William Young (Royal Navy Officer, Born 1751) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir William Young GCB (16 August 1751 – 25 October 1821) was an officer of the

Young continued to serve with Hood's forces, and was active in the sieges of

Young continued to serve with Hood's forces, and was active in the sieges of

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

who saw service during the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, and the French Revolutionary

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are consider ...

and Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. He should not be confused with his namesake and near contemporary Admiral William Young.

Young was born into a naval family, with his father, James Young, and his half-brother, James Young also serving in the navy and rising to flag rank. William Young served on a variety of ships and rose to his own commands during the American War of Independence. Using his connections to continue in service during the years of peace, he was almost immediately given command of a ship on the outbreak of the wars with the France and served initially in the Mediterranean during the siege of Toulon

The siege of Toulon (29 August – 19 December 1793) was a military engagement that took place during the Federalist revolts of the French Revolutionary Wars. It was undertaken by Republican forces against Royalist rebels supported by Anglo-Spa ...

, at the reduction of Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

, and at the battles of Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

and Hyères Islands

Hyères (), Provençal Occitan: ''Ieras'' in classical norm, or ''Iero'' in Mistralian norm) is a commune in the Var department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region in southeastern France.

The old town lies from the sea clustered around th ...

. Promoted to flag rank soon after these events, he returned to England and joined the Board of Admiralty

The Board of Admiralty (1628–1964) was established in 1628 when Charles I put the office of Lord High Admiral into commission. As that position was not always occupied, the purpose was to enable management of the day-to-day operational requi ...

.

He rose through the ranks during his time in office, serving in his official capacity during the Spithead and Nore mutinies

The Spithead and Nore mutinies were two major mutinies by sailors of the Royal Navy in 1797. They were the first in an increasing series of outbreaks of maritime radicalism in the Atlantic World. Despite their temporal proximity, the mutinies d ...

, as commander at Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

, and as senior officer during the court martial of Lord Gambier

Admiral of the Fleet (Royal Navy), Admiral of the Fleet James Gambier, 1st Baron Gambier, (13 October 1756 – 19 April 1833) was a Royal Navy officer. After seeing action at the capture of Charleston, South Carolina, Charleston during the Ameri ...

after the Battle of the Basque Roads

The Battle of the Basque Roads, also known as the Battle of Aix Roads ( French: ''Bataille de l'île d'Aix'', also ''Affaire des brûlots'', rarely ''Bataille de la rade des Basques''), was a major naval battle of the Napoleonic Wars, fought in t ...

. He returned to an active command at sea in 1811 with responsibility for blockading the Dutch coast until the end of the war. He received further promotions, and reached the rank of Admiral of the Red

The Admiral of the Red was a senior rank of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom, immediately outranked by the rank Admiral of the Fleet (see order of precedence below). The rank did not exist prior to 1805, as the admiral commanding the Red ...

, with the position of Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom

The Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom is an honorary office generally held by a senior Royal Navy admiral. The title holder is the official deputy to the Lord High Admiral, an honorary (although once operational) office which was vested in th ...

before his death in 1821.

Family and early life

Young was born on 16 August 1751, the eldest of five children of James Young, himself a distinguished naval officer who rose to the rank ofadmiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

, and his wife Elizabeth. Elizabeth died sometime before 1762, and his father married Sophia Vasmer, having at least two children. The eldest son by his second marriage, James

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

, also embarked on a naval career and became a rear-admiral of the blue. William Young entered the navy in April 1761, joining the 50-gun under Captain Mark Milbanke

Admiral Mark Milbanke (12 April 1724 – 9 June 1805) was a British naval officer and colonial governor.

Military career

Milbanke was born into an aristocratic Yorkshire family with naval connections, his father was Sir Ralph Milbanke, 4th Bar ...

as captain's servant. He joined the 8-gun in December 1762, but rejoined ''Guernsey'' in October 1764. The ''Guernsey'' was by now under Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore, a ...

