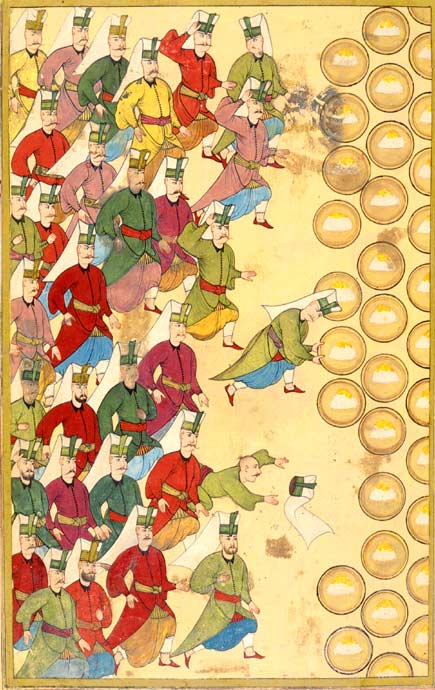

Janissary Recruitment In The Balkans-Suleymanname on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite

From the 1380s to 1648, the Janissaries were gathered through the system, which was abolished in 1648. This was the taking (enslaving) of non-Muslim boys, notably Anatolian and Balkan Christians; Jews were never subject to ', nor were children from Turkic families. According to the ''

From the 1380s to 1648, the Janissaries were gathered through the system, which was abolished in 1648. This was the taking (enslaving) of non-Muslim boys, notably Anatolian and Balkan Christians; Jews were never subject to ', nor were children from Turkic families. According to the '' It was a similar system to the Iranian

It was a similar system to the Iranian

The first Janissary units were formed from prisoners of war and slaves, probably as a result of the sultan taking his traditional one-fifth share of his army's plunder in kind rather than cash; however the continuing enslaving of dhimmi constituted a continuing abuse of a subject population. For a while, the Ottoman government supplied the Janissary corps with recruits from the devşirme system. Children were kidnapped at a young age and turned into soldiers in an attempt to make the soldiers faithful to the sultan. The social status of devşirme recruits took on an immediate positive change, acquiring a greater guarantee of governmental rights and financial opportunities. Nevertheless in poor areas officials were bribed by parents to make them take their sons, thus they would have better chances in life. Initially the recruiters favoured

The first Janissary units were formed from prisoners of war and slaves, probably as a result of the sultan taking his traditional one-fifth share of his army's plunder in kind rather than cash; however the continuing enslaving of dhimmi constituted a continuing abuse of a subject population. For a while, the Ottoman government supplied the Janissary corps with recruits from the devşirme system. Children were kidnapped at a young age and turned into soldiers in an attempt to make the soldiers faithful to the sultan. The social status of devşirme recruits took on an immediate positive change, acquiring a greater guarantee of governmental rights and financial opportunities. Nevertheless in poor areas officials were bribed by parents to make them take their sons, thus they would have better chances in life. Initially the recruiters favoured

When a non-Muslim boy was recruited under the

When a non-Muslim boy was recruited under the

The corps was organized in ''orta''s (literally: center). An ''orta'' (equivalent to a

The corps was organized in ''orta''s (literally: center). An ''orta'' (equivalent to a

During the initial period of formation, Janissaries were expert

During the initial period of formation, Janissaries were expert

Image:OttomanJanissariesAndDefendingKnightsOfStJohnSiegeOfRhodes1522.jpg, Janissaries battling the

As Janissaries became aware of their own importance, they began to desire a better life. By the early 17th century Janissaries had such prestige and influence that they dominated the government. They could mutiny, dictate policy, and hinder efforts to modernize the army structure. Additionally, the Janissaries found they could change Sultans as they wished through

As Janissaries became aware of their own importance, they began to desire a better life. By the early 17th century Janissaries had such prestige and influence that they dominated the government. They could mutiny, dictate policy, and hinder efforts to modernize the army structure. Additionally, the Janissaries found they could change Sultans as they wished through

The extravagant parties of the Ottoman ruling classes during the

The extravagant parties of the Ottoman ruling classes during the

Leopold von Ranke, tran:Louisa Hay Ker p 119–20 In 1807 a Janissary revolt deposed Sultan

The military music of the Janissaries was noted for its powerful percussion and shrill winds combining ''kös'' (giant

The military music of the Janissaries was noted for its powerful percussion and shrill winds combining ''kös'' (giant

online

* * Benesch, Oleg. "Comparing Warrior Traditions: How the Janissaries and Samurai Maintained Their Status and Privileges During Centuries of Peace." ''Comparative Civilizations Review'' 55.55 (2006): 6:37-5

Online

* * Cleveland, William L. ''A History of the Modern Middle East'' (Boulder: Westview, 2004) * Goodwin, Godfrey (2001). ''The Janissaries''. UK: Saqi Books. ; anecdotal and not scholarly says Aksan (1998) * * * * Kitsikis, Dimitri, (1985, 1991, 1994). ''L'Empire ottoman''. Paris,: Presses Universitaires de France. * * * * Shaw, Stanford J. (1976). ''History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey'' (Vol. I). New York: Cambridge University Press. * Shaw, Stanford J. & Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977). ''History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey'' (Vol. II). New York: Cambridge University Press. *

History of the Janissary Music

(not yet exploited)

"Janissary," ''Britannica.com''

{{Authority control 1360s establishments in the Ottoman Empire Military units and formations disestablished in 1826 Infantry Islam and violence Warfare of the Middle Ages Military units and formations of the medieval Islamic world Military units and formations of the Ottoman Empire Turkish words and phrases Slaves from the Ottoman Empire Christians from the Ottoman Empire Military units and formations established in the 14th century Military slavery Bektashi Order 1826 disestablishments in the Ottoman Empire

infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

units that formed the Ottoman Sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı padişahları), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to its dissolution in 1922. At its hei ...

's household troops

Household Division is a term used principally in the Commonwealth of Nations to describe a country's most elite or historically senior military units, or those military units that provide ceremonial or protective functions associated directly with ...

and the first modern standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars or n ...

in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan

Orhan Ghazi ( ota, اورخان غازی; tr, Orhan Gazi, also spelled Orkhan, 1281 – March 1362) was the second bey of the Ottoman Beylik from 1323/4 to 1362. He was born in Söğüt, as the son of Osman I.

In the early stages of his re ...

(1324–1362), during the Viziership of Alaeddin.

Janissaries began as elite corps made up through the devşirme

Devshirme ( ota, دوشیرمه, devşirme, collecting, usually translated as "child levy"; hy, Մանկահավաք, Mankahavak′. or "blood tax"; hbs-Latn-Cyrl, Danak u krvi, Данак у крви, mk, Данок во крв, Danok vo krv ...

system of child levy, by which Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

Albanians

The Albanians (; sq, Shqiptarët ) are an ethnic group and nation native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, culture, history and language. They primarily live in Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Se ...

, Romanians

The Romanians ( ro, români, ; dated exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group. Sharing a common Culture of Romania, Romanian culture and Cultural heritage, ancestry, and speaking the Romanian language, they l ...

, Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, ''hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diaspora ...

, Bulgarians

Bulgarians ( bg, българи, Bǎlgari, ) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and the rest of Southeast Europe.

Etymology

Bulgarians derive their ethnonym from the Bulgars. Their name is not completely understo ...

, Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic, G ...

, Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

and Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their na ...

were taken, levied, subjected to circumcision

Circumcision is a surgical procedure, procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin ...

and conversion to Islam

Conversion to Islam is accepting Islam as a religion or faith and rejecting any other religion or irreligion. Requirements

Converting to Islam requires one to declare the '' shahādah'', the Muslim profession of faith ("there is no god but Allah; ...

, and incorporated into the Ottoman army

The military of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun silahlı kuvvetleri) was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire.

Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the ...

. They became famed for internal cohesion cemented by strict discipline and order. Unlike typical slaves, they were paid regular salaries. Forbidden to marry before the age of 40 or engage in trade, their complete loyalty to the Sultan was expected. By the seventeenth century, due to a dramatic increase in the size of the Ottoman standing army, the corps' initially strict recruitment policy was relaxed. Civilians bought their way into it in order to benefit from the improved socioeconomic status it conferred upon them. Consequently, the corps gradually lost its military character, undergoing a process that has been described as "civilianization".

The Janissaries were a formidable military unit in the early years, but as Western Europe modernized its military organization and technology, the Janissaries became a reactionary force that resisted all change. Steadily the Ottoman military power became outdated, but when the Janissaries felt their privileges were being threatened, or outsiders wanted to modernize them, or they might be superseded by their cavalry rivals, they rose in rebellion. By the time the Janissaries were suppressed, it was too late for Ottoman military power to catch up with the West. The corps was abolished by Sultan Mahmud II

Mahmud II ( ota, محمود ثانى, Maḥmûd-u s̠ânî, tr, II. Mahmud; 20 July 1785 – 1 July 1839) was the 30th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839.

