Upper Mantle (Earth) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The upper mantle of Earth is a very thick layer of rock inside the planet, which begins just beneath the crust (at about under the oceans and about under the continents) and ends at the top of the lower mantle at . Temperatures range from approximately at the upper boundary with the crust to approximately at the boundary with the lower mantle. Upper mantle material that has come up onto the surface comprises about 55% olivine, 35%

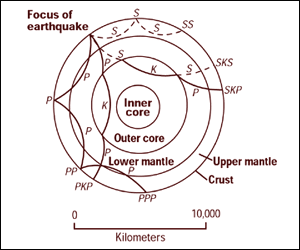

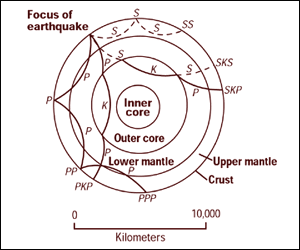

The density profile through Earth is determined by the velocity of seismic waves. Density increases progressively in each layer, largely due to compression of the rock at increased depths. Abrupt changes in density occur where the material composition changes.

The upper mantle begins just beneath the crust and ends at the top of the lower mantle. The upper mantle causes the tectonic plates to move.

Crust and

The density profile through Earth is determined by the velocity of seismic waves. Density increases progressively in each layer, largely due to compression of the rock at increased depths. Abrupt changes in density occur where the material composition changes.

The upper mantle begins just beneath the crust and ends at the top of the lower mantle. The upper mantle causes the tectonic plates to move.

Crust and  The boundary between the upper and lower mantle is a discontinuity. Earthquakes at shallow depths result from strike-slip faulting; however, below about , the hot, high-pressure conditions inhibit further seismicity. The mantle is viscous and incapable of faulting. However, in

The boundary between the upper and lower mantle is a discontinuity. Earthquakes at shallow depths result from strike-slip faulting; however, below about , the hot, high-pressure conditions inhibit further seismicity. The mantle is viscous and incapable of faulting. However, in

Exploration of the mantle is generally conducted at the seabed rather than on land because of the oceanic crust's relative thinness as compared to the significantly thicker continental crust.

The first attempt at mantle exploration, known as Project Mohole, was abandoned in 1966 after repeated failures and cost overruns. The deepest penetration was approximately . In 2005 an oceanic borehole reached below the seafloor from the ocean drilling vessel '' JOIDES Resolution''.

On 5 March 2007, a team of scientists on board the RRS ''James Cook'' embarked on a voyage to an area of the Atlantic seafloor where the mantle lies exposed without any crust covering, midway between the Cape Verde Islands and the Caribbean Sea. The exposed site lies approximately beneath the ocean surface and covers thousands of square kilometers.

The Chikyu Hakken mission attempted to use the Japanese vessel '' Chikyū'' to drill up to below the seabed. On 27 April 2012, ''Chikyū'' drilled to a depth of below sea level, setting a new world record for deep-sea drilling. This record has since been surpassed by the ill-fated '' Deepwater Horizon'' mobile offshore drilling unit, operating on the Tiber prospect in the Mississippi Canyon Field, United States Gulf of Mexico, when it achieved a world record for total length for a vertical drilling string of 10,062 m (33,011 ft). The previous record was held by the U.S. vessel '' Glomar Challenger'', which in 1978 drilled to 7,049.5 meters (23,130 feet) below sea level in the Mariana Trench. On 6 September 2012, Scientific deep-sea drilling vessel ''Chikyū'' set a new world record by drilling down and obtaining rock samples from deeper than below the seafloor off the Shimokita Peninsula of Japan in the northwest Pacific Ocean.

A novel method of exploring the uppermost few hundred kilometers of the Earth was proposed in 2005, consisting of a small, dense, heat-generating probe that melts its way down through the crust and mantle while its position and progress are tracked by acoustic signals generated in the rocks. The probe consists of an outer sphere of tungsten about in diameter with a cobalt-60 interior acting as a radioactive heat source. This should take half a year to reach the oceanic Moho.Ojovan M.I., Gibb F.G.F. "Exploring the Earth’s Crust and Mantle Using Self-Descending, Radiation-Heated, Probes and Acoustic Emission Monitoring". Chapter 7. In: ''Nuclear Waste Research: Siting, Technology and Treatment'', , Editor: Arnold P. Lattefer, Nova Science Publishers, Inc. 2008

Exploration can also be aided through computer simulations of the evolution of the mantle. In 2009, a

Exploration of the mantle is generally conducted at the seabed rather than on land because of the oceanic crust's relative thinness as compared to the significantly thicker continental crust.

