U.S. theater on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Theater in the United States is part of the old European theatrical tradition and has been heavily influenced by the British theater. The central hub of the American theater scene is

Before the first English colony was established in 1607, there were Spanish dramas and Native American tribes that performed theatrical events. Representations continued to be held in Spanish-held territories in what later became the United States. For example, at the Presidio of

Before the first English colony was established in 1607, there were Spanish dramas and Native American tribes that performed theatrical events. Representations continued to be held in Spanish-held territories in what later became the United States. For example, at the Presidio of

During

During

After World War II, American theater came into its own. Several American playwrights, such as

After World War II, American theater came into its own. Several American playwrights, such as

During the period between the World Wars, American drama came to maturity, thanks in large part to the works of

During the period between the World Wars, American drama came to maturity, thanks in large part to the works of  The stature that American drama had achieved between the Wars was cemented during the post-World War II generation, with the final works of O'Neill and his generation being joined by such towering figures as

The stature that American drama had achieved between the Wars was cemented during the post-World War II generation, with the final works of O'Neill and his generation being joined by such towering figures as

Although earlier styles of theater such as

Although earlier styles of theater such as

online

* Brockett, Oscar G., and Robert R. Findlay. "Century of Innovation: A History of European and American Theatre and Drama Since 1870." (1973)

online

* Brown, Gene. ''Show time: a chronology of Broadway and the theatre from its beginnings to the present'' (1997

online

* Burke, Sally. ''American Feminist Playwrights'' (1996

online

* Fisher, James. ed. ''Historical Dictionary of Contemporary American Theater: 1930-2010'' (2 vol. 2011) * Krasner, David. ''American Drama 1945 – 2000: An Introduction'' (2006) * Krasner, David. ''A beautiful pageant : African American theatre, drama, and performance in the Harlem Renaissance, 1910-1927'' (2002

online

* Krutch, Joseph Wood. ''The American drama since 1918 : an informal history'' (1939

online

* McGovern, Dennis. ''Sing out, Louise! : 150 stars of the musical theatre remember 50 years on Broadway'' (1993) based on interviews

online

* Mathews, Jane DeHart. ''Federal Theatre, 1935-1939: Plays, Relief, and Politics'' (Princeton UP 1967

online

* Miller, Jordan Yale and Winifred L. Frazer. ''American Drama between the Wars'' (1991

online

* Palmer, David, ed. ''Visions of Tragedy in Modern American Drama'' (Bloomsbury, 2018). * Richardson, Gary A. ''American Drama through World War I'' (1997

online

* Roudane, Matthew C. ''American Drama Since 1960: A Critical History'' (1996

online

* Shiach, Don. ''American Drama 1900–1990'' (2000) * Vacha, John. ''From Broadway to Cleveland : a history of the Hanna Theatre'' (2007) in Cleveland. Ohi

online

* Watt, Stephen, and Gary A. Richardson. ''American Drama: Colonial to Contemporary'' (1994) * Weales, Gerald Clifford. ''American drama since World War II'' (1962)

538 photographs of American theater people, buildings, and scenes; these are pre-1923 and out of copyright.

{{United States topics Theater Theater

Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

, with its divisions of Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

, Off-Broadway

An off-Broadway theatre is any professional theatre venue in New York City with a seating capacity between 100 and 499, inclusive. These theatres are smaller than Broadway theatres, but larger than off-off-Broadway theatres, which seat fewer tha ...

, and Off-Off-Broadway

Off-off-Broadway theaters are smaller New York City theaters than Broadway and off-Broadway theaters, and usually have fewer than 100 seats. The off-off-Broadway movement began in 1958 as part of a response to perceived commercialism of the prof ...

. Many movie and television stars have gotten their big break working in New York productions. Outside New York, many cities have professional regional or resident theater companies that produce their own seasons, with some works being produced regionally with hopes of eventually moving to New York. U.S. theater also has an active community theater Community theatre refers to any theatrical performance made in relation to particular communities—its usage includes theatre made by, with, and for a community. It may refer to a production that is made entirely by a community with no outside hel ...

culture, which relies mainly on local volunteers who may not be actively pursuing a theatrical career.

Early history

Before the first English colony was established in 1607, there were Spanish dramas and Native American tribes that performed theatrical events. Representations continued to be held in Spanish-held territories in what later became the United States. For example, at the Presidio of

Before the first English colony was established in 1607, there were Spanish dramas and Native American tribes that performed theatrical events. Representations continued to be held in Spanish-held territories in what later became the United States. For example, at the Presidio of Los Adaes

Los Adaes was the capital of Tejas on the northeastern frontier of New Spain from 1729 to 1770. It included a mission, San Miguel de Cuellar de los Adaes, and a presidio, Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Los Adaes (Our Lady of the Pillar of the Adae ...

in the New Philippines

The New Philippines ( es, Nuevas Filipinas or ) was the abbreviated name of a territory in New Spain. Its full and official name was .

The territory was named in honor of its sovereign, King Philip V of Spain. The ultimate demise of the New Phi ...

(now in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

), several plays were presented on October 12, 1721.

Although a theater was built in Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it had a population of 15,425. Located on the Virginia Peninsula ...

in 1716, and the original Dock Street Theatre

The Dock Street Theatre is a theater in the historic French Quarter neighborhood of downtown Charleston, South Carolina.

History

The structure, which was built as a hotel in 1809 and converted to a theater in 1935, occupies the site of the first ...

opened in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

in 1736, the birth of professional theater in the English colonies may have begun when Lewis Hallam

Lewis Hallam (circa 1714–1756) was an English-born actor and theatre director in the colonial United States.

Career

Hallam is thought to have been born in about 1714 and possibly in Dublin. His father Thomas Hallam was also an actor who was ...

arrived with his theatrical company in Williamsburg in 1752. Lewis and his brother William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

, who arrived in 1754, were the first to organize a complete company of actors in Europe and bring them to the colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

. They brought a repertoire of plays popular in London at the time, including ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'', ''Othello

''Othello'' (full title: ''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'') is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare, probably in 1603, set in the contemporary Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573) fought for the control of the Island of Cypru ...

'', ''The Recruiting Officer

''The Recruiting Officer'' is a 1706 play by the Irish writer George Farquhar, which follows the social and sexual exploits of two officers, the womanising Plume and the cowardly Brazen, in the town of Shrewsbury (the town where Farquhar himse ...

'', and ''Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Battl ...

''. ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as ...

'' was their first performance, shown initially on September 15, 1752. Encountering opposition from religious organizations, Hallam and his company left for Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

in 1754 or 1755. Soon after, Lewis Hallam, Jr., founded the American Company, opened a theater in New York, and presented the first professionally mounted American play—''The Prince of Parthia

''The Prince of Parthia'' is a Neo-Classical tragedy by Thomas Godfrey and was the first stage play written by an American to be presented in the United States by a professional cast of actors, on April 24, 1767. It was first published in 176 ...

'', by Thomas Godfrey—in 1767.

In the 18th century, laws forbidding the performance of plays were passed in Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

in 1750, in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

in 1759, and in Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

in 1761, and plays were banned in most states during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

at the urging of the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

. In 1794, president of Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

, Timothy Dwight IV

Timothy Dwight (May 14, 1752January 11, 1817) was an American academic and educator, a Congregationalist minister, theologian, and author. He was the eighth president of Yale College (1795–1817).

Early life

Timothy Dwight was born May 14, 17 ...

, in his "Essay on the Stage", declared that "to indulge a taste for playgoing means nothing more or less than the loss of that most valuable treasure: the immortal soul."

In spite of such laws, a few writers tried their hand at playwriting. Most likely, the first plays written in America were by European-born authors—we know of original plays being written by Spaniards, Frenchmen and Englishmen dating back as early as 1567—although no plays were printed in America until Robert Hunter's ''Androboros

''Androboros'' is a play by Robert Hunter written in 1715 when Hunter was serving as the colonial governor of New York and New Jersey. It survives as the earliest known play ever written and published in the North American British colonies. Th ...

