Thomas Cochrane, 10th Earl Of Dundonald on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

at Westminster Abbey. His Heraldic flag">banner

A banner can be a flag or another piece of cloth bearing a symbol, logo, slogan or another message. A flag whose design is the same as the shield in a coat of arms (but usually in a square or rectangular shape) is called a banner of arms. Also, ...

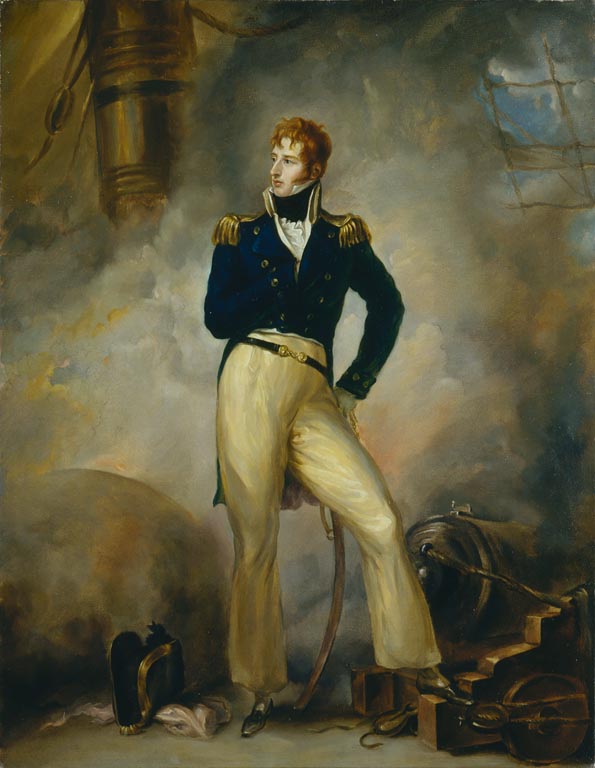

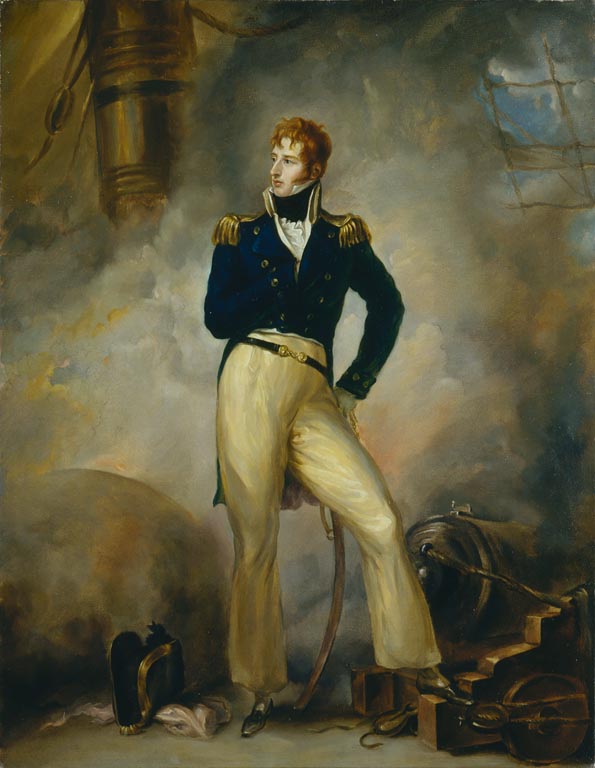

Thomas Cochrane, 10th Earl of Dundonald, Marquess of Maranhão (14 December 1775 – 31 October 1860), styled Lord Cochrane between 1778 and 1831, was a British naval

Thomas Cochrane was born at Annsfield, near

Thomas Cochrane was born at Annsfield, near

One of his most notable exploits was the capture of the Spanish

One of his most notable exploits was the capture of the Spanish

After the

After the

In May 1807, Cochrane was elected by

In May 1807, Cochrane was elected by

The accused were brought to trial in the

The accused were brought to trial in the

at Westminster Abbey"> ...flag officer

A flag officer is a commissioned officer in a nation's armed forces senior enough to be entitled to fly a flag to mark the position from which the officer exercises command.

The term is used differently in different countries:

*In many countr ...

of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, mercenary

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any o ...

and Radical politician. He was a successful captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, leading Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

to nickname him french: le Loup des Mers, lit=the Sea Wolf, label=none. He was successful in virtually all of his naval actions.

He was dismissed from the Royal Navy in 1814 after a controversial conviction for fraud on the Stock Exchange

A stock exchange, securities exchange, or bourse is an exchange where stockbrokers and traders can buy and sell securities, such as shares of stock, bonds and other financial instruments. Stock exchanges may also provide facilities for th ...

. He helped organise and lead the rebel navies of Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

and Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

during their respective successful wars of independence through the 1820s. While in charge of the Chilean Navy, Cochrane also contributed to Peruvian independence

Peruvians ( es, peruanos) are the citizens of Peru. There were Andean and coastal ancient civilizations like Caral, which inhabited what is now Peruvian territory for several millennia before the Spanish conquest of Peru, Spanish conquest in th ...

through the Freedom Expedition of Perú

The Liberating Expedition of Peru ( es, Expedición Libertadora del Perú) was a naval and land military force created in 1820 by the government of Chile in continuation of the plan of the Argentine General José de San Martín to achieve the in ...

. He was also hired to help the Greek Navy

The Hellenic Navy (HN; el, Πολεμικό Ναυτικό, Polemikó Naftikó, War Navy, abbreviated ΠΝ) is the naval force of Greece, part of the Hellenic Armed Forces. The modern Greek navy historically hails from the naval forces of vario ...

, but did not have much impact.

In 1832, he was pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the ju ...

ed by the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

and reinstated in the Royal Navy with the rank of Rear-Admiral of the Blue

The Rear-Admiral of the Blue was a senior rank of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major ...

. After several more promotions, he died in 1860 with the rank of Admiral of the Red, and the honorary title

A title is one or more words used before or after a person's name, in certain contexts. It may signify either generation, an official position, or a professional or academic qualification. In some languages, titles may be inserted between the f ...

of Rear-Admiral of the United Kingdom

The Rear-Admiral of the United Kingdom is a now honorary office generally held by a senior (possibly retired) Royal Navy admiral, though the current incumbent is a retired Royal Marine General. Despite the title, the Rear-Admiral of the Unit ...

.

His life and exploits inspired the naval fiction of 19th- and 20th-century novelists, particularly the fictional characters Horatio Hornblower and Patrick O'Brian

Patrick O'Brian, CBE (12 December 1914 – 2 January 2000), born Richard Patrick Russ, was an English novelist and translator, best known for his Aubrey–Maturin series of sea novels set in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars, and cent ...

