V1 Flying Bomb on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The V-1 flying bomb (german: Vergeltungswaffe 1 "Vengeance Weapon 1") was an early

The V-1 was designed under the codename (cherry stone) by Lusser and Gosslau, with a

The V-1 was designed under the codename (cherry stone) by Lusser and Gosslau, with a

The Argus

The Argus

The V-1

The V-1

Ground-launched V-1s were propelled up an inclined launch ramp by an apparatus known as a ("steam generator"), in which steam was generated when

Ground-launched V-1s were propelled up an inclined launch ramp by an apparatus known as a ("steam generator"), in which steam was generated when  The Walter catapult accelerated the V-1 to a launch speed of , well above the needed minimum operational speed of . The V-1 made British landfall at , but accelerated to over London, as its of fuel burned off.

On 18 June 1943,

The Walter catapult accelerated the V-1 to a launch speed of , well above the needed minimum operational speed of . The V-1 made British landfall at , but accelerated to over London, as its of fuel burned off.

On 18 June 1943,

The first complete V-1 airframe was delivered on 30 August 1942, and after the first complete As.109-014 was delivered in September, the first glide test flight was on 28 October 1942 at

The first complete V-1 airframe was delivered on 30 August 1942, and after the first complete As.109-014 was delivered in September, the first glide test flight was on 28 October 1942 at  The conventional launch sites could theoretically launch about 15 V-1s per day, but this rate was difficult to achieve on a consistent basis; the maximum rate achieved was 18. Overall, only about 25% of the V-1s hit their targets, the majority being lost because of a combination of defensive measures, mechanical unreliability or guidance errors. With the capture or destruction of the launch facilities used to attack England, the V-1s were employed in attacks against strategic points in Belgium, primarily the port of Antwerp.

Launches against Britain were met by a variety of countermeasures, including

The conventional launch sites could theoretically launch about 15 V-1s per day, but this rate was difficult to achieve on a consistent basis; the maximum rate achieved was 18. Overall, only about 25% of the V-1s hit their targets, the majority being lost because of a combination of defensive measures, mechanical unreliability or guidance errors. With the capture or destruction of the launch facilities used to attack England, the V-1s were employed in attacks against strategic points in Belgium, primarily the port of Antwerp.

Launches against Britain were met by a variety of countermeasures, including  The trial versions of the V-1 were air-launched. Most operational V-1s were launched from static sites on land, but from July 1944 to January 1945, the launched approximately 1,176 from modified

The trial versions of the V-1 were air-launched. Most operational V-1s were launched from static sites on land, but from July 1944 to January 1945, the launched approximately 1,176 from modified

Late in the war, several air-launched piloted V-1s, known as , were built, but these were never used in combat.

Late in the war, several air-launched piloted V-1s, known as , were built, but these were never used in combat.

There were plans, not put into practice, to use the

There were plans, not put into practice, to use the

The British defence against German long-range weapons was known by the codename Crossbow with

The British defence against German long-range weapons was known by the codename Crossbow with

In daylight, V-1 chases were chaotic and often unsuccessful until a special defence zone was declared between London and the coast, in which only the fastest fighters were permitted. The first interception of a V-1 was by F/L J. G. Musgrave with a No. 605 Squadron RAF Mosquito night fighter on the night of 14/15 June 1944. As daylight grew stronger after the night attack, a Spitfire was seen to follow closely behind a V-1 over Chislehurst and Lewisham. Between June and 5 September 1944, a handful of 150 Wing Tempests shot down 638 flying bombs, with No. 3 Squadron RAF alone claiming 305. One Tempest pilot, Squadron Leader Joseph Berry ( 501 Squadron), shot down 59 V-1s, the Belgian ace Squadron Leader

In daylight, V-1 chases were chaotic and often unsuccessful until a special defence zone was declared between London and the coast, in which only the fastest fighters were permitted. The first interception of a V-1 was by F/L J. G. Musgrave with a No. 605 Squadron RAF Mosquito night fighter on the night of 14/15 June 1944. As daylight grew stronger after the night attack, a Spitfire was seen to follow closely behind a V-1 over Chislehurst and Lewisham. Between June and 5 September 1944, a handful of 150 Wing Tempests shot down 638 flying bombs, with No. 3 Squadron RAF alone claiming 305. One Tempest pilot, Squadron Leader Joseph Berry ( 501 Squadron), shot down 59 V-1s, the Belgian ace Squadron Leader

On 16 June 1944, British double agent ''Garbo'' ( Juan Pujol) was requested by his German controllers to give information on the sites and times of V-1 impacts, with similar requests made to the other German agents in Britain, ''Brutus'' ( Roman Czerniawski) and ''Tate'' (

On 16 June 1944, British double agent ''Garbo'' ( Juan Pujol) was requested by his German controllers to give information on the sites and times of V-1 impacts, with similar requests made to the other German agents in Britain, ''Brutus'' ( Roman Czerniawski) and ''Tate'' ( A certain number of the V-1s fired had been fitted with radio transmitters, which had clearly demonstrated a tendency for the V-1 to fall short. Max Wachtel, commander of Flak Regiment 155 (W), which was responsible for the V-1 offensive, compared the data gathered by the transmitters with the reports obtained through the double agents. He concluded, when faced with the discrepancy between the two sets of data, that there must be a fault with the radio transmitters, as he had been assured that the agents were completely reliable. It was later calculated that if Wachtel had disregarded the agents' reports and relied on the radio data, he would have made the correct adjustments to the V-1's guidance, and casualties might have increased by 50 percent or more.

The policy of diverting V-1 impacts away from central London was initially controversial. The War Cabinet refused to authorise a measure that would increase casualties in any area, even if it reduced casualties elsewhere by greater amounts. It was thought that

A certain number of the V-1s fired had been fitted with radio transmitters, which had clearly demonstrated a tendency for the V-1 to fall short. Max Wachtel, commander of Flak Regiment 155 (W), which was responsible for the V-1 offensive, compared the data gathered by the transmitters with the reports obtained through the double agents. He concluded, when faced with the discrepancy between the two sets of data, that there must be a fault with the radio transmitters, as he had been assured that the agents were completely reliable. It was later calculated that if Wachtel had disregarded the agents' reports and relied on the radio data, he would have made the correct adjustments to the V-1's guidance, and casualties might have increased by 50 percent or more.

The policy of diverting V-1 impacts away from central London was initially controversial. The War Cabinet refused to authorise a measure that would increase casualties in any area, even if it reduced casualties elsewhere by greater amounts. It was thought that