The first attempt at mantle exploration, known as Project Mohole, was abandoned in 1966 after repeated failures and cost overruns. The deepest penetration was approximately . In 2005 an oceanic borehole reached below the seafloor from the ocean drilling vessel '' JOIDES Resolution''.

On 5 March 2007, a team of scientists on board the RRS ''James Cook'' embarked on a voyage to an area of the Atlantic seafloor where the mantle lies exposed without any crust covering, midway between the Cape Verde Islands and the Caribbean Sea. The exposed site lies approximately beneath the ocean surface and covers thousands of square kilometers.

The Chikyu Hakken mission attempted to use the Japanese vessel '' Chikyū'' to drill up to below the seabed. On 27 April 2012, ''Chikyū'' drilled to a depth of below sea level, setting a new world record for deep-sea drilling. This record has since been surpassed by the ill-fated '' Deepwater Horizon'' mobile offshore drilling unit, operating on the Tiber prospect in the Mississippi Canyon Field, United States Gulf of Mexico, when it achieved a world record for total length for a vertical drilling string of 10,062 m (33,011 ft). The previous record was held by the U.S. vessel '' Glomar Challenger'', which in 1978 drilled to 7,049.5 meters (23,130 feet) below sea level in the Mariana Trench. On 6 September 2012, Scientific deep-sea drilling vessel ''Chikyū'' set a new world record by drilling down and obtaining rock samples from deeper than below the seafloor off the Shimokita Peninsula of Japan in the northwest Pacific Ocean.

A novel method of exploring the uppermost few hundred kilometers of the Earth was proposed in 2005, consisting of a small, dense, heat-generating probe that melts its way down through the crust and mantle while its position and progress are tracked by acoustic signals generated in the rocks. The probe consists of an outer sphere of tungsten about in diameter with a cobalt-60 interior acting as a radioactive heat source. This should take half a year to reach the oceanic Moho.Ojovan M.I., Gibb F.G.F. "Exploring the Earth’s Crust and Mantle Using Self-Descending, Radiation-Heated, Probes and Acoustic Emission Monitoring". Chapter 7. In: ''Nuclear Waste Research: Siting, Technology and Treatment'', , Editor: Arnold P. Lattefer, Nova Science Publishers, Inc. 2008

Exploration can also be aided through computer simulations of the evolution of the mantle. In 2009, a

Super-computer Provides First Glimpse Of Earth's Early Magma Interior

pyroxene

The pyroxenes (commonly abbreviated to ''Px'') are a group of important rock-forming inosilicate minerals found in many igneous and metamorphic rocks. Pyroxenes have the general formula , where X represents calcium (Ca), sodium (Na), iron (Fe II) ...

, and 5 to 10% of calcium oxide and aluminum oxide minerals such as plagioclase, spinel

Spinel () is the magnesium/aluminium member of the larger spinel group of minerals. It has the formula in the cubic crystal system. Its name comes from the Latin word , which means ''spine'' in reference to its pointed crystals.

Properties

S ...

, or garnet, depending upon depth.

Seismic structure

The density profile through Earth is determined by the velocity of seismic waves. Density increases progressively in each layer, largely due to compression of the rock at increased depths. Abrupt changes in density occur where the material composition changes.

The upper mantle begins just beneath the crust and ends at the top of the lower mantle. The upper mantle causes the tectonic plates to move.

Crust and

The density profile through Earth is determined by the velocity of seismic waves. Density increases progressively in each layer, largely due to compression of the rock at increased depths. Abrupt changes in density occur where the material composition changes.

The upper mantle begins just beneath the crust and ends at the top of the lower mantle. The upper mantle causes the tectonic plates to move.

Crust and mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

are distinguished by composition, while the lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust (geology), crust and the portion of the upper mantle (geology), mantle that behaves elastically on time sca ...

and asthenosphere

The asthenosphere () is the mechanically weak and ductile region of the upper mantle of Earth. It lies below the lithosphere, at a depth between ~ below the surface, and extends as deep as . However, the lower boundary of the asthenosphere is not ...

are defined by a change in mechanical properties.

The top of the mantle is defined by a sudden increase in the speed of seismic waves, which Andrija Mohorovičić first noted in 1909; this boundary is now referred to as the Mohorovičić discontinuity

The Mohorovičić discontinuity ( , ), usually referred to as the Moho discontinuity or the Moho, is the boundary between the Earth's crust and the mantle. It is defined by the distinct change in velocity of seismic waves as they pass through ch ...

or "Moho."