His reign is recognized for the extensive administrative, ...

in 1826 in the Auspicious Incident

The Auspicious Incident (or EventGoodwin, pp. 296–299.) (Ottoman Turkish: ''Vaka-i Hayriye'', "Fortunate Event" in Constantinople; ''Vaka-i Şerriyye'', "Unfortunate Incident" in the Balkans) was the forced disbandment of the centuries-old Jan ...

, in which 6,000 or more were executed.

Origins and history

The formation of the Janissaries has been dated to the reign ofMurad I

Murad I ( ota, مراد اول; tr, I. Murad, Murad-ı Hüdavendigâr (nicknamed ''Hüdavendigâr'', from fa, خداوندگار, translit=Khodāvandgār, lit=the devotee of God – meaning "sovereign" in this context); 29 June 1326 – 15 Jun ...

(r. 1362–1389), the third ruler of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. The Ottomans instituted a tax of one-fifth on all slaves taken in war, and it was from this pool of manpower that the sultans first constructed the Janissary corps as a personal army loyal only to the sultan.

From the 1380s to 1648, the Janissaries were gathered through the system, which was abolished in 1648. This was the taking (enslaving) of non-Muslim boys, notably Anatolian and Balkan Christians; Jews were never subject to ', nor were children from Turkic families. According to the ''

From the 1380s to 1648, the Janissaries were gathered through the system, which was abolished in 1648. This was the taking (enslaving) of non-Muslim boys, notably Anatolian and Balkan Christians; Jews were never subject to ', nor were children from Turkic families. According to the ''Encyclopedia Britannica

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles ...

'', "in early days, all Christians were enrolled indiscriminately. Later, those from what is now Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

, Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and He ...

, and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

were preferred."

The Janissaries were ' (sing. ''kapıkulu

''Kapıkulu'' ( ota, قپوقولو اوجاغی, ''Kapıkulu Ocağı'', "Slaves of the Sublime Porte") was the collective name for the Household Division of the Ottoman Sultans. They included the Janissary infantry corps as well as the Six Div ...

''), "door servants" or "slaves of the Porte

Porte may refer to:

*Sublime Porte, the central government of the Ottoman empire

*Porte, Piedmont, a municipality in the Piedmont region of Italy

*John Cyril Porte, British/Irish aviator

*Richie Porte, Australian professional cyclist who competes ...

", neither freemen nor ordinary slaves ('). They were subjected to strict discipline, but were paid salaries and pensions upon retirement and formed their own distinctive social class. As such, they became one of the ruling classes of the Ottoman Empire, rivalling the Turkish aristocracy. The brightest of the Janissaries were sent to the palace institution, Enderun. Through a system of meritocracy

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods and/or political power are vested in individual people based on talent, effort, and achiev ...

, the Janissaries held enormous power, stopping all efforts to reform the military.

According to military historian Michael Antonucci and economic historians Glenn Hubbard and Tim Kane, the Turkish administrators would scour their regions (but especially the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

) every five years for the strongest sons of the sultan's Christian subjects. These boys (usually between the ages of 6 and 14) were then taken from their parents, circumcised

Circumcision is a surgical procedure, procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin ...

, and sent to Turkish families in the provinces to be raised as Muslims and learn Turkish language and customs. Once their military training began, they were subjected to severe discipline, being prohibited from growing a beard, taking up a skill other than soldiering, and marrying. As a result, the Janissaries were extremely well-disciplined troops and became members of the ' class, the first-class citizens or military class. Most were of non-Muslim origin because it was not permissible to enslave a Muslim.

It was a similar system to the Iranian

It was a similar system to the Iranian Safavid

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often conside ...

, Afsharid

Afsharid Iran ( fa, ایران افشاری), also referred as the Afsharid Empire was an Iranian empire established by the Turkoman Afshar tribe in Iran's north-eastern province of Khorasan, ruling Iran (Persia). The state was ruled by the ...

, and Qajar era

Qajar Iran (), also referred to as Qajar Persia, the Qajar Empire, '. Sublime State of Persia, officially the Sublime State of Iran ( fa, دولت علیّه ایران ') and also known then as the Guarded Domains of Iran ( fa, ممالک م ...

''ghilman

Ghilman (singular ar, غُلاَم ',Other standardized transliterations: '' / ''. . plural ')Other standardized transliterations: '' / ''. . were slave-soldiers and/or mercenaries in the armies throughout the Islamic world, such as the Safavi ...

s'', who were drawn from converted Circassians

The Circassians (also referred to as Cherkess or Adyghe; Adyghe and Kabardian: Адыгэхэр, romanized: ''Adıgəxər'') are an indigenous Northwest Caucasian ethnic group and nation native to the historical country-region of Circassia in ...

, Georgians

The Georgians, or Kartvelians (; ka, ქართველები, tr, ), are a nation and indigenous Caucasian ethnic group native to Georgia and the South Caucasus. Georgian diaspora communities are also present throughout Russia, Turkey, G ...

, and Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, ''hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diaspora ...

, and in the same way as with the Ottoman's Janissaries who had to replace the unreliable ghazis

A ''ghazi'' ( ar, غازي, , plural ''ġuzāt'') is an individual who participated in ''ghazw'' (, '' ''), meaning military expeditions or raiding. The latter term was applied in early Islamic literature to expeditions led by the Islamic prophe ...

. They were initially created as a counterbalance to the tribal, ethnic and favoured interests the Qizilbash

Qizilbash or Kizilbash ( az, Qızılbaş; ota, قزيل باش; fa, قزلباش, Qezelbāš; tr, Kızılbaş, lit=Red head ) were a diverse array of mainly Turkoman Shia militant groups that flourished in Iranian Azerbaijan, Anatolia, the ...

gave, which make a system imbalanced.

In the late 16th century, a sultan gave in to the pressures of the Corps and permitted Janissary children to become members of the Corps, a practice strictly forbidden for the previous 300 years. According to paintings of the era, they were also permitted to grow beards. Consequently, the formerly strict rules of succession became open to interpretation. While they advanced their own power, the Janissaries also helped to keep the system from changing in other progressive ways, and according to some scholars the corps shared responsibility for the political stagnation of Istanbul.

Greek Historian Dimitri Kitsikis

Dimitri Kitsikis ( el, Δημήτρης Κιτσίκης; 2 June 1935 – 28 August 2021) was a Greek Turkologist, Sinologist and Professor of International Relations and Geopolitics. He also published poetry in French and Greek.

Life

Dimitri K ...

in his book ''Türk Yunan İmparatorluğu'' ("Turco-Greek Empire")Kitsikis, Dimitri (1996). ''Türk Yunan İmparatorluğu''. Istanbul, Simurg Kitabevi states that many Bosnian Christian families were willing to comply with the ''devşirme'' because it offered a possibility of social advancement. Conscripts could one day become Janissary colonels, statesmen who might one day return to their home region as governors, or even Grand Vizier

Grand vizier ( fa, وزيرِ اعظم, vazîr-i aʾzam; ota, صدر اعظم, sadr-ı aʾzam; tr, sadrazam) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. The office of Grand Vizier was first ...

s or Beylerbey

''Beylerbey'' ( ota, بكلربكی, beylerbeyi, lit=bey of beys, meaning the 'commander of commanders' or 'lord of lords') was a high rank in the western Islamic world in the late Middle Ages and early modern period, from the Anatolian Seljuks ...

s (governor generals).

Some of the most famous Janissaries include George Kastrioti Skanderbeg

, reign = 28 November 1443 – 17 January 1468

, predecessor = Gjon Kastrioti

, successor = Gjon Kastrioti II

, spouse = Donika Arianiti

, issue = Gjon Kastrioti II

, royal house = Kastrioti

, father ...

, an Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

who defected and led a 25‑year Albanian revolt against the Ottomans. Another was Sokollu Mehmed Paşa

Sokollu Mehmed Pasha ( ota, صوقوللى محمد پاشا, Ṣoḳollu Meḥmed Pașa, tr, Sokollu Mehmet Paşa; ; ; 1506 – 11 October 1579) was an Ottoman statesman most notable for being the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire. Born in ...

, a Bosnian Serb

The Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sr-Cyrl, Срби у Босни и Херцеговини, Srbi u Bosni i Hercegovini) are one of the three constitutive nations (state-forming nations) of the country, predominantly residing in the politi ...

who became a grand vizier, served three sultans, and was the de facto ruler of the Ottoman Empire for more than 14 years.