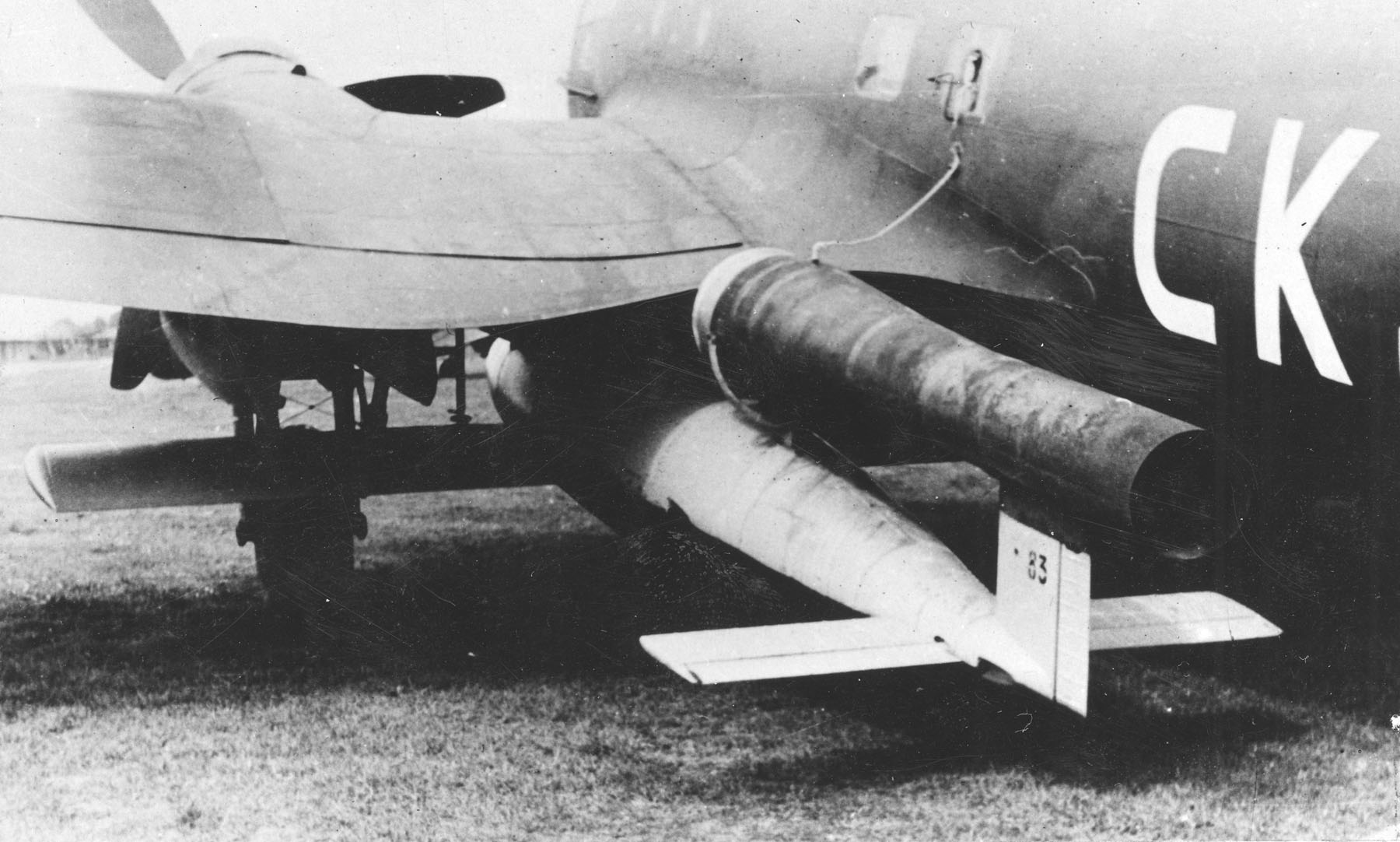

The statistics of this report, however, have been the subject of some dispute. The V-1 missiles launched from bombers were often prone to exploding prematurely, occasionally resulting in the loss of the aircraft to which they were attached. The Luftwaffe lost 77 aircraft in 1,200 of these sorties.

The statistics of this report, however, have been the subject of some dispute. The V-1 missiles launched from bombers were often prone to exploding prematurely, occasionally resulting in the loss of the aircraft to which they were attached. The Luftwaffe lost 77 aircraft in 1,200 of these sorties.

The United States reverse-engineered the V-1 in 1944 from salvaged parts recovered in England during June. By 8 September, the first of thirteen complete prototype

The United States reverse-engineered the V-1 in 1944 from salvaged parts recovered in England during June. By 8 September, the first of thirteen complete prototype

;Australia

* The

;Australia

* The  ;Canada

* The

;Canada

* The  ;Switzerland

*A restored original V-1 is on display, as well as one of only six worldwide remaining original Reichenberg (Re 4-27), at the Swiss Military Museum in Full

;United Kingdom

;Switzerland

*A restored original V-1 is on display, as well as one of only six worldwide remaining original Reichenberg (Re 4-27), at the Swiss Military Museum in Full

;United Kingdom

* A reproduction V-1 is located at the Eden Camp in North Yorkshire.

* Fi-103 serial number 442795 is on display at the

* A reproduction V-1 is located at the Eden Camp in North Yorkshire.

* Fi-103 serial number 442795 is on display at the

Headcorn (Lashenden) Airfield's Air Warfare Museum

* A V-1 is on display with a V-2 in the new Atrium of the * A V-1 is on display at the US Army Air Defense Artillery Museum, Fort Sill, OK.

* FZG-76 is on display as a war memorial at the southwest corner of the Putnam County Courthouse in Greencastle, Indiana.

* The Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

* A V-1 is on display at the

* A V-1 is on display at the US Army Air Defense Artillery Museum, Fort Sill, OK.

* FZG-76 is on display as a war memorial at the southwest corner of the Putnam County Courthouse in Greencastle, Indiana.

* The Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

* A V-1 is on display at the

V-1 Launch Site

* ttp://www.warbirdsresourcegroup.org/LRG/v1.html Fi-103/V-1 "Buzz Bomb", from the Luftwaffe Resource Center website, hosted by The Warbirds Resource Group; with 42 photos

The Lambeth Archives, includes a sound recording of an incoming V-1, circa 1944

Swedish site (in English) with text and many details of the V-1 cruise missile and its supporting hardware

{{DEFAULTSORT:V-1 (Flying Bomb) Cruise missiles of Germany V-01 V-weapons World War II jet aircraft of Germany World War II guided missiles of Germany Single-engined jet aircraft Pulsejet-powered aircraft Mid-wing aircraft German inventions of the Nazi period Unmanned military aircraft of Germany Weapons and ammunition introduced in 1944 Aircraft first flown in 1942

cruise missile

A cruise missile is a guided missile used against terrestrial or naval targets that remains in the atmosphere and flies the major portion of its flight path at approximately constant speed. Cruise missiles are designed to deliver a large warhea ...

. Its official Reich Aviation Ministry () designation was Fi 103. It was also known to the Allies as the buzz bomb or doodlebug and in Germany as (cherry

A cherry is the fruit of many plants of the genus '' Prunus'', and is a fleshy drupe (stone fruit).

Commercial cherries are obtained from cultivars of several species, such as the sweet '' Prunus avium'' and the sour '' Prunus cerasus''. The ...

stone) or ( maybug).

The V-1 was the first of the (V-weapons

V-weapons, known in original German as (, German: "retaliatory weapons", "reprisal weapons"), were a particular set of long-range artillery weapons designed for strategic bombing during World War II, particularly strategic bombing and/or aer ...

) deployed for the terror bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

of London. It was developed at Peenemünde Army Research Center

The Peenemünde Army Research Center (german: Heeresversuchsanstalt Peenemünde, HVP) was founded in 1937 as one of five military proving grounds under the German Army Weapons Office (''Heereswaffenamt''). Several German guided missiles and ...

in 1939 by the at the beginning of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, and during initial development was known by the codename

A code name, call sign or cryptonym is a code word or name used, sometimes clandestinely, to refer to another name, word, project, or person. Code names are often used for military purposes, or in espionage. They may also be used in industrial c ...

"Cherry Stone". Because of its limited range, the thousands of V-1 missiles launched into England were fired from launch facilities along the French (Pas-de-Calais

Pas-de-Calais (, " strait of Calais"; pcd, Pas-Calés; also nl, Nauw van Kales) is a department in northern France named after the French designation of the Strait of Dover, which it borders. It has the most communes of all the departments ...

) and Dutch coasts.

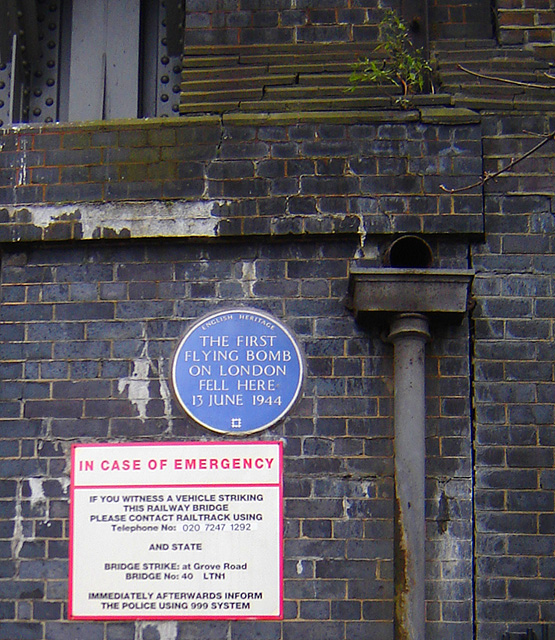

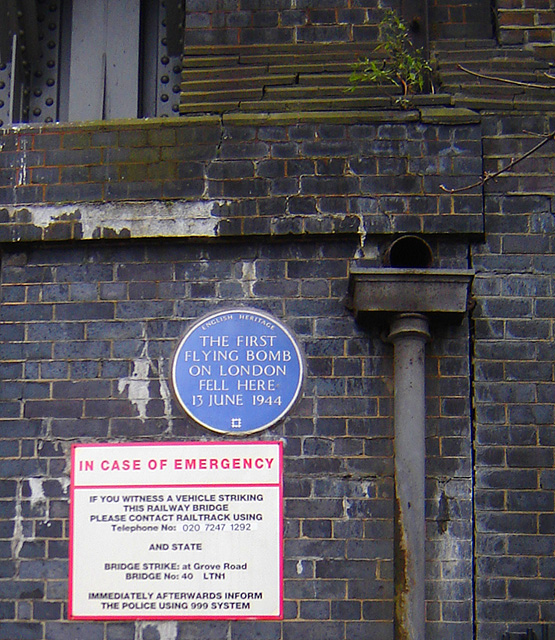

The Wehrmacht first launched the V-1s against London on 13 June 1944, one week after (and prompted by) the successful Allied landings in France. At peak, more than one hundred V-1s a day were fired at southeast England, 9,521 in total, decreasing in number as sites were overrun until October 1944, when the last V-1 site in range of Britain was overrun by Allied forces. After this, the Germans directed V-1s at the port of Antwerp and at other targets in Belgium, launching a further 2,448 V-1s. The attacks stopped only a month before the war in Europe ended, when the last launch site in the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

was overrun on 29 March 1945.

