William Wynter (Royal Navy Officer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Admiral Sir William Wynter (c. 1521 – 20 February 1589) was an admiral and principal officer of the

Wynter commanded a fleet to guard against French landings in Scotland in 1559, while diplomatic efforts were made to negotiate sending an English army to aid the Scottish Protestants. After briefing at Gillingham, Wynter left

Wynter commanded a fleet to guard against French landings in Scotland in 1559, while diplomatic efforts were made to negotiate sending an English army to aid the Scottish Protestants. After briefing at Gillingham, Wynter left

Council of the Marine

The Navy Board (formerly known as the Council of the Marine or Council of the Marine Causes) was the commission responsible for the day-to-day civil administration of the Royal Navy between 1546 and 1832. The board was headquartered within the ...

under Queen Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

and served the crown during the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604).

Personal

Wynter was born atBrecknock

Brecon (; cy, Aberhonddu; ), archaically known as Brecknock, is a market town in Powys, mid Wales. In 1841, it had a population of 5,701. The population in 2001 was 7,901, increasing to 8,250 at the 2011 census. Historically it was the count ...

, the son of John Wynter (died 1546 - a merchant and sea captain of Bristol and treasurer of the navy, who was friendly with Sir Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; 1485 – 28 July 1540), briefly Earl of Essex, was an English lawyer and statesman who served as chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false charge ...

) and Alice, daughter of William Tirrey of Cork.

Naval career

William was schooled in the navy. He took part in the 260 ship expedition of 1544, which burnedLeith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by '' Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

and Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, and held the office of Keeper of the King's Storehouse at Deptford Strand. In 1545 he served in Lord Lisle's channel fleet; two years later he took part in Protector Somerset's expedition to Scotland and victory at Pinkie, and in 1549 an expedition to Guernsey and Jersey. In that year he was appointed Surveyor of the Navy

The Surveyor of the Navy also known as Department of the Surveyor of the Navy and originally known as Surveyor and Rigger of the Navy was a former principal commissioner and member of both the Navy Board from the inauguration of that body in 15 ...

, and in December as captain of the ''Mynion'' he captured the prize of a French ship, the ''Mary of Fécamp'', laden with sugar. A reward of £100 was to be shared out among the crew of 300. In 1550 he superintended the removal of the ships from Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

to Gillingham in the Thames Estuary

The Thames Estuary is where the River Thames meets the waters of the North Sea, in the south-east of Great Britain.

Limits

An estuary can be defined according to different criteria (e.g. tidal, geographical, navigational or in terms of salini ...

, Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

owed him £471 for a voyage to Ireland in 1552, and in 1553 he went on a voyage to the Levant.

In 1554, William spent several months in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

under suspicion of involvement in Thomas Wyatt's rebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

against Mary I of England

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. Sh ...

, until he was pardoned in November.

In 1557 Wynter was appointed Master of Navy Ordnance, which post he held along with the Surveyorship for the rest of his life. He was present at the burning of Conquet in 1558. On 22 May 1558 Wynter brought ships from Dunkirk to Dover which were sailing on to Portsmouth. He was sent with a fleet to Scotland in January 1560 during the crisis of the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke with the Pope, Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Church of Scotland, Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterianism, Presbyterian in ...

commanding the Irish Squadron

The Irish Squadron originally known as the Irish Fleet was a series of temporary naval formations assembled for specific military campaigns of the English Navy, the Navy Royal and later the Royal Navy from 1297 to 1731.

History

From the 13th ...

.

Mission to Scotland

Wynter commanded a fleet to guard against French landings in Scotland in 1559, while diplomatic efforts were made to negotiate sending an English army to aid the Scottish Protestants. After briefing at Gillingham, Wynter left

Wynter commanded a fleet to guard against French landings in Scotland in 1559, while diplomatic efforts were made to negotiate sending an English army to aid the Scottish Protestants. After briefing at Gillingham, Wynter left Queenborough

Queenborough is a town on the Isle of Sheppey in the Swale borough of Kent in South East England.

