Titanic victim on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A total of 2,208 people sailed on the maiden voyage of the RMS ''Titanic'', the second of the

A total of 2,208 people sailed on the maiden voyage of the RMS ''Titanic'', the second of the

The ''Titanic'' first-class list was a "

The ''Titanic'' first-class list was a "

First-class passengers enjoyed a number of amenities, including a gymnasium, a squash court, a saltwater swimming pool, electric and

''BBC Southampton'', August 2002. First-class passengers also traveled accompanied by personal staff—valets, maids, nurses and Many members of the British aristocracy made the trip: The Countess of Rothes, wife of the 19th Earl of Rothes, embarked at Southampton with her parents, Thomas and Clementina Dyer-Edwardes, and cousin

Many members of the British aristocracy made the trip: The Countess of Rothes, wife of the 19th Earl of Rothes, embarked at Southampton with her parents, Thomas and Clementina Dyer-Edwardes, and cousin

Second-class passengers were leisure tourists, academics, members of the clergy, and middle-class English, Scottish and American families. The ship's musicians travelled in second-class accommodations; they were not counted as members of the crew, but were employed by an agency under contract to the White Star Line. The average ticket price for an adult second-class passenger was £13, the equivalent of £ today. and for many of these passengers, their travel experience on the ''Titanic'' was akin to travelling first class on smaller liners. Second-class passengers had their own library and the men had access to a private smoking room. Second-class children could read the children's books provided in the library or play deck

Second-class passengers were leisure tourists, academics, members of the clergy, and middle-class English, Scottish and American families. The ship's musicians travelled in second-class accommodations; they were not counted as members of the crew, but were employed by an agency under contract to the White Star Line. The average ticket price for an adult second-class passenger was £13, the equivalent of £ today. and for many of these passengers, their travel experience on the ''Titanic'' was akin to travelling first class on smaller liners. Second-class passengers had their own library and the men had access to a private smoking room. Second-class children could read the children's books provided in the library or play deck  Two Roman Catholic priests on board, Father Thomas Byles and Father Joseph Peruschitz, celebrated

Two Roman Catholic priests on board, Father Thomas Byles and Father Joseph Peruschitz, celebrated

The third-class passengers or steerage passengers left hoping to start new lives in the United States and Canada. Third-class passengers paid £7 (£ today) for their ticket, depending on their place of origin; ticket prices often included the price of rail travel to the three departure ports. Tickets for children cost £3 (£ today).

Third-class passengers were a diverse group of nationalities and ethnic groups. In addition to large numbers of British, Irish, and Scandinavian immigrants, other passengers were from Central and Eastern Europe, the

The third-class passengers or steerage passengers left hoping to start new lives in the United States and Canada. Third-class passengers paid £7 (£ today) for their ticket, depending on their place of origin; ticket prices often included the price of rail travel to the three departure ports. Tickets for children cost £3 (£ today).

Third-class passengers were a diverse group of nationalities and ethnic groups. In addition to large numbers of British, Irish, and Scandinavian immigrants, other passengers were from Central and Eastern Europe, the

Among the larger third-class families were John and Annie Sage, who were immigrating to Jacksonville, Florida, with their 9 children, ranging in age from 4 to 20 years; Anders and Alfrida Andersson of Sweden and their five children, who were travelling to Canada along with Alfrida's younger sister Anna, husband Ernst, and baby Gilbert; and Frederick and Augusta Goodwin, who were moving with their six children to his new job at a power plant in New York. In 2007, scientists using DNA analysis identified the body of a small, fair-haired toddler, one of the first victims to be recovered by the CS ''

Among the larger third-class families were John and Annie Sage, who were immigrating to Jacksonville, Florida, with their 9 children, ranging in age from 4 to 20 years; Anders and Alfrida Andersson of Sweden and their five children, who were travelling to Canada along with Alfrida's younger sister Anna, husband Ernst, and baby Gilbert; and Frederick and Augusta Goodwin, who were moving with their six children to his new job at a power plant in New York. In 2007, scientists using DNA analysis identified the body of a small, fair-haired toddler, one of the first victims to be recovered by the CS ''

To compete with rival shipping company

To compete with rival shipping company

The untold story of Arabs

." ''

Why you've never heard of the six Chinese men who survived the Titanic

." ''