Hugh Palliser

Admiral Sir Hugh Palliser, 1st Baronet (26 February 1723 – 19 March 1796) was a Royal Navy officer. As captain of the 58-gun HMS ''Eagle'' he engaged and defeated the French 50-gun ''Duc d'Aquitain'' off Ushant in May 1757 during the Seven Y ...

. Young took and passed his lieutenant's examination on 10 January 1769, and received his promotion on 12 November 1770 with a posting to the 16-gun , which was then at Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

.

He joined the 64-gun , which was then in the Mediterranean as the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

of Sir Peter Denis, as her fourth lieutenant. He served aboard her for several years, until becoming third lieutenant of the 50-gun on 23 January 1775. The ''Portland'' was at the time his father's flagship, at the Leeward Islands

french: Îles-Sous-le-Vent

, image_name =

, image_caption = ''Political'' Leeward Islands. Clockwise: Antigua and Barbuda, Guadeloupe, Saint kitts and Nevis.

, image_alt =

, locator_map =

, location = Caribbean SeaNorth Atlantic Ocean

, coor ...

. Service in the American War of Independence created opportunities for aspiring young officers, and he received his first command, that of the sloop , on 10 May 1777. The post was confirmed on 23 September 1778, and the same day he was again promoted and made captain of the 24-gun . He moved to take over the 32-gun on 15 April 1782, and remained with her until the end of the war. He remained on active service during the peace, surviving the drawdown of the navy to be given command the 36-gun in October 1787. He then briefly commanded the 36-gun from 10 May until November 1790.

French Revolutionary Wars

As war withRevolutionary France

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

approached, the navy expanded, and on 31 January 1793 Young was given command of the 74-gun . He took ''Fortitude'' out to the Mediterranean to join the fleet under Lord Hood, where he took part in the occupation and siege of Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

. With the fall of the city to the republicans, Hood decided to establish a base at Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

. He sent a squadron under Commodore Robert Linzee

Admiral Robert Linzee (1739 – 4 October 1804) was an officer of the Royal Navy who served during the American War of Independence, and the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Linzee entered the navy and was promoted to lieutenant during ...

, and consisting of three ships of the line and two frigates, with troops under Major-General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