'' in 1714. Still, in the early years, most of the plays produced came from Europe; only with Godfrey's ''The Prince of Parthia'' in 1767 do we get a professionally produced play written by an American, although it was a last-minute substitute for Thomas Forrest's comic opera '' The Disappointment; or, The Force of Credulity'', and although the first play to treat American themes seriously, ''Ponteach; or, the Savages of America'' by Robert Rogers Robert Rogers may refer to:

Politics

* Robert Rogers (Irish politician) (died 1719), Irish politician, MP for Cork City 1692–1699

*Robert Rogers (Manitoba politician) (1864–1936), Canadian politician

* Robert Rogers, Baron Lisvane (born 1950), ...

, had been published in London a year earlier.Meserve, Walter J. ''An Outline History of American Drama,'' New York: Feedback/Prospero, 1994. 'Cato', a play about revolution, was performed for George Washington and his troops at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777–1778.

The Revolutionary period was a boost for dramatists, for whom the political debates were fertile ground for both satire, as seen in the works of Mercy Otis Warren

Mercy Otis Warren (September 14, eptember 25, New Style1728 – October 19, 1814) was an American activist poet, playwright, and pamphleteer during the American Revolution. During the years before the Revolution, she had published poems and pla ...

and Colonel Robert Munford, and for plays about heroism, as in the works of Hugh Henry Brackenridge

Hugh Henry Brackenridge (1748June 25, 1816) was an American writer, lawyer, judge, and justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

A frontier citizen in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States, he founded both the Pittsburgh Academy, now the ...

. The postwar period saw the birth of American social comedy in Royall Tyler

Royall Tyler (June 18, 1757 – August 26, 1826) was an American jurist and playwright. He was born in Boston, graduated from Harvard University in 1776, and then served in the Massachusetts militia during the American Revolution. He was ad ...

's '' The Contrast'', which established a much-imitated version of the "Yankee" character, here named "Jonathan". But there were no professional dramatists until William Dunlap

William Dunlap (February 19, 1766 – September 28, 1839) was a pioneer of American theater. He was a producer, playwright, and actor, as well as a historian. He managed two of New York City's earliest and most prominent theaters, the John Str ...

, whose work as playwright, translator, manager and theater historian has earned him the title of "Father of American Drama"; in addition to translating the plays of August von Kotzebue

August Friedrich Ferdinand von Kotzebue (; – ) was a German dramatist and writer who also worked as a consul in Russia and Germany.

In 1817, one of Kotzebue's books was burned during the Wartburg festival. He was murdered in 1819 by Karl L ...

and French melodramas, Dunlap wrote plays in a variety of styles, of which ''André

André — sometimes transliterated as Andre — is the French and Portuguese form of the name Andrew, and is now also used in the English-speaking world. It used in France, Quebec, Canada and other French-speaking countries. It is a variation o ...

'' and '' The Father; or, American Shandyism'' are his best.

The 19th century

Prewar theater

At 825 Walnut Street inPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, Pennsylvania, is the Walnut Street Theatre

The Walnut Street Theatre, founded in 1809 at 825 Walnut Street, on the corner of S. 9th Street in the Washington Square West neighborhood of Philadelphia, is the oldest operating theatre in the United States. The venue is operated by the Walnut ...

, or, "The Walnut." Founded in 1809 by the Circus of Pepin and Breschard

The equestrian theatre company of Pépin and Breschard, American Victor Pépin and Frenchman Jean Baptiste Casmiere Breschard, arrived in the United States of America from Madrid, Spain (where they had performed during the 1805 and 1806 seasons), ...

, "The Walnut" is the oldest theater in America. The Walnut's first theatrical production, ''The Rivals'', was staged in 1812. In attendance were President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

and the Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revoluti ...

.

Provincial theaters frequently lacked heat and minimal theatrical property

A prop, formally known as (theatrical) property, is an object used on stage or screen by actors during a performance or screen production. In practical terms, a prop is considered to be anything movable or portable on a stage or a set, distinct ...

("props") and scenery

Theatrical scenery is that which is used as a setting for a theatrical production. Scenery may be just about anything, from a single chair to an elaborately re-created street, no matter how large or how small, whether the item was custom-made or ...

. Apace with the country's westward expansion

The United States of America was created on July 4, 1776, with the U.S. Declaration of Independence of thirteen British colonies in North America. In the Lee Resolution two days prior, the colonies resolved that they were free and independe ...

, some entrepreneurs operated floating theaters on barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels ...

s or riverboat

A riverboat is a watercraft designed for inland navigation on lakes, rivers, and artificial waterways. They are generally equipped and outfitted as work boats in one of the carrying trades, for freight or people transport, including luxury un ...

s that would travel from town to town. A large town could afford a long "run"—or period of time during which a touring company would stage consecutive multiple performances—of a production, and in 1841, a single play was shown in New York City for an unprecedented three weeks.

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's works were commonly performed. American plays of the period were mostly melodrama

A modern melodrama is a dramatic work in which the plot, typically sensationalized and for a strong emotional appeal, takes precedence over detailed characterization. Melodramas typically concentrate on dialogue that is often bombastic or exces ...

s, a famous example of which was ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U. ...

'', adapted by George Aiken

George David Aiken (August 20, 1892November 19, 1984) was an American politician and horticulturist. A member of the Republican Party, he was the 64th governor of Vermont (1937–1941) before serving in the United States Senate for 34 years, ...

, from the novel of the same name by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and became best known for her novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1852), which depicts the harsh ...

.

In 1821, William Henry Brown established the African Grove Theatre

The African Grove Theatre opened in New York City in 1821. It was founded and operated by William Alexander Brown,Hatch, James V., and Ted Shine. ''Black Theatre USA: Plays by African Americans: The Early Period, 1847––1938''. New York: Free, ...

in New York City. It was the third attempt to have an African-American theater, but this was the most successful of them all. The company put on not only Shakespeare, but also staged the first play written by an African-American, ''The Drama of King Shotaway

''The Drama of King Shotaway, founded on Facts taken from the Insurrection of the Caravs on the Island of St. Vincent, written from Experience by Mr. Brown'' (1823) was a play believed to be by William Henry Brown. The first known play by a black ...

''. The theater was shut down in 1823.World Encyclopedia, p. 402 African-American theater was relatively dormant, except for the 1858 play ''The Escape; or, A Leap for Freedom'' by William Wells Brown

William Wells Brown (c. 1814 – November 6, 1884) was a prominent abolitionist lecturer, novelist, playwright, and historian in the United States. Born into slavery in Montgomery County, Kentucky, near the town of Mount Sterling, Brown escap ...

, who was an ex-slave. African-American works would not be regarded again until the 1920s Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the t ...

.

A popular form of theater during this time was the minstrel show

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of racist theatrical entertainment developed in the early 19th century.

Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music performances that depicted people spe ...

, which featured white (and sometimes, especially after the Civil War, black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

) actors dressed in "blackface

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used predominantly by non-Black people to portray a caricature of a Black person.

In the United States, the practice became common during the 19th century and contributed to the spread of racial stereo ...

(painting one's face, etc. with dark makeup to imitate the coloring of an African

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

or African American)." The players entertained the audience using comic skits, parodies of popular plays and musicals, and general buffoonery and slapstick comedy, all with heavy utilization of racial stereotyping

An ethnic stereotype, racial stereotype or cultural stereotype involves part of a system of beliefs about typical characteristics of members of a given ethnic group, their status, societal and cultural norms. A national stereotype, or nation ...

and racist

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

themes.

Throughout the 19th century, theater culture was associated with hedonism

Hedonism refers to a family of theories, all of which have in common that pleasure plays a central role in them. ''Psychological'' or ''motivational hedonism'' claims that human behavior is determined by desires to increase pleasure and to decr ...

and even violence; actors (especially women) were looked upon as little better than prostitutes. Jessie Bond

Jessie Charlotte Bond (10 January 1853 – 17 June 1942) was an English singer and actress best known for creating the mezzo-soprano soubrette roles in the Gilbert and Sullivan comic operas. She spent twenty years on the stage, the bulk of th ...

wrote that by the middle of the 19th century, "The stage was at a low ebb, Elizabethan glories and Georgian artificialities had alike faded into the past, stilted tragedy and vulgar farce were all the would-be playgoer had to choose from, and the theater had become a place of evil repute". On April 15, 1865, less than a week after the end of the United States Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, while watching a play at Ford's Theater

Ford's Theatre is a theater located in Washington, D.C., which opened in August 1863. The theater is infamous for being the site of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. On the night of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth entered the theater box ...

in Washington, D.C., was assassinated by a nationally popular stage-actor of the period, John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838 – April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who assassinated United States President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the prominent 19th-century Booth th ...