's Jack Aubrey

John "Jack" Aubrey , is a fictional character in the Aubrey–Maturin series of novels by Patrick O'Brian. The series portrays his rise from lieutenant to rear admiral in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars. The twenty (and one incomple ...

.

Family

Thomas Cochrane was born at Annsfield, near

Thomas Cochrane was born at Annsfield, near Hamilton Hamilton may refer to:

People

* Hamilton (name), a common British surname and occasional given name, usually of Scottish origin, including a list of persons with the surname

** The Duke of Hamilton, the premier peer of Scotland

** Lord Hamilt ...

, South Lanarkshire

gd, Siorrachd Lannraig a Deas

, image_skyline =

, image_flag =

, image_shield = Arms_slanarkshire.jpg

, image_blank_emblem = Slanarks.jpg

, blank_emblem_type = Council logo

, image_map ...

, Scotland. He was the son of Archibald, Lord Cochrane (1748-1831), who later became, in October 1778, The 9th Earl of Dundonald, and his wife, Anna Gilchrist. She was the daughter of Captain James Gilchrist and Ann Roberton, the daughter of Major John Roberton, 16th Laird

Laird () is the owner of a large, long-established Scottish estate. In the traditional Scottish order of precedence, a laird ranked below a baron and above a gentleman. This rank was held only by those lairds holding official recognition in ...

of Earnock.

Thomas, Lord Cochrane, as he himself became in October 1778, had six brothers. Two served with distinction in the military: William Erskine Cochrane of the 15th Dragoons, who served under Sir John Moore in the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

and reached the rank of major; and Archibald Cochrane, who became a captain in the Navy.

Lord Cochrane was descended from lines of Scottish aristocracy and military service on both sides of his family. Through his uncle, Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, the sixth son of The 8th Earl of Dundonald, Cochrane was cousin to his namesake, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Thomas John Cochrane (1789-1872). Sir Thomas J. Cochrane also had a naval career and was appointed as Governor of Newfoundland and later Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom

The Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom is an honorary office generally held by a senior Royal Navy admiral. The title holder is the official deputy to the Lord High Admiral, an honorary (although once operational) office which was vested in th ...

. By 1793 the family fortune had been spent, and the family estate was sold to cover debts.

Early life

Lord Cochrane spent much of his early life inCulross

Culross (/ˈkurəs/) (Scottish Gaelic: ''Cuileann Ros'', 'holly point or promontory') is a village and former royal burgh, and parish, in Fife, Scotland.

According to the 2006 estimate, the village has a population of 395. Originally, Culross ...

, Fife

Fife (, ; gd, Fìobha, ; sco, Fife) is a council area, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries with Perth and Kinross (i ...

, where his family had an estate.

Through the influence of his uncle Alexander Cochrane

Admiral of the Blue Sir Alexander Inglis Cochrane (born Alexander Forrester Cochrane; 23 April 1758 – 26 January 1832) was a senior Royal Navy commander during the Napoleonic Wars and achieved the rank of admiral.

He had previously captain ...

, he was listed as a member of the crew on the books of four Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

ships starting when he was five years old. This common (though unlawful) practice called ''false muster'' was a means of acquiring the years of service required for promotion, if and when he joined the Navy. His father secured him a commission in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

at an early age, but Cochrane preferred the Navy. He joined it in 1793 upon the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

.Cordingley, p.21.

Service in the Royal Navy

French Revolutionary wars

On 23 July 1793, aged 17, Cochrane joined the navy as a midshipman, spending his first months atSheerness

Sheerness () is a town and civil parish beside the mouth of the River Medway on the north-west corner of the Isle of Sheppey in north Kent, England. With a population of 11,938, it is the second largest town on the island after the nearby town ...

in the 28-gun sixth-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a sixth-rate was the designation for small warships mounting between 20 and 28 carriage-mounted guns on a single deck, sometimes with smaller guns on the upper works and ...

frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

commanded by his uncle Captain Alexander Cochrane

Admiral of the Blue Sir Alexander Inglis Cochrane (born Alexander Forrester Cochrane; 23 April 1758 – 26 January 1832) was a senior Royal Navy commander during the Napoleonic Wars and achieved the rank of admiral.

He had previously captain ...

. He transferred to the 38-gun fifth rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a fifth rate was the second-smallest class of warships in a hierarchical system of six " ratings" based on size and firepower.

Rating

The rating system in the Royal N ...

, also under his uncle's command. While aboard ''Thetis,'' he visited Norway and next served on the North America Station

The North America and West Indies Station was a formation or command of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy stationed in North American waters from 1745 to 1956. The North American Station was separate from the Jamaica Station until 1830 when the t ...

.Cordingley, pp.22–24. In 1795, he was appointed acting

Acting is an activity in which a story is told by means of its enactment by an actor or actress who adopts a character—in theatre, television, film, radio, or any other medium that makes use of the mimetic mode.

Acting involves a broad r ...

lieutenant. The following year on 27 May 1796, he was commissioned lieutenant after passing the examination. After several transfers in North America and a return home in 1798, he was assigned as 8th Lieutenant on Lord Keith's flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

.

During his service on ''Barfleur'', Cochrane was court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

led for showing disrespect to Philip Beaver, the ship's first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a s ...

. The board reprimanded him for flippancy. This was the first public manifestation of a pattern of Cochrane being unable to get along with many of his superiors, subordinates, employers, and colleagues in several navies and Parliament, even those with whom he had much in common and who should have been natural allies. His behaviour led to a long enmity with Admiral of the Fleet The 1st Earl of St Vincent.

In February 1800, Cochrane commanded the prize crew taking the captured French vessel to the British base at Mahón. The ship was almost lost in a storm, with Cochrane and his brother Archibald going aloft in place of crew who were mostly ill. Cochrane was promoted to commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

and took command of the brig sloop

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

on 28 March 1800. Later that year, a Spanish warship disguised as a merchant ship almost captured him. He escaped by flying a Danish flag and fending off a boarding by claiming that his ship was plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pe ...

-ridden. On another occasion, he was being chased by an enemy frigate and knew that it would follow him in the night by any glimmer of light from ''Speedy'', so he placed a lantern on a barrel and let it float away. The enemy frigate followed the light and ''Speedy'' escaped.

In February 1801 at Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, Cochrane got into an argument with a French Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

officer at a fancy dress ball. He had come dressed as a common sailor, and the Royalist mistook him for one. This argument led to Cochrane's only duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon Code duello, rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the r ...

. Cochrane wounded the French officer with a pistol shot and was himself unharmed.

