Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a

Sunni Islam

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagre ...

ic

revivalist and

fundamentalist

Fundamentalism is a tendency among certain groups and individuals that is characterized by the application of a strict literal interpretation to scriptures, dogmas, or ideologies, along with a strong belief in the importance of distinguishi ...

movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century

Arabian Islamic scholar

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of reli ...

,

theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

,

preacher

A preacher is a person who delivers sermons or homilies on religious topics to an assembly of people. Less common are preachers who preach on the street, or those whose message is not necessarily religious, but who preach components such as ...

, and

activist

Activism (or Advocacy) consists of efforts to promote, impede, direct or intervene in social, political, economic or environmental reform with the desire to make changes in society toward a perceived greater good. Forms of activism range fro ...

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab ibn Sulayman al-Tamimi ( ar, محمد بن عبد الوهاب بن سليمان , translit=Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhāb ibn Sulaymān al-Tamīmī; 1703–1792) was an Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, ac ...

(). He established the ''Muwahhidun'' movement in the region of

Najd in

central Arabia as well as

South Western Arabia, a reform movement that emphasised purging of rituals related to the

veneration of Muslim saints and

pilgrimages to their tombs and shrines, which were widespread amongst the people of Najd.

Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab and his followers were highly inspired by the influential thirteenth-century

Hanbali

The Hanbali school ( ar, ٱلْمَذْهَب ٱلْحَنۢبَلِي, al-maḏhab al-ḥanbalī) is one of the four major traditional Sunni schools (''madhahib'') of Islamic jurisprudence. It is named after the Arab scholar Ahmad ibn Hanbal ...

scholar

Ibn Taymiyyah (1263–1328 C.E/ 661 – 728 A.H) who called for a return to the purity of the first three generations (''

Salaf

Salaf ( ar, سلف, "ancestors" or "predecessors"), also often referred to with the honorific expression of "al-salaf al-ṣāliḥ" (, "the pious predecessors") are often taken to be the first three generations of Muslims. This comprises Muhamm ...

'') to rid Muslims of inauthentic outgrowths (''

bidʻah

In Islam, bid'ah ( ar, بدعة; en, innovation) refers to innovation in religious matters. Linguistically, the term means "innovation, novelty, heretical doctrine, heresy".

In classical Arabic literature ('' adab''), it has been used as a fo ...

''), and regarded his works as core scholarly references in theology. While being influenced by their Hanbali doctrines, the movement repudiated ''

Taqlid

''Taqlid'' (Arabic تَقْليد ''taqlīd'') is an Islamic term denoting the conformity of one person to the teaching of another. The person who performs ''taqlid'' is termed ''muqallid''. The definite meaning of the term varies depending on co ...

'' to legal authorities, including oft-cited scholars such as Ibn Taymiyya and

Ibn Qayyim

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr ibn Ayyūb al-Zurʿī l-Dimashqī l-Ḥanbalī (29 January 1292–15 September 1350 CE / 691 AH–751 AH), commonly known as Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya ("The son of the principal of he school ...

(d. 1350 C.E/ 751 A.H).

Wahhabism has been variously described as "orthodox",

"puritan(ical)",

"revolutionary"; and as an Islamic "reform movement" to restore "pure

monotheistic worship" by devotees.

[. "wahhabism"] The term "Wahhabism" was not used by Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab himself, but is chiefly used by outsiders, while adherents typically reject its use, preferring to be called ''

"Salafi"'' (a term also used by followers of other Islamic reform movements as well).

The movement's early followers referred to themselves as ''

Muwahhidun'' ( ar, الموحدون, lit="one who professes God's oneness" or "Unitarians" derived from ''Tawhid'' (the oneness of God).

The term "Wahhabism" is also used as a sectarian and

Islamophobic

Islamophobia is the fear of, hatred of, or prejudice against the religion of Islam or Muslims in general, especially when seen as a geopolitical force or a source of terrorism.

The scope and precise definition of the term ''Islamophobia'' ...

slur. Socio-politically, the movement represented the first major Arab-led protest against the Turkish, Persian and foreign empires that dominated the

Islamic World since the

Mongol invasions

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire: the Mongol Empire ( 1206- 1368), which by 1300 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastati ...

and the fall of

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

in the 13th century; and would later serve as a revolutionary impetus for 19th-century

pan-Arabism.

In 1744, Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab formed a pact with a local leader,

Muhammad bin Saud

Muhammad bin Saud Al Muqrin ( ''Muḥammad bin Suʿūd Āl Muqrin''; 1687–1765), also known as Ibn Saud, was the emir of Diriyah and is considered the founder of the First Saudi State and the Saud dynasty, which are named for his father, Sa ...

,

[. "the two ... concluded a pact. Ibn Saud would protect and propagate the stern doctrines of the Wahhabi mission, which made the Koran the basis of government. In return, Abdul Wahhab would support the ruler, supplying him with 'glory and power'. Whoever championed his message, he promised, 'will, by means of it, rule and lands and men'."] a politico-religious alliance that continued for the next 150 years, culminating politically with the proclamation of the

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932. His movement would eventually arise as one of the most influenctial 18th century

anti-colonial

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence ...

reform trends that spread across the Islamic World; advocating a return to pristine Islamic values based on ''

Qur’an'' and

Sunnah for re-generating the social and political prowess of

Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...

; and its revolutionary themes influenced numerous

Islamic revival

Islamic revival ( ar, تجديد'' '', lit., "regeneration, renewal"; also ', "Islamic awakening") refers to a revival of the Islamic religion. The revivers are known in Islam as ''mujaddids''.

Within the Islamic tradition, ''tajdid'' has bee ...

ists, scholars,

pan-Islamist

Pan-Islamism ( ar, الوحدة الإسلامية) is a political movement advocating the unity of Muslims under one Islamic country or state – often a caliphate – or an international organization with Islamic principles. Pan-Islamism w ...

ideologues and anti-colonial activists as far as

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

. For more than two centuries through to the present, Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab's teachings were championed as the official form of

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

and the dominant creed in three Saudi States.

As of 2017, changes to Saudi religious policy by

Crown Prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title is crown princess, which may refer either to an heiress apparent or, especially in earlier times, to the wif ...

Mohammed bin Salman

Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud ( ar, محمد بن سلمان آل سعود, translit=Muḥammad bin Salmān Āl Su‘ūd; born 31 August 1985), colloquially known by his initials MBS or MbS, is Crown Prince and Prime Minister of Saudi Arabia. H ...

have led some to suggest that "Islamists throughout the world will have to follow suit or risk winding up on the wrong side of orthodoxy".

In 2018 Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, denied that anyone "can define this Wahhabism" or even that it exists. By 2021, the waning power of the religious clerics brought forth by the social, religious, economic, political changes and a new educational policy asserting a "Saudi national identity" that emphasize non-Islamic components have led to what has been described as the "post-Wahhabi era" of Saudi Arabia.

By 2022, the decision to celebrate the "Saudi Founding Day" annually on 22 February to commemorate the 1727 establishment of

Emirate of Dir'iyah by

Muhammad ibn Saud

Muhammad bin Saud Al Muqrin ( ''Muḥammad bin Suʿūd Āl Muqrin''; 1687–1765), also known as Ibn Saud, was the emir of Diriyah and is considered the founder of the First Saudi State and the Saud dynasty, which are named for his father, Sau ...

, rather than the past historical convention that traced the beginning to the

1744 pact of Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab; have led to the official "uncoupling" of the religious clergy by the Saudi state.

Definitions and etymology

Definitions

Some definitions or uses of the term Wahhabi Islam include:

* "a corpus of doctrines", and "a set of attitudes and behavior, derived from the teachings of a particularly severe religious reformist who lived in central Arabia in the mid-eighteenth century" (

Gilles Kepel

Gilles Kepel, (born June 30, 1955) is a French political scientist and Arabist, specialized in the contemporary Middle East and Muslims in the West. He is Professor at the Université Paris Sciences et Lettres (PSL) and director of the Middle Ea ...

)

* "pure Islam" (

David Commins

David Commins (born 1954) is an American scholar and Professor of History and Benjamin Rush Chair in the Liberal Arts and Sciences (1987) at Dickinson College. He is known for his works on Wahhabism

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَ ...