As part of operations against the V-1, the British operated an arrangement of air defence

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based ...

s, including anti-aircraft guns, barrage balloon

A barrage balloon is a large uncrewed tethered balloon used to defend ground targets against aircraft attack, by raising aloft steel cables which pose a severe collision risk to aircraft, making the attacker's approach more difficult. Early barr ...

s, and fighter aircraft, to intercept the bombs before they reached their targets, while the launch sites and underground storage depots became targets for Allied attacks including strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systemati ...

.

In 1944, a number of tests of this weapon were conducted in Tornio, Finland. According to multiple soldiers, a small "plane"-like bomb with wings fell off a German plane. Another V-1 was launched which flew over the Finnish soldiers' lines. The second bomb suddenly stopped its engine and fell steeply down, exploding and leaving a crater around 20 to 30 metres wide. The V-1 flying bomb was referred by Finnish soldiers as a "Flying Torpedo" due to its resemblance to one from afar.

Design and development

In 1935, Paul Schmidt and Professor Georg Hans Madelung submitted a design to the ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

'' for a flying bomb

A flying bomb is a manned or unmanned aerial vehicle or aircraft carrying a large explosive warhead, a precursor to contemporary cruise missiles. In contrast to a bomber aircraft, which is intended to release bombs and then return to its base for ...

. It was an innovative design that used a pulse-jet engine, while previous work dating back to 1915 by Sperry Gyroscope relied on propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

s. While employed by the company, Fritz Gosslau developed a remote-controlled target drone

A target drone is an unmanned aerial vehicle, generally remote controlled, usually used in the training of anti-aircraft crews.

One of the earliest drones was the British DH.82 Queen Bee, a variant of the Tiger Moth trainer aircraft operational ...

, the FZG 43 (''Flakzielgerat-43''). In October 1939, Argus proposed ''Fernfeuer'', a remote-controlled aircraft carrying a payload of one ton, that could return to base after releasing its bomb. Argus worked in co-operation with C. Lorenz AG and Arado Flugzeugwerke

Arado Flugzeugwerke was a German aircraft manufacturer, originally established as the Warnemünde factory of the Flugzeugbau Friedrichshafen firm, that produced land-based military aircraft and seaplanes during the First and Second World Wars.

Hi ...

to develop the project. However, once again, the ''Luftwaffe'' declined to award a development contract. In 1940, Schmidt and Argus began cooperating, integrating Schmidt's shutter system with Argus' atomized fuel injection

Fuel injection is the introduction of fuel in an internal combustion engine, most commonly automotive engines, by the means of an injector. This article focuses on fuel injection in reciprocating piston and Wankel rotary engines.

All com ...

. Tests began in January 1941, and the first flight made on 30 April 1941 with a Gotha Go 145. On 27 February 1942, Gosslau and Robert Lusser sketched out the design of an aircraft with the pulse-jet above the tail, the basis for the future V-1.

Lusser produced a preliminary design in April 1942, P35 Efurt, which used gyroscopes. When submitted to the ''Luftwaffe'' on 5 June 1942, the specifications included a range of , a speed of , and capable of delivering a warhead

A warhead is the forward section of a device that contains the explosive agent or toxic (biological, chemical, or nuclear) material that is delivered by a missile, rocket, torpedo, or bomb.

Classification

Types of warheads include:

*Explos ...

. Project Fieseler

The Gerhard Fieseler Werke (GFW) in Kassel was a German aircraft manufacturer of the 1930s and 1940s. The company is remembered mostly for its military aircraft built for the Luftwaffe during the Second World War.

History

The firm was founded on ...

Fi 103 was approved on 19 June, and assigned code name

A code name, call sign or cryptonym is a code word or name used, sometimes clandestinely, to refer to another name, word, project, or person. Code names are often used for military purposes, or in espionage. They may also be used in industrial c ...

''Kirschkern'' and cover name ''Flakzielgerat'' 76 (FZG-76). Flight tests were conducted at the ''Luftwaffes coastal test centre at Karlshagen

Karlshagen is a Baltic Sea resort in Western Pomerania in the north of the island Usedom. Karlshagen has 3400 inhabitants and lies between Zinnowitz and Peenemünde.

In 1885, a pier was developed in Karlshagen. Today it is the most important ...

, Peenemünde-West.

Milch awarded Argus the contract for the engine, Fieseler the airframe

The mechanical structure of an aircraft is known as the airframe. This structure is typically considered to include the fuselage, undercarriage, empennage and wings, and excludes the propulsion system.

Airframe design is a field of aero ...

, and Askania the guidance system

A guidance system is a virtual or physical device, or a group of devices implementing a controlling the movement of a ship, aircraft, missile, rocket, satellite, or any other moving object. Guidance is the process of calculating the changes ...

. By 30 August, Fieseler had completed the first fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an engine as well, although in some amphibious aircraft t ...

, and the first flight of the Fi 103 V7 took place on 10 December 1942, when it was airdropped by a Fw 200. Then on Christmas Eve, the V-1 flew , for about a minute, after a ground launch. On 26 May 1943, Germany decided to put both the V-1 and the V-2 into production. In July 1943, the V-1 flew 245 kilometres and impacted within a kilometre of its target.

The V-1 was named by '' Das Reich'' journalist Hans Schwarz Van Berkl in June 1944 with Hitler's approval.

Description

The V-1 was designed under the codename (cherry stone) by Lusser and Gosslau, with a

The V-1 was designed under the codename (cherry stone) by Lusser and Gosslau, with a fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an engine as well, although in some amphibious aircraft t ...

constructed mainly of welded sheet steel

Sheet metal is metal formed into thin, flat pieces, usually by an industrial process. Sheet metal is one of the fundamental forms used in metalworking, and it can be cut and bent into a variety of shapes.

Thicknesses can vary significantly; ex ...

and wings built of plywood. The simple, Argus-built pulsejet engine pulsed 50 times per second, and the characteristic buzzing sound gave rise to the colloquial names "buzz bomb" or "doodlebug" (a common name for a wide variety of flying insects). It was known briefly in Germany (on Hitler's orders) as ( May bug) and (crow).

Power plant

pulsejet

300px, Diagram of a pulsejet

A pulsejet engine (or pulse jet) is a type of jet engine in which combustion occurs in pulses. A pulsejet engine can be made with few or no moving parts, and is capable of running statically (i.e. it does not need ...

's major components included the nacelle

A nacelle ( ) is a "streamlined body, sized according to what it contains", such as an engine, fuel, or equipment on an aircraft. When attached by a pylon entirely outside the airframe, it is sometimes called a pod, in which case it is attached ...

, fuel jets, flap valve grid, mixing chamber venturi, tail pipe, and spark plug. Compressed air rather than a fuel pump forced gasoline from the fuel tank through the fuel jets which consisted of three banks of three atomizers. These nine atomizing nozzles were in front of the air inlet valve system where it mixed with air before entering the chamber. A throttle valve, connected to altitude and ram pressure instruments, controlled fuel flow. Schmidt's spring-controlled flap valve system provided an efficient straight path for incoming air. The flaps momentarily closed after each explosion, the resultant gas compressed in the venturi chamber, and its tapered portion accelerated the exhaust gases creating thrust

Thrust is a reaction force

In physics, a force is an influence that can change the motion of an object. A force can cause an object with mass to change its velocity (e.g. moving from a state of rest), i.e., to accelerate. Force can al ...

. The operation proceeded at a rate of 42 cycles per second.

Beginning in January 1941, the V-1's pulsejet engine was also tested on a variety of craft, including automobiles and an experimental attack boat known as the Tornado. The unsuccessful prototype was a version of a , in which a boat loaded with explosives was steered towards a target ship and the pilot would leap out of the back at the last moment. The Tornado was assembled from surplus seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tec ...

hulls connected in catamaran fashion with a small pilot cabin on the crossbeams. The Tornado prototype was a noisy underperformer and was abandoned in favour of more conventional piston-engine

A reciprocating engine, also often known as a piston engine, is typically a heat engine that uses one or more reciprocating pistons to convert high temperature and high pressure into a rotating motion. This article describes the common feat ...

craft.

The engine made its first flight aboard a Gotha Go 145 on 30 April 1941.