One of his most notable exploits was the capture of the Spanish

One of his most notable exploits was the capture of the Spanish xebec

A xebec ( or ), also spelled zebec, was a Mediterranean sailing ship that was used mostly for trading. Xebecs had a long overhanging bowsprit and aft-set mizzen mast. The term can also refer to a small, fast vessel of the sixteenth to nineteenth ...

frigate on 6 May 1801. ''El Gamo'' carried 32 guns and 319 men, compared with ''Speedy''s 14 guns and 54 men. Cochrane flew an American flag and approached so closely to ''El Gamo'' that her guns could not depress to fire on ''Speedy''s hull. The Spanish tried to board and take over the ship but, whenever they were about to board, Cochrane pulled away briefly and fired on the concentrated boarding parties with his ship's guns. Eventually, Cochrane boarded ''El Gamo'' and captured her, despite being outnumbered about six to one.

In ''Speedy''s 13-month cruise, Cochrane captured, burned, or drove ashore 53 ships before three French ships of the line under Admiral Charles-Alexandre Linois captured him on 3 July 1801. While Cochrane was held as a prisoner, Linois often asked him for advice. In his autobiography, Cochrane recounted how courteous and polite the French officer had been. A few days later, he was exchanged for the second captain of another French ship. On 8 August 1801, he was promoted to the rank of post-captain

Post-captain is an obsolete alternative form of the rank of Captain (Royal Navy), captain in the Royal Navy.

The term served to distinguish those who were captains by rank from:

* Officers in command of a naval vessel, who were (and still are) ...

.

Napoleonic Wars

After the

After the Peace of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it se ...

, Cochrane attended the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

. Upon the resumption of war in 1803, St Vincent assigned him in October 1803 to command the sixth-rate 22-gun . Cochrane alleged that the vessel handled poorly, colliding with Royal Navy ships on two occasions (''Bloodhound'' and ''Abundance''). In his autobiography, he compared ''Arab'' to a collier. He wrote that his first thoughts on seeing ''Arab'' being repaired at Plymouth were that she would "sail like a haystack".''Cochrane Britannia's Sea Wolf,'' Thomas, p. 82 Despite this, he intercepted and boarded the American merchant ship ''Chatham.'' This created an international incident, as Britain was not at war with the United States. ''Arab'' and her commander were assigned to protect Britain's important whaling fleet beyond Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

.

In 1804, Lord St Vincent stood aside for the incoming new government led by William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ire ...

, and The 1st Viscount Melville took office. In December of that year, Cochrane was appointed to command of the new 32-gun frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

. He undertook a series of notable exploits over the following eighteen months one of which was a cruise in the vicinity of the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

. Here ''Pallas'' captured three Spanish merchant ships and a Spanish 14-gun privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

.

In August 1806, he took command of the 38-gun frigate , formerly the Spanish frigate ''Medea''. One of his midshipmen was Frederick Marryat

Captain Frederick Marryat (10 July 1792 – 9 August 1848) was a Royal Navy officer, a novelist, and an acquaintance of Charles Dickens. He is noted today as an early pioneer of nautical fiction, particularly for his semi-autobiographical novel ...

, who later wrote fictionalised accounts of his adventures with Cochrane.

In ''Imperieuse'', Cochrane raided the Mediterranean coast of France during the continuing Napoleonic Wars. In 1808, Cochrane and a Spanish guerrilla force captured the fortress of Mongat, which straddled the road between Gerona and Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

. This delayed General Duhesme

Guillaume Philibert, 1st Count Duhesme (7 July 1766 in Mercurey (formerly ''Bourgneuf''), Burgundy – 20 June 1815 near Waterloo) was a French general during the Napoleonic Wars.

Revolution

Duhesme studied law and in 1792 was made colonel o ...

's French army for a month. On another raid, Cochrane copied code books from a signal station, leaving behind the originals so that the French would believe them uncompromised. When ''Imperieuse'' ran short of water, she sailed up the estuary of the Rhone to replenish. A French army marched into Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

and besieged Rosas, and Cochrane took part in the defence of the town. He occupied and defended Fort Trinidad ( Castell de la Trinitat) for a number of weeks before the fall of the city forced him to leave; Cochrane was one of the last two men to quit the fort.

While captain of ''Speedy'', ''Pallas'', and ''Imperieuse'', Cochrane became an effective practitioner of coastal warfare during the period. He attacked shore installations such as the Martello tower

Martello towers, sometimes known simply as Martellos, are small defensive forts that were built across the British Empire during the 19th century, from the time of the French Revolutionary Wars onwards. Most were coastal forts.

They stand u ...

at Son Bou on Menorca

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its capi ...

, and he captured enemy ships in harbour by leading his men in boats in "cutting out" operations. He was a meticulous planner of every operation, which limited casualties among his men and maximised the chances of success.

In 1809, Cochrane commanded the attack by a flotilla of fire ship

A fire ship or fireship, used in the days of wooden rowed or sailing ships, was a ship filled with combustibles, or gunpowder deliberately set on fire and steered (or, when possible, allowed to drift) into an enemy fleet, in order to destroy sh ...

s on Rochefort

Rochefort () may refer to:

Places France

* Rochefort, Charente-Maritime, in the Charente-Maritime department

** Arsenal de Rochefort, a former naval base and dockyard

* Rochefort, Savoie in the Savoie department

* Rochefort-du-Gard, in the Ga ...

, as part of the Battle of the Basque Roads

The Battle of the Basque Roads, also known as the Battle of Aix Roads (French: ''Bataille de l'île d'Aix'', also ''Affaire des brûlots'', rarely ''Bataille de la rade des Basques''), was a major naval battle of the Napoleonic Wars, fought in th ...

. The attack did considerable damage, but Cochrane blamed fleet commander Admiral Gambier for missing the opportunity to destroy the French fleet, accusations that resulted in the Court-martial of James, Lord Gambier

The Court-martial of James, Lord Gambier, was a notorious British naval legal case during the summer of 1809, in which Admiral Lord Gambier requested a court-martial to examine his behaviour during the Battle of Basque Roads in April of the same ...

. Cochrane claimed that, as a result of expressing his opinion publicly, the admiralty denied him the opportunity to serve afloat. But documentation shows that he was focused on politics at this time and, indeed, refused a number of offers of command.

Political career

In June 1806, Lord Cochrane stood for theHouse of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

on a ticket of parliamentary reform (a movement which later brought about the Reform Acts

In the United Kingdom, Reform Act is most commonly used for legislation passed in the 19th century and early 20th century to enfranchise new groups of voters and to redistribute seats in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. ...