.

Victorian burlesque

Victorian burlesque, sometimes known as travesty or extravaganza, is a genre of theatrical entertainment that was popular in Victorian era, Victorian England and in the New York theatre of the mid-19th century. It is a form of parody music, parod ...

, a form of bawdy comic theater mocking high art and culture, was imported from England about 1860 and in America became a form of farce

Farce is a comedy that seeks to entertain an audience through situations that are highly exaggerated, extravagant, ridiculous, absurd, and improbable. Farce is also characterized by heavy use of physical humor; the use of deliberate absurdity o ...

in which females in male roles mocked the politics and culture of the day. Criticized for its sexuality and outspokenness, this form of entertainment was hounded off the "legitimate stage" and found itself relegated to saloons and barrooms. The female producers, such as Lydia Thompson

Lydia Thompson (born Eliza Thompson; 19 February 1838 – 17 November 1908), was an English dancer, comedian, actor and theatrical producer.

From 1852, as a teenager, she danced and performed in pantomimes, in the UK and then in Europe and soo ...

were replaced by their male counterparts, who toned down the politics and played up the sexuality, until the burlesque shows eventually became little more than pretty girls in skimpy clothing singing songs, while male comedians told raunchy jokes.

The drama of the prewar period tended to be a derivative in form, imitating European melodramas and romantic tragedies, but native in content, appealing to popular nationalism by dramatizing current events and portraying American heroism. But playwrights were limited by a set of factors, including the need for plays to be profitable, the middle-brow tastes of American theater-goers, and the lack of copyright protection and compensation for playwrights. During this time, the best strategy for a dramatist was to become an actor and/or a manager, after the model of John Howard Payne

John Howard Payne (June 9, 1791 – April 10, 1852) was an American actor, poet, playwright, and author who had nearly two decades of a theatrical career and success in London. He is today most remembered as the creator of "Home! Sweet Home ...

, Dion Boucicault

Dionysius Lardner "Dion" Boucicault (né Boursiquot; 26 December 1820 – 18 September 1890) was an Irish actor and playwright famed for his melodramas. By the later part of the 19th century, Boucicault had become known on both sides of the ...

and John Brougham

John Brougham (9 May 1814 – 7 June 1880) was an Irish-American actor and dramatist.

Biography

He was born at Dublin. His father was an amateur painter, and died young. His mother was the daughter of a Huguenot, whom political adversity had f ...

. This period saw the popularity of certain native character types, especially the "Yankee", the "Negro" and the "Indian", exemplified by the characters of Jonathan, Sambo

, aka = Sombo (in English-speaking countries)

, focus = Hybrid

, country = Soviet Union

, pioneers = Viktor Spiridonov, Vasili Oshchepkov, Anatoly Kharlampiev

, famous_pract = List of Practitioners

, oly ...

and Metamora. Meanwhile, increased immigration brought a number of plays about the Irish and Germans, which often dovetailed with concerns over temperance and Roman Catholic. This period also saw plays about American expansion to the West (including plays about Mormonism) and about women's rights. Among the best plays of the period are James Nelson Barker

James Nelson Barker (June 17, 1784 – March 9, 1858) was an American soldier, playwright and politician. He rose to the rank of major in the Army during the War of 1812, wrote ten plays, and was mayor of Philadelphia.

Early life

Barker was bo ...

's ''Superstition; or, the Fanatic Father'', Anna Cora Mowatt

Anna Cora Mowatt Ritchie (, Ogden; after first marriage, Mowatt; after second marriage, Ritchie; pseudonyms, Isabel, Henry C. Browning, and Helen Berkley; March 5, 1819July 21, 1870) was a French-born American author, playwright, public reader, ...

's ''Fashion; or, Life in New York'', Nathaniel Bannister

Nathaniel Harrington Bannister (January 13, 1813 – November 2, 1847) was an American actor and playwright.

Bannister wrote over 40 plays, including ''Putnam, the Iron Son of '76'' (1844) about the American Revolutionary War hero Israel Pu ...

's ''Putnam, the Iron Son of '76

''Putnam, the Iron Son of '76'' is an 1844 American play by Nathaniel Bannister, and his most popular play.

The play is about American Revolutionary War hero Israel Putnam. Starting on August 5, 1844, it played for 78 consecutive nights (not ...

'', Dion Boucicault

Dionysius Lardner "Dion" Boucicault (né Boursiquot; 26 December 1820 – 18 September 1890) was an Irish actor and playwright famed for his melodramas. By the later part of the 19th century, Boucicault had become known on both sides of the ...

's '' The Octoroon; or, Life in Louisiana'', and Cornelius Mathews

Cornelius Mathews (October 28, 1817 – March 25, 1889) was an American writer, best known for his crucial role in the formation of a literary group known as Young America in the late 1830s, with editor Evert Duyckinck and author William Gi ...

's ''Witchcraft; or, the Martyrs of Salem''. At the same time, America had created new dramatic forms in the Tom Shows

Tom show is a general term for any play or musical based (often only loosely) on the 1852 novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' by Harriet Beecher Stowe. The novel attempts to depict the harsh reality of slavery. Due to the weak copyright laws at the tim ...

, the showboat theater and the minstrel show

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of racist theatrical entertainment developed in the early 19th century.

Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music performances that depicted people spe ...

.

Postwar theater

During

During postbellum

may refer to:

* Any post-war period or era

* Post-war period following the American Civil War (1861–1865); nearly synonymous to Reconstruction era (1863–1877)

* Post-war period in Peru following its defeat at the War of the Pacific (1879� ...

North, theater flourished as a postwar boom allowed longer and more-frequent productions. The advent of American rail transport allowed production companies, actors, and large, elaborate sets to travel easily between towns, which made permanent theaters in small towns feasible. The invention and practical application of electric light

An electric light, lamp, or light bulb is an electrical component that produces light. It is the most common form of artificial lighting. Lamps usually have a base made of ceramic, metal, glass, or plastic, which secures the lamp in the soc ...

ing also led to changes to and improvements of scenery styles as well as changes in the design of theater interiors and seating areas.

In 1896, Charles Frohman

Charles Frohman (July 15, 1856 – May 7, 1915) was an American theater manager and producer, who discovered and promoted many stars of the American stage. Notably, he produced ''Peter Pan'', both in London and the US, the latter production ...

, Al Hayman

Al Hayman, also known as Raphael Hayman, (1847 – February 10, 1917) was the business partner of the better-known Charles Frohman who together with others established the Theatrical Syndicate. In addition to the financial backing, ownership an ...

, Abe Erlanger

Abraham Lincoln Erlanger (May 4, 1859 – March 7, 1930) was an American theatrical producer, director, designer, theater owner, and a leading figure of the Theatrical Syndicate.

Biography

Erlanger was born to a Jewish family

, Mark Klaw

Marc Klaw, (born Marcus Alonzo Klaw, May 29, 1858 – June 14, 1936) was an American lawyer, theatrical producer, theater owner, and a leading figure of the Theatrical Syndicate.

Life and work

Referred to as both Mark and Marc, he was born in ...

, Samuel F. Flenderson, and J. Fred Zimmerman, Sr.

John Frederick Zimmerman Sr. (1843–1925) was an American theatre magnate. He was one of the members of the Theatrical Syndicate, which monopolized theatrical bookings in the United States for several years.

Early years

Zimmerman was born in 18 ...

formed the Theatrical Syndicate

Starting in 1896, the Theatrical Syndicate was an organisation that in the United States that controlled the majority of bookings in the country's leading theatrical attractions. The six-man group was in charge of theatres and bookings.

Beginnin ...

