Telegram on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus

Passing messages by signalling over distance is an ancient practice. One of the oldest examples is the signal towers of the

Passing messages by signalling over distance is an ancient practice. One of the oldest examples is the signal towers of the

An

An

The early ideas for an electric telegraph included in 1753 using

The early ideas for an electric telegraph included in 1753 using  Most of the early electrical systems required multiple wires (Ronalds' system was an exception), but the system developed in the United States by

Most of the early electrical systems required multiple wires (Ronalds' system was an exception), but the system developed in the United States by

Railway signal telegraphy was developed in Britain from the 1840s onward. It was used to manage railway traffic and to prevent accidents as part of the railway signalling system. On 12 June 1837 Cooke and Wheatstone were awarded a patent for an electric telegraph. This was demonstrated between

Railway signal telegraphy was developed in Britain from the 1840s onward. It was used to manage railway traffic and to prevent accidents as part of the railway signalling system. On 12 June 1837 Cooke and Wheatstone were awarded a patent for an electric telegraph. This was demonstrated between

A

A

A teleprinter is a telegraph machine that can send messages from a typewriter-like keyboard and print incoming messages in readable text with no need for the operators to be trained in the telegraph code used on the line. It developed from various earlier printing telegraphs and resulted in improved transmission speeds. The

A teleprinter is a telegraph machine that can send messages from a typewriter-like keyboard and print incoming messages in readable text with no need for the operators to be trained in the telegraph code used on the line. It developed from various earlier printing telegraphs and resulted in improved transmission speeds. The

In a punched-tape system, the message is first typed onto punched tape using the code of the telegraph systemŌĆöMorse code for instance. It is then, either immediately or at some later time, run through a transmission machine which sends the message to the telegraph network. Multiple messages can be sequentially recorded on the same run of tape. The advantage of doing this is that messages can be sent at a steady, fast rate making maximum use of the available telegraph lines. The economic advantage of doing this is greatest on long, busy routes where the cost of the extra step of preparing the tape is outweighed by the cost of providing more telegraph lines. The first machine to use punched tape was Bain's teleprinter (Bain, 1843), but the system saw only limited use. Later versions of Bain's system achieved speeds up to 1000 words per minute, far faster than a human operator could achieve.

The first widely used system (Wheatstone, 1858) was first put into service with the British

In a punched-tape system, the message is first typed onto punched tape using the code of the telegraph systemŌĆöMorse code for instance. It is then, either immediately or at some later time, run through a transmission machine which sends the message to the telegraph network. Multiple messages can be sequentially recorded on the same run of tape. The advantage of doing this is that messages can be sent at a steady, fast rate making maximum use of the available telegraph lines. The economic advantage of doing this is greatest on long, busy routes where the cost of the extra step of preparing the tape is outweighed by the cost of providing more telegraph lines. The first machine to use punched tape was Bain's teleprinter (Bain, 1843), but the system saw only limited use. Later versions of Bain's system achieved speeds up to 1000 words per minute, far faster than a human operator could achieve.

The first widely used system (Wheatstone, 1858) was first put into service with the British

A worldwide communication network meant that telegraph cables would have to be laid across oceans. On land cables could be run uninsulated suspended from poles. Underwater, a good insulator that was both flexible and capable of resisting the ingress of seawater was required. A solution presented itself with

A worldwide communication network meant that telegraph cables would have to be laid across oceans. On land cables could be run uninsulated suspended from poles. Underwater, a good insulator that was both flexible and capable of resisting the ingress of seawater was required. A solution presented itself with

The Effect of the Telegraph on Law and Order, War, Diplomacy, and Power Politics

'' in ''Interdisciplinary Science Reviews'', 2000. Accessed 1 August 2014. It was relaid the next year and connections to Ireland and the

In 1843, Scottish inventor Alexander Bain invented a device that could be considered the first

In 1843, Scottish inventor Alexander Bain invented a device that could be considered the first

The late 1880s through to the 1890s saw the discovery and then development of a newly understood phenomenon into a form of

The late 1880s through to the 1890s saw the discovery and then development of a newly understood phenomenon into a form of

A telegram service is a company or public entity that delivers telegraphed messages directly to the recipient. Telegram services were not inaugurated until

A telegram service is a company or public entity that delivers telegraphed messages directly to the recipient. Telegram services were not inaugurated until

"Digital technology and institutional change from the gilded age to modern times: The impact of the telegraph and the internet"

, ''Journal of Economic Issues'', vol. 34, iss. 2, pp. 267ŌĆō289, June 2000.

online

. * Hochfelder, David, ''The Telegraph in America, 1832ŌĆō1920'' (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012). * Huurdeman, Anton A. ''The Worldwide History of Telecommunications'' (John Wiley & Sons, 2003) * Richard R. John, John, Richard R. ''Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications'' (Harvard University Press; 2010) 520 pages; the evolution of American telegraph and telephone networks. * Kieve, Jeffrey L. (1973). ''The Electric Telegraph: a Social and Economic History''. David and Charles. . * Lew, B., and Cater, B. "The Telegraph, Co-ordination of Tramp Shipping, and Growth in World Trade, 1870ŌĆō1910", ''European Review of Economic History'' 10 (2006): 147ŌĆō73. * M├╝ller, Simone M., and Heidi JS Tworek. "'The telegraph and the bank': on the interdependence of global communications and capitalism, 1866ŌĆō1914." ''Journal of Global History'' 10#2 (2015): 259ŌĆō283. * O'Hara, Glen. "New Histories of British Imperial Communication and the 'Networked World' of the 19th and Early 20th Centuries" ''History Compass'' (2010) 8#7pp 609ŌĆō625, Historiography, * Richardson, Alan J. "The cost of a telegram: Accounting and the evolution of international regulation of the telegraph." ''Accounting History'' 20#4 (2015): 405ŌĆō429. * Tom Standage, Standage, Tom (1998). ''The Victorian Internet''. Berkley Trade. . * Thompson, Robert Luther. ''Wiring a continent: The history of the telegraph industry in the United States, 1832ŌĆō1866'' (Princeton UP, 1947). * Wenzlhuemer, Roland. "The Development of Telegraphy, 1870ŌĆō1900: A European Perspective on a World History Challenge." ''History Compass'' 5#5 (2007): 1720ŌĆō1742. * Wenzlhuemer, Roland. ''Connecting the nineteenth-century world: The telegraph and globalization'' (Cambridge UP, 2013)

online review

* Winseck, Dwayne R., and Robert M. Pike. ''Communication & Empire: Media, Markets & Globalization, 1860ŌĆō1930'' (2007), 429pp. * The Victorian Internet, ''The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century's On-Line Pioneers'', a book about the telegraph

HOW TO WRITE TELEGRAMS PROPERLY

The Telegraph Office (1928) * Wheen, Andrew;ŌĆö ''DOT-DASH TO DOT.COM: How Modern Telecommunications Evolved from the Telegraph to the Internet'' (Springer, 2011) . * Wilson, Geoffrey, ''The Old Telegraphs'', Phillimore & Co Ltd 1976 ; a comprehensive history of the shutter, semaphore and other kinds of visual mechanical telegraphs.

Britannica Encyclopedia - Telegraph

The Porthcurno Telegraph Museum

The biggest Telegraph station in the world, now a museum

Distant Writing

ĆöThe History of the Telegraph Companies in Britain between 1838 and 1868

Western Union Telegraph Company Records, 1820ŌĆō1995

Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Early telegraphy and fax engineering, still operable in a German computer museum

''The New York Times'', 6 February 2006

International Facilities of the American Carriers

ŌĆō an overview of the U.S. international cable network in 1950 *Elizabeth Bruton

Communication Technology

in

{{Authority control Telegraphy, Telecommunications

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore

Flag semaphore (from the Ancient Greek () 'sign' and - (-) '-bearer') is a semaphore system conveying information at a distance by means of visual signals with hand-held flags, rods, disks, paddles, or occasionally bare or gloved hands. Inform ...

is a method of telegraphy, whereas pigeon post

Pigeon post is the use of homing pigeons to carry messages. Pigeons are effective as messengers due to their natural homing abilities. The pigeons are transported to a destination in cages, where they are attached with messages, then the pigeo ...

is not. Ancient signal

In signal processing, a signal is a function that conveys information about a phenomenon. Any quantity that can vary over space or time can be used as a signal to share messages between observers. The '' IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing' ...

ling systems, although sometimes quite extensive and sophisticated as in China, were generally not capable of transmitting arbitrary text messages. Possible messages were fixed and predetermined and such systems are thus not true telegraphs.