Guidance system

The V-1

The V-1 guidance system

A guidance system is a virtual or physical device, or a group of devices implementing a controlling the movement of a ship, aircraft, missile, rocket, satellite, or any other moving object. Guidance is the process of calculating the changes ...

used a simple autopilot

An autopilot is a system used to control the path of an aircraft, marine craft or spacecraft without requiring constant manual control by a human operator. Autopilots do not replace human operators. Instead, the autopilot assists the operator' ...

developed by Askania

A cinetheodolite (a.k.a. ''kinetheodolite'') is a photographic instrument for collection of trajectory data. It can be used to acquire data in the testing of missiles, rockets, projectiles, aircraft, and fire control systems; in the ripple f ...

in Berlin to regulate altitude and airspeed. A pair of gyroscopes controlled yaw and pitch, while azimuth was maintained by a magnetic compass. Altitude was maintained by a barometric device. Two spherical tanks contained compressed air at , that drove the gyros, operated the pneumatic servo-motors controlling the rudder and elevator, and pressurized the fuel system.

The magnetic compass was located near the front of the V1, within a wooden sphere. Just before launch, the V1 was suspended inside the Compass Swinging Building (Richthaus). There the compass was corrected for magnetic variance and magnetic deviation

Magnetic deviation is the error induced in a compass by ''local'' magnetic fields, which must be allowed for, along with magnetic declination, if accurate bearings are to be calculated. (More loosely, "magnetic deviation" is used by some to mean ...

.

The RLM at first planned to use a radio control system with the V-1 for precision attacks, but the government decided instead to use the missile against London. Some flying bombs were equipped with a basic radio transmitter operating in the range of 340–450 kHz. Once over the channel, the radio would be switched on by the vane counter, and a aerial deployed. A coded Morse signal, unique to each V1 site, transmitted the route, and impact zone calculated once the radio stopped transmitting.

An odometer driven by a vane anemometer on the nose determined when the target area had been reached, accurate enough for area bombing

In military aviation, area bombardment (or area bombing) is a type of aerial bombardment in which bombs are dropped over the general area of a target. The term "area bombing" came into prominence during World War II.

Area bombing is a form of st ...

. Before launch, it was set to count backwards from a value that would reach zero upon arrival at the target in the prevailing wind conditions. As the missile flew, the airflow turned the propeller, and every 30 rotations of the propeller counted down one number on the odometer. This odometer triggered the arming of the warhead after about . When the count reached zero, two detonating bolts were fired. Two spoilers on the elevator

An elevator or lift is a cable-assisted, hydraulic cylinder-assisted, or roller-track assisted machine that vertically transports people or freight between floors, levels, or decks of a building, vessel, or other structure. They ar ...

were released, the linkage between the elevator and servo was jammed, and a guillotine

A guillotine is an apparatus designed for efficiently carrying out executions by beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secured with stocks at t ...

device cut off the control hoses to the rudder servo, setting the rudder in neutral. These actions put the V-1 into a steep dive. While this was originally intended to be a power dive, in practice the dive caused the fuel flow to cease, which stopped the engine. The sudden silence after the buzzing alerted listeners of the impending impact.

Initially, V-1s landed within a circle in diameter, but by the end of the war, accuracy had been improved to about , which was comparable to the V-2 rocket

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name '' Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was develop ...

.

Warhead

The warhead consisted of 850 kg ofAmatol

Amatol is a highly explosive material made from a mixture of TNT and ammonium nitrate. The British name originates from the words ammonium and toluene (the precursor of TNT). Similar mixtures (one part dinitronaphthalene and seven parts amm ...

, 52A+ high-grade blast-effective explosive with three fuses. An electrical fuse could be triggered by nose or belly impact. Another fuse was a slow-acting mechanical fuse allowing deeper penetration into the ground, regardless of the altitude. The third fuse was a delayed action fuse, set to go off two hours after launch.

The purpose of the third fuse was to avoid the risk of this secret weapon being examined by the British. Its time delay was too short to be a useful booby trap, but was instead meant to destroy the weapon if a soft landing had not triggered the impact fuses. These fusing systems were very reliable, and almost no dud V-1s were recovered.

Walter catapult

Ground-launched V-1s were propelled up an inclined launch ramp by an apparatus known as a ("steam generator"), in which steam was generated when

Ground-launched V-1s were propelled up an inclined launch ramp by an apparatus known as a ("steam generator"), in which steam was generated when hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscous than water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usually as a dilute solution (3% ...

(T-Stoff

T-Stoff (; 'substance T') was a stabilised high test peroxide used in Germany during World War II. T-Stoff was specified to contain 80% (occasionally 85%) hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), remainder water, with traces (<0.1%) of stabilisers. Stabilisers ...

) was mixed with sodium permanganate

Sodium permanganate is the inorganic compound with the formula Na MnO4. It is closely related to the more commonly encountered potassium permanganate, but it is generally less desirable, because it is more expensive to produce. It is mainly avai ...

(Z-Stoff

Z-Stoff (, "substance Z") was a name for calcium permanganate or sodium permanganate mixed in water. It was normally used as a catalyst for T-Stoff (high-test peroxide) in military rocket programs by Nazi Germany during World War II.

Z-Stoff was ...

). Designed by Hellmuth Walter Kommanditgesellschaft Hellmuth Walter Kommanditgesellschaft (HWK), Helmuth Walter Werke (HWM), or commonly known as the Walter-Werke, was a German company founded by Professor Hellmuth Walter to pursue his interest in engines using hydrogen peroxide as a fuel.

Having ex ...

, the WR 2.3 Schlitzrohrschleuder consisted of a small gas generator trailer, where the T-Stoff and Z-Stoff combined, generating high-pressure steam that was fed into a tube within the launch rail box. A piston in the tube, connected underneath the missile, was propelled forward by the steam. It is a common misconception that this was done to allow the engine to start running but this is not true. It was done because the Argus didn't have enough power to propel the V1 to a speed over its incredibly high stall speed. The launch rail was long, consisting of 8 modular sections, each long, and a muzzle brake. Production of the Walter catapult began in January 1944.

The Walter catapult accelerated the V-1 to a launch speed of , well above the needed minimum operational speed of . The V-1 made British landfall at , but accelerated to over London, as its of fuel burned off.

On 18 June 1943,

The Walter catapult accelerated the V-1 to a launch speed of , well above the needed minimum operational speed of . The V-1 made British landfall at , but accelerated to over London, as its of fuel burned off.

On 18 June 1943, Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

decided on launching the V-1, using the Walter catapult, in both large launch bunkers, called Wasserwerk, and lighter installations, called the Stellungsystem. The Wasserwerk bunker measured long, wide, and high. Four were initially to be built: Wasserwerk Desvres, Wasserwerk St. Pol, Wasserwerk Valognes, and Wasserwerk Cherbourg. Stellungsystem-I was to be operated by Flak Regiment 155(W), with 4 launch battalions, each having 4 launchers, and located in the Pas-de-Calais

Pas-de-Calais (, " strait of Calais"; pcd, Pas-Calés; also nl, Nauw van Kales) is a department in northern France named after the French designation of the Strait of Dover, which it borders. It has the most communes of all the departments ...

region. Stellungsystem-II, with 32 sites, was to act as a reserve unit. Stellungsystem-I and II had nine batteries manned by February 1944. Stellungsystem-III, operated by FR 255(W), was to be organized in the spring of 1944, and located between Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

and Caen

Caen (, ; nrf, Kaem) is a commune in northwestern France. It is the prefecture of the department of Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inhabitants (), while its functional urban area has 470,000,Oberst

''Oberst'' () is a senior field officer rank in several German-speaking and Scandinavian countries, equivalent to colonel. It is currently used by both the ground and air forces of Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Denmark, and Norway. The Swe ...

Schmalschläger had developed a more simplified launching site, called Einsatz Stellungen. Less conspicuous, 80 launch sites and 16 support sites were located from Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. The p ...

to Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

. Each site took only 2 weeks to construct, using 40 men, and the Walter catapult only took 7–8 days to erect, when the time was ready to make it operational.

Once near the launch ramp, the wing spar and wings were attached and the missile was slid off the loading trolley, Zubringerwagen, onto the launch ramp. The ramp catapult was powered by the Dampferzeuger trolley. The pulse-jet engine was started by the Anlassgerät, which provided compressed air for the engine intake, and electrical connection to the engine spark plug

A spark plug (sometimes, in British English, a sparking plug, and, colloquially, a plug) is a device for delivering electric current from an ignition system to the combustion chamber of a spark-ignition engine to ignite the compressed fuel/air ...

, and autopilot. The Bosch

Bosch may refer to:

People

* Bosch (surname)

* Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450 – 1516), painter

* Van den Bosch, a Dutch toponymic surname

* Carl Bosch, a German chemical engineer and nephew of Robert Bosch

* Robert Bosch, founder of Robert Bosch Gm ...

spark plug was only needed to start the engine, while residual flame ignited further mixtures of gasoline and air, and the engine would be at full power after 7 seconds. The catapult would then accelerate the bomb above its stall speed of , and ensuring sufficient ram air.

