Thatcherism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thatcherism is a form of British conservative ideology named after

Whilst Thatcher was Prime Minister, she greatly embraced

Whilst Thatcher was Prime Minister, she greatly embraced

Critics of Thatcherism claim that its successes were obtained only at the expense of great

Critics of Thatcherism claim that its successes were obtained only at the expense of great

The extent to which one can say Thatcherism has a continuing influence on British political and economic life is unclear. In reference to modern British political culture, it could be said that a "post-Thatcherite consensus" exists, especially in regard to economic policy. In the 1980s, the now defunct

The extent to which one can say Thatcherism has a continuing influence on British political and economic life is unclear. In reference to modern British political culture, it could be said that a "post-Thatcherite consensus" exists, especially in regard to economic policy. In the 1980s, the now defunct

What is Thatcherism? (BBC News Online)

What is Thatcherism? (Britpolitics.co.uk)

{{Use dmy dates, date=February 2021 1970s economic history 1980s economic history 1990s economic history 1970s neologisms British nationalism Conservative Party (UK) factions Eponymous political ideologies Euroscepticism in the United Kingdom Margaret Thatcher Neoliberalism History of the Conservative Party (UK) History of libertarianism Liberal conservatism Libertarian theory Libertarianism in the United Kingdom Politics of the United Kingdom Right-libertarianism Right-wing ideologies Right-wing politics in the United Kingdom Right-wing populism in the United Kingdom

Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

leader Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

that relates to not just her political platform and particular policies but also her personal character

Moral character or character (derived from charaktêr) is an analysis of an individual's steady Morality, moral qualities. The concept of ''character'' can express a variety of attributes, including the presence or lack of virtues such as empat ...

and general style of management while in office. Proponents of Thatcherism are referred to as Thatcherites. The term has been used to describe the principles of the British government under Thatcher from the 1979 general election to her resignation in 1990, but it also receives use in describing administrative efforts continuing into the Conservative governments under statesmen John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997, and as Member of Parliament ...

and David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron (born 9 October 1966) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2005 to 2016. He previously served as Leader o ...

throughout the 1990s and 2010s. In international terms, Thatcherites have been described as a part of the general socio-economic movement known as neoliberalism

Neoliberalism (also neo-liberalism) is a term used to signify the late 20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism after it fell into decline following the Second World War. A prominent fa ...

, with different countries besides the United Kingdom (such as the United States) sharing similar policies around expansionary capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

.

Thatcherism represents a systematic, decisive rejection and reversal of the post-war consensus

The post-war consensus, sometimes called the post-war compromise, was the economic order and social model of which the major political parties in post-war Britain shared a consensus supporting view, from the end of World War II in 1945 to the ...

inside Great Britain in terms of governance, whereby the major political parties largely agreed on the central themes of Keynesianism

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output and ...

, the welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equitabl ...

, nationalised industry

State ownership, also called government ownership and public ownership, is the ownership of an industry, asset, or enterprise by the state or a public body representing a community, as opposed to an individual or private party. Public ownership ...

, and close regulation of the British economy

The economy of the United Kingdom is a highly developed social market and market-orientated economy. It is the sixth-largest national economy in the world measured by nominal gross domestic product (GDP), ninth-largest by purchasing power pa ...

before Thatcher's rise to prominence. Under her administration, there was one major exception to Thatcherite changes: the National Health Service

The National Health Service (NHS) is the umbrella term for the publicly funded healthcare systems of the United Kingdom (UK). Since 1948, they have been funded out of general taxation. There are three systems which are referred to using the " ...

(NHS), which was widely popular with the British public. In 1982, Thatcher promised that the NHS was "safe in our hands".

The exact terms of what makes up Thatcherism, as well as its specific legacy in British history over the past decades, are controversial. Ideologically, Thatcherism has been described by Nigel Lawson

Nigel Lawson, Baron Lawson of Blaby, (born 11 March 1932) is a British Conservative Party politician and journalist. He was a Member of Parliament representing the constituency of Blaby from 1974 to 1992, and served in the cabinet of Margaret ...

, Thatcher's Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

from 1983 to 1989, as a political platform emphasising free market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any o ...

s with restrained government spending

Government spending or expenditure includes all government consumption, investment, and transfer payments. In national income accounting, the acquisition by governments of goods and services for current use, to directly satisfy the individual o ...

and tax cut

A tax cut represents a decrease in the amount of money taken from taxpayers to go towards government revenue. Tax cuts decrease the revenue of the government and increase the disposable income of taxpayers. Tax cuts usually refer to reductions in ...

s that gets coupled with British nationalism

British nationalism asserts that the British are a nation and promotes the cultural unity of Britons,Guntram H. Herb, David H. Kaplan. Nations and Nationalism: A Global Historical Overview: A Global Historical Overview. Santa Barbara, Californi ...

both at home and abroad. Thatcher herself rarely used the word "Thatcherism". However, she gave a speech in Solihull

Solihull (, or ) is a market town and the administrative centre of the wider Metropolitan Borough of Solihull in West Midlands County, England. The town had a population of 126,577 at the 2021 Census. Solihull is situated on the River Blythe i ...

during her campaign for the 1987 general election and included in a discussion of the economic successes there the remark: "that's what I call Thatcherism".

''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'' stated in April 2008 that the programme of the next non-Conservative government, with statesman Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

's "New Labour

New Labour was a period in the history of the British Labour Party from the mid to late 1990s until 2010 under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The name dates from a conference slogan first used by the party in 1994, later seen ...

" organisation governing the nation throughout the 1990s and 2000s, basically accepted the central reform measures of Thatcherism such as deregulation

Deregulation is the process of removing or reducing state regulations, typically in the economic sphere. It is the repeal of governmental regulation of the economy. It became common in advanced industrial economies in the 1970s and 1980s, as a ...

, privatisation

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

of key national industries, maintaining a flexible labour market, marginalising the trade unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and Employee ben ...

and centralising power from local authorities

Local government is a generic term for the lowest tiers of public administration within a particular sovereign state. This particular usage of the word government refers specifically to a level of administration that is both geographically-loca ...

to central government. While Blair distanced himself from certain aspects of Thatcherism earlier in his career, in his 2010 autobiography ''A Journey

''A Journey'' is a memoir by Tony Blair of his tenure as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Published in the UK on 1 September 2010, it covers events from when he 1994 Labour Party leadership election, became leader of the Labour Party (UK), ...

