the "fish trap" were located just off the north side of E. Pickwick Drive on Kale Island. A continuation of this dam extended south toward the higher ground of Oakwood Park. The north and west sides of this dam formed the "fish trap" which flooded in the springtime. As waters receded, local settlers would then be able to net andpitchfork

A pitchfork (also a hay fork) is an agricultural tool with a long handle and two to five tines used to lift and pitch or throw loose material, such as hay, straw, manure, or leaves.

The term is also applied colloquially, but inaccurately, to th ...

fish.

The outlet between Lake Wawasee and Syracuse Lake, which flowed westward between the south and north embankment

Embankment may refer to:

Geology and geography

* A levee, an artificial bank raised above the immediately surrounding land to redirect or prevent flooding by a river, lake or sea

* Embankment (earthworks), a raised bank to carry a road, railwa ...

s of Dog Creek Dam. It was an ideal site for a grist mill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and Wheat middlings, middlings. The term can refer to either the Mill (grinding), grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist i ...

and was made by creating a millrace

A mill race, millrace or millrun, mill lade (Scotland) or mill leat (Southwest England) is the current of water that turns a water wheel, or the channel (sluice) conducting water to or from a water wheel. Compared with the broad waters of a mil ...

at that point. The first mill was built in 1834 by Sam Crosson and Henry Ward. It was destroyed somewhat quickly by either being washed away in spring flood

A flood is an overflow of water ( or rarely other fluids) that submerges land that is usually dry. In the sense of "flowing water", the word may also be applied to the inflow of the tide. Floods are an area of study of the discipline hydrol ...

ing or by sinking into a soft bog which were numerous in Kosciusko County. The two mill stone

Millstones or mill stones are stones used in gristmills, for grinding wheat or other grains. They are sometimes referred to as grindstones or grinding stones.

Millstones come in pairs: a convex stationary base known as the ''bedstone'' and ...

s can be seen on the north side of Kale Island and to the east of the main channel through one of the many minor channels.

Wawasee establishments

Cedar Beach Club

The Cedar Beach Club was established in 1880 and was the first hotel on this site. The property was purchased by the North Lake and River Association. Judge John V. Pettit ofWabash, Indiana

Wabash is a city in Noble Township, Wabash County, in the U.S. state of Indiana. The population was 10,666 at the 2010 census. The city is the county seat of Wabash County.

Wabash is notable as claiming to be the first electrically lighted cit ...

became president of the association with individuals from northern Indiana towns of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, Goshen, Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

, Wabash, and Huntington joining and all of which were followers of Izaac Walton which would later produce the Izaak Walton League

The Izaak Walton League is an American environmental organization founded in 1922 that promotes natural resource protection and outdoor recreation. The organization was founded in Chicago, Illinois, by a group of sportsmen who wished to protect fi ...

an early environmental group

The environmental movement (sometimes referred to as the ecology movement), also including conservation and green politics, is a diverse philosophical, social, and political movement for addressing environmental issues. Environmentalists advoc ...

. A simple oblong, two-story, gabled roof

A gable roof is a roof consisting of two sections whose upper horizontal edges meet to form its ridge. The most common roof shape in cold or temperate climates, it is constructed of rafters, roof trusses or purlins. The pitch of a gable roof ca ...

club house was constructed with 50 bedrooms and a 125-seat dining room. The North Lake and River Association financially collapsed in 1882 with the property being sold by the sheriff to the Cedar Beach Association. In 1887 the property was transferred to the Cedar Beach Club for $7000. James B. Suitt of Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

was the president of the club which included James T. Layman, an Indianapolis wholesaler who had served on the Indianapolis City Common Council and Board of Aldermen 1877–1884. Addison H. Nordyke

Addison H. Nordyke was an industrialist and manufacturer from Richmond, Indiana. He co-founded E. & A. H. Nordyke mills, later known as Nordyke Marmon & Company.

Biography

In 1858 Addison H. Nordyke and his father, Ellison Nordyke, formed a pa ...

, flour mill manufacturer. William H. Holliday, F.T. Holliday, J.A. Lemcke, Robert W. Cathcart, John H. Spann, Thomas H. Spann. In 1891 the club burned. It had the first seawall on Wawasee made of logs.

