Whale Cove, Nunavut2 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully

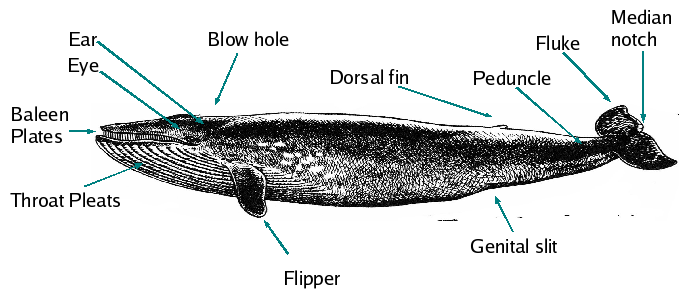

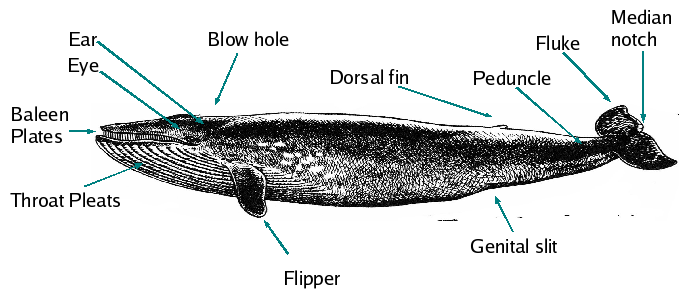

Whales have torpedo-shaped bodies with non-flexible necks, limbs modified into flippers, non-existent external ear flaps, a large tail fin, and flat heads (with the exception of monodontids and

Whales have torpedo-shaped bodies with non-flexible necks, limbs modified into flippers, non-existent external ear flaps, a large tail fin, and flat heads (with the exception of monodontids and

Whales have two flippers on the front, and a tail fin. These flippers contain four digits. Although whales do not possess fully developed hind limbs, some, such as the sperm whale and bowhead whale, possess discrete rudimentary appendages, which may contain feet and digits. Whales are fast swimmers in comparison to seals, which typically cruise at 5–15 kn, or ; the fin whale, in comparison, can travel at speeds up to and the sperm whale can reach speeds of . The fusing of the neck vertebrae, while increasing stability when swimming at high speeds, decreases flexibility; whales are unable to turn their heads. When swimming, whales rely on their tail fin to propel them through the water. Flipper movement is continuous. Whales swim by moving their tail fin and lower body up and down, propelling themselves through vertical movement, while their flippers are mainly used for steering. Some species

Whales have two flippers on the front, and a tail fin. These flippers contain four digits. Although whales do not possess fully developed hind limbs, some, such as the sperm whale and bowhead whale, possess discrete rudimentary appendages, which may contain feet and digits. Whales are fast swimmers in comparison to seals, which typically cruise at 5–15 kn, or ; the fin whale, in comparison, can travel at speeds up to and the sperm whale can reach speeds of . The fusing of the neck vertebrae, while increasing stability when swimming at high speeds, decreases flexibility; whales are unable to turn their heads. When swimming, whales rely on their tail fin to propel them through the water. Flipper movement is continuous. Whales swim by moving their tail fin and lower body up and down, propelling themselves through vertical movement, while their flippers are mainly used for steering. Some species

The whale ear has specific adaptations to the marine environment. In humans, the

The whale ear has specific adaptations to the marine environment. In humans, the

To feed the newborn, whales, being aquatic, must squirt the milk into the mouth of the calf. Nursing can occur while the mother whale is in the vertical or horizontal position. While nursing in the vertical position, a mother whale may sometimes rest with her tail flukes remaining stationary above the water. This position with the flukes above the water is known as "whale-tail-sailing." Not all whale-tail-sailing includes nursing of the young, as whales have also been observed tail-sailing while no calves were present.

Being mammals, they have mammary glands used for nursing calves; weaning occurs at about 11 months of age. This milk contains high amounts of fat which is meant to hasten the development of blubber; it contains so much fat that it has the consistency of toothpaste. Like humans, female whales typically deliver a single offspring. Whales have a typical gestation period of 12 months. Once born, the absolute dependency of the calf upon the mother lasts from one to two years. Sexual maturity is achieved at around seven to ten years of age. The length of the developmental phases of a whale's early life varies between different whale species.

As with humans, the whale mode of reproduction typically produces but one offspring approximately once each year. While whales have fewer offspring over time than most species, the probability of survival for each calf is also greater than for most other species. Female whales are referred to as "cows." Cows assume full responsibility for the care and training of their young. Male whales, referred to as "bulls," typically play no role in the process of calf-rearing.

Most baleen whales reside at the poles. To prevent the unborn baleen whale calves from dying of frostbite, the baleen mother must migrate to warmer calving/mating grounds. They will then stay there for a matter of months until the calf has developed enough blubber to survive the bitter temperatures of the poles. Until then, the baleen calves will feed on the mother's fatty milk.

With the exception of the humpback whale, it is largely unknown when whales migrate. Most will travel from the Arctic or Antarctic into the

To feed the newborn, whales, being aquatic, must squirt the milk into the mouth of the calf. Nursing can occur while the mother whale is in the vertical or horizontal position. While nursing in the vertical position, a mother whale may sometimes rest with her tail flukes remaining stationary above the water. This position with the flukes above the water is known as "whale-tail-sailing." Not all whale-tail-sailing includes nursing of the young, as whales have also been observed tail-sailing while no calves were present.

Being mammals, they have mammary glands used for nursing calves; weaning occurs at about 11 months of age. This milk contains high amounts of fat which is meant to hasten the development of blubber; it contains so much fat that it has the consistency of toothpaste. Like humans, female whales typically deliver a single offspring. Whales have a typical gestation period of 12 months. Once born, the absolute dependency of the calf upon the mother lasts from one to two years. Sexual maturity is achieved at around seven to ten years of age. The length of the developmental phases of a whale's early life varies between different whale species.

As with humans, the whale mode of reproduction typically produces but one offspring approximately once each year. While whales have fewer offspring over time than most species, the probability of survival for each calf is also greater than for most other species. Female whales are referred to as "cows." Cows assume full responsibility for the care and training of their young. Male whales, referred to as "bulls," typically play no role in the process of calf-rearing.

Most baleen whales reside at the poles. To prevent the unborn baleen whale calves from dying of frostbite, the baleen mother must migrate to warmer calving/mating grounds. They will then stay there for a matter of months until the calf has developed enough blubber to survive the bitter temperatures of the poles. Until then, the baleen calves will feed on the mother's fatty milk.

With the exception of the humpback whale, it is largely unknown when whales migrate. Most will travel from the Arctic or Antarctic into the

All whales are carnivorous and predatory. Odontocetes, as a whole, mostly feed on

All whales are carnivorous and predatory. Odontocetes, as a whole, mostly feed on

The IWC has designated two whale sanctuaries: the

The IWC has designated two whale sanctuaries: the

An estimated 13 million people went

An estimated 13 million people went

Belugas were the first whales to be kept in captivity. Other species were too rare, too shy, or too big. The first beluga was shown at Barnum's Museum in

Belugas were the first whales to be kept in captivity. Other species were too rare, too shy, or too big. The first beluga was shown at Barnum's Museum in

Mingan Island Cetacean Study (MICS)

*Children's drawings and lyrics from the song Stor

(French) * * * {{Authority control Cetaceans Paraphyletic groups

aquatic

Aquatic means relating to water; living in or near water or taking place in water; does not include groundwater, as "aquatic" implies an environment where plants and animals live.

Aquatic(s) may also refer to:

* Aquatic animal, either vertebrate ...

placental

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguished ...

marine mammal

Marine mammals are mammals that rely on marine ecosystems for their existence. They include animals such as cetaceans, pinnipeds, sirenians, sea otters and polar bears. They are an informal group, unified only by their reliance on marine enviro ...

s. As an informal and colloquial

Colloquialism (also called ''colloquial language'', ''colloquial speech'', ''everyday language'', or ''general parlance'') is the linguistic style used for casual and informal communication. It is the most common form of speech in conversation amo ...

grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal in the cetacean clade Odontoceti (toothed whale). Dolphins belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontopori ...

s and porpoise

Porpoises () are small Oceanic dolphin, dolphin-like cetaceans classified under the family Phocoenidae. Although similar in appearance to dolphins, they are more closely related to narwhals and Beluga whale, belugas than to the Oceanic dolphi ...

s. Dolphins and porpoises may be considered whales from a formal, cladistic

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is ...

perspective. Whales, dolphins and porpoises belong to the order Cetartiodactyla

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order (biology), order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof ...

