Visual Kei Musicians on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The visual system comprises the sensory organ (the

A major function of the visual system is to categorize visual objects. It has been shown that humans can per perform categorization in briefly presented images in a fraction of a second. These experiments consisted in asking subjects to categorize images that do or do not contain animals. The results showed that humans were able to perform this task very well (with a success rate of more than 95%) but above all that a differential activity for the two categories of images could be observed by electroencephalography, showing that this differentiation emerges with a very short latency in neural activity. These results have been extended to several species, including primates. Different experimental protocols have shown for example that the motor response could be extremely fast (of the order of 120 ms) when the task was to perform a saccade. This speed of the visual cortex in primates is compatible with the latencies that are recorded at the neuro-physiological level. The rapid propagation of the visual information in the thalamus, then in the primary visual cortex takes about 45 ms in the macaque and about 60 ms in humans. This functioning of visual processing as a forward pass is most prominent in fast processing, and can be complemented with feedback loops from the higher areas to the sensory areas.

A major function of the visual system is to categorize visual objects. It has been shown that humans can per perform categorization in briefly presented images in a fraction of a second. These experiments consisted in asking subjects to categorize images that do or do not contain animals. The results showed that humans were able to perform this task very well (with a success rate of more than 95%) but above all that a differential activity for the two categories of images could be observed by electroencephalography, showing that this differentiation emerges with a very short latency in neural activity. These results have been extended to several species, including primates. Different experimental protocols have shown for example that the motor response could be extremely fast (of the order of 120 ms) when the task was to perform a saccade. This speed of the visual cortex in primates is compatible with the latencies that are recorded at the neuro-physiological level. The rapid propagation of the visual information in the thalamus, then in the primary visual cortex takes about 45 ms in the macaque and about 60 ms in humans. This functioning of visual processing as a forward pass is most prominent in fast processing, and can be complemented with feedback loops from the higher areas to the sensory areas.

* The

* The

The retina consists of many

The retina consists of many

The information about the image via the eye is transmitted to the brain along the

The information about the image via the eye is transmitted to the brain along the

-> at the base of the

The visual cortex is the largest system in the human brain and is responsible for processing the visual image. It lies at the rear of the brain (highlighted in the image), above the

The visual cortex is the largest system in the human brain and is responsible for processing the visual image. It lies at the rear of the brain (highlighted in the image), above the

However, there is still much debate about the degree of specialization within these two pathways, since they are in fact heavily interconnected.

Horace Barlow proposed the '' efficient coding hypothesis'' in 1961 as a theoretical model of sensory coding in the

However, there is still much debate about the degree of specialization within these two pathways, since they are in fact heavily interconnected.

Horace Barlow proposed the '' efficient coding hypothesis'' in 1961 as a theoretical model of sensory coding in the

primary visual cortex (V1)

motivated the

The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks'"

in which the visual system switches from resting state to attention. In the

Proper function of the visual system is required for sensing, processing, and understanding the surrounding environment. Difficulty in sensing, processing and understanding light input has the potential to adversely impact an individual's ability to communicate, learn and effectively complete routine tasks on a daily basis.

In children, early diagnosis and treatment of impaired visual system function is an important factor in ensuring that key social, academic and speech/language developmental milestones are met.

Proper function of the visual system is required for sensing, processing, and understanding the surrounding environment. Difficulty in sensing, processing and understanding light input has the potential to adversely impact an individual's ability to communicate, learn and effectively complete routine tasks on a daily basis.

In children, early diagnosis and treatment of impaired visual system function is an important factor in ensuring that key social, academic and speech/language developmental milestones are met.

Evolution of fan worm eyes (August 1, 2017) Phys.org

/ref> Only higher primate

"Webvision: The Organization of the Retina and Visual System"

– John Moran Eye Center at University of Utah

VisionScience.com

– An online resource for researchers in vision science.

Journal of Vision

– An online, open access journal of vision science.

i-Perception

– An online, open access journal of perception science.

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Visual System Sensory systems

eye

Eyes are organs of the visual system. They provide living organisms with vision, the ability to receive and process visual detail, as well as enabling several photo response functions that are independent of vision. Eyes detect light and conv ...

) and parts of the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all p ...

(the retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

containing photoreceptor cell

A photoreceptor cell is a specialized type of neuroepithelial cell found in the retina that is capable of visual phototransduction. The great biological importance of photoreceptors is that they convert light (visible electromagnetic radiati ...

s, the optic nerve

In neuroanatomy, the optic nerve, also known as the second cranial nerve, cranial nerve II, or simply CN II, is a paired cranial nerve that transmits visual information from the retina to the brain. In humans, the optic nerve is derived fro ...

, the optic tract and the visual cortex

The visual cortex of the brain is the area of the cerebral cortex that processes visual information. It is located in the occipital lobe. Sensory input originating from the eyes travels through the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus and ...

) which gives organism

In biology, an organism () is any life, living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy (biology), taxonomy into groups such as Multicellular o ...

s the sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the world through the detection of stimuli. (For example, in the human body, the brain which is part of the central nervous system rec ...

of sight

Visual perception is the ability to interpret the surrounding environment through photopic vision (daytime vision), color vision, scotopic vision (night vision), and mesopic vision (twilight vision), using light in the visible spectrum refl ...

(the ability to detect and process visible light

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm), corresponding to frequencies of 750–420 tera ...

) as well as enabling the formation of several non-image photo response functions. It detects and interprets information from the optical spectrum

The visible spectrum is the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visible to the human eye. Electromagnetic radiation in this range of wavelengths is called '' visible light'' or simply light. A typical human eye will respond to wa ...

perceptible to that species to "build a representation" of the surrounding environment. The visual system carries out a number of complex tasks, including the reception of light and the formation of monocular neural representations, colour vision, the neural mechanisms underlying stereopsis

Stereopsis () is the component of depth perception retrieved through binocular vision.

Stereopsis is not the only contributor to depth perception, but it is a major one. Binocular vision happens because each eye receives a different image becaus ...

and assessment of distances to and between objects, the identification of a particular object of interest, motion perception

Motion perception is the process of inferring the speed and direction of elements in a scene based on visual, vestibular and proprioceptive inputs. Although this process appears straightforward to most observers, it has proven to be a difficult ...

, the analysis and integration of visual information, pattern recognition

Pattern recognition is the automated recognition of patterns and regularities in data. It has applications in statistical data analysis, signal processing, image analysis, information retrieval, bioinformatics, data compression, computer graphic ...

, accurate motor coordination Motor coordination is the orchestrated movement of multiple body parts as required to accomplish intended actions, like walking. This coordination is achieved by adjusting kinematic and kinetic parameters associated with each body part involved i ...

under visual guidance, and more. The neuropsychological

Neuropsychology is a branch of psychology concerned with how a person's cognition and behavior are related to the brain and the rest of the nervous system. Professionals in this branch of psychology often focus on how injuries or illnesses of ...

side of visual information processing is known as visual perception

Visual perception is the ability to interpret the surrounding environment through photopic vision (daytime vision), color vision, scotopic vision (night vision), and mesopic vision (twilight vision), using light in the visible spectrum refl ...

, an abnormality of which is called visual impairment

Visual impairment, also known as vision impairment, is a medical definition primarily measured based on an individual's better eye visual acuity; in the absence of treatment such as correctable eyewear, assistive devices, and medical treatment� ...