, paraphrasing supporters' definition),

[. "While Wahhabism claims to represent Islam in its purest form, other Muslims consider it a misguided creed that fosters intolerance, promotes simplistic theology, and restricts Islam's capacity for adaption to diverse and shifting circumstances."] that does not deviate from ''

Sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

'' (Islamic law) in any way and should be called Islam and not Wahhabism. (

Salman bin Abdul Aziz,

King of Saudi Arabia

The king of Saudi Arabia is the monarchial head of state and ruler of Saudi Arabia who holds absolute power. He is the head of the Saudi Arabian royal family, the House of Saud. The king is called the "Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques" (), a ...

)

* "a misguided creed that fosters intolerance, promotes simplistic theology, and restricts Islam's capacity for adaption to diverse and shifting circumstances" (David Commins, paraphrasing opponents' definition)

* "a conservative reform movement... the creed upon which the kingdom of Saudi Arabia was founded, and

hich

Ij ( fa, ايج, also Romanized as Īj; also known as Hich and Īch) is a village in Golabar Rural District, in the Central District of Ijrud County, Zanjan Province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also ...

has influenced Islamic movements worldwide" (''Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim world'')

* "a sect dominant in Saudi Arabia and

Qatar

Qatar (, ; ar, قطر, Qaṭar ; local vernacular pronunciation: ), officially the State of Qatar,) is a country in Western Asia. It occupies the Qatar Peninsula on the northeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in the Middle East; it sh ...

" with footholds in "

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

,

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, and elsewhere", with a "steadfastly fundamentalist interpretation of Islam in the tradition of

Ibn Hanbal

Ahmad ibn Hanbal al-Dhuhli ( ar, أَحْمَد بْن حَنْبَل الذهلي, translit=Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal al-Dhuhlī; November 780 – 2 August 855 CE/164–241 AH), was a Muslim jurist, theologian, ascetic, hadith traditionist, and f ...

" (Cyril Glasse)

[see also: Glasse, Cyril, ''The New Encyclopedia of Islam'', Rowman & Littlefield, (2001), pp. 469–72]

* an "eighteenth-century reformist/revivalist movement for sociomoral reconstruction of society", "founded by Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab" (

Oxford Dictionary of Islam).

* A movement that sought "a return to the pristine message of the

Prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

" and attempted to free Islam from all "the superimposed doctrines" and "superstitions that have obscured its message". Its spiritual meaning of "striving after an inner renewal of Muslim society", got corrupted when "its outer goalthe attainment of social and political powerwas realised" (

Muhammad Asad

Muhammad Asad, ( ar, محمد أسد , ur, , born Leopold Weiss; 2 July 1900 – 20 February 1992) was an Austro-Hungarian-born Pakistani journalist, traveler, writer, linguist, political theorist and diplomat. He was a Jew but, later conve ...

)

* "a political trend" within Islam that "has been adopted for power-sharing purposes", but cannot be called a sect because "It has no special practices, nor special rites, and no special interpretation of religion that differ from the main body of

Sunni Islam

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagre ...

" (Abdallah Al Obeid, the former dean of the

Islamic University of Medina

The Islamic University of Madinah ( ar, الجامعة الإسلامية بالمدينة المنورة) was founded by the government of Saudi Arabia by a royal decree in 1961 in the Islamic holy city of Medina. Many have associated the univer ...

and member of the Saudi Consultative Council)

* "the true

salafist

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three generati ...

movement". Starting out as a theological reform movement, it had "the goal of calling (''

da'wa

Dawah ( ar, دعوة, lit=invitation, ) is the act of inviting or calling people to embrace Islam. The plural is ''da‘wāt'' (دَعْوات) or ''da‘awāt'' (دَعَوات).

Etymology

The English term ''Dawah'' derives from the Arabic ...

'') people to restore the 'real' meaning of ''Tawhid'' (oneness of God or monotheism) and to disregard and deconstruct 'traditional' disciplines and practices that evolved in Islamic history such as theology and jurisprudence and the traditions of

visiting tombs and shrines of venerated individuals." (Ahmad Moussalli)

* a term used by opponents of Salafism in hopes of besmirching that movement by suggesting foreign influence and "conjuring up images of Saudi Arabia". The term is "most frequently used in countries where Salafis are a small minority" of the Muslim community but "have made recent inroads" in "converting" the local population to Salafism. (Quintan Wiktorowicz)

* a blanket term used inaccurately to refer to "any Islamic movement that has an apparent tendency toward misogyny, militantism, extremism, or strict and literal interpretation of the ''

Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing. ...

'' and ''

hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

''" (

Natana J. DeLong-Bas)

* "No one can define Wahhabism. There is no Wahhabism. We don't believe we have Wahhabism." (Mohammed bin Salman, Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia)

* According to

Doctor of Philosophy

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common Academic degree, degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields ...

at

RMIT University

RMIT University, officially the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology,, section 4(b) is a public research university in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city ...

, Rohan Davis:

Etymology

The term Wahhabi should not be confused to

Wahbi which is the dominant creed within

Ibadism

The Ibadi movement or Ibadism ( ar, الإباضية, al-Ibāḍiyyah) is a school of Islam. The followers of Ibadism are known as the Ibadis.

Ibadism emerged around 60 years after the Islamic prophet Muhammad's death in 632 AD as a moderate sc ...

.

Since the

colonial period, the

Wahhabi epithet has been commonly invoked by various external observers to erronoeusly or pejoritavely denote a wide range of

reform

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement ...

movements across the

Muslim World

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

.

Algerian

Algerian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to Algeria

* Algerian people

This article is about the demographic features of the population of Algeria, including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, econo ...

scholar Muhammad El Hajjoui states that it was Ottomans who first attached the label of "Wahhabism" to the

Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

Hanbali

The Hanbali school ( ar, ٱلْمَذْهَب ٱلْحَنۢبَلِي, al-maḏhab al-ḥanbalī) is one of the four major traditional Sunni schools (''madhahib'') of Islamic jurisprudence. It is named after the Arab scholar Ahmad ibn Hanbal ...

s of Najd, hiring "Muslim scholars in all countries to compose, write and lie about the Hanbalis of Najd" for political purposes.

The labelling of the term "Wahhabism" has historically been expansive beyond the doctrinal followers of

Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab; all of whom tend to reject the label. Hence the term remains a controversial as well as a contested category. During the

colonial era, the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

had commonly employed the term to refer to those

Muslim scholars

This article is an incomplete list of noted modern-era (20th to 21st century) Islamic scholars. This refers to religious authorities whose publications or statements are accepted as pronouncements on religion by their respective communities and ...

and thinkers seen as obstructive to their imperial interests; punishing them under various pretexts. Many Muslim rebels inspired by

Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

''

Awliyaa'' (saints) and

mystical orders, were targeted by the

British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was himsel ...

as part of a wider "Wahhabi" conspiracy which was portrayed as extending from

Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

to

Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising ...

. Despite sharing little resemblance with the doctrines of Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab, outside observers of the Muslim world have frequently traced various religious purification campaigns across the Islamic World to Wahhabi influence.

According to Qeyamuddin Ahmed:

Indian ''

Ahl-i Hadith'' leader

Nawab

Nawab (Balochi language, Balochi: نواب; ar, نواب;

bn, নবাব/নওয়াব;

hi, नवाब;

Punjabi language, Punjabi : ਨਵਾਬ;

Persian language, Persian,

Punjabi language, Punjabi ,

Sindhi language, Sindhi,

Urd ...

Sīddïq Hasān Khán (1832–1890 C.E) strongly objected to the usage of the term "Wahhabi"; viewing it as a restrictive regional term primarily rooted in geography and also considered the term to be politically manipulative. According to him, labelling the exponents of ''

Tawhid

Tawhid ( ar, , ', meaning "unification of God in Islam ( Allāh)"; also romanized as ''Tawheed'', ''Tawhid'', ''Tauheed'' or ''Tevhid'') is the indivisible oneness concept of monotheism in Islam. Tawhid is the religion's central and single ...

'' as "Wahhabi" was wrong since it symbolised a form of regionalism that went against Islamic universalism. Khan argues that the term has different, unrelated and narrow localised connotations across different parts of the World. According to him, the term had become a political and pejorative phrase that borrowed the name as well as the damaging connotation of the culturally exclusivist movement of

Ibn 'Abd-al-Wahhab of Najd, and falsely applied it to a wide range of

anti-colonial

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence ...

