Venom (Marvel Comics Characters) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Venom or zootoxin is a type of

Venom or zootoxin is a type of

Venoms cause their biological effects via the many

Venoms cause their biological effects via the many

There are venomous invertebrates in several phyla, including

There are venomous invertebrates in several phyla, including

Among marine animals, eels are resistant to sea snake venoms, which contain complex mixtures of neurotoxins, myotoxins, and nephrotoxins, varying according to species. Eels are especially resistant to the venom of sea snakes that specialise in feeding on them, implying coevolution; non-prey fishes have little resistance to sea snake venom.

Clownfish always live among the tentacles of venomous

Among marine animals, eels are resistant to sea snake venoms, which contain complex mixtures of neurotoxins, myotoxins, and nephrotoxins, varying according to species. Eels are especially resistant to the venom of sea snakes that specialise in feeding on them, implying coevolution; non-prey fishes have little resistance to sea snake venom.

Clownfish always live among the tentacles of venomous

Venom or zootoxin is a type of

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring organic poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. Toxins occur especially as a protein or conjugated protein. The term toxin was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849– ...

produced by an animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring organic poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. Toxins occur especially as a protein or conjugated protein. The term toxin was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849– ...

is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs

A fang is a long, pointed tooth. In mammals, a fang is a modified maxillary tooth, used for biting and tearing flesh. In snakes, it is a specialized tooth that is associated with a venom gland (see snake venom). Spiders also have external fangs ...

or a stinger

A stinger (or sting) is a sharp organ found in various animals (typically insects and other arthropods) capable of injecting venom, usually by piercing the epidermis of another animal.

An insect sting is complicated by its introduction of v ...

, in a process called envenomation

Envenomation is the process by which venom is injected by the bite or sting of a venomous animal.

Many kinds of animals, including mammals (e.g., the northern short-tailed shrew, ''Blarina brevicauda''), reptiles (e.g., the king cobra), spider ...

. Venom is often distinguished from poison

Poison is a chemical substance that has a detrimental effect to life. The term is used in a wide range of scientific fields and industries, where it is often specifically defined. It may also be applied colloquially or figuratively, with a broa ...

, which is a toxin that is passively delivered by being ingested, inhaled, or absorbed through the skin, and toxungen

Toxungen comprises a secretion of one or more Toxin, biological toxins that is transferred by one animal to the external surface of another animal via a physical delivery mechanism. Toxungens can be delivered through spitting, spraying, or smearing ...

, which is actively transferred to the external surface of another animal via a physical delivery mechanism.

Venom has evolved in terrestrial and marine environments and in a wide variety of animals: both predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill th ...

s and prey, and both vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

s and invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

s. Venoms kill through the action of at least four major classes of toxin, namely necrotoxins and cytotoxin

Cytotoxicity is the quality of being toxic to cells. Examples of toxic agents are an immune cell or some types of venom, e.g. from the puff adder (''Bitis arietans'') or brown recluse spider (''Loxosceles reclusa'').

Cell physiology

Treating c ...

s, which kill cells; neurotoxin

Neurotoxins are toxins that are destructive to nerve tissue (causing neurotoxicity). Neurotoxins are an extensive class of exogenous chemical neurological insultsSpencer 2000 that can adversely affect function in both developing and mature ner ...

s, which affect nervous systems; myotoxin

Myotoxins are small, basic peptides found in snake venoms (e.g. rattlesnakes) and lizard venoms (e.g. Mexican beaded lizard). This involves a non-enzymatic mechanism that leads to severe muscle necrosis. These peptides act very quickly, causing i ...

s, which damage muscles; and haemotoxins

Hemotoxins, haemotoxins or hematotoxins are toxins that destroy red blood cells, disrupt blood clotting, and/or cause organ degeneration and generalized tissue damage. The term ''hemotoxin'' is to some degree a misnomer since toxins that damage ...

, which disrupt blood clotting

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanism o ...

. Venomous animals cause tens of thousands of human deaths per year.

Venoms are often complex mixtures of toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring organic poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. Toxins occur especially as a protein or conjugated protein. The term toxin was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849– ...

s of differing types. Toxins from venom are used to treat a wide range of medical conditions including thrombosis

Thrombosis (from Ancient Greek "clotting") is the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel (a vein or an artery) is injured, the body uses platelets (thro ...

, arthritis

Arthritis is a term often used to mean any disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, swelling, and decreased range of motion of the affected joints. In som ...

, and some cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

s. Studies in venomics

Venomics is the large-scale study of proteins associated with venom. Venom is a toxic substance secreted by animals, which is typically injected either offensively or defensively into prey or aggressors, respectively.

Venom is produced in a specia ...

are investigating the potential use of venom toxins for many other conditions.

Evolution

The use of venom across a wide variety oftaxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

is an example of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

. It is difficult to conclude exactly how this trait came to be so intensely widespread and diversified. The multigene families that encode the toxins of venomous animals are actively selected, creating more diverse toxins with specific functions. Venoms adapt to their environment and victims and accordingly evolve to become maximally efficient on a predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill th ...