The Jones Hotel

The Jones Hotel, established in September 1881 on the north shore of the lake just east of Willow Grove, was the first major establishment for entertainment on Turkey Lake. It was built by Abram M. Jones, a native ofMansfield, Ohio

Mansfield is a city in and the county seat of Richland County, Ohio, United States. Located midway between Columbus and Cleveland via Interstate 71, it is part of Northeast Ohio region in the western foothills of the Allegheny Plateau. The city ...

, who served with the 2nd Ohio Cavalry during the Civil War. In 1875 Jones, his wife Mary Duff Jones, and 2 sons moved to Syracuse. Jones was a mechanical engineer

Mechanical may refer to:

Machine

* Machine (mechanical), a system of mechanisms that shape the actuator input to achieve a specific application of output forces and movement

* Mechanical calculator, a device used to perform the basic operations of ...

for the B&O Railroad while in Mansfield and continued working for the railroad in Syracuse as operator of the pumping station. Jones also operated the Syracuse grain elevator

A grain elevator is a facility designed to stockpile or store grain. In the grain trade, the term "grain elevator" also describes a tower containing a bucket elevator or a pneumatic conveyor, which scoops up grain from a lower level and deposits ...

.

The Jones Hotel was a successful endeavor from its inception serving great meals to its patrons and visitors. The rooms were said to be comfortable. The hotel had a barn behind it where many of Wawasee's early boats and yachts were built. The Jones Hotel was sold in 1920 to Mr. M. E. Crow of Elkart.

Sargent's Hotel

The Sargent's Hotel was built in the early 20th century and owned by Mr. J. (Jess) M. Sargent. It was located on the northeast shore of the lake, bordering the north side of Spink's Wawasee Hotel and south of the Lilly homes in a grove of trees. J. M. Sargent came to Wawasee in 1899 and assisted on refurbishing the sailboat, ''Mary Louise'', for Bob Fishback. Eventually Sargent opened a boat repair and rental which expanded with success. Sargent married a Laura Ballard fromTerre Haute

Terre Haute ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Vigo County, Indiana, United States, about 5 miles east of the state's western border with Illinois. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 60,785 and its metropolitan area had a ...

and soon the Sargents were renting rooms to visitors at the lake. The Sargents then began purchasing land extending to the B&O station nearby. The hotel, built soon after, hosted dinner parties for large groups. Sargent's Hotel was razed to the ground in 1957.

Buttermilk Point

Buttermilk Point was aresort

A resort (North American English) is a self-contained commercial establishment that tries to provide most of a vacationer's wants, such as food, drink, swimming, lodging, sports, entertainment, and shopping, on the premises. The term ''resort ...

hotel located at the extreme south end of the lake and south shore of Buttermilk Bay. It was owned by Lewis Jarrett, a Civil War veteran and member of an early Wawasee family. In 1893 Lewis died and his wife, Elizabeth, became the owner. At the source of a spring, a log milkhouse was built early on which serviced the passengers in passing steamboats with buttermilk, sweet cream, and butter. Later this site would be home to the Johnson Hotel operated by the Johnson family and later sold to the Hilburt family. The Johnson Hotel, the

last of the great old hotels was sold at auction in 1971.

The Crow's Nest

The Crows's Nest is on Wawasee's east-southeast shore and was built by Nathaniel N. Crow who was a pioneer farmer. Born October 13, 1823 in Champaign County, Ohio, United States, Crow left home around 1839 and traveled toMadison County, Ohio

Madison County is a county located in the central portion of the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 43,824. Its county seat is London. The county is named for James Madison, President of the United States and was es ...

and worked as a farm hand until 1845 when he came to Kosciusko County. To purchase some land in Kosciusko County Nathaniel gave $20 and sold his horse for the he wanted. This property sat unused for years and was sold by Crow for a profit which he used to purchase a farm in Section 24 of Turkey Creek Township.

The first home was built further south near what became known as Natti Crow Beach

Lake Wawasee, formerly Turkey Lake, is a natural lake southeast of Syracuse in Kosciusko County, Indiana, United States. It is the largest natural lake wholly contained within Indiana. It is located just east of Indiana State Road 13.

History

La ...

in later years.

Crow married Eliza Airgood on October 14, 1852. Eliza was born in Germany on September 13, 1832. Her parents were Frederick and Maria Airgood. Nathaniel and Eliza started their married life on the farm. Through careful farming practices, the farm swelled to of tillable land. The Crow's Nest had a blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

's shop operated by a spring running a hydraulic ram

A hydraulic ram, or hydram, is a cyclic water pump powered by hydropower. It takes in water at one "hydraulic head" (pressure) and flow rate, and outputs water at a higher hydraulic head and lower flow rate. The device uses the water hammer ef ...