, and a complete absence of which is called blindness

Visual impairment, also known as vision impairment, is a medical definition primarily measured based on an individual's better eye visual acuity; in the absence of treatment such as correctable eyewear, assistive devices, and medical treatment� ...

. Non-image forming visual functions, independent of visual perception, include (among others) the pupillary light reflex

The pupillary light reflex (PLR) or photopupillary reflex is a reflex that controls the diameter of the pupil, in response to the intensity ( luminance) of light that falls on the retinal ganglion cells of the retina in the back of the eye, the ...

and circadian photoentrainment.

This article mostly describes the visual system of mammals, humans in particular, although other animals have similar visual systems (see bird vision

Vision is the most important sense for birds, since good eyesight is essential for safe flight. Birds have a number of adaptations which give visual acuity superior to that of other vertebrate groups; a pigeon has been described as "two eyes with ...

, vision in fish, mollusc eye, and reptile vision).

System overview

Mechanical

Together, thecornea

The cornea is the transparent front part of the eye that covers the iris, pupil, and anterior chamber. Along with the anterior chamber and lens, the cornea refracts light, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the eye's total optical ...

and lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements'' ...

refract light into a small image and shine it on the retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

. The retina transduces this image into electrical pulses using rods and cones. The optic nerve

In neuroanatomy, the optic nerve, also known as the second cranial nerve, cranial nerve II, or simply CN II, is a paired cranial nerve that transmits visual information from the retina to the brain. In humans, the optic nerve is derived fro ...

then carries these pulses through the optic canal. Upon reaching the optic chiasm the nerve fibers decussate (left becomes right). The fibers then branch and terminate in three places.

Neural

Most of the optic nerve fibers end in thelateral geniculate nucleus

In neuroanatomy, the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN; also called the lateral geniculate body or lateral geniculate complex) is a structure in the thalamus and a key component of the mammalian visual pathway. It is a small, ovoid, ventral proj ...

(LGN). Before the LGN forwards the pulses to V1 of the visual cortex (primary) it gauges the range of objects and tags every major object with a velocity tag. These tags predict object movement.

The LGN also sends some fibers to V2 and V3.

V1 performs edge-detection to understand spatial organization (initially, 40 milliseconds in, focusing on even small spatial and color changes. Then, 100 milliseconds in, upon receiving the translated LGN, V2, and V3 info, also begins focusing on global organization). V1 also creates a bottom-up saliency map to guide attention or gaze shift.

V2 both forwards (direct and via pulvinar) pulses to V1 and receives them. Pulvinar is responsible for saccade and visual attention. V2 serves much the same function as V1, however, it also handles illusory contours

Illusory contours or subjective contours are visual illusions that evoke the perception of an edge without a luminance or color change across that edge. Illusory brightness and depth ordering often accompany illusory contours. Friedrich Schumann i ...

, determining depth by comparing left and right pulses (2D images), and foreground distinguishment. V2 connects to V1 - V5.

V3 helps process ‘ global motion’ (direction and speed) of objects. V3 connects to V1 (weak), V2, and the inferior temporal cortex.

V4 recognizes simple shapes, and gets input from V1 (strong), V2, V3, LGN, and pulvinar. V5’s outputs include V4 and its surrounding area, and eye-movement motor cortices ( frontal eye-field and lateral intraparietal area).

V5’s functionality is similar to that of the other V’s, however, it integrates local object motion into global motion on a complex level. V6 works in conjunction with V5 on motion analysis. V5 analyzes self-motion, whereas V6 analyzes motion of objects relative to the background. V6’s primary input is V1, with V5 additions. V6 houses the topographical map for vision. V6 outputs to the region directly around it (V6A). V6A has direct connections to arm-moving cortices, including the premotor cortex

The premotor cortex is an area of the motor cortex lying within the frontal lobe of the brain just anterior to the primary motor cortex. It occupies part of Brodmann's area 6. It has been studied mainly in primates, including monkeys and huma ...

.

The inferior temporal gyrus recognizes complex shapes, objects, and faces or, in conjunction with the hippocampus

The hippocampus (via Latin from Greek , ' seahorse') is a major component of the brain of humans and other vertebrates. Humans and other mammals have two hippocampi, one in each side of the brain. The hippocampus is part of the limbic system, ...

, creates new memories. The pretectal area

In neuroanatomy, the pretectal area, or pretectum, is a midbrain structure composed of seven nuclei and comprises part of the subcortical visual system. Through reciprocal bilateral projections from the retina, it is involved primarily in mediat ...

is seven unique nuclei. Anterior, posterior and medial pretectal nuclei inhibit pain (indirectly), aid in REM

Rem or REM may refer to:

Music

* R.E.M., an American rock band

* ''R.E.M.'' (EP), by Green

* "R.E.M." (song), by Ariana Grande

Organizations

* La République En Marche!, a French centrist political party

* Reichserziehungsministerium, in Nazi G ...

, and aid the accommodation reflex, respectively. The Edinger-Westphal nucleus moderates pupil dilation and aids (since it provides parasympathetic fibers) in convergence of the eyes and lens adjustment. Nuclei of the optic tract are involved in smooth pursuit eye movement and the accommodation reflex, as well as REM.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus

The suprachiasmatic nucleus or nuclei (SCN) is a tiny region of the brain in the hypothalamus, situated directly above the optic chiasm. It is responsible for controlling circadian rhythms. The neuronal and hormonal activities it generates regul ...

is the region of the hypothalamus

The hypothalamus () is a part of the brain that contains a number of small nuclei with a variety of functions. One of the most important functions is to link the nervous system to the endocrine system via the pituitary gland. The hypothalamus ...

that halts production of melatonin

Melatonin is a natural product found in plants and animals. It is primarily known in animals as a hormone released by the pineal gland in the brain at night, and has long been associated with control of the sleep–wake cycle.

In vertebrat ...

(indirectly) at first light.

Functions

Visual categorization

A major function of the visual system is to categorize visual objects. It has been shown that humans can per perform categorization in briefly presented images in a fraction of a second. These experiments consisted in asking subjects to categorize images that do or do not contain animals. The results showed that humans were able to perform this task very well (with a success rate of more than 95%) but above all that a differential activity for the two categories of images could be observed by electroencephalography, showing that this differentiation emerges with a very short latency in neural activity. These results have been extended to several species, including primates. Different experimental protocols have shown for example that the motor response could be extremely fast (of the order of 120 ms) when the task was to perform a saccade. This speed of the visual cortex in primates is compatible with the latencies that are recorded at the neuro-physiological level. The rapid propagation of the visual information in the thalamus, then in the primary visual cortex takes about 45 ms in the macaque and about 60 ms in humans. This functioning of visual processing as a forward pass is most prominent in fast processing, and can be complemented with feedback loops from the higher areas to the sensory areas.

