Yeshivat Lev Aharon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A yeshiva (; he, ישיבה, , sitting; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish

A yeshiva (; he, ישיבה, , sitting; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish

yeshiva

' is applied to the activity of learning in class, and hence to a learning "session." The transference in meaning of the term from the learning session to the institution itself appears to have occurred by the time of the Talmudic Academies in Babylonia,

The Geonic period takes its name from ''Gaon'', the title given to the heads of the three yeshivas which existed from the third to the thirteenth century. The Geonim acted as the principals of their individual yeshivot, and as spiritual leaders and high judges for the wider communities tied to them. The yeshiva conducted all official business in the name of its Gaon, and all correspondence to or from the yeshiva was addressed directly to the Gaon.

Throughout the Geonic Period there were three yeshivot, each named for the cities in which they were located: Jerusalem,

The Geonic period takes its name from ''Gaon'', the title given to the heads of the three yeshivas which existed from the third to the thirteenth century. The Geonim acted as the principals of their individual yeshivot, and as spiritual leaders and high judges for the wider communities tied to them. The yeshiva conducted all official business in the name of its Gaon, and all correspondence to or from the yeshiva was addressed directly to the Gaon.

Throughout the Geonic Period there were three yeshivot, each named for the cities in which they were located: Jerusalem,

Organised Torah study was revolutionised by Chaim Volozhin, an influential 18th-century Lithuanian leader of Judaism and disciple of the

Organised Torah study was revolutionised by Chaim Volozhin, an influential 18th-century Lithuanian leader of Judaism and disciple of the

With the success of the yeshiva institution in Lithuanian Jewry, the

With the success of the yeshiva institution in Lithuanian Jewry, the

Although the yeshiva as an institution is in some ways a continuation of the Talmudic Academies in Babylonia, large scale educational institutions of this kind were not characteristic of the North African and Middle Eastern Sephardi Jewish world in pre-modern times: education typically took place in a more informal setting in the synagogue or in the entourage of a famous rabbi. In medieval Spain, and immediately following the expulsion in 1492, there were some schools which combined Jewish studies with sciences such as logic and astronomy, similar to the contemporary Islamic madrasas. In 19th century Jerusalem, a college was typically an endowment for supporting ten adult scholars rather than an educational institution in the modern sense; towards the end of the century a school for orphans was founded providing for some rabbinic studies. Early educational institutions on the European model were

Although the yeshiva as an institution is in some ways a continuation of the Talmudic Academies in Babylonia, large scale educational institutions of this kind were not characteristic of the North African and Middle Eastern Sephardi Jewish world in pre-modern times: education typically took place in a more informal setting in the synagogue or in the entourage of a famous rabbi. In medieval Spain, and immediately following the expulsion in 1492, there were some schools which combined Jewish studies with sciences such as logic and astronomy, similar to the contemporary Islamic madrasas. In 19th century Jerusalem, a college was typically an endowment for supporting ten adult scholars rather than an educational institution in the modern sense; towards the end of the century a school for orphans was founded providing for some rabbinic studies. Early educational institutions on the European model were

In 1854, the Jewish Theological Seminary of Breslau was founded. It was headed by

In 1854, the Jewish Theological Seminary of Breslau was founded. It was headed by

World War II and the Holocaust ended the yeshivot of Eastern and Central Europe – however many scholars and rabbinic students who survived the war, established yeshivot in a number of Western countries which had no or few yeshivot. (The

World War II and the Holocaust ended the yeshivot of Eastern and Central Europe – however many scholars and rabbinic students who survived the war, established yeshivot in a number of Western countries which had no or few yeshivot. (The

jewishvirtuallibrary.org the greatest number of yeshivot, and the most important were centered in Israel and in the United States; but they were also found in many other Western countries, prominent examples being Gateshead Yeshiva in England (one of the descendants of Novardok) and the Yeshiva of Aix-les-Bains, France. The Chabad movement was particularly active in this direction, establishing yeshivot also in France, North Africa, Australia, and South Africa; this "network of institutions" is known as '' Tomchei Temimim''. Many prominent contemporary yeshivot in the United States and Israel are continuations of European institutions, and often bear the same name.

The first Orthodox yeshiva in the United States was Etz Chaim of

The first Orthodox yeshiva in the United States was Etz Chaim of

Yeshiva study is differentiated from, for example university study, by several features, apart from the curriculum. The year is structured into "''zmanim''"; the day is structured into "''seders''". The learning itself is delivered through a "''shiur''", a discursive-lecture with pre-specified sources, or "''marei mekomot''" (מראה מקומות; “bibliography”, lit. "indication of the (textual) locations");Example ''marei mekomot'' - Halacha

Yeshiva study is differentiated from, for example university study, by several features, apart from the curriculum. The year is structured into "''zmanim''"; the day is structured into "''seders''". The learning itself is delivered through a "''shiur''", a discursive-lecture with pre-specified sources, or "''marei mekomot''" (מראה מקומות; “bibliography”, lit. "indication of the (textual) locations");Example ''marei mekomot'' - Halacha