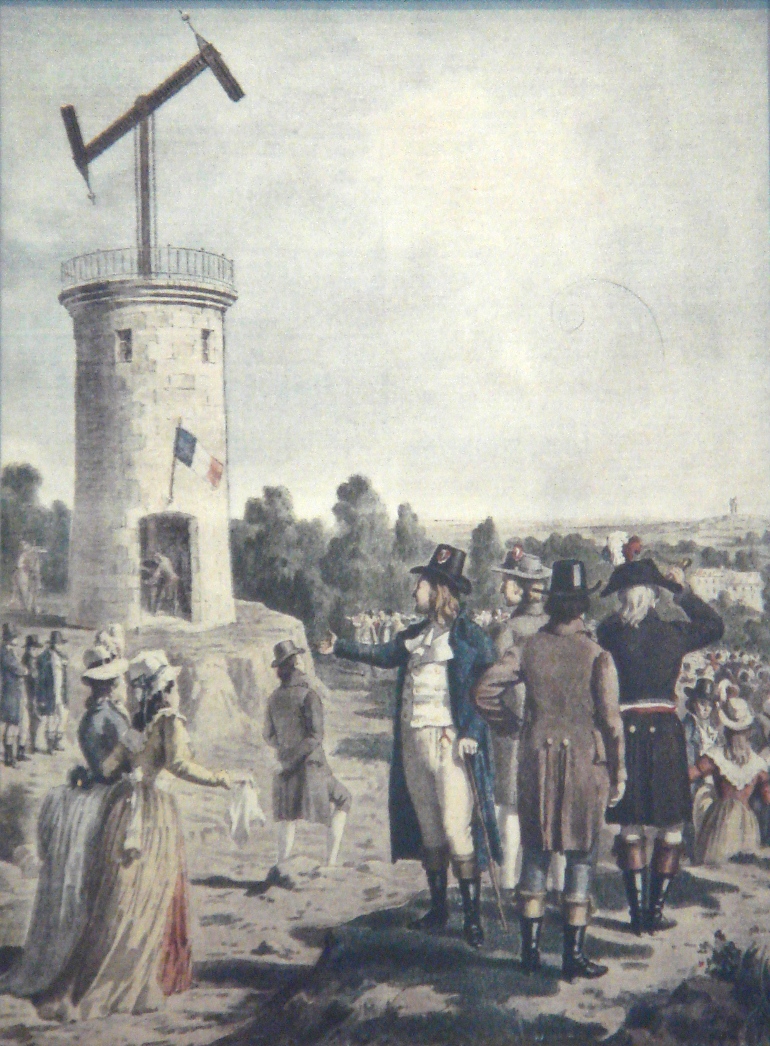

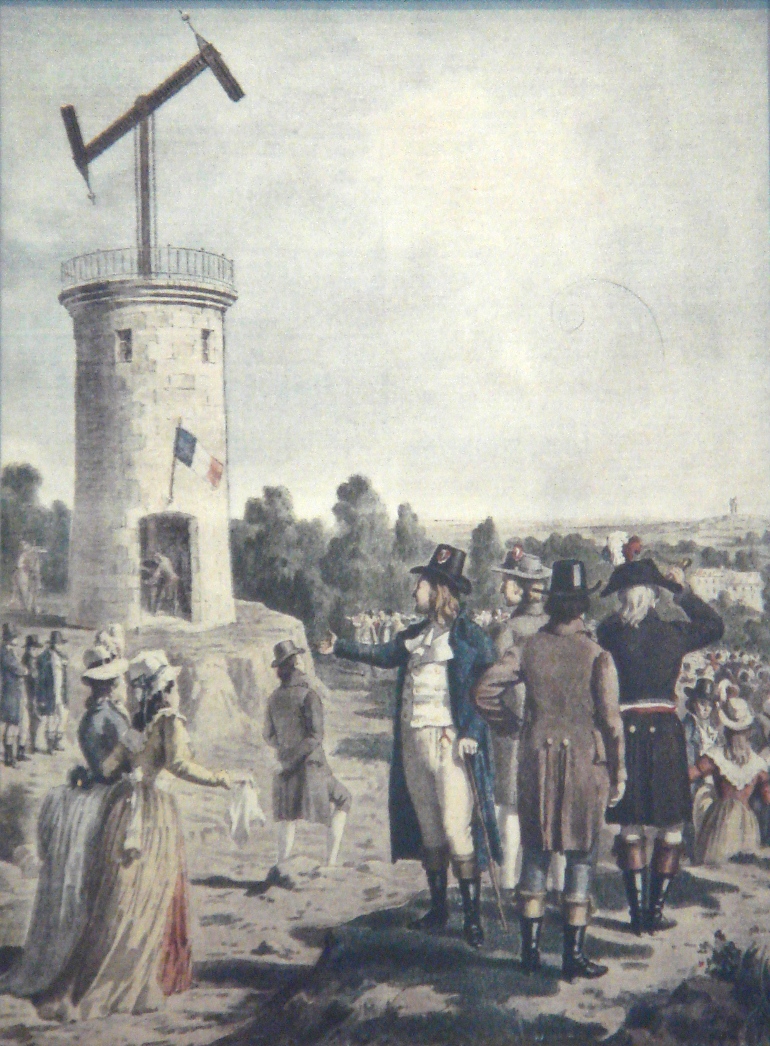

The earliest true telegraph put into widespread use was the optical telegraph

An optical telegraph is a line of stations, typically towers, for the purpose of conveying textual information by means of visual signals. There are two main types of such systems; the semaphore telegraph which uses pivoted indicator arms and ...

of Claude Chappe

Claude Chappe (; 25 December 1763 ŌĆō 23 January 1805) was a French inventor who in 1792 demonstrated a practical semaphore system that eventually spanned all of France. His system consisted of a series of towers, each within line of sight of ...

, invented in the late 18th century. The system was used extensively in France, and European nations occupied by France, during the Napoleonic era

The Napoleonic era is a period in the history of France and Europe. It is generally classified as including the fourth and final stage of the French Revolution, the first being the National Assembly, the second being the Legislative ...

. The electric telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems ...

started to replace the optical telegraph in the mid-19th century. It was first taken up in Britain in the form of the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph

The Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph was an early electrical telegraph system dating from the 1830s invented by English inventor William Fothergill Cooke and English scientist Charles Wheatstone. It was a form of needle telegraph, and the first te ...

, initially used mostly as an aid to railway signalling

Railway signalling (), also called railroad signaling (), is a system used to control the movement of railway traffic. Trains move on fixed rails, making them uniquely susceptible to collision. This susceptibility is exacerbated by the enormou ...

. This was quickly followed by a different system developed in the United States by Samuel Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 ŌĆō April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph ...

. The electric telegraph was slower to develop in France due to the established optical telegraph system, but an electrical telegraph was put into use with a code compatible with the Chappe optical telegraph. The Morse system was adopted as the international standard in 1865, using a modified Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one of ...

developed in Germany in 1848.