A major function of the visual system is to categorize visual objects. It has been shown that humans can per perform categorization in briefly presented images in a fraction of a second. These experiments consisted in asking subjects to categorize images that do or do not contain animals. The results showed that humans were able to perform this task very well (with a success rate of more than 95%) but above all that a differential activity for the two categories of images could be observed by electroencephalography, showing that this differentiation emerges with a very short latency in neural activity. These results have been extended to several species, including primates. Different experimental protocols have shown for example that the motor response could be extremely fast (of the order of 120 ms) when the task was to perform a saccade. This speed of the visual cortex in primates is compatible with the latencies that are recorded at the neuro-physiological level. The rapid propagation of the visual information in the thalamus, then in the primary visual cortex takes about 45 ms in the macaque and about 60 ms in humans. This functioning of visual processing as a forward pass is most prominent in fast processing, and can be complemented with feedback loops from the higher areas to the sensory areas.

Structure

eye

Eyes are organs of the visual system. They provide living organisms with vision, the ability to receive and process visual detail, as well as enabling several photo response functions that are independent of vision. Eyes detect light and conv ...

, especially the retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

* The optic nerve

In neuroanatomy, the optic nerve, also known as the second cranial nerve, cranial nerve II, or simply CN II, is a paired cranial nerve that transmits visual information from the retina to the brain. In humans, the optic nerve is derived fro ...

* The optic chiasma

* The optic tract

* The lateral geniculate body

* The optic radiation

* The visual cortex

The visual cortex of the brain is the area of the cerebral cortex that processes visual information. It is located in the occipital lobe. Sensory input originating from the eyes travels through the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus and ...

* The visual association cortex.

These are components of the visual pathway also called the optic pathway that can be divided into anterior and posterior visual pathways. The anterior visual pathway refers to structures involved in vision before the lateral geniculate nucleus

In neuroanatomy, the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN; also called the lateral geniculate body or lateral geniculate complex) is a structure in the thalamus and a key component of the mammalian visual pathway. It is a small, ovoid, ventral proj ...

. The posterior visual pathway refers to structures after this point.

Eye

Light entering the eye is refracted as it passes through thecornea

The cornea is the transparent front part of the eye that covers the iris, pupil, and anterior chamber. Along with the anterior chamber and lens, the cornea refracts light, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the eye's total optical ...

. It then passes through the pupil

The pupil is a black hole located in the center of the iris of the eye that allows light to strike the retina.Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. (1990) ''Dictionary of Eye Terminology''. Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing Company. It appears black ...

(controlled by the iris) and is further refracted by the lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements'' ...

. The cornea and lens act together as a compound lens to project an inverted image onto the retina.

Retina

The retina consists of many

The retina consists of many photoreceptor cell

A photoreceptor cell is a specialized type of neuroepithelial cell found in the retina that is capable of visual phototransduction. The great biological importance of photoreceptors is that they convert light (visible electromagnetic radiati ...

s which contain particular protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respon ...

molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bio ...

s called opsin

Animal opsins are G-protein-coupled receptors and a group of proteins made light-sensitive via a chromophore, typically retinal. When bound to retinal, opsins become Retinylidene proteins, but are usually still called opsins regardless. Most pro ...

s. In humans, two types of opsins are involved in conscious vision: rod opsins and cone opsins. (A third type, melanopsin

Melanopsin is a type of photopigment belonging to a larger family of light-sensitive retinal proteins called opsins and encoded by the gene ''Opn4''. In the mammalian retina, there are two additional categories of opsins, both involved in the fo ...

in some retinal ganglion cells (RGC), part of the body clock mechanism, is probably not involved in conscious vision, as these RGC do not project to the lateral geniculate nucleus

In neuroanatomy, the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN; also called the lateral geniculate body or lateral geniculate complex) is a structure in the thalamus and a key component of the mammalian visual pathway. It is a small, ovoid, ventral proj ...

but to the pretectal olivary nucleus.) An opsin absorbs a photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are Massless particle, massless ...

(a particle of light) and transmits a signal to the cell through a signal transduction pathway, resulting in hyper-polarization of the photoreceptor.

Rods and cones differ in function. Rods are found primarily in the periphery of the retina and are used to see at low levels of light. Each human eye contains 120 million rods. Cones are found primarily in the center (or fovea

Fovea () (Latin for "pit"; plural foveae ) is a term in anatomy. It refers to a pit or depression in a structure.

Human anatomy

* Fovea centralis of the retina

* Fovea buccalis or Dimple

* Fovea of the femoral head

*Trochlear fovea of the f ...

) of the retina. There are three types of cones that differ in the wavelengths of light they absorb; they are usually called short or blue, middle or green, and long or red. Cones mediate day vision and can distinguish color

Color (American English) or colour (British English) is the visual perceptual property deriving from the spectrum of light interacting with the photoreceptor cells of the eyes. Color categories and physical specifications of color are assoc ...

and other features of the visual world at medium and high light levels. Cones are larger and much less numerous than rods (there are 6-7 million of them in each human eye).

In the retina, the photoreceptors synapse

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that permits a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or to the target effector cell.

Synapses are essential to the transmission of nervous impulses fr ...

directly onto bipolar cell

A bipolar neuron, or bipolar cell, is a type of neuron that has two extensions (one axon and one dendrite). Many bipolar cells are specialized sensory neurons for the transmission of sense. As such, they are part of the sensory pathways for sme ...

s, which in turn synapse onto ganglion cells of the outermost layer, which then conduct action potentials

An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific cell location rapidly rises and falls. This depolarization then causes adjacent locations to similarly depolarize. Action potentials occur in several types of animal cells, ...

to the brain

The brain is an organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head ( cephalization), usually near organs for special ...

. A significant amount of visual processing

Visual processing is a term that is used to refer to the brain's ability to use and interpret visual information from the world around us. The process of converting light energy into a meaningful image is a complex process that is facilitated by ...

arises from the patterns of communication between neuron

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, electrically excitable cell (biology), cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous ...

s in the retina. About 130 million photo-receptors absorb light, yet roughly 1.2 million axons

An axon (from Greek ἄξων ''áxōn'', axis), or nerve fiber (or nerve fibre: see spelling differences), is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell, or neuron, in vertebrates, that typically conducts electrical impulses known as action po ...

of ganglion cells transmit information from the retina to the brain. The processing in the retina includes the formation of center-surround receptive fields

The receptive field, or sensory space, is a delimited medium where some physiological stimuli can evoke a sensory neuronal response in specific organisms.

Complexity of the receptive field ranges from the unidimensional chemical structure of od ...

of bipolar and ganglion cells in the retina, as well as convergence and divergence from photoreceptor to bipolar cell. In addition, other neurons in the retina, particularly horizontal

Horizontal may refer to:

*Horizontal plane, in astronomy, geography, geometry and other sciences and contexts

*Horizontal coordinate system, in astronomy

*Horizontalism, in monetary circuit theory

*Horizontalism, in sociology

*Horizontal market, ...

and amacrine cells, transmit information laterally (from a neuron in one layer to an adjacent neuron in the same layer), resulting in more complex receptive fields that can be either indifferent to color and sensitive to motion

In physics, motion is the phenomenon in which an object changes its position with respect to time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed and frame of reference to an observer and mea ...

or sensitive to color and indifferent to motion.

= Mechanism of generating visual signals

= The retina adapts to change in light through the use of the rods. In the dark, thechromophore

A chromophore is the part of a molecule responsible for its color.