The first lifeboat launched was Lifeboat 7 on the

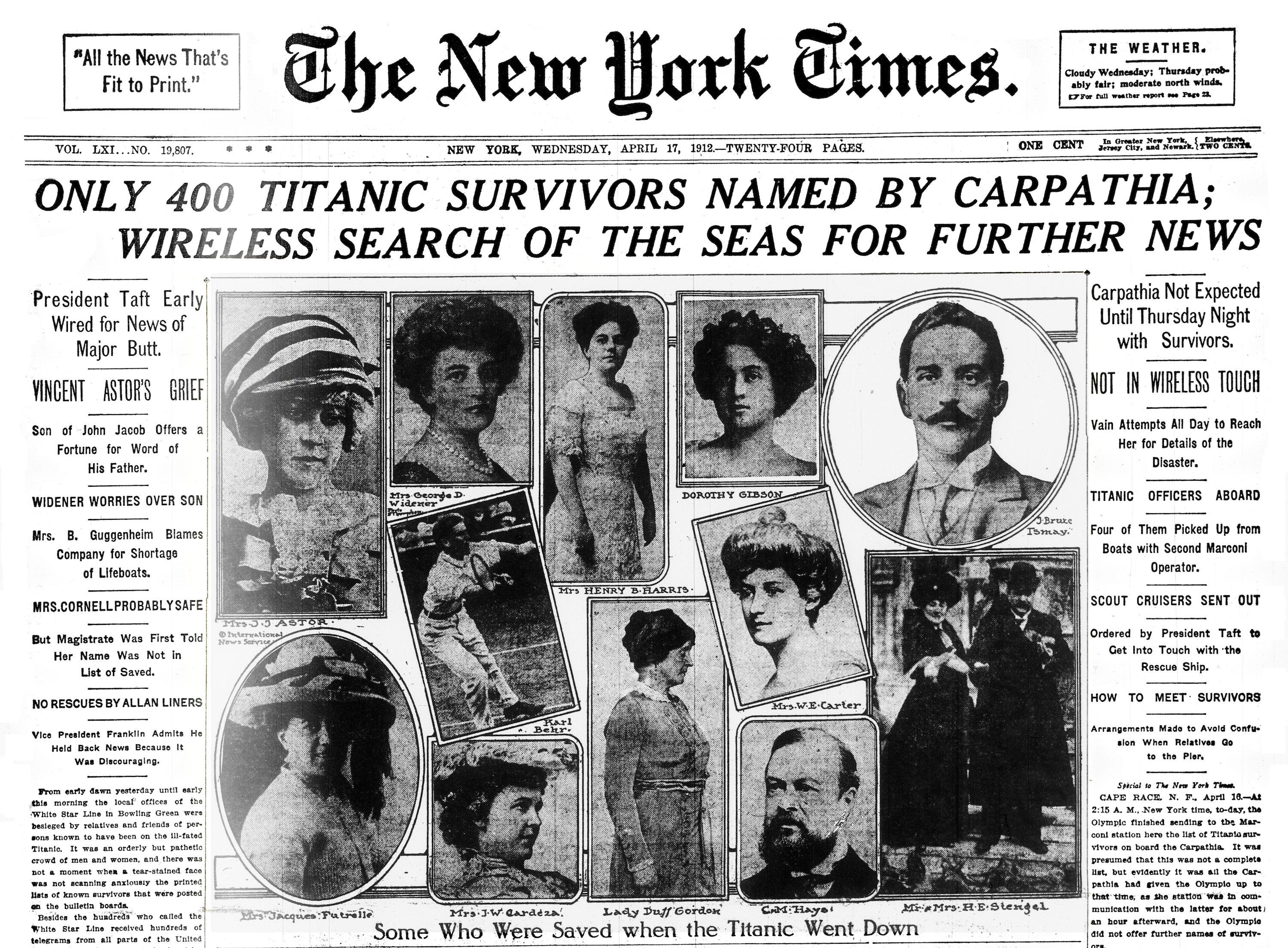

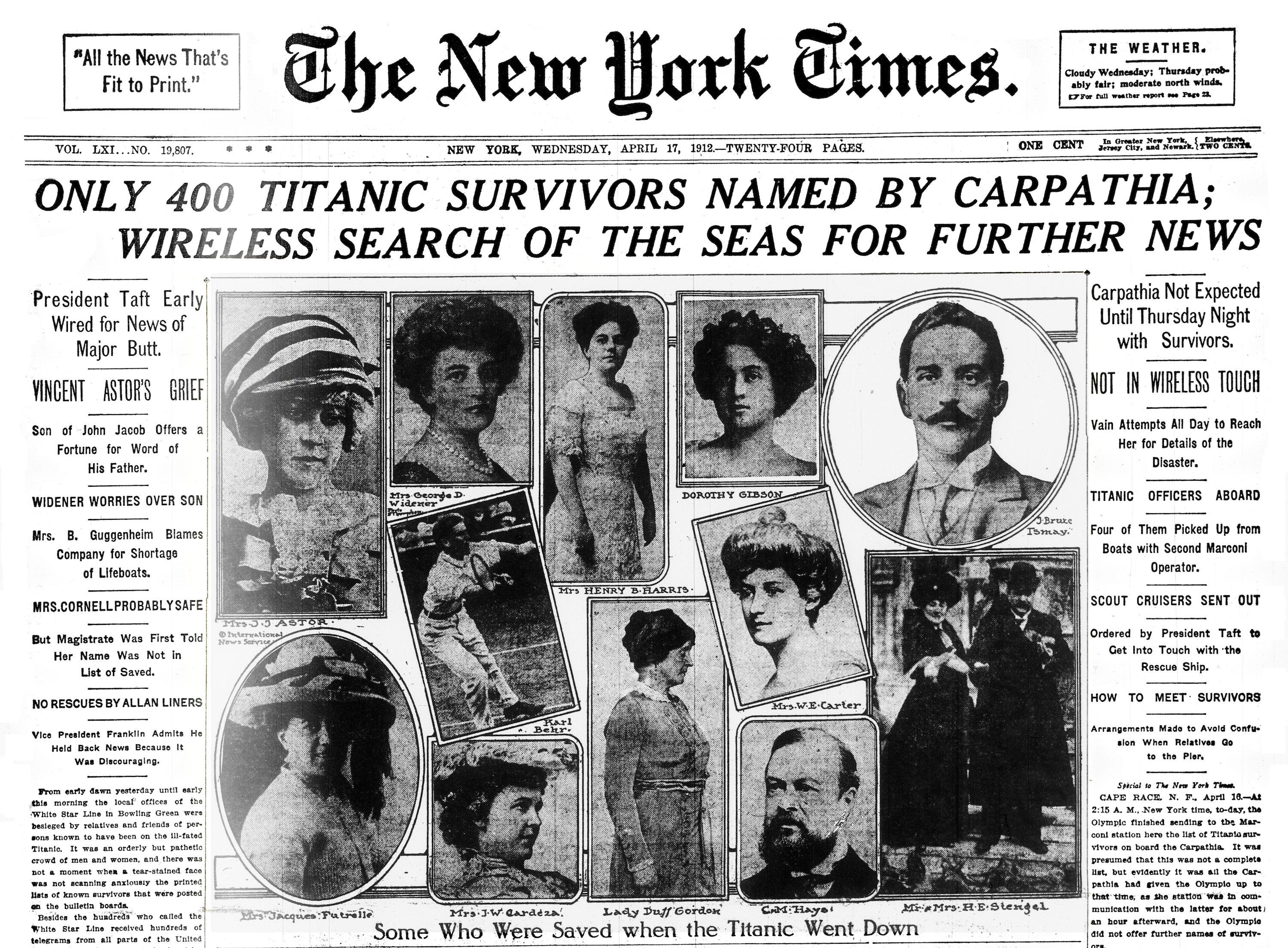

The first lifeboat launched was Lifeboat 7 on the  At 4:10 am, ''Carpathia'' arrived at the site of the sinking and began rescuing survivors. By 8:30 am, she picked up the last lifeboat with survivors and left the area at 08:50 bound for

At 4:10 am, ''Carpathia'' arrived at the site of the sinking and began rescuing survivors. By 8:30 am, she picked up the last lifeboat with survivors and left the area at 08:50 bound for  The ship found so many bodies – 306 – that the embalming supplies aboard were quickly exhausted. Health regulations permitted that only embalmed bodies could be returned to port. Captain Larnder of the ''Mackay-Bennett'' and the undertakers aboard decided to preserve all bodies of first-class passengers because of the need to visually identify wealthy men to resolve any disputes over large estates. As a result, the majority of the 116 burials at sea were third-class passengers and crew (only 56 were identified). Larnder himself claimed that as a mariner, he would expect to be buried at sea. However, complaints about the burials at sea were made by families and undertakers. Later ships such as ''Minia'' found fewer bodies, requiring fewer embalming supplies, and were able to limit burials at sea to bodies that were too damaged to preserve.

