The type III secretion system (T3SS or TTSS), also called the injectisome, is one of the

The type III secretion system (T3SS or TTSS), also called the injectisome, is one of the bacterial secretion system

Bacterial secretion systems are protein complexes present on the cell membranes of bacteria for secretion of substances. Specifically, they are the cellular devices used by pathogenic bacteria to secrete their virulence factors (mainly of protein ...

s used by bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

to secrete 440px

Secretion is the movement of material from one point to another, such as a secreted chemical substance from a cell or gland. In contrast, excretion is the removal of certain substances or waste products from a cell or organism. The classica ...

their effector proteins into the host's cells to promote virulence

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its ability to ...

and colonisation

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

. The T3SS is a needle-like protein complex found in several species of pathogenic

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a ger ...

gram-negative bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wa ...

.

Overview

The term Type III secretion system was coined in 1993. This secretion system is distinguished from at least five other secretion systems found ingram-negative bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wa ...

. Many animal and plant associated bacteria possess similar T3SSs. These T3SSs are similar as a result of divergent evolution and phylogenetic analysis supports a model in which gram-negative bacteria can transfer the T3SS gene cassette

In biology, a gene cassette is a type of mobile genetic element that contains a gene and a recombination site. Each cassette usually contains a single gene and tends to be very small; on the order of 500–1000 base pairs. They may exist incorpo ...

horizontally to other species. The most researched T3SSs are from species of '' Shigella'' (causes bacillary dysentery), ''Salmonella

''Salmonella'' is a genus of rod-shaped (bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two species of ''Salmonella'' are ''Salmonella enterica'' and '' Salmonella bongori''. ''S. enterica'' is the type species and is fur ...

'' (typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over severa ...

), ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' (),Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. also known as ''E. coli'' (), is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Esc ...

'' (Gut flora

Gut microbiota, gut microbiome, or gut flora, are the microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses that live in the digestive tracts of animals. The gastrointestinal metagenome is the aggregate of all the genomes of the gut ...

, some strains cause food poisoning

Foodborne illness (also foodborne disease and food poisoning) is any illness resulting from the spoilage of contaminated food by pathogenic bacteria, viruses, or parasites that contaminate food,

as well as prions (the agents of mad cow disea ...

), '' Vibrio'' (gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis, also known as infectious diarrhea and gastro, is an inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract including the stomach and intestine. Symptoms may include diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Fever, lack of energy, and dehydrat ...

and diarrhea

Diarrhea, also spelled diarrhoea, is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements each day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration due to fluid loss. Signs of dehydration often begin ...

), ''Burkholderia

''Burkholderia'' is a genus of Pseudomonadota whose pathogenic members include the ''Burkholderia cepacia'' complex, which attacks humans and '' Burkholderia mallei'', responsible for glanders, a disease that occurs mostly in horses and related ...

'' ( glanders), ''Yersinia

''Yersinia'' is a genus of bacteria in the family Yersiniaceae. ''Yersinia'' species are Gram-negative, coccobacilli bacteria, a few micrometers long and fractions of a micrometer in diameter, and are facultative anaerobes. Some members of ''Ye ...

'' ( plague), ''Chlamydia

Chlamydia, or more specifically a chlamydia infection, is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium '' Chlamydia trachomatis''. Most people who are infected have no symptoms. When symptoms do appear they may occur only several w ...

'' (sexually transmitted disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are Transmission (medicine), spread by Human sexual activity, sexual activity, especi ...

), ''Pseudomonas

''Pseudomonas'' is a genus of Gram-negative, Gammaproteobacteria, belonging to the family Pseudomonadaceae and containing 191 described species. The members of the genus demonstrate a great deal of metabolic diversity and consequently are able ...

'' (infects human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

s, animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

s and plant

Plants are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all curr ...

s) and the plant pathogens '' Erwinia'', ''Ralstonia

''Ralstonia'' is a genus of bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few ...

'' and '' Xanthomonas'', and the plant symbiont '' Rhizobium''.

The T3SS is composed of approximately 30 different proteins, making it one of the most complex secretion systems. Its structure shows many similarities with bacterial flagella

A flagellum (; ) is a hairlike appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many protists with flagella are termed as flagellates.

A microorganism may have f ...

(long, rigid, extracellular structures used for motility

Motility is the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy.

Definitions

Motility, the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy, can be contrasted with sessility, the state of organisms th ...

). Some of the proteins participating in T3SS share amino-acid sequence homology to flagellar proteins. Some of the bacteria possessing a T3SS have flagella as well and are motile (''Salmonella'', for instance), and some do not (''Shigella'', for instance). Technically speaking, type III secretion is used both for secreting infection-related proteins and flagellar components. However, the term "type III secretion" is used mainly in relation to the infection apparatus. The bacterial flagellum shares a common ancestor with the type III secretion system.