Queenborough is south of Sheerness. It grew as a port near the Thames Estuary at the westward entrance to the Swale where it joins the R ...

in the ''Lyon'' on 27 December, and sailed from the Lowestoft

Lowestoft ( ) is a coastal town and civil parish in the East Suffolk district of Suffolk, England.OS Explorer Map OL40: The Broads: (1:25 000) : . As the most easterly UK settlement, it is north-east of London, north-east of Ipswich and sou ...

sea-road on 14 January with 12 men-of-war followed by two supply ships, the ''Bull'' and the ''Saker''. After the fleet was dispersed by a storm off Flamborough Head

Flamborough Head () is a promontory, long on the Yorkshire coast of England, between the Filey and Bridlington bays of the North Sea. It is a chalk headland, with sheer white cliffs. The cliff top has two standing lighthouse towers, the olde ...

on 16 January, the damaged ''Swallow'', ''Falcon'', and ''Jerfalcon'' were left at Tynemouth

Tynemouth () is a coastal town in the metropolitan borough of North Tyneside, North East England. It is located on the north side of the mouth of the River Tyne, hence its name. It is 8 mi (13 km) east-northeast of Newcastle upon T ...

, and the rest of the fleet passed Bamborough Castle to Berwick upon Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census recor ...

, where 600 hand gunners were embarked. The Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

, commander in the North, gave Wynter orders to hinder any French landings in the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meani ...

, but to avoid battle, pretending he came up-river by chance without any official commission. At Coldingham

Coldingham ( sco, Cowjum) is a village and parish in Scottish Borders, on Scotland's southeast coastline, north of Eyemouth.

Parish

The parish lies in the east of the Lammermuir district. It is the second-largest civil parish by area in Berwi ...

bay, Wynter paused to send a copy of his log, which survives, to London. He was observed by Lord John Stewart, Commendator of Coldingham, a half-brother of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

.

Eight ships including the ''Antelope

The term antelope is used to refer to many species of even-toed ruminant that are indigenous to various regions in Africa and Eurasia.

Antelope comprise a wastebasket taxon defined as any of numerous Old World grazing and browsing hoofed mammals ...

'' and ''Lyon'' carried on into the Firth of Forth towards the fortress Island of Inchkeith

Inchkeith (from the gd, Innis Cheith) is an island in the Firth of Forth, Scotland, administratively part of the Fife council area.

Inchkeith has had a colourful history as a result of its proximity to Edinburgh and strategic location for u ...

on 21 January. Wynter's blockade was immediately effective in preventing communication by sea from Edinburgh to the French garrison at Dunbar Castle

Dunbar Castle was one of the strongest fortresses in Scotland, situated in a prominent position overlooking the harbour of the town of Dunbar, in East Lothian. Several fortifications were built successively on the site, near the English-Scotti ...

. Although he could not do as much as he wished because his small landing boats were lost in the storm, he captured two French ships loaded with armaments. At first the French had thought that Wynter's fleet were French ships bringing more troops, and their response was to send these boats loaded with munition for Henri Cleutin

Henri Cleutin, seigneur d'Oisel et de Villeparisis (1515 – 20 June 1566), was the representative of France in Scotland from 1546 to 1560, a Gentleman of the Chamber of the King of France, and a diplomat in Rome 1564-1566 during the French Wars o ...

who was advancing on St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fou ...

. Instead, Cleutin was forced to race back to Stirling overland, and William Kirkcaldy of Grange

Sir William Kirkcaldy of Grange (c. 1520 –3 August 1573) was a Scottish politician and soldier who fought for the Scottish Reformation but ended his career holding Edinburgh castle on behalf of Mary, Queen of Scots and was hanged at the co ...

delayed him by cutting the bridge over the Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

at Tullibody

Tullibody ( gd, Tulach Bòide), is a town set in the Central Lowlands of Scotland. It lies north of the River Forth near to the foot of the Ochil Hills within the Forth Valley. The town is south-west of Alva, north-west of Alloa and east-n ...