. The ruins of the spring and ram were remaining through until the 1960s.

In the 1950s the farm became the Crow's Nest and is located at E1100N (NE Wawasee Drive) and N. Lung Drive. The Crow house and huge barn became the Crow's Nest Yacht Club in 1959. The barn was made into a boat storage structure and is capable of housing several boats on 2-3 levels. Natti Crow Beach is one of Wawasee's true sand beach

A beach is a landform alongside a body of water which consists of loose particles. The particles composing a beach are typically made from rock, such as sand, gravel, shingle, pebbles, etc., or biological sources, such as mollusc shel ...

es extending as much as from homes to water's edge and running approximately north to south. The homes in the vicinity are included in the Natti Crow Beach Association, one of the 32 neighborhood associations which comprises Wawasee Property Owners Association. The wetland

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free (anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in the soils. The ...

s near the Crow's Nest property are known as the WACF Nathanial Crow Wetlands according to the Wawasee Area Conservation Foundation.

Vawter Park

Vawter Park Village

Vawter Park is an unincorporated area of shoreline and nearby neighborhoods located on the south shore of Lake Wawasee, Indiana, United States.

History

Vawter Park is located near N. Southshore Drive and E. Vawter Park Road. It was plotted in 1887 ...

was plotted in 1887 and the Vawter Park Hotel was built around 1888 followed by a row of cottages extending to the southeast of the hotel. The hotel is said to have been built and furnished with Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

gentility. Those settling in this area were Ovid Butler

Ovid Butler (February 7, 1801 – July 12, 1881) was an American attorney, newspaper publisher, abolitionist, and university founder from the state of Indiana. Butler University in Indianapolis, Indiana, is named after him.

Personal life

Butler ...

of Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

and others. In 1918 or 1919 Vawter Park Hotel burned to the ground. Around 1920 a new hotel was built on the site only to burn down between 1920 and 1925. The South Shore Inn would take its place in subsequent years. Indiana University

Indiana University (IU) is a system of public universities in the U.S. state of Indiana.

Campuses

Indiana University has two core campuses, five regional campuses, and two regional centers under the administration of IUPUI.

*Indiana Universit ...

operated a laboratory here for some time.

South Shore Inn

The South Shore Inn was a hotel built on the site of the old Vawter Park Hotel. During the 1950s and early 1960s, the hotel attracted visitors and patrons with a waterski jump

Ski jumping is a winter sport in which competitors aim to achieve the farthest jump after sliding down on their skis from a specially designed curved ramp. Along with jump length, competitor's aerial style and other factors also affect the final ...

ing show. The South Shore Inn caught fire in the early morning hours of October 29, 1964. The location was just north of N. Southshore Drive and E. Vawter Park Road.

Wawasee Inn

The Wawasee Inn was built in 1892 byColonel Eli Lilly

Eli Lilly (July 8, 1838 – June 6, 1898) was an American soldier, pharmacist, chemist, and businessman who founded the Eli Lilly and Company pharmaceutical corporation. Lilly enlisted in the Union Army during the American Civil War and ...

and some associates on the site of the Cedar Beach Club. In 1899 Lilly died and the building was sold to Clinton C. Wiggins and his wife Emma followed by the Ballou brothers of Chicago in 1914. In the autumn of 1918 it was destroyed by fire.

Wawasee Inn (2)

The second Wawasee Inn was not on the north shore as was its predecessor as that site was occupied by the Spinks Wawasee Hotel. The (second) Wawasee Inn was formerly the Tavern Hotel, a 2-story structure erected in 1926 with 26 rooms on the south shore of Lake Wawasee. On April 18, 1955 the inn was gutted by fire. Damage was estimated at $75,000.Spink Wawasee Hotel

The Spink Wawasee Hotel was built by the Spink family ofIndianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

in 1925 and was built on the site of the Wawasee Inn Cedar Beach Club. Following the deaths in the Spinks family, the hotel was sold to the Crosier Order of the Roman Catholic Church and after extensive remodeling it opened its doors on August 15, 1948 as Our Lady of the Lake Seminary with Father Leo Kapphahn, OSC, as

prior

Prior (or prioress) is an ecclesiastical title for a superior in some religious orders. The word is derived from the Latin for "earlier" or "first". Its earlier generic usage referred to any monastic superior. In abbeys, a prior would be l ...