) for the potwalloper

A potwalloper (sometimes potwalloner or potwaller) or householder borough was a parliamentary borough in which the franchise was extended to the male head of any household with a hearth large enough to boil a cauldron (or "wallop a pot").Edwar ...

borough of Honiton

Honiton ( or ) is a market town and civil parish in East Devon, situated close to the River Otter, north east of Exeter in the county of Devon. Honiton has a population estimated at 11,822 (based on mid-year estimates for the two Honiton Ward ...

in Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

. This was exactly the kind of borough which Cochrane proposed to abolish; votes were mostly sold to the highest bidder. Cochrane offered nothing and lost the election. In October 1806, he ran for Parliament in Honiton and won. Cochrane initially denied that he paid any bribes, but he revealed in a Parliamentary debate ten years later that he had paid ten guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from the Guinea region in West Africa, from where m ...

(£10 10s) per voter through Mr. Townshend, local headman and banker.

In May 1807, Cochrane was elected by

In May 1807, Cochrane was elected by Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

in a more democratic election. He had campaigned for parliamentary reform, allied with such Radicals as William Cobbett

William Cobbett (9 March 1763 – 18 June 1835) was an English pamphleteer, journalist, politician, and farmer born in Farnham, Surrey. He was one of an agrarian faction seeking to reform Parliament, abolish "rotten boroughs", restrain foreign ...

, Sir Francis Burdett

Sir Francis Burdett, 5th Baronet (25 January 1770 – 23 January 1844) was a British politician and Member of Parliament who gained notoriety as a proponent (in advance of the Chartists) of universal male suffrage, equal electoral districts, vo ...

, and Henry Hunt. His outspoken criticism of the conduct of the war and the corruption in the navy made him powerful enemies in the government. His criticism of Admiral Gambier's conduct at the Battle of the Basque Roads

The Battle of the Basque Roads, also known as the Battle of Aix Roads (French: ''Bataille de l'île d'Aix'', also ''Affaire des brûlots'', rarely ''Bataille de la rade des Basques''), was a major naval battle of the Napoleonic Wars, fought in th ...

was so severe that Gambier demanded a court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

to clear his name. Cochrane made important enemies in the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

during this period.

In 1810, Sir Francis Burdett

Sir Francis Burdett, 5th Baronet (25 January 1770 – 23 January 1844) was a British politician and Member of Parliament who gained notoriety as a proponent (in advance of the Chartists) of universal male suffrage, equal electoral districts, vo ...

, a member of parliament and political ally, had barricaded himself in his home at Piccadilly

Piccadilly () is a road in the City of Westminster, London, to the south of Mayfair, between Hyde Park Corner in the west and Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is part of the A4 road that connects central London to Hammersmith, Earl's Court, ...

, London, resisting arrest by the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

. Cochrane went to assist Burdett's defence of the house. His approach was similar to what he used in the navy and would have led to numerous deaths amongst the arresting officers and at least partial destruction of Burdett's house, along with much of Piccadilly. On realising what Cochrane planned, Burdett and his allies took steps to end the siege.

Cochrane was popular with the public but was unable to get along with his colleagues in the House of Commons or within the government. He usually had little success in promoting his causes. An exception was his successful confrontation of a prize court in 1814.

His conviction in the Great Stock Exchange Fraud of 1814

The Great Stock Exchange Fraud of 1814 was a hoax or fraud centered on false information about the Napoleonic Wars, affecting the London Stock Exchange in 1814.

The du Bourg hoax

On the morning of Monday, 21 February 1814, a uniformed man posing ...

resulted in Parliament expelling him on 5 July 1814. However, his constituents in the seat of Westminster re-elected him at the resulting by-election on 16 July. He held this seat until 1818. In 1818, Cochrane's last speech in Parliament advocated parliamentary reform.

In 1830, Cochrane initially expressed interest in running for Parliament but then declined. Lord Brougham's brother had decided to run for the seat, and Cochrane also thought that it would look bad for him to be publicly supporting a government from which he sought pardon for his fraud conviction.

In 1831, his father died and Cochrane became the 10th Earl of Dundonald

Earl of Dundonald is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1669 for the Scottish soldier and politician William Cochrane, 1st Lord Cochrane of Dundonald, along with the subsidiary title of Lord Cochrane of Paisley and Ochiltre ...

. As such, he was no longer entitled to sit in the Commons.

While serving as the Commander-in-Chief of the North America and West Indies Station, Cochrane became acquainted with geologist and physicist Abraham Gesner

Abraham Pineo Gesner, ONB (; May 2, 1797 – April 29, 1864) was a Canadian physician and geologist who invented kerosene. Gesner was born in Cornwallis, Nova Scotia (now called Chipmans Corner) and lived much of his life in Saint John, New Bru ...

in Halifax. The pair planned a commercial venture that would supply Halifax with lamp oil and mine bitumen

Asphalt, also known as bitumen (, ), is a sticky, black, highly viscous liquid or semi-solid form of petroleum. It may be found in natural deposits or may be a refined product, and is classed as a pitch. Before the 20th century, the term a ...

deposits in Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

and Albert Country, New Brunswick. By 1850, Cochrane had purchased all the land surrounding Trinidad's pitch lake in support of the endeavour. Ultimately, the enterprise did not come into fruition, and Cochrane returned to England after his term of service expired in April 1851.

Marriage and children

In 1812, Cochrane married Katherine ("Katy") Frances Corbet Barnes, a beautiful orphan who was about twenty years his junior. They met through Cochrane's cousin Nathaniel Day Cochrane. This was an elopement and a civil ceremony, due to the opposition of his wealthy uncleBasil Cochrane

Basil Cochrane (22 April 1753 – 12 or 14 August 1826 in Paris, France) was a Scottish civil servant, businessman, inventor, and wealthy nabob of early-19th-century England.

Early life

The sixth son of Scottish nobleman and politician Thomas ...

, who disinherited his nephew as a result. Cochrane called Katherine "Kate," "Kitty," or "Mouse" in letters to her; she often accompanied her husband on his extended campaigns in South America and Greece.

Cochrane and Katherine remarried in the Anglican Church

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

in 1818, and in the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

in 1825. They had six children:

* Thomas Barnes Cochrane, 11th Earl of Dundonald

Thomas Barnes Cochrane, 11th Earl of Dundonald (14 April 1814 – 15 January 1885) was a Scottish people, Scottish nobleman. He was son of the radical politician and sailor Thomas Cochrane, 10th Earl of Dundonald. As a child he accompanied his fat ...

, b. 18 April 1814, m. Louisa Harriett McKinnon.

* William Horatio Bernardo Cochrane, officer, 92nd Gordon Highlanders

Gordon may refer to:

People

* Gordon (given name), a masculine given name, including list of persons and fictional characters

* Gordon (surname), the surname

* Gordon (slave), escaped to a Union Army camp during the U.S. Civil War

* Clan Gord ...

, b. 8 March 1818 m. Jacobina Frances Nicholson d. 6 February 1900.