T3SSs are essential for the pathogenicity (the ability to infect) of many pathogenic bacteria. Defects in the T3SS may render a bacterium non-pathogenic. It has been suggested that some non-invasive strains of gram-negative bacteria have lost the T3SS because the energetically costly system is no longer of use. Although traditional antibiotics

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention ...

were effective against these bacteria in the past, antibiotic-resistant strains constantly emerge. Understanding the way the T3SS works and developing drugs targeting it specifically have become an important goal of many research groups around the world since the late 1990s.

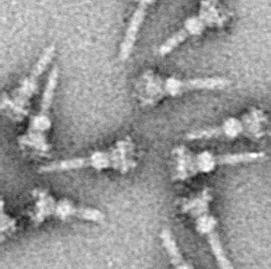

Structure

The hallmark of T3SS is the needle (more generally, the needle complex (NC) or the T3SS apparatus (T3SA); also called injectisome when theATPase

ATPases (, Adenosine 5'-TriPhosphatase, adenylpyrophosphatase, ATP monophosphatase, triphosphatase, SV40 T-antigen, ATP hydrolase, complex V (mitochondrial electron transport), (Ca2+ + Mg2+)-ATPase, HCO3−-ATPase, adenosine triphosphatase) are ...

is excluded; see below). Bacterial proteins that need to be secreted pass from the bacterial cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. ...

through the needle directly into the host cytoplasm. Three membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. ...

s separate the two cytoplasms: the double membranes (inner and outer membranes) of the Gram-negative bacterium and the eukaryotic membrane. The needle provides a smooth passage through those highly selective and almost impermeable membranes. A single bacterium can have several hundred needle complexes spread across its membrane. It has been proposed that the needle complex is a universal feature of all T3SSs of pathogenic bacteria.

The needle complex starts at the cytoplasm of the bacterium, crosses the two membranes and protrudes from the cell. The part anchored in the membrane is the base (or basal body) of the T3SS. The extracellular part is the needle. A so-called inner rod connects the needle to the base. The needle itself, although the biggest and most prominent part of the T3SS, is made out of many units of a single protein. The majority of the different T3SS proteins are therefore those that build the base and those that are secreted into the host. As mentioned above, the needle complex shares similarities with bacterial flagella. More specifically, the base of the needle complex is structurally very similar to the flagellar base; the needle itself is analogous to the flagellar hook, a structure connecting the base to the flagellar filament.

The base is composed of several circular rings and is the first structure that is built in a new needle complex. Once the base is completed, it serves as a secretion machine for the outer proteins (the needle). Once the whole complex is completed the system switches to secreting proteins that are intended to be delivered into host cells. The needle is presumed to be built from bottom to top; units of needle monomer

In chemistry, a monomer ( ; ''mono-'', "one" + '' -mer'', "part") is a molecule that can react together with other monomer molecules to form a larger polymer chain or three-dimensional network in a process called polymerization.

Classification

...

protein pile upon each other, so that the unit at the tip of the needle is the last one added. The needle subunit is one of the smallest T3SS proteins, measuring at around 9 k Da. 100−150 subunits comprise each needle.

The T3SS needle measures around 60−80 nm in length and 8 nm in external width. It needs to have a minimal length so that other extracellular bacterial structures ( adhesins and the lipopolysaccharide

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are large molecules consisting of a lipid and a polysaccharide that are bacterial toxins. They are composed of an O-antigen, an outer core, and an inner core all joined by a covalent bond, and are found in the outer ...

layer, for instance) do not interfere with secretion. The hole of the needle has a 3 nm diameter. Most folded effector proteins are too large to pass through the needle opening, so most secreted proteins must pass through the needle unfolded, a task carried out by the ATPase

ATPases (, Adenosine 5'-TriPhosphatase, adenylpyrophosphatase, ATP monophosphatase, triphosphatase, SV40 T-antigen, ATP hydrolase, complex V (mitochondrial electron transport), (Ca2+ + Mg2+)-ATPase, HCO3−-ATPase, adenosine triphosphatase) are ...

at the base of the structure.

T3SS proteins

The T3SS proteins can be grouped into three categories:

* Structural proteins: build the base, the inner rod and the needle.

* Effector proteins: get secreted into the host cell and promote infection / suppress host cell defences.

* Chaperones: bind effectors in the bacterial cytoplasm, protect them from aggregation and degradation and direct them towards the needle complex.

Most T3SS genes are laid out in

The T3SS proteins can be grouped into three categories:

* Structural proteins: build the base, the inner rod and the needle.

* Effector proteins: get secreted into the host cell and promote infection / suppress host cell defences.