and 118 students. In June 1950 work on a gym

A gymnasium, also known as a gym, is an indoor location for athletics. The word is derived from the ancient Greek term " gymnasium". They are commonly found in athletic and fitness centres, and as activity and learning spaces in educational ins ...

nasium was begun. From 1952–1953 a library was completed where the lakeside facing porch in the center of the building was located. In the winter of 1954 an auditorium

An auditorium is a room built to enable an audience to hear and watch performances. For movie theatres, the number of auditoria (or auditoriums) is expressed as the number of screens. Auditoria can be found in entertainment venues, community ...

was constructed. In 1965 the physical plant was purchased and the name of the seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy, ...

changed to Wawasee Preparatory and became a coeducational

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to t ...

school during the 1970s with Father David Suelzer, OSC, as religious superior and Father Thomas Scheets as principal of Wawasee Prep. Later the seminary was known as Wawasee Prep until it closed its doors the summer of 1975. Today, the former hotel/seminary/prep school is a luxury condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership structure whereby a building is divided into several units that are each separately owned, surrounded by common areas that are jointly owned. The term can be applied to the building or complex ...

.

Waco

Waco (Wawasee Amusement Company) was an entertainment hall constructed about 1910 and originally planned as a floating pavilion but this idea was abandoned and it was built on land and located in the Lakeview-South Park area just west of Black Stump Point. Being low-lying land, sand fill was pumped in from the lake bottom. There were no sleeping quarters for the entertainment and

Waco (Wawasee Amusement Company) was an entertainment hall constructed about 1910 and originally planned as a floating pavilion but this idea was abandoned and it was built on land and located in the Lakeview-South Park area just west of Black Stump Point. Being low-lying land, sand fill was pumped in from the lake bottom. There were no sleeping quarters for the entertainment and orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families.

There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* bowed string instruments, such as the violin, viola, c ...

s, and help residing in the area used tents during the summer. In 1923 Waco was enlarged and the current road, South Park, was moved further south. Managed by Ross Franklin, Waco was nationally known and pulled in talent such as Hoagy Carmichael

Hoagland Howard Carmichael (November 22, 1899 – December 27, 1981) was an American musician, composer, songwriter, actor and lawyer. Carmichael was one of the most successful Tin Pan Alley songwriters of the 1930s, and was among the first ...

, Glenn Miller

Alton Glen Miller (March 1, 1904 – December 15, 1944) was an American big band founder, owner, conductor, composer, arranger, trombone player and recording artist before and during World War II, when he was an officer in the United States Arm ...

, Guy Lombardo

Gaetano Alberto "Guy" Lombardo (June 19, 1902 – November 5, 1977) was an Italian-Canadian-American bandleader, violinist, and hydroplane racer.

Lombardo formed the Royal Canadians in 1924 with his brothers Carmen, Lebert and Victor, and othe ...

, Tony Bennett

Anthony Dominick Benedetto (born August 3, 1926), known professionally as Tony Bennett, is an American retired singer of traditional pop standards, big band, show tunes, and jazz. Bennett is also a painter, having created works under his birth ...

, Ted Weems

Wilfred Theodore Wemyes, known professionally as Ted Weems (September 26, 1901 – May 6, 1963), was an American bandleader and musician. Weems's work in music was recognized with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Biography

Born in Pitcair ...

, Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous jazz orchestra from 1923 through the rest of his life. Born and raised in Washington, D.C., Ellington was based ...

, Spike Jones

Lindley Armstrong "Spike" Jones (December 14, 1911 – May 1, 1965) was an American musician and bandleader specializing in spoof arrangements of popular songs and classical music. Ballads receiving the Jones treatment were punctuated with gun ...