.

On 24 January Wynter allowed the Scottish Snawdoun Herald

Snawdoun Herald of Arms in Ordinary is a current Scottish herald of arms in Ordinary of the Court of the Lord Lyon.

The office was first mentioned in 1443 and the title is derived from a part of Stirling Castle which bore the same name. The p ...

John Patterson with the trumpet messenger James Drummond aboard the ''Lyon'', who demanded to know his business in Scottish waters. As instructed, Wynter told Snawdoun he had been bound for Berwick, and came into the Forth expecting "friendly entertainment" as the nations were at peace. As the French forts had fired on him, and he had heard of the political situation in Scotland, he had taken it upon himself to aid the Lords of the Congregation

The Lords of the Congregation (), originally styling themselves "the Faithful", were a group of Protestant Scottish nobles who in the mid-16th century favoured a reformation of the Catholic church according to Protestant principles and a Scotti ...

against the "wicked practices of the French," and so Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

knew nothing of it. Patterson and Drummond visited the English fleet four times.

Wynter's actions and speech to the herald were reported to the Privy Council of England

The Privy Council of England, also known as His (or Her) Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council (), was a body of advisers to the sovereign of the Kingdom of England. Its members were often senior members of the House of Lords and the House of ...

. To maintain the pretence he was instructed not to bring any ships he captured to England, but berth them in the friendly harbours of Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

and St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fou ...

which were in Protestant hands. As late as 16 February, Norfolk sent the Chester Herald

Chester Herald of Arms in Ordinary is an officer of arms at the College of Arms in London. The office of Chester Herald dates from the 14th century, and it is reputed that the holder was herald to Edward, Prince of Wales, also known as the Black ...

, William Flower, to Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (french: Marie de Guise; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was a French noblewoman of the House of Guise, a cadet branch of the House of Lorraine and one of the most powerful families in France. She ...

who declared the English fleet had arrived in the Firth by accident. She claimed that the Lords of the Congregation had revealed advance knowledge of Wynter's mission and were in communication with him. Flower replied that he had no knowledge of ships or letters. While this ineffectual diplomacy continued, the Lords of the Congregation concluded the Treaty of Berwick with Norfolk, which set conditions for English intervention. Some of the sons of the leading Protestants were given up as hostages to guarantee the treaty, and these boys were delivered to Wynter.

Wynter continued to harass shipping and then supported the English army brought in by the Treaty of Berwick to the Siege of Leith

The siege of Leith ended a twelve-year encampment of French troops at Leith, the port near Edinburgh, Scotland. The French troops arrived by invitation in 1548 and left in 1560 after an English force arrived to attempt to assist in removing the ...

. He burnt seven ships under d'Elbouf; not only that, all supplies were cut off from France. He kept up a naval bombardment of the town. On Saturday 7 May 1560, Wynter waited for a signal to sail up the Water of Leith

The Water of Leith (Scottish Gaelic: ''Uisge Lìte'') is the main river flowing near central Edinburgh, Scotland, and flows into the port of Leith where it flows into the sea via the Firth of Forth.

Name

The name ''Leith'' may be of Britto ...

and land 500 men on the quayside called the Shore, but the signal never came as the English assault on the walls had failed. The siege was ended by the negotiation of the Treaty of Edinburgh

The Treaty of Edinburgh (also known as the Treaty of Leith) was a treaty drawn up on 5 July 1560 between the Commissioners of Queen Elizabeth I of England with the assent of the Scottish Lords of the Congregation, and the French representatives ...

of 1560 which was the effective conclusion to the 'Auld Alliance

The Auld Alliance ( Scots for "Old Alliance"; ; ) is an alliance made in 1295 between the kingdoms of Scotland and France against England. The Scots word ''auld'', meaning ''old'', has become a partly affectionate term for the long-lasting a ...