The color that is seen by our eyes is the one not absorbed by the reflecting object within a certain wavelength spectrum of visible light. The chromophore is a region in the molec ...

retinal

Retinal (also known as retinaldehyde) is a polyene chromophore. Retinal, bound to proteins called opsins, is the chemical basis of visual phototransduction, the light-detection stage of visual perception (vision).

Some microorganisms use re ...

has a bent shape called cis-retinal (referring to a ''cis'' conformation in one of the double bonds). When light interacts with the retinal, it changes conformation to a straight form called trans-retinal and breaks away from the opsin. This is called bleaching because the purified rhodopsin

Rhodopsin, also known as visual purple, is a protein encoded by the RHO gene and a G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR). It is the opsin of the rod cells in the retina and a light-sensitive receptor protein that triggers visual phototransduct ...

changes from violet to colorless in the light. At baseline in the dark, the rhodopsin absorbs no light and releases glutamate

Glutamic acid (symbol Glu or E; the ionic form is known as glutamate) is an α-amino acid that is used by almost all living beings in the biosynthesis of proteins. It is a non-essential nutrient for humans, meaning that the human body can syn ...

, which inhibits the bipolar cell. This inhibits the release of neurotransmitters from the bipolar cells to the ganglion cell. When there is light present, glutamate secretion ceases, thus no longer inhibiting the bipolar cell from releasing neurotransmitters to the ganglion cell and therefore an image can be detected.

The final result of all this processing is five different populations of ganglion cells that send visual (image-forming and non-image-forming) information to the brain:

#M cells, with large center-surround receptive fields that are sensitive to depth, indifferent to color, and rapidly adapt to a stimulus;

#P cells, with smaller center-surround receptive fields that are sensitive to color and shape

A shape or figure is a graphical representation of an object or its external boundary, outline, or external surface, as opposed to other properties such as color, texture, or material type.

A plane shape or plane figure is constrained to lie on ...

;

#K cells, with very large center-only receptive fields that are sensitive to color and indifferent to shape or depth;

# another population that is intrinsically photosensitive; and

#a final population that is used for eye movements.

A 2006 University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universit ...

study calculated the approximate bandwidth of human retinas to be about 8960 kilobits per second, whereas guinea pig

The guinea pig or domestic guinea pig (''Cavia porcellus''), also known as the cavy or domestic cavy (), is a species of rodent belonging to the genus '' Cavia'' in the family Caviidae. Breeders tend to use the word ''cavy'' to describe the ...

retinas transfer at about 875 kilobits.

In 2007 Zaidi and co-researchers on both sides of the Atlantic studying patients without rods and cones, discovered that the novel photoreceptive ganglion cell in humans also has a role in conscious and unconscious visual perception. The peak spectral sensitivity was 481 nm. This shows that there are two pathways for sight in the retina – one based on classic photoreceptors (rods and cones) and the other, newly discovered, based on photo-receptive ganglion cells which act as rudimentary visual brightness detectors.

Photochemistry

The functioning of acamera

A camera is an optical instrument that can capture an image. Most cameras can capture 2D images, with some more advanced models being able to capture 3D images. At a basic level, most cameras consist of sealed boxes (the camera body), with a ...

is often compared with the workings of the eye, mostly since both focus light from external objects in the field of view

The field of view (FoV) is the extent of the observable world that is seen at any given moment. In the case of optical instruments or sensors it is a solid angle through which a detector is sensitive to electromagnetic radiation.

Humans a ...

onto a light-sensitive medium. In the case of the camera, this medium is film or an electronic sensor; in the case of the eye, it is an array of visual receptors. With this simple geometrical similarity, based on the laws of optics, the eye functions as a transducer

A transducer is a device that converts energy from one form to another. Usually a transducer converts a signal in one form of energy to a signal in another.

Transducers are often employed at the boundaries of automation, measurement, and cont ...

, as does a CCD camera.

In the visual system, retinal, technically called '' retinene''1 or "retinaldehyde", is a light-sensitive molecule found in the rods and cones of the retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

. Retinal is the fundamental structure involved in the transduction of light

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm), corresponding to frequencies of 750–420 te ...

into visual signals, i.e. nerve impulses in the ocular system of the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all p ...

. In the presence of light, the retinal molecule changes configuration and as a result, a nerve impulse is generated.

Optic nerve

The information about the image via the eye is transmitted to the brain along the

The information about the image via the eye is transmitted to the brain along the optic nerve

In neuroanatomy, the optic nerve, also known as the second cranial nerve, cranial nerve II, or simply CN II, is a paired cranial nerve that transmits visual information from the retina to the brain. In humans, the optic nerve is derived fro ...

. Different populations of ganglion cells in the retina send information to the brain through the optic nerve. About 90% of the axons

An axon (from Greek ἄξων ''áxōn'', axis), or nerve fiber (or nerve fibre: see spelling differences), is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell, or neuron, in vertebrates, that typically conducts electrical impulses known as action po ...

in the optic nerve go to the lateral geniculate nucleus

In neuroanatomy, the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN; also called the lateral geniculate body or lateral geniculate complex) is a structure in the thalamus and a key component of the mammalian visual pathway. It is a small, ovoid, ventral proj ...

in the thalamus

The thalamus (from Greek θάλαμος, "chamber") is a large mass of gray matter located in the dorsal part of the diencephalon (a division of the forebrain). Nerve fibers project out of the thalamus to the cerebral cortex in all direction ...

. These axons originate from the M, P, and K ganglion cells in the retina, see above. This parallel processing is important for reconstructing the visual world; each type of information will go through a different route to perception

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system, ...

. Another population sends information to the superior colliculus

In neuroanatomy, the superior colliculus () is a structure lying on the roof of the mammalian midbrain. In non-mammalian vertebrates, the homologous structure is known as the optic tectum, or optic lobe. The adjective form '' tectal'' is commo ...

in the midbrain

The midbrain or mesencephalon is the forward-most portion of the brainstem and is associated with vision, hearing, motor control, sleep and wakefulness, arousal ( alertness), and temperature regulation. The name comes from the Greek ''mesos'', " ...

, which assists in controlling eye movements ( saccades) as well as other motor responses.

A final population of photosensitive ganglion cell

Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs), also called photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (pRGC), or melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells (mRGCs), are a type of neuron in the retina of the mammalian eye. The presence ...

s, containing melanopsin

Melanopsin is a type of photopigment belonging to a larger family of light-sensitive retinal proteins called opsins and encoded by the gene ''Opn4''. In the mammalian retina, there are two additional categories of opsins, both involved in the fo ...

for photosensitivity Photosensitivity is the amount to which an object reacts upon receiving photons, especially visible light. In medicine, the term is principally used for abnormal reactions of the skin, and two types are distinguished, photoallergy and phototoxici ...

, sends information via the retinohypothalamic tract

In neuroanatomy, the retinohypothalamic tract (RHT) is a photic neural input pathway involved in the circadian rhythms of mammals. The origin of the retinohypothalamic tract is the intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGC), ...

to the pretectum (pupillary reflex Pupillary reflex refers to one of the reflexes associated with pupillary function.

These include the pupillary light reflex and accommodation reflex. Although the pupillary response, in which the pupil dilates or constricts due to light is not ...