/ref>Example ''marei mekomot'' - Gemara

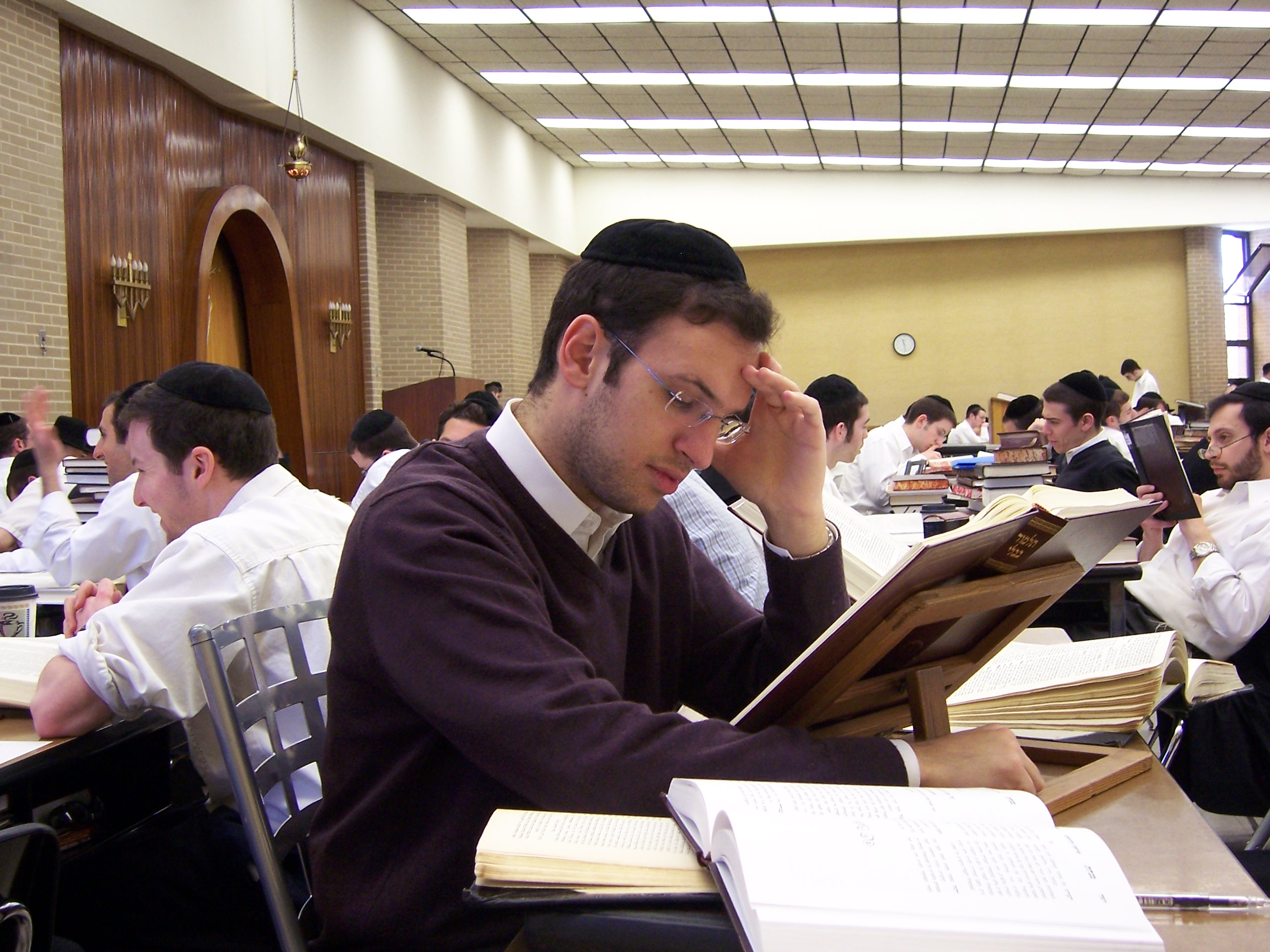

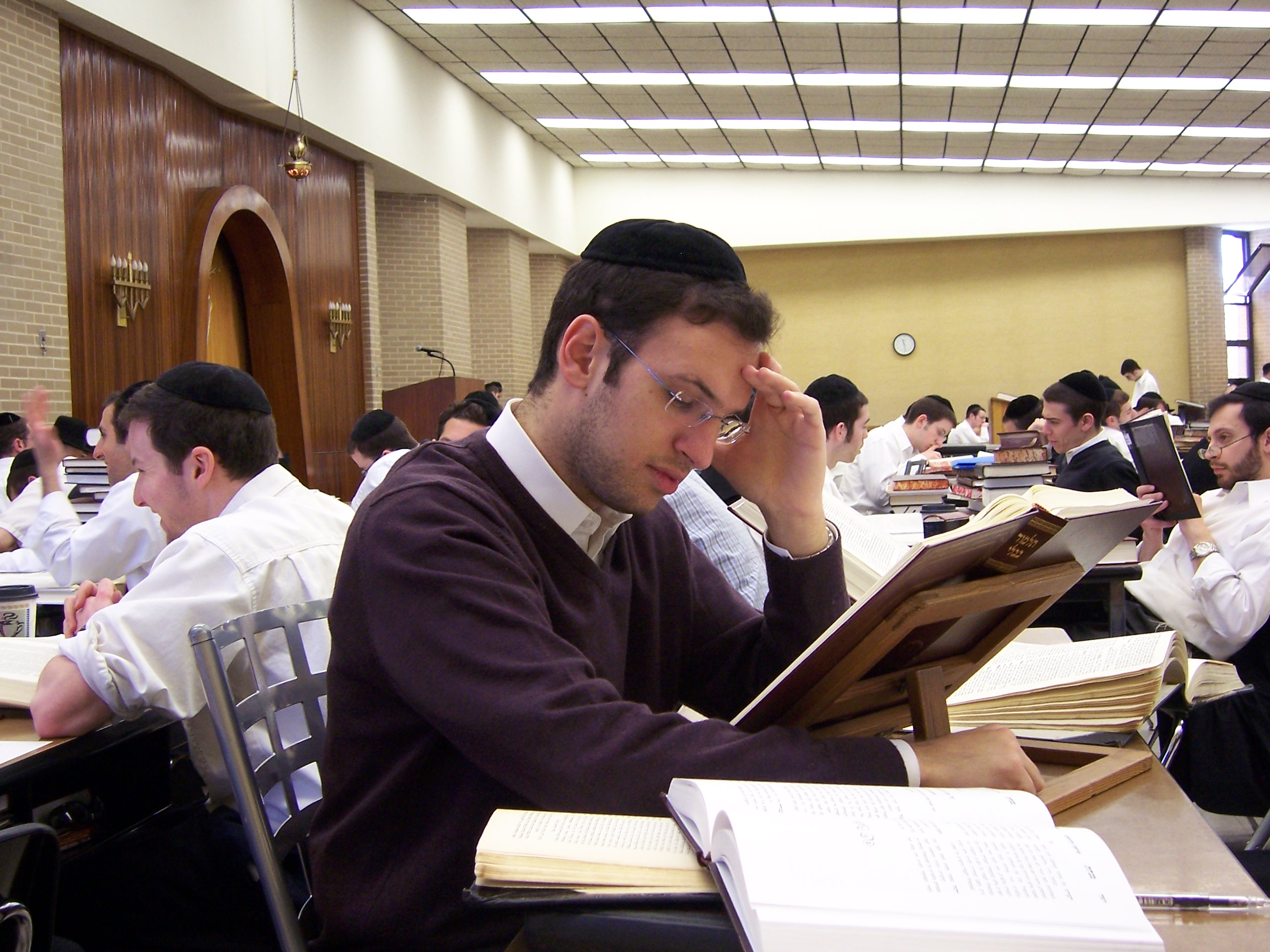

/ref> study in general, and particularly the preparation for ''shiur'', takes place in "" or paired-study. This study is in a common venue called the '' bet midrash'' (

# Yeshiva Ketana (junior yeshiva) or "Talmud Torah" – Many Haredi (non-Hasidic and Hasidic) yeshivot ketanot in Israel, and some (primarily Hasidic) in the Diaspora, do not have a secular course of studies, with all students learning Judaic Torah studies full-time.

# Yeshiva High School – also called ''

# Yeshiva Ketana (junior yeshiva) or "Talmud Torah" – Many Haredi (non-Hasidic and Hasidic) yeshivot ketanot in Israel, and some (primarily Hasidic) in the Diaspora, do not have a secular course of studies, with all students learning Judaic Torah studies full-time.

# Yeshiva High School – also called ''

science.co.il and not a yeshiva. (Although there are exceptions such as Prospect Park Yeshiva.) The Haredi Bais Yaakov system was started in 1918 under the guidance of Sarah Schenirer. These institutions provide girls with a Torah education, using a curriculum that skews more toward practical ''halakha'' (Jewish law) and the study of Tanakh, rather than Talmud. The curriculum at Religious Zionist and Modern Orthodox ''midrashot'', however, often includes some study of Talmud: often Mishnah, sometimes ''Gemara''; in further distinction, curricula generally entail ''chavruta''-based study of the texts of Jewish philosophy, and likewise Tanakh is studied with commentaries. See for further discussion.

"Ordination and Semicha"

jsli.net Conservative Yeshivot occupy a position midway, in that their training places (significantly) more emphasis on Halakha and Talmud than other non-Orthodox programs; see Conservative halakha. The sections below discuss the Orthodox approach - but may be seen as overviews of the traditional-content; see also re the various approaches under

In a typical Orthodox yeshiva, the main emphasis is on Talmud study and analysis, or ''

In a typical Orthodox yeshiva, the main emphasis is on Talmud study and analysis, or ''

Rabbinical College

Talmudic University of Florida. Catalog

Central Yeshiva Tomchei Tmimim Lubavitz Sometimes tractates dealing with an upcoming

''Kuntres Eitz HaChayim'' ch 28

for discussion of the interrelation between Rashi and Tosfot The integration of Talmud, Rashi and Tosafot, is considered as foundational – and prerequisite – to further analysis See for example the guidelines for Talmud study authored by

''Kuntres Eitz HaChayim'' ch 28

/ref> Through this, the study builds and deepens the concepts and principles arising from the tractate. Throughout, an important simultaneous requirement is that the "simple interpretation" of the underlying ''sugyas'' must maintain. * Many Yeshivot proceed ''aliba dehilchasa''See the Hebrew article :he: אסוקי שמעתתא אליבא דהלכתא for detail and discussion. (אליבא דהלכתא, Seph. pronunciation, ''dehilchata''; lit. "according to the Law"), where the learning focuses more on the Halachik-rules that develop from the ''sugya'', delineating how the opinions of the rishonim and acharonim relate to practice. There are two sub-approaches: The first, often the approach taken at Sephardic Yeshivot, analyzes the ''sugya'' as the source of the ''halacha'', understanding how it inheres in each ''rishon'', and is undertaken even for topics with limited application (prototypical are ''

ch 5:21

as a guideline; where Mishna-study begins at age 10, and ''Gemara'' at 15. See

Rabbinical College of America ''Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary - Semikhah Requirements''

/ref> invariably covers

Rabbinical Council of America Executive Committee, 2015. having spent at least four preceding years in Yeshiva; Kollel students likewise. (See and .) During the morning ''seder'', Semikha students continue their Talmud studies, learning the same ''masechet'' as the rest of the Yeshiva.

Haredi ''Yeshivot'' typically devote a ''seder'' to ''mussar'' (ethics and character development). The preeminent text studied is the '' Mesillat Yesharim'' ("Path of the Just") of Moshe Chaim Luzzatto. Other works of

Haredi ''Yeshivot'' typically devote a ''seder'' to ''mussar'' (ethics and character development). The preeminent text studied is the '' Mesillat Yesharim'' ("Path of the Just") of Moshe Chaim Luzzatto. Other works of

Topics in Hashkafa

at Har Etzion

Shiurim in Machsahava

at Yeshiva University (yutorah.org)

Hashkafa courses

at

Intensive study of ''Chumash'' (Torah) with the commentary of Rashi is stressed and taught in all elementary grades. In Haredi and Hasidic yeshivas, this is often done with Yiddish translations. The rest of the Tanach (Hebrew Bible; acronym: ''"Torah, Nevi'im u' Ketuvim"''; "Torah, Prophets and Writings") is usually taught through high school, although less intensively.

In Yeshivot, thereafter, ''Chumash'', and especially '' Nach'', are studied less directly. Yeshiva students typically follow the practice of '' Shnayim mikra ve-echad targum'', independently studying the upcoming ''

Intensive study of ''Chumash'' (Torah) with the commentary of Rashi is stressed and taught in all elementary grades. In Haredi and Hasidic yeshivas, this is often done with Yiddish translations. The rest of the Tanach (Hebrew Bible; acronym: ''"Torah, Nevi'im u' Ketuvim"''; "Torah, Prophets and Writings") is usually taught through high school, although less intensively.

In Yeshivot, thereafter, ''Chumash'', and especially '' Nach'', are studied less directly. Yeshiva students typically follow the practice of '' Shnayim mikra ve-echad targum'', independently studying the upcoming ''

A yeshiva (; he, ישיבה, , sitting; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish

A yeshiva (; he, ישיבה, , sitting; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish educational institution

An educational institution is a place where people of different ages gain an education, including preschools, childcare, primary-elementary schools, secondary-high schools, and universities. They provide a large variety of learning environments an ...

focused on the study of Rabbinic literature, primarily the Talmud and halacha (Jewish law), while Torah and Jewish philosophy

Jewish philosophy () includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. Until modern ''Haskalah'' (Jewish Enlightenment) and Jewish emancipation, Jewish philosophy was preoccupied with attempts to reconcile ...

are studied in parallel. The studying is usually done through daily ''shiurim

Shiur (, , lit. ''amount'', pl. shiurim ) is a lecture on any Torah topic, such as Gemara, Mishnah, Halakha (Jewish law), Tanakh (Bible), etc.

History

The Hebrew term שיעור ("designated amount") came to refer to a portion of Ju ...

'' (lectures or classes) as well as in study pairs called ''chavrusa

''Chavrusa'', also spelled ''chavruta'' or ''ḥavruta'' (Aramaic: חַבְרוּתָא, lit. "fellowship" or "group of fellows"; pl. חַבְרָוָותָא), is a traditional rabbinic approach to Talmudic study in which a small group of stud ...

s'' ( Aramaic for 'friendship' or 'companionship'). ''Chavrusa''-style learning is one of the unique features of the yeshiva.