The Moho defines the base of the crust and varies from to below the surface of the Earth. Oceanic crust is thinner than continental crust and is generally less than thick. Continental crust is about thick, but the large crustal root under the Tibetan Plateau is approximately thick.

The thickness of the upper mantle is about . The entire mantle is about thick, which means the upper mantle is only about 20% of the total mantle thickness.

The boundary between the upper and lower mantle is a discontinuity. Earthquakes at shallow depths result from strike-slip faulting; however, below about , the hot, high-pressure conditions inhibit further seismicity. The mantle is viscous and incapable of faulting. However, in

The boundary between the upper and lower mantle is a discontinuity. Earthquakes at shallow depths result from strike-slip faulting; however, below about , the hot, high-pressure conditions inhibit further seismicity. The mantle is viscous and incapable of faulting. However, in subduction zones

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

, earthquakes are observed down to .

Lehmann discontinuity

The Lehmann discontinuity is an abrupt increase of ''P''-wave and ''S''-wave velocities at a depth of (Note that this is a different "Lehmann discontinuity" than the one between the Earth's inner and outer cores labeled in the image on the right.)Transition zone

The transition zone is located between the upper mantle and the lower mantle between a depth of and . This is thought to occur as a result of the rearrangement of grains in olivine to form a denser crystal structure as a result of the increase in pressure with increasing depth. Below a depth of , due to pressure changes, ringwoodite minerals change into two new denser phases, bridgmanite and periclase. This can be seen using body waves from earthquakes, which are converted, reflected, or refracted at the boundary, and predicted from mineral physics, as the phase changes are temperature and density-dependent and hence depth-dependent.410 km discontinuity

A single peak is seen in all seismological data at , which is predicted by the single transition from α- to β- Mg2SiO4 (olivine to wadsleyite). From the Clapeyron slope this discontinuity is expected to be shallower in cold regions, such as subducting slabs, and deeper in warmer regions, such as mantle plumes.670 km discontinuity

This is the most complex discontinuity and marks the boundary between the upper and lower mantle. It appears in PP precursors (a wave that reflects off the discontinuity once) only in certain regions but is always apparent in SS precursors. It is seen as single and double reflections in receiver functions for P to S conversions over a broad range of depths (640–720 km, or 397–447 mi). The Clapeyron slope predicts a deeper discontinuity in colder regions and a shallower discontinuity in hotter regions. This discontinuity is generally linked to the transition from ringwoodite to bridgmanite and periclase. This is thermodynamically an endothermic reaction and creates a viscosity jump. Both characteristics cause this phase transition to playing an important role in geodynamical models.Other discontinuities

There is another major phase transition predicted at for the transition of olivine (β to γ) and garnet in the pyrolite mantle. This one has only sporadically been observed in seismological data. Other non-global phase transitions have been suggested at a range of depths.Temperature and pressure

Temperatures range from approximately at the upper boundary with the crust to approximately at the core-mantle boundary. The highest temperature of the upper mantle is . Although the high temperature far exceeds the melting points of the mantle rocks at the surface, the mantle is almost exclusively solid. The enormous lithostatic pressure exerted on the mantle prevents melting because the temperature at which melting begins (the solidus) increases with pressure. Pressure increases as depth increases since the material beneath has to support the weight of all the material above it. The entire mantle is thought to deform like a fluid on long timescales, with permanent plastic deformation. The highest pressure of the upper mantle is compared to the bottom of the mantle, which is . Estimates for the viscosity of the upper mantle range between 1019 and 1024Pa·s

The viscosity of a fluid is a measure of its resistance to deformation at a given rate. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of "thickness": for example, syrup has a higher viscosity than water.

Viscosity quantifies the inte ...

, depending on depth, temperature, composition, state of stress, and numerous other factors. The upper mantle can only flow very slowly. However, when large forces are applied to the uppermost mantle, it can become weaker, and this effect is thought to be important in allowing the formation of tectonic plate boundaries.

Although there is a tendency to larger viscosity at greater depth, this relation is far from linear and shows layers with dramatically decreased viscosity, in particular in the upper mantle and at the boundary with the core.