, which consists of even-toed ungulate

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

s. Their closest non-cetacean living relatives are the hippopotamus

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Sahar ...

es, from which they and other cetaceans diverged about 54 million years ago. The two parvorder

Order () is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and recognized ...

s of whales, baleen whale

Baleen whales (), also known as whalebone whales, are marine mammals of the order (biology), parvorder Mysticeti in the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises), which use baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their mouths to sieve plankt ...

s (Mysticeti) and toothed whale

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales with teeth, such as beaked whales and the sperm whales. 73 species of toothed wha ...

s (Odontoceti), are thought to have had their last common ancestor

A most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as a last common ancestor (LCA), is the most recent individual from which all organisms of a set are inferred to have descended. The most recent common ancestor of a higher taxon is generally assu ...

around 34 million years ago. Mysticetes include four extant

Extant or Least-concern species, least concern is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Exta ...

(living) families

Family (from ) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictability, structure, and safety as ...

: Balaenopteridae

Rorquals () are the largest clade, group of baleen whales, comprising the family (biology), family Balaenopteridae, which contains nine extant taxon, extant species in two genus, genera. They include the largest known animal that has ever lived, ...

(the rorquals), Balaenidae

Balaenidae () is a Family (biology), family of whales of the parvorder Mysticeti (baleen whales) that contains mostly fossil taxa and two living genera: the right whale (genus ''Eubalaena''), and the closely related bowhead whale (genus ''Balaena ...

(right whales), Cetotheriidae

Cetotheriidae is a family of baleen whales (parvorder Mysticeti). The family is known to have existed from the Late Oligocene to the Early Pleistocene before going extinct. Although some phylogenetic studies conducted by recovered the living py ...

(the pygmy right whale), and Eschrichtiidae

Eschrichtiidae or the gray whales is a family (taxonomy), family of baleen whale (Parvorder Mysticeti) with a single extant species, the gray whale (''Eschrichtius robustus''), as well as four described fossil genera: ''Archaeschrichtius'' (Mioce ...

(the grey whale). Odontocetes include the Monodontidae

The cetacean family Monodontidae comprises two living whale species, the narwhal and the beluga whale and at least four extinct species, known from the fossil record. Beluga and narwhal are native to coastal regions and pack ice around the Arcti ...

(belugas and narwhals), Physeteridae

Physeteroidea is a superfamily that includes three extant species of whales: the sperm whale, in the genus '' Physeter'', and the pygmy sperm whale and dwarf sperm whale, in the genus ''Kogia''. In the past, these genera have sometimes been unit ...

(the sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the Genus (biology), genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the s ...

), Kogiidae

Kogiidae is a family comprising at least two extant species of Cetacea, the pygmy (''Kogia breviceps)'' and dwarf (''K. sima)'' sperm whales. As their common names suggest, they somewhat resemble sperm whales, with squared heads and small lower ...

(the dwarf and pygmy sperm whale), and Ziphiidae

Beaked whales (systematic name Ziphiidae) are a family of cetaceans noted as being one of the least-known groups of mammals because of their deep-sea habitat, reclusive behavior and apparent low abundance. Only three or four of the 24 existing s ...

(the beaked whales), as well as the six families of dolphins and porpoises which are not considered whales in the informal sense.

Whales are fully aquatic, open-ocean animals: they can feed, mate, give birth, suckle and raise their young at sea. Whales range in size from the and dwarf sperm whale

The dwarf sperm whale (''Kogia sima'') is a sperm whale that inhabits temperate and tropical oceans worldwide, in particular continental shelves and slopes. It was first described by biologist Richard Owen in 1866, based on illustrations by na ...

to the and blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known ever to have existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

, which is the largest known animal that has ever lived. The sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the Genus (biology), genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the s ...

is the largest toothed predator on Earth. Several whale species exhibit sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

, in that the females are larger than males.

Baleen whales have no teeth; instead, they have plates of baleen, fringe-like structures that enable them to expel the huge mouthfuls of water they take in while retaining the krill

Krill ''(Euphausiids)'' (: krill) are small and exclusively marine crustaceans of the order (biology), order Euphausiacea, found in all of the world's oceans. The name "krill" comes from the Norwegian language, Norwegian word ', meaning "small ...

and plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

they feed on. Because their heads are enormous—making up as much as 40% of their total body mass—and they have throat pleats that enable them to expand their mouths, they are able to take huge quantities of water into their mouth at a time. Baleen whales also have a well-developed sense of smell.

Toothed whales, in contrast, have conical teeth adapted to catching fish or squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, and Bathyteuthida (though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also ...