* Elizabeth Katharine Cochrane, died close to her first birthday.

* Katharine Elizabeth Cochrane, d. 25 August 1869, m. John Willis Fleming.

* Admiral Sir Arthur Auckland Leopold Pedro Cochrane KCB (Commander of ), b. 24 September 1824, d. 20 August 1905.

* Captain Ernest Gray Lambton Cochrane RN (High Sheriff of Donegal

The High Sheriff of Donegal was the British Crown's judicial representative in County Donegal in Ulster, Ireland, from the late 16th century until 1922, when the office was abolished in the new Irish Free State and replaced by the office of Doneg ...

) b. 4 June 1834, d. 2 February 1911 m. 1. Adelaide Blackall 2. Elizabeth Frances Maria Katherine Doherty.

The confusion of multiple ceremonies led to suspicions that Cochrane's first son Thomas Barnes Cochrane was illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as ''b ...

. Investigation of this delayed Thomas's accession to the Earldom of Dundonald on his father's death.

In 1823 Lady Cochrane sailed with her children to Valparaiso on to join her husband. On 13 June ''Sesostris'' stopped at Rio de Janeiro where she discovered that he was there, having in March taken command of the Brazilian Navy.

Following Cochrane's return from Greece, the couple disagreed about his spending on inventions and her spending on socialising, which led to their separation in 1839. Katherine moved to Boulogne-sur-Mer

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the ...

with a generous allowance, occasionally visiting London but never staying with her husband. She died in Bolougne in 1865, aged 69.

Great Stock Exchange Fraud

In February 1814, rumours began to circulate of Napoleon's death. The claims were seemingly confirmed by a man in a redstaff officer

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military ...

's uniform identified as Colonel de Bourg, aide-de-camp to Lord Cathcart

Earl Cathcart is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom.

History

The title was created in 1814 for the soldier and diplomat William Cathcart, 1st Viscount Cathcart. The Cathcart family descends from Sir Alan Cathcart, who sometime be ...

, the British ambassador to Russia. He arrived in Dover from France on 21 February bearing news that Napoleon had been captured and killed by Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

.Vale (2004) p.74. Share prices rose sharply on the Stock Exchange

A stock exchange, securities exchange, or bourse is an exchange where stockbrokers and traders can buy and sell securities, such as shares of stock, bonds and other financial instruments. Stock exchanges may also provide facilities for th ...

in reaction to the news and the possibility of peace, particularly in volatile partly-paid government securities called Omniums, which increased from to 32. However, it soon became clear that the news of Napoleon's death was a hoax. The Stock Exchange established a sub-committee to investigate, and they discovered that six men had sold substantial amounts of Omnium stock during the boom in value. The committee assumed that all six were responsible for the hoax and subsequent fraud. Cochrane had disposed of his entire £139,000 holding in Omnium () – which he had only acquired a month before – and was named as one of the six conspirators, as were his uncle Andrew Cochrane-Johnstone and his stockbroker, Richard Butt. Within days, an anonymous informant told the committee that Colonel de Bourg was an imposter: he was a Prussian aristocrat named Charles Random de Berenger. He had also been seen entering Cochrane's house on the day of the hoax.

The accused were brought to trial in the

The accused were brought to trial in the Court of King's Bench

The King's Bench (), or, during the reign of a female monarch, the Queen's Bench ('), refers to several contemporary and historical courts in some Commonwealth jurisdictions.

* Court of King's Bench (England), a historic court court of common ...

, Guildhall

A guildhall, also known as a "guild hall" or "guild house", is a historical building originally used for tax collecting by municipalities or merchants in Great Britain and the Low Countries. These buildings commonly become town halls and in som ...

on 8 June 1814. The trial was presided over by Lord Ellenborough

Baron Ellenborough, of Ellenborough in the County of Cumberland, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 19 April 1802 for the lawyer, judge and politician Sir Edward Law, Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench from ...

, a High Tory

In the United Kingdom and elsewhere, High Toryism is the old traditionalist conservatism which is in line with the Toryism originating in the 17th century. High Tories and their worldview are sometimes at odds with the modernising elements of the ...

and a notable enemy of the radicals, who had previously convicted and sentenced to prison radical politicians William Cobbett

William Cobbett (9 March 1763 – 18 June 1835) was an English pamphleteer, journalist, politician, and farmer born in Farnham, Surrey. He was one of an agrarian faction seeking to reform Parliament, abolish "rotten boroughs", restrain foreign ...

and Henry Hunt in politically motivated trials. The evidence against Cochrane was circumstantial and hinged on the nature of his share dealings, his contacts with the conspirators, and the colour of uniform which De Berenger had been wearing when they met in his house. Cochrane admitted that he was acquainted with De Berenger and that the man had visited his home on the day of the fraud, but insisted that he had arrived wearing a green sharpshooter's uniform rather than the red uniform worn by the person who claimed to be de Bourg. Cochrane said that De Berenger had visited to request passage to the United States aboard Cochrane's new command . Cochrane's servants agreed, in an affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or '' deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by law. Such a statemen ...

created before the trial, that the collar of the uniform above De Berenger's greatcoat had been green. However, they admitted to Cochrane's solicitors that they thought the rest had been red. They were not called at trial to give evidence. The prosecution summoned as key witness hackney carriage driver William Crane, who swore that De Berenger was wearing a scarlet uniform when he delivered him to the house. Cochrane's defence also argued that he had given standing instructions to Butt that his Omnium shares were to be sold if the price rose by 1 per cent, and he would have made double profit if he waited until it reached its peak price.

On the second day of the trial, Lord Ellenborough began his summary of the evidence and drew attention to the matter of De Berenger's uniform; he concluded that witnesses had provided damning evidence.Cordingly p.250. The jury retired to deliberate and returned a verdict of guilty against all the defendants two and a half hours later. Belatedly, Cochrane's defence team found several witnesses who were willing to testify that De Berenger had arrived wearing a green uniform, but Lord Ellenborough dismissed their evidence as inadmissible because two of the conspirators had fled the country upon hearing the guilty verdict. On 20 June 1814, Cochrane was sentenced to 12 months' imprisonment, fined £1,000, and ordered to stand in the pillory opposite the Royal Exchange for one hour. In subsequent weeks, he was dismissed from the Royal Navy by the Admiralty and expelled from Parliament following a motion

In physics, motion is the phenomenon in which an object changes its position with respect to time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed and frame of reference to an observer and mea ...

in the House of Commons which was passed by 144 votes to 44. On the orders of the Prince Regent

A prince regent or princess regent is a prince or princess who, due to their position in the line of succession, rules a monarchy as regent in the stead of a monarch regnant, e.g., as a result of the sovereign's incapacity (minority or illness ...