, which established systemized booking

Booking may refer to:

* Making an appointment for a meeting or gathering, as part of event planning/scheduling

* The intake or admission process into a prison or psychiatric facility.

* ''Booking'' (manhwa), a Korean comics anthology magazine pub ...

networks throughout the United States, and created a management monopoly that controlled every aspect of contracts and bookings until the turn of the 20th century, when the Shubert brothers

The Shubert family was responsible for the establishment of the Broadway district, in New York City, as the hub of the theater industry in the United States. They dominated the legitimate theater and vaudeville in the first half of the 20th cen ...

founded rival agency, The Shubert Organization

The Shubert Organization is a theatrical producing organization and a major owner of theatres based in Manhattan, New York City. It was founded by the three Shubert brothers in the late 19th century. They steadily expanded, owning many theaters ...

.

For playwrights, the period after the War brought more financial reward and aesthetic respect (including professional criticism) than was available earlier. In terms of form, spectacles, melodramas and farces remained popular, but poetic drama and romanticism almost died out completely due to the new emphasis upon realism, which was adopted by serious drama, melodrama and comedy alike. This realism was not quite the European realism of Ibsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright and theatre director. As one of the founders of modernism in theatre, Ibsen is often referred to as "the father of realism" and one of the most influential playw ...

's ''Ghosts

A ghost is the soul or spirit of a dead person or animal that is believed to be able to appear to the living. In ghostlore, descriptions of ghosts vary widely from an invisible presence to translucent or barely visible wispy shapes, to rea ...

'', but a combination of scenic realism (e.g., the " Belasco Method") with a less romantic view of life that accompanied the cultural turmoil of the period. The most ambitious effort towards realism during this period came from James Herne

James A. Herne (born James Ahearn; February 1, 1839 – June 2, 1901) was an American playwright and actor. He is considered by some critics to be the "American Ibsen", and his controversial play ''Margaret Fleming'' is often credited with havin ...

, who was influenced by the ideas of Ibsen, Hardy and Zola Zola may refer to:

People

* Zola (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* Zola (musician) (born 1977), South African entertainer

* Zola (rapper), French rapper

* Émile Zola, a major nineteenth-century French writer

Plac ...

regarding realism, truth, and literary quality; his most important achievement, '' Margaret Fleming'', enacts the principles he expounded in his essay "Art for Truth's Sake in the Drama". Although ''Fleming'' did not appeal to audiences—critics and audiences felt it dwelt too much on unseemly topics and included improper scenes, such as Margaret nursing her husband's bastard child onstage—other forms of dramatic realism were becoming more popular in melodrama (e.g., Augustin Daly

John Augustin Daly (July 20, 1838June 7, 1899) was one of the most influential men in American theatre during his lifetime. Drama critic, theatre manager, playwright, and adapter, he became the first recognized stage director in America. He exer ...

's ''Under the Gaslight

''Under the Gaslight'' is an 1867 play by Augustin Daly. It was his first successful play, and is a primary example of a melodrama, best known for its suspense scene where a person is tied to railroad tracks as a train approaches, only to be ...

'') and in local color plays (Bronson Howard

Bronson Crocker Howard (October 7, 1842 – August 4, 1908) was an American dramatist.

Biography

Howard was born in Detroit where his father Charles Howard was Mayor in 1849. He prepared for college at New Haven, Conn., but instead of ente ...

's ''Shenandoah''). Other key dramatists during this period are David Belasco

David Belasco (July 25, 1853 – May 14, 1931) was an American theatrical producer, impresario, director, and playwright. He was the first writer to adapt the short story ''Madame Butterfly'' for the stage. He launched the theatrical career of m ...

, Steele MacKaye

James Morrison Steele MacKaye ( ; June 6, 1842 – February 25, 1894) was an American playwright, actor, theater manager and inventor. Having acted, written, directed and produced numerous and popular plays and theatrical spectaculars of the day ...

, William Dean Howells

William Dean Howells (; March 1, 1837 – May 11, 1920) was an American realist novelist, literary critic, and playwright, nicknamed "The Dean of American Letters". He was particularly known for his tenure as editor of ''The Atlantic Monthly'', ...

, Dion Boucicault

Dionysius Lardner "Dion" Boucicault (né Boursiquot; 26 December 1820 – 18 September 1890) was an Irish actor and playwright famed for his melodramas. By the later part of the 19th century, Boucicault had become known on both sides of the ...

, and Clyde Fitch

Clyde Fitch (May 2, 1865 – September 4, 1909) was an American dramatist, the most popular writer for the Broadway stage of his time (c. 1890–1909).

Biography

Born in Elmira, New York, and educated at Holderness School and Amherst College (cl ...

.

The 20th century

Vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

was common in the late 19th and early 20th century, and is notable for heavily influencing early film, radio, and television productions in the country. (This was born from an earlier American practice of having singers and novelty acts perform between acts in a standard play.) George Burns

George Burns (born Nathan Birnbaum; January 20, 1896March 9, 1996) was an American comedian, actor, writer, and singer, and one of the few entertainers whose career successfully spanned vaudeville, radio, film and television. His arched eyebr ...

was a very long-lived American comedian who started out in the vaudeville community, but went on to enjoy a career running until the 1990s.

Some vaudeville theaters built between about 1900 and 1920

Events January

* January 1

** Polish–Soviet War in 1920: The Russian Red Army increases its troops along the Polish border from 4 divisions to 20.

** Kauniainen, completely surrounded by the city of Espoo, secedes from Espoo as its own ma ...

managed to survive as well, though many went through periods of alternate use, most often as movie theaters until the second half of the century saw many urban populations decline and multiplexes built in the suburbs. Since that time, a number have been restored to original or nearly-original condition and attract new audiences nearly one hundred years later.

By the beginning of the 20th century, legitimate 1752 (non-vaudeville) theater had become decidedly more sophisticated in the United States, as it had in Europe. The stars of this era, such as Ethel Barrymore

Ethel Barrymore (born Ethel Mae Blythe; August 15, 1879 – June 18, 1959) was an American actress and a member of the Barrymore family of actors. Barrymore was a stage, screen and radio actress whose career spanned six decades, and was regarde ...

and John Barrymore

John Barrymore (born John Sidney Blyth; February 14 or 15, 1882 – May 29, 1942) was an American actor on stage, screen and radio. A member of the Drew and Barrymore theatrical families, he initially tried to avoid the stage, and briefly att ...

, were often seen as even more important than the show itself. The advance of motion pictures also led to many changes in theater. The popularity of musicals may have been due in part to the fact the early films had no sound, and could thus not compete, until ''The Jazz Singer

''The Jazz Singer'' is a 1927 American musical drama film directed by Alan Crosland. It is the first feature-length motion picture with both synchronized recorded music score as well as lip-synchronous singing and speech (in several isolated ...

'' of 1927, which combined both talking and music in a moving picture. More complex and sophisticated dramas bloomed in this time period, and acting styles became more subdued. Even by 1915, actors were being lured away from theater and to the silver screen

A silver screen, also known as a silver lenticular screen, is a type of projection screen that was popular in the early years of the motion picture industry and passed into popular usage as a metonym for the cinema industry. The term silver scree ...

, and vaudeville was beginning to face stiff competition.

While revue

A revue is a type of multi-act popular theatrical entertainment that combines music, dance, and sketches. The revue has its roots in 19th century popular entertainment and melodrama but grew into a substantial cultural presence of its own duri ...

s consisting of mostly unconnected songs, sketches, comedy routines, and dancing girls (Ziegfeld girl

Ziegfeld Girls were the chorus girls and showgirls from Florenz Ziegfeld's theatrical Broadway revue spectaculars known as the ''Ziegfeld Follies'' (1907–1931), in New York City, which were based on the Folies Bergère of Paris.

Descripti ...

s) dominated for the first 20 years of the 20th century, musical theater would eventually develop beyond this. One of the first major steps was ''Show Boat

''Show Boat'' is a musical with music by Jerome Kern and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. It is based on Edna Ferber's best-selling 1926 novel of the same name. The musical follows the lives of the performers, stagehands and dock worke ...