* Chaperones: bind effectors in the bacterial cytoplasm, protect them from aggregation and degradation and direct them towards the needle complex.

Most T3SS genes are laid out in operon

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo spli ...

s. These operons are located on the bacterial chromosome in some species and on a dedicated plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; howev ...

in other species. ''Salmonella'', for instance, has a chromosomal region in which most T3SS genes are gathered, the so-called ''Salmonella'' pathogenicity island (SPI). ''Shigella'', on the other hand, has a large virulence plasmid on which all T3SS genes reside. It is important to note that many pathogenicity islands and plasmids contain elements that allow for frequent horizontal gene transfer of the island/plasmid to a new species.

Effector proteins that are to be secreted through the needle need to be recognized by the system, since they float in the cytoplasm together with thousands of other proteins. Recognition is done through a secretion signal—a short sequence of amino acids located at the beginning (the N-terminus

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the ami ...

) of the protein (usually within the first 20 amino acids), that the needle complex is able to recognize. Unlike other secretion systems, the secretion signal of T3SS proteins is never cleaved off the protein.

Induction of secretion

Contact of the needle with a host cell triggers the T3SS to start secreting; not much is known about this trigger mechanism (see below). Secretion can also be induced by lowering the concentration ofcalcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar t ...

ions in the growth medium

A growth medium or culture medium is a solid, liquid, or semi-solid designed to support the growth of a population of microorganisms or cells via the process of cell proliferation or small plants like the moss '' Physcomitrella patens''. Differ ...

(for ''Yersinia'' and ''Pseudomonas''; done by adding a chelator such as EDTA

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) is an aminopolycarboxylic acid with the formula H2N(CH2CO2H)2sub>2. This white, water-soluble solid is widely used to bind to iron (Fe2+/Fe3+) and calcium ions (Ca2+), forming water-soluble complexes ev ...

or EGTA) and by adding the aromatic

In chemistry, aromaticity is a chemical property of cyclic (ring-shaped), ''typically'' planar (flat) molecular structures with pi bonds in resonance (those containing delocalized electrons) that gives increased stability compared to sat ...

dye Congo red to the growth medium (for ''Shigella''), for instance. These methods and other are used in laboratories to artificially induce type III secretion.

Induction of secretion by external cues other than contact with host cells also takes place ''in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, and ...

'', in infected organisms. The bacteria sense such cues as temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that expresses quantitatively the perceptions of hotness and coldness. Temperature is measured with a thermometer.

Thermometers are calibrated in various temperature scales that historically have relied on ...

, pH, osmolarity

Osmotic concentration, formerly known as osmolarity, is the measure of solute concentration, defined as the number of osmoles (Osm) of solute per litre (L) of solution (osmol/L or Osm/L). The osmolarity of a solution is usually expressed as Osm/ ...

and oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as we ...

levels, and use them to "decide" whether to activate their T3SS. For instance, ''Salmonella'' can replicate and invade better in the ileum

The ileum () is the final section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear and the terms posterior intestine or distal intestine m ...

rather than in the cecum of animal intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans a ...

. The bacteria are able to know where they are thanks to the different ions present in these regions; the ileum contains formate

Formate ( IUPAC name: methanoate) is the conjugate base of formic acid. Formate is an anion () or its derivatives such as ester of formic acid. The salts and esters are generally colorless.Werner Reutemann and Heinz Kieczka "Formic Acid" in ...

and acetate

An acetate is a salt formed by the combination of acetic acid with a base (e.g. alkaline, earthy, metallic, nonmetallic or radical base). "Acetate" also describes the conjugate base or ion (specifically, the negatively charged ion called ...

, while the cecum does not. The bacteria sense these molecules, determine that they are at the ileum and activate their secretion machinery. Molecules present in the cecum, such as propionate and butyrate

The conjugate acids are in :Carboxylic acids.

{{Commons category, Carboxylate ions, Carboxylate anions

Carbon compounds

Oxyanions ...

, provide a negative cue to the bacteria and inhibit secretion. Cholesterol

Cholesterol is any of a class of certain organic molecules called lipids. It is a sterol (or modified steroid), a type of lipid. Cholesterol is biosynthesized by all animal cells and is an essential structural component of animal cell membr ...

, a lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids incl ...

found in most eukaryotic cell membranes, is able to induce secretion in ''Shigella''.

The external cues listed above either regulate secretion directly or through a genetic mechanism. Several transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The fu ...

s that regulate the expression of T3SS genes are known. Some of the chaperones that bind T3SS effectors also act as transcription factors. A feedback mechanism has been suggested: when the bacterium does not secrete, its effector proteins are bound to chaperones and float in the cytoplasm. When secretion starts, the chaperones detach from the effectors and the latter are secreted and leave the cell. The lone chaperones then act as transcription factors, binding to the genes encoding their effectors and inducing their transcription and thereby the production of more effectors.