'' he argued both that "Britain needed the industrial and economic reforms of the Thatcher period" and as well that "much of what she wanted to do in the 1980s was inevitable, a consequence not of ideology but of social and economic change."

Overview

Thatcherism attempts to promote low inflation, the small state andfree market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any o ...

s through tight control of the money supply, privatisation

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

and constraints on the labour movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

. It is often compared with Reaganomics

Reaganomics (; a portmanteau of ''Reagan'' and ''economics'' attributed to Paul Harvey), or Reaganism, refers to the neoliberal economic policies promoted by U.S. President Ronald Reagan during the 1980s. These policies are commonly associat ...

in the United States, economic rationalism

Economic rationalism is an Australian term often used in the discussion of Macroeconomics, macroeconomic policy, applicable to the economic policy of many governments around the world, in particular during the 1980s and 1990s. Economic rationalist ...

in Australia and Rogernomics

In February 1985, journalists at the ''New Zealand Listener'' coined the term Rogernomics, a portmanteau of "Roger" and "economics" (by analogy with "Reaganomics"), to describe the neoliberal economic policies followed by Roger Douglas. Douglas ...

in New Zealand and as a key part of the worldwide economic liberal

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic liberalism, ...

movement.

Nigel Lawson

Nigel Lawson, Baron Lawson of Blaby, (born 11 March 1932) is a British Conservative Party politician and journalist. He was a Member of Parliament representing the constituency of Blaby from 1974 to 1992, and served in the cabinet of Margaret ...

, Thatcher's Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

from 1983 to 1989, listed the Thatcherite ideals as "free markets, financial discipline, firm control over public expenditure, tax cuts, nationalism, 'Victorian values' (of the Samuel Smiles self-help variety), privatisation and a dash of populism". Thatcherism is thus often compared to classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition

Political culture describes how culture impacts politics. Every political system is embedded in a particular political culture.

Definition

Gabriel Almond defines it as "the particular patt ...

. Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

said that "Margaret Thatcher is not in terms of belief a Tory. She is a nineteenth-century Liberal".

Thatcher herself stated during a speech in 1983: "I would not mind betting that if Mr Gladstone were alive today he would apply to join the Conservative Party". In the 1996 Keith Joseph memorial lecture, Thatcher argued: "The kind of Conservatism which he and I ..favoured would be best described as 'liberal', in the old-fashioned sense. And I mean the liberalism of Mr Gladstone, not of the latter day collectivists". Thatcher once told Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek ( , ; 8 May 189923 March 1992), often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian–British economist, legal theorist and philosopher who is best known for his defense of classical liberalism. Haye ...

: "I know you want me to become a Whig; no, I am a Tory". Hayek believed "she has felt this very clearly". The relationship between Thatcherism and liberalism is complicated. Thatcher's former Defence Secretary John Nott

Sir John William Frederic Nott (born 1 February 1932) is a former British Conservative Party politician. He was a senior politician of the late 1970s and early 1980s, playing a prominent role as Secretary of State for Defence during the 1982 in ...

claimed that "it is a complete misreading of her beliefs to depict her as a nineteenth-century Liberal".

As Ellen Meiksins Wood has argued, Thatcherite capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

was compatible with traditional British political institutions. As Prime Minister, Thatcher did not challenge ancient institutions such as the monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

or the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

, but some of the most recent additions such as the trade unions. Indeed, many leading Thatcherites, including Thatcher herself, went on to join the House of Lords, an honour which William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

, for instance, had declined. Thinkers closely associated with Thatcherism include Keith Joseph

Keith Sinjohn Joseph, Baron Joseph, (17 January 1918 – 10 December 1994), known as Sir Keith Joseph, 2nd Baronet, for most of his political life, was a British politician, intellectual and barrister. A member of the Conservative Party, he ...

, Enoch Powell

John Enoch Powell, (16 June 1912 – 8 February 1998) was a British politician, classical scholar, author, linguist, soldier, philologist, and poet. He served as a Conservative Member of Parliament (1950–1974) and was Minister of Health (1 ...

, Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. In an interview with Simon Heffer

Simon James Heffer (born 18 July 1960) is an English historian, journalist, author and political commentator. He has published several biographies and a series of books on the social history of Great Britain from the mid-nineteenth century unti ...

in 1996, Thatcher stated that the two greatest influences on her as Conservative leader had been Joseph and Powell, who were both "very great men".

Thatcher was a strong critic of communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

and socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

. Biographer John Campbell reports that in July 1978 when asked by a Labour MP in Commons what she meant by socialism "she was at a loss to reply. What in fact she meant was Government support for inefficient industries, punitive taxation, regulation of the labour market, price controlseverything that interfered with the functioning of the free economy".

Thatcherism before Thatcher

A number of commentators have traced the origins of Thatcherism in post-war British politics. The historian Ewen Green claimed there was resentment of the inflation, taxation and the constraints imposed by the labour movement, which was associated with the so-called Buttskellite consensus in the decades before Thatcher came to prominence. Although the Conservative leadership accommodated itself to theClement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

government's post-war reforms, there was continuous right-wing opposition in the lower ranks of the party, in right-wing pressure groups like the Middle Class Alliance and the People's League for the Defence of Freedom and later in think tanks like the Centre for Policy Studies

The Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) is a think tank and pressure group in the United Kingdom. Its goal is to promote coherent and practical policies based on its founding principles of: free markets, "small state," low tax, national independe ...

. For example, in the 1945 general election the Conservative Party chairman Ralph Assheton had wanted 12,000 abridged copies of ''The Road to Serfdom

''The Road to Serfdom'' ( German: ''Der Weg zur Knechtschaft'') is a book written between 1940 and 1943 by Austrian-British economist and philosopher Friedrich Hayek. Since its publication in 1944, ''The Road to Serfdom'' has been popular among ...

'' (a book by the anti-socialist economist Friedrich Hayek later closely associated with Thatcherism), taking up one-and-a-half tons of the party's paper ration, distributed as election propaganda.

The historian Christopher Cooper traced the formation of the monetarist

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. Monetarist theory asserts that variations in the money supply have major influences on national ...

economics at the heart of Thatcherism back to the resignation of Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer Peter Thorneycroft

George Edward Peter Thorneycroft, Baron Thorneycroft, (26 July 1909 – 4 June 1994) was a British Conservative Party politician. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1957 and 1958.

Early life

Born in Dunston, Staffordshire, Thorn ...

in 1958.