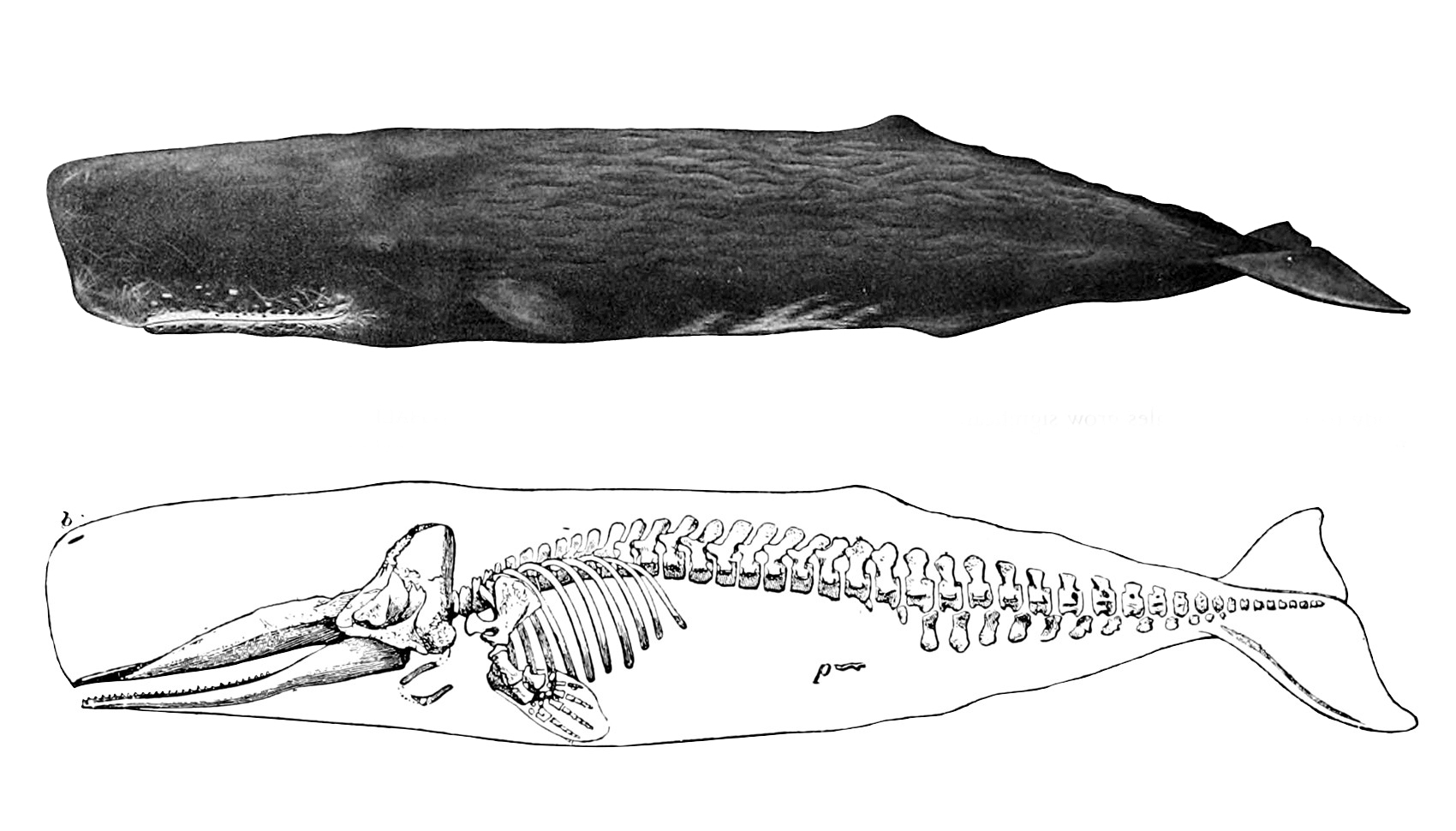

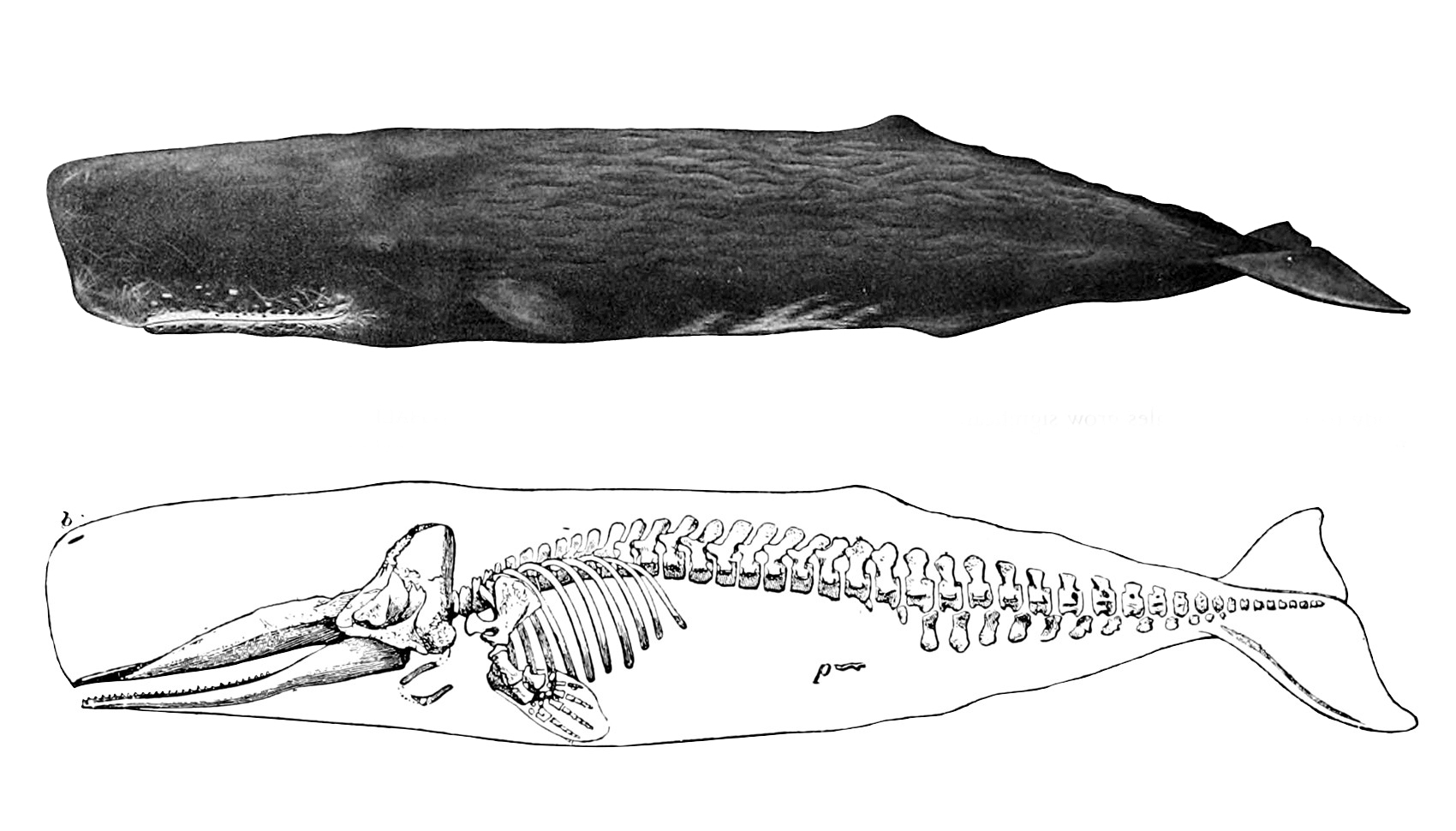

. They also have such keen hearing—whether above or below the surface of the water—that some can survive even if they are blind. Some species, such as sperm whales, are particularly well adapted for diving to great depths to catch squid and other favoured prey.

Whales evolved from land-living mammals, and must regularly surface to breathe air, although they can remain underwater for long periods of time. Some species, such as the sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the Genus (biology), genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the s ...

, can stay underwater for up to 90 minutes. They have blowholes (modified nostrils) located on top of their heads, through which air is taken in and expelled. They are warm-blooded

Warm-blooded is a term referring to animal species whose bodies maintain a temperature higher than that of their environment. In particular, homeothermic species (including birds and mammals) maintain a stable body temperature by regulating ...

, and have a layer of fat, or blubber

Blubber is a thick layer of Blood vessel, vascularized adipose tissue under the skin of all cetaceans, pinnipeds, penguins, and sirenians. It was present in many marine reptiles, such as Ichthyosauria, ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs.

Description ...

, under the skin. With streamlined fusiform

Fusiform (from Latin ''fusus'' ‘spindle’) means having a spindle (textiles), spindle-like shape that is wide in the middle and tapers at both ends. It is similar to the lemon (geometry), lemon-shape, but often implies a focal broadening of a ...

bodies and two limbs that are modified into flippers, whales can travel at speeds of up to 20 knots

A knot is a fastening in rope or interwoven lines.

Knot or knots may also refer to:

Other common meanings

* Knot (unit), of speed

* Knot (wood), a timber imperfection

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Knots'' (film), a 2004 film

* ''Kn ...

, though they are not as flexible or agile as seals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

. Whales produce a great variety of vocalizations, notably the extended songs of the humpback whale

The humpback whale (''Megaptera novaeangliae'') is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the monotypic taxon, only species in the genus ''Megaptera''. Adults range in length from and weigh u ...

. Although whales are widespread, most species prefer the colder waters of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres and migrate to the equator to give birth. Species such as humpbacks and blue whales are capable of travelling thousands of miles without feeding. Males typically mate with multiple females every year, but females only mate every two to three years. Calves are typically born in the spring and summer; females bear all the responsibility for raising them. Mothers in some species fast and nurse their young for one to two years.

Once relentlessly hunted for their products, whales are now protected by international law. The North Atlantic right whale

The North Atlantic right whale (''Eubalaena glacialis'') is a baleen whale, one of three right whale species belonging to the genus ''Eubalaena'', all of which were formerly classified as a single species. Because of their docile nature, their sl ...

s nearly became extinct in the twentieth century, with a population low of 450, and the North Pacific grey whale population is ranked Critically Endangered

An IUCN Red List critically endangered (CR or sometimes CE) species is one that has been categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild. As of December 2023, of t ...

by the IUCN

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the status ...

. Besides the threat from whalers, they also face threats from bycatch and marine pollution. The meat, blubber and baleen

Baleen is a filter feeder, filter-feeding system inside the mouths of baleen whales. To use baleen, the whale first opens its mouth underwater to take in water. The whale then pushes the water out, and animals such as krill are filtered by th ...

of whales have traditionally been used by indigenous peoples of the Arctic. Whales have been depicted in various cultures worldwide, notably by the Inuit and the coastal peoples of Vietnam and Ghana, who sometimes hold whale funerals. Whales occasionally feature in literature and film. A famous example is the great white whale in Herman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works ar ...

's novel ''Moby-Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 Epic (genre), epic novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is centered on the sailor Ishmael (Moby-Dick), Ishmael's narrative of the maniacal quest of Captain Ahab, Ahab, captain of the whaler ...

''. Small whales, such as belugas, are sometimes kept in captivity and trained to perform tricks, but breeding success has been poor and the animals often die within a few months of capture. Whale watching

Whale watching is the practice of observing whales and dolphins (cetaceans) in their natural habitat. Whale watching is mostly a recreational activity (cf. birdwatching), but it can also serve scientific and/or educational purposes.Hoyt, E. ...

has become a form of tourism around the world.

Etymology and definitions

The word "whale" comes from theOld English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

''hwæl'', from Proto-Germanic

Proto-Germanic (abbreviated PGmc; also called Common Germanic) is the linguistic reconstruction, reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic languages, Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Proto-Germanic eventually developed from ...