190 bodies recovered were preserved and taken to

The ship found so many bodies – 306 – that the embalming supplies aboard were quickly exhausted. Health regulations permitted that only embalmed bodies could be returned to port. Captain Larnder of the ''Mackay-Bennett'' and the undertakers aboard decided to preserve all bodies of first-class passengers because of the need to visually identify wealthy men to resolve any disputes over large estates. As a result, the majority of the 116 burials at sea were third-class passengers and crew (only 56 were identified). Larnder himself claimed that as a mariner, he would expect to be buried at sea. However, complaints about the burials at sea were made by families and undertakers. Later ships such as ''Minia'' found fewer bodies, requiring fewer embalming supplies, and were able to limit burials at sea to bodies that were too damaged to preserve.

190 bodies recovered were preserved and taken to

The passenger did not survive

The passenger survived

Survivors are listed with the lifeboat from which they were known to be rescued. Victims whose remains were recovered after the sinking are listed with a superscript next to the body number, indicating the recovery vessel: *MB – CS ''Mackay-Bennett'' (bodies 1–306) *M – CS ''Minia'' (bodies 307–323) *MM – CGS ''Montmagny'' (bodies 326–329) *A – SS ''Algerine'' (body 330) *O – RMS ''Oceanic'' (bodies 331–333) *I – SS ''Ilford'' (body 334) *OT – SS ''Ottawa'' (body 335) Numbers 324 and 325 were unused, and the six bodies buried at sea by the ''Carpathia'' also went unnumbered.

A total of 2,208 people sailed on the maiden voyage of the RMS ''Titanic'', the second of the

A total of 2,208 people sailed on the maiden voyage of the RMS ''Titanic'', the second of the White Star Line

The White Star Line was a British shipping company. Founded out of the remains of a defunct packet company, it gradually rose up to become one of the most prominent shipping lines in the world, providing passenger and cargo services between t ...

's ''Olympic''-class ocean liners, from Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

, England, to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Partway through the voyage, the ship struck an iceberg and sank in the early morning of 15 April 1912, resulting in the deaths of 1,503 people.

The ship's passengers were divided into three separate classes determined by the price of their ticket: those travelling in first class, most of them the wealthiest passengers on board, included prominent members of the upper class, businessmen, politicians, high-ranking military personnel, industrialists, bankers, entertainers, socialites, and professional athletes. Second-class passengers were predominantly middle-class travellers and included professors, authors, clergymen, and tourists. Third-class or steerage passengers were primarily immigrants moving to the United States and Canada.

Passengers

''Titanic''s passengers numbered 1,316 people. The ship was considerably under capacity on her maiden voyage, as she could accommodate 2,453 passengers—833 first class, 614 second class, and 1,006 third class.First class

The ''Titanic'' first-class list was a "

The ''Titanic'' first-class list was a "who's who

''Who's Who'' (or ''Who is Who'') is the title of a number of reference publications, generally containing concise biography, biographical information on the prominent people of a country. The title has been adopted as an expression meaning a gr ...

" of the prominent upper class in 1912. A single-person berth in first class cost between £30 () and £870 () for a parlour suite and small private promenade deck

The promenade deck is a deck found on several types of passenger ships and riverboats. It usually extends from bow to stern, on both sides, and includes areas open to the outside, resulting in a continuous outside walkway suitable for ''promena ...

.Metelko, Berit Hjellum, ''Web Titanic – Titanic's Maiden Voyage'', 2001First-class passengers enjoyed a number of amenities, including a gymnasium, a squash court, a saltwater swimming pool, electric and

Turkish bath

A hammam ( ar, حمّام, translit=ḥammām, tr, hamam) or Turkish bath is a type of steam bath or a place of public bathing associated with the Islamic world. It is a prominent feature in the culture of the Muslim world and was inherited ...

s, a barbershop, kennels for first-class dogs, elevators, and both open and enclosed promenades.Life on Board''BBC Southampton'', August 2002. First-class passengers also traveled accompanied by personal staff—valets, maids, nurses and

governess

A governess is a largely obsolete term for a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching. In contrast to a nanny, th ...

es for the children, chauffeurs, and cooks.

Many members of the British aristocracy made the trip: The Countess of Rothes, wife of the 19th Earl of Rothes, embarked at Southampton with her parents, Thomas and Clementina Dyer-Edwardes, and cousin

Many members of the British aristocracy made the trip: The Countess of Rothes, wife of the 19th Earl of Rothes, embarked at Southampton with her parents, Thomas and Clementina Dyer-Edwardes, and cousin Gladys Cherry

Gladys may refer to:

* Gladys (given name), people with the given name Gladys

* ''Gladys'' (album), a 2013 album by Leslie Clio

* ''Gladys'' (film), 1999 film written and directed by Vojtěch Jasný

* Gladys, Virginia, United States

* '' Glad ...

. Colonel Archibald Gracie IV

Archibald Gracie IV (January 15, 1858 – December 4, 1912) was an American writer, soldier, amateur historian, real estate investor, and survivor of the sinking of RMS ''Titanic''. Gracie survived the sinking by climbing aboard an overturned ...

, a real estate investor and member of the wealthy Scottish-American Gracie family, embarked at Southampton. The Cavendishes of London were among other prominent British couples on board, as well. Lord Pirrie, chairman of Harland and Wolff, intended to travel aboard the ''Titanic'', but illness prevented him from joining the ill-fated voyage; however, White Star Line's managing director J. Bruce Ismay

Joseph Bruce Ismay (; 12 December 1862 – 17 October 1937) was an English businessman who served as chairman and managing director of the White Star Line. In 1912, he came to international attention as the highest-ranking White Star official t ...

and the ship's Harland and Wolff designer, Thomas Andrews, were both on board to oversee the ship's progress on her maiden voyage.

Some of the most prominent members of the American social elite made the trip: real estate builder, businessman, and multimillionaire Colonel John Jacob Astor IV and his 18-year-old pregnant wife Madeleine were returning to the United States for their child's birth. Astor was the wealthiest passenger aboard the ship and one of the richest men in the world; his great-grandfather John Jacob Astor

John Jacob Astor (born Johann Jakob Astor; July 17, 1763 – March 29, 1848) was a German-American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor who made his fortune mainly in a fur trade monopoly, by smuggling opium into China, and ...

was the first multi-millionaire in America. Among others were industrialist magnate and millionaire Benjamin Guggenheim

Benjamin Guggenheim (October 26, 1865 – April 15, 1912) was an American businessman. He died aboard when the ship sank in the North Atlantic Ocean. His body was never recovered.