's particular prey (particularly the precise ion channel

Ion channels are pore-forming membrane proteins that allow ions to pass through the channel pore. Their functions include establishing a resting membrane potential, shaping action potentials and other electrical signals by gating the flow of io ...

s within the prey). Consequently, venoms become specialized to an animal's standard diet.

Mechanisms

Venoms cause their biological effects via the many

Venoms cause their biological effects via the many toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring organic poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. Toxins occur especially as a protein or conjugated protein. The term toxin was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849– ...

s that they contain; some venoms are complex mixtures of toxins of differing types. Major classes of toxin in venoms include:

* Necrotoxins, which cause necrosis (i.e., death) in the cells they encounter. The venoms of vipers and bees contain phospholipase

A phospholipase is an enzyme that hydrolyzes phospholipids into fatty acids and other lipophilic substances. Acids trigger the release of bound calcium from cellular stores and the consequent increase in free cytosolic Ca2+, an essential step in ...

s; viper venoms often also contain trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting these long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the dig ...

-like serine proteases

Serine proteases (or serine endopeptidases) are enzymes that cleave peptide bonds in proteins. Serine serves as the nucleophilic amino acid at the (enzyme's) active site.

They are found ubiquitously in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Serin ...

.

* Neurotoxin

Neurotoxins are toxins that are destructive to nerve tissue (causing neurotoxicity). Neurotoxins are an extensive class of exogenous chemical neurological insultsSpencer 2000 that can adversely affect function in both developing and mature ner ...

s, which primarily affect the nervous systems of animals, such as ion channel toxins

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

. These are found in many venomous taxa, including black widow spiders, scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the order Scorpiones. They have eight legs, and are easily recognized by a pair of grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward curve over the back and always end ...

s, box jellyfish

Box jellyfish (class Cubozoa) are cnidarian invertebrates distinguished by their box-like (i.e. cube-shaped) body. Some species of box jellyfish produce potent venom delivered by contact with their tentacles. Stings from some species, including '' ...

, cone snail

A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base (frequently, though not necessarily, circular) to a point called the apex or vertex.

A cone is formed by a set of line segments, half-lines, or lines con ...

s, centipede

Centipedes (from New Latin , "hundred", and Latin , " foot") are predatory arthropods belonging to the class Chilopoda (Ancient Greek , ''kheilos'', lip, and New Latin suffix , "foot", describing the forcipules) of the subphylum Myriapoda, an ...

s and blue-ringed octopus

Blue-ringed octopuses, comprising the genus ''Hapalochlaena'', are four highly venomous species of octopus that are found in tide pools and coral reefs in the Pacific and Indian oceans, from Japan to Australia. They can be identified by their ye ...

es.

* Myotoxin

Myotoxins are small, basic peptides found in snake venoms (e.g. rattlesnakes) and lizard venoms (e.g. Mexican beaded lizard). This involves a non-enzymatic mechanism that leads to severe muscle necrosis. These peptides act very quickly, causing i ...

s, which damage muscles by binding to a receptor. These small, basic peptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

A ...

s are found in snake

Snakes are elongated, Limbless vertebrate, limbless, carnivore, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other Squamata, squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping Scale (zoology), scales. Ma ...

(such as rattlesnake

Rattlesnakes are venomous snakes that form the genera ''Crotalus'' and ''Sistrurus'' of the subfamily Crotalinae (the pit vipers). All rattlesnakes are vipers. Rattlesnakes are predators that live in a wide array of habitats, hunting small anim ...

) and lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia alt ...

venoms.

* Cytotoxins

Cytotoxicity is the quality of being toxic to cells. Examples of toxic agents are an immune cell or some types of venom, e.g. from the puff adder (''Bitis arietans'') or brown recluse spider (''Loxosceles reclusa'').

Cell physiology

Treating cell ...

, which kill individual cells and are found in the apitoxin of honey bees and the venom of black widow spiders.

Taxonomic range

Venom is widely distributed taxonomically, being found in both invertebrates and vertebrates, in aquatic and terrestrial animals, and among both predators and prey. The major groups of venomous animals are described below.Arthropods

Venomous arthropods includespider

Spiders ( order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight legs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and rank seventh in total species ...

s, which use fangs on their chelicerae

The chelicerae () are the mouthparts of the subphylum Chelicerata, an arthropod group that includes arachnids, horseshoe crabs, and sea spiders. Commonly referred to as "jaws", chelicerae may be shaped as either articulated fangs, or similarly ...

to inject venom; and centipede

Centipedes (from New Latin , "hundred", and Latin , " foot") are predatory arthropods belonging to the class Chilopoda (Ancient Greek , ''kheilos'', lip, and New Latin suffix , "foot", describing the forcipules) of the subphylum Myriapoda, an ...

s, which use forcipules

Forcipules are the modified, pincer-like, front legs of centipedes that are used to inject venom into prey. They are the only known examples of front legs acting as venom injectors.