'', with music by Jerome Kern

Jerome David Kern (January 27, 1885 – November 11, 1945) was an American composer of musical theatre and popular music. One of the most important American theatre composers of the early 20th century, he wrote more than 700 songs, used in over ...

and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein. It featured songs and non-musical scenes which were integrated to develop the show's plot. The next great step forward was ''Oklahoma!

''Oklahoma!'' is the first musical theater, musical written by the duo of Rodgers and Hammerstein. The musical is based on Lynn Riggs' 1931 play, ''Green Grow the Lilacs (play), Green Grow the Lilacs''. Set in farm country outside the town of ...

'', with lyrics by Hammerstein and music by Richard Rodgers

Richard Charles Rodgers (June 28, 1902 – December 30, 1979) was an American Musical composition, composer who worked primarily in musical theater. With 43 Broadway musicals and over 900 songs to his credit, Rodgers was one of the most ...

. Its "dream ballets" used dance to carry forward the plot and develop the characters.

Amateur performing groups have always had a place alongside professional acting companies. The Amateur Comedy Club, Inc. was founded in New York City on April 18, 1884. It was organized by seven gentlemen who broke away from the Madison Square Dramatic Organization, a socially prominent company presided over by Mrs. James Brown Potter and David Belasco

David Belasco (July 25, 1853 – May 14, 1931) was an American theatrical producer, impresario, director, and playwright. He was the first writer to adapt the short story ''Madame Butterfly'' for the stage. He launched the theatrical career of m ...

. The ACC staged its first performance on February 13, 1885. It has performed continuously ever since, making it the oldest, continuously performing theatrical society in the United States. Prominent New Yorkers who have been members of the ACC include Theodore, Frederick and John Steinway of the piano manufacturing family; Gordon Grant, the marine artist; Christopher La Farge, the architect; Van H. Cartmell, the publisher; Albert Sterner

Albert Edward Sterner (March 8, 1863 – December 16, 1946) was a British-American illustrator and painter.

Early life

Sterner was born to a Jewish family in London, and attended King Edward's School, Birmingham. After a brief period in Germany, ...

, the painter; and Edward Fales Coward, the theater critic and playwright. Elsie De Wolfe, Lady Mendl, later famous as the world's first professional interior decorator, acted in Club productions in the early years of the 20th Century, as did Hope Williams

Hope Williams Brady is a fictional character from '' Days of Our Lives'', an American soap opera on the NBC network. Created by writer William J. Bell, she was portrayed by Kristian Alfonso on and off from April 1983 to October 2020. Hope is a mem ...

, and Julie Harris in the 1940s.

Early 20th century theater was dominated by the Barrymores—Ethel Barrymore

Ethel Barrymore (born Ethel Mae Blythe; August 15, 1879 – June 18, 1959) was an American actress and a member of the Barrymore family of actors. Barrymore was a stage, screen and radio actress whose career spanned six decades, and was regarde ...

, John Barrymore

John Barrymore (born John Sidney Blyth; February 14 or 15, 1882 – May 29, 1942) was an American actor on stage, screen and radio. A member of the Drew and Barrymore theatrical families, he initially tried to avoid the stage, and briefly att ...

, and Lionel Barrymore

Lionel Barrymore (born Lionel Herbert Blythe; April 28, 1878 – November 15, 1954) was an American actor of stage, screen and radio as well as a film director. He won an Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in ''A Free Soul'' (1931) ...

. Other greats included Laurette Taylor

Laurette Taylor (born Loretta Helen Cooney; April 1, 1883Source Citation: Year: 1900; Census Place: Manhattan, New York, New York; Roll: 1119; Page: 3A; Enumeration District: 859; FHL microfilm: 1241119. Source Information: Ancestry.com. 1900 Un ...

, Jeanne Eagels

Jeanne Eagels (born Eugenia Eagles; June 26, 1890 – October 3, 1929) was an American stage and film actress. A former Ziegfeld Girl, Eagels went on to greater fame on Broadway and in the emerging medium of sound films. She was posthumously no ...

, and Eva Le Gallienne

Eva Le Gallienne (January 11, 1899 – June 3, 1991) was a British-born American stage actress, producer, director, translator, and author. A Broadway star by age 21, Le Gallienne gave up her Broadway appearances to devote herself to founding t ...

.

The massive social change that went on during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

also had an effect on theater in the United States. Plays took on social roles, identifying with immigrants and the unemployed. The Federal Theatre Project

The Federal Theatre Project (FTP; 1935–1939) was a theatre program established during the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depression as part of the New Deal to fund live artistic performances and entertainment programs in the United ...

, a New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

program set up by Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, helped to promote theater and provide jobs for actors. The program staged many elaborate and controversial plays such as ''It Can't Happen Here

''It Can't Happen Here'' is a 1935 dystopian political novel by American author Sinclair Lewis. It describes the rise of a United States dictator similar to how Adolf Hitler gained power. The novel was adapted into a play by Lewis and John C. Mo ...

'' by Sinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American writer and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was ...

and ''The Cradle Will Rock

''The Cradle Will Rock'' is a 1937 play in music by Marc Blitzstein. Originally a part of the Federal Theatre Project, it was directed by Orson Welles and produced by John Houseman. A Brechtian allegory of corruption and corporate greed, it ...

'' by Marc Blitzstein

Marcus Samuel Blitzstein (March 2, 1905January 22, 1964), was an American composer, lyricist, and librettist. He won national attention in 1937 when his pro-union musical ''The Cradle Will Rock'', directed by Orson Welles, was shut down by the Wo ...

. By contrast, the legendary producer Brock Pemberton

Brock Pemberton (December 14, 1885 – March 11, 1950) was an American theatrical producer, director and founder of the Tony Awards. He was the professional partner of Antoinette Perry, co-founder of the American Theatre Wing, and he was also a m ...

(founder of the Tony Awards

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as the Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual cer ...

) was among those who felt that it was more than ever a time for comic entertainment, in order to provide an escape from the prevailing harsh social conditions: typical of his productions was Lawrence Riley

Lawrence Riley (1896–1974) was a successful American playwright and screenwriter. He gained fame in 1934 as the author of the Broadway hit ''Personal Appearance'', which was turned by Mae West into the film ''Go West, Young Man'' (1936).

Bio ...

's comedy ''Personal Appearance

''Personal Appearance'' (1934) is a stage comedy by the American playwright and screenwriter Lawrence Riley (1896–1974), which was a Broadway smash and the basis for the classic Mae West film ''Go West, Young Man'' ( 1936).

''Personal Ap ...

'' (1934), whose success on Broadway (501 performances) vindicated Pemberton.

The years between the World Wars were years of extremes. Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright and Nobel laureate in literature. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of realism, earlier ...

's plays were the high point for serious dramatic plays leading up to the outbreak of war in Europe. '' Beyond the Horizon'' (1920), for which he won his first Pulitzer Prize; he later won Pulitzers for ''Anna Christie

''Anna Christie'' is a play in four acts by Eugene O'Neill. It made its Broadway debut at the Vanderbilt Theatre on November 2, 1921. O'Neill received the 1922 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for this work. According to historian Paul Avrich, the orig ...

'' (1922) and ''Strange Interlude

''Strange Interlude'' is an experimental play in nine acts by American playwright Eugene O'Neill. O'Neill began work on it as early as 1923 and developed its scenario in 1925; he wrote the play between May 1926 and the summer of 1927, and complete ...

'' (1928) as well as the Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901

, ...

. Alfred Lunt

Alfred David Lunt (August 12, 1892 – August 3, 1977) was an American actor and director, best known for his long stage partnership with his wife, Lynn Fontanne, from the 1920s to 1960, co-starring in Broadway theatre, Broadway and West End thea ...

and Lynn Fontanne

Lynn Fontanne (; 6 December 1887 – 30 July 1983) was an English actress. After early success in supporting roles in the West End, she met the American actor Alfred Lunt, whom she married in 1922 and with whom she co-starred in Broadway and We ...

remained a popular acting couple in the 1930s.