'. Lord Burghley reported to the Privy Council that all spoke well of Wynter's conduct and he "was to be cherished." In July, Wynter discussed his fleet's return to Gillingham for re-fitting in dry-dock, but "the most expert officers of the Admiralty" sent the fleet to active service at Portsmouth, on their way escorting the ships evacuating the French army from Scotland to Calais.

In 1561 he purchased Lydney

Lydney is a town and civil parish in Gloucestershire, England. It is on the west bank of the River Severn in the Forest of Dean District, and is 16 miles (25 km) southwest of Gloucester. The town has been bypassed by the A48 road since 1995 ...

Manor in Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of Gl ...

as his residence. In that year, he helped save the Palace of the Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

from fire by advising the Mayor of London

The mayor of London is the chief executive of the Greater London Authority. The role was created in 2000 after the 1998 Greater London Authority referendum, Greater London devolution referendum in 1998, and was the first Directly elected may ...

, William Harpur

Sir William Harpur (c. 1496 – 27 February 1574) was a merchant from Bedford who moved to London, amassed a large fortune, and became Lord Mayor of London. In 1566 he and his wife Dame Alice gave an endowment to support certain charities inclu ...

to demolish the roof of the adjacent north aisle of St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

when the church caught fire after being struck by lightning on 4 June 1561. In 1563 he served in the fleet off Havre. In 1570, he was sent by Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

to escort Anne of Austria

Anne of Austria (french: Anne d'Autriche, italic=no, es, Ana María Mauricia, italic=no; 22 September 1601 – 20 January 1666) was an infanta of Spain who became Queen of France as the wife of King Louis XIII from their marriage in 1615 unti ...

on her sea journey from the Netherlands to mary Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

.

Operations off Ireland

In 1571, during the first of theDesmond Rebellions

The Desmond Rebellions occurred in 1569–1573 and 1579–1583 in the Irish province of Munster.

They were rebellions by the Earl of Desmond, the head of the Fitzmaurice/FitzGerald Dynasty in Munster, and his followers, the Geraldines and ...

one of Wynter's ships was seized at Kinsale by James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald

James fitz Maurice FitzGerald (died 1579), called "fitz Maurice", was captain-general of Desmond while Gerald FitzGerald, 14th Earl of Desmond, was detained in England by Queen Elizabeth after the Battle of Affane in 1565. He led the first Des ...

, the Irish rebel. On 12 August 1573, Wynter was knighted, but in 1577 he was passed over for the post of treasurer of the navy in place of Sir John Hawkins

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

, a promotion that would have doubled his income. Nevertheless, Sir William Wynter and his brother George, both received a handsome return on their investment in Sir Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 ( ...

's 1577 Voyage. In 1579 he commanded the squadron off Smerwick

Ard na Caithne (; meaning "height of the arbutus/ strawberry tree"), sometimes known in English as Smerwick, is a bay and townland in County Kerry in Ireland. One of the principal bays of Corca Dhuibhne, it is located at the foot of an Triúr ...

in Ireland, cutting off the sea-routes and seizing the ships of the papal invasion force, which was landed by Fitzmaurice in the company of Nicholas Sanders

Nicholas Sanders (also spelled Sander; c. 1530 – 1581) was an English Catholic priest and polemicist.

Early life

Sanders was born at Sander Place near Charlwood, Surrey, one of twelve children of William Sanders, once sheriff of Surrey, who ...

launching the Second Desmond Rebellion

The Second Desmond Rebellion (1579–1583) was the more widespread and bloody of the two Desmond Rebellions in Ireland launched by the FitzGerald Dynasty of Desmond in Munster against English rule. The second rebellion began in July 1579 when ...

; during this campaign he assisted in the siege of Carrigafoyle Castle.