Nomenclature

Forcipules go by a variety of names in both scien ...

, modified legs, to deliver venom; while scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the order Scorpiones. They have eight legs, and are easily recognized by a pair of grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward curve over the back and always end ...

s and stinging insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body ( head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

s inject venom with a sting. In bees and wasp

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder. Th ...

s, the sting is a modified egg-laying device – the ovipositor

The ovipositor is a tube-like organ used by some animals, especially insects, for the laying of eggs. In insects, an ovipositor consists of a maximum of three pairs of appendages. The details and morphology of the ovipositor vary, but typical ...

. In ''Polistes fuscatus

''Polistes fuscatus'', whose common name is the dark or northern paper wasp, is widely found in eastern North America, from southern Canada through the southern United States. It often nests around human development. However, it greatly prefers a ...

'', the female continuously releases a venom that contains a sex pheromone that induces copulatory behavior in males. In wasps such as ''Polistes exclamans

''Polistes exclamans'', the Guinea paper wasp, is a social wasp and is part of the family Vespidae of the order Hymenoptera. It is found throughout the United States, Mexico, the Bahamas, Jamaica and parts of Canada. Due to solitary nest foundin ...

'', venom is used as an alarm pheromone, coordinating a response with from the nest and attracting nearby wasps to attack the predator. In some species, such as '' Parischnogaster striatula'', venom is applied all over the body as an antimicrobial protection.

Many caterpillar

Caterpillars ( ) are the larval stage of members of the order Lepidoptera (the insect order comprising butterflies and moths).

As with most common names, the application of the word is arbitrary, since the larvae of sawflies (suborder Sym ...

s have defensive venom glands associated with specialized bristles on the body called urticating hairs

Urticating hairs or urticating bristles are one of the primary defense mechanisms used by numerous plants, almost all New World tarantulas, and various lepidopteran caterpillars. ''Urtica'' is Latin for "nettle" (stinging nettles are in the genus ...

. These are usually merely irritating, but those of the ''Lonomia

The genus ''Lonomia'' is a moderate-sized group of fairly cryptic saturniid moths from South America, famous not for the adults, but for their highly venomous caterpillars, which are responsible for a few deaths each year, especially in southern ...

'' moth can be fatal to humans.

Bees synthesize and employ an acidic venom ( apitoxin) to defend their hives and food stores, whereas wasps use a chemically different venom to paralyse prey, so their prey remains alive to provision the food chambers of their young. The use of venom is much more widespread than just these examples; many other insects, such as true bug

Hemiptera (; ) is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising over 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from to around ...

s and many ant

Ants are eusocial insects of the family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cretaceous period. More than 13,800 of an estimated total of 22 ...

s, also produce venom. The ant species ''Polyrhachis dives

''Polyrhachis dives'' is a wide-ranging species of ant from southern Asia and Australia, even though they are restricted to the northern territory.

Identification

Throughout its wide distribution, ''P. dives'' is a morphologically stable spec ...

'' uses venom topically

A topical medication is a medication that is applied to a particular place on or in the body. Most often topical medication means application to body surfaces such as the skin or mucous membranes to treat ailments via a large range of classes ...

for the sterilisation of pathogens.