''*hwalaz'', from Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists; its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-Euro ...

''*(s)kwal-o-'', meaning "large sea fish". The Proto-Germanic ''*hwalaz'' is also the source of Old Saxon

Old Saxon (), also known as Old Low German (), was a Germanic language and the earliest recorded form of Low German (spoken nowadays in Northern Germany, the northeastern Netherlands, southern Denmark, the Americas and parts of Eastern Eur ...

''hwal'', Old Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

''hvalr'', ''hvalfiskr'', Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

''val'', Middle Dutch

Middle Dutch is a collective name for a number of closely related West Germanic dialects whose ancestor was Old Dutch. It was spoken and written between 1150 and 1500. Until the advent of Modern Dutch after 1500 or , there was no overarching sta ...

''wal'', ''walvisc'', Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

''walvis'', Old High German

Old High German (OHG; ) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally identified as the period from around 500/750 to 1050. Rather than representing a single supra-regional form of German, Old High German encompasses the numerous ...

''wal'', and German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

''Wal''. Other archaic English forms include ''wal, wale, whal, whalle, whaille, wheal'', etc.

The term "whale" is sometimes used interchangeably with dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal in the cetacean clade Odontoceti (toothed whale). Dolphins belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontopori ...

s and porpoise

Porpoises () are small Oceanic dolphin, dolphin-like cetaceans classified under the family Phocoenidae. Although similar in appearance to dolphins, they are more closely related to narwhals and Beluga whale, belugas than to the Oceanic dolphi ...

s, acting as a synonym for Cetacea

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

. Six species of dolphins have the word "whale" in their name, collectively known as blackfish: the orca

The orca (''Orcinus orca''), or killer whale, is a toothed whale and the largest member of the oceanic dolphin family. The only extant species in the genus '' Orcinus'', it is recognizable by its black-and-white-patterned body. A cosmopol ...

, or killer whale, the melon-headed whale

The melon-headed whale (''Peponocephala electra''), also known less commonly as the electra dolphin, little killer whale, or many-toothed blackfish, is a toothed whale of the oceanic dolphin family (Delphinidae). The common name is derived from t ...

, the pygmy killer whale

The pygmy killer whale (''Feresa attenuata'') is a poorly known and rarely seen oceanic dolphin. It is the monotypic taxon, only species in the genus ''Feresa''. It derives its common name from sharing some physical characteristics with the orca ...

, the false killer whale

The false killer whale (''Pseudorca crassidens'') is a species of oceanic dolphin that is the only extant representative of the genus ''Pseudorca''. It is found in oceans worldwide but mainly in tropical regions. It was first species descriptio ...

, and the two species of pilot whale

Pilot whales are cetaceans belonging to the genus ''Globicephala''. The two Extant taxon, extant species are the long-finned pilot whale (''G. melas'') and the short-finned pilot whale (''G. macrorhynchus''). The two are not readily distinguish ...

s, all of which are classified under the family Delphinidae

Oceanic dolphins or Delphinidae are a widely distributed family of dolphins that live in the sea. Close to forty extant species are recognised. They include several big species whose common names contain "whale" rather than "dolphin", such as the ...

(oceanic dolphins). Each species has a different reason for it, for example, the killer whale was named "Ballena asesina" 'killer whale' by Spanish sailors.

The term "Great Whales" covers those currently regulated by the International Whaling Commission

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) is a specialised regional fishery management organisation, established under the terms of the 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) to "provide for the proper conservation ...

: the Odontoceti family Physeteridae (sperm whales); and the Mysticeti families Balaenidae (right and bowhead whales), Eschrichtiidae (grey whales), and some of the Balaenopteridae (Minke, Bryde's, Sei, Blue and Fin; not Eden's and Omura's whales).

Taxonomy and evolution

Phylogeny

The whales are part of the largely terrestrial mammalianclade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

Laurasiatheria

Laurasiatheria (; "Laurasian beasts") is a superorder of Placentalia, placental mammals that groups together true insectivores (eulipotyphlans), bats (chiropterans), carnivorans, pangolins (Pholidota, pholidotes), even-toed ungulates (Artiodacty ...

. Whales do not form a clade or order; the infraorder Cetacea includes dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal in the cetacean clade Odontoceti (toothed whale). Dolphins belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontopori ...

s and porpoise

Porpoises () are small Oceanic dolphin, dolphin-like cetaceans classified under the family Phocoenidae. Although similar in appearance to dolphins, they are more closely related to narwhals and Beluga whale, belugas than to the Oceanic dolphi ...

s, which are not considered whales in the informal sense. The phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA. In ...

shows the relationships of whales and other mammals, with whale groups marked in green.

Cetaceans are divided into two parvorders. The larger parvorder, Mysticeti

Baleen whales (), also known as whalebone whales, are marine mammals of the parvorder Mysticeti in the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises), which use baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their mouths to sieve plankton from the wate ...

(baleen whales), is characterized by the presence of baleen, a sieve-like structure in the upper jaw made of keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. It is the key structural material making up Scale (anatomy), scales, hair, Nail (anatomy), nails, feathers, horn (anatomy), horns, claws, Hoof, hoove ...

, which it uses to filter plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

, among others, from the water. Odontocetes

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a Order (biology), parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales with teeth, such as beaked whales and the sperm whales. 73 species of t ...

(toothed whales) are characterized by bearing sharp teeth for hunting, as opposed to their counterparts' baleen.

Cetaceans and artiodactyl

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

s now are classified under the order Cetartiodactyla

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order (biology), order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof ...

, often still referred to as Artiodactyla, which includes both whales and hippopotamus

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Sahar ...

es. The hippopotamus and pygmy hippopotamus are the whales' closest terrestrial living relatives.

Mysticetes

Mysticetes are also known as baleen whales. They have a pair of blowholes side by side and lack teeth; instead they have baleen plates which form a sieve-like structure in the upper jaw made of keratin, which they use to filterplankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

from the water. Some whales, such as the humpback, reside in the polar regions where they feed on a reliable source of schooling fish and krill

Krill ''(Euphausiids)'' (: krill) are small and exclusively marine crustaceans of the order (biology), order Euphausiacea, found in all of the world's oceans. The name "krill" comes from the Norwegian language, Norwegian word ', meaning "small ...