Islamic reform movements. He distanced himself as well as the Indian Muslim public from this label, writing:

Contemporary usage

In contemporary discourse, the

post-Soviet states

The post-Soviet states, also known as the former Soviet Union (FSU), the former Soviet Republics and in Russia as the near abroad (russian: links=no, ближнее зарубежье, blizhneye zarubezhye), are the 15 sovereign states that wer ...

widely employ the term "Wahhabism" to denote any manifestation of Islamic assertion in neighbouring Muslim countries.

During the

Soviet-era

The history of Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union (USSR) reflects a period of change for both Russia and the world. Though the terms "Soviet Russia" and "Soviet Union" often are synonymous in everyday speech (either acknowledging the dominance ...

, the Muslim dissidents were usually labelled with terms such as "Sufi" and "fanatic" employing

Islamophobic

Islamophobia is the fear of, hatred of, or prejudice against the religion of Islam or Muslims in general, especially when seen as a geopolitical force or a source of terrorism.

The scope and precise definition of the term ''Islamophobia'' ...

vocabulary that conjured up fears of underground religious conspiracies. By the late 1990s, the "Wahhabi" label would become the most common term to refer to the "Islamic Menace", while "Sufism" was invoked as a "moderate" force that balanced the "radicalism" of Wahhabis. The old-guard of the post-Soviet states found the label useful to depict all opposition as extremists, thereby bolstering their strongman credentials. In short, any Muslim critical of the religious or political status quo, came at risk of being labelled "Wahhabi".

According t

M. Reza Pirbhai Associate Professor of History in

Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private university, private research university in the Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll (archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll in 1789 as Georg ...

, notions of a "Wahhabi Conspiracy" against the

West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sunset, Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic languages, German ...

have in recent times resurfaced in various sections of the

Western media

Western media is the mass media of the Western world. During the Cold War, Western media contrasted with Soviet media. Western media has gradually expanded into developing countries (often, non-Western countries) around the world.

History

Th ...

; employing the term as a catch-all phrase to frame an official narrative that erases the concerns of broad and disparate disenchanted groups pursuing redress for local discontentment caused by

neo-colonialism

Neocolonialism is the continuation or reimposition of imperialist rule by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony). Neocolonialism takes the form of economic imperialism, g ...

. The earliest mention of "Wahhabism" in ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' had appeared in a 1931 editorial which described it as a "traditional" movement; without associating it with "militant" or "

anti-Western" trends. Between 1931 and 2007, ''The New York Times'' published eighty-six articles that mentioned the word "Wahhabism", out of which six articles had appeared before September 2001, while the rest were published since. During the 1990s, it began to be described as "militant", but not yet as a hostile force. By the 2000s, the 19th century terminology of "Wahhabism" had resurfaced, reprising its role as the " 'fanatical' and 'despotic' antithesis of a Civilized World". Reza Pirbhai asserts that this usage is deployed to manufacture an official narrative that assists imperial motives; by depicting a coherent and coordinated International network of ideological revolutionaries. Common

Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

depictions of ''Wahhabism'' define it as a collection of restrictive dogmas, particularly for women, while

neo-conservative

Neoconservatism is a political movement that began in the United States during the 1960s among liberal hawks who became disenchanted with the increasingly pacifist foreign policy of the Democratic Party and with the growing New Left and cou ...

depictions portray "Wahhabis" as "Savages" or "fanatics".

Naming controversy and confusion

Wahhabis do not likeor at least did not likethe term. Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab was averse to the elevation of scholars and other individuals, including using a person's name to label an Islamic school (''

madhhab

A ( ar, مذهب ', , "way to act". pl. مَذَاهِب , ) is a school of thought within ''fiqh'' (Islamic jurisprudence).

The major Sunni Mathhab are Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali.

They emerged in the ninth and tenth centuries CE an ...

'').

Due to its perceived negative overtones, the members of the movement historically identified themselves as "''Muwahhidun''", Muslims, etc. and more recently as "Salafis". According to

Robert Lacey

Robert Lacey (born 3 January 1944) is a British historian and biographer. He is the author of a number of best-selling biographies, including those of Henry Ford, Eileen Ford, Queen Elizabeth II and other British royal family, royals, as well a ...

"the Wahhabis have always disliked the name customarily given to them" and preferred to be called ''

Muwahhidun'' (Unitarians). Another preferred term was simply "Muslims", since they considered their creed to be the "pure Islam".

However, critics complain these terms imply that non-Wahhabi Muslims are either not monotheists or

not Muslims.

Additionally, the terms ''Muwahhidun'' and Unitarians are associated with other sects, both extant and extinct.

Other terms Wahhabis have been said to use and/or prefer include ''

Ahl al-Hadith

Ahl al-Ḥadīth ( ar, أَهْل الحَدِيث, translation=The People of Hadith) was an Islamic school of Sunni Islam that emerged during the 2nd/3rd Islamic centuries of the Islamic era (late 8th and 9th century CE) as a movement of hadith ...

'' ("People of the Hadith"), ''Salafi dawah'' ("Salafi preaching"), or ''al-da'wa ila al-tawhid''

("preaching of monotheism" for the school rather than the adherents) or ''Ahl ul-Sunna wal Jama'a'' ("people of the tradition of Muhammad and the consensus of the Ummah"),

''Ahl al-Sunnah'' ("People of the Sunnah"), ''al-Tariqa al-Muhammadiyya'' ("the path of the Prophet Muhammad"),

''al-Tariqa al-Salafiyya'' ("the way of the pious ancestors"),

"the reform or Salafi movement of the Sheikh" (the sheikh being Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab), etc. The self-designation as "People of the Sunnah" was important for Wahhabism's authenticity, because during the Ottoman period only

Sunnism was the legitimate doctrine.

Other writers such as Quinton Wiktorowicz, urge use of the term "Salafi", maintaining that "one would be hard pressed to find individuals who refer to themselves as Wahhabis or organizations that use 'Wahhabi' in their title, or refer to their ideology in this manner (unless they are speaking to a Western audience that is unfamiliar with Islamic terminology, and even then usage is limited and often appears as 'Salafi/Wahhabi')". A ''New York Times'' journalist writes that Saudis "abhor" the term Wahhabism, "feeling it sets them apart and contradicts the notion that Islam is a monolithic faith".

Saudi King

Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud

Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud ( ar, سلمان بن عبد العزیز آل سعود, , ; born 31 December 1935) is King of Saudi Arabia, reigning since 2015, and served as Prime Minister of Saudi Arabia from 2015 to 2022. The 25th son of Ki ...

for example has attacked the term as "a doctrine that doesn't exist here (Saudi Arabia)" and challenged users of the term to locate any "deviance of the form of Islam practiced in Saudi Arabia from the teachings of the

Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

and Prophetic

Hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

s".

Ingrid Mattson

Ingrid Mattson (born August 24, 1963) is a Canadian activist and scholar, A professor of Islamic studies, she is currently the London and Windsor Community Chair in Islamic Studies at Huron University College at the University of Western Ontario ...

argues that "'Wahhbism' is not a sect. It is a social movement that began 200 years ago to rid Islam of rigid cultural practices that had (been) acquired over the centuries."

On the other hand, according to authors at Global Security and

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

the term is now commonplace and used even by Wahhabi scholars in the Najd,

a region often called the "heartland" of Wahhabism. Journalist Karen House calls 'Salafi' "a more politically correct term" for 'Wahhabi'. In any case, according to Lacey, none of the other terms have caught on, and so like the Christian

Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

, Wahhabis have "remained known by the name first assigned to them by their detractors". However, the confusion is further aggravated due to the common practice of various authoritarian governments broadly using the label "Wahhabi extremists" for all opposition, legitimate and illegitimate, to justify massive repressions on any dissident.

(Another movement, whose adherents are also called "Wahhabi" but whom were

Ibaadi Kharijites

The Kharijites (, singular ), also called al-Shurat (), were an Islamic sect which emerged during the First Fitna (656–661). The first Kharijites were supporters of Ali who rebelled against his acceptance of arbitration talks to settle the ...

, has caused some confusion in North and sub-Saharan Africa, where the movement's leader –

Abd al-Wahhab ibn Abd al-Rahman

Abd al-Wahhab ibn Abd al-Rahman ibn Rustam, was the second ''imam'' of the Imamate of Tahart and founder of the Wahbi Ibadism movement. He was part of the Rustamid dynasty that ruled a theocracy in what is now Tunis and Algeria. He became ruler ...

– lived and preached in the Eighth Century C.E. This movement is often mistakenly conflated with the ''Muwahhidun'' movement of Muhammad Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab.)