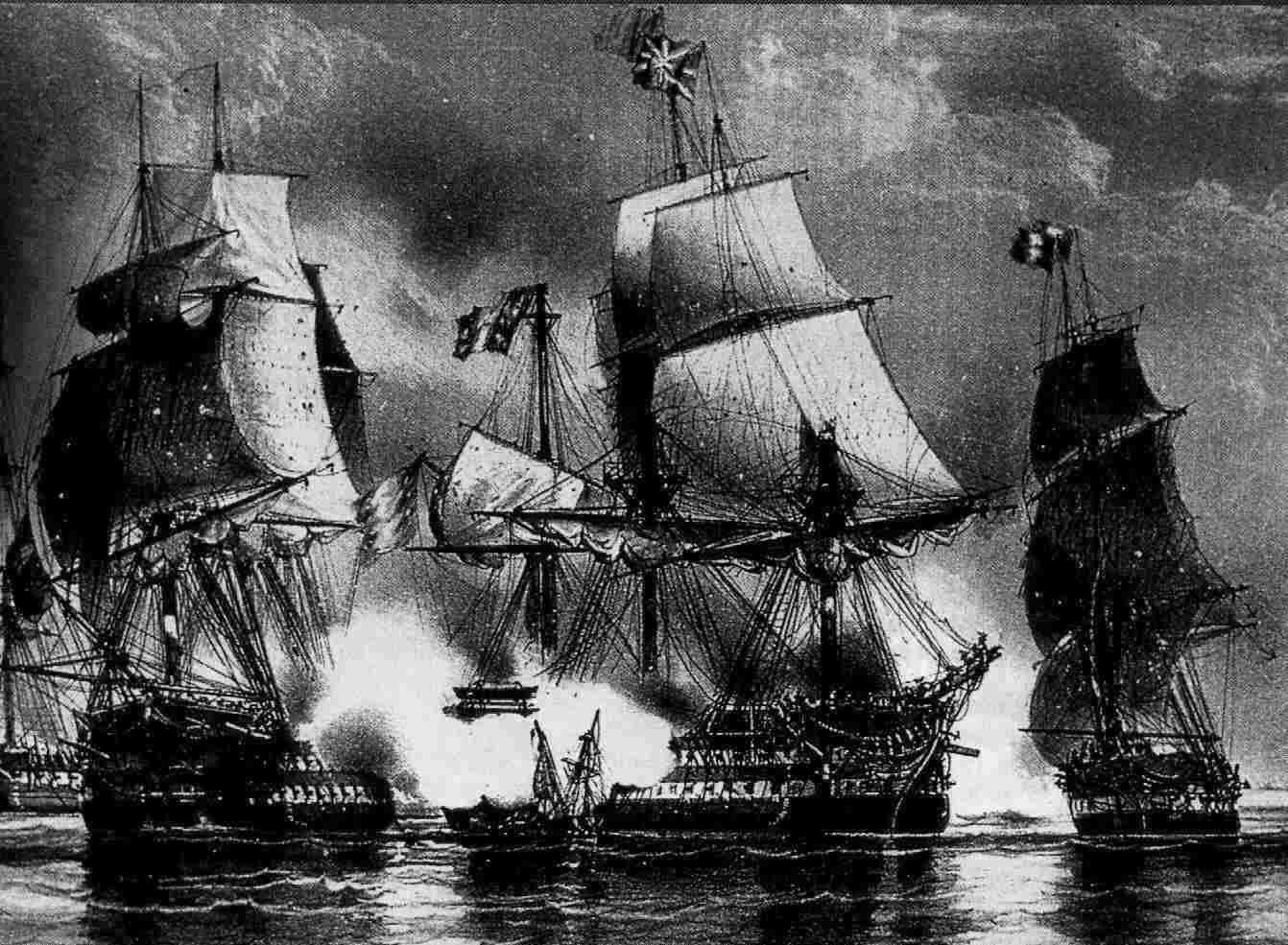

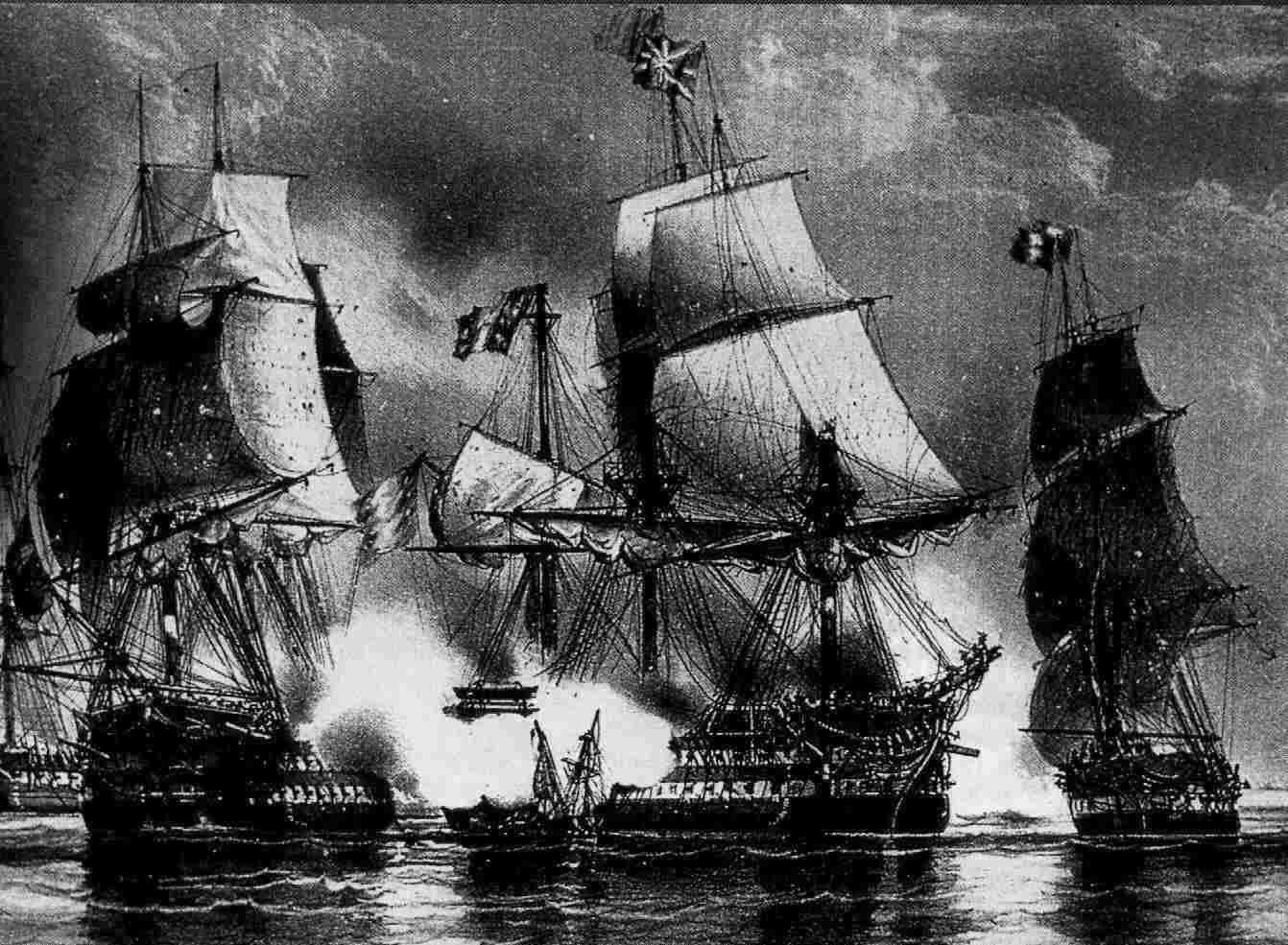

David Dundas, to Mortella Bay. The troops were landed on 7 February 1794, and on 9 February ''Fortitude'' and ''Juno'' were sent to bombard a tower, just south of Pointe de la Mortella. Capturing the tower was necessary to secure the bay, but it proved highly resistant to bombardment, and despite only being armed with one 24-pounder gun, inflicted heavy damage on the British ships. After two hours of bombardment ''Fortitude'' had been nearly set on fire by hot shot, and was forced to retreat with six men killed and fifty-six wounded.

Flag rank and the Board of Admiralty

Young continued to serve with Hood's forces, and was active in the sieges of

Young continued to serve with Hood's forces, and was active in the sieges of Bastia

Bastia (, , , ; co, Bastìa ) is a commune in the department of Haute-Corse, Corsica, France. It is located in the northeast of the island of Corsica at the base of Cap Corse. It also has the second-highest population of any commune on the is ...

and Calvi, being awarded the honorary rank of colonel of marines on 4 July 1794. He was present with the fleet at the Battle of Genoa

The Battle of Genoa (also known as the Battle of Cape Noli and in French as ''Bataille de Gênes'') was a naval battle fought between French and allied Anglo-Neapolitan forces on 14 March 1795 in the Gulf of Genoa, a large bay in the Ligurian ...

on 14 March 1795 and the Battle of Hyères Islands

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

on 13 July 1795 under Vice-Admiral Sir William Hotham. He had been advanced to the rank of rear admiral of the white on 1 June 1795, and returned to England in autumn that year escorting a convoy. He joined the Board of Admiralty

The Board of Admiralty (1628–1964) was established in 1628 when Charles I put the office of Lord High Admiral into commission. As that position was not always occupied, the purpose was to enable management of the day-to-day operational requi ...