, Cochrane was humiliated by the loss of his appointment Knight of the Order of the Bath in a degradation ceremony

Cashiering (or degradation ceremony), generally within military forces, is a ritual dismissal of an individual from some position of responsibility for a breach of discipline.

Etymology

From the Flemish (to dismiss from service; to discard _...

_at_Westminster_Abbey._His_Heraldic_flag.html" "title="Westminster_Abbey.html" ;"title=" ...was taken down and physically kicked out of the chapel and down the outside steps. But, within a month, Cochrane was re-elected unopposed as the Member of Parliament for Westminster. Following a public outcry, his sentence to the pillory was rescinded for fears that it would lead to the outbreak of a riot.Cordingly p.251. The question of Cochrane's innocence or guilt created much debate at the time, and it has divided historians ever since. Subsequent reviews of the trial carried out by three Lord Chancellors during the course of the 19th century concluded that Cochrane should have been found not guilty on the basis of the evidence produced in court. Cochrane maintained his innocence for the rest of his life and campaigned tirelessly to restore his damaged reputation and to clear his name. He believed that the trial was politically motivated and that a "higher authority than the Stock Exchange" was responsible for his prosecution. A series of petitions put forward by Cochrane protesting his innocence were ignored until 1830. That year, King

George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from the death of his father, King George III, on 29 January 1820, until his own death ten y ...

(the former Prince Regent) died and was succeeded by William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded h ...

. He had served in the Royal Navy and was sympathetic to Cochrane's cause.Cordingly p.334. Later that year, the Tory government fell and was replaced by a Whig government in which his friend Lord Brougham

Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, (; 19 September 1778 – 7 May 1868) was a British statesman who became Lord High Chancellor and played a prominent role in passing the 1832 Reform Act and 1833 Slavery Abolition Act. ...

was appointed Lord Chancellor. Following a meeting of the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

in May 1832, Cochrane was granted a pardon and restored to the Navy List

A Navy Directory, formerly the Navy List or Naval Register is an official list of naval officers, their ranks and seniority, the ships which they command or to which they are appointed, etc., that is published by the government or naval autho ...

with a promotion to rear-admiral.Cordingly p.335. Support from friends in the government and the writings of popular naval authors such as Frederick Marryat

Captain Frederick Marryat (10 July 1792 – 9 August 1848) was a Royal Navy officer, a novelist, and an acquaintance of Charles Dickens. He is noted today as an early pioneer of nautical fiction, particularly for his semi-autobiographical novel ...

and Maria Graham increased public sympathy for Cochrane's situation. Cochrane's knighthood was restored in May 1847 with the personal intervention of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

, and he was appointed Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) as one ...

. Only in 1860 was his banner returned to Westminster Abbey; it was the day before his funeral.

In 1876, his grandson received a payment of £40,000 from the British government (), based on the recommendations of a Parliamentary select committee, in compensation for Cochrane's conviction. The committee had concluded that his conviction was unjust.

Service with other navies

Chilean Navy

Lord Cochrane left the UK in official disgrace, but that did not end his naval career. In 1817, Lord Cochrane placed a notice in one of the leading London newspapers that he was available to go and serve the newly becoming independent nations in

Lord Cochrane left the UK in official disgrace, but that did not end his naval career. In 1817, Lord Cochrane placed a notice in one of the leading London newspapers that he was available to go and serve the newly becoming independent nations in America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

or others.

But in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, in 1818, he was met by the representative sent by General José de San Martín

José Francisco de San Martín y Matorras (25 February 177817 August 1850), known simply as José de San Martín () or '' the Liberator of Argentina, Chile and Peru'', was an Argentine general and the primary leader of the southern and cent ...

, José Antonio Álvarez Condarco, who convinced him in May to join the cause for the hispanoamerican independence and go to Chile together alongside a number of British officers who also wanted to be hired. Accompanied by Lady Cochrane and their two children, he reached Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

on 28 November 1818. Chile was rapidly organising its new navy for its war of independence.

Cochrane became a Chilean citizen, on 11 December 1818 at the request of Chilean leader Bernardo O'Higgins

Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme (; August 20, 1778 – October 24, 1842) was a Chilean independence leader who freed Chile from Spanish rule in the Chilean War of Independence. He was a wealthy landowner of Basque-Spanish and Irish ancestry. Althou ...

. He was appointed Vice Admiral and took command of the Chilean Navy

The Chilean Navy ( es, Armada de Chile) is the naval warfare service branch of the Chilean Armed Forces. It is under the Ministry of National Defense. Its headquarters are at Edificio Armada de Chile, Valparaiso.

History

Origins and the War ...

in Chile's war of independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars). These wars may or may not have been successful in achieving a goal of independence.

List

See also

* Lists of active separatist movements

* List of civil wars

* List o ...

against Spain. He was the first Vice Admiral of Chile.Brian Vale, ''Cochrane in the Pacific'', I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2008, Cochrane reorganised the Chilean navy with British commanders, introducing British naval customs and, formally, English-speaking governance in their warships. He took command in the frigate and blockaded and raided the coasts of Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

, as he had those of France and Spain. On his own initiative, he organised and led the capture of Valdivia

The Capture of Valdivia ( es, Toma de Valdivia) was a battle in the Chilean War of Independence between Royalist forces commanded by Colonel Manuel Montoya and Fausto del Hoyo and the Patriot forces under the command of Thomas Cochrane and J ...

, despite only having 300 men and two ships to deploy against seven large forts. He failed in his attempt to capture the Chiloé Archipelago

The Chiloé Archipelago ( es, Archipiélago de Chiloé, , ) is a group of islands lying off the coast of Chile, in the Los Lagos Region. It is separated from mainland Chile by the Chacao Channel in the north, the Sea of Chiloé in the east and t ...

for Chile.

José de San Martín

José Francisco de San Martín y Matorras (25 February 177817 August 1850), known simply as José de San Martín () or '' the Liberator of Argentina, Chile and Peru'', was an Argentine general and the primary leader of the southern and cent ...

to Peru, blockade the coast, and support the campaign for independence. Later, forces under Cochrane's personal command cut out and captured the frigate , the most powerful Spanish ship in South America. All of this led to Peruvian independence, which O'Higgins considered indispensable to Chile's security. Cochrane's victories in the Pacific were spectacular and important. The excitement was almost immediately marred by his accusations that he had been plotted against by subordinates and treated with contempt and denied adequate financial reward by his superiors. The evidence does not support these accusations, and the problem appeared to lie in Cochrane's own suspicious and uneasy personality. Cochrane had an uneasy relation with San Martín who was serene and calculating in contrast with Cochrane's tendency for audacious actions. San Martín criticized Cochrane's interest for financial gain giving him the nickname ''El Metálico Lord'' (The Metallic Lord).