As early as 1950, Thatcher accepted the consensus of the day about the welfare state, claiming the credit belonged to the Conservatives in a speech to the Conservative Association annual general meeting. Biographer Charles Moore states:

Historian Richard Vinen

Richard Charles Vinen is a British historian and academic who holds a professorship at King's College London. Vinen is a specialist in 20th-century European history, particularly of Britain and France.libertarian

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's e ...

movement, rejecting traditional Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

ism. Thatcherism is associated with libertarianism within the Conservative Party, albeit one of libertarian ends achieved by using strong and sometimes authoritarian leadership. British political commentator Andrew Marr

Andrew William Stevenson Marr (born 31 July 1959) is a British journalist and broadcaster. Beginning his career as a political commentator, he subsequently edited ''The Independent'' newspaper from 1996 to 1998 and was political editor of BBC N ...

has called libertarianism the "dominant, if unofficial, characteristic of Thatcherism". Whereas some of her heirs, notably Michael Portillo

Michael Denzil Xavier Portillo (; born 26 May 1953) is a British journalist, broadcaster and former politician. His broadcast series include railway documentaries such as ''Great British Railway Journeys'' and '' Great Continental Railway Journ ...

and Alan Duncan

Sir Alan James Carter Duncan (born 31 March 1957) is a British former Conservative Party politician who served as Minister of State for International Development from 2010 to 2014 and as Minister of State for Europe and the Americas from 201 ...

, embraced this libertarianism, others in the Thatcherite movement such as John Redwood

Sir John Alan Redwood (born 15 June 1951) is a British politician who has been the Member of Parliament (MP) for Wokingham in Berkshire since 1987. A member of the Conservative Party, he was Secretary of State for Wales in the Major government ...

sought to become more populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

.

Some commentators have argued that Thatcherism should not be considered properly libertarian. Noting the tendency towards strong central government in matters concerning the trade unions and local authorities, Andrew Gamble

Andrew Michael Gamble (born 15 August 1947) is a British scholar of politics. He was Professor of Politics at the University of Cambridge and Fellow of Queens' College from 2007 to 2014. He was a member of the Department of Politics at the Univ ...

summarised Thatcherism as "the free economy and the strong state". Simon Jenkins

Sir Simon David Jenkins (born 10 June 1943) is a British author, a newspaper columnist and editor. He was editor of the ''Evening Standard'' from 1976 to 1978 and of ''The Times'' from 1990 to 1992.

Jenkins chaired the National Trust from 20 ...

accused the Thatcher government of carrying out a nationalisation of Britain. Libertarian political theorist Murray Rothbard

Murray Newton Rothbard (; March 2, 1926 – January 7, 1995) was an American economist of the Austrian School, economic historian, political theorist, and activist. Rothbard was a central figure in the 20th-century American libertarian m ...

did not consider Thatcherism to be libertarian and heavily criticised Thatcher and Thatcherism stating that "Thatcherism is all too similar to Reaganism

Ronald Reagan was the 40th President of the United States (1981–1989). A Republican and former actor and governor of California, he energized the conservative movement in the United States from 1964. His basic foreign policy was to equal and ...

: free-market rhetoric masking statist

In political science, statism is the doctrine that the political authority of the state is legitimate to some degree. This may include economic and social policy, especially in regard to taxation and the means of production.

While in use since ...

content". Stuart McAnulla states that Thatcherism is actually liberal conservatism

Liberal conservatism is a political ideology combining conservative policies with liberal stances, especially on economic issues but also on social and ethical matters, representing a brand of political conservatism strongly influenced by libe ...

, a combination of liberal economics and a strong state.

Thatcherism as a form of government

Another important aspect of Thatcherism is the style of governance. Britain in the 1970s was often referred to as "ungovernable". Thatcher attempted to redress this by centralising a great deal of power to herself, as the Prime Minister, often bypassing traditional cabinet structures (such as cabinet committees). This personal approach also became identified with personal toughness at times such as theFalklands War

The Falklands War ( es, link=no, Guerra de las Malvinas) was a ten-week undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1982 over two British dependent territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and its territorial de ...

in 1982, the IRA bomb at the Conservative conference in 1984 and the miners' strike

Miners' strikes are when miners conduct strike actions.

See also

* List of strikes

References

{{Reflist

Miners

A miner is a person who extracts ore, coal, chalk, clay, or other minerals from the earth through mining. There are tw ...

in 1984–85.

Sir Charles Powell, the Foreign Affairs Private Secretary to the Prime Minister (1984–1991 and 1996) described her style as such: "I've always thought there was something Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishme ...

about Mrs Thatcher which came through in the style of government: the absolute determination, the belief that there's a vanguard which is right and if you keep that small, tightly knit team together, they will drive things through ... there's no doubt that in the 1980s, No. 10 could beat the bushes of Whitehall pretty violently. They could go out and really confront people, lay down the law, bully a bit".

Criticism

By 1987, after Thatcher's successful third re-election, criticism of Thatcherism increased. At the time, Thatcher claimed it was necessary tackle the "culture of dependency" by government intervention to stop socialised welfare. In 1988, she caused controversy when she made the remarks, "You do not blame society. Society is not anyone. You are personally responsible." and, "Don't blame society — that's no one." These comments attracted significant criticism including from other conservatives due to their belief in individual and collective responsibility. In 1988, Thatcher told the party conference that her third term was to be about 'social affairs'. During her last three years in power, she attempted to reform socialised welfare, differing from her earlier stated goal of "rolling back the state".Economic positions

Thatcherite economics

Thatcherism is associated with the economic theory ofmonetarism

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. Monetarist theory asserts that variations in the money supply have major influences on measures ...

, notably put forward by Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek ( , ; 8 May 189923 March 1992), often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian–British economist, legal theorist and philosopher who is best known for his defense of classical liberalism. Haye ...

's ''The Constitution of Liberty

''The Constitution of Liberty'' is the magnum opus of Austrian economist and 1974 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences recipient Friedrich A. Hayek. First published in 1960 by the University of Chicago Press, the book is considered Hayek’s ...

'' which Thatcher had banged on a table while saying "this is what we believe". In contrast to previous government policy, monetarism placed a priority on controlling inflation over controlling unemployment. According to monetarist theory, inflation is the result of there being too much money in the economy. It was claimed that the government should seek to control the money supply

In macroeconomics, the money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of currency held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include Circulation (curren ...

to control inflation. By 1979, it was not only the Thatcherites who were arguing for stricter control of inflation. The Labour Chancellor Denis Healey

Denis Winston Healey, Baron Healey, (30 August 1917 – 3 October 2015) was a British Labour Party (UK), Labour politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1974 to 1979 and as Secretary of State for Defence from 1964 to 1970; he ...

had already adopted some monetarist policies, such as reducing public spending and selling off the government's shares in BP.