on 20 November, serving as one of the Lords Commissioners

The Lords Commissioners are privy counsellors appointed by the monarch of the United Kingdom to exercise, on his or her behalf, certain functions relating to Parliament which would otherwise require the monarch's attendance at the Palace of Wes ...

until 19 February 1801. He visited Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

in April 1797, during the mutiny there, as part of the committee of conciliation sent by the board. Though professionally Young maintained the official line on the events, privately he appears to have been somewhat sympathetic to the seamen's complaints, and in a letter to Captain Charles Morice Pole

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Charles Morice Pole, 1st Baronet GCB (18 January 1757 – 6 September 1830) was a Royal Navy officer, colonial governor and banker. As a junior officer he saw action at the siege of Pondicherry in India during the Ame ...

remarked that ‘a sad want of energy and of particular attention to duty which the government of large bodies of men requires especially in these times and an absent or indifferent man can produce incalculable mischief’. Consequently, during his tenure at the Admiralty he tried to improve conditions and tighten discipline.

Command at Plymouth

Young attended the thanksgiving service for the recent naval victories atSt Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

late in 1797. He was promoted to vice-admiral of the blue on 14 February 1799, the second anniversary of Sir John Jervis's victory at the Battle of St Vincent, and was further advanced to vice-admiral of the white on 1 January 1801. He was promoted to vice-admiral of the red on 23 April 1804, and on 18 May was appointed Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth

The Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth, was a senior commander of the Royal Navy for hundreds of years. Plymouth Command was a name given to the units, establishments, and staff operating under the admiral's command. Between 1845 and 1896, this offic ...

. His time at Plymouth was marked with conflict with a junior officer, Lord Cochrane, who accused Young of excessive greed in the matter of prize money

Prize money refers in particular to naval prize money, usually arising in naval warfare, but also in other circumstances. It was a monetary reward paid in accordance with the prize law of a belligerent state to the crew of a ship belonging to t ...

, but this was a common dispute between officers, and Young followed common naval practice in his orders. He was advanced to admiral of the blue on 9 November 1805, but had been suffering ill health and fatigue during his posting and stepped down from his post in 1807. He declined the offer to lead the expedition to the Baltic in 1807, and instead the position was given to Sir James Gambier. He continued in his post as Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth for several more years.

Gambier's court martial

Young was later appointed the senior admiral at the board of the court martial held against Gambier in July 1809, to investigate Gambier's actions at theBattle of the Basque Roads

The Battle of the Basque Roads, also known as the Battle of Aix Roads ( French: ''Bataille de l'île d'Aix'', also ''Affaire des brûlots'', rarely ''Bataille de la rade des Basques''), was a major naval battle of the Napoleonic Wars, fought in t ...

. Gambier's principle critic was Lord Cochrane, who went on to accuse Young of undue bias in Gambier's favour, but Cochrane had already clashed with Young over the matter of prize money, and had accused Young of inefficiency in outfitting ships during his time at Plymouth when Cochrane was MP for Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

. Young did object to Cochrane's discursive answers during the court martial, but does not seem to have been any more hostile than the other members of the board.

Young was advanced to admiral of the white on 31 July 1810 and in spring 1811 he became Commander-in-Chief, North Sea

The Commander-in-Chief, North Sea, was senior appointment and an operational command of the British Royal Navy originally based at Great Yarmouth from 1745 to 1802 then at Ramsgate from 1803 until 1815.

The office holder commanded the North Se ...

. His task was to blockade the Dutch fleet, and he hoisted his flag aboard the 83-gun on his arrival at the Downs on 26 April. The fleet was in good order to carry out the blockade, though afflicted by shortages of men. Young had the support of the First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

, Charles Philip Yorke

Charles Philip Yorke (12 March 1764 – 13 March 1834) was a British politician. He notably served as Home Secretary from 1803 to 1804.

Political career

He sat as a Member of Parliament (MP) for Cambridgeshire from 1790 to 1810.

He was commis ...