Movement

Because of the temperature difference between the Earth's surface and outer core and the ability of the crystalline rocks at high pressure and temperature to undergo slow, creeping, viscous-like deformation over millions of years, there is a convective material circulation in the mantle. Hot material upwells, while cooler (and heavier) material sinks downward. Downward motion of material occurs at convergent plate boundaries calledsubduction zones

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

. Locations on the surface that lie over plumes are predicted to have high elevation (because of the buoyancy of the hotter, less-dense plume beneath) and to exhibit hot spot

Hotspot, Hot Spot or Hot spot may refer to:

Places

* Hot Spot, Kentucky, a community in the United States

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

* Hot Spot (comics), a name for the DC Comics character Isaiah Crockett

* Hot Spot (Tra ...

volcanism.

Mineral composition

The seismic data is not sufficient to determine the composition of the mantle. Observations of rocks exposed on the surface and other evidence reveal that the upper mantle is mafic minerals olivine and pyroxene, and it has a density of about Upper mantle material that has come up onto the surface comprises about 55% olivine and 35% pyroxene, and 5 to 10% of calcium oxide and aluminum oxide. The upper mantle is dominantlyperidotite

Peridotite ( ) is a dense, coarse-grained igneous rock consisting mostly of the silicate minerals olivine and pyroxene. Peridotite is ultramafic, as the rock contains less than 45% silica. It is high in magnesium (Mg2+), reflecting the high prop ...

, composed primarily of variable proportions of the minerals olivine, clinopyroxene, orthopyroxene

The pyroxenes (commonly abbreviated to ''Px'') are a group of important rock-forming inosilicate minerals found in many igneous and metamorphic rocks. Pyroxenes have the general formula , where X represents calcium (Ca), sodium (Na), iron (Fe II) ...

, and an aluminous phase. The aluminous phase is plagioclase in the uppermost mantle, then spinel, and then garnet below about . Gradually through the upper mantle, pyroxenes become less stable and transform into majoritic garnet.

Experiments on olivines and pyroxenes show that these minerals change the structure as pressure increases at greater depth, which explains why the density curves are not perfectly smooth. When there is a conversion to a more dense mineral structure, the seismic velocity rises abruptly and creates a discontinuity.

At the top of the transition zone, olivine undergoes isochemical phase transitions to wadsleyite and ringwoodite. Unlike nominally anhydrous olivine, these high-pressure olivine polymorphs have a large capacity to store water in their crystal structure. This has led to the hypothesis that the transition zone may host a large quantity of water.

In Earth's interior, olivine occurs in the upper mantle at depths less than , and ringwoodite is inferred within the transition zone from about depth. Seismic activity discontinuities at about , , and depth have been attributed to phase changes involving olivine and its polymorph

Polymorphism, polymorphic, polymorph, polymorphous, or polymorphy may refer to:

Computing

* Polymorphism (computer science), the ability in programming to present the same programming interface for differing underlying forms

* Ad hoc polymorphi ...

s.

At the base of the transition zone, ringwoodite decomposes into bridgmanite (formerly called magnesium silicate perovskite), and ferropericlase. Garnet also becomes unstable at or slightly below the base of the transition zone.

Kimberlites explode from the earth's interior and sometimes carry rock fragments. Some of these xenolithic fragments are diamonds that can only come from the higher pressures below the crust. The rocks that come with this are ultramafic nodules and peridotite.

Chemical composition

The composition seems to be very similar to the crust. One difference is that rocks and minerals of the mantle tend to have more magnesium and less silicon and aluminum than the crust. The first four most abundant elements in the upper mantle are oxygen, magnesium, silicon, and iron.Exploration

Exploration of the mantle is generally conducted at the seabed rather than on land because of the oceanic crust's relative thinness as compared to the significantly thicker continental crust.

The first attempt at mantle exploration, known as Project Mohole, was abandoned in 1966 after repeated failures and cost overruns. The deepest penetration was approximately . In 2005 an oceanic borehole reached below the seafloor from the ocean drilling vessel '' JOIDES Resolution''.

On 5 March 2007, a team of scientists on board the RRS ''James Cook'' embarked on a voyage to an area of the Atlantic seafloor where the mantle lies exposed without any crust covering, midway between the Cape Verde Islands and the Caribbean Sea. The exposed site lies approximately beneath the ocean surface and covers thousands of square kilometers.