Moreover, it has been argued that the Thatcherites were not strictly monetarist in practice. A common theme centres on the Medium Term Financial Strategy, issued in the 1980 budget, which consisted of targets for reducing the growth of the money supply in the following years. After overshooting many of these targets, the Thatcher government revised the targets upwards in 1982. Analysts have interpreted this as an admission of defeat in the battle to control the money supply. The economist C. F. Pratten claimed that "since 1984, behind a veil of rhetoric, the government has lost any faith it had in technical monetarism. The money supply, as measured by M3, has been allowed to grow erratically, while calculation of the public sector borrowing requirement is held down by the ruse of subtracting the proceeds of privatisation as well as taxes from government expenditure. The principles of monetarism have been abandoned".

Thatcherism is also associated with supply-side economics

Supply-side economics is a macroeconomic theory that postulates economic growth can be most effectively fostered by lowering taxes, decreasing regulation, and allowing free trade. According to supply-side economics, consumers will benefit fr ...

. Whereas Keynesian economics

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output an ...

holds that the government should stimulate economic growth by increasing demand through increased credit and public spending, supply-side economists argue that the government should instead intervene only to create a free market by lowering taxes, privatising state industries and increasing restraints on trade unionism.

Trade union legislation

Reduction in the power of the trades unions was made gradually, unlike the approach of theEdward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George Heath (9 July 191617 July 2005), often known as Ted Heath, was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1970 to 1974 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conserv ...

government and the greatest single confrontation with the unions was the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) strike of 1984–1985, in which the miners' union was eventually defeated. There is evidence that this confrontation with the trade unions was anticipated by both the Conservative Party and the NUM. The outcome contributed to the resurgence of the power of capital over labour.

Domestic and social positions

Thatcherite morality

Thatcherism is associated with a conservative stance onmorality

Morality () is the differentiation of intentions, decisions and actions between those that are distinguished as proper (right) and those that are improper (wrong). Morality can be a body of standards or principles derived from a code of cond ...

. argues that Thatcherism married conservatism with free-market economics

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ot ...

. Thatcherism did not propose dramatic new panacea

In Greek mythology, Panacea (Greek ''Πανάκεια'', Panakeia), a goddess of universal remedy, was the daughter of Asclepius and Epione. Panacea and her four sisters each performed a facet of Apollo's art:

* Panacea (the goddess of universal ...

s such as Milton Friedman's negative income tax

In economics, a negative income tax (NIT) is a system which reverses the direction in which tax is paid for incomes below a certain level; in other words, earners above that level pay money to the state while earners below it receive money, as ...

. Instead the goal was to create a rational tax-benefit economic system that would increase British efficiency

Efficiency is the often measurable ability to avoid wasting materials, energy, efforts, money, and time in doing something or in producing a desired result. In a more general sense, it is the ability to do things well, successfully, and without ...

while supporting a conservative social system based on traditional morality. There would still be a minimal safety net

A safety net is a net to protect people from injury after falling from heights by limiting the distance they fall, and deflecting to dissipate the impact energy. The term also refers to devices for arresting falling or flying objects for the ...

for the poor, but major emphasis was on encouraging individual effort and thrift. Thatcherism sought to minimise the importance of welfare for the middle classes, and reinvigorate Victorian bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

virtues. Thatcherism was family centred, unlike the extreme individualism of most neoliberal models. It had its roots in that historical experiences such as Methodism

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's br ...

, as well as the fear of the too-powerful state that had troubled Hayek.

Norman Tebbit

Norman Beresford Tebbit, Baron Tebbit (born 29 March 1931) is a British politician. A member of the Conservative Party, he served in the Cabinet from 1981 to 1987 as Secretary of State for Employment (1981–1983), Secretary of State for Trad ...

, a close ally of Thatcher, laid out in a 1985 lecture what he thought to be the permissive society

A permissive society, also referred to as permissive culture, is a society in which some social norms become increasingly liberal, especially with regard to sexual freedom. This usually accompanies a change in what is considered deviant. While t ...

that conservatives should oppose:

Despite her association with social conservatism

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and variety of conservatism which places emphasis on traditional power structures over social pluralism. Social conservatives organize in favor of duty, traditional values and social institutio ...

, Thatcher voted in 1966 to legalise homosexuality, one of the few Conservative MPs to do so. That same year, she also voted in support of legal abortion. However, in the 1980s during her time as Prime Minister, the Thatcher government enacted Section 28

Section 28 or Clause 28While going through Parliament, the amendment was constantly relabelled with a variety of clause numbers as other amendments were added to or deleted from the Bill, but by the final version of the Bill, which received R ...

, a law that opposed the "intentional promotion" of homosexuality by local authorities and "promotion" of the teaching of "the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship" in schools. In her 1987 speech to the Conservative Party conference, Thatcher stated:

The law was opposed by many gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, , 3 ...

advocates such as Stonewall

Stonewall or Stone wall may refer to:

* Stone wall, a kind of masonry construction

* Stonewalling, engaging in uncooperative or delaying tactics

* Stonewall riots, a 1969 turning point for the modern LGBTQ rights movement in Greenwich Village, Ne ...

and OutRage!

OutRage! was a British political group focused on lesbian and gay rights. Founded in 1990, the organisation ran for 21 years until 2011. It described itself as "a broad based group of queers committed to radical, non-violent direct action and ...

and was later repealed by Tony Blair's Labour government in 2000 (in Scotland) and 2003. Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron later issued an official apology for previous Conservative policies on homosexuality, specifically the introduction of the controversial Section 28 laws from the 1980s, viewing past ideological views as "a mistake" with his own ideological direction.

Sermon on the Mound

In May 1988, Thatcher gave an address to theGeneral Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presby ...

of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

. In the address, Thatcher offered a theological justification for her ideas on capitalism and the market economy. She said "Christianity is about spiritual redemption, not social reform" and she quoted St. Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

by saying "If a man will not work he shall not eat". Choice played a significant part in Thatcherite reforms and Thatcher said that choice was also Christian, stating that Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

chose to lay down his life and that all individuals have the God-given right to choose between good and evil

In religion, ethics, philosophy, and psychology "good and evil" is a very common dichotomy. In cultures with Manichaean and Abrahamic religious influence, evil is perceived as the dualistic antagonistic opposite of good, in which good shoul ...