1940 proved to be a pivotal year for African-American theater. Frederick O'Neal

Frederick O'Neal (August 27, 1905 – August 25, 1992) was an American actor, theater producer and television director. He founded the American Negro Theater, the British Negro Theatre, and was the first African-American president of the Actors ...

and Abram Hill founded ANT, or the American Negro Theater

The American Negro Theatre (ANT) was co-founded on June 5, 1940 by playwright Abram Hill and actor Frederick O'Neal. Determined to build a "people's theatre", they were inspired by the Federal Theatre Project's Negro Unit in Harlem and by W. E. ...

, the most renowned African-American theater group of the 1940s. Their stage was small and located in the basement of a library in Harlem, and most of the shows were attended and written by African-Americans. Some shows include Theodore Browne's ''Natural Man'' (1941), Abram Hill's ''Walk Hard'' (1944), and Owen Dodson

Owen Vincent Dodson (November 28, 1914 – June 21, 1983) was an American poet, novelist, and playwright. He was one of the leading African-American poets of his time, associated with the generation of black poets following the Harlem Renaissance ...

's ''Garden of Time'' (1945). Many famous actors received their training at ANT, including Harry Belafonte

Harry Belafonte (born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr.; March 1, 1927) is an American singer, activist, and actor. As arguably the most successful Jamaican-American pop star, he popularized the Trinbagonian Caribbean musical style with an interna ...

, Sidney Poitier

Sidney Poitier ( ; February 20, 1927 – January 6, 2022) was an American actor, film director, and diplomat. In 1964, he was the first black actor and first Bahamian to win the Academy Award for Best Actor. He received two competitive ...

, Alice and Alvin Childress

Alvin Childress (September 15, 1907 – April 19, 1986) was an American actor, who is best known for playing the cabdriver Amos Jones in the 1950s television comedy series ''Amos 'n' Andy''.

Biography

Alvin Childress was born in Meridian, Missis ...

, Osceola Archer, Ruby Dee

Ruby Dee (October 27, 1922 – June 11, 2014) was an American actress, poet, playwright, screenwriter, journalist, and civil rights activist. She originated the role of "Ruth Younger" in the stage and film versions of ''A Raisin in the Sun'' (19 ...

, Earle Hyman

Earle Hyman (born George Earle Plummer; October 11, 1926 – November 17, 2017) was an American stage, television, and film actor. Hyman is known for his role on '' ThunderCats'' as the voice of Panthro and various other characters. He also ap ...

, Hilda Simms

Hilda Simms ( Moses; April 15, 1918 – February 6, 1994) was an American stage actress, best known for her starring role on Broadway in '' Anna Lucasta''.

Early years

Hilda Simms was born Hilda Moses in Minneapolis, Minnesota, one of 9 siblings ...

, among many others.

Mid-20th century theater saw a wealth of Great Leading Ladies, including Helen Hayes

Helen Hayes MacArthur ( Brown; October 10, 1900 – March 17, 1993) was an American actress whose career spanned 80 years. She eventually received the nickname "First Lady of American Theatre" and was the second person and first woman to have w ...

, Katherine Cornell, Tallulah Bankhead

Tallulah Brockman Bankhead (January 31, 1902 – December 12, 1968) was an American actress. Primarily an actress of the stage, Bankhead also appeared in several prominent films including an award-winning performance in Alfred Hitchcock's ''Lif ...

, Judith Anderson

Dame Frances Margaret Anderson, (10 February 18973 January 1992), known professionally as Judith Anderson, was an Australian actress who had a successful career in stage, film and television. A pre-eminent stage actress in her era, she won two ...

, and Ruth Gordon

Ruth Gordon Jones (October 30, 1896 – August 28, 1985) was an American actress, screenwriter, and playwright. She began her career performing on Broadway at age 19. Known for her nasal voice and distinctive personality, Gordon gained internati ...

. Musical theater saw stars such as Ethel Merman

Ethel Merman (born Ethel Agnes Zimmermann, January 16, 1908 – February 15, 1984) was an American actress and singer, known for her distinctive, powerful voice, and for leading roles in musical theatre.Obituary ''Variety'', February 22, 1984. ...

, Beatrice Lillie

Beatrice Gladys Lillie, Lady Peel (29 May 1894 – 20 January 1989), known as Bea Lillie, was a Canadian-born British actress, singer and comedic performer.

She began to perform as a child with her mother and sister. She made her West End debu ...

, Mary Martin

Mary Virginia Martin (December 1, 1913 – November 3, 1990) was an American actress and singer. A muse of Rodgers and Hammerstein, she originated many leading roles on stage over her career, including Nellie Forbush in '' South Pacific'' (194 ...

, and Gertrude Lawrence

Gertrude Lawrence (4 July 1898 – 6 September 1952) was an English actress, singer, dancer and musical comedy performer known for her stage appearances in the West End of London and on Broadway in New York.

Early life

Lawrence was born Gertr ...

.

Post World War II theater

After World War II, American theater came into its own. Several American playwrights, such as

After World War II, American theater came into its own. Several American playwrights, such as Arthur Miller

Arthur Asher Miller (October 17, 1915 – February 10, 2005) was an American playwright, essayist and screenwriter in the 20th-century American theater. Among his most popular plays are '' All My Sons'' (1947), ''Death of a Salesman'' ( ...

and Tennessee Williams

Thomas Lanier Williams III (March 26, 1911 – February 25, 1983), known by his pen name Tennessee Williams, was an American playwright and screenwriter. Along with contemporaries Eugene O'Neill and Arthur Miller, he is considered among the thre ...

, became world-renowned.

In the 1950s and 1960s, experimentation in the Arts spread into theater as well, with plays such as ''Hair

Hair is a protein filament that grows from follicles found in the dermis. Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals.

The human body, apart from areas of glabrous skin, is covered in follicles which produce thick terminal and f ...

'' including nudity

Nudity is the state of being in which a human is without clothing.

The loss of body hair was one of the physical characteristics that marked the biological evolution of modern humans from their hominin ancestors. Adaptations related to ...

and drug culture references. Musicals remained popular as well, and musicals such as ''West Side Story

''West Side Story'' is a musical conceived by Jerome Robbins with music by Leonard Bernstein, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, and a book by Arthur Laurents.

Inspired by William Shakespeare's play ''Romeo and Juliet'', the story is set in the mid-1 ...

'' and ''A Chorus Line

''A Chorus Line'' is a 1975 musical with music by Marvin Hamlisch, lyrics by Edward Kleban, and a book by James Kirkwood Jr. and Nicholas Dante.

Set on the bare stage of a Broadway theater, the musical is centered on seventeen Broadway dancers ...

'' broke previous records. At the same time, shows like Stephen Sondheim

Stephen Joshua Sondheim (; March 22, 1930November 26, 2021) was an American composer and lyricist. One of the most important figures in twentieth-century musical theater, Sondheim is credited for having "reinvented the American musical" with sho ...

's ''Company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a Legal personality, legal entity representing an association of people, whether Natural person, natural, Legal person, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common p ...

'' began to deconstruct the musical form as it has been practiced through the mid-century, moving away from traditional plot and realistic external settings to explore the central character's inner state; his ''Follies

''Follies'' is a Musical theater, musical with music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim and a book by James Goldman.

The plot takes place in a crumbling Broadway theater, now scheduled for demolition, previously home to a musical revue (based on t ...

'' relied on pastiches of the Ziegfeld Follies

The ''Ziegfeld Follies'' was a series of elaborate theatrical revue productions on Broadway in New York City from 1907 to 1931, with renewals in 1934 and 1936. They became a radio program in 1932 and 1936 as ''The Ziegfeld Follies of the Air ...

-styled revue; his ''Pacific Overtures

''Pacific Overtures'' is a Musical theater, musical with music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, and a book by John Weidman, with "additional material by" Hugh Wheeler.

Set in 19th-century Japan, it tells the story of the country's westernization ...

'' used Japanese kabuki

is a classical form of Japanese dance-drama. Kabuki theatre is known for its heavily-stylised performances, the often-glamorous costumes worn by performers, and for the elaborate make-up worn by some of its performers.

Kabuki is thought to ...

theatrical practices; and '' Merrily We Roll Along'' told its story backwards. Similarly, Bob Fosse

Robert Louis Fosse (; June 23, 1927 – September 23, 1987) was an American actor, choreographer, dancer, and film and stage director. He directed and choreographed musical works on stage and screen, including the stage musicals ''The Pajam ...