Structures similar to Type3SS injectisomes have been proposed to rivet gram negative bacterial outer and inner membranes to help release outer membrane vesicles targeted to deliver bacterial secretions to eukaryotic host or other target cells in vivo.

T3SS-mediated infection

T3SS effectors enter the needle complex at the base and make their way inside the needle towards the host cell. The exact way in which effectors enter the host is mostly unknown. It has been previously suggested that the needle itself is capable of puncturing a hole in the host cell membrane; this theory has been refuted. It is now clear that some effectors, collectively named translocators, are secreted first and produce a pore or a channel (a translocon) in the host cell membrane, through which other effectors may enter.Mutated

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mitos ...

bacteria that lack translocators are able to secrete proteins but are not able to deliver them into host cells. In general each T3SS includes three translocators. Some translocators serve a double role; after they participate in pore formation they enter the cell and act as ''bona fide'' effectors.

T3SS effectors manipulate host cells in several ways. The most striking effect is the promoting of uptake of the bacterium by the host cell. Many bacteria possessing T3SSs must enter host cells in order to replicate and propagate infection. The effectors they inject into the host cell induce the host to engulf the bacterium and to practically "eat" it. In order for this to happen the bacterial effectors manipulate the actin

Actin is a protein family, family of Globular protein, globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in myofibril, muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all Eukaryote, eukaryotic cel ...

polymerization

In polymer chemistry, polymerization (American English), or polymerisation (British English), is a process of reacting monomer molecules together in a chemical reaction to form polymer chains or three-dimensional networks. There are many fo ...

machinery of the host cell. Actin is a component of the cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is comp ...

and it also participates in motility and in changes in cell shape. Through its T3SS effectors the bacterium is able to utilize the host cell's own machinery for its own benefit. Once the bacterium has entered the cell it is able to secrete other effectors more easily and it can penetrate neighboring cells and quickly infect the whole tissue.

T3SS effectors have also been shown to tamper with the host's cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA ( DNA replication) and some of its organelles, and sub ...

and some of them are able to induce apoptosis. One of the most researched T3SS effector is IpaB from ''Shigella flexneri

''Shigella flexneri'' is a species of Gram-negative bacteria in the genus '' Shigella'' that can cause diarrhea in humans. Several different serogroups of ''Shigella'' are described; ''S. flexneri'' belongs to group ''B''. ''S. flexneri'' infe ...

''. It serves a double role, both as a translocator, creating a pore in the host cell membrane, and as an effector, exerting multiple detrimental effects on the host cell. It had been demonstrated that IpaB induces apoptosis in macrophages—cells of the animal immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as Tumor immunology, cancer cells and objects such ...

—after being engulfed by them. It was later shown that IpaB achieves this by interacting with caspase 1

Caspase-1/Interleukin-1 converting enzyme (ICE) is an evolutionarily conserved enzyme that proteolytically cleaves other proteins, such as the precursors of the inflammatory cytokines interleukin 1β and interleukin 18 as well as the pyroptos ...

, a major regulatory protein in eukaryotic cells.

Another well characterized class of T3SS effectors are Transcription Activator-like effectors ( TAL effectors) from Xanthomonas. When injected into plants, these proteins can enter the nucleus of the plant cell, bind plant promoter sequences, and activate transcription of plant genes that aid in bacterial infection. TAL effector-DNA recognition has recently been demonstrated to comprise a simple code and this has greatly improved the understanding of how these proteins can alter the transcription of genes in the host plant cells.

Unresolved issues

Hundreds of articles on T3SS have been published since the mid-nineties. However, numerous issues regarding the system remain unresolved:

* T3SS proteins. Of the approximately 30 T3SS proteins less than 10 in each organism have been directly detected using biochemical methods. The rest, being perhaps rare, have proven difficult to detect and they remain theoretical (although genetic rather than biochemical studies have been performed on many T3SS genes/proteins). The localization of each protein is also not entirely known.

* The length of the needle. It is not known how the bacterium "knows" when a new needle has reached its proper length. Several theories exist, among them the existence of a "ruler protein" that somehow connects the tip and the base of the needle. Addition of new monomers to the tip of the needle should stretch the ruler protein and thereby signal the needle length to the base.

* Energetics. The force that drives the passage of proteins inside the needle is not completely known. An

Hundreds of articles on T3SS have been published since the mid-nineties. However, numerous issues regarding the system remain unresolved:

* T3SS proteins. Of the approximately 30 T3SS proteins less than 10 in each organism have been directly detected using biochemical methods. The rest, being perhaps rare, have proven difficult to detect and they remain theoretical (although genetic rather than biochemical studies have been performed on many T3SS genes/proteins). The localization of each protein is also not entirely known.