.

Foreign policy

Atlanticism

Whilst Thatcher was Prime Minister, she greatly embraced

Whilst Thatcher was Prime Minister, she greatly embraced transatlantic relations

Transatlantic relations refer to the historic, cultural, political, economic and social relations between countries on both side of the Atlantic Ocean. Sometimes it specifically means relationships between the Anglophone North American countr ...

with the U.S. President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

. She often publicly supported Reagan's policies even when other Western allies were not as vocal. For example, she granted permission for American planes to use British bases for raids, such as the 1986 United States bombing of Libyan Arab Jamahiriya

Muammar Gaddafi became the ''de facto'' leader of Libya on 1 September 1969 after leading a group of young Libyan Army officers against King Idris I in a bloodless coup d'état. After the king had fled the country, the Revolutionary Comman ...

, and allowed American cruise missiles and Pershing missiles to be housed on British soil in response to Soviet deployment of SS-20 nuclear missiles targeting Britain and other Western European nations.

Europe

WhileEuroscepticism

Euroscepticism, also spelled as Euroskepticism or EU-scepticism, is a political position involving criticism of the European Union (EU) and European integration. It ranges from those who oppose some EU institutions and policies, and seek reform ...

has for many become a characteristic of Thatcherism, Thatcher was far from consistent on the issue, only becoming truly Eurosceptic in the last years of her time as Prime Minister. Thatcher supported Britain's entry into the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisb ...

in 1973, campaigned for a "Yes" vote in the 1975 referendum and signed the Single European Act

The Single European Act (SEA) was the first major revision of the 1957 Treaty of Rome. The Act set the European Community an objective of establishing a single market by 31 December 1992, and a forerunner of the European Union's Common Foreign ...

in 1986.

Towards the end of the 1980s, Thatcher (and so Thatcherism) became increasingly vocal in its opposition to allowing the European Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

to supersede British sovereignty. In a famous 1988 Bruges speech, Thatcher declared: "We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them reimposed at a European level, with a European superstate exercising a new dominance from Brussels".

Dispute over the term

It is often claimed that the word ''Thatcherism'' was coined by cultural theorist Stuart Hall in a 1979 ''Marxism Today

''Marxism Today'', published between 1957 and 1991, was the theoretical magazine of the Communist Party of Great Britain. The magazine was headquartered in London. It was particularly important during the 1980s under the editorship of Martin Jacque ...

'' article. However, this is not true as the term was first used by Tony Heath in an article he wrote that appeared in ''Tribune

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs acted as a check on the ...

'' on 10 August 1973. Writing as ''Tribune''s education correspondent, Heath wrote: "It will be argued that teachers are members of a profession which must not be influenced by political considerations. With the blight of Thatcherism spreading across the land that is a luxury that only the complacent can afford". Although the term had in fact been widely used before then, not all social critics have accepted the term as valid, with the High Tory

In the United Kingdom and elsewhere, High Toryism is the old traditionalist conservatism which is in line with the Toryism originating in the 17th century. High Tories and their worldview are sometimes at odds with the modernising elements of the ...

journalist T. E. Utley

Thomas Edwin Utley (1 February 1921 – 21 June 1988), known as Peter Utley, was a British High Tory journalist and writer.

Early life

He was adopted by Miss Ann Utley and christened Thomas Edwin, although he was always known as Peter."T. E. ...

believing "There is no such thing as Thatcherism".

Utley contended that the term was a creation of Thatcher's enemies who wished to damage her by claiming that she had an inflexible devotion to a certain set of principles and also by some of her friends who had little sympathy for what he called "the English political tradition" because it facilitated "compromise and consensus". Utley argued that a free and competitive economy, rather than being an innovation of Thatcherism, was one "more or less permanent ingredient in modern Conservative philosophy":

It was on that principle that Churchill fought the 1945 election, having just read Hayek's ''Road to Serfdom''. ..What brought the Tories to 13 years of political supremacy inIn foreign policy, Utley claimed Thatcher's desire to restore British greatness did not mean "primarily a power devoted to the preservation of its own interests", but that she belonged "to that militant Whig branch of English Conservatism...her view of foreign policy has a high moral content". In practical terms, he claimed this expressed itself in her preoccupation in "the freedom of Afghanistan rather than the security of Ulster". Such leftist critics as1951 Events January * January 4 – Korean War: Third Battle of Seoul – Chinese and North Korean forces capture Seoul for the second time (having lost the Second Battle of Seoul in September 1950). * January 9 – The Government of the United ...was the slogan 'Set the people free'. ..There is absolutely nothing new about the doctrinal front that she presents on these matters. ..As for 'privatisation', Mr. Powell proposed it in ..1968. As for 'property-owning democracy', I believe it wasAnthony Eden Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957. Achieving rapid promo ...who coined the phrase.

Anthony Giddens

Anthony Giddens, Baron Giddens (born 18 January 1938) is an English sociologist who is known for his theory of structuration and his holistic view of modern societies. He is considered to be one of the most prominent modern sociologists and is t ...

claim that Thatcherism was purely an ideology and argue that her policies marked a change which was dictated more by political interests than economic reasons:

The Conservative historian of Peterhouse

Peterhouse is the oldest constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England, founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely. Today, Peterhouse has 254 undergraduates, 116 full-time graduate students and 54 fellows. It is quite o ...

, Maurice Cowling

Maurice John Cowling (6 September 1926 – 24 August 2005) was a British historian and a Fellow of Peterhouse, Cambridge.

Early life

Cowling was born in West Norwood, South London, son of Reginald Frederick Cowling (1901–1962), a patent agent ...

, also questioned the uniqueness of "Thatcherism". Cowling claimed that Thatcher used "radical variations on that patriotic conjunction of freedom, authority, inequality, individualism and average decency and respectability, which had been the Conservative Party's theme since at least 1886". Cowling further contended that the "Conservative Party under Mrs Thatcher has used a radical rhetoric to give intellectual respectability to what the Conservative Party has always wanted".

Historians Emily Robinson, Camilla Schofield, Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite and Natalie Thomlinson have argued that by the 1970s Britons were keen about defining and claiming their individual rights, identities and perspectives. They demanded greater personal autonomy and self-determination and less outside control. They angrily complained that the establishment was withholding it. They argue this shift in concerns helped cause Thatcherism and was incorporated into Thatcherism's appeal.