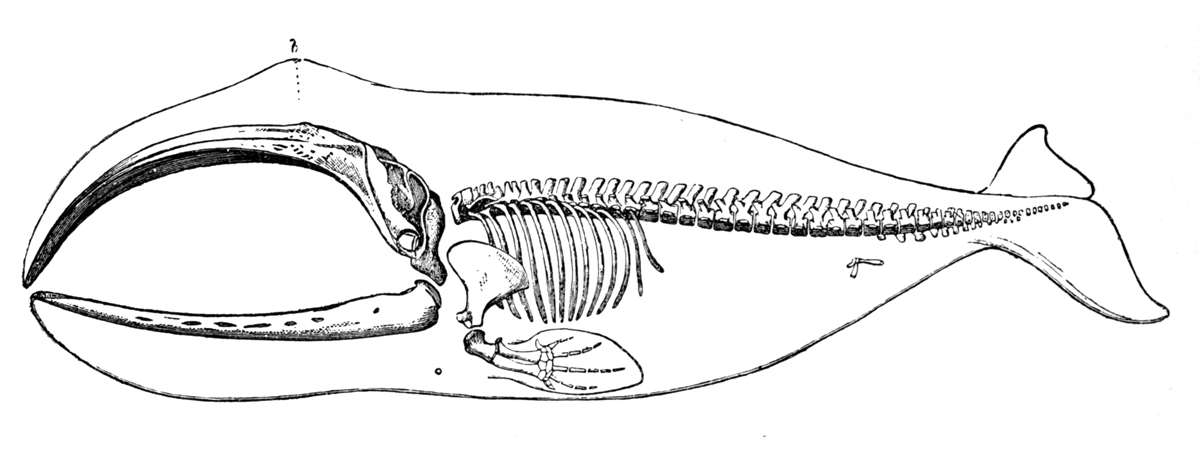

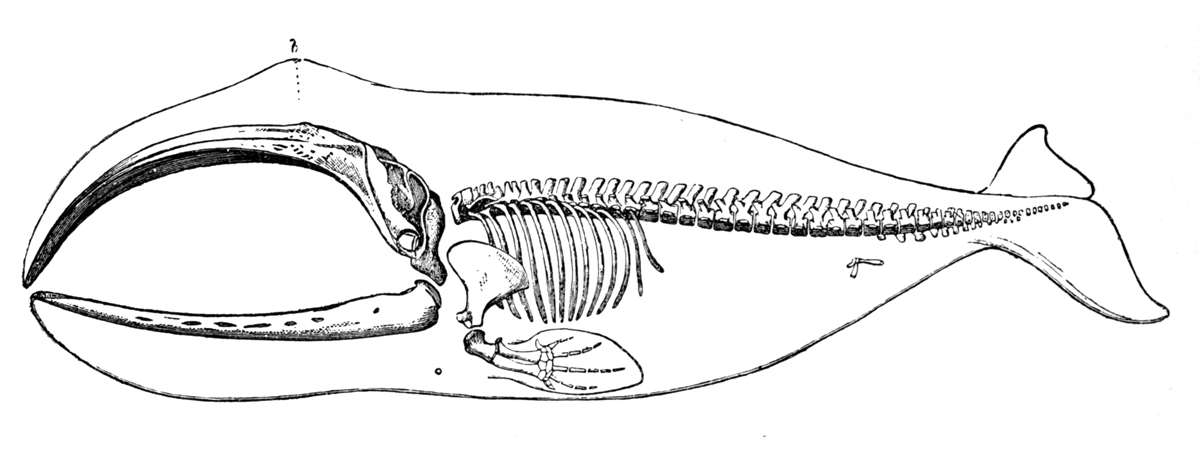

. These animals rely on their well-developed flippers and tail fin to propel themselves through the water; they swim by moving their fore-flippers and tail fin up and down. Whale ribs loosely articulate with their thoracic vertebrae

In vertebrates, thoracic vertebrae compose the middle segment of the vertebral column, between the cervical vertebrae and the lumbar vertebrae. In humans, there are twelve thoracic vertebra (anatomy), vertebrae of intermediate size between the ce ...

at the proximal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

end, but do not form a rigid rib cage. This adaptation allows the chest to compress during deep dives as the pressure increases. Mysticetes consist of four families: rorquals (balaenopterids), cetotheriids, right whales (balaenids), and grey whales (eschrichtiids).

The main difference between each family of mysticete is in their feeding adaptations and subsequent behaviour.

Balaenopterids are the rorquals. These animals, along with the cetotheriids, rely on their throat pleats to gulp large amounts of water while feeding. The throat pleats extend from the mouth to the navel and allow the mouth to expand to a large volume for more efficient capture of the small animals they feed on. Balaenopterids consist of two genera and eight species.

Balaenids are the right whales. These animals have very large heads, which can make up as much as 40% of their body mass, and much of the head is the mouth. This allows them to take in large amounts of water into their mouths, letting them feed more effectively.

Eschrichtiids have one living member: the grey whale. They are bottom feeders, mainly eating crustaceans and benthic invertebrates. They feed by turning on their sides and taking in water mixed with sediment, which is then expelled through the baleen, leaving their prey trapped inside. This is an efficient method of hunting, in which the whale has no major competitors.

Odontocetes

Odontocetes are known as toothed whales; they have teeth and only one blowhole. They rely on their well-developed sonar to find their way in the water. Toothed whales send outultrasonic

Ultrasound is sound with frequencies greater than 20 kilohertz. This frequency is the approximate upper audible limit of human hearing in healthy young adults. The physical principles of acoustic waves apply to any frequency range, includi ...

clicks using the melon

A melon is any of various plants of the family Cucurbitaceae with sweet, edible, and fleshy fruit. It can also specifically refer to ''Cucumis melo'', commonly known as the "true melon" or simply "melon". The term "melon" can apply to both the p ...

. Sound waves travel through the water. Upon striking an object in the water, the sound waves bounce back at the whale. These vibrations are received through fatty tissues in the jaw, which is then rerouted into the ear-bone and into the brain where the vibrations are interpreted. All toothed whales are opportunistic, meaning they will eat anything they can fit in their throat because they are unable to chew. These animals rely on their well-developed flippers and tail fin to propel themselves through the water; they swim by moving their fore-flippers and tail fin up and down. Whale ribs loosely articulate with their thoracic vertebrae

In vertebrates, thoracic vertebrae compose the middle segment of the vertebral column, between the cervical vertebrae and the lumbar vertebrae. In humans, there are twelve thoracic vertebra (anatomy), vertebrae of intermediate size between the ce ...

at the proximal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

end, but they do not form a rigid rib cage. This adaptation allows the chest to compress during deep dives as opposed to resisting the force of water pressure. Excluding dolphins and porpoises, odontocetes consist of four families: belugas and narwhals (monodontids), sperm whales (physeterids), dwarf and pygmy sperm whales (kogiids), and beaked whales (ziphiids).

The differences between families of odontocetes include size, feeding adaptations and distribution. Monodontids consist of two species: the beluga

Beluga may refer to:

Animals

*Beluga (sturgeon)

* Beluga whale

Vehicles

* Airbus Beluga, a large transport airplane

* Airbus BelugaXL, a larger transport airplane

* Beluga-class submarine, a class of Russian SSA diesel-electric submarine

* U ...

and the narwhal

The narwhal (''Monodon monoceros'') is a species of toothed whale native to the Arctic. It is the only member of the genus ''Monodon'' and one of two living representatives of the family Monodontidae. The narwhal is a stocky cetacean with a ...

. They both reside in the frigid arctic and both have large amounts of blubber. Belugas, being white, hunt in large pods near the surface and around pack ice, their coloration acting as camouflage. Narwhals, being black, hunt in large pods in the aphotic zone, but their underbelly still remains white to remain camouflaged when something is looking directly up or down at them. They have no dorsal fin to prevent collision with pack ice.

Physeterids and Kogiids consist of sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the Genus (biology), genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the s ...

s. Sperm whales consist the largest and smallest odontocetes, and spend a large portion of their life hunting squid. ''P. macrocephalus'' spends most of its life in search of squid in the depths; these animals do not require any degree of light at all, in fact, blind sperm whales have been caught in perfect health. The behaviour of Kogiids remains largely unknown, but, due to their small lungs, they are thought to hunt in the photic zone

The photic zone (or euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone) is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological ...

.

Ziphiids consist of 22 species of beaked whale

Beaked whales (systematic name Ziphiidae) are a Family (biology), family of cetaceans noted as being one of the least-known groups of mammals because of their deep-sea habitat, reclusive behavior and apparent low abundance. Only three or four of ...

. These vary from size, to coloration, to distribution, but they all share a similar hunting style. They use a suction technique, aided by a pair of grooves on the underside of their head, not unlike the throat pleats on the rorqual

Rorquals () are the largest clade, group of baleen whales, comprising the family (biology), family Balaenopteridae, which contains nine extant taxon, extant species in two genus, genera. They include the largest known animal that has ever lived, ...

s, to feed.

As a formal clade (a group which does not exclude any descendant taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

), odontocetes also contains the porpoise

Porpoises () are small Oceanic dolphin, dolphin-like cetaceans classified under the family Phocoenidae. Although similar in appearance to dolphins, they are more closely related to narwhals and Beluga whale, belugas than to the Oceanic dolphi ...

s (Phocoenidae) and four or five living families of dolphins: oceanic dolphins (Delphinidae

Oceanic dolphins or Delphinidae are a widely distributed family of dolphins that live in the sea. Close to forty extant species are recognised. They include several big species whose common names contain "whale" rather than "dolphin", such as the ...

), South Asian river dolphin

South Asian river dolphins are toothed whales in the genus ''Platanista'', which inhabit the waterways of the Indian subcontinent. They were historically considered to be one species (''P. gangetica'') with the Ganges river dolphin and the Indu ...

s (Platanistidae

Platanistidae is a family of river dolphins containing the extant Ganges river dolphin and Indus river dolphin (both in the genus ''Platanista'') but also extinct relatives from freshwater and marine deposits in the Neogene.

The Amazon river dol ...

), the possibly extinct Yangtze River dolphin

The baiji (''Lipotes vexillifer'') is a probably extinct species of freshwater dolphin native to the Yangtze river system in China. It is thought to be the first dolphin species driven to extinction due to the impact of humans. This dolphin is ...

(Lipotidae

Lipotidae is a family of river dolphins containing the possibly extinct baiji of China and the fossil genus '' Parapontoporia'' from the Late Miocene and Pliocene of the Pacific coast of North America. The genus '' Prolipotes'', which is based on ...