Early life

Guggenheim was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, t ...

; Macy's

Macy's (originally R. H. Macy & Co.) is an American chain of high-end department stores founded in 1858 by Rowland Hussey Macy. It became a division of the Cincinnati-based Federated Department Stores in 1994, through which it is affiliated wi ...

department store owner, and former member of the United States House of Representatives Isidor Straus

Isidor Straus (February 6, 1845 – April 15, 1912) was a Bavarian-born American Jewish businessman, politician and co-owner of Macy's department store with his brother Nathan. He also served for just over a year as a member of the United State ...

, and his wife Ida

Ida or IDA may refer to:

Astronomy

* Ida Facula, a mountain on Amalthea, a moon of Jupiter

*243 Ida, an asteroid

*International Docking Adapter, a docking adapter for the International Space Station

Computing

*Intel Dynamic Acceleration, a techn ...

; George Dennick Wick

Colonel George Dennick Wick (February 19, 1854 – April 15, 1912) was an American industrialist who served as founding president of the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company, one of the nation's largest regional steel-manufacturing firms.

He perish ...

, founder and president of Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company

The Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company, based in Youngstown, Ohio, was an American steel manufacturer. Officially, the company was created on November 23, 1900, when Articles of Incorporation of the Youngstown Iron Sheet and Tube Company were fil ...

; millionaire streetcar magnate George Dunton Widener

George Dunton Widener (June 16, 1861 – April 15, 1912) was an American businessman who died in the sinking of the RMS ''Titanic''.

Early life

Widener was born in Philadelphia on June 16, 1861. He was the eldest son of Hannah Josephine Du ...

; John B. Thayer

John Borland Thayer II (April 21, 1862April 15, 1912) was an American businessman who had a thirty-year career as an executive with the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. He was a director and second vice-president of the company when he died less t ...

, vice president of Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR), legal name The Pennsylvania Railroad Company also known as the "Pennsy", was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named ...

, and his wife, Marian; Charles Hays, president of Canada's Grand Trunk Railway; William Ernest Carter and his wife, American socialite Lucile Carter

Lucile Stewart Carter Brooke (née Polk; October 8, 1875 – October 26, 1934) was an American socialite and the wife of William E. Carter, William Ernest Carter, an extremely wealthy American who inherited a fortune from his father. The couple an ...

; millionaire, philanthropist and women's rights activist Margaret Brown; tennis star and banker Karl Behr; famous American silent film actress Dorothy Gibson

Dorothy Gibson (born Dorothy Winifred Brown; May 17, 1889 – February 17, 1946) was a pioneering American silent film actress, artist's model, and singer active in the early 20th century. She is best remembered as a survivor of the sinking o ...

; prominent Buffalo architect Edward Austin Kent

Edward Austin Kent (February 19, 1854 – April 15, 1912) was a prominent architect in Buffalo, New York. He died in the sinking of the RMS ''Titanic'' and was seen helping women and children into the lifeboats.

Biography

Edward Austin Kent wa ...

; and President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

's military aide, Major Archibald Butt

Archibald Willingham DeGraffenreid Clarendon Butt (September 26, 1865 – April 15, 1912) was an American Army officer and aide to presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. After a few years as a newspaper reporter, he served t ...

, who was returning to resume his duties after a six-week trip to Europe. Swedish first class passenger and businessman Mauritz Håkan Björnström-Steffansson

Mauritz Håkan Björnström-Steffansson () (also referred to as Hokan B. Steffanson), (9 November 1883 – 21 May 1962) was a Swedish businessman who survived the sinking of the RMS ''Titanic'' in 1912. In early 1913, Steffansson filed by far ...

owned the most highly valued single object on board: a masterpiece of French neoclassical painting entitled ''La Circassienne au Bain

''La Circassienne au Bain'', also known as ''Une Baigneuse'', was a large Neoclassicism, Neoclassical oil painting from 1814 by Merry-Joseph Blondel depicting a life-sized young Circassian beauties, Circassian woman bathing in an idealized sett ...

'', for which he would later claim US$100,000 in compensation (equivalent to US$ million in ).

Milton S. Hershey

Milton Snavely Hershey (September 13, 1857 – October 13, 1945) was an American chocolatier, businessman, and philanthropist.

Trained in the confectionery business, Hershey pioneered the manufacture of caramel, using fresh milk. He launched t ...

, founder of Hershey's chocolate, made plans to sail aboard the ship's maiden voyage, but cancelled his booking before the ship set sail. J. P. Morgan is also rumored to have been planning to make the voyage and changed plans last-minute, but there is no substantiation of his ever having been booked.

Second class

Second-class passengers were leisure tourists, academics, members of the clergy, and middle-class English, Scottish and American families. The ship's musicians travelled in second-class accommodations; they were not counted as members of the crew, but were employed by an agency under contract to the White Star Line. The average ticket price for an adult second-class passenger was £13, the equivalent of £ today. and for many of these passengers, their travel experience on the ''Titanic'' was akin to travelling first class on smaller liners. Second-class passengers had their own library and the men had access to a private smoking room. Second-class children could read the children's books provided in the library or play deck

Second-class passengers were leisure tourists, academics, members of the clergy, and middle-class English, Scottish and American families. The ship's musicians travelled in second-class accommodations; they were not counted as members of the crew, but were employed by an agency under contract to the White Star Line. The average ticket price for an adult second-class passenger was £13, the equivalent of £ today. and for many of these passengers, their travel experience on the ''Titanic'' was akin to travelling first class on smaller liners. Second-class passengers had their own library and the men had access to a private smoking room. Second-class children could read the children's books provided in the library or play deck quoits

Quoits ( or ) is a traditional game which involves the throwing of metal, rope or rubber rings over a set distance, usually to land over or near a spike (sometimes called a hob, mott or pin). The game of quoits encompasses several distinct vari ...

and shuffleboard on the second-class promenade. Twelve-year-old Ruth Becker

Ruth (or its variants) may refer to:

Places

France

* Château de Ruthie, castle in the commune of Aussurucq in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques département of France

Switzerland

* Ruth, a hamlet in Cologny

United States

* Ruth, Alabama

* Ruth, Ar ...

passed the time by pushing her two-year-old brother Richard around the enclosed promenade in a stroller provided by the White Star Line.

Two Roman Catholic priests on board, Father Thomas Byles and Father Joseph Peruschitz, celebrated

Two Roman Catholic priests on board, Father Thomas Byles and Father Joseph Peruschitz, celebrated mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

every day for second- and third-class passengers during the voyage. Father Byles gave his homilies in English, Irish, and French and Father Peruschitz gave his in German and Hungarian. Father Byles reportedly perished in the sinking, performing blessings and last rites for those trapped.