In the United States and Israel, different levels of yeshiva education have different names. In the United States, elementary-school students enroll in a ''cheder'', post- bar mitzvah-age students learn in a '' metivta'', and undergraduate-level students learn in a '' beit midrash'' or ''yeshiva gedola'' ( he, ישיבה גדולה, , large yeshiva' or 'great yeshiva). In Israel, elementary-school students enroll in a '' Talmud Torah'' or '' cheder'', post-bar mitzvah-age students learn in a ''yeshiva ketana'' ( he, ישיבה קטנה, , small yeshiva' or 'minor yeshiva), and high-school-age students learn in a ''yeshiva gedola''. A kollel is a yeshiva for married men, in which it is common to pay a token stipend to its students. Students of Lithuanian

Lithuanian may refer to:

* Lithuanians

* Lithuanian language

* The country of Lithuania

* Grand Duchy of Lithuania

* Culture of Lithuania

* Lithuanian cuisine

* Lithuanian Jews as often called "Lithuanians" (''Lita'im'' or ''Litvaks'') by other Jew ...

and Hasidic

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism (Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of contem ...

yeshivot gedolot (plural of yeshiva gedola) usually learn in yeshiva until they get married.

Historically, yeshivas were for men only. Today, all non-Orthodox yeshivas are open to females. Although there are separate schools for Orthodox women and girls, ('' midrasha'' or "seminary") these do not follow the same structure or curriculum as the traditional yeshiva for boys and men.

Etymology

Alternate spellings and names include ''yeshivah'' (; he, ישיבה, sitting (n.); ''metivta'' and ''mesivta

''Mesivta'' (also metivta; Aramaic: מתיבתא, "academy") is an Orthodox Jewish yeshiva secondary school for boys. The term is commonly used in the United States to describe a yeshiva that emphasizes Talmudic studies for boys in grades ...

'' ( arc, מתיבתא ''methivta''); ''beth midrash

A ''beth midrash'' ( he, בית מדרש, or ''beis medrash'', ''beit midrash'', pl. ''batei midrash'' "House of Learning") is a hall dedicated for Torah study, often translated as a "study hall." It is distinct from a synagogue (''beth kness ...

''; Talmudical academy, rabbinical academy and rabbinical school. The word yeshiva

' is applied to the activity of learning in class, and hence to a learning "session." The transference in meaning of the term from the learning session to the institution itself appears to have occurred by the time of the Talmudic Academies in Babylonia,

Sura

A ''surah'' (; ar, سورة, sūrah, , ), is the equivalent of "chapter" in the Qur'an. There are 114 ''surahs'' in the Quran, each divided into '' ayats'' (verses). The chapters or ''surahs'' are of unequal length; the shortest surah ('' Al-K ...

and Pumbedita

Pumbedita (sometimes Pumbeditha, Pumpedita, or Pumbedisa; arc, פוּמְבְּדִיתָא ''Pūmbəḏīṯāʾ'', "The Mouth of the River,") was an ancient city located near the modern-day city of Fallujah, Iraq. It is known for having hosted t ...

, which were known as ''shte ha-yeshivot'' (the two colleges).

History

Origins

The Mishnah tractateMegillah

Megillah ( he, מגילה, scroll) may refer to:

Bible

*The Book of Esther (''Megillat Esther''), read on the Jewish holiday of Purim

*The Five Megillot

*Megillat Antiochus

Rabbinic literature

*Tractate Megillah in the Talmud.

*Megillat Taanit, ...

contains the law that a town can only be called a "city" if it supports ten men (''batlanim'') to make up the required quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a deliberative assembly (a body that uses parliamentary procedure, such as a legislature) necessary to conduct the business of that group. According to ''Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised'', the ...

for communal prayers. Similarly, every beth din ("house of judgement") was attended by a number of pupils up to three times the size of the court ( Mishnah, tractate Sanhedrin). According to the Talmud, adults generally took two months off every year to study. These being Elul and Adar

Adar ( he, אֲדָר ; from Akkadian ''adaru'') is the sixth month of the civil year and the twelfth month of the religious year on the Hebrew calendar, roughly corresponding to the month of March in the Gregorian calendar. It is a month of 29 d ...

the months preceding the pilgrimage festivals

The Three Pilgrimage Festivals, in Hebrew ''Shalosh Regalim'' (שלוש רגלים), are three major festivals in Judaism—Pesach (''Passover''), Shavuot (''Weeks'' or ''Pentecost''), and Sukkot (''Tabernacles'', ''Tents'' or ''Booths'')—when ...

of Sukkot

or ("Booths, Tabernacles")

, observedby = Jews, Samaritans, a few Protestant denominations, Messianic Jews, Semitic Neopagans

, type = Jewish, Samaritan

, begins = 15th day of Tishrei

, ends = 21st day of Tishre ...

and Pesach, called ''Yarḥei Kalla'' ( Aramaic for " Months of Kallah"). The rest of the year, they worked.

Geonic Period

The Geonic period takes its name from ''Gaon'', the title given to the heads of the three yeshivas which existed from the third to the thirteenth century. The Geonim acted as the principals of their individual yeshivot, and as spiritual leaders and high judges for the wider communities tied to them. The yeshiva conducted all official business in the name of its Gaon, and all correspondence to or from the yeshiva was addressed directly to the Gaon.

Throughout the Geonic Period there were three yeshivot, each named for the cities in which they were located: Jerusalem,

The Geonic period takes its name from ''Gaon'', the title given to the heads of the three yeshivas which existed from the third to the thirteenth century. The Geonim acted as the principals of their individual yeshivot, and as spiritual leaders and high judges for the wider communities tied to them. The yeshiva conducted all official business in the name of its Gaon, and all correspondence to or from the yeshiva was addressed directly to the Gaon.

Throughout the Geonic Period there were three yeshivot, each named for the cities in which they were located: Jerusalem, Sura

A ''surah'' (; ar, سورة, sūrah, , ), is the equivalent of "chapter" in the Qur'an. There are 114 ''surahs'' in the Quran, each divided into '' ayats'' (verses). The chapters or ''surahs'' are of unequal length; the shortest surah ('' Al-K ...

, and Pumbedita

Pumbedita (sometimes Pumbeditha, Pumpedita, or Pumbedisa; arc, פוּמְבְּדִיתָא ''Pūmbəḏīṯāʾ'', "The Mouth of the River,") was an ancient city located near the modern-day city of Fallujah, Iraq. It is known for having hosted t ...

; the yeshiva of Jerusalem would later relocate to Cairo, and the yeshivot of Sura and Pumbedita to Baghdad, but retain their original names. Each Jewish community would associate itself with one of the three yeshivot; Jews living around the Mediterranean typically followed the yeshiva in Jerusalem, while those living in the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate ...

and modern-day Iraq and Iran typically followed one of the two yeshivot in Baghdad. There was however, no requirement for this, and each community could choose to associate with any of the yeshivot.

The yeshiva served as the highest educational institution for the Rabbis of this period. In addition to this, the yeshiva wielded great power as the principal body for interpreting Jewish law

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Judaism, Jewish religious laws which is derived from the Torah, written and Oral Tora ...

. The community regarded the Gaon of a yeshiva as the highest judge on all matters of Jewish law. Each yeshiva ruled differently on matters of ritual and law; the other yeshivot accepted these divisions, and all three ranked as equally orthodox. The yeshiva also served as an administrative authority, in conjunction with local communities, by appointing members to serve as the head of local congregations. These heads of a congregation served as a link between the congregation and the larger yeshiva it was attached to. These leaders would also submit questions to the yeshiva to obtain final rulings on issues of dogma, ritual, or law. Each congregation was expected to follow only one yeshiva to prevent conflict with different rulings issued by different yeshivot.

The yeshivot were financially supported by a number of means, including fixed voluntary, annual contributions; these contributions being collected and handled by local leaders appointed by the yeshiva. Private gifts and donations from individuals were also common, especially during holidays, consisting of money or goods.

The yeshiva of Jerusalem was finally forced into exile in Cairo in 1127, and eventually dispersed entirely. Likewise, the yeshivot of Sura and Pumbedita were dispersed following the Mongol invasions of the 13th century. After this education in Jewish religious studies became the responsibility of individual synagogues. No organization ever came to replace the three great yeshivot of Jerusalem, Sura and Pumbedita.

Post-Geonic Period to the 19th century

After the Geonic Period Jews established more Yeshiva academies in Europe and in Northern Africa, including the Kairuan yeshiva in Tunisia (Hebrew: ישיבת קאירואן) that was established by Chushiel Ben Elchanan (Hebrew: חושיאל בן אלחנן) in 974. Traditionally, every townrabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as '' semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form o ...

had the right to maintain a number of full or part-time pupils in the town's beth midrash

A ''beth midrash'' ( he, בית מדרש, or ''beis medrash'', ''beit midrash'', pl. ''batei midrash'' "House of Learning") is a hall dedicated for Torah study, often translated as a "study hall." It is distinct from a synagogue (''beth kness ...

(study hall), which was usually adjacent to the synagogue. Their cost of living was covered by community taxation. After a number of years, the students who received ''semikha

Semikhah ( he, סמיכה) is the traditional Jewish name for rabbinic ordination.

The original ''semikhah'' was the formal "transmission of authority" from Moses through the generations. This form of ''semikhah'' ceased between 360 and 425 C ...

'' (rabbinical ordination) would either take up a vacant rabbinical position elsewhere or join the workforce.

Lithuanian yeshivas

Vilna Gaon

Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, ( he , ר' אליהו בן שלמה זלמן ''Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman'') known as the Vilna Gaon (Yiddish: דער װילנער גאון ''Der Vilner Gaon'', pl, Gaon z Wilna, lt, Vilniaus Gaonas) or Elijah of ...

. In his view, the traditional arrangement did not cater to those looking for more intensive study.

With the support of his teacher, Volozhin gathered interested students and started a yeshiva in the town of Valozhyn, located in modern-day Belarus. The Volozhin yeshiva was closed some 60 years later in 1892 following the Russian government's demands for the introduction of certain secular studies. Thereafter, a number of yeshivot opened in other towns and cities, most notably Slabodka, Panevėžys, Mir, Brisk, and Telz. Many prominent contemporary ''yeshivot'' in the United States and Israel are continuations of these institutions, and often bear the same name.