), South American river dolphins (Iniidae

Iniidae is a family of river dolphins containing one living genus, '' Inia'', and four extinct genera. The extant genus inhabits the river basins of South America, but the family formerly had a wider presence across the Atlantic Ocean.

Iniidae ...

), and La Plata dolphin

The La Plata dolphin, franciscana or toninha (''Pontoporia blainvillei'') is a species of river dolphin found in coastal Atlantic waters of southeastern South America. It is a member of the Inioidea group and the only one that lives in the ocean ...

(Pontoporiidae).

Evolution

Whales are descendants of land-dwelling mammals of theartiodactyl

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

(even-toed ungulates). They are related to the ''Indohyus

''Indohyus'' (Meaning "India's pig" from the Greek words ''Indos'', "from India" and ''hûs'', "pig") is an extinct genus of artiodactyl known from Eocene fossils in Asia. This small chevrotain-like animal found in the Himalayas is among the clo ...

'', an extinct chevrotain

Chevrotains, or mouse-deer, are small, even-toed ungulates that make up the family Tragulidae, and are the only living members of the infraorder Tragulina. The 10 extant species are placed in three genera, but several species also ar ...

-like ungulate, from which they split approximately 48 million years ago. Primitive cetaceans, or archaeocetes

Archaeoceti ("ancient whales"), or Zeuglodontes in older literature, is an obsolete paraphyletic group of primitive cetaceans that lived from the Early Eocene to the late Oligocene (). Representing the earliest cetacean radiation, they include th ...

, first took to the sea approximately 49 million years ago and became fully aquatic 5–10 million years later. What defines an archaeocete is the presence of anatomical features exclusive to cetaceans, alongside other primitive features not found in modern cetaceans, such as visible legs or asymmetrical teeth. Their features became adapted for living in the marine environment

A marine habitat is a habitat that supports marine life. Marine life depends in some way on the saltwater that is in the sea (the term ''marine'' comes from the Latin ''mare'', meaning sea or ocean). A habitat is an ecological or environmen ...

. Major anatomical changes included their hearing set-up that channeled vibrations from the jaw to the earbone (''Ambulocetus

''Ambulocetus'' (Latin ''ambulare'' "to walk" + ''cetus'' "whale") is a genus of early Semiaquatic, amphibious cetacean from the Kuldana Formation in Pakistan, roughly 48 or 47 million years ago during the Early Eocene (Lutetian). It contains o ...

'' 49 mya), a streamlined

Streamlines, streaklines and pathlines are field lines in a fluid flow.

They differ only when the flow changes with time, that is, when the flow is not steady flow, steady.

Considering a velocity vector field in three-dimensional space in the f ...

body and the growth of flukes on the tail (''Protocetus

''Protocetus atavus'' ("first whale") is an extinct species of primitive cetacean from Egypt. It lived during the middle Eocene period 45 million years ago. The first discovered protocetid, ''Protocetus atavus'' was described by based on a cran ...

'' 43 mya), the migration of the nostrils toward the top of the cranium

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

( blowholes), and the modification of the forelimbs into flippers (''Basilosaurus

''Basilosaurus'' (meaning "king lizard") is a genus of large, predatory, prehistoric archaeocete whale from the late Eocene, approximately 41.3 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). First described in 1834, it was the first archaeocete and prehisto ...

'' 35 mya), and the shrinking and eventual disappearance of the hind limbs (the first odontocetes and mysticetes 34 mya).

Whale morphology shows several examples of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

, the most obvious being the streamlined fish-like body shape. Other examples include the use of echolocation for hunting in low light conditions — which is the same hearing adaptation used by bat

Bats are flying mammals of the order Chiroptera (). With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most birds, flying with their very long spread-out ...

s — and, in the rorqual whales, jaw adaptations, similar to those found in pelican

Pelicans (genus ''Pelecanus'') are a genus of large water birds that make up the family Pelecanidae. They are characterized by a long beak and a large throat pouch used for catching prey and draining water from the scooped-up contents before ...

s, that enable engulfment feeding.

Today, the closest living relatives of cetaceans are the hippopotamus

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Sahar ...

es; these share a semi-aquatic

In biology, being semi-aquatic refers to various macroorganisms that live regularly in both aquatic and terrestrial environments. When referring to animals, the term describes those that actively spend part of their daily time in water (in ...

ancestor that branched off from other artiodactyls some 60 mya. Around 40 mya, a common ancestor between the two branched off into cetacea and anthracotheres

Anthracotheriidae is a paraphyletic family of extinct, hippopotamus-like artiodactyl ungulates related to hippopotamuses and whales. The oldest genus, '' Elomeryx'', first appeared during the middle Eocene in Asia. They thrived in Africa and Eura ...

; nearly all anthracotheres became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene 2.5 mya, eventually leaving only one surviving lineage – the hippopotamus.

Whales split into two separate parvorders around 34 mya – the baleen whales (Mysticetes) and the toothed whales (Odontocetes).

Biology

Anatomy

Whales have torpedo-shaped bodies with non-flexible necks, limbs modified into flippers, non-existent external ear flaps, a large tail fin, and flat heads (with the exception of monodontids and

Whales have torpedo-shaped bodies with non-flexible necks, limbs modified into flippers, non-existent external ear flaps, a large tail fin, and flat heads (with the exception of monodontids and ziphiids

Beaked whales (systematic name Ziphiidae) are a family of cetaceans noted as being one of the least-known groups of mammals because of their deep-sea habitat, reclusive behavior and apparent low abundance. Only three or four of the 24 existing s ...

). Whale skulls have small eye orbits, long snouts (with the exception of monodontids and ziphiids) and eyes placed on the sides of its head. Whales range in size from the and dwarf sperm whale to the and blue whale. Overall, they tend to dwarf other cetartiodactyls; the blue whale is the largest creature on Earth. Several species have female-biased sexual dimorphism, with the females being larger than the males. One exception is with the sperm whale, which has males larger than the females.

Odontocetes, such as the sperm whale, possess teeth with cementum

Cementum is a specialized calcified substance covering the root of a tooth. The cementum is the part of the periodontium that attaches the teeth to the alveolar bone by anchoring the periodontal ligament.

Structure

The cells of cementum are ...

cells overlying dentine

Dentin ( ) (American English) or dentine ( or ) (British English) () is a calcified tissue of the body and, along with enamel, cementum, and pulp, is one of the four major components of teeth. It is usually covered by enamel on the crown ...

cells. Unlike human teeth, which are composed mostly of enamel on the portion of the tooth outside of the gum, whale teeth have cementum outside the gum. Only in larger whales, where the cementum is worn away on the tip of the tooth, does enamel show. Mysticetes have large whalebone

Baleen is a filter-feeding system inside the mouths of baleen whales. To use baleen, the whale first opens its mouth underwater to take in water. The whale then pushes the water out, and animals such as krill are filtered by the baleen and ...

, as opposed to teeth, made of keratin. Mysticetes have two blowholes, whereas Odontocetes contain only one.

Breathing involves expelling stale air from the blowhole, forming an upward, steamy spout, followed by inhaling fresh air into the lungs; a humpback whale's lungs can hold about of air. Spout shapes differ among species, which facilitates identification.

All whales have a thick layer of blubber

Blubber is a thick layer of Blood vessel, vascularized adipose tissue under the skin of all cetaceans, pinnipeds, penguins, and sirenians. It was present in many marine reptiles, such as Ichthyosauria, ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs.

Description ...

. In species that live near the poles, the blubber can be as thick as . This blubber can help with buoyancy (which is helpful for a 100-ton whale), protection to some extent as predators would have a hard time getting through a thick layer of fat, and energy for fasting when migrating to the equator; the primary usage for blubber is insulation from the harsh climate. It can constitute as much as 50% of a whale's body weight. Calves are born with only a thin layer of blubber, but some species compensate for this with thick lanugos.

Whales have a two- to three-chambered stomach that is similar in structure to those of terrestrial carnivores. Mysticetes contain a proventriculus

The proventriculus is part of the digestive system of birds.Encarta World English Dictionary orth American Edition(2007). ''Proventriculus''. Source: (accessed: December 18, 2007) An analogous organ exists in invertebrates and insects.