Loose words from his wife Katy resulted in a rumour that Cochrane had made plans to free Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

from his exile on Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

and make him ruler of a unified South American state. This could not have been true because Charles, the supposed envoy bearing the rumoured plans, had been killed two months before his reported "departure to Europe". Cochrane left the service of the Chilean Navy on 29 November 1822.

Chilean naval vessels named after Lord Cochrane

The Chilean Navy has named five ships ''Cochrane'' or ''Almirante Cochrane'' (Admiral Cochrane) in his honour: * The first, , was abattery ship

The central battery ship, also known as a centre battery ship in the United Kingdom and as a casemate ship in European continental navies, was a development of the (high-freeboard) broadside ironclad of the 1860s, given a substantial boost due t ...

that fought in the War of the Pacific

The War of the Pacific ( es, link=no, Guerra del Pacífico), also known as the Saltpeter War ( es, link=no, Guerra del salitre) and by multiple other names, was a war between Chile and a Bolivian–Peruvian alliance from 1879 to 1884. Fought ...

(1879–1884).

* The second ''Almirante Cochrane'' was a dreadnought

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

battleship laid down in Britain in 1913. The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

acquired the unfinished ship in 1917, converting her into the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

.

* The third ship, , was a , the former , commissioned into the Chilean Navy in 1962 and scrapped in 1983.

* The fourth ship, , was a , the former , which the Chilean Navy acquired in 1984 and decommissioned in 2006.

* The fifth and current ship to bear the name, , is a Type 23 frigate

The Type 23 frigate or Duke class is a class of frigates built for the United Kingdom's Royal Navy. The ships are named after British Dukes, thus leading to the class being commonly known as the Duke class. The first Type 23, , was commission ...

, the former , which the Chilean Navy commissioned in 2006.

Imperial Brazilian Navy

Brazil was fighting its ownwar of independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars). These wars may or may not have been successful in achieving a goal of independence.

List

See also

* Lists of active separatist movements

* List of civil wars

* List o ...

against Portugal. In 1822, the southern provinces (except Montevideo

Montevideo () is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

, now in Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

) came under the control of the patriots led by the Prince Regent, later Emperor Pedro I

Dom Pedro I (English: Peter I; 12 October 1798 – 24 September 1834), nicknamed "the Liberator", was the founder and first ruler of the Empire of Brazil. As King Dom Pedro IV, he reigned briefly over Portugal, where he also became ...

. Portugal still controlled some important provincial capitals in the north, with major garrisons and naval bases such as Belém

Belém (; Portuguese for Bethlehem; initially called Nossa Senhora de Belém do Grão-Pará, in English Our Lady of Bethlehem of Great Pará) often called Belém of Pará, is a Brazilian city, capital and largest city of the state of Pará in t ...

do Pará, Salvador da Bahia

Salvador (English: ''Savior'') is a Brazilian municipality and capital city of the state of Bahia. Situated in the Zona da Mata in the Northeast Region of Brazil, Salvador is recognized throughout the country and internationally for its cuisi ...

, and São Luís do Maranhão

SAO or Sao may refer to:

Places

* Sao civilisation, in Middle Africa from 6th century BC to 16th century AD

* Sao, a town in Boussé Department, Burkina Faso

* Saco Transportation Center (station code SAO), a train station in Saco, Maine, U ...

.

Lord Cochrane took command of the Imperial Brazilian Navy

The Imperial Brazilian Navy (Portuguese: ''Armada Nacional'', commonly known as ''Armada Imperial'') was the navy created at the time of the independence of the Empire of Brazil from the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. It exis ...

on 21 March 1823 as was appointed "First Admiral of the National and Imperial Navy" at the flagship '' Pedro I''. He blockaded the Portuguese in Bahia

Bahia ( , , ; meaning "bay") is one of the 26 Federative units of Brazil, states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after São Paulo (sta ...

, confronted them at the Battle of 4 May, and forced them to evacuate the province in a vast convoy of ships which Cochrane's men attacked as they crossed the Atlantic. Cochrane sailed to Maranhão

Maranhão () is a state in Brazil. Located in the country's Northeast Region, it has a population of about 7 million and an area of . Clockwise from north, it borders on the Atlantic Ocean for 2,243 km and the states of Piauí, Tocantins and ...

(then spelled Maranham) on his own initiative and bluffed the garrison into surrender by claiming that a vast (and mythical) Brazilian fleet and army were over the horizon. He sent subordinate Captain John Pascoe Grenfell

John Pascoe Grenfell (20 September 1800 – 20 March 1869) was a British officer of the Empire of Brazil. He spent most of his service in South America campaigns, initially under the leadership of Lord Cochrane and then Commodore Norton. He was ...

to Belém

Belém (; Portuguese for Bethlehem; initially called Nossa Senhora de Belém do Grão-Pará, in English Our Lady of Bethlehem of Great Pará) often called Belém of Pará, is a Brazilian city, capital and largest city of the state of Pará in t ...

do Pará to use the same bluff and extract a Portuguese surrender. As a result of Cochrane's efforts, Brazil became totally ''de facto'' independent and free of any Portuguese troops. On Cochrane's return to Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

in 1824, Emperor Pedro I

Dom Pedro I (English: Peter I; 12 October 1798 – 24 September 1834), nicknamed "the Liberator", was the founder and first ruler of the Empire of Brazil. As King Dom Pedro IV, he reigned briefly over Portugal, where he also became ...

rewarded the officer by granting him the non-hereditary title of Marquess of Maranhão (''Marquês do Maranhão'') in the Empire of Brazil

The Empire of Brazil was a 19th-century state that broadly comprised the territories which form modern Brazil and (until 1828) Uruguay. Its government was a representative parliamentary constitutional monarchy under the rule of Emperors Dom Pe ...

. He was also awarded an accompanying coat of arms.

As in Chile and earlier occasions, Cochrane's joy at these successes was rapidly replaced by quarrels over pay and prize money, and an accusation that the Brazilian authorities were plotting against him.

In mid-1824, Cochrane sailed north with a squadron to assist the Brazilian army under General Francisco Lima e Silva in suppressing a republican rebellion in the state of Pernambuco

Pernambuco () is a state of Brazil, located in the Northeast region of the country. With an estimated population of 9.6 million people as of 2020, making it seventh-most populous state of Brazil and with around 98,148 km², being the 19 ...

which had begun to spread to Maranhão

Maranhão () is a state in Brazil. Located in the country's Northeast Region, it has a population of about 7 million and an area of . Clockwise from north, it borders on the Atlantic Ocean for 2,243 km and the states of Piauí, Tocantins and ...

and other northern states. The rebellion was rapidly extinguished. Cochrane proceeded to Maranhão, where he took over the administration. He demanded the payment of prize money which he claimed he was owed as a result of the recapture of the province in 1823. He absconded with public money and sacked merchant ships anchored in São Luís do Maranhão. Defying orders to return to Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

, Cochrane transferred to a captured Brazilian frigate, left Brazil and returned to Britain where he arrived in late June 1825.