On the ship, a Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

n priest, Father Juozas Montvila, also perished during the sinking.

Rev. John Harper, a well-known Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

pastor from Scotland, was travelling to the United States with his daughter and sister to preach at the Moody Church

The Moody Church (often referred to as Moody Memorial Church, after a sign hung on the North Avenue side of the building) is a historic evangelical Christian (Nondenominational Christianity) church in the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Chicago, Ill ...

in Chicago.

Schoolteacher Lawrence Beesley

Lawrence Beesley (31 December 1877 – 14 February 1967) was an English science teacher, journalist and author who was a survivor of the sinking of .

Education

Beesley was educated at Derby School, where he was a scholar, and afterwards at Cai ...

, a science master at Dulwich College, spent much of his time aboard the ship in the library. Two months after the sinking, he wrote and published ''The Loss of the SS Titanic'', the first eyewitness account of the disaster.

The Laroche family, father Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

and daughters Simonne and Louise

Louise or Luise may refer to:

* Louise (given name)

Arts Songs

* "Louise" (Bonnie Tyler song), 2005

* "Louise" (The Human League song), 1984

* "Louise" (Jett Rebel song), 2013

* "Louise" (Maurice Chevalier song), 1929

*"Louise", by Clan of ...

, were the only known passengers of black ancestry on board the ship. They, along with Joseph's pregnant wife Juliette, were travelling to Joseph's native island of Haiti. Joseph hoped that a move from their former home in Paris back to Haiti, where his uncle Cincinnatus Leconte

Jean Jacques Dessalines Michel Cincinnatus Leconte (September 29, 1854 – August 8, 1912) was President of Haiti from August 15, 1911 until his death on August 8, 1912. He was the great-grandson of Jean-Jacques Dessalines—a leader of the Hait ...

was president, would take his family away from racial discrimination.

Another French family travelling in second class was the Navratils, travelling under the assumed name Hoffman. Michel Navratil, a Slovak-born French tailor, had kidnapped his two young sons, Michel Jr. and Edmond from his estranged wife, assumed the name Charles Hoffman, and boarded the ship in Southampton, intent on taking his children to the United States. Michel Sr. died in the sinking and photographs of the boys were circulated throughout the world in the hopes that their mother or another relative could identify the French toddlers, who became known as the "Titanic Orphans".

After arriving in New York, the children were cared for by ''Titanic'' survivor Margaret Hays until their mother, Marcelle Navratil travelled from Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative c ...

, France, to claim them. The last living second-class survivor was Barbara West

Barbara Joyce Dainton (née West, 24 May 1911 – 16 October 2007) was the penultimate remaining survivor of the sinking of the RMS ''Titanic'' on 14 April 1912 after hitting an iceberg on its maiden voyage. She was the last living survivor ...

; she was 10 months old at the time of sinking and died in 2007 at the age of 96.

Third class

The third-class passengers or steerage passengers left hoping to start new lives in the United States and Canada. Third-class passengers paid £7 (£ today) for their ticket, depending on their place of origin; ticket prices often included the price of rail travel to the three departure ports. Tickets for children cost £3 (£ today).

Third-class passengers were a diverse group of nationalities and ethnic groups. In addition to large numbers of British, Irish, and Scandinavian immigrants, other passengers were from Central and Eastern Europe, the

The third-class passengers or steerage passengers left hoping to start new lives in the United States and Canada. Third-class passengers paid £7 (£ today) for their ticket, depending on their place of origin; ticket prices often included the price of rail travel to the three departure ports. Tickets for children cost £3 (£ today).

Third-class passengers were a diverse group of nationalities and ethnic groups. In addition to large numbers of British, Irish, and Scandinavian immigrants, other passengers were from Central and Eastern Europe, the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

(primarily Syria (Lebanon today)), and Hong Kong. Some travelled alone or in small family groups. Several groups of mothers were travelling alone with their young children—most going to join their husbands, who had already gone to America to find jobs, and having saved enough money, could now send for their families.

Among the larger third-class families were John and Annie Sage, who were immigrating to Jacksonville, Florida, with their 9 children, ranging in age from 4 to 20 years; Anders and Alfrida Andersson of Sweden and their five children, who were travelling to Canada along with Alfrida's younger sister Anna, husband Ernst, and baby Gilbert; and Frederick and Augusta Goodwin, who were moving with their six children to his new job at a power plant in New York. In 2007, scientists using DNA analysis identified the body of a small, fair-haired toddler, one of the first victims to be recovered by the CS ''

Among the larger third-class families were John and Annie Sage, who were immigrating to Jacksonville, Florida, with their 9 children, ranging in age from 4 to 20 years; Anders and Alfrida Andersson of Sweden and their five children, who were travelling to Canada along with Alfrida's younger sister Anna, husband Ernst, and baby Gilbert; and Frederick and Augusta Goodwin, who were moving with their six children to his new job at a power plant in New York. In 2007, scientists using DNA analysis identified the body of a small, fair-haired toddler, one of the first victims to be recovered by the CS ''Mackay Bennett

Cable Ship (CS) ''Mackay-Bennett'' was a transatlantic cable-laying and cable-repair ship registered at Lloyds of London, as a Glasgow vessel, but owned by the American Commercial Cable Company. It is notable for being the ship that recovered t ...

'', as Frederick and Augusta's youngest child, 19-month-old Sidney

Sidney may refer to:

People

* Sidney (surname), English surname

* Sidney (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Sidney (footballer, born 1972), full name Sidney da Silva Souza, Brazilian football defensive midfielder

* ...

. The Sages, Anderssons and Goodwins all perished in the sinking.

The youngest passenger on board the ship, 2-month-old Millvina Dean, who with her parents Bertram Sr. and Eva Dean and older brother Bertram, was emigrating from England to Kansas, died in 2009. She was the last survivor of the ''Titanic'' disaster to die.

To compete with rival shipping company

To compete with rival shipping company Cunard

Cunard () is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its three ships have been registered in Hamilton, Bermu ...

, the White Star Line offered their steerage passengers modest luxuries, in the hopes that emigrants would write to relatives back home and encourage them to travel on White Star Line ships. Third-class passengers had their own dining facilities, with chairs instead of benches, and meals prepared by the third-class kitchen staff. On other liners, the steerage-passengers would have been expected to bring their own food. Rather than dormitory-style sleeping areas, third-class passengers had their own cabins. The single men and women were separated, women in the stern in two to six berth cabins, men in the bow in up to 10 berth cabins, often shared with strangers. Each stateroom was fitted with wood panelling and beds with mattresses, blankets, pillows, electric lights, heat, and a washbasin with running water, except for the bow cabins, which did not have a private washbasin. Two public bathtubs were also provided, one for the men, the other for women.