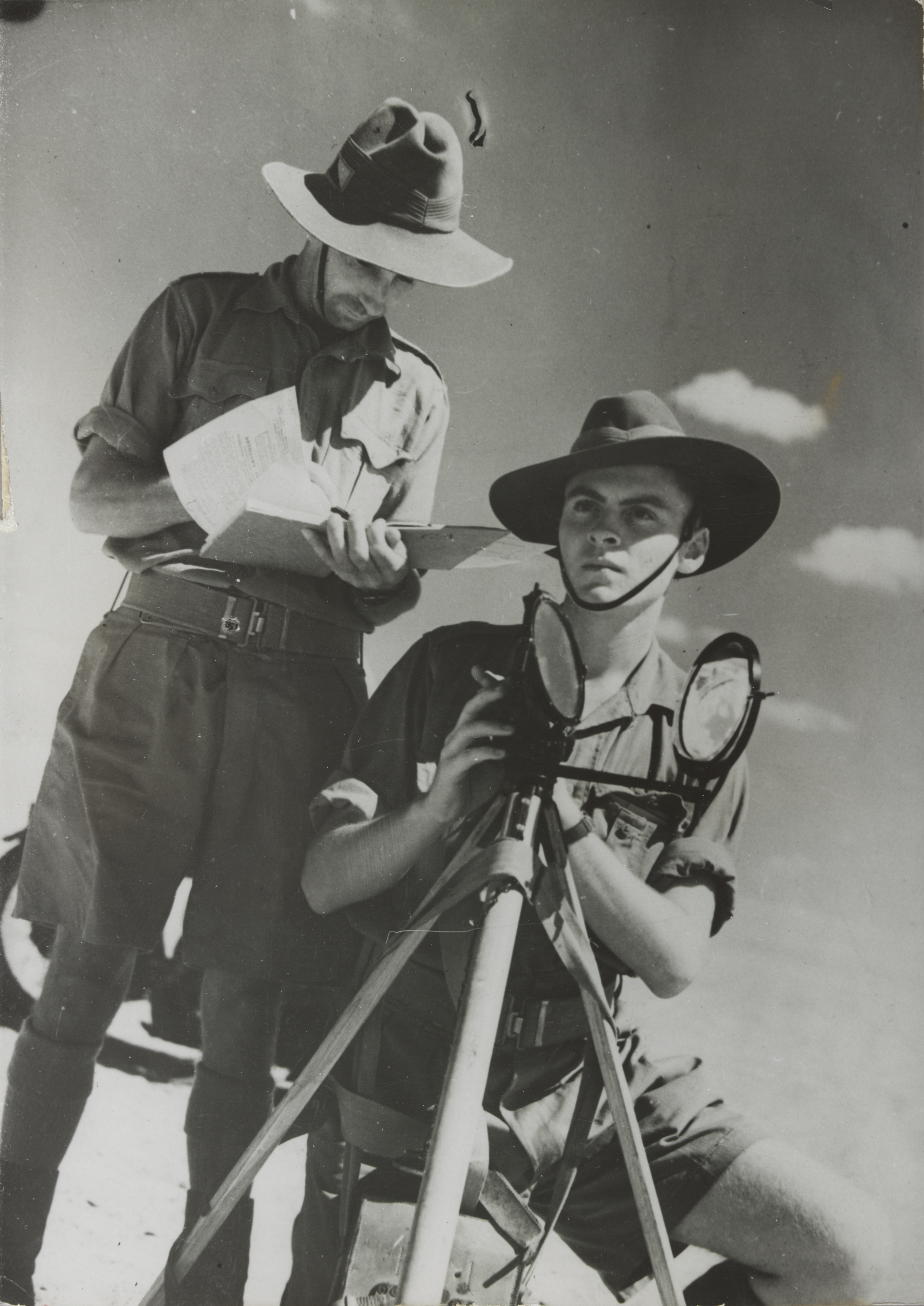

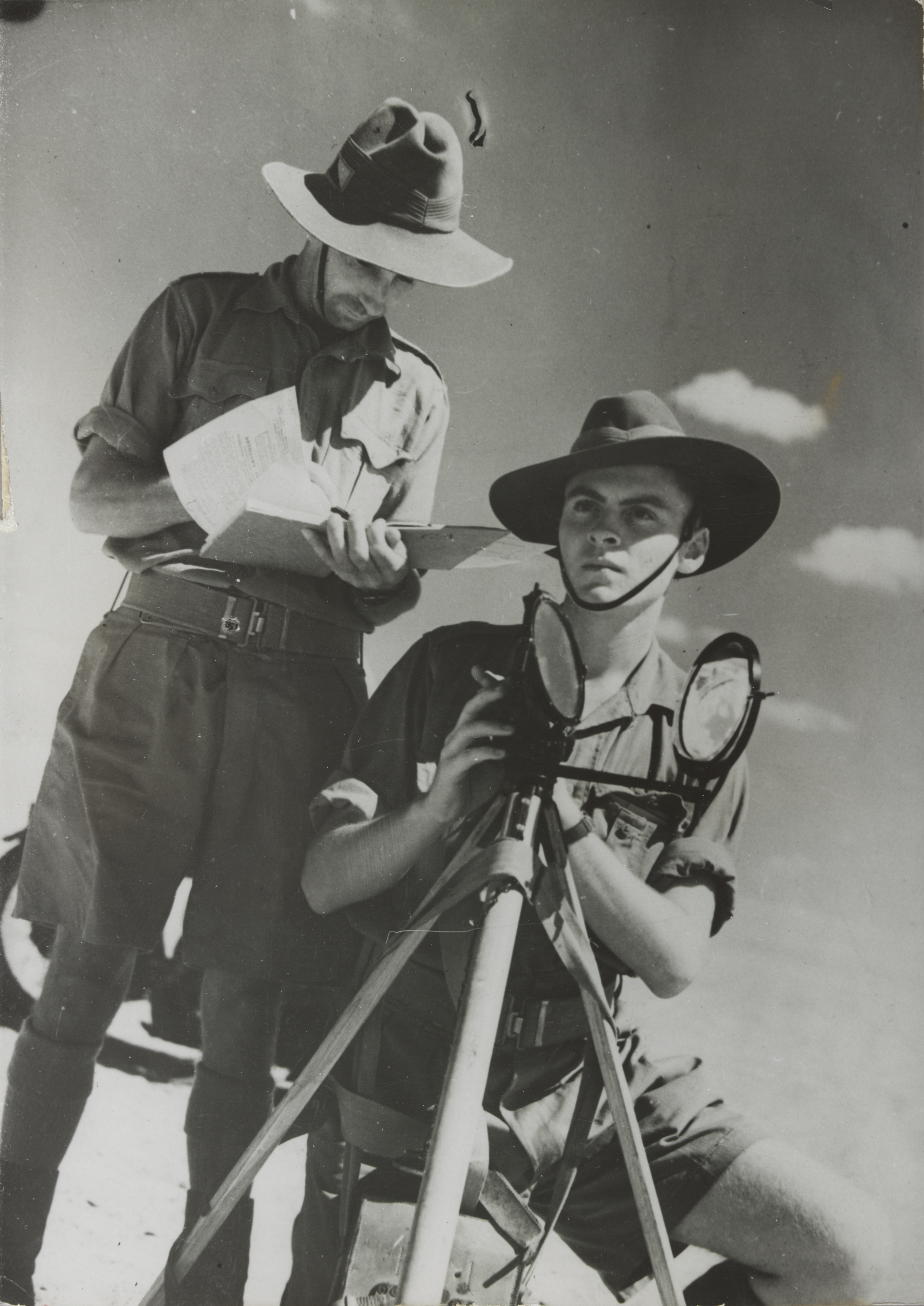

The heliograph

A heliograph () is a semaphore system that signals by flashes of sunlight (generally using Morse code) reflected by a mirror. The flashes are produced by momentarily pivoting the mirror, or by interrupting the beam with a shutter. The heliograp ...

is a telegraph system using reflected sunlight for signalling. It was mainly used in areas where the electrical telegraph had not been established and generally used the same code. The most extensive heliograph network established was in Arizona and New Mexico during the Apache Wars

The Apache Wars were a series of armed conflicts between the United States Army and various Apache tribal confederations fought in the southwest between 1849 and 1886, though minor hostilities continued until as late as 1924. After the Mexic ...

. The heliograph was standard military equipment as late as World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesŌĆöincluding all of the great powersŌĆöforming two opposin ...

. Wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for ...

developed in the early 20th century became important for maritime use, and was a competitor to electrical telegraphy using submarine telegraph cable

A submarine communications cable is a cable laid on the sea bed between land-based stations to carry telecommunication signals across stretches of ocean and sea. The first submarine communications cables laid beginning in the 1850s carried tel ...

s in international communications.

Telegrams became a popular means of sending messages once telegraph prices had fallen sufficiently. Traffic became high enough to spur the development of automated systemsŌĆöteleprinter

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint configurations. Initia ...

s and punched tape

Five- and eight-hole punched paper tape

Paper tape reader on the Harwell computer with a small piece of five-hole tape connected in a circle ŌĆō creating a physical program loop

Punched tape or perforated paper tape is a form of data storage ...

transmission. These systems led to new telegraph code

A telegraph code is one of the character encodings used to transmit information by telegraphy. Morse code is the best-known such code. ''Telegraphy'' usually refers to the electrical telegraph, but telegraph systems using the optical telegraph w ...

s, starting with the Baudot code

The Baudot code is an early character encoding for telegraphy invented by ├ēmile Baudot in the 1870s. It was the predecessor to the International Telegraph Alphabet No. 2 (ITA2), the most common teleprinter code in use until the advent of ASCII ...

. However, telegrams were never able to compete with the letter post on price, and competition from the telephone

A telephone is a telecommunications device that permits two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most efficiently the human voice, into e ...