's production of Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

returned the musical to its vaudeville origins.

Facts and figures of the postwar theater

The postwar American theater audiences and box offices constantly diminished, due to the undeclared "offensive" of television and radio upon the classical, legitimate theater

Legitimate theatre is live performance that relies almost entirely on diegetic elements, with actors performing through speech and natural movement.Joyce M. Hawkins and Robert Allen, eds. "Legitimate" entry. ''The Oxford Encyclopedic English Dicti ...

. According to James F. Reilly, executive director of the League of New York Theatres, between 1930 and 1951 the number of legitimate theaters in New York City dwindled from 68 to 30. Besides of that, the admissions tax, has been a burden on the theater since 1918. It was never relaxed ever since, and was doubled in 1943. Total seating capacity of thirty most renown legitimate theaters amounted 35,697 seats in 1951. Since 1937 in New York City alone, 14 former legitimate theaters with a normal seating capacity of 16,955, have been taken over for either radio broadcasts

Radio broadcasting is transmission of audio (sound), sometimes with related metadata, by radio waves to radio receivers belonging to a public audience. In terrestrial radio broadcasting the radio waves are broadcast by a land-based radio sta ...

or television performances.

In the late 1990s and 2000s, American theater began to borrow from cinema and operas. For instance, Julie Taymor

Julie Taymor (born December 15, 1952) is an American director and writer of theater, opera and film. Her stage adaptation of ''The Lion King'' debuted in 1997, and received eleven Tony Award nominations, with Taymor receiving Tony Awards for Best ...

, director of ''The Lion King

''The Lion King'' is a 1994 American animated musical drama film produced by Walt Disney Feature Animation and released by Walt Disney Pictures. The 32nd Disney animated feature film and the fifth produced during the Disney Renaissance, it ...

'' directed ''Die Zauberflöte

''The Magic Flute'' (German: , ), K. 620, is an opera in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to a German libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder. The work is in the form of a ''Singspiel'', a popular form during the time it was written that includ ...

'' at the Metropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera (commonly known as the Met) is an American opera company based in New York City, resident at the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, currently situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The company is operat ...

. Also, Broadway musicals were developed around Disney's ''Mary Poppins It may refer to:

* ''Mary Poppins'' (book series), the original 1934–1988 children's fantasy novels that introduced the character.

* Mary Poppins (character), the nanny with magical powers.

* ''Mary Poppins'' (film), a 1964 Disney film sta ...

'', ''Tarzan

Tarzan (John Clayton II, Viscount Greystoke) is a fictional character, an archetypal feral child raised in the African jungle by the Mangani great apes; he later experiences civilization, only to reject it and return to the wild as a heroic adv ...

'', ''The Little Mermaid

"The Little Mermaid" ( da, Den lille havfrue) is a literary fairy tale written by the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen. The story follows the journey of a young mermaid who is willing to give up her life in the sea as a mermaid to gain a h ...

'', and the one that started it all, ''Beauty and the Beast

''Beauty and the Beast'' (french: La Belle et la Bête) is a fairy tale written by French novelist Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve, Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve and published in 1740 in ''La Jeune Américaine et les contes marins'' ( ...

'', which may have contributed to Times Square

Times Square is a major commercial intersection, tourist destination, entertainment hub, and neighborhood in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. It is formed by the junction of Broadway, Seventh Avenue, and 42nd Street. Together with adjacent ...

's revitalization in the 1990s. Also, Mel Brooks

Mel Brooks (born Melvin James Kaminsky; June 28, 1926) is an American actor, comedian and filmmaker. With a career spanning over seven decades, he is known as a writer and director of a variety of successful broad farces and parodies. He began h ...

's '' The Producers'' and ''Young Frankenstein

''Young Frankenstein'' is a 1974 American comedy horror film directed by Mel Brooks. The screenplay was co-written by Brooks and Gene Wilder. Wilder also starred in the lead role as the title character, a descendant of the infamous Dr. Victor F ...

'' are based on his hit films.

Drama

The early years of the 20th century, before World War I, continued to see realism as the main development in drama. But starting around 1900, there was a revival of poetic drama in the States, corresponding to a similar revival in Europe (e.g.Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

, Maeterlinck

Maurice Polydore Marie Bernard Maeterlinck (29 August 1862 – 6 May 1949), also known as Count (or Comte) Maeterlinck from 1932, was a Belgian playwright, poet, and essayist who was Flemish but wrote in French. He was awarded the Nobel Prize i ...

and Hauptmann

is a German word usually translated as captain when it is used as an officer's rank in the German, Austrian, and Swiss armies. While in contemporary German means 'main', it also has and originally had the meaning of 'head', i.e. ' literally ...

). The most notable example of this trend was the "Biblical trilogy" of William Vaughn Moody

William Vaughn Moody (July 8, 1869 – October 17, 1910) was an American dramatist and poet. Moody was author of ''The Great Divide'', first presented under the title of ''The Sabine Woman'' at the Garrick Theatre in Chicago on April 12, 1906. Hi ...

, which also illustrate the rise of religious-themed drama during the same years, as seen in the 1899 production of '' Ben-Hur'' and two 1901 adaptations of ''Quo Vadis

''Quō vādis?'' (, ) is a Latin phrase meaning "Where are you marching?". It is also commonly translated as "Where are you going?" or, poetically, "Whither goest thou?"

The phrase originates from the Christian tradition regarding Saint Pete ...

''. Moody, however, is best known for two prose plays, ''The Great Divide'' (1906, later adapted into three film versions) and ''The Faith Healer'' (1909), which together point the way to modern American drama in their emphasis on the emotional conflicts that lie at the heart of contemporary social conflicts. Other key playwrights from this period (in addition to continued work by Howells and Fitch) include Edward Sheldon

Edward Brewster Sheldon (Chicago, Illinois, February 4, 1886 – April 1, 1946, New York City) was an American dramatist. His plays include ''Salvation Nell'' (1908) and ''Romance'' (1913), which was made into a motion picture with Greta Garbo.

...

, Charles Rann Kennedy

Charles Rann Kennedy (1808 – 17 December 1867) was an English lawyer and classicist, best remembered for his involvement in the Swinfen will case and the issues of contingency fee agreements and legal ethics that it involved.

Life

Kennedy ...

and one of the most successful women playwrights in American drama, Rachel Crothers

Rachel Crothers (December 12, 1878 – July 5, 1958) was an American playwright and theater director known for her well-crafted plays that often dealt with feminist themes. Among theater historians, she is generally recognized as "the most succes ...

, whose interest in women's issues can be seen in such plays as ''He and She'' (1911).