In the 19th century, Israel Salanter

Yisrael ben Ze'ev Wolf Lipkin, also known as "Israel Salanter" or "Yisroel Salanter" (November 3, 1809, Zhagory – February 2, 1883, Königsberg), was the father of the Musar movement in Orthodox Judaism and a famed Rosh yeshiva and Talmudist. T ...

initiated the Mussar movement in non-Hasidic Lithuanian Jewry, which sought to encourage yeshiva students and the wider community to spend regular times devoted to the study of Jewish ethical works. Concerned by the new social and religious changes of the Haskalah (the Jewish Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

), and other emerging political ideologies (such as Zionism) that often opposed traditional Judaism, the masters of Mussar saw a need to augment Talmudic study with more personal works. These comprised earlier classic Jewish ethical texts (mussar literature

Musar literature is didactic Jewish ethical literature which describes virtues and vices and the path towards character improvement. This literature gives the name to the Musar movement, in 19th century Lithuania, but this article considers such l ...

), as well as a new literature for the movement. After early opposition, the Lithuanian yeshiva world saw the need for this new component in their curriculum, and set aside times for individual mussar study and mussar talks ("mussar shmues"). A '' mashgiach ruchani'' (spiritual mentor) encouraged the personal development of each student. To some degree, this Lithuanian movement arose in response, and as an alternative, to the separate mystical study of the Hasidic Judaism world. Hasidism began in the previous century within traditional Jewish life in Ukraine, and spread to Hungary, Poland and Russia. As the 19th century brought upheavals and threats to traditional Judaism, the Mussar teachers saw the benefit of the new spiritual focus in Hasidism, and developed their alternative ethical approach to spirituality.

Some variety developed within Lithuanian yeshivas to methods of studying Talmud and ''mussar'', for example whether the emphasis would be placed on ''beki'ut'' (breadth) or ''iyyun'' (depth). '' Pilpul'', a type of in-depth analytical and casuistic argumentation popular from the 16th to 18th centuries that was traditionally reserved for investigative Talmudic study, was not always given a place. The new analytical approach of the Brisker method, developed by Chaim Soloveitchik

Chaim (Halevi) Soloveitchik (Yiddish: חיים סאָלאָווייטשיק, pl, Chaim Sołowiejczyk), also known as Reb Chaim Brisker (1853 – 30 July 1918), was a rabbi and Talmudic scholar credited as the founder of the popular Brisker appr ...

, has become widely popular; however, there are other approaches such as those of Mir, Chofetz Chaim, and Telz. In ''mussar'', different schools developed, such as Slabodka and Novhardok, though today, a decline in devoted spiritual self-development from its earlier intensity has to some extent levelled out the differences.

Hasidic yeshivas

With the success of the yeshiva institution in Lithuanian Jewry, the

With the success of the yeshiva institution in Lithuanian Jewry, the Hasidic

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism (Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of contem ...

world developed their own yeshivas, in their areas of Eastern Europe. These comprised the traditional Jewish focus on Talmudic literature that is central to Rabbinic Judaism, augmented by study of Hasidic philosophy (Hasidism). Examples of these Hasidic yeshivas are the Chabad Lubavitch yeshiva system of Tomchei Temimim, founded by Sholom Dovber Schneersohn

Sholom Dovber Schneersohn ( he, שלום דובער שניאורסאהן) was the fifth Rebbe (spiritual leader) of the Chabad Lubavitch chasidic movement. He is known as "the Rebbe Rashab" (for Reb Sholom Ber). His teachings represent the emerge ...

in Russia in 1897, and the Chachmei Lublin Yeshiva established in Poland in 1930 by Meir Shapiro

Yehuda Meir Shapiro ( pl, Majer Jehuda Szapira; March 3, 1887 – October 27, 1933), was a prominent Polish Hasidic rabbi and rosh yeshiva, also known as the Lubliner Rav. He is noted for his promotion of the Daf Yomi study program in 1923, a ...

, who is renowned in both Hasidic and Lithuanian Jewish circles for initiating the Daf Yomi daily cycle of Talmud study.

(For contemporary ''yeshivas'', see, for example, under Satmar, Belz

Belz ( uk, Белз; pl, Bełz; yi, בעלז ') is a small city in Lviv Oblast of Western Ukraine, near the border with Poland, located between the Solokiya river (a tributary of the Bug River) and the Richytsia stream. Belz hosts the administ ...

, Bobov, Breslov and Pupa.)

In many Hasidic ''yeshivas'', study of Hasidic texts is a secondary activity, similar to the additional mussar curriculum in Lithuanian yeshivas. These paths see Hasidism as a means to the end of inspiring emotional '' devekut'' (spiritual attachment to God) and mystical enthusiasm. In this context, the personal pilgrimage of a Hasid to his Rebbe is a central feature of spiritual life, in order to awaken spiritual fervour. Often, such paths will reserve the Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; he, שַׁבָּת, Šabbāṯ, , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the week—i.e., Saturday. On this day, religious Jews remember the biblical storie ...

in the yeshiva for the sweeter teachings of the classic texts of Hasidism.

In contrast, Chabad and Breslov, in their different ways, place daily study of their dynasties' Hasidic texts in central focus; see below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

*Bottom (disambiguation)

Bottom may refer to:

Anatomy and sex

* Bottom (BDSM), the partner in a BDSM who takes the passive, receiving, or obedient role, to that of the top or ...

. Illustrative of this is Sholom Dovber Schneersohn's wish in establishing the Chabad yeshiva system, that the students should spend a part of the daily curriculum learning Chabad Hasidic texts "with ''pilpul''". The idea to learn Hasidic mystical texts with similar logical profundity, derives from the unique approach in the works of the Rebbes of Chabad, initiated by its founder Schneur Zalman of Liadi

Shneur Zalman of Liadi ( he, שניאור זלמן מליאדי, September 4, 1745 – December 15, 1812 Adoption of the Gregorian calendar#Adoption in Eastern Europe, O.S. / 18 Elul 5505 – 24 Tevet 5573) was an influential Lithuanian Jews, Li ...

, to systematically investigate and articulate the "Torah of the Baal Shem Tov" in intellectual forms. Further illustrative of this is the differentiation in Chabad thought (such as the "Tract on Ecstasy" by Dovber Schneuri) between general Hasidism's emphasis on emotional enthusiasm and the Chabad ideal of intellectually reserved ecstasy. In the Breslov movement, in contrast, the daily study of works from the imaginative, creative radicalism of Nachman of Breslov awakens the necessary soulfulness with which to approach other Jewish study and observance.

Sephardi yeshivas

:''See: :Sephardic yeshivas, as well the more complete, קטגוריה:ישיבות ספרדיות''

Midrash Bet Zilkha

Midrash Bet Zilkha (or Midrash Abu Menashi) was an important Bet Midrash in Baghdad which was renowned among Eastern Jewry from the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries. Many of the great Babylonian rabbis of modern times arose from its halls, and rabbi ...

founded in 1870s Iraq and Porat Yosef Yeshiva founded in Jerusalem in 1914. Also notable is the Bet El yeshiva founded in 1737 in Jerusalem for advanced Kabbalistic studies. Later Sephardic yeshivot are usually on the model either of Porat Yosef or of the Ashkenazi institutions.

The Sephardic world has traditionally placed the study of Kabbalah (esoteric Jewish mysticism) in a more mainstream position than in the European Ashkenazi

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

world. This difference of emphasis arose as a result of the Sabbatean heresy in the 17th century, that suppressed widespread study of Kabbalah in Europe in favour of Rabbinic Talmudic study. In Eastern European Lithuanian life, Kabbalah was reserved for an intellectual elite, while the mystical revival of Hasidism articulated Kabbalistic theology through Hasidic thought. These factors did not affect the Sephardi Jewish world, which retained a wider connection to Kabbalah in its traditionally observant communities. With the establishment of Sephardi yeshivas in Israel after the immigration of the Arabic Jewish communities there, some Sephardi yeshivas incorporated study of more accessible Kabbalistic texts into their curriculum. Nonetheless, the European prescriptions to reserve advanced Kabbalistic study to mature and elite students also influence the choice of texts in such yeshivas.

19th century to present

Conservative movement yeshivas

Zecharias Frankel

Zecharias Frankel, also known as Zacharias Frankel (30 September 1801 – 13 February 1875) was a Bohemian-German rabbi and a historian who studied the historical development of Judaism. He was born in Prague and died in Breslau. He was the foun ...

, and was viewed as the first educational institution associated with "positive-historical Judaism", the predecessor of Conservative Judaism

Conservative Judaism, known as Masorti Judaism outside North America, is a Jewish religious movement which regards the authority of ''halakha'' (Jewish law) and traditions as coming primarily from its people and community through the generatio ...

. In subsequent years, Conservative Judaism established a number of other institutions of higher learning (such as the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

The Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS) is a Conservative Jewish education organization in New York City, New York. It is one of the academic and spiritual centers of Conservative Judaism and a major center for academic scholarship in Jewish studie ...

in New York City) that emulate the style of traditional yeshivas in significant ways. However, many do not officially refer to themselves as "yeshivas" (one exception is the Conservative Yeshiva

The Conservative Yeshiva is a co-educational institute for study of traditional Judaism, Jewish texts in Jerusalem. The yeshiva was founded in 1995, and is under the

academic auspices of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America.

The current R ...

in Jerusalem), and all are open to both women and men, who study in the same classrooms and follow the same curriculum. Students may study part-time, as in a kollel, or full-time, and they may study ''lishmah'' (for the sake of studying itself) or towards earning rabbinic ordination.

Nondenominational or mixed yeshivas

Non-denominational yeshivas and kollels with connections to Conservative Judaism includeYeshivat Hadar

Yeshivat Hadar is a traditional egalitarian yeshiva on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The Yeshiva offers both summer and year-long fellowships for students to learn full-time in the yeshiva setting. Prominent rabbis associated with the Yeshiva i ...

in New York, the leaders of whom include Rabbinical Assembly members Elie Kaunfer and Shai Held Shai Held (born July 2, 1971) is a rosh yeshiva (Rabbinic dean) and Chair in Jewish Thought at Mechon Hadar.

He founded Mechon Hadar in 2006 with Rabbis Elie Kaunfer and Ethan Tucker.