, which removed their speed advantage, drove the telegraph into decline from 1920 onwards. The few remaining telegraph applications were largely taken over by alternatives on the internet

The Internet (or internet) is the global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a '' network of networks'' that consists of private, pub ...

towards the end of the 20th century.

Terminology

The word ''telegraph'' (fromAncient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

: () 'at a distance' and () 'to write') was first coined by the French inventor of the semaphore telegraph

Semaphore (; ) is the use of an apparatus to create a visual signal transmitted over distance. A semaphore can be performed with devices including: fire, lights, flags, sunlight, and moving arms. Semaphores can be used for telegraphy when ar ...

, Claude Chappe

Claude Chappe (; 25 December 1763 ŌĆō 23 January 1805) was a French inventor who in 1792 demonstrated a practical semaphore system that eventually spanned all of France. His system consisted of a series of towers, each within line of sight of ...

, who also coined the word '' semaphore''.

A telegraph is a device for transmitting and receiving messages over long distances, i.e., for telegraphy. The word ''telegraph'' alone now generally refers to an electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems ...

. Wireless telegraphy is transmission of messages over radio with telegraphic codes.

Contrary to the extensive definition used by Chappe, Morse argued that the term ''telegraph'' can strictly be applied only to systems that transmit ''and'' record messages at a distance. This is to be distinguished from ''semaphore'', which merely transmits messages. Smoke signals, for instance, are to be considered semaphore, not telegraph. According to Morse, telegraph dates only from 1832 when Pavel Schilling

Baron Pavel Lvovitch Schilling (1786ŌĆō1837), also known as Paul Schilling, was a Russian military officer and diplomat of Baltic German origin. The majority of his career was spent working for the imperial Russian Ministry of Foreign Aff ...

invented one of the earliest electrical telegraphs.

A telegraph message sent by an electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems ...

operator or telegrapher using Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one of ...

(or a printing telegraph

The printing telegraph was invented by Royal Earl House in 1846. House's equipment could transmit around 40 instantly readable words per minute, but was difficult to manufacture in bulk. The printer could copy and print out up to 2,000 words per ...

operator using plain text) was known as a telegram. A cablegram was a message sent by a submarine telegraph cable, often shortened to "cable" or "wire". The suffix -gram is derived from ancient Greek: (), meaning something written, i.e. telegram means something written at a distance and cablegram means something written via a cable, whereas telegraph implies the process of writing at a distance.

Later, a Telex was a message sent by a Telex

The telex network is a station-to-station switched network of teleprinters similar to a Public switched telephone network, telephone network, using telegraph-grade connecting circuits for two-way text-based messages. Telex was a major method of ...

network, a switched network of teleprinter

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint configurations. Initia ...

s similar to a telephone network.

A wirephoto

Wirephoto, telephotography or radiophoto is the sending of pictures by telegraph, telephone or radio.

├ēdouard Belin's B├®linographe of 1913, which scanned using a photocell and transmitted over ordinary phone lines, formed the basis for the W ...

or wire picture was a newspaper picture that was sent from a remote location by a facsimile telegraph. A diplomatic telegram, also known as a diplomatic cable

A diplomatic cable, also known as a diplomatic telegram (DipTel) or embassy cable, is a confidential text-based message exchanged between a diplomatic mission, like an embassy or a consulate, and the foreign ministry of its parent country.Defi ...

, is a confidential communication between a diplomatic mission

A diplomatic mission or foreign mission is a group of people from a state or organization present in another state to represent the sending state or organization officially in the receiving or host state. In practice, the phrase usually deno ...

and the foreign ministry In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The entit ...

of its parent country. These continue to be called telegrams or cables regardless of the method used for transmission.

History

Early signalling

Passing messages by signalling over distance is an ancient practice. One of the oldest examples is the signal towers of the

Passing messages by signalling over distance is an ancient practice. One of the oldest examples is the signal towers of the Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand ''li'' wall") is a series of fortifications that were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against various nomadic grou ...

. In , signals could be sent by beacon fires or drum beats

A drum beat or drum pattern is a rhythmic pattern, or repeated rhythm establishing the meter and groove through the pulse and subdivision, played on drum kits and other percussion instruments. As such a "beat" consists of multiple drum strokes ...

. By complex flag signalling had developed, and by the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC ŌĆō 9 AD, 25ŌĆō220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221ŌĆō207 BC) and a warr ...

(200 BC ŌĆō 220 AD) signallers had a choice of lights, flags, or gunshots to send signals. By the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690ŌĆō705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

(618ŌĆō907) a message could be sent in 24 hours. The Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

(1368ŌĆō1644) added artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

to the possible signals. While the signalling was complex (for instance, different-coloured flags could be used to indicate enemy strength), only predetermined messages could be sent. The Chinese signalling system extended well beyond the Great Wall. Signal towers away from the wall were used to give early warning of an attack. Others were built even further out as part of the protection of trade routes, especially the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and reli ...

.

Signal fires were widely used in Europe and elsewhere for military purposes. The Roman army made frequent use of them, as did their enemies, and the remains of some of the stations still exist. Few details have been recorded of European/Mediterranean signalling systems and the possible messages. One of the few for which details are known is a system invented by Aeneas Tacticus

Aeneas Tacticus ( grc-gre, ╬æß╝░╬Į╬Ą╬»╬▒Žé ßĮü ╬ż╬▒╬║Žä╬╣╬║ŽīŽé; fl. 4th century BC) was one of the earliest Greek writers on the art of war and is credited as the first author to provide a complete guide to securing military communications. Po ...

(4th century BC). Tacticus's system had water filled pots at the two signal stations which were drained in synchronisation. Annotation on a floating scale indicated which message was being sent or received. Signals sent by means of torch

A torch is a stick with combustible material at one end, which is ignited and used as a light source. Torches have been used throughout history, and are still used in processions, symbolic and religious events, and in juggling entertainment. In ...

es indicated when to start and stop draining to keep the synchronisation.David L. Woods, "Ancient signals", pp. 24ŌĆō25 in, Christopher H. Sterling (ed), ''Military Communications: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century'', ABC-CLIO, 2008 .

None of the signalling systems discussed above are true telegraphs in the sense of a system that can transmit arbitrary messages over arbitrary distances. Lines of signalling relay

A relay

Electromechanical relay schematic showing a control coil, four pairs of normally open and one pair of normally closed contacts

An automotive-style miniature relay with the dust cover taken off

A relay is an electrically operated switch ...

stations can send messages to any required distance, but all these systems are limited to one extent or another in the range of messages that they can send. A system like flag semaphore

Flag semaphore (from the Ancient Greek () 'sign' and - (-) '-bearer') is a semaphore system conveying information at a distance by means of visual signals with hand-held flags, rods, disks, paddles, or occasionally bare or gloved hands. Inform ...

, with an alphabetic code, can certainly send any given message, but the system is designed for short-range communication between two persons. An engine order telegraph

An engine order telegraph or E.O.T., also referred to as a Chadburn, is a communications device used on a ship (or submarine) for the pilot on the bridge to order engineers in the engine room to power the vessel at a certain desired speed.

C ...

, used to send instructions from the bridge of a ship to the engine room, fails to meet both criteria; it has a limited distance and very simple message set. There was only one ancient signalling system described that ''does'' meet these criteria. That was a system using the Polybius square

The Polybius square, also known as the Polybius checkerboard, is a device invented by the ancient Greeks Cleoxenus and Democleitus, and made famous by the historian and scholar Polybius. The device is used for fractionating plaintext characters s ...

to encode an alphabet. Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, ╬Ā╬┐╬╗ŽŹ╬▓╬╣╬┐Žé, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264ŌĆō146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

(2nd century BC) suggested using two successive groups of torches to identify the coordinates of the letter of the alphabet being transmitted. The number of said torches held up signalled the grid square that contained the letter. There is no definite record of the system ever being used, but there are several passages in ancient texts that some think are suggestive. Holzmann and Pehrson, for instance, suggest that Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC ŌĆō AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Ancient Rome, Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditiona ...

is describing its use by Philip V of Macedon

Philip V ( grc-gre, ╬”╬»╬╗╬╣ŽĆŽĆ╬┐Žé ; 238ŌĆō179 BC) was king ( Basileus) of Macedonia from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of the Roman Republic. He would lead Macedon ag ...

in 207 BC during the First Macedonian War

The First Macedonian War (214ŌĆō205 BC) was fought by Rome, allied (after 211 BC) with the Aetolian League and Attalus I of Pergamon, against Philip V of Macedon, contemporaneously with the Second Punic War (218ŌĆō201 BC) against Carthage. The ...