* The length of the needle. It is not known how the bacterium "knows" when a new needle has reached its proper length. Several theories exist, among them the existence of a "ruler protein" that somehow connects the tip and the base of the needle. Addition of new monomers to the tip of the needle should stretch the ruler protein and thereby signal the needle length to the base.

* Energetics. The force that drives the passage of proteins inside the needle is not completely known. An ATPase

ATPases (, Adenosine 5'-TriPhosphatase, adenylpyrophosphatase, ATP monophosphatase, triphosphatase, SV40 T-antigen, ATP hydrolase, complex V (mitochondrial electron transport), (Ca2+ + Mg2+)-ATPase, HCO3−-ATPase, adenosine triphosphatase) are ...

is associated with the base of the T3SS and participates in directing proteins into the needle; but whether it supplies the energy for transport is not clear.

* Secretion signal. As mentioned above, the existence of a secretion signal in effector proteins is known. The signal allows the system to distinguish T3SS-transported proteins from any other protein. Its nature, requirements and the mechanism of recognition are poorly understood, but methods for predicting which bacterial proteins can be transported by the Type III secretion system have recently been developed.

* Activation of secretion. The bacterium must know when the time is right to secrete effectors. Unnecessary secretion, when no host cell is in vicinity, is wasteful for the bacterium in terms of energy and resources. The bacterium is somehow able to recognize contact of the needle with the host cell. How this is done is still being researched, and the method may well be dependent on the pathogen. Some theories postulate a delicate conformational change in the structure of the needle upon contact with the host cell; this change perhaps serves as a signal for the base to commence secretion. One method of recognition has been discovered in ''Salmonella'', which relies on sensing host cell cytosolic pH through the pathogenicity island 2-encoded T3SS in order to switch on secretion of effectors.

* Binding of chaperones. It is not known when chaperones bind their effectors (whether during or after translation

Translation is the communication of the Meaning (linguistic), meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The ...

) and how they dissociate from their effectors before secretion.

* Effector mechanisms. Although much was revealed since the beginning of the 21st century about the ways in which T3SS effectors manipulate the host, the majority of effects and pathways remains unknown.

* Evolution. As mentioned, the T3SS is closely related to the bacterial flagellum. There are three competing hypotheses: first, that the flagellum evolved first and the T3SS is derived from that structure, second, that the T3SS evolved first and the flagellum is derived from it, and third, that the two structures are derived from a common ancestor. There was some controversy about the different scenarios, since they all explain protein homology between the two structures, as well as their functional diversity. Yet, recent phylogenomic evidence favours the hypothesis that the T3SS derived from the flagellum by a process involving initial gene loss and then gene acquisition. A key step of the latter process was the recruitment of secretins to the T3SS, an event that occurred at least three times from other membrane-associated systems.

Nomenclature of T3SS proteins

Since the beginning of the 1990s new T3SS proteins are being found in different bacterial species at a steady rate. Abbreviations have been given independently for each series of proteins in each organism, and the names usually do not reveal much about the protein's function. Some proteins discovered independently in different bacteria have later been shown to behomologous

Homology may refer to:

Sciences

Biology

*Homology (biology), any characteristic of biological organisms that is derived from a common ancestor

*Sequence homology, biological homology between DNA, RNA, or protein sequences

* Homologous chrom ...

; the historical names, however, have mostly been kept, a fact that might cause confusion. For example, the proteins SicA, IpgC and SycD are homologs from ''Salmonella'', ''Shigella'' and ''Yersinia'', respectively, but the last letter (the "serial number") in their name does not show that.

Below is a summary of the most common protein-series names in several T3SS-containing species. Note that these names include proteins that form the T3SS machinery as well as the secreted effector proteins:

* ''Yersinia''

** Yop: ''Yersinia'' outer protein

** Ysc: ''Yersinia'' secretion (component)

** Ypk: ''Yersinia'' protein kinase

* ''Salmonella''

** Spa: Surface presentation of antigen

** Sic: ''Salmonella'' invasion chaperone

** Sip: ''Salmonella'' invasion protein

** Prg: PhoP-repressed gene

** Inv: Invasion

** Org: Oxygen-regulated gene

** Ssp: ''Salmonella''-secreted protein

** Iag: Invasion-associated gene

* ''Shigella''

** Ipg: Invasion plasmid gene

** Ipa: Invasion plasmid antigen

** Mxi: Membrane expression of Ipa

** Spa: Surface presentation of antigen

** Osp: Outer ''Shigella'' protein

* ''Escherichia''

** Tir: Translocated intimin receptor

** Sep: Secretion of ''E. coli'' proteins

** Esc: ''Escherichia'' secretion (component)

** Esp: ''Escherichia'' secretion protein

** Ces: Chaperone of ''E. coli'' secretion

* ''Pseudomonas''

** Hrp: Hypersensitive response and pathogenicity

** Hrc: Hypersensitive response conserved (or Hrp conserved)

* ''Rhizobium''

** Nop: Nodulation protein

** Rhc: ''Rhizobium'' conserved

* In several species:

** Vir: Virulence

* "Protochlamydia amoebophila"

* "Sodalis glossinidius"

Following those abbreviations is a letter or a number. Letters usually denote a "serial number", either the chronological order of discovery or the physical order of appearance of the gene in an operon

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo spli ...