Characteristics

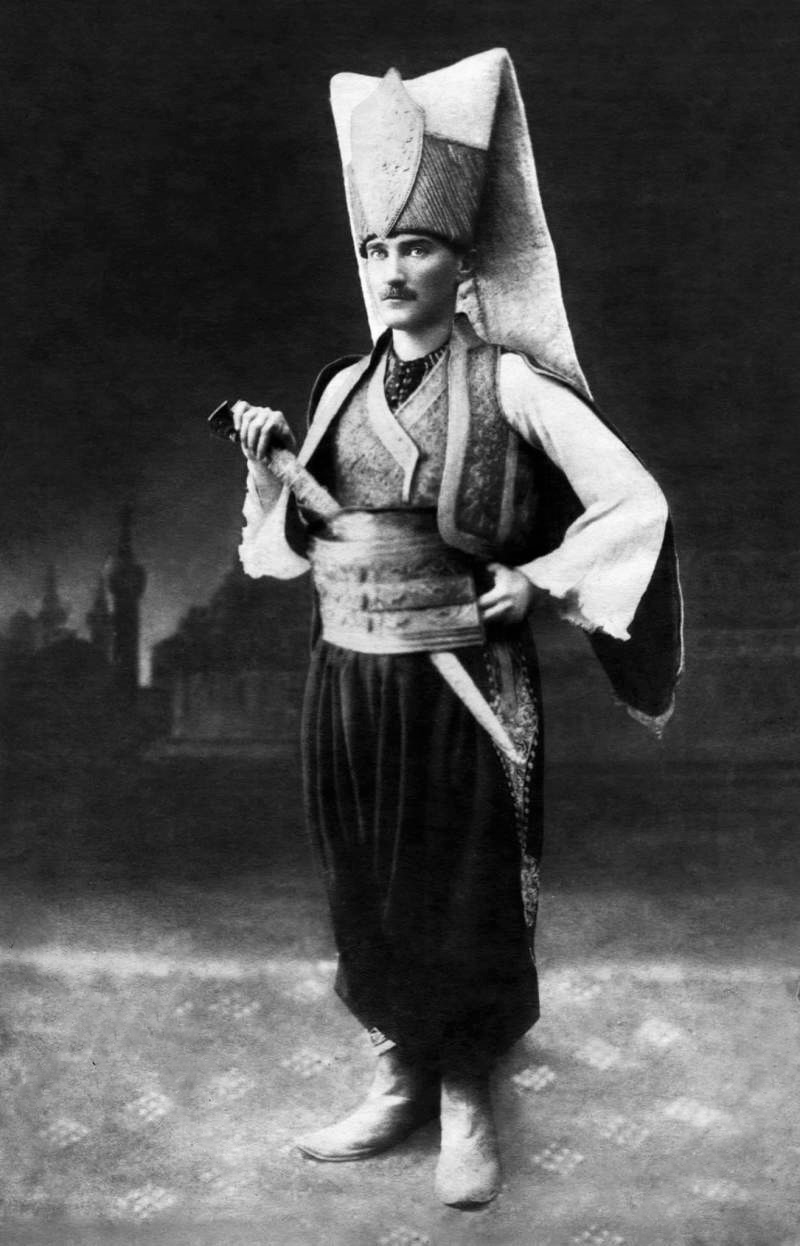

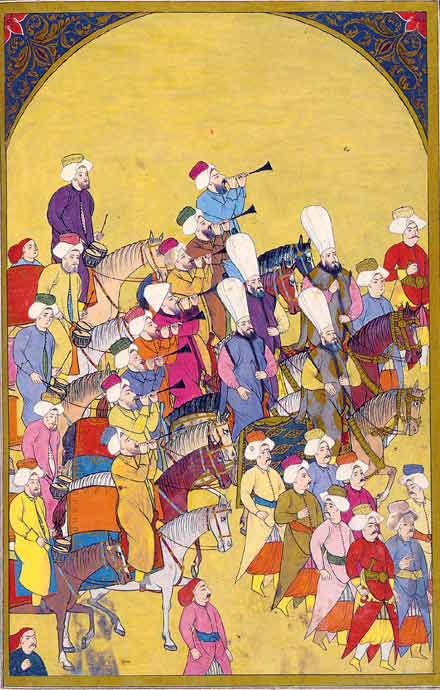

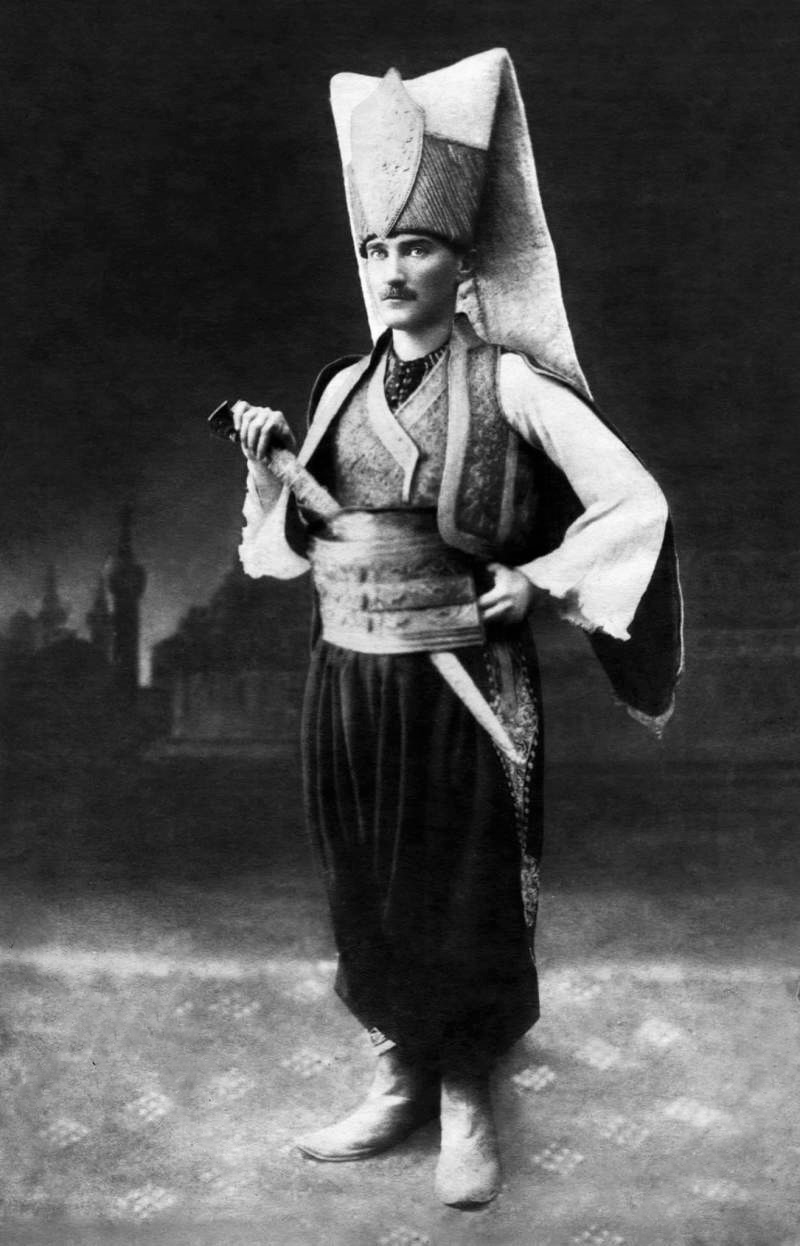

The Janissary corps were distinctive in a number of ways. They wore uniqueuniform

A uniform is a variety of clothing worn by members of an organization while participating in that organization's activity. Modern uniforms are most often worn by armed forces and paramilitary organizations such as police, emergency services, se ...

s, were paid regular salaries (including bonuses) for their service, marched to music (the mehter

Ottoman military bands are the oldest recorded military marching band in the world. Though they are often known by the word ''Mehter'' ( ota, مهتر, plural: مهتران ''mehterân''; from "senior" in Persian) in West Europe, that word, prop ...

), lived in barracks and were the first corps to make extensive use of firearms. A Janissary battalion was a close-knit community, effectively the soldier's family. By tradition, the Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

himself, after authorizing the payments to the Janissaries, visited the barracks dressed as a janissary trooper, and received his pay alongside the other men of the First Division. They also served as policemen, palace guards, and firefighters during peacetime. The Janissaries also enjoyed far better support on campaign than other armies of the time. They were part of a well-organized military machine, in which one support corps prepared the roads while others pitched tents and baked the bread. Their weapons and ammunition were transported and re-supplied by the cebeci corps. They campaigned with their own medical teams of Muslim and Jewish surgeons and their sick and wounded were evacuated to dedicated mobile hospitals set up behind the lines.