. Nothing else that could be described as a true telegraph existed until the 17th century. Possibly the first alphabetic telegraph code

A telegraph code is one of the character encodings used to transmit information by telegraphy. Morse code is the best-known such code. ''Telegraphy'' usually refers to the electrical telegraph, but telegraph systems using the optical telegraph w ...

in the modern era is due to Franz Kessler

Franz Kessler (c. 1580ŌĆō1650) was a portrait painter, scholar, inventor and alchemist living in the Holy Roman Empire during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Writing

He wrote a number of books and pamphlets: a book on stoves, on making sundials ...

who published his work in 1616. Kessler used a lamp placed inside a barrel with a moveable shutter operated by the signaller. The signals were observed at a distance with the newly invented telescope.

Drum telegraph

In several places around the world, a system of passing messages from village to village using drum beats was used, particularly highly developed in Africa. At the time Europeans discovered "talking drums", the speed of message transmission was faster than any existing European system usingoptical telegraph

An optical telegraph is a line of stations, typically towers, for the purpose of conveying textual information by means of visual signals. There are two main types of such systems; the semaphore telegraph which uses pivoted indicator arms and ...

s. The African drum system was not alphabetical. Rather, the drum beats followed the tones of the language. This made messages highly ambiguous and context was important for their correct interpretation.

Optical telegraph

An

An optical telegraph

An optical telegraph is a line of stations, typically towers, for the purpose of conveying textual information by means of visual signals. There are two main types of such systems; the semaphore telegraph which uses pivoted indicator arms and ...

is a telegraph consisting of a line of stations in towers or natural high points which signal to each other by means of shutters or paddles. Signalling by means of indicator pointers was called ''semaphore''. Early proposals for an optical telegraph system were made to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

by Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

in 1684 and were first implemented on an experimental level by Sir Richard Lovell Edgeworth

Richard Lovell Edgeworth (31 May 1744 ŌĆō 13 June 1817) was an Anglo-Irish politician, writer and inventor.

Biography

Edgeworth was born in Pierrepont Street, Bath, England, son of Richard Edgeworth senior, and great-grandson of Sir Sal ...

in 1767. The first successful optical telegraph network was invented by Claude Chappe

Claude Chappe (; 25 December 1763 ŌĆō 23 January 1805) was a French inventor who in 1792 demonstrated a practical semaphore system that eventually spanned all of France. His system consisted of a series of towers, each within line of sight of ...

and operated in France from 1793. The two most extensive systems were Chappe's in France, with branches into neighbouring countries, and the system of Abraham Niclas Edelcrantz

Abraham Niclas (Clewberg) Edelcrantz (28 July 1754 – 15 March 1821) was a Finnish born Swedish poet and inventor. He was a member of the Swedish Academy, chair 2, from 1786 to 1821.

Edelcrantz was the librarian at The Royal Academy of T ...

in Sweden.Gerard J. Holzmann; Bj├Črn Pehrson, ''The Early History of Data Networks'', IEEE Computer Society Press, 1995 .

During 1790ŌĆō1795, at the height of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, France needed a swift and reliable communication system to thwart the war efforts of its enemies. In 1790, the Chappe brothers set about devising a system of communication that would allow the central government to receive intelligence and to transmit orders in the shortest possible time. On 2 March 1791, at 11 am, they sent the message "si vous r├®ussissez, vous serez bient├┤t couverts de gloire" (If you succeed, you will soon bask in glory) between Brulon and Parce, a distance of . The first means used a combination of black and white panels, clocks, telescopes, and codebooks to send their message.

In 1792, Claude was appointed ''Ing├®nieur-T├®l├®graphiste'' and charged with establishing a line of stations between Paris and Lille

Lille ( , ; nl, Rijsel ; pcd, Lile; vls, Rysel) is a city in the northern part of France, in French Flanders. On the river De├╗le, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, region, the Pref ...

, a distance of . It was used to carry dispatches for the war between France and Austria. In 1794, it brought news of a French capture of Cond├®-sur-l'Escaut

Cond├®-sur-l'Escaut (, literally ''Cond├® on the Escaut''; pcd, Cond├®-su-l'Escaut) is a commune of the Nord department in northern France.

It lies on the border with Belgium. The population as of 1999 was 10,527. Residents of the area are kno ...

from the Austrians less than an hour after it occurred. A decision to replace the system with an electric telegraph was made in 1846, but it took a decade before it was fully taken out of service. The fall of Sebastopol was reported by Chappe telegraph in 1855.

The Prussian system was put into effect in the 1830s. However, they were highly dependent on good weather and daylight to work and even then could accommodate only about two words per minute. The last commercial semaphore link ceased operation in Sweden in 1880. As of 1895, France still operated coastal commercial semaphore telegraph stations, for ship-to-shore communication.

Electrical telegraph

The early ideas for an electric telegraph included in 1753 using

The early ideas for an electric telegraph included in 1753 using electrostatic

Electrostatics is a branch of physics that studies electric charges at rest (static electricity).

Since classical times, it has been known that some materials, such as amber, attract lightweight particles after rubbing. The Greek word for amber ...

deflections of pith

Pith, or medulla, is a tissue in the stems of vascular plants. Pith is composed of soft, spongy parenchyma cells, which in some cases can store starch. In eudicotyledons, pith is located in the center of the stem. In monocotyledons, it ext ...

balls, proposals for electrochemical

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between electrical potential difference, as a measurable and quantitative phenomenon, and identifiable chemical change, with the potential difference as an outc ...

bubbles in acid by Campillo in 1804 and von S├Čmmering in 1809. The first experimental system over a substantial distance was by Ronalds in 1816 using an electrostatic generator

An electrostatic generator, or electrostatic machine, is an electrical generator that produces ''static electricity'', or electricity at high voltage and low continuous current. The knowledge of static electricity dates back to the earliest ci ...

. Ronalds offered his invention to the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral ŌĆō one of the Great Officers of State. For much of it ...

, but it was rejected as unnecessary, the existing optical telegraph connecting the Admiralty in London to their main fleet base in Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

being deemed adequate for their purposes. As late as 1844, after the electrical telegraph had come into use, the Admiralty's optical telegraph was still used, although it was accepted that poor weather ruled it out on many days of the year. France had an extensive optical telegraph dating from Napoleonic times and was even slower to take up electrical systems.

Eventually, electrostatic telegraphs were abandoned in favour of electromagnet

An electromagnet is a type of magnet in which the magnetic field is produced by an electric current. Electromagnets usually consist of wire wound into a coil. A current through the wire creates a magnetic field which is concentrated in the ...

ic systems. An early experimental system (Schilling Schilling may refer to:

* Schilling (unit), an historical unit of measurement

* Schilling (coin), the historical European coin

* Austrian schilling, the former currency of Austria

* A. Schilling & Company, an historical West Coast spice firm acquir ...

, 1832) led to a proposal to establish a telegraph between St Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, ąĪą░ąĮą║čé-ą¤ąĄč鹥čĆą▒čāčĆą│, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=╦łsankt p╩▓╔¬t╩▓╔¬r╦łburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914ŌĆō1924) and later Leningrad (1924ŌĆō1991), i ...

and Kronstadt

Kronstadt (russian: ąÜčĆąŠąĮčłčéą░╠üą┤čé, Kronshtadt ), also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt or Kron┼Īt├Īdt (from german: link=no, Krone for "crown" and ''Stadt'' for "city") is a Russian port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city of ...

, but it was never completed. The first operative electric telegraph (Gauss

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (; german: Gau├¤ ; la, Carolus Fridericus Gauss; 30 April 177723 February 1855) was a German mathematician and physicist who made significant contributions to many fields in mathematics and science. Sometimes refer ...

and Weber, 1833) connected G├Čttingen Observatory

G├Čttingen Observatory (''Universit├żtssternwarte G├Čttingen'' (G├Čttingen University Observatory) or ''k├Čnigliche Sternwarte G├Čttingen'' (Royal Observatory G├Čttingen)) is a German astronomical observatory located in G├Čttingen, Lower Saxony, Ge ...

to the Institute of Physics about 1 km away during experimental investigations of the geomagnetic field.