Operation Eisbär

Mass production of the FZG-76 did not start until the spring of 1944, and FR 155(W) was not equipped until late May 1944. Operation Eisbär, the missile attacks on London, commenced on 12 June. However, the four launch battalions could only operate from the Pas-de-Calais area, amounting to only 72 launchers. They had been supplied with missiles, Walter catapults, fuel, and other associated equipment since D-Day. None of the nine missiles launched on the 12th reached England, while only four did so on the 13th. The next attempt to start the attack occurred on the night of 15/16 June, when 144 missiles reached England, of which 73 struck London, while 53 struckPortsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city status in the United Kingdom, city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is admi ...

and Southampton

Southampton () is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire, S ...

.

Damage was widespread and Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

ordered attacks on the V-1 sites as a priority. Operation Cobra

Operation Cobra was the codename for an offensive launched by the United States First Army under Lieutenant General Omar Bradley seven weeks after the D-Day landings, during the Normandy campaign of World War II. The intention was to take ...

forced a retreat from the French launch sites in August, with the last battalion leaving on 29 August. Operation Donnerschlag began from Germany on 21 October 1944.

Operation and effectiveness

The first complete V-1 airframe was delivered on 30 August 1942, and after the first complete As.109-014 was delivered in September, the first glide test flight was on 28 October 1942 at

The first complete V-1 airframe was delivered on 30 August 1942, and after the first complete As.109-014 was delivered in September, the first glide test flight was on 28 October 1942 at Peenemünde

Peenemünde (, en, " Peene iverMouth") is a municipality on the Baltic Sea island of Usedom in the Vorpommern-Greifswald district in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is part of the ''Amt'' (collective municipality) of Usedom-Nord. The co ...

, from under a Focke-Wulf Fw 200. The first powered trial was on 10 December, launched from beneath an He 111.

The LXV ''Armeekorps z.b.V.'' ("65th Army Corps for special deployment) formed during the last days of November 1943 in France commanded by ''General der Artillerie z.V.'' Erich Heinemann

The given name Eric, Erich, Erikk, Erik, Erick, or Eirik is derived from the Old Norse name ''Eiríkr'' (or ''Eríkr'' in Old East Norse due to monophthongization).

The first element, ''ei-'' may be derived from the older Proto-Norse ''* ain ...

was responsible for the operational use of V-1.

The conventional launch sites could theoretically launch about 15 V-1s per day, but this rate was difficult to achieve on a consistent basis; the maximum rate achieved was 18. Overall, only about 25% of the V-1s hit their targets, the majority being lost because of a combination of defensive measures, mechanical unreliability or guidance errors. With the capture or destruction of the launch facilities used to attack England, the V-1s were employed in attacks against strategic points in Belgium, primarily the port of Antwerp.

Launches against Britain were met by a variety of countermeasures, including

The conventional launch sites could theoretically launch about 15 V-1s per day, but this rate was difficult to achieve on a consistent basis; the maximum rate achieved was 18. Overall, only about 25% of the V-1s hit their targets, the majority being lost because of a combination of defensive measures, mechanical unreliability or guidance errors. With the capture or destruction of the launch facilities used to attack England, the V-1s were employed in attacks against strategic points in Belgium, primarily the port of Antwerp.

Launches against Britain were met by a variety of countermeasures, including barrage balloon

A barrage balloon is a large uncrewed tethered balloon used to defend ground targets against aircraft attack, by raising aloft steel cables which pose a severe collision risk to aircraft, making the attacker's approach more difficult. Early barr ...

s and aircraft such as the Hawker Tempest

The Hawker Tempest is a British fighter aircraft that was primarily used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the Second World War. The Tempest, originally known as the ''Typhoon II'', was an improved derivative of the Hawker Typhoon, intended to a ...

and newly introduced jet Gloster Meteor

The Gloster Meteor was the first British jet fighter and the Allies' only jet aircraft to engage in combat operations during the Second World War. The Meteor's development was heavily reliant on its ground-breaking turbojet engines, pioneere ...

. These measures were so successful that by August 1944 about 80% of V-1s were being destroyed (Although the Meteors were fast enough to catch the V-1s, they suffered from frequent cannon failures, and accounted for only 13.) In all, about 1,000 V-1s were destroyed by aircraft.

The intended operational altitude was originally set at . However, repeated failures of a barometric fuel-pressure regulator led to it being changed in May 1944, halving the operational height, thereby bringing V-1s into range of the 40mm Bofors light anti-aircraft guns commonly used by Allied AA units.

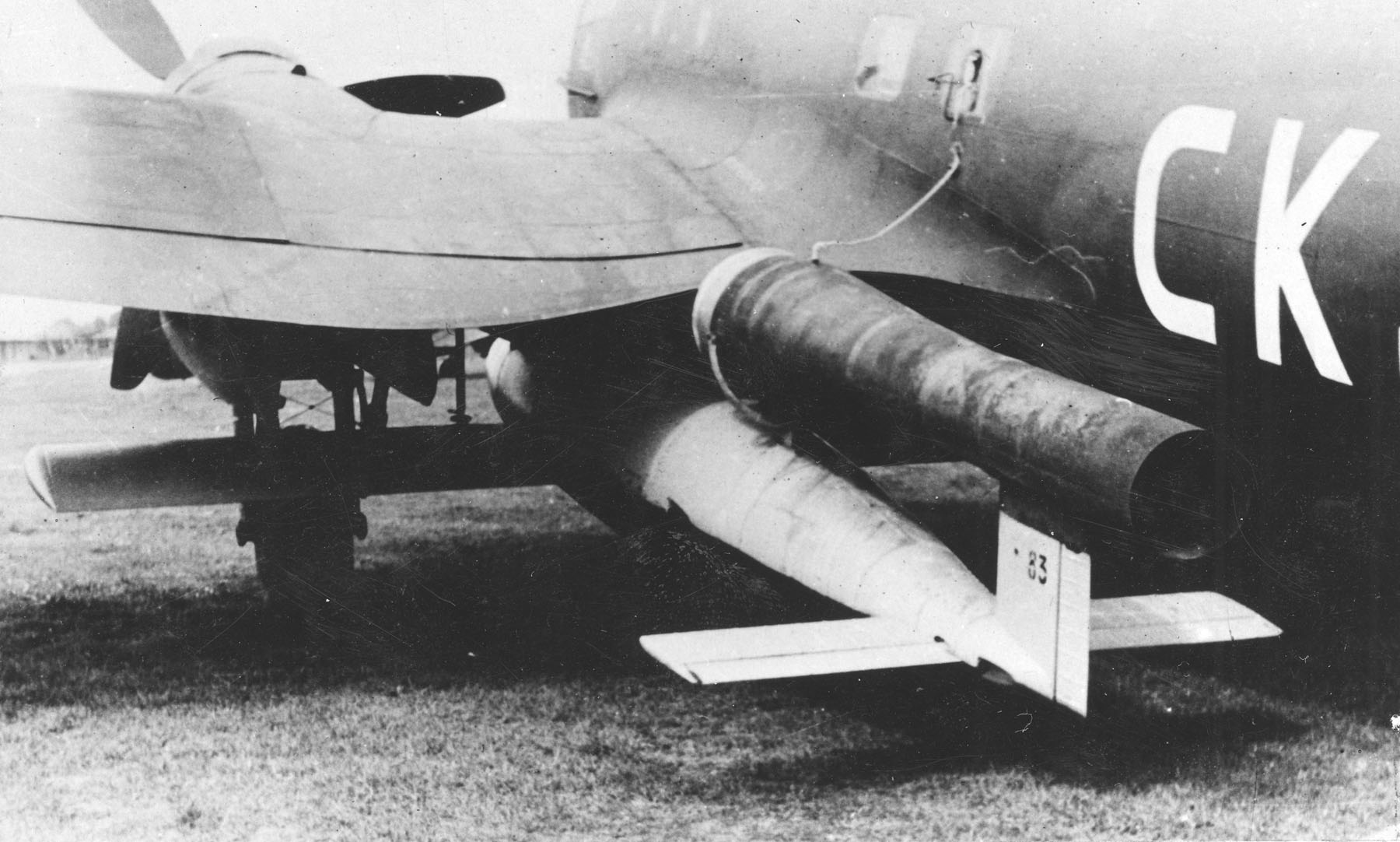

The trial versions of the V-1 were air-launched. Most operational V-1s were launched from static sites on land, but from July 1944 to January 1945, the launched approximately 1,176 from modified

The trial versions of the V-1 were air-launched. Most operational V-1s were launched from static sites on land, but from July 1944 to January 1945, the launched approximately 1,176 from modified Heinkel He 111

The Heinkel He 111 is a German airliner and bomber designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter at Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in 1934. Through development, it was described as a " wolf in sheep's clothing". Due to restrictions placed on Germany after t ...