Wahhabis and Salafis

''

Salafiyya movement'' (term derived from "''

Salaf al-Salih''", meaning "pious predecessors of the first three generations") refers to a wide range of

reform movements

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary m ...

within Sunni Islam across the world, that campaigns for the return of "pure" Islam,

revival of the

prophetic

In religion, a prophecy is a message that has been communicated to a person (typically called a ''prophet'') by a supernatural entity. Prophecies are a feature of many cultures and belief systems and usually contain divine will or law, or pret ...

''

Sunnah'', and the practices of the early generations of

Islamic scholars. According to

Saudi scholar

Abd al-Aziz Bin Baz:

The Salafi call is the call to what God have sent by His Prophet Muhammad, may peace and blessings be upon him, it is the call to adhere to the Quran and the Sunnah, this call to Salafism is the call to follow the practices that the Messenger used to follow in Mecca, then Medina. From teaching dawa to Muslims, to directing people to do good, teaching them what God sent by His Prophet on the oneness of God (monotheism), loyalty to him, and faith in His Messenger Muhammad, may peace and blessings be upon him.

Many scholars and critics distinguish between Wahhabi and Salafi. According to analyst Christopher M. Blanchard, Wahhabism refers to "a conservative Islamic creed centered in and emanating from Saudi Arabia", while ''Salafiyya'' is "a more general puritanical Islamic movement that has developed independently at various times and in various places in the Islamic world".

However, many view Wahhabism as the Salafism native to Arabia. Ahmad Moussalli tends to agree Wahhabism is a subset of Salafism, saying "As a rule, all Wahhabis are salafists, but not all salafists are Wahhabis."

Quintan Wiktorowicz aserts modern Salafists consider the 18th-century scholar Muhammed bin 'Abd al-Wahhab and many of his students to have been Salafis.

According to Joas Wagemakers, associate professor of Islamic and Arabic Studies at

Utrecht University

Utrecht University (UU; nl, Universiteit Utrecht, formerly ''Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht'') is a public research university in Utrecht, Netherlands. Established , it is one of the oldest universities in the Netherlands. In 2018, it had an enrollme ...

, Salafism consists of broad movements of

Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...

across the world who aspire to live according to the precedents of the ''

Salaf al-Salih''; whereas "Wahhabism" – a term rejected by its adherents – refers to the specific brand of reformation (''

islah

Islah or Al-Islah (الإصلاح ,إصلاح, ') is an Arabic word, usually translated as "reform", in the sense of "to improve, to better, to put something into a better position, fundamentalism, correction, correcting something and removing v ...

'') campaign that was initiated by the 18th-century scholar

Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab and evolved through his subsequent disciples in the central Arabian region of Najd. Despite their relations with Wahhabi Muslims of Najd; other Salafis have often differed theologically with the Wahhabis and hence do not identify with them. These included significant contentions with Wahhabis over their unduly harsh enforcement of their beliefs, their lack of tolerance towards other Muslims and their deficient commitment to their stated opposition to ''

taqlid

''Taqlid'' (Arabic تَقْليد ''taqlīd'') is an Islamic term denoting the conformity of one person to the teaching of another. The person who performs ''taqlid'' is termed ''muqallid''. The definite meaning of the term varies depending on co ...

'' and advocacy of ''

ijtihad''.

In doctrines of ''

'Aqida'' (creed), Wahhabis and Salafis resemble each other; particularly in their focus on ''

Tawhid

Tawhid ( ar, , ', meaning "unification of God in Islam ( Allāh)"; also romanized as ''Tawheed'', ''Tawhid'', ''Tauheed'' or ''Tevhid'') is the indivisible oneness concept of monotheism in Islam. Tawhid is the religion's central and single ...

''. However, the ''Muwahidun'' movement historically were concerned primarily about ''Tawhid al-Rububiyya'' (Oneness of Lordship) and ''Tawhid al-Uloohiyya'' (Oneness of Worship) while the ''Salafiyya'' movement placed an additional emphasis on ''Tawhid al-Asma wa Sifat'' (Oneness of Divine Names and Attributes); with a literal understanding of God's Names and Attributes.

History

The Wahhabi mission started as a

revivalist and

reform

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement ...

movement in the remote, arid region of Najd during the 18th century.

[.] During this era, numerous

pre-Islamic beliefs and customs were practiced by the Arabian Bedouin. These included various

folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, ranging ...

s associated with

ancestral worship

The veneration of the dead, including one's ancestors, is based on love and respect for the deceased. In some cultures, it is related to beliefs that the dead have a continued existence, and may possess the ability to influence the fortune of t ...

, belief in

cult of saints

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern Orth ...

,

animist

Animism (from Latin: ' meaning 'breath, Soul, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct Spirituality, spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things—Animal, animals, Plant, plants, Ro ...

practices, solar myths, fetishism, etc. which had become popular amongst the nomadic tribes of central Arabia.

Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab, the leader of the ''Muwahhidun'', advocated the purging of practices such as veneration of stones, trees, and caves; Dua, praying to saints; and

pilgrimages to their tombs and shrines that were prevalent amongst the people of Najd, but which he considered idolatrous impurities and innovations in Islam (''bid'ah'').

His movement emphasized adherence to the

Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

and ''

hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

'', and advocated the use of ''

ijtihad''.

Eventually, Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab formed a pact with a local leader,

Muhammad bin Saud

Muhammad bin Saud Al Muqrin ( ''Muḥammad bin Suʿūd Āl Muqrin''; 1687–1765), also known as Ibn Saud, was the emir of Diriyah and is considered the founder of the First Saudi State and the Saud dynasty, which are named for his father, Sa ...

, offering political obedience and promising that protection and propagation of the Wahhabi movement meant "power and glory" and rule of "lands and men".