Spanish Armada

In 1588, the year of theSpanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

, Wynter joined the main fleet of Lord Howard off Calais and proposed the fire-ship

A fire ship or fireship, used in the days of wooden rowed or sailing ships, was a ship filled with combustibles, or gunpowder deliberately set on fire and steered (or, when possible, allowed to drift) into an enemy fleet, in order to destroy sh ...

plan to drive the Spaniards from their anchorage; he took a celebrated part in the battle off Gravelines on 29 July, which was the only time in his career when he had hard fighting. During the engagement, he received a severe blow on the hip when a demi-cannon toppled over. It is said that he was the only one to have understood the completeness of the navy's defence, assessing from his experience at Leith that the enemy army's transport would require 300 ships, while Howard and Drake

Drake may refer to:

Animals

* A male duck

People and fictional characters

* Drake (surname), a list of people and fictional characters with the family name

* Drake (given name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* ...

thought that the invasion of England might still take place despite the naval repulse delivered to the armada.

Vice-Admiral of England

The Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom is an honorary office generally held by a senior Royal Navy admiral. The title holder is the official deputy to the Lord High Admiral, an honorary (although once operational) office which was vested in t ...

Sir William Wynter was granted the manor of Lydney

Lydney is a town and civil parish in Gloucestershire, England. It is on the west bank of the River Severn in the Forest of Dean District, and is 16 miles (25 km) southwest of Gloucester. The town has been bypassed by the A48 road since 1995 ...

in recognition of his services against the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