Greek Navy

In August 1825 Cochrane was hired by Greece to support its fight for independence from theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, which had deployed an army raised in Egypt to suppress the Greek rebellion. He took an active role in the campaign between March 1827 and December 1828, but met with limited success. His subordinate Captain Hastings

Captain Arthur J. M. Hastings, OBE, is a fictional character created by Agatha Christie as the companion-chronicler and best friend of the Belgian detective, Hercule Poirot. He is first introduced in Christie's 1920 novel ''The Mysterious Aff ...

attacked Ottoman forces at the Gulf of Lepanto, which indirectly led to intervention by Great Britain, France, and Russia. They succeeded in destroying the Turko–Egyptian fleet at the Battle of Navarino

The Battle of Navarino was a naval battle fought on 20 October (O. S. 8 October) 1827, during the Greek War of Independence (1821–29), in Navarino Bay (modern Pylos), on the west coast of the Peloponnese peninsula, in the Ionian Sea. Allied fo ...

, and the war was ended under mediation of the Great Powers. He resigned his commission toward the end of the war and returned to Britain.

Return to Royal Navy

Lord Cochrane inherited his peerage following his father's death on 1 July 1831, becoming The 10th

Lord Cochrane inherited his peerage following his father's death on 1 July 1831, becoming The 10th Earl of Dundonald

Earl of Dundonald is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1669 for the Scottish soldier and politician William Cochrane, 1st Lord Cochrane of Dundonald, along with the subsidiary title of Lord Cochrane of Paisley and Ochiltre ...

. He was restored to the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

list on 2 May 1832 as a Rear-Admiral of the Blue

The Rear-Admiral of the Blue was a senior rank of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major ...

. The full return of Lord Dundonald, as he was now known, to Royal Navy service was delayed by his refusal to take a command until his knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

had been restored, which took 15 years. He continued to receive promotions in the list of flag officers

A flag officer is a commissioned officer in a nation's armed forces senior enough to be entitled to fly a flag to mark the position from which the officer exercises command.

The term is used differently in different countries:

*In many countries ...

, as follows:

* Rear-Admiral of the Blue

The Rear-Admiral of the Blue was a senior rank of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major ...

on 2 May 1832

* Rear-Admiral of the White

The Rear-Admiral of the White was a senior rank of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first maj ...

on 10 January 1837

* Rear-Admiral of the Red on 28 June 1838

* Vice-Admiral of the Blue

The Vice-Admiral of the Blue was a senior rank of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom, immediately outranked by the rank Vice-Admiral of the White (see order of precedence below). Royal Navy officers currently holding the ranks of commodore, re ...

on 23 November 1841

* Vice-Admiral of the White

The Vice-Admiral of the White was a senior rank of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom, immediately outranked by the rank Vice-Admiral of the Red (see order of precedence below). Royal Navy officers holding the ranks of commodore, rear admira ...

on 9 November 1846

* Vice-Admiral of the Red

Vice-admiral of the Red was a senior rank of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom, immediately outranked by the rank admiral of the Blue (see order of precedence below). Royal Navy officers currently holding the ranks of commodore, rear admira ...

on 3 January 1848

* Admiral of the Blue on 21 March 1851

* Admiral of the White on 2 April 1853

* Admiral of the Red on 8 December 1857

On 22 May 1847, Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

reappointed him Knight of the Order of the Bath. He returned to the Royal Navy, serving as Commander-in-Chief of the North America and West Indies Station

The North America and West Indies Station was a formation or command of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy stationed in North American waters from 1745 to 1956. The North American Station was separate from the Jamaica Station until 1830 when the t ...

from 1848 to 1851. During the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

, the government considered him for a command in the Baltic, but decided that there was too high a chance that Lord Dundonald would risk the fleet in a daring attack. On 6 November 1854, he was appointed to the honorary office of Rear-Admiral of the United Kingdom

The Rear-Admiral of the United Kingdom is a now honorary office generally held by a senior (possibly retired) Royal Navy admiral, though the current incumbent is a retired Royal Marine General. Despite the title, the Rear-Admiral of the Unit ...

, an office that he retained until his death.

In his final years, Lord Dundonald wrote his autobiography in collaboration with G.B. Earp. He twice had to undergo painful surgery for kidney stone

Kidney stone disease, also known as nephrolithiasis or urolithiasis, is a crystallopathy where a solid piece of material (kidney stone) develops in the urinary tract. Kidney stones typically form in the kidney and leave the body in the urine s ...

s in 1860 with his health deteriorating. He died during the second operation on 31 October 1860 in Kensington

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West End of London, West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up b ...

.

Dundonald was buried in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

where his grave is in the central part of the nave. Each year in May, representatives of the Chilean Navy

The Chilean Navy ( es, Armada de Chile) is the naval warfare service branch of the Chilean Armed Forces. It is under the Ministry of National Defense. Its headquarters are at Edificio Armada de Chile, Valparaiso.

History

Origins and the War ...

hold a wreath-laying ceremony at his grave.

Innovations in technology

Convoys were guided by ships following the lamps of those ahead. In 1805, Lord Cochrane entered a Royal Navy competition for a superior convoy lamp. He believed that the judges were biased against him, so he re-entered the contest under another name and won the prize. In 1806, Cochrane had agalley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be used ...

made to his specifications which he carried on board ''Pallas'' and used to attack the French coast. It had the advantage of mobility and flexibility.

In 1812, Lord Cochrane proposed attacking the French coast using a combination of bombardment ships, explosion ships, and "stink vessels" (gas warfare). A bombardment ship consisted of a strengthened old hulk filled with powder and shot and made to list to one side. It was anchored at night to face the enemy behind the harbour wall. When set off, it provided saturation bombardment of the harbour, which would be closely followed by landings of troops. He put the plans forward again before and during the Crimean War. The authorities, however, decided not to pursue his plans.

In 1818, Cochrane patented the tunnelling shield

A tunnelling shield is a protective structure used during the excavation of large, man-made tunnels. When excavating through ground that is soft, liquid, or otherwise unstable, there is a potential health and safety hazard to workers and the pro ...

, together with engineer Marc Isambard Brunel

Sir Marc Isambard Brunel (, ; 25 April 1769 – 12 December 1849) was a French-British engineer who is most famous for the work he did in Britain. He constructed the Thames Tunnel and was the father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Born in Franc ...

, which Brunel and his son used in building the Thames Tunnel