H-22s of the 's '' Kampfgeschwader 3'' (3rd Bomber Wing, the so-called "Blitz Wing") flying over the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

. Apart from the obvious motive of permitting the bombardment campaign to continue after static ground sites on the French coast were lost, air launching gave the the opportunity to outflank the increasingly effective ground and air defences put up by the British against the missile. To minimise the associated risks (primarily radar detection), the aircrews developed a tactic called "lo-hi-lo": the He 111s would, upon leaving their airbases and crossing the coast, descend to an exceptionally low altitude. When the launch point was neared, the bombers would swiftly ascend, fire their V-1s, and then rapidly descend again to the previous "wave-top" level for the return flight. Research after the war estimated a 40% failure rate of air-launched V-1s, and the He 111s used in this role were vulnerable to night-fighter attack, as the launch lit up the area around the aircraft for several seconds. The combat potential of air-launched V-1s dwindled during 1944 at about the same rate as that of the ground-launched missiles, as the British gradually took the measure of the weapon and developed increasingly effective defence tactics.

Experimental, piloted, and long-range variants

Piloted variant

Late in the war, several air-launched piloted V-1s, known as , were built, but these were never used in combat.

Late in the war, several air-launched piloted V-1s, known as , were built, but these were never used in combat. Hanna Reitsch

Hanna Reitsch (29 March 1912 – 24 August 1979) was a German aviator and test pilot. Along with Melitta von Stauffenberg, she flight tested many of Germany's new aircraft during World War II and received many honors. Reitsch was amo ...

made some flights in the modified V-1 Fieseler when she was asked to find out why test pilots were unable to land it and had died as a result. She discovered, after simulated landing attempts at high altitude, where there was air space to recover, that the craft had an extremely high stall speed

In fluid dynamics, a stall is a reduction in the lift coefficient generated by a foil as angle of attack increases.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition'', p. 486. Aviation Supplies & Academics, 1997. This occurs when t ...

, and the previous pilots with little high-speed experience had attempted their approaches much too slowly. Her recommendation of much higher landing speeds was then introduced in training new volunteer pilots. The s were air-launched rather than fired from a catapult ramp, as erroneously portrayed in the film ''Operation Crossbow

''Crossbow'' was the code name in World War II for Anglo-American operations against the German long range reprisal weapons (V-weapons) programme.

The main V-weapons were the V-1 flying bomb and V-2 rocket – these were launched against Brita ...

''.

Air launch by Ar 234

Arado Ar 234

The Arado Ar 234 ''Blitz'' (English: lightning) is a jet-powered bomber designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Arado. It was the world's first operational turbojet-powered bomber, seeing service during the latter half of ...

jet bomber to launch V-1s either by towing them aloft or by launching them from a "piggy back" position (in the manner of the , but in reverse) atop the aircraft. In the latter configuration, a pilot-controlled, hydraulically operated dorsal trapeze mechanism would elevate the missile on the trapeze's launch cradle about clear of the 234's upper fuselage. This was necessary to avoid damaging the mother craft's fuselage and tail surfaces when the pulsejet ignited, as well as to ensure a "clean" airflow for the Argus motor's intake. A somewhat less ambitious project undertaken was the adaptation of the missile as a "flying fuel tank" for the Messerschmitt Me 262

The Messerschmitt Me 262, nicknamed ''Schwalbe'' (German: "Swallow") in fighter versions, or ''Sturmvogel'' (German: "Procellariidae, Storm Bird") in fighter-bomber versions, is a fighter aircraft and fighter-bomber that was designed and produc ...

jet fighter, which was initially test-towed behind an He 177A Greif bomber. The pulsejet, internal systems and warhead of the missile were removed, leaving only the wings and basic fuselage, now containing a single large fuel tank. A small cylindrical module, similar in shape to a finless dart, was placed atop the vertical stabiliser at the rear of the tank, acting as a centre of gravity balance and attachment point for a variety of equipment sets. A rigid towbar with a pitch pivot at the forward end connected the flying tank to the Me 262. The operational procedure for this unusual configuration saw the tank resting on a wheeled trolley for take-off. The trolley was dropped once the combination was airborne, and explosive bolts separated the towbar from the fighter upon exhaustion of the tank's fuel supply. A number of test flights were conducted in 1944 with this set-up, but inflight "porpoising" of the tank, with the instability transferred to the fighter, meant that the system was too unreliable to be used. An identical utilisation of the V-1 flying tank for the Ar 234 bomber was also investigated, with the same conclusions reached. Some of the "flying fuel tanks" used in trials utilised a cumbersome fixed and spatted undercarriage arrangement, which (along with being pointless) merely increased the drag and stability problems already inherent in the design.

F-1 version

One variant of the basic Fi 103 design did see operational use. The progressive loss of French launch sites as 1944 proceeded and the area of territory under German control shrank meant that soon the V-1 would lack the range to hit targets in England. Air launching was one alternative utilised, but the most obvious solution was to extend the missile's range. Thus the F-1 version developed. The weapon's fuel tank was increased in size, with a corresponding reduction in the capacity of the warhead. Additionally, the nose cones and wings of the F-1 models were made of wood, affording a considerable weight saving. With these modifications, the V-1 could be fired at London and nearby urban centres from prospective ground sites in the Netherlands. Frantic efforts were made to construct a sufficient number of F-1s in order to allow a large-scale bombardment campaign to coincide with theArdennes Offensive

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive, was the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front during World War II. The battle lasted from 16 December 1944 to 28 January 1945, towards the end of the war in ...

, but numerous factors (bombing of the factories producing the missiles, shortages of steel and rail transport, the chaotic tactical situation Germany was facing at this point in the war, etc.) delayed the delivery of these long-range V-1s until February/March 1945. Beginning on 2 March 1945, slightly more than three weeks before the V-1 campaign finally ended, several hundred F-1s were launched at Britain from Dutch sites under Operation "Zeppelin". Frustrated by increasing Allied dominance in the air, Germany also employed V-1s to attack the RAF's forward airfields, such as Volkel, in the Netherlands.

FZG-76 version

There was also aturbojet

The turbojet is an airbreathing jet engine which is typically used in aircraft. It consists of a gas turbine with a propelling nozzle. The gas turbine has an air inlet which includes inlet guide vanes, a compressor, a combustion chamber, ...

-propelled upgraded variant proposed, meant to use the Porsche 109-005 low-cost turbojet engine with about thrust.

Success of operations

Almost 30,000 V-1s were made; by March 1944, they were each produced in 350 hours (including 120 for the autopilot), at a cost of just 4% of aV-2

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was developed ...

, which delivered a comparable payload. Approximately 10,000 were fired at England; 2,419 reached London, killing about 6,184 people and injuring 17,981. The greatest density of hits was received by Croydon

Croydon is a large town in south London, England, south of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Croydon, a local government district of Greater London. It is one of the largest commercial districts in Greater London, with an extens ...

, on the south-east fringe of London. Antwerp, Belgium was hit by 2,448 V-1s from October 1944 to March 1945.

Intelligence reports

The codename " 76"—"Flak

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

target apparatus" helped to hide the nature of the device, and some time passed before references to FZG 76 were linked to the V-83 pilotless aircraft (an experimental V-1) that had crashed on Bornholm

Bornholm () is a Danish island in the Baltic Sea, to the east of the rest of Denmark, south of Sweden, northeast of Germany and north of Poland.

Strategically located, Bornholm has been fought over for centuries. It has usually been ruled by ...

in the Baltic and to reports from agents of a flying bomb capable of being used against London. Importantly, the Luxembourgish Resistance

When Luxembourg was invaded and annexed by Nazi Germany in 1940, a national consciousness started to come about. From 1941 onwards, the first resistance groups, such as the '' Letzeburger Ro'de Lé'w'' or the ''PI-Men'', were founded. Operating un ...

, as well as the Polish Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant Polish resistance movement in World War II, resistance movement in Occupation of Poland (1939–1945), German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed i ...

intelligence contributed information on V-1 construction and a place of development (Peenemünde). Initially, British experts were sceptical of the V-1 because they had considered only solid-fuel rocket

A solid-propellant rocket or solid rocket is a rocket with a rocket engine that uses solid propellants (fuel/ oxidizer). The earliest rockets were solid-fuel rockets powered by gunpowder; they were used in warfare by the Arabs, Chinese, Persi ...

s, which could not attain the stated range of . However, they later considered other types of engine, and by the time German scientists had achieved the needed accuracy to deploy the V-1 as a weapon, British intelligence had a very accurate assessment of it.