The first commercial telegraph was by Cooke

Cooke is a surname derived from the occupation of cook. Notable people with the surname include:

* Alexander Cooke (died 1614), English actor

* Alfred Tyrone Cooke, of the Indo-Pakistani wars

* Alistair Cooke KBE (1908ŌĆō2004), British-American j ...

and Wheatstone following their English patent of 10 June 1837. It was demonstrated on the London and Birmingham Railway

The London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR) was a railway company in the United Kingdom, in operation from 1833 to 1846, when it became part of the London and North Western Railway (L&NWR).

The railway line which the company opened in 1838, betw ...

in July of the same year. In July 1839, a five-needle, five-wire system was installed to provide signalling over a record distance of 21 km on a section of the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran ...

between London Paddington station

Paddington, also known as London Paddington, is a Central London railway terminus and London Underground station complex, located on Praed Street in the Paddington area. The site has been the London terminus of services provided by the Great W ...

and West Drayton.Anton A. Huurdeman, ''The Worldwide History of Telecommunications'' (2003) pp. 67ŌĆō69 However, in trying to get railway companies to take up his telegraph more widely for railway signalling

Railway signalling (), also called railroad signaling (), is a system used to control the movement of railway traffic. Trains move on fixed rails, making them uniquely susceptible to collision. This susceptibility is exacerbated by the enormou ...

, Cooke was rejected several times in favour of the more familiar, but shorter range, steam-powered pneumatic signalling. Even when his telegraph was taken up, it was considered experimental and the company backed out of a plan to finance extending the telegraph line out to Slough

Slough () is a town and unparished area in the unitary authority of the same name in Berkshire, England, bordering west London. It lies in the Thames Valley, west of central London and north-east of Reading, at the intersection of the M4 ...

. However, this led to a breakthrough for the electric telegraph, as up to this point the Great Western had insisted on exclusive use and refused Cooke permission to open public telegraph offices. Cooke extended the line at his own expense and agreed that the railway could have free use of it in exchange for the right to open it up to the public.

Most of the early electrical systems required multiple wires (Ronalds' system was an exception), but the system developed in the United States by

Most of the early electrical systems required multiple wires (Ronalds' system was an exception), but the system developed in the United States by Morse

Morse may refer to:

People

* Morse (surname)

* Morse Goodman (1917-1993), Anglican Bishop of Calgary, Canada

* Morse Robb (1902ŌĆō1992), Canadian inventor and entrepreneur

Geography Antarctica

* Cape Morse, Wilkes Land

* Mount Morse, Churchi ...

and Vail

Vail is a home rule municipality in Eagle County, Colorado, United States. The population of the town was 4,835 in 2020. Home to Vail Ski Resort, the largest ski mountain in Colorado, the town is known for its hotels, dining, and for the numer ...

was a single-wire system. This was the system that first used the soon-to-become-ubiquitous Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one of ...

. By 1844, the Morse system connected Baltimore to Washington, and by 1861 the west coast of the continent was connected to the east coast. The Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph

The Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph was an early electrical telegraph system dating from the 1830s invented by English inventor William Fothergill Cooke and English scientist Charles Wheatstone. It was a form of needle telegraph, and the first te ...

, in a series of improvements, also ended up with a one-wire system, but still using their own code and needle displays.

The electric telegraph quickly became a means of more general communication. The Morse system was officially adopted as the standard for continental European telegraphy in 1851 with a revised code, which later became the basis of International Morse Code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one of ...

.Lewis Coe, ''The Telegraph: A History of Morse's Invention and Its Predecessors in the United States'', McFarland, p. 69, 2003 . However, Great Britain and the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

continued to use the Cooke and Wheatstone system, in some places as late as the 1930s. Likewise, the United States continued to use American Morse code

American Morse Code ŌĆö also known as Railroad MorseŌĆöis the latter-day name for the original version of the Morse Code developed in the mid-1840s, by Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail for their electric telegraph. The "American" qualifier was added ...

internally, requiring translation operators skilled in both codes for international messages.

Railway telegraphy

Railway signal telegraphy was developed in Britain from the 1840s onward. It was used to manage railway traffic and to prevent accidents as part of the railway signalling system. On 12 June 1837 Cooke and Wheatstone were awarded a patent for an electric telegraph. This was demonstrated between

Railway signal telegraphy was developed in Britain from the 1840s onward. It was used to manage railway traffic and to prevent accidents as part of the railway signalling system. On 12 June 1837 Cooke and Wheatstone were awarded a patent for an electric telegraph. This was demonstrated between Euston railway station

Euston railway station ( ; also known as London Euston) is a central London railway terminus in the London Borough of Camden, managed by Network Rail. It is the southern terminus of the West Coast Main Line, the UK's busiest inter-city railw ...

ŌĆöwhere Wheatstone was locatedŌĆöand the engine house at Camden TownŌĆöwhere Cooke was stationed, together with Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS HFRSE FRSA Doctor of Civil Law, DCL (16 October 1803 ŌĆō 12 October 1859) was an English civil engineer and designer of locomotives. The only son of George Stephenson, the "Father of Railway ...

, the London and Birmingham Railway

The London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR) was a railway company in the United Kingdom, in operation from 1833 to 1846, when it became part of the London and North Western Railway (L&NWR).

The railway line which the company opened in 1838, betw ...

line's chief engineer. The messages were for the operation of the rope-haulage system for pulling trains up the 1 in 77 bank. The world's first permanent railway telegraph was completed in July 1839 between London Paddington and West Drayton on the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran ...

with an electric telegraph using a four-needle system.

The concept of a signalling "block" system was proposed by Cooke in 1842. Railway signal telegraphy did not change in essence from Cooke's initial concept for more than a century. In this system each line of railway was divided into sections or blocks of varying length. Entry to and exit from the block was to be authorised by electric telegraph and signalled by the line-side semaphore signals, so that only a single train could occupy the rails. In Cooke's original system, a single-needle telegraph was adapted to indicate just two messages: "Line Clear" and "Line Blocked". The signaller

A signaller, signalman, colloquially referred to as a radioman or signaleer in the armed forces is a specialist soldier, sailor or airman responsible for military communications. Signallers, a.k.a. Combat Signallers or signalmen or women, are ...

would adjust his line-side signals accordingly. As first implemented in 1844 each station had as many needles as there were stations on the line, giving a complete picture of the traffic. As lines expanded, a sequence of pairs of single-needle instruments were adopted, one pair for each block in each direction.

Wigwag

Wigwag is a form of flag signalling using a single flag. Unlike most forms of flag signalling, which are used over relatively short distances, wigwag is designed to maximise the distance coveredŌĆöup to in some cases. Wigwag achieved this by using a large flagŌĆöa single flag can be held with both hands unlike flag semaphore which has a flag in each handŌĆöand using motions rather than positions as its symbols since motions are more easily seen. It was invented by US Army surgeonAlbert J. Myer

Albert James Myer (September 20, 1828 ŌĆō August 24, 1880) was a surgeon and United States Army general. He is known as the father of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, as its first chief signal officer just prior to the American Civil War, the inventor ...

in the 1850s who later became the first head of the Signal Corps. Wigwag was used extensively during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 ŌĆō May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

where it filled a gap left by the electrical telegraph. Although the electrical telegraph had been in use for more than a decade, the network did not yet reach everywhere and portable, ruggedized equipment suitable for military use was not immediately available. Permanent or semi-permanent stations were established during the war, some of them towers of enormous height and the system was extensive enough to be described as a communications network.

Heliograph

A

A heliograph

A heliograph () is a semaphore system that signals by flashes of sunlight (generally using Morse code) reflected by a mirror. The flashes are produced by momentarily pivoting the mirror, or by interrupting the beam with a shutter. The heliograp ...

is a telegraph that transmits messages by flashing sunlight with a mirror, usually using Morse code. The idea for a telegraph of this type was first proposed as a modification of surveying equipment (Gauss

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (; german: Gau├¤ ; la, Carolus Fridericus Gauss; 30 April 177723 February 1855) was a German mathematician and physicist who made significant contributions to many fields in mathematics and science. Sometimes refer ...

, 1821). Various uses of mirrors were made for communication in the following years, mostly for military purposes, but the first device to become widely used was a heliograph with a moveable mirror ( Mance, 1869). The system was used by the French during the 1870ŌĆō71 siege of Paris, with night-time signalling using kerosene lamp

A kerosene lamp (also known as a paraffin lamp in some countries) is a type of lighting device that uses kerosene as a fuel. Kerosene lamps have a wick or mantle as light source, protected by a glass chimney or globe; lamps may be used on a t ...

s as the source of light. An improved version (Begbie, 1870) was used by British military in many colonial wars, including the Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Following the passing of the British North America Act of 1867 forming a federation in Canada, Lord Carnarvon thought that a similar political effort, coupl ...