These differences, along with an impressive war-record, made the janissaries a subject of interest and study by foreigners during their own time. Although eventually the concept of a modern army incorporated and surpassed most of the distinctions of the janissaries and the corps was eventually dissolved, the image of the janissary has remained as one of the symbols of the Ottomans in the western psyche. By the mid-18th century, they had taken up many trades and gained the right to marry and enroll their children in the corps and very few continued to live in the barracks. Many of them became administrators and scholars. Retired or discharged janissaries received pensions, and their children were also looked after.

Recruitment, training and status

The first Janissary units were formed from prisoners of war and slaves, probably as a result of the sultan taking his traditional one-fifth share of his army's plunder in kind rather than cash; however the continuing enslaving of dhimmi constituted a continuing abuse of a subject population. For a while, the Ottoman government supplied the Janissary corps with recruits from the devşirme system. Children were kidnapped at a young age and turned into soldiers in an attempt to make the soldiers faithful to the sultan. The social status of devşirme recruits took on an immediate positive change, acquiring a greater guarantee of governmental rights and financial opportunities. Nevertheless in poor areas officials were bribed by parents to make them take their sons, thus they would have better chances in life. Initially the recruiters favoured

The first Janissary units were formed from prisoners of war and slaves, probably as a result of the sultan taking his traditional one-fifth share of his army's plunder in kind rather than cash; however the continuing enslaving of dhimmi constituted a continuing abuse of a subject population. For a while, the Ottoman government supplied the Janissary corps with recruits from the devşirme system. Children were kidnapped at a young age and turned into soldiers in an attempt to make the soldiers faithful to the sultan. The social status of devşirme recruits took on an immediate positive change, acquiring a greater guarantee of governmental rights and financial opportunities. Nevertheless in poor areas officials were bribed by parents to make them take their sons, thus they would have better chances in life. Initially the recruiters favoured Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

and Albanians

The Albanians (; sq, Shqiptarët ) are an ethnic group and nation native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, culture, history and language. They primarily live in Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Se ...

. As borders of the Ottoman Empire expanded, the ''devşirme'' was extended to include Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, ''hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diaspora ...

, Bulgarians

Bulgarians ( bg, българи, Bǎlgari, ) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and the rest of Southeast Europe.

Etymology

Bulgarians derive their ethnonym from the Bulgars. Their name is not completely understo ...

, Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic, G ...

, Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Urali ...

, Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their na ...

and later islamized people from Bosnia and Herzegovina, in rare instances, Romanians

The Romanians ( ro, români, ; dated exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group. Sharing a common Culture of Romania, Romanian culture and Cultural heritage, ancestry, and speaking the Romanian language, they l ...

, Georgians

The Georgians, or Kartvelians (; ka, ქართველები, tr, ), are a nation and indigenous Caucasian ethnic group native to Georgia and the South Caucasus. Georgian diaspora communities are also present throughout Russia, Turkey, G ...

, Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian. The majority ...

and southern Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

. While the deportation and enslavement of children was sometimes desired by their parents and earned them greater social status through the Janissary corps, the ''devşirme'' could fall within the context of cultural genocide

Cultural genocide or cultural cleansing is a concept which was proposed by lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1944 as a component of genocide. Though the precise definition of ''cultural genocide'' remains contested, the Armenian Genocide Museum defines ...

. However, the freedom and power offered to janissaries could indicate that the recruitment system was more aimed to be conscription, with an added objective of somewhat homogenizing the population of a very diverse empire.

This “child levy” system was regularly implemented during the 15th-16th centuries, the first two centuries of its existence. Some historians argue this system contributed to the Ottoman states efforts at compulsory conversion and “islamization” of its non-Muslim populations. Radushev states this recruitment system can be bisected into two periods, its first, or classical period, encompassing those first two centuries of regular execution and utilization to supply recruits; and a second period which more focuses on its gradual change, decline, and ultimate abandonment, beginning in the 17th century.

In response to foreign threats, the Ottoman government chose to rapidly expand the size of the corps after the 1570s. Janissaries spent shorter periods of time in training as ''acemi oğlan''s, as the average age of recruitment increased from 13.5 in the 1490s to 16.6 in 1603. This reflected not only the Ottomans' greater need for manpower but also the shorter training time necessary to produce skilled musketeers in comparison with archers. However, this change alone was not enough to produce the necessary manpower, and consequently the traditional limitation of recruitment to boys conscripted in the ''devşirme'' was lifted. Membership was opened up to free-born Muslims, both recruits hand-picked by the commander of the Janissaries, as well as the sons of current members of the Ottoman standing army. By the middle of the seventeenth century, the ''devşirme'' had largely been abandoned as a method of recruitment.

The prescribed daily rate of pay for entry-level Janissaries in the time of Ahmet I

Ahmed I ( ota, احمد اول '; tr, I. Ahmed; 18 April 1590 – 22 November 1617) was Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1603 until his death in 1617. Ahmed's reign is noteworthy for marking the first breach in the Ottoman tradition of royal ...

was three Akçe

The ''akçe'' or ''akça'' (also spelled ''akche'', ''akcheh''; ota, آقچه; ) refers to a silver coin which was the chief monetary unit of the Ottoman Empire. The word itself evolved from the word "silver or silver money", this word is deri ...

s. Promotion to a cavalry regiment implied a minimum salary of 10 Akçes. Janissaries received a sum of 12 Akçes every three months for clothing incidentals and 30 Akçes for weaponry, with an additional allowance for ammunition as well.

Training

When a non-Muslim boy was recruited under the

When a non-Muslim boy was recruited under the devşirme

Devshirme ( ota, دوشیرمه, devşirme, collecting, usually translated as "child levy"; hy, Մանկահավաք, Mankahavak′. or "blood tax"; hbs-Latn-Cyrl, Danak u krvi, Данак у крви, mk, Данок во крв, Danok vo krv ...

system, he would first be sent to selected Turkish families in the provinces to learn Turkish, the rules of Islam (i.e. to be converted to Islam) and the customs and cultures of Ottoman society. After completing this period, acemi (new recruit) boys were gathered for training at the Enderun "acemi oğlan" school in the capital city. There, young cadets would be selected for their talents in different areas to train as engineers, artisans, riflemen, clerics, archers, artillery, and so forth. Janissaries trained under strict discipline with hard labour and in practically monastic

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic ...

conditions in ''acemi oğlan'' ("rookie" or "cadet") schools, where they were expected to remain celibate

Celibacy (from Latin ''caelibatus'') is the state of voluntarily being unmarried, sexually abstinent, or both, usually for religious reasons. It is often in association with the role of a religious official or devotee. In its narrow sense, th ...

. Unlike other Muslims, they were expressly forbidden to wear beards, only a moustache. These rules were obeyed by Janissaries, at least until the 18th century when they also began to engage in other crafts and trades, breaking another of the original rules. In the late 16th century a sultan gave in to the pressures of the Janissary Corps and permitted Janissary children to become members of the Corps, a practice strictly forbidden for 200 years. Consequently, succession rules, formerly strict, became open to interpretation. They gained their own power but kept the system from changing in other progressive ways.

For all practical purposes, Janissaries belonged to the Sultan and they were regarded as the protectors of the throne and the Sultan. Janissaries were taught to consider the corps their home and family, and the Sultan as their father. Only those who proved strong enough earned the rank of true Janissary at the age of 24 or 25. The Ocak inherited the property of dead Janissaries, thus acquiring wealth. Janissaries also learned to follow the dictates of the dervish

Dervish, Darvesh, or Darwīsh (from fa, درویش, ''Darvīsh'') in Islam can refer broadly to members of a Sufi fraternity

A fraternity (from Latin language, Latin ''wiktionary:frater, frater'': "brother (Christian), brother"; whence, ...

saint Haji Bektash Veli

Haji Bektash Veli or Wali ( fa, حاجی بکتاش ولی, Ḥājī Baktāš Walī; ota, حاجی بکتاش ولی, Hacı Bektaş-ı Veli; sq, Haxhi Bektash Veliu) (1209 – 1271) was a Muslim mystic, saint, Sayyid and philosopher from Kh ...

, disciples of whom had blessed the first troops. Bektashi

The Bektashi Order; sq, Tarikati Bektashi; tr, Bektaşi or Bektashism is an Islamic Sufi mystic movement originating in the 13th-century. It is named after the Anatolian saint Haji Bektash Wali (d. 1271). The community is currently led by ...

served as a kind of chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a Minister (Christianity), minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a laity, lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secularity, secular institution (such as a hosp ...

for Janissaries. In this and in their secluded life, Janissaries resembled Christian military orders like the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic Church, Catholic Military ord ...