Countermeasures in England

Anti-aircraft guns

The British defence against German long-range weapons was known by the codename Crossbow with

The British defence against German long-range weapons was known by the codename Crossbow with Operation Diver

Operation Diver was the British codename for countermeasures against the V-1 flying bomb campaign launched by the German in 1944 against London and other parts of Britain. Diver was the codename for the V-1, against which the defence consisted of ...

covering countermeasures to the V-1. Anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

guns of the Royal Artillery and RAF Regiment

The Royal Air Force Regiment (RAF Regiment) is part of the Royal Air Force and functions as a specialist corps. Founded by royal warrant in 1942, the Corps carries out soldiering tasks relating to the delivery of air power. Examples of such tas ...

redeployed in several movements: first in mid-June 1944 from positions on the North Downs

The North Downs are a ridge of chalk hills in south east England that stretch from Farnham in Surrey to the White Cliffs of Dover in Kent. Much of the North Downs comprises two Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs): the Surrey Hills ...

to the south coast of England, then a cordon closing the Thames Estuary

The Thames Estuary is where the River Thames meets the waters of the North Sea, in the south-east of Great Britain.

Limits

An estuary can be defined according to different criteria (e.g. tidal, geographical, navigational or in terms of salini ...

to attacks from the east. In September 1944, a new linear defence line was formed on the coast of East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

, and finally in December there was a further layout along the Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershir ...

–Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other English counties, functions have ...

coast. The deployments were prompted by changes to the approach tracks of the V-1 as launch sites were overrun by the Allies' advance.

On the first night of sustained bombardment, the anti-aircraft crews around Croydon were jubilant—suddenly they were downing unprecedented numbers of German bombers; most of their targets burst into flames and fell when their engines cut out. There was great disappointment when the truth was announced. Anti-aircraft gunners soon found that such small fast-moving targets were, in fact, very difficult to hit. The cruising altitude of the V-1, between meant that anti-aircraft guns could not traverse fast enough to hit the missile.

The altitude and speed were more than the rate of traverse of the standard British QF 3.7-inch mobile gun could cope with. The static version of the QF 3.7-inch, designed for use on a permanent, concrete platform, had a faster traverse. The cost and delay of installing new permanent platforms for the guns was fortunately found to be unnecessary, a temporary platform devised by the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers and made from railway sleepers and rails was found to be adequate for the static guns, making them considerably easier to re-deploy as the V-1 threat changed.

The development of the proximity fuze

A proximity fuze (or fuse) is a fuze that detonates an explosive device automatically when the distance to the target becomes smaller than a predetermined value. Proximity fuzes are designed for targets such as planes, missiles, ships at sea, an ...

and of centimetric, 3 gigahertz

The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), equivalent to one event (or cycle) per second. The hertz is an SI derived unit whose expression in terms of SI base units is s−1, meaning that one ...

frequency gun-laying radars based on the cavity magnetron

The cavity magnetron is a high-power vacuum tube used in early radar systems and currently in microwave ovens and linear particle accelerators. It generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons with a magnetic field ...

helped to counter the V-1's high speed and small size. In 1944, Bell Labs

Nokia Bell Labs, originally named Bell Telephone Laboratories (1925–1984),

then AT&T Bell Laboratories (1984–1996)

and Bell Labs Innovations (1996–2007),

is an American industrial research and scientific development company owned by mult ...

started delivery of an anti-aircraft predictor fire-control system

A fire-control system (FCS) is a number of components working together, usually a gun data computer, a Director (military), director, and radar, which is designed to assist a ranged weapon system to target, track, and hit a target. It performs ...

based on an analogue computer

An analog computer or analogue computer is a type of computer that uses the continuous variation aspect of physical phenomena such as electrical, mechanical, or hydraulic quantities (''analog signals'') to model the problem being solved. ...

, just in time for the Allied invasion of Europe.

These electronic aids arrived in quantity from June 1944, just as the guns reached their firing positions on the coast. Seventeen percent of all flying bombs entering the coastal "gun belt" were destroyed by guns in their first week on the coast. This rose to 60 percent by 23 August and 74 percent in the last week of the month, when on one day 82 percent were shot down. The rate improved from thousands of shells for every one V-1 destroyed to one for every 100. This mostly ended the V-1 threat. As General Frederick Pile put it in an April 5, 1946 article in the London Times

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events, and a fundamental quantity of measuring systems.

Time or times may also refer to:

Temporal measurement

* Time in physics, defined by its measurement

* Time standard, civil time specific ...

: "It was the proximity fuse which made possible the 100 percent successes that A.A. Command was obtaining regularly in the early months of last year...American scientists...gave us the final answer to the flying bomb."

Barrage balloons

Eventually about 2,000barrage balloon

A barrage balloon is a large uncrewed tethered balloon used to defend ground targets against aircraft attack, by raising aloft steel cables which pose a severe collision risk to aircraft, making the attacker's approach more difficult. Early barr ...

s were deployed, in the hope that V-1s would be destroyed when they struck the balloons' tethering cables. The leading edges of the V-1's wings were fitted with Kuto cable cutters, and fewer than 300 V-1s are known to have been brought down by barrage balloons.

Interceptors

The Defence Committee expressed some doubt as to the ability of theRoyal Observer Corps

The Royal Observer Corps (ROC) was a civil defence organisation intended for the visual detection, identification, tracking and reporting of aircraft over Great Britain. It operated in the United Kingdom between 29 October 1925 and 31 Decembe ...

to adequately deal with the new threat, but the ROC's Commandant Air Commodore Finlay Crerar assured the committee that the ROC could again rise to the occasion and prove its alertness and flexibility. He oversaw plans for handling the new threat, codenamed by the RAF and ROC as "Operation Totter".

Observers at the coast post of Dymchurch

Dymchurch is a village and civil parish in the Folkestone and Hythe district of Kent, England. The village is located on the coast five miles (8 km) south-west of Hythe, and on the Romney Marsh.

History

The history of Dymchurch began w ...

identified the very first of these weapons and within seconds of their report the anti-aircraft defences were in action. This new weapon gave the ROC much additional work both at posts and operations rooms. Eventually RAF controllers actually took their radio equipment to the two closest ROC operations rooms at Horsham and Maidstone, and vectored fighters direct from the ROC's plotting tables. The critics who had said that the Corps would be unable to handle the fast-flying jet aircraft were answered when these aircraft on their first operation were actually controlled entirely by using ROC information both on the coast and at inland.

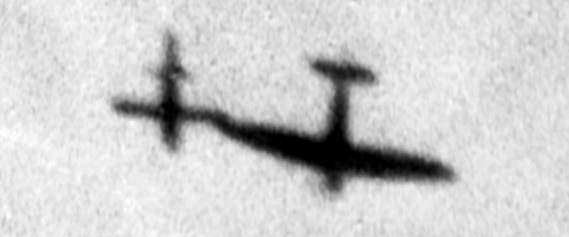

The average speed of V-1s was and their average altitude was to . Fighter aircraft required excellent low altitude performance to intercept them and enough firepower to ensure that they were destroyed in the air (ideally, also from a sufficient distance, to avoid being damaged by the strong blast) rather than the V-1 crashing to earth and detonating. Most aircraft were too slow to catch a V-1 unless they had a height advantage, allowing them to gain speed by diving on their target.

When V-1 attacks began in mid-June 1944, the only aircraft with the low-altitude speed to be effective against it was the Hawker Tempest

The Hawker Tempest is a British fighter aircraft that was primarily used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the Second World War. The Tempest, originally known as the ''Typhoon II'', was an improved derivative of the Hawker Typhoon, intended to a ...

. Fewer than 30 Tempests were available. They were assigned to No. 150 Wing RAF. Early attempts to intercept and destroy V-1s often failed, but improved techniques soon emerged. These included using the airflow over an interceptor's wing to raise one wing of the V-1, by sliding the wingtip to within of the lower surface of the V-1's wing. If properly executed, this manoeuvre would tip the V-1's wing up, over-riding the gyro

Gyro may refer to:

Science and technology

* GYRO, a computer program for tokamak plasma simulation

* Gyro Motor Company, an American aircraft engine manufacturer

* ''Gyrodactylus salaris'', a parasite in salmon

* Gyroscope, an orientation-sta ...

and sending the V-1 into an out-of-control dive. At least sixteen V-1s were destroyed this way (the first by a P-51 piloted by Major R. E. Turner of 356th Fighter Squadron on 18 June).

The Tempest fleet was built up to over 100 aircraft by September, and during the short summer nights the Tempests shared defensive duty with twin-engined de Havilland Mosquito

The de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito is a British twin-engined, shoulder-winged, multirole combat aircraft, introduced during the World War II, Second World War. Unusual in that its frame was constructed mostly of wood, it was nicknamed the "Wooden ...

s. Specially modified Republic P-47M Thunderbolts were also pressed into service against the V-1s; they had boosted engines () and had half their .50 calibre (12.5 mm) machine guns and half their fuel tanks, all external fittings and all their armour plate removed to reduce weight. In addition, North American P-51 Mustang

The North American Aviation P-51 Mustang is an American long-range, single-seat fighter and fighter-bomber used during World War II and the Korean War, among other conflicts. The Mustang was designed in April 1940 by a team headed by James ...

s and Griffon-engined Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allies of World War II, Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 ...