), to several structures involved in the control of circadian rhythms and sleep

Sleep is a sedentary state of mind and body. It is characterized by altered consciousness, relatively inhibited Perception, sensory activity, reduced muscle activity and reduced interactions with surroundings. It is distinguished from wakefuln ...

such as the suprachiasmatic nucleus

The suprachiasmatic nucleus or nuclei (SCN) is a tiny region of the brain in the hypothalamus, situated directly above the optic chiasm. It is responsible for controlling circadian rhythms. The neuronal and hormonal activities it generates regul ...

(the biological clock), and to the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (a region involved in sleep regulation). A recently discovered role for photoreceptive ganglion cells is that they mediate conscious and unconscious vision – acting as rudimentary visual brightness detectors as shown in rodless coneless eyes.

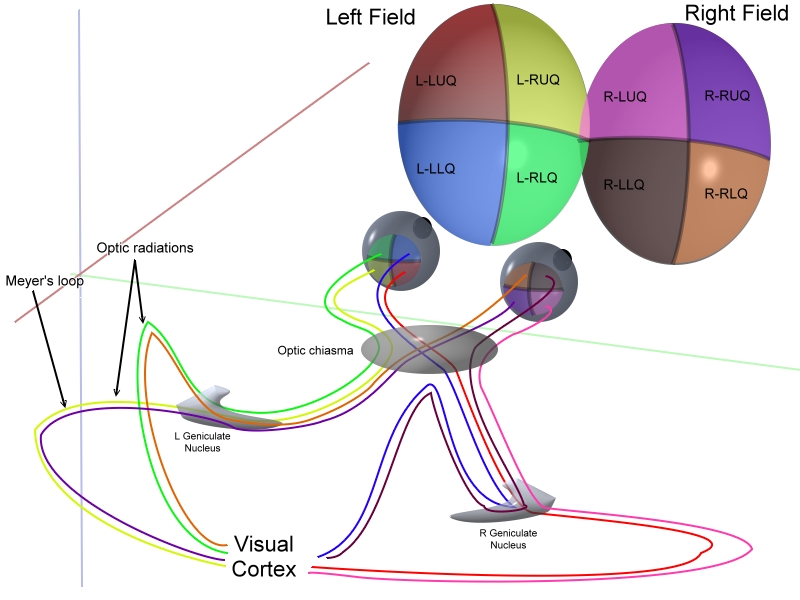

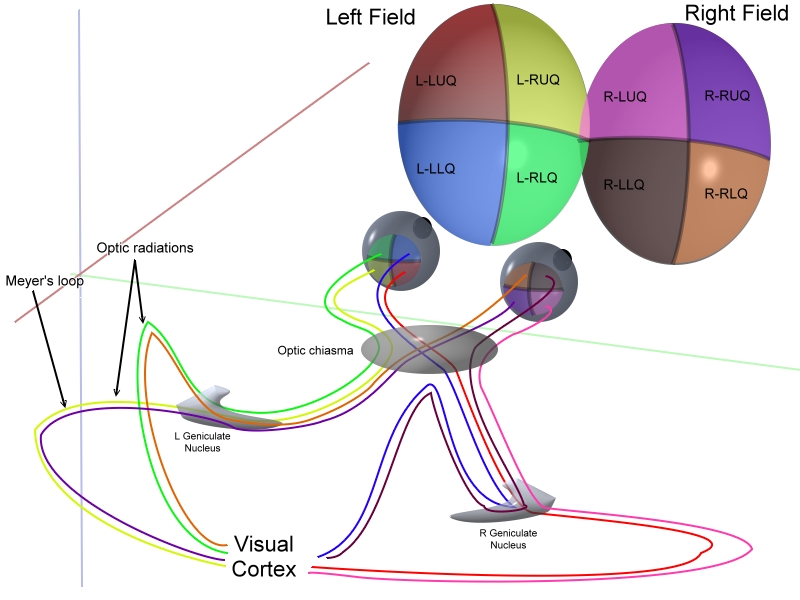

Optic chiasm

The optic nerves from both eyes meet and cross at the optic chiasm,Another link to al-Haytham's sketch of optic chiasm-> at the base of the

hypothalamus

The hypothalamus () is a part of the brain that contains a number of small nuclei with a variety of functions. One of the most important functions is to link the nervous system to the endocrine system via the pituitary gland. The hypothalamus ...

of the brain. At this point, the information coming from both eyes is combined and then splits according to the visual field

The visual field is the "spatial array of visual sensations available to observation in introspectionist psychological experiments". Or simply, visual field can be defined as the entire area that can be seen when an eye is fixed straight at a point ...

. The corresponding halves of the field of view (right and left) are sent to the left and right halves of the brain, respectively, to be processed. That is, the right side of primary visual cortex

The visual cortex of the brain is the area of the cerebral cortex that processes visual information. It is located in the occipital lobe. Sensory input originating from the eyes travels through the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus and ...

deals with the left half of the ''field of view'' from both eyes, and similarly for the left brain. A small region in the center of the field of view is processed redundantly by both halves of the brain.

Optic tract

Information from the right ''visual field'' (now on the left side of the brain) travels in the left optic tract. Information from the left ''visual field'' travels in the right optic tract. Each optic tract terminates in thelateral geniculate nucleus

In neuroanatomy, the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN; also called the lateral geniculate body or lateral geniculate complex) is a structure in the thalamus and a key component of the mammalian visual pathway. It is a small, ovoid, ventral proj ...

(LGN) in the thalamus.

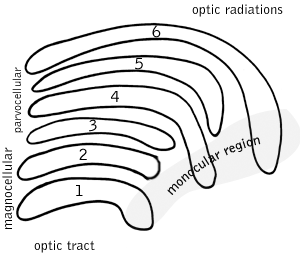

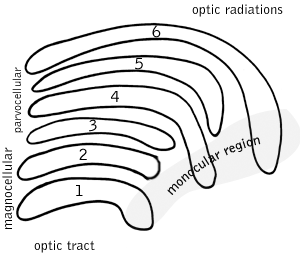

Lateral geniculate nucleus

: The lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) is a sensory relay nucleus in the thalamus of the brain. The LGN consists of six layers inhuman

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

s and other primate

Primates are a diverse order (biology), order of mammals. They are divided into the Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the Haplorhini, haplorhines, which include the Tarsiiformes, tarsiers and ...

s starting from catarrhines, including cercopithecidae and apes

Apes (collectively Hominoidea ) are a clade of Old World simians native to sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (though they were more widespread in Africa, most of Asia, and as well as Europe in prehistory), which together with its sister ...

. Layers 1, 4, and 6 correspond to information from the contralateral (crossed) fibers of the nasal retina (temporal visual field); layers 2, 3, and 5 correspond to information

Information is an abstract concept that refers to that which has the power to inform. At the most fundamental level information pertains to the interpretation of that which may be sensed. Any natural process that is not completely random, ...

from the ipsilateral (uncrossed) fibers of the temporal retina (nasal visual field). Layer one contains M cells, which correspond to the M ( magnocellular) cells of the optic nerve of the opposite eye and are concerned with depth or motion. Layers four and six of the LGN also connect to the opposite eye, but to the P cells (color and edges) of the optic nerve. By contrast, layers two, three and five of the LGN connect to the M cells and P ( parvocellular) cells of the optic nerve for the same side of the brain as its respective LGN. Spread out, the six layers of the LGN are the area of a credit card

A credit card is a payment card issued to users (cardholders) to enable the cardholder to pay a merchant for goods and services based on the cardholder's accrued debt (i.e., promise to the card issuer to pay them for the amounts plus the o ...

and about three times its thickness. The LGN is rolled up into two ellipsoids

An ellipsoid is a surface that may be obtained from a sphere by deforming it by means of directional scalings, or more generally, of an affine transformation.