. As a symbol of their devotion to the order, Janissaries wore special hats called "börk". These hats also had a holding place in front, called the "kaşıklık", for a spoon. This symbolized the "kaşık kardeşliği", or the "brotherhood of the spoon", which reflected a sense of comradeship among the Janissaries who ate, slept, fought and died together.

Even after the rapid expansion of the size of the corps at the end of the sixteenth century, the Janissaries continued to undergo strict training and discipline. The Janissaries experimented with new forms of battlefield tactics, and in 1605 became one of the first armies in Europe to implement rotating lines of volley fire in battle.

Organization

The corps was organized in ''orta''s (literally: center). An ''orta'' (equivalent to a

The corps was organized in ''orta''s (literally: center). An ''orta'' (equivalent to a battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

) was headed by a çorbaci

Chorbaji (sometimes variously transliterated as tchorbadji, chorbadzhi,

tschorbadji) (Turkish: çorbacı) (English: Soup Seller) was a military rank of the corps of Janissaries in the Ottoman Empire, used for the commander of an ''orta'' (regiment ...

. All ''orta''s together comprised the Janissary corps proper and its organization, named ''ocak'' (literally "hearth"). Suleiman I had 165 ''orta''s and the number increased over time to 196. While the Sultan was the supreme commander of the Ottoman Army and of the Janissaries in particular, the corps was organized and led by a commander, the ''ağa''. The corps was divided into three sub-corps:

* the ''cemaat'' (frontier troops; also spelled ''jemaat'' in old sources), with 101 ''orta''s

* the ''bölük'' or ''beylik'', (the Sultan's own bodyguard), with 61 ''orta''s

* the ''sekban'' or ''seymen'', with 34 ''orta''s

In addition there were also 34 ''orta''s of the ''ajemi'' (cadets). A semi-autonomous Janissary corps was permanently based in Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

, called the Odjak of Algiers

The Odjak of Algiers was a unit of the Algerine army. It was a heavily autonomous part of the Janissary Corps, acting completely independently from the rest of the corps, similar to the relationship between Algiers and the Sublime Porte. Led by ...

.

Originally Janissaries could be promoted only through seniority and within their own ''orta''. They could leave the unit only to assume command of another. Only Janissaries' own commanding officers could punish them. The rank names were based on positions in the kitchen staff or Sultan's royal hunters; 64th and 65th Orta 'Greyhound Keepers' comprised as the only Janissary cavalry, perhaps to emphasise that Janissaries were servants of the Sultan. Local Janissaries, stationed in a town or city for a long time, were known as yerliyya In the Ottoman Empire of the 17th century the ''yerliyya'' were local Janissary, Janissaries who had been sent to an urban centre many years earlier and had become fully integrated into their surroundings, often playing important roles in the commer ...

s.

Corps strength

Even though the Janissaries were part of the royal army and personal guards of the sultan, the corps was not the main force of the Ottoman military. In the classical period, Janissaries were only one-tenth of the overall Ottoman army, while the traditional Turkish cavalry made up the rest of the main battle force. According toDavid Nicolle

David C. Nicolle (born 4 April 1944) is a British historian specialising in the military history of the Middle Ages, with a particular interest in the Middle East.

David Nicolle worked for BBC Arabic before getting his MA at SOAS, University ...

, the number of Janissaries in the 14th century was 1,000 and about 6,000 in 1475. The same source estimates the number of Timarli Sipahi

''Sipahi'' ( ota, سپاهی, translit=sipâhi, label=Persian, ) were professional cavalrymen deployed by the Seljuks, and later the Ottoman Empire, including the land grant-holding (''timar'') provincial '' timarli sipahi'', which constitute ...

, the provincial cavalry which constituted the main force of the army at 40,000.

Beginning in the 1530s, the size of the Janissary corps began to dramatically expand, a result of the rapid conquests the Ottomans were carrying out during those years. Janissaries were used extensively to garrison fortresses and for siege warfare, which was becoming increasingly important for the Ottoman military. The pace of expansion increased after the 1570s, due to the initiation of a series of wars with the Safavid Empire

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often conside ...

and, after 1593, with the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

. By 1609, the size of the corps had stabilized at approximately 40,000 men, but increased again later in the century, during the period of the Cretan War (1645–69) and particularly the War of the Holy League (1683–99).

Equipment

During the initial period of formation, Janissaries were expert

During the initial period of formation, Janissaries were expert archers

Archery is the sport, practice, or skill of using a bow to shoot arrows.Paterson ''Encyclopaedia of Archery'' p. 17 The word comes from the Latin ''arcus'', meaning bow. Historically, archery has been used for hunting and combat. In mo ...

, but they began adopting firearms

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes c ...

as soon as such became available during the 1440s. The siege of Vienna in 1529 confirmed the reputation of their engineers, e.g. sappers

A sapper, also called a pioneer or combat engineer, is a combatant or soldier who performs a variety of military engineering duties, such as breaching fortifications, demolitions, bridge-building, laying or clearing minefields, preparing fie ...

and miners

A miner is a person who extracts ore, coal, chalk, clay, or other minerals from the earth through mining. There are two senses in which the term is used. In its narrowest sense, a miner is someone who works at the rock face; cutting, blasting, ...

. In melee combat they used axe

An axe ( sometimes ax in American English; see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood, to harvest timber, as a weapon, and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol. The axe has ma ...

s and kilij

A kilij (from Turkish ''kılıç'', literally "sword") or a pusat is a type of one-handed, single-edged and moderately curved scimitar used by the Seljuk Empire, Timurid Empire, Mamluk Empire, Ottoman Empire, and other Turkic khanates of Eu ...

s. Originally in peacetime they could carry only clubs or dagger

A dagger is a fighting knife with a very sharp point and usually two sharp edges, typically designed or capable of being used as a thrusting or stabbing weapon.State v. Martin, 633 S.W.2d 80 (Mo. 1982): This is the dictionary or popular-use de ...

s, unless they served as border troops. Turkish yatagan

The yatagan, yataghan or ataghan (from Turkish ''yatağan''), also called varsak, is a type of Ottoman knife or short sabre used from the mid-16th to late 19th centuries.

The yatagan was extensively used in Ottoman Turkey and in areas under im ...

swords were the signature weapon of the Janissaries, almost a symbol of the corps. Janissaries who guarded the palace (Zülüflü Baltacılar) carried long-shafted axes and halberd

A halberd (also called halbard, halbert or Swiss voulge) is a two-handed pole weapon that came to prominent use during the 13th, 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. The word ''halberd'' is cognate with the German word ''Hellebarde'', deriving from ...

s.

By the early 16th century, the Janissaries were equipped with and were skilled with musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually d ...

s. In particular, they used a massive "trench gun", firing an ball, which was "feared by their enemies". Janissaries also made extensive use of early grenades

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A modern hand grenade gene ...

and hand cannon

The hand cannon (Chinese: 手 銃 ''shŏuchòng'', or 火 銃 ''huŏchòng''), also known as the gonne or handgonne, is the first true firearm and the successor of the fire lance. It is the oldest type of small arms as well as the most mecha ...

s, such as the abus gun The Abus gun ( tr, Obüs meaning ''howitzer'') is an early form of artillery created by the Ottoman Empire. They were small, but often too heavy to carry, and many were equipped with a type of tripod. They had a caliber between to and fired a proj ...

. Pistol

A pistol is a handgun, more specifically one with the chamber integral to its gun barrel, though in common usage the two terms are often used interchangeably. The English word was introduced in , when early handguns were produced in Europe, an ...

s were not initially popular but they became so after the Cretan War (1645–1669)

The Cretan War ( el, Κρητικός Πόλεμος, tr, Girit'in Fethi), also known as the War of Candia ( it, Guerra di Candia) or the Fifth Ottoman–Venetian War, was a conflict between the Republic of Venice and her allies (chief among ...

.