Education

Held attended Ramaz High School and studied ...

. The rabbinical school of the Academy for Jewish Religion in California (AJR-CA) is led by Conservative rabbi Mel Gottlieb. The faculty of the Academy for Jewish Religion in New York

The Academy for Jewish Religion (AJR) is a rabbinical school in Yonkers, New York.

History

The Academy for Jewish Religion was founded in 1956 as a rabbinical school. Initially called the Academy for Liberal Judaism (and then the Academy for Highe ...

and of the Rabbinical School of Hebrew College in Newton Centre, Massachusetts also includes many Conservative rabbis.

See also Institute of Traditional Judaism.

More recently, several non-traditional, and nondenominational (also called "transdenominational" or "postdenominational") seminaries have been established. These grant semikha in a shorter time, and with a modified curriculum, generally focusing on leadership and pastoral roles. These are JSLI, RSI, PRS and Ateret Tzvi. The Wolkowisk Mesifta is aimed at community professionals with significant knowledge and experience, and provides a tailored program to each candidate.

Rimmon, the most recently established, emphasizes halakhic decision making.

See under for further discussion.

Reform and Reconstructionist seminaries

Hebrew Union College

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

(HUC), affiliated with Reform Judaism, was founded in 1875 under the leadership of Isaac Mayer Wise

Isaac Mayer Wise (29 March 1819, Lomnička – 26 March 1900, Cincinnati) was an American Reform rabbi, editor, and author. At his death he was called "the foremost rabbi in America".

Early life

Wise was born on 29 March 1819 in Steingrub in B ...

in Cincinnati, Ohio. HUC later opened additional locations in New York, Los Angeles, and Jerusalem. It is a rabbinical seminary or college mostly geared for the training of rabbis and clergy specifically. Similarly, the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College of Reconstructionist Judaism

Reconstructionist Judaism is a Jewish movement that views Judaism as a progressively evolving civilization rather than a religion, based on concepts developed by Mordecai Kaplan (1881–1983). The movement originated as a semi-organized stream wi ...

, founded in Pennsylvania in 1968, functions to train its future clergy. Some Reform and Reconstructionist teachers also teach at the non-denominational seminaries mentioned above. In Europe, Reform Judaism trains rabbis at Leo Baeck College in London, UK and Abraham Geiger Kolleg in Potsdam, Germany. None of these institutions describes itself as a "yeshiva".

Contemporary Orthodox yeshivas

World War II and the Holocaust ended the yeshivot of Eastern and Central Europe – however many scholars and rabbinic students who survived the war, established yeshivot in a number of Western countries which had no or few yeshivot. (The

World War II and the Holocaust ended the yeshivot of Eastern and Central Europe – however many scholars and rabbinic students who survived the war, established yeshivot in a number of Western countries which had no or few yeshivot. (The Yeshiva of Nitra

The Yeshiva of Nitra is a private Rabbinical college, or ''yeshiva'', located in Brooklyn, New York; it has campuses in Chester and Mount Kisco, New York.

Its origins lie in the Yeshiva of Nitra, Slovakia, established in 1907. The Yeshiva was ...

was the last surviving in occupied Europe. Many students and faculty of the Mir Yeshiva were able to escape to Siberia, with the Yeshiva ultimately continuing to operate in Shanghai.

See Yeshivas in World War II.)

From the mid-20th century"Yeshiva"jewishvirtuallibrary.org the greatest number of yeshivot, and the most important were centered in Israel and in the United States; but they were also found in many other Western countries, prominent examples being Gateshead Yeshiva in England (one of the descendants of Novardok) and the Yeshiva of Aix-les-Bains, France. The Chabad movement was particularly active in this direction, establishing yeshivot also in France, North Africa, Australia, and South Africa; this "network of institutions" is known as '' Tomchei Temimim''. Many prominent contemporary yeshivot in the United States and Israel are continuations of European institutions, and often bear the same name.

=Israel

= Yeshivot in Israel have operated since Talmudic times; seeTalmudic academies in Eretz Yisrael

The Talmudic Academies in Syria Palaestina were ''yeshivot'' that served as centers for Jewish scholarship and the development of Jewish law in Syria Palaestina (and later Palaestina Prima and Palaestina Secunda) between the destruction of the Se ...

.

Recent examples include the Ari Ashkenazi Synagogue

The Ashkenazi Ari Synagogue, located in Safed, Israel, was built in memory of Rabbi Isaac Luria (1534 - 1572), who was known by the Hebrew acronym "the ARI". It dates from the late 16th-century, it being constructed several years after the death ...

(since the mid 1500s); the Bet El yeshiva (operating since 1737); and Etz Chaim Yeshiva (since 1841).

Various yeshivot were established in Israel in the early 20th century: Shaar Hashamayim in 1906, Chabad's Toras Emes in 1911, Hebron Yeshiva in 1924, Sfas Emes

Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter ( he, יהודה אריה ליב אלתר, 15 April 1847 – 11 January 1905), also known by the title of his main work, the ''Sfas Emes'' (Ashkenazic Pronunciation) or ''Sefat Emet'' (Modern Hebrew), was a Hasidic rabbi ...

in 1925, Lomza in 1926.

After (and during) World War II, numerous other Haredi and Hasidic Yeshivot were re-established there by survivors. The Mir Yeshiva in Jerusalem – today the largest Yeshiva in the world – was established in 1944, by Rabbi Eliezer Yehuda Finkel Eliezer Yehuda Finkel may refer to one of the two rosh yeshivas of the Mir yeshivas:

* Eliezer Yehuda Finkel (born 1879) (1879–1965), also known as Reb Leizer Yudel, rosh yeshiva of the Mir yeshiva in Poland and Jerusalem

* Eliezer Yehuda Finke ...

who had traveled to Palestine to obtain visas for his students; Ponevezh similarly by Rabbi Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman; and Knesses Chizkiyahu in 1949.

The leading Sephardi Yeshiva, Porat Yosef, was founded in 1914; its predecessor, Yeshivat Ohel Moed was founded in 1904. From the 1940s and onward, especially following immigration of the Arabic Jewish communities, Sephardi leaders, such as Ovadia Yosef and Ben-Zion Meir Hai Uziel, established various yeshivot to facilitate Torah education for Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews (and alternative to Lithuanian yeshivot).

The Haredi community has grown with time – In 2016, 9% of Israel's population was Haredi, including Sephardic Haredim

Sephardic Haredim are Jews of Sephardi and Mizrahi descent who are adherents of Haredi Judaism. Sephardic Haredim today constitute a significant stream of Haredi Judaism, alongside the Hasidim and Lita'im. An overwhelming majority of Sephardic ...

– supporting many yeshivot correspondingly (see ). Boys and girls here attend separate schools, and proceed to higher Torah study, in a yeshiva or seminary, respectively, starting anywhere between the ages of 13 and 18; see '' Chinuch Atzmai'' and '' Bais Yaakov''. A significant proportion of young men then remain in yeshiva until their marriage; thereafter many continue their Torah studies in a kollel. (In 2006, there were 80,000 in full-time learning .) Kollel studies usually focus on deep analysis of Talmud, and those Tractates not usually covered in the standard "undergraduate" program; see below. Some Kollels similarly focus on halacha in total, others specifically on those topics required for ''Semikha

Semikhah ( he, סמיכה) is the traditional Jewish name for rabbinic ordination.

The original ''semikhah'' was the formal "transmission of authority" from Moses through the generations. This form of ''semikhah'' ceased between 360 and 425 C ...

'' (Rabbinic ordination) or ''Dayanut'' (qualification as a Rabbinic Judge). The certification in question is often conferred by the Rosh Yeshiva.

Mercaz Harav, the foundational and leading Religious-Zionist yeshiva was established in 1924 by Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi

Chief Rabbi ( he, רב ראשי ''Rav Rashi'') is a title given in several countries to the recognized religious leader of that country's Jewish community, or to a rabbinic leader appointed by the local secular authorities. Since 1911, through a ...

Abraham Isaac Kook

Abraham Isaac Kook (; 7 September 1865 – 1 September 1935), known as Rav Kook, and also known by the acronym HaRaAYaH (), was an Orthodox rabbi, and the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine. He is considered to be one of ...

. Many in the Religious Zionist

Religious Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת דָּתִית, translit. ''Tziyonut Datit'') is an ideology that combines Zionism and Orthodox Judaism. Its adherents are also referred to as ''Dati Leumi'' ( "National Religious"), and in Israel, the ...

community today attend a Hesder yeshiva (discussed below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

*Bottom (disambiguation)

Bottom may refer to:

Anatomy and sex

* Bottom (BDSM), the partner in a BDSM who takes the passive, receiving, or obedient role, to that of the top or ...

) during their national service; these offer a kollel for Rabbinical students. (Students generally prepare for the ''Semikha'' test of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel; until his recent passing (2020) commonly for that of the posek R. Zalman Nechemia Goldberg.)

Training as a ''Dayan'' in this community is usually through ''Machon Ariel'' (''Machon Harry Fischel Harry Fischel Institute for Talmudic Research ("Machon Harry Fischel") is a Jewish theological institute in Jerusalem that specializes in training dayanim (religious court judges). The institute was founded in 1931 by the American philanthropist Ha ...

''), also founded by Rav Kook, or ''Kollel Eretz Hemda''. Women in this community, as above, study in a Midrasha. High school students study at ''Mamlachti dati'' schools, often associated with '' Bnei Akiva''. Bar Ilan University allows students to combine Yeshiva studies with university study; Jerusalem College of Technology similarly, which also offers a Haredi track; there are several colleges of education associated with Hesder and the ''Midrashot'' (these often offer specializations in ''Tanakh'' and ''Machshavah'' – see below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

*Bottom (disambiguation)

Bottom may refer to:

Anatomy and sex

* Bottom (BDSM), the partner in a BDSM who takes the passive, receiving, or obedient role, to that of the top or ...

).

See .