Mk XIVs were tuned to make them fast enough, At night airborne radar was not needed, as the V-1 engine could be heard from away or more and the exhaust plume was visible from a long distance. Wing Commander

Wing commander (Wg Cdr in the RAF, the IAF, and the PAF, WGCDR in the RNZAF and RAAF, formerly sometimes W/C in all services) is a senior commissioned rank in the British Royal Air Force and air forces of many countries which have historic ...

Roland Beamont

Wing Commander Roland Prosper "Bee" Beamont, (10 August 1920 – 19 November 2001) was a British fighter pilot for the Royal Air Force (RAF) and an experimental test pilot during and after the Second World War. He was the first British pilot to e ...

had the 20 mm cannon on his Tempest adjusted to converge at ahead. This was so successful that all other aircraft in 150 Wing were thus modified.

The anti-V-1 sorties by fighters were known as "Diver patrols" (after "Diver", the codename used by the Royal Observer Corps

The Royal Observer Corps (ROC) was a civil defence organisation intended for the visual detection, identification, tracking and reporting of aircraft over Great Britain. It operated in the United Kingdom between 29 October 1925 and 31 Decembe ...

for V-1 sightings). Attacking a V-1 was dangerous: machine guns had little effect on the V-1's sheet steel structure, and if a cannon shell detonated the warhead, the explosion could destroy the attacker.

In daylight, V-1 chases were chaotic and often unsuccessful until a special defence zone was declared between London and the coast, in which only the fastest fighters were permitted. The first interception of a V-1 was by F/L J. G. Musgrave with a No. 605 Squadron RAF Mosquito night fighter on the night of 14/15 June 1944. As daylight grew stronger after the night attack, a Spitfire was seen to follow closely behind a V-1 over Chislehurst and Lewisham. Between June and 5 September 1944, a handful of 150 Wing Tempests shot down 638 flying bombs, with No. 3 Squadron RAF alone claiming 305. One Tempest pilot, Squadron Leader Joseph Berry ( 501 Squadron), shot down 59 V-1s, the Belgian ace Squadron Leader

In daylight, V-1 chases were chaotic and often unsuccessful until a special defence zone was declared between London and the coast, in which only the fastest fighters were permitted. The first interception of a V-1 was by F/L J. G. Musgrave with a No. 605 Squadron RAF Mosquito night fighter on the night of 14/15 June 1944. As daylight grew stronger after the night attack, a Spitfire was seen to follow closely behind a V-1 over Chislehurst and Lewisham. Between June and 5 September 1944, a handful of 150 Wing Tempests shot down 638 flying bombs, with No. 3 Squadron RAF alone claiming 305. One Tempest pilot, Squadron Leader Joseph Berry ( 501 Squadron), shot down 59 V-1s, the Belgian ace Squadron Leader Remy Van Lierde

Colonel Remy Van Lierde, (14 August 1915 – 8 June 1990) was a Belgian pilot and fighter ace who served in the aviation branch of the Belgian Army and the British Royal Air Force (RAF) during the Second World War, shooting down six enemy ...

( 164 Squadron) destroyed 44 (with a further nine shared), W/C Roland Beamont destroyed 31, and F/Lt Arthur Umbers (No. 3 squadron) destroyed 28. A Dutch pilot in 322 Squadron, Jan Leendert Plesman, son of KLM president Albert Plesman

Albert Plesman (7 September 1889 – 31 December 1953) was a Dutch pioneer in aviation and the first administrator and later director of the KLM, the oldest airline in the world still operating under its original name.

Until his death, he was in ...

, managed to destroy 12 in 1944, flying a Spitfire.

The next most successful interceptors were the Mosquito (623 victories), Spitfire XIV (303), and Mustang (232). All other types combined added 158. Even though it was not fully operational, the jet-powered Gloster Meteor

The Gloster Meteor was the first British jet fighter and the Allies' only jet aircraft to engage in combat operations during the Second World War. The Meteor's development was heavily reliant on its ground-breaking turbojet engines, pioneere ...

was rushed into service with No. 616 Squadron RAF to fight the V-1s. It had ample speed but its cannons were prone to jamming, and it shot down only 13 V-1s.

In late 1944 a radar-equipped Vickers Wellington

The Vickers Wellington was a British twin-engined, long-range medium bomber. It was designed during the mid-1930s at Brooklands in Weybridge, Surrey. Led by Vickers-Armstrongs' chief designer Rex Pierson; a key feature of the aircraft is it ...

bomber was modified for use by the RAF's Fighter Interception Unit as an airborne early warning and control

Airborne or Airborn may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

* ''Airborne'' (1962 film), a 1962 American film directed by James Landis

* ''Airborne'' (1993 film), a comedy–drama film

* ''Airborne'' (1998 film), an action film sta ...

aircraft. Flying at an altitude of over the North Sea at night, it directed Mosquito and Beaufighters charged with intercepting He 111s from Dutch airbases that sought to launch V-1s from the air.

Disposal

The firstbomb disposal

Bomb disposal is an explosives engineering profession using the process by which hazardous explosive devices are rendered safe. ''Bomb disposal'' is an all-encompassing term to describe the separate, but interrelated functions in the militar ...

officer to defuse an unexploded V-1 was John Pilkington Hudson

John Pilkington Hudson, (24 July 1910 – 6 December 2007) was an English horticultural scientist who did pioneer work on long-distance transportability of what became known as the kiwifruit. He was also a celebrated bomb disposal expert.

Back ...

in 1944.

Deception

To adjust and correct settings in the V-1 guidance system, the Germans needed to know where the V-1s were impacting. Therefore, German intelligence was requested to obtain this impact data from their agents in Britain. However, all German agents in Britain had been turned, and were acting as double agents under British control. On 16 June 1944, British double agent ''Garbo'' ( Juan Pujol) was requested by his German controllers to give information on the sites and times of V-1 impacts, with similar requests made to the other German agents in Britain, ''Brutus'' ( Roman Czerniawski) and ''Tate'' (

On 16 June 1944, British double agent ''Garbo'' ( Juan Pujol) was requested by his German controllers to give information on the sites and times of V-1 impacts, with similar requests made to the other German agents in Britain, ''Brutus'' ( Roman Czerniawski) and ''Tate'' (Wulf Schmidt

Wulf Dietrich Christian Schmidt, later known as Harry Williamson (7 December 1911 – 19 October 1992) was a Danish citizen who became a double agent working for Britain against Nazi Germany during the Second World War under the codename Tate. H ...

). If given this data, the Germans would be able to adjust their aim and correct any shortfall. However, there was no plausible reason why the double agents could not supply accurate data; the impacts would be common knowledge amongst Londoners and very likely reported in the press, which the Germans had ready access to through the neutral nations. In addition, as John Cecil Masterman

Sir John Cecil Masterman OBE (12 January 1891 – 6 June 1977) was a noted academic, sportsman and author. His highest-profile role was as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford, but he was also well known as chairman of the Twenty Com ...

, chairman of the Twenty Committee, commented, "If, for example, St Paul's Cathedral were hit, it was useless and harmful to report that the bomb had descended upon a cinema in Islington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ...

, since the truth would inevitably get through to Germany ..."

While the British decided how to react, Pujol played for time. On 18 June it was decided that the double agents would report the damage caused by V-1s fairly accurately and minimise the effect they had on civilian morale. It was also decided that Pujol should avoid giving the times of impacts, and should mostly report on those which occurred in the north west of London, to give the impression to the Germans that they were overshooting the target area.

While Pujol downplayed the extent of V-1 damage, trouble came from ''Ostro'', an agent in Lisbon who pretended to have agents reporting from London. He told the Germans that London had been devastated and had been mostly evacuated as a result of enormous casualties. The Germans could not perform aerial reconnaissance of London, and believed his damage reports in preference to Pujol's. They thought that the Allies would make every effort to destroy the V-1 launch sites in France. They also accepted ''Ostro''s impact reports. Due to Ultra

adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park ...

, however, the Allies read his messages and adjusted for them.

A certain number of the V-1s fired had been fitted with radio transmitters, which had clearly demonstrated a tendency for the V-1 to fall short. Max Wachtel, commander of Flak Regiment 155 (W), which was responsible for the V-1 offensive, compared the data gathered by the transmitters with the reports obtained through the double agents. He concluded, when faced with the discrepancy between the two sets of data, that there must be a fault with the radio transmitters, as he had been assured that the agents were completely reliable. It was later calculated that if Wachtel had disregarded the agents' reports and relied on the radio data, he would have made the correct adjustments to the V-1's guidance, and casualties might have increased by 50 percent or more.

The policy of diverting V-1 impacts away from central London was initially controversial. The War Cabinet refused to authorise a measure that would increase casualties in any area, even if it reduced casualties elsewhere by greater amounts. It was thought that