An ellipsoid is a quadric surface; that is, a surface that may be defined as the ...

about the size and shape of two small birds' eggs. In between the six layers are smaller cells that receive information from the K cells (color) in the retina. The neurons of the LGN then relay the visual image to the primary visual cortex

The visual cortex of the brain is the area of the cerebral cortex that processes visual information. It is located in the occipital lobe. Sensory input originating from the eyes travels through the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus and ...

(V1) which is located at the back of the brain ( posterior end) in the occipital lobe

The occipital lobe is one of the four major lobes of the cerebral cortex in the brain of mammals. The name derives from its position at the back of the head, from the Latin ''ob'', "behind", and ''caput'', "head".

The occipital lobe is the v ...

in and close to the calcarine sulcus. The LGN is not just a simple relay station, but it is also a center for processing; it receives reciprocal input from the cortical and subcortical layers and reciprocal innervation from the visual cortex.

Optic radiation

The optic radiations, one on each side of the brain, carry information from the thalamiclateral geniculate nucleus

In neuroanatomy, the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN; also called the lateral geniculate body or lateral geniculate complex) is a structure in the thalamus and a key component of the mammalian visual pathway. It is a small, ovoid, ventral proj ...

to layer 4 of the visual cortex

The visual cortex of the brain is the area of the cerebral cortex that processes visual information. It is located in the occipital lobe. Sensory input originating from the eyes travels through the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus and ...

. The P layer neurons of the LGN relay to V1 layer 4C β. The M layer neurons relay to V1 layer 4C α. The K layer neurons in the LGN relay to large neurons called blobs in layers 2 and 3 of V1.

There is a direct correspondence from an angular position in the visual field

The visual field is the "spatial array of visual sensations available to observation in introspectionist psychological experiments". Or simply, visual field can be defined as the entire area that can be seen when an eye is fixed straight at a point ...

of the eye, all the way through the optic tract to a nerve position in V1 (up to V4, i.e. the primary visual areas. After that, the visual pathway is roughly separated into a ventral and dorsal pathway).

Visual cortex

The visual cortex is the largest system in the human brain and is responsible for processing the visual image. It lies at the rear of the brain (highlighted in the image), above the

The visual cortex is the largest system in the human brain and is responsible for processing the visual image. It lies at the rear of the brain (highlighted in the image), above the cerebellum

The cerebellum (Latin for "little brain") is a major feature of the hindbrain of all vertebrates. Although usually smaller than the cerebrum, in some animals such as the mormyrid fishes it may be as large as or even larger. In humans, the cere ...

. The region that receives information directly from the LGN is called the primary visual cortex

The visual cortex of the brain is the area of the cerebral cortex that processes visual information. It is located in the occipital lobe. Sensory input originating from the eyes travels through the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus and ...

, (also called V1 and striate cortex). It creates a bottom-up saliency map of the visual field to guide attention or eye gaze to salient visual locations, hence selection of visual input information by attention starts at V1 along the visual pathway. Visual information then flows through a cortical hierarchy. These areas include V2, V3, V4 and area V5/MT (the exact connectivity depends on the species of the animal). These secondary visual areas (collectively termed the extrastriate visual cortex) process a wide variety of visual primitives. Neurons in V1 and V2 respond selectively to bars of specific orientations, or combinations of bars. These are believed to support edge and corner detection. Similarly, basic information about color and motion is processed here.

Heider, et al. (2002) have found that neurons involving V1, V2, and V3 can detect stereoscopic illusory contours

Illusory contours or subjective contours are visual illusions that evoke the perception of an edge without a luminance or color change across that edge. Illusory brightness and depth ordering often accompany illusory contours. Friedrich Schumann i ...

; they found that stereoscopic stimuli subtending up to 8° can activate these neurons.

Visual association cortex

As visual information passes forward through the visual hierarchy, the complexity of the neural representations increases. Whereas a V1 neuron may respond selectively to a line segment of a particular orientation in a particular retinotopic location, neurons in the lateral occipital complex respond selectively to complete object (e.g., a figure drawing), and neurons in visual association cortex may respond selectively to human faces, or to a particular object. Along with this increasing complexity of neural representation may come a level of specialization of processing into two distinct pathways: the dorsal stream and theventral stream

The two-streams hypothesis is a model of the neural processing of vision as well as hearing. The hypothesis, given its initial characterisation in a paper by David Milner and Melvyn A. Goodale in 1992, argues that humans possess two distinct visua ...

(the Two Streams hypothesis

The two-streams hypothesis is a model of the neural processing of visual perception, vision as well as Hearing (sense), hearing. The hypothesis, given its initial characterisation in a paper by David Milner and Melvyn A. Goodale in 1992, argues tha ...

, first proposed by Ungerleider and Mishkin in 1982). The dorsal stream, commonly referred to as the "where" stream, is involved in spatial attention (covert and overt), and communicates with regions that control eye movements and hand movements. More recently, this area has been called the "how" stream to emphasize its role in guiding behaviors to spatial locations. The ventral stream, commonly referred to as the "what" stream, is involved in the recognition, identification and categorization of visual stimuli.

brain

The brain is an organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head ( cephalization), usually near organs for special ...

. Limitations in the applicability of this theory in thprimary visual cortex (V1)

motivated the

V1 Saliency Hypothesis

The V1 Saliency Hypothesis, or V1SH (pronounced‘vish’) is a theory about V1, the primary visual cortex (V1). It proposes that the V1 in primates creates a saliency map of the visual field to guide visual attention or gaze shifts exogenously.

...

that V1 creates a bottom-up saliency map to guide attention exogenously. With attentional selection as a center stage, vision is seen as composed of encoding, selection, and decoding stages.

The default mode network is a network of brain regions that are active when an individual is awake and at rest. The visual system's default mode can be monitored during resting state fMRI:

Fox, et al. (2005) have found thatThe human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks'"

in which the visual system switches from resting state to attention. In the

parietal lobe

The parietal lobe is one of the four major lobes of the cerebral cortex in the brain of mammals. The parietal lobe is positioned above the temporal lobe and behind the frontal lobe and central sulcus.

The parietal lobe integrates sensory informa ...

, the lateral

Lateral is a geometric term of location which may refer to:

Healthcare

*Lateral (anatomy), an anatomical direction

* Lateral cricoarytenoid muscle

* Lateral release (surgery), a surgical procedure on the side of a kneecap

Phonetics

*Lateral co ...

and ventral intraparietal cortex are involved in visual attention and saccadic eye movements. These regions are in the Intraparietal sulcus (marked in red in the adjacent image).