(1879). At some point, a morse key was added to the apparatus to give the operator the same degree of control as in the electric telegraph.David L. Woods, "Heliograph and mirrors", pp. 208ŌĆō211 in, Christopher H. Sterling (ed), ''Military Communications: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century'', ABC-CLIO, 2008 .

Another type of heliograph was the heliostat

A heliostat (from ''helios'', the Greek word for ''sun'', and ''stat'', as in stationary) is a device that includes a mirror, usually a plane mirror, which turns so as to keep reflecting sunlight toward a predetermined target, compensating ...

or heliotrope fitted with a Colomb shutter. The heliostat was essentially a surveying instrument with a fixed mirror and so could not transmit a code by itself. The term ''heliostat'' is sometimes used as a synonym for ''heliograph'' because of this origin. The Colomb shutter (Bolton

Bolton (, locally ) is a large town in Greater Manchester in North West England, formerly a part of Lancashire. A former mill town, Bolton has been a production centre for textiles since Flemish people, Flemish weavers settled in the area i ...

and Colomb, 1862) was originally invented to enable the transmission of morse code by signal lamp

Signal lamp training during World War II

A signal lamp (sometimes called an Aldis lamp or a Morse lamp) is a semaphore system using a visual signaling device for optical communication, typically using Morse code. The idea of flashing dots and ...

between Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

ships at sea.

The heliograph was heavily used by Nelson A. Miles

Nelson Appleton Miles (August 8, 1839 ŌĆō May 15, 1925) was an American military general who served in the American Civil War, the American Indian Wars, and the SpanishŌĆōAmerican War.

From 1895 to 1903, Miles served as the last Commanding Gen ...

in Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Al─Ł ß╣Żonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

and New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

after he took over command (1886) of the fight against Geronimo

Geronimo ( apm, Goyaa┼é├®, , ; June 16, 1829 ŌĆō February 17, 1909) was a prominent leader and medicine man from the Bedonkohe band of the Ndendahe Apache people. From 1850 to 1886, Geronimo joined with members of three other Central Apache ba ...

and other Apache

The Apache () are a group of culturally related Native American tribes in the Southwestern United States, which include the Chiricahua, Jicarilla, Lipan, Mescalero, Mimbre├▒o, Ndendahe (Bedonkohe or Mogollon and Nednhi or Carrizale├▒o an ...

bands in the Apache Wars

The Apache Wars were a series of armed conflicts between the United States Army and various Apache tribal confederations fought in the southwest between 1849 and 1886, though minor hostilities continued until as late as 1924. After the Mexic ...

. Miles had previously set up the first heliograph line in the US between Fort Keogh

Fort Keogh is a former United States Army post located at the western edge of modern Miles City, in the U.S. state of Montana. It is situated on the south bank of the Yellowstone River, at the mouth of the Tongue River.

Colonel Nelson A. Miles, ...

and Fort Custer in Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

. He used the heliograph to fill in vast, thinly populated areas that were not covered by the electric telegraph. Twenty-six stations covered an area . In a test of the system, a message was relayed in four hours. Miles' enemies used smoke signal

The smoke signal is one of the oldest forms of long-distance communication. It is a form of visual communication used over a long distance. In general smoke signals are used to transmit news, signal danger, or to gather people to a common area ...

s and flashes of sunlight from metal, but lacked a sophisticated telegraph code. The heliograph was ideal for use in the American Southwest due to its clear air and mountainous terrain on which stations could be located. It was found necessary to lengthen the morse dash (which is much shorter in American Morse code than in the modern International Morse code) to aid differentiating from the morse dot.

Use of the heliograph declined from 1915 onwards, but remained in service in Britain and British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

countries for some time. Australian forces used the heliograph as late as 1942 in the Western Desert Campaign of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesŌĆöincluding all of the great powersŌĆöforming two opposin ...

. Some form of heliograph was used by the mujahideen

''Mujahideen'', or ''Mujahidin'' ( ar, ┘ģ┘Åž¼┘Äž¦┘ć┘Éž»┘É┘Ŗ┘å, muj─ühid─½n), is the plural form of ''mujahid'' ( ar, ┘ģž¼ž¦┘ćž», muj─ühid, strugglers or strivers or justice, right conduct, Godly rule, etc. doers of jih─üd), an Arabic term th ...

in the SovietŌĆōAfghan War

The SovietŌĆōAfghan War was a protracted armed conflict fought in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989. It saw extensive fighting between the Soviet Union and the Afghan mujahideen (alongside smaller groups of anti-Soviet ...

(1979ŌĆō1989).

Teleprinter

A teleprinter is a telegraph machine that can send messages from a typewriter-like keyboard and print incoming messages in readable text with no need for the operators to be trained in the telegraph code used on the line. It developed from various earlier printing telegraphs and resulted in improved transmission speeds. The

A teleprinter is a telegraph machine that can send messages from a typewriter-like keyboard and print incoming messages in readable text with no need for the operators to be trained in the telegraph code used on the line. It developed from various earlier printing telegraphs and resulted in improved transmission speeds. The Morse telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems ...

(1837) was originally conceived as a system marking indentations on paper tape. A chemical telegraph making blue marks improved the speed of recording (Bain

Bain may refer to:

People

* Bain (surname), origin and list of people with the surname

* Bain of Tulloch, Scottish family

* Bain Stewart, Australian film producer, husband of Leah Purcell

* Saint Bain (died c.ŌĆē711 AD), Bishop of Th├®rouanne, Ab ...

, 1846), but was delayed by a patent challenge from Morse. The first true printing telegraph (that is printing in plain text) used a spinning wheel of types

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* Typ ...

in the manner of a daisy wheel printer

Daisy wheel printing is an impact printing technology invented in 1970 by Andrew Gabor at Diablo Data Systems. It uses interchangeable pre-formed type elements, each with typically 96 glyphs, to generate high-quality output comparable to pr ...

(House

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

, 1846, improved by Hughes

Hughes may refer to:

People

* Hughes (surname)

* Hughes (given name)

Places Antarctica

* Hughes Range (Antarctica), Ross Dependency

* Mount Hughes, Oates Land

* Hughes Basin, Oates Land

* Hughes Bay, Graham Land

* Hughes Bluff, Victoria La ...

, 1855). The system was adopted by Western Union

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company chang ...

.

Early teleprinters used the Baudot code

The Baudot code is an early character encoding for telegraphy invented by ├ēmile Baudot in the 1870s. It was the predecessor to the International Telegraph Alphabet No. 2 (ITA2), the most common teleprinter code in use until the advent of ASCII ...

, a five-bit sequential binary code. This was a telegraph code developed for use on the French telegraph using a five-key keyboard ( Baudot, 1874). Teleprinters generated the same code from a full alphanumeric keyboard. A feature of the Baudot code, and subsequent telegraph codes, was that, unlike Morse code, every character has a code of the same length making it more machine friendly. The Baudot code was used on the earliest ticker tape

Ticker tape was the earliest electrical dedicated financial communications medium, transmitting stock price information over telegraph lines, in use from around 1870 through 1970. It consisted of a paper strip that ran through a machine called ...

machines ( Calahan, 1867), a system for mass distributing stock price information.Richard E. Smith, ''Elementary Information Security'', p. 433, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2015 .

Automated punched-tape transmission

In a punched-tape system, the message is first typed onto punched tape using the code of the telegraph systemŌĆöMorse code for instance. It is then, either immediately or at some later time, run through a transmission machine which sends the message to the telegraph network. Multiple messages can be sequentially recorded on the same run of tape. The advantage of doing this is that messages can be sent at a steady, fast rate making maximum use of the available telegraph lines. The economic advantage of doing this is greatest on long, busy routes where the cost of the extra step of preparing the tape is outweighed by the cost of providing more telegraph lines. The first machine to use punched tape was Bain's teleprinter (Bain, 1843), but the system saw only limited use. Later versions of Bain's system achieved speeds up to 1000 words per minute, far faster than a human operator could achieve.

The first widely used system (Wheatstone, 1858) was first put into service with the British

In a punched-tape system, the message is first typed onto punched tape using the code of the telegraph systemŌĆöMorse code for instance. It is then, either immediately or at some later time, run through a transmission machine which sends the message to the telegraph network. Multiple messages can be sequentially recorded on the same run of tape. The advantage of doing this is that messages can be sent at a steady, fast rate making maximum use of the available telegraph lines. The economic advantage of doing this is greatest on long, busy routes where the cost of the extra step of preparing the tape is outweighed by the cost of providing more telegraph lines. The first machine to use punched tape was Bain's teleprinter (Bain, 1843), but the system saw only limited use. Later versions of Bain's system achieved speeds up to 1000 words per minute, far faster than a human operator could achieve.