. Numbers, the rarer case, denote the molecular weight of the protein in kDa. Examples: IpaA, IpaB, IpaC; MxiH, MxiG, MxiM; Spa9, Spa47.

Several key elements appear in all T3SSs: the needle monomer, the inner rod of the needle, the ring proteins, the two translocators, the needle-tip protein, the ruler protein (which is thought to determine the needle's length; see above) and the ATPase

ATPases (, Adenosine 5'-TriPhosphatase, adenylpyrophosphatase, ATP monophosphatase, triphosphatase, SV40 T-antigen, ATP hydrolase, complex V (mitochondrial electron transport), (Ca2+ + Mg2+)-ATPase, HCO3−-ATPase, adenosine triphosphatase) are ...

, which supplies energy for secretion. The following table shows some of these key proteins in four T3SS-containing bacteria:

Methods employed in T3SS research

Isolation of T3SS needle complexes

The isolation of large, fragile,hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the physical property of a molecule that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water (known as a hydrophobe). In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, ...

membrane structures from cells has constituted a challenge for many years. By the end of the 1990s, however, several approaches have been developed for the isolation of T3SS NCs. In 1998 the first NCs were isolated from ''Salmonella typhimurium

''Salmonella enterica'' subsp. ''enterica'' is a subspecies of ''Salmonella enterica'', the rod-shaped, flagellated, aerobic, Gram-negative bacterium. Many of the pathogenic serovars of the ''S. enterica'' species are in this subspecies, includ ...

''.

For the isolation, bacteria are grown in a large volume of liquid growth medium

A growth medium or culture medium is a solid, liquid, or semi-solid designed to support the growth of a population of microorganisms or cells via the process of cell proliferation or small plants like the moss '' Physcomitrella patens''. Differ ...

until they reach log phase. They are then centrifuge

A centrifuge is a device that uses centrifugal force to separate various components of a fluid. This is achieved by spinning the fluid at high speed within a container, thereby separating fluids of different densities (e.g. cream from milk) or ...

d; the supernatant (the medium) is discarded and the pellet (the bacteria) is resuspended in a lysis buffer typically containing lysozyme

Lysozyme (EC 3.2.1.17, muramidase, ''N''-acetylmuramide glycanhydrolase; systematic name peptidoglycan ''N''-acetylmuramoylhydrolase) is an antimicrobial enzyme produced by animals that forms part of the innate immune system. It is a glycosid ...

and sometimes a detergent

A detergent is a surfactant or a mixture of surfactants with cleansing properties when in dilute solutions. There are a large variety of detergents, a common family being the alkylbenzene sulfonates, which are soap-like compounds that are m ...

such as LDAO or Triton X-100. This buffer disintegrates the cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mec ...

. After several rounds of lysis and washing, the opened bacteria are subjected to a series of ultracentrifugations. This treatment enriches large macromolecular structures and discards smaller cell components. Optionally, the final lysate is subjected to further purification by CsCl density gradient.

An additional approach for further purification uses affinity chromatography. Recombinant T3SS proteins that carry a protein tag (a histidine tag

A polyhistidine-tag is an amino acid motif in proteins that typically consists of at least six histidine (''His'') residues, often at the N- or C-terminus of the protein. It is also known as hexa histidine-tag, 6xHis-tag, His6 tag, by the US trad ...

, for instance) are produced by molecular cloning

Molecular cloning is a set of experimental methods in molecular biology that are used to assemble recombinant DNA molecules and to direct their replication within host organisms. The use of the word '' cloning'' refers to the fact that the meth ...

and then introduced ( transformed) into the researched bacteria. After initial NC isolation, as described above, the lysate is passed through a column coated with particles with high affinity to the tag (in the case of histidine tags: nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

ions). The tagged protein is retained in the column, and with it the entire needle complex. High degrees of purity can be achieved using such methods. This purity is essential for many delicate assays that have been used for NC characterization.

Type III effectors were known since the beginning of the 1990s, but the way in which they are delivered into host cells was a complete mystery. The homology between many flagellar

A flagellum (; ) is a hairlike appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many protists with flagella are termed as flagellates.