Other invertebrates

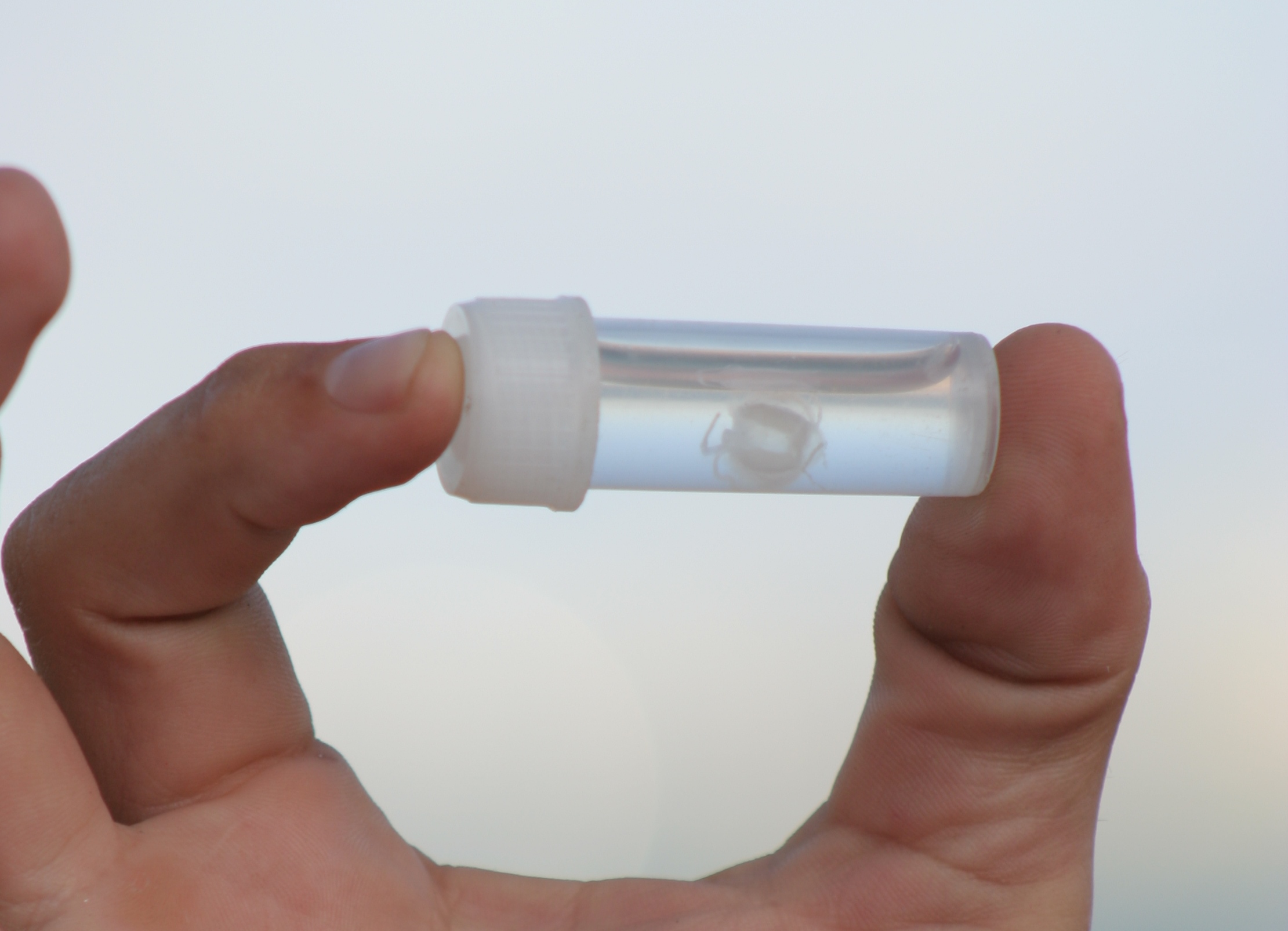

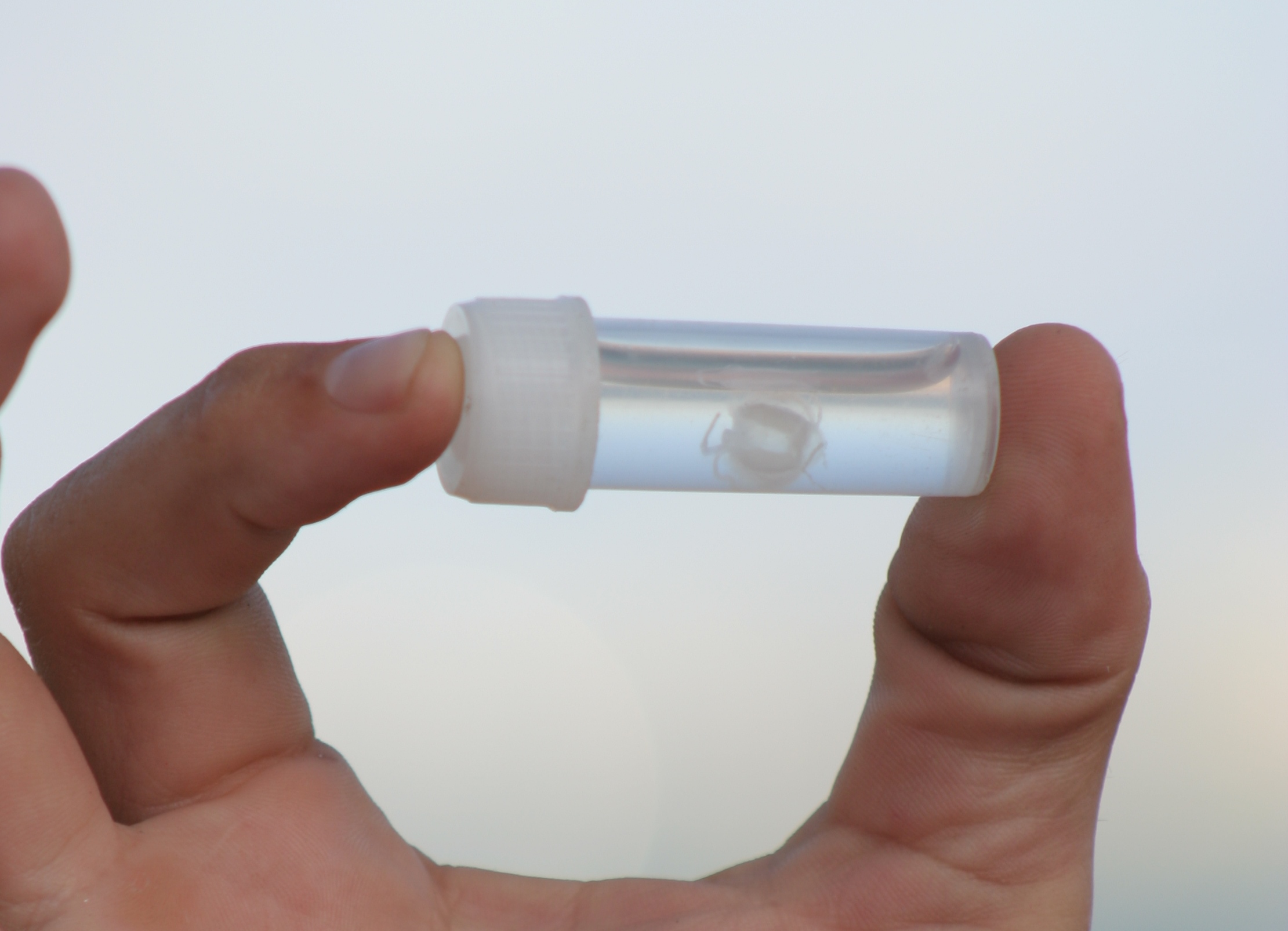

There are venomous invertebrates in several phyla, including

There are venomous invertebrates in several phyla, including jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbrella- ...

such as the dangerous box jellyfish

Box jellyfish (class Cubozoa) are cnidarian invertebrates distinguished by their box-like (i.e. cube-shaped) body. Some species of box jellyfish produce potent venom delivered by contact with their tentacles. Stings from some species, including '' ...

and sea anemone

Sea anemones are a group of predation, predatory marine invertebrates of the order (biology), order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the ''Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemones are classifi ...

s among the Cnidaria

Cnidaria () is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments, predominantly the latter.

Their distinguishing feature is cnidocytes, specialized cells that th ...

, sea urchin

Sea urchins () are spiny, globular echinoderms in the class Echinoidea. About 950 species of sea urchin live on the seabed of every ocean and inhabit every depth zone from the intertidal seashore down to . The spherical, hard shells (tests) of ...

s among the Echinodermata

An echinoderm () is any member of the phylum Echinodermata (). The adults are recognisable by their (usually five-point) radial symmetry, and include starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers, as well as the sea li ...

,and cone snails

A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base (frequently, though not necessarily, circular) to a point called the apex or vertex.

A cone is formed by a set of line segments, half-lines, or lines co ...

and cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda (Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head ...

s, including octopus

An octopus ( : octopuses or octopodes, see below for variants) is a soft-bodied, eight- limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttle ...

es, among the Mollusc

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is esti ...