=United States

= The first Orthodox yeshiva in the United States was Etz Chaim of

The first Orthodox yeshiva in the United States was Etz Chaim of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

(1886), modeled after Volozhin. It developed into the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (1896; "RIETS") and eventually Yeshiva University in 1945. It was established in the wake of the immigration of Central and Eastern European Jews (1880s – 1924). Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem, founded in 1907, was led by Rabbi Moshe Feinstein from the 1940s through 1986; Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin, est 1904, was headed by Rabbi Yitzchok Hutner from 1943 to 1980. Many Hasidic dynasties have their main Yeshivot in America, typically established in the 1940s; the Central Lubavitcher Yeshiva has over 1000 students.

The postwar establishment of Ashkenazi yeshivot and ''kollelim'' parallels that in Israel; as does the educational pattern in the American Haredi community, although more obtain a secular education at the college level (see College credit

A credit is the recognition for having taken a course at school or university, used as measure if enough hours have been made for graduation.

University credits United States Credit hours

In a college or university in the United States, student ...

below). Beth Medrash Govoha in Lakewood Lakewood may refer to:

Places Australia

* Lakewood, Western Australia, an abandoned town in Western Australia

Canada

* Lakewood, Edmonton, Alberta

* Lakewood Suburban Centre, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

Philippines

* Lakewood, Zamboanga del S ...

, New Jersey with 3,000 students in the early 2000s was founded in 1943 by R. Aaron Kotler

Aharon Kotler (1892–1962) was an Orthodox Jewish rabbi and a prominent leader of Orthodox Judaism in Lithuania and the United States; the latter being where he founded Beth Medrash Govoha in Lakewood Township, New Jersey.

Early life

Kotler ...

on the "rigid Lithuanian model" that demanded full-time study; it now offers a Bachelor of Talmudic Law The Bachelor of Talmudic Law (BTL), Bachelor of Talmudic Studies (BTS) and First Talmudic Degree (FTD) are law degrees, comprising the study, analysis and application of ancient Talmudical, Biblical, and other historical sources. The laws derived fr ...

degree which allows students to go on to graduate school. The best known of the numerous Haredi yeshivas are, additional to "Lakewood", Telz, "Rabbinical Seminary of America", Ner Yisroel

Ner Israel Rabbinical College (ישיבת נר ישראל), also known as NIRC and Ner Yisroel, is a Haredi yeshiva (Jewish educational institution) in Pikesville, Maryland, Pikesville (Baltimore County, Maryland, Baltimore County), Maryland. I ...

, Chaim Berlin, and Hebrew Theological College; '' Yeshivish'' (i.e. satellite) communities often maintain a community kollel.

Many Hasidic sects have their own yeshivas - see especially Satmar and Bobov - while Chabad, as mentioned, operates its ''Tomchei Temimim'' nationwide.

Regarding junior and high school - of which there are over 600 combined - see Torah Umesorah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the sa ...

, Mesivta

''Mesivta'' (also metivta; Aramaic: מתיבתא, "academy") is an Orthodox Jewish yeshiva secondary school for boys. The term is commonly used in the United States to describe a yeshiva that emphasizes Talmudic studies for boys in grades ...

, and Bais Yaakov.

Modern Orthodox

Modern may refer to:

History

*Modern history

** Early Modern period

** Late Modern period

*** 18th century

*** 19th century

*** 20th century

** Contemporary history

* Moderns, a faction of Freemasonry that existed in the 18th century

Philosoph ...

typically spend a year, often two, post-high school in a yeshiva (sometimes Hesder) or ''Midrasha'' in Israel. Many thereafter, or instead, attend Yeshiva University, undertaking a dual curriculum, combining academic education with Torah study; see '' Torah Umadda'' and S. Daniel Abraham Israel Program. (A percentage stay in Israel, “making ''Aliyah

Aliyah (, ; he, עֲלִיָּה ''ʿălīyyā'', ) is the immigration of Jews from Jewish diaspora, the diaspora to, historically, the geographical Land of Israel, which is in the modern era chiefly represented by the Israel, State of Israel ...

''”; many also go on to higher education in other American colleges.) Semikha is usually through RIETS, although many Modern Orthodox

Modern may refer to:

History

*Modern history

** Early Modern period

** Late Modern period

*** 18th century

*** 19th century

*** 20th century

** Contemporary history

* Moderns, a faction of Freemasonry that existed in the 18th century

Philosoph ...

Rabbis study through '' Hesder'', or other Yeshivot in Israel such as Yeshivat HaMivtar

Yeshivat Torat Yosef - Hamivtar (ישיבת תורת יוסף - המבתר) is a men's yeshiva located in Efrat in the West Bank. The Roshei Yeshiva are Rabbi Yonatan Rosensweig and Rabbi Shlomo Riskin. The institution is primarily focused on post ...

, Mizrachi's ''Musmachim'' program, and Machon Ariel.

RIETS also houses several post-semikha kollelim, including one focused on ''Dayanut''. Dayanim also train through Kollel Eretz Hemda and Machon Ariel; while Mizrachi's post-semikha ''Manhigut Toranit'' program focuses on leadership and scholarship, with the advanced semikha of “Rav Ir”. Communities will often host a ''Torah MiTzion'' kollel, where '' Hesder'' graduates learn and teach, generally for one year.

There are numerous Modern Orthodox Jewish day schools

Modern may refer to:

History

* Modern history

** Early Modern period

** Late Modern period

*** 18th century

*** 19th century

*** 20th century

** Contemporary history

* Moderns, a faction of Freemasonry that existed in the 18th century

Phil ...

, typically offering a ''beit midrash'' / ''metivta'' program in parallel with the standard curriculum, (often) structured such that students are able to join the first ''shiur'' in an Israeli yeshiva.

The US educational pattern is to be found around the Jewish world, with regional differences; see :Orthodox yeshivas in Europe and :Orthodox yeshivas by country.

Structure and features

Yeshiva study is differentiated from, for example university study, by several features, apart from the curriculum. The year is structured into "''zmanim''"; the day is structured into "''seders''". The learning itself is delivered through a "''shiur''", a discursive-lecture with pre-specified sources, or "''marei mekomot''" (מראה מקומות; “bibliography”, lit. "indication of the (textual) locations");Example ''marei mekomot'' - Halacha

Yeshiva study is differentiated from, for example university study, by several features, apart from the curriculum. The year is structured into "''zmanim''"; the day is structured into "''seders''". The learning itself is delivered through a "''shiur''", a discursive-lecture with pre-specified sources, or "''marei mekomot''" (מראה מקומות; “bibliography”, lit. "indication of the (textual) locations");Example ''marei mekomot'' - Halacha/ref>Example ''marei mekomot'' - Gemara

/ref> study in general, and particularly the preparation for ''shiur'', takes place in "" or paired-study. This study is in a common venue called the '' bet midrash'' (

Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

, "zal" i.e. "hall").

The institution is headed by its ''rosh yeshiva

Rosh yeshiva ( he, ראש ישיבה, pl. he, ראשי ישיבה, '; Anglicized pl. ''rosh yeshivas'') is the title given to the dean of a yeshiva, a Jewish educational institution that focuses on the study of traditional religious texts, primar ...

'', while other senior rabbis are referred to as "Ram" ('' rosh mesivta or reish metivta''); the ''mashgiach'' assumes responsibility for students' spiritual development ('' mashpia'', in Hasidic yeshivot). A ''kollel'' is headed by its '' rosh kollel'', even when it is part of a yeshiva. A ''sho'el u'meishiv'' ( he, שואל ומשיב; ask and he answers; often simply "''meishiv''", or alternately "''nosay v'notayn''") is available to consult to students on difficult points in their day's Talmudic studies. The rabbi responsible for the Talmudic ''shiur'' is known as a '' maggid shiur''. Students are known as ''talmidim'' (sing. ''talmid'').

'' Rav muvhak'' is sometimes used in reference to one's primary teacher; correspondingly, ''talmid muvhak'' may refer to a primary, or outstanding, student.

Academic year

In most yeshivot, the year is divided into three periods (terms) called ''zmanim'' (lit. times; sing. ''zman''). ''Elul zman'' starts from the beginning of the Hebrew month of Elul and extends until the end of Yom Kippur. The six-weeks-long semester is the shortest yet most intense session, as it comes before the High Holidays ofRosh Hashanah

Rosh HaShanah ( he, רֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה, , literally "head of the year") is the Jewish New Year. The biblical name for this holiday is Yom Teruah (, , lit. "day of shouting/blasting") It is the first of the Jewish High Holy Days (, , " ...

and Yom Kippur. Winter ''zman'' starts after Sukkot

or ("Booths, Tabernacles")

, observedby = Jews, Samaritans, a few Protestant denominations, Messianic Jews, Semitic Neopagans

, type = Jewish, Samaritan

, begins = 15th day of Tishrei

, ends = 21st day of Tishre ...

and lasts until about two weeks before Passover, a duration of five months (six in a Jewish leap year). Summer ''zman'' starts after Passover and lasts until Rosh Chodesh Av or Tisha B'Av, a duration of about three months.

Chavruta-style learning

Yeshiva students prepare for and review the ''shiur'' (lecture) with their ''chavruta'' during a study session known as a ''seder''. In contrast to conventional classroom learning, in which a teacher lectures to the student, ''chavruta''-style learning requires the student to analyze and explain the material, point out the errors in their partner's reasoning, and question and sharpen each other's ideas, often arriving at entirely new insights of the meaning of the text. A ''chavruta'' is intended to help a student keep their mind focused on the learning, sharpen their reasoning powers, develop their thoughts into words, organize their thoughts into logical arguments, and understand another person's viewpoint. The shiur-based system was innovated at the Telshe yeshiva, where there were five levels. Chavruta-style learning tends to be animated, as study partners read the Talmudic text and the commentaries aloud to each other, and then analyze, question, debate, and argue their points of view to arrive at an understanding of the text. In the heat of discussion, they may wave their hands, pound the table, or shout at each other. Depending on the size of the yeshiva, dozens or even hundreds of pairs of ''chavrutas'' can be heard discussing and debating each other's viewpoints. Students need to learn the ability to block out other discussions in order to focus on theirs.Types of yeshivot

# Yeshiva Ketana (junior yeshiva) or "Talmud Torah" – Many Haredi (non-Hasidic and Hasidic) yeshivot ketanot in Israel, and some (primarily Hasidic) in the Diaspora, do not have a secular course of studies, with all students learning Judaic Torah studies full-time.