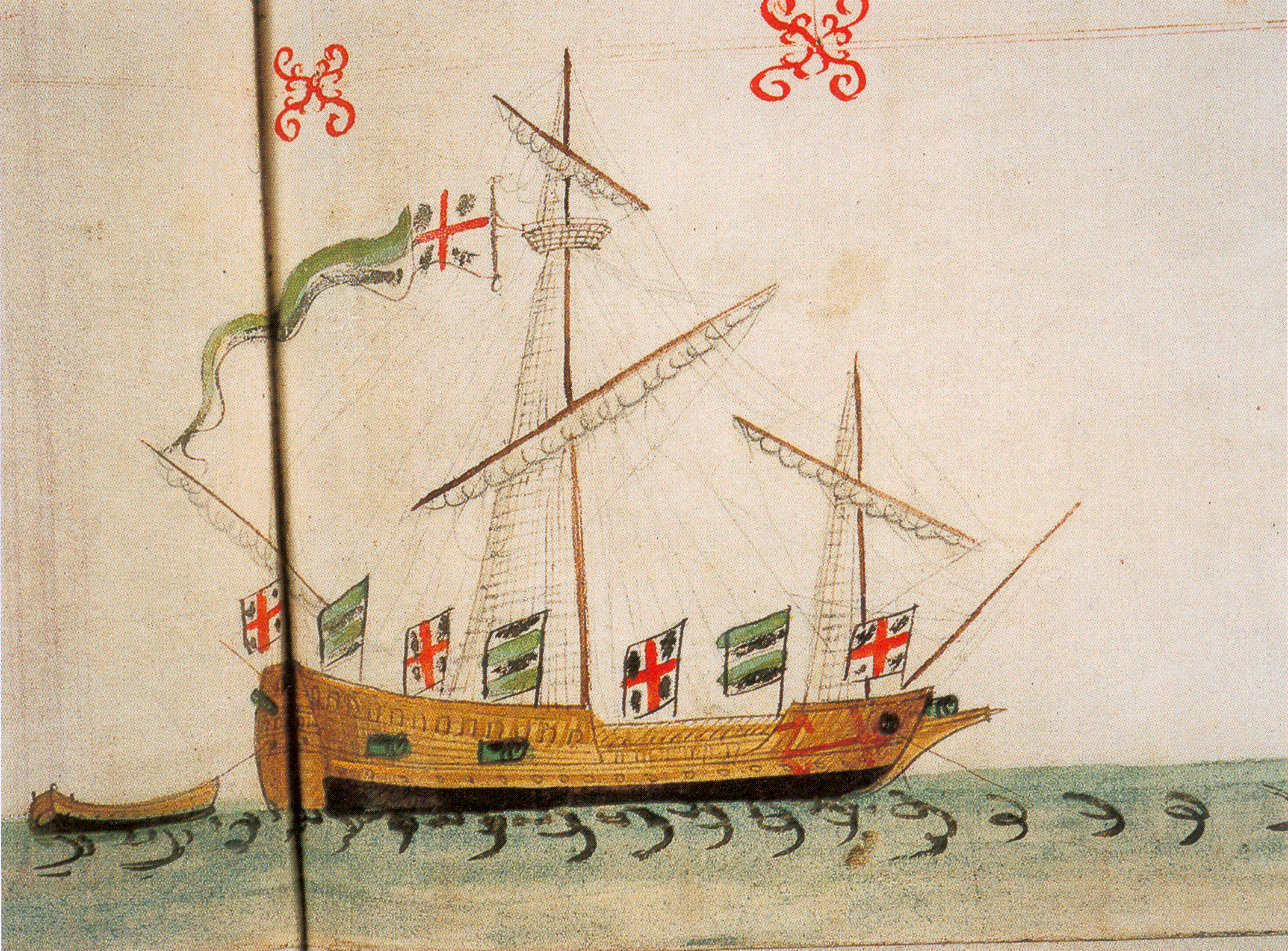

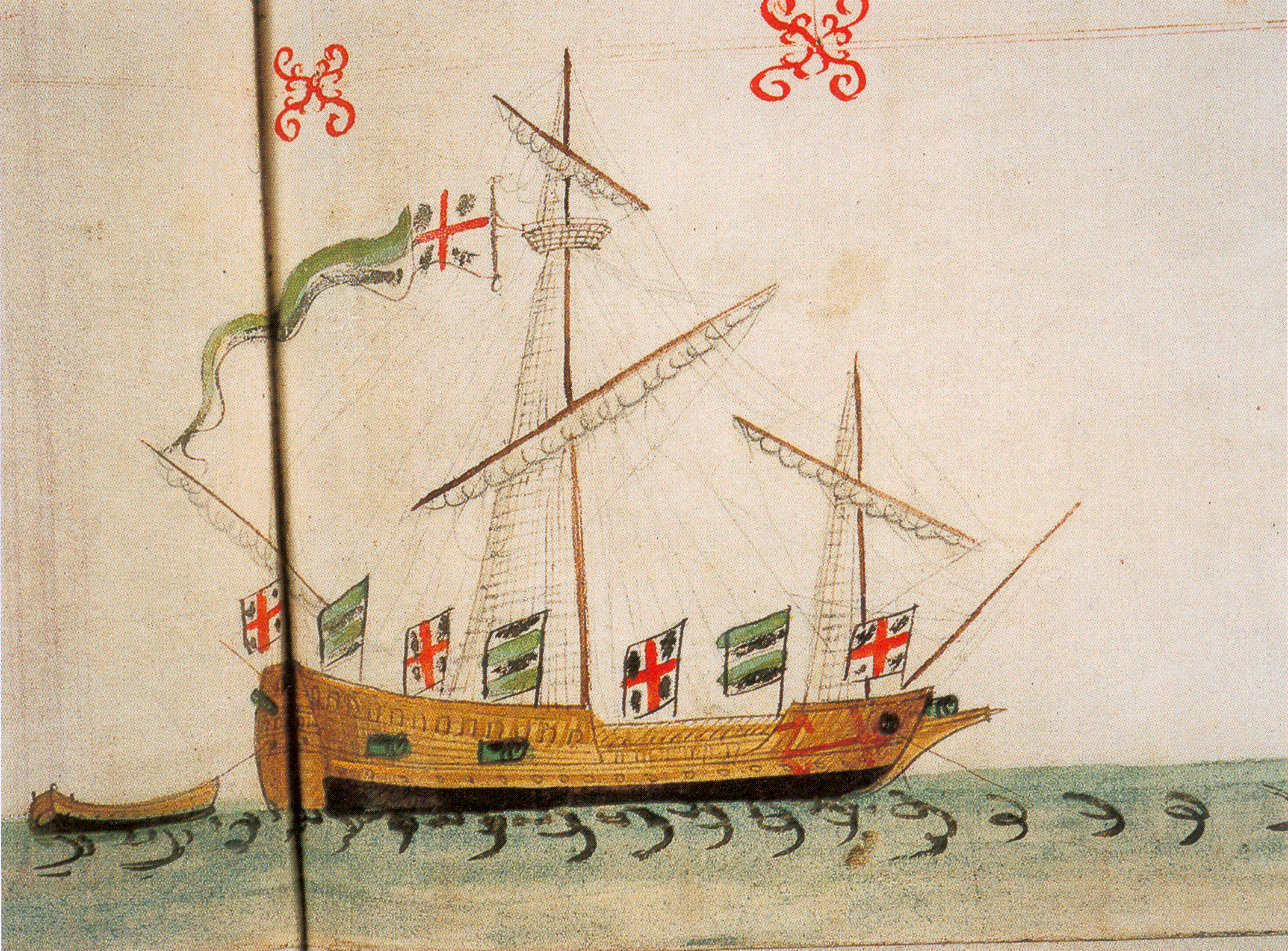

. His portrait was included in the Armada Tapestries.

Having been created admiral, Wynter supported charges of dishonesty against the treasurer of the navy

The Treasurer of the Navy, originally called Treasurer of Marine Causes or Paymaster of the Navy, was a civilian officer of the Royal Navy, one of the principal commissioners of the Navy Board responsible for naval finance from 1524 to 1832. T ...

, Hawkins, and wrote critically of him to Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley.

Offices held

:Included * Served on expeditions against Scotland 1544, 1547. * Channel fleet 1545. * Keeper of the Deptford Storehouse, 1546. * Surveyor and Rigger of the Navy, 8 July 1549 to 11 July 1589 *Master of Naval Ordnance

The Master of Naval Ordnance was an English Navy appointment created in 1546 the office holder was one of the Chief Officers of the Admiralty and a member of the Council of the Marine and a member of the Office of Ordnance until the post was abo ...

, 1557-1589

* Admiral in all seagoing expeditions 1557-88

* Justice of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

, Gloucestershire, from c.1564

* Commissioner of Sewers, Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

. and Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

, 1564.

* Mission to the Prince of Orange

Prince of Orange (or Princess of Orange if the holder is female) is a title originally associated with the sovereign Principality of Orange, in what is now southern France and subsequently held by sovereigns in the Netherlands.

The title ...