s.

Vertebrates

Fish

Venom is found in some 200 cartilaginous fishes, includingstingrays

Stingrays are a group of sea rays, which are cartilaginous fish related to sharks. They are classified in the suborder Myliobatoidei of the order Myliobatiformes and consist of eight families: Hexatrygonidae (sixgill stingray), Plesiobatidae ...

, shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachimo ...

s, and chimaera

Chimaeras are cartilaginous fish in the order Chimaeriformes , known informally as ghost sharks, rat fish, spookfish, or rabbit fish; the last three names are not to be confused with rattails, Opisthoproctidae, or Siganidae, respectively.

At ...

s; the catfishes

Catfish (or catfishes; order Siluriformes or Nematognathi) are a diverse group of ray-finned fish. Named for their prominent barbels, which resemble a cat's whiskers, catfish range in size and behavior from the three largest species alive, ...

(about 1000 venomous species); and 11 clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

s of spiny-rayed fishes (Acanthomorpha

Acanthomorpha (meaning "thorn-shaped") is an extraordinarily diverse taxon of teleost fishes with spiny rays. The clade contains about one third of the world's modern species of vertebrates: over 14,000 species.

A key anatomical innovation in ...

), containing the scorpionfishes (over 300 species), stonefish

''Synanceia'' is a genus of ray-finned fish belonging to the subfamily Synanceiinae, the stonefishes, which is classified within the family Scorpaenidae, the scorpionfishes and relatives. Stonefishes are venomous, dangerous, and fatal to huma ...

es (over 80 species), gurnard perches, blennies

Blenny (from the Greek and , mucus, slime) is a common name for many types of fish, including several families of percomorph marine, brackish, and some freshwater fish sharing similar morphology and behaviour. Six families are considered "true ...

, rabbitfishes

Rabbitfishes or spinefoots are perciform fishes in the family Siganidae. The 29 species are in a single genus, ''Siganus''. In some now obsolete classifications, the species having prominent face stripes—colloquially called foxfaces– ...