# Yeshiva High School – also called ''

# Yeshiva Ketana (junior yeshiva) or "Talmud Torah" – Many Haredi (non-Hasidic and Hasidic) yeshivot ketanot in Israel, and some (primarily Hasidic) in the Diaspora, do not have a secular course of studies, with all students learning Judaic Torah studies full-time.

# Yeshiva High School – also called ''Mesivta

''Mesivta'' (also metivta; Aramaic: מתיבתא, "academy") is an Orthodox Jewish yeshiva secondary school for boys. The term is commonly used in the United States to describe a yeshiva that emphasizes Talmudic studies for boys in grades ...

'' (Metivta) or ''Mechina'' or ''Yeshiva Ketana'', or in Israel, ''Yeshiva Tichonit'' – combines the intensive Jewish religious education with a secular high school education. The dual curriculum was pioneered by the Manhattan Talmudical Academy of Yeshiva University (now known as Marsha Stern Talmudical Academy

The Marsha Stern Talmudical Academy, also known as Yeshiva University High School for Boys (YUHSB), MTA (Manhattan Talmudical Academy) or TMSTA, is an Orthodox Jewish day school (or yeshiva) and the boys' prep school of Yeshiva University (YU) ...

) in 1916; ALMA

Alma or ALMA may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Alma'' (film), a 2009 Spanish short animated film

* ''Alma'' (Oswald de Andrade novel), 1922

* ''Alma'' (Le Clézio novel), 2017

* ''Alma'' (play), a 1996 drama by Joshua Sobol about Alma ...

was established in Jerusalem in 1936, and "ha-Yishuv" in Tel Aviv in 1937.

# Mechina – For Israeli high-school graduates who wish to study for one year before entering the army. In Telshe yeshivas and in Ner Yisroel of Baltimore, the Mesivtas/Yeshiva ketanas are known as Mechinas.

# Beth midrash

A ''beth midrash'' ( he, בית מדרש, or ''beis medrash'', ''beit midrash'', pl. ''batei midrash'' "House of Learning") is a hall dedicated for Torah study, often translated as a "study hall." It is distinct from a synagogue (''beth kness ...

– For high school graduates, and is attended from one year to many years, dependent on the career plans and affiliation of the student.

# Yeshivat Hesder – Yeshiva that has an arrangement with the Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

by which the students enlist together in the same unit and, as much as is possible serve in the same unit in the army. Over a period of about 5 years there will be a period of service starting in the second year of about 16 months. There are different variations. The rest of the time will be spent in compulsory study in the yeshiva. The Hesder Yeshiva concept is attributed to Rav Yehuda Amital. The first was Yeshivat Kerem B'Yavneh

Yeshivat Kerem B'Yavneh ( he, ישיבת כרם ביבנה, lit. ''Vineyard in Yavne Yeshiva'') is a youth village and major yeshiva in southern Israel. Located near the city of Ashdod and adjacent to Kvutzat Yavne, it falls under the jurisdictio ...

, established in 1954; the largest is the Hesder Yeshiva of Sderot with over 800 students.

# Kollel – Yeshiva for married men. The kollel idea has its intellectual roots in the Torah; Mishnah tractate Megillah

Megillah ( he, מגילה, scroll) may refer to:

Bible

*The Book of Esther (''Megillat Esther''), read on the Jewish holiday of Purim

*The Five Megillot

*Megillat Antiochus

Rabbinic literature

*Tractate Megillah in the Talmud.

*Megillat Taanit, ...

mentions the law that a town can only be called a "city" if it supports ten men (''batlanim'') to make up the required quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a deliberative assembly (a body that uses parliamentary procedure, such as a legislature) necessary to conduct the business of that group. According to ''Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised'', the ...

for communal learning. However, it is mostly a modern innovation of 19th-century Europe. A kollel will often be in the same location as the yeshiva.

# Baal Teshuva yeshivot catering to the needs of the newly Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

.

A post-high school for women is generally called a "seminary", or '' midrasha'' (plural ''midrashot'') in Israel,''Midrashot''science.co.il and not a yeshiva. (Although there are exceptions such as Prospect Park Yeshiva.) The Haredi Bais Yaakov system was started in 1918 under the guidance of Sarah Schenirer. These institutions provide girls with a Torah education, using a curriculum that skews more toward practical ''halakha'' (Jewish law) and the study of Tanakh, rather than Talmud. The curriculum at Religious Zionist and Modern Orthodox ''midrashot'', however, often includes some study of Talmud: often Mishnah, sometimes ''Gemara''; in further distinction, curricula generally entail ''chavruta''-based study of the texts of Jewish philosophy, and likewise Tanakh is studied with commentaries. See for further discussion.

Languages

Classes in mostLithuanian

Lithuanian may refer to:

* Lithuanians

* Lithuanian language

* The country of Lithuania

* Grand Duchy of Lithuania

* Culture of Lithuania

* Lithuanian cuisine

* Lithuanian Jews as often called "Lithuanians" (''Lita'im'' or ''Litvaks'') by other Jew ...

and Hasidic

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism (Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of contem ...

yeshivot (throughout the world) are taught in Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

; Kol Torah, established in 1939 in Jerusalem and headed by Shlomo Zalman Auerbach

Shlomo Zalman Auerbach ( he, שלמה זלמן אויערבאך; July 20, 1910 – February 20, 1995) was a renowned Orthodox Jewish rabbi, posek, and rosh yeshiva of the Kol Torah yeshiva in Jerusalem. The Jerusalem neighborhood Ramat Shlomo i ...

for over 40 years, was the first mainstream Haredi yeshiva to teach in Hebrew, as opposed to Yiddish. Sephardi, Modern Orthodox, Zionist, and ''baal teshuvah'' yeshivot use Modern Hebrew or the local language. In many American non-Hassidic Yeshivos, the language generally used is English.

Students learn with each other in whatever language they are most proficient, with Hasidic students usually learning in Yiddish, Israeli Lithuanian students in Hebrew, and American Lithuanian students in English.

College credit

Some yeshivas permit students to attend college. Often there are arrangements for the student to receive credit towards a college degree for their yeshiva studies. Yeshiva University in New York provides a year's worth of credit for yeshiva studies. Haredi institutions with similar arrangements in place include Lander College for Men,Yeshivas Ner Yisroel

Ner Israel Rabbinical College (ישיבת נר ישראל), also known as NIRC and Ner Yisroel, is a Haredi yeshiva (Jewish educational institution) in Pikesville (Baltimore County), Maryland. It was founded in 1933 by Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchok Ru ...

and Hebrew Theological College.

See also .

As above

''As Above...'' was an album released in 1982 by Þeyr, an Icelandic new wave and rock group. It was issued through the Shout record label on a 12" vinyl record.

Consisting of 12 tracks, ''As above...'' contained English versions of the band's ...

, some American ''yeshivot'' in fact ''award'' the degrees Bachelor of Talmudic Law The Bachelor of Talmudic Law (BTL), Bachelor of Talmudic Studies (BTS) and First Talmudic Degree (FTD) are law degrees, comprising the study, analysis and application of ancient Talmudical, Biblical, and other historical sources. The laws derived fr ...

(4 years cumulative study), Master of Rabbinic Studies The Master of Rabbinic Studies (MRb) is a graduate degree granted by a Yeshiva or rabbinical school. It involves the academic study of Talmud, Jewish law, philosophy, ethics, and rabbinic literature;

see .

The Master of Talmudic Law is closely relat ...

/ Master of Talmudic Law

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

*Grandmaster (chess), National Master ...

(six years), and (at ''Ner Yisroel'') the Doctorate in Talmudic Law (10 years).

These degrees are nationally accredited by the Association of Advanced Rabbinical and Talmudic Schools

The Association of Advanced Rabbinical and Talmudic Schools (AARTS) is a faith-based national accreditation association for Rabbinical and Talmudic schools. It is based in New York, NY and is recognized by the Council for Higher Education Accredita ...

, and may then grant access to graduate programs such as law school.

For further discussion on the integration of secular education, see re the contemporary situation

and .

For historical context see:

;

Hildesheimer Rabbinical Seminary;

;

;

Vilna Rabbinical School and Teachers' Seminary

The Vilna Rabbinical School and Teachers' Seminary was a controversial Russian state-sponsored institution to train Jewish teachers and rabbis, located in Vilna, Russian Empire. The school opened in 1847 with two divisions: a rabbinical school and ...

;

;

;

Kelm Talmud Torah The Kelm Talmud Torah was a famous yeshiva in pre-holocaust Kelmė, Lithuania. Unlike other yeshivas, the Talmud Torah focused primarily on the study of Musar ("Jewish ethics") and self-improvement.

Under the Leadership of Simcha Zissel Ziv

The ...

;

.

Curriculum

Torah study at an Orthodox yeshiva comprises the study of rabbinic literature, principally the Talmud, along with the study of ''halacha'' (Jewish law); Musar and Hasidic philosophy are often studied also. In some institutions, classicalJewish philosophy

Jewish philosophy () includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. Until modern ''Haskalah'' (Jewish Enlightenment) and Jewish emancipation, Jewish philosophy was preoccupied with attempts to reconcile ...

or Kabbalah are formally studied, or the works of individual thinkers (such as Abraham Isaac Kook

Abraham Isaac Kook (; 7 September 1865 – 1 September 1935), known as Rav Kook, and also known by the acronym HaRaAYaH (), was an Orthodox rabbi, and the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine. He is considered to be one of ...

).

Non-Orthodox institutions offer a synthesis of traditional and critical methods, allowing Jewish texts and tradition to encounter social change and modern scholarship. The curriculum is thus also focused on classical Jewish subjects - Talmud, Tanakh, Midrash, ''halacha'', and Philosophy -

but differs from Orthodox yeshivot in that the subject-weights are more even (correspondingly, Talmud and halacha are less emphasized), and the approach entails an openness to modern scholarship;

the curriculum also emphasizes "the other functions of a modern rabbi such as preaching, counseling, and pastoral work".