Criticism

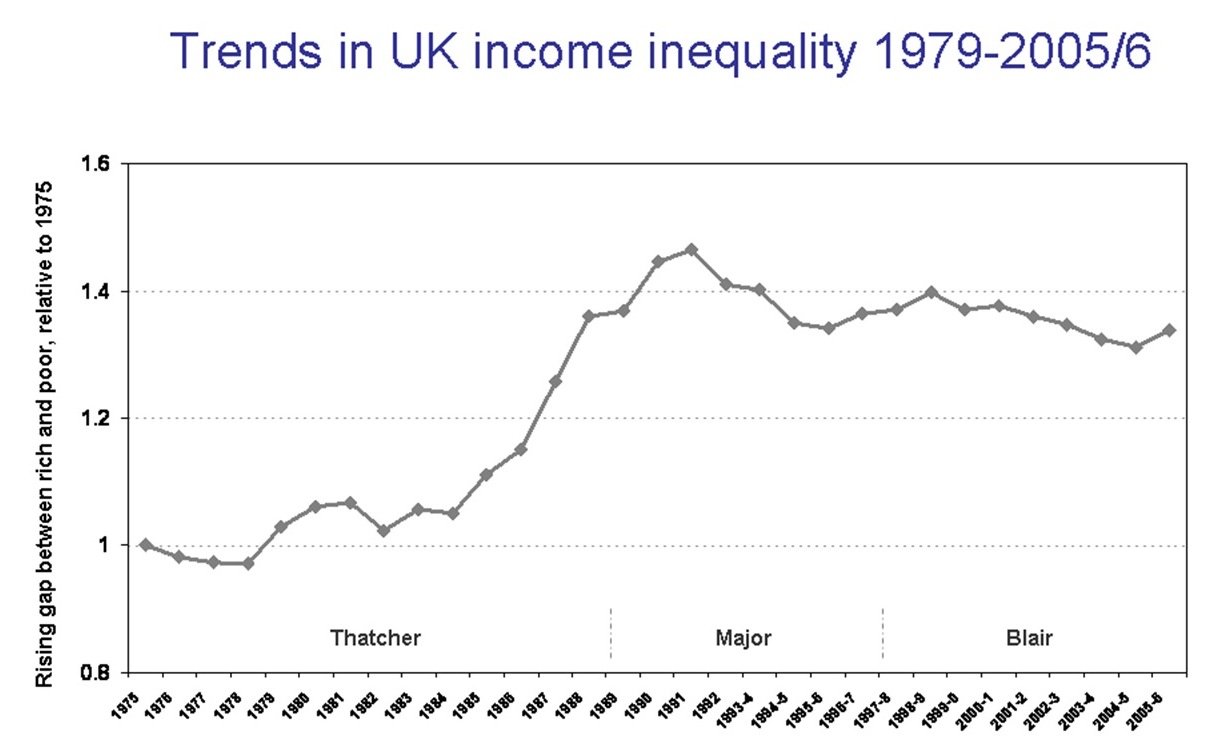

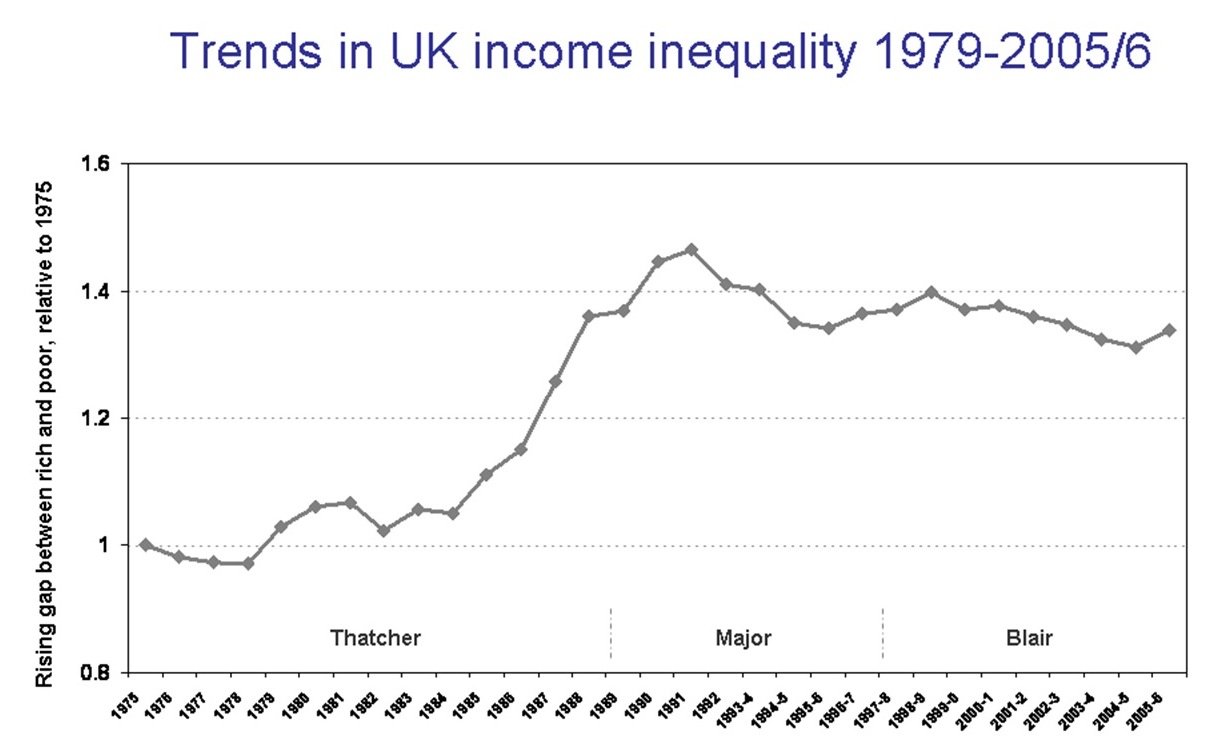

Critics of Thatcherism claim that its successes were obtained only at the expense of great

Critics of Thatcherism claim that its successes were obtained only at the expense of great social cost

Social cost in neoclassical economics is the sum of the private costs resulting from a transaction and the costs imposed on the consumers as a consequence of being exposed to the transaction for which they are not compensated or charged. In other w ...

s to the British population. There were nearly 3.3 million unemployed in Britain in 1984, compared to 1.5 million when she first came to power in 1979, though that figure had reverted to some 1.6 million by the end of 1990.