, surgeonfish

Acanthuridae are the family of surgeonfishes, tangs, and unicornfishes. The family includes about 86 extant species of marine fish living in tropical seas, usually around coral reefs. Many of the species are brightly colored and popular in ...

es, some velvetfishes, some toadfish

Toadfish is the common name for a variety of species from several different families of fish, usually because of their toad-like appearance. "Dogfish" is a name for certain species along the gulf coast.

Dolphin-Toadfish relationship

Toadfish mak ...

es, coral croucher

''Caracanthus'', the coral crouchers, or orbicular velvetfishes, are a genus of ray-finned fishes. They live in coral reefs of the tropical Indo-Pacific. This genus is the only member of the Monotypic taxon, monotypic subfamily Caracanthinae, pa ...

s, red velvetfishes, scats

The Sydney Coordinated Adaptive Traffic System, abbreviated SCATS, is an intelligent transportation system that manages the dynamic (on-line, real-time) timing of signal phases at traffic signals, meaning that it tries to find the best phasing (i ...

, rockfishes, deepwater scorpionfishes, waspfish

Tetraroginae is a subfamily of marine ray-finned fishes, commonly known as waspfishes or sailback scorpionfishes, belonging to the family Scorpaenidae, the scorpionfishes and their relatives. These fishes are native to the Indian Ocean and the W ...

es, weevers, and stargazers.

Amphibians

Somesalamanders

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All ten ...

can extrude sharp venom-tipped ribs. Two frog species in Brazil have tiny spines around the crown of their skulls which, on impact, deliver venom into their targets.

Reptiles

Some 450 species of snake are venomous.Snake venom

Snake venom is a highly toxic saliva containing zootoxins that facilitates in the immobilization and digestion of prey. This also provides defense against threats. Snake venom is injected by unique fangs during a bite, whereas some species are a ...

is produced by glands below the eye (the mandibular glands

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

) and delivered to the target through tubular or channeled fangs. Snake venoms contain a variety of peptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

A ...

toxins, including proteases

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the for ...

, which hydrolyze

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water is the nucleophile.

Biological hydrolysis ...

protein peptide bonds; nucleases

A nuclease (also archaically known as nucleodepolymerase or polynucleotidase) is an enzyme capable of cleaving the phosphodiester bonds between nucleotides of nucleic acids. Nucleases variously effect single and double stranded breaks in their ta ...

, which hydrolyze the phosphodiester

In chemistry, a phosphodiester bond occurs when exactly two of the hydroxyl groups () in phosphoric acid react with hydroxyl groups on other molecules to form two ester bonds. The "bond" involves this linkage . Discussion of phosphodiesters is d ...

bonds of DNA; and neurotoxins, which disrupt signalling in the nervous system. Snake venom causes symptoms including pain, swelling, tissue necrosis, low blood pressure, convulsions, haemorrhage (varying by species of snake), respiratory paralysis, kidney failure, coma, and death. Snake venom may have originated with duplication of genes that had been expressed in the salivary gland

The salivary glands in mammals are exocrine glands that produce saliva through a system of ducts. Humans have three paired major salivary glands (parotid, submandibular, and sublingual), as well as hundreds of minor salivary glands. Salivary gla ...

s of ancestors.

Venom is found in a few other reptiles such as the Mexican beaded lizard

The Mexican beaded lizard (''Heloderma horridum'') is a species of lizard in the family Helodermatidae, one of the two species of venomous beaded lizards found principally in Mexico and southern Guatemala. It and the other member of the same gen ...

, the gila monster

The Gila monster (''Heloderma suspectum'', ) is a species of venomous lizard native to the Southwestern United States and the northwestern Mexican state of Sonora. It is a heavy, typically slow-moving reptile, up to long, and it is the only v ...

, and some monitor lizards, including the Komodo dragon

The Komodo dragon (''Varanus komodoensis''), also known as the Komodo monitor, is a member of the monitor lizard family Varanidae that is endemic to the Indonesian islands of Komodo, Rinca, Flores, and Gili Motang. It is the largest extant ...

. Mass spectrometry showed that the mixture of proteins present in their venom is as complex as the mixture of proteins found in snake venom.

Some lizards possess a venom gland; they form a hypothetical clade, Toxicofera

Toxicofera (Greek for "those who bear toxins") is a proposed clade of scaled reptiles (squamates) that includes the Serpentes (snakes), Anguimorpha (monitor lizards, gila monster, and alligator lizards) and Iguania (iguanas, agamas, and chamel ...

, containing the suborders Serpentes

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more joints ...

and Iguania

Iguania is an infraorder of squamate reptiles that includes iguanas, chameleons, agamids, and New World lizards like anoles and phrynosomatids. Using morphological features as a guide to evolutionary relationships, the Iguania are believed t ...

and the families Varanidae

The Varanidae are a family of lizards in the superfamily Varanoidea within the Anguimorpha group. The family, a group of carnivorous and frugivorous lizards, includes the living genus '' Varanus'' and a number of extinct genera more closely relat ...