Development

Infancy

Newborn infants have limited color perception. One study found that 74% of newborns can distinguish red, 36% green, 25% yellow, and 14% blue. After one month, performance "improved somewhat." Infant’s eyes don’t have the ability to accommodate. The pediatricians are able to perform non-verbal testing to assessvisual acuity

Visual acuity (VA) commonly refers to the clarity of vision, but technically rates an examinee's ability to recognize small details with precision. Visual acuity is dependent on optical and neural factors, i.e. (1) the sharpness of the retinal ...

of a newborn, detect nearsightedness and astigmatism

Astigmatism is a type of refractive error due to rotational asymmetry in the eye's refractive power. This results in distorted or blurred vision at any distance. Other symptoms can include eyestrain, headaches, and trouble driving at ni ...

, and evaluate the eye teaming and alignment. Visual acuity improves from about 20/400 at birth to approximately 20/25 at 6 months of age. All this is happening because the nerve cells in their retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

and brain that control vision are not fully developed.

Childhood and adolescence

Depth perception

Depth perception is the ability to perceive distance to objects in the world using the visual system and visual perception. It is a major factor in perceiving the world in three dimensions. Depth perception happens primarily due to stereopsi ...

, focus, tracking and other aspects of vision continue to develop throughout early and middle childhood. From recent studies in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

and Australia there is some evidence that the amount of time school aged children spend outdoors, in natural light, may have some impact on whether they develop myopia

Near-sightedness, also known as myopia and short-sightedness, is an eye disease where light focuses in front of, instead of on, the retina. As a result, distant objects appear blurry while close objects appear normal. Other symptoms may include ...

. The condition tends to get somewhat worse through childhood and adolescence, but stabilizes in adulthood. More prominent myopia (nearsightedness) and astigmatism are thought to be inherited. Children with this condition may need to wear glasses.

Adulthood

Eyesight is often one of the first senses affected by aging. A number of changes occur with aging: * Over time, thelens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements'' ...

become yellowed and may eventually become brown, a condition known as brunescence or brunescent cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of the eye that leads to a decrease in vision. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colors, blurry or double vision, halos around light, trouble w ...

. Although many factors contribute to yellowing, lifetime exposure to ultraviolet light

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiati ...

and aging

Ageing ( BE) or aging ( AE) is the process of becoming older. The term refers mainly to humans, many other animals, and fungi, whereas for example, bacteria, perennial plants and some simple animals are potentially biologically immortal. In ...

are two main causes.

* The lens becomes less flexible, diminishing the ability to accommodate (presbyopia

Presbyopia is physiological insufficiency of accommodation associated with the aging of the eye that results in progressively worsening ability to focus clearly on close objects. Also known as age-related farsightedness (or age-related long sig ...

).

* While a healthy adult pupil typically has a size range of 2–8 mm, with age the range gets smaller, trending towards a moderately small diameter.

* On average tear production declines with age. However, there are a number of age-related conditions that can cause excessive tearing.

Other functions

Balance

Along withproprioception

Proprioception ( ), also referred to as kinaesthesia (or kinesthesia), is the sense of self-movement, force, and body position. It is sometimes described as the "sixth sense".

Proprioception is mediated by proprioceptors, mechanosensory neurons ...

and vestibular function, the visual system plays an important role in the ability of an individual to control balance and maintain an upright posture. When these three conditions are isolated and balance is tested, it has been found that vision is the most significant contributor to balance, playing a bigger role than either of the two other intrinsic mechanisms. The clarity with which an individual can see his environment, as well as the size of the visual field, the susceptibility of the individual to light and glare, and poor depth perception play important roles in providing a feedback loop to the brain on the body's movement through the environment. Anything that affects any of these variables can have a negative effect on balance and maintaining posture. This effect has been seen in research involving elderly subjects when compared to young controls, in glaucoma

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases that result in damage to the optic nerve (or retina) and cause vision loss. The most common type is open-angle (wide angle, chronic simple) glaucoma, in which the drainage angle for fluid within the eye re ...

patients compared to age matched controls, cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of the eye that leads to a decrease in vision. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colors, blurry or double vision, halos around light, trouble w ...

patients pre and post surgery, and even something as simple as wearing safety goggles. Monocular vision In human species

Monocular vision vision is known as seeing and using only one eye in the human species. Depth perception in monocular vision is reduced compared to binocular vision, but still is active primarily due to accommodation of the eye ...

(one eyed vision) has also been shown to negatively impact balance, which was seen in the previously referenced cataract and glaucoma studies, as well as in healthy children and adults.

According to Pollock et al. (2010) stroke is the main cause of specific visual impairment, most frequently visual field loss ( homonymous hemianopia, a visual field defect). Nevertheless, evidence for the efficacy of cost-effective interventions aimed at these visual field defects is still inconsistent.

Clinical significance

Proper function of the visual system is required for sensing, processing, and understanding the surrounding environment. Difficulty in sensing, processing and understanding light input has the potential to adversely impact an individual's ability to communicate, learn and effectively complete routine tasks on a daily basis.

In children, early diagnosis and treatment of impaired visual system function is an important factor in ensuring that key social, academic and speech/language developmental milestones are met.

Proper function of the visual system is required for sensing, processing, and understanding the surrounding environment. Difficulty in sensing, processing and understanding light input has the potential to adversely impact an individual's ability to communicate, learn and effectively complete routine tasks on a daily basis.

In children, early diagnosis and treatment of impaired visual system function is an important factor in ensuring that key social, academic and speech/language developmental milestones are met.

Cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of the eye that leads to a decrease in vision. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colors, blurry or double vision, halos around light, trouble w ...

is clouding of the lens, which in turn affects vision. Although it may be accompanied by yellowing, clouding and yellowing can occur separately. This is typically a result of ageing, disease, or drug use.

Presbyopia

Presbyopia is physiological insufficiency of accommodation associated with the aging of the eye that results in progressively worsening ability to focus clearly on close objects. Also known as age-related farsightedness (or age-related long sig ...

is a visual condition that causes farsightedness. The eye's lens becomes too inflexible to accommodate to normal reading distance, focus tending to remain fixed at long distance.

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases that result in damage to the optic nerve (or retina) and cause vision loss. The most common type is open-angle (wide angle, chronic simple) glaucoma, in which the drainage angle for fluid within the eye re ...

is a type of blindness that begins at the edge of the visual field and progresses inward. It may result in tunnel vision

Tunnel vision is the loss of peripheral vision with retention of central vision, resulting in a constricted circular tunnel-like field of vision.

Causes

Tunnel vision can be caused by:

Eyeglass users

Eyeglass users experience tunnel visio ...

. This typically involves the outer layers of the optic nerve, sometimes as a result of buildup of fluid and excessive pressure in the eye.

Scotoma

A scotoma is an area of partial alteration in the field of vision consisting of a partially diminished or entirely degenerated visual acuity that is surrounded by a field of normal – or relatively well-preserved – vision.

Every normal ma ...

is a type of blindness that produces a small blind spot in the visual field typically caused by injury in the primary visual cortex.

Homonymous hemianopia is a type of blindness that destroys one entire side of the visual field typically caused by injury in the primary visual cortex.

Quadrantanopia

Quadrantanopia, quadrantanopsia, refers to an anopia (loss of vision) affecting a quarter of the visual field.

It can be associated with a lesion of an optic radiation. While quadrantanopia can be caused by lesions in the temporal and pariet ...

is a type of blindness that destroys only a part of the visual field typically caused by partial injury in the primary visual cortex. This is very similar to homonymous hemianopia, but to a lesser degree.