While credited with reviving Britain's economy, Thatcher also was blamed for spurring a doubling in the relative poverty rate. Britain's childhood-poverty rate in 1997 was the highest in Europe. When she resigned in 1990, 28% of the children in Great Britain were considered to be below the poverty line

The poverty threshold, poverty limit, poverty line or breadline is the minimum level of income deemed adequate in a particular country. The poverty line is usually calculated by estimating the total cost of one year's worth of necessities for t ...

, a number that kept rising to reach a peak of nearly 30% during the government of Thatcher's successor, John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997, and as Member of Parliament ...

. During her government, Britain's Gini coefficient reflected this growing difference, going from 0.25 in 1979 to 0.34 in 1990, at about which value it remained for the next 20 years, under both Conservative and Labour governments.

Thatcher's legacy

The extent to which one can say Thatcherism has a continuing influence on British political and economic life is unclear. In reference to modern British political culture, it could be said that a "post-Thatcherite consensus" exists, especially in regard to economic policy. In the 1980s, the now defunct

The extent to which one can say Thatcherism has a continuing influence on British political and economic life is unclear. In reference to modern British political culture, it could be said that a "post-Thatcherite consensus" exists, especially in regard to economic policy. In the 1980s, the now defunct Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

For ...

adhered to a "tough and tender" approach in which Thatcherite reforms were coupled with extra welfare provision. Neil Kinnock

Neil Gordon Kinnock, Baron Kinnock (born 28 March 1942) is a British former politician. As a member of the Labour Party, he served as a Member of Parliament from 1970 until 1995, first for Bedwellty and then for Islwyn. He was the Leader of ...

, leader of the Labour Party from 1983 to 1992, initiated Labour's rightward shift across the political spectrum

A political spectrum is a system to characterize and classify different political positions in relation to one another. These positions sit upon one or more geometric axes that represent independent political dimensions. The expressions politi ...

by largely concurring with the economic policies of the Thatcher governments. The New Labour

New Labour was a period in the history of the British Labour Party from the mid to late 1990s until 2010 under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The name dates from a conference slogan first used by the party in 1994, later seen ...

governments of Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

and Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chance ...

were described as "neo-Thatcherite" by some on the left, since many of their economic policies mimicked those of Thatcher.

In 1999, twenty years after Thatcher had come to power, the Conservative Party held a dinner in London Hilton to honour the anniversary. During the dinner several speeches were given. To Thatcher's astonishment, the Conservatives had decided that it was time to shelve the economic policies of the 1980s. The Conservative Party leader at the time William Hague

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

said that the party had learnt its lesson from the 1980s and called it a "great mistake to think that all Conservatives have to offer is solutions based on free markets". His deputy at the time Peter Lilley

Peter Bruce Lilley, Baron Lilley, PC (born 23 August 1943) is a British politician and life peer who served as a cabinet minister in the governments of Margaret Thatcher and John Major. A member of the Conservative Party, he was Member of Parl ...

elaborated and said, "belief in the free market has only ever been part of Conservatism".

In 2002, Peter Mandelson

Peter Benjamin Mandelson, Baron Mandelson (born 21 October 1953) is a British Labour Party politician who served as First Secretary of State from 2009 to 2010. He was President of the Board of Trade in 1998 and from 2008 to 2010. He is the ...

, who had served in Blair's Cabinet, famously declared that "we are all Thatcherites now".

Most of the major British political parties today accept the trade union legislation, privatisations and general free market approach to government that Thatcher's governments

Margaret Thatcher's term as the prime minister of the United Kingdom began on 4 May 1979 when she accepted an invitation of Queen Elizabeth II to form a government, and ended on 28 November 1990 upon her resignation. She was elected to the pos ...

installed. Before 2010, no major political party in the United Kingdom had committed to reversing the Thatcher government's reforms of the economy, although in the aftermath of the Great Recession

The Great Recession was a period of marked general decline, i.e. a recession, observed in national economies globally that occurred from late 2007 into 2009. The scale and timing of the recession varied from country to country (see map). At ...

from 2007 to 2012, the then Labour Party leader Ed Miliband

Edward Samuel "Ed" Miliband (born 24 December 1969) is a British politician serving as Shadow Secretary of State for Climate Change and Net Zero since 2021. He has been the Member of Parliament (MP) for Doncaster North since 2005. Miliband ...

had indicated he would support stricter financial regulation

Financial regulation is a form of regulation or supervision, which subjects financial institutions to certain requirements, restrictions and guidelines, aiming to maintain the stability and integrity of the financial system. This may be handled ...

and industry-focused policy in a move to a more mixed economy. Although Miliband was said by the ''Financial Times

The ''Financial Times'' (''FT'') is a British daily newspaper printed in broadsheet and published digitally that focuses on business and economic current affairs. Based in London, England, the paper is owned by a Japanese holding company, Nik ...

'' to have "turned his back on many of New Labour's tenets, seeking to prove that an openly socialist party could win the backing of the British electorate for the first time since the 1970s", in 2011 Miliband had declared his support for Thatcher's reductions in income tax on top earners, her legislation to change the rules on the closed shop and strikes before ballots, as well as her introduction of Right to Buy

The Right to Buy scheme is a policy in the United Kingdom, with the exception of Scotland since 1 August 2016 and Wales from 26 January 2019, which gives secure tenants of councils and some housing associations the legal right to buy, at a large ...

, saying Labour had been wrong to oppose these reforms at the time.

Moreover, the UK's comparative macroeconomic

Macroeconomics (from the Greek prefix ''makro-'' meaning "large" + ''economics'') is a branch of economics dealing with performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole.

For example, using interest rates, taxes, and ...

performance has improved since the implementation of Thatcherite economic policies. Since Thatcher resigned as British Prime Minister in 1990, British economic growth was on average higher than the other large European economies (i.e. Germany, France and Italy). Such comparisons have been controversial for decades.

Tony Blair wrote in his 2010 autobiography ''A Journey

''A Journey'' is a memoir by Tony Blair of his tenure as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Published in the UK on 1 September 2010, it covers events from when he 1994 Labour Party leadership election, became leader of the Labour Party (UK), ...

'' that "Britain needed the industrial and economic reforms of the Thatcher period". He described Thatcher's efforts as "ideological, sometimes unnecessarily so" while also stating that "much of what she wanted to do in the 1980s was inevitable, a consequence not of ideology but of social and economic change." Blair additionally labeled these viewpoints as a matter of "basic fact".