Passengers gathered in the third-class common room, where they could play chess

Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to disti ...

or cards, or walk along the poop deck

In naval architecture, a poop deck is a deck that forms the roof of a cabin built in the rear, or " aft", part of the superstructure of a ship.

The name originates from the French word for stern, ''la poupe'', from Latin ''puppis''. Thus th ...

. Third-class children played in the common room or explored the ship. Nine-year-old Frank Goldsmith

Francis Benedict Hyam Goldsmith (22 November 1878 – 14 February 1967) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1910 to 1918. He served in World War I. In 1918, he moved to France, where he ent ...

recalled peering into the engine room and climbing up the baggage cranes on the poop deck.

Ship's regulations were designed to keep third-class passengers confined to their area of the ship. The ''Titanic'' was fitted with grilles to prevent the classes from mingling and these gates were normally kept closed, although the stewards could open them in the event of an emergency. In the rush following the collision, the stewards, occupied with waking up sleeping passengers and leading groups of women and children to the boat deck, did not have time to open all the gates, leaving many of the confused third-class passengers stuck below decks.

Ticket-holders who did not sail

Numerous notable and prominent people of the era, who held tickets for the westbound passage or were guests of those who held tickets, did not sail. Others were waiting in New York to board for the passage back toPlymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

, England, on the second leg of ''Titanic''s maiden voyage. Many of the unused tickets that survived, whether they were for the westbound passage or the return eastbound passage, have become quite valuable as ''Titanic''-related artifacts. Those who held tickets for a passage, but did not actually sail, include Theodore Dreiser, Henry Clay Frick, Milton S. Hershey

Milton Snavely Hershey (September 13, 1857 – October 13, 1945) was an American chocolatier, businessman, and philanthropist.

Trained in the confectionery business, Hershey pioneered the manufacture of caramel, using fresh milk. He launched t ...

, Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquis of Marconi (; 25 April 187420 July 1937) was an Italians, Italian inventor and electrical engineering, electrical engineer, known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based Wireless telegrap ...

, John Pierpont Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age. As the head of the banking firm that ultimately became kno ...

, John Mott

John Raleigh Mott (May 25, 1865 – January 31, 1955) was an evangelist and long-serving leader of the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) and the World Student Christian Federation (WSCF). He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1946 for hi ...

, George Washington Vanderbilt II.

Passengers by ethnicity

It has been widely thought that there were more than 80 passengers from theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, including Turkish, Armenian and Levantine backgrounds.

Bulgarian passengers

According to official data from Lloyd's insurance company, 38 of the passengers aboard the ''Titanic'', were Bulgarians. There are assumptions that the number of Bulgarian citizens exceeds 50. Near the town ofTroyan

Troyan ( bg, Троян ) List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, is a town remembering the name of Roman Emperor Trajan, in Lovech Province in central Bulgaria with population of 21,997 inhabitants, as of December 2009. It is the administrative ...

in Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

, there is a cenotaph monument to the 8 inhabitants of the village of Gumoshtnik who died, whose names were probably not on the list of the insurance company. The estimated number of surviving Bulgarians is 15, with many remaining in the United States. In memory of the Bulgarians who died on the ''Titanic'' from the village of Terziysko - Minko Angelov and Hristo Danchev, a folk song was created.

Syrian passengers

Several passengers on the ''Titanic'' had Levantine origins. At the time, many carried identification from theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

that stated they were from Greater Syria

Syria (Hieroglyphic Luwian: 𔒂𔒠 ''Sura/i''; gr, Συρία) or Sham ( ar, ٱلشَّام, ash-Shām) is the name of a historical region located east of the Mediterranean Sea in Western Asia, broadly synonymous with the Levant. Other s ...

, which included what is today Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

, Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

, and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

.

According to Bakhos Assaf, mayor of Hardin, Lebanon, 93 passengers originated from what is today Lebanon, with 20 of them from Hardin, the highest number of any Lebanese location. Of the Hardin passengers, 11 adult men died, while eight women and children and one adult man survived. Kamal Seikaly, an individual quoted in an article from the Lebanese publication '' The Daily Star'', stated that according to a 16 May 1912, issue of the ''Al-Khawater'' magazine stored in the American University of Beirut

The American University of Beirut (AUB) ( ar, الجامعة الأميركية في بيروت) is a private, non-sectarian, and independent university chartered in New York with its campus in Beirut, Lebanon. AUB is governed by a private, aut ...

, of the 125 Lebanese aboard, 23 survived. The magazine states that 10 people from Kfar Meshki

Kfarmishki, also spelled Kfar Mishki or Kfar Mechki (Arabic: كفرمشكي), is a small mountain authority in the Rashaya District of the Beqaa Governorate, Beqaa Governate in Lebanon. This village is located approximately 92 km southeast o ...

died on the ''Titanic''. According to author Judith Geller, "officially here

Here is an adverb that means "in, on, or at this place". It may also refer to:

Software

* Here Technologies, a mapping company

* Here WeGo (formerly Here Maps), a mobile app and map website by Here

Television

* Here TV (formerly "here!"), a TV ...

were 154 Syrians on board the Titanic and 29 were saved: four men, five children, and 20 women".

In 1997, Ray Hanania, a Palestinian American

Palestinian Americans ( ar, فلسطينيو أمريكا) are Americans who are of full or partial Palestinian descent. It is unclear when the first Palestinian immigrants arrived in the United States, but it is believed that they arrived dur ...

journalist, watched the ''Titanic

RMS ''Titanic'' was a British passenger liner, operated by the White Star Line, which sank in the North Atlantic Ocean on 15 April 1912 after striking an iceberg during her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, United ...

'' (1997) film and noticed some background characters saying ''yalla'', meaning "hurry" in Arabic. This prompted him to research the issue and he discovered that Arab passengers were on board.Al-Tamimi, Jumana.The untold story of Arabs

." ''

Gulf News

''Gulf News'' is a daily English language newspaper published from Dubai, United Arab Emirates. It was first launched in 1978, and is currently distributed throughout the UAE and also in other Persian Gulf Countries. Its online edition was launch ...