, though the blockade proved an arduous task, consisted of constant cruises, with shortages of ships, men and supplies, and the problems of bad weather. He hoped to lure the French fleet out of Flushing

Flushing may refer to:

Places

* Flushing, Cornwall, a village in the United Kingdom

* Flushing, Queens, New York City

** Flushing Bay, a bay off the north shore of Queens

** Flushing Chinatown (法拉盛華埠), a community in Queens

** Flushing ...

, but the French declined to come out. He hoped to be given command of the Channel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history the ...

, but when the appointment was given to Lord Keith

Baron Keith was a title that was created three times in British history, with all three creations in favour of the same person, Admiral the Honourable Sir George Keith Elphinstone. He was the fifth son of Charles Elphinstone, 10th Lord Elphinsto ...

in February 1812, Young felt he had been undermined, and resigned. Yorke persuaded him to return to his command, which he held until the end of the war. He was invested a Knight Companion of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately ...

on 28 July 1814, and with the reconstruction of the order the following year, became a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath on 2 January 1815.

Later years

Young became deputy present of the Naval Charitable Society, andRear-Admiral of the United Kingdom

The Rear-Admiral of the United Kingdom is a now honorary office generally held by a senior (possibly retired) Royal Navy admiral, though the current incumbent is a retired Royal Marine General. Despite the title, the Rear-Admiral of the Unite ...

on 14 May 1814. He was made Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom

The Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom is an honorary office generally held by a senior Royal Navy admiral. The title holder is the official deputy to the Lord High Admiral, an honorary (although once operational) office which was vested in th ...

on 18 July 1819 after the death of Sir William Cornwallis, but by now was troubled by his failing health, and spent November 1818 at Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

. He died, aged 71, at his house in Queen Anne Street, North London, on 25 October 1821 after a short illness.

Assessment

Admiral Sir William Hotham described Young during his time at the Admiralty as being ‘diligent in application, clear in method and generally informed’. Young's biographer, P. K. Crimmin described his command of the Dutch blockade as being 'well performed and praiseworthy', while describing him as a 'conventional upholder and representative of the existing naval social order, though aware of the need for some reform and having some sympathy with seamen's grievances.' His opposition to Cochrane's radicalism and insubordinate attitude to superior officers led to him being harshly criticised by Cochrane's admirers, such as CaptainFrederick Marryat

Captain Frederick Marryat (10 July 1792 – 9 August 1848) was a Royal Navy officer, a novelist, and an acquaintance of Charles Dickens. He is noted today as an early pioneer of nautical fiction, particularly for his semi-autobiographical novel ...

, who included him in his novel ''Frank Mildmay'' as 'Sir Hurricane Humbug'. Sir William Hotham instead declared that his manners 'tho' rather formal and cold, were those of a perfect gentleman, while he had the most punctilious sense of integrity'.

Notes

a. The ships were three 74-gunthird rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the third r ...

s; , carrying Linzee's broad pennant and under Captain Woodley, under J. Dickson, and ''Fortitude'' under Young. Accompanying them were the 32-gun frigates and , under Captains Samuel Hood and William Wolsey respectively.

b. The tower eventually fell to land-based forces under Sir John Moore after two days of heavy fighting. The effectiveness of the tower, when properly supplied and defended, impressed the British, who copied the design for what they would call Martello tower

Martello towers, sometimes known simply as Martellos, are small defensive forts that were built across the British Empire during the 19th century, from the time of the French Revolutionary Wars onwards. Most were coastal forts.

They stand up ...

s.

c. The victories commemorated were Lord Howe's at the Glorious First of June

The Glorious First of June (1 June 1794), also known as the Fourth Battle of Ushant, (known in France as the or ) was the first and largest fleet action of the naval conflict between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the First French Republic ...

, Sir John Jervis's at St Vincent, and Adam Duncan's at Camperdown.

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Young, William 1751 births 1821 deaths Royal Navy admirals Royal Navy personnel of the American Revolutionary War Royal Navy personnel of the French Revolutionary Wars Royal Navy personnel of the Napoleonic Wars Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Lords of the Admiralty