The first widely used system (Wheatstone, 1858) was first put into service with the British General Post Office

The General Post Office (GPO) was the state postal system and telecommunications carrier of the United Kingdom until 1969. Before the Acts of Union 1707, it was the postal system of the Kingdom of England, established by Charles II in 1660. ...

in 1867. A novel feature of the Wheatstone system was the use of bipolar encoding

In telecommunication, bipolar encoding is a type of return-to-zero (RZ) line code, where two nonzero values are used, so that the three values are +, ŌłÆ, and zero. Such a signal is called a duobinary signal. Standard bipolar encodings are designed ...

. That is, both positive and negative polarity voltages were used. Bipolar encoding has several advantages, one of which is that it permits duplex communication. The Wheatstone tape reader was capable of a speed of 400 words per minute.Tom Standage, ''The Victorian Internet'', Berkley, 1999 .

Oceanic telegraph cables

A worldwide communication network meant that telegraph cables would have to be laid across oceans. On land cables could be run uninsulated suspended from poles. Underwater, a good insulator that was both flexible and capable of resisting the ingress of seawater was required. A solution presented itself with

A worldwide communication network meant that telegraph cables would have to be laid across oceans. On land cables could be run uninsulated suspended from poles. Underwater, a good insulator that was both flexible and capable of resisting the ingress of seawater was required. A solution presented itself with gutta-percha

Gutta-percha is a tree of the genus ''Palaquium'' in the family Sapotaceae. The name also refers to the rigid, naturally biologically inert, resilient, electrically nonconductive, thermoplastic latex derived from the tree, particularly from ...

, a natural rubber from the ''Palaquium gutta

''Palaquium gutta'' is a tree in the family Sapotaceae. The specific epithet ' is from the Malay word ''getah'' meaning "sap or latex". It is known in Indonesia as ''karet oblong''.

Description

''Palaquium gutta'' grows up to tall. The bark i ...

'' tree, after William Montgomerie

William Montgomerie (1797ŌĆō1856) was a Scottish military doctor with the East India Company, and later head of the medical department at Singapore. He is best known for promoting the use of gutta-percha in Europe. This material was an import ...

sent samples to London from Singapore in 1843. The new material was tested by Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 ŌĆō 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

and in 1845 Wheatstone suggested that it should be used on the cable planned between Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

and Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

by John Watkins Brett

John Watkins Brett (1805ŌĆō1863) was an English telegraph engineer.

Life

Brett was the son of a cabinetmaker, William Brett of Bristol, and was born in that city in 1805. Brett is known as the founder of submarine telegraphy. He formed the Sub ...

. The idea was proved viable when the South Eastern Railway company successfully tested a gutta-percha insulated cable with telegraph messages to a ship off the coast of Folkestone

Folkestone ( ) is a port town on the English Channel, in Kent, south-east England. The town lies on the southern edge of the North Downs at a valley between two cliffs. It was an important harbour and shipping port for most of the 19th and 20t ...

. The cable to France was laid in 1850 but was almost immediately severed by a French fishing vessel.Solymar, Laszlo. The Effect of the Telegraph on Law and Order, War, Diplomacy, and Power Politics

'' in ''Interdisciplinary Science Reviews'', 2000. Accessed 1 August 2014. It was relaid the next year and connections to Ireland and the

Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, d├®i Niddereg L├żnnereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

soon followed.

Getting a cable across the Atlantic Ocean proved much more difficult. The Atlantic Telegraph Company

The Atlantic Telegraph Company was a company formed on 6 November 1856 to undertake and exploit a commercial telegraph cable across the Atlantic ocean, the first such telecommunications link.

History

Cyrus Field, American businessman and finan ...

, formed in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

in 1856, had several failed attempts. A cable laid in 1858 worked poorly for a few days (sometimes taking all day to send a message despite the use of the highly sensitive mirror galvanometer

A mirror galvanometer is an ammeter that indicates it has sensed an electric current by deflecting a light beam with a mirror. The beam of light projected on a scale acts as a long massless pointer. In 1826, Johann Christian Poggendorff devel ...

developed by William Thomson (the future Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, (26 June 182417 December 1907) was a British mathematician, Mathematical physics, mathematical physicist and engineer born in Belfast. Professor of Natural Philosophy (Glasgow), Professor of Natural Philoso ...

) before being destroyed by applying too high a voltage. Its failure and slow speed of transmission prompted Thomson and Oliver Heaviside

Oliver Heaviside FRS (; 18 May 1850 ŌĆō 3 February 1925) was an English self-taught mathematician and physicist who invented a new technique for solving differential equations (equivalent to the Laplace transform), independently developed vec ...

to find better mathematical descriptions of long transmission line

In electrical engineering, a transmission line is a specialized cable or other structure designed to conduct electromagnetic waves in a contained manner. The term applies when the conductors are long enough that the wave nature of the transmi ...

s. The company finally succeeded in 1866 with an improved cable laid by SS ''Great Eastern'', the largest ship of its day, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 ŌĆō 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "one ...

.

An overland telegraph from Britain to India was first connected in 1866 but was unreliable so a submarine telegraph cable was connected in 1870. Several telegraph companies were combined to form the ''Eastern Telegraph Company'' in 1872. Australia was first linked to the rest of the world in October 1872 by a submarine telegraph cable at Darwin.

From the 1850s until well into the 20th century, British submarine cable systems dominated the world system. This was set out as a formal strategic goal, which became known as the All Red Line

The All Red Line was a system of electrical telegraphs that linked much of the British Empire. It was inaugurated on 31 October 1902. The informal name derives from the common practice of colouring the territory of the British Empire red or ...

. In 1896, there were thirty cable-laying ships in the world and twenty-four of them were owned by British companies. In 1892, British companies owned and operated two-thirds of the world's cables and by 1923, their share was still 42.7 percent. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Britain's telegraph communications were almost completely uninterrupted while it was able to quickly cut Germany's cables worldwide.

Facsimile

In 1843, Scottish inventor Alexander Bain invented a device that could be considered the first

In 1843, Scottish inventor Alexander Bain invented a device that could be considered the first facsimile machine

Fax (short for facsimile), sometimes called telecopying or telefax (the latter short for telefacsimile), is the telephonic transmission of scanned printed material (both text and images), normally to a telephone number connected to a printer o ...

. He called his invention a "recording telegraph". Bain's telegraph was able to transmit images by electrical wires. Frederick Bakewell

Frederick Collier Bakewell (29 September 1800 – 26 September 1869) was an English physicist who improved on the concept of the facsimile machine introduced by Alexander Bain in 1842 and demonstrated a working laboratory version at the 1 ...

made several improvements on Bain's design and demonstrated a telefax machine. In 1855, an Italian abbot, Giovanni Caselli

Giovanni Caselli (8 June 1815 ŌĆō 25 April 1891) was an Italian priest, inventor, and physicist. He studied electricity and magnetism as a child which led to his invention of the pantelegraph (also known as the universal telegraph or all-purpose ...

, also created an electric telegraph that could transmit images. Caselli called his invention "Pantelegraph

The pantelegraph (Italian: ''pantelegrafo''; French: ''pant├®l├®graphe'') was an early form of facsimile machine transmitting over normal telegraph lines developed by Giovanni Caselli, used commercially in the 1860s, that was the first such de ...

". Pantelegraph was successfully tested and approved for a telegraph line between Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km┬▓ (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

and Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lion├®s'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rh├┤ne and Sa├┤ne, to the northwest of t ...

.

In 1881, English inventor Shelford Bidwell

Shelford Bidwell FRS (6 March 1848 ŌĆō 18 December 1909) was an English physicist and inventor. He is best known for his work with "telephotography", a precursor to the modern fax machine.

Private life

He was born in Thetford, Norfolk the elde ...

constructed the ''scanning phototelegraph'' that was the first telefax machine to scan any two-dimensional original, not requiring manual plotting or drawing. Around 1900, German physicist Arthur Korn invented the '' Bildtelegraph'' widespread in continental Europe especially since a widely noticed transmission of a wanted-person photograph from Paris to London in 1908 used until the wider distribution of the radiofax. Its main competitors were the ''B├®linographe'' by ├ēdouard Belin