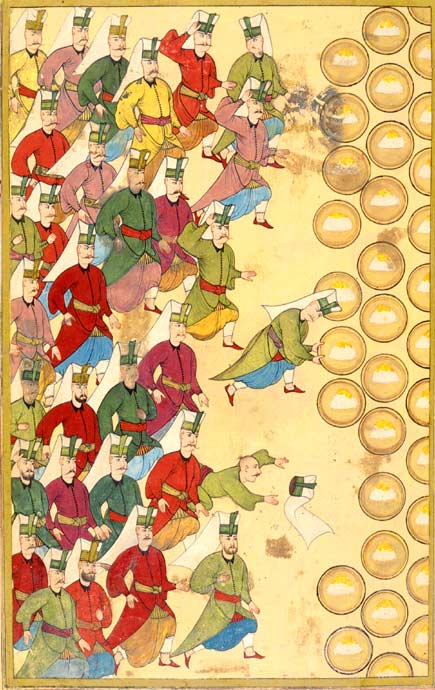

Battles

The Ottoman Empire used Janissaries in all its major campaigns, including the 1453 capture ofConstantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, the defeat of the Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo

The Mamluk Sultanate ( ar, سلطنة المماليك, translit=Salṭanat al-Mamālīk), also known as Mamluk Egypt or the Mamluk Empire, was a state that ruled Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz (western Arabia) from the mid-13th to early 16th ...

and wars against Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

. Janissary troops were always led to the battle by the Sultan himself, and always had a share of the loot. The Janissary corps was the only infantry division of the Ottoman army. In battle the Janissaries' main mission was to protect the Sultan, using cannon and smaller firearms, and holding the centre of the army against enemy attack during the strategic fake forfeit of Turkish cavalry. The Janissary corps also included smaller expert teams: explosive experts, engineers and technicians, sharpshooters (with arrow and rifle) and sappers who dug tunnels under fortresses, etc.

Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic Church, Catholic Military ord ...

, who are depicted wearing Eastern Armour. during the Siege of Rhodes in 1522.

File:1526 - Battle of Mohács.jpg, Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

, 1526.

File:Cannon battery at the Siege of Esztergom 1543.jpg, A Janissary, a pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, gener ...

and cannon batteries at the Siege of Esztergom in 1543.

File:Expedition to Revan-Shahin-Shah-nama.jpg, Sultan Murad III

Murad III ( ota, مراد ثالث, Murād-i sālis; tr, III. Murad; 4 July 1546 – 16 January 1595) was Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1574 until his death in 1595. His rule saw battles with the Habsburgs and exhausting wars with the Saf ...

's expedition to Revan

Darth Revan, later known simply as Revan, is the player character of the 2003 role-playing video game '' Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic'' and its upcoming remake by BioWare.

A former veteran Jedi knight who lived during the Old Republi ...

.

Revolts and disbandment

As Janissaries became aware of their own importance, they began to desire a better life. By the early 17th century Janissaries had such prestige and influence that they dominated the government. They could mutiny, dictate policy, and hinder efforts to modernize the army structure. Additionally, the Janissaries found they could change Sultans as they wished through

As Janissaries became aware of their own importance, they began to desire a better life. By the early 17th century Janissaries had such prestige and influence that they dominated the government. They could mutiny, dictate policy, and hinder efforts to modernize the army structure. Additionally, the Janissaries found they could change Sultans as they wished through palace coup

A palace is a grand residence, especially a royal residence, or the home of a head of state or some other high-ranking dignitary, such as a bishop or archbishop. The word is derived from the Latin name palātium, for Palatine Hill in Rome whic ...

s. They made themselves landholders and tradesmen. They would also limit the enlistment to the sons of former Janissaries who did not have to go through the original training period in the ''acemi oğlan'', as well as avoiding the physical selection, thereby reducing their military value. When Janissaries could practically extort money from the Sultan and business and family life replaced martial fervour, their effectiveness as combat troops decreased. The northern borders of the Ottoman Empire slowly began to shrink southwards after the second Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna; pl, odsiecz wiedeńska, lit=Relief of Vienna or ''bitwa pod Wiedniem''; ota, Beç Ḳalʿası Muḥāṣarası, lit=siege of Beç; tr, İkinci Viyana Kuşatması, lit=second siege of Vienna took place at Kahlenberg Mou ...

in 1683.

In 1449 they revolted for the first time, demanding higher wages, which they obtained. The stage was set for a decadent evolution, like that of the Streltsy

, image = 01 106 Book illustrations of Historical description of the clothes and weapons of Russian troops.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption =

, dates = 1550–1720

, disbanded =

, country = Tsardom of Russia

, allegiance = Streltsy D ...

of Tsar Peter's Russia or that of the Praetorian Guard

The Praetorian Guard (Latin: ''cohortēs praetōriae'') was a unit of the Imperial Roman army that served as personal bodyguards and intelligence agents for the Roman emperors. During the Roman Republic, the Praetorian Guard were an escort fo ...

which proved the greatest threat to Roman emperors, rather than effective protection. After 1451, every new Sultan felt obligated to pay each Janissary a reward and raise his pay rank (although since early Ottoman times, every other member of the Topkapi court received a pay raise as well). Sultan Selim II

Selim II ( Ottoman Turkish: سليم ثانى ''Selīm-i sānī'', tr, II. Selim; 28 May 1524 – 15 December 1574), also known as Selim the Blond ( tr, Sarı Selim) or Selim the Drunk ( tr, Sarhoş Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire ...

gave Janissaries permission to marry in 1566, undermining the exclusivity of loyalty to the dynasty. By 1622, the Janissaries were a "serious threat" to the stability of the Empire. Through their "greed and indiscipline", they were now a law unto themselves and, against modern European armies, ineffective on the battlefield as a fighting force. In 1622, the teenage Sultan Osman II

Osman II ( ota, عثمان ثانى ''‘Osmān-i sānī''; tr, II. Osman; 3 November 1604 – 20 May 1622), also known as Osman the Young ( tr, Genç Osman), was Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 26 February 1618 until his regicide on 20 May 162 ...

, after a defeat during war against Poland, determined to curb Janissaries' excesses. Outraged at becoming "subject to his own slaves", he tried to disband the Janissary corps, blaming it for the disaster during the Polish war. In the spring, hearing rumours that the Sultan was preparing to move against them, the Janissaries revolted and took the Sultan captive, imprisoning him in the notorious Seven Towers: he was murdered shortly afterward .

The extravagant parties of the Ottoman ruling classes during the

The extravagant parties of the Ottoman ruling classes during the Tulip Period

The Tulip Period, or Tulip Era (Ottoman Turkish: لاله دورى, tr, Lâle Devri), is a period in Ottoman history from the Treaty of Passarowitz on 21 July 1718 to the Patrona Halil Revolt on 28 September 1730. This was a relatively peacef ...

caused a lot of unrest among the Ottoman population. In September 1730, janissaries headed by Patrona Halil

Patrona Halil ( sq, Halil Patrona, tr, Patrona Halil; c. 1690 in Hrupishta – November 25, 1730 in Constantinople) was the instigator of a mob uprising in 1730 which replaced Sultan Ahmed III with Mahmud I and ended the Tulip period.Altınay, ...

backed in Istanbul a rebellion by 12,000 Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

troops which caused the abdication of Sultan Ahmed III

Ahmed III ( ota, احمد ثالث, ''Aḥmed-i sālis'') was Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and a son of Sultan Mehmed IV (r. 1648–1687). His mother was Gülnuş Sultan, originally named Evmania Voria, who was an ethnic Greek. He was born at H ...

and the death of the Grand Vizier Damad Ibrahim. The rebellion was crashed in three weeks with the massacre of 7,000 rebels, but it marked the end of the Tulip Era and the beginning of Sultan Mahmud I's reign. In 1804, the Dahias, the Janissary junta that ruled Serbia at the time, having taken power in the ''Sanjak of Smederevo

The Sanjak of Smederevo ( tr, Semendire Sancağı; sr, / ), also known in historiography as the Pashalik of Belgrade ( tr, Belgrad Paşalığı; sr, / ), was an Ottoman Empire, Ottoman administrative unit (sanjak), that existed between the 1 ...

'' in defiance of the Sultan, feared that the Sultan would make use of the Serbs to oust them. To forestall this they decided to execute all prominent nobles throughout Central Serbia, a move known as the Slaughter of the Knezes

The Slaughter of the Knezes ( sr, Сеча кнезова, Seča knezova) was the organized assassinations and assaults of noble Serbs in the Sanjak of Smederevo in January 1804 by the rebellious Dahije. Fearing that the Sultan would make use ...

. According to historical sources of the city of Valjevo

Valjevo (Serbian Cyrillic: Ваљево, ) is a List of cities in Serbia, city and the administrative center of the Kolubara District in western Serbia. According to the 2011 census, the administrative area of Valjevo had 90,312 inhabitants, 59,07 ...