A microorganism may have fro ...

and T3SS proteins led researchers to suspects the existence of an outer T3SS structure similar to flagella. The identification and subsequent isolation of the needle structure enabled researchers to:

* characterize the three-dimensional structure of the NC in detail, and through this to draw conclusions regarding the mechanism of secretion (for example, that the narrow width of the needle requires unfolding of effectors prior to secretion),

* analyze the protein components of the NC, this by subjecting isolated needles to proteomic analysis (see below),

* assign roles to various NC components, this by knocking out T3SS genes, isolating NCs from the mutated bacteria and examining the changes that the mutations caused.

Microscopy, crystallography and solid-state NMR

As with almost all proteins, the visualization of T3SS NCs is only possible withelectron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a ...

. The first images of NCs (1998) showed needle structures protruding from the cell wall of live bacteria and flat, two-dimensional isolated NCs. In 2001 images of NCs from ''Shigella flexneri

''Shigella flexneri'' is a species of Gram-negative bacteria in the genus '' Shigella'' that can cause diarrhea in humans. Several different serogroups of ''Shigella'' are described; ''S. flexneri'' belongs to group ''B''. ''S. flexneri'' infe ...

'' were digitally analyzed and averaged to obtain a first semi-3D structure of the NC. The helical structure of NCs from ''Shigella flexneri'' was resolved at a resolution of 16 Å using X-ray

X-rays (or rarely, ''X-radiation'') are a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. In many languages, it is referred to as Röntgen radiation, after the German scientist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, who discovered it in 1895 and named it ' ...

fiber diffraction in 2003, and a year later a 17- Å 3D structure of NCs from ''Salmonella typhimurium'' was published. Recent advances and approaches have allowed high-resolution 3D images of the NC, further clarifying the complex structure of the NC.

Numerous T3SS proteins have been crystallized over the years. These include structural proteins of the NC, effectors and chaperones. The first structure of a needle-complex monomer was NMR structure of BsaL from "Burkholderia pseudomallei" and later the crystal structure of MixH from ''Shigella flexneri'', which were both resolved in 2006.

In 2012, a combination of recombinant wild-type needle production, solid-state NMR

Solid-state NMR (ssNMR) spectroscopy is a technique for characterizing atomic level structure in solid materials e.g. powders, single crystals and amorphous samples and tissues using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The anisotropic pa ...

, electron microscopy and Rosetta modeling revealed the supramolecular interfaces and ultimately the complete atomic structure of the ''Salmonella typhimurium

''Salmonella enterica'' subsp. ''enterica'' is a subspecies of ''Salmonella enterica'', the rod-shaped, flagellated, aerobic, Gram-negative bacterium. Many of the pathogenic serovars of the ''S. enterica'' species are in this subspecies, includ ...

'' T3SS needle. It was shown that the 80-residue PrgI subunits form a right-handed helical assembly with roughly 11 subunits per two turns, similar to that of the flagellum

A flagellum (; ) is a hairlike appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many protists with flagella are termed as flagellates.

A microorganism may have f ...

of ''Salmonella typhimurium

''Salmonella enterica'' subsp. ''enterica'' is a subspecies of ''Salmonella enterica'', the rod-shaped, flagellated, aerobic, Gram-negative bacterium. Many of the pathogenic serovars of the ''S. enterica'' species are in this subspecies, includ ...

''. The model also revealed an extended amino-terminal domain that is positioned on the surface of the needle, while the highly conserved carboxy terminus points towards the lumen.

Proteomics

Several methods have been employed in order to identify the array of proteins that comprise the T3SS. Isolated needle complexes can be separated withSDS-PAGE

SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) is a discontinuous electrophoretic system developed by Ulrich K. Laemmli which is commonly used as a method to separate proteins with molecular masses between 5 and 250 kDa. ...

. The bands that appear after staining can be individually excised from the gel and analyzed using protein sequencing and mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a '' mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is u ...

. The structural components of the NC can be separated from each other (the needle part from the base part, for instance), and by analyzing those fractions the proteins participating in each one can be deduced. Alternatively, isolated NCs can be directly analyzed by mass spectrometry, without prior electrophoresis

Electrophoresis, from Ancient Greek ἤλεκτρον (ḗlektron, "amber") and φόρησις (phórēsis, "the act of bearing"), is the motion of dispersed particles relative to a fluid under the influence of a spatially uniform electric f ...

, in order to obtain a complete picture of the NC proteome

The proteome is the entire set of proteins that is, or can be, expressed by a genome, cell, tissue, or organism at a certain time. It is the set of expressed proteins in a given type of cell or organism, at a given time, under defined conditions. ...

.