Birds

Th ...

as an extension of the oesophagus

The esophagus (American English), oesophagus (British English), or œsophagus ( archaic spelling) ( see spelling difference) all ; : ((o)e)(œ)sophagi or ((o)e)(œ)sophaguses), colloquially known also as the food pipe, food tube, or gullet, ...

; this contains stones that grind up food. They also have fundic and pyloric

The pylorus ( or ) connects the stomach to the duodenum. The pylorus is considered as having two parts, the ''pyloric antrum'' (opening to the body of the stomach) and the ''pyloric canal'' (opening to the duodenum). The ''pyloric canal'' ends a ...

chambers.

Locomotion

Whales have two flippers on the front, and a tail fin. These flippers contain four digits. Although whales do not possess fully developed hind limbs, some, such as the sperm whale and bowhead whale, possess discrete rudimentary appendages, which may contain feet and digits. Whales are fast swimmers in comparison to seals, which typically cruise at 5–15 kn, or ; the fin whale, in comparison, can travel at speeds up to and the sperm whale can reach speeds of . The fusing of the neck vertebrae, while increasing stability when swimming at high speeds, decreases flexibility; whales are unable to turn their heads. When swimming, whales rely on their tail fin to propel them through the water. Flipper movement is continuous. Whales swim by moving their tail fin and lower body up and down, propelling themselves through vertical movement, while their flippers are mainly used for steering. Some species

Whales have two flippers on the front, and a tail fin. These flippers contain four digits. Although whales do not possess fully developed hind limbs, some, such as the sperm whale and bowhead whale, possess discrete rudimentary appendages, which may contain feet and digits. Whales are fast swimmers in comparison to seals, which typically cruise at 5–15 kn, or ; the fin whale, in comparison, can travel at speeds up to and the sperm whale can reach speeds of . The fusing of the neck vertebrae, while increasing stability when swimming at high speeds, decreases flexibility; whales are unable to turn their heads. When swimming, whales rely on their tail fin to propel them through the water. Flipper movement is continuous. Whales swim by moving their tail fin and lower body up and down, propelling themselves through vertical movement, while their flippers are mainly used for steering. Some species log

Log most often refers to:

* Trunk (botany), the stem and main wooden axis of a tree, called logs when cut

** Logging, cutting down trees for logs

** Firewood, logs used for fuel

** Lumber or timber, converted from wood logs

* Logarithm, in mathe ...

out of the water, which may allow them to travel faster. Their skeletal anatomy allows them to be fast swimmers. Most species have a dorsal fin

A dorsal fin is a fin on the back of most marine and freshwater vertebrates. Dorsal fins have evolved independently several times through convergent evolution adapting to marine environments, so the fins are not all homologous. They are found ...

.

Whales are adapted for diving to great depths. In addition to their streamlined bodies, they can slow their heart rate to conserve oxygen; blood is rerouted from tissue tolerant of water pressure to the heart and brain among other organs; haemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin, Hb or Hgb) is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transportation of oxygen in red blood cells. Almost all vertebrates contain hemoglobin, with the sole exception of the fish family Channichthyidae. Hemoglobi ...

and myoglobin

Myoglobin (symbol Mb or MB) is an iron- and oxygen-binding protein found in the cardiac and skeletal muscle, skeletal Muscle, muscle tissue of vertebrates in general and in almost all mammals. Myoglobin is distantly related to hemoglobin. Compar ...

store oxygen in body tissue; and they have twice the concentration of myoglobin than haemoglobin. Before going on long dives, many whales exhibit a behaviour known as sounding; they stay close to the surface for a series of short, shallow dives while building their oxygen reserves, and then make a sounding dive.

Senses

The whale ear has specific adaptations to the marine environment. In humans, the

The whale ear has specific adaptations to the marine environment. In humans, the middle ear

The middle ear is the portion of the ear medial to the eardrum, and distal to the oval window of the cochlea (of the inner ear).

The mammalian middle ear contains three ossicles (malleus, incus, and stapes), which transfer the vibrations ...

works as an impedance equalizer between the outside air's low impedance and the cochlea

The cochlea is the part of the inner ear involved in hearing. It is a spiral-shaped cavity in the bony labyrinth, in humans making 2.75 turns around its axis, the modiolus (cochlea), modiolus. A core component of the cochlea is the organ of Cort ...

r fluid's high impedance. In whales, and other marine mammals, there is no great difference between the outer and inner environments. Instead of sound passing through the outer ear to the middle ear, whales receive sound through the throat, from which it passes through a low-impedance fat-filled cavity to the inner ear. The whale ear is acoustically isolated from the skull by air-filled sinus pockets, which allow for greater directional hearing underwater. Odontocetes send out high-frequency clicks from an organ known as a melon

A melon is any of various plants of the family Cucurbitaceae with sweet, edible, and fleshy fruit. It can also specifically refer to ''Cucumis melo'', commonly known as the "true melon" or simply "melon". The term "melon" can apply to both the p ...

. This melon consists of fat, and the skull of any such creature containing a melon will have a large depression. The melon size varies between species, the bigger the more dependent they are on it. A beaked whale for example has a small bulge sitting on top of its skull, whereas a sperm whale's head is filled up mainly with the melon.

The whale eye is relatively small for its size, yet they do retain a good degree of eyesight. As well as this, the eyes of a whale are placed on the sides of its head, so their vision consists of two fields, rather than a binocular view like humans have. When belugas surface, their lens and cornea correct the nearsightedness that results from the refraction of light; they contain both rod and cone

In geometry, a cone is a three-dimensional figure that tapers smoothly from a flat base (typically a circle) to a point not contained in the base, called the '' apex'' or '' vertex''.

A cone is formed by a set of line segments, half-lines ...

cells, meaning they can see in both dim and bright light, but they have far more rod cells than they do cone cells. Whales do, however, lack short wavelength sensitive visual pigments in their cone cells indicating a more limited capacity for colour vision than most mammals. Most whales have slightly flattened eyeballs, enlarged pupils (which shrink as they surface to prevent damage), slightly flattened corneas and a tapetum lucidum

The ; ; : tapeta lucida) is a layer of tissue in the eye of many vertebrates and some other animals. Lying immediately behind the retina, it is a retroreflector. It Reflection (physics), reflects visible light back through the retina, increas ...

; these adaptations allow for large amounts of light to pass through the eye and, therefore, a very clear image of the surrounding area. They also have glands on the eyelids and outer corneal layer that act as protection for the cornea.

The olfactory lobes are absent in toothed whales, suggesting that they have no sense of smell. Some whales, such as the bowhead whale

The bowhead whale (''Balaena mysticetus''), sometimes called the Greenland right whale, Arctic whale, and polar whale, is a species of baleen whale belonging to the family Balaenidae and is the only living representative of the genus '' Balaena' ...

, possess a vomeronasal organ

The vomeronasal organ (VNO), or Jacobson's organ, is the paired auxiliary olfactory (smell) sense organ located in the soft tissue of the nasal septum, in the nasal cavity just above the roof of the mouth (the hard palate) in various tetrapods ...

, which does mean that they can "sniff out" krill.

Whales are not thought to have a good sense of taste, as their taste buds are atrophied or missing altogether. However, some toothed whales have preferences between different kinds of fish, indicating some sort of attachment to taste. The presence of the Jacobson's organ indicates that whales can smell food once inside their mouth, which might be similar to the sensation of taste.

Communication

Whale vocalization is likely to serve several purposes. Some species, such as the humpback whale, communicate using melodic sounds, known aswhale song

Whales use a variety of sounds for communication and sensation. The mechanisms used to produce sound vary from one family of cetaceans to another. Marine mammals, including whales, dolphins, and porpoises, are much more dependent on sound tha ...

. These sounds may be extremely loud, depending on the species. Humpback whales only have been heard making clicks, while toothed whales use sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances ( ranging), communicate with or detect objects o ...

that may generate up to 20,000 watts of sound (+73 dBm or +43 dBw

The decibel watt (dBW or dBW) is a unit for the measurement of the strength of a signal expressed in decibels relative to one watt. It is used because of its capability to express both very large and very small values of power in a short range of ...

) and be heard for many miles.

Captive whales have occasionally been known to mimic human speech. Scientists have suggested this indicates a strong desire on behalf of the whales to communicate with humans, as whales have a very different vocal mechanism, so imitating human speech likely takes considerable effort.

Whales emit two distinct kinds of acoustic signals, which are called whistles and clicks:

Clicks are quick broadband burst pulses, used for sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances ( ranging), communicate with or detect objects o ...