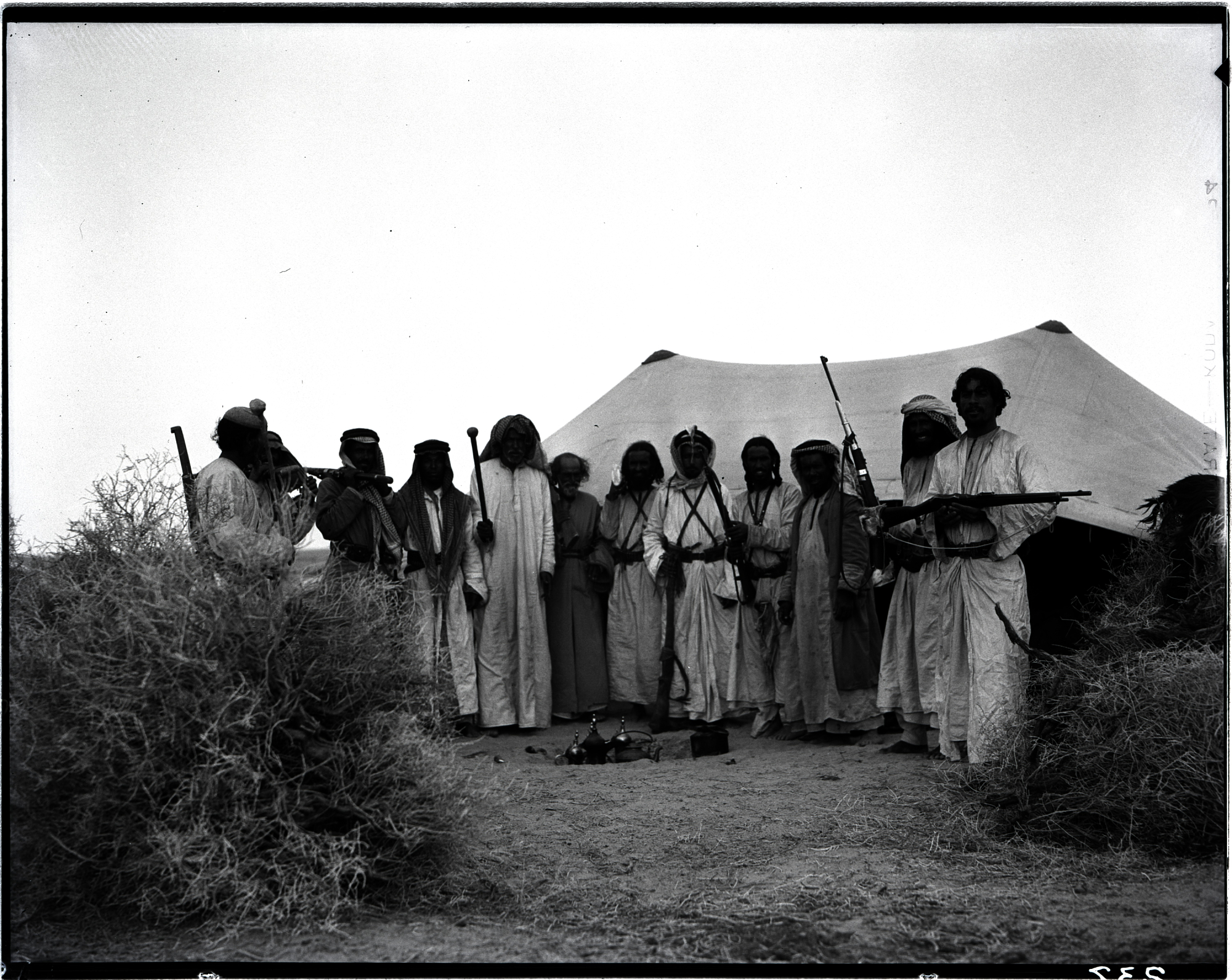

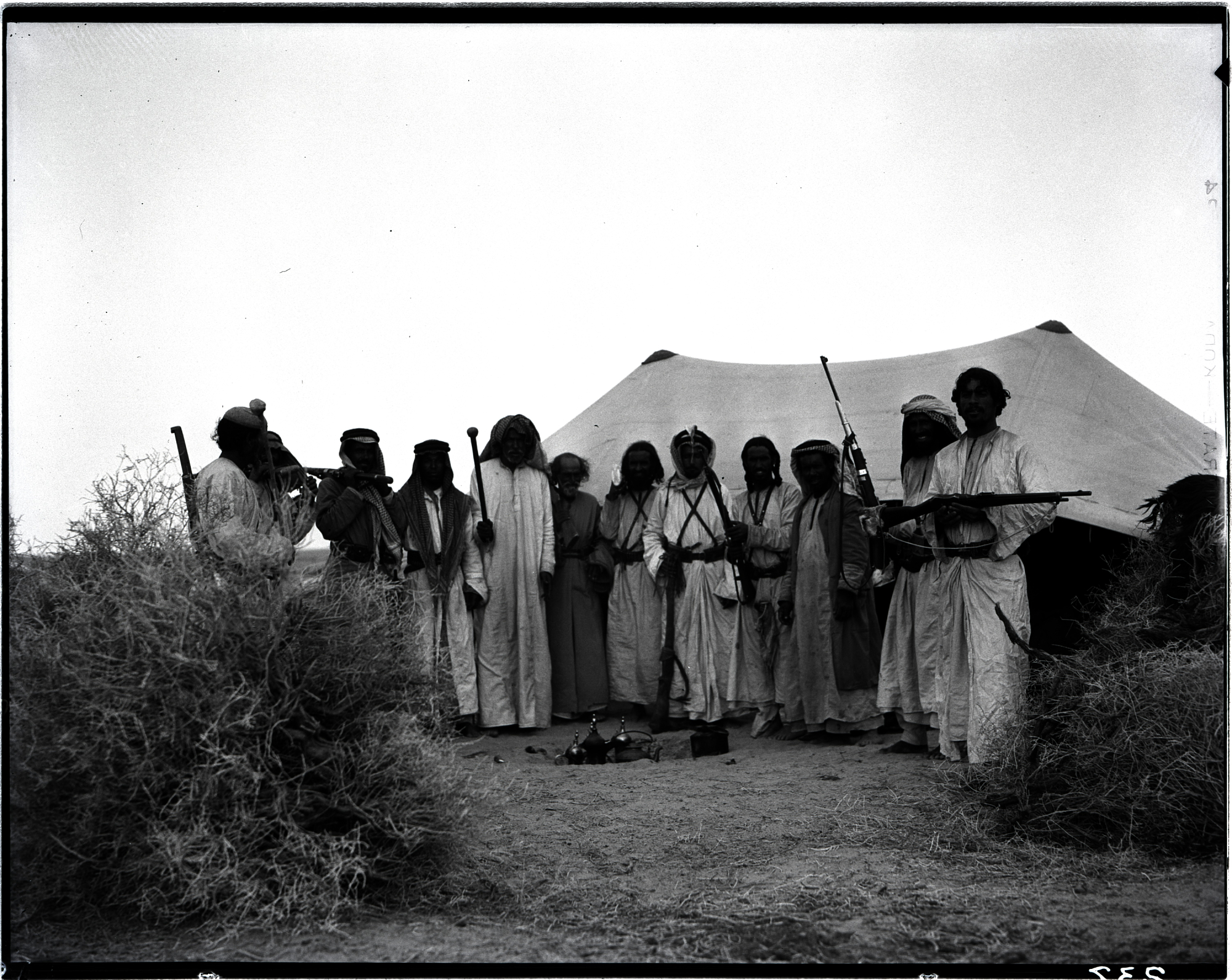

It was common for the 18th and 19th century European historians, scholars, travellers and diplomats to compare the Wahhabi movement with various Euro-American socio-political movements in the Age of Revolutions. Calvinism, Calvinist scholar Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, John Ludwig Burckhardt, author of the well-received works “''Travels in Arabia''” (1829) and “''Notes on the Bedouins and Wahábys''” (1830), described the ''Muwahhidun'' as Arabian locals who resisted Turkish hegemony and its “Napoleonic tactics, Napoleonic” tactics. Historian Loius Alexander Corancez in his book “''Histoire des Wahabis''” described the movement as an Asiatic revolution that sought a powerful revival of Arab civilisation by establishing a new order in Arabia and cleansing all the irrational elements and superstitions which had been normalised through Sufi excesses from Turkish and foreign influences. Scottish people, Scottish historian Mark Napier (historian), Mark Napier attributed the successes of Ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab’s revolution to assistance from “frequent interpositions of Heaven".

With the Dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, Wahhabis were able spread their political power and consolidate their rule over the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina. After the discovery of petroleum near the Persian Gulf in 1939, Saudi Arabia had access to oil export revenues, revenue that grew to billions of dollars. This moneyspent on books, media, schools, universities, mosques, scholarships, fellowships, lucrative jobs for journalists, academics and

Islamic scholarsgave Wahhabi ideals a "preeminent position of strength" in Islam around the world.

However, in the last couple of decades of the twentieth century several crises worked to erode Wahhabi "credibility" in Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Muslim worldthe Iranian Revolution, Iranian revolution of 1979; Soviet–Afghan War, Soviet invasion of Afghanistan (1979); November Grand Mosque seizure, 1979 seizure of the Grand Mosque by militants; the deployment of US troops in Saudi Arabia during the 1991 Gulf War against Iraq; and the September 2001 attacks, September 11, 2001 al-Qaeda attacks on New York and Washington.

[.] In each case the Wahhabi ''ulama'' were called on to support the dynasty's efforts to suppress religious dissent from Jihadists and in each case it did;

exposing its dependence on the Saudi dynasty and its often unpopular policies.

Muhammad ibn 'Abd-al-Wahhab

The patronym of Wahhabism, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, Muhammad ibn ʿAbd-al Wahhab, was born around 1702–03 in the small oasis town of 'Uyayna in the Najd region, in what is now central Saudi Arabia. As part of his scholarly training, Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab travelled in his youth to various Islamic centres in Arabia and Iraq, seeking knowledge. He travelled to Mecca and Medina to perform ''Hajj'' and studied under notable hadith scholars. After completing his studies, he travelled to Iraq and returned to his hometown in 1740. During these travels, Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab had studied various religious disciplines such as ''Fiqh'', theology, philosophy and Sufism. Exposure to various rituals and practices centered on the cult of saints would lead Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab to grow critical of various superstitious practices and accretions common among Sufis, by the time of his return to 'Uyaynah. Following the death of his father, Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab publicly began his religious preaching.

When Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab began preaching his ''dawah'' in the regions of Central Arabia, where various beliefs and practices related to veneration of Wali, Muslim saints and Superstitions in Muslim societies, superstitions were prevalent among Muslims, he was initially rejected and called a "deviant".

Later, however, his call to ''dawah'' became increasingly popular. Realising the significance of efficient and charismatic religious preaching (''

da'wa

Dawah ( ar, دعوة, lit=invitation, ) is the act of inviting or calling people to embrace Islam. The plural is ''da‘wāt'' (دَعْوات) or ''da‘awāt'' (دَعَوات).