Genetic and functional studies

The T3SS in many bacteria has been manipulated by researchers. Observing the influence of individual manipulations can be used to draw insights into the role of each component of the system. Examples of manipulations are: * Deletion of one or more T3SS genes (gene knockout

A gene knockout (abbreviation: KO) is a genetic technique in which one of an organism's genes is made inoperative ("knocked out" of the organism). However, KO can also refer to the gene that is knocked out or the organism that carries the gene kno ...

).

* Overexpression of one or more T3SS genes (in other words: production ''in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, and ...

'' of a T3SS protein in quantities larger than usual).

* Point or regional changes in T3SS genes or proteins. This is done in order to define the function of specific amino acids or regions in a protein.

* The introduction of a gene or a protein from one species of bacteria into another (cross-complementation assay). This is done in order to check for differences and similarities between two T3SSs.

Manipulation of T3SS components can have influence on several aspects of bacterial function and pathogenicity. Examples of possible influences:

* The ability of the bacteria to invade host cells, in the case of intracellular pathogens. This can be measured using an invasion assay The gentamicin protection assay or survival assay or invasion assay is a method used in microbiology. It is used to quantify the ability of pathogenic bacteria to invade eukaryotic cells.

The assay is based on several observations made in the 19 ...

( gentamicin protection assay).

* The ability of intracellular bacteria to migrate between host cells.

* The ability of the bacteria to kill host cells. This can be measured by several methods, for instance by the LDH-release assay, in which the enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecule ...

LDH, which leaks from dead cells, is identified by measuring its enzymatic activity.

* The ability of a T3SS to secrete a specific protein or to secrete at all. In order to assay this, secretion is induced in bacteria growing in liquid medium. The bacteria and medium are then separated by centrifugation, and the medium fraction (the supernatant) is then assayed for the presence of secreted proteins. In order to prevent a normally secreted protein from being secreted, a large molecule can be artificially attached to it. If the then non-secreted protein stays "stuck" at the bottom of the needle complex, the secretion is effectively blocked.

* The ability of the bacteria to assemble an intact needle complex. NCs can be isolated from manipulated bacteria and examined microscopically. Minor changes, however cannot always be detected by microscopy.

* The ability of bacteria to infect live animals or plants. Even if manipulated bacteria are shown ''in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning in glass, or ''in the glass'') studies are performed with microorganisms, cells, or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in biology and ...

'' to be able to infect host cells, their ability to sustain an infection in a live organism cannot be taken for granted.

* The expression levels of other genes. This can be assayed in several ways, notably northern blot

The northern blot, or RNA blot,Gilbert, S. F. (2000) Developmental Biology, 6th Ed. Sunderland MA, Sinauer Associates. is a technique used in molecular biology research to study gene expression by detection of RNA (or isolated mRNA) in a sample.Ke ...

and RT-PCR

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is a laboratory technique combining reverse transcription of RNA into DNA (in this context called complementary DNA or cDNA) and amplification of specific DNA targets using polymerase chai ...

. The expression levels of the entire genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ...

can be assayed by microarray

A microarray is a multiplex lab-on-a-chip. Its purpose is to simultaneously detect the expression of thousands of genes from a sample (e.g. from a tissue). It is a two-dimensional array on a solid substrate—usually a glass slide or silic ...

. Many type III transcription factors

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The f ...

and regulatory networks were discovered using these methods.

* The growth and fitness of bacteria.

Inhibitors of the T3SS

A few compounds have been discovered that inhibit the T3SS ingram-negative bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wa ...

, including the guadinomines which are naturally produced by ''Streptomyces

''Streptomyces'' is the largest genus of Actinomycetota and the type genus of the family Streptomycetaceae. Over 500 species of ''Streptomyces'' bacteria have been described. As with the other Actinomycetota, streptomycetes are gram-positive, ...

'' species. Monoclonal antibodies

A monoclonal antibody (mAb, more rarely called moAb) is an antibody produced from a cell Lineage made by cloning a unique white blood cell. All subsequent antibodies derived this way trace back to a unique parent cell.

Monoclonal antibodies ...

have been developed that inhibit the T3SS too. Aurodox, an antibiotic capable of inhibiting the translation of T3SS proteins has been shown to able to prevent T3SS effectors in vitro and in animal models

Type III signal peptide prediction tools

EffectiveT3

References

Further reading

Instant insight

outlining the chemistry of the injectisome from the

Royal Society of Chemistry

The Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) is a learned society (professional association) in the United Kingdom with the goal of "advancing the chemistry, chemical sciences". It was formed in 1980 from the amalgamation of the Chemical Society, the Ro ...

Host-Pathogen Interaction

in ''Pseudomonas syringae'' pv. ''tomato'' and tomato plant leading to bacterial speck disease. {{DEFAULTSORT:Type Three Secretion System Organelles Secretion