, although some lower-frequency broadband vocalizations may serve a non-echolocative purpose such as communication; for example, the pulsed calls of belugas. Pulses in a click train are emitted at intervals of ≈35–50 millisecond

A millisecond (from '' milli-'' and second; symbol: ms) is a unit of time in the International System of Units equal to one thousandth (0.001 or 10−3 or 1/1000) of a second or 1000 microseconds.

A millisecond is to one second, as one second i ...

s, and in general these inter-click intervals are slightly greater than the round-trip time of sound to the target.

Whistles are narrow-band frequency modulated (FM) signals, used for communicative purposes, such as contact calls.

Intelligence

Whales are known to teach, learn, cooperate, scheme, and grieve. The neocortex of many species of whale is home to elongatedspindle neurons

Von Economo neurons, also called spindle neurons, are a specific class of mammalian Cerebral cortex, cortical neurons characterized by a large Spindle (textiles), spindle-shaped soma (biology), soma (or body) gradually tapering into a single ap ...

that, prior to 2007, were known only in hominids. In humans, these cells are involved in social conduct, emotions, judgement, and theory of mind. Whale spindle neurons are found in areas of the brain that are homologous to where they are found in humans, suggesting that they perform a similar function.

Brain size

The size of the brain is a frequent topic of study within the fields of anatomy, biological anthropology, animal science and evolution. Measuring brain size and cranial capacity is relevant both to humans and other animals, and can be done by wei ...

was previously considered a major indicator of the intelligence of an animal. Since most of the brain is used for maintaining bodily functions, greater ratios of brain-to-body mass may increase the amount of brain mass available for more complex cognitive tasks. Allometric

Allometry (Ancient Greek "other", "measurement") is the study of the relationship of body size to shape, anatomy, physiology and behaviour, first outlined by Otto Snell in 1892, by D'Arcy Thompson in 1917 in ''On Growth and Form'' and by Juli ...

analysis indicates that mammalian brain size scales at approximately the or exponent of the body mass. Comparison of a particular animal's brain size with the expected brain size based on such allometric analysis provides an encephalisation quotient

Encephalization quotient (EQ), encephalization level (EL), or just encephalization is a relative brain size measure that is defined as the ratio between observed and predicted brain mass for an animal of a given size, based on nonlinear regress ...

that can be used as another indication of animal intelligence. Sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the Genus (biology), genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the s ...

s have the largest brain mass of any animal on Earth, averaging and in mature males, in comparison to the average human brain which averages in mature males. The brain-to-body mass ratio in some odontocetes, such as belugas and narwhals, is second only to humans.

Small whales are known to engage in complex play behaviour, which includes such things as producing stable underwater toroid

In mathematics, a toroid is a surface of revolution with a hole in the middle. The axis of revolution passes through the hole and so does not intersect the surface. For example, when a rectangle is rotated around an axis parallel to one of its ...

al air-core vortex

In fluid dynamics, a vortex (: vortices or vortexes) is a region in a fluid in which the flow revolves around an axis line, which may be straight or curved. Vortices form in stirred fluids, and may be observed in smoke rings, whirlpools in th ...

rings or "bubble ring

A bubble ring, or toroidal bubble, is an underwater vortex ring where an air bubble occupies the core of the vortex, forming a ring shape. The ring of air as well as the nearby water spins Toroidal and poloidal, poloidally as it travels through ...

s". There are two main methods of bubble ring production: rapid puffing of a burst of air into the water and allowing it to rise to the surface, forming a ring, or swimming repeatedly in a circle and then stopping to inject air into the helical vortex currents thus formed. They also appear to enjoy biting the vortex-rings, so that they burst into many separate bubbles and then rise quickly to the surface. Some believe this is a means of communication. Whales are also known to produce bubble-nets for the purpose of foraging.

Larger whales are also thought, to some degree, to engage in play. The southern right whale

The southern right whale (''Eubalaena australis'') is a baleen whale, one of three species classified as right whales belonging to the genus ''Eubalaena''. Southern right whales inhabit oceans south of the Equator, between the latitudes of 20� ...

, for example, elevates their tail fluke above the water, remaining in the same position for a considerable amount of time. This is known as "sailing". It appears to be a form of play and is most commonly seen off the coast of Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

. Humpback whale

The humpback whale (''Megaptera novaeangliae'') is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the monotypic taxon, only species in the genus ''Megaptera''. Adults range in length from and weigh u ...

s, among others, are also known to display this behaviour.

Life cycle

Whales are fully aquatic creatures, which means that birth and courtship behaviours are very different from terrestrial and semi-aquatic creatures. Since they are unable to go onto land to calve, they deliver the baby with the fetus positioned for tail-first delivery. This prevents the baby from drowning either upon or during delivery. To feed the newborn, whales, being aquatic, must squirt the milk into the mouth of the calf. Nursing can occur while the mother whale is in the vertical or horizontal position. While nursing in the vertical position, a mother whale may sometimes rest with her tail flukes remaining stationary above the water. This position with the flukes above the water is known as "whale-tail-sailing." Not all whale-tail-sailing includes nursing of the young, as whales have also been observed tail-sailing while no calves were present.

Being mammals, they have mammary glands used for nursing calves; weaning occurs at about 11 months of age. This milk contains high amounts of fat which is meant to hasten the development of blubber; it contains so much fat that it has the consistency of toothpaste. Like humans, female whales typically deliver a single offspring. Whales have a typical gestation period of 12 months. Once born, the absolute dependency of the calf upon the mother lasts from one to two years. Sexual maturity is achieved at around seven to ten years of age. The length of the developmental phases of a whale's early life varies between different whale species.

As with humans, the whale mode of reproduction typically produces but one offspring approximately once each year. While whales have fewer offspring over time than most species, the probability of survival for each calf is also greater than for most other species. Female whales are referred to as "cows." Cows assume full responsibility for the care and training of their young. Male whales, referred to as "bulls," typically play no role in the process of calf-rearing.

Most baleen whales reside at the poles. To prevent the unborn baleen whale calves from dying of frostbite, the baleen mother must migrate to warmer calving/mating grounds. They will then stay there for a matter of months until the calf has developed enough blubber to survive the bitter temperatures of the poles. Until then, the baleen calves will feed on the mother's fatty milk.

With the exception of the humpback whale, it is largely unknown when whales migrate. Most will travel from the Arctic or Antarctic into the

To feed the newborn, whales, being aquatic, must squirt the milk into the mouth of the calf. Nursing can occur while the mother whale is in the vertical or horizontal position. While nursing in the vertical position, a mother whale may sometimes rest with her tail flukes remaining stationary above the water. This position with the flukes above the water is known as "whale-tail-sailing." Not all whale-tail-sailing includes nursing of the young, as whales have also been observed tail-sailing while no calves were present.

Being mammals, they have mammary glands used for nursing calves; weaning occurs at about 11 months of age. This milk contains high amounts of fat which is meant to hasten the development of blubber; it contains so much fat that it has the consistency of toothpaste. Like humans, female whales typically deliver a single offspring. Whales have a typical gestation period of 12 months. Once born, the absolute dependency of the calf upon the mother lasts from one to two years. Sexual maturity is achieved at around seven to ten years of age. The length of the developmental phases of a whale's early life varies between different whale species.

As with humans, the whale mode of reproduction typically produces but one offspring approximately once each year. While whales have fewer offspring over time than most species, the probability of survival for each calf is also greater than for most other species. Female whales are referred to as "cows." Cows assume full responsibility for the care and training of their young. Male whales, referred to as "bulls," typically play no role in the process of calf-rearing.

Most baleen whales reside at the poles. To prevent the unborn baleen whale calves from dying of frostbite, the baleen mother must migrate to warmer calving/mating grounds. They will then stay there for a matter of months until the calf has developed enough blubber to survive the bitter temperatures of the poles. Until then, the baleen calves will feed on the mother's fatty milk.

With the exception of the humpback whale, it is largely unknown when whales migrate. Most will travel from the Arctic or Antarctic into the tropics

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the equator, where the sun may shine directly overhead. This contrasts with the temperate or polar regions of Earth, where the Sun can never be directly overhead. This is because of Earth's ax ...

to mate, calve, and raise their young during the winter and spring; they will migrate back to the poles in the warmer summer months so the calf can continue growing while the mother can continue eating, as they fast in the breeding grounds. One exception to this is the southern right whale