, Wayne King

Harold Wayne King (February 16, 1901 – July 16, 1985) was an American musician, songwriter, and bandleader with a long association with both NBC and CBS. He was referred to as "the Waltz King" because much of his most popular music involved wa ...

anJan Garber

After Ross Franklin no longer associated with Waco, it deteriorated and became a

roller skating

Roller skating is the act of traveling on surfaces with roller skates. It is a recreational activity, a sport, and a form of transportation. Roller rinks and skate parks are built for roller skating, though it also takes place on streets, sid ...

rink

Rink may refer to:

* Ice rink, a surface of ice used for ice skating

** Figure skating rink, an ice rink designed for figure skating

** Ice hockey rink, an ice rink designed for ice hockey

** Speed skating rink, an ice rink designed for speed skat ...

and in the 1960s became a lakeside restaurant with dock

A dock (from Dutch language, Dutch ''dok'') is the area of water between or next to one or a group of human-made structures that are involved in the handling of boats or ships (usually on or near a shore) or such structures themselves. The ex ...

and had occasional entertainment. Waco was torn down in the 1970s.

Wawassee Yacht Club

TheWawasee Yacht Club

The Wawasee Yacht Club was formed in 1935 and is located at 6338 E Trusdell Ave. on the northeast shore of Lake Wawasee, Indiana. It currently has 75 families and 35 social members sailing 28-foot E-Scow, 19-foot Lightning, and 13-foot Sunfish c ...

was established in 1935 after four Snipe

A snipe is any of about 26 wading bird species in three genera in the family Scolopacidae. They are characterized by a very long, slender bill, eyes placed high on the head, and cryptic/camouflaging plumage. The ''Gallinago'' snipes have a near ...

sailboat enthusiasts visited Wawasee to see if it was a good sailing lake. They used the front porch of Bishop's Boat Livery

A boat livery is a boathouse or dock on a lake or other body of water, where boats are let out for hire (rental), usually on an hourly, daily or weekly basis. Boats may be powered or sail craft or human powered like rowboats, paddleboats (p ...

and Marine Supply near the Eli Lilly

Eli Lilly (July 8, 1838 – June 6, 1898) was an American soldier, pharmacist, chemist, and businessman who founded the Eli Lilly and Company pharmaceutical corporation. Lilly enlisted in the Union Army during the American Civil War and r ...

estate as their first meeting place and dock their boats. Currently the club sails E-Scow

The E Scow is an American sailing dinghy that was designed by Arnold Meyer Sr as a one-design racer and first built in 1924.Sherwood, Richard M.: ''A Field Guide to Sailboats of North America, Second Edition'', pages 128-129. Houghton Mifflin ...

s, Lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electric charge, electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the land, ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous ...

s, and Sunfish class boats in three regatta

Boat racing is a sport in which boats, or other types of watercraft, race on water. Boat racing powered by oars is recorded as having occurred in ancient Egypt, and it is likely that people have engaged in races involving boats and other wate ...

s held from June through early October.

Angler's Cove

Angler's Cove was a surf and turf restaurant andbar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

located on N. Ogden Park Road, Ogden Island. The restaurant was popular with boaters in the late 1950s through 1970s and accessible from the channel on the west side of Johnson's Bay.

A&W Root Beer stand

From the 1950s through the early 80's, Jack'sA&W Root Beer

A&W Root Beer is an American brand of root beer that was founded in 1919 by Roy W. Allen – A&W root beer's official history and primarily available in the United States and Canada. Allen partnered with Frank Wright in 1922, creating the A&W ...

Stand on E. Pickwick Drive adjacent to the bridge over the main channel and on the east side of the channel. This root beer stand was accessible by boat and car serving standard hamburger stand fare. At the time, just the A&W, Angler's Cove, and Waco had food available by boat. The A&W is now The Channel Marker Restaurant.

Boating on Wawasee

Early boating on Wawasee

Steamboats

*The ''Anna Jones'', asteam tug

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, suc ...

named after Abram B. Jones' daughter, was purchased in Chicago in the mid-1880s. It was brought to Wawasee via the B&O Railroad and unloaded at the channel between Syracuse Lake

Syracuse Lake is a natural lake bordering Syracuse in Kosciusko County, Indiana, United States.

Location

Syracuse Lake is bordered on the west by N. Front Street, Pickwick Road and the B&O Railroad on the south. On the east it is bordered by E. ...

and Wawasee. It was then cut in half and a center section added making it roughly 40–45 feet in length.

*The ''Anna Jones II'', a steam yacht

A steam yacht is a class of luxury or commercial yacht with primary or secondary steam propulsion in addition to the sails usually carried by yachts.

Origin of the name

The English steamboat entrepreneur George Dodd (1783–1827) used the term ...

was purchased by Abram Jones about 6 years after the ''Anna Jones''. Capable of holding 100 people, it was the largest boat to ever ply Turkey Lake.