, Anguidae

Anguidae refers to a large and diverse family of lizards native to the Northern Hemisphere. Common characteristics of this group include a reduced supratemporal arch, striations on the medial faces of tooth crowns, osteoderms, and a lateral fold ...

, and Helodermatidae

The Helodermatidae or beaded lizards are a small family of lizards endemic to North America today, but formerly more widespread in the ancient past. Traditionally, the Gila monster and the Mexican beaded lizard were the only species recognized, ...

.

Mammals

''Euchambersia

''Euchambersia'' is an extinct genus of therocephalian therapsids that lived during the Late Permian in what is now South Africa and China. The genus contains two species. The type species ''E. mirabilis'' was named by paleontologist Robert Broo ...

'', an extinct genus of therocephalia

Therocephalia is an extinct suborder of eutheriodont therapsids (mammals and their close relatives) from the Permian and Triassic. The therocephalians ("beast-heads") are named after their large skulls, which, along with the structure of their te ...

ns, is hypothesized to have had venom glands attached to its canine teeth.

A few species of living mammals are venomous, including solenodon

Solenodons (from el, τέλειος , 'channel' or 'pipe' and el, ὀδούς , 'tooth') are venomous, nocturnal, burrowing, insectivorous mammals belonging to the family Solenodontidae . The two living solenodon species are the Cuban solen ...

s, shrews

Shrews (family Soricidae) are small mole-like mammals classified in the order Eulipotyphla. True shrews are not to be confused with treeshrews, otter shrews, elephant shrews, West Indies shrews, or marsupial shrews, which belong to different ...

, vampire bat

Vampire bats, species of the subfamily Desmodontinae, are leaf-nosed bats found in Central and South America. Their food source is blood of other animals, a dietary trait called hematophagy. Three extant bat species feed solely on blood: the com ...

s, male platypus

The platypus (''Ornithorhynchus anatinus''), sometimes referred to as the duck-billed platypus, is a semiaquatic, egg-laying mammal Endemic (ecology), endemic to Eastern states of Australia, eastern Australia, including Tasmania. The platypu ...

es, and slow loris

Slow lorises are a group of several species of nocturnal strepsirrhine primates that make up the genus ''Nycticebus''. Found in Southeast Asia and bordering areas, they range from Bangladesh and Northeast India in the west to the Sulu Archipe ...

es. Shrews have venomous saliva and most likely evolved their trait similarly to snakes. The presence of tarsal spurs akin to those of the platypus in many non-theria

Theria (; Greek: , wild beast) is a subclass of mammals amongst the Theriiformes. Theria includes the eutherians (including the placental mammals) and the metatherians (including the marsupials) but excludes the egg-laying monotremes.

Ch ...

n Mammaliaformes

Mammaliaformes ("mammalian forms") is a clade that contains the crown group mammals and their closest Extinction, extinct relatives; the group adaptive radiation, radiated from earlier probainognathian cynodonts. It is defined as the clade origin ...

groups suggests that venom was an ancestral characteristic among mammals.

Extensive research on platypuses shows that their toxin was initially formed from gene duplication, but data provides evidence that the further evolution of platypus venom does not rely as much on gene duplication as was once thought. Modified sweat glands are what evolved into platypus venom glands. Although it is proven that reptile and platypus venom have independently evolved, it is thought that there are certain protein structures that are favored to evolve into toxic molecules. This provides more evidence of why venom has become a homoplastic trait and why very different animals have convergently evolved.

Venom and humans

Envenomation

Envenomation is the process by which venom is injected by the bite or sting of a venomous animal.

Many kinds of animals, including mammals (e.g., the northern short-tailed shrew, ''Blarina brevicauda''), reptiles (e.g., the king cobra), spider ...

resulted in 57,000 human deaths in 2013, down from 76,000 deaths in 1990. Venoms, found in over 173,000 species, have potential to treat a wide range of diseases, explored in over 5,000 scientific papers.

In medicine, snake venom proteins are used to treat conditions including thrombosis

Thrombosis (from Ancient Greek "clotting") is the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel (a vein or an artery) is injured, the body uses platelets (thro ...

, arthritis

Arthritis is a term often used to mean any disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, swelling, and decreased range of motion of the affected joints. In som ...

, and some cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

s. Gila monster

The Gila monster (''Heloderma suspectum'', ) is a species of venomous lizard native to the Southwestern United States and the northwestern Mexican state of Sonora. It is a heavy, typically slow-moving reptile, up to long, and it is the only v ...

venom contains exenatide

Exenatide, sold under the brand name Byetta and Bydureon among others, is a medication used to treat diabetes mellitus type 2. It is used together with diet, exercise, and potentially other antidiabetic medication. It is a treatment option after ...

, used to treat type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes, formerly known as adult-onset diabetes, is a form of diabetes mellitus that is characterized by high blood sugar, insulin resistance, and relative lack of insulin. Common symptoms include increased thirst, frequent urination, ...