On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of Thatcher's 1979 election victory, the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

conducted a survey of opinions which opened with the following comments:

From the viewpoint of late 2019, the state of British politics showed that Thatcherism had suffered a "sad fate," according to ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Econo ...

'' Bagehot column. As a political-economic philosophy Thatcherism was originally built upon four components: commitment to free enterprise

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ...

; British nationalism

British nationalism asserts that the British are a nation and promotes the cultural unity of Britons,Guntram H. Herb, David H. Kaplan. Nations and Nationalism: A Global Historical Overview: A Global Historical Overview. Santa Barbara, Californi ...

; a plan to strengthen the state by improving efficiency; and a belief in traditional Victorian values

Victorian morality is a distillation of the moral views of the middle class in 19th-century Britain, the Victorian era.

Victorian values emerged in all classes and reached all facets of Victorian living. The values of the period—which can be ...

especially hard work and civic responsibility. The tone of Thatcherism was establishment bashing, with intellectuals a prime target, and that tone remains sharp today. Bagehot argues that some Thatcherisms have become mainstream, such as a more efficient operation of the government. Others have been sharply reduced, such as insisting that deregulation

Deregulation is the process of removing or reducing state regulations, typically in the economic sphere. It is the repeal of governmental regulation of the economy. It became common in advanced industrial economies in the 1970s and 1980s, as a ...

is always the answer to everything. The dream of restoring traditional values by creating a property-owning democracy has failed in Britain – ownership in the stock market has plunged, as has the proportion of young people who are homebuyers. Her program of privatisation became suspect when it appeared to favour investors rather than customers.

Recent developments in Britain reveal a deep conflict between Thatcherite free enterprise and Thatcherite nationalism. She wanted to reverse Britain's decline by fostering entrepreneurship – but immigrants have often played an important role as entrepreneurial leaders in Britain. Bagehot says Britain is "more successful at hosting world-class players than producing them." In the course of the Brexit

Brexit (; a portmanteau of "British exit") was the withdrawal of the United Kingdom (UK) from the European Union (EU) at 23:00 GMT on 31 January 2020 (00:00 1 February 2020 CET).The UK also left the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or ...

process, nationalists have denounced European controls over Britain's future, while business leaders often instead prioritise maintenance of their leadership of the European market. Thatcher herself showed a marked degree of Euroscepticism, as when she warned against a "European superstate

The United States of Europe (USE), the European State, the European Federation and Federal Europe, is the hypothetical scenario of the European integration leading to formation of a sovereign superstate (similar to the United States of Amer ...

."

Evaluating whether or not political conservatives of the 2020s continue the neoliberal legacy of prior years, stateswoman Theresa May

Theresa Mary May, Lady May (; née Brasier; born 1 October 1956) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2016 to 2019. She previously served in David Cameron's cab ...

's Conservative Party election manifesto has attracted attention due to its inclusion of the lines: "We do not believe in untrammelled free markets. We reject the cult of selfish individualism. We abhor social division, injustice, unfairness and inequality." Journalists such as Ross Gittins of ''The Sydney Morning Herald

''The Sydney Morning Herald'' (''SMH'') is a daily compact newspaper published in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, and owned by Nine. Founded in 1831 as the ''Sydney Herald'', the ''Herald'' is the oldest continuously published newspaper ...

'' have cited this as a move away from the standard arguments made historically by Thatcherites and related advocates.

See also

*Blairism

In British politics, Blairism is the political ideology of Tony Blair, the former leader of the Labour Party and Prime Minister between 1997 and 2007, and those that support him, known as Blairites. It entered the '' New Penguin English Dictio ...

* Brownism

In British politics, Brownism is the political ideology of the former Prime Minister and leader of the Labour Party Gordon Brown and those that follow him. Proponents of Brownism are referred to as Brownites.

Ideology

In an opiniated articl ...

* Gladstonian liberalism

* Liberal conservatism

Liberal conservatism is a political ideology combining conservative policies with liberal stances, especially on economic issues but also on social and ethical matters, representing a brand of political conservatism strongly influenced by libe ...

* Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism (also neo-liberalism) is a term used to signify the late 20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism after it fell into decline following the Second World War. A prominent fa ...

* New Public Management

New Public Management (NPM) is an approach to running public service organizations that is used in government and public service institutions and agencies, at both sub-national and national levels. The term was first introduced by academics in the ...

* Orbanomics

Orbanomics is the name given to the economic policies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and his government since it took power in 2010. These policies are in reaction to the global economic crisis and the state of Hungary's economy in it. I ...

* Pinochetism

Pinochetism ( es, Pinochetismo) is a Right-wing politics, right-wing to Far-right politics, far-right personalism, personalist political ideology based on the principles of anti-communism, conservatism, authoritarianism, militarism, patriotism, na ...

* Political positions of David Cameron

This article concerns the policies, views and voting record of David Cameron, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (May 2010 to July 2016). Cameron describes himself as a "modern compassionate conservative" and has said that he is "fe ...

* Powellism

Powellism is the name given to the political views of Conservative and Ulster Unionist politician Enoch Powell. They derive from his High Tory and libertarian outlook.

According to the ''Oxford English Dictionary'', the word ''Powellism'' was ...

* Reaganomics

Reaganomics (; a portmanteau of ''Reagan'' and ''economics'' attributed to Paul Harvey), or Reaganism, refers to the neoliberal economic policies promoted by U.S. President Ronald Reagan during the 1980s. These policies are commonly associat ...

* Right-wing populism

Right-wing populism, also called national populism and right-wing nationalism, is a political ideology that combines right-wing politics and populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric employs anti-elitist sentiments, opposition to the Establi ...

References

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * *External links

*What is Thatcherism? (BBC News Online)

What is Thatcherism? (Britpolitics.co.uk)

{{Use dmy dates, date=February 2021 1970s economic history 1980s economic history 1990s economic history 1970s neologisms British nationalism Conservative Party (UK) factions Eponymous political ideologies Euroscepticism in the United Kingdom Margaret Thatcher Neoliberalism History of the Conservative Party (UK) History of libertarianism Liberal conservatism Libertarian theory Libertarianism in the United Kingdom Politics of the United Kingdom Right-libertarianism Right-wing ideologies Right-wing politics in the United Kingdom Right-wing populism in the United Kingdom