*The ''Gazelle'', brought to Wawasee in 1885 was another steam powered yacht with screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

and size of about with no sail rigging.

Sailboats

*The ''Anita'' was asloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

built by Higgins & Gifford of Glouschester and owned by Walter Nordyke.

*The ''La Cigale'' and sister boat ''Margaret'' were designed by Dr. Harry S. Hicks of Indianapolis and were built in the barn behind the Jones Hotel. They were the first flat bottomed scow

A scow is a smaller type of barge. Some scows are rigged as sailing scows. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, scows carried cargo in coastal waters and inland waterways, having an advantage for navigating shallow water or small harbours. S ...

s on Turkey Lake.

*The ''Keflin'', the lakes first fin keel sailing yacht was built behind the Jones Hotel. Its unique feature was a torpedo shaped ballast

Ballast is material that is used to provide stability to a vehicle or structure. Ballast, other than cargo, may be placed in a vehicle, often a ship or the gondola of a balloon or airship, to provide stability. A compartment within a boat, ship, ...

of several hundred pounds on the keel's end. It was said to be impossible to capsize the ''Keflin''.

*The ''Mary Louise'' was a large sail cabin yacht having the largest sail area of any boat on the lake.

*The ''Eleanor'' was an catboat

A catboat (alternate spelling: cat boat) is a sailboat with a single sail on a single mast set well forward in the bow of a very beamy and (usually) shallow draft hull. Typically they are gaff rigged, though Bermuda rig is also used. Most are f ...

owned by H.S. Tucker and built in Gloucester, Massachusetts.

*The ''Cynthia'' was a sloop sporting of sails and 1 ton of ballast owned by Col. Eli Lilly.

*The ''Emanon'' and ''Leirion'' were A-Scow

The A Scow is an American scow-hulled sailing dinghy that was designed by John O. Johnson as a racer and first built in 1901.

The A Scow design was developed into the V38, by Victory by Design, LLC in 2005.

Production

The design was initi ...

s built at the start of the 20th century. These two boats participated in the 1901 Inland Lake Yachting Association races at Green Lake, Wisconsin

Green Lake is a city in Green Lake County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 960 at the 2010 census. The city is located on the north side of Green Lake. The city of Green Lake is the county seat for the county of Green Lake. The Tow ...

.

Events

Proposed draining of Wawasee

In the late 1880s a group of farmers owningswampland

A swamp is a forested wetland.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p. Swamps are considered to be transition zones because both land and water play a role in ...

around Wawasee tried to gain control of the dam at Syracuse with the aim of destroying it to increase their area. The B&O Railroad and Cedar Beach Club defeated the farmers in the Indiana Supreme Court

The Indiana Supreme Court, established by Article 7 of the Indiana Constitution, is the highest judicial authority in the state of Indiana. Located in Indianapolis, Indiana, Indianapolis, the Court's chambers are in the north wing of the Indiana ...

. In 1883 B.F. Crow, who owned the dam and lying southwest of it, died. A new dam was proposed at Wawasee's outlet near Oakwood Park or near further north on the main channel near the B&O trestle

ATLAS-I (Air Force Weapons Lab Transmission-Line Aircraft Simulator), better known as Trestle, was a unique electromagnetic pulse (EMP) generation and testing apparatus built between 1972 and 1980 during the Cold War at Sandia National Laborato ...

. To ensure success, Colonel Eli Lilly

Eli Lilly (July 8, 1838 – June 6, 1898) was an American soldier, pharmacist, chemist, and businessman who founded the Eli Lilly and Company pharmaceutical corporation. Lilly enlisted in the Union Army during the American Civil War and ...

purchased the property for $3000. In 1895 the Syracuse Water Power Company came into existence with stockholders being the B&O Railroad and wealthy cottage owners. Officers of the power company were Mr. Settler, president of the B&O; Col. Eli Lilly as vice-president; a Mr. Blair, secretary; Mr. Ovid Butler

Ovid Butler (February 7, 1801 – July 12, 1881) was an American attorney, newspaper publisher, abolitionist, and university founder from the state of Indiana. Butler University in Indianapolis, Indiana, is named after him.

Personal life

Butler ...

, treasurer; and Mr. J.P. Dolan, a Syracuse lawyer as legal council.