Etymology

The English term ''Dawah'' derives from the Arabic ...

''), Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab called upon his students to master the path of reasoning and proselytising over warfare to convince other Muslims of their reformist ideals. Thus, Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab carried out his reforms in a manner that reflected the socio-political values of the Arabian Bedouins to accommodate local sentiments.

According to Islamic beliefs, any act or statement that involves worship to any being other than God and associates other creatures with God's power is tantamount to idolatry (''Shirk (Islam), shirk''). The core of the controversy between Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab and his adversaries was over the scope of these acts. According to Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab, those who made acts of devotion such as seeking aid (''istigatha'') from objects, tombs of dead Muslim saints (''

Awliyaa''), etc. were Zandaqa, heretics guilty of ''

bidʻah

In Islam, bid'ah ( ar, بدعة; en, innovation) refers to innovation in religious matters. Linguistically, the term means "innovation, novelty, heretical doctrine, heresy".

In classical Arabic literature ('' adab''), it has been used as a fo ...

'' (religious innovation) and ''Shirk (Islam), shirk'' (polytheism). Reviving Ibn Taymiyya's approach to ''Takfir, takfīr'' (excommunication), Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab declared those who adhered to these practices to be either Kafir, infidels (''kuffār'') or Munafiq, false Muslims (''munāfiḳūn''), and therefore deemed them Capital punishment in Islam, worthy of death for their perceived Apostasy in Islam, apostasy (''ridda'').

Those Muslims that Takfiri, he accused to be heretics or infidels would not be killed outright; first, they would be given a chance to repent. If they repented their repentance was accepted, but if they didn't repent after the clarification of proofs they were executed under the Capital punishment in Islam, Islamic death penalty as Apostasy in Islam, apostates (''murtaddin'').

[.]

Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab was a major proponent of the ''

'Udhr bil Jahl'' (excuse of ignorance) doctrine, wherein any person unaware of core Islamic teachings had to be excused until clarification. As per this doctrine, those who fell into beliefs of ''shirk'' (polytheism) or ''kufr'' (disbelief) are to be excommunicated only if they have direct access to Scriptural evidences and get the opportunity to understand their mistakes and retract. Hence he asserted that education and dialogue was the path forward and forbade his followers from engaging in reckless accusations against their opponents. Following this principle, Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab delegated the affairs of his enemies to God and in various instances, withheld from fighting them.

The doctrines of Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab were criticized by a number of

Islamic scholars during his lifetime, accusing him of disregarding Islamic history, monuments, traditions and the sanctity of Muslim life. His critics were mainly ''ulama'' from his homeland, the Najd region of central Arabia, which was directly affected by the growth of the Wahhabi movement,

based in the cities of Basra, Mecca, and Medina.

His beliefs on the superiority of direct understanding of Scriptures (''Independent legal reasoning in Islamic law, Ijtihad'') and rebuke of ''Taqlid'' (blindfollowing past legal works) also made him a target of the religious establishment. For his part, Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab criticised the nepotism and corruption prevalent in the clerical class.

The early opponents of Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab classified his doctrine as a "Kharijites, Kharijite Sectarianism, sectarian Heresy in Islam, heresy". By contrast, Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab profoundly despised the "decorous, arty tobacco-smoking, music happy, drum pounding, Egypt Eyalet, Egyptian and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman nobility who traveled across Arabia to pray at Mecca each year",

and intended to either subjugate them to his doctrine or overthrow them.

He further rejected and condemned allegations charged against him by various critics; such as the claim of ''Takfir'' (excommunication) on those who opposed him or did not emigrate to the lands controlled by ''Muwahhidun''. Responding to the accusations brought against him, Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab asserted:

"as for the lie and slander, like their saying that we make generalized ''takfīr'', and that we make Hijrah, emigration obligatory towards us,. .. All of this is from lying and slander by which they hinder the people from the religion of Allāh and His Muhammad in Islam, Messenger. And when it is the case that we do not make ''takfir'' of those who worship the idol which is on the grave of Abdul Qadir Gilani, 'Abd al-Qadir, or the idol upon the grave of Ahmad al-Badawi; and their likes – due to their ignorance and an absence of one to caution them – how could we then make ''takfir'' of those who does not commit ''shirk'', when they do not migrate to us, nor make ''takfir'' of us, nor fight us?"

With the support of the ruler of the townUthman ibn Mu'ammarIbn 'Abd al-Wahhab carried out some of his religious reforms in 'Uyayna, including the demolition of the tomb of Zayd ibn al-Khattab, one of the ''Sahaba'' (companions) of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and the Stoning in Islam, stoning to death of an Zina, adulterous woman after her self-confession. However, a more powerful chief (Sulaiman ibn Muhammad ibn Ghurayr) pressured Uthman ibn Mu'ammar to expel him from 'Uyayna.

Alliance with the House of Saud

The ruler of a nearby town,

Muhammad ibn Saud

Muhammad bin Saud Al Muqrin ( ''Muḥammad bin Suʿūd Āl Muqrin''; 1687–1765), also known as Ibn Saud, was the emir of Diriyah and is considered the founder of the First Saudi State and the Saud dynasty, which are named for his father, Sau ...

, invited Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab to join him, and in 1744 a pact was made between the two.

[.] Ibn Saud would protect and propagate the doctrines of the Wahhabi mission, while Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab "would support the ruler, supplying him with 'glory and power'". Whoever championed his message, Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab promised, "will, by means of it, rule the lands and men".

Ibn Saud would abandon non-''Sharia, shari'i'' practices such as taxations of local harvests, and in return God might compensate him with booty from conquest and ''sharia'' compliant taxes that would exceed what he gave up.

The alliance between the Wahhabi mission and House of Saud, Al Saud family has "endured for more than two and half centuries", surviving defeat and collapse.

The two families have intermarried multiple times over the years, and in today's Saudi Arabia the minister of religion is always a member of the Al ash-Sheikh family, i.e. a descendant of Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab.

According to

Natana J. DeLong-Bas, Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab was restrained in urging fighting with perceived Kafir, unbelievers, preferring to preach and persuade rather than attack. Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab followed a non-interference policy in Ibn Saud's state consolidation project. While Ibn Saud was in charge of political and military issues, he promised to uphold Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab's religious teachings. However, the military campaigns of Ibn Saud weren't necessarily met with approval by Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab. Delineating the specific roles of ''Emir, Amir'' (political leader) and ''Imam'' (religious leader), Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab stipulated that only the ''imam'' (religious leader) could declare the military campaign as ''jihad'' after meeting the legal religious stipulations.

[.] Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab had only authorized ''jihad'' when the Wahhabi community were attacked first, as a defensive measure. His main objective was religious reformation of Muslim beliefs and practices through a gradual educational process. With those who differed with his Islah, reformist ideals, Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab called for dialogue and sending invitations to religious discussions and debates, rather than a "convert or die" approach. Military resort was a last-case option; and when engaged in rarely, it abided by the strict Islamic legal codes.

Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhāb and his supporters held that they were the victims of aggressive warfare; accusing their opponents of starting the pronouncements of ''Takfir'' (excommunication) and maintained that the military operations of Emirate of Diriyah, Emirate of Dirʿiyya were strictly defensive. The memory of the unprovoked military offensive launched by Dahhām ibn Dawwās (fl. 1187/1773), the powerful chieftain of Riyadh, on Diriyya in 1746 was deeply engrained in the Wahhabi tradition and it was the standard claim of the movement that their enemies were the first to pronounce ''Takfir'' and initiate warfare. Prominent Qadi of Emirate of Nejd, Emirate of Najd (Second Saudi state) and grandson of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab, Abd al-Rahman ibn Hassan Al ash-Sheikh, Aal al-Shaykh, (1196–1285 A.H / 1782–1868 C.E) describes the chieftain Dahhām as the first person who launched an unprovoked military attack on the Wahhābīs, aided by the forces of the strongest town in the region. Early Wahhabi chronicler Ibn Ghannām states in his book ''Tarikh an-Najd'' (History of Najd) that Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhāb did not order the use of violence until his enemies excommunicated him and deemed his blood licit:

"He gave no order to spill blood or to fight against the majority of the heretics and the misguided until they started ruling that he and his followers were to be killed and excommunicated."

Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab consistently elucidated through his writings that his Jihad was only defensive and was intended to safeguard the community from external attacks; with the ultimate objective of restoring peace and defend the Islamic faith. Killings on non-combatant civilians were strictly prohibited and all expansionist wars intended for wealth or power were condemned.

However, after the death of Muhammad ibn Saud in 1765, his son and successor, Abdulaziz bin Muhammad, began military exploits to extend Saudi power and expand their wealth, abandoning the educational programmes of the Islah, reform movement and setting aside Islamic religious constraints on war. Due to disagreements, Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab would resign his position as ''imam'' and retire from overt political and financial career in 1773. He abstained from legitimising Saudi military campaigns; dedicating the rest of his life for educational efforts and in zuhd, asceticism.

Conflicts with British and Ottoman Empires

After Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab's death, Abdulaziz continued with his expansionist vision beyond the confines of Najd. Conquest expanded through the Arabian Peninsula until it conquered Mecca and Medina in the early 19th century.

It was during this time that the Saudi political leadership began to emphasise the doctrine of offensive Jihad by reviving the ''fatwas'' of the medieval

Hanbali

The Hanbali school ( ar, ٱلْمَذْهَب ٱلْحَنۢبَلِي, al-maḏhab al-ḥanbalī) is one of the four major traditional Sunni schools (''madhahib'') of Islamic jurisprudence. It is named after the Arab scholar Ahmad ibn Hanbal ...

te theologian Ibn Taymiyyah, Taqi al-Din Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328 C.E/ 728 A.H). Ibn Taymiyya had declared self-professed Muslims who do not strictly adhere to Sharia, Islamic law or practised various acts of saint-veneration such as beseeching favours from the dead to be non-Muslims. More significantly, Ibn Taymiyya pronounced ''Takfir'' (excommunication) on regimes that didnt implement Sharia, Shari'a (Islamic laws) and called for Muslims to unseat such rulers through armed Jihad. These ''fatwas'' were readily incorporated by Wahhabi clerics to justify Saudi military campaigns into Hejaz against the Sharif of Mecca, Sharifs of Mecca.

[.] One of their most noteworthy and controversial attacks was on the Shia-majority city of Karbala in 1802. According to Wahhabi chronicler 'Uthman b. 'Abdullah b. Bishr; the Saudi armies killed many of its inhabitants, plundered its wealth and distributed amongst the populace. By 1805, the Saudi armies had taken control of Mecca and Medina.

As early as the 19th century, the newly ascending Ottoman-Saudi conflict had pointed to a clash between two national identities. In addition to doctrinal differences, Wahhabi resentment of Ottoman Empire was also based on Pan-Arabism, pan-Arab sentiments and reflected concerns over the contemporary state of affairs wherein Arabs held no political sovereignty. Wahhabi poetry and sources demonstrated great contempt for the Turkish nationalism, Turkish identity of the Ottoman Empire. While justifying their wars under religious banner, another major objective was to replace Turkish hegemony with the rule the Arabs. During this period, the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

had also come into conflict with the Wahhabis. British commercial interests in the Persian Gulf, Gulf region were being challenged by "pirate" tribes who had sworn Bay'ah, allegiance to the Emirate of Dirʿiyya. The early 19th century was also marked by the emergence of British naval hegemony in the Gulf Region, Gulf region. The ideals of the ''Muwahhidun'' provided theological inspiration for various Arabian Peninsula, Arabian sultanates for declaring armed ''Jihad'' against the rising colonial encroachment. Numerous naval attacks against the British Arabian Peninsula, Royal navy were successfully conducted by Wahhabi armadas stationed in the Gulf.

The anti-Wahhabi propaganda of British had also affected Ottoman authorities; perceiving them as a rising challenge to their hegemony. The Ottoman Empire, suspicious of the ambitious Muhammad Ali of Egypt, instructed him to fight the Wahhabis, as the defeat of either would be beneficial to them.

[Afaf Lutfi al-Sayyid-Marsot. ''A History of Egypt From the Islamic Conquest to the Present.'' New York: Cambridge UP, 2007.] Tensions between Muhammad Ali of Egypt, Muhammad Ali and his troops also prompted him to send them to Arabia and fight against the Emirate of Diriyah where many were massacred. This led to the Wahhabi War, Ottoman-Saudi War.

Egypt Eyalet, Ottoman Egypt, led by Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt, Ibrahim Pasha, was eventually successful in defeating the Saudis in a campaign starting from 1811. In 1818 they defeated Al Saud, leveling the capital Diriyah, slaughtering its inhabitants, executing the Al-Saud emir and exiling the emirate's political and religious leadership,

and unsuccessfully attempted to stamp out not just the House of Saud but the Wahhabi mission as well.

The

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

welcomed Ibrahim Pasha's Siege of Diriyah, destruction of Diriyah with the goal of promoting trade interests in the region. Captain George Forster Sadleir, an officer of the British Army in Company rule in India, India was dispatched from Bombay Presidency, Bombay to consult with Ibrahim Pasha in Diriyah. The fall of Emirate of Dirʿiyya also enabled the British empire to launch their Persian Gulf campaign of 1819. A major military expedition was sent to fight Diriyah-allied Qawasim dynasty and their domain Emirate of Ras Al Khaimah, Ras al Khaimah was destroyed in 1819. General Maritime Treaty of 1820, The General Maritime treaty was concluded in 1820 with the local chieftains, which would eventually transform them into a protectorate of Trucial States; heralding a century of British supremacy in the Persian Gulf, Gulf.

Second Saudi State (1824–1891)

A second, smaller Saudi state, the Emirate of Nejd, lasted from 1824 to 1891. Its borders being within Najd; Wahhabism was protected from further Ottoman or Egyptian campaigns by Najd's isolation, lack of valuable resources, and that era's limited communication and transportation.

[.] By the 1880s, at least amongst the townsmen if not Bedouins of Saudi Arabia, Arabian Bedouins, Wahhabism had become the predominant religious culture of the regions in Najd.

Unlike early leaders like Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab and his son Abdullah bin Muhammad Al Sheikh, 'Abdullah who had advocated dialogue and education as the most effective approach to reformation; the later scholars of the ''Muwahhidun'' preferred a militant approach. Following the Ottoman Siege of Diriyah, destruction of Diriyah and suppression of reformist trends regarded as a threat to the religious establishment, the later ''Muwahhidun'' launched a decades long insurgency in Central Arabia and became radicalised. Absence of capable scholarship after the death of Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab in 1792, also marked this shift. In this era, the ''Muwahhidun'' revived many ideas of the medieval theologian Ibn Taymiyya, including doctrines such as ''Al-Wala' wal-Bara', Al-Wala wal Bara'' (loyalty and disassociation) which conceptualised a binary division of world into believers and non-believers. Whilst this phrase was absent in the 18th century Wahhabi literature, it became a central feature of the 19th century Wahhabi dogma.

Thus, during much of the second half of the 19th century, there was a strong aversion to mixing with "idolaters" (including most of the inhabitants of the Muslim world) in Wahhabi lands. At the very least, voluntary contact was considered sinful by Wahhabi clerics, and if one enjoyed the company of idolaters, and "approved of their religion", it was considered an act of Kafir, unbelief. Travel outside the pale of Najd to the Ottoman lands "was tightly controlled, if not prohibited altogether". Over the course of their history, the ''Muwahhidun'' became more accommodating towards the outside world. In the late 1800s, Wahhabis found other Muslims with similar beliefsfirst with ''

Ahl-i Hadith'' in South Asia, and later with Islamic revivalists in Arab states (one being Mahmud Sahiri al-Alusi in Baghdad).

Around this period, many remote tribes of Central Arabia re-introduced the practice of idolatry and superstitious folk rituals. During his official visit to Arabia in 1865, British Empire, British Lieutenant general, Lieutenant General Lewis Pelly noted that most of the Central Arabian tribes were ignorant of basic Islamic tenets and were practising animism. Finnish explorer Georg August Wallin, George August Wallin who travelled Northern Arabia during the 1840s writes in his ''Notes'' (1848):

"most of the tribes which were not forced to adopt the Islah, reformed doctrines of the Wahhâbiyé (Wahábiyeh) sect during the period of its ascendant power in Arabian Peninsula, Arabia... are, in general, grossly ignorant in the religion they profess, and I scarcely remember ever meeting with a single individual... who observed any of the rites of Islam, Islâm whatever, or possessed the last notion of its fundamental and leading dogmas; while the reverse might, to a certain degree, be said of those Bedouin, Bedooins who are, or formerly were, Wahhâbiyé (Wahábiyeh)."