, 1576.

* Steward and Receiver, Duchy of Lancaster

The Duchy of Lancaster is the private estate of the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British sovereign as Duke of Lancaster. The principal purpose of the estate is to provide a source of independent income to the sovereign. The estate consists of ...

lands in Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of Gl ...

and Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouthshire ...

from 1580.

Legacy

Wynter married Mary Langton (died 4 November 1573, Seething Lane, London, daughter of Thomas and Mary Langton) and had issue: * Edward * William * Nicholas (died fighting Spaniards) * James (died young) * Mary * Elizabeth * Eleanor * Jane * Sarah His grandson was John Winter who was an activeroyalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

.

Wynter died on 20 February 1589 aged 68. A Latin eulogy by William Patten was published in that year.Patten, William, ''In Mortem W. Wynter equitis auratis'', Thomas Orvvinum, London (1589), (8pp).

References

*Richard Bagwell, ''Ireland under the Tudors'' 3 vols. (London, 1885–1890). *Notes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wynter, William 1520s births 1589 deaths Year of birth uncertain People from Brecknockshire English admirals 16th-century Royal Navy personnel People of Elizabethan Ireland 16th-century Welsh military personnel Scottish Reformation 16th century in Scotland English MPs 1559 English MPs 1563–1567 English MPs 1572–1583 English MPs 1586–1587 People of the Second Desmond Rebellion 16th-century Welsh politiciansWilliam

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...