''. 12 April 2012. Retrieved on 25 December 2013. In 1998, he wrote a column about the Arabs on the RMS ''Titanic'', "Titanic: We Share the Pain But Not the Glory." According to Hanania's analysis, 79 Arab passengers were on board the ship, though the task to "identify precisely" which passengers were Arab is difficult. Hanania stated that many were Christians because church sponsorship made getting passage easier for Christians as opposed to Muslims and Christians were more likely to emigrate due to persecution by the Ottoman regime. An in-depth study was made by Leila Salloum Elias about the lives of Syrian, as well as Armenian passengers aboard the ship, using volumes of research taken from Arabic newspapers contemporary to the sinking to clarify the names and circumstances of many Syrian passengers. The total number of Syrian passengers, according to Syrian survivors was between 145 and 165, of these, only one couple who boarded as second-class passengers. Salloum's passenger count is based on the contemporary sources of the sinking in which names are clarified and given based on their true and authentic Arabic names, families and village, town or city of origin.

Chinese passengers

Eight passengers are listed on the passenger list with a home country of China, from the hometown of Hong Kong, with a destination of New York. Six of these persons survived the disaster. They were not permitted to enter the United States due to theChinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplom ...

.Wang, Amy B.Why you've never heard of the six Chinese men who survived the Titanic

." ''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

''. 19 April 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2018. One of these Chinese survivors from the ''Titanic'' disaster was Fang Lang (21 June 1894 – 21 January 1986; alias Fong Wing Sun), who was one of the four passengers whom Fifth Officer Harold Lowe rescued from the ocean after returning in Lifeboat 14 to search for any survivors still stranded in the sea. Fang settled in US, and one of Fang's fellow survivors Lee Bing moved to Canada living in Galt, Ontario

Galt is a community in Cambridge, Ontario, Canada, in the Regional Municipality of Waterloo, Ontario on the Grand River. Prior to 1973, it was an independent city, incorporated in 1915, but amalgamation with the town of Hespeler, Ontario, the to ...

(worked at White Rose Cafe), then Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

and disappears having left for China. The stories of the Chinese survivors, which were forgotten for over a century, were presented in a 2021 documentary film '' The Six'' after researchers and show producers worked together to piece together the whereabouts and lives of the Chinese survivors after the sinking of the Titanic.

Survivors and victims

On the night of 14 April 1912, around 11:40 pm, while the RMS ''Titanic'' was sailing about south of theGrand Banks of Newfoundland

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland are a series of underwater plateaus south-east of the island of Newfoundland on the North American continental shelf. The Grand Banks are one of the world's richest fishing grounds, supporting Atlantic cod, swordf ...

, the ship struck an iceberg and began to sink. Shortly before midnight, Captain Edward Smith ordered the ship's lifeboats

Lifeboat may refer to:

Rescue vessels

* Lifeboat (shipboard), a small craft aboard a ship to allow for emergency escape

* Lifeboat (rescue), a boat designed for sea rescues

* Airborne lifeboat, an air-dropped boat used to save downed airmen

A ...

to be readied and a distress call was sent out. The closest ship to respond was Cunard Line

Cunard () is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its three ships have been registered in Hamilton, Berm ...

's away, which would arrive in an estimated 4 hours—too late to rescue all of ''Titanic'' passengers. Forty-five minutes after the ship hit the iceberg, Captain Smith ordered the lifeboats to be loaded and lowered under the orders women and children first

''Women and Children First'' is the third studio album by American Rock music, rock band Van Halen, released on March 26, 1980, on Warner Bros. Records. Produced by Ted Templeman and engineered by Donn Landee, it was the first Van Halen album no ...

.

The first lifeboat launched was Lifeboat 7 on the

The first lifeboat launched was Lifeboat 7 on the starboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms for watercraft and aircraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the bow (front).

Vessels with bilateral symmetry have left and right halves which are ...

side with 28 people on board out of a capacity of 65. It was lowered around 12:45 am as believed by the British Inquiry. Collapsible Boat D was the last lifeboat to be launched, at 2:05. Two more lifeboats, Collapsible Boats A and B, were in the process of being removed from their location on the roof of the officer's house, but could not be properly launched. Collapsible B floated away from the ship upside down, while Collapsible A became half-filled with water after the supports for its canvas sides were broken in the fall from the roof of the officers' quarters. Arguments occurred in some of the lifeboats about going back to pick up people in the water, but many survivors were afraid of being swamped by people trying to climb into the lifeboat or being pulled down by the suction from the sinking ''Titanic'', though it turned out that very little suction had happened.Wreck Commissioners' Court: Proceedings on a Formal Investigation Ordered by the Board of Trade into the Loss of the S. S. ''TITANIC'', London 1912 At 2:20 am, ''Titanic'' herself sank.W. Garzke et al. arine Forensic Panel (SD 7) Titanic, The Anatomy of a Disaster. The Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers, 1997 A small number of passengers and crew were able to make their way to the two unlaunched collapsible boats, surviving for several hours (some still clinging to the overturned Collapsible B) until they were rescued by Fifth Officer Harold Lowe

Commander Harold Godfrey Lowe RD, RNR (21 November 1882 – 12 May 1944) was the fifth officer of the . He was amongst the 4 officers to survive the disaster

Biography

Early years

Harold Lowe was born in Llanrhos, Caernarvonshire, Wales on ...

.

At 4:10 am, ''Carpathia'' arrived at the site of the sinking and began rescuing survivors. By 8:30 am, she picked up the last lifeboat with survivors and left the area at 08:50 bound for

At 4:10 am, ''Carpathia'' arrived at the site of the sinking and began rescuing survivors. By 8:30 am, she picked up the last lifeboat with survivors and left the area at 08:50 bound for Pier 54

Chelsea Piers is a series of piers in Chelsea, on the West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located to the west of the West Side Highway ( Eleventh Avenue) and Hudson River Park and to the east of the Hudson River, they were originally a p ...

in New York City. Of the 711 passengers and crew rescued by the ''Carpathia'', six, including first-class passenger William F. Hoyt, either died in a lifeboat during the night or on board the ''Carpathia'' the next morning, and were buried at sea

Burial at sea is the disposal of human remains in the ocean, normally from a ship or boat. It is regularly performed by navies, and is done by private citizens in many countries.

Burial-at-sea services are conducted at many different location ...

.