. Solenopsin

Solenopsin is a lipophilic alkaloid with the molecular formula C17H35N found in the venom of fire ants (''Solenopsis''). It is considered the primary toxin in the venom and may be the component responsible for the cardiorespiratory failure in peo ...

s extracted from fire ant

Fire ants are several species of ants in the genus ''Solenopsis'', which includes over 200 species. ''Solenopsis'' are stinging ants, and most of their common names reflect this, for example, ginger ants and tropical fire ants. Many of the nam ...

venom has demonstrated biomedical applications, ranging from cancer treatment to psoriasis

Psoriasis is a long-lasting, noncontagious autoimmune disease characterized by raised areas of abnormal skin. These areas are red, pink, or purple, dry, itchy, and scaly. Psoriasis varies in severity from small, localized patches to complete ...

. A branch of science, venomics

Venomics is the large-scale study of proteins associated with venom. Venom is a toxic substance secreted by animals, which is typically injected either offensively or defensively into prey or aggressors, respectively.

Venom is produced in a specia ...

, has been established to study the proteins associated with venom and how individual components of venom can be used for pharmaceutical means.

Resistance

Venom is used as a trophic weapon by many predator species. The coevolution between predators and prey is the driving force of venom resistance, which has evolved multiple times throughout the animal kingdom. The coevolution between venomous predators and venom-resistant prey has been described as a chemical arms race. Predator and prey pairs are expected to coevolve over long periods of time. As the predator capitalizes on susceptible individuals, the surviving individuals are limited to those able to evade predation. Resistance typically increases over time as the predator becomes increasingly unable to subdue resistant prey. The cost of developing venom resistance is high for both predator and prey. The payoff for the cost of physiological resistance is an increased chance of survival for prey, but it allows predators to expand into underutilised trophic niches. TheCalifornia ground squirrel

The California ground squirrel (''Otospermophilus beecheyi''), also known as the Beechey ground squirrel, is a common and easily observed ground squirrel of the western United States and the Baja California Peninsula; it is common in Oregon and ...

has varying degrees of resistance to the venom of the Northern Pacific rattlesnake. The resistance involves toxin scavenging and depends on the population. Where rattlesnake populations are denser, squirrel resistance is higher. Rattlesnakes have responded locally by increasing the effectiveness of their venom.

The kingsnake

Kingsnakes are colubrid New World members of the genus ''Lampropeltis'', which includes 26 species. Among these, about 45 subspecies are recognized. They are nonvenomous and ophiophagous in diet.

Description

Kingsnakes vary widely in size and ...

s of the Americas are constrictors that prey on many venomous snakes. They have evolved resistance which does not vary with age or exposure. They are immune to the venom of snakes in their immediate environment, like copperheads, cottonmouths, and North American rattlesnakes, but not to the venom of, for example, king cobras or black mambas.

Among marine animals, eels are resistant to sea snake venoms, which contain complex mixtures of neurotoxins, myotoxins, and nephrotoxins, varying according to species. Eels are especially resistant to the venom of sea snakes that specialise in feeding on them, implying coevolution; non-prey fishes have little resistance to sea snake venom.

Clownfish always live among the tentacles of venomous

Among marine animals, eels are resistant to sea snake venoms, which contain complex mixtures of neurotoxins, myotoxins, and nephrotoxins, varying according to species. Eels are especially resistant to the venom of sea snakes that specialise in feeding on them, implying coevolution; non-prey fishes have little resistance to sea snake venom.

Clownfish always live among the tentacles of venomous sea anemone

Sea anemones are a group of predation, predatory marine invertebrates of the order (biology), order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the ''Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemones are classifi ...

s (an obligatory symbiosis

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasit ...

for the fish), and are resistant to their venom. Only 10 known species of anemones are hosts to clownfish and only certain pairs of anemones and clownfish are compatible. All sea anemones produce venoms delivered through discharging nematocyst

A cnidocyte (also known as a cnidoblast or nematocyte) is an explosive cell containing one large secretory organelle called a cnidocyst (also known as a cnida () or nematocyst) that can deliver a sting to other organisms. The presence of this ce ...

s and mucous secretions. The toxins are composed of peptides and proteins. They are used to acquire prey and to deter predators by causing pain, loss of muscular coordination, and tissue damage. Clownfish have a protective mucus that acts as a chemical camouflage or macromolecular mimicry preventing "not self" recognition by the sea anemone and nematocyst discharge. Clownfish may acclimate their mucus to resemble that of a specific species of sea anemone.

See also

*Schmidt Sting Pain Index

The Schmidt sting pain index is a pain scale rating the relative pain caused by different hymenopteran stings. It is mainly the work of Justin O. Schmidt (born 1947), an entomologist at the Carl Hayden Bee Research Center in Arizona, United States ...

References

{{Authority control Animal physiology Toxins