, the heads of the murdered men were put on public display in the central square to serve as an example to those who might plot against the rule of the Janissaries. The event triggered the start of the Serbian Revolution

The Serbian Revolution ( sr, Српска револуција / ''Srpska revolucija'') was a national uprising and constitutional change in Serbia that took place between 1804 and 1835, during which this territory evolved from an Ottoman prov ...

with the First Serbian Uprising

The First Serbian Uprising ( sr, Prvi srpski ustanak, italics=yes, sr-Cyrl, Први српски устанак; tr, Birinci Sırp Ayaklanması) was an uprising of Serbs in the Sanjak of Smederevo against the Ottoman Empire from 14 February 18 ...

aimed at putting an end to the 370 years of Ottoman occupation of modern Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

.History of Servia and the Servian RevolutionLeopold von Ranke, tran:Louisa Hay Ker p 119–20 In 1807 a Janissary revolt deposed Sultan

Selim III

Selim III ( ota, سليم ثالث, Selim-i sâlis; tr, III. Selim; was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1789 to 1807. Regarded as an enlightened ruler, the Janissaries eventually deposed and imprisoned him, and placed his cousin Mustafa ...

, who had tried to modernize the army along Western European lines. This modern army that Selim III created was called Nizam-ı Cedid

The Nizam-i Cedid ( ota, نظام جديد, Niẓām-ı Cedīd, lit=new order) was a series of reforms carried out by Ottoman Sultan Selim III during the late 18th and the early 19th centuries in a drive to catch up militarily and politically wi ...

. His supporters failed to recapture power before Mustafa IV

Mustafa IV (; ota, مصطفى رابع, translit=Muṣṭafâ-yi râbiʿ; 8 September 1779 – 16 November 1808) was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1807 to 1808.

Early life

Mustafa IV was born on 8 September 1779 in Constantinople. He ...

had him killed, but elevated Mahmud II

Mahmud II ( ota, محمود ثانى, Maḥmûd-u s̠ânî, tr, II. Mahmud; 20 July 1785 – 1 July 1839) was the 30th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839.

His reign is recognized for the extensive administrative, ...

to the throne in 1808. When the Janissaries threatened to oust Mahmud II, he had the captured Mustafa executed and eventually came to a compromise with the Janissaries. Ever mindful of the threat that the Janissaries posed, the sultan spent the next years discreetly securing his position. The Janissaries' abuse of power, military ineffectiveness, resistance to reform, and the cost of salaries to 135,000 men, many of whom were not actually serving soldiers, had all become intolerable.

By 1826, the sultan was ready to move against the Janissaries in favour of a more modern military. The sultan informed them, through a fatwa

A fatwā ( ; ar, فتوى; plural ''fatāwā'' ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (''sharia'') given by a qualified '' Faqih'' (Islamic jurist) in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist i ...

, that he was forming a new army, organised and trained along modern European lines. As predicted, they mutinied, advancing on the sultan's palace. In the ensuing fight, the Janissaries' barracks were set aflame by artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

fire, resulting in 4,000 Janissary fatalities. The survivors were either exiled or executed, and their possessions were confiscated by the Sultan. This event is now called the Auspicious Incident

The Auspicious Incident (or EventGoodwin, pp. 296–299.) (Ottoman Turkish: ''Vaka-i Hayriye'', "Fortunate Event" in Constantinople; ''Vaka-i Şerriyye'', "Unfortunate Incident" in the Balkans) was the forced disbandment of the centuries-old Jan ...

. The last of the Janissaries were then put to death by decapitation in what was later called the Tower of Blood, in Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

.

After the Janissaries were disbanded by Mahmud II, he then created a new army soon after recruiting 12,000 troops. This new army was formally named the Trained Victorious Soldiers of Muhammad, the Mansure Army for short. By 1830, the army expanded to 27,000 troops and included the Sipahi cavalry. By 1838, all Ottoman fighting corps were included and the army changed its name to the Ordered troops. This military corps lasted until the end of the empire's history.

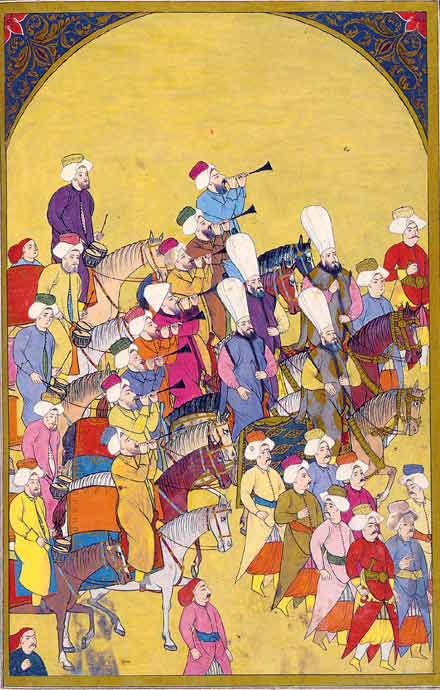

Janissary music

The military music of the Janissaries was noted for its powerful percussion and shrill winds combining ''kös'' (giant

The military music of the Janissaries was noted for its powerful percussion and shrill winds combining ''kös'' (giant timpani

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionall ...

), ''davul

The davul, dhol, tapan, atabal or tabl is a large double-headed drum that is played with mallets. It has many names depending on the country and region. These drums are commonly used in the music of the Middle East and the Balkans. These drums ...

'' (bass drum), ''zurna

The zurna (Armenian language, Armenian: զուռնա zuṙna; Classical Armenian, Old Armenian: սուռնայ suṙnay; Albanian language, Albanian: surle/surla; Persian language, Persian: karna/Kornay/surnay; Macedonian language, Macedonian: з ...

'' (a loud shawm

The shawm () is a Bore_(wind_instruments)#Conical_bore, conical bore, double-reed woodwind instrument made in Europe from the 12th century to the present day. It achieved its peak of popularity during the medieval and Renaissance periods, after ...

), ''naffir'', or ''boru'' (natural trumpet), ''çevgan'' bells, triangle

A triangle is a polygon with three Edge (geometry), edges and three Vertex (geometry), vertices. It is one of the basic shapes in geometry. A triangle with vertices ''A'', ''B'', and ''C'' is denoted \triangle ABC.

In Euclidean geometry, an ...

(a borrowing from Europe), and cymbal

A cymbal is a common percussion instrument. Often used in pairs, cymbals consist of thin, normally round plates of various alloys. The majority of cymbals are of indefinite pitch, although small disc-shaped cymbals based on ancient designs soun ...

s (''zil''), among others. Janissary music influenced European classical musicians such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

and Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

, both of whom composed music in the Turkish style. Examples include Mozart's Piano Sonata No. 11 (c. 1783), Beethoven's incidental music for ''The Ruins of Athens

''The Ruins of Athens'' (''Die Ruinen von Athen''), Op. 113, is a set of incidental music pieces written in 1811 by Ludwig van Beethoven. The music was written to accompany the play of the same name by August von Kotzebue, for the dedication of ...

'' (1811), and the final movement of Beethoven's Symphony No. 9, although the Beethoven example is now considered a march rather than Alla turca.

Sultan Mahmud II

Mahmud II ( ota, محمود ثانى, Maḥmûd-u s̠ânî, tr, II. Mahmud; 20 July 1785 – 1 July 1839) was the 30th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839.

His reign is recognized for the extensive administrative, ...

abolished the ''mehter'' band in 1826 along with the Janissary corps. Mahmud replaced the mehter band in 1828 with a European style military band trained by Giuseppe Donizetti

Giuseppe Donizetti (6 November 1788 – 12 February 1856), also known as Donizetti Pasha, was an Italian musician. From 1828 he was Instructor General of the Imperial Ottoman Music at the court of Sultan Mahmud II (1808–39).

His younger broth ...

. In modern times, although the Janissary corps no longer exists as a professional fighting force, the tradition of Mehter

Ottoman military bands are the oldest recorded military marching band in the world. Though they are often known by the word ''Mehter'' ( ota, مهتر, plural: مهتران ''mehterân''; from "senior" in Persian) in West Europe, that word, prop ...

music is carried on as a cultural and tourist attraction.

In 1952, the Janissary military band

A military band is a group of personnel that performs musical duties for military functions, usually for the armed forces. A typical military band consists mostly of wind and percussion instruments. The conductor of a band commonly bears the tit ...

, '' Mehterân'', was organized again under the auspices of the Istanbul Military Museum

Istanbul Military Museum ( tr, Askerî Müze) is dedicated to one thousand years of Turkish military history. It is one of the leading museums of its kind in the world. The museum is open to the public everyday except Mondays and Tuesdays.

T ...

. They hold performances during some national holidays as well as in some parades during days of historical importance. For more details, see Turkish music (style)

Turkish music, in the sense described here, is not the music of Turkey, but rather a musical style that was occasionally used by the European composers of the Classical music era. This music was modelled—though often only distantly—on the musi ...

and Mehter

Ottoman military bands are the oldest recorded military marching band in the world. Though they are often known by the word ''Mehter'' ( ota, مهتر, plural: مهتران ''mehterân''; from "senior" in Persian) in West Europe, that word, prop ...