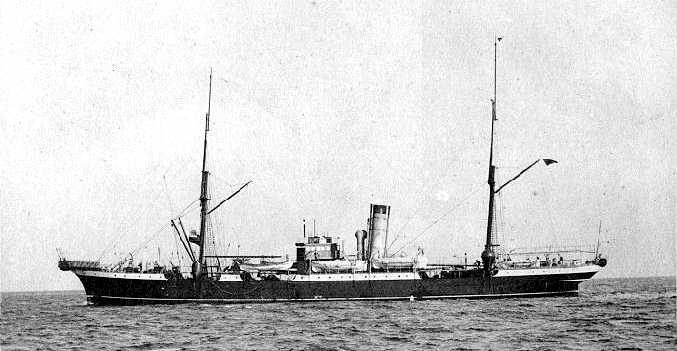

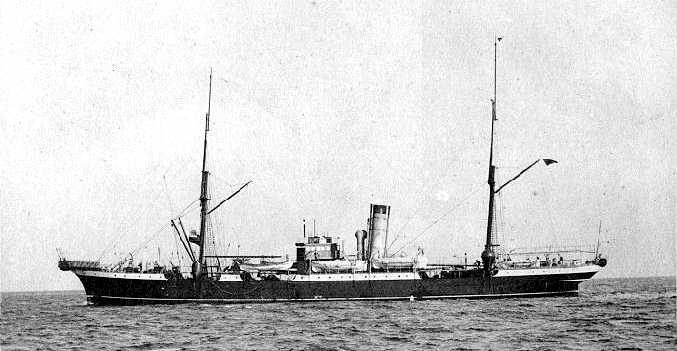

In the days following the sinking, several ships sailed to the disaster area to recover victims' bodies. The White Star Line chartered the cable ship '' Mackay-Bennett'' from Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

, to retrieve bodies. Three other ships followed in the search: the cable ship ''Minia'', the lighthouse supply ship ''Montmagny'', and the sealing vessel ''Algerine''. Each ship left with embalming supplies, undertakers, and clergy. Upon recovery, each body retrieved by the ''Mackay-Bennett'' was numbered and given as detailed a description as possible to help aid in identification. The physical appearance of each body—height, weight, age, hair and eye colour, visible birthmarks, scars or tattoos, was catalogued and any personal effects on the bodies were gathered and placed in small canvas bags corresponding to their number.

The ship found so many bodies – 306 – that the embalming supplies aboard were quickly exhausted. Health regulations permitted that only embalmed bodies could be returned to port. Captain Larnder of the ''Mackay-Bennett'' and the undertakers aboard decided to preserve all bodies of first-class passengers because of the need to visually identify wealthy men to resolve any disputes over large estates. As a result, the majority of the 116 burials at sea were third-class passengers and crew (only 56 were identified). Larnder himself claimed that as a mariner, he would expect to be buried at sea. However, complaints about the burials at sea were made by families and undertakers. Later ships such as ''Minia'' found fewer bodies, requiring fewer embalming supplies, and were able to limit burials at sea to bodies that were too damaged to preserve.

190 bodies recovered were preserved and taken to

The ship found so many bodies – 306 – that the embalming supplies aboard were quickly exhausted. Health regulations permitted that only embalmed bodies could be returned to port. Captain Larnder of the ''Mackay-Bennett'' and the undertakers aboard decided to preserve all bodies of first-class passengers because of the need to visually identify wealthy men to resolve any disputes over large estates. As a result, the majority of the 116 burials at sea were third-class passengers and crew (only 56 were identified). Larnder himself claimed that as a mariner, he would expect to be buried at sea. However, complaints about the burials at sea were made by families and undertakers. Later ships such as ''Minia'' found fewer bodies, requiring fewer embalming supplies, and were able to limit burials at sea to bodies that were too damaged to preserve.

190 bodies recovered were preserved and taken to Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

, the closest city to the sinking with direct rail and steamship connections. A large temporary morgue was set up in a curling

Curling is a sport in which players slide stones on a sheet of ice toward a target area which is segmented into four concentric circles. It is related to bowls, boules, and shuffleboard. Two teams, each with four players, take turns sliding ...

rink, and undertakers were called in from all across Eastern Canada to assist. Relatives from across North America came to identify and claim the bodies of their relatives. Some bodies were shipped to be buried in their home towns across North America and Europe. About two-thirds of the bodies were identified. Of the remaining 150 unclaimed bodies, 121 were taken to the non-denominational Fairview Lawn Cemetery

Fairview Cemetery is a cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. It is perhaps best known as the final resting place for over one hundred victims of the sinking of the Titanic. Officially known as Fairview Lawn Cemetery, the non-denominational cem ...

; 19 were buried in the Roman Catholic Mount Olivet Cemetery, and 10 were taken to the Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

Baron de Hirsch Cemetery. Unidentified victims were buried with simple numbers based on the order in which their bodies were discovered.

In mid-May 1912, over from the site of the sinking, recovered three bodies, numbers 331, 332, and 333, who were among the original occupants of Collapsible A, which was swamped in the last moments of the sinking. Although several people managed to reach this lifeboat, three died during the night. When Fifth Officer Harold Lowe and six crewmen returned to the wreck site after the sinking with an empty lifeboat to pick up survivors, they rescued surviving passengers from Collapsible A, but left the three dead bodies in the boat: Thomson Beattie, a first-class passenger, and two crew members, a fireman and a seaman. After their retrieval from Collapsible A by ''Oceanic'', the bodies were buried at sea.

Passenger list

The following is a full list of known passengers who sailed on the maiden voyage of the RMS ''Titanic''. Included in this list are the nine-member Guarantee Group and the eight members of the ship's band, listed as both passengers and crew. They are also included in the list of crew members on board RMS ''Titanic''. Passengers are colour-coded, indicating whether they were saved or perished.The passenger did not survive

The passenger survived

Survivors are listed with the lifeboat from which they were known to be rescued. Victims whose remains were recovered after the sinking are listed with a superscript next to the body number, indicating the recovery vessel: *MB – CS ''Mackay-Bennett'' (bodies 1–306) *M – CS ''Minia'' (bodies 307–323) *MM – CGS ''Montmagny'' (bodies 326–329) *A – SS ''Algerine'' (body 330) *O – RMS ''Oceanic'' (bodies 331–333) *I – SS ''Ilford'' (body 334) *OT – SS ''Ottawa'' (body 335) Numbers 324 and 325 were unused, and the six bodies buried at sea by the ''Carpathia'' also went unnumbered.

First class

Second class

Third class

Cross-channel passengers

In addition to the above-listed passengers, the ''Titanic'' carried 29 cross-channel passengers who boarded at Southampton and disembarked at eitherCherbourg

Cherbourg (; , , ), nrf, Chèrbourg, ) is a former commune and subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French department of Manche. It was merged into the commune of Cherbourg-Octeville on 28 Feb ...

, France, or Queenstown, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

.

First passenger survivors to die

Last passenger survivors to die

See also

* Crew of the RMS ''Titanic''Footnotes

References

Further reading

* * * * Newspaper interview with passenger John Pillsbury Snyder.External links

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Titanic, Passengers of # Shipwrecked people Lists of victims