Prosopagnosia, or face blindness, is a brain disorder that produces an inability to recognize faces. This disorder often arises after damage to the fusiform face area.

Visual agnosia, or visual-form agnosia, is a brain disorder that produces an inability to recognize objects. This disorder often arises after damage to the ventral stream

The two-streams hypothesis is a model of the neural processing of vision as well as hearing. The hypothesis, given its initial characterisation in a paper by David Milner and Melvyn A. Goodale in 1992, argues that humans possess two distinct visua ...

.

Other animals

Differentspecies

In biology, a species is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of ...

are able to see different parts of the light spectrum

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of frequencies (the spectrum) of electromagnetic radiation and their respective wavelengths and photon energies.

The electromagnetic spectrum covers electromagnetic waves with frequencies ranging from ...

; for example, bee

Bees are winged insects closely related to wasps and ants, known for their roles in pollination and, in the case of the best-known bee species, the western honey bee, for producing honey. Bees are a monophyly, monophyletic lineage within the ...

s can see into the ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiati ...

, while pit vipers can accurately target prey with their pit organs, which are sensitive to infrared radiation. The mantis shrimp possesses arguably the most complex visual system of any species. The eye of the mantis shrimp holds 16 color receptive cones, whereas humans only have three. The variety of cones enables them to perceive an enhanced array of colors as a mechanism for mate selection, avoidance of predators, and detection of prey. Swordfish also possess an impressive visual system. The eye of a swordfish

Swordfish (''Xiphias gladius''), also known as broadbills in some countries, are large, highly migratory predatory fish characterized by a long, flat, pointed bill. They are a popular sport fish of the billfish category, though elusive. Swordfi ...

can generate heat

In thermodynamics, heat is defined as the form of energy crossing the boundary of a thermodynamic system by virtue of a temperature difference across the boundary. A thermodynamic system does not ''contain'' heat. Nevertheless, the term is ...

to better cope with detecting their prey

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill the ...

at depths of 2000 feet. Certain one-celled microorganisms

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

, the warnowiid dinoflagellate

The dinoflagellates (Greek δῖνος ''dinos'' "whirling" and Latin ''flagellum'' "whip, scourge") are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered algae. Dinoflagellates are ...

s have eye-like ocelloids, with analogous structures for the lens and retina of the multi-cellular eye. The armored shell of the chiton

Chitons () are marine molluscs of varying size in the class Polyplacophora (), formerly known as Amphineura. About 940 extant and 430 fossil species are recognized.

They are also sometimes known as gumboots or sea cradles or coat-of-mail sh ...

'' Acanthopleura granulata'' is also covered with hundreds of aragonite

Aragonite is a carbonate mineral, one of the three most common naturally occurring crystal forms of calcium carbonate, (the other forms being the minerals calcite and vaterite). It is formed by biological and physical processes, including pre ...

crystalline eyes, named ocelli

A simple eye (sometimes called a pigment pit) refers to a form of eye or an optical arrangement composed of a single lens and without an elaborate retina such as occurs in most vertebrates. In this sense "simple eye" is distinct from a multi-le ...

, which can form image

An image is a visual representation of something. It can be two-dimensional, three-dimensional, or somehow otherwise feed into the visual system to convey information. An image can be an artifact, such as a photograph or other two-dimensio ...

s.

Many fan worms, such as '' Acromegalomma interruptum'' which live in tubes on the sea floor of the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

, have evolved compound eyes on their tentacles, which they use to detect encroaching movement. If movement is detected, the fan worms will rapidly withdraw their tentacles. Bok, et al., have discovered opsins and G protein

G proteins, also known as guanine nucleotide-binding proteins, are a family of proteins that act as molecular switches inside cells, and are involved in transmitting signals from a variety of stimuli outside a cell to its interior. Their ...

s in the fan worm's eyes, which were previously only seen in simple ciliary photoreceptors in the brains of some invertebrates

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

, as opposed to the rhabdomeric receptors in the eyes of most invertebrates. cited bEvolution of fan worm eyes (August 1, 2017) Phys.org

/ref> Only higher primate

Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by th ...

(African) monkeys

Monkey is a common name that may refer to most mammals of the infraorder Simiiformes, also known as the simians. Traditionally, all animals in the group now known as simians are counted as monkeys except the apes, which constitutes an incomple ...

and apes (macaque

The macaques () constitute a genus (''Macaca'') of gregarious Old World monkeys of the subfamily Cercopithecinae. The 23 species of macaques inhabit ranges throughout Asia, North Africa, and (in one instance) Gibraltar. Macaques are principal ...

s, apes, orangutan

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the gen ...

s) have the same kind of three-cone photoreceptor color vision humans have, while lower primate New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

(South American) monkeys (spider monkey

Spider monkeys are New World monkeys belonging to the genus ''Ateles'', part of the subfamily Atelinae, family Atelidae. Like other atelines, they are found in tropical forests of Central and South America, from southern Mexico to Brazil. The ...

s, squirrel monkeys, cebus monkeys) have a two-cone photoreceptor kind of color vision.

History

In the second half of the 19th century, many motifs of the nervous system were identified such as the neuron doctrine and brain localization, which related to theneuron

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, electrically excitable cell (biology), cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous ...

being the basic unit of the nervous system and functional localisation in the brain, respectively. These would become tenets of the fledgling neuroscience

Neuroscience is the science, scientific study of the nervous system (the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nervous system), its functions and disorders. It is a Multidisciplinary approach, multidisciplinary science that combines physiology, an ...

and would support further understanding of the visual system.

The notion that the cerebral cortex

The cerebral cortex, also known as the cerebral mantle, is the outer layer of neural tissue of the cerebrum of the brain in humans and other mammals. The cerebral cortex mostly consists of the six-layered neocortex, with just 10% consisting o ...

is divided into functionally distinct cortices now known to be responsible for capacities such as touch

In physiology, the somatosensory system is the network of neural structures in the brain and body that produce the perception of touch ( haptic perception), as well as temperature ( thermoception), body position ( proprioception), and pain. It ...

(somatosensory cortex

In physiology, the somatosensory system is the network of neural structures in the brain and body that produce the perception of touch ( haptic perception), as well as temperature ( thermoception), body position ( proprioception), and pain. It ...

), movement (motor cortex

The motor cortex is the region of the cerebral cortex believed to be involved in the planning, control, and execution of voluntary movements.

The motor cortex is an area of the frontal lobe located in the posterior precentral gyrus immediately ...

), and vision (visual cortex

The visual cortex of the brain is the area of the cerebral cortex that processes visual information. It is located in the occipital lobe. Sensory input originating from the eyes travels through the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus and ...

), was first proposed by Franz Joseph Gall

Franz Josef Gall (; 9 March 175822 August 1828) was a German neuroanatomist, physiologist, and pioneer in the study of the localization of mental functions in the brain.

Claimed as the founder of the pseudoscience of phrenology, Gall was an ea ...

in 1810. Evidence for functionally distinct areas of the brain (and, specifically, of the cerebral cortex) mounted throughout the 19th century with discoveries by Paul Broca

Pierre Paul Broca (, also , , ; 28 June 1824 – 9 July 1880) was a French physician, anatomist and anthropologist. He is best known for his research on Broca's area, a region of the frontal lobe that is named after him. Broca's area is involv ...

of the language center