.

Popular culture

* InBulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

and elsewhere, and for centuries in Ukraine, the word Janissar (яничар) is used as a synonym of the word renegade.

* ''The Janissary Tree

''The Janissary Tree'' is a historical mystery novel set in Istanbul in 1836, written by Jason Goodwin. It is the first in the Yashim the Detective series, followed by ''The Snake Stone'', ''The Bellini Card'', ''An Evil Eye'' and ''The Baklav ...

'', a novel by Jason Goodwin set in 19th-century Istanbul

* ''The Sultan's Helmsman'', a historical novel of the Ottoman Navy and Renaissance Italy

* Salman Rushdie

Sir Ahmed Salman Rushdie (; born 19 June 1947) is an Indian-born British-American novelist. His work often combines magic realism with historical fiction and primarily deals with connections, disruptions, and migrations between Eastern and Wes ...

's novel ''The Enchantress of Florence

''The Enchantress of Florence'' is the ninth novel by Salman Rushdie, published in 2008. According to Rushdie this is his "most researched book" which required "years and years of reading".

The novel was published on 11 April 2008 by Jonathan ...

'' details the life, organization, and origins of the Janissaries. One of the lead characters of the novel, Antonio Argalia, is the head of the Ottoman Janissaries.

* The novel ''Janissaries'' by David Drake

David A. Drake (born September 24, 1945) is an American author of science fiction and fantasy literature. A Vietnam War veteran who has worked as a lawyer, he is now a writer in the military science fiction genre.

Biography

Drake graduated Phi ...

* ''Muhteşem Yüzyıl

''Muhteşem Yüzyıl'' (, ) is a Turkish historical fiction television series. Written by Meral Okay and Yılmaz Şahin, it is based on the life of Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, the longest-reigning Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and his ...

'' (''The Magnificent Century'') is a 2011–2012 Turkish historical fiction television series. Written by Meral Okay

Meral Okay (, née Katı; September 20, 1959 – April 9, 2012) was a Turkish actress, film producer and screenwriter.

Early life

Okay was born on September 20, 1959 in Ankara to military judge Ata Katı and Türkan as the second child. During h ...

and Yılmaz Şahin. The Janissaries are portrayed throughout the series as part of the Sultan's royal bodyguard. The First Oath of their military order is recited in Season 1 at the Ceremony of Payment.

*The popular song in Serbian, Janissar (Јањичар) by Predrag Gojković Cune

* Janissaries are the unique unit of the Ottoman Empire in Civilization IV

''Civilization IV'' (also known as ''Sid Meier's Civilization IV'') is a 4X turn-based strategy computer game and the fourth installment of the ''Civilization'' series, and designed by Soren Johnson under the direction of Sid Meier and his vid ...

, V, expansions of VI, Cossacks (video games series)

''Cossacks'' is a series of real-time strategy video games developed by Ukraine, Ukrainian video game developer GSC Game World for Microsoft Windows.

Games

''Cossacks: European Wars'' (2001)

''Cossacks II: Napoleonic Wars'' (2005)

''Cossack ...

, Age of Empires II

''Age of Empires II: The Age of Kings'' is a real-time strategy video game developed by Ensemble Studios and published by Microsoft. Released in 1999 for Microsoft Windows and Macintosh, it is the second game in the '' Age of Empires'' series. ...

, Age of Empires III

''Age of Empires III'' is a real-time strategy video game developed by Microsoft Corporation's Ensemble Studios and published by Microsoft Game Studios. The Mac version was ported over and developed and published by Destineer's MacSoft. The PC ...

, and Rise of Nations

''Rise of Nations'' is a real-time strategy video game developed by Big Huge Games and published by Xbox Game Studios, Microsoft Game Studios in May 2003. The development was led by veteran game designer Brian Reynolds (game designer), Brian ...

.

* The Janissaries during the rule of Sultan Bayezid II

Bayezid II ( ota, بايزيد ثانى, Bāyezīd-i s̱ānī, 3 December 1447 – 26 May 1512, Turkish: ''II. Bayezid'') was the eldest son and successor of Mehmed II, ruling as Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1481 to 1512. During his reign, ...

are featured heavily in Assassin's Creed: Revelations.

* Janissaries appear in several books in the ''Lymond Chronicles

The ''Lymond Chronicles'' is a series of six historical novels written by Dorothy Dunnett and first published between 1961 and 1975. Set in mid-16th-century Europe and the Mediterranean area, the series tells the story of a young Scottish noblem ...

'' by Dorothy Dunnett

Dorothy, Lady Dunnett (née Halliday, 25 August 1923 – 9 November 2001) was a Scottish novelist best known for her historical fiction. Dunnett is most famous for her six novel series set during the 16th century, which concern the fictiti ...

.

* In the song "Winged Hussars" by Sabaton about the Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna; pl, odsiecz wiedeńska, lit=Relief of Vienna or ''bitwa pod Wiedniem''; ota, Beç Ḳalʿası Muḥāṣarası, lit=siege of Beç; tr, İkinci Viyana Kuşatması, lit=second siege of Vienna took place at Kahlenberg Mou ...

1683 the question is asked if "Janissaries are you ready to die?" to illustrate the impact of the arrival of the winged hussars in the battle.

See also

* Devşirme system *Ghilman

Ghilman (singular ar, غُلاَم ',Other standardized transliterations: '' / ''. . plural ')Other standardized transliterations: '' / ''. . were slave-soldiers and/or mercenaries in the armies throughout the Islamic world, such as the Safavi ...

* Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

* Military of the Ottoman Empire

The military of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun silahlı kuvvetleri) was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire.

Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the ...

* Saqaliba

Saqaliba ( ar, صقالبة, ṣaqāliba, singular ar, صقلبي, ṣaqlabī) is a term used in medieval Arabic sources to refer to Slavs and other peoples of Central, Southern, and Eastern Europe, or in a broad sense to European slaves. The t ...

* Genízaro

are detribalized Native Americans who, by war or payment of ransom, were taken into Hispano and Puebloan villages as indentured servants, shepherds, general laborers, etc., in Santa Fe de Nuevo México in New Spain, which is modern New Mexico, ...

* Ottoman decline thesis

The Ottoman decline thesis or Ottoman decline paradigm ( tr, Osmanlı Gerileme Tezi) is an obsolete

*

*

*

*

* Leslie Peirce, "Changing Perceptions of the Ottoman Empire: the Early Centuries," ''Mediterranean Historical Review'' 19/1 (20 ...

* The Auspicious Incident

The Auspicious Incident (or EventGoodwin, pp. 296–299.) (Ottoman Turkish: ''Vaka-i Hayriye'', "Fortunate Event" in Constantinople; ''Vaka-i Şerriyye'', "Unfortunate Incident" in the Balkans) was the forced disbandment of the centuries-old Ja ...

* Agha, a civilian and military title in the Ottoman Empire

* Malassay

A Malassay ( Harari: መለሳይ ''Mäläsay'') was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Adal Sultanate's household troops. According to Manfred Kropp, Malassay were the Harari armed forces.

Etymology

Malassay appears to refer t ...

, elite infantry of the Adal Sultanate

The Adal Sultanate, or the Adal Empire or the ʿAdal or the Bar Saʿad dīn (alt. spelling ''Adel Sultanate, ''Adal ''Sultanate'') () was a medieval Sunni Muslim Empire which was located in the Horn of Africa. It was founded by Sabr ad-Din ...

References

Notes

Bibliography

* * Aksan, Virginia H. "Whatever Happened to the Janissaries? Mobilization for the 1768–1774 Russo-Ottoman War." ''War in History'' (1998) 5#1 pp: 23–36online

* * Benesch, Oleg. "Comparing Warrior Traditions: How the Janissaries and Samurai Maintained Their Status and Privileges During Centuries of Peace." ''Comparative Civilizations Review'' 55.55 (2006): 6:37-5

Online

* * Cleveland, William L. ''A History of the Modern Middle East'' (Boulder: Westview, 2004) * Goodwin, Godfrey (2001). ''The Janissaries''. UK: Saqi Books. ; anecdotal and not scholarly says Aksan (1998) * * * * Kitsikis, Dimitri, (1985, 1991, 1994). ''L'Empire ottoman''. Paris,: Presses Universitaires de France. * * * * Shaw, Stanford J. (1976). ''History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey'' (Vol. I). New York: Cambridge University Press. * Shaw, Stanford J. & Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977). ''History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey'' (Vol. II). New York: Cambridge University Press. *

External links