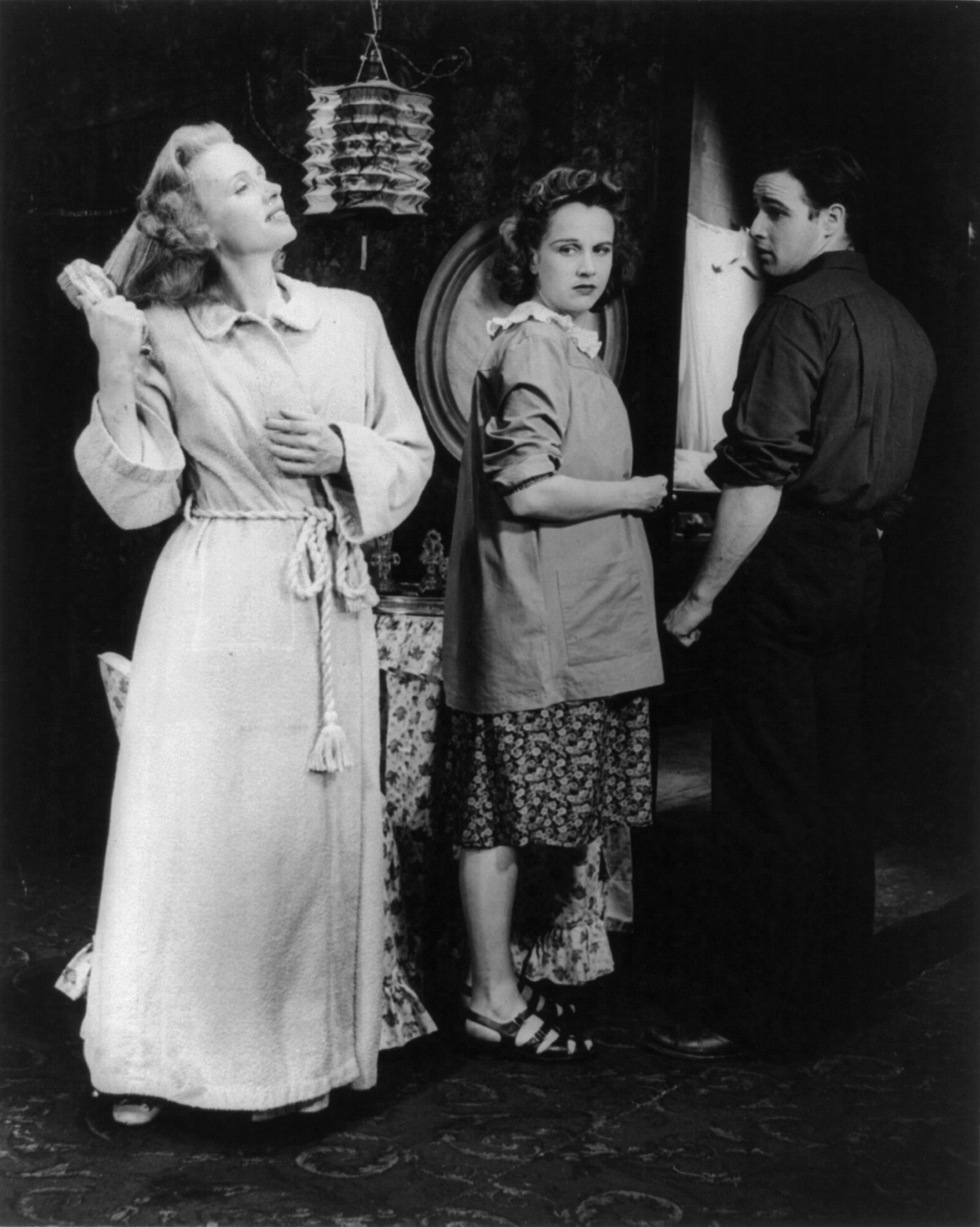

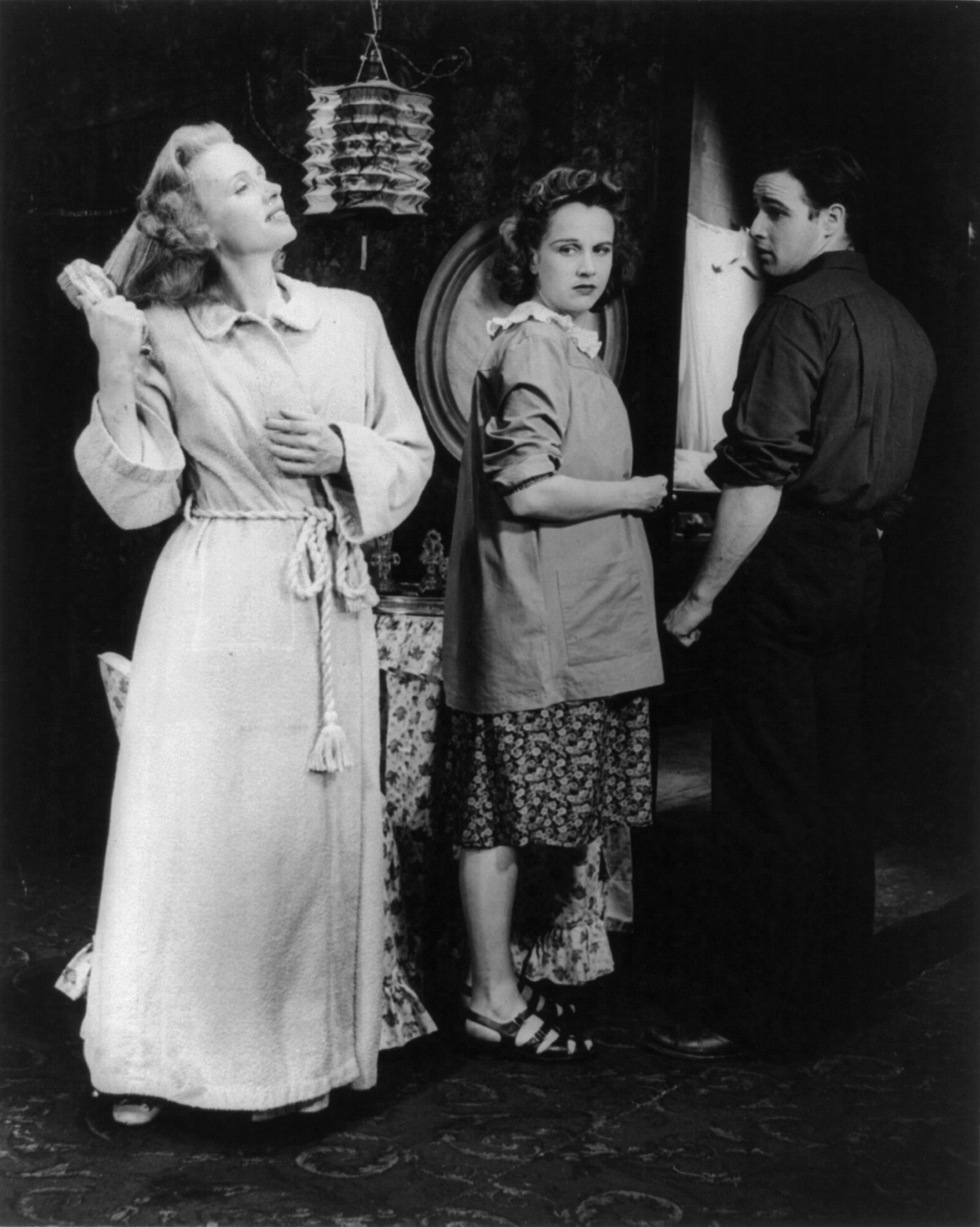

During the period between the World Wars, American drama came to maturity, thanks in large part to the works of

During the period between the World Wars, American drama came to maturity, thanks in large part to the works of Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright and Nobel laureate in literature. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of realism, earlier ...

and of the Provincetown Players

The Provincetown Players was a collective of artists, writers, intellectuals, and amateur theater enthusiasts. Under the leadership of the husband and wife team of George Cram Cook, George Cram “Jig” Cook and Susan Glaspell from Iowa, the Play ...

. O'Neill's experiments with theatrical form and his combination of Naturalist and Expressionist

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it rad ...

techniques inspired other playwrights to use greater freedom in their works, whether expanding the techniques of Realism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

*Classical Realism

*Literary realism, a move ...

, as in Susan Glaspell

Susan Keating Glaspell (July 1, 1876 – July 28, 1948) was an American playwright, novelist, journalist and actress. With her husband George Cram Cook, she founded the Provincetown Players, the first modern American theatre company.

First known ...

's '' Trifles'', or borrowing more heavily from German Expressionism (e.g., Elmer Rice

Elmer Rice (born Elmer Leopold Reizenstein, September 28, 1892 – May 8, 1967) was an American playwright. He is best known for his plays ''The Adding Machine'' (1923) and his Pulitzer Prize-winning drama of New York tenement life, '' Street Sce ...

's ''The Adding Machine

''The Adding Machine'' is a 1923 play by Elmer Rice; it has been called "... a landmark of American Expressionism, reflecting the growing interest in this highly subjective and nonrealistic form of modern drama." Plot

The author of this play ta ...

''), Other distinct movements during this period include folk-drama/regionalism ( Paul Green's Pulitzer-winning ''In Abraham's Bosom

''In Abraham's Bosom'' is a play by American dramatist Paul Green. He was based in North Carolina and wrote historical plays about the South.

Production