Note that as mentioned, often, in these institutions less emphasis is placed on Talmud and Jewish law, "but rather on sociology, cultural studies, and modern Jewish philosophy".Rabbi Steven Blane

Steven Blane is an American rabbi, cantor and recording singer-songwriter.

Rabbi Blane, a Universalist rabbi and cantor, conducts his teaching and pastoral work online. He is the founder and dean of the Jewish Spiritual Leaders Institute, an on ...

(N.D.)"Ordination and Semicha"

jsli.net Conservative Yeshivot occupy a position midway, in that their training places (significantly) more emphasis on Halakha and Talmud than other non-Orthodox programs; see Conservative halakha. The sections below discuss the Orthodox approach - but may be seen as overviews of the traditional-content; see also re the various approaches under

List of rabbinical schools

Following is a listing of rabbinical schools, organized by denomination. The emphasis of the training will differ by denomination:

Orthodox Semikha centers on the study of Talmud-based halacha (Jewish law), while in other programs, the emphasis ...

as well as under .

Talmud study

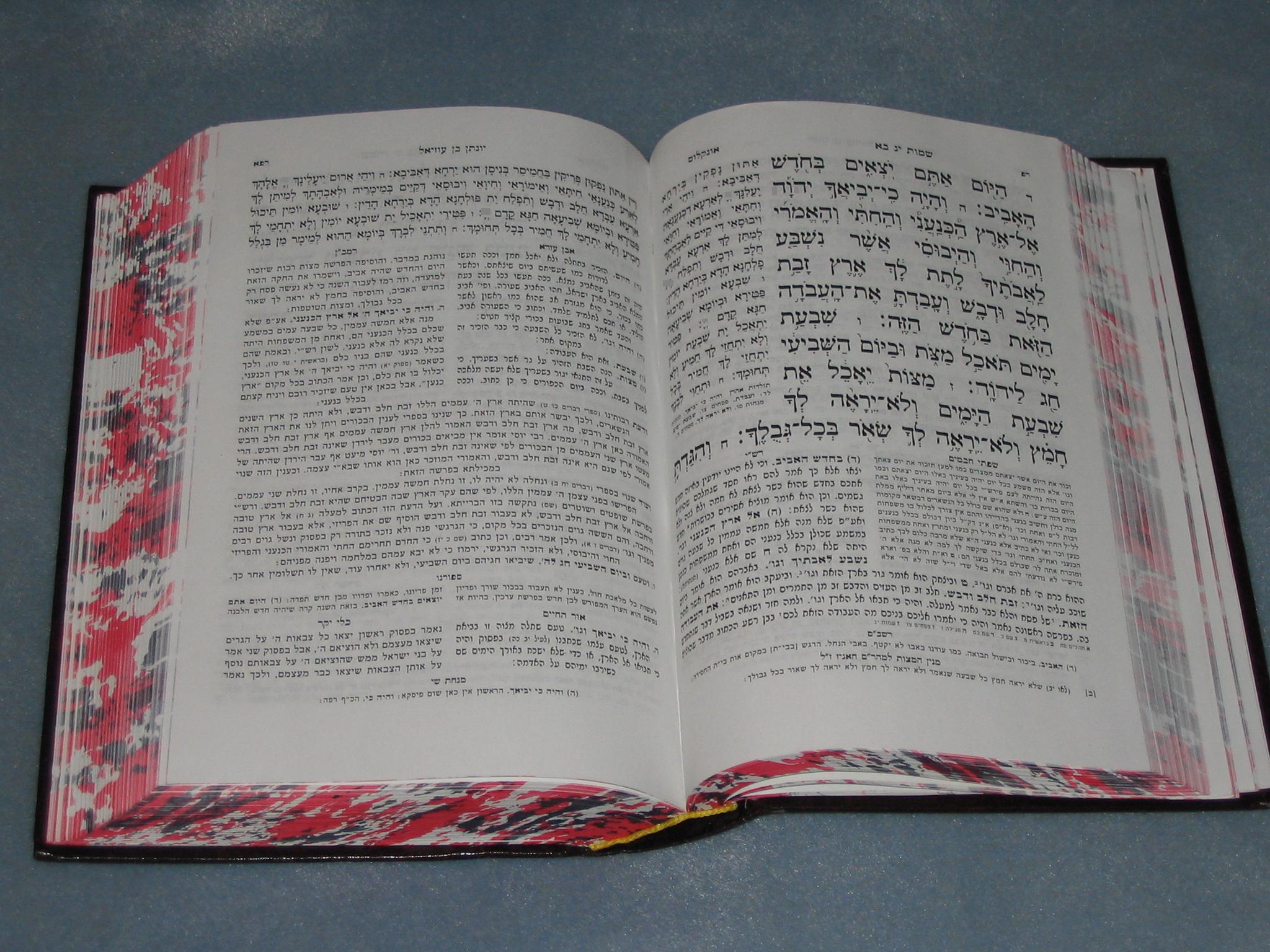

In a typical Orthodox yeshiva, the main emphasis is on Talmud study and analysis, or ''

In a typical Orthodox yeshiva, the main emphasis is on Talmud study and analysis, or ''Gemara

The Gemara (also transliterated Gemarah, or in Yiddish Gemo(r)re; from Aramaic , from the Semitic root ג-מ-ר ''gamar'', to finish or complete) is the component of the Talmud comprising rabbinical analysis of and commentary on the Mishnah w ...

''. Generally, two parallel Talmud streams are covered during a (trimester).

The first is , or in-depth study (variants described below), often confined to selected legally focused tractates with an emphasis on analytical skills and close reference to the classical commentators;

see for a discussion of the ''shakla v'tarya'', the "back and forth" analytics entailed.

The second stream, ''beki'ut'' ("expertise"), seeks to build general knowledge of the Talmud. In some Hasidic yeshivas, ("text"), is the term used for , but may also incorporate an element of memorization.

In the yeshiva system of Talmudic study, the undergraduate yeshivot focus on the '' mesechtohs'' ( tractates) that cover civil jurisprudence and monetary law ('' Nezikin'') and those dealing with contract and marital law (''Nashim

__notoc__

Nashim ( he, נשים "Women" or "Wives") is the third order of the Mishnah (also of the Tosefta and Talmud) containing family law. Of the six orders of the Mishnah, it is the shortest.

Nashim consists of seven tractates:

#''Yevamot'' ...

''); through them, the student can best master the proper technique of Talmudic analysis, and

''Catalog''Rabbinical College

Bobover

Bobov (or Bobover Hasidism) ( he, חסידות באבוב, yi, בּאָבּאָװ) is a Hasidic community within Haredi Judaism, originating in Bobowa, Galicia, in southern Poland, and now headquartered in the neighborhood of Borough Park, in B ...

the halakhic application of Talmudic principles. With these mastered, the student goes on to other areas of the Talmud (see, for example, § Cycle of Masechtos (Tractates of the Talmud) under Yeshivas Ner Yisroel

Ner Israel Rabbinical College (ישיבת נר ישראל), also known as NIRC and Ner Yisroel, is a Haredi yeshiva (Jewish educational institution) in Pikesville (Baltimore County), Maryland. It was founded in 1933 by Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchok Ru ...

).

Tractates ''Berachot'', ''Sukkah'', ''Pesachim'' and ''Shabbat'' are often included.ProgramsTalmudic University of Florida. Catalog

Central Yeshiva Tomchei Tmimim Lubavitz Sometimes tractates dealing with an upcoming

religious holiday

A holiday is a day set aside by custom or by law on which normal activities, especially business or work including school, are suspended or reduced. Generally, holidays are intended to allow individuals to celebrate or commemorate an event or tra ...

are studied before and during the holiday (e.g. ''Shabbat'' 21a-23b for Chanukah; Tractate ''Megilla'' for Purim; and so forth).

Works initially studied to clarify the Talmudic text are the commentary by Rashi, and the related work '' Tosafot'', a parallel analysis and running critique.

Se''Kuntres Eitz HaChayim'' ch 28

for discussion of the interrelation between Rashi and Tosfot The integration of Talmud, Rashi and Tosafot, is considered as foundational – and prerequisite – to further analysis See for example the guidelines for Talmud study authored by

Sholom Dovber Schneersohn

Sholom Dovber Schneersohn ( he, שלום דובער שניאורסאהן) was the fifth Rebbe (spiritual leader) of the Chabad Lubavitch chasidic movement. He is known as "the Rebbe Rashab" (for Reb Sholom Ber). His teachings represent the emerge ...

in 1897 on the founding of '' Tomchei Tmimim''''Kuntres Eitz HaChayim'' ch 28

Gemara

The Gemara (also transliterated Gemarah, or in Yiddish Gemo(r)re; from Aramaic , from the Semitic root ג-מ-ר ''gamar'', to finish or complete) is the component of the Talmud comprising rabbinical analysis of and commentary on the Mishnah w ...

'', ''perush Rashi'', ''Tosafot''). The super-commentaries by "Maharshal", "Maharam" and "Maharsha" address the three together.

At more advanced levels, additional '' mefarshim'' (commentators) are studied:

See chapter "Talmudic Exegesis" in: Adin Steinsaltz (2006). ''The Essential Talmud''. Basic Books

Basic Books is a book publisher founded in 1950 and located in New York, now an imprint of Hachette Book Group. It publishes books in the fields of psychology, philosophy, economics, science, politics, sociology, current affairs, and history.

H ...

.

other '' rishonim'', from the 11th to 14th centuries, as well as '' acharonim'', from later generations. (There are two main schools of ''rishonim'', from France and from Spain, who will hold different interpretations and understandings of the Talmud.)

At these levels, students link the Talmudic discussion to codified law – particularly '' Mishneh Torah'' (i.e. Maimonides), Arba'ah Turim and Shulchan Aruch – by studying, also, the halakha-focused commentaries of Asher ben Jehiel