The abduction of Laura Sargent

In the early 20th century Laura Sargent was abducted on the north side of Wawasee by an Ogden's Island resident by the name of Patterson. Patterson and his wife were friends of the Sargents but that friendship soured when the Sargents had taken the side of Mrs. Patterson over Mr. Patterson's drinking problem. Patterson rented a car and employed its owner by posing as aU.S. marshal

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforceme ...

. The abduction took place when Sargent's buggy was stopped by Patterson and at gunpoint forced into the car leaving the elderly buggy driver behind. Patterson had the driver head for Millersburg. While there, Patterson left the car and during his absence, Mrs. Sargent escaped from the car and hid. By this time, the elderly man alerted authorities and posse

Posse is a shortened form of posse comitatus, a group of people summoned to assist law enforcement. The term is also used colloquially to mean a group of friends or associates.

Posse may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Posse'' (1975 ...

s were formed. While Patterson drove down the main street of Millersburg searching for Sargent, he came upon one of the posses and pulled out a handgun, opening fire on the posse. Ironically his own brother-in-law was a posse member and shot Patterson in the head.

Sturgeon in Wawasee

Sturgeon

Sturgeon is the common name for the 27 species of fish belonging to the family Acipenseridae. The earliest sturgeon fossils date to the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretace ...

, an elusive, primitive, and rare, fish have been caught on occasion in Wawasee. The first account was around 1855 when Jake Renfro and three others by the last names of Kitson, Etter, and Snyder speared a sturgeon in the main channel between Syracuse Lake

Syracuse Lake is a natural lake bordering Syracuse in Kosciusko County, Indiana, United States.

Location

Syracuse Lake is bordered on the west by N. Front Street, Pickwick Road and the B&O Railroad on the south. On the east it is bordered by E. ...

and Wawasee. In the 1870s, Jim Jones, the pilot of the steamboat ''Anna Jones'', saw a sturgeon while ice fishing

Ice fishing is the practice of catching fish with lines and fish hooks or spears through an opening in the ice on a frozen body of water. Ice fishers may fish in the open or in heated enclosures, some with bunks and amenities.

Shelters

Longer ...

. The latest account was in 1991 when a sturgeon estimated at over 90 pounds was caught and released by a local fisherman, David Riddle. Sturgeon are an endangered species and protected.

The Great Wawasee Storm of 1943

On Wednesday, July 21, 1943 a largethunderstorm

A thunderstorm, also known as an electrical storm or a lightning storm, is a storm characterized by the presence of lightning and its acoustic effect on the Earth's atmosphere, known as thunder. Relatively weak thunderstorms are someti ...

mushroomed over the southwest tip of Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

and moved southeast rapidly. At 6:05 pm the storm hit Elkhart ripping trees from the ground and blowing down power lines. By 6:10 the leading edge of the storm had traveled the from Elkhart to Goshen. In New Paris two smokestacks weighing 4 short ton

The short ton (symbol tn) is a measurement unit equal to . It is commonly used in the United States, where it is known simply as a ton,

although the term is ambiguous, the single word being variously used for short, long, and metric ton.

The vari ...

s each were destroyed. At 6:30 trees were falling in Syracuse and in minutes waves on Wawasee were at with a driving rain and hail

Hail is a form of solid precipitation. It is distinct from ice pellets (American English "sleet"), though the two are often confused. It consists of balls or irregular lumps of ice, each of which is called a hailstone. Ice pellets generally fal ...

. Six boaters on Wawasee; Sergeant Lloyd Burkholder (25) of Goshen, Dean Yoder (21) of Elkhart, Lloyd Conklin (21) of Goshen, Dorothy Beckerich (21) of Indianapolis, Billie Binkley (20), and Virginia Rush (20), lost their lives./ref>

Sources

* Lilly, Eli. Early Wawasee Days. {{Indiana HistoryWawasee Wawasee or Wawaausee often contracted into Wawbee and known as ("Full Moon") was a Miami chief who lived in what is now Kosciusko County, Indiana, in the United States. He was brother to Miami chief Papakeecha.

Wawasee was a signatory to the Treaty ...

Wawasee Wawasee or Wawaausee often contracted into Wawbee and known as ("Full Moon") was a Miami chief who lived in what is now Kosciusko County, Indiana, in the United States. He was brother to Miami chief Papakeecha.

Wawasee was a signatory to the Treaty ...

History of Kosciusko County, Indiana