The Chikyu Hakken mission attempted to use the Japanese vessel '' Chikyū'' to drill up to below the seabed. On 27 April 2012, ''Chikyū'' drilled to a depth of below sea level, setting a new world record for deep-sea drilling. This record has since been surpassed by the ill-fated '' Deepwater Horizon'' mobile offshore drilling unit, operating on the Tiber prospect in the Mississippi Canyon Field, United States Gulf of Mexico, when it achieved a world record for total length for a vertical drilling string of 10,062 m (33,011 ft). The previous record was held by the U.S. vessel '' Glomar Challenger'', which in 1978 drilled to 7,049.5 meters (23,130 feet) below sea level in the Mariana Trench. On 6 September 2012, Scientific deep-sea drilling vessel ''Chikyū'' set a new world record by drilling down and obtaining rock samples from deeper than below the seafloor off the Shimokita Peninsula of Japan in the northwest Pacific Ocean.

A novel method of exploring the uppermost few hundred kilometers of the Earth was proposed in 2005, consisting of a small, dense, heat-generating probe that melts its way down through the crust and mantle while its position and progress are tracked by acoustic signals generated in the rocks. The probe consists of an outer sphere of tungsten about in diameter with a cobalt-60 interior acting as a radioactive heat source. This should take half a year to reach the oceanic Moho.Ojovan M.I., Gibb F.G.F. "Exploring the Earth’s Crust and Mantle Using Self-Descending, Radiation-Heated, Probes and Acoustic Emission Monitoring". Chapter 7. In: ''Nuclear Waste Research: Siting, Technology and Treatment'', , Editor: Arnold P. Lattefer, Nova Science Publishers, Inc. 2008

Exploration can also be aided through computer simulations of the evolution of the mantle. In 2009, a

Exploration of the mantle is generally conducted at the seabed rather than on land because of the oceanic crust's relative thinness as compared to the significantly thicker continental crust.

The first attempt at mantle exploration, known as Project Mohole, was abandoned in 1966 after repeated failures and cost overruns. The deepest penetration was approximately . In 2005 an oceanic borehole reached below the seafloor from the ocean drilling vessel '' JOIDES Resolution''.

On 5 March 2007, a team of scientists on board the RRS ''James Cook'' embarked on a voyage to an area of the Atlantic seafloor where the mantle lies exposed without any crust covering, midway between the Cape Verde Islands and the Caribbean Sea. The exposed site lies approximately beneath the ocean surface and covers thousands of square kilometers.

The Chikyu Hakken mission attempted to use the Japanese vessel '' Chikyū'' to drill up to below the seabed. On 27 April 2012, ''Chikyū'' drilled to a depth of below sea level, setting a new world record for deep-sea drilling. This record has since been surpassed by the ill-fated '' Deepwater Horizon'' mobile offshore drilling unit, operating on the Tiber prospect in the Mississippi Canyon Field, United States Gulf of Mexico, when it achieved a world record for total length for a vertical drilling string of 10,062 m (33,011 ft). The previous record was held by the U.S. vessel '' Glomar Challenger'', which in 1978 drilled to 7,049.5 meters (23,130 feet) below sea level in the Mariana Trench. On 6 September 2012, Scientific deep-sea drilling vessel ''Chikyū'' set a new world record by drilling down and obtaining rock samples from deeper than below the seafloor off the Shimokita Peninsula of Japan in the northwest Pacific Ocean.

A novel method of exploring the uppermost few hundred kilometers of the Earth was proposed in 2005, consisting of a small, dense, heat-generating probe that melts its way down through the crust and mantle while its position and progress are tracked by acoustic signals generated in the rocks. The probe consists of an outer sphere of tungsten about in diameter with a cobalt-60 interior acting as a radioactive heat source. This should take half a year to reach the oceanic Moho.Ojovan M.I., Gibb F.G.F. "Exploring the Earth’s Crust and Mantle Using Self-Descending, Radiation-Heated, Probes and Acoustic Emission Monitoring". Chapter 7. In: ''Nuclear Waste Research: Siting, Technology and Treatment'', , Editor: Arnold P. Lattefer, Nova Science Publishers, Inc. 2008

Exploration can also be aided through computer simulations of the evolution of the mantle. In 2009, a supercomputer

A supercomputer is a computer with a high level of performance as compared to a general-purpose computer. The performance of a supercomputer is commonly measured in floating-point operations per second ( FLOPS) instead of million instructions ...

application provided new insight into the distribution of mineral deposits, especially isotopes of iron, from when the mantle developed 4.5 billion years ago.University of California – Davis (2009-06-15)Super-computer Provides First Glimpse Of Earth's Early Magma Interior

ScienceDaily

''Science Daily'' is an American website launched in 1995 that aggregates press releases and publishes lightly edited press releases (a practice called churnalism) about science, similar to Phys.org and EurekAlert!.

The site was founded by mar ...

. Retrieved on 2009-06-16.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Upper Mantle Earth's mantle