'Abd Al Aziz Ibn Saud

In 1901, Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia, 'Abd Al-aziz Ibn Saud, a fifth generation descendant of Muhammad ibn Saud, began a military campaign that led to the conquest of much of the Arabian peninsula and the founding of present-day Saudi Arabia, after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. During this period, the Wahhabi scholars began allying with the cause of the Sunni Islah, reformist ''ulema'' of the Arab East, such as Jamal al-Din Qasimi, Tahir al-Jazairi, Tahir al Jaza'iri, Khayr al-Din Alusi, etc. who were major figures of the early ''Salafiyya'' movement. The revivalists and Wahhabis shared a common interest in Ibn Taymiyya's thought, the permissibility of ''

ijtihad'', and the need to purify worship practices of innovation. In the 1920s, Rashid Rida, Sayyid Rashid Rida (d. 1935 C.E/ 1354 A.H), a pioneer Arab Salafist whose periodical ''Al-Manār (magazine), al-Manar'' was widely read in the Muslim world, published an "anthology of Wahhabi treatises", and a work praising the Ibn Saud as "the savior of the Haramain, ''Haramayn'' [the two holy cities] and a practitioner of authentic Islamic rule".

[.]

The core feature of Rida's treatises was the call for revival of the pristine Islamic beliefs and practices of the ''

Salaf

Salaf ( ar, سلف, "ancestors" or "predecessors"), also often referred to with the honorific expression of "al-salaf al-ṣāliḥ" (, "the pious predecessors") are often taken to be the first three generations of Muslims. This comprises Muhamm ...

'' and glorification of the early generations of

Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...

, and condemnation of every subsequent ritual accretion as ''Bidʻah, bid'ah'' (religious heresy). Reviving the fundamentalist teachings of classical Hanbali theologians Ibn Taymiyya and

Ibn Qayyim

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr ibn Ayyūb al-Zurʿī l-Dimashqī l-Ḥanbalī (29 January 1292–15 September 1350 CE / 691 AH–751 AH), commonly known as Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya ("The son of the principal of he school ...

, Rida also advocated the political restoration of an Caliphate, Islamic Caliphate that would unite the Ummah, Muslim Ummah as necessary for maintaining a virtous Islamic society. Rashid Rida's campaigns for

pan-Islamist

Pan-Islamism ( ar, الوحدة الإسلامية) is a political movement advocating the unity of Muslims under one Islamic country or state – often a caliphate – or an international organization with Islamic principles. Pan-Islamism w ...

revival through Ibn Taymiyya's doctrines would grant Wahhabism mainstream acceptance amongst the cosmopolitan Arab elite, once dominated by Ottomanism.

Under the reign of Ibn Saud, Abdulaziz, "political considerations trumped" doctrinal idealism favored by pious Wahhabis. His political and military success gave the Wahhabi ulama control over religious institutions with jurisdiction over considerable territory, and in later years Wahhabi ideas formed the basis of the rules and laws concerning social affairs, and shaped the kingdom's judicial and educational policies.

But protests from Wahhabi ''ulama'' were overridden when it came to consolidating power in Hijaz and al-Hasa, maintaining a positive relationship with the Government of the United Kingdom, British government, adopting modern technology, establishing a simple governmental administrative framework, or signing an oil concession with the U.S. The Wahhabi ulama also issued a fatwa affirming that "only the ruler could declare a jihad" (a violation of Ibn Abd al-Wahhab's teaching, according to DeLong-Bas).

As the realm of Wahhabism expanded under Ibn Saud into Shia Islam, Shiite areas (Al-Ahsa Oasis, al-Hasa, conquered in 1913) and Hejaz (conquered in 1924–25), radical factions amongst Wahhabis such as the ''Ikhwan'' pressed for forced conversion of Shia and an eradication of (what they saw as) idolatry. Ibn Saud sought "a more relaxed approach".

[.] In al-Hasa, efforts to stop the observance of Shia religious holidays and replace teaching and preaching duties of Shia clerics with Wahhabi, lasted only a year. In Mecca and Jeddah (in Hejaz) prohibition of tobacco, alcohol, playing cards and listening to music on the phonograph was looser than in Najd. Over the objections of some of his clergymen, Ibn Saud permitted both the driving of automobiles and the attendance of Shia at hajj. Enforcement of the commanding right and forbidding wrong, such as enforcing prayer observance, Islam and gender segregation, Islamic sex-segregation guidelines, etc. developed a prominent place during the Third Saudi emirate, and in 1926 a formal committee for enforcement was founded in Mecca.

Ikhwan rebellion (1927–1930)

While Wahhabi warriors swore loyalty to monarchs of Al Saud, there was one major rebellion. King Abd al-Azez put down rebelling ''Ikhwan revolt, Ikhwan''nomadic tribesmen turned Wahhabi warriors who opposed his "introducing such innovations as telephones, automobiles, and the telegraph" and his "sending his son to a country of unbelievers (Egypt)". Britain had warned Abd al-aziz when the ''Ikhwan'' attacked the British protectorates of Emirate of Transjordan, Transjordan, Iraq and Kuwait, as a continuation of jihad to expand the Wahhabist realm.

''Ikhwan'' consisted of Bedouin tribesmen who believed they were entitled to free-lance ''Jihad'', raiding, etc. without permission of the ''Amir'' and they had conflicts with both Wahhabi ''Ulama, ulema'' and Saudi rulers. They also objected to Saudi taxations on nomadic tribes. After their raids against Saudi townsmen, Ibn Saud went for a final showdown against the ''Ikhwan'' with the backing of the Wahhabi ''ulema'' in 1929. The Ikhwan was decisively defeated and sought the backing of foreign rulers of Kuwait and

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. In January 1930, the main body of ''Ikhwan'' surrendered to the British near the Saudi-Kuwaiti border. The Wahhabi movement was perceived as an endeavour led by the settled populations of the Arabian Peninsula against the nomadic domination of trade-routes, taxes as well as their ''Jahiliyyah, jahiliyya'' customs. Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab had criticized the nomadic tribes and the Wahhabi chroniclers praised Saudi rulers for taming the Bedouins.

Establishment of Saudi Arabia

In a bid "to join the Muslim mainstream and to erase the reputation of extreme sectarianism associated with the ''Ikhwan''", in 1926 Ibn Saud convened a Muslim congress of representatives of Muslim governments and popular associations.

[.] By 1932, 'Abd al-Azeez and his armies were able to efficiently quell all rebellions and establish unchallenged authority in most regions of the Peninsula such as Hejaz, Najd, Nejd and 'Asir Province, Asir. After holding a special meeting of the members of ''Majlis al-Shura'' ( consultation council), 'Abd al-Azeez ibn Saud issued the decree "''On the merger of the parts of the Arabian kingdom''" on 18 September 1932; which announced the establishment of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the fourth and current iteration of the Third Saudi State. Upon his death in 1953, Ibn Saud had implemented various modernisation reforms and technological innovations across the country; tempering the 19th century Wahhabi zeal. Acknowledging the political realities of the 20th century, a relenting Wahhabi scholarly establishment opened up to the outside world and attained religious acceptance amongst the wider Ummah, Muslim community.

Wahhabi ''ulama'' gained control over education, law, public morality and religious institutions in the 20th century; while incorporating new material and technological developments such as the import of modern communications; for the political consolidation of the Al-Saud dynasty and strengthening Saudi Arabia, the country that advocated Wahhabi doctrines as state policy.

[.]

Alliance with Islamists

A major current in regional politics at that time was Secularism, secular nationalism, which, with Gamal Abdel Nasser, was sweeping the Arab world. To combat it, Wahhabi missionary outreach worked closely with Saudi foreign policy initiatives. In May 1962, a conference in Mecca organized by Saudis discussed ways to combat secularism and socialism. In its wake, the World Muslim League was established.

[.] To propagate Islam and "repel inimical trends and dogmas", the League opened branch offices around the globe.

[.] It developed closer association between Wahhabis and leading Salafi movement, Salafis, and made common cause with the Islamic revivalist Muslim Brotherhood, ''

Ahl-i Hadith'' and the Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan, Jamaat-i Islami, combating Sufism and "innovative" popular religious practices

and rejecting the West and Western "ways which were so deleterious of Muslim piety and values".